North Norfolk Coast Site Of Special Scientific Interest on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Interest (

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the

An "eye" is an area of higher ground in the marshes, dry enough to support buildings. Cley Eye had been farmed since the earliest human habitation, and was 28 ha (70 acres) in extent in 1651, but is much reduced by

An "eye" is an area of higher ground in the marshes, dry enough to support buildings. Cley Eye had been farmed since the earliest human habitation, and was 28 ha (70 acres) in extent in 1651, but is much reduced by

Artillery may have been installed at Gun Hill on the coast near Burnham Overy during the

Artillery may have been installed at Gun Hill on the coast near Burnham Overy during the

The first step towards the protection of this coast by a national conservation body was the purchase of Blakeney Point from the Calthorpe family by banker

The first step towards the protection of this coast by a national conservation body was the purchase of Blakeney Point from the Calthorpe family by banker

The SSSI is designated as a Special Protection Area for birds for its variety of coastal habitats. The large breeding colonies of

The SSSI is designated as a Special Protection Area for birds for its variety of coastal habitats. The large breeding colonies of

Water voles are a highly threatened species in the UK, with a 70–90% decline in numbers mainly due to predation by the introduced

Water voles are a highly threatened species in the UK, with a 70–90% decline in numbers mainly due to predation by the introduced

On exposed parts of the coast, the muds and sands are scoured by the tides, and have no vegetation except possibly algae or eelgrass. Where the shoreline is more protected, internationally important salt marshes can form, with several uncommon species. The salt marshes contains glassworts and common cord grass in the most exposed regions, with a succession of plants following on as the marsh becomes more established: first

On exposed parts of the coast, the muds and sands are scoured by the tides, and have no vegetation except possibly algae or eelgrass. Where the shoreline is more protected, internationally important salt marshes can form, with several uncommon species. The salt marshes contains glassworts and common cord grass in the most exposed regions, with a succession of plants following on as the marsh becomes more established: first

Scolt Head Island is accessed by a ferry from

Scolt Head Island is accessed by a ferry from

A 2005 survey at six North Norfolk coastal sites (Snettisham, Titchwell, Holkham, Morston Quay, Blakeney and Cley) found that 39 per cent of visitors gave

A 2005 survey at six North Norfolk coastal sites (Snettisham, Titchwell, Holkham, Morston Quay, Blakeney and Cley) found that 39 per cent of visitors gave In Focus

In Focus. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

The large number of visitors sometimes has negative effects. Wildlife may be disturbed, a frequent difficulty for species that breed in exposed areas such as ringed plovers, little terns and common seals, but also wintering geese. Plants can be trampled, which is a particular problem in sensitive habitats such as sand dunes and vegetated shingle.Liley (2008) pp. 10–14. Damage is reduced by measures such as wardening breeding colonies, using fences, boardwalks and signs to control access, and appropriate positioning of car parks.Liley (2008) pp. 19–20. The Norfolk Coast Partnership, a grouping of conservation and environmental bodies, divide the coast into zones for tourism development purposes. Holme dunes, Holkham dunes and Blakeney Point, sensitive habitats suffering from visitor pressure, were designated as red-zone areas with no development or parking improvements to be recommended. "Orange" locations had fragile habitats, but were under less tourism pressure, or, as with the large nature reserves, were equipped to cope with many visitors. The most robust sites, mainly outside the SSSI, were placed in the green zone.Scott Wilson Ltd (2006) pp. 5–6.

One of the most vulnerable stretches is that between Blakeney Point and Weybourne, which included the Cley and Salthouse Marsh reserves.East Anglia Coastal Group (2010) p. 27. The coast here is protected by a shingle ridge, but the sea attacks the ridge and spit through tidal and storm action, with a single storm sometimes moving a "spectacular" amount of shingle. The Blakeney Point spit has sometimes been breached, becoming an island for a time, and this may happen again.May, V J (2003)

One of the most vulnerable stretches is that between Blakeney Point and Weybourne, which included the Cley and Salthouse Marsh reserves.East Anglia Coastal Group (2010) p. 27. The coast here is protected by a shingle ridge, but the sea attacks the ridge and spit through tidal and storm action, with a single storm sometimes moving a "spectacular" amount of shingle. The Blakeney Point spit has sometimes been breached, becoming an island for a time, and this may happen again.May, V J (2003)

North Norfolk Coast

in May (2003) pp. 1–19. The northernmost part of nearby Blakeney was lost to the sea in the early Middle Ages, probably due to a storm.Muir (2008) p. 103. The spit is moving towards the mainland at about 1 m (1 yd) per year,Gray (2004) pp. 363–365. and for the last two hundred years maps have been accurate enough for the encroachment of the sea to be quantified. Blakeney Chapel was 400 m (440 yd) from the sea in 1817, but this had reduced to 195 m (215 yd) by the end of the 20th century. The landward movement of the shingle means that the channel of the River Glaven becomes blocked increasingly often, leading to flooding of the reserve and Cley village. The

SSSI

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle of ...

) is an area of European importance for wildlife in Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

, England. It comprises 7,700 ha (19,027 acres) of the county's north coast from just west of Holme-next-the-Sea

Holme-next-the-Sea is a small village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is situated on the north Norfolk coast some 5 km north-east of the seaside resort of Hunstanton, 30 km north of the town of King's Lynn a ...

to Kelling

Kelling (also known as ''Low Kelling'' and as ''Lower Kelling'') is a village and a civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is west of Cromer, north of Norwich, and northeast of London. The village straddles the A149 Coast ...

, and is additionally protected through Natura 2000

Natura 2000 is a network of nature protection areas in the territory of the European Union. It is made up of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas designated under the Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive, respectively ...

, Special Protection Area

A Special Protection Area (SPA) is a designation under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds. Under the Directive, Member States of the European Union (EU) have a duty to safeguard the habitats of migratory birds and cert ...

(SPA) listings; it is also part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). The North Norfolk Coast is also designated as a wetland of international importance on the Ramsar list and most of it is a Biosphere Reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or o ...

.

Habitats within the SSSI include reed bed

A reedbed or reed bed is a natural habitat found in floodplains, waterlogged depressions and

estuaries. Reedbeds are part of a succession from young reeds colonising open water or wet ground through a gradation of increasingly dry ground. As ...

s, salt marsh

A salt marsh or saltmarsh, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. It is dominated ...

es, freshwater lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') a ...

s and sand or shingle beach

A shingle beach (also referred to as rocky beach or pebble beach) is a beach which is armoured with pebbles or small- to medium-sized cobbles (as opposed to fine sand). Typically, the stone composition may grade from characteristic sizes ranging ...

es. The wetlands are important for wildlife, including some scarce breeding birds such as pied avocet

The pied avocet (''Recurvirostra avosetta'') is a large black and white wader in the avocet and stilt family, Recurvirostridae. They breed in temperate Europe and across the Palearctic to Central Asia then on to the Russian Far East. It is a mig ...

s, western marsh harrier

The western marsh harrier (''Circus aeruginosus'') is a large harrier, a bird of prey from temperate and subtropical western Eurasia and adjacent Africa. It is also known as the Eurasian marsh harrier. Formerly, a number of relatives were includ ...

s, Eurasian bittern

The Eurasian bittern or great bittern (''Botaurus stellaris'') is a wading bird in the bittern subfamily (Botaurinae) of the heron family Ardeidae. There are two subspecies, the northern race (''B. s. stellaris'') breeding in parts of Europe and ...

s and bearded reedling

The bearded reedling (''Panurus biarmicus'') is a small, sexual dimorphism, sexually dimorphic reed bed, reed-bed passerine bird. It is frequently known as the bearded tit, due to some similarities to the long-tailed tit, or the bearded parrotbil ...

s. The location also attracts migrating birds

Bird migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a flyway, between breeding and wintering grounds. Many species of bird migrate. Migration carries high costs in predation and mortality, including from hunting by ...

including vagrant

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, temporar ...

rarities. Ducks and geese winter along this coast in considerable numbers, and several nature reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or ...

s provide suitable conditions for water voles, natterjack toad

The natterjack toad (''Epidalea calamita'') is a toad native to sandy and heathland areas of Europe. Adults are 60–70 mm in length, and are distinguished from common toads by a yellow line down the middle of the back and parallel paratoid g ...

s and several scarce plants and invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s.

The area is archaeologically

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

significant, with artefacts dating back to the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

. The mound of an Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

fort is visible at Holkham

Holkham is a small village and civil parish in north Norfolk, England, which includes a stately home and estate, Holkham Hall, and a beach, Holkham Gap, at the centre of Holkham National Nature Reserve.

Geography

The parish has an area of and ...

, and the site of a 23 ha (57 acres) Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

naval port with a fort built on the castrum

In the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a po ...

pattern is just outside Brancaster

Brancaster is a village and civil parish on the north coast of the English county of Norfolk. The civil parish of Brancaster comprises Brancaster itself, together with Brancaster Staithe and Burnham Deepdale. The three villages form a more or l ...

. The site of the medieval "chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common ty ...

" (probably a domestic dwelling) at Blakeney is no longer accessible. Remains of military use from both world war

A world war is an international conflict which involves all or most of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World WarI (1914 ...

s include an armoured fighting vehicle

An armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) is an armed combat vehicle protected by armour, generally combining operational mobility with offensive and defensive capabilities. AFVs can be wheeled or tracked. Examples of AFVs are tanks, armoured car ...

gunnery range, a hospital and bombing ranges, as well as passive defences such as pillboxes, barbed wire and tank traps.

The SSSI is economically important to the area because of the tourists it attracts for birdwatching

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device like binoculars or a telescope, b ...

and other outdoor activities, although sensitive wildlife sites are managed to avoid damage from the large numbers of visitors. Another threat is the encroachment of the sea on this soft coast. The Environment Agency

The Environment Agency (EA) is a non-departmental public body, established in 1996 and sponsored by the United Kingdom government's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, with responsibilities relating to the protection and enha ...

considers that managed retreat

Managed retreat involves the purposeful, coordinated movement of people and buildings away from risks. This may involve the movement of a person, infrastructure (e.g., building or road), or community. It can occur in response to a variety of hazar ...

is likely to be the long-term solution, and is working with the Norfolk Wildlife Trust

The Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT) is one of 46 wildlife trusts covering Great Britain, Northern Ireland, Isle of Man and Alderney. Founded in 1926, it is the oldest of all the trusts. It has over 35,500 members and eight local groups and it mana ...

to create new reserves inland to compensate for the loss of scarce habitats at the coast.

Description

The SSSI is a long, narrow strip of coast that starts at the eastern boundary ofThe Wash

The Wash is a rectangular bay and multiple estuary at the north-west corner of East Anglia on the East coast of England, where Norfolk, England, Norfolk meets Lincolnshire and both border the North Sea. One of Britain's broadest estuaries, it i ...

between Old Hunstanton

Old Hunstanton is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk.

It covers an area of and had a population of 47 in 25 households at the 2001 census. The population had risen to 628 at the 2011 Census.

For the purposes of local g ...

and Holme-next-the-Sea

Holme-next-the-Sea is a small village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is situated on the north Norfolk coast some 5 km north-east of the seaside resort of Hunstanton, 30 km north of the town of King's Lynn a ...

, and runs east for about 43 km (27 mi) to Kelling

Kelling (also known as ''Low Kelling'' and as ''Lower Kelling'') is a village and a civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. The village is west of Cromer, north of Norwich, and northeast of London. The village straddles the A149 Coast ...

. The southern boundary runs roughly west to east except where it detours around towns and villages, and never crosses the A149 coast road.

The SSSI has a wide variety of habitats, with bare mud, sand and shingle characterising the intertidal zone

The intertidal zone, also known as the foreshore, is the area above water level at low tide and underwater at high tide (in other words, the area within the tidal range). This area can include several types of habitats with various species o ...

along the whole of the coast, although higher areas may have algae

Algae (; singular alga ) is an informal term for a large and diverse group of photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. It is a polyphyletic grouping that includes species from multiple distinct clades. Included organisms range from unicellular mic ...

or eelgrass Eelgrass is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Zostera'', marine eelgrass

* ''Vallisneria

''Vallisneria'' (named in honor of Antonio Vallisneri) is a genus of freshwater aquatic plant, commonly called eelgrass, tape grass o ...

that are grazed by ducks and geese in winter. The salt marsh

A salt marsh or saltmarsh, also known as a coastal salt marsh or a tidal marsh, is a coastal ecosystem in the upper coastal intertidal zone between land and open saltwater or brackish water that is regularly flooded by the tides. It is dominated ...

es which form on sheltered coasts, in the lee of islands, or behind spits are described in the SSSI notification document as "among the best in Europe" due to their exceptionally diverse flora. Sand dunes occur at several places along the coast, but the best examples are at Holme Dunes

Holme Dunes is a nature reserve near Holme-next-the-Sea in Norfolk. It is managed by the Norfolk Wildlife Trust, and is a National Nature Reserve. Retrieved 28 August 2012. It is part of the North Norfolk Coast Site of Special Scientific Inte ...

, Holkham

Holkham is a small village and civil parish in north Norfolk, England, which includes a stately home and estate, Holkham Hall, and a beach, Holkham Gap, at the centre of Holkham National Nature Reserve.

Geography

The parish has an area of and ...

, Blakeney Point

Blakeney Point (designated as Blakeney National Nature Reserve) is a national nature reserve situated near to the villages of Blakeney, Morston and Cley next the Sea on the north coast of Norfolk, England. Its main feature is a 6.4 km (4& ...

, and Scolt Head Island

Scolt Head Island is an offshore barrier island between Brancaster and Wells-next-the-Sea in north Norfolk. It is in the parish of Burnham Norton and is accessed by a seasonal ferry from the village of Burnham Overy, Overy Staithe. The shingle be ...

. The latter two sites are also important for geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or n ...

research purposes as structures consisting mainly of shingle ridges. Reed bed

A reedbed or reed bed is a natural habitat found in floodplains, waterlogged depressions and

estuaries. Reedbeds are part of a succession from young reeds colonising open water or wet ground through a gradation of increasingly dry ground. As ...

s are fairly localised, but substantial areas occur at Titchwell Marsh, Brancaster and Cley Marshes

Cley Marshes is a nature reserve on the North Sea coast of England just outside the village of Cley next the Sea, Norfolk. A reserve since 1926, it is the oldest of the reserves belonging to the Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT), which is itself the ...

. Grassland is represented by grazing pasture reclaimed from former salt marsh, with wetter areas at Cley and Salthouse

Salthouse is a village and a civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is situated on the salt marshes of North Norfolk. It is north of Holt, west of Sheringham and north of Norwich. The village is on the A149 coast road between ...

marshes. Woodland is limited in the SSSI, although a belt of Corsican pine

''Pinus nigra'', the Austrian pine or black pine, is a moderately variable species of pine, occurring across Southern Europe from the Iberian Peninsula to the eastern Mediterranean, on the Anatolian peninsula of Turkey, Corsica and Cyprus, as wel ...

planted at Holkham has provided shelter for other trees and shrubs to become established.

History

To 1000 AD

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the

Norfolk has a long history of human occupation dating back to the Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός ''palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

, and including significant archaeology

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

. Both modern

Modern may refer to:

History

* Modern history

** Early Modern period

** Late Modern period

*** 18th century

*** 19th century

*** 20th century

** Contemporary history

* Moderns, a faction of Freemasonry that existed in the 18th century

Phil ...

and Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

people were present in the area between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago, before the last glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

, and humans returned as the ice retreated northwards. The archaeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscap ...

record is poor until about 20,000 years ago, partly because of the then prevailing very cold conditions, but also because the coastline was much further north than at present. As the ice retreated during the Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

(10,000–5,000 BCE), the sea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised g ...

rose, filling what is now the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. This brought the Norfolk coastline much closer to its present line, so that many ancient sites are under the sea.Robertson ''et al.'' (2005) pp. 9–22. Early Mesolithic flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and start fir ...

tools with characteristic long blades up to Murphy (2009) p. 14. long found on the present-day coast at Titchwell date from a time when it was from the sea. Other flint tools have been found dating from the Upper Paleolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

(50,000–10,000 BCE) to the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several parts ...

(5,000–2,500 BCE).

By 11,000 BC, the makers of the long blades had gone. Two timber platforms have been identified within the peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficien ...

at Titchwell, and may possibly be rare Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

(2,500–800 BCE) survivals.Robertson (2005) p. 149. Seahenge

Seahenge, also known as Holme I, was a prehistoric monument located in the village of Holme-next-the-Sea, near Old Hunstanton in the English county of Norfolk. A timber circle with an upturned tree root in the centre, Seahenge, along wi ...

is another early Bronze Age site found on the coast at Holme in 1998. It consists of a ring of 55 oak posts and was built in 2049 BC; a similar nearby structure, Holme II, may be almost two centuries older. A large Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

fort at Holkham enclosed 2.5 ha (6.1 acres) at the end of a sandy spit in what was then salt marsh, and remained in use until the defeat of the Iceni

The Iceni ( , ) or Eceni were a Brittonic tribe of eastern Britain during the Iron Age and early Roman era. Their territory included present-day Norfolk and parts of Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, and bordered the area of the Corieltauvi to the we ...

in 47 AD.

Roman period settlements have been discovered all along the Norfolk Coast, notably the complex at Branodunum

Branodunum was an ancient Roman fort to the east of the modern English village of Brancaster in Norfolk. Its Roman name derives from the local Celtic language, and may mean "fort of the raven".

History

The fort, built in the 230s, became later ...

, which covered at least 23 ha (57 acres) near Brancaster. This site included a fort built on the castrum

In the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a po ...

pattern enclosing 2.6 ha (6.3 acres) within its walls, 2.9 m (10 ft) wide. The fort had internal turrets at the corners and was backed by an earth rampart.Edward, Derek A; Green, Christopher J S "The Saxon Shore fort and settlement at Brancaster" pp. 21–28 in Johnson (1977). Early Saxon

The Saxons ( la, Saxones, german: Sachsen, ang, Seaxan, osx, Sahson, nds, Sassen, nl, Saksen) were a group of Germanic

*

*

*

*

peoples whose name was given in the early Middle Ages to a large country (Old Saxony, la, Saxonia) near the Nor ...

sites are scarce close to the Norfolk coast, but a gold bracteate

A bracteate (from the Latin ''bractea'', a thin piece of metal) is a flat, thin, single-sided gold medal worn as jewelry that was produced in Northern Europe predominantly during the Migration Period of the Germanic Iron Age (including the Vende ...

found near Blakeney Chapel

Blakeney Chapel is a ruined building on the coast of North Norfolk, England. Despite its name, it was probably not a chapel, nor is it in the adjoining village of Blakeney, but rather in the parish of Cley next the Sea. The building stood on ...

was a rare and significant 6th-century find, and there is a somewhat later Saxon cemetery at Thornham. The Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercian ...

left few tangible traces within the SSSI, but place names such as Holkham ("ship town") reflect the Viking influence. Saxon building foundations were described as the ruins of "Cley Chapel" on a 1797 map, although it is more likely that they belonged to a barn.

Medieval to nineteenth century

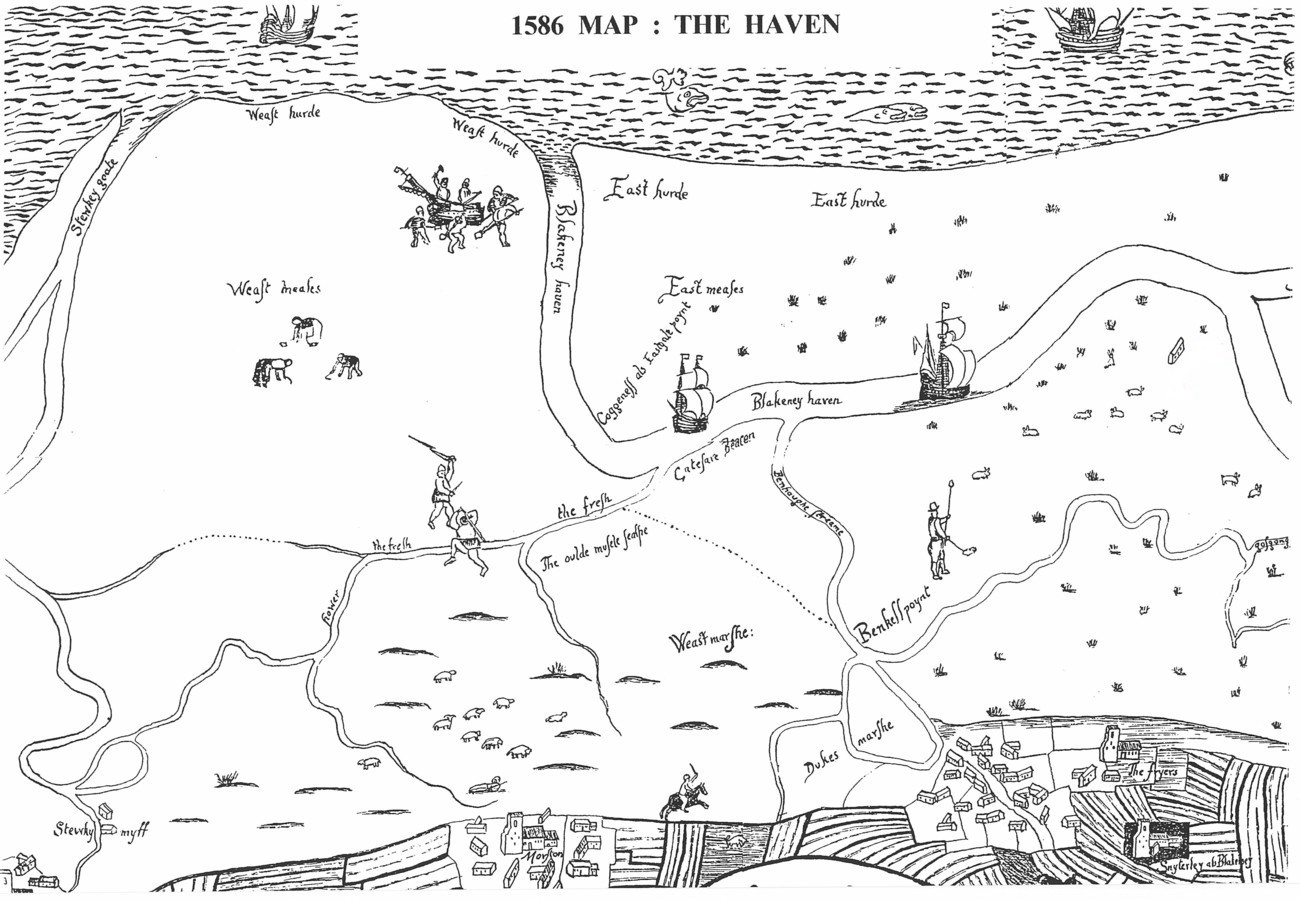

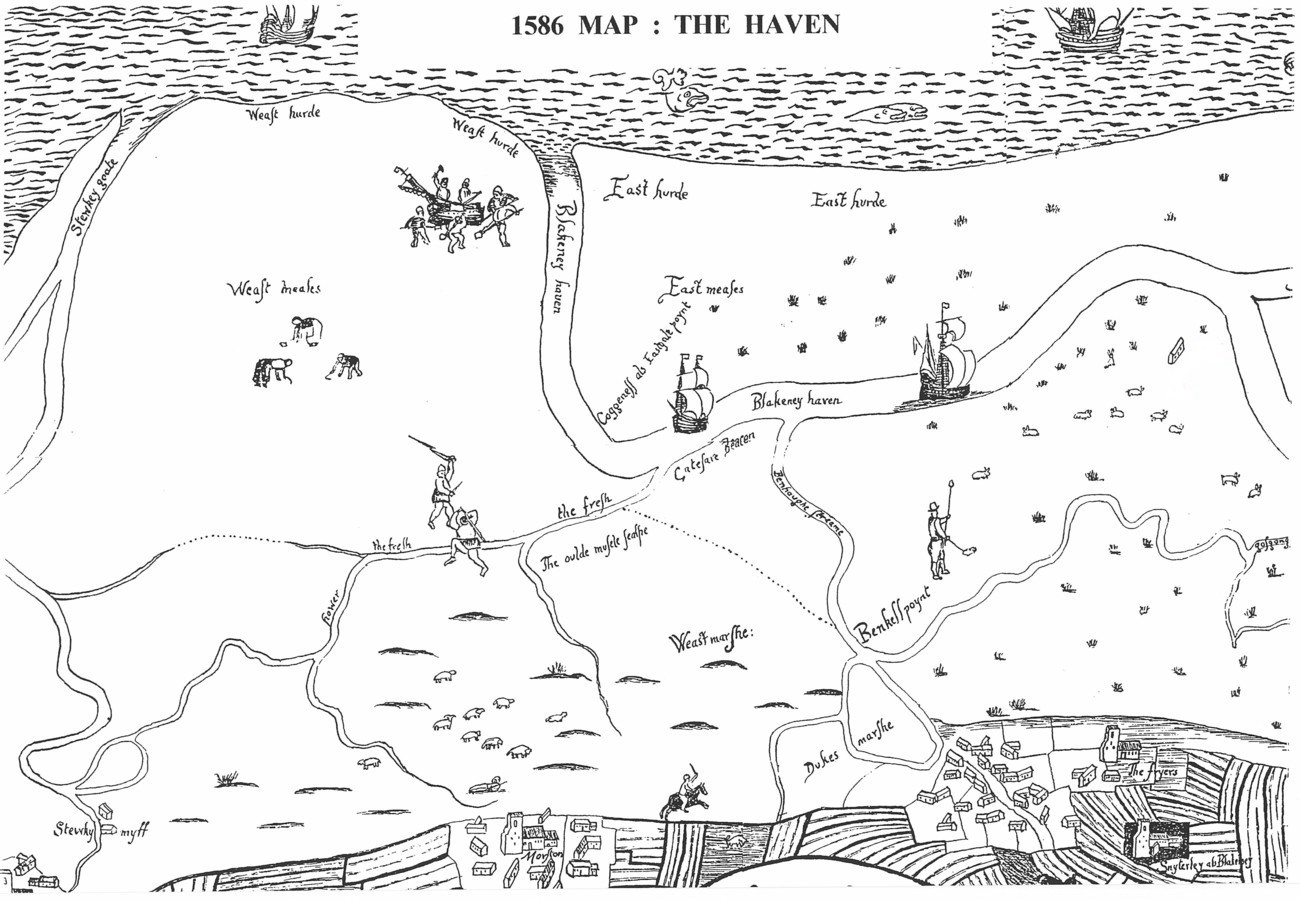

An "eye" is an area of higher ground in the marshes, dry enough to support buildings. Cley Eye had been farmed since the earliest human habitation, and was 28 ha (70 acres) in extent in 1651, but is much reduced by

An "eye" is an area of higher ground in the marshes, dry enough to support buildings. Cley Eye had been farmed since the earliest human habitation, and was 28 ha (70 acres) in extent in 1651, but is much reduced by coastal erosion

Coastal erosion is the loss or displacement of land, or the long-term removal of sediment and rocks along the coastline due to the action of waves, currents, tides, wind-driven water, waterborne ice, or other impacts of storms. The landward ...

.Bishop (1983) pp. 130–133. The Eye and its Saxon barn were accessed by an ancient causeway

A causeway is a track, road or railway on the upper point of an embankment across "a low, or wet place, or piece of water". It can be constructed of earth, masonry, wood, or concrete. One of the earliest known wooden causeways is the Sweet Tra ...

, passable at low tide. A 1588 map showed "Black Joy Forte" in the same area, which may have been intended as a defence against the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

, but was never completed. On the other side of the Glaven, Blakeney Eye had a ditched enclosure during the 11th and 12th centuries, and a building known as "Blakeney Chapel", which was occupied from the 14th century to around 1600, and again in the late 17th century. Despite its name, it is unlikely that it had a religious function. Nearly a third of the mostly 14th-to-16th-century pottery found within the larger and earlier of the two rooms was imported from the continent,Birks (2003) pp. 1–28. reflecting the Glaven ports' importance in international trade at this time.

The sheltered waters of Blakeney Haven

Blakeney is a coastal village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. Blakeney lies within the Norfolk Coast AONB (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) and the North Norfolk Heritage Coast. The North Norfolk Coastal Path travels alo ...

had brought prosperity to the internationally important Glaven ports of Cley

Cley next the Sea (, , is a village and civil parish on the River Glaven in English county of Norfolk, north-west of Holt and east of Blakeney. The main A149 coast road runs through the centre of the village, causing congestion in the su ...

, Wiveton

Wiveton is a village and civil parish in the English county of Norfolk. It is situated on the west bank of the River Glaven, inland from the coast and directly across the river from the village of Cley next the Sea. The larger village of Blaken ...

and Blakeney. Blakeney gained its market charter

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rural ...

in 1222, and the three ports, along with Salthouse, were jointly required to provide three ships for Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

in 1322,Lambert, Craig (2012) "The contributions of the Cinque Ports to the wars of Edward II and Edward III", p. 65 in Gorski (2012). having previously contributed to his father's navy in 1301. By the early 15th century, Blakeney was one of the few ports permitted to trade in horses, gold and silver, through "merchants sworn by oath to the king", which contributed to the town's growing wealth.Robinson (2006) pp. 3–5. In 1640, land reclamation

Land reclamation, usually known as reclamation, and also known as land fill (not to be confused with a waste landfill), is the process of creating new land from oceans, seas, riverbeds or lake beds. The land reclaimed is known as reclamati ...

schemes, especially those by Henry Calthorpe just to the west of Cley, led to the silting up of the shipping channel and relocation of the wharf

A wharf, quay (, also ), staith, or staithe is a structure on the shore of a harbour or on the bank of a river or canal where ships may dock to load and unload cargo or passengers. Such a structure includes one or more berths (mooring locatio ...

,Pevsner & Wilson (2002) p. 435. and further reclamation east of the Glaven meant that all the Glaven ports declined;Labrum (1993) pp. 113–114. Cley and Wiveton silted up in the 17th century, but Blakeney had packet ship

Packet boats were medium-sized boats designed for domestic mail, passenger, and freight transportation in European countries and in North American rivers and canals, some of them steam driven. They were used extensively during the 18th and 19th ...

s until 1840.Pevsner & Wilson (2002) pp. 394–397. Similar marsh reclamation schemes took place elsewhere, often with the same consequence for the local harbours, as for example at Holkham. Only Wells-next-the-Sea

Wells-next-the-Sea is a port town on the north coast of Norfolk, England.

The civil parish has an area of and in 2001 had a population of 2,451,Office for National Statistics & Norfolk County Council (2001). Census population and household c ...

had significant trade into the late 20th century.

Twentieth century coastal defences

Artillery may have been installed at Gun Hill on the coast near Burnham Overy during the

Artillery may have been installed at Gun Hill on the coast near Burnham Overy during the Napoleonic wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, but there were no modern fortifications in north Norfolk at the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Following the German naval attack on Great Yarmouth in November 1914, defences such as trenches, concrete pillboxes and gun batteries were constructed along much of the Norfolk coast. The main bases were outside the SSSI boundaries, but Thornham Marsh was used between 1914 and 1918 by the Royal Flying Corps

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colors =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries =

, decorations ...

as a bombing range

A bombing range usually refers to a remote military aerial bombing and gunnery training range used by combat aircraft to attack ground targets (air-to-ground bombing), or a remote area reserved for researching, developing, testing and evaluatin ...

. A World War I concrete building on Titchwell's west bank was let as holiday accommodation until the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

returned in 1942; some brickwork on Titchwell Marsh is all that remains of a military hospital dating from that period.''Titchwell Marsh before the RSPB''. RSPB information sheet.

There were no new fortifications along this coast at the start of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. After the fall of France in 1940, the threat of invasion led to the creation of new defences. In addition to the installation of anti-tank and other passive obstacles, fourteen coastal batteries, each of two guns, were constructed. Some of these emplacements and other military bases fell within the SSSI area. Four spigot mortar

A mortar is usually a simple, lightweight, man-portable, muzzle-loaded weapon, consisting of a smooth-bore (although some models use a rifled barrel) metal tube fixed to a base plate (to spread out the recoil) with a lightweight bipod mount and a ...

base plates found at Holme dunes may not have originated at that site, since there is no record of such armament there.Birks (2003) p. 60. The marsh at Titchwell was reflooded, and pillboxes built into the beach bank. Between 1942 and 1945, the marsh was used by the Royal Tank Regiment

The Royal Tank Regiment (RTR) is the oldest tank unit in the world, being formed by the British Army in 1916 during the First World War. Today, it is the armoured regiment of the British Army's 12th Armoured Infantry Brigade. Formerly known as th ...

; an armoured fighting vehicle

An armoured fighting vehicle (AFV) is an armed combat vehicle protected by armour, generally combining operational mobility with offensive and defensive capabilities. AFVs can be wheeled or tracked. Examples of AFVs are tanks, armoured car ...

gunnery range was established and banks were constructed for firing practice, with targets set at intervals. Some of the still extant islands were built to hold "pop-up" targets, operated by cables from winches in a building whose foundations now lie below a bird hide. Remains of the triangular concrete track used by the tanks also survive. Military activities continued in the area after the war, and the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

returned to Thornham Marsh between 1950 and 1959. Bombing practice was supervised from a control tower, which was demolished in 1962, leaving only a concrete structure opposite the end of Titchwell's west bank. The remains of two World War II Covenanter tank

The Cruiser tank Mk V or A13 Mk III Covenanter was a British cruiser tank of the Second World War. The Covenanter was the first cruiser tank design to be given a name. Designed by the London, Midland and Scottish Railway as a better-armoured re ...

s, probably used as targets, are sometimes exposed at low tide. The SS ''Vina'', an 1894 cargo steamer, was anchored offshore in 1944 for use as an RAF target, but a gale dragged her to the sands off Titchwell, where the wreck can still be seen at low tide.

Brancaster beach had a base including three pillboxes, Nissen hut

A Nissen hut is a prefabricated steel structure for military use, especially as barracks, made from a half-cylindrical skin of corrugated iron. Designed during the First World War by the American-born, Canadian-British engineer and inventor Majo ...

s and two gun emplacements, and another possible base, comprising about fifty different structures, was located in a salt marsh north-east of Burnham Overy Staithe. A wreck at the west end of Scolt Head Island was used as a bombing target, and the remains of a Blenheim bomber

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber aircraft designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company (Bristol) which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until t ...

were found at the north of the island in 2004.

Royal Artillery

The Royal Regiment of Artillery, commonly referred to as the Royal Artillery (RA) and colloquially known as "The Gunners", is one of two regiments that make up the artillery arm of the British Army. The Royal Regiment of Artillery comprises t ...

military fortifications were established at Cley beach, including two 6-inch (15.24 cm) guns, five buildings, two pillboxes, a minefield

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

, and concrete anti-tank blocks. A spigot mortar emplacement and an Allan Williams Turret machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles) a ...

emplacement were sited closer to the village. One of the pillboxes and remains of the beach gun emplacements were still surviving as of 2012. The military camp accommodated 160 men and was later used to hold prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

. Near the end of the war, the camp was used to house East European refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s, and was finally pulled down in 1948. Many of the wartime buildings were destroyed by the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

in 1955, but the generator

Generator may refer to:

* Signal generator, electronic devices that generate repeating or non-repeating electronic signals

* Electric generator, a device that converts mechanical energy to electrical energy.

* Generator (circuit theory), an eleme ...

house was taken over by the coastguard

A coast guard or coastguard is a maritime security organization of a particular country. The term embraces wide range of responsibilities in different countries, from being a heavily armed military force with customs and security duties to ...

service as an observation post. It was acquired by the NWT in 1983, and the upper part was used as a look-out, while the larger lower section became a beach café. The building was overwhelmed by shingle in a storm in 2008, and subsequently demolished.

Conservation

The first step towards the protection of this coast by a national conservation body was the purchase of Blakeney Point from the Calthorpe family by banker

The first step towards the protection of this coast by a national conservation body was the purchase of Blakeney Point from the Calthorpe family by banker Charles Rothschild

Nathaniel Charles Rothschild (9 May 1877 – 12 October 1923), known as "Charles", was an English banker and entomologist and a member of the Rothschild family. He is remembered for The Rothschild List, a list he made in 1915 of 284 sites acros ...

in 1912. Rothschild gave the property to the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

in 1912, which has managed it since. In 1926, another early protected area was created when Norfolk birdwatcher

Birdwatching, or birding, is the observing of birds, either as a recreational activity or as a form of citizen science. A birdwatcher may observe by using their naked eye, by using a visual enhancement device like binoculars or a telescope, by ...

Dr Sydney Long bought the land which makes up the Cley Marshes reserve for the sum of £5,100, to be held "in perpetuity as a bird breeding sanctuary". Long then went on to establish the Norfolk Wildlife Trust

The Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT) is one of 46 wildlife trusts covering Great Britain, Northern Ireland, Isle of Man and Alderney. Founded in 1926, it is the oldest of all the trusts. It has over 35,500 members and eight local groups and it mana ...

(NWT).

The current SSSI was created in 1986 from pre-existing SSSIs at Blakeney Point, Holme Dunes, Cley, and Salthouse Marshes (all designated in 1954), Morston Saltmarshes and Brancaster Manor

Brancaster Manor is a saltmarsh owned by the National Trust near Brancaster, Norfolk covering 810 ha (2,000 acres).Ryan (1969) p 165 It was originally purchased by the Brancaster Memorial Trust in 1964,Rodgers ''et al'' (2010 ) p.167 and ...

(1968), Stiffkey

Stiffkey () is a village and civil parish on the north coast of the English county of Norfolk. It is situated on the A149 coast road, some east of Wells-next-the-Sea, west of Blakeney, and north-west of the city of Norwich.Ordnance Survey ( ...

Saltmarshes (1969), Thornham Marshes (1972) and Titchwell Marshes (1973), together with the national nature reserves (NNRs) at Scolt Head Island (1967)Allen & Pye (1992) p. 148. and Holkham (1968),Rowley (2006) p. 365. and substantial formerly undesignated areas.

Although much of the SSSI is in private hands, considerable areas are managed by large conservation organisations. As well as the two NNRs, there is an RSPB

The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) is a Charitable_organization#United_Kingdom, charitable organisation registered in Charity Commission for England and Wales, England and Wales and in Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator, ...

reserve at Titchwell Marsh, and Norfolk Wildlife Trust reserves are at Cley and Salthouse Marshes. The NWT also manages the Holme Dunes NNR. In addition to Blakeney Point, the National Trust owns land at Brancaster Staithe

Brancaster Staithe is a village on the north coast of the English county of Norfolk. Brancaster Staithe merges with Burnham Deepdale, forming one village.

Brancaster Staithe is in the civil parish of Brancaster, together with Burnham Deepdale and ...

.

The SSSI covers 7,700 ha (19,027 acres) and is additionally protected through Natura 2000

Natura 2000 is a network of nature protection areas in the territory of the European Union. It is made up of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas designated under the Habitats Directive and the Birds Directive, respectively ...

, Special Protection Area

A Special Protection Area (SPA) is a designation under the European Union Directive on the Conservation of Wild Birds. Under the Directive, Member States of the European Union (EU) have a duty to safeguard the habitats of migratory birds and cert ...

(SPA) and Ramsar Ramsar may refer to:

* Places so named:

** Ramsar, Mazandaran, city in Iran

** Ramsar, Rajasthan, village in India

* Eponyms of the Iranian city:

** Ramsar Convention concerning wetlands, signed in Ramsar, Iran

** Ramsar site, wetland listed in ...

listings, and is part of the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Scolt Head Island and the coast from the Holkham NNR to Salthouse are a Biosphere Reserve

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or o ...

.

Fauna and flora

Birds

The SSSI is designated as a Special Protection Area for birds for its variety of coastal habitats. The large breeding colonies of

The SSSI is designated as a Special Protection Area for birds for its variety of coastal habitats. The large breeding colonies of Sandwich tern

The Sandwich tern (''Thalasseus sandvicensis'') is a tern in the family Laridae. It is very closely related to the lesser crested tern (''T. bengalensis''), Chinese crested tern (''T. bernsteini''), Cabot's tern (''T. acuflavidus''), and elegan ...

s and little tern

The little tern (''Sternula albifrons'') is a seabird of the family Laridae. It was formerly placed into the genus ''Sterna'', which now is restricted to the large white terns. The genus name is a diminutive of ''Sterna'', "tern". The specific '' ...

s, especially those at Blakeney Point and Scolt Head Island, are of "European importance" as defined in the Birds Directive

The Birds Directive (formally known as Council Directive 2009/147/EC on the conservation of wild birds) is the oldest piece of EU legislation on the environment and one of its cornerstones which was unanimously adopted in April 1979 as the Dire ...

, and the coast as a whole meets Natural England's criteria for nationally important populations of common tern

The common tern (''Sterna hirundo'') is a seabird in the family Laridae. This bird has a circumpolar distribution, its four subspecies breeding in temperate and subarctic regions of Europe, Asia and North America. It is strongly migratory ...

s, pied avocet

The pied avocet (''Recurvirostra avosetta'') is a large black and white wader in the avocet and stilt family, Recurvirostridae. They breed in temperate Europe and across the Palearctic to Central Asia then on to the Russian Far East. It is a mig ...

s and reedbed specialists like western marsh harrier

The western marsh harrier (''Circus aeruginosus'') is a large harrier, a bird of prey from temperate and subtropical western Eurasia and adjacent Africa. It is also known as the Eurasian marsh harrier. Formerly, a number of relatives were includ ...

s, Eurasian bittern

The Eurasian bittern or great bittern (''Botaurus stellaris'') is a wading bird in the bittern subfamily (Botaurinae) of the heron family Ardeidae. There are two subspecies, the northern race (''B. s. stellaris'') breeding in parts of Europe and ...

s and bearded reedling

The bearded reedling (''Panurus biarmicus'') is a small, sexual dimorphism, sexually dimorphic reed bed, reed-bed passerine bird. It is frequently known as the bearded tit, due to some similarities to the long-tailed tit, or the bearded parrotbil ...

s. Other birds nesting in the wetlands include the northern lapwing

The northern lapwing (''Vanellus vanellus''), also known as the peewit or pewit, tuit or tew-it, green plover, or (in Ireland and Britain) pyewipe or just lapwing, is a bird in the lapwing subfamily. It is common through temperate Eurosiberia. ...

, common redshank

The common redshank or simply redshank (''Tringa totanus'') is a Eurasian wader in the large family Scolopacidae.

Taxonomy

The common redshank was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his ...

, and sedge

The Cyperaceae are a family of graminoid (grass-like), monocotyledonous flowering plants known as sedges. The family is large, with some 5,500 known species described in about 90 genera, the largest being the "true sedges" genus ''Carex'' wit ...

, reed

Reed or Reeds may refer to:

Science, technology, biology, and medicine

* Reed bird (disambiguation)

* Reed pen, writing implement in use since ancient times

* Reed (plant), one of several tall, grass-like wetland plants of the order Poales

* ...

and Cetti's warbler

Cetti's warbler (''Cettia cetti'') is a small, brown bush-warbler which breeds in southern and central Europe, northwest Africa and the east Palearctic as far as Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan. The sexes are alike. The bird is named after t ...

s. Ringed plovers and Eurasian oystercatcher

The Eurasian oystercatcher (''Haematopus ostralegus'') also known as the common pied oystercatcher, or palaearctic oystercatcher, or (in Europe) just oystercatcher, is a wader in the oystercatcher bird family Haematopodidae. It is the most widesp ...

s lay their eggs on bare sand in the dunes. Little egrets, Eurasian spoonbill

The Eurasian spoonbill (''Platalea leucorodia''), or common spoonbill, is a wading bird of the ibis and spoonbill family Threskiornithidae. The genus name ''Platalea'' is from Latin and means "broad", referring to the distinctive shape of the b ...

s, ruff

Ruff may refer to:

Places

*Ruff, Virginia, United States, an unincorporated community

*Ruff, Washington, United States, an unincorporated community

Other uses

*Ruff (bird) (''Calidris pugnax'' or ''Philomachus pugnax''), a bird in the wader fami ...

s and black-tailed godwit

The black-tailed godwit (''Limosa limosa'') is a large, long-legged, long-billed shorebird first described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758. It is a member of the godwit genus, ''Limosa''. There are four subspecies, all with orange head, neck and chest ...

s are present for much of the year,Harrup & Redman (2010) pp. 235–250. and the egret and spoonbill have both started nesting within the SSSI.Norfolk Wildlife Trust (2011) pp. 6–7.

In spring and early summer, migrant birds including the little gull

The little gull (''Hydrocoloeus minutus'' or ''Larus minutus''), is a small gull that breeds in northern Europe and across the Palearctic. The genus name ''Hydrocoloeus'' is from Ancient Greek , "water", and , a sort of web-footed bird. The speci ...

, black tern

The black tern (''Chlidonias niger'') is a small tern generally found in or near inland water in Europe, Western Asia and North America. As its name suggests, it has predominantly dark plumage. In some lights it can appear blue in the breeding se ...

, Temminck's stint

Temminck's stint (''Calidris temminckii'') is a small wader. This bird's common name and Latin binomial commemorate the Dutch naturalist Coenraad Jacob Temminck. The genus name is from Ancient Greek ''kalidris'' or ''skalidris'', a term used by ...

and garganey

The garganey (''Spatula querquedula'') is a small dabbling duck. It breeds in much of Europe and across the Palearctic, but is strictly migratory, with the entire population moving to southern Africa, India (in particular Santragachi), Banglades ...

may pass through on their way to breed elsewhere. In the autumn, birds arrive from the north; some, such as whimbrels, curlew sandpiper

The curlew sandpiper (''Calidris ferruginea'') is a small wader that breeds on the tundra of Arctic Siberia.

It is strongly migratory, wintering mainly in Africa, but also in south and southeast Asia and in Australia and New Zealand. It is a va ...

s and little stint

The little stint (''Calidris minuta'' or ''Erolia minuta''), is a very small wader. It breeds in arctic Europe and Asia, and is a long-distance migrant, wintering south to Africa and south Asia. It occasionally is a vagrant to North America a ...

s, just pausing for a few days to refuel before continuing south, others staying for the winter. Offshore, great

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

and Arctic skua

The parasitic jaeger (''Stercorarius parasiticus''), also known as the Arctic skua, Arctic jaeger or parasitic skua, is a seabird in the skua family Stercorariidae. It is a migratory species that breeds in Northern Scandinavia, Scotland, Iceland ...

s, northern gannet

The northern gannet (''Morus bassanus'') is a seabird, the largest species of the gannet family, Sulidae. It is native to the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, breeding in Western Europe and Northeastern North America. It is the largest seabird in t ...

s and black-legged kittiwake

The black-legged kittiwake (''Rissa tridactyla'') is a seabird species in the gull family Laridae.

This species was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae'' as ''Larus tridactylus''. The English ...

s may pass close by in favourable winds. Large numbers of ducks winter along the coast, including many Eurasian wigeon

The Eurasian wigeon or European wigeon (''Mareca penelope''), also known as the widgeon or the wigeon, is one of three species of wigeon in the dabbling duck genus ''Mareca''. It is common and widespread within its Palearctic range.

Taxonomy

Th ...

s, Eurasian teal

The Eurasian teal (''Anas crecca''), common teal, or Eurasian green-winged teal is a common and widespread duck that breeds in temperate Eurosiberia and migrates south in winter. The Eurasian teal is often called simply the teal due to being th ...

s, mallard

The mallard () or wild duck (''Anas platyrhynchos'') is a dabbling duck that breeds throughout the temperate and subtropical Americas, Eurasia, and North Africa, and has been introduced to New Zealand, Australia, Peru, Brazil, Uruguay, Arge ...

s and gadwall

The gadwall (''Mareca strepera'') is a common and widespread dabbling duck in the family Anatidae.

Taxonomy

The gadwall was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his landmark 1758 10th edition of ''Systema Naturae''. DNA studies have shown that ...

s, goldeneyes and northern pintail

The pintail or northern pintail (''Anas acuta'') is a duck species with wide geographic distribution that breeds in the northern areas of Europe and across the Palearctic and North America. It is migratory and winters south of its breeding ra ...

s. Red-throated divers are usually on the sea, and brent geese

The brant or brent goose (''Branta bernicla'') is a small goose of the genus ''Branta''. There are three subspecies, all of which winter along temperate-zone sea-coasts and breed on the high-Arctic tundra.

The Brent oilfield was named after ...

feed on sea lettuce

The sea lettuces comprise the genus ''Ulva'', a group of edible green algae that is widely distributed along the coasts of the world's oceans. The type species within the genus ''Ulva'' is ''Ulva lactuca'', wikt:lactuca, ''lactuca'' being Latin ...

and other green algae

The green algae (singular: green alga) are a group consisting of the Prasinodermophyta and its unnamed sister which contains the Chlorophyta and Charophyta/Streptophyta. The land plants (Embryophytes) have emerged deep in the Charophyte alga as ...

. Barn owl

The barn owl (''Tyto alba'') is the most widely distributed species of owl in the world and one of the most widespread of all species of birds, being found almost everywhere except for the polar and desert regions, Asia north of the Himalaya ...

s and sometimes hen harriers quarter the marshes in winter, and snow bunting

The snow bunting (''Plectrophenax nivalis'') is a passerine bird in the family Calcariidae. It is an Arctic specialist, with a circumpolar Arctic breeding range throughout the northern hemisphere. There are small isolated populations on a few hig ...

flocks can be found on the beaches. Thousands of geese, mainly pink-footed, roost at Holkham.

The SSSI's north-facing east coast location can be favourable for huge numbers of migrating birds when the weather conditions are right. These may include vagrant

Vagrancy is the condition of homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants (also known as bums, vagabonds, rogues, tramps or drifters) usually live in poverty and support themselves by begging, scavenging, petty theft, temporar ...

rarities. A black-winged stilt

The black-winged stilt (''Himantopus himantopus'') is a widely distributed very long-legged wader in the avocet and stilt family (Recurvirostridae). The scientific name ''H. himantopus'' is sometimes applied to a single, almost cosmopolitan speci ...

, which acquired the nickname "Sammy", arrived at Titchwell in 1993 and became a permanent resident up to its disappearance in 2005. Other major rarities included a western sandpiper

The western sandpiper (''Calidris mauri'') is a small shorebird. The genus name is from Ancient Greek ''kalidris'' or ''skalidris'', a term used by Aristotle for some grey-coloured waterside birds. The specific ''mauri'' commemorates Italian bota ...

at Cley in 2012, a rufous-tailed robin

The rufous-tailed robin (''Larvivora sibilans'') is a small passerine bird. Its breeding range extends from southern Siberia and the Sea of Okhotsk to southern China and southeastern Asia.

It has a number of alternative English names: pseudo ...

at Warham Greens in 2011, and a black-winged pratincole

The black-winged pratincole (''Glareola nordmanni'') is a wader in the pratincole bird family, Glareolidae. The genus name is a diminutive of Latin ''glarea'', "gravel", referring to a typical nesting habitat for pratincoles. The species nam ...

at Titchwell in 2009.

Other animals

American mink

The American mink (''Neogale vison'') is a semiaquatic species of mustelid native to North America, though human intervention has expanded its range to many parts of Europe, Asia and South America. Because of range expansion, the American mink i ...

, but also habitat loss and water pollution. East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

n sites of national importance for this species include Cley, Titchwell and other Norfolk coastal sites. Brown hares are widespread, and European otter

The Eurasian otter (''Lutra lutra''), also known as the European otter, Eurasian river otter, common otter, and Old World otter, is a semiaquatic mammal native to Eurasia. The most widely distributed member of the otter subfamily (Lutrinae) of th ...

s may be seen at several locations. Both common

Common may refer to:

Places

* Common, a townland in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland

* Boston Common, a central public park in Boston, Massachusetts

* Cambridge Common, common land area in Cambridge, Massachusetts

* Clapham Common, originally com ...

and grey seal

The grey seal (''Halichoerus grypus'') is found on both shores of the North Atlantic Ocean. In Latin Halichoerus grypus means "hook-nosed sea pig". It is a large seal of the family Phocidae, which are commonly referred to as "true seals" or " ...

s can be seen at the Blakeney Point colony and off the beaches.Taylor (2009) pp. 136–137. The common frog

The common frog or grass frog (''Rana temporaria''), also known as the European common frog, European common brown frog, European grass frog, European Holarctic true frog, European pond frog or European brown frog, is a semi-aquatic amphibian o ...

, common toad

The common toad, European toad, or in Anglophone parts of Europe, simply the toad (''Bufo bufo'', from Latin ''bufo'' "toad"), is a frog found throughout most of Europe (with the exception of Ireland, Iceland, and some Mediterranean islands), in ...

and common lizard

The viviparous lizard, or common lizard, (''Zootoca vivipara'', formerly ''Lacerta vivipara''), is a Eurasian lizard. It lives farther north than any other species of non-marine reptile, and is named for the fact that it is viviparous, meaning it ...

all occur in suitable habitats,Norfolk Wildlife Trust (2005) pp. 12–15. and the rare natterjack toad

The natterjack toad (''Epidalea calamita'') is a toad native to sandy and heathland areas of Europe. Adults are 60–70 mm in length, and are distinguished from common toads by a yellow line down the middle of the back and parallel paratoid g ...

breeds at Holkham and Holme.Natural England (2009) pp. 7–15.

The green hairstreak

The green hairstreak (''Callophrys rubi'') is a small butterfly in the family Lycaenidae.

Etymology

The genus name '' Callophrys'' is a Greek word meaning "beautiful eyebrows", while the species Latin name ''rubi'' derives from ''Rubus'' (bramb ...

, purple hairstreak

The purple hairstreak (''Favonius quercus'') is a butterfly in the family Lycaenidae distributed throughout much of Europe, North Africa, Anatolia, Caucasia, and Transcaucasia.

The larva feeds on ''Quercus robur'', ''Quercus petraea'', ''Querc ...

, hummingbird hawk-moth

The hummingbird hawk-moth (''Macroglossum stellatarum'') is a species of hawk moth found across temperate regions of Eurasia. The species is named for its similarity to hummingbirds, as they feed on the nectar of tube-shaped flowers using their ...

and ghost moth

The ghost moth or ghost swift (''Hepialus humuli'') is a moth of the family Hepialidae. It is common throughout Europe, except for in the far south-east.

Female ghost moths are larger than males, and exhibit sexual dimorphism with their differ ...

are sometimes seen, particularly in the woods at Holkham, along with the common butterfly and moth species. In some years the clouded yellow, Camberwell beauty

''Nymphalis antiopa'', known as the mourning cloak in North America and the Camberwell beauty in Britain, is a large butterfly native to Eurasia and North America.

The immature form of this species is sometimes known as the spiny elm caterpillar ...

, painted lady

''Vanessa cardui'' is the most widespread of all butterfly species. It is commonly called the painted lady, or formerly in North America the cosmopolitan.

Description

File:Vanessa cardui MHNT CUT 2013 3 14 Pontfaverger-Moronvilliers Dos. ...

or diamondback moth

The diamondback moth (''Plutella xylostella''), sometimes called the cabbage moth, is a moth species of the family Plutellidae and genus '' Plutella''. The small, grayish-brown moth sometimes has a cream-colored band that forms a diamond along ...

may be seen, and the silver Y

The silver Y (''Autographa gamma'') is a migratory moth of the family Noctuidae which is named for the silvery Y-shaped mark on each of its forewings.

Description

The silver Y is a medium-sized moth with a wingspan of 30 to 45 mm. The wing ...

can sometimes occur in huge numbers. The dune tiger beetle is a nationally rare denizen of moist sand dunes.

The lagoons behind the shingle beach at Salthouse and Cley are salty due to the percolation of seawater through the bank.Net Gain (2011) 574–586. These saline lagoons may cover mud, firm sand or submerged vegetation, and hold some rare and threatened invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s including the starlet sea anemone, lagoon sand shrimp, Atlantic ditch shrimp, and lagoon cockle. These marshes are the only reliable UK site for the water beetle yellow pogonus, and even here it is localised and hard to find.

Plants

On exposed parts of the coast, the muds and sands are scoured by the tides, and have no vegetation except possibly algae or eelgrass. Where the shoreline is more protected, internationally important salt marshes can form, with several uncommon species. The salt marshes contains glassworts and common cord grass in the most exposed regions, with a succession of plants following on as the marsh becomes more established: first

On exposed parts of the coast, the muds and sands are scoured by the tides, and have no vegetation except possibly algae or eelgrass. Where the shoreline is more protected, internationally important salt marshes can form, with several uncommon species. The salt marshes contains glassworts and common cord grass in the most exposed regions, with a succession of plants following on as the marsh becomes more established: first sea aster

''Tripolium pannonicum'', called sea aster or seashore aster and often known by the synonyms ''Aster tripolium'' or ''Aster pannonicus'', is a flowering plant, native to Eurasia and northern Africa, that is confined in its distribution to salt ma ...

, then mainly sea lavender

''Limonium'' is a genus of 120 flowering plant species. Members are also known as sea-lavender, statice, caspia or marsh-rosemary. Despite their common names, species are not related to the lavenders or to rosemary. They are instead in Plumbag ...

, with sea purslane in the creeks and smaller areas of sea plantain and other common marsh plants. The uncommon spiral tasselweed and long-bracted sedge are other lower salt marsh specialists. Scrubby sea-blite and matted sea lavender are characteristic plants of the drier upper salt marsh, although they are uncommon in the UK away from this coast. They may occur alongside scarce species including lesser centaury, curved hard-grass and sea pearlwort, with soft hornwort in the dykes.

Grasses such as sea couch grass and sea poa grass are important in the driest areas of the marshes, and on the coastal dunes, where marram grass

''Ammophila'' (synonymous with ''Psamma'' P. Beauv.) is a genus of flowering plants consisting of two or three very similar species of grasses. The common names for these grasses include marram grass, bent grass, and beachgrass. These grasses ar ...

, sand couch-grass, lyme-grass

''Leymus arenarius'' is a psammophilic (sand-loving) species of grass in the family Poaceae, native to the coasts of Atlantic and Northern Europe. ''Leymus arenarius'' is commonly known as sand ryegrass, sea lyme grass, or simply lyme grass.

and red fescue

''Festuca rubra'' is a species of grass known by the common name red fescue or creeping red fescue. It is widespread across much of the Northern Hemisphere and can tolerate many habitats and climates. It is best adapted to well-drained soils in ...

help to bind the sand. Sea holly Sea holly is a common name for several plants and may refer to:

* ''Acanthus ebracteatus''

* '' Eryngium'' species, especially:

** ''Eryngium maritimum

''Eryngium maritimum'', the sea holly or sea eryngo, or sea eryngium, is a perennial species ...

and sand sedge

''Carex arenaria'', or sand sedge, is a species of perennial sedge of the genus ''Carex'' which is commonly found growing in dunes and other sandy habitats, as the species epithet suggests (Latin , "sandy"). It grows by long stolons under the s ...

are other specialists of this arid habitat, and petalwort is a nationally rare bryophyte

The Bryophyta s.l. are a proposed taxonomic division containing three groups of non-vascular land plants (embryophytes): the liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Bryophyta s.s. consists of the mosses only. They are characteristically limited in ...

found on damper dunes. Bird's-foot trefoil

''Lotus corniculatus'' is a flowering plant in the pea family Fabaceae, native to grasslands in temperate Eurasia and North Africa. Common names include common bird's-foot trefoil, eggs and bacon, birdsfoot deervetch, and just bird's-foot trefo ...

, pyramidal orchid

''Anacamptis pyramidalis'', the pyramidal orchid, is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the genus ''Anacamptis'' of the family Orchidaceae. The scientific name ''Anacamptis'' derives from Greek ανακάμτειν 'anakamptein' meaning 'b ...

, bee orchid Bee orchid is a common name for several orchids and may refer to:

*'' Cottonia peduncularis'', a species of orchid from India and Sri Lanka

*'' Diuris carinata'', a species of orchid from the south-west of Western Australia

*'' Ida barringtoniae'', ...

and carline thistle

''Carlina vulgaris'', the carline thistle, is a plant species of the genus '' Carlina''.

It is a biennial that grows on limestone, chalky or other alkaline grasslands or dunes. The flowers are clusters of very small brown florets surrounded by br ...

flower on the dunes, and Holkham's Corsican pines shelter creeping lady's tresses and yellow bird's nest orchids. The shingle ridges on Scolt Head Island and from Blakeney Point east to Salthouse attract biting stonecrop, sea campion

''Silene uniflora'' is a species of flowering plant in the family Caryophyllaceae known by the common name sea campion.

Description

''Silene uniflora'' is a herbaceous perennial plant, similar in appearance to the bladder campion (''Silene vulga ...

, yellow horned poppy

''Glaucium flavum'', the yellow horned poppy, yellow hornpoppy or sea poppy, is a summer flowering plant in the family Papaveraceae. It is native to Europe, Northern Africa, Macaronesia and temperate zones in Western Asia. The plant grows on th ...

, sea thrift and sea beet

The sea beet, ''Beta vulgaris'' subsp. ''maritima'' ((L.) Arcangeli.), is a member of the family Amaranthaceae, previously of the Chenopodiaceae. Carl Linnaeus first described ''Beta vulgaris'' in 1753; in the second edition of '' Species Plantaru ...

. Sea barley is a scarcer species of this habitat.

The reedbeds, the largest of which are at the Cley, Salthouse and Titchwell reserves, are dominated by common reed

''Phragmites australis'', known as the common reed, is a species of plant. It is a broadly distributed wetland grass that can grow up to tall.

Description

''Phragmites australis'' commonly forms extensive stands (known as reed beds), which may ...

, and salt marsh rush, brackish water crowfoot, sea clubrush

''Bolboschoenus maritimus'' is a species of flowering plant from family Cyperaceae. Common names for this species include sea clubrush, cosmopolitan bulrush, alkali bulrush, saltmarsh bulrush, and bayonet grass. It is found in seaside wetland hab ...

and common bulrush also occur in the various wetland habitats. The coastal pastures at Cley and Salthouse Marshes have jointleaf rush, common silverweed, and less common grasses such as annual beard grass, marsh foxtail

''Alopecurus geniculatus'' is a species of grass known by the common name water foxtail or marsh foxtail.

It is native to much of Eurasia and introduced into North America, South America, and Australia. It grows in moist areas.

''Alopecurus ge ...

, and slender hare's-ear

''Bupleurum tenuissimum'', the slender hare's-ear, is a coastal plant of the family Apiaceae

Apiaceae or Umbelliferae is a family of mostly aromatic flowering plants named after the type genus ''Apium'' and commonly known as the celery, carr ...

. The flat land just inland from the dunes at Holkham was reclaimed from the marshes by the nineteenth century and was initially used for grazing. It was made arable during World War II, but the water levels have been raised to make the fields attractive to breeding and wintering birds. The pastures are of international importance for the tens of thousands of geese and ducks that feed there in the winter months.

Access and facilities

Scolt Head Island is accessed by a ferry from

Scolt Head Island is accessed by a ferry from Burnham Overy Staithe