Nabataeans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (;

Petra was rapidly built in the 1st century BC, and developed a population estimated at 20,000.

The Nabataeans were allies of the first Hasmoneans in their struggles against the Seleucid monarchs. They then became rivals of the Judaean dynasty, and a chief element in the disorders that invited

Petra was rapidly built in the 1st century BC, and developed a population estimated at 20,000.

The Nabataeans were allies of the first Hasmoneans in their struggles against the Seleucid monarchs. They then became rivals of the Judaean dynasty, and a chief element in the disorders that invited

The Nabateans appear in the

The Nabateans appear in the

Many examples of graffiti and inscriptions—largely of names and greetings—document the area of Nabataean culture, which extended as far north as the north end of the

Many examples of graffiti and inscriptions—largely of names and greetings—document the area of Nabataean culture, which extended as far north as the north end of the

The Nabataeans spoke an Arabic dialect but, for their inscriptions, used a form of

The Nabataeans spoke an Arabic dialect but, for their inscriptions, used a form of

Hecht Museum - Catalogues , The Nabateans in the Negev

Hecht Museum - Exhibitions , The Nabateans in the Negev

��links on Petra and the Nabataeans

NABATÆANS in the ''Jewish Encyclopedia''

Cincinnati Art Museum

��the only collection of ancient Nabataean art outside of Jordan

��Ancient Desert Agriculture Systems Revived (ADASR)

Petra: Lost City of Stone Exhibition

��Canadian Museum of Civilization

"Solving the Enigma of Petra and the Nabataeans"

''Biblical Archaeology Review''

��Petra Crown {{Authority control Ancient Arabic peoples Tribes of Arabia Arab groups Arabs in the Roman Empire History of Saudi Arabia History of Palestine (region) Ancient history of Jordan Ancient Syria Ancient Israel and Judah Gilead

Nabataean Aramaic

Nabataean Aramaic is the Aramaic variety used in inscriptions by the Nabataeans of the East Bank of the Jordan River, the Negev, and the Sinai Peninsula. Compared to other varieties of Aramaic, it is notable for the occurrence of a number of loa ...

: , , vocalized as ; Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

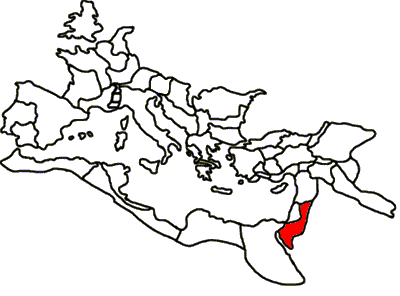

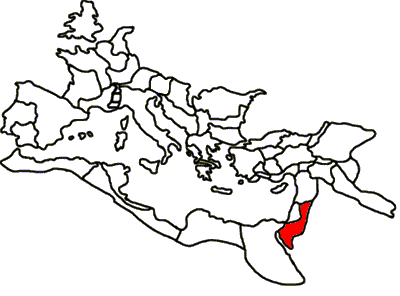

: , , singular , ; compare grc, Ναβαταῖος, translit=Nabataîos; la, Nabataeus) were an ancient Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

people who inhabited northern Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

and the southern Levant

The Southern Levant is a geographical region encompassing the southern half of the Levant. It corresponds approximately to modern-day Israel, Palestine, and Jordan; some definitions also include southern Lebanon, southern Syria and/or the Sinai ...

. Their settlements—most prominently the assumed capital city of Raqmu (present-day Petra, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Ri ...

)—gave the name ''Nabatene'' ( grc, Ναβατηνή, translit=Nabatēnḗ) to the Arabian borderland that stretched from the Euphrates to the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; ...

.

The Nabateans emerged as a distinct civilization and political entity between the 4th and 2nd centuries BCE,Taylor, Jane (2001). ''Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans''. London: I.B.Tauris

I.B. Tauris is an educational publishing house and imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing. It was an independent publishing house with offices in London and New York City until its purchase in May 2018 by Bloomsbury Publishing.

It specialises in non- ...

. pp. 14, 17, 30, 31. . Retrieved 8 July 2016. with their kingdom centered around a loosely controlled trading network that brought considerable wealth and influence across the ancient world.

Described as fiercely independent by contemporary Greco-Roman accounts, the Nabataeans were annexed into the Roman Empire by Emperor Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presid ...

in 106 CE. Nabataeans' individual culture, easily identified by their characteristic finely potted painted ceramics, was adopted into the larger Greco-Roman culture. They later converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

during the Later Roman Era.

Name

The original form of the name of the Nabataeans was , which is recorded in Babylonian Akkadian as , and was the "broken" plural form of the Arabic term , meaning "distinguished man." This name underwent two principal evolutions, with the omission of the glottal stop producing the form , and the replacement of by avoiced palatal approximant

The voiced palatal approximant, or yod, is a type of consonant used in many spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is . The equivalent X-SAMPA symbol is j, and in the Americanist phonetic no ...

producing the form .

The name of the Nabataeans is recorded in Akkadian sources as , , , , , , and .

In Latin sources, the name of the Nabataeans was recorded as .

Identity

The Nabataeans were anArab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

tribe who had come under significant Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

n-Aramaean

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

influence.

Some scholars have identified the people named as in Neo-Assyrian Akkadian records and in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

based on the similarity of their names with , which is the Arabic name of the Nabataeans. The scholar Israel Ephʿal has rejected this identification because of the use of a in the Akkadian and Hebrew forms while the Arabic form uses a , and because the former forms possess a which is absent from the Arabic form, as attested by to the discovery of a ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Taymanitic

Taymanitic was the language and script of the oasis of Taymāʾ in northwestern Arabia, dated to the second half of the 6th century BCE.

Classification

Taymanitic does not participate in the key innovations of Proto-Arabic, precluding it from ...

inscription in the Jabal Ġunaym which records the name of the as . The scholar Edward Lipiński has however refuted this rejection by demonstrating that these various forms of the name were derived from an original form , from which the glottal stop was replaced by a palatal approximant, hence producing the Akkadian and Hebrew forms and , while omission of the glottal stop produced the Arabic form .

History

Neo-Assyrian period

The Nabataeans were first mentioned, under the name of , by theNeo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

king Tukultī-apil-Ešarra III, who mistakenly referred to them as an Aramaean

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

tribe, although their presence in his list between two other North Arabian tribes, the Ḫagaranu and the Liʾtau, shows that they were an Arabic population.

During the 8th to 7th centuries BCE, the Nabataeans were living in the part of the Syrian Desert

The Syrian Desert ( ar, بادية الشام ''Bādiyat Ash-Shām''), also known as the North Arabian Desert, the Jordanian steppe, or the Badiya, is a region of desert, semi-desert and steppe covering of the Middle East, including parts of so ...

immediately adjacent to the western border of Babylonia, and at the time of the Babylonian king Marduk-apla-iddina II

Marduk-apla-iddina II (Akkadian: ; in the Bible Merodach-Baladan, also called Marduk-Baladan, Baladan and Berodach-Baladan, lit. ''Marduk has given me an heir'') was a Chaldean leader from the Bit-Yakin tribe, originally established in the territo ...

, some of them were present in Babylonia itself, with his inscriptions recording the existence of a city of Nabatu settled by this tribe. Some of these Babylonian Nabataeans were placed by the Neo-Assyrian king Šarru-kīn II into the service of the governor of Ašipā.

The Nabataeans were mentioned again by the Neo-Assyrian king Sîn-ahhī-erība, although his inscriptions do not contain any further information about them.

During the 660s and 650s BCE, the Nabataeans were ruled by a chief bearing the Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

n Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

name of Nadnu, reflecting the significant Babylonian cultural influence under which the tribe was. During this period, the Nabataeans were vassals of the Neo-Assyrian king Aššur-bāni-apli

Ashurbanipal (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Ashur is the creator of the heir") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Inheriting the throne a ...

, and their neighbours in the Babylonian border region were the Arab tribe of Masʾaya, who themselves lived in the western border regions of Bīt-Amukkani.

At one point during the early years of Aššur-bāni-apli's reign, Yawṯiʿ ben Ḥazaʾil, the king of another the Arab tribe of the Qedarites, had rebelled against the Neo-Assyrian Empire, prompting Aššur-bāni-apli to conduct a campaign against the Qedarites. After Aššur-bāni-apli had defeated the Qedarite king Yawṯiʿ ben Ḥazaʾil, the latter fled into the territory of the Nabataeans, who were then living beyond the area of control and influence of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and sought the sanctuary of Nadnu. Due to increased Assyrian influence in the desert as a result of his campaign, however, Nadnu refused to grant refuge to Yauṯaʿ, and he himself instead swore allegiance Aššur-bāni-apli and pledged to pay annual tribute to the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

In 652 BCE, the Babylonian king Šamaš-šuma-ukin rebelled against his younger brother, the Neo-Assyrian king Aššur-bāni-apli. Shortly after, in 651 BCE, Nadnu also rebelled against Aššur-bāni-apli and made contact with Šamaš-šuma-ukin, who offered captives from Sippar

Sippar (Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, s ...

to his envoys at Kutha

Kutha, Cuthah, Cuth or Cutha ( ar, كُوثَا, Sumerian: Gudua), modern Tell Ibrahim ( ar, تَلّ إِبْرَاهِيم), formerly known as Kutha Rabba ( ar, كُوثَىٰ رَبَّا), is an archaeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. ...

. Although the Qedarites had supported Šamaš-šuma-ukin in the war which opposed Šamaš-šuma-ukin to Aššur-bāni-apli as result of this rebellion, there is no information available regarding the role of Nadnu's involvement within this conflict.

According to letters sent to Aššur-bāni-apli by the Assyrian general Nabȗ-šum-lišir who served in the region of the south-west border of Babylonia at the time of Shamash-shum-ukin's rebellion, a caravan which had left the territory of the Nabataeans was attacked by one Ayakabaru son of ʿAmyaṯaʿ of the Masʾaya tribe, with only one of its members managing to escape and reaching a fortified Assyrian outpost.

Following the complete suppression of the Babylonian revolt in 648 BCE, while the Assyrians were busy until 646 BCE conducting operations against the Elamite kings who had supported Shamash-shum-ukin, the southern Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

n cities and the kingdom of Judah seized the opportunity and rebelled against Assyrian authority. By this time, most of the Nabataeans had moved into the steppe regions of the Syrian Desert, more specifically in the north-east of the Palmyrena region, where Nadnu's Nabataeans, along with the Qedarites led by their chiefs Abyaṯiʿ, Ayammu, and Yuhayṯiʿ ben Birdāda, took advantage of the situation to conduct raids against the western borderlands of the Neo-Assyrian Empire ranging from the Jabal al-Bišrī to the environs of the city of Damascus, and were able to intensify their pressure on the areas of the Middle Euphrates and of Palmyrena.

Once the Assyrian war in Elam was complete, in 645 BCE Aššur-bāni-apli attacked the Qedarites and the Nabataeans during a three-months campaign with the goal of subjugating the Arabs permanently. The Assyrian armies first attacked from Ḫadattâ, passing through the desert between Laribda, Ḫuraruna and Yarki before reaching Azalla after defeating the joint forces of the Qedarites, Nabataeans, and another tribe, the Isammeʾ, in the region between Yarki and Azalla; the Assyrians then proceeded from Azalla to Quraṣiti, where they attacked Yuhayṯiʿ ben Birdāda, who fled, captured his mother, sister and family, many prisoners, as well as donkeys, camels, sheep, and goats, and seized the tribe's idols, and dispatched them all through the Damascus road; finally, the Assyrians marched out from Damascus till Ḫulḫuliti, and from there carried out their final attack on the Arabs near the Mount Ḫukkurina, where they captured Abyaṯiʿ and Ayammu. Due to the Assyrian campaign, the Qedarites rebelled against Yuhayṯiʿ and handed him over to the Assyrians.

Some time after the campaign against the Qedarites was complete, during the later 640s BCE the Assyrians conducted a campaign against the Nabataeans, who were then living around the Wādī Sirḥān or to its immediate south. During this campaign, the Assyrian army destroyed the settlements of the Nabataeans and captured Nadnu, his wife, his children, and large amounts of booty. Nadnu's son, Nuḫuru, was able to escape before willingly surrendering to Aššur-bāni-apli, who appointed him as the new king of the Nabataeans.

Neo-Babylonian period

The Nabataeans appear to not have pressed against the Transjordanian region during the period which oversaw the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and its replacement by theNeo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

, and the Canaanite kingdoms of Palestine were strong enough to resist the Arabs once the region had come under Babylonian hegemony.

In the 6th century BCE, the Nabataeans were living in the northwestern part of the Arabian peninsula to the south of the Wādī Sirḥān, possibly in the region of Taymāʾ and al-Jawf, where they neighboured the Canaanite state of Edom

Edom (; Edomite: ; he, אֱדוֹם , lit.: "red"; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom in Transjordan, located between Moab to the northeast, the Arabah to the west, and the Arabian Desert to the south and eas ...

, and where, according to a 6th century BCE inscription from the Jabal Ġunaym, they had engaged in war against the people of the oasis of Taymāʾ.

After the Neo-Babylonian king Nabû-kudurri-uṣur II annexed the Canaanite kingdoms of Judah in 587 BC and of Ammon

Ammon ( Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; he, עַמּוֹן ''ʻAmmōn''; ar, عمّون, ʻAmmūn) was an ancient Semitic-speaking nation occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Arnon and Jabbok, in ...

and Moab in 582 BC, and the later Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus

Nabonidus (Babylonian cuneiform: ''Nabû-naʾid'', meaning "May Nabu be exalted" or "Nabu is praised") was the last king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from 556 BC to the fall of Babylon to the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in 539 ...

campaigned through Edom in 553 BC, the resulting power vacuum in Transjordan allowed the Arabs of the Syrian desert, including the Qedarites and the Nabataeans, to expand into these former states' settled territories close to the desert, including across southern Transjordan and Palestine until the Judaean hills, where they remained throughout the existence of the Neo-Babylonian Empire and cohabited with the sedentary Ammonite, Moabite, and Edomite populations, with whom these Arab incomers mingled over several generations.

Achaemenid period

When Kūruš II conquered the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 539 BC, the Arab populations of the Syrian desert and of North Arabia, including the Qedarites, as well as the desert routes going into Mesopotamia from these regions, became part of his PersianAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

. Thanks to the Achaemenid Empire's multinational structure and its policy of tolerance and the end of any independent polities within Transjordan and Palestine, these Arab groups became integrated into the Persian Empire's economic, administrative, and military systems, with this process also being driven by the development of trade in Arabia as well as the military activities of the Achaemenid kings due to which warriors from all the populations ruled by their empire, including those from the Arab peoples, required their enrollment into the Achaemenid army.

Thus, in 480 BC, camel-riding Arab units participated in the Achaemenid king Xšayār̥šā I's invasion of Greece, and Arab units of the Achaemenid army also participated in the empire's overseas and coastal military activities in 410 and 386 BC.

Achaemenid rule over the Transjordanian Arabs lasted until Egypt under Amyrtaeus

Amyrtaeus ( , a Hellenization of the original Egyptian name Amenirdisu) of Sais, is the only pharaoh of the Twenty-eighth Dynasty of EgyptCimmino 2003, p. 385. and is thought to be related to the royal family of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (664� ...

rebelled against Persian rule and embarked on anti-Persian activities in Palestine, Phoenicia and Cyprus at the same time that the Persian Empire was itself facing a number of internal crisis which greatly weakened it. In this situation, Persian rule broke down in Transjordan, which became independent.

Hellenistic period

The Nabataeans remained independent after the Macedonian conquest of the Achaemenid Empire byAlexander III of Macedon

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

and during the time of the Hellenistic states established by the Diadochi

The Diadochi (; singular: Diadochus; from grc-gre, Διάδοχοι, Diádochoi, Successors, ) were the rival generals, families, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death in 323 BC. The Wa ...

.

The first mention of the Nabataeans during the Hellenistic period dates from 312/311 BCE, when they were attacked at Sela Sela may refer to:

People Surname

* Avraham Sela (born 1950), Israeli political scientist

* Dudi Sela (born 1985), Israeli tennis player

* Jonas Sela (born 1984), German footballer

* Jonathan Sela (born 1978), French-born Israeli cinematographe ...

or perhaps at Petra

Petra ( ar, ٱلْبَتْرَاء, Al-Batrāʾ; grc, Πέτρα, "Rock", Nabataean: ), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu or Raqēmō, is an historic and archaeological city in southern Jordan. It is adjacent to the mountain of Ja ...

without success by Antigonus I

Antigonus I Monophthalmus ( grc-gre, Ἀντίγονος Μονόφθαλμος , 'the One-Eyed'; 382 – 301 BC), son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian Greek nobleman, general, satrap, and king. During the first half of his life he serv ...

's officer Athenaeus in the course of the Third War of the Diadochi; at that time Hieronymus of Cardia Hieronymus of Cardia ( el, Ἱερώνυμος ὁ Καρδιανός, 354?–250 BC) was a Greek general and historian from Cardia in Thrace, and a contemporary of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC).

After the death of Alexander he followed the fo ...

, a Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

officer, mentioned the Nabataeans in a battle report. About 50 BCE, the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

historian Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

cited Hieronymus in his report, and added the following: "Just as the Seleucids had tried to subdue them, so the Romans made several attempts to get their hands on that lucrative trade." They wrote a letter to Antigonus in Syriac Syriac may refer to:

* Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages ...

letters, and Aramaic continued as the language of their coins and inscriptions when the tribe grew into a kingdom and profited by the decay of the Seleucids to extend its borders northward over the more fertile country east of the Jordan river

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

. They occupied Hauran

The Hauran ( ar, حَوْرَان, ''Ḥawrān''; also spelled ''Hawran'' or ''Houran'') is a region that spans parts of southern Syria and northern Jordan. It is bound in the north by the Ghouta oasis, eastwards by the al-Safa field, to the ...

, and in about 85 BCE their king Aretas III

Aretas III (; Nabataean Aramaic:

''Ḥārīṯat''; Ancient Greek: ) was king of the Nabataean kingdom from 87 to 62 BCE. Aretas ascended to the throne upon the death of his brother, Obodas I, in 87 BCE. During his reign, he extended his kin ...

became lord of Damascus and Coele-Syria

Coele-Syria (, also spelt Coele Syria, Coelesyria, Celesyria) alternatively Coelo-Syria or Coelosyria (; grc-gre, Κοίλη Συρία, ''Koílē Syría'', 'Hollow Syria'; lat, Cœlē Syria or ), was a region of Syria (region), Syria in cl ...

.

Nabataean Kingdom

Petra was rapidly built in the 1st century BC, and developed a population estimated at 20,000.

The Nabataeans were allies of the first Hasmoneans in their struggles against the Seleucid monarchs. They then became rivals of the Judaean dynasty, and a chief element in the disorders that invited

Petra was rapidly built in the 1st century BC, and developed a population estimated at 20,000.

The Nabataeans were allies of the first Hasmoneans in their struggles against the Seleucid monarchs. They then became rivals of the Judaean dynasty, and a chief element in the disorders that invited Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

's intervention in Judea

Judea or Judaea ( or ; from he, יהודה, Standard ''Yəhūda'', Tiberian ''Yehūḏā''; el, Ἰουδαία, ; la, Iūdaea) is an ancient, historic, Biblical Hebrew, contemporaneous Latin, and the modern-day name of the mountainous south ...

. According to popular historian

Popular history is a broad genre of historiography that takes a popular approach, aims at a wide readership, and usually emphasizes narrative, personality and vivid detail over scholarly analysis. The term is used in contradistinction to professio ...

Paul Johnson, many Nabataeans were forcefully converted to Judaism by Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus

Alexander Jannaeus ( grc-gre, Ἀλέξανδρος Ἰανναῖος ; he, ''Yannaʾy''; born Jonathan ) was the second king of the Hasmonean dynasty, who ruled over an expanding kingdom of Judea from 103 to 76 BCE. A son of John Hyrcanus, ...

. It was this king who, after putting down a local rebellion, invaded and occupied the Nabataean towns of Moab and Gilead

Gilead or Gilad (; he, גִּלְעָד ''Gīləʿāḏ'', ar, جلعاد, Ǧalʻād, Jalaad) is the ancient, historic, biblical name of the mountainous northern part of the region of Transjordan.''Easton's Bible Dictionary'Galeed''/ref> ...

and imposed a tribute of an unknown amount. Obodas I

Obodas I ( Nabataean Aramaic: ''ʿŌbōdaṯ''; grc, Ὀβόδας) was king of the Nabataeans from 96 BC to 85 BC. After his death, Obodas was worshiped as a deity.

Life

Obodas was the successor of Aretas II, from whom he inherited the war w ...

knew that Alexander would attack, so was able to ambush Alexander's forces near Gaulane destroying the Judean army (90 BC).

The Roman military was not very successful in their campaigns against the Nabataeans. In 62 BCE, Marcus Aemilius Scaurus accepted a bribe of 300 talents to lift the siege of Petra, partly because of the difficult terrain and the fact that he had run out of supplies. Hyrcanus II

John Hyrcanus II (, ''Yohanan Hurqanos'') (died 30 BCE), a member of the Hasmonean dynasty, was for a long time the Jewish High Priest in the 1st century BCE. He was also briefly King of Judea 67–66 BCE and then the ethnarch (ruler) of ...

, who was a friend of Aretas, was despatched by Scaurus to the King to buy peace. In so obtaining peace, King Aretas retained all his possessions, including Damascus, and became a Roman vassal.

In 32 BCE, during King Malichus II

Malichus II (Nabataean Aramaic: ''Malīḵū'' or ''Malīḵūʾ'') was ruler of Nabatea from 40 to 70 AD.

Malichus' reign is sometimes perceived as a period of declining Nabataean power, but this view depends in part on Nabataea having contro ...

's reign, Herod the Great

Herod I (; ; grc-gre, ; c. 72 – 4 or 1 BCE), also known as Herod the Great, was a History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Roman Jewish client state, client king of Judea, referred to as the Herodian Kingdom of Judea, Herodian kingdom. He ...

, with the support of Cleopatra

Cleopatra VII Philopator ( grc-gre, Κλεοπάτρα Φιλοπάτωρ}, "Cleopatra the father-beloved"; 69 BC10 August 30 BC) was Queen of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, Egypt from 51 to 30 BC, and its last active ruler. ...

, started a war against Nabataea. The war began with Herod plundering Nabataea with a large cavalry force, and occupying Dium

Dion ( el, Δίον; grc, Δῖον; la, Dium) is a village and municipal unit in the municipality of Dion-Olympos in the Pieria regional unit, Greece. It is located at the foot of Mount Olympus at a distance of 17 km from the capital ...

. After this defeat, the Nabataean forces amassed near Canatha

Qanawat ( ar, قَنَوَات, Qanawāt) is a village in Syria, located 7 km north-east of al-Suwayda. It stands at an elevation of about 1,200 m, near a river and surrounded by woods. Its inhabitants are entirely from the Druze com ...

in Syria, but were attacked and routed. Cleopatra's general, Athenion, sent Canathans to the aid of the Nabataeans, and this force crushed Herod's army, which then fled to Ormiza. One year later, Herod's army overran Nabataea.

After an earthquake in Judaea, the Nabateans rebelled and invaded Judea, but Herod at once crossed the Jordan river to Philadelphia (modern Amman) and both sides set up camp. The Nabataeans under Elthemus refused to give battle, so Herod forced the issue when he attacked their camp. A confused mass of Nabataeans gave battle but were defeated. Once they had retreated to their defences, Herod laid siege to the camp and over time some of the defenders surrendered. The remaining Nabataean forces offered 500 talents for peace, but this was rejected. Lacking water, the Nabataeans were forced out of their camp for battle, but were defeated in this last battle.

Roman period

An ally of the Roman Empire, the Nabataean kingdom flourished throughout the 1st century. Its power extended far into Arabia along the Red Sea to Yemen, and Petra was a cosmopolitan marketplace, though its commerce was diminished by the rise of the Eastern trade-route from Myos Hormos toCoptos

Qift ( arz, قفط ; cop, Ⲕⲉϥⲧ, link=no ''Keft'' or ''Kebto''; Egyptian Gebtu; grc, Κόπτος, link=no ''Coptos'' / ''Koptos''; Roman Justinianopolis) is a small town in the Qena Governorate of Egypt about north of Luxor, situated u ...

on the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. Under the ''Pax Romana

The Pax Romana (Latin for 'Roman peace') is a roughly 200-year-long timespan of Roman history which is identified as a period and as a golden age of increased as well as sustained Roman imperialism, relative peace and order, prosperous stability ...

'', the Nabataeans lost their warlike and nomadic habits and became a sober, acquisitive, orderly people, wholly intent on trade and agriculture. The kingdom was a bulwark between Rome and the wild hordes of the desert except in the time of Trajan, who reduced Petra and converted the Nabataean client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

into the Roman province of Arabia Petraea

Arabia Petraea or Petrea, also known as Rome's Arabian Province ( la, Provincia Arabia; ar, العربية البترائية; grc, Ἐπαρχία Πετραίας Ἀραβίας) or simply Arabia, was a frontier province of the Roman Empi ...

. By the 3rd century, the Nabataeans had stopped writing in Aramaic and begun writing in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

instead, and by the 5th century they had converted to Christianity. The new Arab invaders, who soon pressed forward into their seats, found the remnants of the Nabataeans transformed into peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

s. Their lands were divided between the new Qahtanite

The terms Qahtanite and Qahtani ( ar, قَحْطَانِي; transliterated: Qaḥṭānī) refer to Arabs who originate from South Arabia. The term "Qahtan" is mentioned in multiple ancient Arabian inscriptions found in Yemen. Arab traditions ...

Arab tribal kingdoms of the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

vassals, the Ghassanid

The Ghassanids ( ar, الغساسنة, translit=al-Ġasāsina, also Banu Ghassān (, romanized as: ), also called the Jafnids, were an Arab tribe which founded a kingdom. They emigrated from southern Arabia in the early 3rd century to the Levan ...

Arabs, and the Himyarite

The Himyarite Kingdom ( ar, مملكة حِمْيَر, Mamlakat Ḥimyar, he, ממלכת חִמְיָר), or Himyar ( ar, حِمْيَر, ''Ḥimyar'', / 𐩹𐩧𐩺𐩵𐩬) (fl. 110 BCE–520s CE), historically referred to as the Homerit ...

vassals, the Kingdom of Kinda

The Kingdom of Kinda ( ar, كِنْدَة الملوك, Kindat al-Mulūk, Royal Kinda) also called the Kindite kingdom, refers to the rule of the Bedouin, nomadic Arab tribes of the Ma'add confederation in north and central Arabia by the Banu Aki ...

in North Arabia. The city of Petra was brought to the attention of Westerners by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt

Johann Ludwig (also known as John Lewis, Jean Louis) Burckhardt (24 November 1784 – 15 October 1817) was a Swiss traveller, geographer and Orientalist. Burckhardt assumed the alias ''Sheikh Ibrahim Ibn Abdallah'' during his travels in Arabia ...

in 1812.

Legacy

The Nabataeans are mentioned under the name of in theHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

, where they are often grouped with . The Roman author ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

also listed the Nabataeans under the name of along with the (Qedarites) in his .

Biblical

The Nabateans appear in the

The Nabateans appear in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

as a tribe descended from Nəḇāyōṯ, the first son of Yīšmāʿēʾl, himself the son of ʾAḇrāhām and Hāgār, In the Bible, Yīšmāʿēʾl's eldest son Nəḇāyōṯ is given prominence due to the rule of primogeniture, with Yīšmāʿēʾl's second son Qēḏār also being given some level of prominence due to being the second-born son, making him the closest of Yīšmāʿēʾl's sons to the one standing for primogeniture.

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

Islamic

The tradition of claiming descent from Ibrāhīm's son ʾIsmāʿīl, called "genealogical Ishmaelism," was already present among some pre-Islamic Arabs, and, in Islamic sources, ʾIsmāʿīl is the eponymous ancestor of some of the Arab peoples of north-west Arabia, with prominence being accorded to his two eldest sons, Nābit () or Nabīt () (Biblical Nəḇāyōṯ) and Qaydar () or Qaydār ((; Biblical Qēḏār), who lived in eastern Transjordan, Sinai and the Ḥijāz, and whose descendant tribes were the most prominent ones among the twelve tribes of theIshmaelites

The Ishmaelites ( he, ''Yīšməʿēʾlīm,'' ar, بَنِي إِسْمَاعِيل ''Bani Isma'il''; "sons of Ishmael") were a collection of various Arabian tribes, confederations and small kingdoms described in Islamic tradition as being des ...

.

According to Islamic tradition, the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

is believed to have been a descendant of ʾIsmāʿīl through either Nābit or Qaydār depending on the scholar.

According to the scholar Irfan Shahîd

Irfan Arif Shahîd ( ar, عرفان عارف شهيد ; Nazareth, Mandatory Palestine, January 15, 1926 – Washington, D.C., November 9, 2016), born as Erfan Arif Qa'war (), was a scholar in the field of Oriental studies. He was from 1982 unti ...

, genealogical Ishmaelism was academically viewed with suspicion due to confusion in the Islamic period which led to ʾIsmāʿīl being considered as the ancestor of all Arabian tribes. According to Shahîd, genealogical Ishamelism in its original variant is instead more limited and applicable to only some Arab tribes.

Culture

Many examples of graffiti and inscriptions—largely of names and greetings—document the area of Nabataean culture, which extended as far north as the north end of the

Many examples of graffiti and inscriptions—largely of names and greetings—document the area of Nabataean culture, which extended as far north as the north end of the Dead Sea

The Dead Sea ( he, יַם הַמֶּלַח, ''Yam hamMelaḥ''; ar, اَلْبَحْرُ الْمَيْتُ, ''Āl-Baḥrū l-Maytū''), also known by other names, is a salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east and Israel and the West Bank ...

, and testify to widespread literacy; but except for a few letters no Nabataean literature has survived, nor was any noted in antiquity. Onomastic

Onomastics (or, in older texts, onomatology) is the study of the etymology, history, and use of proper names. An ''orthonym'' is the proper name of the object in question, the object of onomastic study.

Onomastics can be helpful in data mining, w ...

analysis has suggested that Nabataean culture may have had multiple influences. Classical references to the Nabataeans begin with Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

; they suggest that the Nabataeans' trade routes and the origins of their goods were regarded as trade secrets, and disguised in tales that should have strained outsiders' credulity. Diodorus Siculus

Diodorus Siculus, or Diodorus of Sicily ( grc-gre, Διόδωρος ; 1st century BC), was an ancient Greek historian. He is known for writing the monumental universal history '' Bibliotheca historica'', in forty books, fifteen of which ...

(book II) described them as a strong tribe of some 10,000 warriors, preeminent among the nomads of Arabia, eschewing agriculture, fixed houses, and the use of wine, but adding to pastoral pursuits a profitable trade with the seaports in frankincense, myrrh

Myrrh (; from Semitic, but see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus '' Commiphora''. Myrrh resin has been used throughout history as a perfume, incense and medicine. Myrrh mix ...

and spices from Arabia Felix

Arabia Felix (literally: Fertile/Happy Arabia; also Ancient Greek: Εὐδαίμων Ἀραβία, ''Eudaemon Arabia'') was the Latin name previously used by geographers to describe South Arabia, or what is now Yemen.

Etymology

The term Arabia ...

(today's Yemen), as well as a trade with Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

in bitumen

Asphalt, also known as bitumen (, ), is a sticky, black, highly viscous liquid or semi-solid form of petroleum. It may be found in natural deposits or may be a refined product, and is classed as a pitch. Before the 20th century, the term ...

from the Dead Sea. Their arid country was their best safeguard, for the bottle-shaped cisterns for rain-water which they excavated in the rocky or clay-rich soil were carefully concealed from invaders.

Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq

( ar, أبو محمد المظفر بن نصر ابن سيار الوراق) was an Arab author from Baghdad. He was the compiler of a tenth-century cookbook, the ( ar, links=no, كتاب الطبيخ, ''The Book of Dishes''). This is the earlies ...

's ''Kitab al-Tabikh'', the earliest known Arabic cookbook, contains a recipe for fermented

Fermentation is a metabolic process that produces chemical changes in organic substrates through the action of enzymes. In biochemistry, it is narrowly defined as the extraction of energy from carbohydrates in the absence of oxygen. In food p ...

Nabatean water bread (). The yeast-leavened bread is made with a high quality wheat flour called ''samidh'' that is finely milled and free of bran

Bran, also known as miller's bran, is the hard outer layers of cereal grain. It consists of the combined aleurone and pericarp. Corn (maize) bran also includes the pedicel (tip cap). Along with germ, it is an integral part of whole grains ...

and is baked in a tandoor

A tandoor ( or ) is a large urn-shaped oven, usually made of clay, originating from the Indian Subcontinent. Since antiquity, tandoors have been used to bake unleavened flatbreads, such as roti and naan, as well as to roast meat. The tandoor ...

.

Language

Historians such asIrfan Shahîd

Irfan Arif Shahîd ( ar, عرفان عارف شهيد ; Nazareth, Mandatory Palestine, January 15, 1926 – Washington, D.C., November 9, 2016), born as Erfan Arif Qa'war (), was a scholar in the field of Oriental studies. He was from 1982 unti ...

, Warwick Ball

Warwick Ball is an Australia-born Near-Eastern archaeologist.

Ball has been involved in excavations, architectural studies and monumental restorations in Jordan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Ethiopia and Afghanistan. As a lecturer, he has been involved ...

, Robert G. Hoyland, Michael C. A. Macdonald

Michael C. A. Macdonald FBA is a research associate of the Khalili Research Centre, honorary fellow of Wolfson College, University of Oxford, and fellow of the British Academy. He is a Trustee of the International Association for the Study of Ara ...

, and others believe Nabataeans spoke Arabic as their native language. John F. Healy

John F. Healy ( – 25 April 2012) was a senior scholar and graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge. He served in the Army ( Intelligence Corps) then entered an academic career in Classics/Classical Archaeology at Manchester and London Univers ...

states that "Nabataeans normally spoke a form of Arabic, while, like the Persians etc., they used Aramaic for formal purposes and especially for inscriptions." Proper names on their inscriptions suggest that they were ethnically Arabs who had come under Aramaic influence, and the Nabataeans had already some trace of Aramaic culture when they first appear in history.

Religion

The extent of Nabataean trade resulted in cross-cultural influences that reached as far as the Red Sea coast of southern Arabia. The gods worshiped at Petra were notablyDushara

Dushara, ( Nabataean Arabic: 𐢅𐢈𐢝𐢛𐢀 ''dwšrʾ'') also transliterated as Dusares, is a pre-Islamic Arabian god worshipped by the Nabataeans at Petra and Madain Saleh (of which city he was the patron). Safaitic inscriptions imply h ...

and Al-‘Uzzá

Al-ʻUzzā ( ar, العزى or Old Arabic l ʕuzzeː was one of the three chief goddesses of Arabian religion in pre-Islamic times and she was worshiped by the pre-Islamic Arabs along with al-Lāt and Manāt. A stone cube at Nakhla (nea ...

. Dushara was the supreme deity of the Nabataean Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

, and was the official god of the Nabataean Kingdom who enjoyed special royal patronage. His official position is reflected in multiple inscriptions that render him as "The god of our lord" (The King). The name Dushara is from the Arabic "Dhu ash-Shara": which simply means "the one of Shara", a mountain range south-east of Petra also known as Mount Seir

Mount Seir ( he, הַר-שֵׂעִיר, ''Har Sēʿīr'') is the ancient and biblical name for a mountainous region stretching between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba in the northwestern region of Edom and southeast of the Kingdom of Judah. It ...

. Therefore, from a Nabataean perspective, Dhushara was probably associated with the heavens. However, one theory which connects Dushara with the forest gives a different idea of the god. The eagle was one of the symbols of Dushara. It was widely used in Hegra

HEGRA, which stands for ''High-Energy-Gamma-Ray Astronomy'', was an atmospheric Cherenkov telescope for Gamma-ray astronomy. With its various types of detectors, HEGRA took data between 1987 and 2002, at which point it was dismantled in order ...

as a source of protection for the tombs against thievery.

Nabataean inscriptions from Hegra suggest that Dushara was linked either with the sun, or with Mercury, with which Ruda

Ruda may refer to:

Islands

* Ruda (island), Croatian island in the Elaphiti Archipelago

Rivers

* Ruda (river), a river in Croatia, tributary of the Cetina river

* Ruda (Narew), a river in Poland, tributary of the Narew

* Ruda (Oder), a river i ...

, another Arabian god, was identified. "His throne" was frequently mentioned in inscriptions, certain interpretations of the text consider it as a reference for Dhushara's wife, goddess Harisha. She was probably a solar deity.

However, when the Romans annexed the Nabataean Kingdom, Dushara still had an important role despite losing his former royal privilege. The greatest testimony to the status of the god after the fall of the Nabataean Kingdom was during the 1000th anniversary of the founding of Rome where Dushara was celebrated in Bostra

Bosra ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ, Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially called Busra al-Sham ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ ٱلشَّام, Buṣrā al-Shām), is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Dar ...

by striking coins in his name, Actia Dusaria (linking the god with Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

victory at Actium

Actium or Aktion ( grc, Ἄκτιον) was a town on a promontory in ancient Acarnania at the entrance of the Ambraciot Gulf, off which Octavian gained his celebrated victory, the Battle of Actium, over Antony and Cleopatra, on September 2, 31&n ...

). He was venerated in his Arabian name with a Greek fashion in the reign of an Arabian emperor, Philip.

Sacrifices of animals were common and Porphyry’s De Abstenentia reports that, in Dumat Al-Jandal, a boy was sacrificed annually and was buried underneath an altar. Some scholars have extrapolated this practice to the rest of the Nabataeans.Healey, John F. “Images and Rituals.” The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus. Boston: Brill, 2001. 169–175. Print.

The Nabataeans used to represent their gods as featureless pillars or blocks. Their most common monuments to the gods, commonly known as "god blocks", involved cutting away the whole top of a hill or cliff face so as to leave only a block behind. However, over time the Nabataeans were influenced by Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders wit ...

and Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

and their Gods became anthropomorphic and were represented with human features.

Language

Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

that was heavily influenced by Arabic forms and words. When communicating with other Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

ern peoples, they, like their neighbors, used Aramaic, the region's ''lingua franca''. Therefore, Aramaic was used for commercial and official purposes across the Nabataean political sphere. The Nabataean alphabet

The Nabataean script is an abjad (consonantal alphabet) that was used to write Nabataean Aramaic and Nabataean Arabic from the second century BC onwards.Aramaic alphabet

The ancient Aramaic alphabet was adapted by Arameans from the Phoenician alphabet and became a distinct script by the 8th century BC. It was used to write the Aramaic languages spoken by ancient Aramean pre-Christian tribes throughout the Fer ...

, but it used a distinctive cursive script from which the Arabic alphabet emerged. There are different opinions concerning the development of the Arabic script. J. Starcky considers the Lakhmid

The Lakhmids ( ar, اللخميون, translit=al-Laḫmiyyūn) referred to in Arabic as al-Manādhirah (, romanized as: ) or Banu Lakhm (, romanized as: ) was an Arab kingdom in Southern Iraq and Eastern Arabia, with al-Hirah as their capital, ...

s' Syriac form script as a probable candidate.Nabataean to Arabic: Calligraphy and script development among the pre-Islamic Arabs by John F. Healey p. 44. However, John F. Healey states that: "The Nabataean origin of the Arabic script is now almost universally accepted".

In surviving Nabataean documents, Aramaic legal terms are followed by their equivalents in Arabic. That could suggest that the Nabataeans used Arabic in their legal proceedings but recorded them in Aramaic.

The name may be derived from the same root as Akkadian Akkadian or Accadian may refer to:

* Akkadians, inhabitants of the Akkadian Empire

* Akkadian language, an extinct Eastern Semitic language

* Akkadian literature, literature in this language

* Akkadian cuneiform, early writing system

* Akkadian myt ...

''nabatu'', to shine brightly.

Agriculture

Although not as dry as at present, the area occupied by the Nabataeans was still a desert and required special techniques for agriculture. One was to contour an area of land into a shallow funnel and to plant a single fruit tree in the middle. Before the 'rainy season

The rainy season is the time of year when most of a region's average annual rainfall occurs.

Rainy Season may also refer to:

* ''Rainy Season'' (short story), a 1989 short horror story by Stephen King

* "Rainy Season", a 2018 song by Monni

* '' ...

', which could easily consist of only one or two rain events, the area around the tree was broken up. When the rain came, all the water that collected in the funnel would flow down toward the fruit tree and sink into the ground. The ground, which was largely loess, would seal up when it got wet and retain the water.

In the mid-1950s, a research team headed by Michael Evenari

Michael Evenari (hebr.: מיכאל אבן-ארי, even-ari meaning ''lion's stone''; born as Walter Schwarz 9/10/1904 in Metz - 15/4/1989 in Jerusalem) was an Israeli botanist originally from Germany.

Life and career

Early life and education ...

set up a research station near Avdat (Evenari, Shenan and Tadmor 1971). He focused on the relevance of runoff rainwater management in explaining the mechanism of the ancient agricultural features, such as terraced wadis, channels for collecting runoff rainwater, and the enigmatic phenomenon of "Tuleilat el-Anab". Evenari showed that the runoff rainwater collection systems concentrate water from an area that is five times larger than the area in which the water actually drains.

Another study was conducted by Y. Kedar in 1957, which also focused on the mechanism of the agriculture systems, but he studied soil management

Soil management is the application of operations, practices, and treatments to protect soil and enhance its performance (such as soil fertility or soil mechanics). It includes soil conservation, soil amendment, and optimal soil health. In agricul ...

, and claimed that the ancient agriculture systems were intended to increase the accumulation of loess in wadi

Wadi ( ar, وَادِي, wādī), alternatively ''wād'' ( ar, وَاد), North African Arabic Oued, is the Arabic term traditionally referring to a valley. In some instances, it may refer to a wet ( ephemeral) riverbed that contains water on ...

s and create an infrastructure for agricultural activity. This theory has also been explored by E. Mazor, of the Weizmann Institute of Science

The Weizmann Institute of Science ( he, מכון ויצמן למדע ''Machon Vaitzman LeMada'') is a public research university in Rehovot, Israel, established in 1934, 14 years before the State of Israel. It differs from other Israeli univ ...

.

Nabatean architects and stonemasons

*Apollodorus of Damascus

Apollodorus of Damascus ( grc, Ἀπολλόδωρος ὁ Δαμασκηνός) was a Nabataean architect and engineer from Damascus, Roman Syria, who flourished during the 2nd century AD. As an engineer he authored several technical treatises ...

- Nabataean architect and engineer from Damascus, Roman Syria, who flourished during the 2nd century AD. his massive architectural output gained him immense popularity during his time. He is one of the few architects whose name survives from antiquity, and is credited with introducing several Eastern innovations to the Roman Imperial style, such as making the dome a standard.

* Wahb'allahi - a first century stonemason who worked in the city of Hegra. Wahb'allahi was the brother of the stonemason 'Abdharetat and the father of 'Abd'obodat. He is named in an inscription as the responsible stonemason on the oldest datable grave in Hegra in the ninth year of the Nabataean king Aretas IV (1 BCE-CE).

* 'Abd'obodat son of Wahballahi - a 1st-century Nabatean Stonemason who worked in the city of Hegra. He is named by inscriptions on five of the grave facades typical of Hegra as the executing craftsman. On the basis of the inscriptions, four of the facades can be dated to the reigns of kings Aretas IV and Malichus II. 'Abd'obodat was evidently a successful craftsman. He succeeded his father Wahb'allahi and his uncle 'Abdharetat in at least one workshop in the second generation of Nabatean architects. 'Abd'obodat is considered to be the main representative of one of the two main schools of the Nabataean stonemasons, to which his father, his uncle belonged. Two more grave facades are assigned to the school on the basis of stylistic investigations; 'Abd'obodat is probably to be regarded as the stonemason who carried out the work.

* 'Aftah - a Nabatean stonemason who became prominent in the beginning of the third decade of the first century. 'Aftah is attested in inscriptions on eight of the grave facades in Hegra and one grave as the executing stonemason. The facades are dated to the late reign of King Aretas IV . On one of the facades he worked with Halaf'allahi, on another with Wahbu and Huru . A tenth facade without an inscription was attributed to the 'Aftah sculpture school due to technical and stylistic similarities. He is the main representative of one of the two stonemason schools in the city of Hegra.

* Halaf'allahi - Nabatean stonemason who worked in the city of Hegra in the first century. Halaf'allahi is named in inscriptions on two graves in Hegra as the responsible stonemason in the reign of the Nabataean king Aretas IV. The first grave, which can be dated to the year 26-27 CE, was created together with the stonemason 'Aftah. He is therefore assigned to the workshop of the 'Aftah. Nabataean architects and sculptors were in reality contractors, who negotiated the costs of specific tomb types and their decorations. Tombs were therefore executed based on the desires and financial abilities of their future owners. The activities of Halaf'allahi offer an excellent example of this, as he had been commissioned with the execution of a simple tomb for a person who apparently belonged to the lower middle class. However, he was also in charge of completing a more sophisticated tomb for one of the local military officials.

Archeological sites

*Petra

Petra ( ar, ٱلْبَتْرَاء, Al-Batrāʾ; grc, Πέτρα, "Rock", Nabataean: ), originally known to its inhabitants as Raqmu or Raqēmō, is an historic and archaeological city in southern Jordan. It is adjacent to the mountain of Ja ...

and Little Petra

Little Petra ( ar, البتراء الصغيرة, ''al-batrā aṣ-ṣaġïra''), also known as Siq al-Barid ( ar, سيق البريد, literally "the cold canyon") is an archaeological site located north of Petra and the town of Wadi Musa in th ...

in Jordan

* Bosra

Bosra ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ, Buṣrā), also spelled Bostra, Busrana, Bozrah, Bozra and officially called Busra al-Sham ( ar, بُصْرَىٰ ٱلشَّام, Buṣrā al-Shām), is a town in southern Syria, administratively belonging to the Dar ...

in Syria

* Mada'in Saleh

Hegra ( grc, Ἕγρα), known to Muslims as Al-Hijr (), also known as Mada’in Salih ( ar, مَدَائِن صَالِح, madāʼin Ṣāliḥ, lit=Cities of Salih), is an archaeological site located in the area of Al-'Ula within Medina Provin ...

in northwest Saudi Arabia.

* Jabal al-Lawz in northwest Saudi Arabia.

* Shivta

Shivta ( he, שבטה), originally Sobata ( gr, Σόβατα) or Subeita ( ar, شبطا), is an ancient city in the Negev Desert of Israel located 43 kilometers southwest of Beersheba. Shivta was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in June 2005 ...

in the Negev Desert of Israel; disputed as a Nabataean precursor to a Byzantine colony.

* Avdat

Avdat ( he, עבדת, ar, عبدة, ''Abdah''), also known as Abdah and Ovdat and Obodat, is a site of a ruined Nabataean city in the Negev desert in southern Israel. It was the most important city on the Incense Route after Petra, between the 1 ...

in the Negev Desert of Israel

* Mamshit

Mampsis (Medieval Greek: Μάμψις) or Memphis (Ancient Greek: Μέμφις), today Mamshit ( he, ממשית), Arabic Kurnub, is a former Nabataean caravan stop and Byzantine city. In the Nabataean period, Mampsis was an important station on th ...

in the Negev Desert of Israel

* Haluza

The ancient city of Halasa or Chellous ( gr, Χελλοὺς), Elusa () in the Byzantine period, was a city in the Negev near present-day Kibbutz Mash'abei Sadeh that was once part of the Nabataean Incense Route. It lay on the route from Petra ...

in the Negev Desert of Israel

* Dahab

Dahab ( arz, دهب, , "gold") is a small Egyptian town on the southeast coast of the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt, approximately northeast of Sharm el-Sheikh. Formerly a Bedouin fishing village, Dahab is now considered to be one of Egypt's most tre ...

in South Sinai, Egypt; an excavated Nabataean trading port.

See also

* List of rulers of Nabatea *Azd

The Azd ( ar, أَزْد), or ''Al-Azd'' ( ar, ٱلْأَزْد), are a tribe of Sabaean Arabs.

In ancient times, the Sabaeans inhabited Ma'rib, capital city of the Kingdom of Saba' in modern-day Yemen. Their lands were irrigated by the Ma ...

References

Sources

* * * Healey, John F., ''The Religion of the Nabataeans: A Conspectus'' (Leiden, Brill, 2001) (Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, 136). * * * "Nabat", ''Encyclopedia of Islam'', Volume VII. * *External links

Hecht Museum - Catalogues , The Nabateans in the Negev

Hecht Museum - Exhibitions , The Nabateans in the Negev

��links on Petra and the Nabataeans

NABATÆANS in the ''Jewish Encyclopedia''

Cincinnati Art Museum

��the only collection of ancient Nabataean art outside of Jordan

��Ancient Desert Agriculture Systems Revived (ADASR)

Petra: Lost City of Stone Exhibition

��Canadian Museum of Civilization

"Solving the Enigma of Petra and the Nabataeans"

''Biblical Archaeology Review''

��Petra Crown {{Authority control Ancient Arabic peoples Tribes of Arabia Arab groups Arabs in the Roman Empire History of Saudi Arabia History of Palestine (region) Ancient history of Jordan Ancient Syria Ancient Israel and Judah Gilead