Monaldo Leopardi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Count Monaldo Leopardi (

Monaldo Leopardi was born in Recanati on the 16th of August 1776. He lost his father before he was five years old, and spent the years of his childhood in the Palazzo Leopardi, with his mother, his brother and sister, and his great-uncle. His

Monaldo Leopardi was born in Recanati on the 16th of August 1776. He lost his father before he was five years old, and spent the years of his childhood in the Palazzo Leopardi, with his mother, his brother and sister, and his great-uncle. His  On learning of

On learning of

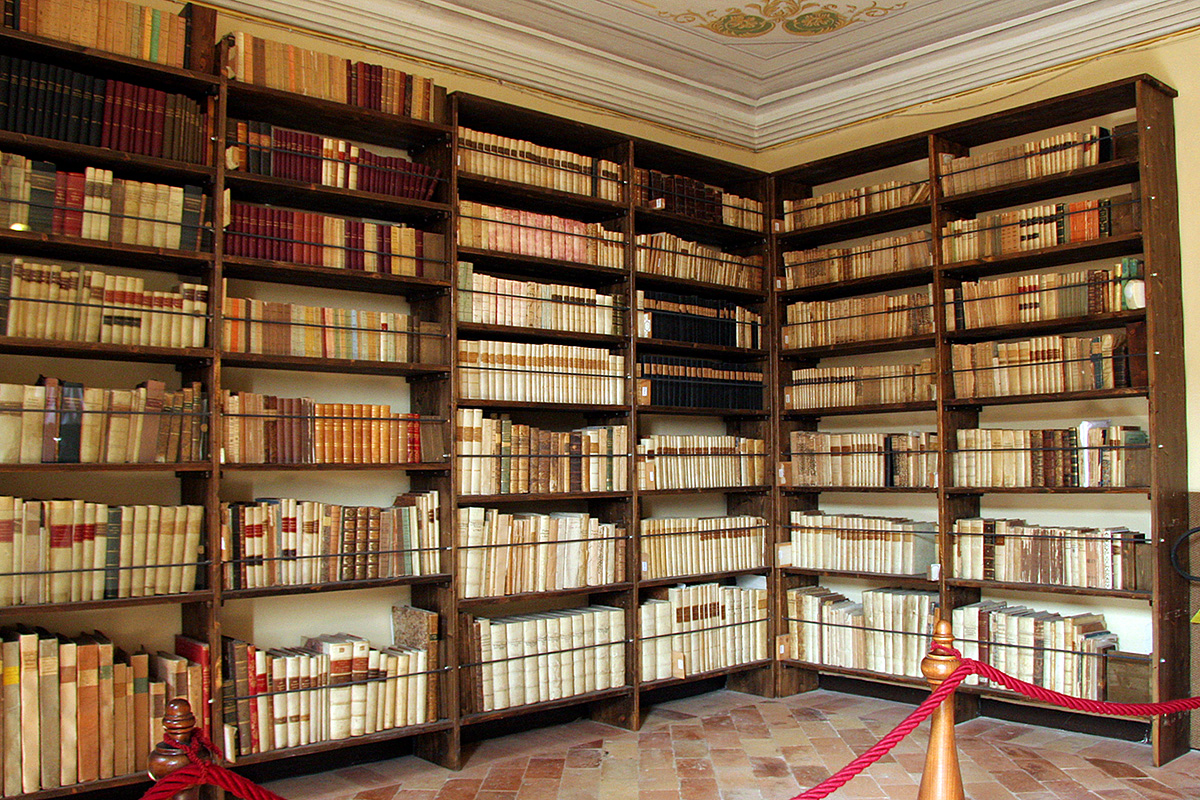

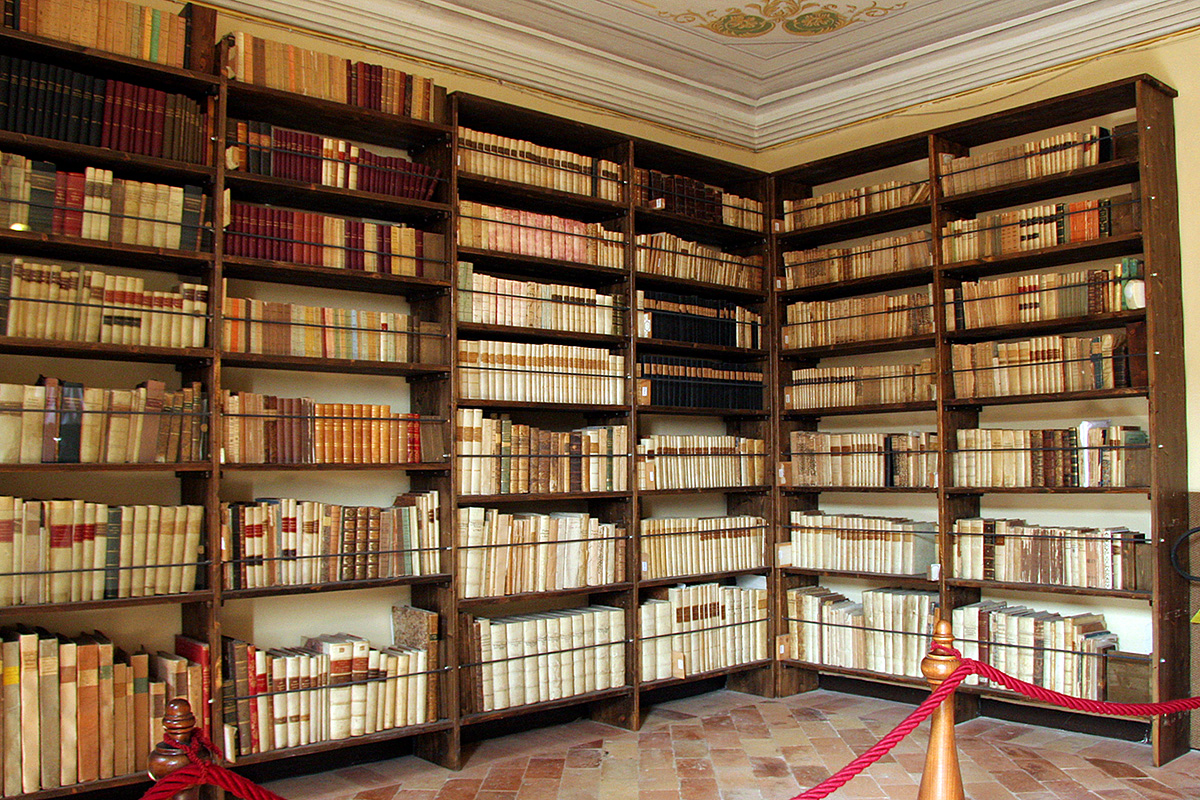

Monaldo Leopardi was a man of culture and learning. A poet in his youth, he later on became the author of many theological and political treatises, and revived in his native city a 'poetical Academy' which had previously existed there in 1400, under the name of 'I Disuguali Placidi'—literally, the Placidly Unequal, or those who can agree to disagree. Its meetings were held in the Palazzo Leopardi. Monaldo Leopardi had one of the most extensive private libraries in all of Europe. In his

Monaldo Leopardi was a man of culture and learning. A poet in his youth, he later on became the author of many theological and political treatises, and revived in his native city a 'poetical Academy' which had previously existed there in 1400, under the name of 'I Disuguali Placidi'—literally, the Placidly Unequal, or those who can agree to disagree. Its meetings were held in the Palazzo Leopardi. Monaldo Leopardi had one of the most extensive private libraries in all of Europe. In his

Recanati

Recanati () is a town and ''comune'' in the Province of Macerata, in the Marche region of Italy. Recanati was founded around 1150 AD from three pre-existing castles. In 1290 it proclaimed itself an independent republic and, in the 15th century, ...

, 16 August 1776 – Recanati, 30 April 1847) was an Italian philosopher, nobleman, politician and writer, notable as one of the main Italian intellectuals of the counter-revolution

A counter-revolutionary or an anti-revolutionary is anyone who opposes or resists a revolution, particularly one who acts after a revolution in order to try to overturn it or reverse its course, in full or in part. The adjective "counter-revoluti ...

. His son Giacomo Leopardi

Count Giacomo Taldegardo Francesco di Sales Saverio Pietro Leopardi (, ; 29 June 1798 – 14 June 1837) was an Italian philosopher, poet, essayist, and philologist. He is considered the greatest Italian poet of the nineteenth century and one of ...

was a poet and thinker with completely opposite views, which were probably the root cause of their discord.

Biography

tutor

TUTOR, also known as PLATO Author Language, is a programming language developed for use on the PLATO system at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign beginning in roughly 1965. TUTOR was initially designed by Paul Tenczar for use in ...

, Father José Matías de Torres, was an exiled Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

from Veracruz

Veracruz (), formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave (), officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave ( es, Estado Libre y Soberano de Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave), is one of the 31 states which, along with Me ...

, Mexico

Mexico (Spanish language, Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a List of sovereign states, country in the southern portion of North America. It is borders of Mexico, bordered to the north by the United States; to the so ...

. As a child, Monaldo spent several months in Pesaro

Pesaro () is a city and ''comune'' in the Italian region of Marche, capital of the Province of Pesaro e Urbino, on the Adriatic Sea. According to the 2011 census, its population was 95,011, making it the second most populous city in the Marche ...

at the home of his grandmother, Francesca, who years later came to stay with him in his palace in Recanati. At the age of eighteen he assumed, as head of the family, the complete management of the whole family property. In 1797 Monaldo married a capable woman, Marquise Adelaide Antici, two years his junior, and daughter of a neighboring Recanatese family. At the time of their marriage, Monaldo was the largest landholder in Recanati.

In the spring of 1797 the French Republican troops had made their first invasion of the Papal States, and now the Pope—having failed in various efforts to conciliate the enemy—decided to fight against France. After the fall of Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

, a regiment of Papal troops occupied Recanati, and began to prepare for its defence; but Monaldo succeeded in persuading its colonel that Recanati was indefensible, and that it would be better to take his troops away. During the next two years, a constant succession of troops—French, Papal, and Austrian—occupied the Marche

Marche ( , ) is one of the twenty regions of Italy. In English, the region is sometimes referred to as The Marches ( ). The region is located in the central area of the country, bordered by Emilia-Romagna and the republic of San Marino to the ...

. His indignation against the iniquities of the French Republican government was intense. The taxes imposed by it, he said in his Memoirs, were terrible—amounting, in his own case, to over twelve thousand scudi, besides a carriage, four horses, wood, oil, fodder, beds, sheets, and even clothes. He was deeply shocked, too, by the impiety of the Republicans: two of the churches of Recanati were turned into stable

A stable is a building in which livestock, especially horses, are kept. It most commonly means a building that is divided into separate stalls for individual animals and livestock. There are many different types of stables in use today; the ...

s, the black robes of the priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in partic ...

s were requisitioned, and the monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedic ...

s (as well as the rest of the population) were compelled to wear a cockade of France

The cockade of France (french: Cocarde tricolore) is the national ornament of France, obtained by circularly pleating a blue, white and red ribbon. It is composed of the three colors of the French flag with blue in the center, white immediately ...

and to take their turn, still clothed in their monk's habits, in mounting guard at the city gates. This government was temporarily brought to an end in Recanati by the arrival of a large number of insurgents

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irr ...

, who turned out the French, cut down the liberty pole

A liberty pole is a wooden pole, or sometimes spear or lance, surmounted by a "cap of liberty", mostly of the Phrygian cap. The symbol originated in the immediate aftermath of the assassination of the Roman dictator Julius Caesar by a group of R ...

they had erected in one of the city's squares, and elevated Monaldo himself, much against his will, to the position of governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

of the city.

A few months later the tables were turned again. With the help of Austrian troops the Marche were being freed from the French domination, and in 1799 the Republican army, in its turn, was shut up in Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

and besieged there. On 25 June 1800, the new Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII ( it, Pio VII; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. Chiaramonti was also a m ...

, on his triumphant return from France to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, went to Loreto, and even paid a morning visit to Recanati. The little city was decked in its best; the sailors of the port of Recanati, halfway to Loreto, unharnessed the horses of the Papal carriage and themselves drew it up the hill to the cathedral, where a large congregation of reinstated monks and nuns and an exulting congregation of the faithful came to kiss the Pope's toe, Monaldo of course among them.

This year, however, was the last in which Count Monaldo played a conspicuous part in the affairs of his city. After the Battle of Marengo

The Battle of Marengo was fought on 14 June 1800 between French forces under the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte and Austrian forces near the city of Alessandria, in Piedmont, Italy. Near the end of the day, the French overcame General Mich ...

, the Papal States again fell into the power of France, and as long as this rule lasted, Monaldo remained in complete retirement. Monaldo was overwhelmed with financial problems: he speculated disastrously on the price of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

and made an unfortunate attempt to redeem a part of the Roman Campagna

The Roman Campagna () is a low-lying area surrounding Rome in the Lazio region of central Italy, with an area of approximately .

It is bordered by the Tolfa and Sabatini mountains to the north, the Alban Hills to the southeast, and the Tyrrhenia ...

, by introducing new agricultural methods there with disastrous results. The mere interest on his debts now amounted to a sum equal to the whole family income, so that ruin seemed both imminent and inevitable. Monaldo, continually pressed and harassed by his creditors, was at his wits' end, and his wife Adelaide assumed, once and for all, complete command. She summoned a family council, laid bare the whole situation, persuaded Monaldo to resign the management of the estate to an administrator, signed an agreement with his creditors, and herself became the undisputed mistress of the household. Monaldo never succeeded in regaining financial independence.

On learning of

On learning of Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner, (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was a British physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines, and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

's breakthrough in developing a vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifie ...

against smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) c ...

, Monaldo was one of the first in Recanati to have his children vaccinated and to recommend it to others. He was interested in new methods of reclaiming fallow

Fallow is a farming technique in which arable land is left without sowing for one or more vegetative cycles. The goal of fallowing is to allow the land to recover and store organic matter while retaining moisture and disrupting pest life cycl ...

land, and took a leading role in introducing potato

The potato is a starchy food, a tuber of the plant ''Solanum tuberosum'' and is a root vegetable native to the Americas. The plant is a perennial in the nightshade family Solanaceae.

Wild potato species can be found from the southern Unit ...

cultivation in the Marche region. In 1812 Monaldo formally opened to the public the great library

A library is a collection of materials, books or media that are accessible for use and not just for display purposes. A library provides physical (hard copies) or digital access (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location or a vir ...

in his own house, which he had been preparing for the past ten years, hoping to upgrade the culture of his fellow citizens.

After the end of Napoleonic rule in Italy (1814), Monaldo resumed his political activity. He held the office of mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

of Recanati from 1816 to 1819, and from 1823 to 1826. As gonfalonier

The Gonfalonier (in Italian: ''Gonfaloniere'') was the holder of a highly prestigious communal office in medieval and Renaissance Italy, notably in Florence and the Papal States. The name derives from ''gonfalone'' (in English, gonfalon), the ter ...

, Monaldo promoted the construction of a new theatre in Recanati (today Teatro Giuseppe Persiani). The construction, announced in a poster dated 8th February 1823, was entrusted to the local architect Tommaso Brandoni. Work commenced two months later, but various difficulties considerably delayed its continuation and it was not completed until seventeen years later, at a final cost of 13,223 scudos. It was inaugurated on the evening of 7th January 1840 with the opera '' Beatrice di Tenda'' by Vincenzo Bellini

Vincenzo Salvatore Carmelo Francesco Bellini (; 3 November 1801 – 23 September 1835) was a Sicilian opera composer, who was known for his long-flowing melodic lines for which he was named "the Swan of Catania".

Many years later, in 1898, Giu ...

, on which occasion the theatre was dedicated to the town's renowned musician Giuseppe Persiani

Giuseppe Persiani (11 September 1799 – 13 August 1869) was an Italian opera composer.

Persiani was born in Recanati. He wrote his first opera - one of 11 - in 1826 but, after his marriage to the soprano Fanny Tacchinardi Persiani, who w ...

(1804-1869).

His relationship with his son Giacomo, of which we have testimony in the latter's ''Epistolario'', was profound but suffered, as is inevitable in an encounter, albeit bound by reciprocal affection, between two diametrically opposed temperaments with a completely different conception of life.

Monaldo died in Recanati in 1847.

Ideas

Monaldo Leopardi was heavily influenced by theconservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

writers and philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

s Joseph de Maistre

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre (; 1 April 1753 – 26 February 1821) was a Savoyard philosopher, writer, lawyer, and diplomat who advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immediately following the French Revolution. Despite his clos ...

(1754–1821) and Louis de Bonald

Louis Gabriel Ambroise, Vicomte de Bonald (2 October 1754 – 23 November 1840) was a French counter-revolutionary philosopher and politician. He is mainly remembered for developing a theoretical framework from which French sociology would ...

(1754–1840). He rejected the principles of liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

and democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

and was persuaded that social order

The term social order can be used in two senses: In the first sense, it refers to a particular system of social structures and institutions. Examples are the ancient, the feudal, and the capitalist social order. In the second sense, social order ...

should reflect the disparities in intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. More generally, it can b ...

and reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

that existed in nature.

For Monaldo, legitimate government had nothing to do with election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

s or popular choice. Political authority was a Divine Right and sovereignty always belonged to the one (or the few) who had a de facto superiority reflecting the Providential plan. Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

was the best form of government, because it guaranteed better than any other the sacred laws of hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

and obedience to authority

In the fields of sociology and political science, authority is the legitimate power of a person or group over other people. In a civil state, ''authority'' is practiced in ways such a judicial branch or an executive branch of government.''The N ...

.. Freedom should be curtailed for the sake of order and religious belief. At the end of the section of his autobiography that deals with his activities during the French occupation, he said this of himself: "One who is not cowardly can be free and indeed must be free, but the bases and limits of true freedom are the Faith of Jesus Christ, and faithfulness to the legitimate Sovereign. Outside of these boundaries one does not live freely, but dissolutely." His belief system demanded that absolute submission to the authority of both throne and altar be a universally accepted principle that, if violated, could only lead to a complete breakdown of order and responsibility.

Against the views of the Italian nationalists, Monaldo adopted both a Christian and a transcendental interpretation of motherland, (Heaven

Heaven or the heavens, is a common religious cosmological or transcendent supernatural place where beings such as deities, angels, souls, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or reside. According to the belie ...

being the only true homeland

A homeland is a place where a cultural, national, or racial identity has formed. The definition can also mean simply one's country of birth. When used as a proper noun, the Homeland, as well as its equivalents in other languages, often has ethni ...

to human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

kind), and one that was counter-revolutionary from a political perspective:

"the rebel is the exile from all homelands. Man's homeland is Heaven, and there is no homeland for the enemy of Heaven. He goes wandering about the earth, and cannot find a homeland on earth."Christians are citizens of two homelands simultaneously: the heavenly and the earthly. For Monaldo the earthly homeland was first and foremost one's city, or at most the borders of one's country of origin. Thus he rejected the political meaning of Italian nation advanced by the Italian revolutionaries, and denounced its fictitious nature, based as it was on the imagination of a community that in reality did not exist. The revolutionaries in fact wanted to breach "those natural barriers that divide a people from another", and deprive "each particular people of their usages and national customs". Between the attachment to one's town and catholic

universalism

Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept that some ideas have universal application or applicability.

A belief in one fundamental truth is another important tenet in universalism. The living truth is seen as more far-reaching th ...

there was no space for the crucial role as intermediary Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini (, , ; 22 June 1805 – 10 March 1872) was an Italian politician, journalist, and activist for the unification of Italy (Risorgimento) and spearhead of the Italian revolutionary movement. His efforts helped bring about the in ...

or Gioberti

Vincenzo Gioberti (; 5 April 180126 October 1852) was an Italian Catholic priest, philosopher, publicist and politician who served as the Prime Minister of Sardinia from 1848 to 1849. He was a prominent spokesman for liberal Catholicism.

Biog ...

had attributed to the nations in reconciling individuals and humanity.

Works

Monaldo Leopardi was a man of culture and learning. A poet in his youth, he later on became the author of many theological and political treatises, and revived in his native city a 'poetical Academy' which had previously existed there in 1400, under the name of 'I Disuguali Placidi'—literally, the Placidly Unequal, or those who can agree to disagree. Its meetings were held in the Palazzo Leopardi. Monaldo Leopardi had one of the most extensive private libraries in all of Europe. In his

Monaldo Leopardi was a man of culture and learning. A poet in his youth, he later on became the author of many theological and political treatises, and revived in his native city a 'poetical Academy' which had previously existed there in 1400, under the name of 'I Disuguali Placidi'—literally, the Placidly Unequal, or those who can agree to disagree. Its meetings were held in the Palazzo Leopardi. Monaldo Leopardi had one of the most extensive private libraries in all of Europe. In his Will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

he laid down that the 15,000 volumes of which it was then composed (in 1847) should never be removed from the rooms in which he had placed them, and should be at the disposal of the citizens of Recanati for at least three mornings a week.

Among his most successful works were the '' Dialoghetti sulle materie correnti nell’anno 1831'', that went through six editions and were translated into French, Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

and German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

; the ''Istoria evangelica'' (1832), praised by Pope Gregory XVI

Pope Gregory XVI ( la, Gregorius XVI; it, Gregorio XVI; born Bartolomeo Alberto Cappellari; 18 September 1765 – 1 June 1846) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 2 February 1831 to his death in 1 June 1846. He h ...

(1831-1846) and translated into Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

; ''Il Catechismo filosofico per uso delle scuole inferiori'' (1832), reprinted and adopted in the public schools of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and a ...

; and ''La città della filosofia'' (1833). ''Le Conferenze del Villaggio'' (Lugano, Veladini e Comp., 1838) were translated into French by David Paul Drach

David Paul Drach (born Strasbourg, 6 March 1791; died at the end of January, 1868, Rome) was a Catholic convert from Judaism, and librarian of the College of Propaganda in Rome.

Life

Drach received his first instruction at the hands of his fathe ...

, a close friend and admirer of Monaldo.

The ''Dialoghetti sulle materie correnti nell'anno 1831'' were first published in 1831 and had considerable success in Italy and abroad. The book was highly praised by Leopold von Ranke

Leopold von Ranke (; 21 December 1795 – 23 May 1886) was a German historian and a founder of modern source-based history. He was able to implement the seminar teaching method in his classroom and focused on archival research and the analysis of ...

and by the young Vincenzo Gioacchino Pecci (1810-1903), the future Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

(1878-1903). Giacomo, too, was at first not indifferent to this success nor did it displease him to be mistaken for the author, and only when his liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

friends in Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

and elsewhere began to criticize the reactionary

In political science, a reactionary or a reactionist is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the ''status quo ante'', the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics abse ...

nature of the book did he publicly disclaim its authorship. On the other hand, Monaldo's work was the object of severe criticism by liberal Catholics. In the August 1, 1834, issue of the ''Revue des deux Mondes

The ''Revue des deux Mondes'' (, ''Review of the Two Worlds'') is a monthly French-language literary, cultural and current affairs magazine that has been published in Paris since 1829.

According to its website, "it is today the place for debates a ...

'', Félicité de La Mennais

Félicité Robert de La Mennais (or Lamennais; 19 June 178227 February 1854) was a French Catholic priest, philosopher and political theorist. He was one of the most influential intellectuals of Restoration France. Lamennais is considered the fo ...

severely criticized the ''Dialoghetti'' in an article entitled “On Absolutism and Freedom.”

Monaldo was founder, manager, and editor of the influential extreme right-wing

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

newspaper

A newspaper is a periodical publication containing written information about current events and is often typed in black ink with a white or gray background.

Newspapers can cover a wide variety of fields such as politics, business, sports a ...

''La Voce della Ragione'' (The Voice of Reason), published from 1832 to 1835 and suppressed by order of the Roman Curia.

The '' Autobiografia di Monaldo Leopardi'' gives a vivid picture of the background of the Leopardi family, and a self-portrait of the author. It was published posthumously in 1883 but written in 1823, when the author was only 47 years old. The ''Autobiografia'' was reprinted in 1971 (Milan: Longanesi

Longanesi, also known as Longanesi & C., is a publishing house based in Milan, Italy. It was founded in 1946 by Leo Longanesi and industrialist Giovanni Monti.Nanni Delbecchi (13 May 2016). "Longanesi fa settanta. Il 'Dottor Naso' aveva fiuto". ' ...

), and republished in 1972 in conformity with the original manuscript preserved in the family archives in Recanati.Monaldo Leopardi, ''Autobiografia e Dialoghetti''. Introduzione di Carlo Grabher. Testo e note a cura di Alessandra Briganti. Bologna, Cappelli, 1972.

Works

* 1800: ''Le cose come sono.'' * 1822: ''Notizie della zecca recanatese.'' * 1824: ''Serie dei rettori della Marca anconetana.'' * 1828: ''Serie dei Vescovi di Recanati.'' * 1831: ''Dialoghetti sulle materie correnti nell'anno 1831.'' * 1832: ''Prediche al popolo liberale recitate da don Musoduro.'' * 1832: ''Testamento di don Pietro di Braganza, ex imperatore del Brasile.'' * 1832: ''Un'oretta di conversazione tra sei illustri matrone della buona antichità.'' * 1832: ''Sulle riforme del governo. Una parola ai sudditi del papa.'' * 1832: ''Aggiunte alla sesta edizione dei Dialoghetti.'' * 1832: ''Catechismo filosofico per uso delle scuole inferiori.'' * 1832: ''La città della filosofia.'' * 1834: ''La giustizia nei contratti e l'usura.'' * 1883: ''Autobiografia.''References

Notes Bibliography * * * Giacomo Leopardi, ''Il monarca delle Indie. Corrispondenza tra Giacomo e Monaldo Leopardi'', a cura di Graziella Pulce, introduzione di Giorgio Manganelli, Milano, Adelphi, 1988, . * * Monaldo Leopardi, ''Autobiografia'', con un saggio di Giulio Cattaneo, Roma, Dell'Altana ed., 1997, . * Giacomo Leopardi, ''Carissimo Signor Padre. Lettere a Monaldo'', Venosa, Osanna ed., 1997, . * Nicola Raponi, ''Due centenari. A proposito dell'autobiografia di Monaldo Leopardi'', Quaderni del Bicentenario. Pubblicazione periodica per il bicentenario del trattato di Tolentino (19 febbraio 1797), n. 4, Tolentino, 1999, pp. 31–50. * Monaldo Leopardi, ''Dialoghetti sulle materie correnti nell'anno 1831'' e ''Il viaggio di Pulcinella'', in AA. VV., ''L'Europa giudicata da un reazionario. Un confronto sui Dialoghetti di Monaldo Leopardi'', Diabasis, 2004. * Monaldo Leopardi, ''Catechismo filosofico e Catechismo sulle rivoluzioni'', Fede&Cultura, 2006. * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Leopardi 1776 births 1847 deaths People from Recanati 19th-century Italian philosophers Italian politicians Leopardi, Monaldo 19th-century Italian male writers 19th-century philosophers Italian essayists Male essayists Italian counter-revolutionaries Italian male non-fiction writers Italian newspaper founders Counts of Italy Traditionalist School Catholic philosophers Roman Catholic writers Critics of atheism Reactionary Conservatism in Italy