Neptune Bay on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Neptune is the eighth  , representing Neptune's

, representing Neptune's

Some of the earliest recorded observations ever made through a

Some of the earliest recorded observations ever made through a  In 1845–1846,

In 1845–1846,

, Nineplanets.org In

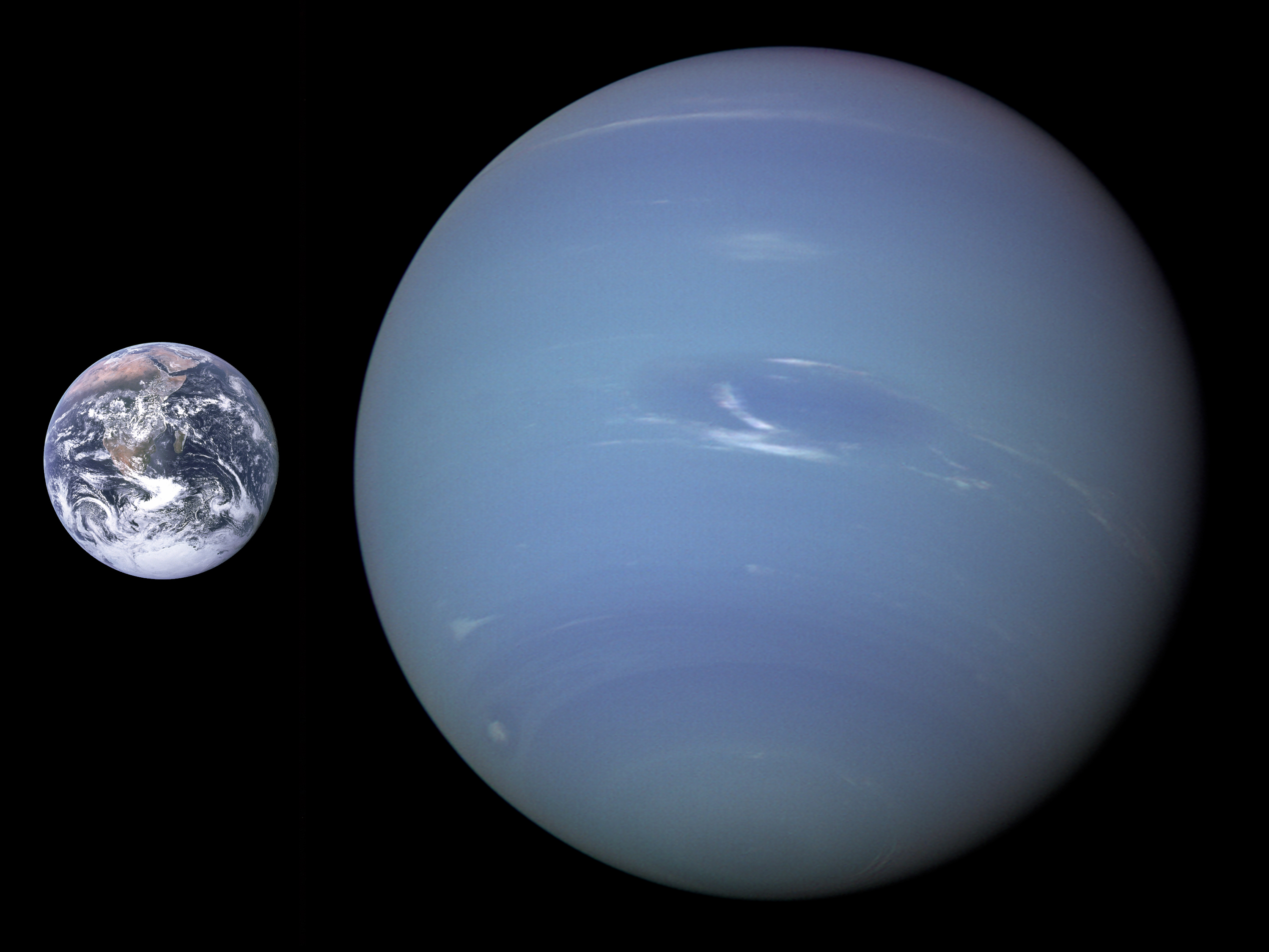

Neptune's mass of 1.0243 kg is intermediate between Earth and the larger

Neptune's mass of 1.0243 kg is intermediate between Earth and the larger

The mantle is equivalent to 10 to 15 Earth masses and is rich in water, ammonia and methane. As is customary in planetary science, this mixture is referred to as

The mantle is equivalent to 10 to 15 Earth masses and is rich in water, ammonia and methane. As is customary in planetary science, this mixture is referred to as

At high altitudes, Neptune's atmosphere is 80%

At high altitudes, Neptune's atmosphere is 80%  Models suggest that Neptune's troposphere is banded by clouds of varying compositions depending on altitude. The upper-level clouds lie at pressures below one bar, where the temperature is suitable for methane to condense. For pressures between one and five bars (100 and 500 kPa), clouds of ammonia and

Models suggest that Neptune's troposphere is banded by clouds of varying compositions depending on altitude. The upper-level clouds lie at pressures below one bar, where the temperature is suitable for methane to condense. For pressures between one and five bars (100 and 500 kPa), clouds of ammonia and

Neptune's weather is characterised by extremely dynamic storm systems, with winds reaching speeds of almost —nearly reaching

Neptune's weather is characterised by extremely dynamic storm systems, with winds reaching speeds of almost —nearly reaching

File:A storm is coming Neptune.tif, The appearance of a Northern Great Dark Spot in 2018 is evidence of a huge storm brewing.

File:Neptune Dark Spot Jr. Hubble.png, The Northern Great Dark Spot and a smaller companion storm imaged by Hubble in 2020

File:Neptune's Great Dark Spot.jpg, alt=The Great Dark Spot, as imaged by Voyager 2, The Great Dark Spot in a color-uncalibrated image by ''Voyager 2.''

File:Neptune’s shrinking vortex.jpg, Neptune's shrinking vortex

The average distance between Neptune and the Sun is (about 30.1

The average distance between Neptune and the Sun is (about 30.1

—Numbers generated using the Solar System Dynamics Group, Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. The elliptical orbit of Neptune is inclined 1.77° compared to that of Earth. The axial tilt of Neptune is 28.32°, which is similar to the tilts of Earth (23°) and Mars (25°). As a result, Neptune experiences similar seasonal changes to Earth. The long orbital period of Neptune means that the seasons last for forty Earth years. Its sidereal rotation period (day) is roughly 16.11 hours. Because its axial tilt is comparable to Earth's, the variation in the length of its day over the course of its long year is not any more extreme. Because Neptune is not a solid body, its atmosphere undergoes

Neptune's orbit has a profound impact on the region directly beyond it, known as the

Neptune's orbit has a profound impact on the region directly beyond it, known as the

The formation of the ice giants, Neptune and Uranus, has proven difficult to model precisely. Current models suggest that the matter density in the outer regions of the Solar System was too low to account for the formation of such large bodies from the traditionally accepted method of core

The formation of the ice giants, Neptune and Uranus, has proven difficult to model precisely. Current models suggest that the matter density in the outer regions of the Solar System was too low to account for the formation of such large bodies from the traditionally accepted method of core

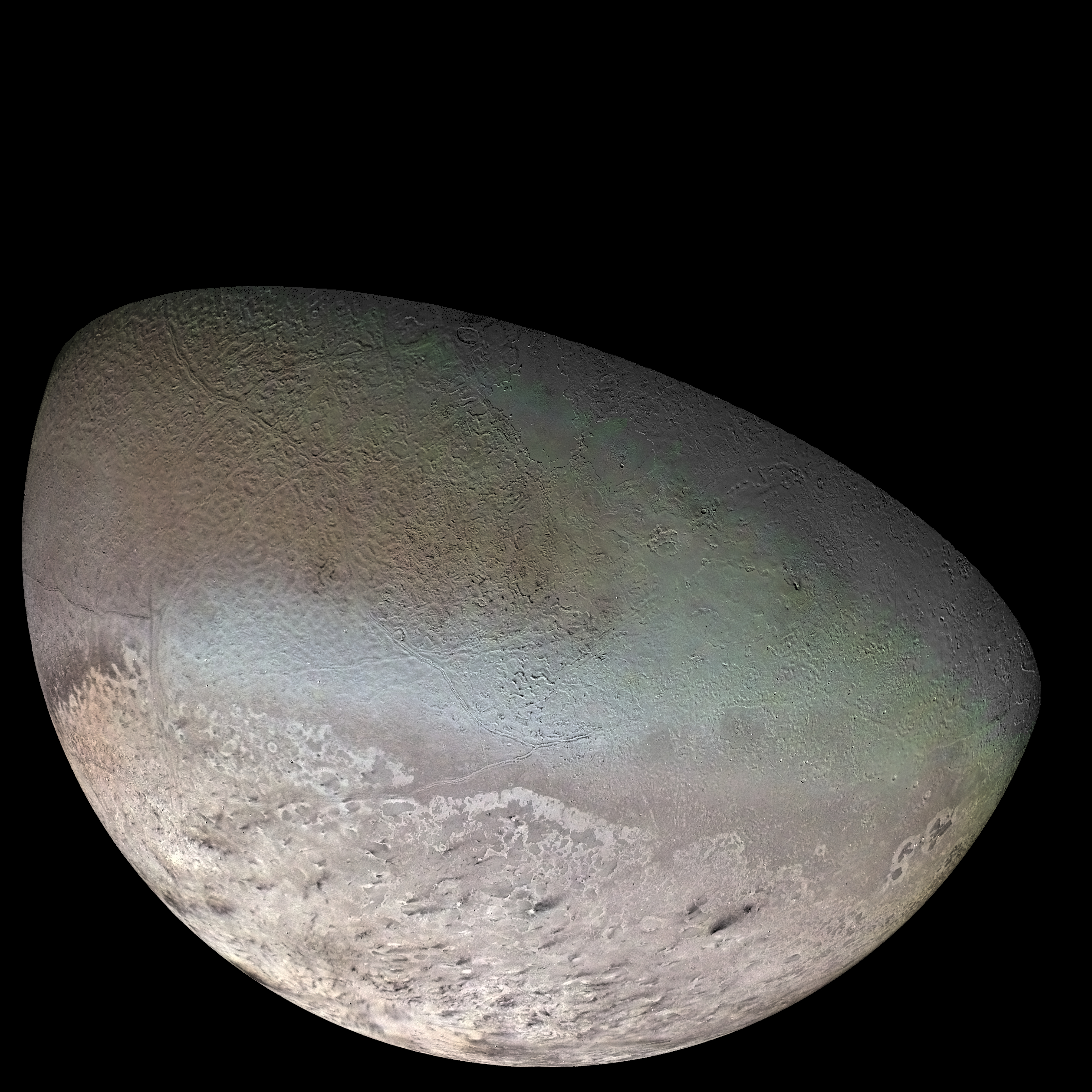

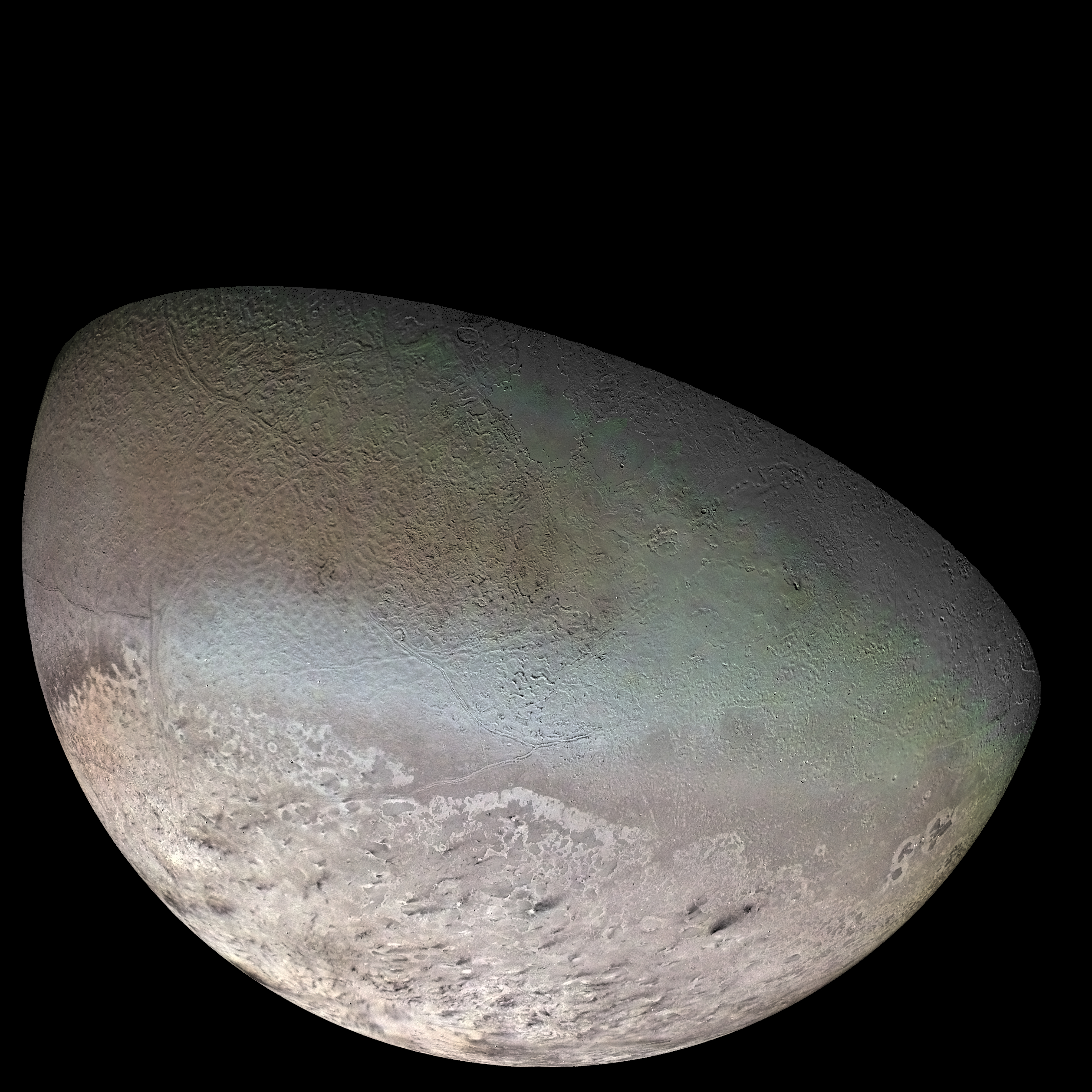

Neptune has 14 known

Neptune has 14 known

From July to September 1989, ''Voyager 2'' discovered six moons of Neptune. Of these, the irregularly shaped

From July to September 1989, ''Voyager 2'' discovered six moons of Neptune. Of these, the irregularly shaped

Neptune has a

Neptune has a

Neptune brightened about 10% between 1980 and 2000 mostly due to the changing of the seasons. Neptune may continue to brighten as it approaches perihelion in 2042. The

Neptune brightened about 10% between 1980 and 2000 mostly due to the changing of the seasons. Neptune may continue to brighten as it approaches perihelion in 2042. The

''

''

NASA's Neptune fact sheet

from Bill Arnett's nineplanets.org

Neptune

Neptune Profile

a

NASA's Solar System Exploration site

Interactive 3D gravity simulation of Neptune and its inner moons

{{Authority control Neptune 18460923 Gas giants Ice giants Outer planets

planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

from the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

and the farthest known planet in the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet

The giant planets constitute a diverse type of planet much larger than Earth. They are usually primarily composed of low-boiling-point materials (volatiles), rather than rock or other solid matter, but massive solid planets can also exist. Ther ...

. It is 17 times the mass of Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, and slightly more massive than its near-twin Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars (mythology), Mars), grandfather ...

. Neptune is denser and physically smaller than Uranus because its greater mass causes more gravitational compression of its atmosphere. It is referred to as one of the solar system's two ice giant

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System: Uranus and Neptune.

In astrophysics and planetary science t ...

planets (the other one being Uranus). Being composed primarily of gases and liquids, it has no well-defined "solid surface". The planet orbits the Sun once every 164.8 years

A year or annus is the orbital period of a planetary body, for example, the Earth, moving in its orbit around the Sun. Due to the Earth's axial tilt, the course of a year sees the passing of the seasons, marked by change in weather, the hour ...

at an average distance of . It is named after the Roman god of the sea and has the astronomical symbol

Astronomical symbols are abstract pictorial symbols used to represent astronomical objects, theoretical constructs and observational events in European astronomy. The earliest forms of these symbols appear in Greek papyrus texts of late antiq ...

trident

A trident is a three- pronged spear. It is used for spear fishing and historically as a polearm.

The trident is the weapon of Poseidon, or Neptune, the God of the Sea in classical mythology. The trident may occasionally be held by other marine ...

.

Neptune is not visible to the unaided eye and is the only planet in the Solar System found by mathematical prediction rather than by empirical observation

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

. Unexpected changes in the orbit of Uranus led Alexis Bouvard

Alexis Bouvard (, 27 June 1767 – 7 June 1843) was a French astronomer. He is particularly noted for his careful observations of the irregularities in the motion of Uranus and his hypothesis of the existence of an eighth planet in the Solar ...

to hypothesise that its orbit was subject to gravitational perturbation

Perturbation or perturb may refer to:

* Perturbation theory, mathematical methods that give approximate solutions to problems that cannot be solved exactly

* Perturbation (geology), changes in the nature of alluvial deposits over time

* Perturbatio ...

by an unknown planet. After Bouvard's death, the position of Neptune was predicted from his observations, independently, by John Couch Adams

John Couch Adams (; 5 June 1819 – 21 January 1892) was a British mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge.

His most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position of ...

and Urbain Le Verrier

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier FRS (FOR) HFRSE (; 11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French astronomer and mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for predicting the existence and position of Neptune using ...

. Neptune was subsequently observed with a telescope on 23 September 1846 by Johann Galle

Johann Gottfried Galle (9 June 1812 – 10 July 1910) was a German astronomer from Radis, Germany, at the Berlin Observatory who, on 23 September 1846, with the assistance of student Heinrich Louis d'Arrest, was the first person to view the pl ...

within a degree

Degree may refer to:

As a unit of measurement

* Degree (angle), a unit of angle measurement

** Degree of geographical latitude

** Degree of geographical longitude

* Degree symbol (°), a notation used in science, engineering, and mathematics

...

of the position predicted by Le Verrier. Its largest moon, Triton

Triton commonly refers to:

* Triton (mythology), a Greek god

* Triton (moon), a satellite of Neptune

Triton may also refer to:

Biology

* Triton cockatoo, a parrot

* Triton (gastropod), a group of sea snails

* ''Triton'', a synonym of ''Triturus' ...

, was discovered shortly thereafter, though none of the planet's remaining 13 known moons

A natural satellite is, in the most common usage, an astronomical body that orbits a planet, dwarf planet, or small Solar System body (or sometimes another natural satellite). Natural satellites are often colloquially referred to as ''moons'' ...

were located telescopically until the 20th century. The planet's distance from Earth gives it a very small apparent size, making it challenging to study with Earth-based telescopes. Neptune was visited by ''Voyager 2

''Voyager 2'' is a space probe launched by NASA on August 20, 1977, to study the outer planets and interstellar space beyond the Sun's heliosphere. As a part of the Voyager program, it was launched 16 days before its twin, ''Voyager 1'', on a ...

'', when it flew by the planet on 25 August 1989; ''Voyager 2'' remains the only spacecraft to have visited Neptune. The advent of the Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope (often referred to as HST or Hubble) is a space telescope that was launched into low Earth orbit in 1990 and remains in operation. It was not the first space telescope, but it is one of the largest and most versa ...

and large ground-based telescope

The following are lists of devices categorized as types of telescopes or devices associated with telescopes. They are broken into major classifications with many variations due to professional, amateur, and commercial sub-types. Telescopes can be ...

s with adaptive optics

Adaptive optics (AO) is a technology used to improve the performance of optical systems by reducing the effect of incoming wavefront distortions by deforming a mirror in order to compensate for the distortion. It is used in astronomical tele ...

has recently allowed for additional detailed observations from afar.

Like Jupiter and Saturn, Neptune's atmosphere is composed primarily of hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

and helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

, along with traces of hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic, and their odors are usually weak or ex ...

s and possibly nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at se ...

, though it contains a higher proportion of '' ices'' such as water, ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

and methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Eart ...

. However, similar to Uranus, its interior is primarily composed of ''ices'' and ''rock''; Uranus and Neptune are normally considered "ice giant

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System: Uranus and Neptune.

In astrophysics and planetary science t ...

s" to emphasise this distinction. Along with Rayleigh scattering

Rayleigh scattering ( ), named after the 19th-century British physicist Lord Rayleigh (John William Strutt), is the predominantly elastic scattering of light or other electromagnetic radiation by particles much smaller than the wavelength of the ...

, traces of methane in the outermost regions in part account for the planet's blue appearance. Newest data from the Gemini observatory

The Gemini Observatory is an astronomical observatory consisting of two 8.1-metre (26.6 ft) telescopes, Gemini North and Gemini South, which are located at two separate sites in Hawaii and Chile, respectively. The twin Gemini telescopes prov ...

shows the blue color is more saturated than the one present on Uranus due to thinner haze of Neptune's more active atmosphere.

In contrast to the hazy, relatively featureless atmosphere of Uranus, Neptune's atmosphere has active and visible weather patterns. For example, at the time of the ''Voyager 2'' flyby in 1989, the planet's southern hemisphere had a Great Dark Spot

The Great Dark Spot (also known as GDS-89, for Great Dark Spot, 1989) was one of a series of dark spots on Neptune similar in appearance to Jupiter's Great Red Spot. In 1989, GDS-89 was the first Great Dark Spot on Neptune to be observed by NASA ...

comparable to the Great Red Spot

The Great Red Spot is a persistent high-pressure region in the atmosphere of Jupiter, producing an anticyclonic storm that is the largest in the Solar System. Located 22 degrees south of Jupiter's equator, it produces wind-speeds up to 432 ...

on Jupiter. More recently, in 2018, a newer main dark spot and smaller dark spot were identified and studied. In addition, these weather patterns are driven by the strongest sustained winds of any planet in the Solar System, with recorded wind speeds as high as . Because of its great distance from the Sun, Neptune's outer atmosphere is one of the coldest places in the Solar System, with temperatures at its cloud tops approaching . Temperatures at the planet's centre are approximately . Neptune has a faint and fragmented ring system

A ring system is a disc or ring, orbiting an astronomical object, that is composed of solid material such as dust and moonlets, and is a common component of satellite systems around giant planets. A ring system around a planet is also known as ...

(labelled "arcs"), which was discovered in 1984, then later confirmed by ''Voyager 2''.

History

Discovery

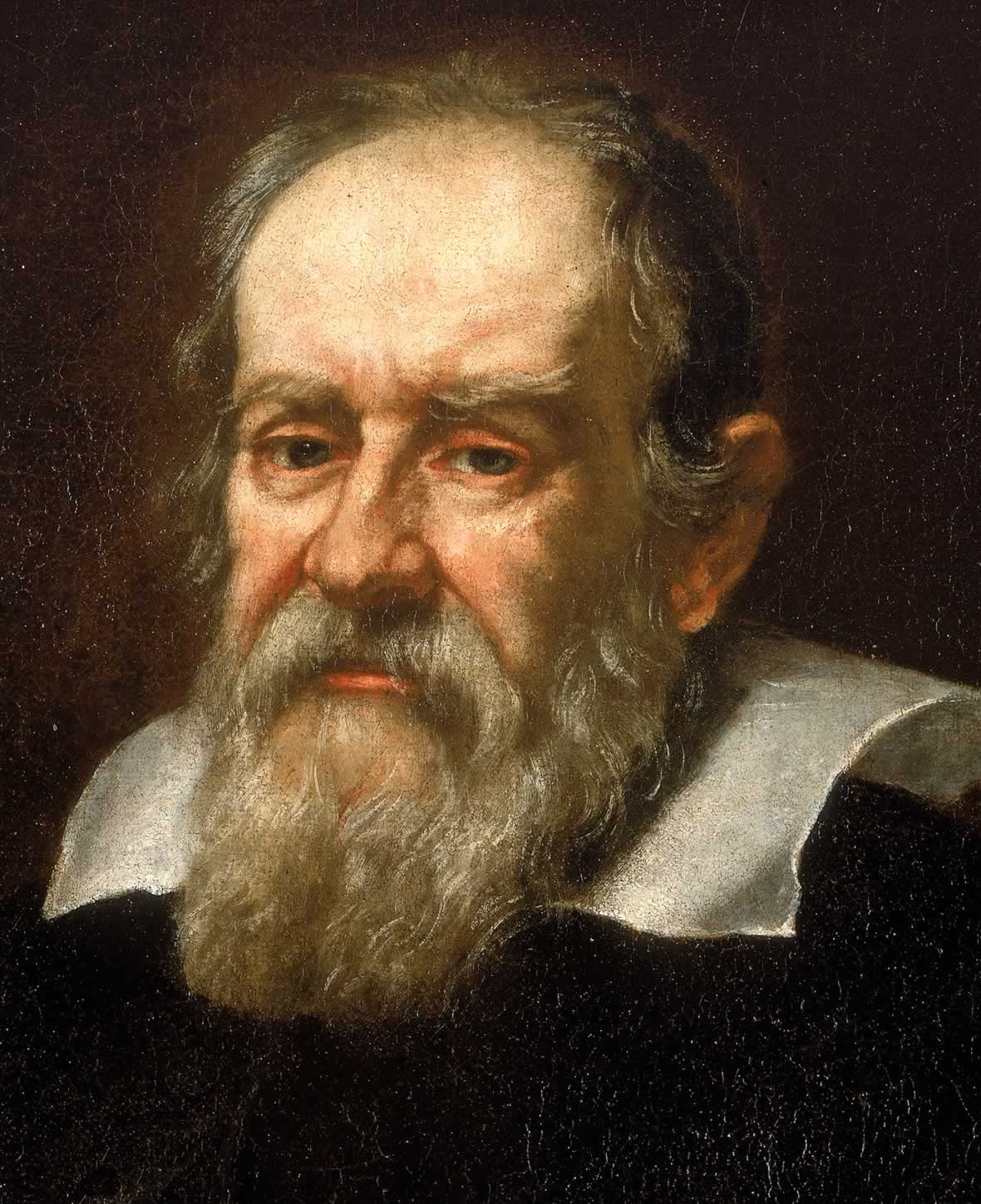

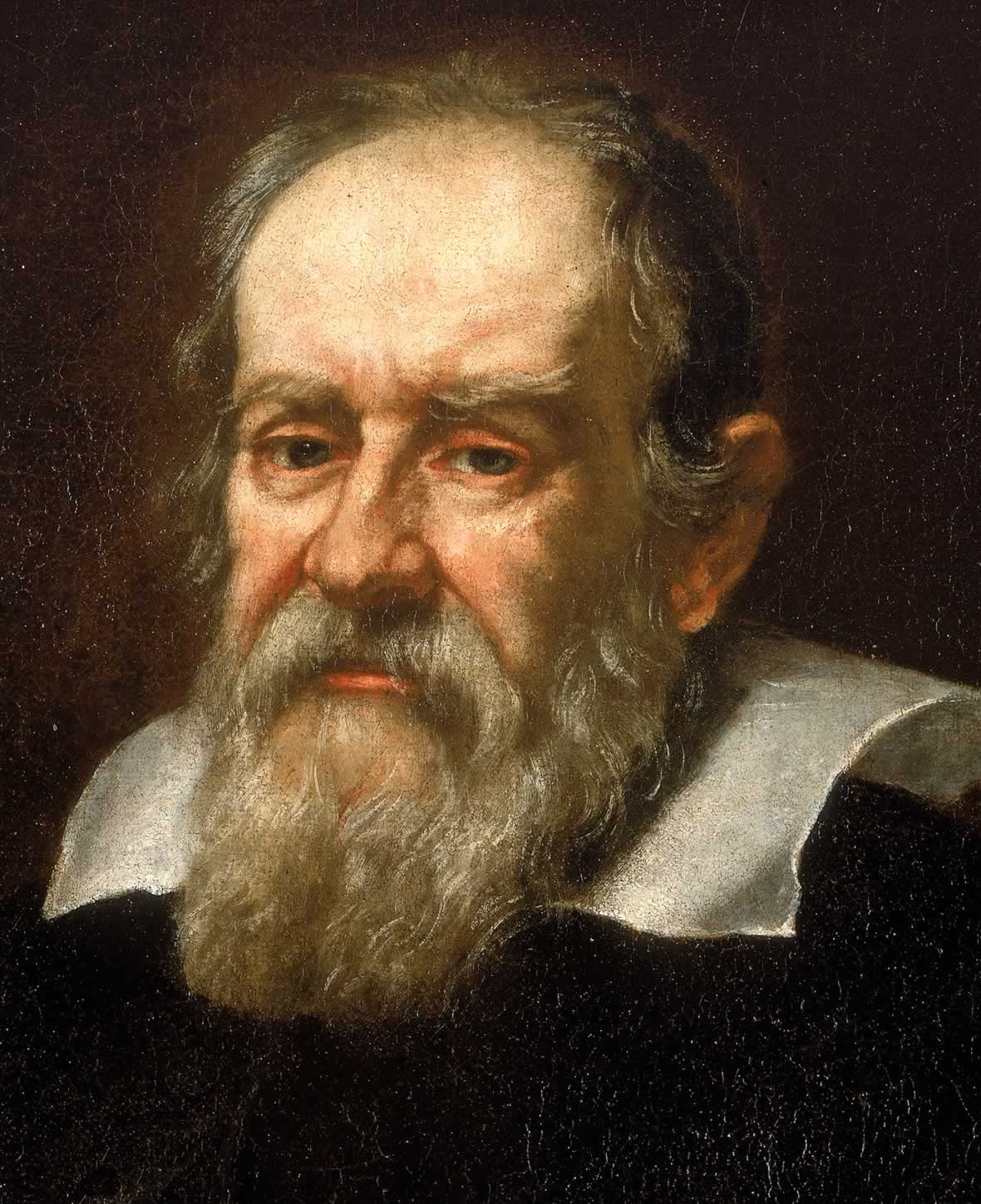

Some of the earliest recorded observations ever made through a

Some of the earliest recorded observations ever made through a telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, absorption, or reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally meaning only an optical instrument using lenses, curved mirrors, or a combination of both to observe ...

, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

's drawings on 28 December 1612 and 27 January 1613 contain plotted points that match up with what is now known to have been the positions of Neptune on those dates. On both occasions, Galileo seems to have mistaken Neptune for a fixed star

In astronomy, fixed stars ( la, stellae fixae) is a term to name the full set of glowing points, astronomical objects actually and mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the backg ...

when it appeared close—in conjunction

Conjunction may refer to:

* Conjunction (grammar), a part of speech

* Logical conjunction, a mathematical operator

** Conjunction introduction, a rule of inference of propositional logic

* Conjunction (astronomy), in which two astronomical bodies ...

—to Jupiter in the night sky

The night sky is the nighttime appearance of celestial objects like stars, planets, and the Moon, which are visible in a clear sky between sunset and sunrise, when the Sun is below the horizon.

Natural light sources in a night sky include ...

. Hence, he is not credited with Neptune's discovery. At his first observation in December 1612, Neptune was almost stationary in the sky because it had just turned retrograde that day. This apparent backward motion is created when Earth's orbit takes it past an outer planet. Because Neptune was only beginning its yearly retrograde cycle, the motion of the planet was far too slight to be detected with Galileo's small telescope. In 2009, a study suggested that Galileo was at least aware that the "star" he had observed had moved relative to the fixed stars

In astronomy, fixed stars ( la, stellae fixae) is a term to name the full set of glowing points, astronomical objects actually and mainly stars, that appear not to move relative to one another against the darkness of the night sky in the backgro ...

.

In 1821, Alexis Bouvard

Alexis Bouvard (, 27 June 1767 – 7 June 1843) was a French astronomer. He is particularly noted for his careful observations of the irregularities in the motion of Uranus and his hypothesis of the existence of an eighth planet in the Solar ...

published astronomical tables of the orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a p ...

of Neptune's neighbour Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars (mythology), Mars), grandfather ...

. Subsequent observations revealed substantial deviations from the tables, leading Bouvard to hypothesise that an unknown body was perturbing the orbit through gravitation

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stron ...

al interaction. In 1843, John Couch Adams

John Couch Adams (; 5 June 1819 – 21 January 1892) was a British mathematician and astronomer. He was born in Laneast, near Launceston, Cornwall, and died in Cambridge.

His most famous achievement was predicting the existence and position of ...

began work on the orbit of Uranus using the data he had. He requested extra data from Sir George Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English mathematician and astronomer, and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planetary orbits, measuring the mean density of the E ...

, the Astronomer Royal

Astronomer Royal is a senior post in the Royal Households of the United Kingdom. There are two officers, the senior being the Astronomer Royal dating from 22 June 1675; the junior is the Astronomer Royal for Scotland dating from 1834.

The post ...

, who supplied it in February 1844. Adams continued to work in 1845–1846 and produced several different estimates of a new planet.

In 1845–1846,

In 1845–1846, Urbain Le Verrier

Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier FRS (FOR) HFRSE (; 11 March 1811 – 23 September 1877) was a French astronomer and mathematician who specialized in celestial mechanics and is best known for predicting the existence and position of Neptune using ...

, independently of Adams, developed his own calculations but aroused no enthusiasm in his compatriots. In June 1846, upon seeing Le Verrier's first published estimate of the planet's longitude and its similarity to Adams's estimate, Airy persuaded James Challis

James Challis FRS (12 December 1803 – 3 December 1882) was an English clergyman, physicist and astronomer. Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy and the director of the Cambridge Observatory, he investigated a wide ra ...

to search for the planet. Challis vainly scoured the sky throughout August and September. Challis had, in fact, observed Neptune a year before the planet's subsequent discoverer, Johann Gottfried Galle

Johann Gottfried Galle (9 June 1812 – 10 July 1910) was a German astronomer from Radis, Germany, at the Berlin Observatory who, on 23 September 1846, with the assistance of student Heinrich Louis d'Arrest, was the first person to view the pl ...

, and on two occasions, 4 and 12 August 1845. However, his out-of-date star maps and poor observing techniques meant that he failed to recognise the observations as such until he carried out later analysis. Challis was full of remorse but blamed his neglect on his maps and the fact that he was distracted by his concurrent work on comet observations.

Meanwhile, Le Verrier sent a letter and urged Berlin Observatory

The Berlin Observatory (Berliner Sternwarte) is a German astronomical institution with a series of observatories and related organizations in and around the city of Berlin in Germany, starting from the 18th century. It has its origins in 1700 w ...

astronomer Galle to search with the observatory's refractor

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens (optics), lens as its objective (optics), objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptrics, dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope d ...

. Heinrich d'Arrest

Heinrich Louis d'Arrest (13 August 1822 – 14 June 1875; ) was a Germans, German astronomer, born in Berlin. His name is sometimes given as Heinrich Ludwig d'Arrest.

Biography

While still a student at the Humboldt University of Berli ...

, a student at the observatory, suggested to Galle that they could compare a recently drawn chart of the sky in the region of Le Verrier's predicted location with the current sky to seek the displacement characteristic of a planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

, as opposed to a fixed star. On the evening of 23 September 1846, the day Galle received the letter, he discovered Neptune just northeast of Iota Aquarii

Iota Aquarii, Latinised from ι Aquarii, is the Bayer designation for a binary star system in the equatorial constellation of Aquarius. It is visible to the naked eye with an apparent magnitude of +4.279. Based upon parallax measurements ...

, 1° from the "''five degrees east of Delta Capricorn''" position Le Verrier had predicted it to be, about 12° from Adams's prediction, and on the border of Aquarius and Capricornus according to the modern IAU constellation boundaries.

In the wake of the discovery, there was a heated nationalistic rivalry between the French and the British over who deserved credit for the discovery. Eventually, an international consensus emerged that Le Verrier and Adams deserved joint credit. Since 1966, Dennis Rawlins

Dennis Rawlins (born 1937) is an American astronomer and historian who has acquired the reputation of skeptic primarily with respect to historical claims connected to astronomical considerations. He is known to the public mostly from media cover ...

has questioned the credibility of Adams's claim to co-discovery, and the issue was re-evaluated by historians with the return in 1998 of the "Neptune papers" (historical documents) to the Royal Observatory, Greenwich

The Royal Observatory, Greenwich (ROG; known as the Old Royal Observatory from 1957 to 1998, when the working Royal Greenwich Observatory, RGO, temporarily moved south from Greenwich to Herstmonceux) is an observatory situated on a hill in ...

.

Naming

Shortly after its discovery, Neptune was referred to simply as "the planet exterior to Uranus" or as "Le Verrier's planet". The first suggestion for a name came from Galle, who proposed the name ''Janus

In ancient Roman religion and myth, Janus ( ; la, Ianvs ) is the god of beginnings, gates, transitions, time, duality, doorways, passages, frames, and endings. He is usually depicted as having two faces. The month of January is named for Janu ...

''. In England, Challis put forward the name ''Oceanus

In Greek mythology, Oceanus (; grc-gre, , Ancient Greek pronunciation: , also Ὠγενός , Ὤγενος , or Ὠγήν ) was a Titan son of Uranus and Gaia, the husband of his sister the Titan Tethys, and the father of the river gods a ...

''.

Claiming the right to name his discovery, Le Verrier quickly proposed the name ''Neptune'' for this new planet, though falsely stating that this had been officially approved by the French Bureau des Longitudes

Bureau ( ) may refer to:

Agencies and organizations

*Government agency

*Public administration

* News bureau, an office for gathering or distributing news, generally for a given geographical location

* Bureau (European Parliament), the administrat ...

. In October, he sought to name the planet ''Le Verrier'', after himself, and he had loyal support in this from the observatory director, François Arago

Dominique François Jean Arago ( ca, Domènec Francesc Joan Aragó), known simply as François Arago (; Catalan: ''Francesc Aragó'', ; 26 February 17862 October 1853), was a French mathematician, physicist, astronomer, freemason, supporter of t ...

. This suggestion met with stiff resistance outside France. French almanacs quickly reintroduced the name ''Herschel'' for Uranus, after that planet's discoverer Sir William Herschel

Frederick William Herschel (; german: Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel; 15 November 1738 – 25 August 1822) was a German-born British astronomer and composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline H ...

, and ''Leverrier'' for the new planet.

Struve came out in favour of the name ''Neptune'' on 29 December 1846, to the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across t ...

. Soon, ''Neptune'' became the internationally accepted name. In Roman mythology

Roman mythology is the body of myths of ancient Rome as represented in the literature and visual arts of the Romans. One of a wide variety of genres of Roman folklore, ''Roman mythology'' may also refer to the modern study of these representat ...

, Neptune

Neptune is the eighth planet from the Sun and the farthest known planet in the Solar System. It is the fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 times ...

was the god of the sea, identified with the Greek Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

. The demand for a mythological name seemed to be in keeping with the nomenclature of the other planets, all of which were named for deities in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

and Roman mythology.

Most languages today use some variant of the name "Neptune" for the planet; indeed, in Chinese, Vietnamese, Japanese, and Korean, the planet's name was translated as "sea king star" (). In Mongolian, Neptune is called (), reflecting its namesake god's role as the ruler of the sea. In modern Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

the planet is called ''Poseidon'' (, ), the Greek counterpart of Neptune. In Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, (), from a Biblical sea monster mentioned in the Book of Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived f ...

, was selected in a vote managed by the Academy of the Hebrew Language

The Academy of the Hebrew Language ( he, הָאָקָדֶמְיָה לַלָּשׁוֹן הָעִבְרִית, ''ha-akademyah la-lashon ha-ivrit'') was established by the Israeli government in 1953 as the "supreme institution for scholarship on t ...

in 2009 as the official name for the planet, even though the existing Latin term () is commonly used. In Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

, the planet is called , named after the Māori god of the sea."Appendix 5: Planetary Linguistics", Nineplanets.org In

Nahuatl

Nahuatl (; ), Aztec, or Mexicano is a language or, by some definitions, a group of languages of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Varieties of Nahuatl are spoken by about Nahua peoples, most of whom live mainly in Central Mexico and have smaller ...

, the planet is called , named after the rain god Tlāloc

Tlaloc ( nci-IPA, Tlāloc, ˈtɬaːlok) is a deity in Aztec religion. The supreme god of the rain, Tlaloc is also a god of earthly fertility and of water. He was widely worshipped as a beneficent giver of life and sustenance, as well as feared f ...

. In Thai

Thai or THAI may refer to:

* Of or from Thailand, a country in Southeast Asia

** Thai people, the dominant ethnic group of Thailand

** Thai language, a Tai-Kadai language spoken mainly in and around Thailand

*** Thai script

*** Thai (Unicode block ...

, Neptune is referred to by its Westernised name (), but is also called (, ), after Ketu

KETU (1120 AM) is a radio station licensed to serve Catoosa, Oklahoma. The station is owned by Antonio Perez, through licensee Radio Las Americas Arkansas, LLC.

The station was licensed originally to Atoka, Oklahoma, and operated for many years ...

(), the descending lunar node

A lunar node is either of the two orbital nodes of the Moon, that is, the two points at which the orbit of the Moon intersects the ecliptic. The ''ascending'' (or ''north'') node is where the Moon moves into the northern ecliptic hemisphere, w ...

, who plays a role in Hindu astrology

Jyotisha or Jyotishya (from Sanskrit ', from ' “light, heavenly body" and ''ish'' - from Isvara or God) is the traditional Hindu system of astrology, also known as Hindu astrology, Indian astrology and more recently Vedic astrology. It is one ...

. In Malay

Malay may refer to:

Languages

* Malay language or Bahasa Melayu, a major Austronesian language spoken in Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore

** History of the Malay language, the Malay language from the 4th to the 14th century

** Indonesi ...

, the name , after the Hindu god of seas, is attested as far back as the 1970s, but was eventually superseded by the Latinate equivalents (in Malaysian

Malaysian may refer to:

* Something from or related to Malaysia, a country in Southeast Asia

* Malaysian Malay, a dialect of Malay language spoken mainly in Malaysia

* Malaysian people, people who are identified with the country of Malaysia regard ...

) or (in Indonesian

Indonesian is anything of, from, or related to Indonesia, an archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. It may refer to:

* Indonesians, citizens of Indonesia

** Native Indonesians, diverse groups of local inhabitants of the archipelago

** Indonesian ...

).

The usual adjectival form is ''Neptunian''. The nonce form ''Poseidean'' (), from Poseidon

Poseidon (; grc-gre, Ποσειδῶν) was one of the Twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and myth, god of the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 In pre-Olympian Bronze Age Greece, he was venerated as a ch ...

, has also been used, though the usual adjectival form of Poseidon is ''Poseidonian'' ().

Status

From its discovery in 1846 until thediscovery of Pluto

Following the discovery of the planet Neptune in 1846, there was considerable speculation that another planet might exist beyond its orbit. The search began in the mid-19th century and continued at the start of the 20th with Percival Lowell's ...

in 1930, Neptune was the farthest known planet. When Pluto was discovered, it was considered a planet, and Neptune thus became the second-farthest known planet, except for a 20-year period between 1979 and 1999 when Pluto's elliptical orbit brought it closer than Neptune to the Sun. The increasingly accurate estimations of Pluto's mass from ten times that of Earth's to far less than that of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

and the discovery of the Kuiper belt

The Kuiper belt () is a circumstellar disc in the outer Solar System, extending from the orbit of Neptune at 30 astronomical units (AU) to approximately 50 AU from the Sun. It is similar to the asteroid belt, but is far larger—20 times ...

in 1992 led many astronomers to debate whether Pluto should be considered a planet or as part of the Kuiper belt. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; french: link=yes, Union astronomique internationale, UAI) is a nongovernmental organisation with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreac ...

defined the word "planet" for the first time, reclassifying Pluto as a "dwarf planet

A dwarf planet is a small planetary-mass object that is in direct orbit of the Sun, smaller than any of the eight classical planets but still a world in its own right. The prototypical dwarf planet is Pluto. The interest of dwarf planets to p ...

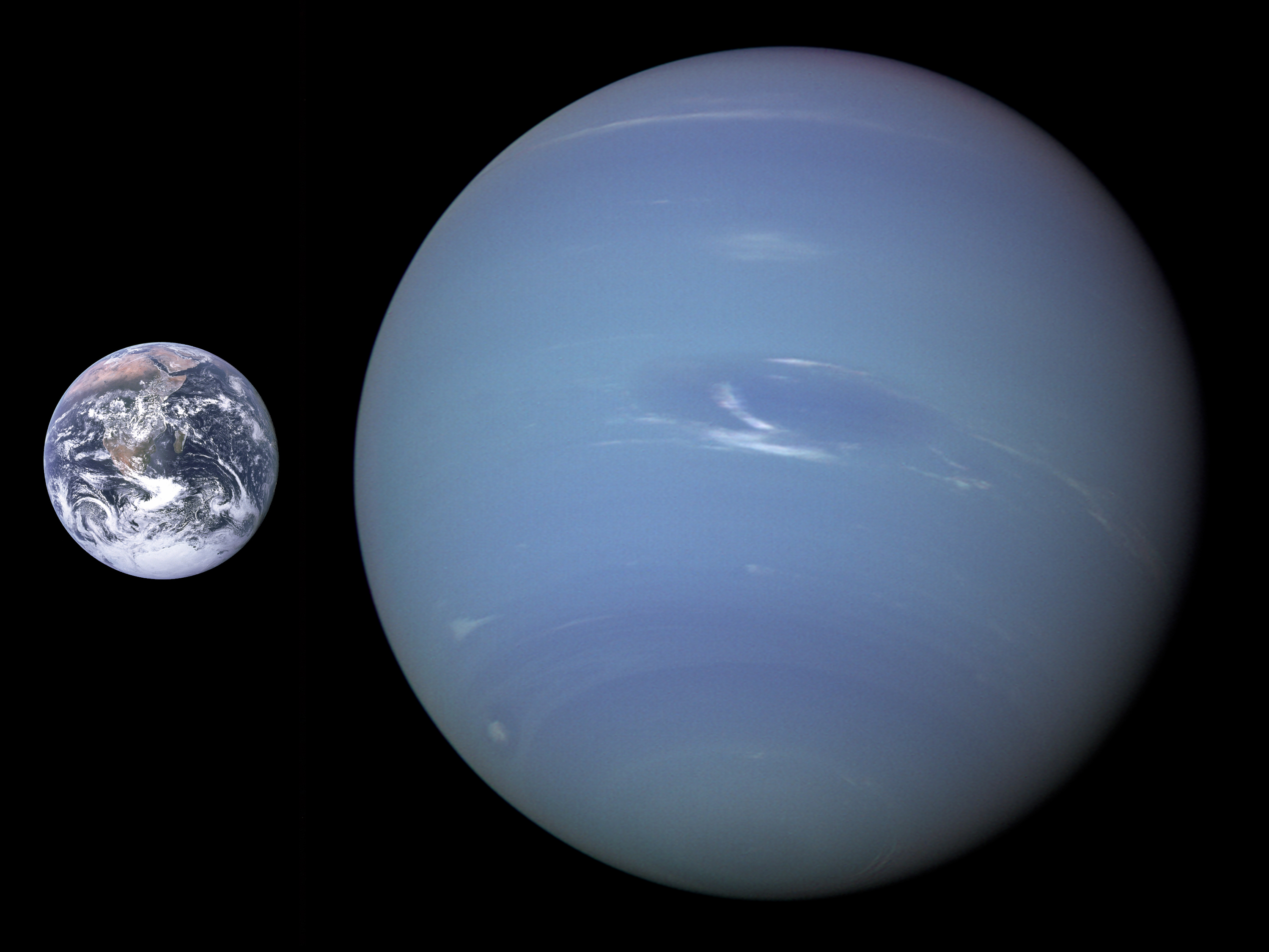

" and making Neptune once again the outermost-known planet in the Solar System.

Physical characteristics

Neptune's mass of 1.0243 kg is intermediate between Earth and the larger

Neptune's mass of 1.0243 kg is intermediate between Earth and the larger gas giant

A gas giant is a giant planet composed mainly of hydrogen and helium. Gas giants are also called failed stars because they contain the same basic elements as a star. Jupiter and Saturn are the gas giants of the Solar System. The term "gas giant" ...

s: it is 17 times that of Earth but just 1/19th that of Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

.The mass of Earth is 5.9736 kg, giving a mass ratio

:

The mass of Uranus is 8.6810 kg, giving a mass ratio

:

The mass of Jupiter is 1.8986 kg, giving a mass ratio

:

Mass values from Its gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

at 1 bar is 11.15 m/s2, 1.14 times the surface gravity

The surface gravity, ''g'', of an astronomical object is the gravitational acceleration experienced at its surface at the equator, including the effects of rotation. The surface gravity may be thought of as the acceleration due to gravity experien ...

of Earth, and surpassed only by Jupiter. Neptune's equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

ial radius of 24,764 km is nearly four times that of Earth. Neptune, like Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars (mythology), Mars), grandfather ...

, is an ice giant

An ice giant is a giant planet composed mainly of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur. There are two ice giants in the Solar System: Uranus and Neptune.

In astrophysics and planetary science t ...

, a subclass of giant planet

The giant planets constitute a diverse type of planet much larger than Earth. They are usually primarily composed of low-boiling-point materials (volatiles), rather than rock or other solid matter, but massive solid planets can also exist. Ther ...

, because they are smaller and have higher concentrations of volatiles

Volatiles are the group of chemical elements and chemical compounds that can be readily vaporized. In contrast with volatiles, elements and compounds that are not readily vaporized are known as refractory substances.

On planet Earth, the term ' ...

than Jupiter and Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

. In the search for exoplanet

An exoplanet or extrasolar planet is a planet outside the Solar System. The first possible evidence of an exoplanet was noted in 1917 but was not recognized as such. The first confirmation of detection occurred in 1992. A different planet, init ...

s, Neptune has been used as a metonym

Metonymy () is a figure of speech in which a concept is referred to by the name of something closely associated with that thing or concept.

Etymology

The words ''metonymy'' and ''metonym'' come from grc, μετωνυμία, 'a change of name' ...

: discovered bodies of similar mass are often referred to as "Neptunes", just as scientists refer to various extrasolar bodies as "Jupiters".

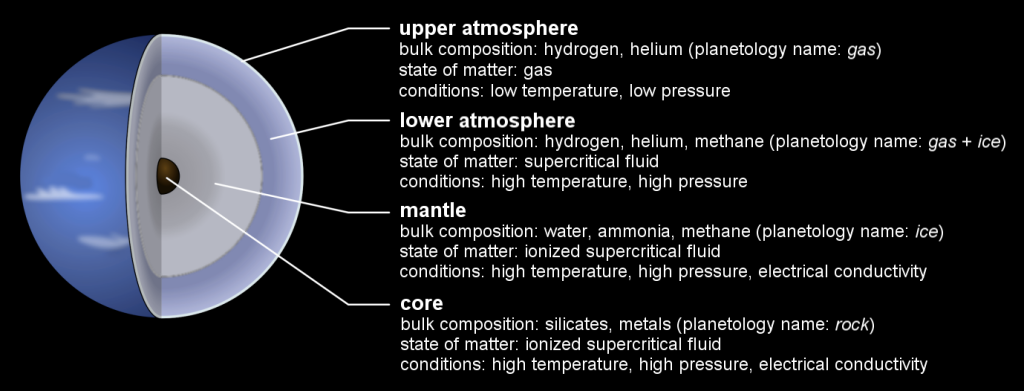

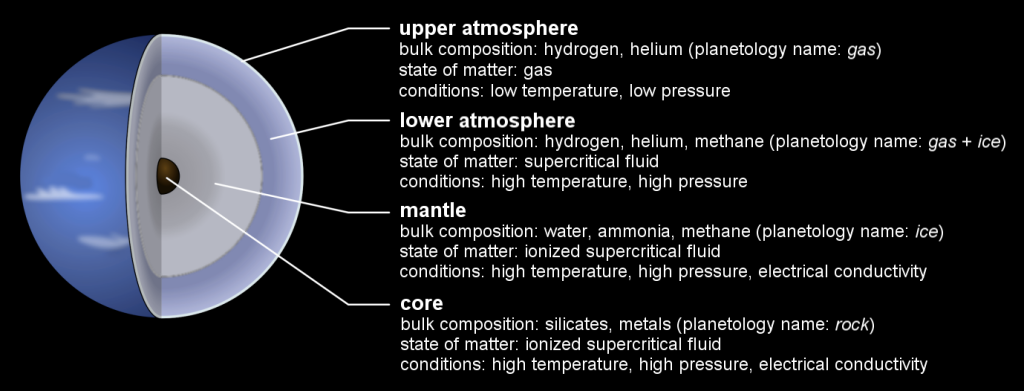

Internal structure

Neptune's internal structure resembles that ofUranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars (mythology), Mars), grandfather ...

. Its atmosphere forms about 5 to 10% of its mass and extends perhaps 10 to 20% of the way towards the core, where it reaches pressures of about 10 GPa

Grading in education is the process of applying standardized measurements for varying levels of achievements in a course. Grades can be assigned as letters (usually A through F), as a range (for example, 1 to 6), as a percentage, or as a numbe ...

, or about 100,000 times that of Earth's atmosphere. Increasing concentrations of methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Eart ...

, ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

and water are found in the lower regions of the atmosphere.

The mantle is equivalent to 10 to 15 Earth masses and is rich in water, ammonia and methane. As is customary in planetary science, this mixture is referred to as

The mantle is equivalent to 10 to 15 Earth masses and is rich in water, ammonia and methane. As is customary in planetary science, this mixture is referred to as icy Icy commonly refers to conditions involving ice, a frozen state, usually referring to frozen water.

Icy or Icey may also refer to:

People

* Icy Spicy Leoncie, an Icelandic-Indian musician

Arts, entertainment, and media Music

* ICY (band), a vocal ...

even though it is a hot, dense fluid (supercritical fluid

A supercritical fluid (SCF) is any substance at a temperature and pressure above its critical point, where distinct liquid and gas phases do not exist, but below the pressure required to compress it into a solid. It can effuse through porous so ...

). This fluid, which has a high electrical conductivity, is sometimes called a water–ammonia ocean. The mantle may consist of a layer of ionic water in which the water molecules break down into a soup of hydrogen and oxygen ions, and deeper down superionic water

Superionic water, also called superionic ice or ice XVIII is a phase of water that exists at extremely high temperatures and pressures. In superionic water, water molecules break apart and the oxygen ions crystallize into an evenly spaced latti ...

in which the oxygen crystallises but the hydrogen ion

A hydrogen ion is created when a hydrogen atom loses or gains an electron. A positively charged hydrogen ion (or proton) can readily combine with other particles and therefore is only seen isolated when it is in a gaseous state or a nearly particle ...

s float around freely within the oxygen lattice. At a depth of 7,000 km, the conditions may be such that methane decomposes into diamond crystals that rain downwards like hailstones. Scientists also believe that this kind of diamond rain occurs on Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

, Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

, and Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars (mythology), Mars), grandfather ...

. Very-high-pressure experiments at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) is a federal research facility in Livermore, California, United States. The lab was originally established as the University of California Radiation Laboratory, Livermore Branch in 1952 in response ...

suggest that the top of the mantle may be an ocean of liquid carbon with floating solid 'diamonds'.

The core

Core or cores may refer to:

Science and technology

* Core (anatomy), everything except the appendages

* Core (manufacturing), used in casting and molding

* Core (optical fiber), the signal-carrying portion of an optical fiber

* Core, the central ...

of Neptune is likely composed of iron, nickel and silicate

In chemistry, a silicate is any member of a family of polyatomic anions consisting of silicon and oxygen, usually with the general formula , where . The family includes orthosilicate (), metasilicate (), and pyrosilicate (, ). The name is al ...

s, with an interior model giving a mass about 1.2 times that of Earth. The pressure at the centre is 7 Mbar

The bar is a metric unit of pressure, but not part of the International System of Units (SI). It is defined as exactly equal to 100,000 Pa (100 kPa), or slightly less than the current average atmospheric pressure on Earth at sea leve ...

(700 GPa), about twice as high as that at the centre of Earth, and the temperature may be 5,400 K.

Atmosphere

At high altitudes, Neptune's atmosphere is 80%

At high altitudes, Neptune's atmosphere is 80% hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

and 19% helium

Helium (from el, ἥλιος, helios, lit=sun) is a chemical element with the symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. ...

. A trace amount of methane is also present. Prominent absorption bands of methane exist at wavelengths above 600 nm, in the red and infrared portion of the spectrum. As with Uranus, this absorption of red light by the atmospheric methane

Atmospheric methane is the methane present in Earth's atmosphere. Atmospheric methane concentrations are of interest because it is one of the most potent greenhouse gases in Earth's atmosphere. Atmospheric methane is rising.

The 20-year glob ...

is part of what gives Neptune its blue hue, although Neptune's blue differs from Uranus's milder light blue.

Neptune's atmosphere is subdivided into two main regions: the lower troposphere

The troposphere is the first and lowest layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, and contains 75% of the total mass of the planetary atmosphere, 99% of the total mass of water vapour and aerosols, and is where most weather phenomena occur. From ...

, where temperature decreases with altitude, and the stratosphere

The stratosphere () is the second layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, located above the troposphere and below the mesosphere. The stratosphere is an atmospheric layer composed of stratified temperature layers, with the warm layers of air ...

, where temperature increases with altitude. The boundary between the two, the tropopause

The tropopause is the atmospheric boundary that demarcates the troposphere from the stratosphere; which are two of the five layers of the atmosphere of Earth. The tropopause is a thermodynamic gradient-stratification layer, that marks the end of ...

, lies at a pressure of . The stratosphere then gives way to the thermosphere

The thermosphere is the layer in the Earth's atmosphere directly above the mesosphere and below the exosphere. Within this layer of the atmosphere, ultraviolet radiation causes photoionization/photodissociation of molecules, creating ions; the ...

at a pressure lower than 10−5 to 10−4 bars (1 to 10 Pa). The thermosphere gradually transitions to the exosphere

The exosphere ( grc, ἔξω "outside, external, beyond", grc, σφαῖρα "sphere") is a thin, atmosphere-like volume surrounding a planet or natural satellite where molecules are gravitationally bound to that body, but where the densit ...

.

Models suggest that Neptune's troposphere is banded by clouds of varying compositions depending on altitude. The upper-level clouds lie at pressures below one bar, where the temperature is suitable for methane to condense. For pressures between one and five bars (100 and 500 kPa), clouds of ammonia and

Models suggest that Neptune's troposphere is banded by clouds of varying compositions depending on altitude. The upper-level clouds lie at pressures below one bar, where the temperature is suitable for methane to condense. For pressures between one and five bars (100 and 500 kPa), clouds of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The unde ...

are thought to form. Above a pressure of five bars, the clouds may consist of ammonia, ammonium sulfide

Ammonium hydrosulfide is the chemical compound with the formula .

Composition

It is the salt derived from the ammonium cation and the hydrosulfide anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an e ...

, hydrogen sulfide and water. Deeper clouds of water ice should be found at pressures of about , where the temperature reaches . Underneath, clouds of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide may be found.

High-altitude clouds on Neptune have been observed casting shadows on the opaque cloud deck below. There are also high-altitude cloud bands that wrap around the planet at constant latitude. These circumferential bands have widths of 50–150 km and lie about 50–110 km above the cloud deck. These altitudes are in the layer where weather occurs, the troposphere. Weather does not occur in the higher stratosphere or thermosphere.

Neptune's spectra suggest that its lower stratosphere is hazy due to condensation of products of ultraviolet photolysis

Photodissociation, photolysis, photodecomposition, or photofragmentation is a chemical reaction in which molecules of a chemical compound are broken down by photons. It is defined as the interaction of one or more photons with one target molecule. ...

of methane, such as ethane

Ethane ( , ) is an organic chemical compound with chemical formula . At standard temperature and pressure, ethane is a colorless, odorless gas. Like many hydrocarbons, ethane is isolated on an industrial scale from natural gas and as a petr ...

and ethyne

Acetylene (systematic name: ethyne) is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in its pure ...

. The stratosphere is also home to trace amounts of carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the simple ...

and hydrogen cyanide

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure . It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at . HCN is produced on an ...

. The stratosphere of Neptune is warmer than that of Uranus due to the elevated concentration of hydrocarbons.

For reasons that remain obscure, the planet's thermosphere is at an anomalously high temperature of about 750 K. The planet is too far from the Sun for this heat to be generated by ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nanometer, nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 Hertz, PHz) to 400 nm (750 Hertz, THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than ...

radiation. One candidate for a heating mechanism is atmospheric interaction with ions in the planet's magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

. Other candidates are gravity wave

In fluid dynamics, gravity waves are waves generated in a fluid medium or at the interface between two media when the force of gravity or buoyancy tries to restore equilibrium. An example of such an interface is that between the atmosphere ...

s from the interior that dissipate in the atmosphere. The thermosphere contains traces of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

and water, which may have been deposited from external sources such as meteorite

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or Natural satellite, moon. When the ...

s and dust.

Magnetosphere

Neptune resembles Uranus in itsmagnetosphere

In astronomy and planetary science, a magnetosphere is a region of space surrounding an astronomical object in which charged particles are affected by that object's magnetic field. It is created by a celestial body with an active interior dynam ...

, with a magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

strongly tilted relative to its rotation

Rotation, or spin, is the circular movement of an object around a '' central axis''. A two-dimensional rotating object has only one possible central axis and can rotate in either a clockwise or counterclockwise direction. A three-dimensional ...

al axis at 47° and offset at least 0.55 radius, or about 13,500 km from the planet's physical centre. Before ''Voyager 2'' arrival at Neptune, it was hypothesised that Uranus's tilted magnetosphere was the result of its sideways rotation. In comparing the magnetic fields of the two planets, scientists now think the extreme orientation may be characteristic of flows in the planets' interiors. This field may be generated by convective

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the convect ...

fluid motions in a thin spherical shell of electrically conducting

Electrical resistivity (also called specific electrical resistance or volume resistivity) is a fundamental property of a material that measures how strongly it resists electric current. A low resistivity indicates a material that readily allows ...

liquids (probably a combination of ammonia, methane and water) resulting in a dynamo

file:DynamoElectricMachinesEndViewPartlySection USP284110.png, "Dynamo Electric Machine" (end view, partly section, )

A dynamo is an electrical generator that creates direct current using a commutator (electric), commutator. Dynamos were the f ...

action.

The dipole component of the magnetic field at the magnetic equator of Neptune is about 14 microteslas (0.14 G). The dipole magnetic moment

In electromagnetism, the magnetic moment is the magnetic strength and orientation of a magnet or other object that produces a magnetic field. Examples of objects that have magnetic moments include loops of electric current (such as electromagnets ...

of Neptune is about 2.2 T·m3 (14 μT·''R''''N''3, where ''R''''N'' is the radius of Neptune). Neptune's magnetic field has a complex geometry that includes relatively large contributions from non-dipolar components, including a strong quadrupole

A quadrupole or quadrapole is one of a sequence of configurations of things like electric charge or current, or gravitational mass that can exist in ideal form, but it is usually just part of a multipole expansion of a more complex structure refl ...

moment that may exceed the dipole moment in strength. By contrast, Earth, Jupiter and Saturn have only relatively small quadrupole moments, and their fields are less tilted from the polar axis. The large quadrupole moment of Neptune may be the result of offset from the planet's centre and geometrical constraints of the field's dynamo generator.

Neptune's bow shock

In astrophysics, a bow shock occurs when the magnetosphere of an astrophysical object interacts with the nearby flowing ambient plasma such as the solar wind. For Earth and other magnetized planets, it is the boundary at which the speed of ...

, where the magnetosphere begins to slow the solar wind

The solar wind is a stream of charged particles released from the upper atmosphere of the Sun, called the corona. This plasma mostly consists of electrons, protons and alpha particles with kinetic energy between . The composition of the sola ...

, occurs at a distance of 34.9 times the radius of the planet. The magnetopause

The magnetopause is the abrupt boundary between a magnetosphere and the surrounding plasma. For planetary science, the magnetopause is the boundary between the planet's magnetic field and the solar wind. The location of the magnetopause is d ...

, where the pressure of the magnetosphere counterbalances the solar wind, lies at a distance of 23–26.5 times the radius of Neptune. The tail of the magnetosphere extends out to at least 72 times the radius of Neptune, and likely much farther.

Climate

Neptune's weather is characterised by extremely dynamic storm systems, with winds reaching speeds of almost —nearly reaching

Neptune's weather is characterised by extremely dynamic storm systems, with winds reaching speeds of almost —nearly reaching supersonic

Supersonic speed is the speed of an object that exceeds the speed of sound ( Mach 1). For objects traveling in dry air of a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) at sea level, this speed is approximately . Speeds greater than five times ...

flow. More typically, by tracking the motion of persistent clouds, wind speeds have been shown to vary from 20 m/s in the easterly direction to 325 m/s westward. At the cloud tops, the prevailing winds range in speed from 400 m/s along the equator to 250 m/s at the poles. Most of the winds on Neptune move in a direction opposite the planet's rotation.Burgess __NOTOC__

Burgess may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Burgess (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Burgess (given name), a list of people

Places

* Burgess, Michigan, an unincorporated community

* Burgess, Missouri, U ...

(1991):64–70. The general pattern of winds showed prograde rotation at high latitudes vs. retrograde rotation at lower latitudes. The difference in flow direction is thought to be a "skin effect" and not due to any deeper atmospheric processes. At 70° S latitude, a high-speed jet travels at a speed of 300 m/s.

Neptune differs from Uranus in its typical level of meteorological activity. ''Voyager 2'' observed weather phenomena on Neptune during its 1989 flyby, but no comparable phenomena on Uranus during its 1986 fly-by.

The abundance of methane, ethane and acetylene

Acetylene (systematic name: ethyne) is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in its pure ...

at Neptune's equator is 10–100 times greater than at the poles. This is interpreted as evidence for upwelling at the equator and subsidence near the poles because photochemistry cannot account for the distribution without meridional circulation.

In 2007, it was discovered that the upper troposphere of Neptune's south pole was about 10 K warmer than the rest of its atmosphere, which averages approximately . The temperature differential is enough to let methane, which elsewhere is frozen in the troposphere, escape into the stratosphere near the pole. The relative "hot spot" is due to Neptune's axial tilt

In astronomy, axial tilt, also known as obliquity, is the angle between an object's rotational axis and its orbital axis, which is the line perpendicular to its orbital plane; equivalently, it is the angle between its equatorial plane and orbi ...

, which has exposed the south pole to the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

for the last quarter of Neptune's year, or roughly 40 Earth years. As Neptune slowly moves towards the opposite side of the Sun, the south pole will be darkened and the north pole illuminated, causing the methane release to shift to the north pole.

Because of seasonal changes, the cloud bands in the southern hemisphere of Neptune have been observed to increase in size and albedo

Albedo (; ) is the measure of the diffuse reflection of sunlight, solar radiation out of the total solar radiation and measured on a scale from 0, corresponding to a black body that absorbs all incident radiation, to 1, corresponding to a body ...

. This trend was first seen in 1980. The long orbital period of Neptune results in seasons lasting forty years.

Storms

In 1989, theGreat Dark Spot

The Great Dark Spot (also known as GDS-89, for Great Dark Spot, 1989) was one of a series of dark spots on Neptune similar in appearance to Jupiter's Great Red Spot. In 1989, GDS-89 was the first Great Dark Spot on Neptune to be observed by NASA ...

, an anticyclonic

An anticyclone is a weather phenomenon defined as a large-scale circulation of winds around a central region of high atmospheric pressure, clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from abov ...

storm system spanning was discovered by NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agency of the US federal government responsible for the civil space program, aeronautics research, and space research.

NASA was established in 1958, succeeding t ...

's ''Voyager 2'' spacecraft. The storm resembled the Great Red Spot

The Great Red Spot is a persistent high-pressure region in the atmosphere of Jupiter, producing an anticyclonic storm that is the largest in the Solar System. Located 22 degrees south of Jupiter's equator, it produces wind-speeds up to 432 ...

of Jupiter. Some five years later, on 2 November 1994, the Hubble Space Telescope

The Hubble Space Telescope (often referred to as HST or Hubble) is a space telescope that was launched into low Earth orbit in 1990 and remains in operation. It was not the first space telescope, but it is one of the largest and most versa ...

did not see the Great Dark Spot on the planet. Instead, a new storm similar to the Great Dark Spot was found in Neptune's northern hemisphere.

The is another storm, a white cloud group farther south than the Great Dark Spot. This nickname first arose during the months leading up to the ''Voyager 2'' encounter in 1989, when they were observed moving at speeds faster than the Great Dark Spot

The Great Dark Spot (also known as GDS-89, for Great Dark Spot, 1989) was one of a series of dark spots on Neptune similar in appearance to Jupiter's Great Red Spot. In 1989, GDS-89 was the first Great Dark Spot on Neptune to be observed by NASA ...

(and images acquired later would subsequently reveal the presence of clouds moving even faster than those that had initially been detected by ''Voyager 2''). The Small Dark Spot

The Small Dark Spot, sometimes also called Dark Spot 2 or The Wizard's Eye, was an Extraterrestrial Storms, extraterrestrial vortex on the planet Neptune. It was the second largest southern Cyclone, cyclonic storm on the planet in 1989, when ''V ...

is a southern cyclonic storm, the second-most-intense storm observed during the 1989 encounter. It was initially completely dark, but as ''Voyager 2'' approached the planet, a bright core developed and can be seen in most of the highest-resolution images. More recently, in 2018, a newer main dark spot and smaller dark spot were identified and studied.

Neptune's dark spots are thought to occur in the troposphere

The troposphere is the first and lowest layer of the atmosphere of the Earth, and contains 75% of the total mass of the planetary atmosphere, 99% of the total mass of water vapour and aerosols, and is where most weather phenomena occur. From ...

at lower altitudes than the brighter cloud features, so they appear as holes in the upper cloud decks. As they are stable features that can persist for several months, they are thought to be vortex

In fluid dynamics, a vortex ( : vortices or vortexes) is a region in a fluid in which the flow revolves around an axis line, which may be straight or curved. Vortices form in stirred fluids, and may be observed in smoke rings, whirlpools in th ...

structures. Often associated with dark spots are brighter, persistent methane clouds that form around the tropopause

The tropopause is the atmospheric boundary that demarcates the troposphere from the stratosphere; which are two of the five layers of the atmosphere of Earth. The tropopause is a thermodynamic gradient-stratification layer, that marks the end of ...

layer. The persistence of companion clouds shows that some former dark spots may continue to exist as cyclones even though they are no longer visible as a dark feature. Dark spots may dissipate when they migrate too close to the equator or possibly through some other, unknown mechanism.

Internal heating

Neptune's more varied weather when compared to Uranus is due in part to its higherinternal heating

{{Unreferenced, date=February 2012

Internal heat is the heat source from the interior of celestial objects, such as stars, brown dwarfs, planets, moons, dwarf planets, and (in the early history of the Solar System) even asteroids such as Vesta, re ...

. The upper regions of Neptune's troposphere reach a low temperature of . At a depth where the atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1013.25 millibars, 7 ...

equals , the temperature is . Deeper inside the layers of gas, the temperature rises steadily. As with Uranus, the source of this heating is unknown, but the discrepancy is larger: Uranus only radiates 1.1 times as much energy as it receives from the Sun; whereas Neptune radiates about 2.61 times as much energy as it receives from the Sun. Neptune is the farthest planet from the Sun, and lies over 50% farther from the Sun than Uranus, and receives only 40% its amount of sunlight, yet its internal energy is sufficient to drive the fastest planetary winds seen in the Solar System. Depending on the thermal properties of its interior, the heat left over from Neptune's formation may be sufficient to explain its current heat flow, though it is more difficult to simultaneously explain Uranus

Uranus is the seventh planet from the Sun. Its name is a reference to the Greek god of the sky, Uranus (mythology), Uranus (Caelus), who, according to Greek mythology, was the great-grandfather of Ares (Mars (mythology), Mars), grandfather ...

's lack of internal heat while preserving the apparent similarity between the two planets.

Orbit and rotation

The average distance between Neptune and the Sun is (about 30.1

The average distance between Neptune and the Sun is (about 30.1 astronomical unit

The astronomical unit (symbol: au, or or AU) is a unit of length, roughly the distance from Earth to the Sun and approximately equal to or 8.3 light-minutes. The actual distance from Earth to the Sun varies by about 3% as Earth orbits t ...

s (AU)), and it completes an orbit on average every 164.79 years, subject to a variability of around ±0.1 years. The perihelion distance is 29.81 AU; the aphelion distance is 30.33 AU.

On 11 July 2011, Neptune completed its first full barycentric orbit since its discovery in 1846, although it did not appear at its exact discovery position in the sky, because Earth was in a different location in its 365.26 day orbit. Because of the motion of the Sun in relation to the barycentre

In astronomy, the barycenter (or barycentre; ) is the center of mass of two or more bodies that orbit one another and is the point about which the bodies orbit. A barycenter is a dynamical point, not a physical object. It is an important co ...

of the Solar System, on 11 July Neptune was also not at its exact discovery position in relation to the Sun; if the more common heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at ...

coordinate system is used, the discovery longitude was reached on 12 July 2011.(Bill Folkner at JPL)—Numbers generated using the Solar System Dynamics Group, Horizons On-Line Ephemeris System. The elliptical orbit of Neptune is inclined 1.77° compared to that of Earth. The axial tilt of Neptune is 28.32°, which is similar to the tilts of Earth (23°) and Mars (25°). As a result, Neptune experiences similar seasonal changes to Earth. The long orbital period of Neptune means that the seasons last for forty Earth years. Its sidereal rotation period (day) is roughly 16.11 hours. Because its axial tilt is comparable to Earth's, the variation in the length of its day over the course of its long year is not any more extreme. Because Neptune is not a solid body, its atmosphere undergoes

differential rotation

Differential rotation is seen when different parts of a rotating object move with different angular velocities (rates of rotation) at different latitudes and/or depths of the body and/or in time. This indicates that the object is not solid. In flu ...

. The wide equatorial zone rotates with a period of about 18 hours, which is slower than the 16.1-hour rotation of the planet's magnetic field. By contrast, the reverse is true for the polar regions where the rotation period is 12 hours. This differential rotation is the most pronounced of any planet in the Solar System, and it results in strong latitudinal wind shear.

Orbital resonances

Kuiper belt

The Kuiper belt () is a circumstellar disc in the outer Solar System, extending from the orbit of Neptune at 30 astronomical units (AU) to approximately 50 AU from the Sun. It is similar to the asteroid belt, but is far larger—20 times ...

. The Kuiper belt is a ring of small icy worlds, similar to the asteroid belt

The asteroid belt is a torus-shaped region in the Solar System, located roughly between the orbits of the planets Jupiter and Mars. It contains a great many solid, irregularly shaped bodies, of many sizes, but much smaller than planets, called ...

but far larger, extending from Neptune's orbit at 30 AU out to about 55 AU from the Sun. Much in the same way that Jupiter's gravity dominates the asteroid belt, shaping its structure, so Neptune's gravity dominates the Kuiper belt. Over the age of the Solar System, certain regions of the Kuiper belt became destabilised by Neptune's gravity, creating gaps in the its structure. The region between 40 and 42 AU is an example.

There do exist orbits within these empty regions where objects can survive for the age of the Solar System. These resonances

Resonance describes the phenomenon of increased amplitude that occurs when the frequency of an applied periodic force (or a Fourier component of it) is equal or close to a natural frequency of the system on which it acts. When an oscillatin ...

occur when Neptune's orbital period is a precise fraction of that of the object, such as 1:2, or 3:4. If, say, an object orbits the Sun once for every two Neptune orbits, it will only complete half an orbit by the time Neptune returns to its original position. The most heavily populated resonance in the Kuiper belt, with over 200 known objects, is the 2:3 resonance. Objects in this resonance complete 2 orbits for every 3 of Neptune, and are known as plutino

In astronomy, the plutinos are a dynamical group of trans-Neptunian objects that orbit in 2:3 mean-motion resonance with Neptune. This means that for every two orbits a plutino makes, Neptune orbits three times. The dwarf planet Pluto is the lar ...

s because the largest of the known Kuiper belt objects, Pluto

Pluto (minor-planet designation: 134340 Pluto) is a dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, a ring of trans-Neptunian object, bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. It is the ninth-largest and tenth-most-massive known object to directly orbit the S ...

, is among them. Although Pluto crosses Neptune's orbit regularly, the 2:3 resonance ensures they can never collide. The 3:4, 3:5, 4:7 and 2:5 resonances are less populated.

Neptune has a number of known trojan objects occupying both the Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

–Neptune and Lagrangian point

In celestial mechanics, the Lagrange points (; also Lagrangian points or libration points) are points of equilibrium for small-mass objects under the influence of two massive orbiting bodies. Mathematically, this involves the solution of th ...

s—gravitationally stable regions leading and trailing Neptune in its orbit, respectively. Neptune trojan

Neptune trojans are bodies that orbit the Sun near one of the stable Lagrangian points of Neptune, similar to the Trojan (astronomy), trojans of other planets. They therefore have approximately the same orbital period as Neptune and follow rough ...

s can be viewed as being in a 1:1 resonance with Neptune. Some Neptune trojans are remarkably stable in their orbits, and are likely to have formed alongside Neptune rather than being captured. The first object identified as associated with Neptune's trailing Lagrangian point was . Neptune also has a temporary quasi-satellite

A quasi-satellite is an object in a specific type of co-orbital configuration (1:1 orbital resonance) with a planet (or dwarf planet) where the object stays close to that planet over many orbital periods.

A quasi-satellite's orbit around the Sun t ...

, . The object has been a quasi-satellite of Neptune for about 12,500 years and it will remain in that dynamical state for another 12,500 years.

Formation and migration

The formation of the ice giants, Neptune and Uranus, has proven difficult to model precisely. Current models suggest that the matter density in the outer regions of the Solar System was too low to account for the formation of such large bodies from the traditionally accepted method of core