Naval Fiction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Nautical fiction, frequently also naval fiction, sea fiction, naval adventure fiction or maritime fiction, is a genre of literature with a setting on or near the

Nautical fiction, frequently also naval fiction, sea fiction, naval adventure fiction or maritime fiction, is a genre of literature with a setting on or near the

What constitutes nautical fiction or sea fiction, and their constituent naval, nautical or sea novels, depends largely on the focus of the commentator. Conventionally sea fiction encompasses novels in the vein of Marryat, Conrad, Melville, Forester and O'Brian: novels which are principally set on the sea, and immerse the characters in nautical culture. Typical sea stories follow the narrative format of "a sailor embarks upon a voyage; during the course of the voyage he is tested – by the sea, by his colleagues or by those that he encounters upon another shore; the experience either makes him or breaks him".Peck, pp. 165-185.

Some scholars chose to expand the definition of what constitutes nautical fiction. However, these are inconsistent definitions: some like Bernhard Klein, choose to expand that definition into a thematic perspective, he defines his collection "Fictions of the Sea" around a broader question of the "Britain and the Sea" in literature, which comes to include 16th and 17th maritime instructional literature, and fictional depictions of the nautical which offer lasting cultural resonance, for example Milton's ''

What constitutes nautical fiction or sea fiction, and their constituent naval, nautical or sea novels, depends largely on the focus of the commentator. Conventionally sea fiction encompasses novels in the vein of Marryat, Conrad, Melville, Forester and O'Brian: novels which are principally set on the sea, and immerse the characters in nautical culture. Typical sea stories follow the narrative format of "a sailor embarks upon a voyage; during the course of the voyage he is tested – by the sea, by his colleagues or by those that he encounters upon another shore; the experience either makes him or breaks him".Peck, pp. 165-185.

Some scholars chose to expand the definition of what constitutes nautical fiction. However, these are inconsistent definitions: some like Bernhard Klein, choose to expand that definition into a thematic perspective, he defines his collection "Fictions of the Sea" around a broader question of the "Britain and the Sea" in literature, which comes to include 16th and 17th maritime instructional literature, and fictional depictions of the nautical which offer lasting cultural resonance, for example Milton's ''

James Fenimore Cooper wrote, what is often described as the first sea novel,This is a debatable claim, dependent on the limitations placed on the genre, per the discussion in the definition section. Margaret Cohen, for example, states that " ter a seventy-five year hiatus, the maritime novel was reinvented by James Fenimore Cooper, with the ''Pilot''". ''The Novel and the Sea''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010, p. 133. ''

James Fenimore Cooper wrote, what is often described as the first sea novel,This is a debatable claim, dependent on the limitations placed on the genre, per the discussion in the definition section. Margaret Cohen, for example, states that " ter a seventy-five year hiatus, the maritime novel was reinvented by James Fenimore Cooper, with the ''Pilot''". ''The Novel and the Sea''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010, p. 133. ''

As the model of the sea novel solidified into a distinct genre, writers in both Europe and the United States produced major works of literature in the genre, for example Melville's ''

As the model of the sea novel solidified into a distinct genre, writers in both Europe and the United States produced major works of literature in the genre, for example Melville's ''

Twentieth century novelists expand on the earlier traditions. The

Twentieth century novelists expand on the earlier traditions. The

/ref>

Those nautical novels dealing with life on naval and merchant ships set in the past are often written by men and deal with a purely male world with the rare exception, and a core themes found in these novels is male heroism. orig. presented at the 2000 Central New York Conference on Language and Literature, Cortland, N.Y This creates a generic expectation among readers and publishers. Critic Jerome de Groot identifies naval historical fiction, like Forester's and O'Brian's, as epitomizing the kinds of fiction marketed to men, and nautical fiction being one of the subgenre's most frequently marketed towards men. As John Peck notes, the genre of nautical fiction frequently relies on a more "traditional models of masculinity", where masculinity is a part of a more conservative social order.

Those nautical novels dealing with life on naval and merchant ships set in the past are often written by men and deal with a purely male world with the rare exception, and a core themes found in these novels is male heroism. orig. presented at the 2000 Central New York Conference on Language and Literature, Cortland, N.Y This creates a generic expectation among readers and publishers. Critic Jerome de Groot identifies naval historical fiction, like Forester's and O'Brian's, as epitomizing the kinds of fiction marketed to men, and nautical fiction being one of the subgenre's most frequently marketed towards men. As John Peck notes, the genre of nautical fiction frequently relies on a more "traditional models of masculinity", where masculinity is a part of a more conservative social order.

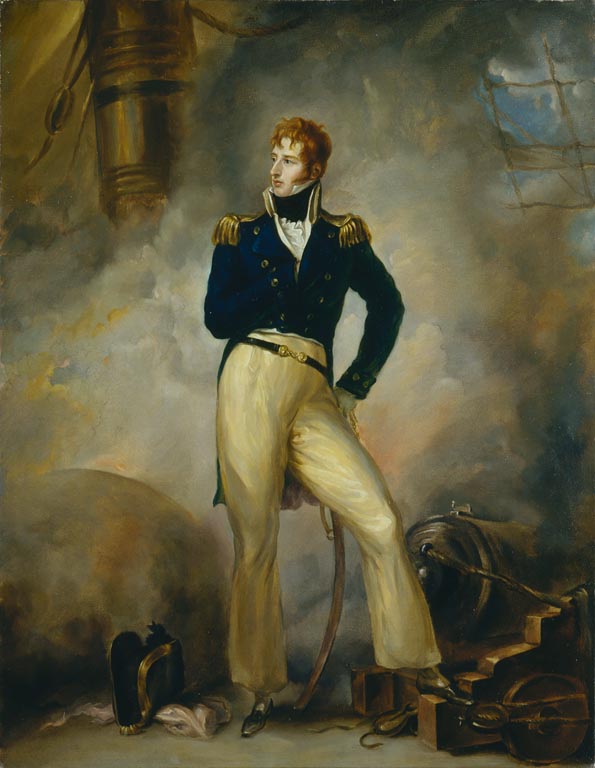

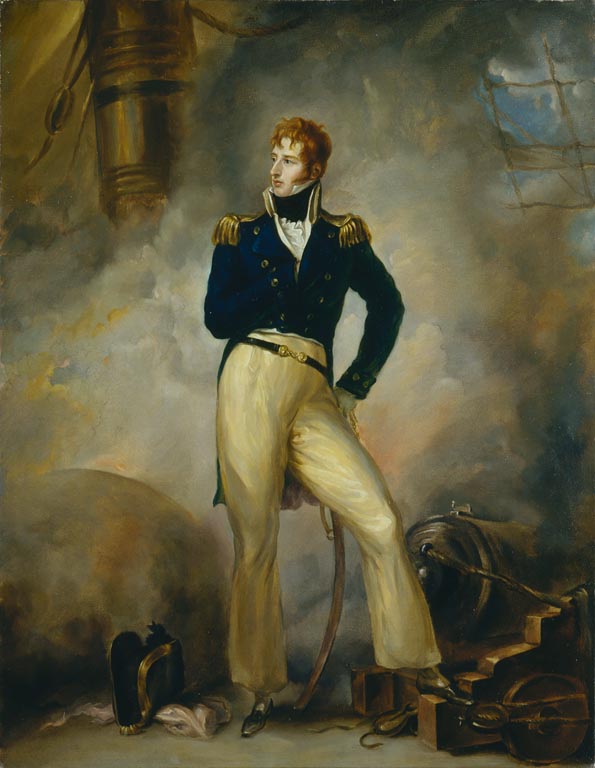

However, as the genre has developed, models of masculinity and the nature of male heroism in sea novels vary greatly, despite being based on similar historical precedents like Thomas Cochrane (nicknamed the "Sea Wolf"), whose heroic exploits have been adapted by Marryat, Forestor, and O'Brian, among others. Susan Bassnet maps a change in the major popular nautical works. On the one hand Marryat's heroes focus on gentlemanly characteristics modeled on idealized ideas of actual captains such as Thomas Cochrane and

However, as the genre has developed, models of masculinity and the nature of male heroism in sea novels vary greatly, despite being based on similar historical precedents like Thomas Cochrane (nicknamed the "Sea Wolf"), whose heroic exploits have been adapted by Marryat, Forestor, and O'Brian, among others. Susan Bassnet maps a change in the major popular nautical works. On the one hand Marryat's heroes focus on gentlemanly characteristics modeled on idealized ideas of actual captains such as Thomas Cochrane and

Although contemporary sea culture includes women working as fishers and even commanding naval ships, maritime fiction on the whole has not followed this cultural change."Women in the Royal Navy serve in many roles; as pilots, observers and air-crew personnel; as divers, and Commanding Officers of HM Ships and shore establishments, notably Cdr Sarah West, who took up her appointment as CO of HMS PORTLAND in 2012, taking her ship from a refit in Rosyth to her current deployment as an Atlantic Patrol vessel. In another milestone for the Royal Navy, Commander Sue Moore was the first woman to command a squadron of minor war vessels; the First Patrol Boat Squadron (1PBS) ... Women can serve in the Royal Marines but not as RM Commandos.

Although contemporary sea culture includes women working as fishers and even commanding naval ships, maritime fiction on the whole has not followed this cultural change."Women in the Royal Navy serve in many roles; as pilots, observers and air-crew personnel; as divers, and Commanding Officers of HM Ships and shore establishments, notably Cdr Sarah West, who took up her appointment as CO of HMS PORTLAND in 2012, taking her ship from a refit in Rosyth to her current deployment as an Atlantic Patrol vessel. In another milestone for the Royal Navy, Commander Sue Moore was the first woman to command a squadron of minor war vessels; the First Patrol Boat Squadron (1PBS) ... Women can serve in the Royal Marines but not as RM Commandos.

for women as crew in the fishing industry, see "Women in Fish harvesting

/ref> Generally, in maritime fiction, women only have a role on passenger ships, as wives of warrant officers, and where the plot is on land. An example of a woman aboard a ship is Joseph Conrad's ''

Historical Naval Fiction

(though this list focuses only on "Age of Sail" fiction) o

More specific thematic lists, includ

* Alain-René Le Sage (1668–1747): ''Vie et aventures de M. de Beauchesne'' (1733) *

Historic Naval Fiction

- a website devoted to cataloging historical fiction within the Naval fiction genre. {{Authority control Literary genres Water transport Maritime books Maritime folklore Historical novels subgenres Adventure fiction

Nautical fiction, frequently also naval fiction, sea fiction, naval adventure fiction or maritime fiction, is a genre of literature with a setting on or near the

Nautical fiction, frequently also naval fiction, sea fiction, naval adventure fiction or maritime fiction, is a genre of literature with a setting on or near the sea

The sea, connected as the world ocean or simply the ocean, is the body of salty water that covers approximately 71% of the Earth's surface. The word sea is also used to denote second-order sections of the sea, such as the Mediterranean Sea, ...

, that focuses on the human relationship to the sea and sea voyages and highlights nautical culture in these environments. The settings of nautical fiction vary greatly, including merchant ships, liners, naval ships, fishing vessels, life boats, etc., along with sea ports and fishing villages. When describing nautical fiction, scholars most frequently refer to novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

s, novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

s, and short stories

A short story is a piece of prose fiction that typically can be read in one sitting and focuses on a self-contained incident or series of linked incidents, with the intent of evoking a single effect or mood. The short story is one of the oldest t ...

, sometimes under the name of sea novels or sea stories. These works are sometimes adapted

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the po ...

for the theatre, film and television.

The development of nautical fiction follows with the development of the English language novel and while the tradition is mainly British and North American, there are also significant works from literatures in Japan, France, Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion#Europe, subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, ...

, and other Western traditions. Though the treatment of themes and settings related to the sea and maritime culture is common throughout the history of western literature, nautical fiction, as a distinct genre, was first pioneered by James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

(''The Pilot

A pilot is a person who flies or navigates an aircraft.

Pilot or The Pilot may also refer to:

* Maritime pilot, a person who guides ships through hazardous waters

* Television pilot, a television episode used to sell a series to a television netw ...

'', 1824) and Frederick Marryat

Captain Frederick Marryat (10 July 1792 – 9 August 1848) was a Royal Navy officer, a novelist, and an acquaintance of Charles Dickens. He is noted today as an early pioneer of nautical fiction, particularly for his semi-autobiographical novel ...

(''Frank Mildmay

Frank or Franks may refer to:

People

* Frank (given name)

* Frank (surname)

* Franks (surname)

* Franks, a medieval Germanic people

* Frank, a term in the Muslim world for all western Europeans, particularly during the Crusades - see Farang

Curre ...

'', 1829 and ''Mr Midshipman Easy

''Mr. Midshipman Easy'' is an 1836 novel by Frederick Marryat, a retired captain in the Royal Navy. The novel is set during the Napoleonic Wars, in which Marryat himself served with distinction.

Plot summary

Easy is the son of foolish parents ...

'' 1836) in the early 19th century. There were 18th century and earlier precursors that have nautical settings, but few are as richly developed as subsequent works in this genre. The genre has evolved to include notable literary works

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include o ...

like Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

's ''Moby Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Ahab, captain of the whaling ship ''Pequod'', for revenge against Moby Dick, the giant whit ...

'' (1851), Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

's ''Lord Jim

''Lord Jim'' is a novel by Joseph Conrad originally published as a serial in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' from October 1899 to November 1900. An early and primary event in the story is the abandonment of a passenger ship in distress by its crew, i ...

'' (1899–1900), popular fiction

Genre fiction, also known as popular fiction, is a term used in the book-trade for fictional works written with the intent of fitting into a specific literary genre, in order to appeal to readers and fans already familiar with that genre.

A num ...

like C.S. Forester's Hornblower series

Horatio Hornblower is a fictional officer in the British Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, the protagonist of a series of novels and stories by C. S. Forester. He later became the subject of films, radio and television programmes, an ...

(1937–67), and works by authors that straddle the divide between popular and literary fiction, like Patrick O'Brian

Patrick O'Brian, Order of the British Empire, CBE (12 December 1914 – 2 January 2000), born Richard Patrick Russ, was an English novelist and translator, best known for his Aubrey–Maturin series of sea novels set in the Royal Navy during t ...

's Aubrey-Maturin series (1970–2004).

Because of the historical dominance of nautical culture by men, they are usually the central characters, except for works that feature ships carrying women passengers. For this reason, nautical fiction is often marketed for men. Nautical fiction usually includes distinctive themes, such as a focus on masculinity

Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with men and boys. Masculinity can be theoretically understood as socially constructed, and there is also evidence that some behaviors con ...

and heroism, investigations of social hierarchies, and the psychological struggles of the individual in the hostile environment of the sea. Stylistically, readers of the genre expect an emphasis on adventure, accurate representation of maritime culture, and use of nautical language.

Works of nautical fiction may be romances, such as historical romance

Historical romance is a broad category of mass-market fiction focusing on romantic relationships in historical periods, which Walter Scott helped popularize in the early 19th century.

Varieties Viking

These books feature Vikings during the Da ...

, fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction involving Magic (supernatural), magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and sometimes inspired by mythology and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy ...

, and adventure fiction

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of Romance (prose fiction)#Definition, romance fiction.

History

In t ...

, and also may overlap with the genres of war fiction

A war novel or military fiction is a novel about war. It is a novel in which the primary action takes place on a battlefield, or in a civilian setting (or home front), where the characters are preoccupied with the preparations for, suffering the ...

, children's literature

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's ...

, travel narratives (such as the Robinsonade

Robinsonade () is a literary genre that takes its name from the 1719 novel ''Robinson Crusoe'' by Daniel Defoe. The success of this novel spawned so many imitations that its name was used to define a genre, which is sometimes described simply a ...

), the social problem novel and psychological fiction

In literature, psychological fiction (also psychological realism) is a narrative genre that emphasizes interior characterization and motivation to explore the spiritual, emotional, and mental lives of the characters. The mode of narration examin ...

.

Definition

What constitutes nautical fiction or sea fiction, and their constituent naval, nautical or sea novels, depends largely on the focus of the commentator. Conventionally sea fiction encompasses novels in the vein of Marryat, Conrad, Melville, Forester and O'Brian: novels which are principally set on the sea, and immerse the characters in nautical culture. Typical sea stories follow the narrative format of "a sailor embarks upon a voyage; during the course of the voyage he is tested – by the sea, by his colleagues or by those that he encounters upon another shore; the experience either makes him or breaks him".Peck, pp. 165-185.

Some scholars chose to expand the definition of what constitutes nautical fiction. However, these are inconsistent definitions: some like Bernhard Klein, choose to expand that definition into a thematic perspective, he defines his collection "Fictions of the Sea" around a broader question of the "Britain and the Sea" in literature, which comes to include 16th and 17th maritime instructional literature, and fictional depictions of the nautical which offer lasting cultural resonance, for example Milton's ''

What constitutes nautical fiction or sea fiction, and their constituent naval, nautical or sea novels, depends largely on the focus of the commentator. Conventionally sea fiction encompasses novels in the vein of Marryat, Conrad, Melville, Forester and O'Brian: novels which are principally set on the sea, and immerse the characters in nautical culture. Typical sea stories follow the narrative format of "a sailor embarks upon a voyage; during the course of the voyage he is tested – by the sea, by his colleagues or by those that he encounters upon another shore; the experience either makes him or breaks him".Peck, pp. 165-185.

Some scholars chose to expand the definition of what constitutes nautical fiction. However, these are inconsistent definitions: some like Bernhard Klein, choose to expand that definition into a thematic perspective, he defines his collection "Fictions of the Sea" around a broader question of the "Britain and the Sea" in literature, which comes to include 16th and 17th maritime instructional literature, and fictional depictions of the nautical which offer lasting cultural resonance, for example Milton's ''Paradise Lost

''Paradise Lost'' is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consists of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse (poetry), verse. A second edition fo ...

'' and Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (originally ''The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere'') is the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–1798 and published in 1798 in the first edition of ''Lyrical Ballad ...

". Choosing not to fall into this wide of a definition, but also opting to include more fiction than just that which is explicitly about the sea, John Peck opts for a broader maritime fiction, which includes works like Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

's ''Mansfield Park

''Mansfield Park'' is the third published novel by Jane Austen, first published in 1814 by Thomas Egerton. A second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray, still within Austen's lifetime. The novel did not receive any public reviews unt ...

'' (1814) and George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans (22 November 1819 – 22 December 1880; alternatively Mary Anne or Marian), known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. She wro ...

's ''Daniel Deronda

''Daniel Deronda'' is a novel written by Mary Ann Evans under the pen name of George Eliot, first published in eight parts (books) February to September 1876. It was the last novel she completed and the only one set in the Victorian society ...

'' (1876), that depict cultural situations dependent on the maritime economy and culture, without explicitly exploring the naval experience.Peck, "Introduction", pp. 1-9. However, as critic Luis Iglasius notes, when defending the genesis of the sea novel genre by James Fenimore Cooper, expanding this definition includes work "tend ngto view the sea from the perspective of the shore" focusing on the effect of a nautical culture on the larger culture or society ashore or focusing on individuals not familiar with nautical life.

This article focuses on the sea/nautical novel and avoids broader thematic discussions of nautical topics in culture. In so doing, this article highlights what critics describe as the more conventional definition for the genre, even when they attempt to expand its scope.

History

Sea narratives have a long history of development, arising from cultures with genres of adventure and travel narratives that profiled the sea and its cultural importance, for exampleHomer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's epic poem

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

the ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

'', the Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

poem '' The Seafarer'', The Icelandic Saga of Eric the Red

The ''Saga of Erik the Red'', in non, Eiríks saga rauða (), is an Icelandic saga on the Norse exploration of North America. The original saga is thought to have been written in the 13th century. It is preserved in somewhat different versions ...

(c.1220–1280), or early European travel narrative

The genre of travel literature encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

One early travel memoirist in Western literature was Pausanias, a Greek geographer of the 2nd century CE. In the early modern period ...

s like Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America'' (1582) and ''The Pri ...

's (c. 1552–1616) ''Voyages'' (1589).Robert Foulke, ''The Sea Voyage Narrative''. (New York: Routledge, 2002). Then during the 18th century, as Bernhard Klein notes in defining "sea fiction" for his scholarly collection on sea fiction, European cultures began to gain an appreciation of the "sea" through varying thematic lenses. First because of the economic opportunities brought by the sea and then through the influence of the Romantic movement

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

. As early as 1712 Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison (1 May 1672 – 17 June 1719) was an English essayist, poet, playwright and politician. He was the eldest son of The Reverend Lancelot Addison. His name is usually remembered alongside that of his long-standing friend Richard S ...

identified "the sea as an archetype of the Sublime in nature: 'of all the objects that I have ever seen, there is none which affects my imagination as much as the sea or ocean' ". Later in this century Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who, with his friend William Wordsworth, was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poe ...

's narrative poem

Narrative poetry is a form of poetry that tells a story, often using the voices of both a narrator and characters; the entire story is usually written in metered verse. Narrative poems do not need rhyme. The poems that make up this genre may be s ...

''Rime of the Ancient Mariner

''The Rime of the Ancient Mariner'' (originally ''The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere'') is the longest major poem by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, written in 1797–1798 and published in 1798 in the first edition of ''Lyrical Ballad ...

'' (1798), developed the idea of the ocean as "realm of unspoiled nature and a refuge from the perceived threats of civilization".Klein, Bernhard, "Introduction:Britain in the Sea" in Klein, ''Fictions of the Sea'', pp. 1-10. However, it is Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

"who has taken most of the credit for inventing the nineteenth-century sea, in ''Childe Harold's Pilgrimage

''Childe Harold's Pilgrimage'' is a long narrative poem in four parts written by Lord Byron. The poem was published between 1812 and 1818. Dedicated to " Ianthe", it describes the travels and reflections of a world-weary young man, who is dis ...

'' (1812–16):

:There is a pleasure in the pathless woods,

:There is a rapture on the lonely shore,

:There is society where none intrudes,

:By the deep Sea and music in its roar.

Early sea novels

A distinct sea novel genre, which focuses on representing nautical culture exclusively, did not gain traction until the early part of the 19th century, however, works dealing with life at sea were written in the 18th century. This includes works dealing withpiracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

, such as Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, trader, journalist, pamphleteer and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its ...

's ''The Life, Adventures & Piracies of the Famous Captain Singleton

''The Life, Adventures and Piracies of the Famous Captain Singleton'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, originally published in 1720. It has been re-published multiple times since, some of which times were in 1840 1927, 1972 and 2008. ''Captain Sing ...

'' (1720), and ''A General History of the Pyrates

''A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates'' is a 1724 book published in Britain containing biographies of contemporary pirates,

'' (1724), a work which contains biographies of several notorious English pirates such as Blackbeard

Edward Teach (alternatively spelled Edward Thatch, – 22 November 1718), better known as Blackbeard, was an English Piracy, pirate who operated around the West Indies and the eastern coast of Britain's Thirteen Colonies, North American colon ...

and Calico Jack

John Rackham (26 December 168218 November 1720), commonly known as Calico Jack, was an English pirate captain operating in the Bahamas and in Cuba during the early 18th century. His nickname was derived from the calico clothing that he wore, whil ...

.

Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett (baptised 19 March 1721 – 17 September 1771) was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for picaresque novels such as ''The Adventures of Roderick Random'' (1748), ''The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle'' (1751) a ...

's ''The Adventures of Roderick Random

''The Adventures of Roderick Random'' is a picaresque novel by Tobias Smollett, first published in 1748. It is partially based on Smollett's experience as a naval-surgeon's mate in the Royal Navy, especially during the Battle of Cartagena de Indi ...

'', published in 1748, is a picaresque novel

The picaresque novel (Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for " rogue" or "rascal") is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish, but "appealing hero", usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrup ...

partially based on Smollett's experience as a naval-surgeon's mate in the British Navy.

19th century

Jonathan Raban

Jonathan Raban (born 14 June 1942, Hempton, Norfolk, England) is a British travel writer, critic, and novelist. He has received several awards, such as the National Book Critics Circle Award, The Royal Society of Literature's Heinemann Award, t ...

suggests that it was the Romantic movement

Romanticism (also known as the Romantic movement or Romantic era) was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate ...

, and especially Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

, which made "the sea the proper habit for aspiring authors", including the two most prominent early sea fiction writers James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

and Captain Frederick Marryat

Captain Frederick Marryat (10 July 1792 – 9 August 1848) was a Royal Navy officer, a novelist, and an acquaintance of Charles Dickens. He is noted today as an early pioneer of nautical fiction, particularly for his semi-autobiographical novel ...

, both of whose maritime adventure novels began to define generic expectations about such fiction. Critic Margaret Cohen describes Cooper's ''The Pilot

A pilot is a person who flies or navigates an aircraft.

Pilot or The Pilot may also refer to:

* Maritime pilot, a person who guides ships through hazardous waters

* Television pilot, a television episode used to sell a series to a television netw ...

'' as the first sea novel and Marryat's adaptation of that style, as continuing to "pioneer" the genre. Critic Luis Iglesias says that novels and fiction that involved the sea before these two authors "tend to view the sea from the perspective of the shore"focusing on the effect of a nautical culture on the larger culture or society ashore or individuals not familiar with nautical life; by example Iglesias points to how Jane Austen's novels don't represent the genre, because, though the sea plays a prominent part in their plots, it keeps actual sea-culture at a "peripheral presence"; similarly, Iglesias describes earlier English novels like ''Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' () is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. The first edition credited the work's protagonist Robinson Crusoe as its author, leading many readers to believe he was a real person and the book a tra ...

'' (1719), ''Moll Flanders

''Moll Flanders'' is a novel by Daniel Defoe, first published in 1722. It purports to be the true account of the life of the eponymous Moll, detailing her exploits from birth until old age.

By 1721, Defoe had become a recognised novelist, wit ...

'' (1722), or ''Roderick Random

Roderick, Rodrick or Roderic (Proto-Germanic ''*wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Germanic/Hrōþirīks, Hrōþirīks'', from ''*wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Germanic/hrōþiz, hrōþiz'' "fame, glory" + ''*wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Germanic/rīks, ríks'' ...

'' (1748) as populating the naval world with characters unfamiliar with the sea to better understand land-bound society, not fulfilling the immersive generic expectations of nautical fiction. From the development of the genre's motifs and characteristics in works like Cooper's and Marryat's, a number of notable European novelists, such as Eugène Sue

Marie-Joseph "Eugène" Sue (; 26 January 18043 August 1857) was a French novelist. He was one of several authors who popularized the genre of the serial novel in France with his very popular and widely imitated ''The Mysteries of Paris'', which ...

, Edouard Corbière, Frederick Chamier

Frederick Chamier (2 November 1796 – 29 October 1870) was an English novelist, autobiographer and naval captain born in London. He was the author of several nautical novels that remained popular through the 19th century.

Life

Chamier was the s ...

and William Glasgock, innovated and explored the genre subsequently.

James Fenimore Cooper wrote, what is often described as the first sea novel,This is a debatable claim, dependent on the limitations placed on the genre, per the discussion in the definition section. Margaret Cohen, for example, states that " ter a seventy-five year hiatus, the maritime novel was reinvented by James Fenimore Cooper, with the ''Pilot''". ''The Novel and the Sea''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010, p. 133. ''

James Fenimore Cooper wrote, what is often described as the first sea novel,This is a debatable claim, dependent on the limitations placed on the genre, per the discussion in the definition section. Margaret Cohen, for example, states that " ter a seventy-five year hiatus, the maritime novel was reinvented by James Fenimore Cooper, with the ''Pilot''". ''The Novel and the Sea''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010, p. 133. ''The Pilot

A pilot is a person who flies or navigates an aircraft.

Pilot or The Pilot may also refer to:

* Maritime pilot, a person who guides ships through hazardous waters

* Television pilot, a television episode used to sell a series to a television netw ...

'' (1824), in response to Walter Scott's '' The Pirate'' (1821).Peck, "American Sea Fiction", in ''Maritime Fiction'', 98-106. Cooper was frustrated with the inaccuracy of the nautical culture represented in that work. Though critical of ''The Pirate'', Cooper borrowed many of the stylistic and thematic elements of the historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

genre developed by Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet, playwright and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'', ''Rob Roy (n ...

, such as a desire "to map the boundaries and identity of the nation." In both ''The Pilot

A pilot is a person who flies or navigates an aircraft.

Pilot or The Pilot may also refer to:

* Maritime pilot, a person who guides ships through hazardous waters

* Television pilot, a television episode used to sell a series to a television netw ...

'' and the subsequent ''The Red Rover

''The Red Rover'' is a novel by American writer James Fenimore Cooper. It was originally published in Paris on November 27, 1827, before being published in London three days later on November 30. It was not published in the United States until Ja ...

'' (1827) Cooper explores the development of an American national identity, and in his later '' Afloat and Ashore'' (1844) he again examines the subject of national identity. as well as offering a critique of American politics. Cooper's novels created an interest in sea novels in the United States, and led both Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

in ''The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym

''The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket'' (1838) is the only complete novel written by American writer Edgar Allan Poe. The work relates the tale of the young Arthur Gordon Pym, who stows away aboard a whaling ship called the ''Grampus ...

'' (1838) as well as mass-market novelists like Lieutenant Murray Ballou to write novels in the genre. The prominence of the genre also influenced non-fiction. Critic John Peck describe's Richard Henry Dana's ''Two Years Before the Mast

''Two Years Before the Mast'' is a memoir by the American author Richard Henry Dana Jr., published in 1840, having been written after a two-year sea voyage from Boston to California on a merchant ship starting in 1834. A film adaptation under the ...

'' (1840) as utilizing a similar style and addressing the same thematic issues of national and masculine identity as nautical fiction developing after Cooper's pioneering works.

Fenimore Cooper greatly influenced the French novelist Eugène Sue

Marie-Joseph "Eugène" Sue (; 26 January 18043 August 1857) was a French novelist. He was one of several authors who popularized the genre of the serial novel in France with his very popular and widely imitated ''The Mysteries of Paris'', which ...

(1804 –1857), whose own his naval experiences supplied much of the materials for Sue's first novels, ''Kernock le pirate'' (1830), ''Atar-Gull'' (1831), the "widely admired" ''La Salamandre'' (1832), ''La Coucaratcha'' (1832–1834), and others, which were composed at the height of the Romantic movement. The more famous French novelist Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (, ; ; born Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie (), 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas père (where '' '' is French for 'father', to distinguish him from his son Alexandre Dumas fils), was a French writer ...

(1802–1870) "made no secret of his admiration for Cooper" and wrote ''Le Capitaine Paul'' (1838) as a sequel to Cooper's ''Pilot''.

Another French novelist who had a seafarer background was Edouard Corbière (1793–1875), the author of numerous maritime novels, including ''Les Pilotes de l'Iroise'' (1832), and ''Le Négrier, aventures de mer'', (1834).

In Britain, the genesis of a nautical fiction tradition is often attributed to Frederick Marryat. Frederick Marryat's career as a novelist stretched from 1829 until his death in 1848, with many set at sea, including ''Mr Midshipman Easy

''Mr. Midshipman Easy'' is an 1836 novel by Frederick Marryat, a retired captain in the Royal Navy. The novel is set during the Napoleonic Wars, in which Marryat himself served with distinction.

Plot summary

Easy is the son of foolish parents ...

''.Susan Bassnett "Cabin'd Yet Unconfined: Heroic Masculinity in English Seafaring Novels" in Klein Fictions of the Sea'' Adapting Cooper's approach to fiction, Marryat's sea novels also reflected his own experience in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

during the Napoleonic wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, in part under the command of Thomas Cochrane—who would also later inspire Patrick O'Brian's character Jack Aubrey

John "Jack" Aubrey , is a fictional character in the Aubrey–Maturin series of novels by Patrick O'Brian. The series portrays his rise from lieutenant to rear admiral in the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars. The twenty (and one incomple ...

. Thematically Marryat focuses on ideas of heroism, proper action of officers, and reforms within the culture of the navy. Marryat's literary works participate in a larger British cultural examination of maritime service during the early part of the 19th century, where subjects such as naval discipline and naval funding were in widespread public debate. Peck describes Marryat's novels as consistent in their core thematic focuses on masculinity and the contemporary naval culture, and in doing so, he suggests, they provide a complex reflection on "a complex historical moment in which author, in his clumsy way, engages with rapid change in Britain." Marryat's novels encouraged the writing of other novels from veterans of the Napoleonic wars during the 1830s, like M.H. Baker

MH or mH may refer to:

Businesses and organizations

* Malaysia Airlines, by IATA airline designator

* Menntaskólinn við Hamrahlíð, a Gymnasium (school), gymnasium in Reykjavík, Iceland

* Miami Heat, an NBA basketball team

Places

* Mahalle, ...

, Captain Chamier, Captain Glascock, Edward Howard, and William J. Neale; these authors frequently both reflect on and defend the public image of the navy.Peck, pp. 50-69. Novels by these authors highlight a more conservative, and supportive view of the navy, unlike texts from those interested in reforming the navy, like Nautical Economy; or forecastle recollections of events during the last war, which were critical of naval disciplinary practices, during a period when public debates ensued around various social and political reform movements. Marryat's novels tend to be treated as unique in comparison to these other works however; Peck argues that Marryat's novels, though in part supportive of the navy, also highlight a "disturbing dimension" of the navy.

Late 19th century

As the model of the sea novel solidified into a distinct genre, writers in both Europe and the United States produced major works of literature in the genre, for example Melville's ''

As the model of the sea novel solidified into a distinct genre, writers in both Europe and the United States produced major works of literature in the genre, for example Melville's ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael (Moby-Dick), Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Captain Ahab, Ahab, captain of the whaler, whaling ship ''Pequod (Moby- ...

'', Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

's '' Toilers of the Sea'' and Joseph Conrad's ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The novel ...

'' and ''Lord Jim

''Lord Jim'' is a novel by Joseph Conrad originally published as a serial in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' from October 1899 to November 1900. An early and primary event in the story is the abandonment of a passenger ship in distress by its crew, i ...

''. John Peck describes Herman Mellville and Joseph Conrad as the "two great English-language writers of sea stories": better novelists than predecessors Cooper and Marryat, both flourished writing in the "adventure novel

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of romance fiction.

History

In the Introduction to the ''Encyclopedi ...

" genre.Peck, pp. 107-126. Moreover, unlike the earlier novels, which were written during a thriving nautical economic boom, full of opportunities and affirmation of national identity, novels by these authors were written "at a point where a maritime based economic order asdisintegrating." The genre also inspired a number of popular mass-market authors, like American Ned Buntline

Edward Zane Carroll Judson Sr. (March 20, 1821 – July 16, 1886), known by his pseudonym Ned Buntline, was an American publisher, journalist, and writer.

Early life and military service

Judson was born on March 20, 1821, in Harpersfield, New Yo ...

, Britain Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the working ...

and Frenchman Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraor ...

.

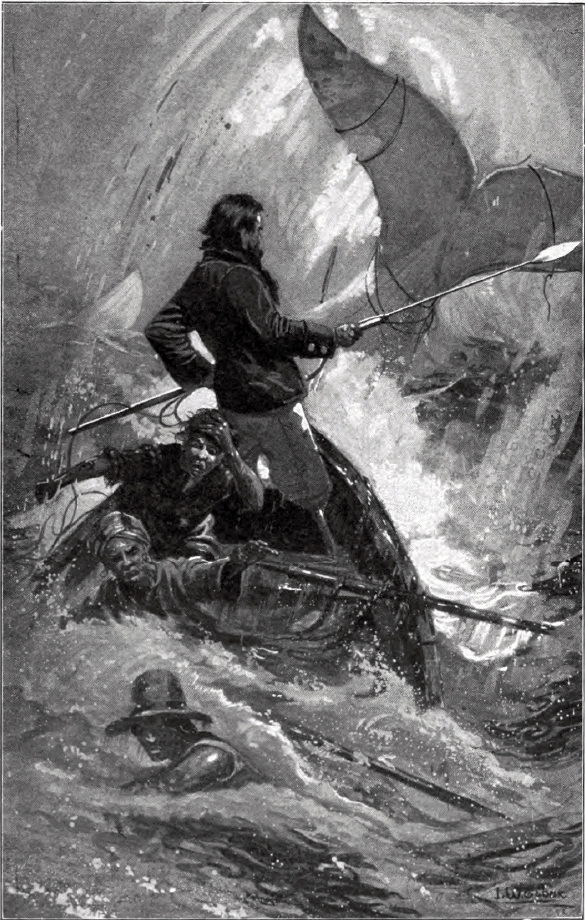

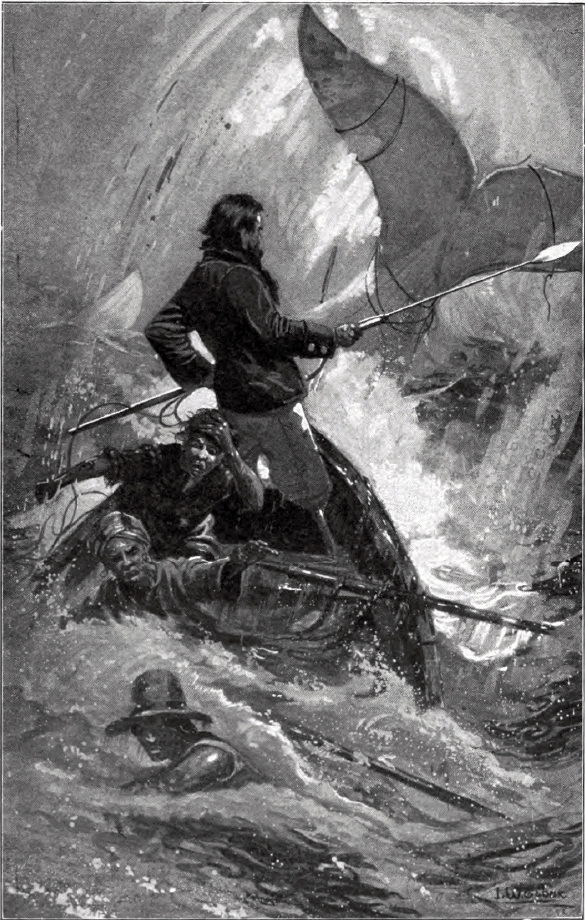

Mellville's fiction frequently involves the sea, with his first five novels following the naval adventures of seamen, often a pair of male friends (''Typee

''Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life'' is American writer Herman Melville's first book, published in 1846, when Melville was 26 years old. Considered a classic in travel and adventure literature, the narrative is based on Melville's experiences on ...

'' (1846), ''Omoo

''Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas'' is the second book by American writer Herman Melville, first published in London in 1847, and a sequel to his first South Sea narrative ''Typee'', also based on the author's experiences in the ...

'' (1847), ''Mardi

''Mardi: and a Voyage Thither'' is the third book by American writer Herman Melville, first published in London in 1849. Beginning as a travelogue in the vein of the author's two previous efforts, the adventure story gives way to a romance story, ...

'' (1849), ''Redburn

''Redburn: His First Voyage'' is the fourth book by the American writer Herman Melville, first published in London in 1849. The book is semi-autobiographical and recounts the adventures of a refined youth among coarse and brutal sailors and the s ...

'' (1849) and ''White-Jacket

''White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War'' is the fifth book by American writer Herman Melville, first published in London in 1850. The book is based on the author's fourteen months' service in the United States Navy, aboard the frigate USS ' ...

'' (1850) ). However, ''Moby-Dick

''Moby-Dick; or, The Whale'' is an 1851 novel by American writer Herman Melville. The book is the sailor Ishmael (Moby-Dick), Ishmael's narrative of the obsessive quest of Captain Ahab, Ahab, captain of the whaler, whaling ship ''Pequod (Moby- ...

'' is his most important work, sometimes called the Great American Novel

The Great American Novel (sometimes abbreviated as GAN) is a canonical novel that is thought to embody the essence of America, generally written by an American and dealing in some way with the question of America's national character. The ter ...

, it was also named "the greatest book of the sea ever written" by D.H. Lawrence. In this work, the hunting of a whale by Captain Ahab, immerses the narrator Ishmael in a spiritual journey, a theme which is developed again in Conrad's much later ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The novel ...

''.

The importance of naval power in maintaining Britains' vast worldwide empire led to numerous novels with nautical themes.Peck, "Mid-Victorian Maritime Fiction", pp. 127–148. Some of these just touch on the sea, as with ''Sylvia's Lovers

''Sylvia's Lovers'' (1863) is a novel written by Elizabeth Gaskell, which she called "the saddest story I ever wrote".

Plot summary

The novel begins in the 1790s in the coastal town of Monkshaven (modeled on Whitby, England) against the backgro ...

'' (1863) by Elizabeth Gaskell, where the nautical world is a foil to the social life ashore. However, British novelists increasingly focused on the sea in the 19th century, particular when they focus on the upper classes. In such works sea voyages became a place for strong social commentary, as, for example Trollope's '' John Caldigate'' (1877), in which Trollope depicts a character travelling to Australia to make his fortune, and Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1859), a mystery novel and early "sensation novel", and for ''The Moons ...

's '' Armadale'' (1866), which follows gentlemen yachting. Likewise William Clark Russell

William Clark Russell (24 February 18448 November 1911) was an English writer best known for his nautical novels.

At the age of 13 Russell joined the United Kingdom's Merchant Navy (United Kingdom), Merchant Navy, serving for eight years. The h ...

's novels, especially the first two, '' John Holdsworth, Chief Mate'' (1875) and ''The Wreck of the Grosvenor

''The Wreck of the Grosvenor'' (1877)Commonly incorrectly stated as published anonymously in 1875. is a nautical novel by William Clark Russell first published in 3 volumes by Sampson Low. According to John Sutherland, it was "the most popular ...

'' (1877), both of which highlight the social anxieties of Victorian Britain

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

.

At the same time that literary works embraced the sea narrative in Britain, so did the most popular novels of adventure fiction, of which Marryat is a major example. Critic John Peck emphasises this subgenre's impact on boys' books. In these novels young male characters go through—often morally whitewashed—experiences of adventure, romantic entanglement, and "domestic commitment". Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (12 June 1819 – 23 January 1875) was a broad church priest of the Church of England, a university professor, social reformer, historian, novelist and poet. He is particularly associated with Christian socialism, the working ...

is the most definitive writers of this genre, writing over one hundred boys' books, "many with a maritime theme", including ''Westward Ho!

Westward Ho! is a seaside village near Bideford in Devon, England. The A39 road provides access from the towns of Barnstaple, Bideford, and Bude. It lies at the south end of Northam Burrows and faces westward into Bideford Bay, opposite Saunto ...

''.Peck, pp. 149-164. Other authors include R. M. Ballantyne

Robert Michael Ballantyne (24 April 1825 – 8 February 1894) was a Scottish author of juvenile fiction, who wrote more than a hundred books. He was also an accomplished artist: he exhibited some of his water-colours at the Royal Scottish Acade ...

, ''The Coral Island

''The Coral Island: A Tale of the Pacific Ocean'' (1857) is a novel written by Scottish people, Scottish author . One of the first works of young adult fiction, juvenile fiction to feature exclusively juvenile heroes, the story relates the a ...

'' (1858), G.A. Henty

George Alfred Henty (8 December 1832 – 16 November 1902) was an English novelist and war correspondent. He is most well-known for his works of adventure fiction and historical fiction, including ''The Dragon & The Raven'' (1886), ''For The ...

, '' Under Drake's Flag'' (1882), Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

, ''Treasure Island

''Treasure Island'' (originally titled ''The Sea Cook: A Story for Boys''Hammond, J. R. 1984. "Treasure Island." In ''A Robert Louis Stevenson Companion'', Palgrave Macmillan Literary Companions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. .) is an adventure no ...

'' (1883), and Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British India, which inspired much of his work.

...

, ''Captains Courageous

''Captains Courageous: A Story of the Grand Banks'' is an 1897 novel by Rudyard Kipling that follows the adventures of fifteen-year-old Harvey Cheyne Jr., the spoiled son of a railroad tycoon, after he is saved from drowning by a Portuguese f ...

'' (1897), all of which were also read by adults, and helped expand the potential of naval adventure fiction. Other novels by Stevenson, including ''Kidnapped

Kidnapped may refer to:

* subject to the crime of kidnapping

Literature

* ''Kidnapped'' (novel), an 1886 novel by Robert Louis Stevenson

* ''Kidnapped'' (comics), a 2007 graphic novel adaptation of R. L. Stevenson's novel by Alan Grant and Ca ...

'', ''Catriona

Catriona (pronounced "ka-TREE-nah" is a feminine given name in the English language. It is an Anglicisation of the Irish language, Irish Caitríona or Scottish Gaelic Catrìona, which are forms of the English Katherine (given name), Katherine.

...

'', ''The Master of Ballantrae

''The Master of Ballantrae: A Winter's Tale'' is an 1889 novel by the Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson, focusing upon the conflict between two brothers, Scottish noblemen whose family is torn apart by the Jacobite rising of 1745. He wor ...

'', and ''The Ebb-Tide

''The Ebb-Tide. A Trio and a Quartette'' (1894) is a short novel written by Robert Louis Stevenson and his stepson Lloyd Osbourne. It was published the year Stevenson died.

Plot

Three beggars operate in the port of Papeete on Tahiti. They are ...

'' (co-authored with Lloyd Osbourne) have significant scenes aboard ships.

The 20th and 21st centuries

Twentieth century novelists expand on the earlier traditions. The

Twentieth century novelists expand on the earlier traditions. The modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and short story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in t ...

drew inspiration from a range of earlier nautical works like Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romantic writer and politician. During a literary career that spanned more than sixty years, he wrote in a variety of genres and forms. He is considered to be one of the great ...

's '' Toilers of the Sea'' (1866), and Leopold McClintock

Sir Francis Leopold McClintock (8 July 1819 – 17 November 1907) was an Irish explorer in the British Royal Navy, known for his discoveries in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. He confirmed explorer John Rae's controversial report gather ...

's book about his 1857–59 expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin

Sir John Franklin (16 April 1786 – 11 June 1847) was a British Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. After serving in wars against Napoleonic France and the United States, he led two expeditions into the Canadian Arctic and through ...

's lost ships, as well as works by James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

and Frederick Marryat

Captain Frederick Marryat (10 July 1792 – 9 August 1848) was a Royal Navy officer, a novelist, and an acquaintance of Charles Dickens. He is noted today as an early pioneer of nautical fiction, particularly for his semi-autobiographical novel ...

. Most of Conrad's works draw directly from this seafaring career: Conrad had a career in both the French and British merchant marine, climbing to the rank of captain. His most famous novel, ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' (1899) is a novella by Polish-English novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgian company in the African interior. The novel ...

'' (1899), is based on a three-year employment with a Belgian trading company. His other nautical fiction includes ''An Outcast of the Islands

''An Outcast of the Islands'' is the second novel by Joseph Conrad, published in 1896, inspired by Conrad's experience as mate of a steamer, the ''Vidar''.

The novel details the undoing of Peter Willems, a disreputable, immoral man who, on the ...

'' (1896) ''The Nigger of the 'Narcissus'

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'' (1897), ''Lord Jim

''Lord Jim'' is a novel by Joseph Conrad originally published as a serial in ''Blackwood's Magazine'' from October 1899 to November 1900. An early and primary event in the story is the abandonment of a passenger ship in distress by its crew, i ...

'' (1900), ''Typhoon

A typhoon is a mature tropical cyclone that develops between 180° and 100°E in the Northern Hemisphere. This region is referred to as the Northwestern Pacific Basin, and is the most active tropical cyclone basin on Earth, accounting for a ...

'' (1902), ''Chance

Chance may refer to:

Mathematics and Science

* In mathematics, likelihood of something (by way of the Likelihood function and/or Probability density function).

* ''Chance'' (statistics magazine)

Places

* Chance, Kentucky, US

* Chance, Mary ...

'' (1913), '' The Rescue'' (1920), '' The Rover'' (1923).

A number of other novelists started writing nautical fiction early in the century. Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

's ''The Sea Wolf

Seawolf, Sea wolf or Sea Wolves may refer to:

Animals

* Sea wolf, a wolf subspecies found in the Vancouver coastal islands

* Seawolf (fish), a marine fish also known as wolffish or sea wolf

* A nickname of the killer whale

* South American sea ...

'' (1904), was influenced by Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English novelist, short-story writer, poet, and journalist. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much o ...

's recently published ''Captains Courageous

''Captains Courageous: A Story of the Grand Banks'' is an 1897 novel by Rudyard Kipling that follows the adventures of fifteen-year-old Harvey Cheyne Jr., the spoiled son of a railroad tycoon, after he is saved from drowning by a Portuguese f ...

'' (1897). Welsh novelist Richard Hughes (1900–1976) wrote only four novels, the most famous of which is the pirate adventure, '' A High Wind in Jamaica''. He also wrote ''In Hazard'' (1938) about a merchant ship caught in a hurricane. English poet and novelist John Masefield

John Edward Masefield (; 1 June 1878 – 12 May 1967) was an English poet and writer, and Poet Laureate from 1930 until 1967. Among his best known works are the children's novels ''The Midnight Folk'' and ''The Box of Delights'', and the poem ...

(1878–1967), who had himself served at sea, wrote ''The Bird of Dawning'' (1933), relating the adventures of the crew of a China tea clipper, who are forced to abandon ship and take to the boats.

The novels of two other prominent British sea novelists, C.S. Forester (1899–1966) and Patrick O'Brian

Patrick O'Brian, Order of the British Empire, CBE (12 December 1914 – 2 January 2000), born Richard Patrick Russ, was an English novelist and translator, best known for his Aubrey–Maturin series of sea novels set in the Royal Navy during t ...

(1914–2000), define the conventional boundaries of contemporary naval fiction. A number of later authors draw on Forester's and O'Brian's models of representing individual officers or sailors as they progress through their careers in the British navy, including Alexander Kent and Dudley Pope

Dudley Bernard Egerton Pope (29 December 1925 – 25 April 1997) was a British writer of both nautical fiction and history, most notable for his Lord Ramage series of historical novels. Greatly inspired by C.S. Forester, Pope was one of the mos ...

. Patrick O'Brian's Aubrey-Maturin series straddles the divide between popular and literary fiction

Literary fiction, mainstream fiction, non-genre fiction or serious fiction is a label that, in the book trade, refers to market novels that do not fit neatly into an established genre (see genre fiction); or, otherwise, refers to novels that are ch ...

, distinguishing itself from Hornblower, one reviewer even commented the books have "escaped the usual confines of naval adventure . .attract ngnew readers who wouldn’t touch Horatio Hornblower with a bargepole." There are also reviews that compare these works to Jane Austen

Jane Austen (; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six major novels, which interpret, critique, and comment upon the British landed gentry at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots of ...

and similar authors. though this is not a universally held opinion.

Several other notable authors, wrote contemporary to O'Brian and Forester, but expanded the boundaries of the genre. Nicholas Monsarrat

Lieutenant Commander Nicholas John Turney Monsarrat FRSL RNVR (22 March 19108 August 1979) was a British novelist known for his sea stories, particularly '' The Cruel Sea'' (1951) and ''Three Corvettes'' (1942–45), but perhaps known best in ...

's novel '' The Cruel Sea'' (1951) follows a young naval officer Keith Lockhart during World War II service aboard "small ships". Monsarrat's short-story collections ''H.M.S. Marlborough Will Enter Harbour'' (1949), and ''The Ship That Died of Shame'' (1959) previously made into a film of the same name, mined the same literary vein, and gained popularity by association with ''The Cruel Sea''. Another important British novelist who wrote about life at sea was William Golding

Sir William Gerald Golding (19 September 1911 – 19 June 1993) was a British novelist, playwright, and poet. Best known for his debut novel ''Lord of the Flies'' (1954), he published another twelve volumes of fiction in his lifetime. In 1980 ...

(1911–1993). His novel ''Pincher Martin

''Pincher Martin'' (published in America as ''Pincher Martin: The Two Deaths of Christopher Martin'') is a novel by British people, British writer William Golding, first published in 1956. It is Golding's third novel, following ''The Inheritors ( ...

'' (1956) records the delusions experienced by a drowning sailor in his last moments. Golding's postmodern

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by skepticism toward the " grand narratives" of moderni ...

ist trilogy ''To the Ends of the Earth

''To the Ends of the Earth'' is the title given to a trilogy of nautical, relational novels—''Rites of Passage'' (1980), ''Close Quarters'' (1987), and ''Fire Down Below'' (1989)—by British author William Golding. Set on a former British ...

'' is about sea voyages to Australia in the early nineteenth century, and draws extensively on the traditions of Jane Austen, Joseph Conrad and Herman Melville, and is Golding's most extensive piece of historiographic metafiction Historiographic metafiction is a term coined by Canadian literary theorist Linda Hutcheon in the late 1980s. It incorporates three domains: fiction, history, and theory.

Concept

The term is used for works of fiction which combine the literary de ...

.

Four of Arthur Ransome

Arthur Michell Ransome (18 January 1884 – 3 June 1967) was an English author and journalist. He is best known for writing and illustrating the ''Swallows and Amazons'' series of children's books about the school-holiday adventures of childre ...

’s children's novels in the Swallows and Amazons series

The ''Swallows and Amazons'' series is a series of twelve children's adventure novels by English author Arthur Ransome. Set in the interwar period, the novels involve group adventures by children, mainly in the school holidays and mainly in En ...

(published 1930–1947) involve sailing at sea (''Peter Duck

''Peter Duck'' is the third book in the ''Swallows and Amazons'' series by Arthur Ransome. The Swallows and Amazons sail to Crab Island with Captain Flint and Peter Duck, an old sailor, to recover buried treasure. During the voyage the ''Wildcat ...

, We Didn't Mean To Go To Sea

''We Didn't Mean to Go to Sea'' is the seventh book in Arthur Ransome's ''Swallows and Amazons'' series of children's books. It was published in 1937. In this book, the Swallows (John, Susan, Titty and Roger Walker) are the only recurring cha ...

, Missee Lee

''Missee Lee'' is the tenth book of Arthur Ransome's Swallows and Amazons series of children's books, set in 1930s China. The Swallows and Amazons are on a round-the-world trip with Captain Flint aboard the schooner ''Wild Cat''. After the ''Wild ...

and Great Northern?''). The others are about sailing small boats in the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or ''fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

or on the Norfolk Broads

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North ...

. Two short stories in Coots in the North

''Coots in the North'' is the name given by Arthur Ransome's biographer, Hugh Brogan, to an incomplete Swallows and Amazons novel found in Ransome's papers. Brogan edited and published the first few chapters as a fragment with a selection of Ran ...

are about sailing on a yacht in the Baltic: ''The Unofficial Side'' and ''Two Shorts and a Long.''

Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

novelist Frans G. Bengtsson

Frans Gunnar Bengtsson (4 October 1894 – 19 December 1954) was a Swedish novelist, essayist, poet and biographer. He was born in Tåssjö (now in Ängelholm Municipality) in Skåne and died at Ribbingsfors Manor in northern Västergötla ...

became widely known for his Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

saga novel ''Röde Orm'' (''The Long Ships

''The Long Ships'' or ''Red Orm'' (original Swedish: ''Röde Orm'' meaning ''Red Serpent'' or ''Red Snake'') is an adventure novel by the Swedish writer Frans G. Bengtsson.

The narrative is set in the late 10th century and follows the adventu ...

''), published in two parts in 1941 and 1945. The hero Orm, later called Röde Orm (Red Snake) because of his red beard, is kidnapped as a boy onto a raiding ship and leads an exciting life in the Mediterranean area around the year 1000 AD. Later, he makes an expedition eastward into what is now Russia. ''The Long Ships'' was later adapted into a film.

Authors continue writing nautical fiction in the twenty-first century, including, for example, another Scandinavian, Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish ance ...

novelist Carsten Jensen

Carsten Jensen (born 24 July 1952, Marstal, Denmark) is a Danish author and political columnist. He first earned recognition as a literary critic for the Copenhagen daily, ''Politiken.'' His novels, including ''I Have Seen the World Begin'' (1996 ...

's (1952–) epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film with heroic elements

Epic or EPIC may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and medi ...

novel ''We, the drowned'' (2006) describes life on both sea and land from the beginning of Danish-Prussian War

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. T ...

in 1848 to the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The novel focuses on the Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish ance ...

seaport of Marstal

Marstal () is a town in southern Denmark, located in Ærø Municipality on the island of Ærø. Marstal has a population of 2,120 (1 January 2022)Ærø

Ærø () is one of the Danish Baltic Sea islands, and part of the Southern Denmark Region.

Since 1 January 2006 the whole of Ærø has constituted a single municipality, known as Ærø Kommune. Before that date, there were two municipalities o ...

, and voyages by the town's seamen all over the globe.Book review: Carsten Jensen's 'We, the Drowned' by Peter Behrens, February 22, 201/ref>

Common themes

Masculinity and heroism

Those nautical novels dealing with life on naval and merchant ships set in the past are often written by men and deal with a purely male world with the rare exception, and a core themes found in these novels is male heroism. orig. presented at the 2000 Central New York Conference on Language and Literature, Cortland, N.Y This creates a generic expectation among readers and publishers. Critic Jerome de Groot identifies naval historical fiction, like Forester's and O'Brian's, as epitomizing the kinds of fiction marketed to men, and nautical fiction being one of the subgenre's most frequently marketed towards men. As John Peck notes, the genre of nautical fiction frequently relies on a more "traditional models of masculinity", where masculinity is a part of a more conservative social order.

Those nautical novels dealing with life on naval and merchant ships set in the past are often written by men and deal with a purely male world with the rare exception, and a core themes found in these novels is male heroism. orig. presented at the 2000 Central New York Conference on Language and Literature, Cortland, N.Y This creates a generic expectation among readers and publishers. Critic Jerome de Groot identifies naval historical fiction, like Forester's and O'Brian's, as epitomizing the kinds of fiction marketed to men, and nautical fiction being one of the subgenre's most frequently marketed towards men. As John Peck notes, the genre of nautical fiction frequently relies on a more "traditional models of masculinity", where masculinity is a part of a more conservative social order.

However, as the genre has developed, models of masculinity and the nature of male heroism in sea novels vary greatly, despite being based on similar historical precedents like Thomas Cochrane (nicknamed the "Sea Wolf"), whose heroic exploits have been adapted by Marryat, Forestor, and O'Brian, among others. Susan Bassnet maps a change in the major popular nautical works. On the one hand Marryat's heroes focus on gentlemanly characteristics modeled on idealized ideas of actual captains such as Thomas Cochrane and

However, as the genre has developed, models of masculinity and the nature of male heroism in sea novels vary greatly, despite being based on similar historical precedents like Thomas Cochrane (nicknamed the "Sea Wolf"), whose heroic exploits have been adapted by Marryat, Forestor, and O'Brian, among others. Susan Bassnet maps a change in the major popular nautical works. On the one hand Marryat's heroes focus on gentlemanly characteristics modeled on idealized ideas of actual captains such as Thomas Cochrane and Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

. On the other hand, Forester's Hornblower is a model hero, presenting bravery, but inadequate at life ashore and beyond the navy and with limited emotional complexity. More recently O'Brian has explored complex ideas about masculinities through his characters Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin's friendship, along with the tension between naval life and shore life, and these men's complex passions and character flaws. Bassnett argues, these models of manliness frequently reflect the historical contexts in which authors write. Marryat's model is a direct political response to the reforms of the Navy and the Napoleonic Wars, while Forrestor is writing about post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...