National American Woman Suffrage Association on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of

Anthony increasingly began to emphasize suffrage over other women's rights issues. Her aim was to unite the growing number of women's organizations in the demand for suffrage even if they did not support other women's rights issues. She and the NWSA also began placing less emphasis on confrontational actions and more on respectability. The NWSA was no longer seen as an organization that challenged traditional family arrangements by supporting, for example, what its opponents called "easy divorce". All this had the effect of moving it into closer alignment with the AWSA.

The Senate's rejection in 1887 of the proposed women's suffrage amendment to the

Anthony increasingly began to emphasize suffrage over other women's rights issues. Her aim was to unite the growing number of women's organizations in the demand for suffrage even if they did not support other women's rights issues. She and the NWSA also began placing less emphasis on confrontational actions and more on respectability. The NWSA was no longer seen as an organization that challenged traditional family arrangements by supporting, for example, what its opponents called "easy divorce". All this had the effect of moving it into closer alignment with the AWSA.

The Senate's rejection in 1887 of the proposed women's suffrage amendment to the

pp. 8, 14–16

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. Stanton continued to promote all aspects of women's rights. She advocated a coalition of radical social reform groups, including Populists and Socialists, who would support women's suffrage as part of a joint list of demands. In a letter to a friend, Stanton said the NWSA "has been growing politic and conservative for some time. Lucy toneand Susan nthonyalike see suffrage only. They do not see woman's religious and social bondage, neither do the young women in either association, hence they may as well combine". Stanton, however, had largely withdrawn from the day-to-day activity of the suffrage movement. She spent much of her time with her daughter in England during this period. Despite their different approaches, Stanton and Anthony remained friends and co-workers, continuing a collaboration that had begun in the early 1850s. Stone devoted most of her life after the split to the ''

pp. 629–630

In February, Stone, Stanton, Anthony and other leaders of both organizations issued an "Open Letter to the Women of America" declaring their intention to work together. When Anthony and Stone first discussed the possibility of merger in 1887, Stone had proposed that she, Stanton and Anthony should all decline the presidency of the united organization. Anthony initially agreed, but other NWSA members objected strongly. The basis for agreement did not include that stipulation. The AWSA initially was the larger of the two organizations, but it had declined in strength during the 1880s. The NWSA was perceived as the main representative of the suffrage movement, partly because of Anthony's ability to find dramatic ways of bringing suffrage to the nation's attention. Anthony and Stanton had also published their massive

Stanton's election as president was largely symbolic. Before the convention was over, she left for another extended stay with her daughter in England, leaving Anthony in charge.

Stanton retired from the presidency in 1892, after which Anthony was elected to the position that she had in practice been occupying all along.

Stone, who died in 1893, did not play a major role in the NAWSA.

The movement's vigor declined in the years immediately after the merger.

The new organization was small, having only about 7000 dues-paying members in 1893.

It also suffered from organizational problems, not having a clear idea of, for example, how many local suffrage clubs there were or who their officers were.

In 1893, NAWSA members

Stanton's election as president was largely symbolic. Before the convention was over, she left for another extended stay with her daughter in England, leaving Anthony in charge.

Stanton retired from the presidency in 1892, after which Anthony was elected to the position that she had in practice been occupying all along.

Stone, who died in 1893, did not play a major role in the NAWSA.

The movement's vigor declined in the years immediately after the merger.

The new organization was small, having only about 7000 dues-paying members in 1893.

It also suffered from organizational problems, not having a clear idea of, for example, how many local suffrage clubs there were or who their officers were.

In 1893, NAWSA members

The Hand Book of the National American Woman Suffrage Association and Proceedings of the ... Annual Convention

/ref> In 1895, she was placed in charge of NAWSA's Organizational Committee, where she raised money to put a team of fourteen organizers in the field. By 1899, suffrage organizations had been established in every state. When Anthony retired as NAWSA president in 1900, she chose Catt to succeed her. Anthony remained an influential figure in the organization, however, until she died in 1906. One of Catt's first actions as president was to implement the "society plan," a campaign to recruit wealthy members of the rapidly growing

One of Catt's first actions as president was to implement the "society plan," a campaign to recruit wealthy members of the rapidly growing  The reform energy of the

The reform energy of the

In 1906, southern NAWSA members formed the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference with Blackwell's encouragement. Although it had a frankly racist program, it asked for NAWSA's endorsement. Shaw refused, setting a limit on how far the organization was willing to go to accommodate southerners with overtly racist views. Shaw said the organization would not adopt policies that "advocated the exclusion of any race or class from the right of suffrage."

In 1907, partly in reaction to NAWSA's "society plan", which was designed to appeal to upper-class women,

In 1906, southern NAWSA members formed the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference with Blackwell's encouragement. Although it had a frankly racist program, it asked for NAWSA's endorsement. Shaw refused, setting a limit on how far the organization was willing to go to accommodate southerners with overtly racist views. Shaw said the organization would not adopt policies that "advocated the exclusion of any race or class from the right of suffrage."

In 1907, partly in reaction to NAWSA's "society plan", which was designed to appeal to upper-class women,  In 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois, president of the

In 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois, president of the

From Shaw's point of view, the time was right for a renewed emphasis on a suffrage amendment. Gordon and Clay, the most persistent adversaries of a federal suffrage amendment within NAWSA, had been out-maneuvered by their opponents and no longer held national posts.

In 1912, Alice Paul was appointed chair of NAWSA's Congressional Committee and charged with reviving the drive for a women's suffrage amendment. In 1913, she and her coworker

From Shaw's point of view, the time was right for a renewed emphasis on a suffrage amendment. Gordon and Clay, the most persistent adversaries of a federal suffrage amendment within NAWSA, had been out-maneuvered by their opponents and no longer held national posts.

In 1912, Alice Paul was appointed chair of NAWSA's Congressional Committee and charged with reviving the drive for a women's suffrage amendment. In 1913, she and her coworker

NAWSA's Congressional Committee had been in disarray ever since Alice Paul was removed from it in 1913. Catt reorganized the committee and appointed Maud Wood Park as its head in December, 1916. Park and her lieutenant Helen Hamilton Gardener created what became known as the "Front Door Lobby", so named by a journalist because it operated openly, avoiding the traditional lobbying methods of "backstairs" dealing. A headquarters for the lobbying effort was established in a dilapidated mansion known as Suffrage House. NAWSA lobbyists lodged there and coordinated their activities with daily conferences in its meeting rooms.

In 1916 the NAWSA purchased the ''

NAWSA's Congressional Committee had been in disarray ever since Alice Paul was removed from it in 1913. Catt reorganized the committee and appointed Maud Wood Park as its head in December, 1916. Park and her lieutenant Helen Hamilton Gardener created what became known as the "Front Door Lobby", so named by a journalist because it operated openly, avoiding the traditional lobbying methods of "backstairs" dealing. A headquarters for the lobbying effort was established in a dilapidated mansion known as Suffrage House. NAWSA lobbyists lodged there and coordinated their activities with daily conferences in its meeting rooms.

In 1916 the NAWSA purchased the ''

/ref> The newspaper's masthead declared itself to be the NAWSA's official organ.

By the end of 1919, women effectively could vote for president in states that had a majority of electoral votes.

Political leaders who were convinced that women's suffrage was inevitable began to pressure local and national legislators to support it so their party could claim credit for it in future elections. The conventions of both the Democratic and Republican Parties endorsed the amendment in June, 1920.

Former NAWSA members Kate Gordon and Laura Clay organized opposition to the amendment's ratification in the South. They had resigned from the NAWSA in the fall of 1918 at the executive board's request because of their public statements in opposition to a federal amendment.

Only three Southern or border states, Arkansas, Texas, and Tennessee, ratified the 19th Amendment, with Tennessee being the crucial 36th state to ratify.

The Nineteenth Amendment, the women's suffrage amendment, became the law of the land on August 26, 1920, when it was certified by the

By the end of 1919, women effectively could vote for president in states that had a majority of electoral votes.

Political leaders who were convinced that women's suffrage was inevitable began to pressure local and national legislators to support it so their party could claim credit for it in future elections. The conventions of both the Democratic and Republican Parties endorsed the amendment in June, 1920.

Former NAWSA members Kate Gordon and Laura Clay organized opposition to the amendment's ratification in the South. They had resigned from the NAWSA in the fall of 1918 at the executive board's request because of their public statements in opposition to a federal amendment.

Only three Southern or border states, Arkansas, Texas, and Tennessee, ratified the 19th Amendment, with Tennessee being the crucial 36th state to ratify.

The Nineteenth Amendment, the women's suffrage amendment, became the law of the land on August 26, 1920, when it was certified by the

Women's Suffrage.

From the Library of Congress *

* ttp://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/suffrage/millerscrapbooks/ Elizabeth Smith Miller and Anne Fitzhugh Miller's NAWSA Suffrage Scrapbooks, 1897-1911

Webcast-Catch the Suffragist's Spirit; The Miller Scrapbooks

From the Library of Congress {{Authority control Organizations established in 1890 Women's suffrage advocacy groups in the United States Civil rights organizations in the United States Liberal feminist organizations History of women's rights in the United States First-wave feminism Susan B. Anthony Progressive Era in the United States League of Women Voters

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States

In the 1700's to early 1800's New Jersey did allow Women the right to vote before the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, 19th Amendment, but in 1807 the state restricted the right to vote to "...tax-paying, ...

. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement s ...

(NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

, a long-time leader in the suffrage movement, was the dominant figure in the newly formed NAWSA. Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

, who became president after Anthony retired in 1900, implemented a strategy of recruiting wealthy members of the rapidly growing women's club

The woman's club movement was a social movement that took place throughout the United States that established the idea that women had a moral duty and responsibility to transform public policy. While women's organizations had always been a part ...

movement, whose time, money and experience could help build the suffrage movement. Anna Howard Shaw

Anna Howard Shaw (February 14, 1847 – July 2, 1919) was a leader of the women's suffrage movement in the United States. She was also a physician and one of the first ordained female Methodist ministers in the United States.

Early life

Shaw ...

's term in office, which began in 1904, saw strong growth in the organization's membership and public approval.

After the Senate decisively rejected the proposed women's suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nation ...

in 1887, the suffrage movement had concentrated most of its efforts on state suffrage campaigns. In 1910 Alice Paul joined the NAWSA and played a major role in reviving interest in the national amendment. After continuing conflicts with the NAWSA leadership over tactics, Paul created a rival organization, the National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

.

When Catt again became president in 1915, the NAWSA adopted her plan to centralize the organization, and work toward the suffrage amendment as its primary goal. This was done despite opposition from Southern members who believed that a federal amendment would erode states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

. With its large membership and the increasing number of women voters in states where suffrage had already been achieved, the NAWSA began to operate more as a political pressure group than an educational group. It won additional sympathy for the suffrage cause by actively cooperating with the war effort during World War I. On February 14, 1920, several months prior to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the NAWSA transformed itself into the League of Women Voters, which is still active.

Background

The demand forwomen's suffrage in the United States

In the 1700's to early 1800's New Jersey did allow Women the right to vote before the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, 19th Amendment, but in 1807 the state restricted the right to vote to "...tax-paying, ...

was controversial even among women's rights activists in the early days of the movement. In 1848, a resolution in favor of women's right to vote was approved only after vigorous debate at the Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the tow ...

, the first women's rights convention. By the time of the National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention ...

s in the 1850s, the situation had changed, and women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vot ...

had become a preeminent goal of the movement.

Three leaders of the women's movement during this period, Lucy Stone, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony

Susan B. Anthony (born Susan Anthony; February 15, 1820 – March 13, 1906) was an American social reformer and women's rights activist who played a pivotal role in the women's suffrage movement. Born into a Quaker family committed to s ...

, played prominent roles in the creation of the NAWSA many years later.

In 1866, just after the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention

The National Women's Rights Convention was an annual series of meetings that increased the visibility of the early women's rights movement in the United States. First held in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts, the National Women's Rights Convention ...

transformed itself into the American Equal Rights Association

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color ...

(AERA), which worked for equal rights for both African Americans and white women, especially suffrage.

The AERA essentially collapsed in 1869, partly because of disagreement over the proposed Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which would enfranchise

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

African American men. Leaders of the women's movement were dismayed that it would not also enfranchise women. Stanton and Anthony opposed its ratification unless it was accompanied by another amendment that would enfranchise women.

Stone supported the amendment. She believed that its ratification would spur politicians to support a similar amendment for women. She said that even though the right to vote was more important for women than for black men, "I will be thankful in my soul if ''any'' body can get out of the terrible pit."

In May, 1869, two days after the acrimonious debates at what turned out to be the final AERA annual meeting, Anthony, Stanton and their allies formed the National Woman Suffrage Association

The National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was formed on May 15, 1869, to work for women's suffrage in the United States. Its main leaders were Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. It was created after the women's rights movement s ...

(NWSA). In November 1869, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) was formed by Lucy Stone, her husband Henry Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe

Julia Ward Howe (; May 27, 1819 – October 17, 1910) was an American author and poet, known for writing the " Battle Hymn of the Republic" and the original 1870 pacifist Mother's Day Proclamation. She was also an advocate for abolitionism ...

and their allies, many of whom had helped to create the New England Woman Suffrage Association a year earlier as part of the developing split.

The bitter rivalry between the two organizations created a partisan atmosphere that endured for decades.

Even after the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified in 1870, differences between the two organizations remained. The AWSA worked almost exclusively for women's suffrage while the NWSA initially worked on a wide range of issues, including divorce reform and equal pay for women

Equal pay for equal work is the concept of labour rights that individuals in the same workplace be given equal pay. It is most commonly used in the context of sexual discrimination, in relation to the gender pay gap. Equal pay relates to the ful ...

. The AWSA included both men and women among its leadership while the NWSA was led by women.

The AWSA worked for suffrage mostly at the state level while the NWSA worked more at the national level.

The AWSA cultivated an image of respectability while the NWSA sometimes used confrontational tactics. Anthony, for example, interrupted the official ceremonies at the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence to present NWSA's Declaration of Rights for Women.

Anthony was arrested in 1872 for voting, which was still illegal for women, and was found guilty in a highly publicized trial.

Progress toward women's suffrage was slow in the period after the split, but advancement in other areas strengthened the underpinnings of the movement. By 1890, tens of thousands of women were attending colleges and universities, up from zero a few decades earlier.

There was a decline in public support for the idea of "woman's sphere", the belief that a woman's place was in the home and that she should not be involved in politics. Laws that had allowed husbands to control their wives' activities had been significantly revised. There was a dramatic growth in all-female social reform organizations, such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union

The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) is an international temperance organization, originating among women in the United States Prohibition movement. It was among the first organizations of women devoted to social reform with a program th ...

(WCTU), the largest women's organization in the country. In a major boost for the suffrage movement, the WCTU endorsed women's suffrage in the late 1870s on the grounds that women needed the vote to protect their families from alcohol and other vices.

Anthony increasingly began to emphasize suffrage over other women's rights issues. Her aim was to unite the growing number of women's organizations in the demand for suffrage even if they did not support other women's rights issues. She and the NWSA also began placing less emphasis on confrontational actions and more on respectability. The NWSA was no longer seen as an organization that challenged traditional family arrangements by supporting, for example, what its opponents called "easy divorce". All this had the effect of moving it into closer alignment with the AWSA.

The Senate's rejection in 1887 of the proposed women's suffrage amendment to the

Anthony increasingly began to emphasize suffrage over other women's rights issues. Her aim was to unite the growing number of women's organizations in the demand for suffrage even if they did not support other women's rights issues. She and the NWSA also began placing less emphasis on confrontational actions and more on respectability. The NWSA was no longer seen as an organization that challenged traditional family arrangements by supporting, for example, what its opponents called "easy divorce". All this had the effect of moving it into closer alignment with the AWSA.

The Senate's rejection in 1887 of the proposed women's suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the nation ...

also brought the two organizations closer together. The NWSA had worked for years to convince Congress to bring the proposed amendment to a vote. After it was voted on and decisively rejected, the NWSA began to put less energy into campaigning at the federal level and more at the state level, as the AWSA was already doing.Gordon, Ann D, "Woman Suffrage (Not Universal Suffrage) by Federal Amendment" in Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill (ed.), (1995), ''Votes for Women!: The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation''pp. 8, 14–16

Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. Stanton continued to promote all aspects of women's rights. She advocated a coalition of radical social reform groups, including Populists and Socialists, who would support women's suffrage as part of a joint list of demands. In a letter to a friend, Stanton said the NWSA "has been growing politic and conservative for some time. Lucy toneand Susan nthonyalike see suffrage only. They do not see woman's religious and social bondage, neither do the young women in either association, hence they may as well combine". Stanton, however, had largely withdrawn from the day-to-day activity of the suffrage movement. She spent much of her time with her daughter in England during this period. Despite their different approaches, Stanton and Anthony remained friends and co-workers, continuing a collaboration that had begun in the early 1850s. Stone devoted most of her life after the split to the ''

Woman's Journal

''Woman's Journal'' was an American women's rights periodical published from 1870 to 1931. It was founded in 1870 in Boston, Massachusetts, by Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Browne Blackwell as a weekly newspaper. In 1917 it was purchased by ...

'', a weekly newspaper she launched in 1870 to serve as voice of the AWSA.

By the 1880s, the ''Woman's Journal'' had broadened its coverage and was seen by many as the newspaper of the entire movement.

The suffrage movement was attracting younger members who were impatient with the continuing division, seeing the obstacle more as a matter of personalities than principles. Alice Stone Blackwell

Alice Stone Blackwell (September 14, 1857 – March 15, 1950) was an American feminist, suffragist, journalist, radical socialist, and human rights advocate.

Early life and education

Blackwell was born in East Orange, New Jersey to Henry Browne ...

, daughter of Lucy Stone, said, "When I began to work for a union, the elders were not keen for it, on either side, but the younger women on both sides were. Nothing really stood in the way except the unpleasant feelings engendered during the long separation".

Merger of rival organizations

Several attempts had been made to bring the two sides together, but without success. The situation changed in 1887 when Stone, who was approaching her 70th birthday and in declining health, began to seek ways of overcoming the split. In a letter to suffragistAntoinette Brown Blackwell

Antoinette Louisa Brown, later Antoinette Brown Blackwell (May 20, 1825 – November 5, 1921), was the first woman to be ordained as a mainstream Protestant minister in the United States. She was a well-versed public speaker on the paramount iss ...

, she suggested the creation of an umbrella organization of which the AWSA and the NWSA would become auxiliaries, but that idea did not gain supporters.

In November 1887, the AWSA annual meeting passed a resolution authorizing Stone to confer with Anthony about the possibility of a merger. The resolution said the differences between the two associations had "been largely removed by the adoption of common principles and methods."

Stone forwarded the resolution to Anthony along with an invitation to meet with her.

Anthony and Rachel Foster, a young leader of the NWSA, traveled to Boston in December 1887, to meet with Stone. Accompanying Stone at this meeting was her daughter Alice Stone Blackwell

Alice Stone Blackwell (September 14, 1857 – March 15, 1950) was an American feminist, suffragist, journalist, radical socialist, and human rights advocate.

Early life and education

Blackwell was born in East Orange, New Jersey to Henry Browne ...

, who also was an officer of the AWSA. Stanton, who was in England at the time, did not attend. The meeting explored several aspects of a possible merger, including the name of the new organization and its structure. Stone had second thoughts soon afterwards, telling a friend she wished they had never offered to unite, but the merger process slowly continued.

An early public sign of improving relations between the two organizations occurred three months later at the founding congress of the International Council of Women

The International Council of Women (ICW) is a women's rights organization working across national boundaries for the common cause of advocating human rights for women. In March and April 1888, women leaders came together in Washington, D.C., wit ...

, which the NWSA organized and hosted in Washington in conjunction with the fortieth anniversary of the Seneca Falls Convention

The Seneca Falls Convention was the first women's rights convention. It advertised itself as "a convention to discuss the social, civil, and religious condition and rights of woman".Wellman, 2004, p. 189 Held in the Wesleyan Chapel of the tow ...

. It received favorable publicity, and its delegates, who came from fifty-three women's organizations in nine countries, were invited to a reception at the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

. Representatives from the AWSA were invited to sit on the platform during the meetings along with representatives from the NWSA, signaling a new atmosphere of cooperation.

The proposed merger did not generate significant controversy within the AWSA. The call to its annual meeting in 1887, the one that authorized Stone to explore the possibility of merger, did not even mention that this issue would be on the agenda. This proposal was treated in a routine manner during the meeting and was approved unanimously without debate.

The situation was different within the NWSA, where there was strong opposition from Matilda Joslyn Gage

Matilda Joslyn Gage (March 24, 1826 – March 18, 1898) was an American writer and activist. She is mainly known for her contributions to women's suffrage in the United States (i.e. the right to vote) but she also campaigned for Native Ameri ...

, Olympia Brown

Olympia Brown (January 5, 1835 – October 23, 1926) was an American minister and suffragist. She was the first woman to be ordained as clergy with the consent of her denomination. Brown was also an articulate advocate for women's rights and one ...

and others.

Ida Husted Harper

Ida Husted Harper (February 18, 1851 – March 14, 1931) was an American author, journalist, columnist, and suffragist, as well as the author of a three-volume biography of suffrage leader Susan B. Anthony at Anthony's request. Harper also c ...

, Anthony's co-worker and biographer, said the NWSA meetings that dealt with this issue "were the most stormy in the history of the association."

Charging that Anthony had used underhanded tactics to thwart opposition to the merger, Gage formed a competing organization in 1890 called the Woman's National Liberal Union, but it did not develop a significant following.

The AWSA and NWSA committees that negotiated the terms of merger signed a basis for agreement in January, 1889. See also Harper (1898–1908), Vol. 2pp. 629–630

In February, Stone, Stanton, Anthony and other leaders of both organizations issued an "Open Letter to the Women of America" declaring their intention to work together. When Anthony and Stone first discussed the possibility of merger in 1887, Stone had proposed that she, Stanton and Anthony should all decline the presidency of the united organization. Anthony initially agreed, but other NWSA members objected strongly. The basis for agreement did not include that stipulation. The AWSA initially was the larger of the two organizations, but it had declined in strength during the 1880s. The NWSA was perceived as the main representative of the suffrage movement, partly because of Anthony's ability to find dramatic ways of bringing suffrage to the nation's attention. Anthony and Stanton had also published their massive

History of Woman Suffrage

''History of Woman Suffrage'' is a book that was produced by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage and Ida Husted Harper. Published in six volumes from 1881 to 1922, it is a history of the women's suffrage movement, prima ...

, which placed them at the center of the movement's history and marginalized the role of Stone and the AWSA.

Stone's public visibility had declined significantly, contrasting sharply with the attention she had attracted in her younger days as a speaker on the national lecture circuit.

Anthony was increasingly recognized as a person of political importance. In 1890, prominent members of the House and Senate were among the two hundred people who attended her seventieth birthday celebration, a national event that took place in Washington three days before the convention that united the two suffrage organizations. Anthony and Stanton pointedly reaffirmed their friendship at this event, frustrating opponents of merger who had hoped to set them against one another.

Founding convention

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was created on February 18, 1890, in Washington by a convention that merged the NWSA and the AWSA. The question of who would lead the new organization had been left to the convention delegates. Stone, from the AWSA, was too ill to attend this convention and was not a candidate. Anthony and Stanton, both from the NWSA, each had supporters. The AWSA and NWSA executive committees met separately beforehand to discuss their choices for president of the united organization. At the AWSA meeting, Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband, said the NWSA had agreed to avoid mixing in side issues (the approach associated with Stanton) and to focus exclusively on suffrage (the approach of the AWSA and increasingly of Anthony). The executive committee recommended that AWSA delegates vote for Anthony. At the NWSA meeting, Anthony strongly urged its members not to vote for her but for Stanton, saying that a defeat of Stanton would be viewed as a repudiation of her role in the movement. Elections were held at the convention's opening. Stanton received 131 votes for president, Anthony received 90, and 2 votes were cast for other candidates. Anthony was elected vice president at large with 213 votes, with 9 votes for other candidates. Stone was unanimously elected chair of the executive committee. As president, Stanton delivered the convention's opening address. She urged the new organization to concern itself with a broad range of reforms, saying, "When any principle or question is up for discussion, let us seize on it and show its connection, whether nearly or remotely, with woman's disfranchisement." She introduced controversial resolutions, including one that called for women to be included at all levels of leadership within religious organizations and one that described liberal divorce laws as a married woman's "door of escape from bondage." Her speech had little lasting impact on the organization, however, because most of the younger suffragists did not agree with her approach.Stanton and Anthony presidencies

Stanton's election as president was largely symbolic. Before the convention was over, she left for another extended stay with her daughter in England, leaving Anthony in charge.

Stanton retired from the presidency in 1892, after which Anthony was elected to the position that she had in practice been occupying all along.

Stone, who died in 1893, did not play a major role in the NAWSA.

The movement's vigor declined in the years immediately after the merger.

The new organization was small, having only about 7000 dues-paying members in 1893.

It also suffered from organizational problems, not having a clear idea of, for example, how many local suffrage clubs there were or who their officers were.

In 1893, NAWSA members

Stanton's election as president was largely symbolic. Before the convention was over, she left for another extended stay with her daughter in England, leaving Anthony in charge.

Stanton retired from the presidency in 1892, after which Anthony was elected to the position that she had in practice been occupying all along.

Stone, who died in 1893, did not play a major role in the NAWSA.

The movement's vigor declined in the years immediately after the merger.

The new organization was small, having only about 7000 dues-paying members in 1893.

It also suffered from organizational problems, not having a clear idea of, for example, how many local suffrage clubs there were or who their officers were.

In 1893, NAWSA members May Wright Sewall

May Wright Sewall (May 27, 1844 – July 22, 1920) was an American reformer, who was known for her service to the causes of education, women's rights, and world peace. She was born in Greenfield, Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. Sewall served as cha ...

, former chair of NWSA's executive committee, and Rachel Foster Avery

Rachel Foster Avery (December 30, 1858 – October 26, 1919) was active in the American women's suffrage movement during the late 19th century, working closely with Susan B. Anthony and other movement leaders. She rose to be corresponding secr ...

, NAWSA's corresponding secretary, played key roles in the World's Congress of Representative Women

The World's Congress of Representative Women was a week-long convention for the voicing of women's concerns, held within The Woman's Building of the World's Columbian Exposition (Chicago, May 1893). At 81 meetings, organized by women from each of ...

at the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

, which was also known as the Chicago World's Fair. Sewall served as chair and Avery as secretary of the organizing committee for the women's congress.

In 1893, the NAWSA voted over Anthony's objection to alternate the site of its annual conventions between Washington and other parts of the country. Anthony's pre-merger NWSA had always held its conventions in Washington to help maintain focus on a national suffrage amendment. Anthony said she feared, accurately as it turned out, that the NAWSA would engage in suffrage work at the state level at the expense of national work.

The NAWSA routinely allocated no funding at all for congressional work, which at this stage consisted only of one day of testimony before Congress each year.

''Woman's Bible''

Stanton's radicalism did not sit well with the new organization. In 1895 she published ''The Woman's Bible

''The Woman's Bible'' is a two-part non-fiction book, written by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and a committee of 26 women, published in 1895 and 1898 to challenge the traditional position of religious orthodoxy that woman should be subservient to man ...

'', a controversial best-seller that attacked the use of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts ...

to relegate women to an inferior status. Her opponents within the NAWSA reacted strongly. They felt that the book would harm the drive for women's suffrage. Rachel Foster Avery, the organization's corresponding secretary, sharply denounced Stanton's book in her annual report to the 1896 convention. The NAWSA voted to disavow any connection with the book despite Anthony's strong objection that such a move was unnecessary and hurtful.

The negative reaction to the book contributed to a sharp decline in Stanton's influence in the suffrage movement and to her increasing alienation from it. She sent letters to each NAWSA convention, however, and Anthony insisted that they be read even when their topics were controversial.

Stanton died in 1902.

Southern strategy

The South had traditionally shown little interest in women's suffrage. When the proposed suffrage amendment to theConstitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

was rejected by the Senate in 1887, it received no votes at all from southern senators.

This indicated a problem for the future because it was almost impossible for any amendment to be ratified by the required number of states without at least some support from the South.

In 1867, Henry Blackwell proposed a solution: convince southern political leaders that they could ensure white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

in their region by enfranchising educated women, who would predominantly be white. Blackwell presented his plan to politicians from Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, who gave it serious consideration, a development that drew the interest of many suffragists. Blackwell's ally in this effort was Laura Clay, who convinced the NAWSA to launch a campaign in the South based on Blackwell's strategy. Clay was one of several southern NAWSA members who objected to the proposed national women's suffrage amendment on the grounds that it would impinge on states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

.

Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

traveled through the South en route to the NAWSA convention in Atlanta. Anthony asked her old friend Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

, a former slave, not to attend the NAWSA convention in Atlanta in 1895, the first to be held in a southern city. Black NAWSA members were excluded from 1903 convention in the southern city of New Orleans. The NAWSA executive board issued a statement during the convention that said, "The doctrine of State's rights is recognized in the national body, and each auxiliary State association arranges its own affairs in accordance with its own ideas and in harmony with the customs of its own section." As NAWSA turned its attention to a Constitutional Amendment, many Southern suffragists remained opposed because a federal amendment would enfranchise Black women. In response, in 1914, Kate Gordon founded the Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference

The Southern States Woman Suffrage Conference (also known as the Southern States Woman Suffrage Association) was a group dedicated to winning voting rights for white women. The group consisted mainly of highly educated, middle and upper class whit ...

, which opposed the 19th Amendment.

First Catt presidency

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

joined the suffrage movement in Iowa in the mid-1880s. and soon became part of the leadership of the state suffrage association. Married to a wealthy engineer who encouraged her suffrage work, she was able to devote much of her energy to the movement. She led some smaller NAWSA committees, for example serving as Chairman of the Literature Committee in 1893 with the help of Mary Hutcheson Page, another active NAWSA member.National American Women Suffrage (1893)The Hand Book of the National American Woman Suffrage Association and Proceedings of the ... Annual Convention

/ref> In 1895, she was placed in charge of NAWSA's Organizational Committee, where she raised money to put a team of fourteen organizers in the field. By 1899, suffrage organizations had been established in every state. When Anthony retired as NAWSA president in 1900, she chose Catt to succeed her. Anthony remained an influential figure in the organization, however, until she died in 1906.

One of Catt's first actions as president was to implement the "society plan," a campaign to recruit wealthy members of the rapidly growing

One of Catt's first actions as president was to implement the "society plan," a campaign to recruit wealthy members of the rapidly growing women's club

The woman's club movement was a social movement that took place throughout the United States that established the idea that women had a moral duty and responsibility to transform public policy. While women's organizations had always been a part ...

movement, whose time, money and experience could help build the suffrage movement.

Primarily composed of middle-class women, the targeted clubs often engaged in civic improvement projects. They generally avoided controversial issues, but women's suffrage increasingly found acceptance among their membership.

In 1914, suffrage was endorsed by the General Federation of Women's Clubs

The General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), founded in 1890 during the Progressive Movement, is a federation of over 3,000 women's clubs in the United States which promote civic improvements through volunteer service. Many of its activities ...

, the national body for the club movement.

To make the suffrage movement more attractive to middle- and upper-class women, the NAWSA began to popularize a version of the movement's history that downplayed the earlier involvement of many of its members with such controversial issues as racial equality, divorce reform, working women's rights and critiques of organized religion. Stanton's role in the movement was obscured by this process, as were the roles of black and working women.

Anthony, who in her younger days was often treated as a dangerous fanatic, was given a grandmotherly image and honored as a "suffrage saint."

The reform energy of the

The reform energy of the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

strengthened the suffrage movement during this period. Beginning around 1900, this broad movement began at the grassroots level with such goals as combating corruption in government, eliminating child labor, and protecting workers and consumers. Many of its participants saw women's suffrage as yet another progressive goal, and they believed that the addition of women to the electorate would help the movement achieve its other goals.

Catt resigned her position after four years, partly because of her husband's declining health and partly to help organize the International Woman Suffrage Alliance

The International Alliance of Women (IAW; french: Alliance Internationale des Femmes, AIF) is an international non-governmental organization that works to promote women's rights and gender equality. It was historically the main international org ...

, which was created in Berlin in 1904 in coordination with the NAWSA and with Catt as president.

Shaw presidency

In 1904,Anna Howard Shaw

Anna Howard Shaw (February 14, 1847 – July 2, 1919) was a leader of the women's suffrage movement in the United States. She was also a physician and one of the first ordained female Methodist ministers in the United States.

Early life

Shaw ...

, another Anthony protégé, was elected president of the NAWSA, serving more years in that office than any other person. Shaw was an energetic worker and a talented orator. Her administrative and interpersonal skills did not match those that Catt would display during her second term in office, but the organization made striking gains under Shaw's leadership.

In 1906, southern NAWSA members formed the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference with Blackwell's encouragement. Although it had a frankly racist program, it asked for NAWSA's endorsement. Shaw refused, setting a limit on how far the organization was willing to go to accommodate southerners with overtly racist views. Shaw said the organization would not adopt policies that "advocated the exclusion of any race or class from the right of suffrage."

In 1907, partly in reaction to NAWSA's "society plan", which was designed to appeal to upper-class women,

In 1906, southern NAWSA members formed the Southern Woman Suffrage Conference with Blackwell's encouragement. Although it had a frankly racist program, it asked for NAWSA's endorsement. Shaw refused, setting a limit on how far the organization was willing to go to accommodate southerners with overtly racist views. Shaw said the organization would not adopt policies that "advocated the exclusion of any race or class from the right of suffrage."

In 1907, partly in reaction to NAWSA's "society plan", which was designed to appeal to upper-class women, Harriet Stanton Blatch

Harriot Eaton Blatch ( Stanton; January 20, 1856–November 20, 1940) was an American writer and suffragist. She was the daughter of pioneering women's rights activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Biography

Harriot Eaton Stanton was born, the sixth ...

, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, formed a competing organization called the Equality League of Self-Supporting Women.

Later known as the Women's Political Union, its membership was based on working women, both professional and industrial. Blatch had recently returned to the United States after several years in England, where she had worked with suffrage groups in the early phases of employing militant tactics as part of their campaign. The Equality League gained a following by engaging in activities that many members of the NAWSA initially considered too daring, such as suffrage parades and open air rallies.

Blatch said that when she joined the suffrage movement in the U.S., "The only method suggested for furthering the cause was the slow process of education. We were told to organize, organize, organize, to the end of educating, educating, educating public opinion."

In 1908, the National College Equal Suffrage League was formed as an affiliate of the NAWSA. It had its origins in the College Equal Suffrage League, which was formed in Boston in 1900 at a time when there were relatively few college students in the NAWSA. It was established by Maud Wood Park

Maud Wood Park (January 25, 1871 – May 8, 1955) was an American suffragist and women's rights activist.

Career overview

She was born in Boston, Massachusetts. In 1887 she graduated from St. Agnes School in Albany, New York, after which she ta ...

, who later helped create similar groups in 30 states. Park later became a prominent leader of the NAWSA.

By 1908, Catt was once again at the forefront of activity. She and her co-workers developed a detailed plan to unite the various suffrage associations in New York City (and later in the entire state) in an organization modeled on political machines like Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

. In 1909, they founded the Woman Suffrage Party (WSP) at a convention attended by over a thousand delegates and alternates. By 1910, the WSP had 20,000 members and a four-room headquarters. Shaw was not entirely comfortable with the independent initiatives of the WSP, but Catt and other of its leaders remained loyal to the NAWSA, its parent organization.

In 1909, Frances Squires Potter, a NAWSA member from Chicago, proposed the creation of suffrage community centers called "political settlements." Reminiscent of the social settlement houses

The settlement movement was a reformist social movement that began in the 1880s and peaked around the 1920s in United Kingdom and the United States. Its goal was to bring the rich and the poor of society together in both physical proximity and ...

, such as Hull House

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, United States that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of the city, Hull House (named after the original house's first owner Cha ...

in Chicago, their purpose was to educate the public about suffrage and the practical details of political activity at the local level. The political settlements established by the WSP included suffrage schools that provided training in public speaking to suffrage organizers.

Public sentiment toward the suffrage movement improved dramatically during this period. Working for suffrage came to be seen as a respectable activity for middle-class women. By 1910, NAWSA membership had jumped to 117,000.

The NAWSA established its first permanent headquarters that year in New York City, previously having operated mainly out of the homes of its officers.

Maud Wood Park, who had been away in Europe for two years, received a letter that year from one of her co-workers in the College Equal Suffrage League who described the new atmosphere by saying, "the movement which when we got into it had about as much energy as a dying kitten, is now a big, virile, threatening thing" and is "actually fashionable now."

The change in public sentiment was reflected in efforts to win suffrage at the state level. In 1896, only four states, all of them in the West, allowed women to vote. From 1896 to 1910, there were six state campaigns for suffrage, and they all failed. The tide began to turn in 1910 when suffrage was won in the state of Washington, followed by California in 1911, Oregon, Kansas and Arizona in 1912, and others afterwards.

In 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois, president of the

In 1912, W. E. B. Du Bois, president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States, formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. ...

(NAACP), publicly challenged NAWSA's reluctance to accept black women. The NAWSA responded in a cordial way, inviting him to speak at its next convention and publishing his speech as a pamphlet.

Nonetheless the NAWSA continued to minimize the role of black suffragists. It accepted some black women as members and some black societies as auxiliaries, but its general practice was to turn such requests politely away.

This was partly because attitudes of racial superiority were the norm among white Americans of that era, and partly because the NAWSA believed it had little hope of achieving a national amendment without at least some support from southern states that practiced racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

.

NAWSA's strategy at that point was to gain suffrage for women on a state-by-state basis until it achieved a critical mass of voters that could push through a suffrage amendment at the national level.

In 1913, the Southern States Woman Suffrage Committee was formed in an attempt to stop that process from moving past the state level. It was led by Kate Gordon, who had been the NAWSA's corresponding secretary from 1901 to 1909.

Gordon, who was from the southern state of Louisiana, supported women's suffrage, but opposed the idea of a federal suffrage amendment, charging that it would violate states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

. She said that empowering federal authorities to enforce a constitutional right for women to vote in the South could lead to similar enforcement of the constitutional right of African Americans to vote there, a right that was being evaded, and, in her opinion, rightly so. Her committee was too small to seriously affect the NAWSA's direction, but her public condemnation of the proposed amendment, expressed in terms of vehement racism, deepened fissures within the organization.

Despite the rapid growth in NAWSA membership, discontent with Shaw grew. Her tendency to overreact to those who differed with her had the effect of increasing organizational friction.

Several members resigned from executive board in 1910, and the board saw significant changes in its composition every year after that through 1915.

In 1914, Senator John Shafroth introduced a federal amendment that would require state legislatures to put women's suffrage on the state ballot if eight percent of the voters signed a petition to that effect. The NAWSA endorsed the proposed amendment, whereupon the CU accused it of abandoning the drive for a national suffrage amendment. Amid confusion among the membership, delegates at the 1914 convention directed their dissatisfaction at Shaw.

Shaw had considered declining the presidency in 1914, but decided to run again. In 1915, she announced that she would not be running for reelection.

Relocation to Warren, Ohio

For several years, Harriet Taylor Upton led the woman suffragist movement in Trumbull County, Ohio. In 1880, Upton's father was elected as a member of theUnited States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

as a Republican from Ohio. This connection provided Upton the opportunity to meet Susan B. Anthony, who brought Upton into the suffragist movement.

In 1894, Upton was elected as the NAWSA's treasurer. In addition, Upton served as president of the Ohio association of the national association, from 1899-1908 and 1911–1920. Upton helped relocate the national headquarters for the NAWSA to her home in Warren, Ohio

Warren is a city in and the county seat of Trumbull County, Ohio, United States. Located in northeastern Ohio, Warren lies approximately northwest of Youngstown and southeast of Cleveland. The population was 39,201 at the 2020 census. The hi ...

, in 1903. According to the Tribune Chronicle

The ''Tribune Chronicle'' is a daily morning newspaper serving Warren, Ohio and the Mahoning Valley area of the United States. The newspaper claims to be the second oldest in the U.S. state of Ohio.

, "it was only supposed to be a temporary move, but it lasted six years. Susan B. Anthony, noted leader of the women's movement, visited Warren many times, including a 1904 trip to attend a national women's rights meeting here."

During this period, the nation's attention regarding women's rights was focused on Warren. The association's offices were located on the ground level of the Trumbull Court House, a building currently occupied by the Probate Court. While the headquarters left the Upton House around 1910, Warren remained active in the suffrage movement. The people of Warren were active in various programs of the national movement for years, until the 19th Amendment was ratified by a sufficient number of states, and authorized by President Wilson in 1920.

In 1993, the Upton House joined the list of historic landmarks.

Split in the movement

A serious challenge to the NAWSA leadership began to develop after a young activist named Alice Paul returned to the U.S. from England in 1910, where she had been part of the militant wing of the suffrage movement. She had been jailed there and had endured forced feedings after going on a hunger strike. Joining the NAWSA, she became the person most responsible for reviving interest within the suffrage movement for a national amendment, which for years had been overshadowed by campaigns for suffrage at the state level. From Shaw's point of view, the time was right for a renewed emphasis on a suffrage amendment. Gordon and Clay, the most persistent adversaries of a federal suffrage amendment within NAWSA, had been out-maneuvered by their opponents and no longer held national posts.

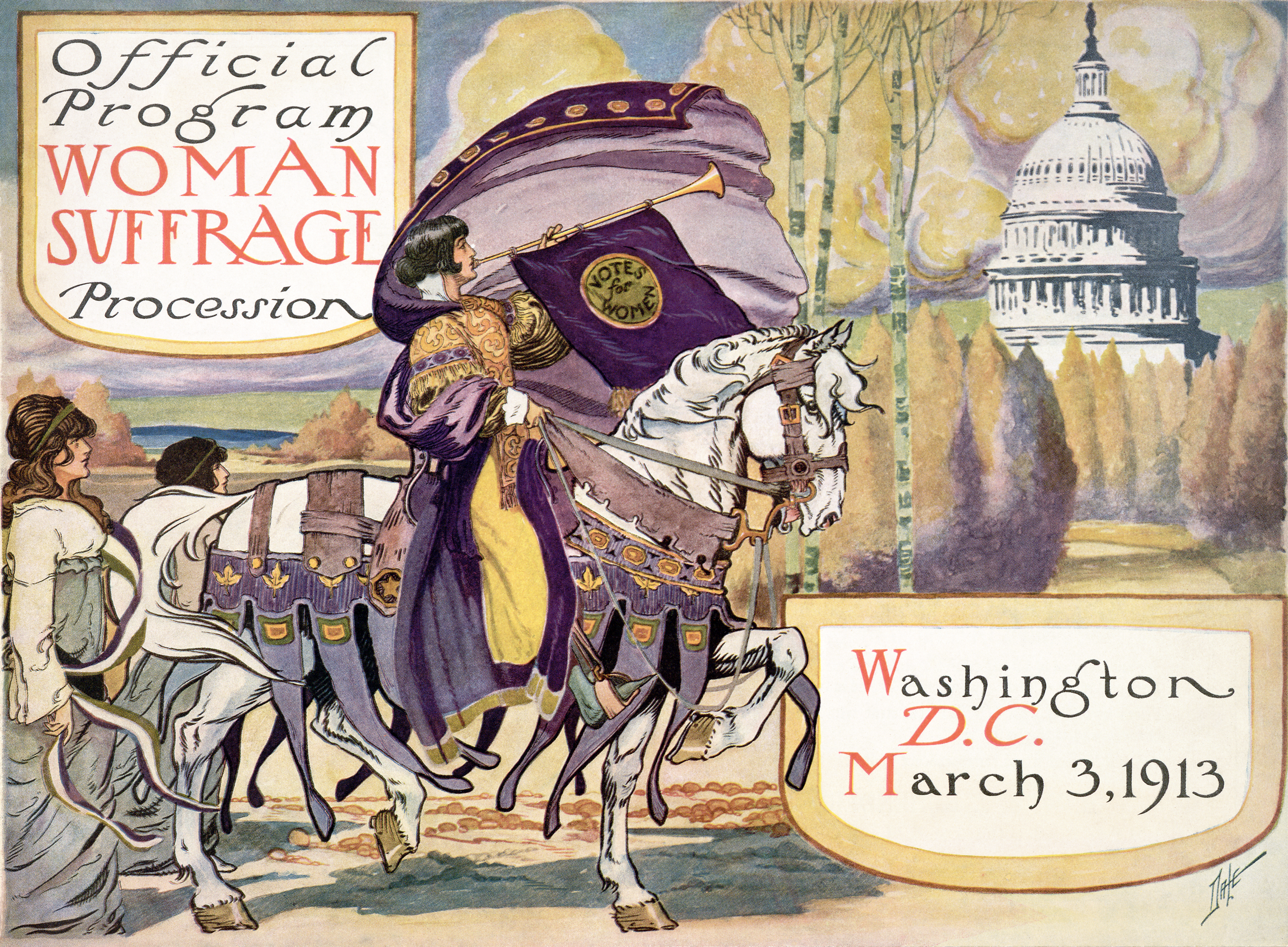

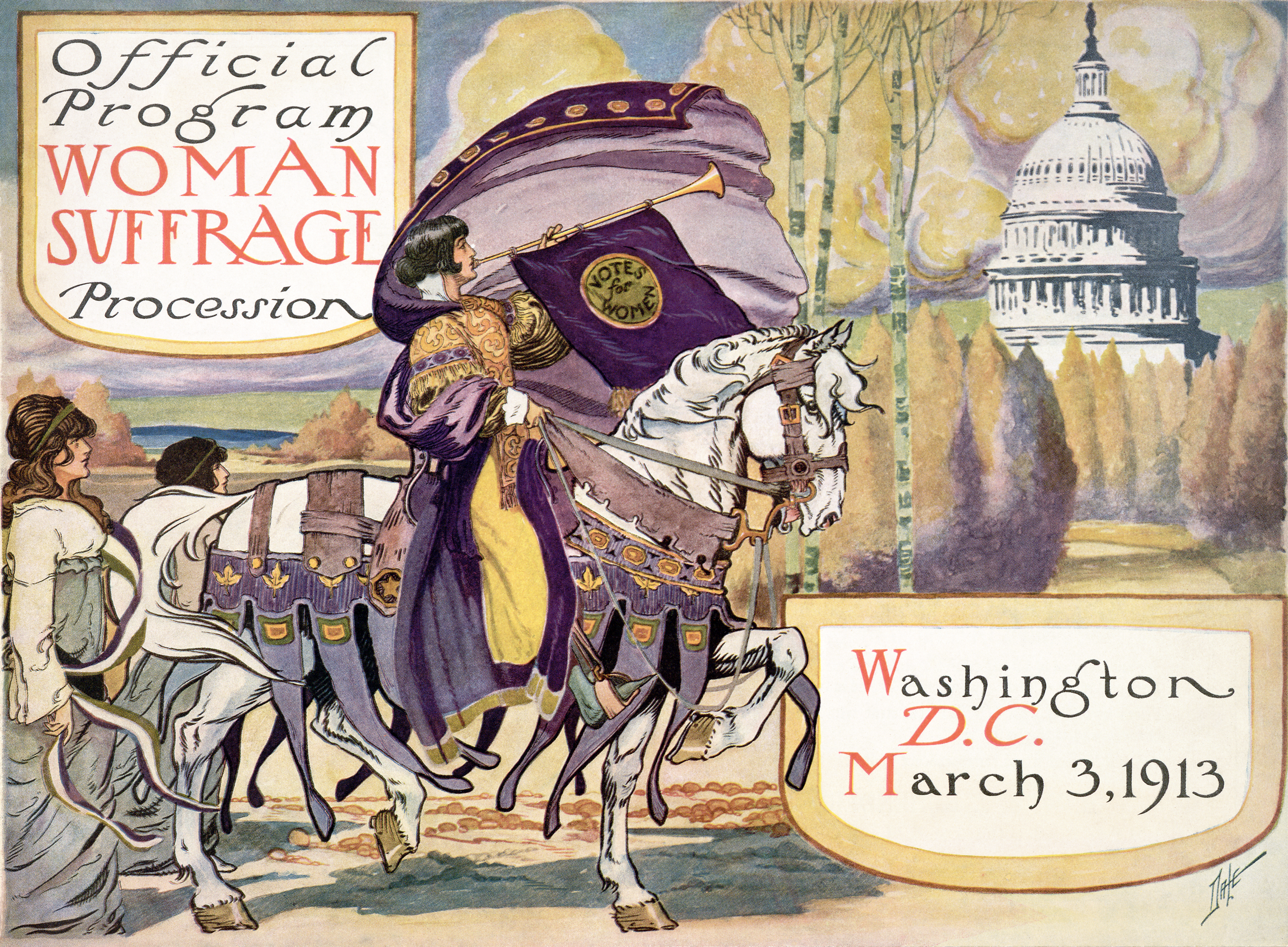

In 1912, Alice Paul was appointed chair of NAWSA's Congressional Committee and charged with reviving the drive for a women's suffrage amendment. In 1913, she and her coworker

From Shaw's point of view, the time was right for a renewed emphasis on a suffrage amendment. Gordon and Clay, the most persistent adversaries of a federal suffrage amendment within NAWSA, had been out-maneuvered by their opponents and no longer held national posts.

In 1912, Alice Paul was appointed chair of NAWSA's Congressional Committee and charged with reviving the drive for a women's suffrage amendment. In 1913, she and her coworker Lucy Burns

Lucy Burns (July 28, 1879 – December 22, 1966) was an American suffragist and women's rights advocate.Bland, 1981 (p. 8) She was a passionate activist in the United States and the United Kingdom, who joined the militant suffragettes. Burns ...

organized the Woman Suffrage Procession

The Woman Suffrage Procession on 3 March 1913 was the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C. It was also the first large, organized march on Washington for political purposes. The procession was organized by the suffragists Alice Paul and ...

, a suffrage parade in Washington on the day before Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's inauguration as president. Onlookers who opposed the march turned the event into a near riot, which ended only when a cavalry unit of the army was brought in to restore order. Public outrage over the incident, which cost the chief of police his job, brought publicity to the movement and gave it fresh momentum.

Paul troubled NAWSA leaders by arguing that because Democrats would not act to enfranchise women even though they controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress, the suffrage movement should work for the defeat of all Democrats regardless of an individual candidate's position on suffrage. NAWSA's policy was to follow the opposite approach, supporting any candidate who endorsed suffrage, regardless of political party.

In 1913, Paul and Burns formed the Congressional Union (CU) to work solely for a national amendment and sent organizers into states that already had NAWSA organizations. The relationship between the CU and the NAWSA became unclear and troubled over time.

At the NAWSA convention in 1913, Paul and her allies demanded that the organization focus its efforts on a federal suffrage amendment. The convention instead empowered the executive board to limit the CU's ability to contravene NAWSA policies. After negotiations failed to resolve their differences, the NAWSA removed Paul as head of its Congressional Committee. By February, 1914, the NAWSA and the CU had effectively separated into two independent organizations.

Blatch merged her Women's Political Union into the CU.

That organization in turn became the basis for the National Woman's Party

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NW ...

(NWP), which Paul formed in 1916.

Once again there were two competing national women's suffrage organizations, but the result this time was something like a division of labor. The NAWSA burnished its image of respectability and engaged in highly organized lobbying at both the national and state levels. The smaller NWP also engaged in lobbying but became increasingly known for activities that were dramatic and confrontational, most often in the national capital.

Second Catt presidency, 1915-1920

Carrie Chapman Catt

Carrie Chapman Catt (; January 9, 1859 Fowler, p. 3 – March 9, 1947) was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt ...

, the NAWSA's previous president, was the obvious choice to replace Anna Howard Shaw, but Catt was leading the New York State Woman Suffrage Party, which was in the early stages of a crucial suffrage campaign in that state.

The prevailing belief in the NAWSA was that success in a large eastern state would be the tipping point for the national campaign.

New York was the largest state in the union, and victory there was a real possibility. Catt agreed to turn the New York work over to others and to accept the NAWSA presidency in December, 1915 on the condition that she could name her own executive board, which previously had always been elected by the annual convention. She appointed to the board women of independent means who could work for the movement full-time.

Backed by an increased level of commitment and unity in the national office, Catt sent its officers into the field to assess the state of the organization and start the process of reorganizing it into a more centralized and efficient operation. Catt described the NAWSA as a camel with a hundred humps, each with a blind driver trying to lead the way. She provided a new sense of direction by sending out a stream of communications to state and local affiliates with policy directives, organizational initiatives and detailed plans of work.

The NAWSA previously had devoted much of its effort to educating the public about suffrage, and it had made a significant impact. Women's suffrage had become a major national issue, and the NAWSA was in the process of becoming the nation's largest voluntary organization, with two million members.

Catt built on that foundation to convert the NAWSA into an organization that operated primarily as a political pressure group.

1916

At an executive board meeting in March, 1916, Catt described the organization's dilemma by saying, "The Congressional Union is drawing off from the National Association those women who feel it is possible to work for suffrage by the Federal route only. Certain workers in the south are being antagonized because the National is continuing to work for the Federal Amendment. The combination has produced a great muddle". Catt believed that NAWSA's policy of working primarily on state-by-state campaigns was nearing its limits. Some states appeared unlikely ever to approve women's suffrage, in some cases because state laws made constitutional revision extremely difficult, and in others, especially in the Deep South, because opposition was simply too strong. Catt refocused the organization on a national suffrage amendment while continuing to conduct state campaigns where success was a realistic possibility. When the conventions of the Democratic and Republican parties met in June, 1916, suffragists applied pressure to both. Catt was invited to express her views in a speech to the Republican convention in Chicago. An anti-suffragist spoke after Catt, and as she was telling the convention that women did not want to vote, a crowd of suffragists burst into the hall and filled the aisles. They were soaking wet, having marched in heavy rain for several blocks in a parade led by two elephants. When the flustered anti-suffragist concluded her remarks, the suffragists led a cheer for their cause. At the Democratic convention a week later in St. Louis, suffragists packed the galleries and made their views known during the debate on suffrage. Both party conventions endorsed women's suffrage but only at the state level, which meant that different states might implement it in different ways and in some cases not at all. Having expected more, Catt called an Emergency Convention, moving the date of the 1916 convention from December to September to begin organizing a renewed push for the federal amendment. The convention initiated a strategic shift by adopting Catt's "Winning Plan". This plan mandated work toward the national suffrage amendment as the priority for the entire organization and authorized the creation of a professional lobbying team to support this goal in Washington. It authorized the executive board to specify a plan of work toward this goal for each state and to take over that work if the state organization refused to comply. It agreed to fund state suffrage campaigns only if they met strict requirements that were designed to eliminate efforts with little chance of succeeding. Catt's plan included milestones for achieving a women's suffrage amendment by 1922. Gordon, whose states' rights approach had been decisively defeated, exclaimed to a friend, "A well-oiled steam roller has ironed this convention flat!" President Wilson, whose attitude toward women's suffrage was evolving, spoke at the 1916 NAWSA convention. He had been considered an opponent of suffrage when he was governor of New Jersey, but in 1915 he announced that he was traveling from the White House back to his home state to vote in favor of it in New Jersey's state referendum. He spoke favorably of suffrage at the NAWSA convention but stopped short of supporting the suffrage amendment.Charles Evans Hughes

Charles Evans Hughes Sr. (April 11, 1862 – August 27, 1948) was an American statesman, politician and jurist who served as the 11th Chief Justice of the United States from 1930 to 1941. A member of the Republican Party, he previously was the ...

, his opponent in the presidential election that year, declined to speak at the convention, but he went farther than Wilson by endorsing the suffrage amendment.

NAWSA's Congressional Committee had been in disarray ever since Alice Paul was removed from it in 1913. Catt reorganized the committee and appointed Maud Wood Park as its head in December, 1916. Park and her lieutenant Helen Hamilton Gardener created what became known as the "Front Door Lobby", so named by a journalist because it operated openly, avoiding the traditional lobbying methods of "backstairs" dealing. A headquarters for the lobbying effort was established in a dilapidated mansion known as Suffrage House. NAWSA lobbyists lodged there and coordinated their activities with daily conferences in its meeting rooms.

In 1916 the NAWSA purchased the ''

NAWSA's Congressional Committee had been in disarray ever since Alice Paul was removed from it in 1913. Catt reorganized the committee and appointed Maud Wood Park as its head in December, 1916. Park and her lieutenant Helen Hamilton Gardener created what became known as the "Front Door Lobby", so named by a journalist because it operated openly, avoiding the traditional lobbying methods of "backstairs" dealing. A headquarters for the lobbying effort was established in a dilapidated mansion known as Suffrage House. NAWSA lobbyists lodged there and coordinated their activities with daily conferences in its meeting rooms.

In 1916 the NAWSA purchased the ''Woman's Journal

''Woman's Journal'' was an American women's rights periodical published from 1870 to 1931. It was founded in 1870 in Boston, Massachusetts, by Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Browne Blackwell as a weekly newspaper. In 1917 it was purchased by ...

'' from Alice Stone Blackwell. The newspaper had been established in 1870 by Blackwell's mother, Lucy Stone, and had served as the primary voice of the suffrage movement most of the time since then. It had significant limitations, however. It was a small operation, with Blackwell herself doing most of the work, and with much of its reporting centered on the eastern part of the country at a time when a national newspaper was needed.

After the transfer, it was renamed ''Woman Citizen'' and merged with ''The Woman Voter'', the journal of the Woman Suffrage Party of New York City, and with ''National Suffrage News'', the former journal of the NAWSA."The record of the Leslie woman suffrage commission, inc., 1917–1929", by Rose Young./ref> The newspaper's masthead declared itself to be the NAWSA's official organ.

1917

In 1917 Catt received abequest

A bequest is property given by will. Historically, the term ''bequest'' was used for personal property given by will and ''deviser'' for real property. Today, the two words are used interchangeably.

The word ''bequeath'' is a verb form for the act ...

of $900,000 from Mrs. Frank (Miriam) Leslie to be used as she thought best for the women's suffrage movement. Catt allocated most of the funds to the NAWSA, with $400,000 applied toward upgrading the ''Woman Citizen''.

In January 1917, Alice Paul's NWP began picketing the White House with banners that demanded women's suffrage. The police eventually arrested over 200 of the Silent Sentinels

The Silent Sentinels, also known as the Sentinels of Liberty, were a group of over 2,000 women in favor of women's suffrage organized by Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, who protested in front of the White House during Woodrow Wilson's ...

, many of whom went on hunger strike after being imprisoned. The prison authorities force fed

Force-feeding is the practice of feeding a human or animal against their will. The term ''gavage'' (, , ) refers to supplying a substance by means of a small plastic feeding tube passed through the nose ( nasogastric) or mouth (orogastric) into t ...

them, creating an uproar that fueled public debate on women's suffrage.

When the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, the NAWSA cooperated with the war effort. Shaw was appointed as head of the Women's Committee for the Council of National Defense

The Council of National Defense was a United States organization formed during World War I to coordinate resources and industry in support of the war effort, including the coordination of transportation, industrial and farm production, financial s ...

, which was established by the federal government to coordinate resources for the war and to promote public morale. Catt and two other NAWSA members were appointed to its executive committee.

The NWP, by contrast, took no part in the war effort and charged that the NAWSA did so at the expense of suffrage work.

In April 1917, Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 – May 18, 1973) was an American politician and women's rights advocate who became the first woman to hold federal office in the United States in 1917. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representa ...

of Montana took her seat as the first woman in Congress, having previously served as lobbyist and field secretary for the NAWSA. Rankin voted against the declaration of war.

In November 1917, the suffrage movement achieved a major victory when a referendum to enfranchise women passed by a large margin in New York, the most populous state in the country.

The powerful Tammany Hall political machine, which had previously opposed suffrage, took a neutral stance on this referendum, partly because the wives of several Tammany Hall leaders played prominent roles in the suffrage campaign.