Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a

Nordic country

The Nordic countries (also known as the Nordics or ''Norden''; lit. 'the North') are a geographical and cultural region in Northern Europe and the North Atlantic. It includes the sovereign states of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Swed ...

in

Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe Northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54th parallel north, 54°N, or may be based on other g ...

, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the

Scandinavian Peninsula

The Scandinavian Peninsula ( sv, Skandinaviska halvön; no, Den skandinaviske halvøy (Bokmål) or nn, Den skandinaviske halvøya; fi, Skandinavian niemimaa) is a peninsula located in Northern Europe, which roughly comprises the mainlands ...

. The remote Arctic island of

Jan Mayen

Jan Mayen () is a Norwegian volcanic island in the Arctic Ocean with no permanent population. It is long (southwest-northeast) and in area, partly covered by glaciers (an area of around the Beerenberg volcano). It has two parts: larger nort ...

and the

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

of

Svalbard

Svalbard ( , ), also known as Spitsbergen, or Spitzbergen, is a Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean. North of mainland Europe, it is about midway between the northern coast of Norway and the North Pole. The islands of the group range ...

also form part of Norway.

Bouvet Island

Bouvet Island ( ; or ''Bouvetøyen'') is an island claimed by Norway, and declared an uninhabited protected nature reserve. It is a subantarctic volcanic island, situated in the South Atlantic Ocean at the southern end of the Mid-Atlantic Ri ...

, located in the

Subantarctic

The sub-Antarctic zone is a region in the Southern Hemisphere, located immediately north of the Antarctic region. This translates roughly to a latitude of between 46° and 60° south of the Equator. The subantarctic region includes many islands ...

, is a

dependency of Norway

Norway has three dependent territories ( no, biland), all uninhabited and located in the Southern Hemisphere. Bouvet Island (Bouvetøya) is a sub-Antarctic island in the South Atlantic Ocean. Queen Maud Land is a sector of Antarctica which spans ...

; it also

lays claims to the Antarctic territories of

Peter I Island

Peter I Island ( no, Peter I Øy) is an uninhabited volcanic island in the Bellingshausen Sea, from continental Antarctica. It is claimed as a dependency of Norway and, along with Bouvet Island and Queen Maud Land, composes one of the three No ...

and

Queen Maud Land

Queen Maud Land ( no, Dronning Maud Land) is a roughly region of Antarctica claimed by Norway as a dependent territory. It borders the claimed British Antarctic Territory 20° west and the Australian Antarctic Territory 45° east. In addit ...

. The capital and largest city in Norway is

Oslo

Oslo ( , , or ; sma, Oslove) is the capital and most populous city of Norway. It constitutes both a county and a municipality. The municipality of Oslo had a population of in 2022, while the city's greater urban area had a population of ...

.

Norway has a total area of

and had a population of 5,425,270 in January 2022.

The country shares a long eastern border with

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden,The United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names states that the country's formal name is the Kingdom of SwedenUNGEGN World Geographical Names, Sweden./ref> is a Nordic country located on ...

at a length of

. It is bordered by

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

and

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

to the northeast and the

Skagerrak

The Skagerrak (, , ) is a strait running between the Jutland peninsula of Denmark, the southeast coast of Norway and the west coast of Sweden, connecting the North Sea and the Kattegat sea area through the Danish Straits to the Baltic Sea.

The ...

strait to the south, on the other side of which are

Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark

...

and the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

. Norway has an extensive coastline, facing the North Atlantic Ocean and the

Barents Sea

The Barents Sea ( , also ; no, Barentshavet, ; russian: Баренцево море, Barentsevo More) is a marginal sea of the Arctic Ocean, located off the northern coasts of Norway and Russia and divided between Norwegian and Russian territo ...

. The maritime influence dominates Norway's climate, with mild lowland temperatures on the sea coasts; the interior, while colder, is also significantly milder than areas elsewhere in the world on such northerly latitudes. Even during

polar night

The polar night is a phenomenon where the nighttime lasts for more than 24 hours that occurs in the northernmost and southernmost regions of Earth. This occurs only inside the polar circles. The opposite phenomenon, the polar day, or midnig ...

in the north, temperatures above freezing are commonplace on the coastline. The maritime influence brings high rainfall and snowfall to some areas of the country.

Harald V

Harald V ( no, Harald den femte, ; born 21 February 1937) is King of Norway. He acceded to the throne on 17 January 1991.

Harald was the third child and only son of King Olav V of Norway and Princess Märtha of Sweden. He was second in the lin ...

of the

House of Glücksburg

The House of Glücksburg (also spelled ''Glücksborg'' or ''Lyksborg''), shortened from House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, is a collateral branch of the German House of Oldenburg, members of which have reigned at various times ...

is the current

King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingdoms ...

.

Jonas Gahr Støre

Jonas Gahr Støre (; born 25 August 1960) is a Norwegian politician who has served as the prime minister of Norway since 2021 and has been Leader of the Labour Party since 2014. He served under Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg as Minister of For ...

has been prime minister since 2021, replacing

Erna Solberg

Erna Solberg (; born 24 February 1961) is a Norwegian politician and the current Leader of the Opposition. She served as the 35th prime minister of Norway from 2013 to 2021, and has been Leader of the Conservative Party since May 2004.

Solberg wa ...

. As a

unitary

Unitary may refer to:

Mathematics

* Unitary divisor

* Unitary element

* Unitary group

* Unitary matrix

* Unitary morphism

* Unitary operator

* Unitary transformation

* Unitary representation

* Unitarity (physics)

* ''E''-unitary inverse semigroup ...

sovereign state

A sovereign state or sovereign country, is a polity, political entity represented by one central government that has supreme legitimate authority over territory. International law defines sovereign states as having a permanent population, defin ...

with a

constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, Norway

divides state power between the

parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

, the

cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

and the

supreme court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, as determined by the

1814 constitution. The kingdom was established in 872 as a merger of many

petty kingdoms

A petty kingdom is a kingdom described as minor or "petty" (from the French 'petit' meaning small) by contrast to an empire or unified kingdom that either preceded or succeeded it (e.g. the numerous kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England unified into th ...

and has existed continuously for 1, years. From 1537 to 1814, Norway was a part of the Kingdom of

Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway (Danish and Norwegian: ) was an early modern multi-national and multi-lingual real unionFeldbæk 1998:11 consisting of the Kingdom of Denmark, the Kingdom of Norway (including the then Norwegian overseas possessions: the Faroe I ...

, and, from 1814 to 1905, it was in a

personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with the Kingdom of Sweden. Norway was neutral during the

First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, and also in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

until April 1940 when the country was

invaded

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

and

occupied

' (Norwegian: ') is a Norwegian political thriller TV series that premiered on TV2 on 5 October 2015. Based on an original idea by Jo Nesbø, the series is co-created with Karianne Lund and Erik Skjoldbjærg. Season 2 premiered on 10 October ...

by

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

until the end of the war.

Norway has both administrative and political subdivisions on two levels:

counties

A county is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesChambers Dictionary, L. Brookes (ed.), 2005, Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, Edinburgh in certain modern nations. The term is derived from the Old French ...

and

municipalities

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality'' may also mean the go ...

. The

Sámi people

The Sámi ( ; also spelled Sami or Saami) are a Finno-Ugric languages#Speakers, Finno-Ugric-speaking people inhabiting the region of Sápmi (formerly known as Lapland), which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, ...

have a certain amount of self-determination and influence over traditional territories through the

Sámi Parliament

The Sámi ( ; also spelled Sami or Saami) are a Finno-Ugric-speaking people inhabiting the region of Sápmi (formerly known as Lapland), which today encompasses large northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and of the Murmansk Oblast, R ...

and the

Finnmark Act

The Finnmark Act () of 2005 transferred about 96% (about 46,000 km2) of the area in the Finnmark county in Norway to the inhabitants of Finnmark. This area is managed by the Finnmark Estate agency.

The Finnmark Estate is managed by a board of dir ...

. Norway

maintains close ties with both the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

and the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. Norway is also a founding member of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

,

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, the

European Free Trade Association

The European Free Trade Association (EFTA) is a regional trade organization and free trade area consisting of four List of sovereign states and dependent territories in Europe, European states: Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerlan ...

, the

Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold European Convention on Human Rights, human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. ...

, the

Antarctic Treaty

russian: link=no, Договор об Антарктике es, link=no, Tratado Antártico

, name = Antarctic Treaty System

, image = Flag of the Antarctic Treaty.svgborder

, image_width = 180px

, caption ...

, and the

Nordic Council

The Nordic Council is the official body for formal inter-parliamentary Nordic cooperation among the Nordic countries. Formed in 1952, it has 87 representatives from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden as well as from the autonomou ...

; a member of the

European Economic Area

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the ''Agreement on the European Economic Area'', an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade Ass ...

, the

WTO

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and e ...

, and the

OECD

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; french: Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques, ''OCDE'') is an intergovernmental organisation with 38 member countries, founded in 1961 to stimulate e ...

; and a part of the

Schengen Area

The Schengen Area ( , ) is an area comprising 27 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and all other types of border control at their mutual borders. Being an element within the wider area of freedom, security and j ...

. In addition, the Norwegian languages share

mutual intelligibility

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is a relationship between languages or dialects in which speakers of different but related varieties can readily understand each other without prior familiarity or special effort. It is sometimes used as an ...

with

Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

and

Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

.

Norway maintains the

Nordic welfare model

The Nordic model comprises the economic and social policies as well as typical cultural practices common to the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden). This includes a comprehensive welfare state and multi-level co ...

with

universal health care

Universal health care (also called universal health coverage, universal coverage, or universal care) is a health care system in which all residents of a particular country or region are assured access to health care. It is generally organized ar ...

and a comprehensive

social security

Welfare, or commonly social welfare, is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specificall ...

system, and its values are rooted in egalitarian ideals. The Norwegian state has large ownership positions in key industrial sectors, having extensive reserves of petroleum, natural gas, minerals, lumber, seafood, and fresh water. The

petroleum industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry or the oil patch, includes the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transportation (often by oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing of petroleum products. The larges ...

accounts for around a quarter of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). On a

per-capita basis, Norway is the world's largest producer of oil and natural gas outside of the Middle East.

The country has the

fourth-highest per-capita income in the world on the

World Bank

The World Bank is an international financial institution that provides loans and grants to the governments of low- and middle-income countries for the purpose of pursuing capital projects. The World Bank is the collective name for the Interna ...

and

IMF lists. On the

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

's GDP (PPP) per capita list (2015 estimate) which includes autonomous territories and regions, Norway ranks as number eleven. It has the world's largest

sovereign wealth fund

A sovereign wealth fund (SWF), sovereign investment fund, or social wealth fund is a state-owned investment fund that invests in real and financial assets such as stocks, bonds, real estate, precious metals, or in alternative investments such ...

, with a value of US$1 trillion. Norway has the second highest

Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, whi ...

ranking in the world, previously holding the top position between 2001 and 2006, and between 2009 and 2019;

it also has the second highest

inequality-adjusted ranking per 2021. Norway ranked first on the

World Happiness Report

The World Happiness Report is a publication that contains articles and rankings of Gross National Happiness, national happiness, based on respondent ratings of their own lives, which the report also correlates with various Quality of life, (qualit ...

for 2017 and currently ranks first on the

OECD Better Life Index

The OECD Better Life Index, created in May 2011 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, is an initiative pioneering the development of economic indicators which better capture multiple dimensions of economic and social progre ...

, the

Index of Public Integrity, the

Freedom Index, and the

Democracy Index

The ''Democracy Index'' is an index compiled by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), the research division of the Economist Group, a UK-based private company which publishes the weekly newspaper ''The Economist''. Akin to a Human Development I ...

. Norway also has one of the lowest crime rates in the world.

Although the majority of Norway's population is ethnic Norwegian, in the 21st century immigration has accounted for more than half of population growth; in 2021, the five largest minority groups in the country were the descendants of

Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

,

Lithuanian,

Somali,

Pakistani, and

Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

immigrants.

Etymology

Norway has two official names: ''Norge'' in

Bokmål

Bokmål () (, ; ) is an official written standard for the Norwegian language, alongside Nynorsk. Bokmål is the preferred written standard of Norwegian for 85% to 90% of the population in Norway. Unlike, for instance, the Italian language, there ...

and ''Noreg'' in

Nynorsk

Nynorsk () () is one of the two written standards of the Norwegian language, the other being Bokmål. From 12 May 1885, it became the state-sanctioned version of Ivar Aasen's standard Norwegian language ( no, Landsmål) parallel to the Dano-Nor ...

. The English name Norway comes from the

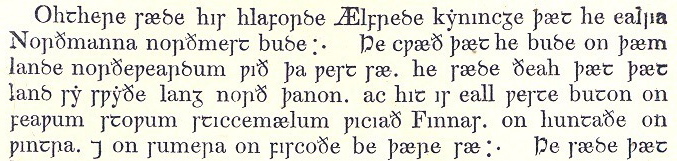

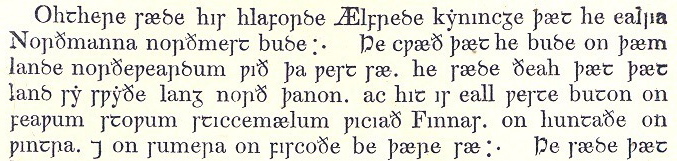

Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

word ''Norþweg'' mentioned in 880, meaning "northern way" or "way leading to the north", which is how the

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a Cultural identity, cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo- ...

s referred to the coastline of Atlantic Norway

similar to leading theory about the origin of the Norwegian language name. The Anglo-Saxons of Britain also referred to the kingdom of Norway in 880 as ''Norðmanna land''.

There is some disagreement about whether the native name of Norway originally had the same etymology as the English form. According to the traditional dominant view, the first component was originally

''norðr'', a

cognate

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words in different languages that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymology, etymological ancestor in a proto-language, common parent language. Because language c ...

of English ''north'', so the full name was ''Norðr

vegr'', "the way northwards", referring to the sailing route along the Norwegian coast, and contrasting with ''suðrvegar'' "southern way" (from

Old Norse

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian, is a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and t ...

suðr) for (Germany), and ''austrvegr'' "eastern way" (from

austr) for the

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

. In the translation of

Orosius

Paulus Orosius (; born 375/385 – 420 AD), less often Paul Orosius in English, was a Roman priest, historian and theologian, and a student of Augustine of Hippo. It is possible that he was born in '' Bracara Augusta'' (now Braga, Portugal), t ...

for Alfred, the name is ''Norðweg'', while in younger Old English sources the ð is gone.

In the tenth century many Norsemen settled in Northern France, according to the sagas, in the area that was later called

Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

from ''norðmann'' (Norseman or Scandinavian), although not a Norwegian possession. In France ''normanni'' or ''northmanni'' referred to people of Norway, Sweden or Denmark. Until around 1800, inhabitants of

Western Norway

Western Norway ( nb, Vestlandet, Vest-Norge; nn, Vest-Noreg) is the region along the Atlantic coast of southern Norway. It consists of the counties Rogaland, Vestland, and Møre og Romsdal. The region has no official or political-administrativ ...

were referred to as ''nordmenn'' (northmen) while inhabitants of

Eastern Norway

Eastern Norway ( nb, Østlandet, nn, Austlandet) is the geographical region of the south-eastern part of Norway. It consists of the counties Vestfold og Telemark, Viken, Oslo and Innlandet.

Eastern Norway is by far the most populous region o ...

were referred to as ''austmenn'' (eastmen).

According to another theory, the first component was a word ''nór'', meaning "narrow" (Old English ''nearu''), referring to the inner-

archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands.

Examples of archipelagos include: the Indonesian Archi ...

sailing route through the land ("narrow way"). The interpretation as "northern", as reflected in the English and Latin forms of the name, would then have been due to later

folk etymology

Folk etymology (also known as popular etymology, analogical reformation, reanalysis, morphological reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation) is a change in a word or phrase resulting from the replacement of an unfamiliar form by a more famili ...

. This latter view originated with philologist Niels Halvorsen Trønnes in 1847; since 2016 it is also advocated by language student and activist Klaus Johan Myrvoll and was adopted by

philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and writing, written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defin ...

professor

Michael Schulte.

The form ''Nore'' is still used in placenames such as the village of

Nore

The Nore is a long bank of sand and silt running along the south-centre of the final narrowing of the Thames Estuary, England. Its south-west is the very narrow Nore Sand. Just short of the Nore's easternmost point where it fades into the cha ...

and lake

Norefjorden

Norefjorden is a lake in the municipality of Nore og Uvdal in Viken (county), Viken county, Norway. Norefjorden is a long, narrow mountain lake which is known for its fishing. Numedalslågen flows into the far north and exits travelling southward ...

in

Buskerud

Buskerud () is a former county and a current electoral district in Norway, bordering Akershus, Oslo, Oppland, Sogn og Fjordane, Hordaland, Telemark and Vestfold. The region extends from the Oslofjord and Drammensfjorden in the southeast to Hardan ...

county, and still has the same meaning.

Among other arguments in favour of the theory, it is pointed out that the word has a long vowel in Skaldic poetry and is not attested with <

ð> in any native Norse texts or inscriptions (the earliest runic attestations have the spellings ''nuruiak'' and ''nuriki''). This resurrected theory has received some pushback by other scholars on various grounds, e. g. the uncontroversial presence of the element ''norðr'' in the ethnonym ''norðrmaðr'' "Norseman, Norwegian person" (modern Norwegian ''nordmann''), and the adjective ''norrǿnn'' "northern, Norse, Norwegian", as well as the very early attestations of the Latin and Anglo-Saxon forms with <

th>.

[Heide, Eldar, 2017:]

Noregr tyder nok vegen mot nord, likevel

".''Namn og nemne'', 2016. Vol 33, 13–37.

In a Latin manuscript of 840, the name ''Northuagia'' is mentioned.

King Alfred's edition of the Orosius World History (dated 880), uses the term ''Norðweg''.

A French chronicle of c. 900 uses the names ''Northwegia'' and ''Norwegia''.

[Sigurðsson and Riisøy: ''Norsk historie 800–1536'', p. 24.] When

Ohthere of Hålogaland

Ohthere of Hålogaland ( no, Ottar fra Hålogaland) was a Viking Age Norwegian seafarer known only from an account of his travels that he gave to King Alfred (r. 871–99) of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Wessex in about 890 AD. His account ...

visited King

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great (alt. Ælfred 848/849 – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who bot ...

in England in the end of the ninth century, the land was called ''Norðwegr'' (lit. "Northway") and ''norðmanna land'' (lit. "Northmen's land").

According to Ohthere, ''Norðmanna'' lived along the Atlantic coast, the Danes around Skagerrak og Kattegat, while the Sámi people (the "Fins") had a nomadic lifestyle in the wide interior. Ohthere told Alfred that he was "the most northern of all Norwegians", presumably at

Senja

or is an island in Troms og Finnmark county, Norway, Europe. With an area of , it is the second largest island in Norway (outside of the Svalbard archipelago). It has a wild, mountainous outer (western) side facing the Atlantic, and a mild ...

island or closer to

Tromsø

Tromsø (, , ; se, Romsa ; fkv, Tromssa; sv, Tromsö) is a List of municipalities of Norway, municipality in Troms og Finnmark county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the Tromsø (city), city of Tromsø.

Tromsø lies ...

. He also said that beyond the wide wilderness in Norway's southern part was the land of the Swedes, "Svealand".

The adjective ''Norwegian'', recorded from c. 1600, is derived from the

latinisation of the name as ''Norwegia''; in the adjective ''Norwegian'', the Old English spelling '-weg' has survived.

After Norway had become Christian, ''Noregr'' and ''Noregi'' had become the most common forms, but during the 15th century, the newer forms ''Noreg(h)'' and ''Norg(h)e'', found in medieval Icelandic manuscripts, took over and have survived until the modern day.

History

Prehistory

The first inhabitants were the

Ahrensburg culture

The Ahrensburg culture or Ahrensburgian (c. 12,900 to 11,700 BP) was a late Upper Paleolithic nomadic hunter culture (or technocomplex) in north-central Europe during the Younger Dryas, the last spell of cold at the end of the Weichsel glaciatio ...

(11th to 10th millennia BC), which was a late

Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

culture during the Younger Dryas, the last period of cold at the end of the

Weichselian glaciation

The Weichselian glaciation was the last glacial period and its associated glaciation in northern parts of Europe. In the Alpine region it corresponds to the Würm glaciation. It was characterized by a large ice sheet (the Fenno-Scandian ice sheet) ...

. The culture is named after the village of

Ahrensburg

Ahrensburg () is a town in the district of Stormarn, Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is located northeast of Hamburg and is part of the Hamburg Metropolitan Region. Its population is around 31,000. ''Schloss Ahrensburg'', the town's symbol, is ...

, northeast of

Hamburg

(male), (female) en, Hamburger(s),

Hamburgian(s)

, timezone1 = Central (CET)

, utc_offset1 = +1

, timezone1_DST = Central (CEST)

, utc_offset1_DST = +2

, postal ...

in the

German state of Schleswig-Holstein, where wooden arrow shafts and clubs have been excavated.

The earliest traces of human occupation in Norway are found along the coast, where the huge ice shelf of the

last ice age first melted between 11,000 and 8,000 BC. The oldest finds are stone tools dating from 9,500 to 6,000 BC, discovered in

Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbouri ...

(

Komsa culture

The Komsa culture (''Komsakulturen'') was a Mesolithic culture of hunter-gatherers that existed from around 10,000 BC in Northern Norway.

The culture is named after Mount Komsa in the community of Alta, Finnmark, where the remains of the culture ...

) in the north and

Rogaland

Rogaland () is a Counties of Norway, county in Western Norway, bordering the North Sea to the west and the counties of Vestland to the north, Vestfold og Telemark to the east and Agder to the east and southeast. In 2020, it had a population of 47 ...

(

Fosna culture) in the southwest. However, theories about two altogether different cultures (the Komsa culture north of the

Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

being one and the Fosna culture from

Trøndelag

Trøndelag (; sma, Trööndelage) is a county in the central part of Norway. It was created in 1687, then named Trondhjem County ( no, Trondhjems Amt); in 1804 the county was split into Nord-Trøndelag and Sør-Trøndelag by the King of Denmar ...

to

Oslofjord

The Oslofjord (, ; en, Oslo Fjord) is an inlet in the south-east of Norway, stretching from an imaginary line between the and lighthouses and down to in the south to Oslo in the north. It is part of the Skagerrak strait, connecting the Nor ...

being the other) were rendered obsolete in the 1970s.

More recent finds along the entire coast revealed to archaeologists that the difference between the two can simply be ascribed to different types of tools and not to different cultures. Coastal fauna provided a means of livelihood for fishermen and hunters, who may have made their way along the southern coast about 10,000 BC when the interior was still covered with ice. It is now thought that these so-called "Arctic" peoples came from the south and followed the coast northward considerably later.

In the southern part of the country are dwelling sites dating from about 5,000 BC. Finds from these sites give a clearer idea of the life of the hunting and fishing peoples. The implements vary in shape and mostly are made of different kinds of stone; those of later periods are more skilfully made.

Rock carvings

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

(i.e. petroglyphs) have been found, usually near hunting and fishing grounds. They represent game such as deer,

reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subspe ...

,

elk

The elk (''Cervus canadensis''), also known as the wapiti, is one of the largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. The common ...

, bears, birds,

seals

Seals may refer to:

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to impress an emblem, used as a means of a ...

, whales, and fish (especially

salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several list of commercially important fish species, commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family (biology), family Salmonidae, which are native to tributary, tributaries of the ...

and

halibut

Halibut is the common name for three flatfish in the genera '' Hippoglossus'' and ''Reinhardtius'' from the family of right-eye flounders and, in some regions, and less commonly, other species of large flatfish.

The word is derived from ''h ...

), all of which were vital to the way of life of the coastal peoples. The

rock carvings at Alta

The Rock art of Alta (''Helleristningene i Alta'') are located in and around the municipality of Alta, Norway, Alta in the county of Finnmark in northern Norway. Since the first carvings were discovered in 1973, more than 6000 carvings have been ...

in Finnmark, the largest in Scandinavia, were made at sea level from 4,200 to 500 BC and mark the progression of the land as the sea rose after the last ice age ended.

Bronze Age

Between 3000 and 2500 BC, new settlers (

Corded Ware culture

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between ca. 3000 BC – 2350 BC, thus from the late Neolithic, through the Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age. Corded Ware culture encompassed a va ...

) arrived in

eastern Norway

Eastern Norway ( nb, Østlandet, nn, Austlandet) is the geographical region of the south-eastern part of Norway. It consists of the counties Vestfold og Telemark, Viken, Oslo and Innlandet.

Eastern Norway is by far the most populous region o ...

. They were

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Dutch ...

farmers

A farmer is a person engaged in agriculture, raising living organisms for food or raw materials. The term usually applies to people who do some combination of raising field crops, orchards, vineyards, poultry, or other livestock. A farmer mi ...

who grew grain and kept cows and sheep. The hunting-fishing population of the west coast was also gradually replaced by farmers, though hunting and fishing remained useful secondary means of livelihood.

From about 1500 BC,

bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids such ...

was gradually introduced, but the use of stone implements continued; Norway had few riches to barter for bronze goods, and the few finds consist mostly of elaborate weapons and brooches that only chieftains could afford. Huge burial cairns built close to the sea as far north as

Harstad

( se, Hárstták) is the second-most populated municipality in Troms og Finnmark county, Norway. It is mostly located on the large island of Hinnøya. The municipal center is the Harstad (town), town of Harstad, the most populous town in Centra ...

and also inland in the south are characteristic of this period. The motifs of the rock carvings differ slightly from those typical of the

Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with t ...

. Representations of the Sun, animals, trees, weapons, ships, and people are all strongly stylised.

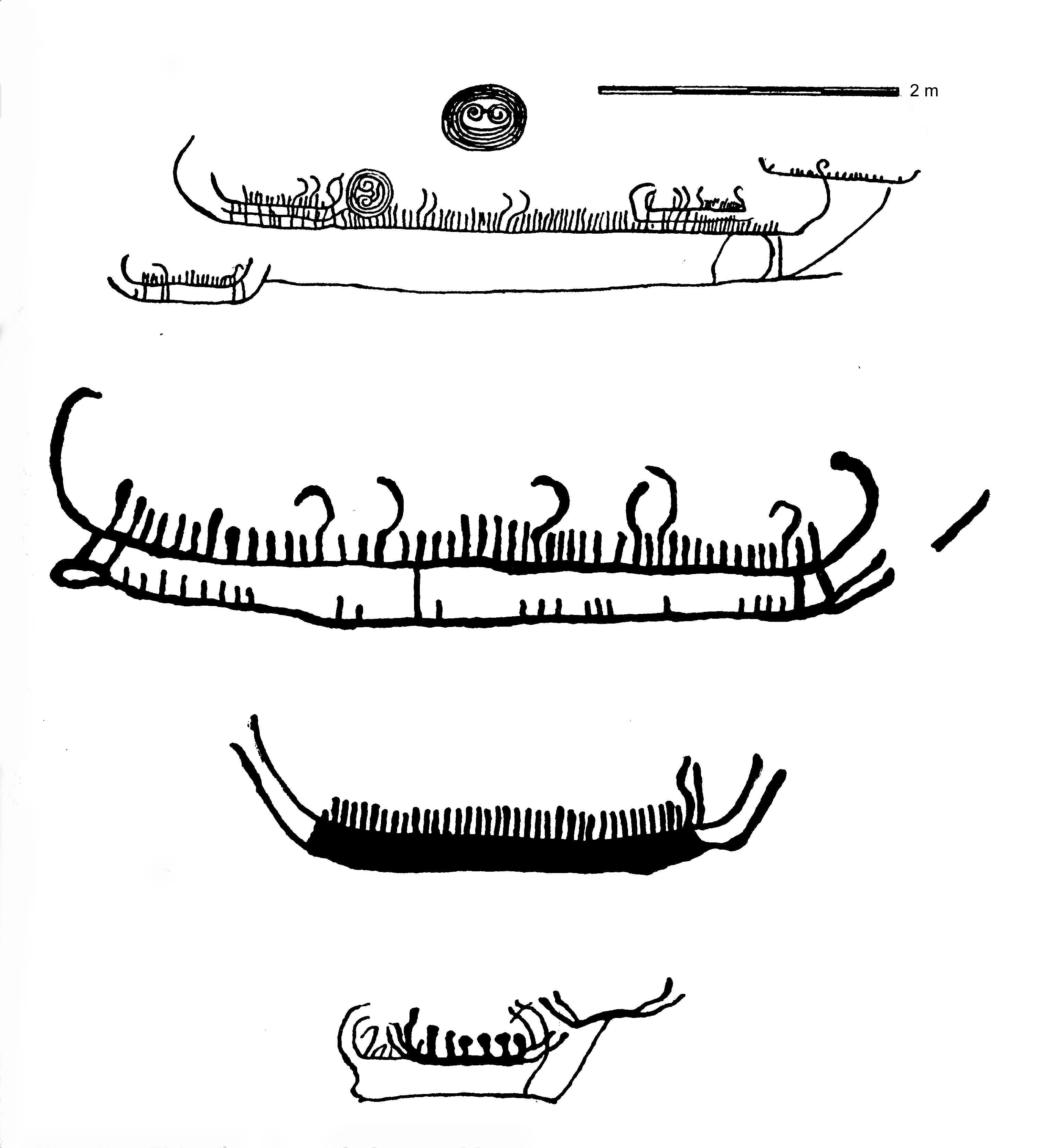

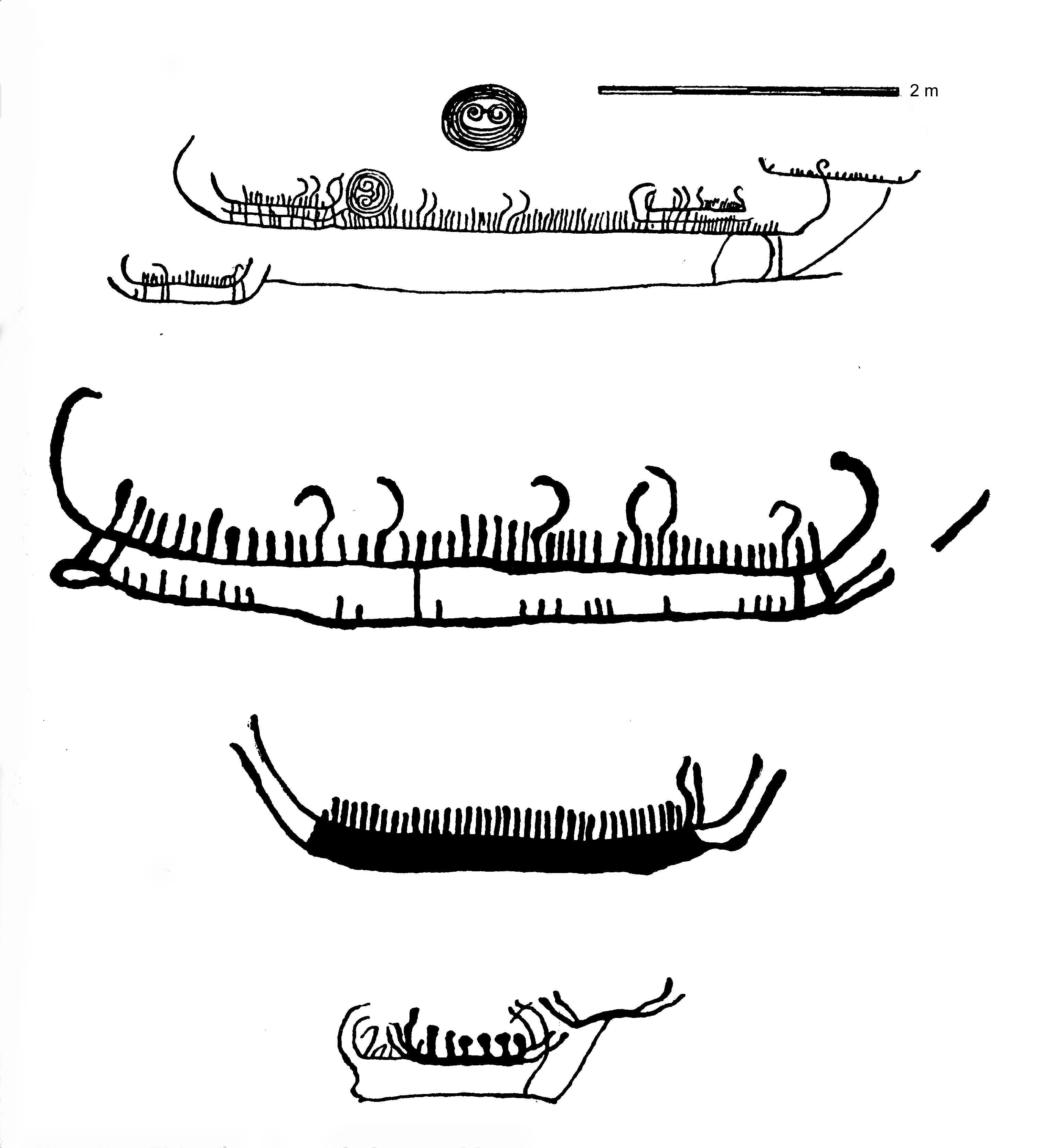

Thousands of rock carvings from this period depict ships, and the large stone burial monuments known as

stone ship

The stone ship or ship setting was an early burial custom in Scandinavia, Northern Germany, and the Baltic states. The grave or cremation burial was surrounded by slabs or stones in the shape of a boat or ship. The ships vary in size and were e ...

s, suggest that ships and seafaring played an important role in the culture at large. The depicted ships most likely represent sewn plank built canoes used for warfare, fishing and trade. These ship types may have their origin as far back as the neolithic period and they continue into the Pre-Roman Iron Age, as exemplified by the

Hjortspring boat

The Hjortspring boat ( da, Hjortspringbåden) is a vessel designed as a large canoe, from the Scandinavian Pre-Roman Iron Age. It was built circa 400–300 BC. The hull and remains were rediscovered and excavated in 1921–1922 from the bog of ''H ...

.

Iron Age

Little has been found dating from the early

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

(the last 500 years BC). The dead were cremated, and their graves contain few burial goods. During the first four centuries AD, the people of Norway were in contact with Roman-occupied

Gaul

Gaul ( la, Gallia) was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans. It was inhabited by Celtic and Aquitani tribes, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, most of Switzerland, parts of Northern Italy (only during ...

. About 70 Roman bronze cauldrons, often used as burial urns, have been found. Contact with the civilised countries farther south brought a knowledge of

runes

Runes are the letter (alphabet), letters in a set of related alphabets known as runic alphabets native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were used to write various Germanic languages (with some exceptions) before they adopted the Latin alphabet, a ...

; the oldest known Norwegian runic inscription dates from the third century. At this time, the amount of settled area in the country increased, a development that can be traced by coordinated studies of

topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

,

archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

, and place-names. The oldest root names, such as nes, vik, and bø ("cape," "bay," and "farm"), are of great antiquity, dating perhaps from the Bronze Age, whereas the earliest of the groups of compound names with the suffixes vin ("meadow") or heim ("settlement"), as in Bjǫrgvin (Bergen) or Sǿheim (Seim), usually date from the first century AD.

Archaeologists first made the decision to divide the Iron Age of Northern Europe into distinct pre-Roman and

Roman Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, northern Germany, Poland and the Netherlands.

The region ...

s after Emil Vedel unearthed a number of Iron Age artefacts in 1866 on the island of

Bornholm

Bornholm () is a Danish island in the Baltic Sea, to the east of the rest of Denmark, south of Sweden, northeast of Germany and north of Poland.

Strategically located, Bornholm has been fought over for centuries. It has usually been ruled by ...

. They did not exhibit the same permeating Roman influence seen in most other artefacts from the early centuries AD, indicating that parts of northern Europe had not yet come into contact with the Romans at the beginning of the

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

.

Migration period

The destruction of the

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

by the

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

in the fifth century is characterised by rich finds, including

tribal chief

A tribal chief or chieftain is the leader of a tribal society or chiefdom.

Tribe

The concept of tribe is a broadly applied concept, based on tribal concepts of societies of western Afroeurasia.

Tribal societies are sometimes categorized as ...

s' graves containing magnificent weapons and gold objects. Hill forts were built on precipitous rocks for defence. Excavation has revealed stone foundations of farmhouses long—one even long—the roofs of which were supported on wooden posts. These houses were family homesteads where several generations lived together, with people and cattle under one roof.

These states were based on either clans or tribes (e.g., the Horder of

Hordaland

Hordaland () was a county in Norway, bordering Sogn og Fjordane, Buskerud, Telemark, and Rogaland counties. Hordaland was the third largest county, after Akershus and Oslo, by population. The county government was the Hordaland County Municipal ...

in

western Norway

Western Norway ( nb, Vestlandet, Vest-Norge; nn, Vest-Noreg) is the region along the Atlantic coast of southern Norway. It consists of the counties Rogaland, Vestland, and Møre og Romsdal. The region has no official or political-administrativ ...

). By the ninth century, each of these small states had

''things'' (local or regional assemblies) for negotiating and settling disputes. The ''thing'' meeting places, each eventually with a

hörgr

A hörgr (Old Norse, plural ''hörgar'') or hearg (Old English) was a type of altar or cult site, possibly consisting of a heap of stones, used in Norse religion, as opposed to a roofed hall used as a ''hof'' (temple).

The Old Norse term is attes ...

(open-air sanctuary) or a

heathen hof

A heathen hof or Germanic pagan temple was a temple building of Germanic religion; a few have also been built for use in modern heathenry. The term ''hof'' is taken from Old Norse.

Background

Etymologically, the Old Norse word ''hof'' is the s ...

(temple; literally "hill"), were usually situated on the oldest and best farms, which belonged to the chieftains and wealthiest farmers. The regional ''things'' united to form even larger units: assemblies of deputy yeomen from several regions. In this way, the ''lagting'' (assemblies for negotiations and lawmaking) developed. The

Gulating

Gulating ( non, Gulaþing) was one of the first Norwegian legislative assemblies, or '' things,'' and also the name of a present-day law court of western Norway. The practice of periodic regional assemblies predates recorded history, and was fi ...

had its meeting place by

Sognefjord

The Sognefjord or Sognefjorden (, en, Sogn Fjord), nicknamed the King of the Fjords ( no, Fjordenes konge), is the largest and deepest fjord in Norway. Located in Vestland county in Western Norway, it stretches inland from the ocean to the smal ...

and may have been the centre of an aristocratic confederation along the western fjords and islands called the Gulatingslag. The Frostating was the assembly for the leaders in the

Trondheimsfjord

The Trondheim Fjord or Trondheimsfjorden (), an inlet of the Norwegian Sea, is Norway's third-longest fjord at long. It is located in the west-central part of the country in Trøndelag county, and it stretches from the municipality of Ørland in ...

area; the

Earls of Lade

The Earls of Lade ( no, ladejarler) were a dynasty of Norsemen, Norse ''jarl (title), jarls'' from Lade, Trondheim, Lade (Old Norse: ''Hlaðir''), who ruled what is now Trøndelag and Hålogaland from the 9th century to the 11th century.

The s ...

, near

Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

, seem to have enlarged the Frostatingslag by adding the coastland from

Romsdalsfjord

Romsdalsfjord or Romsdal Fjord ( no, Romsdalsfjorden) is the ninth-longest fjord in Norway. It is long and located in the Romsdal district of Møre og Romsdal county. It flows through the municipalities of Molde, Ålesund, Vestnes, and Rauma. ...

to

Lofoten

Lofoten () is an archipelago and a traditional district in the county of Nordland, Norway. Lofoten has distinctive scenery with dramatic mountains and peaks, open sea and sheltered bays, beaches and untouched lands. There are two towns, Svolvær ...

.

Viking Age

From the eighth to the tenth century, the wider Scandinavian region was the source of

Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

s. The looting of the monastery at

Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important ...

in Northeast England in 793 by

Norse people

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic peoples, North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic languages, North Germanic br ...

has long been regarded as the event which marked the beginning of the

Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period and the Ger ...

. This age was characterised by expansion and emigration by Viking

seafarer

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship.

The profession of the s ...

s. They

colonise

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

d, raided, and traded in all parts of Europe. Norwegian Viking explorers discovered

Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its s ...

by accident in the ninth century when heading for the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

, and eventually came across

Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland ( non, Vínland ᚠᛁᚾᛚᛅᚾᛏ) was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John ...

, known today as

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

, in Canada. The Vikings from Norway were most active in the northern and western

British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

and eastern

North America isles.

According to tradition,

Harald Fairhair

Harald Fairhair no, Harald hårfagre Modern Icelandic: ( – ) was a Norwegian king. According to traditions current in Norway and Iceland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, he reigned from 872 to 930 and was the first King of Nor ...

unified them into one in 872 after the

Battle of Hafrsfjord

The Battle of Hafrsfjord ( no, Slaget i Hafrsfjord) was a great naval battle fought in Hafrsfjord sometime between 872 and 900 that resulted in the unification of Norway, later known as the Kingdom of Norway. After the battle, the victorious Vikin ...

in

Stavanger

Stavanger (, , American English, US usually , ) is a city and municipalities of Norway, municipality in Norway. It is the fourth largest city and third largest metropolitan area in Norway (through conurbation with neighboring Sandnes) and the a ...

, thus becoming the first king of a united Norway. Harald's realm was mainly a South Norwegian coastal state. Fairhair ruled with a strong hand and according to the sagas, many Norwegians left the country to live in Iceland, the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic island group and an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotland, and about halfway bet ...

,

Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is t ...

, and parts of

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and Ireland. The modern-day Irish cities of

Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

,

Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

and

Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

were founded by Norwegian settlers.

Norse traditions were replaced slowly by

Christian ones in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. One of the most important sources for the history of the 11th century Vikings is the treaty between the Icelanders and Olaf Haraldsson, king of Norway circa 1015 to 1028. This is largely attributed to the missionary kings

Olav Tryggvasson and

St. Olav.

Haakon the Good

Haakon Haraldsson (c. 920–961), also Haakon the Good (Old Norse: ''Hákon góði'', Norwegian: ''Håkon den gode'') and Haakon Adalsteinfostre (Old Norse: ''Hákon Aðalsteinsfóstri'', Norwegian: ''Håkon Adalsteinsfostre''), was the king of ...

was Norway's first Christian king, in the mid-10th century, though his attempt to introduce the religion was rejected. Born sometime in between 963 and 969, Olav Tryggvasson set off raiding in England with 390 ships. He attacked London during this raiding. Arriving back in Norway in 995, Olav landed in

Moster

Moster is a former municipality in the old Hordaland county, Norway. The municipality existed from 1916 until 1963, when it was merged into the new, larger municipality of Bømlo. The administrative centre of the municipality was the village o ...

. There he built a church which became the first

Christian church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym fo ...

ever built in Norway. From Moster, Olav sailed north to

Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Tråante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, and ...

where he was proclaimed King of Norway by the Eyrathing in 995.

Feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

never really developed in Norway or Sweden, as it did in the rest of Europe. However, the administration of government took on a very conservative feudal character. The

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

forced the royalty to cede to them greater and greater concessions over foreign trade and the economy. The League had this hold over the royalty because of the loans the Hansa had made to the royalty and the large debt the kings were carrying. The League's monopolistic control over the economy of Norway put pressure on all classes, especially the peasantry, to the degree that no real

burgher

Burgher may refer to:

* Burgher (social class), a medieval, early modern European title of a citizen of a town, and a social class from which city officials could be drawn

** Burgess (title), a resident of a burgh in northern Britain

** Grand Bu ...

class existed in Norway.

Civil war and peak of power

From the 1040s to 1130, the country was at peace. In 1130, the

civil war era

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

broke out on the basis of

unclear succession laws, which allowed all the king's sons to rule jointly. For periods there could be peace, before a lesser son allied himself with a chieftain and started a new conflict. The

Archdiocese of Nidaros

The Archdiocese of Nidaros (or Niðaróss) was the metropolitan see covering Norway in the later Middle Ages. The see was the Nidaros Cathedral, in the city of Nidaros (now Trondheim). The archdiocese existed from the middle of the twelfth cent ...

was created in 1152 and attempted to control the appointment of kings. The church inevitably had to take sides in the conflicts, with the civil wars also becoming an issue regarding the church's influence of the king. The wars ended in 1217 with the appointment of

Håkon Håkonsson

Haakon IV Haakonsson ( – 16 December 1263; Old Norse: ''Hákon Hákonarson'' ; Norwegian: ''Håkon Håkonsson''), sometimes called Haakon the Old in contrast to his namesake son, was King of Norway from 1217 to 1263. His reign lasted for 46 y ...

, who introduced clear law of succession.

From 1000 to 1300, the population increased from 150,000 to 400,000, resulting both in more land being cleared and the subdivision of farms. While in the Viking Age all farmers owned their own land, by 1300, seventy percent of the land was owned by the king, the church, or the aristocracy. This was a gradual process which took place because of farmers borrowing money in poor times and not being able to repay. However, tenants always remained free men and the large distances and often scattered ownership meant that they enjoyed much more freedom than continental serfs. In the 13th century, about twenty percent of a farmer's yield went to the king, church and landowners.

The 14th century is described as Norway's

Golden Age

The term Golden Age comes from Greek mythology, particularly the ''Works and Days'' of Hesiod, and is part of the description of temporal decline of the state of peoples through five Ages of Man, Ages, Gold being the first and the one during ...

, with peace and increase in trade, especially with the British Islands, although Germany became increasingly important towards the end of the century. Throughout the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended ...

, the king established Norway as a sovereign state with a central administration and local representatives.

In 1349, the

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

spread to Norway and had within a year killed a third of the population. Later plagues reduced the population to half the starting point by 1400. Many communities were entirely wiped out, resulting in an abundance of land, allowing farmers to switch to more

animal husbandry

Animal husbandry is the branch of agriculture concerned with animals that are raised for meat, fibre, milk, or other products. It includes day-to-day care, selective breeding, and the raising of livestock. Husbandry has a long history, starti ...

. The reduction in taxes weakened the king's position, and many aristocrats lost the basis for their surplus, reducing some to mere farmers. High

tithe

A tithe (; from Old English: ''teogoþa'' "tenth") is a one-tenth part of something, paid as a contribution to a religious organization or compulsory tax to government. Today, tithes are normally voluntary and paid in cash or cheques or more r ...

s to church made it increasingly powerful and the archbishop became a member of the

Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

.

[Stenersen: 45]

The

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

took control over Norwegian trade during the 14th century and established a trading centre in

Bergen

Bergen (), historically Bjørgvin, is a city and municipality in Vestland county on the west coast of Norway. , its population is roughly 285,900. Bergen is the second-largest city in Norway. The municipality covers and is on the peninsula of ...

. In 1380,

Olaf Haakonsson inherited both the Norwegian and Danish thrones, creating a union between the two countries.

In 1397, under

Margaret I Margaret I may refer to:

* Margaret I, Countess of Flanders (died 1194)

* Margaret I of Scotland (1283–1290), usually known as the Maid of Norway

* Margaret I, Countess of Holland (1311–1356), Countess of Hainaut and Countess of Holland

* Ma ...

, the

Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union (Danish language, Danish, Norwegian language, Norwegian, and sv, Kalmarunionen; fi, Kalmarin unioni; la, Unio Calmariensis) was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden, that from 1397 to 1523 joined under ...

was created between the three Scandinavian countries. She waged war against the Germans, resulting in a trade blockade and higher taxation on Norwegian goods, which resulted in

a rebellion. However, the Norwegian Council of State was too weak to pull out of the union.

[Stenersen: 46]

Margaret pursued a centralising policy which inevitably favoured Denmark, because it had a greater population than Norway and Sweden combined. Margaret also granted trade privileges to the Hanseatic merchants of

Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the stat ...

in Bergen in return for recognition of her right to rule, and these hurt the Norwegian economy. The Hanseatic merchants formed a state within a state in Bergen for generations. Even worse were the pirates, the "

Victual Brothers

, native_name_lang =

, named_after = french: vitailleurs (provisioners, Hundred Years' War)

, image = Vitalienbrueder, Wandmalerei in d, Kirche zu Bunge auf Gotland, gemalt ca. 1405.JPG

, image_size = 250px ...

", who launched three devastating raids on the port (the last in 1427).

Norway slipped ever more to the background under the

Oldenburg dynasty (established 1448). There was one revolt under

Knut Alvsson

Knut Alvsson (1455 – 18 August 1502) was a Norwegian nobleman and landowner. He was the country's foremost Norwegian-born noble in his time and served as fief-holder in southern-central Norway.

He was heir of the Sudreim claim to the Norw ...

in 1502. Norwegians had some affection for

King Christian II, who resided in the country for several years. Norway took no part in the events which led to Swedish independence from Denmark in the 1520s.

Kalmar Union

Upon the death of

Haakon V

Haakon V Magnusson (10 April 1270 – 8 May 1319) ( non, Hákon Magnússon; no, Håkon Magnusson, label=Modern Norwegian) was king of Norway from 1299 until 1319.

Biography

Haakon was the younger surviving son of Magnus the Lawmender, Kin ...

(King of Norway) in 1319,

Magnus Erikson, at just three years old, inherited the throne as King Magnus VII of Norway. At the same time, a movement to make Magnus King of Sweden proved successful, and both the kings of Sweden and of Denmark were elected to the throne by their respective nobles, Thus, with his election to the throne of Sweden, both Sweden and Norway were united under King Magnus VII.

[ Larsen, p. 192.]

In 1349, the

Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

radically altered Norway, killing between 50% and 60% of its population and leaving it in a period of social and economic decline.

The plague left Norway very poor. Although the death rate was comparable with the rest of Europe, economic recovery took much longer because of the small, scattered population.

Even before the plague, the population was only about 500,000.

[ Larsen, pp. 202–03.] After the plague, many farms lay idle while the population slowly increased.

However, the few surviving farms' tenants found their bargaining positions with their landlords greatly strengthened.

[

] King Magnus VII ruled Norway until 1350, when his son, Haakon, was placed on the throne as

King Magnus VII ruled Norway until 1350, when his son, Haakon, was placed on the throne as Haakon VI

Haakon VI of Norway ( no, Håkon, sv, Håkan; August 1340 – 11 September 1380), also known as ''Håkan Magnusson'', was King of Norway from 1343 until his death and King of Sweden between 1362 and 1364. He is sometimes known as ''Haakon Magnus ...

.[ Larsen, p. 195] In 1363, Haakon VI married Margaret

Margaret is a female first name, derived via French () and Latin () from grc, μαργαρίτης () meaning "pearl". The Greek is borrowed from Persian.

Margaret has been an English name since the 11th century, and remained popular througho ...

, the daughter of King Valdemar IV of Denmark

Valdemar IV Atterdag (the epithet meaning "Return of the Day"), or Waldemar (132024 October 1375) was King of Denmark from 1340 to 1375. He is mostly known for his reunion of Denmark after the bankruptcy and mortgaging of the country to finance ...

.personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

.[ Larsen, p. 197] Olaf's mother and Haakon's widow, Queen Margaret, managed the foreign affairs of Denmark and Norway during the minority of Olaf IV.[ Queen Margaret knew that her power would be more secure if she were able to find a king to rule in her place. She settled on ]Eric of Pomerania

Eric of Pomerania (1381 or 1382 – 24 September 1459) was the ruler of the Kalmar Union from 1396 until 1439, succeeding his grandaunt, Queen Margaret I. He is known as Eric III as King of Norway (1389–1442), Eric VII as King of Denmark (1396 ...

, grandson of her sister. Thus at an all-Scandinavian meeting held at Kalmar, Erik of Pomerania was crowned king of all three Scandinavian countries. Thus, royal politics resulted in personal unions between the Nordic countries

The Nordic countries (also known as the Nordics or ''Norden''; literal translation, lit. 'the North') are a geographical and cultural region in Northern Europe and the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It includes the sovereign states of Denmar ...

, eventually bringing the thrones of Norway, Denmark, and Sweden under the control of Queen Margaret when the country entered into the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union (Danish language, Danish, Norwegian language, Norwegian, and sv, Kalmarunionen; fi, Kalmarin unioni; la, Unio Calmariensis) was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden, that from 1397 to 1523 joined under ...

.

Union with Denmark

After Sweden broke out of the Kalmar Union

The Kalmar Union (Danish language, Danish, Norwegian language, Norwegian, and sv, Kalmarunionen; fi, Kalmarin unioni; la, Unio Calmariensis) was a personal union in Scandinavia, agreed at Kalmar in Sweden, that from 1397 to 1523 joined under ...

in 1521, Norway tried to follow suit, but the subsequent rebellion was defeated, and Norway remained in a union with Denmark until 1814, a total of 434 years. During the national romanticism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

of the 19th century, this period was by some referred to as the "400-Year Night", since all of the kingdom's royal, intellectual, and administrative power was centred in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

in Denmark. In fact, it was a period of great prosperity and progress for Norway, especially in terms of shipping and foreign trade, and it also secured the country's revival from the demographic catastrophe it suffered in the Black Death

The Black Death (also known as the Pestilence, the Great Mortality or the Plague) was a bubonic plague pandemic occurring in Western Eurasia and North Africa from 1346 to 1353. It is the most fatal pandemic recorded in human history, causi ...

. Based on the respective natural resources, Denmark–Norway was in fact a very good match since Denmark supported Norway's needs for grain and food supplies, and Norway supplied Denmark with timber, metal, and fish.

With the introduction of Protestantism in 1536, the archbishopric in Trondheim was dissolved, and Norway lost its independence, and effectually became a colony of Denmark. The Church's incomes and possessions were instead redirected to the court in Copenhagen. Norway lost the steady stream of pilgrims to the relics of St. Olav at the

With the introduction of Protestantism in 1536, the archbishopric in Trondheim was dissolved, and Norway lost its independence, and effectually became a colony of Denmark. The Church's incomes and possessions were instead redirected to the court in Copenhagen. Norway lost the steady stream of pilgrims to the relics of St. Olav at the Nidaros

Nidaros, Niðarós or Niðaróss () was the medieval name of Trondheim when it was the capital of Norway's first Christian kings. It was named for its position at the mouth (Old Norse: ''óss'') of the River Nid (the present-day Nidelva).

Althou ...

shrine, and with them, much of the contact with cultural and economic life in the rest of Europe.

Eventually restored as a kingdom (albeit in legislative union with Denmark) in 1661, Norway saw its land area decrease in the 17th century with the loss of the provinces Båhuslen, Jemtland, and Herjedalen to Sweden, as the result of a number of disastrous wars with Sweden. In the north, however, its territory was increased by the acquisition of the northern provinces of Troms

Troms (; se, Romsa; fkv, Tromssa; fi, Tromssa) is a former county in northern Norway. On 1 January 2020 it was merged with the neighboring Finnmark county to create the new Troms og Finnmark county. This merger is expected to be reversed by t ...

and Finnmark

Finnmark (; se, Finnmárku ; fkv, Finmarku; fi, Ruija ; russian: Финнмарк) was a county in the northern part of Norway, and it is scheduled to become a county again in 2024.

On 1 January 2020, Finnmark was merged with the neighbouri ...

, at the expense of Sweden and Russia.