Magnus Hirschfeld on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a

Magnus Hirschfeld found a balance between practicing medicine and writing about his findings. Between 1 May–15 October 1896, the ''Große Berliner Gewerbeausstellung'' ("Great Industrial Exhibition of Berlin") took place, which featured nine "

Magnus Hirschfeld found a balance between practicing medicine and writing about his findings. Between 1 May–15 October 1896, the ''Große Berliner Gewerbeausstellung'' ("Great Industrial Exhibition of Berlin") took place, which featured nine "

At the same time, Hirschfeld became involved in a debate with a number of anthropologists about the supposed existence of the ''Hottentottenschürze'' ("Hottentot apron"), namely the belief that the Khoekoe (known to Westerners as Hottentots) women of southern Africa had abnormally enlarged

At the same time, Hirschfeld became involved in a debate with a number of anthropologists about the supposed existence of the ''Hottentottenschürze'' ("Hottentot apron"), namely the belief that the Khoekoe (known to Westerners as Hottentots) women of southern Africa had abnormally enlarged

Under the more

Under the more

At least part of the reason for his "straight turn" was financial; a Dutch firm had been marketing Titus Pearls (''Titus-Perlen'') pills, which were presented in Europe as a cure for "scattered nerves" and in the United States as an

At least part of the reason for his "straight turn" was financial; a Dutch firm had been marketing Titus Pearls (''Titus-Perlen'') pills, which were presented in Europe as a cure for "scattered nerves" and in the United States as an

On 20 July 1932, the Chancellor Franz von Papen carried out a coup that deposed the Braun government in Prussia, and appointed himself the ''Reich'' commissioner for the state. A conservative Catholic who had long been a vocal critic of homosexuality, Papen ordered the Prussian police to start enforcing Paragraph 175 and to crack down in general on "sexual immorality" in Prussia. The

On 20 July 1932, the Chancellor Franz von Papen carried out a coup that deposed the Braun government in Prussia, and appointed himself the ''Reich'' commissioner for the state. A conservative Catholic who had long been a vocal critic of homosexuality, Papen ordered the Prussian police to start enforcing Paragraph 175 and to crack down in general on "sexual immorality" in Prussia. The

On his 67th birthday, 14 May 1935, Hirschfeld died of a heart attack in his apartment at the Gloria Mansions I building at 63

On his 67th birthday, 14 May 1935, Hirschfeld died of a heart attack in his apartment at the Gloria Mansions I building at 63  On 14 May 2010, to mark the 75th anniversary of Hirschfeld's death, a French national organization, the Mémorial de la Déportation Homosexuelle (MDH), in partnership with the new LGBT Community Center of Nice (Centre LGBT Côte d'Azur), organized a formal delegation to the cemetery. Speakers recalled Hirschfeld's life and work and laid a large bouquet of pink flowers on his tomb; the ribbon on the bouquet was inscribed ''"Au pionnier de nos causes. Le MDH et le Centre LGBT"'' ("To the pioneer of our causes. The MDH and the LGBT Center").

On 14 May 2010, to mark the 75th anniversary of Hirschfeld's death, a French national organization, the Mémorial de la Déportation Homosexuelle (MDH), in partnership with the new LGBT Community Center of Nice (Centre LGBT Côte d'Azur), organized a formal delegation to the cemetery. Speakers recalled Hirschfeld's life and work and laid a large bouquet of pink flowers on his tomb; the ribbon on the bouquet was inscribed ''"Au pionnier de nos causes. Le MDH et le Centre LGBT"'' ("To the pioneer of our causes. The MDH and the LGBT Center").

"Short information about the society"

Magnus Hirschfeld Society website; retrieved 2011-29-10. Since the late 20th century, researchers associated with the Magnus Hirschfeld Society have succeeded in tracking down previously dispersed and lost records and artifacts of Hirschfeld's life and work. They have brought together many of these materials at the society's archives in Berlin. At an exhibition at the

File:Tomb of Magnus Hirschfeld, Caucade Cemetery (Nice, France).jpg, Hirschfeld's tomb in the Caucade Cemetery in Nice, France, photographed the day before the 75th anniversary of his death

File:Magnus Hirschfeld.jpg, Bust of Magnus Hirschfeld in the

* ''

* ''

Hirschfeld's works are listed in the following bibliography, which is extensive but not comprehensive:

* Steakley, James D. ''The Writings of Magnus Hirschfeld: A Bibliography''. Toronto: Canadian Gay Archives, 1985.

The following have been translated into English:

* ''Urnish People: Causes and Nature of Uranism.'' Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1903; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2022).

* ''What Unites and Divides the Human Race?'' Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1919; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2020).

* ''Why Do Nations Hate Us? A Reflection on the Psychology of War.'' Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1915; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2020).

* ''Memoir: Celebrating 25 Years of the First LGBT Organization (1897-1923)''. Translation of ''Von Einst bis Jetzt'' by M. Lombardi-Nash (1923; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2019).

* ''Paragraph 175 of the Imperial Penal Code Book: The Homosexual Question Judged by Contemporaries''. Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1898; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2020).

* ''My Trial for Obscenity''. Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash. (1904; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2021).

* ''Annual Reports of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (1900-1903): The World's First Successful LGBT Organization''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1901-1903; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2021).

* ''Annual Reports of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (1904-1905): The World's First Successful LGBT Organization''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1905; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2022).

* ''Sappho and Socrates: How Does One Explain the Love of Men and Women to Persons of Their Own Sex?'' Translated by Michael Lombardi-Nash. (1896; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2019).

* ''Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1910; Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1991).

* With Max Tilke, ''The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress: Illustrated Part: Supplement to Transvestites''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1912; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts 2022).

* ''The Homosexuality of Men and Women''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash. 2nd ed. (1920; Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2000).

* ''The Sexual History of the World War'' (1930), New York City, Panurge Press, 1934; significantly abridged translation and adaptation of the original German edition: ''Sittengeschichte des Weltkrieges'', 2 vols., Verlag für Sexualwissenschaft, Schneider & Co., Leipzig & Vienna, 1930. The plates from the German edition are not included in the Panurge Press translation, but a small sampling appear in a separately issued portfolio, ''Illustrated Supplement to The Sexual History of the World War'', New York City, Panurge Press, n.d.

* ''Men and Women: The World Journey of a Sexologist'' (1933); translated by O. P. Green (New York City: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1935).

* ''Sex in Human Relationships,'' London, John Lane The Bodley Head, 1935; translated from the French volume ''L'Ame et l'amour, psychologie sexologique'' (Paris: Gallimard, 1935) by John Rodker.

* ''Racism'' (1938), translated by Eden and Cedar Paul. This denunciation of racial discrimination was not influential at the time, although it seems prophetic in retrospect.

Hirschfeld's works are listed in the following bibliography, which is extensive but not comprehensive:

* Steakley, James D. ''The Writings of Magnus Hirschfeld: A Bibliography''. Toronto: Canadian Gay Archives, 1985.

The following have been translated into English:

* ''Urnish People: Causes and Nature of Uranism.'' Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1903; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2022).

* ''What Unites and Divides the Human Race?'' Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1919; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2020).

* ''Why Do Nations Hate Us? A Reflection on the Psychology of War.'' Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1915; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2020).

* ''Memoir: Celebrating 25 Years of the First LGBT Organization (1897-1923)''. Translation of ''Von Einst bis Jetzt'' by M. Lombardi-Nash (1923; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2019).

* ''Paragraph 175 of the Imperial Penal Code Book: The Homosexual Question Judged by Contemporaries''. Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash (1898; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2020).

* ''My Trial for Obscenity''. Translated by M. Lombardi-Nash. (1904; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2021).

* ''Annual Reports of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (1900-1903): The World's First Successful LGBT Organization''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1901-1903; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2021).

* ''Annual Reports of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (1904-1905): The World's First Successful LGBT Organization''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1905; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2022).

* ''Sappho and Socrates: How Does One Explain the Love of Men and Women to Persons of Their Own Sex?'' Translated by Michael Lombardi-Nash. (1896; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts, 2019).

* ''Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1910; Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1991).

* With Max Tilke, ''The Erotic Drive to Cross-Dress: Illustrated Part: Supplement to Transvestites''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash (1912; Jacksonville, FL: Urania Manuscripts 2022).

* ''The Homosexuality of Men and Women''. Translated by Michael A. Lombardi-Nash. 2nd ed. (1920; Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2000).

* ''The Sexual History of the World War'' (1930), New York City, Panurge Press, 1934; significantly abridged translation and adaptation of the original German edition: ''Sittengeschichte des Weltkrieges'', 2 vols., Verlag für Sexualwissenschaft, Schneider & Co., Leipzig & Vienna, 1930. The plates from the German edition are not included in the Panurge Press translation, but a small sampling appear in a separately issued portfolio, ''Illustrated Supplement to The Sexual History of the World War'', New York City, Panurge Press, n.d.

* ''Men and Women: The World Journey of a Sexologist'' (1933); translated by O. P. Green (New York City: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1935).

* ''Sex in Human Relationships,'' London, John Lane The Bodley Head, 1935; translated from the French volume ''L'Ame et l'amour, psychologie sexologique'' (Paris: Gallimard, 1935) by John Rodker.

* ''Racism'' (1938), translated by Eden and Cedar Paul. This denunciation of racial discrimination was not influential at the time, although it seems prophetic in retrospect.

online

* * Domeier, Norman: "Magnus Hirschfeld", in: 1914–1918 online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2016-04-07. . * Dose, Ralf. ''Magnus Hirschfeld: Deutscher, Jude, Weltbürger''. Teetz: Hentrich und Hentrich, 2005. * Dose, Ralf. ''Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement''. New York City: Monthly Review Press, 2014; revised and expanded edition of Dose's 2005 German-language biography. * Herzer, Manfred. ''Magnus Hirschfeld: Leben und Werk eines jüdischen, schwulen und sozialistischen Sexologen''. 2nd edition. Hamburg: Männerschwarm, 2001. * Koskovich, Gérard (ed.).

Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935). Un pionnier du mouvement homosexuel confronté au nazisme

'' Paris: Mémorial de la Déportation Homosexuelle, 2010. * Kotowski, Elke-Vera & Julius H. Schoeps (eds.). ''Der Sexualreformer Magnus Hirschfeld. Ein Leben im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft, Politik und Gesellschaft''. Berlin: Bebra, 2004. * Leng, Kirsten. "Magnus Hirschfeld’s Meanings: Analysing Biography and the Politics of Representation." ''German History'' 35.1 (2017): 96–116. * Mancini, Elena. ''Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom: A History of the First International Sexual Freedom Movement.'' New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010. * Steakley, James. "Per scientiam ad justitiam: Magnus Hirschfeld and the Sexual Politics of Innate Homosexuality", in ''Science and Homosexualities'', ed. Vernon A. Rosario. New York: Routledge, 1997, pp. 133–54. * Wolff, Charlotte. ''Magnus Hirschfeld: A Portrait of a Pioneer in Sexology''. London: Quartet, 1986.

Projecting Fears and Hopes

Gay Rights on the German Screen after World War I", Blog of the ''Journal of the History of Ideas'', 28 May 2019. * Gordon, Mel. ''Voluptuous Panic: The Erotic World of Weimar Berlin''. Los Angeles: Feral House, 2000. * Grau, Günter (ed.) ''Hidden

review by Dirk Naguschewski in HSozKult

2008)

Biography

on the web site of the Bundesstiftung Magnus Hirschfeld (Magnus Hirschfeld National Foundation), Berlin

Magnus Hirschfeld – Leben und Werk

Biographical information on the web site of the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft (Magnus Hirschfeld Society), Berlin * Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hirschfeld, Magnus 1868 births 1935 deaths 19th-century LGBT people 20th-century LGBT people Abortion-rights activists Feminist writers Gay feminists Gay scientists German anti-capitalists German anti-fascists German expatriates in the United States German gay writers German sexologists German socialist feminists German socialists Jewish anti-fascists Jewish emigrants from Nazi Germany to France Jewish feminists Jewish German scientists Jewish German writers Jewish physicians Jewish socialists LGBT academics LGBT feminists LGBT Jews LGBT physicians LGBT rights activists from Germany LGBT scientists from Germany LGBT writers from Germany Male feminists Medical writers on LGBT topics People from Kołobrzeg People from the Province of Pomerania Sex educators Sex-positive feminists Transfeminists Transgender rights activists Transgender studies academics

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

physician and sexologist

Sexology is the scientific study of human sexuality, including human sexual interests, behaviors, and functions. The term ''sexology'' does not generally refer to the non-scientific study of sexuality, such as social criticism.

Sexologists a ...

.

Hirschfeld was educated in philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. ...

, philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pr ...

. An outspoken advocate for sexual minorities

A sexual minority is a group whose sexual identity, sexual orientation, orientation or practices differ from the majority of the surrounding society. Primarily used to refer to lesbian, gay, bisexual, or non-heterosexual individuals, it can al ...

, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (, WhK) was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin in May 1897, to campaign for social recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and against their legal persecution. It was the fir ...

and World League for Sexual Reform

The World League for Sexual Reform was a League for coordinating policy reforms related to greater openness around sex. The initial groundwork for the organisation, including a congress in Berlin which was later counted as the organisation's first ...

. He based his practice in Berlin-Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Prussia, it is best known for Charlottenburg Palace, the ...

during the Weimar period

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is als ...

. Historian Dustin Goltz characterized the committee as having carried out "the first advocacy for homosexual and transgender rights".Goltz, Dustin (2008). "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Movements", In Lind, Amy; Brzuzy, Stephanie (eds.). ''Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality: Volume 2'', pp. 291 ff. Greenwood Publishing Group, He is regarded as one of the most influential sexologists of the twentieth century.

Hirschfeld was targeted by Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in N ...

for being Jewish and gay; he was beaten by '' völkisch'' activists in 1920, and in 1933 his ''Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

The was an early private sexology research institute in Germany from 1919 to 1933. The name is variously translated as ''Institute of Sex Research'', ''Institute of Sexology'', ''Institute for Sexology'' or ''Institute for the Science of Sexua ...

'' was sacked and had its books burned by Nazis. He was forced into exile in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, where he died in 1935

Events

January

* January 7 – Italian premier Benito Mussolini and French Foreign Minister Pierre Laval conclude an agreement, in which each power agrees not to oppose the other's colonial claims.

* January 12 – Amelia Earhart ...

.

Early life

Hirschfeld was born in Kolberg inPomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

(Kołobrzeg

Kołobrzeg ( ; csb, Kòlbrzég; german: Kolberg, ), ; csb, Kòlbrzég , is a port city in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship in north-western Poland with about 47,000 inhabitants (). Kołobrzeg is located on the Parsęta River on the south coast ...

, Poland since 1945), in an Ashkenazi Jewish

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

family, the son of highly regarded physician and Senior Medical Officer Hermann Hirschfeld. As a youth he attended Kolberg Cathedral School, which at the time was a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

school. In 1887–1888, he studied philosophy and philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defined as ...

in Breslau, and then from 1888 to 1892 medicine in Straßburg, Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and ...

, Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German: ') is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914, of which roughly a quarter consisted of students ...

, and Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitu ...

. In 1892, he earned his medical degree.

After his studies, he traveled through the United States for eight months, visiting the World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, hel ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, and living from the proceeds of his writing for German journals. During his time in Chicago, Hirschfeld became involved with the homosexual subculture in that city. Struck by the essential similarities between the homosexual subcultures of Chicago and Berlin, Hirschfeld first developed his theory about the universality of homosexuality around the world, as he researched in books and newspaper articles about the existence of gay subcultures in Rio de Janeiro, Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the cap ...

, and Tokyo. Then he started a naturopathic

Naturopathy, or naturopathic medicine, is a form of alternative medicine. A wide array of pseudoscientific practices branded as "natural", "non-invasive", or promoting "self-healing" are employed by its practitioners, who are known as naturop ...

practice in Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

; in 1896, he moved his practice to Berlin-Charlottenburg

Charlottenburg () is a locality of Berlin within the borough of Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf. Established as a town in 1705 and named after Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Queen consort of Prussia, it is best known for Charlottenburg Palace, the ...

.

Hirschfeld became interested in gay rights because many of his gay patients took their own lives. In the German language, the word for suicide is ''Selbstmord'' ("self-murder"), which carried more judgmental and condemnatory connotations than its English language equivalent, making the subject of suicide a taboo

A taboo or tabu is a social group's ban, prohibition, or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, sacred, or allowed only for certain persons.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

in 19th century Germany.

In particular, Hirschfeld cited the story of one of his patients as a reason for his gay rights activism: a young army officer suffering from depression who killed himself in 1896, leaving behind a suicide note

A suicide note or death note is a message left behind by a person who dies or intends to die by suicide.

A study examining Japanese suicide notes estimated that 25–30% of suicides are accompanied by a note. However, incidence rates may depen ...

saying that despite his best efforts, he could not end his desires for other men, and so had ended his life out of his guilt and shame. In his suicide note, the officer wrote that he lacked the "strength" to tell his parents the "truth", and spoke of his shame of "that which nearly strangled my heart". The officer could not even bring himself to use the word "homosexuality", which he instead conspicuously referred to as "that" in his note. However, the officer mentioned at the end of his suicide note: "The thought that you irschfeldcould contribute a future when the German fatherland will think of ''us'' in more just terms sweetens the hour of my death." Hirschfeld had been treating the officer for depression in 1895–1896, and the use of the term "us" led to speculation that a relationship existed between the two. However, the officer's use of ''Sie'', the formal German word for you, instead of the informal ''Du'', suggests Hirschfeld's relationship with his patient was strictly professional.

At the same time, Hirschfeld was greatly affected by the trial of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, which he often referred to in his writings. Hirschfeld was struck by the number of his gay patients who had ''Suizidalnarben'' ("scars left by suicide attempts"), and often found himself trying to give his patients a reason to live.

Sexual rights activism

Scientific-Humanitarian Committee

Magnus Hirschfeld found a balance between practicing medicine and writing about his findings. Between 1 May–15 October 1896, the ''Große Berliner Gewerbeausstellung'' ("Great Industrial Exhibition of Berlin") took place, which featured nine "

Magnus Hirschfeld found a balance between practicing medicine and writing about his findings. Between 1 May–15 October 1896, the ''Große Berliner Gewerbeausstellung'' ("Great Industrial Exhibition of Berlin") took place, which featured nine "human zoos

Human zoos, also known as ethnological expositions, were public displays of people, usually in a so-called "natural" or "primitive" state. They were most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries. These displays sometimes emphasized the sup ...

" where people from Germany's colonies in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

and Africa were put on display for the visitors to gawk at. Such exhibitions of colonial peoples were common at industrial fairs, and later after Qingdao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means " azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

, the Mariana Islands, and the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

became part of the German empire, Chinese, Chamorros

The Chamorro people (; also CHamoru) are the indigenous people of the Mariana Islands, politically divided between the United States territory of Guam and the encompassing Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands in Micronesia. Today, signif ...

, and Micronesians joined the Africans and New Guineans displayed in the "human zoos". Hirschfeld, who was keenly interested in sexuality in other cultures, visited the ''Große Berliner Gewerbeausstellung'' and subsequently other exhibitions to inquire of the people in the "human zoos" via interpreters about the status of sexuality in their cultures. It was in 1896, after talking to the people displayed in the "human zoos" at the ''Große Berliner Gewerbeausstellung'', that Hirschfeld began writing what became his 1914 book ''Die Homosexualität des Mannes und des Weibes'' ("The Homosexuality of Men and Women"), an attempt to comprehensively survey homosexuality around the world, as part of an effort to prove that homosexuality occurred in every culture.

After several years as a general practitioner in Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebu ...

, in 1896 he issued a pamphlet, '' Sappho and Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

'', on homosexual love (under the pseudonym Th. Ramien). In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific Humanitarian Committee with the publisher Max Spohr (1850–1905), the lawyer Eduard Oberg (1858–1917), and the writer Franz Joseph von Bülow (1861–1915). The group aimed to undertake research to defend the rights of homosexuals and to repeal Paragraph 175

Paragraph 175 (known formally a§175 StGB also known as Section 175 in English) was a provision of the German Criminal Code from 15 May 1871 to 10 March 1994. It made homosexual acts between males a crime, and in early revisions the provisio ...

, the section of the German penal code that, since 1871, had criminalized homosexuality. They argued that the law encouraged blackmail. The motto of the committee, "Justice through science", reflected Hirschfeld's belief that a better scientific understanding of homosexuality would eliminate social hostility toward homosexuals.

Within the group, some of the members rejected Hirschfeld's (and Ulrichs's) view that male homosexuals are, by nature, effeminate. Benedict Friedlaender

Benedict Friedlaender (8 July 1866 – 21 June 1908; first name occasionally spelled Benedikt) was a German Jewish sexologist, sociologist, economist, volcanologist, and physicist.

Friedlaender was born in Berlin as the son of Carl Friedlae ...

and some others left the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee and formed another group, the "Bund für männliche Kultur" or Union for Male Culture, which did not exist long. It argued that male-male love is an aspect of virile manliness, rather than a special condition.

Under Hirschfeld's leadership, the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee gathered 6000 signatures from prominent Germans on a petition to overturn Paragraph 175. Signatories included Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

, Hermann Hesse

Hermann Karl Hesse (; 2 July 1877 – 9 August 1962) was a German-Swiss poet, novelist, and painter. His best-known works include ''Demian'', ''Steppenwolf (novel), Steppenwolf'', ''Siddhartha (novel), Siddhartha'', and ''The Glass Bead Game'', ...

, Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Kollwitz ( born as Schmidt; 8 July 1867 – 22 April 1945) was a German artist who worked with painting, printmaking (including etching, lithography and woodcuts) and sculpture. Her most famous art cycles, including ''The Weavers'' and ' ...

, Thomas Mann

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novella ...

, Heinrich Mann

Luiz Heinrich Mann (; 27 March 1871 – 11 March 1950), best known as simply Heinrich Mann, was a German author known for his socio-political novels. From 1930 until 1933, he was president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy ...

, Rainer Maria Rilke, August Bebel, Max Brod

Max Brod ( he, מקס ברוד; 27 May 1884 – 20 December 1968) was a German-speaking Bohemian, later Israeli, author, composer, and journalist.

Although he was a prolific writer in his own right, he is best remembered as the friend and biog ...

, Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels i ...

, Stefan Zweig, Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Johann Robert Hauptmann (; 15 November 1862 – 6 June 1946) was a German dramatist and novelist. He is counted among the most important promoters of literary naturalism, though he integrated other styles into his work as well. He rece ...

, Martin Buber

Martin Buber ( he, מרטין בובר; german: Martin Buber; yi, מארטין בובער; February 8, 1878 –

June 13, 1965) was an Austrian Jewish and Israeli philosopher best known for his philosophy of dialogue, a form of existentialism ...

, Richard von Krafft-Ebing

Richard Freiherr von Krafft-Ebing (full name Richard Fridolin Joseph Freiherr Krafft von Festenberg auf Frohnberg, genannt von Ebing; 14 August 1840 – 22 December 1902) was a German psychiatrist and author of the foundational work '' Psychopath ...

, and Eduard Bernstein.

The bill was brought before the Reichstag in 1898, but was supported only by a minority from the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been the ...

. August Bebel, a friend of Hirschfeld from his university days, agreed to sponsor the attempt to repeal Paragraph 175. Hirschfeld considered what would, in a later era, be described as " outing": forcing out of the closet

''Closeted'' and ''in the closet'' are metaphors for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender and other (LGBTQ+) people who have not disclosed their sexual orientation or gender identity and aspects thereof, including sexual identity and human ...

some of the prominent and secretly homosexual lawmakers who had remained silent on the bill. He arranged for the bill to be reintroduced and, in the 1920s, it made some progress until the takeover of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

ended all hope for any such reform.

As part of his efforts to counter popular prejudice, Hirschfeld spoke out about the taboo subject of suicide and was the first to present statistical evidence that homosexuals were more likely to commit suicide or attempt suicide than heterosexuals. Hirschfeld prepared questionnaires that gay men could answer anonymously about homosexuality and suicide. Collating his results, Hirschfeld estimated that 3 out of every 100 gays committed suicide every year, that a quarter of gays had attempted suicide at some point in their lives and that the other three-quarters had had suicidal thoughts at some point. He used his evidence to argue that, under current social conditions in Germany, life was literally unbearable for homosexuals.

A figure frequently mentioned by Hirschfeld to illustrate the "hell experienced by homosexuals" was Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, who was a well-known author in Germany, and whose trials

In law, a trial is a coming together of parties to a dispute, to present information (in the form of evidence) in a tribunal, a formal setting with the authority to adjudicate claims or disputes. One form of tribunal is a court. The tribun ...

in 1895 had been extensively covered by the German press. Hirschfeld visited Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

in 1905 to meet Wilde's son, Vyvyan Holland

Vyvyan Beresford Holland, (born Vyvyan Oscar Beresford Wilde; 3 November 1886 – 10 October 1967) was an English author and translator. He was the second-born son of Irish playwright Oscar Wilde and Constance Lloyd, and had a brother, Cyril.

...

, who had changed his surname to avoid being associated with his father. Hirschfeld noted "the name Wilde" has, since his trial, sounded like "an indecent word, which causes homosexuals to blush with shame, women to avert their eyes, and normal men to be outraged". During his visit to Britain, Hirschfeld was invited to a secret ceremony in the English countryside where a "group of beautiful, young, male students" from Cambridge gathered together wearing Wilde's prison number, C33, as a way of symbolically linking his fate to theirs, to read out aloud Wilde's poem "The Ballad of Reading Gaol

''The Ballad of Reading Gaol'' is a poem by Oscar Wilde, written in exile in Berneval-le-Grand, after his release from Reading Gaol () on 19 May 1897. Wilde had been incarcerated in Reading after being convicted of gross indecency with other m ...

". Hirschfeld found the reading of "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" to be "''markerschütternd''" (shaken to the core of one's being, i.e. something that is emotionally devastating), going on to write that the poem reading was "the most earth-shattering outcry that has ever been voiced by a downtrodden soul about its own torture and that of humanity". By the end of the reading of "The Ballad of Reading Gaol", Hirshfeld felt "quiet joy" as he was convinced that, despite the way that Wilde's life had been ruined, something good would eventually come of it.

Feminism

In 1905, Hirschfeld joined the ''Bund für Mutterschutz'' (League for the Protection of Mothers), thefeminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

organization founded by Helene Stöcker

Helene Stöcker (13 November 1869 – 24 February 1943) was a German feminist, pacifist and gender activist. She successfully campaigned keep same sex relationships between women legal, but she was unsuccessful in her campaign to legalise aborti ...

. He campaigned for the decriminalisation of abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

, and against policies that banned female teachers and civil servants from marrying or having children. Both Hirschfeld and Stöcker believed that there was a close connection between the causes of gay rights and women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

, and Stöcker was much involved in the campaign to repeal Paragraph 175 while Hirschfeld campaigned for the repeal of Paragraph 218, which had banned abortion. From 1909 to 1912, Stöcker, Hirschfeld, Hedwig Dohm

Marianne Adelaide Hedwig Dohm (née Schlesinger, later Schleh; 20 September 1831 – 1 June 1919) was a German feminist and author.

Family

She was born in the Prussian capital Berlin to assimilated Jewish parents, and her father was baptized. ...

, and others successfully campaigned against an extension to Paragraph 175 which would have criminalised female homosexuality.

In 1906, Hirschfeld was asked as a doctor to examine a prisoner in Neumünster

Neumünster () is a city in the middle of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. With more than 79,000 registered inhabitants, it is the fourth-largest municipality in Schleswig-Holstein (behind Kiel, Lübeck and Flensburg).

History

The city was fi ...

to see if he was suffering from "severe nervous disturbances caused by a combination of malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

, blackwater fever, and congenital sexual anomaly". The man, a former soldier and a veteran of what Hirschfeld called the "''Hereroaufstand''" ("Herero revolt") in German Southwest Africa

German South West Africa (german: Deutsch-Südwestafrika) was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. With a total area of ...

(modern Namibia) appeared to be suffering from what would now be considered post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that can develop because of exposure to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats on ...

, saying that he had done terrible things in Southwest Africa, and could no longer live with himself. In 1904, the Herero and Namaqua peoples who had been steadily pushed off their land to make way for German settlers, had revolted, causing Kaiser Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

to dispatch General Lothar von Trotha

General Adrian Dietrich Lothar von Trotha (3 July 1848 – 31 March 1920) was a German military commander during the European new colonial era. As a brigade commander of the East Asian Expedition Corps, he was involved in suppressing the Boxe ...

to wage a "war of annihilation" to exterminate the Herero and Namaqua in what has since become known as the Herero and Namaqua genocide

The Herero and Namaqua genocide or the Herero and Nama genocide was a campaign of ethnic extermination and collective punishment waged by the German Empire against the Herero (Ovaherero) and the Nama in German South West Africa (now Namibia). I ...

. The genocide came to widespread attention when the SPD leader August Bebel criticized the government on the floor of the ''Reichstag'', saying the government did not have the right to exterminate the Herero just because they were Black. Hirschfeld did not mention his diagnosis of the prisoner, nor he did mention in detail the source of the prisoner's guilt about his actions in Southwest Africa; the German scholar Heike Bauer criticized him for his seeming unwillingness to see the connection between the Herero genocide and the prisoner's guilt, which had caused him to engage in a petty crime wave.

Hirschfeld's position, that homosexuality was normal and natural, made him a highly controversial figure at the time, involving him in vigorous debates with other academics, who regarded homosexuality as unnatural and wrong. One of Hirschfeld's leading critics was Austrian Baron Christian von Ehrenfels

Christian von Ehrenfels (also ''Maria Christian Julius Leopold Freiherr von Ehrenfels''; 20 June 1859 – 8 September 1932) was an Austrian philosopher, and is known as one of the founders and precursors of Gestalt psychology.

Christian von Eh ...

, who advocated radical changes to society and sexuality to combat the supposed "Yellow Peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racial color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a psychocultural menace from the Eastern world ...

", and saw Hirschfeld's theories as a challenge to his view of sexuality. Ehrenfels argued that there were a few "biologically degenerate" homosexuals who lured otherwise "healthy boys" into their lifestyle, making homosexuality into a choice and a wrong one at that time.

African anthropology

At the same time, Hirschfeld became involved in a debate with a number of anthropologists about the supposed existence of the ''Hottentottenschürze'' ("Hottentot apron"), namely the belief that the Khoekoe (known to Westerners as Hottentots) women of southern Africa had abnormally enlarged

At the same time, Hirschfeld became involved in a debate with a number of anthropologists about the supposed existence of the ''Hottentottenschürze'' ("Hottentot apron"), namely the belief that the Khoekoe (known to Westerners as Hottentots) women of southern Africa had abnormally enlarged labia

The labia are part of the female genitalia; they are the major externally visible portions of the vulva. In humans, there are two pairs of labia: the ''labia majora'' (or the outer labia) are larger and thicker, while the '' labia minora'' are fo ...

, which made them inclined toward lesbianism. Hirschfeld argued there was no evidence that the Khoekoe women had abnormally large labia, whose supposed existence had fascinated so many Western anthropologists at the time, and that, other than being Black, the bodies of Khoekoe women were no different from German women. One Khoekoe woman, Sarah Baartman

Sarah Baartman (; 1789– 29 December 1815), also spelt Sara, sometimes in the diminutive form Saartje (), or Saartjie, and Bartman, Bartmann, was a Khoikhoi woman who was exhibited as a freak show attraction in 19th-century Europe under the ...

, the "Hottentot Venus", did have relatively large buttocks and labia, compared to Northern European women, and had been exhibited at a freak show in Europe in the early 19th century, which was the origin of this belief about the Khoikhoi women. Hirschfeld wrote: "The differences appear minimal compared to what is shared" between Khoekoe and German women. Turning the argument of the anthropologists on their head, Hirschfeld argued that, if same-sex relationships were common among Khoekoe women, and if the bodies of Khoekoe women were essentially the same as Western women, then Western women must have the same tendencies. Hirschfeld's theories about a spectrum of sexuality existing in all of the world's cultures implicitly undercut the binary theories about the differences between various races that was the basis of the claim of white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

. However, Bauer wrote that Hirschfeld's theories about the universality of homosexuality paid little attention to cultural contexts, and criticized him for his remarks that Hausa

Hausa may refer to:

* Hausa people, an ethnic group of West Africa

* Hausa language, spoken in West Africa

* Hausa Kingdoms, a historical collection of Hausa city-states

* Hausa (horse) or Dongola horse, an African breed of riding horse

See also

...

women in Nigeria were well known for their lesbian tendencies and would have been executed for their sapphic acts before British rule, as assuming that imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

was always good for the colonized.

Eulenburg affair

Hirschfeld played a prominent role in theHarden–Eulenburg affair

The Eulenburg affair, described as "the biggest homosexual scandal ever", was the public controversy surrounding a series of courts-martial and five civil trials regarding accusations of homosexual conduct, and accompanying libel trials, among pro ...

of 1906–09, which became the most widely publicized sex scandal in Imperial Germany

The German Empire (), Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditar ...

. During the libel trial in 1907, when General Kuno von Moltke

Lieutenant General Kuno Augustus Friedrich Karl Detlev Graf von Moltke (13 December 1847 – 19 March 1923), adjutant to Wilhelm II of Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm II and military commander of Berlin, was a principal in the homosexual scandal known as t ...

sued the journalist Maximilian Harden

__NOTOC__

Maximilian Harden (born Felix Ernst Witkowski, 20 October 1861 – 30 October 1927) was an influential German journalist and editor.

Biography

Born the son of a Jewish merchant in Berlin he attended the '' Französisches Gymnasium'' u ...

, after the latter had run an article accusing Moltke of having a homosexual relationship with the politically powerful Prince Philipp von Eulenburg, who was the Kaiser's best friend, Hirschfeld testified for Harden. In his role as an expert witness, Hirschfeld testified that Moltke was gay and, thus, what Harden had written was true.Mancini, Elena ''Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom: A History of the First International Sexual Freedom Movement'', London: Macmillan, 2010 p. 100 Hirschfeld – who wanted to make homosexuality legal in Germany – believed that proving Army officers like Moltke were gay would help his case for legalization. He also testified that he believed there was nothing wrong with Moltke.

Most notably, Hirschfeld testified that "homosexuality was part of the plan of nature and creation just like normal love." Hirschfeld's testimony caused outrage all over Germany. The ''Vossische Zeitung

The (''Voss's Newspaper'') was a nationally-known Berlin newspaper that represented the interests of the liberal middle class. It was also generally regarded as Germany's national newspaper of record. In the Berlin press it held a special role d ...

'' newspaper condemned Hirschfeld in an editorial as "a freak who acted for freaks in the name of pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or falsifiability, unfa ...

". The ''Mūnchener Neuesten Nachrichten'' newspaper declared in an editorial: "Dr. Hirschfeld makes public propaganda under the cover of science, which does nothing but poison our people. Real science should fight against this!" A notable witness at the trial was Lilly von Elbe, former wife of Moltke, who testified that her husband had only had sex with her twice in their entire marriage. Elbe spoke with remarkable openness for the period of her sexual desires and her frustration with a husband who was only interested in having sex with Eulenburg.Domeier, Norman ''The Eulenburg Affair: A Cultural History of Politics in the German Empire'', Rochester: Boydell & Brewer, 2015 pp. 103–104 Elbe's testimony was marked by moments of low comedy when it emerged that she had taken to attacking Moltke with a frying pan in vain attempts to make him have sex with her. The fact that General von Moltke was unable to defend himself from his wife's attacks was taken as proof that he was deficient in his masculinity, which many saw as confirming his homosexuality. At the time, the subject of female sexuality was taboo, and Elbe's testimony was controversial, with many saying that Elbe must be mentally ill because of her willingness to acknowledge her sexuality.Domeier, Norman ''The Eulenburg Affair: A Cultural History of Politics in the German Empire'', Rochester: Boydell & Brewer, 2015 pp. 103–105. At the time, it was generally believed that women should be "chaste" and "pure", and not have any sort of sexuality at all. Letters to the newspapers at the time, from both men and women, overwhelmingly condemned Elbe for her "disgusting" testimony concerning her sexuality. As an expert witness, Hirschfeld also testified that female sexuality was natural, and Elbe was just a normal woman who was in no way mentally ill. After the jury ruled in favor of Harden, Judge Hugo Isenbiel was enraged by the jury's decision, which he saw as expressing approval for Hirschfeld. He overturned the verdict under the grounds that homosexuals "have the morals of dogs", and insisted that this verdict could not be allowed to stand.

After the verdict was overturned, a second trial found Harden guilty of libel. At the second trial, Hirschfeld again testified as an expert witness, but this time, he was much less certain than he had been at the first trial about Moltke's homosexuality.Mancini, Elena ''Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom: A History of the First International Sexual Freedom Movement'', London: Macmillan, 2010 p. 101. Hirschfeld testified that Moltke and Eulenburg had an "intimate" friendship that was homoerotic

Homoeroticism is sexual attraction between members of the same sex, either male–male or female–female. The concept differs from the concept of homosexuality: it refers specifically to the desire itself, which can be temporary, whereas "homose ...

in nature but not sexual, as he had testified at the first trial. Hirschfeld also testified that, though he still believed female sexuality was normal, Elbe was suffering from hysteria caused by a lack of sex, and so the court should discount her stories about a sexual relationship between Moltke and Eulenburg. Hirschfeld had been threatened by the Prussian

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

government with having his medical license revoked if he testified as an expert witness again along the same lines that he had at the first trial, and possibly prosecuted for violating Paragraph 175

Paragraph 175 (known formally a§175 StGB also known as Section 175 in English) was a provision of the German Criminal Code from 15 May 1871 to 10 March 1994. It made homosexual acts between males a crime, and in early revisions the provisio ...

. The trial was a libel suit against Harden by Moltke, but much of the testimony had concerned Eulenburg, whose status as the best friend of Wilhelm II meant that the scandal threatened to involve the Kaiser. Moreover, far from precipitating increased tolerance as Hirschfeld had expected, the scandal led to a major homophobic and anti-Semitic backlash, and Hirschfeld's biographer Elena Mancini speculated that Hirschfeld wanted to bring to an end an affair that was hindering rather helping the cause for gay rights.

Because Eulenburg was a prominent anti-Semite and Hirschfeld was a Jew, during the affair, the ''völkisch'' movement came out in support of Eulenburg, whom they portrayed as an Aryan heterosexual, framed by false allegations of homosexuality by Hirschfeld and Harden.Domeier, Norman ''The Eulenburg Affair: A Cultural History of Politics in the German Empire'', Rochester: Boydell & Brewer, 2015 p. 169 Various ''völkisch'' leaders, most notably the radical anti-Semitic journalist Theodor Fritsch

Theodor Fritsch (born Emil Theodor Fritsche; 28 October 1852 – 8 September 1933), was a German publisher and journalist. His antisemitic writings did much to influence popular German opinion against Jews in the late 19th and early 20th c ...

, used the Eulenburg affair as a chance to "settle the accounts" with the Jews. As a gay Jew, Hirschfeld was relentlessly vilified by the ''völkisch'' newspapers. Outside Hirschfeld's house in Berlin, posters were affixed by ''völkisch'' activists, which read "Dr. Hirschfeld A Public Danger: The Jews are Our Undoing!". In Nazi Germany, the official interpretation of the Eulenburg affair was that Eulenburg was a straight Aryan whose career was destroyed by false claims of being gay by Jews like Hirschfeld. After the scandal had ended, Hirschfeld concluded that, far from helping the gay rights movement as he had hoped, the ensuing backlash set the movement back. The conclusion drawn by the German government was the opposite of the one that Hirschfeld wanted; the fact that prominent men like General von Moltke and Eulenburg were gay did not lead the government to repeal Paragraph 175 as Hirschfeld had hoped and, instead, the government decided that Paragraph 175 was being enforced with insufficient vigor, leading to a crackdown on homosexuals that was unprecedented and would not be exceeded until the Nazi era.

World War I

In 1914, Hirschfeld was swept up by the national enthusiasm for the ''Burgfrieden

The or 'c.fBurgfriedeat Duden online. was a German medieval term that referred to imposition of a state of truce within the jurisdiction of a castle, and sometimes its estate, under which feuds, i.e. conflicts between private individuals, were ...

'' ("Peace within a castle under siege"), as the sense of national solidarity was known where almost all Germans rallied to the Fatherland. Initially pro-war, Hirschfeld started to turn against the war in 1915, moving toward a pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

position.Mancini, Elena ''Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom: A History of the First International Sexual Freedom Movement'', London: Macmillan, 2010 p. 112 In his 1915 pamphlet, ''Warum Hassen uns die Völker?'' ("Why do other nations hate us?"), Hirschfeld answered his own question by arguing that it was the greatness of Germany that excited envy from other nations, especially Great Britain, and so had supposedly caused them to come together to destroy the ''Reich''. Hirschfeld accused Britain of starting the war in 1914 "out of envy at the development and size of the German Empire". ''Warum Hassen uns die Völker?'' was characterized by a chauvinist and ultra-nationalist

Ultranationalism or extreme nationalism is an extreme form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains detrimental hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its sp ...

tone, together with a crass Anglophobia

Anti-English sentiment or Anglophobia (from Latin ''Anglus'' "English" and Greek φόβος, ''phobos'', "fear") means opposition to, dislike of, fear of, hatred of, or the oppression and persecution of England and/or English people.''Oxford ...

that has often embarrassed Hirschfeld's modern admirers such as Charlotte Wolff

Charlotte Wolff (30 September 1897 – 12 September 1986) was a German-British physician who worked as a psychotherapist and wrote on sexology and hand analysis. Her writings on lesbianism and bisexuality were influential early works in the field ...

, who called the pamphlet a "perversion of the values which Hirschfeld had always stood for".

As a Jewish homosexual, Hirschfeld was acutely aware that many Germans did not consider him to be a "proper" German, or even a German at all; so, he reasoned that taking an ultra-patriotic stance might break down prejudices by showing that German Jews and/or homosexuals could also be good, patriotic Germans, rallying to the cry of the Fatherland. By 1916, Hirschfeld was writing pacifist pamphlets, calling for an immediate end to the war. In his 1916 pamphlet ''Kriegspsychologisches'' ("The Psychology of War"), Hirschfeld was far more critical of the war than he had been in 1915, emphasizing the suffering and trauma caused by it. He also expressed the opinion that nobody wanted to take responsibility for the war because its horrors were "superhuman in size". He declared that "it is not enough that the war ends with peace; it must end with reconciliation". In late 1918, Hirschfeld together with his sister, Franziska Mann, co-wrote a pamphlet ''Was jede Frau vom Wahlrecht wissen muß!''" ("What every woman needs to know about the right to vote!") hailing the November Revolution for granting German women the right to vote and announced the "eyes of the world are now resting on German women".

Interwar period

In 1920, Hirschfeld was badly beaten by a group of ''völkisch'' activists who attacked him on the street; he was initially declared dead when the police arrived. In 1921, Hirschfeld organised the First Congress for Sexual Reform, which led to the formation of theWorld League for Sexual Reform

The World League for Sexual Reform was a League for coordinating policy reforms related to greater openness around sex. The initial groundwork for the organisation, including a congress in Berlin which was later counted as the organisation's first ...

. Congresses were held in Copenhagen (1928), London (1929), Vienna (1930), and Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

(1932).

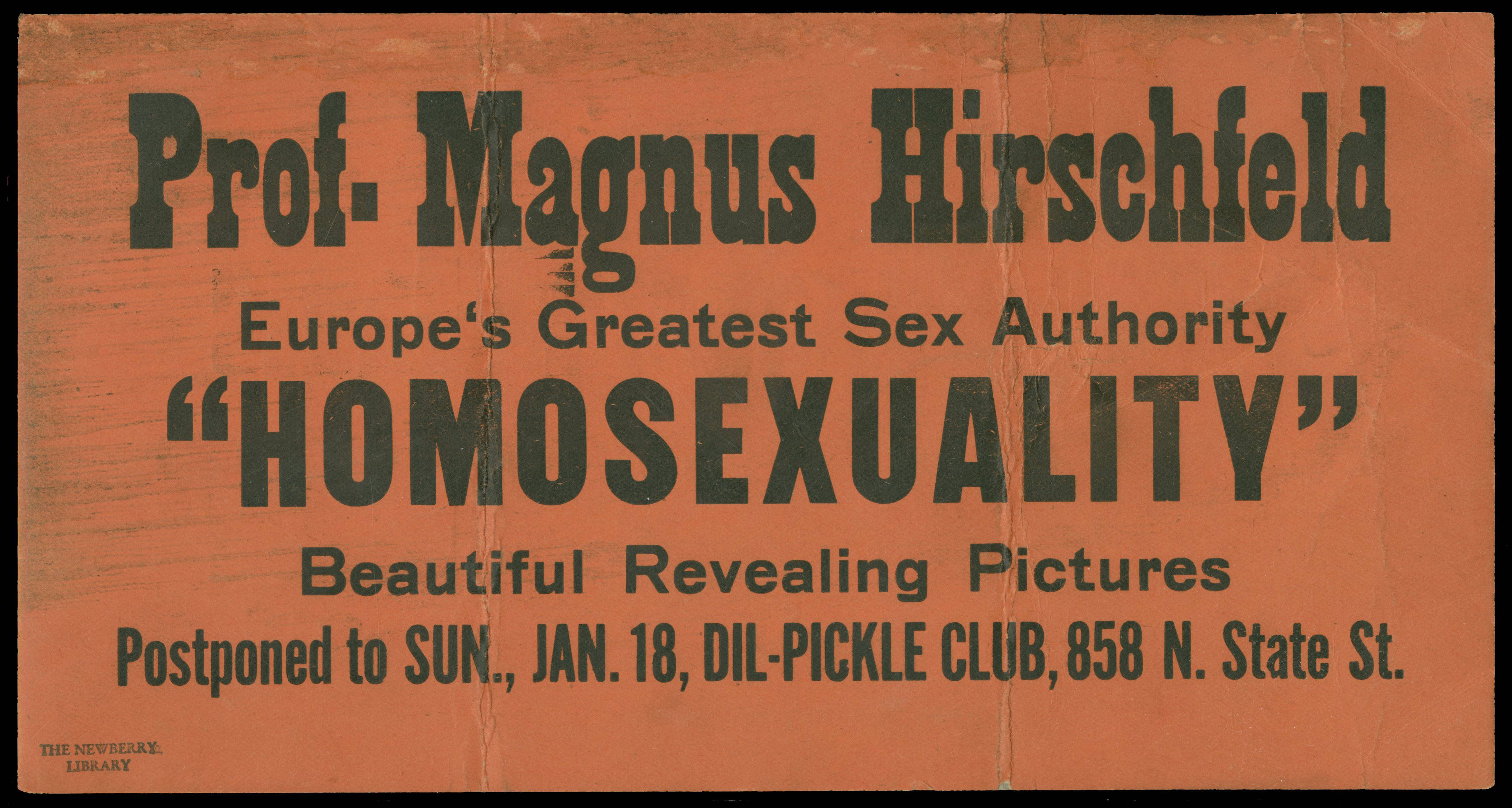

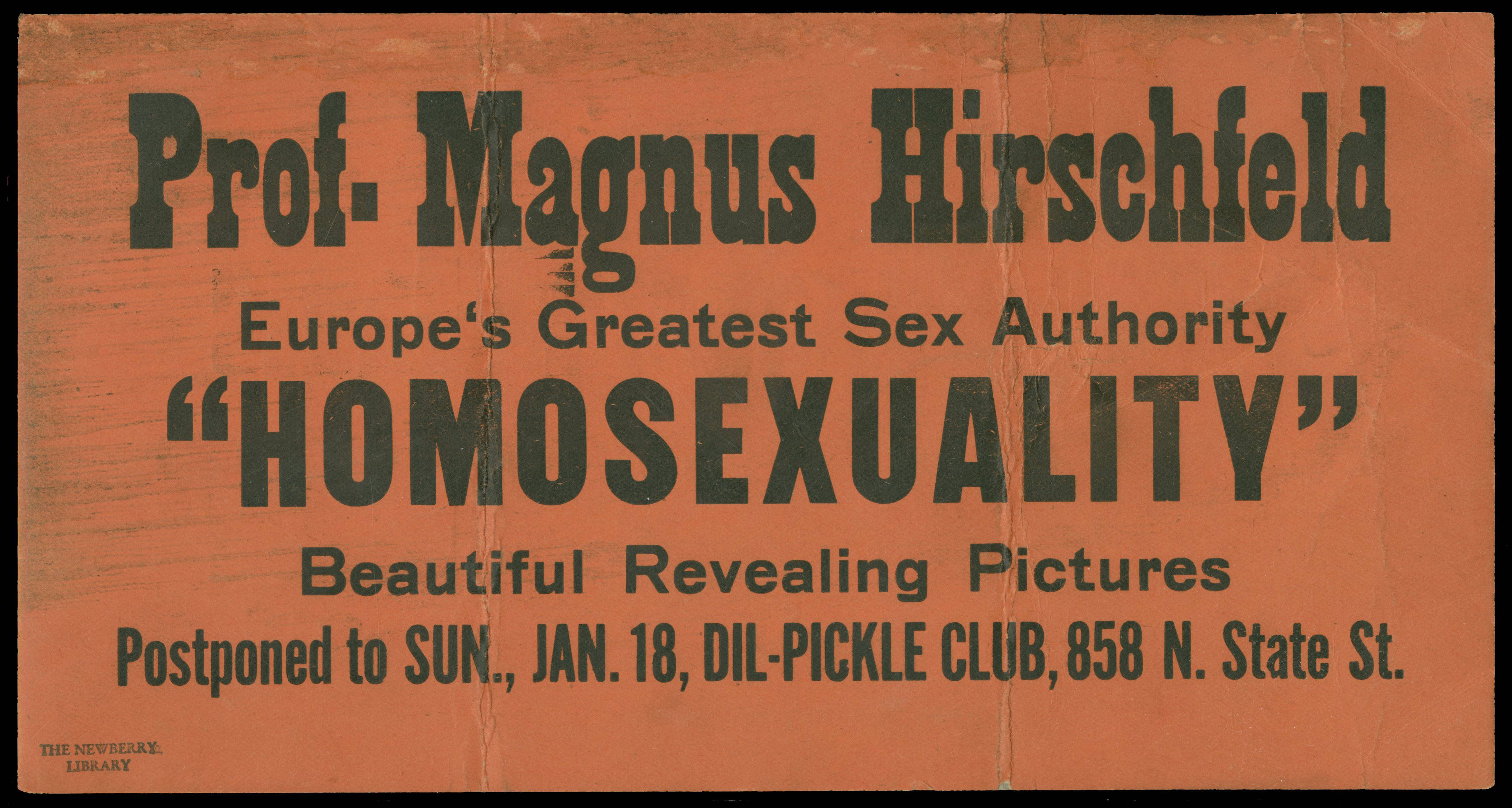

Hirschfeld was both quoted and caricatured in the press as a vociferous expert on sexual matters; during his 1931 tour of the United States, the Hearst newspaper chain dubbed him "the Einstein of Sex". He identified as a campaigner and a scientist, investigating and cataloging many varieties of sexuality, not just homosexuality. He developed a system which categorised 64 possible types of sexual intermediary, ranging from masculine, heterosexual male to feminine, homosexual male, including those he described under the term transvestite

Transvestism is the practice of dressing in a manner traditionally associated with the opposite sex. In some cultures, transvestism is practiced for religious, traditional, or ceremonial reasons. The term is considered outdated in Western ...

(Ger. ''Transvestit''), which he coined in 1910, and those he described under the term ''transsexuals'', a term he coined in 1923. He also made a distinction between ''transsexualism'' and intersex

Intersex people are individuals born with any of several sex characteristics including chromosome patterns, gonads, or genitals that, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical bin ...

uality.

At this time, Hirschfeld and the ''Institute for Sexual Sciences'' issued a number of transvestite pass

A transvestite pass (german: Transvestitenschein) was a doctor's note recognized by the governments of Imperial Germany and the Weimar Republic – under the support of sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld – identifying a person as a transvestite. ''T ...

es to trans people in order to prevent them from being harassed by the police.

''Anders als die Andern''

Hirschfeld co-wrote and acted in the 1919 film '' Anders als die Andern'' ("Different From the Others"), in whichConrad Veidt

Hans Walter Conrad Veidt (; 22 January 1893 – 3 April 1943) was a German film actor who attracted early attention for his roles in the films ''Different from the Others'' (1919), '' The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari'' (1920), and '' The Man Who Laug ...

played one of the first homosexual characters ever written for cinema. The film had a specific gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , 3 ...

law reform agenda; after Veidt's character is blackmailed by a male prostitute

Male prostitution is the act or practice of men providing sexual services in return for payment. It is a form of sex work. Although clients can be of any gender, the vast majority are older males looking to fulfill their sexual needs. Male pro ...

, he eventually comes out

Coming out of the closet, often shortened to coming out, is a metaphor used to describe LGBT people's self-disclosure of their sexual orientation, romantic orientation, or gender identity.

Framed and debated as a privacy issue, coming out of ...

rather than continuing to make the blackmail payments. His career is destroyed and he is driven to suicide.

Hirschfeld played himself in ''Anders als die Andern'', where the title cards have him say: "The persecution of homosexuals belongs to the same sad chapter of history in which the persecutions of witches and heretics is inscribed... Only with the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

did a complete change come about. Everywhere where the Code Napoléon was introduced, the laws against homosexuals were repealed, for they were considered a violation of the rights of the individual... In Germany, however, despite more than fifty years of scientific research, legal discrimination against homosexuals continues unabated... May justice soon prevail over injustice in this area, science conquer superstition, love achieve victory over hatred!"

In May 1919, when the film premiered in Berlin, the First World War was still a very fresh memory and German conservatives, who already hated Hirschfeld, seized upon his Francophile

A Francophile, also known as Gallophile, is a person who has a strong affinity towards any or all of the French language, French history, French culture and/or French people. That affinity may include France itself or its history, language, cuisin ...

speech in the film praising France for legalizing homosexuality in 1792 as evidence that gay rights were "un-German".

At the end of the film, when the protagonist Paul Körner commits suicide, his lover Kurt is planning on killing himself, when Hirschfeld appears to tell him: "If you want to honor the memory of your dead friend, you must not take your own life, but instead preserve it to change the prejudices whose victim – one of the countless many – this dead man was. That is the task of the living I assign you. Just as Zola struggled on behalf of a man who innocently languished in prison, what matters now is to restore honor and justice to the many thousands before us, with us, and after us. Through knowledge to justice!" The reference to Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, also , ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism, and an important contributor to the development of ...

's role in the Dreyfus affair

The Dreyfus affair (french: affaire Dreyfus, ) was a political scandal that divided the French Third Republic from 1894 until its resolution in 1906. "L'Affaire", as it is known in French, has come to symbolise modern injustice in the Francop ...

was intended to draw a parallel between homophobia and anti-Semitism, while Hirschfeld's repeated use of the word "us" was an implied admission of his own homosexuality.

The anti-suicide message of ''Anders als die Andern'' reflected Hirschfeld's interest in the subject of the high suicide rate among homosexuals, and was intended to give hope to gay audiences. The film ends with Hirschfeld opening a copy of the penal code of the ''Reich'' and striking out Paragraph 175 with a giant X.

''Institut für Sexualwissenschaft''

Under the more

Under the more liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

atmosphere of the newly founded Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

, Hirschfeld purchased a villa not far from the Reichstag building in Berlin for his new ''Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

The was an early private sexology research institute in Germany from 1919 to 1933. The name is variously translated as ''Institute of Sex Research'', ''Institute of Sexology'', ''Institute for Sexology'' or ''Institute for the Science of Sexua ...

'' (Institute of Sexual Research), which opened on 6 July 1919. In Germany, the ''Reich'' government made laws, but the ''Länder'' governments enforced the laws, meaning it was up to the ''Länder'' governments to enforce Paragraph 175. Until the November Revolution of 1918, Prussia had a three-class voting system that effectively disfranchised most ordinary people, and allowed the ''Junker

Junker ( da, Junker, german: Junker, nl, Jonkheer, en, Yunker, no, Junker, sv, Junker ka, იუნკერი (Iunkeri)) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German ''Juncherre'', meaning "young nobleman"Duden; Meaning of Junke ...

s'' to dominate Prussia. After the November Revolution, universal suffrage came to Prussia, which became a stronghold of the Social Democrats. The SPD believed in repealing Paragraph 175, and the Social Democratic Prussian government headed by Otto Braun

Otto Braun (28 January 1872 – 15 December 1955) was a politician of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) during the Weimar Republic. From 1920 to 1932, with only two brief interruptions, Braun was Minister President of the Free State ...

ordered the Prussian police not to enforce Paragraph 175, making Prussia into a haven for homosexuals all over Germany.

The Institute housed Hirschfeld's immense archives and library on sexuality and provided educational services and medical consultations; the clinical staff included psychiatrists Felix Abraham and Arthur Kronfeld

Arthur Kronfeld (January 9, 1886 – October 16, 1941) was a German psychiatrist of Jewish origin, and eventually a professor at the University of Berlin. His sister Maria Dronke found fame as an actor in New Zealand. Later in life, Kronfeld t ...

, gynecologist Ludwig Levy-Lenz

Ludwig Levy-Lenz (born 1 December 1892 in Posen (now Poznań), German Reich; died 30 October 1966 in Munich) was a German doctor of medicine and a sexual reformer, known for performing some of the first sex reassignment surgeries for patients of ...

, dermatologist and endocrinologist Bernhard Schapiro, and dermatologist Friedrich Wertheim.Ralf Dose, ''Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement'' (New York City: Monthly Review Press, 2014); . The institute also housed the Museum of Sex, an educational resource for the public, which is reported to have been visited by school classes. Hirschfeld himself lived at the Institution on the second floor with his partner, Karl Giese

Karl Giese (18 October 1898 – March 1938) was a German archivist, museum curator, and the life partner of Magnus Hirschfeld.

Biography

Early years

Giese was the youngest of six children of a working-class family and had three brothers and ...

, together with his sister Recha Tobias (1857–1942). Giese and Hirschfeld were a well-known couple in the gay scene in Berlin where Hirschfeld was popularly known as "Tante Magnesia". ''Tante'' ("aunt") was a German slang expression for a gay man but did not mean, as some claim, that Hirschfeld himself cross-dressed.

People from around Europe and beyond came to the institute to gain a clearer understanding of their sexuality. Christopher Isherwood writes about his and W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry was noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in ...

's visit in his book ''Christopher and His Kind

''Christopher and His Kind'' is a 1976 memoir by Anglo-American writer Christopher Isherwood, first printed in a 130-copy edition by Sylvester & Orphanos, then in general publication by Farrar, Straus & Giroux. In the text, Isherwood candidly e ...

''; they were calling on Francis Turville-Petre

Francis Adrian Joseph Turville-Petre (4 March 1901 – 16 August 1942) was a British archaeologist, famous for the discovery of the ''Homo heidelbergensis'' fossil Galilee Man in 1926, and for his work at Mount Carmel, in what was then the Briti ...

, a friend of Isherwood's who was an active member of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee. Other celebrated visitors included German novelist and playwright Gerhart Hauptmann

Gerhart Johann Robert Hauptmann (; 15 November 1862 – 6 June 1946) was a German dramatist and novelist. He is counted among the most important promoters of literary naturalism, though he integrated other styles into his work as well. He rece ...

, German artist Christian Schad

Christian Schad (21 August 189425 February 1982) was a German painter and photographer. He was associated with the Dada and the New Objectivity movements. Considered as a group, Schad's portraits form an extraordinary record of life in Vienna a ...

, French writers René Crevel

René Crevel (; 10 August 1900 – 18 June 1935) was a French writer involved with the surrealist movement.

Life

Crevel was born in Paris to a family of Parisian bourgeoisie. He had a traumatic religious upbringing. At the age of fourteen, h ...

and André Gide

André Paul Guillaume Gide (; 22 November 1869 – 19 February 1951) was a French author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature (in 1947). Gide's career ranged from its beginnings in the Symbolism (arts), symbolist movement, to the advent o ...

, Russian director Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein (russian: Сергей Михайлович Эйзенштейн, p=sʲɪrˈɡʲej mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ ɪjzʲɪnˈʂtʲejn, 2=Sergey Mikhaylovich Eyzenshteyn; 11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, scree ...

, and American poet Elsa Gidlow

Elsa Gidlow (29 December 1898 – 8 June 1986) was a British-born, Canadian-American poet, freelance journalist, philosopher and humanitarian. She is best known for writing ''On a Grey Thread'' (1923), the first volume of openly lesbian love ...

.

In addition, a number of noted individuals lived for longer or shorter periods of time in the various rooms available for rent or as free accommodations in the Institute complex. Among the residents were Isherwood and Turville-Petre; literary critic and philosopher Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin (; ; 15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940) was a German Jewish philosopher, cultural critic and essayist.

An eclectic thinker, combining elements of German idealism, Romanticism, Western Marxism, and Jewish ...

; actress and dancer Anita Berber; Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

philosopher Ernst Bloch

Ernst Simon Bloch (; July 8, 1885 – August 4, 1977; pseudonyms: Karl Jahraus, Jakob Knerz) was a German Marxist philosopher. Bloch was influenced by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx, as well as by apocalyptic and religious thinkers ...

; Willi Münzenberg

Wilhelm "Willi" Münzenberg (14 August 1889, Erfurt, Germany – June 1940, Saint-Marcellin, France) was a German Communist political activist and publisher. Münzenberg was the first head of the Young Communist International in 1919–20 and est ...

, a member of the German Parliament and a press officer for the Communist Party of Germany; Dora Richter

Dora "Dorchen" Richter (16 April 1891 – presumed 1933) was the first known person to undergo complete male-to-female gender reassignment surgery. She was one of a number of transgender people in the care of sex-research pioneer Magnus Hirschfel ...

, one of the first transgender patients to receive sex reassignment surgery

Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) is a surgical procedure, or series of procedures, that alters a transgender or transsexual person's physical appearance and sexual characteristics to resemble those associated with their identified gender, and a ...

at the institute, and Lili Elbe

Lili Ilse Elvenes (28 December 1882 – 13 September 1931), better known as Lili Elbe, was a Danish painter and transgender woman, and among the early recipients of sex reassignment surgery. She was a successful painter under her birth name Ein ...