Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his

regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ac ...

Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who rose to prominence during the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

and led

successful campaigns during the

Revolutionary Wars. He was the ''de facto'' leader of the

French Republic

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

as First Consul from 1799 to 1804, then

Emperor of the French

Emperor of the French ( French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First and the Second French Empires.

Details

A title and office used by the House of Bonaparte starting when Napoleon was procl ...

from 1804 until 1814 and again in

1815

Events

January

* January 2 – Lord Byron marries Anna Isabella Milbanke in Seaham, county of Durham, England.

* January 3 – Austria, Britain, and Bourbon-restored France form a secret defensive alliance treaty against Prussi ...

. Napoleon's political and cultural legacy endures to this day, as a highly celebrated and controversial leader. He initiated many liberal reforms that have persisted in society, and is considered one of the greatest military commanders in history. His wars and campaigns are studied by militaries all over the world. Between three and six million civilians and soldiers

perished in what became known as the

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

.

Napoleon was born on the island of

Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

, not long after its

annexation by France, to a native family descending from minor

Italian nobility

The nobility of Italy (Italian: ''Nobiltà italiana'') comprised individuals and their families of the Italian Peninsula, and the islands linked with it, recognized by the sovereigns of the Italian city-states since the Middle Ages, and by the k ...

.

He supported the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

in 1789 while serving in the French army, and tried to spread its ideals to his native Corsica. He rose rapidly in the Army after he saved the governing

French Directory

The Directory (also called Directorate, ) was the governing five-member committee in the French First Republic from 2 November 1795 until 9 November 1799, when it was overthrown by Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte in the Coup of 18 Brumaire and r ...

by

firing on royalist insurgents. In 1796, he began

a military campaign against the

Austrians

, pop = 8–8.5 million

, regions = 7,427,759

, region1 =

, pop1 = 684,184

, ref1 =

, region2 =

, pop2 = 345,620

, ref2 =

, region3 =

, pop3 = 197,990

, ref3 ...

and their Italian allies, scoring decisive victories and becoming a national hero. Two years later, he led a

military expedition to Egypt that served as a springboard to political power. He engineered a

coup in November 1799 and became ''

First Consul

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Con ...

of the Republic''.

Differences with the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

meant France faced the

War of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition)

* In French historiography, it is known as the Austrian campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Autriche de 1805) or the German campaign of 1805 (french: Campagne d'Allemagne de 1805) was a European conflict spanni ...

by 1805. Napoleon shattered this coalition with victories in the

Ulm campaign, and at the

Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz in ...

, which led to the dissolution of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

. In 1806, the

Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition fought against Napoleon's French Empire and were defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. The main coalition partners were Prussia and Russia with Saxony, Sweden, and Great Britain also contributing. Excluding Prussia, ...

took up arms against him. Napoleon defeated

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

at the

battles of Jena and Auerstedt, marched the

Grande Armée

''La Grande Armée'' (; ) was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empi ...

into

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

, and defeated

the Russians

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

in June 1807 at

Friedland, forcing the defeated nations of the Fourth Coalition to accept the

Treaties of Tilsit

The Treaties of Tilsit were two agreements signed by French Emperor Napoleon in the town of Tilsit in July 1807 in the aftermath of his victory at Friedland. The first was signed on 7 July, between Napoleon and Russian Emperor Alexander, when t ...

. Two years later, the Austrians challenged the French again during the

War of the Fifth Coalition

The War of the Fifth Coalition was a European conflict in 1809 that was part of the Napoleonic Wars and the Coalition Wars. The main conflict took place in central Europe between the Austrian Empire of Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, Francis ...

, but Napoleon solidified his grip over

Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

after triumphing at the

Battle of Wagram

The Battle of Wagram (; 5–6 July 1809) was a military engagement of the Napoleonic Wars that ended in a costly but decisive victory for Emperor Napoleon's French and allied army against the Austrian army under the command of Archduke Charles ...

.

Hoping to extend the

Continental System, his embargo against Britain, Napoleon invaded the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

and declared his brother

Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

the

King of Spain

, coatofarms = File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Spanish_Monarch.svg

, coatofarms_article = Coat of arms of the King of Spain

, image = Felipe_VI_in_2020_(cropped).jpg

, incumbent = Felipe VI

, incumbentsince = 19 Ju ...

in 1808.

The Spanish and

the Portuguese revolted in the

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was the military conflict fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French Empire during the Napoleonic Wars. In Spain ...

, culminating in defeat for Napoleon's marshals. Napoleon launched an

invasion of Russia in the summer of 1812. The resulting campaign witnessed the catastrophic retreat of Napoleon's

Grande Armée

''La Grande Armée'' (; ) was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empi ...

. In 1813, Prussia and Austria joined Russian forces in a

Sixth Coalition

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor sixth ...

against France, resulting in a large coalition army defeating Napoleon at the

Battle of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig (french: Bataille de Leipsick; german: Völkerschlacht bei Leipzig, ); sv, Slaget vid Leipzig), also known as the Battle of the Nations (french: Bataille des Nations; russian: Битва народов, translit=Bitva ...

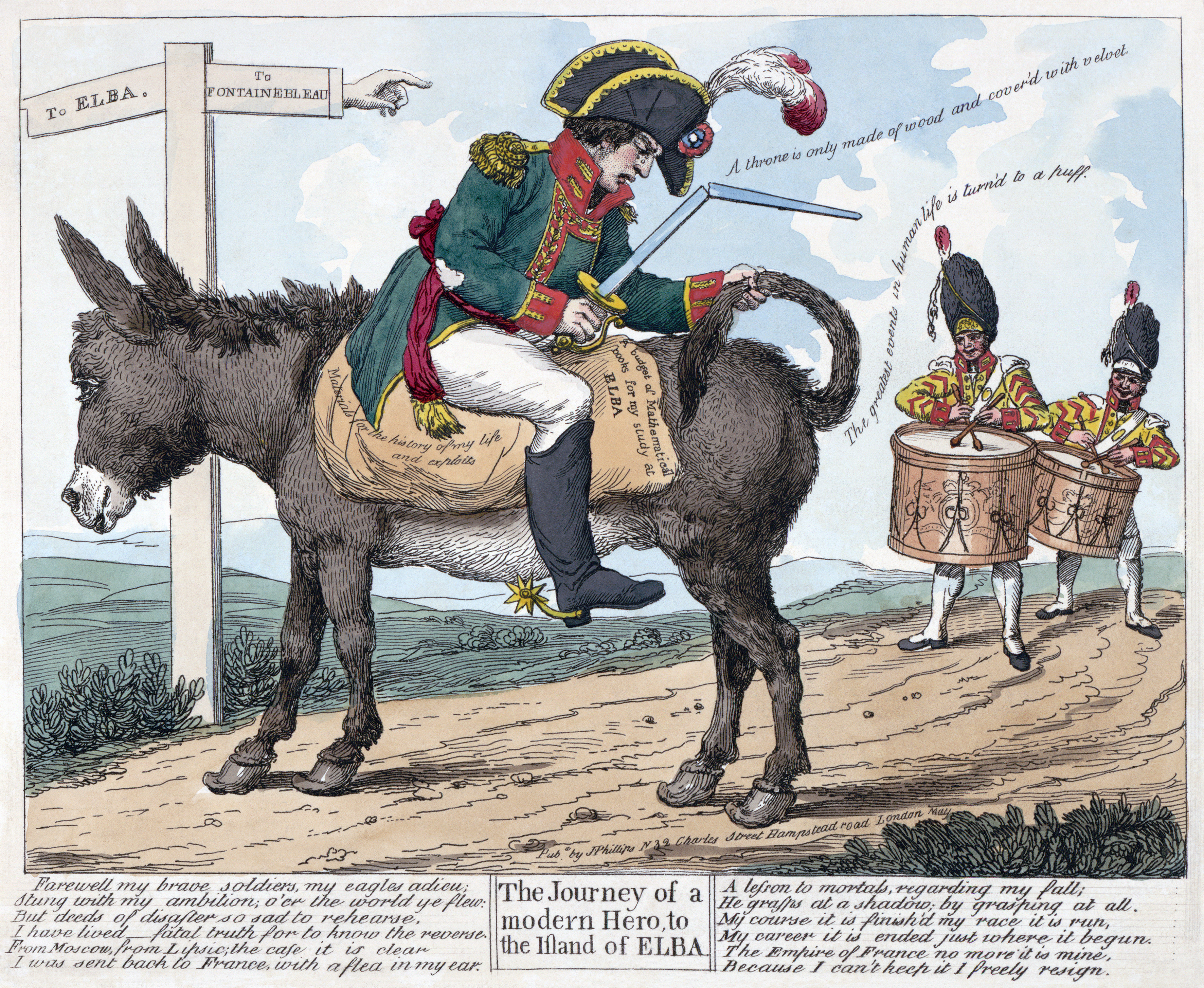

. The coalition

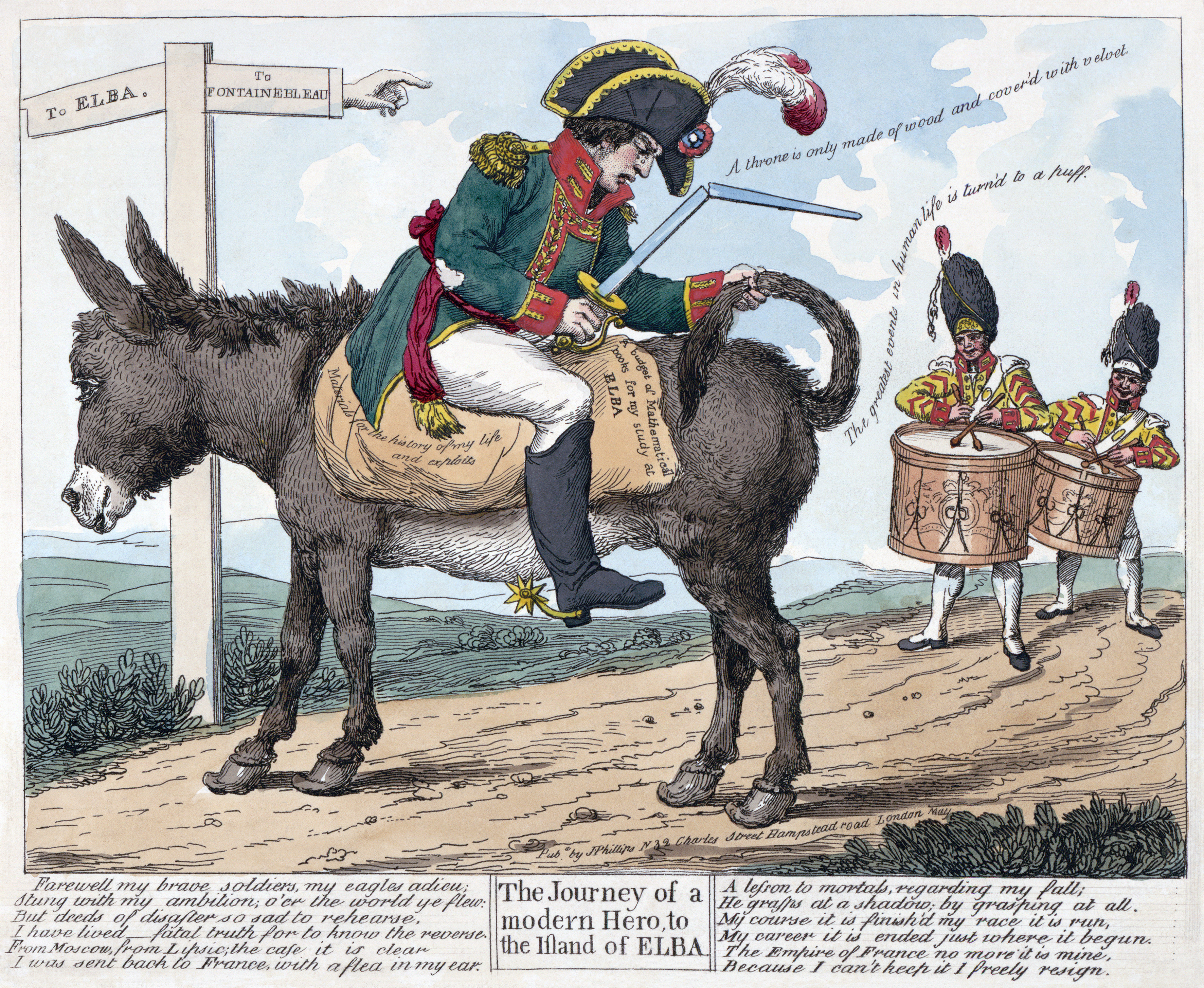

invaded France and captured Paris, forcing Napoleon to abdicate in April 1814. He was exiled to the island of

Elba

Elba ( it, isola d'Elba, ; la, Ilva) is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino on the Italian mainland, and the largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago. It is also part of the Arcipelago Toscano National ...

, between Corsica and Italy. In France, the

Bourbons

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a European dynasty of French origin, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. By the 18th century, members of the Spanish ...

were

restored to power.

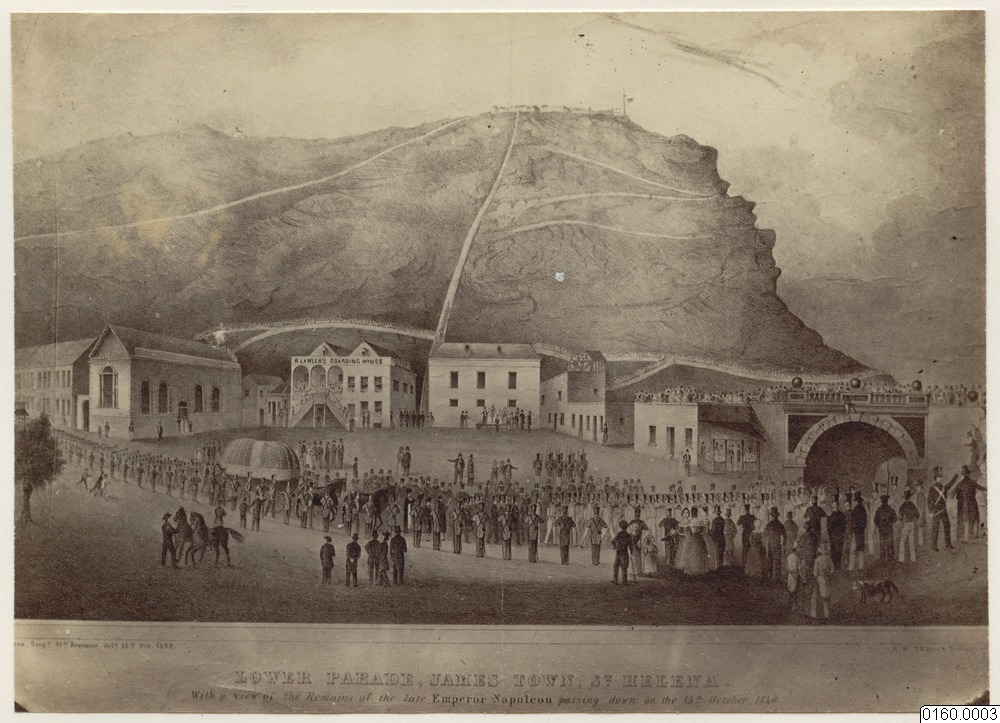

Napoleon escaped in February 1815 and took control of France. The Allies responded by forming a

Seventh Coalition

The Hundred Days (french: les Cent-Jours ), also known as the War of the Seventh Coalition, marked the period between Napoleon's return from eleven months of exile on the island of Elba to Paris on20 March 1815 and the second restoration ...

, which defeated Napoleon at the

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, Belgium, Waterloo (at that time in the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, now in Belgium). A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two of the armie ...

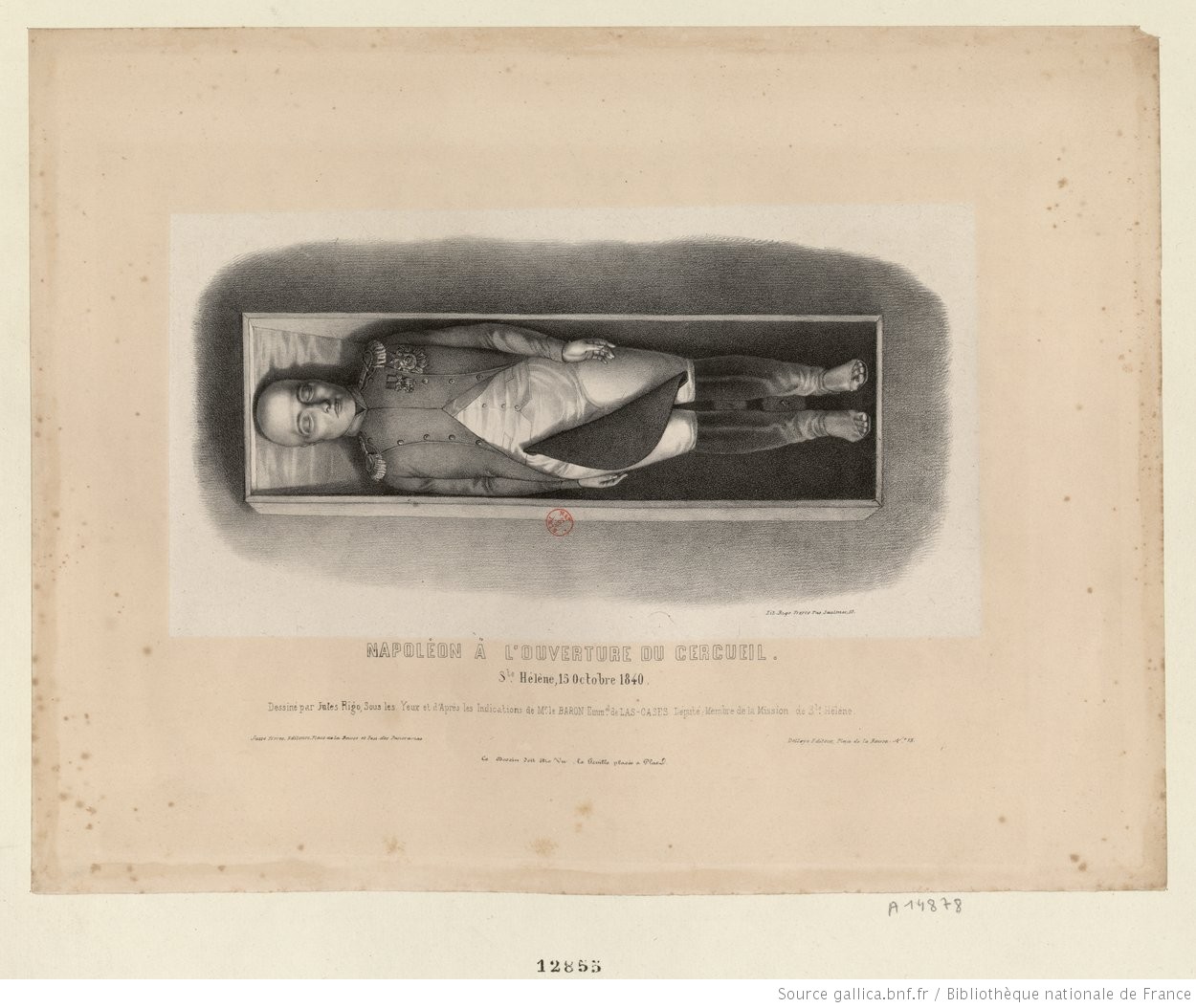

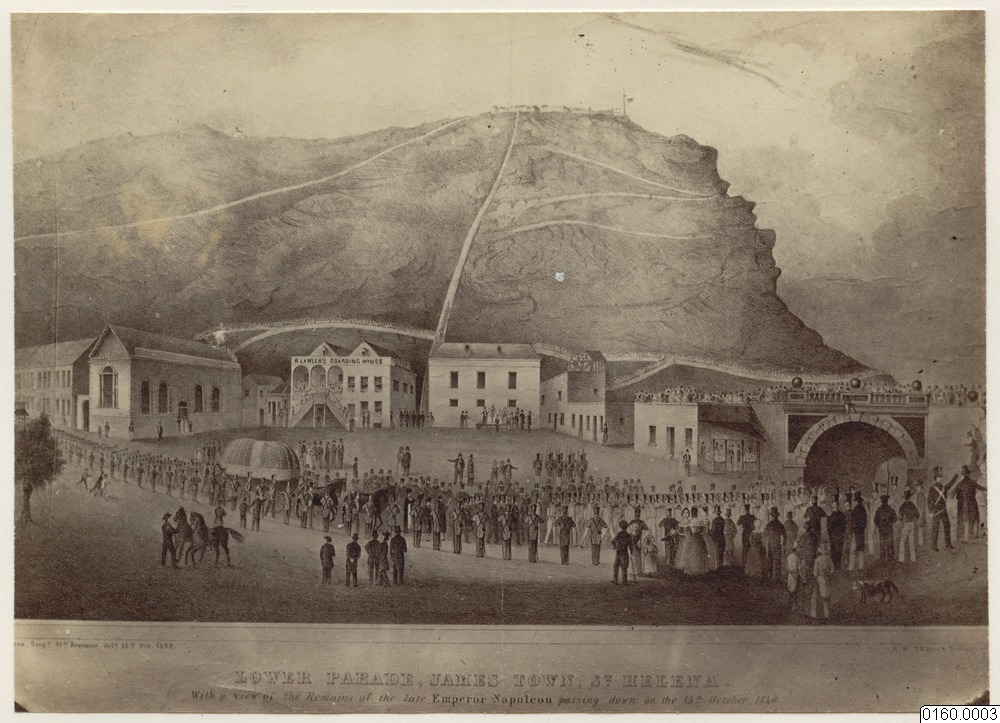

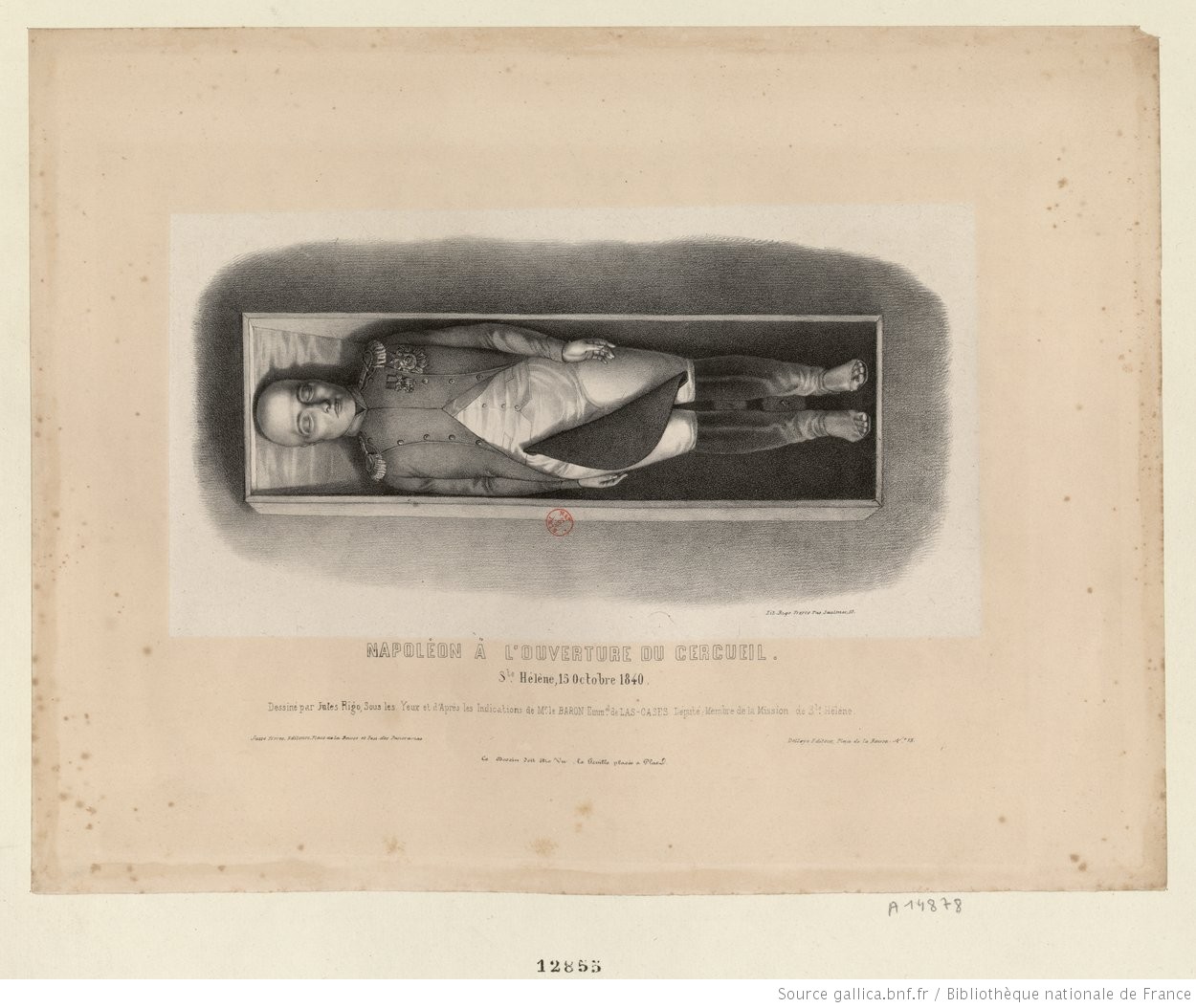

in June 1815. The British exiled him to the remote island of

Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

in the

Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

, where he died in 1821 at the age of 51.

Napoleon had an extensive impact on the modern world, bringing liberal reforms to the lands he conquered, especially the regions of the

Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

,

Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

and parts of modern

Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. He implemented many liberal policies in France and

Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

.

Early life

Napoleon's family was of

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

origin. His paternal ancestors, the Buonapartes, descended from a minor

Tuscan noble family who emigrated to

Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

in the 16th century and his maternal ancestors, the Ramolinos, descended from a minor

Genoese noble family. The Buonapartes were also the relatives, by marriage and by birth, of the Pietrasentas, Costas, Paraviccinis, and Bonellis, all

Corsican families of the interior. His parents

Carlo Maria di Buonaparte and

Maria Letizia Ramolino

Maria-Letizia Buonaparte (née Ramolino; 24 August 1750 (or 1749) – 2 February 1836), known as Letizia Bonaparte, was a Corsican noblewoman, mother of Napoleon I of France. She became known as “” after the proclamation of the Empire. She ...

maintained an ancestral home called "

Casa Buonaparte

''Maison Bonaparte'' ( Corsican and Italian: ''Casa Buonaparte'') is the ancestral home of the Bonaparte family. It is located on the Rue Saint-Charles in Ajaccio on the French island of Corsica. The house was almost continuously owned by me ...

" in

Ajaccio

Ajaccio (, , ; French: ; it, Aiaccio or ; co, Aiacciu , locally: ; la, Adiacium) is a French commune, prefecture of the department of Corse-du-Sud, and head office of the ''Collectivité territoriale de Corse'' (capital city of Corsica). ...

. Napoleon was born there, on 15 August 1769. He was the fourth child and third son of the family. He had an elder brother,

Joseph

Joseph is a common male given name, derived from the Hebrew Yosef (יוֹסֵף). "Joseph" is used, along with "Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the mo ...

, and younger siblings

Lucien

Lucien is a male given name. It is the French form of Luciano or Latin ''Lucianus'', patronymic of Lucius.

Lucien, Saint Lucien, or Saint-Lucien may also refer to:

People

Given name

* Lucien of Beauvais, Christian saint

*Lucien, a band member ...

,

Elisa

The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (, ) is a commonly used analytical biochemistry assay, first described by Eva Engvall and Peter Perlmann in 1971. The assay uses a solid-phase type of enzyme immunoassay (EIA) to detect the presence ...

,

Louis Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis (d ...

,

Pauline,

Caroline

Caroline may refer to:

People

* Caroline (given name), a feminine given name

* J. C. Caroline (born 1933), American college and National Football League player

* Jordan Caroline (born 1996), American (men's) basketball player

Places Antarctica

* ...

, and

Jérôme. Napoleon was baptised as a

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, under the name ''

Napoleone

Napoleone is an Italian male given name. St. Napoleone of Alexandria, alternatively rendered as ''Neopulus'', ''Neopolus'', ''Neopolis'' or ''Neópolo'', whose feast day is August 15, was martyred during the early fourth century during the Diocleti ...

''.

In his youth, his name was also spelled as ''Nabulione'', ''Nabulio'', ''Napolionne'', and ''Napulione''.

Napoleon was born in the same year that the

Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the Lat ...

(former Italian state) ceded the region of Corsica to France.

The state sold

sovereign rights a year before his birth and the

island was conquered by France during the year of his birth. It was formally incorporated as a

province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

in 1770, after

500 years under Genoese rule and

14 years of independence. Napoleon's parents joined the Corsican resistance and fought against the French to maintain independence, even when Maria was pregnant with him. His father Carlo was an attorney who had supported and actively collaborated with patriot

Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; french: link=no, Pascal Paoli; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Genoese and later ...

during the Corsican war of independence against France;

[ after the Corsican defeat at ]Ponte Novu

Ponte, a word meaning ''bridge'' in Italian, Portuguese, and Galician languages, may refer to:

Places

England

*Pontefract, a town in the Metropolitan City of Wakefield

France

* Ponte Leccia, a civil parish (hameau) in the department of Haute-Co ...

in 1769 and Paoli's exile in Britain, Carlo began working for the new French government and went on to be named representative of the island to the court of Louis XVI

Louis XVI (''Louis-Auguste''; ; 23 August 175421 January 1793) was the last King of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution. He was referred to as ''Citizen Louis Capet'' during the four months just before he was ...

in 1777.[Cronin 1994, pp. 20–21]

The dominant influence of Napoleon's childhood was his mother, whose firm discipline restrained a rambunctious child.Joseph Fesch

Joseph Fesch, Prince of France (3 January 1763 – 13 May 1839) was a French priest and diplomat, who was the maternal half-uncle of Napoleon Bonaparte (half-brother of Napoleon's mother Laetitia). In the wake of his nephew, he became Archbishop ...

, would fulfill a role as protector of the Bonaparte family for some years. Napoleon's noble, moderately affluent background afforded him greater opportunities to study than were available to a typical Corsican of the time.

When he turned 9 years old,

When he turned 9 years old,military academy

A military academy or service academy is an educational institution which prepares candidates for service in the officer corps. It normally provides education in a military environment, the exact definition depending on the country concerned. ...

at Brienne-le-Château.Corsican nationalist

Corsican nationalism is a nationalist movement in Corsica that advocates more autonomy for the island, if not outright independence from France.

Political support

The main separatist party, Corsica Libera, achieved 9.85% of votes in the ...

and supported the state's independence from France.Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

(as the official language of Corsica).French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

in school at around age 10. Although he became fluent in French, he spoke with a distinctive Corsican accent and never learned how to spell correctly in French. Consequently, Napoleon was treated unfairly by his schoolmates.novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

.École Militaire

École may refer to:

* an elementary school in the French educational stages normally followed by secondary education establishments (collège and lycée)

* École (river), a tributary of the Seine flowing in région Île-de-France

* École, Savoi ...

'' in Paris. He trained to become an artillery officer and, when his father's death reduced his income, was forced to complete the two-year course in one year.Pierre-Simon Laplace

Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French scholar and polymath whose work was important to the development of engineering, mathematics, statistics, physics, astronomy, and philosophy. He summarized ...

.

Early career

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte was commissioned a

Upon graduating in September 1785, Bonaparte was commissioned a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

in ''La Fère'' artillery regiment.[Roberts, Andrew. ''Napoleon: A Life''. Penguin Group, 2014, Corsica.] He asked for leave to join his mentor Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; french: link=no, Pascal Paoli; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Genoese and later ...

, when Paoli was allowed to return to Corsica by the National Assembly. Paoli had no sympathy for Napoleon, however, as he deemed his father a traitor for having deserted his cause for Corsican independence.[Roberts, Andrew. ''Napoleon: A Life''. Penguin Group, 2014, Revolution.]

He spent the early years of the Revolution in Corsica, fighting in a complex three-way struggle among royalists, revolutionaries, and Corsican nationalists. Napoleon came to embrace the ideals of the Revolution, becoming a supporter of the Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

s and joining the pro-French Corsican Republicans who opposed Paoli's policy and his aspirations of secession. He was given command over a battalion of volunteers and was promoted to captain in the regular army in July 1792, despite exceeding his leave of absence and leading a riot against French troops.

When Corsica declared formal secession from France and requested the protection of the British government, Napoleon and his commitment to the French Revolution came into conflict with Paoli, who had decided to sabotage the Corsican contribution to the ''Expédition de Sardaigne

The French expedition to Sardinia was a short military campaign fought in 1793 in the Mediterranean Sea in the first year of the War of the First Coalition, during the French Revolutionary Wars. The operation was the first offensive by the new ...

'', by preventing a French assault on the Sardinian island of La Maddalena

La Maddalena (Gallurese: ''Madalena'' or ''La Madalena'', sc, Sa Madalena) is a town and ''comune'' located on the islands of the Maddalena archipelago in the province of Sassari, northern Sardinia, Italy.

The main town of the same name is locat ...

. Bonaparte and his family were compelled to flee to Toulon on the French mainland in June 1793 because of the split with Paoli.[Roberts 2001, p. xviii]

Although he was born "Napoleone Buonaparte", it was after this that Napoleon began styling himself "Napoléon Bonaparte". His family did not drop the name Buonaparte until 1796. The first known record of him signing his name as Bonaparte was at the age of 27 (in 1796).

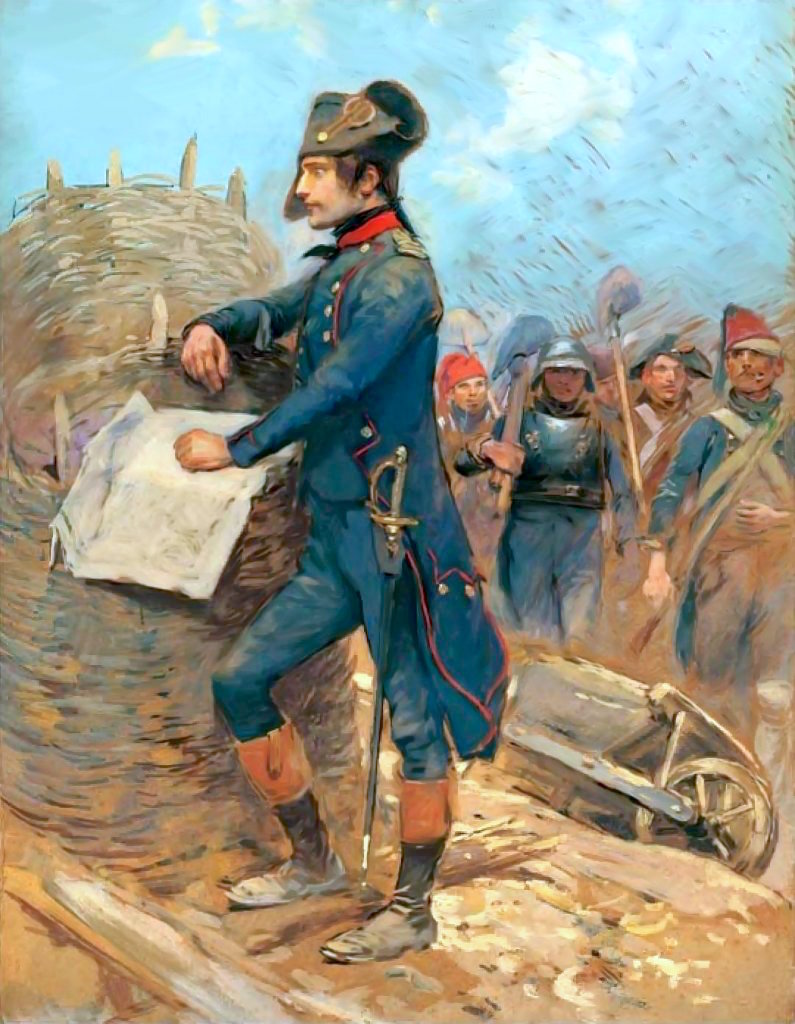

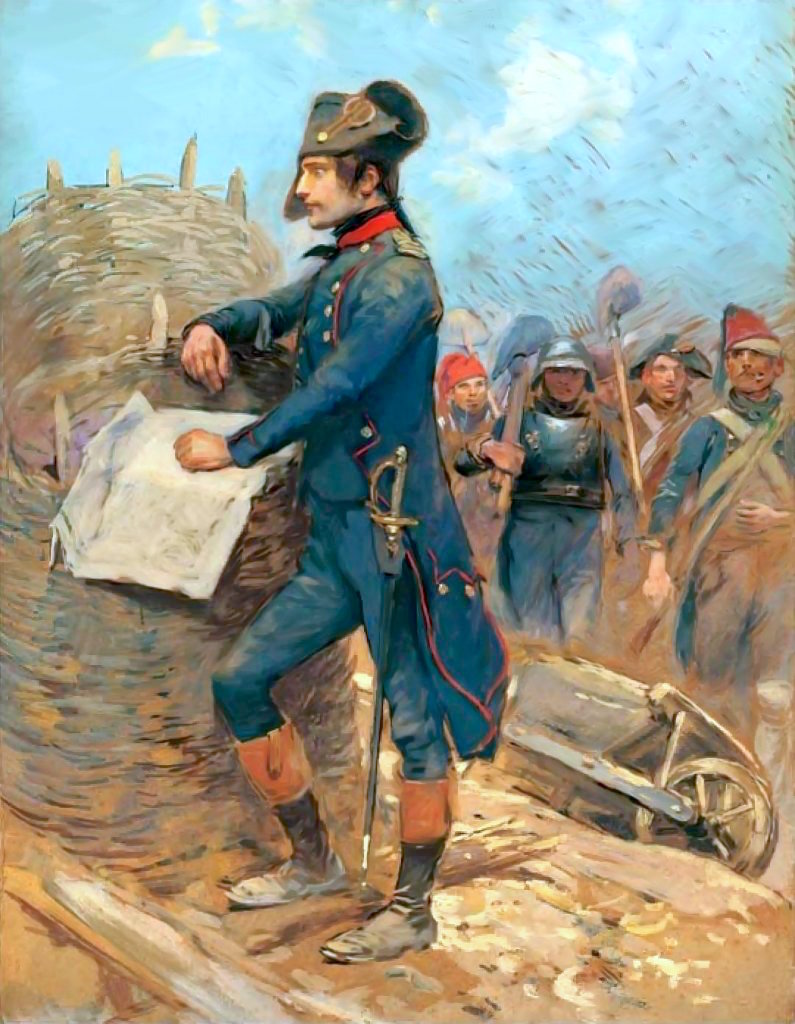

Siege of Toulon

In July 1793, Bonaparte published a pro-republican pamphlet entitled ''

In July 1793, Bonaparte published a pro-republican pamphlet entitled ''Le souper de Beaucaire

''Le souper de Beaucaire'' was a political pamphlet written by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1793. With the French Revolution into its fourth year, civil war had spread across France between various rival political factions. Napoleon was involved in mil ...

'' (Supper at Beaucaire) which gained him the support of Augustin Robespierre

Augustin Bon Joseph de Robespierre (21 January 1763 – 28 July 1794), known as Robespierre the Younger, was a French people, French lawyer, politician and the younger brother of French Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre. His political v ...

, the younger brother of the Revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman who became one of the best-known, influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. As a member of the Esta ...

. With the help of his fellow Corsican Antoine Christophe Saliceti

Antoine Christophe Saliceti (baptised in the name of ''Antonio Cristoforo Saliceti'': ''Antoniu Cristufaru Saliceti'' in Corsican; 26 August 175723 December 1809) was a French politician and diplomat of the Revolution and First Empire.

Early ca ...

, Bonaparte was appointed senior gunner and artillery commander of the republican forces which arrived on 8 September at Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

.

He adopted a plan to capture a hill where republican guns could dominate the city's harbour and force the British to evacuate. The assault on the position led to the capture of the city, and during it Bonaparte was wounded in the thigh on 16 December. Catching the attention of the Committee of Public Safety

The Committee of Public Safety (french: link=no, Comité de salut public) was a committee of the National Convention which formed the provisional government and war cabinet during the Reign of Terror, a violent phase of the French Revolution. S ...

, he was put in charge of the artillery of France's Army of Italy. On 22 December he was on his way to his new post in Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

, promoted from the rank of colonel to brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

at the age of 24. He devised plans for attacking the Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia,The name of the state was originally Latin: , or when the kingdom was still considered to include Corsica. In Italian it is , in French , in Sardinian , and in Piedmontese . also referred to as the Kingdom of Savoy-S ...

as part of France's campaign against the First Coalition.

The French army carried out Bonaparte's plan in the Battle of Saorgio in April 1794, and then advanced to seize Ormea

Ormea is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Cuneo in the Italian region Piedmont, located about south of Turin and about southeast of Cuneo.

Ormea borders the following municipalities: Alto, Armo, Briga Alta, Caprauna, Cosio di Arro ...

in the mountains. From Ormea, they headed west to outflank the Austro-Sardinian positions around Saorge

Saorge (; Royasc: ''Sauèrge''; Brigasc: ''Savurgë''; it, Saorgio, oc, Saorj, lij, Savurgiu) is a Communes of France, commune in the Alpes-Maritimes Departments of France, department in southeastern France. Highway E74 which runs north from ...

. After this campaign, Augustin Robespierre sent Bonaparte on a mission to the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( lij, Repúbrica de Zêna ; it, Repubblica di Genova; la, Res Publica Ianuensis) was a medieval and early modern maritime republic from the 11th century to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italian coast. During the Lat ...

to determine that country's intentions towards France.

13 Vendémiaire

Some contemporaries alleged that Bonaparte was put under house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if all ...

at Nice

Nice ( , ; Niçard: , classical norm, or , nonstandard, ; it, Nizza ; lij, Nissa; grc, Νίκαια; la, Nicaea) is the prefecture of the Alpes-Maritimes department in France. The Nice agglomeration extends far beyond the administrative c ...

for his association with the Robespierres following their fall in the Thermidorian Reaction

The Thermidorian Reaction (french: Réaction thermidorienne or ''Convention thermidorienne'', "Thermidorian Convention") is the common term, in the historiography of the French Revolution, for the period between the ousting of Maximilien Robespie ...

in July 1794. Napoleon's secretary Bourrienne disputed the allegation in his memoirs. According to Bourrienne, jealousy was responsible, between the Army of the Alps and the Army of Italy, with whom Napoleon was seconded at the time. Bonaparte dispatched an impassioned defence in a letter to the commissar Saliceti, and he was acquitted of any wrongdoing. He was released within two weeks (on 20 August) and due to his technical skills, was asked to draw up plans to attack Italian positions in the context of France's war with Austria. He also took part in an expedition to take back Corsica from the British, but the French were repulsed by the British Royal Navy.

By 1795, Bonaparte had become engaged to Désirée Clary, daughter of François Clary

François Clary (24 February 1725 – 20 January 1794) was a wealthy Irish-French merchant and is an ancestor of many European monarchs by two of his daughters. He was the father of Julie Clary, Queen of Naples and of Spain and the Indies by marr ...

. Désirée's sister Julie Clary

Marie Julie Clary (26 December 1771 – 7 April 1845), was Queen of Naples, then of Spain and the Indies, as the wife of Joseph Bonaparte, who was King of Naples from January 1806 to June 1808, and later King of Spain and the Spanish West Indi ...

had married Bonaparte's elder brother Joseph. In April 1795, he was assigned to the Army of the West, which was engaged in the War in the Vendée

The war in the Vendée (french: link=no, Guerre de Vendée) was a counter-revolution from 1793 to 1796 in the Vendée region of France during the French Revolution. The Vendée is a coastal region, located immediately south of the river Loir ...

—a civil war and royalist counter-revolution in Vendée, a region in west-central France on the Atlantic Ocean. As an infantry command, it was a demotion from artillery general—for which the army already had a full quota—and he pleaded poor health to avoid the posting.

He was moved to the Bureau of

He was moved to the Bureau of Topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

of the Committee of Public Safety. He sought unsuccessfully to be transferred to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

in order to offer his services to the Sultan. During this period, he wrote the romantic novella ''Clisson et Eugénie

''Clisson et Eugénie'', also known in English as ''Clisson and Eugénie'', is a romantic novella, written by Napoleon Bonaparte. Napoleon wrote ''Clisson et Eugénie'' in 1795, and it is widely acknowledged as being a fictionalised account of th ...

'', about a soldier and his lover, in a clear parallel to Bonaparte's own relationship with Désirée. On 15 September, Bonaparte was removed from the list of generals in regular service for his refusal to serve in the Vendée campaign. He faced a difficult financial situation and reduced career prospects.

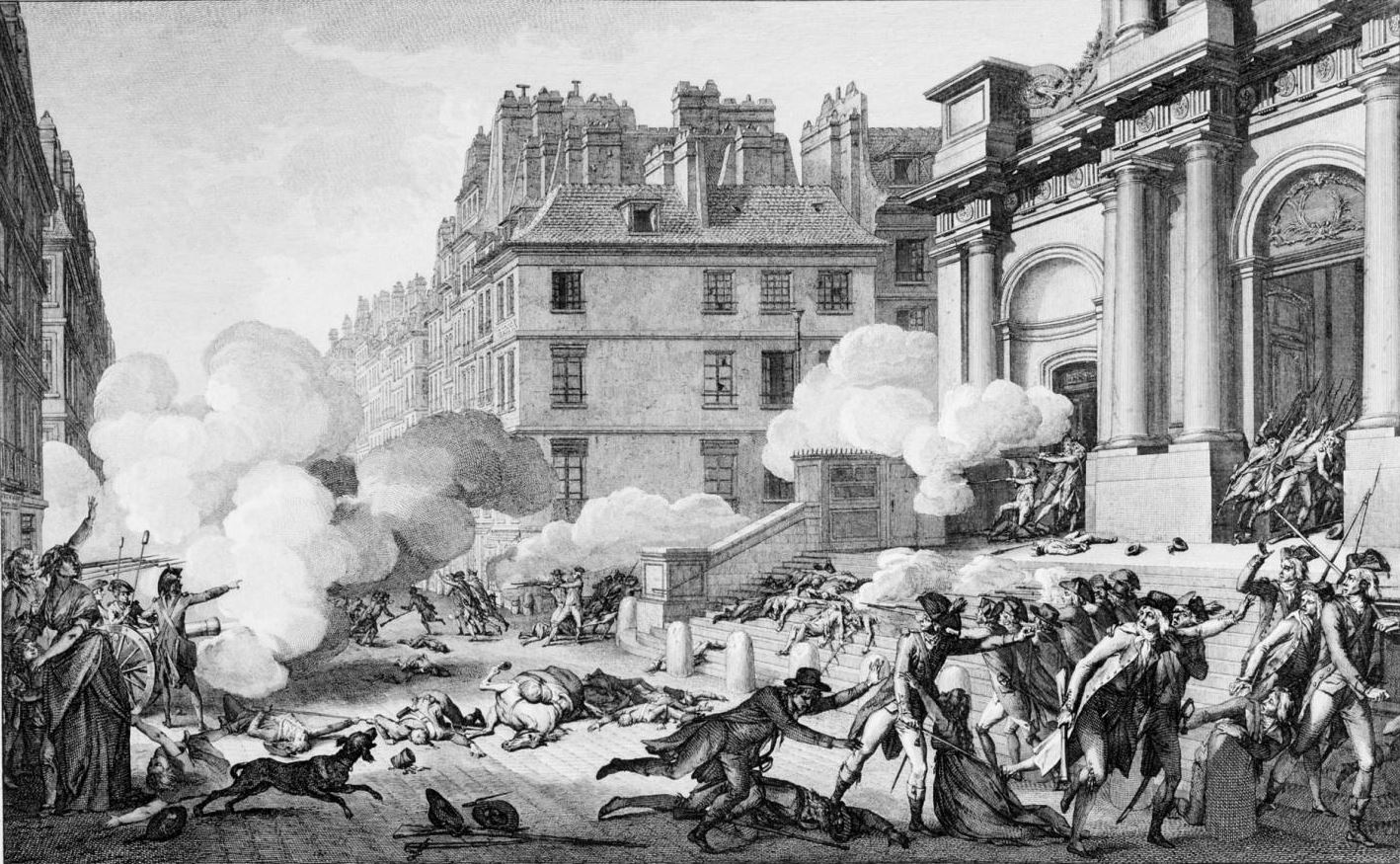

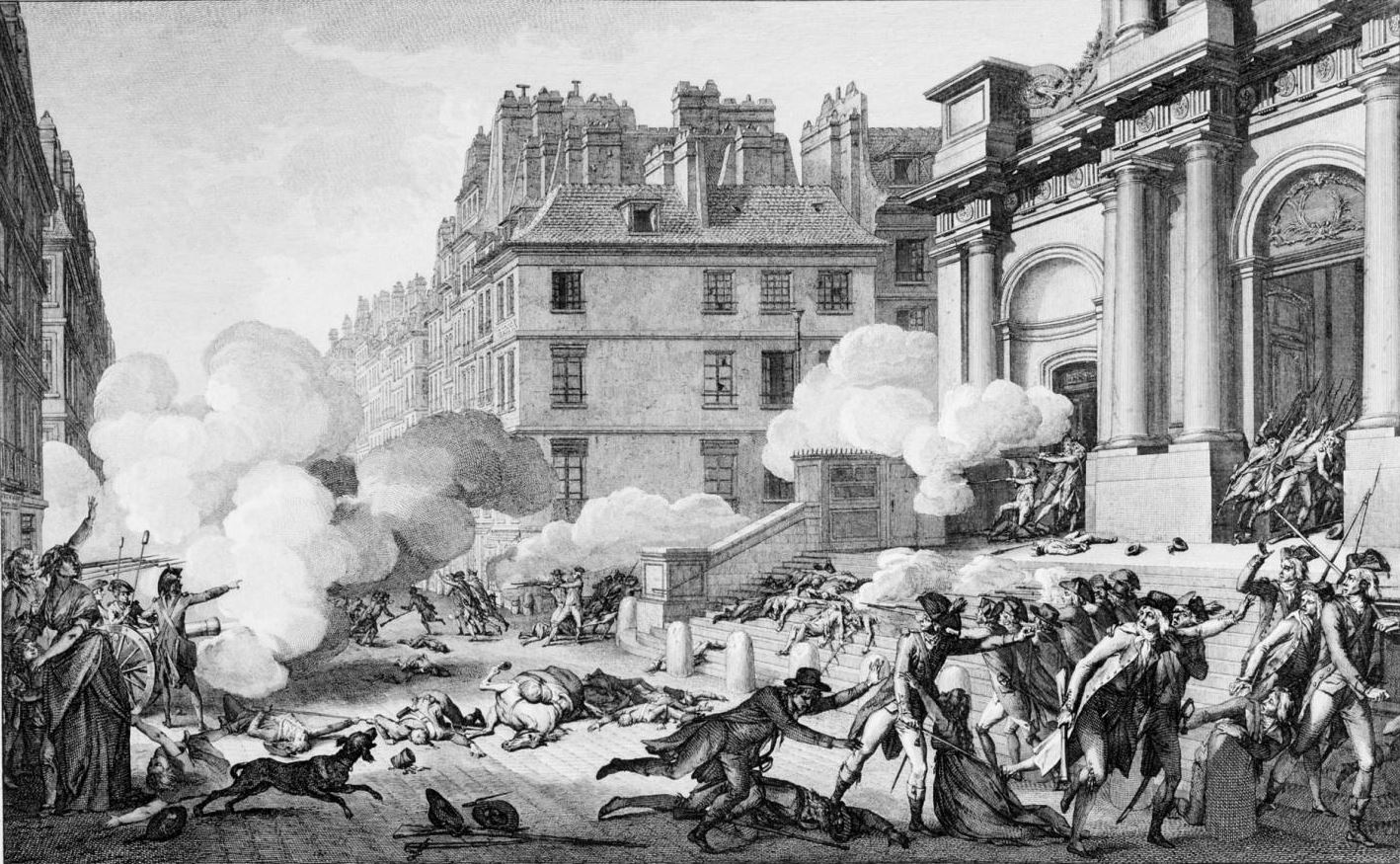

On 3 October, royalists in Paris declared a rebellion against the National Convention

The National Convention (french: link=no, Convention nationale) was the parliament of the Kingdom of France for one day and the French First Republic for the rest of its existence during the French Revolution, following the two-year National ...

.Paul Barras

Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras (, 30 June 1755 – 29 January 1829), commonly known as Paul Barras, was a French politician of the French Revolution, and the main executive leader of the Directory regime of 1795–1799.

Early ...

, a leader of the Thermidorian Reaction, knew of Bonaparte's military exploits at Toulon and gave him command of the improvised forces in defence of the convention in the Tuileries Palace

The Tuileries Palace (french: Palais des Tuileries, ) was a royal and imperial palace in Paris which stood on the right bank of the River Seine, directly in front of the Louvre. It was the usual Parisian residence of most French monarchs, from ...

. Napoleon had seen the massacre of the King's Swiss Guard there three years earlier and realized that artillery would be the key to its defence.[Roberts 2001, p. xvi]

He ordered a young cavalry officer named Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also , ; it, Gioacchino Murati; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French military commander and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the ...

to seize large cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s and used them to repel the attackers on 5 October 1795—''13 Vendémiaire An IV'' in the French Republican Calendar. 1,400 royalists died and the rest fled.grapeshot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

", according to 19th-century historian Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher. A leading writer of the Victorian era, he exerted a profound influence on 19th-century art, literature and philosophy.

Born in Ecclefechan, Dum ...

in '' The French Revolution: A History''.

The defeat of the royalist insurrection extinguished the threat to the Convention and earned Bonaparte sudden fame, wealth, and the patronage of the new government, the Directory

Directory may refer to:

* Directory (computing), or folder, a file system structure in which to store computer files

* Directory (OpenVMS command)

* Directory service, a software application for organizing information about a computer network's u ...

. Murat married one of Napoleon's sisters, becoming his brother-in-law; he also served under Napoleon as one of his generals. Bonaparte was promoted to Commander of the Interior and given command of the Army of Italy.Joséphine de Beauharnais

Josephine may refer to:

People

* Josephine (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Josephine (singer), a Greek pop singer

Places

*Josephine, Texas, United States

*Mount Josephine (disambiguation)

* Josephine Count ...

, the former mistress of Barras. The couple married on 9 March 1796 in a civil ceremony.

First Italian campaign

Two days after the marriage, Bonaparte left Paris to take command of the Army of Italy. He immediately went on the offensive, hoping to defeat the forces of

Two days after the marriage, Bonaparte left Paris to take command of the Army of Italy. He immediately went on the offensive, hoping to defeat the forces of Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

before their Austrian allies could intervene. In a series of rapid victories during the Montenotte Campaign, he knocked Piedmont out of the war in two weeks. The French then focused on the Austrians for the remainder of the war, the highlight of which became the protracted struggle for Mantua. The Austrians

, pop = 8–8.5 million

, regions = 7,427,759

, region1 =

, pop1 = 684,184

, ref1 =

, region2 =

, pop2 = 345,620

, ref2 =

, region3 =

, pop3 = 197,990

, ref3 ...

launched a series of offensives against the French to break the siege, but Napoleon defeated every relief effort, scoring victories at the battles of Castiglione, Bassano, Arcole, and Rivoli. The decisive French triumph at Rivoli in January 1797 led to the collapse of the Austrian position in Italy. At Rivoli, the Austrians lost up to 14,000 men while the French lost about 5,000.

The next phase of the campaign featured the French invasion of the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (), alternatively spelled Hapsburg in Englishgerman: Haus Habsburg, ; es, Casa de Habsburgo; hu, Habsburg család, it, Casa di Asburgo, nl, Huis van Habsburg, pl, dom Habsburgów, pt, Casa de Habsburgo, la, Domus Hab ...

heartlands. French forces in Southern Germany had been defeated by the Archduke Charles in 1796, but the Archduke withdrew his forces to protect Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

after learning about Napoleon's assault. In the first encounter between the two commanders, Napoleon pushed back his opponent and advanced deep into Austrian territory after winning at the Battle of Tarvis in March 1797. The Austrians were alarmed by the French thrust that reached all the way to Leoben

Leoben () is a Styrian city in central Austria, located on the Mur river. With a population of about 25,000 it is a local industrial centre and hosts the University of Leoben, which specialises in mining. The Peace of Leoben, an armistice betwee ...

, about 100 km from Vienna, and decided to sue for peace.

The Treaty of Leoben

The Peace of Leoben was a general armistice and preliminary peace agreement between the Holy Roman Empire and the First French Republic that ended the War of the First Coalition. It was signed at Eggenwaldsches Gartenhaus, near Leoben, on 18 Apr ...

, followed by the more comprehensive Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The treat ...

, gave France control of most of northern Italy and the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, and a secret clause promised the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

to Austria. Bonaparte marched on Venice and forced its surrender, ending 1,100 years of Venetian independence. He authorized the French to loot treasures such as the Horses of Saint Mark

The Horses of Saint Mark ( it, Cavalli di San Marco), also known as the Triumphal Quadriga or Horses of the Hippodrome of Constantinople, is a set of bronze statues of four horses, originally part of a monument depicting a quadriga (a four-horse ...

.

On the journey, Bonaparte conversed much about the warriors of antiquity, especially Alexander, Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caes ...

, Scipio and Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

. He studied their strategy and combined it with his own. In a question from Bourrienne, asking whether he gave his preference to Alexander or Caesar, Napoleon said that he places Alexander the Great in the first rank, the main reason being his campaign in Asia.

His application of conventional military ideas to real-world situations enabled his military triumphs, such as creative use of artillery as a mobile force to support his infantry. He stated later in life: "I have fought sixty battles and I have learned nothing which I did not know at the beginning. Look at Caesar; he fought the first like the last".

Bonaparte could win battles by concealment of troop deployments and concentration of his forces on the "hinge" of an enemy's weakened front. If he could not use his favourite envelopment strategy, he would take up the central position and attack two co-operating forces at their hinge, swing round to fight one until it fled, then turn to face the other. In this Italian campaign, Bonaparte's army captured 150,000 prisoners, 540 cannons, and 170 standards Standard may refer to:

Symbols

* Colours, standards and guidons, kinds of military signs

* Standard (emblem), a type of a large symbol or emblem used for identification

Norms, conventions or requirements

* Standard (metrology), an object th ...

. The French army fought 67 actions and won 18 pitched battle

A pitched battle or set-piece battle is a battle in which opposing forces each anticipate the setting of the battle, and each chooses to commit to it. Either side may have the option to disengage before the battle starts or shortly thereafter. A ...

s through superior artillery technology and Bonaparte's tactics.

During the campaign, Bonaparte became increasingly influential in French politics. He founded two newspapers: one for the troops in his army and another for circulation in France. The royalists attacked Bonaparte for looting Italy and warned that he might become a dictator. Napoleon's forces extracted an estimated $45 million in funds from Italy during their campaign there, another $12 million in precious metals and jewels. His forces confiscated more than 300 priceless paintings and sculptures.

Bonaparte sent General Pierre Augereau

Charles Pierre François Augereau, 1st Duke of Castiglione (21 October 1757 – 12 June 1816) was a French military commander and a Marshal of the Empire who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars. After serving in ...

to Paris to lead a ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' and purge the royalists on 4 September—the Coup of 18 Fructidor

The Coup of 18 Fructidor, Year V (4 September 1797 in the French Republican Calendar), was a seizure of power in France by members of the Directory, the government of the French First Republic, with support from the French military. The coup wa ...

. This left Barras and his Republican allies in control again but dependent upon Bonaparte, who proceeded to peace negotiations with Austria. These negotiations resulted in the Treaty of Campo Formio

The Treaty of Campo Formio (today Campoformido) was signed on 17 October 1797 (26 Vendémiaire VI) by Napoleon Bonaparte and Count Philipp von Cobenzl as representatives of the French Republic and the Austrian monarchy, respectively. The treat ...

. Bonaparte returned to Paris in December 1797 as a hero. He met Talleyrand, France's new Foreign Minister—who served in the same capacity for Emperor Napoleon—and they began to prepare for an invasion of Britain.

Egyptian expedition

After two months of planning, Bonaparte decided that France's naval strength was not yet sufficient to confront the British Royal Navy. He decided on a military expedition to seize

After two months of planning, Bonaparte decided that France's naval strength was not yet sufficient to confront the British Royal Navy. He decided on a military expedition to seize Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and thereby undermine Britain's access to its trade interests in India.Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (born Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu, 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799), also known as the Tiger of Mysore, was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery.Dalrymple, p. 243 He int ...

, the Sultan of Mysore

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

who was an enemy of the British.[Amini 2000, p. 12] The Directory agreed in order to secure a trade route to the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

.

In May 1798, Bonaparte was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific me ...

. His Egyptian expedition included a group of 167 scientists, with mathematicians, naturalists, chemists, and geodesists

Geodesy ( ) is the Earth science of accurately measuring and understanding Earth's figure (geometric shape and size), orientation in space, and gravity. The field also incorporates studies of how these properties change over time and equivale ...

among them. Their discoveries included the Rosetta Stone

The Rosetta Stone is a stele composed of granodiorite inscribed with three versions of a Rosetta Stone decree, decree issued in Memphis, Egypt, in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes. The top and middle te ...

, and their work was published in the '' Description de l'Égypte'' in 1809.

En route to Egypt, Bonaparte reached

En route to Egypt, Bonaparte reached Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

on 9 June 1798, then controlled by the Knights Hospitaller

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic Church, Catholic Military ord ...

. Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim

Ferdinand von Hompesch zu Bolheim, O.S.I. (9 November 1744 – 12 May 1805) was the 71st Grand Master of the Knights Hospitaller, formally the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, by then better known as the Knights of Malta. He was the first Ge ...

surrendered after token resistance, and Bonaparte captured an important naval base with the loss of only three men.

Bonaparte and his expedition eluded pursuit by the Royal Navy and landed at Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

on 1 July.Battle of Shubra Khit

The Battle of Shubra Khit, also known as the Battle of Chobrakit, was the first major engagement of Napoleon's campaign in Egypt that took place on 13 July, 1798. On their march to Cairo, the French army encountered an Ottoman army consisting of ...

against the Mamluk

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning " slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') ...

s, Egypt's ruling military caste. This helped the French practise their defensive tactic for the Battle of the Pyramids, fought on 21 July, about from the pyramids

A pyramid (from el, πυραμίς ') is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge to a single step at the top, making the shape roughly a pyramid in the geometric sense. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilate ...

. General Bonaparte's forces of 25,000 roughly equalled those of the Mamluks' Egyptian cavalry. Twenty-nine French and approximately 2,000 Egyptians were killed. The victory boosted the morale of the French army.

On 1 August 1798, the British fleet under Sir Horatio Nelson

Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, 1st Duke of Bronte (29 September 1758 – 21 October 1805) was a British flag officer in the Royal Navy. His inspirational leadership, grasp of strategy, and unconventional tactics brought abo ...

captured or destroyed all but two vessels of the French fleet in the Battle of the Nile

The Battle of the Nile (also known as the Battle of Aboukir Bay; french: Bataille d'Aboukir) was a major naval battle fought between the British Royal Navy and the Navy of the French Republic at Aboukir Bay on the Mediterranean coast off the ...

, defeating Bonaparte's goal to strengthen the French position in the Mediterranean. His army had succeeded in a temporary increase of French power in Egypt, though it faced repeated uprisings. In early 1799, he moved an army into the Ottoman province

The administrative divisions of the Ottoman Empire were administrative divisions of the state organisation of the Ottoman Empire. Outside this system were various types of vassal and tributary states.

The Ottoman Empire was first subdivided ...

of Damascus (Syria and Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

). Bonaparte led these 13,000 French soldiers in the conquest of the coastal towns of Arish

ʻArish or el-ʻArīsh ( ar, العريش ' , ''Hrinokorura'') is the capital and largest city (with 164,830 inhabitants ) of the North Sinai Governorate of Egypt, as well as the largest city on the entire Sinai Peninsula, lying on the Mediter ...

, Gaza, Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

, and Haifa

Haifa ( he, חֵיפָה ' ; ar, حَيْفَا ') is the third-largest city in Israel—after Jerusalem and Tel Aviv—with a population of in . The city of Haifa forms part of the Haifa metropolitan area, the third-most populous metropol ...

. The attack on Jaffa was particularly brutal. Bonaparte discovered that many of the defenders were former prisoners of war, ostensibly on parole

Parole (also known as provisional release or supervised release) is a form of early release of a prison inmate where the prisoner agrees to abide by certain behavioral conditions, including checking-in with their designated parole officers, or ...

, so he ordered the garrison and some 1,500–2,000 prisoners to be executed by bayonet or drowning. Men, women, and children were robbed and murdered for three days.

Bonaparte began with an army of 13,000 men. 1,500 were reported missing, 1,200 died in combat, and thousands perished from disease—mostly bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is one of three types of plague caused by the plague bacterium (''Yersinia pestis''). One to seven days after exposure to the bacteria, flu-like symptoms develop. These symptoms include fever, headaches, and vomiting, as well a ...

. He failed to reduce the fortress of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

, so he marched his army back to Egypt in May. To speed up the retreat, Bonaparte ordered plague-stricken men to be poisoned with opium. The number who died remains disputed, ranging from a low of 30 to a high of 580. He also brought out 1,000 wounded men. Back in Egypt on 25 July, Bonaparte defeated an Ottoman amphibious invasion at Abukir.

Ruler of France

While in Egypt, Bonaparte stayed informed of European affairs. He learned that France had suffered a series of defeats in the

While in Egypt, Bonaparte stayed informed of European affairs. He learned that France had suffered a series of defeats in the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on periodisation) was the second war on revolutionary France by most of the European monarchies, led by Britain, Austria and Russia, and including the Ottoman Empire, Portugal, N ...

.Jean-Baptiste Kléber

Jean-Baptiste Kléber () (9 March 1753 – 14 June 1800) was a French general during the French Revolutionary Wars. After serving for one year in the French Royal Army, he entered Habsburg service seven years later. However, his plebeian ances ...

.

Unknown to Bonaparte, the Directory had sent him orders to return to ward off possible invasions of French soil, but poor lines of communication prevented the delivery of these messages.[Connelly 2006, p. 57] By the time that he reached Paris in October, France's situation had been improved by a series of victories. The Republic, however, was bankrupt and the ineffective Directory was unpopular with the French population. The Directory discussed Bonaparte's "desertion" but was too weak to punish him.Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (3 May 174820 June 1836), usually known as the Abbé Sieyès (), was a French Roman Catholic '' abbé'', clergyman, and political writer who was the chief political theorist of the French Revolution (1789–1799); he also ...

, his brother Lucien, speaker of the Council of Five Hundred Roger Ducos

Pierre Roger Ducos (25 July 174716 March 1816), better known as Roger Ducos, was a French political figure during the Revolution and First Empire, a member of the National Convention, and of the Directory.

In the Revolution

Born in Montfort-en- ...

, director Joseph Fouché

Joseph Fouché, 1st Duc d'Otrante, 1st Comte Fouché (, 21 May 1759 – 25 December 1820) was a French statesman, revolutionary, and Minister of Police under First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte, who later became a subordinate of Emperor Napoleon. He ...

, and Talleyrand, and they overthrew the Directory by a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

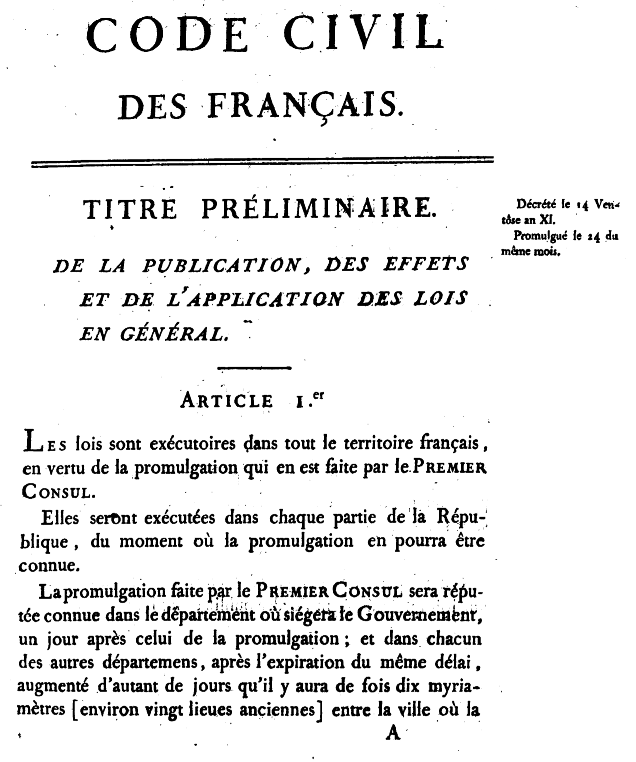

on 9 November 1799 ("the 18th Brumaire" according to the revolutionary calendar), closing down the Council of Five Hundred. Napoleon became "first consul" for ten years, with two consuls appointed by him who had consultative voices only. His power was confirmed by the new "Constitution of the Year VIII

The Constitution of the Year VIII (french: Constitution de l'an VIII or french: Constitution du 22 frimaire an VIII) was a national constitution of France, adopted on 24 December 1799 (during Year VIII of the French Republican calendar), which ...

", originally devised by Sieyès to give Napoleon a minor role, but rewritten by Napoleon, and accepted by direct popular vote (3,000,000 in favour, 1,567 opposed). The constitution preserved the appearance of a republic but, in reality, established a dictatorship.

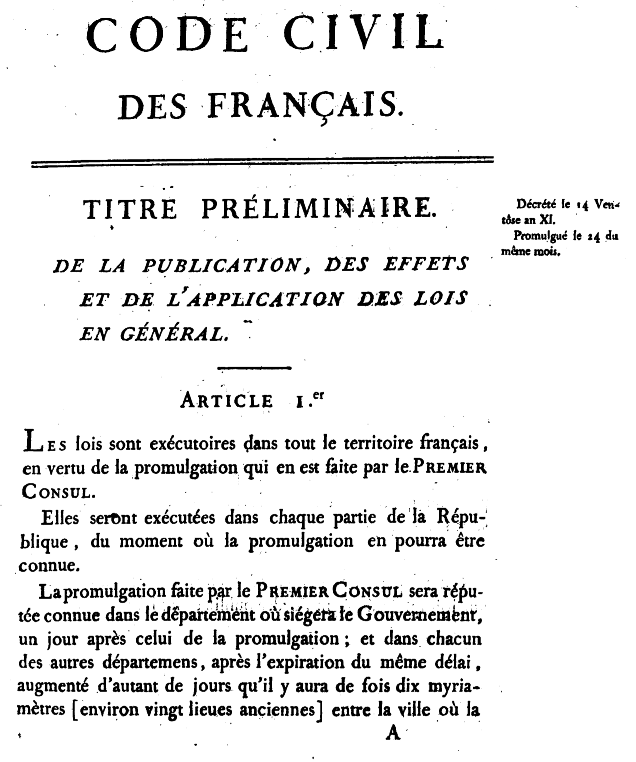

French Consulate

Napoleon established a political system that historian Martyn Lyons

Martyn Lyons (born 1946) is emeritus professor of history and European studies at the University of New South Wales

The University of New South Wales (UNSW), also known as UNSW Sydney, is a public research university based in Sydney, New So ...

called "dictatorship by plebiscite".Constitution of the Year VIII

The Constitution of the Year VIII (french: Constitution de l'an VIII or french: Constitution du 22 frimaire an VIII) was a national constitution of France, adopted on 24 December 1799 (during Year VIII of the French Republican calendar), which ...

and secured his own election as First Consul

The Consulate (french: Le Consulat) was the top-level Government of France from the fall of the Directory in the coup of 18 Brumaire on 10 November 1799 until the start of the Napoleonic Empire on 18 May 1804. By extension, the term ''The Con ...

, taking up residence at the Tuileries. The constitution was approved in a rigged plebiscite held the following January, with 99.94 percent officially listed as voting "yes".

Napoleon's brother, Lucien, had falsified the returns to show that 3 million people had participated in the plebiscite. The real number was 1.5 million.Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the List of cities in Italy, sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian ce ...

, which was besieged

Besieged may refer to:

* the state of being under siege

* ''Besieged'' (film), a 1998 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

{{disambiguation ...

by a substantial force. The fierce resistance of this French army, under André Masséna, gave the northern force some time to carry out their operations with little interference.Alessandria

Alessandria (; pms, Lissandria ) is a city and ''comune'' in Piedmont, Italy, and the capital of the Province of Alessandria. The city is sited on the alluvial plain between the Tanaro and the Bormida rivers, about east of Turin.

Alessandria ...

, leaving behind 14,000 casualties.Convention of Alessandria

The Convention of Alessandria (also known as the Armistice of Marengo) was an armistice signed on 15 June 1800 between the French First Republic led by Napoleon and Austria during the War of the Second Coalition. Following the Austrian defeat a ...

, which granted them safe passage to friendly soil in exchange for their fortresses throughout the region.David G. Chandler

David Geoffrey Chandler (15 January 1934 – 10 October 2004) was a British historian whose study focused on the Napoleonic era.

As a young man he served briefly in the army, reaching the rank of captain, and in later life he taught at the Roy ...

points out, Napoleon spent almost a year getting the Austrians out of Italy in his first campaign. In 1800, it took him only a month to achieve the same goal.Alfred von Schlieffen

Graf Alfred von Schlieffen, generally called Count Schlieffen (; 28 February 1833 – 4 January 1913) was a German field marshal and strategist who served as chief of the Imperial German General Staff from 1891 to 1906. His name lived on in the ...

concluded that "Bonaparte did not annihilate his enemy but eliminated him and rendered him harmless" while attaining "the object of the campaign: the conquest of North Italy".

Napoleon's triumph at Marengo secured his political authority and boosted his popularity back home, but it did not lead to an immediate peace. Bonaparte's brother, Joseph, led the complex negotiations in Lunéville

Lunéville ( ; German, obsolete: ''Lünstadt'' ) is a commune in the northeastern French department of Meurthe-et-Moselle.

It is a subprefecture of the department and lies on the river Meurthe at its confluence with the Vezouze.

History

Lun ...

and reported that Austria, emboldened by British support, would not acknowledge the new territory that France had acquired. As negotiations became increasingly fractious, Bonaparte gave orders to his general Moreau

Moreau may refer to:

People

*Moreau (surname)

Places

*Moreau, New York

*Moreau River (disambiguation)

Music

*An alternate name for the band Cousteau, used for the album ''Nova Scotia'' in the United States for legal reasons

In fiction

*Dr. Mo ...

to strike Austria once more. Moreau and the French swept through Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

and scored an overwhelming victory at Hohenlinden

Hohenlinden (meaning "high linden trees"; colloquially: ''Linden''; in the Bavarian dialect: ''Hea-lin'') is a community in the Upper Bavarian district of Ebersberg. The city of Lynden, Washington is named after it, as is Linden, Alabama. Hohe ...

in December 1800. As a result, the Austrians capitulated and signed the Treaty of Lunéville

The Treaty of Lunéville (or Peace of Lunéville) was signed in the Treaty House of Lunéville on 9 February 1801. The signatory parties were the French Republic and Emperor Francis II, who signed on his own behalf as ruler of the hereditary doma ...

in February 1801. The treaty reaffirmed and expanded earlier French gains at Campo Formio

Campoformido ( fur, Cjampfuarmit) is a town and ''comune'' in Friuli-Venezia Giulia, north-eastern Italy, with a population of 7743 (December 2019). It is notable for the Treaty of Campo Formio.

History

Campoformido is a village not far from Udi ...

.

Temporary peace in Europe

After a decade of constant warfare, France and Britain signed the Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition

The War of the Second Coalition (1798/9 – 1801/2, depending on perio ...

in March 1802, bringing the Revolutionary Wars to an end. Amiens called for the withdrawal of British troops from recently conquered colonial territories as well as for assurances to curtail the expansionary goals of the French Republic. The brief peace in Europe allowed Napoleon to focus on

The brief peace in Europe allowed Napoleon to focus on French colonies

From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire stretched from a total area at its peak in 1680 to over , the second largest empire in the world at the time behind only the Spanish Empire. During the 19th and 20th centuri ...

abroad. Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to refer ...

had managed to acquire a high level of political autonomy during the Revolutionary Wars, with Toussaint L'Ouverture

François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture (; also known as Toussaint L'Ouverture or Toussaint Bréda; 20 May 1743 – 7 April 1803) was a Haitian general and the most prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution. During his life, Louverture ...

installing himself as de facto dictator by 1801. Napoleon saw a chance to reestablish control over the colony when he signed the Treaty of Amiens. In the 18th century, Saint-Domingue had been France's most profitable colony, producing more sugar than all the British West Indies colonies combined. However, during the Revolution, the National Convention voted to abolish slavery in February 1794. Aware of the expenses required to fund his wars in Europe, Napoleon made the decision to reinstate slavery in all French Caribbean colonies. The 1794 decree had only affected the colonies of Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

and Guiana

The Guianas, sometimes called by the Spanish loan-word ''Guayanas'' (''Las Guayanas''), is a region in north-eastern South America which includes the following three territories:

* French Guiana, an overseas department and region of France

* ...

, and did not take effect in Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

, Reunion

Reunion may refer to:

* Class reunion

* Family reunion

Reunion, Réunion, Re-union, Reunions or The Reunion may also refer to:

Places

* Réunion, a French overseas department and island in the Indian Ocean

* Reunion, Commerce City, Colorado, U ...

and Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

, the last of which had been captured by the British and as such remained unaffected by French law.

In Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

slavery had been abolished (and its ban violently enforced) by Victor Hugues

Jean-Baptiste Victor Hugues sometimes spelled Hughes (July 20, 1762 in Marseille – August 12, 1826 in Cayenne) was a French politician and colonial administrator during the French Revolution, who governed Guadeloupe from 1794 to 1798, emancipa ...

against opposition from slaveholders thanks to the 1794 law. However, when slavery was reinstated in 1802, a slave revolt

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

broke out under the leadership of Louis Delgrès

Louis Delgrès (2 August 1766 – 28 May 1802) was a leader of the movement in Guadeloupe resisting reoccupation and thus the reinstitution of slavery by Napoleonic France in 1802.

Biography

Delgrès was mulatto, born free in Saint-Pierre, M ...

. The resulting Law of 20 May had the express purpose of reinstating slavery in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe and French Guiana, and restored slavery throughout most of the French colonial empire (excluding Saint-Domingue) for another half a century, while the French transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and i ...

continued for another twenty years.General Leclerc

Philippe François Marie Leclerc de Hauteclocque (22 November 1902 – 28 November 1947) was a Free-French general during the Second World War. He became Marshal of France posthumously in 1952, and is known in France simply as le maréchal ...

to reassert control over Saint-Domingue. Although the French managed to capture Toussaint Louverture, the expedition failed when high rates of disease crippled the French army, and Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines (Haitian Creole: ''Jan-Jak Desalin''; ; 20 September 1758 – 17 October 1806) was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent First Empire of Haiti, Haiti under the Constitution of Haiti, 1 ...

won a string of victories, first against Leclerc, and when he died from yellow fever, then against Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau

Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau (7 April 1755 – 20 October 1813) was a French military commander. He was the son of Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau.

Biography

He served in the American Revolution ...

, whom Napoleon sent to relieve Leclerc with another 20,000 men. In May 1803, Napoleon acknowledged defeat, and the last 8,000 French troops left the island and the slaves proclaimed an independent republic that they called Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

in 1804. In the process, Dessalines became arguably the most successful military commander in the struggle against Napoleonic France. Seeing the failure of his efforts in Haiti, Napoleon decided in 1803 to sell

Sell can refer to:

People

* Brenda Sell (born 1955), American martial arts instructor and highest ranking non-Korean female practitioner of taekwondo

* Brian Sell (born 1978), American retired long-distance runner

* Edward Sell (priest) (1839– ...

the Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

to the United States, instantly doubling the size of the U.S. The selling price in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

was less than three cents per acre, a total of $15 million.annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of Piedmont and his Act of Mediation

The Act of Mediation () was issued by Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul of the French Republic on 19 February 1803 establishing the Swiss Confederation. The act also abolished the previous Helvetic Republic, which had existed since the invasion ...

, which established a new Swiss Confederation

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

. Neither of these territories were covered by Amiens, but they inflamed tensions significantly. The dispute culminated in a declaration of war by Britain in May 1803; Napoleon responded by reassembling the invasion camp at Boulogne and declaring that every British male between eighteen and sixty years old in France and its dependencies to be arrested as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

.

French Empire

During the consulate, Napoleon faced several royalist and Jacobin assassination plots, including the ''

During the consulate, Napoleon faced several royalist and Jacobin assassination plots, including the ''Conspiration des poignards

The (from French, ) or () was an alleged assassination attempt against First Consul of France Napoleon Bonaparte. The members of the plot were not clearly established. Authorities at the time presented it as an assassination attempt on Napole ...

'' (Dagger plot) in October 1800 and the Plot of the Rue Saint-Nicaise

The Plot of the rue Saint-Nicaise, also known as the plot, was an assassination attempt on the First Consul of France, Napoleon Bonaparte, in Paris on 24 December 1800. It followed the of 10 October 1800, and was one of many Royalist and Cat ...

(also known as the ''Infernal Machine'') two months later. In January 1804, his police uncovered an assassination plot against him that involved Moreau and which was ostensibly sponsored by the Bourbon Bourbon may refer to:

Food and drink

* Bourbon whiskey, an American whiskey made using a corn-based mash

* Bourbon barrel aged beer, a type of beer aged in bourbon barrels

* Bourbon biscuit, a chocolate sandwich biscuit

* A beer produced by Bras ...