The military history of the Mi'kmaq consisted primarily of

Mi'kmaq

The Mi'kmaq (also ''Mi'gmaq'', ''Lnu'', ''Miꞌkmaw'' or ''Miꞌgmaw''; ; ) are a First Nations people of the Northeastern Woodlands, indigenous to the areas of Canada's Atlantic Provinces and the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec as well as the no ...

warriors (''smáknisk'') who participated in wars against the

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

(the

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

after 1707) independently as well as in coordination with the

Acadian

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the desc ...

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

and

French royal forces. The Mi'kmaq militias remained an effective force for over 75 years before the

Halifax Treaties

The Peace and Friendship Treaties were a series of written documents (or, treaties) that Britain signed between 1725 and 1779 with various Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqiyik (Maliseet), Abenaki, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy peoples (i.e., the Wabanaki Confe ...

were signed (1760–1761). In the nineteenth century, the Mi'kmaq "boasted" that, in their contest with the British, the Mi'kmaq "killed more men than they lost". In 1753,

Charles Morris stated that the Mi'kmaq have the advantage of "no settlement or place of abode, but wandering from place to place in unknown and, therefore, inaccessible woods, is so great that it has hitherto rendered all attempts to surprise them ineffectual". Leadership on both sides of the conflict employed standard colonial warfare, which included

scalping

Scalping is the act of cutting or tearing a part of the human scalp, with hair attached, from the head, and generally occurred in warfare with the scalp being a trophy. Scalp-taking is considered part of the broader cultural practice of the taki ...

non-combatants (e.g., families).

After some engagements against the British during the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, the militias were dormant throughout the nineteenth century, while the Mi'kmaq people used diplomatic efforts to have the local authorities honour the treaties.

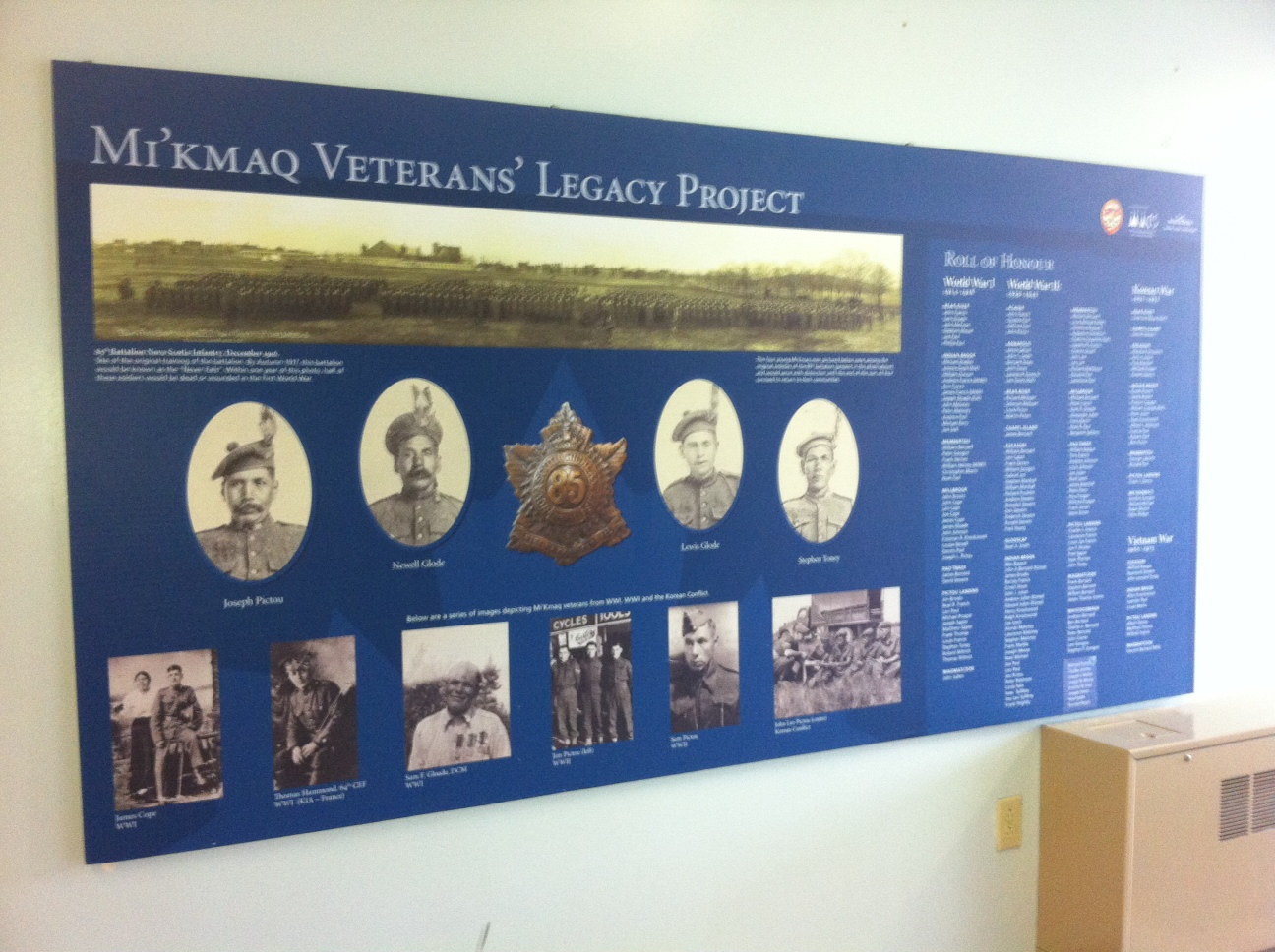

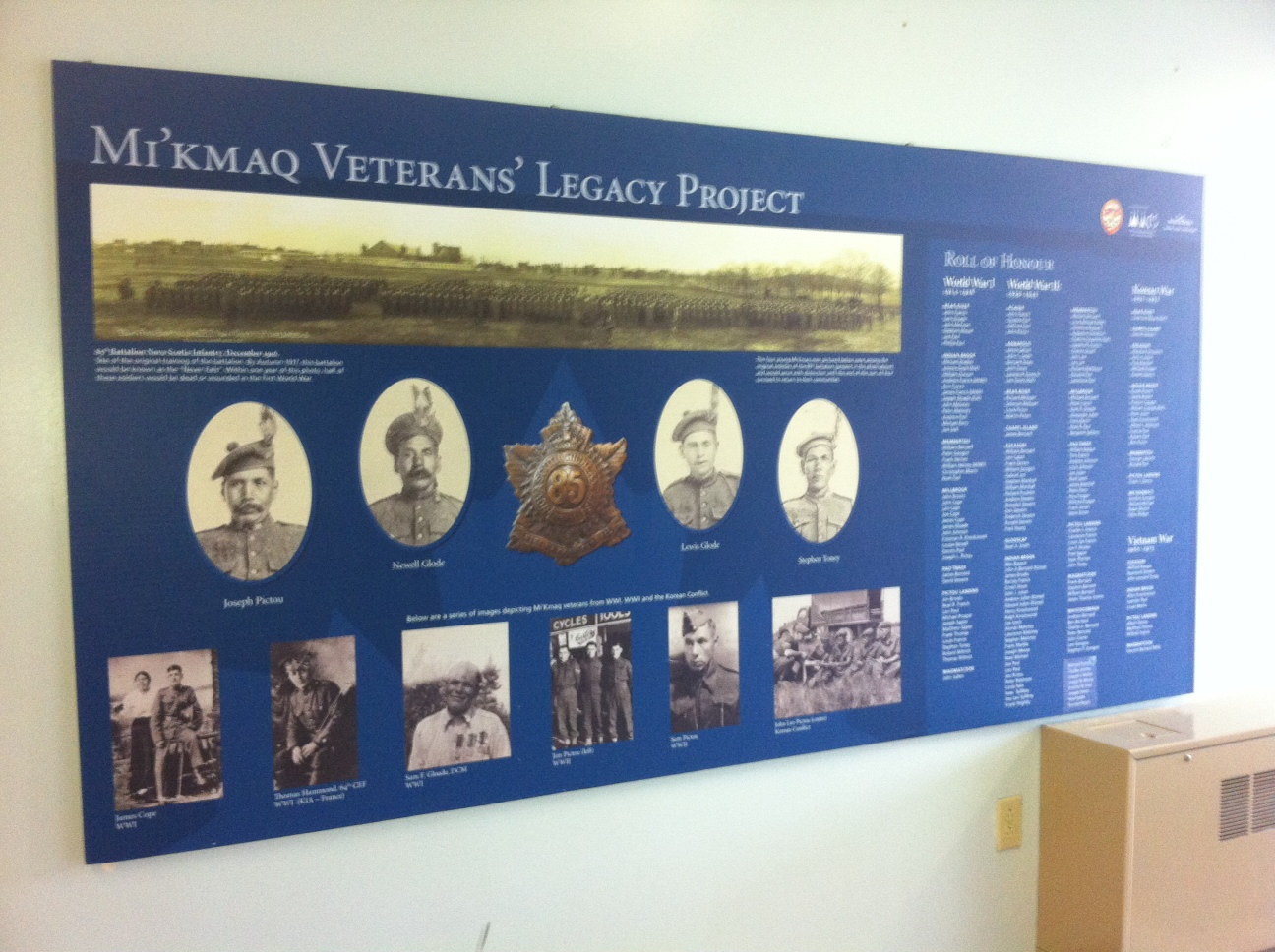

After confederation, Mi'kmaq warriors eventually joined

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by to ...

's war efforts in

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

and

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. The most well-known colonial leaders of these militias were Chief (''Sakamaw'')

Jean-Baptiste Cope

Jean Baptiste Cope (Kopit in Mi’kmaq meaning ‘beaver’) was also known as Major Cope, a title he was probably given from the French military, the highest rank given to Mi’kmaq. Cope was the sakamaw (chief) of the Mi'kmaq people of Shubenaca ...

and Chief

Étienne Bâtard

Étienne Bâtard (died ) was a Mi'kmaq warrior from Miramichi, New Brunswick, Canada.

Bâtard fought in Father Le Loutre's War. He participated in fighting the British in the Battle at Chignecto

The Battle at Chignecto happened during Father ...

.

16th century

Battle at Bae de Bic

According to

Jacques Cartier

Jacques Cartier ( , also , , ; br, Jakez Karter; 31 December 14911 September 1557) was a French- Breton maritime explorer for France. Jacques Cartier was the first European to describe and map the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the shores of ...

, the Battle at

Bae de Bic happened in the spring of 1534, 100 Iroquois warriors massacred a group of 200 Mi'kmaq camped on Massacre Island in the St. Lawrence River. Bae de Bic was an annual gathering place for the Mi'kmaq along the St. Lawrence. Mi'kmaq scouting parties notified the village of the Iroquois attack the evening before the morning attack. They evacuated 30 of the infirm and elderly and about 200 Mi'kmaq left their encampment on the shore and retreated to an island in the bay. They took cover in a cave on the island and covered the entrance with branches. The Iroquois arrived at the village in the morning. Finding it vacated, they divided into search parties but failed to find the Mi'kmaq until the morning of the next day.

The Mi'kmaq warriors defended the tribe against the first Iroquois assault. Initially, after many had been wounded on both sides, with the rising tide, the Mi'kmaq were able to repulse the assault and the Iroquois retreated to the mainland. The Mi'kmaq prepared a fortification on the island in preparation for the next assault at low tide. The Iroquois were again repulsed and retreated to the mainland with the rising tide. By the following morning, the tide was again low and the Iroquois made their final approach. They had prepared arrows that carried fire which burned down the fortification and wiped out the Mi'kmaq. Twenty Iroquois were killed and thirty wounded in the battle. The Iroquois divided into two companies to return to their canoes on the Bouabouscache River.

[Cartier, second voyage, CL, IX][Île du Massacre, Rimouski, QC : Battle between Mi'kmaq and Iroquois c. 1534](_blank)

Battle at Bouabouscache River

Just prior to Battle at Bae de Bic, the Iroquois warriors had left their canoes and hid their provisions on the Bouabousche River, which the Mi'kmaq scouts had discovered and recruited assistance from 25 Maliseet warriors. The Mi'kmaq and Maliseet militia ambushed the first company of Iroquois to arrive at the site. They killed ten and wounded five of the Iroquois warriors before the second company of Iroquois arrived and the Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia retreated to the woods unharmed.

The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia had stolen most of the Iroquois canoes. Leaving twenty wounded behind at the site, 50 Iroquois went to find their hidden provisions. Unable to find their supplies, at the end of the day they returned to the camp, finding that the 20 wounded soldiers that had stayed behind had been slaughtered by the Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia. The following morning, the 38 Iroquois warriors left their camp, killing twelve of their own wounded who would not be able to survive the long journey back to their village. Ten of the Mi'kmaq/Maliseet stayed with the stolen canoes and provisions while the remaining 15 pursued the Iroquois. The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia pursued the Iroquois for three days, killing eleven of the wounded Iroquois stragglers.

Battle at Riviere Trois Pistoles

Shortly after the Battle at Bouabouscache River, the retreating Iroquois set up camp on the Riviere Trois Pistoles to build canoes to return to their village. An Iroquois hunting party was sent to hunt for food. The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia killed the hunting party. The Iroquois went to find their missing hunting party and were ambushed by the Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia. They killed nine of the Iroquois, leaving 29 warriors who retreated to their camp on Riviere Trois Pistoles. The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia divided into two companies and attacked the remaining Iroquois warriors. The battle left 3 Maliseet warriors dead and many others wounded. The Mi'kmaq/Maliseet militia was victorious, however, killing all but six of the Iroquois, whom they took prisoner and later tortured and killed.

Kwedech–Mi'kmaq War

Tradition indicates that there was war in the 16th century between the Kwedech (the St. Lawrence Iroquois) and the Mi'kmaq. The great Mi'kmaq chief Ulgimoo led his people. The conflict was eventually settled through a peace treaty after the Mi'kmaq were successful in removing the Kwedech out of the Maritimes.

17th century

A subgroup of Mi'kmaq who lived in New England were known as

Tarrantine

The Tarrantines were a band of the Mi'kmaq tribe of Native Americans inhabiting northern New England, particularly coastal Maine. The name ''Tarrantine'' is one of the words the Massachusett people used to refer to the ''Mi'kmaq'' people.

In the ...

s. The Tarrantines sent 300 warriors to kill

Nanepashemet

Nanepashemet (died 1619) was a sachem and ''bashabe'' or great leader of the Pawtucket Confederation of Abenaki peoples in present-day New England before the landing of the Pilgrims. He was a leader of Native peoples over a large part of what i ...

and his wife in 1619 at Mystic Fort. The remaining family had been sent off to safe haven. Nanapashemet's death ended the

Massachusetts Federation.

Penobscot–Tarrantine War

Before 1620, the Penobscot-Tarrantine War (1614–1615) (Tarrantine being the New England term for Mi'kmaq) happened in current day Maine, in which the Pawtucket Tribe supported the former. This led later to retaliatory raids by the Tarrantines on the Pawtucket and Agawam (Ipswich) Tribes.

In 1633, Tarrantines raided the camp of

Chief Masconomet at

Agawam in

Essex County.

King Philip's War

The first documented warfare between the Mi'kmaq and the British was during the

First Abenaki War

The First Abenaki War (also known as the northern theatre of King Philip's War) was fought along the New England/Acadia border primarily in present-day Maine. Richard Waldron and Charles Frost led the forces in the northern region, while Jean-Vin ...

(the Maine/Acadia theatre of

King Philip's War

King Philip's War (sometimes called the First Indian War, Metacom's War, Metacomet's War, Pometacomet's Rebellion, or Metacom's Rebellion) was an armed conflict in 1675–1676 between indigenous inhabitants of New England and New England coloni ...

), which was the

Battle of Port La Tour (1677)

The Battle of Port La Tour occurred on July 18, 1677, at Port La Tour, Acadia, as part of the Northeast Coast Campaign during the First Abenaki War (the Maine-Acadia theater of King Phillips War) in which the Mi'kmaq attacked New England fishe ...

. In the wake of King Philip's War, the Mi'kmaq became members of the ''Wapnáki'' (

Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki Confederacy (''Wabenaki, Wobanaki'', translated to "People of the Dawn" or "Easterner") is a North American First Nations and Native American confederation of four principal Eastern Algonquian nations: the Miꞌkmaq, Maliseet ( ...

), an alliance with four other

Algonquian-language nations: the

Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

,

Penobscot

The Penobscot ( Abenaki: ''Pαnawάhpskewi'') are an Indigenous people in North America from the Northeastern Woodlands region. They are organized as a federally recognized tribe in Maine and as a First Nations band government in the Atlantic ...

,

Passamaquoddy

The Passamaquoddy ( Maliseet-Passamaquoddy: ''Peskotomuhkati'') are a Native American/First Nations people who live in northeastern North America. Their traditional homeland, Peskotomuhkatik'','' straddles the Canadian province of New Brunswick ...

, and

Maliseet

The Wəlastəkwewiyik, or Maliseet (, also spelled Malecite), are an Algonquian-speaking First Nation of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They are the indigenous people of the Wolastoq ( Saint John River) valley and its tributaries. Their territory ...

.

The Wabanaki Confederacy allied with French colonists in

Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

. Over a period of seventy-five years, during six wars in Mi'kma'ki (Acadia and Nova Scotia), the Mi'kmaq fought to keep the British from taking over the region. The first war where there is evidence of widespread participation of the Mi'kmaq militias was

King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alli ...

.

King William's War

During

King William's War

King William's War (also known as the Second Indian War, Father Baudoin's War, Castin's War, or the First Intercolonial War in French) was the North American theater of the Nine Years' War (1688–1697), also known as the War of the Grand Alli ...

, the Mi'kmaq militia participated in defending against the British migration toward Mi'kmaki. They fought, with the support of their Wabanaki and French allies, the British along the

Kennebec River

The Kennebec River (Abenaki: ''Kinəpékʷihtəkʷ'') is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map , accessed June 30, 2011 river within the U.S. state of Maine. It rises in Moosehead ...

in southern Maine which was the natural boundary between Acadia and New England. Toward this end, the Mi'kmaq militia and the Maliseet operated from their headquarters at

Meductic on the Saint John River. They joined the New France expedition against present-day

Bristol, Maine

Bristol, known from 1632 to 1765 as Pemaquid (; today a village within the town) is a town in Lincoln County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,834 at the 2020 census. A fishing and resort area, Bristol includes the villages of New ...

(the

siege of Pemaquid),

Salmon Falls and present-day

Portland, Maine

Portland is the largest city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 68,408 in April 2020. The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 104th-largest metropo ...

. Mi'kmaq tortured the British prisoners taken during these conflicts and the

Battle of Fort Loyal

The Battle of Falmouth (also known as the Battle of Fort Loyal) (May 16–20, 1690) involved Joseph-François Hertel de la Fresnière and Baron de St Castin leading troops as well as the Wabanaki Confederacy (Mi'kmaq and Maliseet from Fort Me ...

. In response, the New Englanders retaliated by attacking

Port Royal

Port Royal is a village located at the end of the Palisadoes, at the mouth of Kingston Harbour, in southeastern Jamaica. Founded in 1494 by the Spanish, it was once the largest city in the Caribbean, functioning as the centre of shipping and ...

and present-day

Guysborough. In 1692, Mi'kmaq from across the region participated in the

Raid on Wells

The Raid on Wells occurred during King William's War when French and Wabanaki Confederacy forces from New France attacked the English settlement at Wells, Maine, a frontier town on the coast below Acadia. The principal attack (1692) was led by L ...

. In 1694, the Maliseet participated in the

Raid on Oyster River

The Raid on Oyster River (also known as the Oyster River Massacre) happened during King William's War, on July 18, 1694, at present-day Durham, New Hampshire.

Historical context

Massachusetts responded to the Siege of Pemaquid (1689) by send ...

at present-day

Durham, New Hampshire

Durham is a New England town, town in Strafford County, New Hampshire, Strafford County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 15,490 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, up from 14,638 at the 2010 census.United States Censu ...

.

Two years later, New France, led by

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

, returned and fought a

naval battle in the Bay of Fundy before moving on to raid

Bristol, Maine

Bristol, known from 1632 to 1765 as Pemaquid (; today a village within the town) is a town in Lincoln County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,834 at the 2020 census. A fishing and resort area, Bristol includes the villages of New ...

again. In the lead up to this battle in Fundy Bay, on 5 July, 140 natives (Mi'kmaq and Maliseet), with

Jacques Testard de Montigny

Jacques Testard de Montigny (1663–1737) was an officer in the French Marines in Canada. Biography

Born in Montreal into a merchant family, Montigny first saw military action as a volunteer on the expedition against Schenectady in 1690. Two ye ...

and Chevalier, from their location of Manawoganish island, ambushed the crews of four English vessels. Some of the English were coming ashore in a long boat to get firewood. A native killed five of the nine men in the boat. The Mi'kmaq burned the vessel under the direction of Father Florentine (missionary to the Micmacs at Chignectou).

In retaliation for the

siege of Pemaquid that followed, the New Englanders, led by

Benjamin Church, engaged in a

Raid on Chignecto and the

siege of the capital of Acadia at Fort Nashwaak. After the siege of Pemaquid, d'Iberville led a force of 124 Canadians, Acadians, Mi'kmaq, and Abenaki in the

Avalon Peninsula Campaign.

They destroyed almost every English settlement in Newfoundland, over 100 English were killed, many times that number captured, and almost 500 deported to England or France.

18th century

Queen Anne's War

During

Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

, the Mi'kmaq militias participated again in defending Mi'kmaki against the migration of the British into the region. Again, they made numerous raids along the Acadia/ New England border. They made numerous raids on New England settlements along the border in the

Northeast Coast Campaign.

In retaliation for the Mi'kmaq militia raids (and the

Raid on Deerfield

The 1704 Raid on Deerfield (also known as the Deerfield Massacre) occurred during Queen Anne's War on February 29 when French and Native American forces under the command of Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville attacked the English frontier settle ...

), Major Benjamin Church went on his fifth and final expedition to Acadia. He raided present-day Castine, Maine and then continued on by conducting raids against

Grand Pre, Pisiquid and Chignecto. In the summer of 1705, Mi'kmaq killed a fisherman gathering "wood off Cape Sables." A few years later, defeated in the siege of Pemaquid, Captain March made an unsuccessful

siege on the Capital of Acadia, Port Royal (1707). The New Englanders were successful with the

siege of Port Royal, while the Wabanaki Confederacy were successful in the nearby

Battle of Bloody Creek in 1711.

During

Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

, the Conquest of Acadia (1710) was confirmed by the

Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vacant throne ...

of 1713. Acadia was defined as mainland-Nova Scotia by the French. Present-day New Brunswick and most of Maine remained contested territory, while New England conceded Île St Jean and Île Royale; present-day Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton respectively, as French territory. On the latter island, the French established a fortress at

Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour ...

to guard the sea approaches to Quebec. In 1712, the Mi'kmaq captured over twenty New England fishing vessels off the coast of Nova Scotia.

In 1715, the Mi'kmaq were told that the British now claimed their ancient territory by the Treaty of Utrecht, in which the Mi'kmaq were not involved. They formally complained to the French commander at Louisbourg about the French king transferring the sovereignty of their nation when he did not possess it. They were only then informed that the French had claimed legal possession of their country for a century, on account of laws decreed by kings in Europe.

Native people saw no reason to accept British pretensions to rule Nova Scotia.

There was an attempt by the British after the war to settle outside of Mi'kmaq accommodation of the British trading posts at Canso and Annapolis. On 14 May 1715, New England naval commander

Cyprian Southack attempted to create a permanent fishing station at a place he named "Cape Roseway" (now known as

Shelburne). Shortly after he established himself, in July 1715, the Mi'kmaq raided the station and burned it to the ground. In July 1715, two of the Boston merchants who had had their fishing vessels seized off Cape Sable by the Mi'kmaq under renegade Joseph Mius reported that "the Indians say the Lands are theirs and they can make Warr and peace when they please...."

In response, Southack led a raid on

Canso, Nova Scotia

Canso is a community in Guysborough County, on the north-eastern tip of mainland Nova Scotia, Canada, next to Chedabucto Bay. In January 2012, it ceased to be a separate town and as of July 2012 was amalgamated into the Municipality of the Di ...

(1718) and encouraged Governor Phillips to fortify Canso.

Father Rale's War

During the escalation that preceded

Father Rale's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

(1722–1725), some Mi'kmaq raided

Fort William Augustus

Fort William Augustus (also known as Grassy Island Fort, Fort Phillips) was a British fort built on Grassy Island off of Canso, Nova Scotia during the lead up to Father Rale's War (1720). In the wake of The Squirrel Affair and the British attac ...

at

Canso, Nova Scotia

Canso is a community in Guysborough County, on the north-eastern tip of mainland Nova Scotia, Canada, next to Chedabucto Bay. In January 2012, it ceased to be a separate town and as of July 2012 was amalgamated into the Municipality of the Di ...

(1720). Under potential siege, in May 1722, Lieutenant Governor

John Doucett

John Doucett (Doucette) (died November 19, 1726) was probably of French descent although he did not speak the language and was likely born in England. He was a career military man and, from 1702 on, received several promotions.

He was appointed ...

took 22 Miꞌkmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked. In July 1722, the

Abenaki

The Abenaki ( Abenaki: ''Wαpánahki'') are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands of Canada and the United States. They are an Algonquian-speaking people and part of the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Eastern Abenaki language was pre ...

and Mi'kmaq created a blockade of

Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the ne ...

, with the intent of starving the capital. The natives captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners from present-day

Yarmouth to

Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels from the

Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy (french: Baie de Fundy) is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its extremely high tidal range is t ...

.

As a result of the escalating conflict, Massachusetts Governor

Samuel Shute

Samuel Shute (January 12, 1662 – April 15, 1742) was an English military officer and royal governor of the provinces of Massachusetts and New Hampshire. After serving in the Nine Years' War and the War of the Spanish Succession, he was appoin ...

officially declared war on 22 July 1722. The first battle of Father Rale's War happened in the Nova Scotia theatre. In response to the blockade of Annapolis Royal, at the end of July 1722, New England launched a campaign to end the blockade and retrieve over 86 New England prisoners taken by the natives. One of these operations resulted in the

Battle at Jeddore.

Raid on Georgetown

On 10 September 1722, in conjunction with Father Rale at Norridgewock, 400 or 500

St. Francis (

Odanak, Quebec

Odanak is an Abenaki First Nations reserve in the Central Quebec region, Quebec, Canada. The mostly First Nations population as of the Canada 2021 Census was 481. The territory is located near the mouth of the Saint-François River at its conflu ...

) and Miꞌkmaq fell upon Georgetown (present-day

Arrowsic, Maine

Arrowsic is a town in Sagadahoc County, Maine, United States. The population is 477 as of the 2020 United States Census. It is part of the Portland– South Portland–Biddeford, Maine metropolitan statistical area. During the French and Indian ...

). Captain Penhallow discharged musketry from a small guard, wounding three of the Indians and killing another. This defense gave the inhabitants of the village time to retreat into the fort. In full possession of the undefended village, the Indians killed fifty head of cattle and set fire to twenty-six houses outside the fort. The Indians then assaulted the fort, killing one New Englander. Georgetown was burned.

That night Colonel Walton and Captain Harman arrived with thirty men, to which were joined about forty men from the fort under Captains Penhallow and Temple. The combined force of seventy men attacked the natives but were overwhelmed by their numbers. The New Englanders then retreated back into the fort. Viewing further attacks on the fort as useless, the Indians eventually retired up the river.

During their return to Norridgewock the natives attacked Fort Richmond. Fort Richmond was attacked in a three-hour siege. Houses were burned and cattle slain, but the fort held. Brunswick and other settlements near the mouth of the Kennebec were burned.

The next was a raid on

Canso in 1723.

During the 1724 Northeast Coast campaign, assisted by the Mi'kmaq from Cape Sable Island, the natives also engaged in a naval campaign.

In just a few weeks, they had captured 22 vessels, killing 22 New Englanders and taking more prisoner. They also made an unsuccessful siege of St. George's Fort in Thomaston, Maine.

In early July 1724, a militia of sixty Mi'kmaq and Maliseet raided Annapolis Royal. They killed and scalped a sergeant and a private, wounded four more soldiers, and terrorized the village. They also burned houses and took prisoners. The British responded by executing one of the Mi'kmaq hostages on the same spot the sergeant was killed. They also burned three Acadian houses in retaliation.

As a result of the raid, three blockhouses were built to protect the town. The Acadian church was moved closer to the fort so that it could be more easily monitored.

In 1725, sixty Abenaki and Mi'kmaq launched another attack on Canso, destroying two houses and killing six people.

The treaty that ended the war marked a significant shift in European relations with the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet. For the first time a European empire formally acknowledged that its dominion over Nova Scotia would have to be negotiated with the region's indigenous inhabitants. The treaty was invoked as recently as 1999 in the

Donald Marshall case.

King George's War

News of war declarations reached the French

fortress at Louisbourg first, on 3 May 1744, and the forces there wasted little time in beginning hostilities, which would become known as

King George's War

King George's War (1744–1748) is the name given to the military operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in t ...

. Within a week of the arrival of the news of war a military expedition to Canso was agreed upon, and on 23 May, a flotilla left Louisbourg harbour. In this same month British Captain David Donahue of the Resolution took prisoner the chief of the Mi'kmaq people of Île-Royale Jacques Pandanuques with his family to Boston and killed him. Donahue used the same strategy of posing as a French ship to entrap Chief Pandanuques as he does in the

Naval battle off Tatamagouche

The action of 15 June 1745 (also known as the Battle of Famme Goose Bay) was a naval encounter between three New England vessels and a French and native relief convoy en route to relieve the Siege of Louisbourg (1745) during King George's War. ...

, after which Donahue was tortured and killed by the Mi'kmaq.

Concerned about their overland supply lines to

Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirte ...

and seeking revenge for the death of their chief, the Mi'kmaq and French first

raided the British fishing port of Canso on 23 May. In response, Governor Shirley of Massachusetts declared war against the Mi'kmaq and put a bounty out for their scalps. The Mi'kmaq and French then organized an attack on

Annapolis Royal

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the ne ...

, then the capital of

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

. However, French forces were delayed in departing Louisbourg, and their Mi'kmaq and Maliseet allies decided to

attack on their own in early July. Annapolis had received news of the war declaration, and was somewhat prepared when the Indians began besieging

Fort Anne

Fort Anne (first established in 1629 as the Scottish Charles Fort) is a four-bastion fort built to protect the harbour of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. The fort repelled all French attacks during the early stages of King George's War.

Now desig ...

. Lacking heavy weapons, the Indians withdrew after a few days. Then, in mid-August, a larger French force arrived before Fort Anne, but was also unable to mount an effective attack or siege against the garrison, which was relieved by the New England company of

Gorham's Rangers. Gorham led his native rangers in a surprise raid on a nearby Mi'kmaq encampment. They killed and mutilated the bodies of women and children. The Mi'kmaq withdrew and Duvivier was forced to retreat back to Grand Pre on October 5.

During the

siege of Annapolis Royal, the Mi'kmaq and Maliseet took prisoner

William Pote and some of

Gorham's Rangers. Pote was taken to the Maliseet village Aukpaque on the Saint John River. While at the village, Mi'kmaq from Nova Scotia arrived and, on 6 July 6 1745, tortured him and a Mohawk ranger from Gorham's company named Jacob, as retribution for the killing of their family members by Ranger John Gorham during the

Siege of Annapolis Royal (1744). On July 10, Pote witnessed another act of revenge when the Mi'kmaq tortured a Mohawk ranger from Gorham's company at

Meductic.

Naval battle off Tatamagouche

Many Mi'kmaq warriors and French Officer

Paul Marin de la Malgue Paul Marin de la Malgue ( bap. 19 March 1692 – 29 October 1753) was the eldest son of Charles-Paul Marin de la Malgue and Catherine Niquet. He was born in Montreal and, as many of the prominent historical figures of his time, had a military ca ...

were thwarted from helping to protect Louisbourg by Captain Donahew, who defeated them in the

naval battle off Tatamagouche

The action of 15 June 1745 (also known as the Battle of Famme Goose Bay) was a naval encounter between three New England vessels and a French and native relief convoy en route to relieve the Siege of Louisbourg (1745) during King George's War. ...

(and had earlier killed the Mi'kmaq chief of Cape Breton). In 1745, British colonial forces conducted the siege of Port Toulouse (St. Peter's) and then

captured Fortress Louisbourg after a siege of six weeks. Weeks after the fall of Louisbourg, Donahew and Fones again engaged Marin, who was now nearing the Strait of Canso. Donahew and 11 of his men put ashore and were immediately surrounded by 300 Indians. The captain and five of his men were slain and the remaining six were taken prisoner. The Indians were said to have cut open Donahew's chest, sucked his blood, then eaten parts of him and his five companions. This tale significantly heightened the sense of gloom and frustration settling over the fortress. On July 19, the 12-gun provincial cruiser of Donavan's the Resolution sailed slowly into the harbour with her colours flying at half-mast. The horrifying tale of the fate of her captain, David Donahew, and five crew members spread rapidly through the fortress. Miꞌkmaw fighters remained outside Louisbourg, striking at those who went for firewood or food.

In response to the siege of Louisbourg, Mi'kmaq warriors engage in the

Northeast Coast campaign.

The Campaign began when, on 19 July, Mi'kmaq from Nova Scotia, Maliseet and some from St. Francois attacked Fort St. George (Thomaston) and New Castle. They set fire to numerous buildings; killed cattle and took one villager captive. They also killed a person at Saco.

In 1745, Mi'kmaq killed seven English crew at

LaHave, Nova Scotia

LaHave (''La Hève'') is a Canadian community in Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia. The community is located across the river from Riverport and approximately 15 kilometres from the town of Bridgewater. Once the capital of Acadia, it is located o ...

and brought their scalps to

Sieur Marin. The English did not dry any fish on the east coast of Acadia for fear of being killed by the Mi'kmaq. By the end of 1745, French reports were clear that, "the English have been deterred from forming any settlement in Acadia solely by the dread of these Indians" and that the French see themselves under native "protection".

France launched

a major expedition to recover Acadia in 1746. Beset by storms, disease, and finally the death of its commander, the

Duc d'Anville, it returned to France in tatters without reaching its objective. The disease of the crew, in turn, spread throughout the Mi'kmaq tribes killing hundreds.

Newfoundland

In response to the

Newfoundland campaign, the following year the Mi'kmaq militia from Île-Royale raiding various British outposts in Newfoundland in August 1745. They attacked several British houses, taking 23 prisoners. The following spring the Mi'kmaq began to take 12 of the prisoners to a rendezvous point close to St. John's, en route to Quebec. The British prisoners managed to kill their Mi'kmaq captors at the rendezvous site near St. John. Two days later, another group of Mi'kmaq took the remaining 11 British prisoners to the same rendezvous point. Discovering the fate of the Mi'kmaq captors, the other Mi'kmaq killed the remaining 11 British prisoners.

Father Le Loutre's War

Despite the British

Conquest of Acadia in 1710, Nova Scotia remained primarily occupied by Catholic Acadians and Mi'kmaq. To prevent the establishment of Protestant settlements in the region, Mi'kmaq raided the early British settlements of present-day

Shelburne (1715) and

Canso (1720). A generation later,

Father Le Loutre's War

Father Le Loutre's War (1749–1755), also known as the Indian War, the Mi'kmaq War and the Anglo-Mi'kmaq War, took place between King George's War and the French and Indian War in Acadia and Nova Scotia. On one side of the conflict, the Br ...

began when

Edward Cornwallis

Edward Cornwallis ( – 14 January 1776) was a British career military officer and was a member of the aristocratic Cornwallis family, who reached the rank of Lieutenant General. After Cornwallis fought in Scotland, putting down the Jacob ...

arrived to establish

Halifax with 13 transports on June 21, 1749. By unilaterally establishing Halifax, historian William Wicken asserts the British were violating earlier treaties with the Mi'kmaq (1726), which were signed after

Father Rale's War

Dummer's War (1722–1725) is also known as Father Rale's War, Lovewell's War, Greylock's War, the Three Years War, the Wabanaki-New England War, or the Fourth Anglo-Abenaki War. It was a series of battles between the New England Colonies and the ...

.

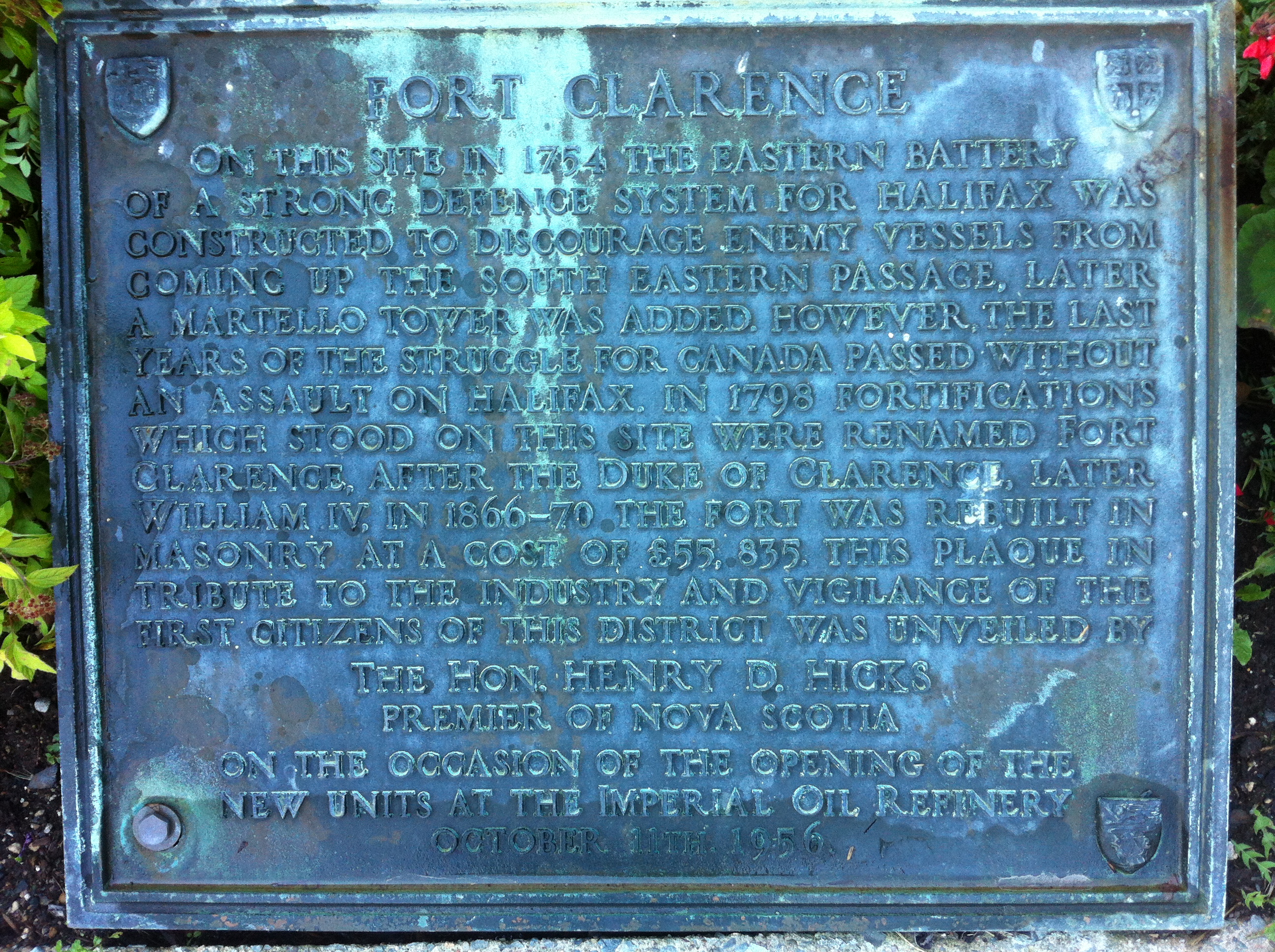

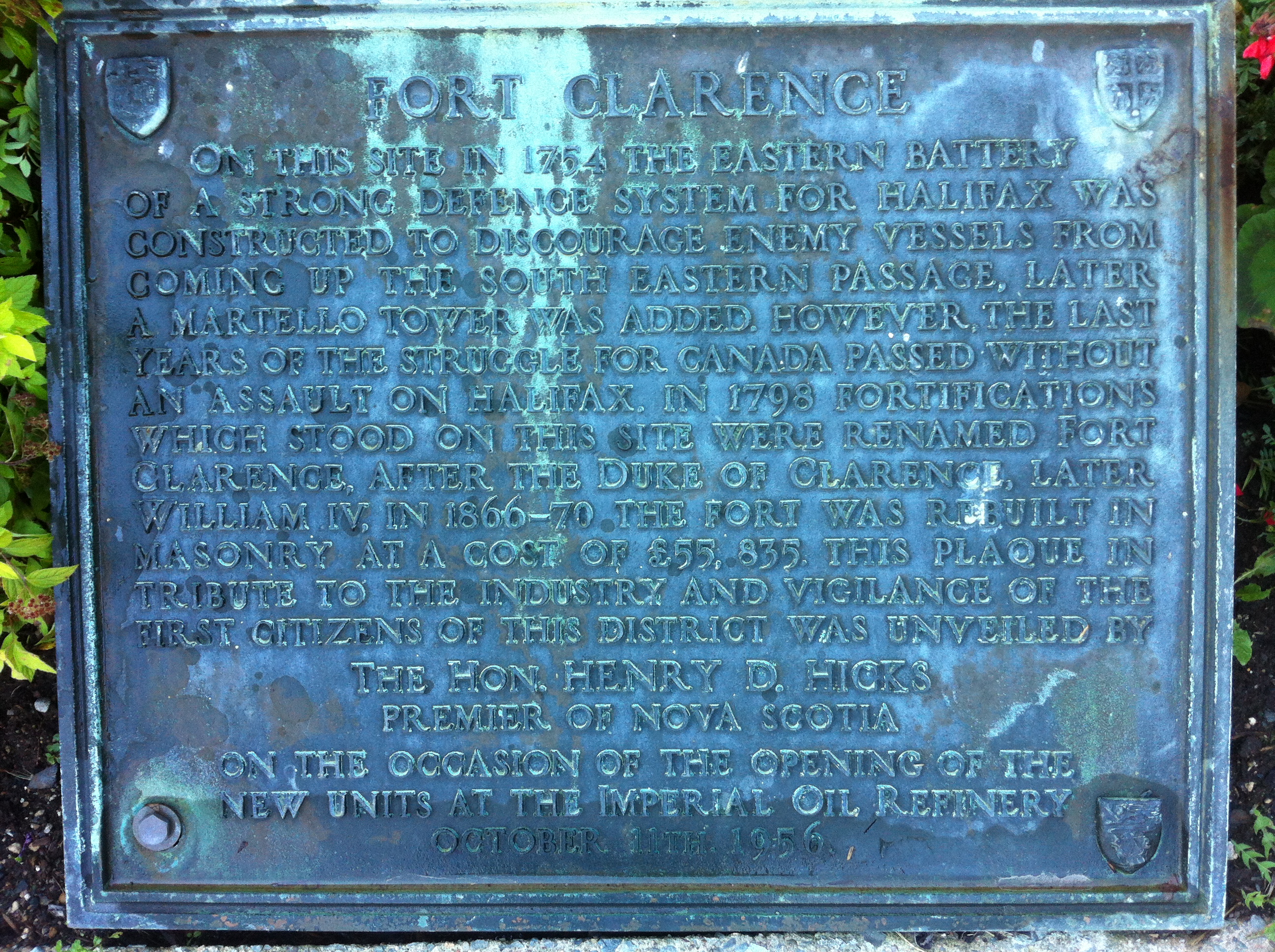

The British quickly began to build other settlements. To guard against Mi'kmaq, Acadian, and French attacks on the new Protestant settlements, British fortifications were erected in Halifax

(Citadel Hill) (1749), Bedford (

Fort Sackville

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the French, British and U.S. forces built and occupied a number of forts at Vincennes, Indiana. These outposts commanded a strategic position on the Wabash River. The names of the installations were chan ...

) (1749), Dartmouth (1750),

Lunenburg (1753) and

Lawrencetown (1754). There were numerous Miꞌkmaw and Acadian raids on these villages such as the

Raid on Dartmouth (1751)

The Raid on Dartmouth (also referred to as the Dartmouth Massacre) occurred during Father Le Loutre's War on May 13, 1751, when a Miꞌkmaq and Acadian militia from Chignecto, under the command of Acadian Joseph Broussard, raided Dartmouth, No ...

.

Within 18 months of establishing Halifax, the British also took firm control of peninsula Nova Scotia by building fortifications in all the major Acadian communities: present-day Windsor (

Fort Edward); Grand Pre (

Fort Vieux Logis) and Chignecto (

Fort Lawrence). (A British fort already existed at the other major Acadian centre of

Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the ne ...

. Cobequid remained without a fort.) There were numerous Mi'kmaq and Acadian raids on these fortifications.

Raid on Dartmouth

The Mi'kmaq saw the founding of Halifax without negotiation as a violation of earlier agreements with the British. On 24 September 1749, the Mi'kmaq formally declared their hostility to the British plans for settlement without more formal negotiations.

[ On 30 September 1749, about forty Mi'kmaq attacked six men, who were under the command of Major Gilman, who were in ]Dartmouth, Nova Scotia

Dartmouth ( ) is an urban community and former city located in the Halifax, Nova Scotia, Halifax Regional Municipality of Nova Scotia, Canada. Dartmouth is located on the eastern shore of Halifax Harbour. Dartmouth has been nicknamed the City of ...

cutting trees near a saw mill. Four of them were killed on the spot, one was taken prisoner and one escaped. Two of the men were scalped and the heads of the others were cut off. Major Gilman and others in his party escaped and gave the alarm. A detachment of rangers was sent after the raiding party and cut off the heads of two Mi'kmaq and scalped one. This raid was the first of eight against Dartmouth during the war.

Siege of Grand Pre

Two months later, on 27 November 1749, 300 Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and Acadians attacked Fort Vieux Logis, recently established by the British in the Acadian community of Grand Pre. The fort was under the command of Captain Handfield. The Native and Acadian militia killed the sentries (guards) who were firing on them. The Natives then captured Lieutenant John Hamilton and eighteen soldiers under his command, while surveying the fort's environs. After the British soldiers were captured, the native and Acadian militias made several attempts over the next week to lay siege to the fort before breaking off the engagement. Gorham's Rangers was sent to relieve the fort. When he arrived, the militia had already departed with the prisoners. The prisoners spent several years in captivity before being ransomed.

Battle at St. Croix

The following spring, on 18 March 1750, John Gorham and his Rangers left Fort Sackville (at present day

The following spring, on 18 March 1750, John Gorham and his Rangers left Fort Sackville (at present day Bedford, Nova Scotia

Bedford is a community of the Halifax Regional Municipality, in Nova Scotia, Canada.

History

The area of Bedford has evidence of Indigenous peoples dating back thousands of years. Petroglyphs are found at Bedford Petroglyphs National Historic ...

), under orders from Governor Cornwallis, to march to Piziquid (present day Windsor, Nova Scotia

Windsor is a community located in Hants County, Nova Scotia, Canada. It is a service centre for the western part of the county and is situated on Highway 101.

The community has a history dating back to its use by the Mi'kmaq Nation for seve ...

). Gorham's mission was to establish a blockhouse at Piziquid, which became Fort Edward, and to seize the property of Acadians who had participated in the Siege of Grand Pre

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characteri ...

.

Arriving at about noon on 20 March at the Acadian village of Five Houses beside the St. Croix River, Gorham and his men found all the houses deserted. Seeing a group of Mi'kmaq hiding in the bushes on the opposite shore, the Rangers opened fire. The skirmish deteriorated into a siege, with Gorham's men taking refuge in a sawmill and two of the houses. During the fighting, the Rangers suffered three wounded, including Gorham, who sustained a bullet in the thigh. As the fighting intensified, a request was sent back to Fort Sackville for reinforcements.

Responding to the call for assistance on 22 March, Governor Cornwallis ordered Captain William Clapham

William Clapham (1722 – 28 May, 1763) was an American military officer who participated in the construction of several forts in Pennsylvania during the French and Indian War. He was considered a competent commander in engagements with French ...

's and Captain St. Loe's Regiments, equipped with two field guns, to join Gorham at Piziquid. The additional troops and artillery turned the tide for Gorham and forced the Mi'kmaq to withdraw.

Gorham proceeded to present-day Windsor and forced Acadians to dismantle their church—Notre Dame de l'Assomption—so that Fort Edward could be built in its place.

Raids on Halifax

There were four raids on Halifax during the war. The first raid happened in October 1750, while in the woods on peninsular Halifax, Mi'kmaq scalped two British people and took six prisoner: Cornwallis' gardener, his son were tortured and scalped. The Mi'kmaq buried the son while the gardener's body was left behind and the other six persons were taken prisoner to Grand Pre for five months. Another author, Thomas Akins, puts the month of this raid in July and writes that there were six British attacked, two were scalped and four were taken prisoner and never seen again. Shortly after this raid, Cornwallis learned that the Mi'kmaq had received payment from the French at Chignecto for five prisoners taken at Halifax as well as prisoners taken earlier at Dartmouth and Grand Pre.

In 1751, there were two attacks on blockhouses surrounding Halifax. Mi'kmaq attacked the North Blockhouse (located at the north end of Joseph Howe Drive) and killed the men on guard. Mi'kmaq also attacked near the South Blockhouse (located at the south end of Joseph Howe Drive), at a sawmill on a stream flowing out of Chocolate Lake into the Northwest Arm. They killed two men.

There were four raids on Halifax during the war. The first raid happened in October 1750, while in the woods on peninsular Halifax, Mi'kmaq scalped two British people and took six prisoner: Cornwallis' gardener, his son were tortured and scalped. The Mi'kmaq buried the son while the gardener's body was left behind and the other six persons were taken prisoner to Grand Pre for five months. Another author, Thomas Akins, puts the month of this raid in July and writes that there were six British attacked, two were scalped and four were taken prisoner and never seen again. Shortly after this raid, Cornwallis learned that the Mi'kmaq had received payment from the French at Chignecto for five prisoners taken at Halifax as well as prisoners taken earlier at Dartmouth and Grand Pre.

In 1751, there were two attacks on blockhouses surrounding Halifax. Mi'kmaq attacked the North Blockhouse (located at the north end of Joseph Howe Drive) and killed the men on guard. Mi'kmaq also attacked near the South Blockhouse (located at the south end of Joseph Howe Drive), at a sawmill on a stream flowing out of Chocolate Lake into the Northwest Arm. They killed two men.

Raids on Dartmouth

There were six raids on Dartmouth during this time period. In July 1750, the Mi'kmaq killed and scalped 7 men who were at work in Dartmouth.

In August 1750, 353 people arrived on the Alderney and began the town of Dartmouth. The town was laid out in the autumn of that year. The following month, on September 30, 1750, Dartmouth was attacked again by the Mi'kmaq and five more residents were killed. In October 1750 a group of about eight men went out "to take their diversion; and as they were fowling, they were attacked by the Indians, who took the whole prisoners; scalped ... newith a large knife, which they wear for that purpose, and threw him into the sea ..."

The following spring, on March 26, 1751, the Mi'kmaq attacked again, killing fifteen settlers and wounding seven, three of which would later die of their wounds. They took six captives, and the regulars who pursued the Mi'kmaq fell into an ambush in which they lost a sergeant killed. Two days later, on March 28, 1751, Mi'kmaq abducted another three settlers.

Two months later, on 13 May 1751, Broussard led sixty Mi'kmaq and Acadians to attack Dartmouth again, in what would be known as the "Dartmouth Massacre". Broussard and the others killed twenty settlers—mutilating men, women, children and babies—and took more prisoner. A sergeant was also killed and his body mutilated. They destroyed the buildings. Captain William Clapham and sixty soldiers were on duty and fired from the blockhouse. The British killed six Mi'kmaq warriors, but were only able to retrieve one scalp that they took to Halifax. Those at a camp at Dartmouth Cove, led by John Wisdom, assisted the settlers. Upon returning to their camp the next day they found the Mi'kmaq had also raided their camp and taken a prisoner. All the settlers were scalped by the Mi'kmaq. The British took what remained of the bodies to Halifax for burial in the Old Burying Ground. Douglas William Trider list the 34 people who were buried in Halifax between 13 May – 15 June 1751; four of whom were soldiers.

In 1752, the Mi'kmaq attacks on the British along the coast, both east and west of Halifax, were frequent. Those who were engaged in the fisheries were compelled to stay on land because they were the primary targets. In early July, New Englanders killed and scalped two Mi'kmaq girls and one boy off the coast of Cape Sable (Port La Tour, Nova Scotia

Port La Tour is a community in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, located in the Municipality of the District of Barrington of Shelburne County.

The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada asserts that Fort Saint Louis is located at Po ...

). In August, at St. Peter's, Nova Scotia, Mi'kmaq seized two schooners—the ''Friendship'' from Halifax and the ''Dolphin'' from New England—along with 21 prisoners who were captured and ransomed.

On 14 September 1752, Governor Peregrine Hopson

Peregrine Thomas Hopson (5 June 1696 – 27 February 1759) was a British army officer who commanded the 40th Regiment of Foot and saw extensive service during the eighteenth century and rose to the rank of Major General. He also served as Briti ...

and the Nova Scotia Council

Formally known as "His Majesty's Council of Nova Scotia", the Nova Scotia Council (1720–1838) was the original British administrative, legislative and judicial body in Nova Scotia. The Nova Scotia Council was also known as the Annapolis Counci ...

negotiated the 1752 Peace Treaty with Jean-Baptiste Cope

Jean Baptiste Cope (Kopit in Mi’kmaq meaning ‘beaver’) was also known as Major Cope, a title he was probably given from the French military, the highest rank given to Mi’kmaq. Cope was the sakamaw (chief) of the Mi'kmaq people of Shubenaca ...

. (The treaty was signed officially on 22 November 1752.) Cope was unsuccessful in getting support for the treaty from other Mi'kmaq leaders. Cope burned the treaty six months after he signed it. Despite the collapse of peace on the eastern shore, the British did not formally renounce the Treaty of 1752 until 1756.

Attack at Mocodome (Country Harbour)

On 21 February 1753, nine Mi'kmaq from Nartigouneche (present-day Antigonish, Nova Scotia

, settlement_type = Town

, image_skyline = File:St Ninian's Cathedral Antigonish Spring.jpg

, image_caption = St. Ninian's Cathedral

, image_flag = Flag of Antigonish.p ...

) in canoes attacked a British vessel at Country Harbour, Nova Scotia

Country Harbour (formerly named Mocodome) is a rural community in Guysborough County, Nova Scotia, Canada. The community is situated on a large deep natural harbour of the same name and is located along the province's Eastern Shore close to Canso ...

. The vessel was from Canso, Nova Scotia

Canso is a community in Guysborough County, on the north-eastern tip of mainland Nova Scotia, Canada, next to Chedabucto Bay. In January 2012, it ceased to be a separate town and as of July 2012 was amalgamated into the Municipality of the Di ...

and had a crew of four. The Mi'kmaq fired on them and drove them toward the shore. Other natives joined in and boarded the schooner, forcing them to run their vessel into an inlet. The Mi'kmaq killed and scalped two of the British and took two others captive. After seven weeks in captivity, on 8 April, the two British prisoners killed six Mi'kmaq and managed to escape. Stephen Patterson reports the attack happened on the coast between Country Harbour and Tor Bay. Whitehead reports the location was a little harbour to the westward of Torbay, "Martingo", "port of Mocodome". Beamish Murdoch in ''An History of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie, Volume 1'' identifies Mocodome as present-day "Country Harbour". The Mi'kmaq claimed the British schooner was accidentally shipwrecked and some of the crew drowned. They also indicated that two men died of illness while the other killed the six Mi'kmaq despite their hospitality. The ''French'' officials did not believe the Mi'kmaq account of events. The Mi'kmaq account of this attack was that the two English died of natural causes and the other two killed six of the Mi'kmaq for their scalps.

Attack at Jeddore

In response, on the night of 21 April, under the leadership of Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope

Jean Baptiste Cope (Kopit in Mi’kmaq meaning ‘beaver’) was also known as Major Cope, a title he was probably given from the French military, the highest rank given to Mi’kmaq. Cope was the sakamaw (chief) of the Mi'kmaq people of Shubenaca ...

and the Mi'kmaq attacked another British schooner in a battle at sea off Jeddore, Nova Scotia. On board were nine British men and one Acadian (Casteel), who was the pilot. The Mi'kmaq killed and scalped the British and let the Acadian off at Port Toulouse, where the Mi'kmaq sank the schooner after looting it. In August 1752, the Mi'kmaq at Saint Peter's seized the schooners ''Friendship'' of Halifax and ''Dolphin'' of New England and took 21 prisoners who they held for ransom.

Raid on Halifax

In late September 1752, Mi'kmaq scalped a man they had caught outside the Palisade

A palisade, sometimes called a stakewall or a paling, is typically a fence or defensive wall made from iron or wooden stakes, or tree trunks, and used as a defensive structure or enclosure. Palisades can form a stockade.

Etymology

''Palisade ...

of Fort Sackville

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the French, British and U.S. forces built and occupied a number of forts at Vincennes, Indiana. These outposts commanded a strategic position on the Wabash River. The names of the installations were chan ...

. In 1753, when Lawrence became governor, the Mi'kmaq attacked again upon the sawmills near the South Blockhouse on the Northwest Arm, where they killed three British. The Mi'kmaq made three attempts to retrieve the bodies for their scalps. On the otherside of the harbour in Dartmouth, in 1753, there were reported only to be five families, all of whom refused to farm for fear of being attacked if they left the confines of the picketed fence around the village.

In May 1753, Natives scalped two British soldiers at Fort Lawrence. Throughout 1753, French authorities on Cape Breton Island were paying Mi'kmaq warriors for the scalps of the British.

Raid on Lawrencetown

In 1754, the British unilaterally established Lawrencetown. In late April 1754, Beausoleil and a large band of Mi'kmaq and Acadians left Chignecto for Lawrencetown. They arrived in mid-May and in the night open fired on the village. Beausoleil killed and scalped four British settlers and two soldiers. By August, as the raids continued, the residents and soldiers were withdrawn to Halifax. By June 1757, the settlers had to be withdrawn completely again from the settlement of Lawrencetown because the number of Native raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses.

Prominent Halifax business person

In 1754, the British unilaterally established Lawrencetown. In late April 1754, Beausoleil and a large band of Mi'kmaq and Acadians left Chignecto for Lawrencetown. They arrived in mid-May and in the night open fired on the village. Beausoleil killed and scalped four British settlers and two soldiers. By August, as the raids continued, the residents and soldiers were withdrawn to Halifax. By June 1757, the settlers had to be withdrawn completely again from the settlement of Lawrencetown because the number of Native raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses.

Prominent Halifax business person Michael Francklin

Michael Francklin or Franklin (6 December 1733 – 8 November 1782) served as Nova Scotia's Lieutenant Governor from 1766 to 1772. He is buried in the crypt of St. Paul's Church (Halifax).

Early life and immigration

Born in Poole, Engla ...

was captured by a Mi'kmaq raiding party in 1754 and held captive for three months.

French and Indian War

The final colonial war was the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

. The British conquest of Acadia happened in 1710. Over the next forty-five years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British and maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beausejour.

During the French and Indian War, the British sought to neutralize any military threat Acadians and Mi'kmaq militias posed within Nova Scotia but particularly to the northern New England border in Maine. The British wanted to prevent future attacks from the Wabanaki Confederacy, French and Acadians on the northern New England border. (There was a long history of these attacks from Acadia—see the Northeast Coast Campaigns 1688

Events

January–March

* January 2 – Fleeing from the Spanish Navy, French pirate Raveneau de Lussan and his 70 men arrive on the west coast of Nicaragua, sink their boats, and make a difficult 10 day march to the city of O ...

, 1703

In the Swedish calendar it was a common year starting on Thursday, one day ahead of the Julian and ten days behind the Gregorian calendar.

Events

January–March

* January 9 – The Jamaican town of Port Royal, a center of trade ...

, 1723

Events

January–March

* January 25 – British pirate Edward Low intercepts the Portuguese ship ''Nostra Signiora de Victoria''. After the Portuguese captain throws his treasure of 11,000 gold coins into the sea rather than s ...

, 1724, 1745

Events

January–March

* January 7 – War of the Austrian Succession: The Austrian Army, under the command of Field Marshal Károly József Batthyány, makes a surprise attack at Amberg and the winter quarters of the Bavari ...

, 1746

Events

January–March

* January 8 – The Young Pretender Charles Edward Stuart occupies Stirling, Scotland.

* January 17 – Battle of Falkirk Muir: British Government forces are defeated by Jacobite forces.

* February ...

, 1747

Events

January–March

* January 31 – The first venereal diseases clinic opens at London Lock Hospital.

* February 11 – King George's War: A combined French and Indian force, commanded by Captain Nicolas Antoine I ...

.total war

Total war is a type of warfare that includes any and all civilian-associated resources and infrastructure as legitimate military targets, mobilizes all of the resources of society to fight the war, and gives priority to warfare over non-com ...

; British civilians had not been spared and, as Governor Charles Lawrence and the Nova Scotia Council

Formally known as "His Majesty's Council of Nova Scotia", the Nova Scotia Council (1720–1838) was the original British administrative, legislative and judicial body in Nova Scotia. The Nova Scotia Council was also known as the Annapolis Counci ...

saw it, Acadian civilians had provided intelligence, sanctuary, and logistical support while others had fought against the British.

Within Acadia, the British also wanted to interrupt the vital supply lines Acadians provided to Louisbourg by deporting Acadians from Acadia. Defeating Louisbourg, would also mean defeating the ally which provided the Mi'kmaq ammunition to fight.

The British began the Expulsion of the Acadians

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian peo ...

with the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755)

The Bay of Fundy campaign occurred during the French and Indian War (the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War) when the British ordered the Expulsion of the Acadians from Acadia after the Battle of Fort Beauséjour (1755). The campaign ...

. Over the next nine years over 12,000 Acadians were removed from Nova Scotia. The Acadians were scattered across the Atlantic, in the Thirteen Colonies, Louisiana, Quebec, Britain, and France. Very few eventually returned to Nova Scotia. During the various campaigns of the expulsion, the Acadian and Native resistance to the British intensified.

During the expulsion, French Officer Charles Deschamps de Boishébert

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was "f ...

led the Mi'kmaq and the Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

in a guerrilla war

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics ...

against the British. According to Louisbourg account books, by late 1756, the French had regularly dispensed supplies to 700 Natives. From 1756 to the fall of Louisbourg in 1758, the French made regular payments to Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope

Jean Baptiste Cope (Kopit in Mi’kmaq meaning ‘beaver’) was also known as Major Cope, a title he was probably given from the French military, the highest rank given to Mi’kmaq. Cope was the sakamaw (chief) of the Mi'kmaq people of Shubenaca ...

and other natives for British scalps.

Raids on Annapolis (Fort Anne)

The Acadians and Mi'kmaq fought in the Annapolis region. They were victorious in the Battle of Bloody Creek. Acadians being deported from Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia

Annapolis Royal, formerly known as Port Royal, is a town located in the western part of Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Today's Annapolis Royal is the second French settlement known by the same name and should not be confused with the ne ...

on the ship ''Pembroke'' rebelled against the British crew. After fighting off an attack by another British vessel on 9 February 1756, the Acadians took 8 British prisoners to Quebec.

In December 1757, while cutting firewood near Fort Anne, the Mi'kmaq warriors captured John Weatherspoon and carried him away to the mouth of the Miramichi River. From there he was eventually sold or traded to the French and taken to Quebec, where he was held until late in 1759 and the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, when General Wolfe's forces prevailed.

About 50 or 60 Acadians who escaped the initial deportation are reported to have made their way to the Cape Sable

Cape Sable is the southernmost point of the United States mainland and mainland Florida. It is located in southwestern Florida, in Monroe County, and is part of the Everglades National Park.

The cape is a peninsula issuing from the southeast ...

region (which included south western Nova Scotia). From there, they participated in numerous raids on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia

Lunenburg is a port town on the South Shore of Nova Scotia, Canada. Founded in 1753, the town was one of the first British attempts to settle Protestants in Nova Scotia.

The economy was traditionally based on the offshore fishery and today ...

.

Oral history indicates that a Samuel Rogers led a massacre against a Mi'kmaq village at Rogers Point (present-day Point Prim), Digby in the autumn of 1759. Daniel Paul (2006) and Jon Tattrie (2013) have repeated the account as historical fact. Paul has described it as the "Last overt act of genocide committed by the English against Nova Scotia's Mi'kmaq".

The story is said to have originated from someone who participated in the raid under the leadership of Samuel Rogers. The oral history indicates that Rogers was an active member of the famous Rogers' Rangers

Rogers' Rangers was a company of soldiers from the Province of New Hampshire raised by Major Robert Rogers and attached to the British Army during the Seven Years' War ( French and Indian War). The unit was quickly adopted into the British arm ...

and of equal stature to George Scott. This Samuel Rogers is also said to be the same one who was later a member of the House of Assembly of Nova Scotia for Sackville (present-day Sackville, New Brunswick).

These descriptions of Samuel Rogers leave the credibility of the story in serious doubt. Samuel Rogers and this expedition could not have been related to Rogers' Rangers because there were no Rogers' Rangers in Nova Scotia in the autumn of 1759. There were only four companies of Rogers' Rangers to ever fight in the colony and they departed on 6 June 1759 and were never in the western region of the colony. As well, had there been a military officer of equal stature to George Scott in the colony, certainly there would be official records that support his existence, when there is not.

The Samuel Rogers of the oral tradition could not be the same Samuel Rogers who was later a member of the House of Assembly in 1775 (who was famous for becoming a leader in the siege of Fort Cumberland). This Samuel Rogers was never connected to Rogers' Rangers and he died in 1831. Had he lived until he was age 90, he would have only been age 18 when he reached George Scott's stature and led the charge on the village.

Raids on Piziquid (Fort Edward)

In the April 1757, a band of Acadian and Mi'kmaq raided a warehouse near Fort Edward, killing thirteen British soldiers. After loading with what provisions they could carry, they set fire to the building. A few days later, the same partisans also raided Fort Cumberland

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere' ...

. Because of the strength of the Acadian militia

The military history of the Acadians consisted primarily of militias made up of Acadian settlers who participated in wars against the English (the British after 1707) in coordination with the Wabanaki Confederacy (particularly the Mi'kmaw mili ...

and Mi'kmaq militia, British officer John Knox

John Knox ( gd, Iain Cnocc) (born – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgat ...

wrote that "In the year 1757 we were said to be Masters of the province of Nova Scotia, or Acadia, which, however, was only an imaginary possession … " He continues to state that the situation in the province was so precarious for the British that the "troops and inhabitants" at Fort Edward, Fort Sackville

During the 18th and early 19th centuries, the French, British and U.S. forces built and occupied a number of forts at Vincennes, Indiana. These outposts commanded a strategic position on the Wabash River. The names of the installations were chan ...

and Lunenburg "could not be reputed in any other light than as prisoners."

Raids on Chignecto (Fort Cumberland)

The Acadians and Mi'kmaq also resisted in the Chignecto region. They were victorious in the Battle of Petitcodiac (1755). In the spring of 1756, a wood-gathering party from Fort Monckton (former

The Acadians and Mi'kmaq also resisted in the Chignecto region. They were victorious in the Battle of Petitcodiac (1755). In the spring of 1756, a wood-gathering party from Fort Monckton (former Fort Gaspareaux

Fort Gaspareaux (later Fort Monckton) was a French fort at the head of Baie Verte near the mouth of the Gaspareaux River and just southeast of the modern village of Port Elgin, New Brunswick, Canada, on the Isthmus of Chignecto. It was built durin ...

), was ambushed and nine were scalped. In the April 1757, after raiding Fort Edward, the same band of Acadian and Mi'kmaq partisans raided Fort Cumberland, killing and scalping two men and taking two prisoners. On 20 July 1757, Mi'kmaq killed 23 and captured two of Gorham's rangers outside Fort Cumberland near present-day Jolicure, New Brunswick.

Raids on Lawrencetown

By June 1757, the settlers had to be withdrawn completely from the settlement of Lawrencetown (established 1754) because the number of Indian raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses. On 30 July 1757, Mi'kmaq fighters killed three Roger's Rangers at Lawrencetown.

In nearby

By June 1757, the settlers had to be withdrawn completely from the settlement of Lawrencetown (established 1754) because the number of Indian raids eventually prevented settlers from leaving their houses. On 30 July 1757, Mi'kmaq fighters killed three Roger's Rangers at Lawrencetown.

In nearby Dartmouth, Nova Scotia

Dartmouth ( ) is an urban community and former city located in the Halifax, Nova Scotia, Halifax Regional Municipality of Nova Scotia, Canada. Dartmouth is located on the eastern shore of Halifax Harbour. Dartmouth has been nicknamed the City of ...

, in the spring of 1759, there was another Mi'kmaq attack on Eastern Battery, in which five soldiers were killed.

Raids on Maine

In present-day Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and nor ...

, the Mi'kmaq and the Maliseet raided numerous New England villages. At the end of April 1755, they raided Gorham, Maine

Gorham is a town in Cumberland County, Maine, United States. The population was 18,336 at the 2020 United States Census. In addition to its urban village center known as Gorham Village or simply "the Village," the town encompasses a number of ...

, killing two men and a family. Next they appeared in New Boston (Gray

Grey (more common in British English) or gray (more common in American English) is an intermediate color between black and white. It is a neutral or achromatic color, meaning literally that it is "without color", because it can be compose ...

) and through the neighbouring towns destroying the plantations. On 13 May, they raided Frankfort (Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label= Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth ...

), where two men were killed and a house burned. The same day they raided Sheepscot (Newcastle), and took five prisoners. Two were killed in North Yarmouth on May 29 and one taken captive. They shot one person at Teconnet. They took prisoners at Fort Halifax; two prisoners taken at Fort Shirley (Dresden). They took two captive at New Gloucester as they worked on the local fort.

On 13 August 1758, Boishebert left Miramichi, New Brunswick

Miramichi () is the largest city in northern New Brunswick, Canada. It is situated at the mouth of the Miramichi River where it enters Miramichi Bay. The Miramichi Valley is the second longest valley in New Brunswick, after the Saint John Rive ...

with 400 soldiers, including Acadians which he led from Port Toulouse. They marched to Fort St George (Thomaston, Maine

Thomaston (formerly known as Fort St. Georges, Fort Wharf, Lincoln) is a town in Knox County, Maine, United States. The population was 2,739 at the 2020 census. Noted for its antique architecture, Thomaston is an old port popular with touris ...

) and Munduncook ( Friendship, Maine). While the former siege was unsuccessful, in the latter raid on Munduncook, they wounded eight British settlers and killed others. This was Boishébert's last Acadian expedition. From there, Boishebert and the Acadians went to Quebec and fought in the Battle of Quebec (1759)

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

.

Raids on Lunenburg

The Acadians and Mi'kmaq raided the Lunenburg settlement nine times over a three-year period during the war. Boishebert ordered the first Raid on Lunenburg. In response to the raid, a week later, on 14 May 1756, Governor of Nova Scotia Charles Lawrence put a bounty on Mi'kmaq scalps. Following the raid of 1756, in 1757, there was a raid on Lunenburg in which six people from the Brissang family were killed. The following year, the Lunenburg Campaign (1758) began with a raid on the Lunenburg Peninsula at the Northwest Range (present-day Blockhouse, Nova Scotia) when five people were killed from the Ochs and Roder families. By the end of May 1758, most of those on the Lunenburg Peninsula abandoned their farms and retreated to the protection of the fortifications around the town of Lunenburg, losing the season for sowing their grain. For those that did not leave their farms for the town, the number of raids intensified.

The Acadians and Mi'kmaq raided the Lunenburg settlement nine times over a three-year period during the war. Boishebert ordered the first Raid on Lunenburg. In response to the raid, a week later, on 14 May 1756, Governor of Nova Scotia Charles Lawrence put a bounty on Mi'kmaq scalps. Following the raid of 1756, in 1757, there was a raid on Lunenburg in which six people from the Brissang family were killed. The following year, the Lunenburg Campaign (1758) began with a raid on the Lunenburg Peninsula at the Northwest Range (present-day Blockhouse, Nova Scotia) when five people were killed from the Ochs and Roder families. By the end of May 1758, most of those on the Lunenburg Peninsula abandoned their farms and retreated to the protection of the fortifications around the town of Lunenburg, losing the season for sowing their grain. For those that did not leave their farms for the town, the number of raids intensified.

During the summer of 1758, there were four raids on the Lunenburg Peninsula. On 13 July 1758, one person on the

During the summer of 1758, there were four raids on the Lunenburg Peninsula. On 13 July 1758, one person on the LaHave River

The LaHave River is a river in Nova Scotia, Canada, running from its source in Annapolis County to the Atlantic Ocean. at Dayspring was killed and another seriously wounded by a member of the Labrador family. The next raid happened at Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia

Mahone Bay is a town on the northwest shore of Mahone Bay along the South Shore of Nova Scotia in Lunenburg County. A long-standing picturesque tourism destination, the town has recently enjoyed a growing reputation as a haven for entrepreneur ...

on 24 August 1758, when eight Mi'kmaq attacked the family homes of Lay and Brant. While they killed three people in the raid, the Mi'kmaq were unsuccessful in taking their scalps, which was the common practice for payment from the French. Two days, later, two soldiers were killed in a raid on the blockhouse at LaHave, Nova Scotia. Almost two weeks later, on 11 September, a child was killed in a raid on the Northwest Range. Another raid happened on 27 March 1759, in which three members of the Oxner family were killed. The last raid happened on 20 April 1759. The Mi'kmaq killed four settlers at Lunenburg who were members of the Trippeau and Crighton families.

Raids on Halifax

On 2 April 1756, Mi'kmaq received payment from the Governor of Quebec for 12 British scalps taken at Halifax. Acadian Pierre Gautier, son of Joseph-Nicolas Gautier

Joseph-Nicolas Gautier dit Bellair (1689-1752) was one of the wealthiest Acadian as a merchant trader and a leader of the Acadian militia. He participated in war efforts against the British during King George's War and Father Le Loutre’s War. I ...

, led Mi'kmaq warriors from Louisbourg on three raids against Halifax in 1757. In each raid, Gautier took prisoners or scalps or both. The last raid happened in September and Gautier went with four Mi'kmaq and killed and scalped two British men at the foot of Citadel Hill. (Pierre went on to participate in the Battle of Restigouche