Nabulus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

dinner at the Park Hotel in Netanya—Israel launched Operation Defensive Shield, a major Battle of Nablus">military operation

A military operation is the coordinated military actions of a state, or a non-state actor, in response to a developing situation. These actions are designed as a military plan to resolve the situation in the state or actor's favor. Operations may ...

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem,

2007 Locality Population Statistics

.

''Anthropology and Global Counterinsurgency,''

pp.125-136 p.126. Nablus is under the administration of the

Flavia Neapolis ("new city of the emperor

Flavia Neapolis ("new city of the emperor  Conflict among the Christian population of Neapolis emerged in 451. By this time, Neapolis was within the

Conflict among the Christian population of Neapolis emerged in 451. By this time, Neapolis was within the

Neapolis, along with most of Palestine, was conquered by the Muslims under

Neapolis, along with most of Palestine, was conquered by the Muslims under

p. 55

He also noted that it was nicknamed "Little

– Nablus, At the Foot of the Holy Mountain

Med Cooperation, p.6. At the time, the linen produced in Nablus was well known throughout the

Crusader rule came to an end in 1187, when the

Crusader rule came to an end in 1187, when the

511

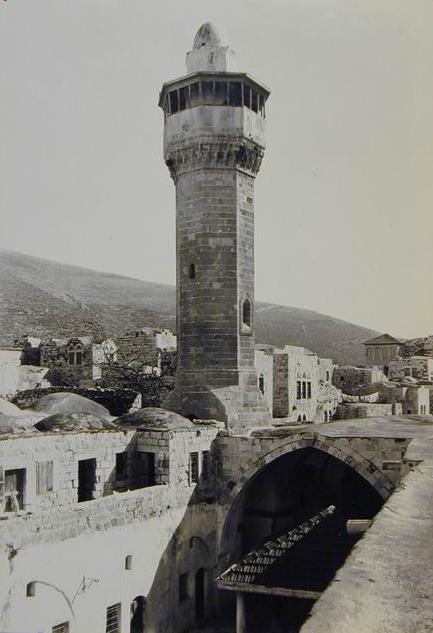

��515 After its recapture by the Muslims, the Great Mosque of Nablus, which had become a church under Crusader rule, was restored as a mosque by the Ayyubids, who also built a

In the mid-18th century,

In the mid-18th century,

In 1831–32 Khedivate Egypt, then led by

In 1831–32 Khedivate Egypt, then led by

Between 19 September and 25 September 1918, in the last months of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War the Battle of Nablus took place, together with the

Between 19 September and 25 September 1918, in the last months of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War the Battle of Nablus took place, together with the

The 1967

The 1967

Jurisdiction over the city was handed over to the

Jurisdiction over the city was handed over to the

''Building a Palestinian State: The Incomplete Revolution,''

Indiana University Press, 1997 p.57. and, located between two mountains, was closed off at both ends of the valley by Israeli checkpoints. For several years, movements in and out of the city were highly restricted. Nablus produced more

dinner at the Park Hotel in Netanya—Israel launched Operation Defensive Shield">san in the Hebrew c ...ISO 259-3

ISO 259 is a series of international standards for the romanization of Hebrew characters into Latin characters, dating to 1984, with updated ISO 259-2 (a simplification, disregarding several vowel signs, 1994) and ISO 259-3 (Phonemic Conversion, ...

: ; Samaritan Hebrew

Samaritan Hebrew () is a reading tradition used liturgically by the Samaritans for reading the Ancient Hebrew language of the Samaritan Pentateuch, in contrast to Tiberian Hebrew among the Jews.

For the Samaritans, Ancient Hebrew ceased to be a ...

: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

city in the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

, located approximately north of Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, with a population of 126,132.PCBS02007 Locality Population Statistics

.

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS; ar, الجهاز المركزي للإحصاء الفلسطيني) is the official

statistical institution of the State of Palestine. Its main task is to provide credible statistical figures a ...

(PCBS). Located between Mount Ebal

Mount Ebal ( he, ''Har ʿĒyḇāl''; ar, جبل عيبال ''Jabal ‘Aybāl'') is one of the two mountains in the immediate vicinity of the city of Nablus in the West Bank (biblical ''Shechem''), and forms the northern side of the valley in ...

and Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

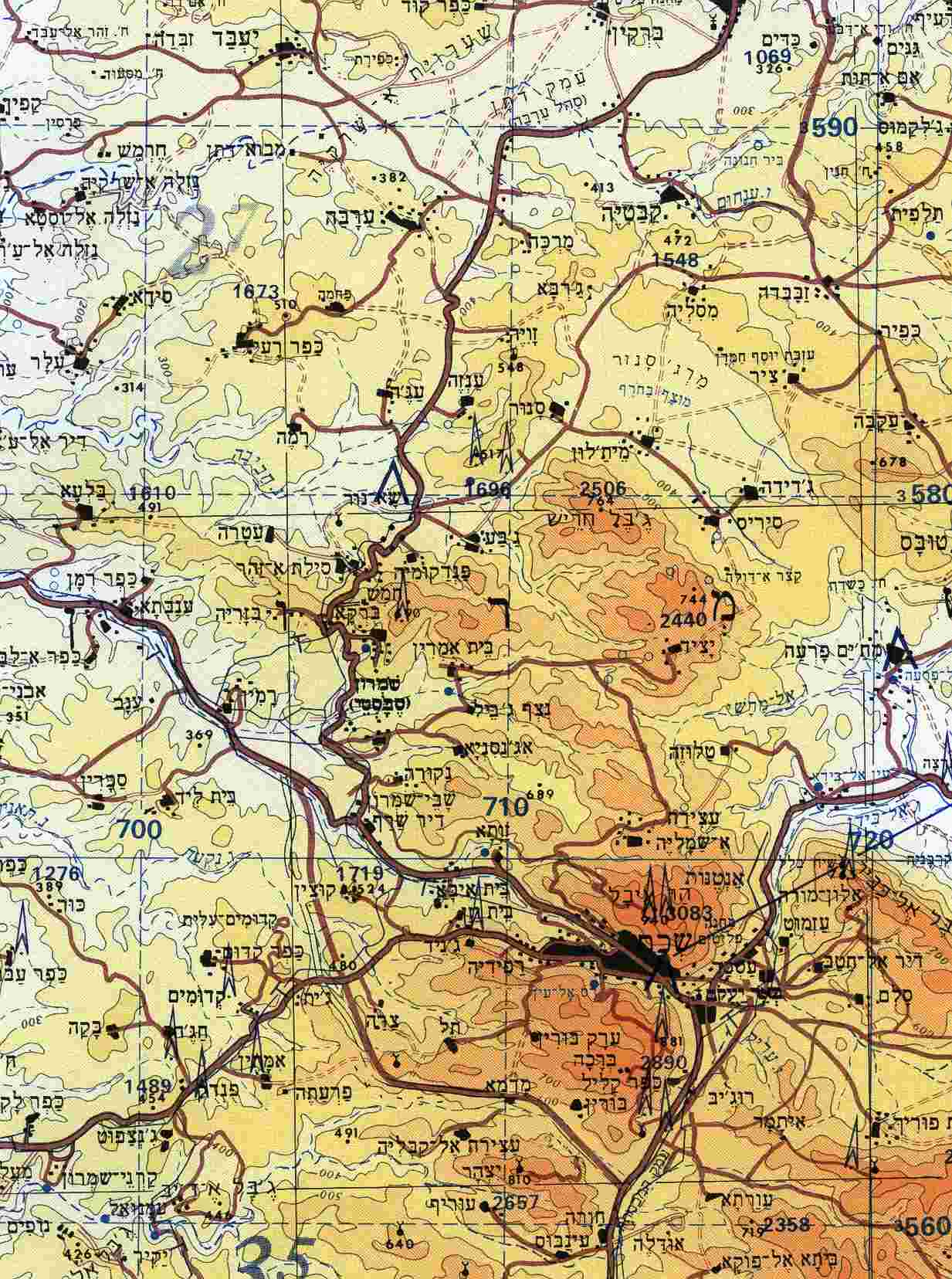

, it is the capital of the Nablus Governorate

The Nablus Governorate ( ar, محافظة نابلس ') is an administrative district of State of Palestine, Palestine located in the Central Highlands of the West Bank, 53 km north of Jerusalem. It covers the area around the city of Nablus ...

and a commercial and cultural centre of the State of Palestine

Palestine ( ar, فلسطين, Filasṭīn), Legal status of the State of Palestine, officially the State of Palestine ( ar, دولة فلسطين, Dawlat Filasṭīn, label=none), is a state (polity), state located in Western Asia. Officiall ...

, home to An-Najah National University

An-Najah National University ( ar, جامعة النجاح الوطنية) is a Palestinian non-governmental public university governed by a board of trustees. It is located in Nablus, in the northern West Bank. The university has 22,000 studen ...

, one of the largest Palestinian institutions of higher learning, and the Palestine Stock Exchange.Amahl Bishara, ‘Weapons, Passports and News: Palestinian Perceptions of U.S. Power as a Mediator of War,’ in John D. Kelly, Beatrice Jauregui, Sean T. Mitchell, Jeremy Walton (eds.''Anthropology and Global Counterinsurgency,''

pp.125-136 p.126. Nablus is under the administration of the

Palestinian National Authority

The Palestinian National Authority (PA or PNA; ar, السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية '), commonly known as the Palestinian Authority and officially the State of Palestine,

as part of Area A of the West Bank.

The city traces its modern name back to the Roman period

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

, when it was named ''Flavia Neapolis'' by Roman emperor Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empi ...

in 72 CE. During the Byzantine period

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

, conflict between the city's Samaritan and newer Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

inhabitants peaked in the Samaritan revolts

The Samaritan revolts (c. 484–573) were a series of insurrections in Palaestina Prima province, launched by the Samaritans against the Eastern Roman Empire. The revolts were marked by great violence on both sides, and their brutal suppression ...

that were eventually suppressed by the Byzantines by 573, which greatly dwindled the Samaritan population of the city. Following the Arab-Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 7th century, the city was given its present-day Arabic name of ''Nablus''. After the First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ru ...

, the Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

drafted the laws of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establishe ...

in the Council of Nablus

The Council of Nablus was a council of ecclesiastic and secular lords in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, held on January 16, 1120.

History

The council was convened at Nablus by Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, and King Baldwin II of Jerusalem. ...

, and its Christian, Samaritan, and Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

inhabitants prospered. The city then came under the control of the Ayyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin h ...

and the Mamluk Sultanate

The Mamluk Sultanate ( ar, سلطنة المماليك, translit=Salṭanat al-Mamālīk), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (western Arabia) from the mid-13th to early 16th ...

. Under the Ottoman Turk

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

s, who conquered the city in 1517, Nablus served as the administrative and commercial centre for the surrounding area corresponding to the modern-day northern West Bank.

After the city was captured by British forces

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, s ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Nablus was incorporated into the British Mandate of Palestine British Mandate of Palestine or Palestine Mandate most often refers to:

* Mandate for Palestine: a League of Nations mandate under which the British controlled an area which included Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan.

* Mandatory P ...

in 1922. The 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

saw the entire West Bank, including Nablus, occupied and annexed by Transjordan Transjordan may refer to:

* Transjordan (region), an area to the east of the Jordan River

* Oultrejordain, a Crusader lordship (1118–1187), also called Transjordan

* Emirate of Transjordan, British protectorate (1921–1946)

* Hashemite Kingdom of ...

. Since the 1967 Arab–Israeli War, the West Bank has been occupied by Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

; since 1995, it has been governed by the PNA as part of Area A of the West Bank. Today, the population is predominantly Muslim, with small Christian and Samaritan minorities.

History

Classical antiquity

Flavia Neapolis ("new city of the emperor

Flavia Neapolis ("new city of the emperor Flavius

The gens Flavia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Its members are first mentioned during the last three centuries of the Republic. The first of the Flavii to achieve prominence was Marcus Flavius, tribune of the plebs in 327 and 323 BC; ...

") was named in 72 CE by the Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

emperor Vespasian

Vespasian (; la, Vespasianus ; 17 November AD 9 – 23/24 June 79) was a Roman emperor who reigned from AD 69 to 79. The fourth and last emperor who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty that ruled the Empi ...

and applied to an older Samaritan village, variously called ''Mabartha'' ("the passage")Negev and Gibson, 2005, p. 175. or ''Mamorpha''. Located between Mount Ebal

Mount Ebal ( he, ''Har ʿĒyḇāl''; ar, جبل عيبال ''Jabal ‘Aybāl'') is one of the two mountains in the immediate vicinity of the city of Nablus in the West Bank (biblical ''Shechem''), and forms the northern side of the valley in ...

and Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

, the new city lay west of the Biblical

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

city of Shechem

Shechem ( ), also spelled Sichem ( ; he, שְׁכֶם, ''Šəḵem''; ; grc, Συχέμ, Sykhém; Samaritan Hebrew: , ), was a Canaanite and Israelite city mentioned in the Amarna Letters, later appearing in the Hebrew Bible as the first cap ...

which was destroyed by the Romans that same year during the First Jewish–Roman War

The First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), sometimes called the Great Jewish Revolt ( he, המרד הגדול '), or The Jewish War, was the first of three major rebellions by the Jews against the Roman Empire, fought in Roman-controlled ...

. Holy places at the site of the city's founding include Joseph's Tomb

Joseph's Tomb ( he, קבר יוסף, ''Qever Yosef''; ar, قبر يوسف, ''Qabr Yūsuf'') is a funerary monument located in Balata village at the eastern entrance to the valley that separates Mounts Gerizim and Ebal, 300 metres northwest of ...

and Jacob's Well

Jacob's Well ( ar, بِئْر يَعْقُوب, Biʾr Yaʿqūb; gr, Φρέαρ του Ιακώβ, Fréar tou Iakóv; he, באר יעקב, Beʾer Yaʿaqov), also known as Jacob's fountain and Well of Sychar, is a deep well constructed into ...

. Because of the city's strategic geographic position and the abundance of water from nearby springs, Neapolis prospered, accumulating extensive territory, including the former Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous L ...

n toparchy

''Toparchēs'' ( el, τοπάρχης, "place-ruler"), anglicized as toparch, is a Greek term for a governor or ruler of a district and was later applied to the territory where the toparch exercised his authority. In Byzantine times the term came t ...

of Acraba.

Insofar as the hilly topography of the site would allow, the city was built on a Roman grid plan

In urban planning, the grid plan, grid street plan, or gridiron plan is a type of city plan in which streets run at right angles to each other, forming a grid.

Two inherent characteristics of the grid plan, frequent intersections and orthogona ...

and settled with veterans who fought in the victorious legions and other foreign colonists. In the 2nd century CE, Emperor Hadrian

Hadrian (; la, Caesar Trâiānus Hadriānus ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. He was born in Italica (close to modern Santiponce in Spain), a Roman ''municipium'' founded by Italic settlers in Hispania B ...

built a grand theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actor, actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The p ...

in Neapolis that could seat up to 7,000 people. Coins found in Nablus dating to this period depict Roman military emblems and gods and goddesses of the Greek pantheon such as Zeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

, Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified wit ...

, Serapis

Serapis or Sarapis is a Graeco-Egyptian deity. The cult of Serapis was promoted during the third century BC on the orders of Greek Pharaoh Ptolemy I Soter of the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Egypt as a means to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his r ...

, and Asklepios

Asclepius (; grc-gre, Ἀσκληπιός ''Asklēpiós'' ; la, Aesculapius) is a hero and god of medicine in ancient Religion in ancient Greece, Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology. He is the son of Apollo and Coronis (lover of ...

. Neapolis was entirely pagan

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. ...

at this time. Justin Martyr

Justin Martyr ( el, Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς, Ioustinos ho martys; c. AD 100 – c. AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and ...

who was born in the city c. 100 CE, came into contact with Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at le ...

, but not with Christians there. The city flourished until the civil war between Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa (Roman province), Africa. As a young man he advanced thro ...

and Pescennius Niger

Gaius Pescennius Niger (c. 135 – 194) was Roman Emperor from 193 to 194 during the Year of the Five Emperors. He claimed the imperial throne in response to the murder of Pertinax and the elevation of Didius Julianus, but was defeated by a riva ...

in 198–9 CE. Having sided with Niger, who was defeated, the city was temporarily stripped of its legal privileges by Severus, who designated these to Sebastia instead.

In 244 CE, Philip the Arab

Philip the Arab ( la, Marcus Julius Philippus "Arabs"; 204 – September 249) was Roman emperor from 244 to 249. He was born in Aurantis, Arabia, in a city situated in modern-day Syria. After the death of Gordian III in February 244, Philip ...

transformed Flavius Neapolis into a Roman colony named ''Julia Neapolis''. It retained this status until the rule of Trebonianus Gallus

Gaius Vibius Trebonianus Gallus (206 – August 253) was Roman emperor from June 251 to August 253, in a joint rule with his son Volusianus.

Early life

Gallus was born in Italy, in a family with respected Etruscan senatorial background. He had ...

in 251 CE. The ''Encyclopaedia Judaica'' speculates that Christianity was dominant in the 2nd or 3rd century, with some sources positing a later date of 480 CE. It is known for certain that a bishop from Nablus participated in the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE.Negev and Gibson, 2005, p. 176. The presence of Samaritans in the city is attested to in literary and epigraphic evidence dating to the 4th century CE. As yet, there is no evidence attesting to a Jewish presence in ancient Neapolis.

Palaestina Prima

Palaestina Prima or Palaestina I was a Byzantine province that existed from the late 4th century until the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 630s, in the region of Palestine. It was temporarily lost to the Sassanid Empire (Persian Empire) in ...

province under the rule of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

. The tension was a result of Monophysite

Monophysitism ( or ) or monophysism () is a Christological term derived from the Greek (, "alone, solitary") and (, a word that has many meanings but in this context means "nature"). It is defined as "a doctrine that in the person of the incarn ...

Christian attempts to prevent the return of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the ''Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

, to his episcopal see

An episcopal see is, in a practical use of the phrase, the area of a bishop's ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Phrases concerning actions occurring within or outside an episcopal see are indicative of the geographical significance of the term, mak ...

. However, the conflict did not grow into civil strife.

As tensions among the Christians of Neapolis decreased, tensions between the Christian community and the Samaritans

Samaritans (; ; he, שומרונים, translit=Šōmrōnīm, lit=; ar, السامريون, translit=as-Sāmiriyyūn) are an ethnoreligious group who originate from the ancient Israelites. They are native to the Levant and adhere to Samarit ...

grew dramatically. In 484, the city became the site of a deadly encounter between the two groups, provoked by rumors that the Christians intended to transfer the remains of Aaron

According to Abrahamic religions, Aaron ''′aharon'', ar, هارون, Hārūn, Greek (Septuagint): Ἀαρών; often called Aaron the priest ()., group="note" ( or ; ''’Ahărōn'') was a prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of ...

's sons and grandsons Eleazar

Eleazar (; ) or Elʽazar was a priest in the Hebrew Bible, the second High Priest, succeeding his father Aaron after he died. He was a nephew of Moses.

Biblical narrative

Eleazar played a number of roles during the course of the Exodus, from c ...

, Ithamar

In the Torah, Ithamar () was the fourth (and the youngest) son of Aaron the High Priest."Ithamar", '' Encyclopaedia Biblica'' Following the construction of the Tabernacle, he was responsible for recording an inventory to ensure that the constructed ...

and Phinehas

According to the Hebrew Bible, Phinehas or Phineas (; , ''Phinees'', ) was a priest during the Israelites’ Exodus journey. The grandson of Aaron and son of Eleazar, the High Priests (), he distinguished himself as a youth at Shittim with h ...

. Samaritans reacted by entering the cathedral of Neapolis, killing the Christians inside and severing the fingers of the bishop Terebinthus. Terebinthus then fled to Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, requesting an army garrison to prevent further attacks. As a result of the revolt, the Byzantine emperor Zeno

Zeno ( grc, Ζήνων) may refer to:

People

* Zeno (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

Philosophers

* Zeno of Elea (), philosopher, follower of Parmenides, known for his paradoxes

* Zeno of Citium (333 – 264 BC), ...

erected a church dedicated to Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

on Mount Gerizim. He also forbade the Samaritans to travel to the mountain to celebrate their religious ceremonies, and expropriated their synagogue there. These actions by the emperor fueled Samaritan anger towards the Christians further.

Thus, the Samaritans rebelled again under the rule of emperor Anastasius I, reoccupying Mount Gerizim, which was subsequently reconquered by the Byzantine governor of Edessa

Edessa (; grc, Ἔδεσσα, Édessa) was an ancient city (''polis'') in Upper Mesopotamia, founded during the Hellenistic period by King Seleucus I Nicator (), founder of the Seleucid Empire. It later became capital of the Kingdom of Osroene ...

, Procopius. A third Samaritan revolt which took place under the leadership of Julianus ben Sabar

Julianus ben Sabar (also known as Julian or Julianus ben Sahir and Latinized as ''Iulianus Sabarides'') was a leader of the Samaritans, seen widely as being the Taheb who led a failed revolt against the Byzantine Empire during the early 6th c ...

in 529 was perhaps the most violent. Neapolis' bishop Ammonas

Ammon, Amun ( cop, Ⲁⲃⲃⲁ Ⲁⲙⲟⲩⲛ), Ammonas ( grc-gre, Ἀμμώνας), Amoun (), or Ammonius the Hermit (; el, Ἀμμώνιος) was a 4th-century Christian ascetic and the founder of one of the most celebrated monastic commu ...

was murdered and the city's priests were hacked into pieces and then burned together with the relics of saint

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of Q-D-Š, holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and Christian denomination, denominat ...

s. The forces of Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

were sent in to quell the revolt, which ended with the slaughter of the majority of the Samaritan population in the city.

Early Islamic era

Khalid ibn al-Walid

Khalid ibn al-Walid ibn al-Mughira al-Makhzumi (; died 642) was a 7th-century Arab military commander. He initially headed campaigns against Muhammad on behalf of the Quraysh. He later became a Muslim and spent the remainder of his career in ...

, a general of the Rashidun army

The Rashidun army () was the core of the Rashidun Caliphate's armed forces during the early Muslim conquests in the 7th century. The army is reported to have maintained a high level of discipline, strategic prowess and organization, granti ...

of Umar ibn al-Khattab

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate o ...

, in 636 after the Battle of Yarmouk

The Battle of the Yarmuk (also spelled Yarmouk) was a major battle between the army of the Byzantine Empire and the Muslim forces of the Rashidun Caliphate. The battle consisted of a series of engagements that lasted for six days in August 636, ...

. The city's name was retained in its Arabicized form, ''Nabulus''. The town prevailed as an important trade center during the centuries of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

ic Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

rule under the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

, Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

and Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dy ...

dynasties.

Under Muslim rule, Nablus contained a diverse population of Arabs and Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

s, Muslims, Samaritans, Christians and Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

s. In the 9th century CE, Al-Yaqubi

ʾAbū l-ʿAbbās ʾAḥmad bin ʾAbī Yaʿqūb bin Ǧaʿfar bin Wahb bin Waḍīḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (died 897/8), commonly referred to simply by his nisba al-Yaʿqūbī, was an Arab Muslim geographer and perhaps the first historian of world cult ...

reported that Nablus had a mixed population of Arabs, Ajam

''Ajam'' ( ar, عجم, ʿajam) is an Arabic word meaning mute, which today refers to someone whose mother tongue is not Arabic. During the Arab conquest of Persia, the term became a racial pejorative. In many languages, including Persian, Tur ...

(Non-Arabs), and Samaritans. In the 10th century, the Arab geographer al-Muqaddasi

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Abī Bakr al-Maqdisī ( ar, شَمْس ٱلدِّيْن أَبُو عَبْد ٱلله مُحَمَّد ابْن أَحْمَد ابْن أَبِي بَكْر ٱلْمَقْدِسِي), ...

, described it as abundant of olive trees, with a large marketplace, a finely paved Great Mosque, houses built of stone, a stream running through the center of the city, and notable mills.Muqaddasip. 55

He also noted that it was nicknamed "Little

Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

."Semplici, Andrea and Boccia, Mario– Nablus, At the Foot of the Holy Mountain

Med Cooperation, p.6. At the time, the linen produced in Nablus was well known throughout the

Old World

The "Old World" is a term for Afro-Eurasia that originated in Europe , after Europeans became aware of the existence of the Americas. It is used to contrast the continents of Africa, Europe, and Asia, which were previously thought of by the ...

.

Crusader period

The city was captured byCrusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

in 1099, under the command of Prince Tancred, and renamed ''Naples''. Though the Crusaders extorted many supplies from the population for their troops who were en route to Jerusalem, they did not sack the city, presumably because of the large Christian population there. Nablus became part of the royal domain

Crown land (sometimes spelled crownland), also known as royal domain, is a territorial area belonging to the monarch, who personifies the Crown. It is the equivalent of an entailed estate and passes with the monarchy, being inseparable from it ...

of the Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem ( la, Regnum Hierosolymitanum; fro, Roiaume de Jherusalem), officially known as the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem or the Frankish Kingdom of Palestine,Example (title of works): was a Crusader state that was establishe ...

. The Muslim, Eastern Orthodox Christian, and Samaritan populations remained in the city and were joined by some Crusaders who settled therein to take advantage of the city's abundant resources. In 1120, the Crusaders convened the Council of Nablus

The Council of Nablus was a council of ecclesiastic and secular lords in the crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem, held on January 16, 1120.

History

The council was convened at Nablus by Warmund, Patriarch of Jerusalem, and King Baldwin II of Jerusalem. ...

out of which was issued the first written laws for the kingdom. They converted the Samaritan synagogue in Nablus into a church. The Samaritan community built a new synagogue in the 1130s. In 1137, Arab and Turkish troops stationed in Damascus

)), is an adjective which means "spacious".

, motto =

, image_flag = Flag of Damascus.svg

, image_seal = Emblem of Damascus.svg

, seal_type = Seal

, map_caption =

, ...

raided Nablus, killing many Christians and burning down the city's churches. However, they were unsuccessful in retaking the city. Queen Melisende of Jerusalem

Melisende (1105 – 11 September 1161) was Queen of Jerusalem from 1131 to 1153, and regent for her son between 1153 and 1161, while he was on campaign. She was the eldest daughter of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, and the Armenian princess M ...

resided in Nablus from 1150 to 1161, after she was granted control over the city in order to resolve a dispute with her son Baldwin III. Crusaders began building Christian institutions in Nablus, including a church dedicated to the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, and in 1170 they erected a hospice for pilgrims.

Ayyubid and Mamluk rule

Ayyubid

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni ...

s led by Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

captured the city. According to a liturgical manuscript in Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

, Latin Christians

, native_name_lang = la

, image = San Giovanni in Laterano - Rome.jpg

, imagewidth = 250px

, alt = Façade of the Archbasilica of St. John in Lateran

, caption = Archbasilica of Saint Joh ...

fled Nablus, but the original Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first millennium, the mainstream (or "canonical") ...

Christian inhabitants remained. Syrian geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi

Yāqūt Shihāb al-Dīn ibn-ʿAbdullāh al-Rūmī al-Ḥamawī (1179–1229) ( ar, ياقوت الحموي الرومي) was a Muslim scholar of Byzantine Greek ancestry active during the late Abbasid period (12th-13th centuries). He is known fo ...

(1179–1229), wrote that Ayyubid Nablus was a "celebrated city in Filastin (Palestine)... having wide lands and a fine district." He also mentions the large Samaritan population in the city.Le Strange, 1890, pp511

��515 After its recapture by the Muslims, the Great Mosque of Nablus, which had become a church under Crusader rule, was restored as a mosque by the Ayyubids, who also built a

mausoleum

A mausoleum is an external free-standing building constructed as a monument enclosing the interment space or burial chamber of a deceased person or people. A mausoleum without the person's remains is called a cenotaph. A mausoleum may be consid ...

in the old city.

In October 1242, Nablus was raided by the Knights Templar

, colors = White mantle with a red cross

, colors_label = Attire

, march =

, mascot = Two knights riding a single horse

, equipment ...

. This was the conclusion of the 1242 campaign season in which the Templars had joined forces with the Ayyubid emir of Kerak, An-Nasir Dawud

An-Nasir Dawud (1206–1261) was a Kurdish ruler, briefly (1227–1229) Ayyubid sultan of Damascus and later (1229–1248) Emir of Kerak.

An-Nasir Dawud was the son of Al-Mu'azzam, the Ayyubid Sultan of Damascus from 1218 to 1227. On his fathe ...

, against the Mamluks. The Templars raided Nablus in revenge for a previous massacre of Christians by their erstwhile ally An-Nasir Dawud. The attack is reported as a particularly bloody affair lasting for three days, during which the Mosque was burned and many residents of the city, Christians alongside Muslims, were killed or sold in the slave markets of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

.

The successful raid was widely publicized by the Templars in Europe; it is thought to be depicted in a late 13th-century fresco in the Templar church of San Bevignate, Perugia

Perugia (, , ; lat, Perusia) is the capital city of Umbria in central Italy, crossed by the River Tiber, and of the province of Perugia.

The city is located about north of Rome and southeast of Florence. It covers a high hilltop and part o ...

.

In 1244, the Samaritan synagogue, built in 362 by the high priest Akbon and converted into a church by the Crusaders, was converted into al-Khadra Mosque

Al-Khadra Mosque ( ar, مسجد الخضرة, translit=Masjid al-Khadra, lit=the Green Mosque) also known as Hizn Sidna Yaq'ub Mosque (trans. ''Sadness of our Lord Jacob''), is a mosque situated on the lower slopes of Mount Gerizim in the southwes ...

. Two other Crusader churches became the An-Nasr Mosque and al-Masakim Mosque during that century.

The Mamluk dynasty gained control of Nablus in 1260 and during their reign, they built numerous mosques and schools. Under Mamluk rule, Nablus possessed running water, many Turkish bath

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited ...

s and exported olive oil and soap

Soap is a salt of a fatty acid used in a variety of cleansing and lubricating products. In a domestic setting, soaps are surfactants usually used for washing, bathing, and other types of housekeeping. In industrial settings, soaps are use ...

to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Syria, the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

, several Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

islands, and the Arabian Desert. The city's olive oil was also used in the Umayyad Mosque

The Umayyad Mosque ( ar, الجامع الأموي, al-Jāmiʿ al-Umawī), also known as the Great Mosque of Damascus ( ar, الجامع الدمشق, al-Jāmiʿ al-Damishq), located in the old city of Damascus, the capital of Syria, is one of the ...

in Damascus. Ibn Battuta

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Battutah (, ; 24 February 13041368/1369),; fully: ; Arabic: commonly known as Ibn Battuta, was a Berbers, Berber Maghrebi people, Maghrebi scholar and explorer who travelled extensively in the lands of Afro-Eurasia, ...

, the Arab explorer, visited Nablus in 1355, and described it as a city "full of trees and streams and full of olives." He noted that the city grew and exported carob

The carob ( ; ''Ceratonia siliqua'') is a flowering evergreen tree or shrub in the Caesalpinioideae sub-family of the legume family, Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated for its edible fruit pods, and as an ornamental tree in gardens and landscap ...

jam to Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

and Damascus.

Ottoman era

Nablus came under the rule of theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in 1517, along with the whole of Palestine. The Ottomans divided Palestine into six '' sanjaqs'' ("districts"): Safad

Safed (known in Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevat ...

, Jenin

Jenin (; ar, ') is a Palestinian city in the northern West Bank. It serves as the administrative center of the Jenin Governorate of the State of Palestine and is a major center for the surrounding towns. In 2007, Jenin had a population of app ...

, Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, Gaza, Ajlun

Ajloun ( ar, عجلون, ''‘Ajlūn''), also spelled Ajlun, is the capital town of the Ajloun Governorate, a hilly town in the north of Jordan, located 76 kilometers (around 47 miles) north west of Amman. It is noted for its impressive ruins of t ...

and Nablus

Nablus ( ; ar, نابلس, Nābulus ; he, שכם, Šəḵem, ISO 259-3: ; Samaritan Hebrew: , romanized: ; el, Νεάπολις, Νeápolis) is a Palestinian city in the West Bank, located approximately north of Jerusalem, with a populati ...

, all of which were part of Ottoman Syria

Ottoman Syria ( ar, سوريا العثمانية) refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of Syria, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south ...

. These five ''sanjaqs'' were subdistricts of the Vilayet of Damascus. Sanjaq Nablus was further subdivided into five ''nahiya

A nāḥiyah ( ar, , plural ''nawāḥī'' ), also nahiya or nahia, is a regional or local type of administrative division that usually consists of a number of villages or sometimes smaller towns. In Tajikistan, it is a second-level division w ...

'' (subdistricts), in addition to the city itself. The Ottomans did not attempt to restructure the political configuration of the region on the local level such that the borders of the ''nahiya'' were drawn to coincide with the historic strongholds of certain families. Nablus was only one among a number of local centers of power within Jabal Nablus, and its relations with the surrounding villages, such as Beita and Aqraba, were partially mediated by the rural-based chiefs of the ''nahiya''.Doumani, 1995, Chapter: "The 1657 Campaign." During the 16th century, the population was predominantly Muslim, with Jewish, Samaritan and Christian minorities.

After decades of upheavals and rebellions mounted by Arab tribes in the Middle East, the Ottomans attempted to reassert centralized control over the Arab ''vilayets''. In 1657, they sent an expeditionary force led mostly by Arab ''sipahi

''Sipahi'' ( ota, سپاهی, translit=sipâhi, label=Persian, ) were professional cavalrymen deployed by the Seljuk dynasty, Seljuks, and later the Ottoman Empire, including the land grant-holding (''timar'') provincial ''Timariots, timarli s ...

'' officers from central Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

to reassert Ottoman authority in Nablus and its hinterland, as part of a broader attempt to established centralized rule throughout the empire at that time. In return for their services, the officers were granted agricultural lands around the villages of Jabal Nablus. The Ottomans, fearing that the new Arab land holders would establish independent bases of power, dispersed the land plots to separate and distant locations within Jabal Nablus to avoid creating contiguous territory controlled by individual clans. Contrary to its centralization purpose, the 1657 campaign allowed the Arab ''sipahi'' officers to establish their own increasingly autonomous foothold in Nablus. The officers raised their families there and intermarried with the local notables of the area, namely the ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

and merchant families. Without abandoning their nominal military service, they acquired diverse properties to consolidate their presence and income such as soap and pottery factories, bathhouses, agricultural lands, grain mills and, olive and sesame oil presses.

The most influential military family were the Nimrs, who were originally local governors of Homs

Homs ( , , , ; ar, حِمْص / ALA-LC: ; Levantine Arabic: / ''Ḥomṣ'' ), known in pre-Islamic Syria as Emesa ( ; grc, Ἔμεσα, Émesa), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level ...

and Hama

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

's rural subdistricts. Other officer families included the Akhrami, Asqalan, Bayram, Jawhari, Khammash, Mir'i, Shafi, Sultan and Tamimi families, some of which remained in active service, while some left service for other pursuits. In the years following the 1657 campaign, two other families migrated to Nablus: the Jarrars from Balqa and the Tuqans from northern Syria or Transjordan. The Jarrars came to dominate the hinterland of Nablus, while the Tuqans and Nimrs competed for influence in the town. The former held the post of '' mutasallim'' (tax collector, strongman) of Nablus longer, though non-consecutively than any other family. The three families maintained their power until the mid-19th century.

In the mid-18th century,

In the mid-18th century, Zahir al-Umar

Zahir al-Umar al-Zaydani, alternatively spelled Daher al-Omar or Dahir al-Umar ( ar, ظاهر العمر الزيداني, translit=Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar az-Zaydānī, 1689/90 – 21 or 22 August 1775) was the autonomous Arab ruler of northern Ottom ...

, the autonomous Arab ruler of the Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

became a dominant figure in Palestine. To build up his army, he strove to gain a monopoly over the cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus ''Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor perce ...

and olive oil trade of the southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a Region, geographical region encompassing the southern half of the Levant. It corresponds approximately to modern-day Israel, State of Palestine, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southe ...

, including Jabal Nablus, which was a major producer of both crops. In 1771, during the Egyptian Mamluk invasion of Syria, Zahir aligned himself with the Mamluks and besieged Nablus, but did not succeed in taking the city. In 1773, he tried again without success. Nevertheless, from a political perspective, the sieges led to a decline in the importance of the city in favor of Acre. Zahir's successor, Jezzar Pasha

Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar ( ar, أحمد باشا الجزّار; ota, جزّار أحمد پاشا; ca. 1720–30s7 May 1804) was the Acre-based Ottoman governor of Sidon Eyalet from 1776 until his death in 1804 and the simultaneous governor of D ...

, maintained Acre's dominance over Nablus. After his reign ended in 1804, Nablus regained its autonomy, and the Tuqans, who represented a principal opposing force, rose to power.

Egyptian rule and Ottoman revival

In 1831–32 Khedivate Egypt, then led by

In 1831–32 Khedivate Egypt, then led by Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, a ...

, conquered Palestine from the Ottomans. A policy of conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

and new taxation

A tax is a compulsory financial charge or some other type of levy imposed on a taxpayer (an individual or legal person, legal entity) by a governmental organization in order to fund government spending and various public expenditures (regiona ...

was instituted which led to a revolt

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

organized by the '' a'ayan'' (notables) of Nablus, Hebron

Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after East J ...

and the Jerusalem-Jaffa area. In May 1834, Qasim al-Ahmad

Qasim Pasha al-Ahmad (died 1834) was the chief of the Jamma'in subdistrict of Jabal Nablus during the Ottoman and Egyptian periods in Palestine in the mid-19th century.Doumani, 1995, p.46/ref> He also served as the '' mutassalim'' (tax collecto ...

—the chief of the Jamma'in

Jamma'in ( ar, جمّاعين) is a Palestinian people, Palestinian town in the northern West Bank located southwest of Nablus, northwest of Salfit and north of Ramallah. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the town had a ...

''nahiya''—rallied the rural sheikhs and ''fellahin

A fellah ( ar, فَلَّاح ; feminine ; plural ''fellaheen'' or ''fellahin'', , ) is a peasant, usually a farmer or agricultural laborer in the Middle East and North Africa. The word derives from the Arabic word for "ploughman" or "tiller". ...

'' (peasants) of Jabal Nablus and launched a revolt against Governor Ibrahim Pasha, in protest at conscription orders, among other new policies. The leaders of Nablus and its hinterland sent thousands of rebels to attack Jerusalem, the center of government authority in Palestine, aided by the Abu Ghosh clan, and they conquered the city on 31 May. However, they were later defeated by Ibrahim Pasha's forces the next month. Ibrahim then forced the heads of the Jabal Nablus clans to leave for nearby villages. By the end of August, the countrywide revolt had been suppressed and Qasim was executed.Doumani, 1995, Chapter: "Egyptian rule, 1831–1840."

Egyptian rule in Palestine resulted in the destruction of Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

and thus, the political importance of Nablus was further elevated. The Ottomans wrested back control of Palestine from Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

in 1840–41. However, the Arraba Arraba ( ar, عرّابة) can refer to the following:

*Arraba, Israel

*Arraba, Jenin Other

*Arabah See also

*Araba (disambiguation) Araba may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions

* the Ancient Arab Kingdom of Hatra, a Roman-Parthian buffer state ...

-based Abd al-Hadi clan which rose to prominence under Egyptian rule for supporting Ibrahim Pasha, continued its political dominance in Jabal Nablus.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Nablus was the principal trade and manufacturing center in Ottoman Syria. Its economic activity and regional leadership position surpassed that of Jerusalem and the coastal cities of Jaffa

Jaffa, in Hebrew Yafo ( he, יָפוֹ, ) and in Arabic Yafa ( ar, يَافَا) and also called Japho or Joppa, the southern and oldest part of Tel Aviv-Yafo, is an ancient port city in Israel. Jaffa is known for its association with the b ...

and Acre. Olive oil

Olive oil is a liquid fat obtained from olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea''; family Oleaceae), a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin, produced by pressing whole olives and extracting the oil. It is commonly used in cooking: f ...

was the primary product of Nablus and aided other related industries such as soap-making and basket weaving. It was also the largest producer of cotton in the Levant, topping the production of northern cities such as Damascus. Jabal Nablus enjoyed a greater degree of autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy, from , ''autonomos'', from αὐτο- ''auto-'' "self" and νόμος ''nomos'', "law", hence when combined understood to mean "one who gives oneself one's ...

than other ''sanjaqs'' under Ottoman control, probably because the city was the capital of a hilly region, in which there were no "foreigners" who held any military or bureaucratic posts. Thus, Nablus remained outside the direct "supervision" of the Ottoman government, according to historian Beshara Doumani

Beshara Doumani ( ar, بشارة دوماني) is a Palestinian-American academic currently serving as the president of Birzeit University. Prior to that, he was the Mahmoud Darwish Professor of Palestinian Studies at Brown University. His resear ...

.Doumani, 1995, Chapter: "Introduction."

World War I and British Mandate

Between 19 September and 25 September 1918, in the last months of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War the Battle of Nablus took place, together with the

Between 19 September and 25 September 1918, in the last months of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of the First World War the Battle of Nablus took place, together with the Battle of Sharon

The Battle of Sharon fought between 19 and 25 September 1918, began the set piece Battle of Megiddo (1918), Battle of Megiddo half a day before the Battle of Nablus (1918), Battle of Nablus, in which large formations engaged and responded to mov ...

during the set piece Battle of Megiddo. Fighting took place in the Judean Hills

The Judaean Mountains, or Judaean Hills ( he, הרי יהודה, translit=Harei Yehuda) or the Hebron Mountains ( ar, تلال الخليل, translit=Tilal al-Khalīl, links=, lit=Hebron Mountains), is a mountain range in Palestine and Israel whe ...

where the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

's XX Corps and airforce attacked the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

's Yildirim Army Group

The Yildirim Army Group or Thunderbolt Army Group of the Ottoman Empire ( Turkish: ''Yıldırım Ordular Grubu'') or Army Group F (German: ''Heeresgruppe F'') was an Army Group of the Ottoman Army during World War I. While being an Ottoman unit, ...

's Seventh Army which held a defensive position in front of Nablus, and which the Eighth Army had attempted to retreat to, in vain.

The 1927 Jericho earthquake destroyed many of the Nablus' historic buildings, including the An-Nasr Mosque. Though they were subsequently rebuilt by Haj Amin al-Husayni

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab notable ...

's Supreme Muslim Council

The Supreme Muslim Council (SMC; ar, المجلس الإسلامي الاعلى) was the highest body in charge of Muslim community affairs in Mandatory Palestine under British control. It was established to create an advisory body composed of ...

in the mid-1930s, their previous "picturesque" character was lost. During British rule, Nablus emerged as a site of local resistance and the Old City quarter of Qaryun was demolished by the British during the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

.Doumani, 1995, Chapter: Family, Culture, and Trade. Jewish immigration did not significantly impact the demographic composition of Nablus, and it was slated for inclusion in the Arab state envisioned by the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

's 1947 partition plan for Palestine.

Jordanian period

During the1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

, Nablus came under Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

ian control. Thousands of Palestinian refugees fleeing from areas captured by Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

arrived in Nablus, settling in refugee camps in and around the city. Its population doubled, and the influx of refugees put a heavy strain on the city's resources. Three such camps still located within the city limits today are Ein Beit al-Ma', Balata and Askar. During the Jordanian period, the adjacent villages of Rafidia, Balata al-Balad

Balata village ( ar, بلاطة البلد, lit= Balata al-Balad) is a Palestinian people, Palestinian suburb of Nablus, in the northern West Bank, located east of the city center. Formerly its own village, it was annexed to the municipality of N ...

, al-Juneid and Askar were annexed to the Nablus municipality. Nablus was annexed by Jordan in 1950.

Israeli period

The 1967

The 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

ended in the Israeli occupation

Israeli-occupied territories are the lands that were captured and occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War of 1967. While the term is currently applied to the Palestinian territories and the Golan Heights, it has also been used to refer to a ...

of Nablus. Many Israeli settlement

Israeli settlements, or Israeli colonies, are civilian communities inhabited by Israeli citizens, overwhelmingly of Jewish ethnicity, built on lands occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers Israeli se ...

s were built around Nablus during the 1980s and early 1990s. The restrictions placed on Nablus during the First Intifada were met by a back-to-the-land movement to secure self-sufficiency, and had a notable outcome in boosting local agricultural production.

In 1976, Bassam Shakaa was elected mayor. On 2 June 1980, he survived an assassination attempt by the Jewish Underground

The Jewish Underground ( he, המחתרת היהודית ''HaMakhteret HaYehudit''), or in abbreviated form, simply ''makhteret'',David S. New''Holy War: The Rise of Militant Christian, Jewish and Islamic Fundamentalism,''McFarland, 2001, p. 143. w ...

, considered a terrorist group by Israel, which resulted in Shakaa losing both his legs. In the spring of 1982, the Israeli administration removed him from office and installed an army officer who ran the city for the following three and a half years.Middle East International No 270, 7 March 1986, Publishers Lord Mayhew, Dennis Walters

Sir Dennis Murray Walters (28 November 1928 – 1 October 2021) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for Westbury from 1964 to 1992.

Early life

The son of Douglas L. Walters and Clara Walters ...

. Daoud Kuttab

Daoud Kuttab ( ar, داود كتّاب), (born 1 April 1955) is a Palestinian-American journalist.

Journalism

In 1980, Kuttab began his career at '' Al-Fajr'', an English-language weekly newspaper. Over the next seven years, he was promoted to ...

p. 6

On 29 July 1985, the Israeli army imposed a 5-day curfew on the city. At the time this was the longest curfew ever imposed on a Palestinian community in the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

. It was lifted 2 hours each day to allow residents to find food. The curfew was in response to the murder of two teachers on 21 July near Jenin

Jenin (; ar, ') is a Palestinian city in the northern West Bank. It serves as the administrative center of the Jenin Governorate of the State of Palestine and is a major center for the surrounding towns. In 2007, Jenin had a population of app ...

and the killing of an Israeli para-military on 30 July. Najah University was closed for 2 months after posters with pictures of PLO leader were found.

In January 1986, the Israeli administration ended with the appointment of Zafer al-Masri

Zafer al-Masri ( ar, ظافر المصري; 1940 2 March 1986) was the Israel-appointed Mayor of Nablus, for a brief period of two months (January to March 1986). He had taken office in January 1986 as mayor in Nablus, the largest Arab town in ...

as mayor. A popular leader of the Nablus Chamber of Commerce al-Masri began a program of improvements in the town. Despite maintaining that he would have nothing to do with Israeli autonomy plans he was assassinated on 2 March 1986. The assassination was widely believed to be the work of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine ( ar, الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, translit=al-Jabhah al-Sha`biyyah li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn, PFLP) is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist and revolutionary soci ...

.

On 18 June 1989 Salah el Bah'sh, aged 17, was shot dead by an Israeli soldier

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

whilst walking through the Nablus Casbah

A kasbah (, also ; ar, قَـصَـبَـة, qaṣaba, lit=fortress, , Maghrebi Arabic: ), also spelled qasba, qasaba, or casbah, is a fortress

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territo ...

. Witnesses told B'Tselem

B'Tselem ( he, בצלם, , " in the image of od) is a Jerusalem-based non-profit organization whose stated goals are to document human rights violations in the Israeli-occupied Palestinian territories, combat any denial of the existence of su ...

, the Israeli Human Rights group, that he was shot in the chest at close range after not responding to a soldier shouting "Ta'amod" (Halt!). The army indicated that an investigation was being carried out. B'Tselem understood that the victim was killed by a rubber bullet

Rubber bullets (also called rubber baton rounds) are a type of baton round. Despite the name, rubber bullets typically have either a metal core with a rubber coating, or are a homogeneous admixture with rubber being a minority component. Altho ...

.

Palestinian control

Jurisdiction over the city was handed over to the

Jurisdiction over the city was handed over to the Palestinian National Authority

The Palestinian National Authority (PA or PNA; ar, السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية '), commonly known as the Palestinian Authority and officially the State of Palestine,

on December 12, 1995, as a result of the Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993;

Interim Agreement on the West Bank. Nablus is surrounded by Israeli settlements

Israeli settlements, or Israeli colonies, are civilian communities inhabited by Israeli citizens, overwhelmingly of Jewish ethnicity, built on lands occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers Israeli se ...

and was site of regular clashes with the Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

(IDF) during the First Intifada

The First Intifada, or First Palestinian Intifada (also known simply as the intifada or intifadah),The word ''intifada'' () is an Arabic word meaning "uprising". Its strict Arabic transliteration is '. was a sustained series of Palestinian ...

when the local prison was known for torture.

In the 1990s, Nablus was a hub of Palestinian nationalist

Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people that espouses self-determination and sovereignty over the region of Palestine.de Waart, 1994p. 223 Referencing Article 9 of ''The Palestinian National Charter of 1968' ...

activity in the West Bank and when the Second Intifada

The Second Intifada ( ar, الانتفاضة الثانية, ; he, האינתיפאדה השנייה, ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada ( ar, انتفاضة الأقصى, label=none, '), was a major Palestinian uprising against Israel. ...

began, arsonists of Jewish shrines in Nablus were applauded. After the controversy over the Muhammad cartoons in ''Jyllands-Posten'', originally published in Denmark in late September 2006, militias kidnapped two foreigners and threatened to kidnap more as a protest. In 2008, Noa Meir, an Israeli military spokeswoman, said Nablus remains "capital of terror" of the West Bank.

From the start of the Second Intifada

The Second Intifada ( ar, الانتفاضة الثانية, ; he, האינתיפאדה השנייה, ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada ( ar, انتفاضة الأقصى, label=none, '), was a major Palestinian uprising against Israel. ...

, which began in September 2000, Nablus became a flash-point of clashes between the IDF and Palestinians. The city has a tradition of political activism, as evinced by its nickname, ''jabal al-nar'' (Fire Mountain)Glenn E. Robinson''Building a Palestinian State: The Incomplete Revolution,''

Indiana University Press, 1997 p.57. and, located between two mountains, was closed off at both ends of the valley by Israeli checkpoints. For several years, movements in and out of the city were highly restricted. Nablus produced more

suicide bombers

A suicide attack is any violent attack, usually entailing the attacker detonating an explosive, where the attacker has accepted their own death as a direct result of the attacking method used. Suicide attacks have occurred throughout histor ...

than any other city during the Second Intifada. The city and the refugee camps

A refugee camp is a temporary settlement built to receive refugees and people in refugee-like situations. Refugee camps usually accommodate displaced people who have fled their home country, but camps are also made for internally displaced peo ...

of Balata and Askar constituted the center of "knowhow" for the production and operation of the rockets in the West Bank.

According to the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is a United Nations (UN) body established in December 1991 by the General Assembly to strengthen the international response to complex emergencies and natural disaster ...

, 522 residents of Nablus and surrounding refugee camps, including civilians, were killed and 3,104 injured during IDF military operations from 2000 to 2005. In April 2002, following the Passover massacre

The Passover massacre was a suicide bombing carried out by Hamas at the Park Hotel in Netanya, Israel on 27 March 2002, during a Passover seder. Thirty civilians were killed in the attack and 140 were injured. It was the deadliest attack a ...

—an attack by Palestinian militants that killed 30 Israeli civilians attending a seder

The Passover Seder (; he, סדר פסח , 'Passover order/arrangement'; yi, סדר ) is a ritual feast at the beginning of the Jewish holiday of Passover. It is conducted throughout the world on the eve of the 15th day of san_in_the_Hebrew_c_...

_dinner_at_the_Park_Hotel_in_Netanya—Israel_launched_Operation_Defensive_Shield,_a_major_Battle_of_Nablus.html" "title="Operation_Defensive_Shield.html" ;"title="san in the Hebrew c ...targeting in particular Nablus and Jenin. At least 80 Palestinians were killed in Nablus during the operation and several houses were destroyed or severely damaged. The operation also resulted in severe damage to the historic core of the city, with 64 heritage buildings being heavily damaged or destroyed. IDF forces reentered Nablus during Operation Determined Path in June 2002, remaining inside the city until the end of September. Over those three months, there had been more than 70 days of full 24-hour curfews. According to Gush Shalom, IDF bulldozers damaged the al-Khadra Mosque, the Great Mosque, the al-Satoon Mosque and the

Greek Orthodox Church

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

in 2002. Some 60 houses were destroyed, and parts of the stone-paving in the old city were damaged. The al-Shifa ''hammam

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited f ...

'' was hit by three rockets from Apache helicopter

The Boeing AH-64 Apache () is an American twin-turboshaft attack helicopter with a tailwheel-type landing gear arrangement and a tandem cockpit for a crew of two. It features a nose-mounted sensor suite for target acquisition and night visi ...

s. The eastern entrance of the Khan al-Wikala (old market) and three soap factories were destroyed in F-16

The General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon is a single-engine Multirole combat aircraft, multirole fighter aircraft originally developed by General Dynamics for the United States Air Force (USAF). Designed as an air superiority day fighter, it ...

bombings. The cost of the damage was estimated at $80 million US.

In August 2016, the Old City of Nablus became a site of fierce clashes between a militant group vs Palestinian police. On August 18, two Palestinian Police servicemen were killed in the city. Shortly after the raid of police on the suspected areas in the Old City deteriorated into a gun battle, in which three armed militia men were killed, including one killed by beating following his arrest. The person beaten to death was the suspected “mastermind” behind the August 18 shooting - Ahmed Izz Halaweh, a senior member of the armed wing of the Fatah movement the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades. His death was branded by the UN and Palestinian factions as a part of “extrajudicial executions.” A widespread manhunt for multiple gunmen was initiated by the police as a result, concluding with the arrest of one suspect Salah al-Kurdi on August 25.

Geography

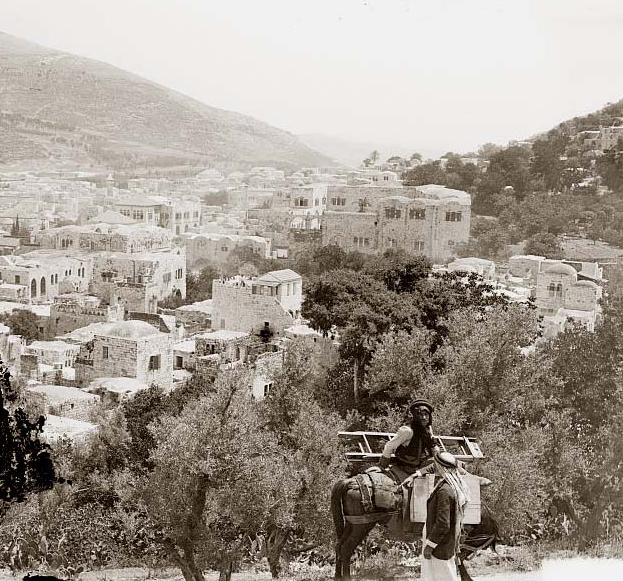

Nablus lies in a strategic position at a junction between two ancient commercial roads; one linking the Sharon coastal plain to the

Nablus lies in a strategic position at a junction between two ancient commercial roads; one linking the Sharon coastal plain to the Jordan valley

The Jordan Valley ( ar, غور الأردن, ''Ghor al-Urdun''; he, עֵמֶק הַיַרְדֵּן, ''Emek HaYarden'') forms part of the larger Jordan Rift Valley. Unlike most other river valleys, the term "Jordan Valley" often applies just to ...

, the other linking Nablus to the Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

in the north, and the biblical Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Hebrew language#Modern Hebrew, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian vocalization, Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous L ...

to the south through the mountains. The city stands at an elevation of around above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance (height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as ''orthometric heights''.

The comb ...

, in a narrow valley running roughly east–west between two mountains: Mount Ebal

Mount Ebal ( he, ''Har ʿĒyḇāl''; ar, جبل عيبال ''Jabal ‘Aybāl'') is one of the two mountains in the immediate vicinity of the city of Nablus in the West Bank (biblical ''Shechem''), and forms the northern side of the valley in ...

, the northern mountain, is the taller peak at , while Mount Gerizim

Mount Gerizim (; Samaritan Hebrew: ''ʾĀ̊rgā̊rīzēm''; Hebrew: ''Har Gərīzīm''; ar, جَبَل جَرِزِيم ''Jabal Jarizīm'' or جَبَلُ ٱلطُّورِ ''Jabal at-Ṭūr'') is one of two mountains in the immediate vicinit ...

, the southern mountain, is high.

Nablus is located east of Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

, Israel