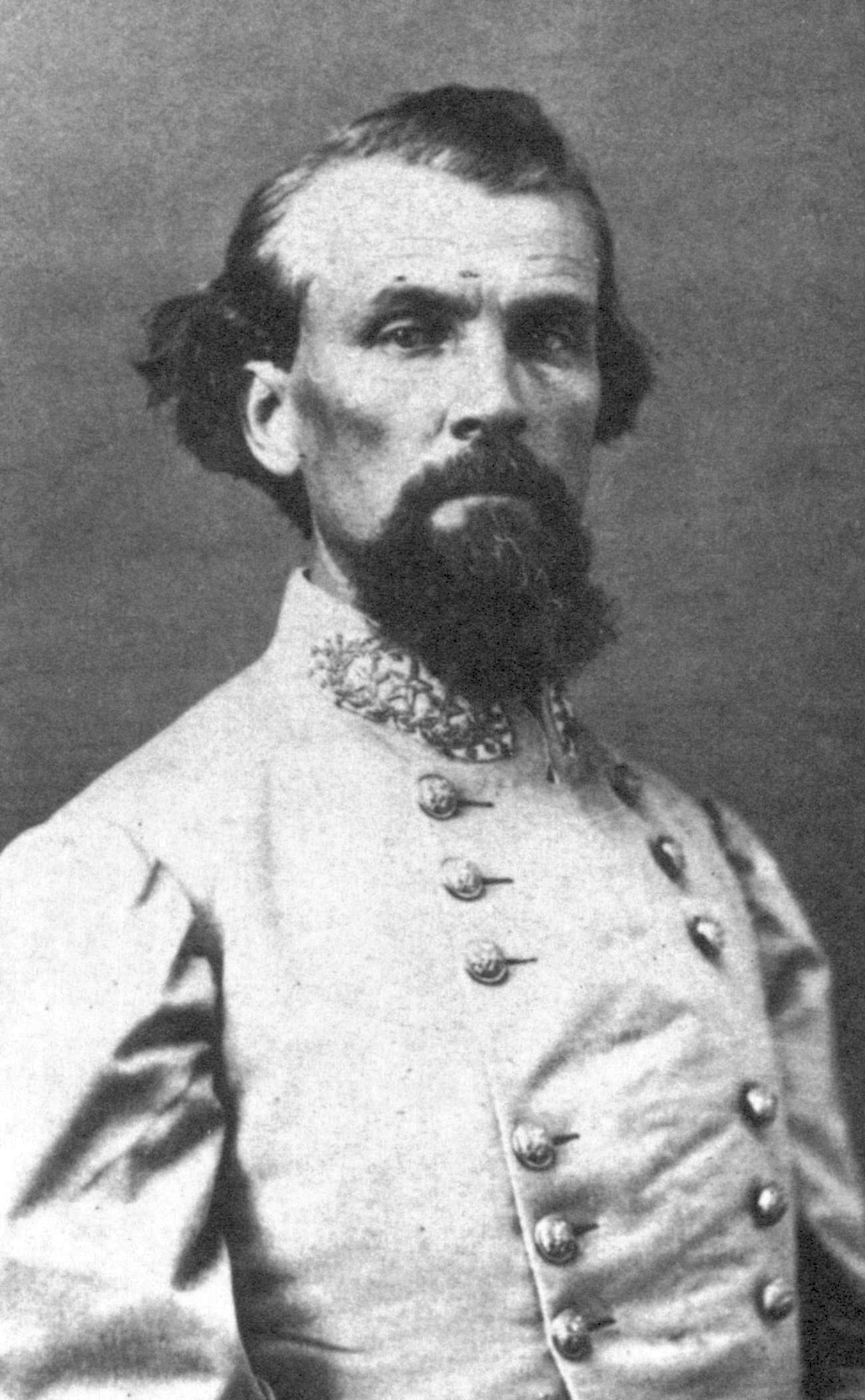

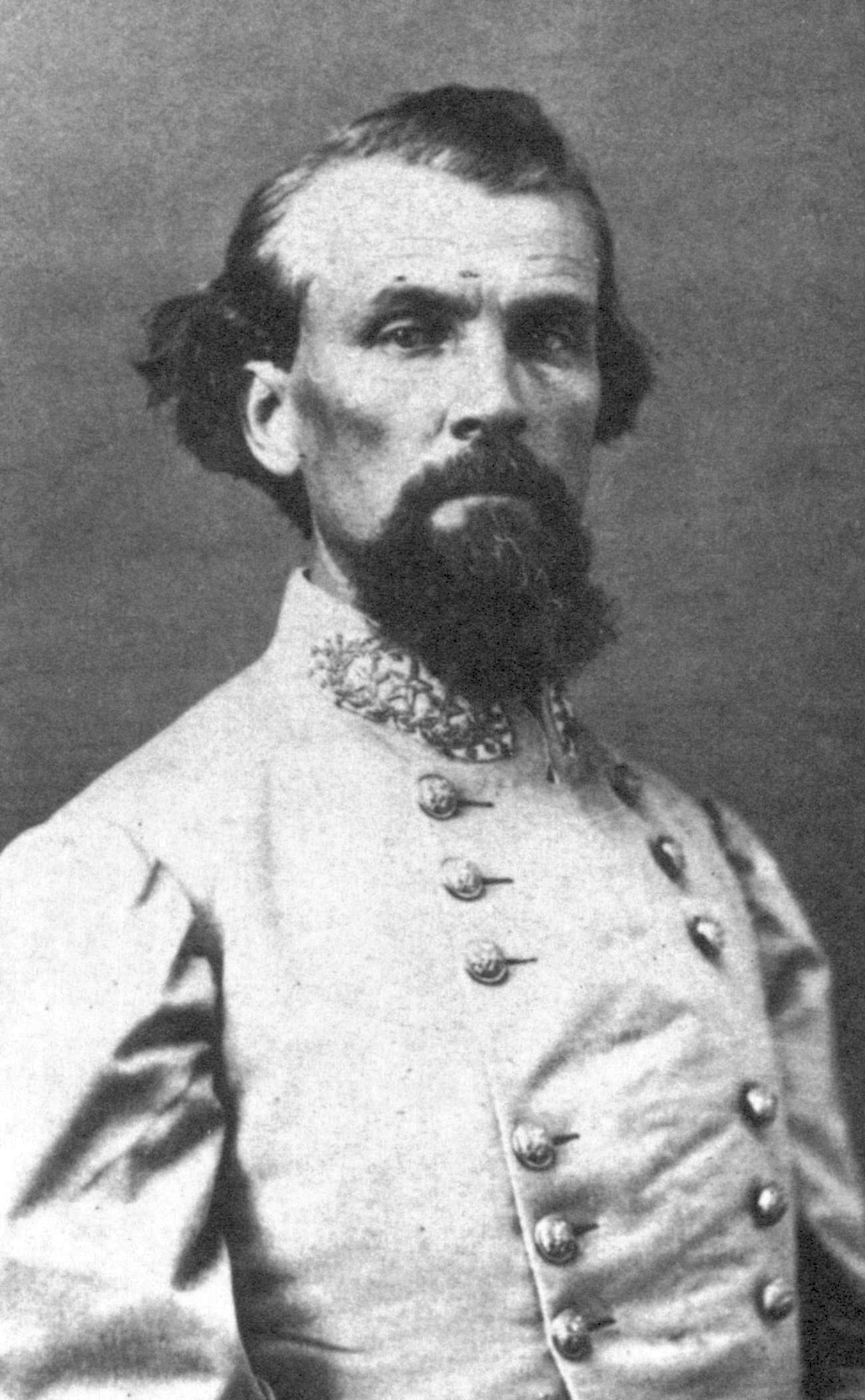

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was a prominent

Confederate Army general during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

and the first

Grand Wizard

The Grand Wizard (later the Grand and Imperial Wizard simplified as the Imperial Wizard and eventually, the National Director) referred to the national leader of several different Ku Klux Klan organizations in the United States and abroad.

The ti ...

of the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

from 1867 to 1869. Before the war, Forrest amassed substantial wealth as a cotton plantation owner, horse and cattle trader,

real estate broker

A real estate agent or real estate broker is a person who represents sellers or buyers of real estate or real property. While a broker may work independently, an agent usually works under a licensed broker to represent clients. Brokers and agen ...

, and

slave trader

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and Slavery and religion, religions from Ancient history, ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The socia ...

. In June 1861, he enlisted in the

Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

and became one of the few soldiers during the war to enlist as a

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

and be promoted to

general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

without any prior military training. An expert cavalry leader, Forrest was given command of a

corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was first named as such in 1805. The size of a corps varies great ...

and established new doctrines for mobile forces, earning the nickname "The Wizard of the Saddle". He used his cavalry troops as mounted infantry and often deployed artillery as the lead in battle, thus helping to "revolutionize cavalry tactics",

although the Confederate high command is seen by some commentators to have underappreciated his talents.

While scholars generally acknowledge Forrest's skills and acumen as a cavalry leader and military strategist, he has remained a controversial figure in Southern racial history for his main role in the massacre of several hundred Union soldiers at Fort Pillow, a majority of them black, coupled with his role following the war as a leader of the Klan.

In April 1864, in what has been called "one of the bleakest, saddest events of American military history",

troops under Forrest's command at the

Battle of Fort Pillow

The Battle of Fort Pillow, also known as the Fort Pillow massacre, was fought on April 12, 1864, at Fort Pillow on the Mississippi River in Henning, Tennessee, during the American Civil War. The battle ended with a massacre of Union soldiers ( ...

massacred hundreds of troops, composed of black soldiers and white Tennessean

Southern Loyalists fighting for the Union, who had already surrendered. Forrest was blamed for the slaughter in the Union press, and this news may have strengthened the North's resolve to win the war. Forrest's responsibility for the massacre continues to be actively debated by historians.

Forrest, who was a

Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

, joined the Ku Klux Klan in 1867 (two years after its founding) and was elected its first Grand Wizard. The group was a loose collection of local factions throughout the former Confederacy that used violence and the threat of violence to maintain white control over the newly enfranchised former slaves. The Klan, with Forrest at the lead, suppressed voting rights of blacks in the South through violence and intimidation during the

elections of 1868. In 1869, Forrest expressed disillusionment with the lack of discipline in the

white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

terrorist group across the South,

and issued a letter ordering the dissolution of the Ku Klux Klan as well as the destruction of its costumes; he then withdrew from the organization.

In the last years of his life, Forrest insisted he had never been a member,

and made public calls for black advancement.

In June 2021, the remains of Forrest and his wife were exhumed from Health Sciences Park, where they had been buried for over 100 years and a monument of him once stood. They were later reburied in

Columbia, Tennessee

Columbia is a city in and the county seat of Maury County, Tennessee. The population was 41,690 as of the 2020 United States census. Columbia is included in the Nashville metropolitan area.

The self-proclaimed "mule capital of the world," Colum ...

. In July 2021, Tennessee officials voted to move Forrest's bust from the State Capitol to the

Tennessee State Museum

The Tennessee State Museum is a large museum in Nashville depicting the history of the U.S. state of Tennessee. The current facility opened on October 4, 2018, at the corner of Rosa Parks Boulevard and Jefferson Street at the foot of Capitol Hill ...

.

Early life and career

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born on July 13, 1821, to a poor settler family in a secluded frontier cabin near

Chapel Hill Chapel Hill or Chapelhill may refer to:

Places Antarctica

* Chapel Hill (Antarctica) Australia

*Chapel Hill, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane

*Chapel Hill, South Australia, in the Mount Barker council area

Canada

* Chapel Hill, Ottawa, a neighbo ...

hamlet, then part of

Bedford County,

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, but now encompassed in

Marshall County.

Forrest was the first son of Mariam (Beck) and William Forrest. His blacksmith father was of English descent, and most of his biographers state that his mother was of

Scotch-Irish descent, but the Memphis Genealogical Society says that she was of English descent. He and his twin sister, Fanny, were the two eldest of 12 children. Their great-grandfather, Shadrach Forrest, moved between 1730 and 1740 from

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

to

North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, where his son and grandson were born; they moved to Tennessee in 1806. Forrest's family lived in a log house (now preserved as the

Nathan Bedford Forrest Boyhood Home

The Nathan Bedford Forrest Boyhood Home is a historic log house in Chapel Hill, Tennessee, U.S.. It was the childhood home of Confederate States of America, Confederate General and Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard Nathan Bedford Forrest from 1830 to 183 ...

) from 1830 to 1833.

John Allan Wyeth

John Allan Wyeth (May 26, 1845 – May 22, 1922) was an American Confederate veteran and surgeon. Born and raised on a Southern plantation in Alabama, he served in the Confederate States Army and completed his medical studies in New York City a ...

, who served in an Alabama regiment under Forrest, described it as a one-room building with a loft and no windows.

William Forrest worked as a blacksmith in Tennessee until 1834, when he moved with his family to

Salem, Mississippi

Salem is an extinct town in Benton County, Mississippi, United States.

History

Salem was settled in 1836 and incorporated in May 1837. At one point, Salem was home to twelve businesses, two hotels, and a female school.

Salem was destroyed by the ...

. William died in 1837 and Forrest became the primary caretaker of the family at age 16.

In 1841 Forrest went into business with his uncle Jonathan Forrest in

Hernando,

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. His uncle was killed there in 1845 during an argument with the Matlock brothers. In retaliation, Forrest shot and killed two of them with his two-shot pistol and wounded two others with a knife which had been thrown to him. One of the wounded Matlock men survived and served under Forrest during the Civil War.

Forrest had success as a businessman, planter and slaveholder. He acquired several

cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

in

the Delta region of

West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions (Tennessee), Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee River, Tennessee and Miss ...

, and became a

slave trader

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and Slavery and religion, religions from Ancient history, ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The socia ...

at a time when demand for slaves was booming in the Deep South; his slave trading business was based on Adams Street in

Memphis

Memphis most commonly refers to:

* Memphis, Egypt, a former capital of ancient Egypt

* Memphis, Tennessee, a major American city

Memphis may also refer to:

Places United States

* Memphis, Alabama

* Memphis, Florida

* Memphis, Indiana

* Memp ...

.

In 1858, Forrest was elected a Memphis city

alderman

An alderman is a member of a Municipal government, municipal assembly or council in many Jurisdiction, jurisdictions founded upon English law. The term may be titular, denoting a high-ranking member of a borough or county council, a council membe ...

as a

Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

and served two consecutive terms.

By the time the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

started in 1861, he had become one of the richest men in the

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

, having amassed a "personal fortune that he claimed was worth $1.5 million".

Forrest was well known as a Memphis speculator and Mississippi gambler. In 1859, he bought two large cotton plantations in

Coahoma County, Mississippi

Coahoma County is a county located in the U.S. state of Mississippi. As of the 2010 census, the population was 26,151. Its county seat is Clarksdale.

The Clarksdale, MS Micropolitan Statistical Area includes all of Coahoma County. It is loc ...

and a half-interest in another plantation in Arkansas;

by October 1860 he owned at least 3,345 acres in Mississippi.

Nathan Bedford Forrest was a tall man who stood in height and weighed about ;

He was noted as having a "striking and commanding presence" by Union Captain Lewis Hosea, an aide to Gen. James H. Wilson. Forrest rarely drank and abstained from tobacco usage; he was often described as generally mild mannered, but according to Hosea and other contemporaries who knew him, his demeanor changed drastically when he was provoked or angered.

He was known as a tireless rider in the saddle and a skilled

swordsman

Swordsmanship or sword fighting refers to the skills and techniques used in combat and training with any type of sword. The term is modern, and as such was mainly used to refer to smallsword fencing, but by extension it can also be applied to a ...

.

Although he was not formally educated, Forrest was able to read and write in clear and grammatical English.

Marriage and family

Forrest had twelve brothers and sisters; two of his eight brothers and three of his four sisters died of

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

at an early age, all at about the same time.

He also contracted the disease, but survived; his father recovered but died from residual effects of the disease five years later, when Bedford was 16. His mother Miriam then married James Horatio Luxton, of

Marshall, Texas

Marshall is a city in the U.S. state of Texas. It is the county seat of Harrison County, Texas, Harrison County and a cultural and educational center of the Ark-La-Tex region. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, the population of M ...

, in 1843 and gave birth to four more children.

In 1845, Forrest married Mary Ann Montgomery (1826–1893), the niece of a Presbyterian minister who was her legal guardian.

They had two children, William Montgomery Bedford Forrest (1846–1908), who enlisted at the age of 15 and served alongside his father in the war, and a daughter, Fanny (1849–1854), who died in childhood.

Forrest's grandson,

Nathan Bedford Forrest II

Nathan Bedford Forrest II (August 1871 – March 11, 1931) was an American businessman who served as the 19th Commander-in-Chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans from 1919 to 1921, and as the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan for Georgia. For ...

(1872–1931), became commander-in-chief of the

Sons of Confederate Veterans

The Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) is an American neo-Confederate nonprofit organization of male descendants of Confederate soldiers

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the militar ...

and a

Grand Dragon

Ku Klux Klan (KKK) nomenclature has evolved over the order's nearly 160 years of existence. The titles and designations were first laid out in the original Klan's prescripts of 1867 and 1868, then revamped with William J. Simmons's ''Kloran'' of 1 ...

of the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

in Georgia and secretary of the national organization. A great-grandson,

Nathan Bedford Forrest III (1905–1943), graduated from

West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

and rose to the rank of brigadier general in the

U.S. Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical ri ...

; he was killed during a bombing raid over

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in 1943, becoming the first American general to die in combat in the

European theater

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

during World War II.

[Hurst 2011, p. 387]

American Civil War

Early cavalry command

After the Civil War broke out, Forrest returned to Tennessee from his Mississippi ventures and enlisted in the

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

(CSA) on June 14, 1861. He reported for training at

Fort Wright near

Randolph, Tennessee

Randolph is a rural unincorporated community in Tipton County, Tennessee, United States, located on the banks of the Mississippi River. Randolph was founded in the 1820s and in 1827, the Randolph post office was established. In the 1830s, the tow ...

,

joining

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Josiah White's cavalry company, the Tennessee Mounted Rifles (Seventh Tennessee Cavalry), as a

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* " In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorde ...

along with his youngest brother and 15-year-old son. Upon seeing how badly equipped the CSA was, Forrest offered to buy horses and equipment with his own money for a

regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

of Tennessee volunteer soldiers.

His superior officers and

Governor of Tennessee

The governor of Tennessee is the head of government of the U.S. state of Tennessee. The governor is the only official in Tennessee state government who is directly elected by the voters of the entire state.

The current governor is Bill Lee, a ...

Isham G. Harris

Isham Green Harris (February 10, 1818July 8, 1897) was an American politician who served as the 16th governor of Tennessee from 1857 to 1862, and as a U.S. senator from 1877 until his death. He was the state's first governor from West Tennessee. ...

were surprised that someone of Forrest's wealth and prominence had enlisted as a soldier, especially since major planters were exempted from service. They commissioned him as a

lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

and authorized him to recruit and train a battalion of Confederate mounted rangers.

In October 1861, Forrest was given command of a regiment, the 3rd Tennessee Cavalry. Though Forrest had no prior formal

military training

Military education and training is a process which intends to establish and improve the capabilities of military personnel in their respective roles. Military training may be voluntary or compulsory duty. It begins with recruit training, proceed ...

or experience, he had exhibited leadership and soon proved he could successfully employ

tactics

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

** Political tact ...

.

Public debate surrounded

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

's decision to join the Confederacy and both the Confederate and

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

armies recruited soldiers from the state. More than 100,000 men from Tennessee served with the Confederacy and over 31,000 served with the Union.

Forrest posted advertisements to join his regiment, with the slogan, "Let's have some fun and kill some Yankees!". Forrest's command included his Escort Company (his "Special Forces"), for which he selected the best soldiers available. This unit, which varied in size from 40 to 90 men, constituted the elite of his cavalry.

Sacramento and Fort Donelson

Forrest won praise for his performance under fire during an early victory in the

Battle of Sacramento

The Battle of the Sacramento River was a battle that took place on February 28, 1847 during the Mexican–American War. About fifteen miles north of Chihuahua, Mexico at the crossing of the river Sacramento, American forces numbering less th ...

in

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, the first in which he commanded troops in the field, where he routed a Union force by personally leading a cavalry charge that was later commended by his commander, Brigadier General

Charles Clark.

Forrest distinguished himself further at the

Battle of Fort Donelson

The Battle of Fort Donelson was fought from February 11–16, 1862, in the Western Theater of the American Civil War. The Union capture of the Confederate fort near the Tennessee–Kentucky border opened the Cumberland River, an important ave ...

in February 1862. After his cavalry captured a Union

artillery battery

In military organizations, an artillery battery is a unit or multiple systems of artillery, mortar systems, rocket artillery, multiple rocket launchers, surface-to-surface missiles, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, etc., so grouped to fac ...

, he broke out of a

siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

headed by

Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, rallying nearly 4,000 troops and leading them to escape across the

Cumberland River

The Cumberland River is a major waterway of the Southern United States. The U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 8, 2011 river drains almost of southern Kentucky and ...

.

A few days after the Confederate surrender of Fort Donelson, with the fall of

Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and the ...

to Union forces imminent, Forrest took command of the city. All available carts and wagons were pressed into service to haul six hundred boxes of army clothing, 250,000 pounds of bacon and forty wagon-loads of ammunition to the railroad depots, to be sent off to Chattanooga and Decatur.

Forrest arranged for heavy

ordnance

Ordnance may refer to:

Military and defense

*Materiel in military logistics, including weapons, ammunition, vehicles, and maintenance tools and equipment.

**The military branch responsible for supplying and developing these items, e.g., the Unit ...

machinery, including a new cannon rifling machine and fourteen cannons, as well as parts from the Nashville Armory, to be sent to Atlanta for use by the Confederate Army.

Shiloh and Murfreesboro

A month later, Forrest was back in action at the

Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

, fought April 6–7, 1862. He commanded a Confederate

rear guard

A rearguard is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an army. Even more ...

after the Union victory. In the battle of

Fallen Timbers

The Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) was the final battle of the Northwest Indian War, a struggle between Indigenous peoples of North America, Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their Kingdom of Gre ...

, he drove through the Union

skirmish line

Skirmishers are light infantry or light cavalry soldiers deployed as a vanguard, flank guard or rearguard to screen a tactical position or a larger body of friendly troops from enemy advances. They are usually deployed in a skirmish line, an ir ...

. Not realizing that the rest of his men had halted their charge when they reached the full Union brigade, Forrest charged the brigade alone and soon found himself surrounded. He emptied his Colt Army revolvers into the swirling mass of Union soldiers and pulled out his saber, hacking and slashing. A Union

infantryman

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

on the ground beside Forrest fired a musket ball at him with a point-blank shot, nearly knocking him out of the saddle. The ball went through Forrest's pelvis and lodged near his spine. A surgeon removed the musket ball a week later, without anesthesia, which was unavailable.

By early summer, Forrest commanded a new brigade of inexperienced cavalry regiments. In July, he led them into Middle Tennessee under orders to launch a cavalry raid, and on July 13, 1862, led them into the

First Battle of Murfreesboro, as a result of which all of the Union units surrendered to Forrest, and the Confederates destroyed much of the Union's supplies and railroad track in the area.

West Tennessee raids

Promoted on July 21, 1862, to

brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

, Forrest was given command of a Confederate cavalry brigade.

[.] In December 1862, Forrest's veteran troopers were reassigned by General

Braxton Bragg

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was an American army officer during the Second Seminole War and Mexican–American War and Confederate general in the Confederate Army during the American Civil War, serving in the Weste ...

to another officer, against his protest. Forrest had to recruit a new brigade, composed of about 2,000 inexperienced recruits, most of whom lacked weapons.

Again, Bragg ordered a series of raids to disrupt the communications of the Union forces under Grant, which were threatening the city of

Vicksburg, Mississippi

Vicksburg is a historic city in Warren County, Mississippi, United States. It is the county seat, and the population at the 2010 census was 23,856.

Located on a high bluff on the east bank of the Mississippi River across from Louisiana, Vic ...

. Forrest protested that to send such untrained men behind enemy lines was suicidal, but Bragg insisted, and Forrest obeyed his orders. In the ensuing raids he was pursued by thousands of Union soldiers trying to locate his fast-moving forces. Avoiding attack by never staying in one place long, eventually Forrest led his troops during the spring and summer of 1864 on

raids into west Tennessee, as far north as the banks of the

Ohio River

The Ohio River is a long river in the United States. It is located at the boundary of the Midwestern and Southern United States, flowing southwesterly from western Pennsylvania to its mouth on the Mississippi River at the southern tip of Illino ...

in southwest Kentucky and into north Mississippi.

Forrest returned to his base in Mississippi with more men than he had started with. By then, all were fully armed with captured Union weapons. As a result, Grant was forced to revise and delay the strategy of his

Vicksburg campaign

The Vicksburg campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in the Western Theater of the American Civil War directed against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a fortress city that dominated the last Confederate-controlled section of the Mississippi Riv ...

. Newspaper correspondent Sylvanus Cadwallader, who traveled with Grant for three years during his campaigns, wrote that Forrest "was the only Confederate cavalryman of whom Grant stood in much dread".

Dover, Brentwood, and Chattanooga

The Union Army gained military control of Tennessee in 1862 and occupied it for the duration of the war, having taken control of strategic cities and railroads. Forrest continued to lead his men in small-scale operations, including the

Battle of Dover The Battle of Dover may refer to:

* Battle of Sandwich (1217), also known as Battle of Dover, 24 August 1217, a naval engagement between England and France in the First Barons' War

* Battle of Dover (1652), 29 May 1652, in the First Anglo-Dutch War ...

and the

Battle of Brentwood

The Battle of Brentwood was a battle during the American Civil War on March 25, 1863, in Williamson County, Tennessee at Brentwood, Tennessee.

Battle

Union Lt. Col. Edward Bloodgood held Brentwood, a station on the Nashville & Decatur Railro ...

until April 1863. The Confederate army dispatched him with a small force into the

backcountry

In the United States, a backcountry or backwater is a geographical area that is remote, undeveloped, isolated, or difficult to access.

Terminology Backcountry and wilderness within United States national parks

The National Park Service (NPS) ...

of northern

Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

and western

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

to defend against an attack of 3,000 Union cavalrymen commanded by Colonel

Abel Streight

Abel Delos Streight (June 17, 1828 – May 27, 1892) was a peacetime lumber merchant and publisher, and was a Union Army colonel in the American Civil War. His command precipitated a notable cavalry raid in 1863, known as Streight's Raid. He ...

. Streight had orders to cut the Confederate railroad south of

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

to seal off Bragg's supply line and force him to retreat into Georgia.

Forrest chased Streight's men for 16 days, harassing them all the way. Streight's goal changed from dismantling the railroad to escaping the pursuit. On May 3, Forrest caught up with Streight's unit east of

Cedar Bluff, Alabama

Cedar Bluff is a town in Cherokee County, Alabama, United States. At the 2020 census, the population was 1,845. Unlike the rest of the county, Cedar Bluff is a wet town. Cedar Bluff is located on the north shore of Weiss Lake, noted for its cra ...

. Forrest had fewer men than the Union side but feigned having a larger force by parading some repeatedly around a hilltop until Streight was convinced to surrender his 1,500 or so exhausted troops (historians Kevin Dougherty and Keith S. Hebert say he had about 1,700 men).

Day's Gap, Chickamauga, and Paducah

Not all of Forrest's exploits of individual combat involved enemy troops. Lieutenant Andrew Wills Gould, an artillery officer in Forrest's command, was being transferred, presumably because cannons under his command were

spiked

Spiked may refer to:

* A drink to which alcohol, recreational drugs, or a date rape drug has been added

** Spiked seltzer, seltzer with alcohol

**Mickey Finn (drugs) In slang, a Mickey Finn (or simply a Mickey) is a drink laced with an incapacitati ...

(disabled) by the enemy during the

Battle of Day's Gap

The Battle of Day's Gap, fought on April 30, 1863, was the first in a series of American Civil War skirmishes in Cullman County, Alabama, that lasted until May 2, known as Streight's Raid. Commanding the Union forces was Col. Abel Streight; B ...

. On June 13, 1863, Gould confronted Forrest about his transfer, which escalated into a violent exchange. Gould shot Forrest in the hip and Forrest mortally stabbed Gould.

Forrest was thought to have been fatally wounded by Gould but he recovered and was ready to fight in the Chickamauga Campaign.

Forrest served with the main army at the

Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought on September 19–20, 1863, between United States, U.S. and Confederate States of America, Confederate forces in the American Civil War, marked the end of a Union Army, Union offensive, the Chickamauga Campaign ...

on September 18–20, 1863, in which he pursued the retreating Union army and took hundreds of prisoners. Like several others under Bragg's command, he urged an immediate follow-up attack to recapture Chattanooga, which had fallen a few weeks before. Bragg failed to do so, upon which Forrest was quoted as saying, "What does he fight battles for?"

The story that Forrest confronted and threatened the life of Bragg in the fall of 1863, following the battle of Chickamauga, and that Bragg transferred Forrest to command in Mississippi as a direct result, is now considered to be

apocryphal

Apocrypha are works, usually written, of unknown authorship or of doubtful origin. The word ''apocryphal'' (ἀπόκρυφος) was first applied to writings which were kept secret because they were the vehicles of esoteric knowledge considered ...

.

On December 4, 1863, Forrest was promoted to the rank of

major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

.

[.] On March 25, 1864, Forrest's cavalry raided the town of

Paducah, Kentucky

Paducah ( ) is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of McCracken County, Kentucky. The largest city in the Jackson Purchase region, it is located at the confluence of the Tennessee and the Ohio rivers, halfway between St. Louis, Missour ...

in the

Battle of Paducah

The Battle of Paducah was fought on March 25, 1864, during the American Civil War. A Confederate cavalry force led by Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest moved into Tennessee and Kentucky to capture Union supplies. Tennessee had been occupied by Un ...

, during which Forrest demanded the surrender of U.S. Colonel

Stephen G. Hicks

Stephen G. Hicks (February 22, 1809 – December 14, 1869 (or 1866)) was an American soldier alf Cherokee Indian born in Jackson County, Georgia. His father, John Hicks, was one of the seven soldiers killed in action at the Battle of New Orleans. ...

: "if I have to storm your works, you may expect no quarter." Hicks refused to comply with the ultimatum, and according to his subsequent report, Forrest's troops took a position and set up a battery of guns while a flag of truce was still up. As soon as they received the Union reply, they moved forward at the command of a junior officer, and the Union forces opened fire. The Confederates tried to storm the fort, but were repulsed; they rallied and made two more attempts, both of which failed.

Fort Pillow massacre

Fort Pillow, located upriver from Memphis (near

Henning, Tennessee

Henning is a town in Lauderdale County, Tennessee. The population was 945 at the 2010 census.

History

The infamous Battle of Fort Pillow, a Civil War victory for the Confederates, took place near Henning. Here, nearly 300 black troops serving in ...

), was originally constructed by Confederate general

Gideon Johnson Pillow

Gideon Johnson Pillow (June 8, 1806 – October 8, 1878) was an American lawyer, politician, speculator, slaveowner, United States Army major general of volunteers during the Mexican–American War and Confederate brigadier general in the Americ ...

on the bluffs of the Mississippi River, and taken over by Union forces in 1862 after the Confederates had abandoned the fort. The fort was manned by 557 Union troops, 295 white and 262 black, under Union commander Maj. L.F. Booth.

On April 12, 1864, Forrest's men, under Brig. Gen. James Chalmers, attacked and recaptured Fort Pillow. Booth and his adjutant were killed in the battle, leaving Fort Pillow under the command of Major William Bradford. Forrest had reached the fort at 10:00 am after a hard ride from Mississippi, and his horse was soon shot out from under him, causing him to fall to the ground. He then mounted a second horse, which was shot out from under him as well, forcing him to mount a third horse. By 3:30 pm, Forrest had concluded that the Union troops could not hold the fort, thus he ordered a flag of truce raised and demanded that the fort be surrendered. Bradford refused to surrender, believing his troops could escape to the Union gunboat,

USS ''New Era'', on the Mississippi River. Forrest's men immediately took over the fort, while Union soldiers retreated to the lower bluffs of the river, but the USS ''New Era'' did not come to their rescue. What happened next became known as the Fort Pillow Massacre. As the Union troops surrendered, Forrest's men opened fire, slaughtering both black and white soldiers.

According to historians John Cimprich and Bruce Tap, although their numbers were roughly equal, two thirds of the black Union soldiers were killed, while only a third of the whites were killed.

The atrocities at Fort Pillow continued throughout the night. Conflicting accounts of what actually occurred were given later.

Forrest's Confederate forces were accused of subjecting Union captured soldiers to extreme brutality, with allegations of back-shooting soldiers who fled into the river, shooting wounded soldiers, burning men alive, nailing men to barrels and igniting them,

crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

, and hacking men to death with sabers. Forrest's men were alleged to have set fire to a Union

barracks

Barracks are usually a group of long buildings built to house military personnel or laborers. The English word originates from the 17th century via French and Italian from an old Spanish word "barraca" ("soldier's tent"), but today barracks are u ...

with wounded Union soldiers inside

In defense of their actions, Forrest's men insisted that the Union soldiers, although fleeing, kept their weapons and frequently turned to shoot, forcing the Confederates to keep firing in

self-defense

Self-defense (self-defence primarily in Commonwealth English) is a countermeasure that involves defending the health and well-being of oneself from harm. The use of the right of self-defense as a legal justification for the use of force in ...

.

[.] The rebels said the Union flag was still flying over the fort, which indicated that the force had not formally surrendered. A contemporary newspaper account from

Jackson, Tennessee

Jackson is a city in and the county seat of Madison County, Tennessee, United States. Located east of Memphis, Tennessee, Memphis, it is a regional center of trade for West Tennessee. Its total population was 68,205 as of the 2020 United States ...

stated that "General Forrest begged them to surrender" but "not the first sign of surrender was ever given". Similar accounts were reported in many Southern newspapers at the time. These statements, however, were contradicted by Union survivors, as well as by the letter of a Confederate soldier who graphically recounted a massacre. Achilles Clark, a soldier with the 20th Tennessee cavalry, wrote to his sisters immediately after the battle:

Following the cessation of hostilities, Forrest transferred the 14 most seriously wounded United States Colored Troops (USCT) to the U.S. steamer ''Silver Cloud''. The 226 Union troops taken prisoner at Fort Pillow were marched under guard to

Holly Springs, Mississippi

Holly Springs is a city in, and the county seat of, Marshall County, Mississippi, United States, near the southern border of Tennessee. Near the Mississippi Delta, the area was developed by European Americans for cotton plantations and was dep ...

and then convoyed to

Demopolis, Alabama

Demopolis is the largest city in Marengo County, in west-central Alabama. The population was 7,162 at the time of the 2020 United States census, down from 7,483 at the 2010 census.

The city lies at the confluence of the Black Warrior River and T ...

. On April 21, Capt. John Goodwin, of Forrest's cavalry command, forwarded a dispatch listing the prisoners captured. The list included the names of 7 officers and 219 white enlisted soldiers. According to Richard L. Fuchs, "records concerning the fate of the black prisoners are either nonexistent or unreliable".

President

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

asked his cabinet for opinions as to how the Union should respond to the massacre.

At the time of the massacre, General Grant was no longer in Tennessee but had transferred to the east to command all Union troops. He wrote in his

memoirs

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobiog ...

that Forrest in his report of the battle had "left out the part which shocks humanity to read".

Because of the events at Fort Pillow, the Northern public and press viewed Forrest as a war criminal. The ''Chicago Tribune'' said Forrest and his brothers were "slave drivers and woman whippers", while Forrest himself was described as "mean, vindictive, cruel, and unscrupulous". The Southern press steadfastly defended Forrest's reputation.

writes, "Forrest's responsibility for the massacre has been actively debated for a century and a half. ... No direct evidence suggests that he ordered the shooting of surrendering or unarmed men, but to fully exonerate him from responsibility is also impossible".

Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo

Forrest's most decisive victory came on June 10, 1864, when his 3,500-man force clashed with 8,500 men commanded by Union Brig. Gen.

Samuel D. Sturgis at the

Battle of Brices Crossroads in northeastern

Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

.

Here, the mobility of the troops under his command and his superior tactics led to victory,

allowing him to continue harassing Union forces in southwestern Tennessee and northern Mississippi throughout the war.

Forrest set up a position for an attack to repulse a pursuing force commanded by Sturgis, who had been sent to impede Forrest from destroying Union supply lines and fortifications.

When Sturgis's Federal army came upon the crossroads, they collided with Forrest's cavalry. Sturgis ordered his infantry to advance to the front line to counteract the cavalry. The infantry, tired, weary and suffering under the heat, were quickly broken and sent into mass retreat. Forrest sent a full charge after the retreating army and captured 16 artillery pieces, 176 wagons and 1,500 stands of small arms. In all, the maneuver cost Forrest 96 men killed and 396 wounded. The day was worse for Union troops, who suffered 223 killed, 394 wounded and 1,623 missing. The losses were a deep blow to the black regiment under Sturgis's command. In the hasty retreat, they stripped off commemorative badges that read "Remember Fort Pillow" to avoid goading the Confederate force pursuing them.

One month later, while serving under General

Stephen D. Lee

Stephen Dill Lee (September 22, 1833 – May 28, 1908) was an American officer in the Confederate Army, politician and first president of Mississippi State University from 1880 to 1899. He served as lieutenant general of the Confederate ...

, Forrest experienced

tactical defeat at the

Battle of Tupelo

The Battle of Tupelo, also known as the Engagement at Harrisburg, was a battle of the American Civil War fought from July 14 to 15, 1864, near Tupelo, Mississippi. The Union victory over Confederate forces in northeast Mississippi ensured the ...

in 1864.

Concerned about Union supply lines, Maj. Gen. Sherman sent a force under the command of Maj. Gen.

Andrew J. Smith to deal with Forrest.

Union forces drove the Confederates from the field and Forrest was wounded in the foot, but his forces were not wholly destroyed.

He continued to oppose Union efforts in the West for the remainder of the war.

Tennessee Raids

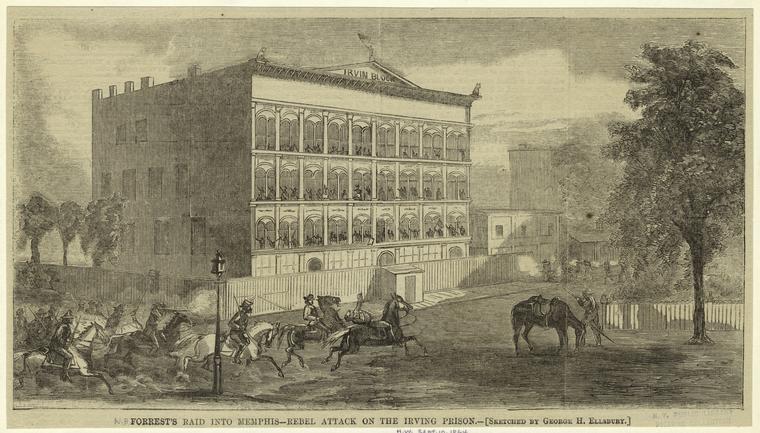

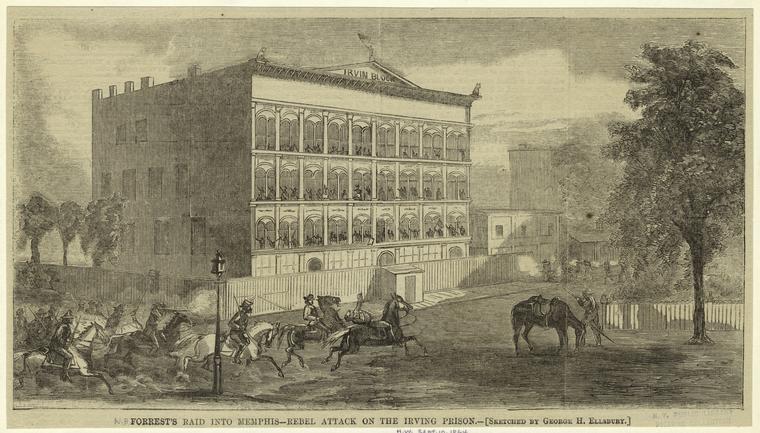

Forrest led other raids that summer and fall, including a famous one into Union-held downtown Memphis in August 1864 (the

Second Battle of Memphis

The Second Battle of Memphis was a battle of the American Civil War occurring on August 21, 1864, in Shelby County, Tennessee.

Battle

At 4:00 a.m. on August 21, 1864, Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest made a daring raid on Union-held M ...

)

and another on a major Union supply depot at

Johnsonville, Tennessee. On November 4, 1864, during the

Battle of Johnsonville

The Battle of Johnsonville was fought November 4–5, 1864, in Benton and Humphreys counties, Tennessee, during the American Civil War. Confederate cavalry commander Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest culminated a 23-day raid through western ...

, the Confederates shelled the city, sinking three gunboats and nearly thirty other ships and destroying many tons of supplies.

During

Hood's Tennessee Campaign, he fought alongside General

John Bell Hood

John Bell Hood (June 1 or June 29, 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Although brave, Hood's impetuosity led to high losses among his troops as he moved up in rank. Bruce Catton wrote that "the dec ...

, the newest commander of the Confederate

Army of Tennessee

The Army of Tennessee was the principal Confederate army operating between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River during the American Civil War. It was formed in late 1862 and fought until the end of the war in 1865, participating i ...

, in the

Second Battle of Franklin

The Second Battle of Franklin was fought on November 30, 1864, in Franklin, Tennessee, as part of the Franklin–Nashville Campaign of the American Civil War. It was one of the worst disasters of the war for the Confederate States Army. Confede ...

on November 30.

Facing a disastrous defeat, Forrest argued bitterly with Hood (his

superior officer

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer, or a warrant officer. However, absent contextu ...

) demanding permission to cross the

Harpeth River

The Harpeth River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed June 8, 2011 is one of the major streams of north-central Middle Tennessee, United States, and one of the major ...

and cut off the escape route of Union Maj. Gen.

John M. Schofield

John McAllister Schofield (September 29, 1831 – March 4, 1906) was an American soldier who held major commands during the American Civil War. He was appointed U.S. Secretary of War (1868–1869) under President Andrew Johnson and later served a ...

's army.

He eventually made the attempt, but it was too late.

Murfreesboro, Nashville, and Selma

After his bloody defeat at Franklin, Hood continued on to Nashville. Hood ordered Forrest to conduct an independent raid against the

Murfreesboro

Murfreesboro is a city in and county seat of Rutherford County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 152,769 according to the 2020 census, up from 108,755 residents certified in 2010. Murfreesboro is located in the Nashville metropol ...

garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

. After success in achieving the objectives specified by Hood, Forrest engaged Union forces near Murfreesboro on December 5, 1864. In what would be known as the

Third Battle of Murfreesboro

The Third Battle of Murfreesboro, also known as Wilkinson Pike or the Cedars, was fought December 5–7, 1864, in Rutherford County, Tennessee, as part of the Franklin-Nashville Campaign of the American Civil War.

Background

In a last, des ...

, a portion of Forrest's command broke and ran.

When Hood's battle-hardened Army of Tennessee, consisting of 40,000 men deployed in three infantry corps plus 10,000 to 15,000 cavalry, was all but destroyed on December 15–16, at the

Battle of Nashville

The Battle of Nashville was a two-day battle in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign that represented the end of large-scale fighting west of the coastal states in the American Civil War. It was fought at Nashville, Tennessee, on December 15–16, 1 ...

,

Forrest distinguished himself by commanding the Confederate rear guard in a series of actions that allowed what was left of the army to escape. For this, he would later be promoted to the rank of

lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

on March 2, 1865.

A portion of his command, now dismounted, was surprised and captured in their camp at

Verona, Mississippi

Verona is a city in Lee County, Mississippi. The population was 2,792 at the 2020 census, down from 3,006 at the 2010 census.

Geography

Verona is located at (34.188350, -88.718083).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a ...

on December 25, 1864, during a raid of the

Mobile and Ohio Railroad

The Mobile and Ohio Railroad was a railroad in the Southern U.S. The M&O was chartered in January and February 1848 by the states of Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Tennessee. It was planned to span the distance between the seaport of Mobile ...

by a brigade of Brig. Gen.

Benjamin Grierson

Benjamin Henry Grierson (July 8, 1826 – August 31, 1911) was a music teacher, then a career officer in the United States Army. He was a cavalry general in the volunteer Union Army during the Civil War and later led troops in the American O ...

's cavalry division.

In the spring of 1865, Forrest led an unsuccessful defense of the state of Alabama against

Wilson's Raid

Wilson's Raid was a cavalry operation through Alabama and Georgia in March–April 1865, late in the American Civil War. Brig. Gen. James H. Wilson led his Union Army Cavalry Corps to destroy Southern manufacturing facilities and was opposed ...

. His opponent, Brig. Gen.

James H. Wilson

James Harrison Wilson (September 2, 1837 – February 23, 1925) was a United States Army topographic engineer and a Union Army Major General in the American Civil War. He served as an aide to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan during the Maryland Camp ...

, defeated Forrest at the

Battle of Selma

The Battle of Selma, Alabama (April 2, 1865), formed part of the Union campaign through Alabama and Georgia, known as Wilson's Raid, in the final full month of the American Civil War.

Union Army forces under Major General James H. Wilson, tot ...

on April 2, 1865.

A week later, General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Grant in Virginia. When he received news of Lee's surrender, Forrest surrendered as well. On May 9, 1865, at

Gainesville, Forrest read his

farewell address to the men under his command, enjoining them to "submit to the powers to be, and to aid in restoring peace and establishing law and order throughout the land."

Postwar years and later life

Business ventures

As a former

slave trader

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and Slavery and religion, religions from Ancient history, ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The socia ...

and slave owner, Forrest experienced the

abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

at war's end as a major financial setback. He had become interested in the area around

Crowley's Ridge

Crowley's Ridge (also Crowleys Ridge) is a geological formation that rises 250 to above the alluvial plain of the Mississippi embayment in a line from southeastern Missouri to the Mississippi River near Helena, Arkansas. It is the most prom ...

during the war, and took up civilian life in 1865 in Memphis, Tennessee. In 1866, Forrest and C.C. McCreanor contracted to finish the Memphis & Little Rock Railroad, including a

right-of-way

Right of way is the legal right, established by grant from a landowner or long usage (i.e. by prescription), to pass along a specific route through property belonging to another.

A similar ''right of access'' also exists on land held by a gov ...

that passed over the ridge. The ridgetop

commissary

A commissary is a government official charged with oversight or an ecclesiastical official who exercises in special circumstances the jurisdiction of a bishop.

In many countries, the term is used as an administrative or police title. It often c ...

he built as a provisioning store for the 1,000 Irish laborers hired to lay the rails became the nucleus of a town, which most residents called "Forrest's Town" and which was incorporated as

Forrest City, Arkansas

Forrest City is a city in St. Francis County, Arkansas, United States, and the county seat. It was named for General Nathan Bedford Forrest, who used the location as a campsite for a construction crew completing a railroad between Memphis and Lit ...

in 1870.

The historian Court Carney writes that Forrest was not universally popular in the white Memphis community: he alienated many of the city's businessmen in his commercial dealings and he was criticized for questionable business practices that caused him to default on debts.

He later found employment at the

Selma

Selma may refer to:

Places

*Selma, Algeria

*Selma, Nova Scotia, Canada

*Selma, Switzerland, village in the Grisons

United States:

*Selma, Alabama, city in Dallas County, best known for the Selma to Montgomery marches

*Selma, Arkansas

*Selma, Cali ...

-based Marion & Memphis Railroad and eventually became the company president. He was not as successful in railroad promoting as in war and, under his direction, the company went

bankrupt

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the debt ...

. Nearly ruined as the result of this failure, Forrest spent his final days running an eight-hundred acre farm on land he leased on

President's Island

President's Island is a peninsula on the Mississippi River in southwest Memphis, Tennessee. The city's major river port and an industrial park are located there.

History

The name ''President'' or ''President's'' Island appeared as early as 1801 o ...

in the Mississippi River, where he and his wife lived in a

log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a less finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first generation home building by settlers.

Eur ...

. There, with the labor of over a hundred prison convicts, he grew corn, potatoes, vegetables and cotton profitably, but his health was in steady decline.

Offers his services to Sherman

During the

''Virginius'' Affair of 1873, some of Forrest's old Southern friends were

filibusters aboard the vessel; consequently, he wrote a letter to the then General-in-Chief of the United States Army William T. Sherman and offered his services in case a war were to break out between the United States and Spain. Sherman, who had recognized how formidable an opponent Forrest was in battle during the Civil War, replied after the crisis settled down. He thanked Forrest for the offer and stated that had war broken out, he would have considered it an honor to have served side by side with him.

[Davison 2016, pp. 474–475]

Ku Klux Klan membership

Forrest was an early member of the

Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

(KKK), which was formed by six veterans of the Confederate Army in

Pulaski, Tennessee

Pulaski is a city in and the county seat of Giles County, which is located on the central-southern border of Tennessee, United States. The population was 8,397 at the 2020 census. It was named after Casimir Pulaski, a noted Polish-born soldier o ...

, during the spring of 1866

and soon expanded throughout the state and beyond. Forrest became involved sometime in late 1866 or early 1867. A common report is that Forrest arrived in Nashville in April 1867 while the Klan was meeting at the

Maxwell House Hotel

The Maxwell House Hotel was a major hotel in downtown Nashville. Because of its stature, seven US Presidents and other prominent guests stayed there over the years. It was built by Colonel John Overton Jr. and named for his wife, Harriet (Maxwell) ...

, probably at the encouragement of a state Klan leader, former Confederate general

George Gordon. The organization had grown to the point that an experienced commander was needed, and Forrest was well-suited to assume the role. In Room 10 of the Maxwell, Forrest was sworn in as a member by

John W. Morton.

Brian Steel Wills quotes two KKK members who identified Forrest as a Klan leader.

James R. Crowe stated, "After the order grew to large numbers we found it necessary to have someone of large experience to command. We chose General Forrest".

Another member wrote, "N. B. Forest of Confederate fame was at our head, and was known as the Grand Wizard. I heard him make a speech in one of our Dens".

The title "

Grand Wizard

The Grand Wizard (later the Grand and Imperial Wizard simplified as the Imperial Wizard and eventually, the National Director) referred to the national leader of several different Ku Klux Klan organizations in the United States and abroad.

The ti ...

" was chosen because General Forrest had been known as "The Wizard of the Saddle" during the war.

According to Jack Hurst's 1993 biography, "Two years after

Appomattox, Forrest was reincarnated as grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. As the Klan's first national leader, he became the

Lost Cause

The Lost Cause of the Confederacy (or simply Lost Cause) is an American pseudohistorical negationist mythology that claims the cause of the Confederate States during the American Civil War was just, heroic, and not centered on slavery. First ...

's avenging angel, galvanizing a loose collection of boyish secret social clubs into a reactionary instrument of terror still feared today." Forrest was the Klan's first and only Grand Wizard, and he was active in recruitment for the Klan from 1867 to 1868.

Following the war, the United States Congress began passing the

Reconstruction Acts

The Reconstruction Acts, or the Military Reconstruction Acts, (March 2, 1867, 14 Stat. 428-430, c.153; March 23, 1867, 15 Stat. 2-5, c.6; July 19, 1867, 15 Stat. 14-16, c.30; and March 11, 1868, 15 Stat. 41, c.25) were four statutes passed duri ...

to specify conditions for the readmission of former Confederate States to the Union,

including ratification of the

Fourteenth (1868), and

Fifteenth

In music, a fifteenth or double octave, abbreviated ''15ma'', is the interval between one musical note and another with one-quarter the wavelength or quadruple the frequency. It has also been referred to as the bisdiapason. The fourth harmonic, ...

(1870) Amendments to the United States Constitution. The Fourteenth addressed citizenship rights and equal protection of the laws for former slaves, while the Fifteenth specifically secured the voting rights of black men.

According to Wills, in the August 1867 state elections the Klan was relatively restrained in its actions. White Americans who made up the KKK hoped to persuade black voters that a return to their pre-war state of bondage was in their best interest. Forrest assisted in maintaining order. It was after these efforts failed that Klan violence and intimidation escalated and became widespread. Author Andrew Ward, however, writes, "In the spring of 1867, Forrest and his dragoons launched a campaign of midnight parades; 'ghost' masquerades; and 'whipping' and even 'killing Negro voters and white Republicans, to scare blacks off voting and running for office.

In an 1868 interview by a

Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

newspaper, Forrest claimed that the Klan had 40,000 members in

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

and 550,000 total members throughout the Southern states.

He said he sympathized with them, but denied any formal connection, although he claimed he could muster thousands of men himself. He described the Klan as "a protective political military organization ... The members are sworn to recognize the government of the United States ... Its objects originally were protection against

Loyal Leagues

The Union Leagues were quasi-secretive men’s clubs established separately, starting in 1862, and continuing throughout the Civil War (1861–1865). The oldest Union League of America council member, an organization originally called "The Leag ...

and the

Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (U.S. Navy), and the Marines who served in the American Civil War. It was founded in 1866 in Decatur, Il ...

...".

After only a year as Grand Wizard, in January 1869, faced with an ungovernable membership employing methods that seemed increasingly counterproductive, Forrest dissolved the Klan, ordered their costumes destroyed, and withdrew from participation. His declaration had little effect, and few Klansmen destroyed their robes and hoods.

In 1871, the

''U.S Congressional Committee Report'' stated that "The natural tendency of all such organizations is to violence and crime, hence it was that Gen. Forrest and other men of influence by the exercise of their moral power, induced them to disband".

Democratic convention 1868

The Klan's activity infiltrated the

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

's campaign for the

presidential election of 1868. Prominent ex-Confederates, including Forrest, the Grand Wizard of the Klan, and South Carolina's

Wade Hampton Wade Hampton may refer to the following people:

People

*Wade Hampton I (1752–1835), American soldier in Revolutionary War and War of 1812 and U.S. congressman

*Wade Hampton II (1791–1858), American plantation owner and soldier in War of 1812

*W ...

, attended as delegates at the 1868 Democratic Convention, held at

Tammany Hall

Tammany Hall, also known as the Society of St. Tammany, the Sons of St. Tammany, or the Columbian Order, was a New York City political organization founded in 1786 and incorporated on May 12, 1789 as the Tammany Society. It became the main loc ...

headquarters at 141 East 14th Street in New York City. Forrest rode to the convention on a train that stopped in a small Northern town along the way, where he faced a protester who wanted to fight the "damned butcher" of Fort Pillow. Former Governor of New York

Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

was nominated as the Democratic presidential candidate, while Forrest's friend,

Frank Blair, Jr. was nominated as the Democratic vice presidential candidate, Seymour's running mate. The Seymour–Blair Democratic ticket's campaign slogan was: "Our Ticket, Our Motto, This Is a White Man's Country; Let White Men Rule". The Democratic Party platform denounced the Reconstruction Acts as unconstitutional, void, and revolutionary. The party advocated termination of the Freedman's Bureau and any government policy designed to aid blacks in the South. These developments worked to the advantage of the Republicans, who focused on the Democratic Party's alleged disloyalty during and after the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

.

Election of 1868 and Grant

During the presidential election of 1868, the Ku Klux Klan under the leadership of Forrest, along with other terrorist groups, used brutal violence and intimidation against blacks and Republican voters. Forrest played a prominent role in the spread of the Klan in the South, meeting with racist whites in Atlanta several times between February and March 1868. Forrest probably organized a statewide Klan network in Georgia during these visits. On March 31 the Klan struck, killing prominent Republican organizer

George Ashburn in

Columbus

Columbus is a Latinized version of the Italian surname "''Colombo''". It most commonly refers to:

* Christopher Columbus (1451-1506), the Italian explorer

* Columbus, Ohio, capital of the U.S. state of Ohio

Columbus may also refer to:

Places ...

.

The Republicans had nominated one of Forrest's battle adversaries, Union war hero

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, for the Presidency at their convention held in October. Klansmen took their orders from their former Confederate officers. In Louisiana, 1,000 blacks were killed to suppress Republican voting. In Georgia, blacks and Republicans also faced a lot of violence. The Klan's violence was primarily designed to intimidate voters, targeting black and white supporters of the Republican Party. The Klan's violent tactics backfired, as Grant, whose slogan was "Let us have peace", won the election and Republicans gained a majority in Congress. Grant defeated

Horatio Seymour

Horatio Seymour (May 31, 1810February 12, 1886) was an American politician. He served as Governor of New York from 1853 to 1854 and from 1863 to 1864. He was the Democratic Party nominee for president in the 1868 United States presidential elec ...

, the Democratic presidential candidate, by a comfortable electoral margin, 214 to 80. The popular vote was much closer: Grant received 3,013,365 (52.7%) votes, while Seymour received 2,708,744 (47.3%) votes. Grant lost Georgia and Louisiana, where the violence and intimidation against blacks was most prominent.

Klan prosecution and Congressional testimony (1871)

Many in the north, including President Grant, backed the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, that gave voting rights to Americans regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude". Congress and Grant passed the

Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

from 1870 to 1871, to protect "registration, voting, officeholding, or jury service" of African Americans. Under these laws enforced by Grant and the newly formed

Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a v ...

, there were over 5,000 indictments and 1,000 convictions of Klan members across the South.

Forrest testified before the Congressional investigation of Klan activities on June 27, 1871. He denied membership, but his individual role in the KKK was beyond the scope of the investigating committee, which wrote: "Our design is not to connect General Forrest with this order (the reader may form his own conclusion upon this question)".

The committee also noted, "The natural tendency of all such organizations is to violence and crime; hence it was that General Forrest and other men of influence in the state, by the exercise of their moral power, induced them to disband". George Cantor, a biographer of Confederate generals, wrote, "Forrest ducked and weaved, denying all knowledge, but admitted he knew some of the people involved. He sidestepped some questions and pleaded failure of memory on others. Afterwards, he admitted to 'gentlemanly lies'. He wanted nothing more to do with the Klan, but felt honor bound to protect former associates."

Racial Reconciliation (1870s)

After the

lynch mob murder of four black people who had been arrested for defending themselves in a brawl at a barbecue, Forrest wrote to Tennessee Governor

John C. Brown

John Calvin Brown (January 6, 1827August 17, 1889) was a Confederate Army officer and an American politician and businessman. Although he originally opposed secession, Brown fought for the Confederacy during the American Civil War, eventually ...

in August 1874 and "volunteered to help 'exterminate' those men responsible for the continued violence against the blacks", offering "to exterminate the white marauders who disgrace their race by this cowardly murder of Negroes".

On July 5, 1875, Forrest gave a speech before the Independent Order of Pole-Bearers Association, a post-war organization of black Southerners advocating to improve the economic condition of black people and to gain equal rights for all citizens. At this, his last public appearance, he made what ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' described as a "friendly speech"

during which, when offered a bouquet of flowers by a young black woman, he accepted them,

thanked her and kissed her on the cheek. Forrest spoke in encouragement of black advancement and of endeavoring to be a proponent for espousing peace and harmony between black and white Americans.