Miller–Urey Experiment on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Miller–Urey experiment (or Miller experiment) is a famous chemistry

The Miller–Urey experiment (or Miller experiment) is a famous chemistry

A simulation of the Miller–Urey Experiment along with a video Interview with Stanley Miller

by Scott Ellis from CalSpace (UCSD)

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090821213017/http://www.chem.duke.edu/~jds/cruise_chem/Exobiology/miller.html Miller–Urey experiment explained

Miller experiment with Lego bricks

* ttp://www.millerureyexperiment.com/ The Miller-Urey experiment website*

Details of 2008 re-analysis

{{DEFAULTSORT:Miller-Urey Experiment Articles containing video clips Biology experiments Chemical synthesis of amino acids Chemistry experiments Origin of life 1952 in biology 1953 in biology 2008 in science

The Miller–Urey experiment (or Miller experiment) is a famous chemistry

The Miller–Urey experiment (or Miller experiment) is a famous chemistry experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs wh ...

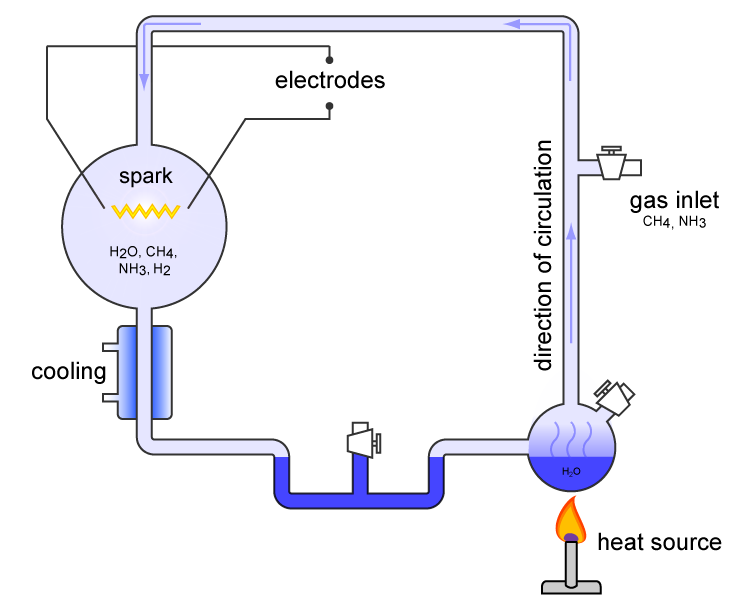

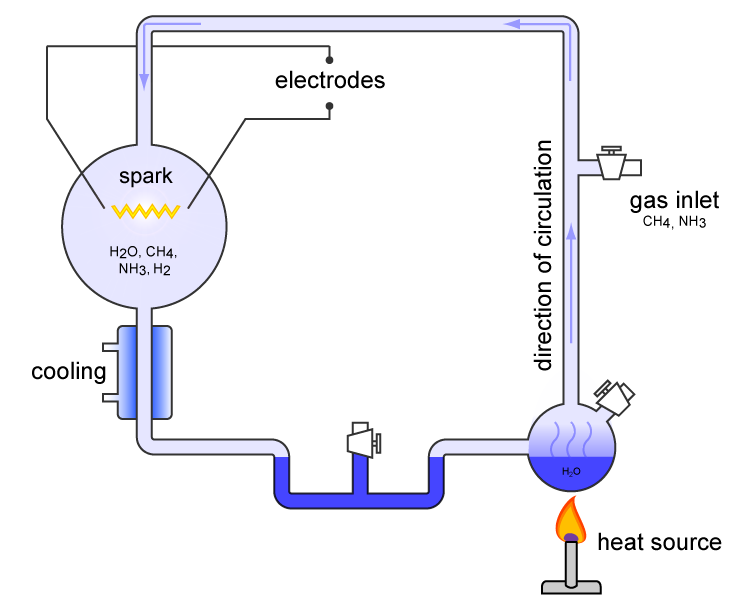

that simulated the conditions thought at the time (1952) to be present in the atmosphere of the early, prebiotic Earth, in order to test the hypothesis of the chemical origin of life under those conditions. The experiment used water (H2O), methane (CH4), ammonia (NH3), hydrogen (H2), and an electric arc (the latter simulating hypothesized lightning).

At the time, it supported Alexander Oparin

Alexander Ivanovich Oparin (russian: Александр Иванович Опарин; – April 21, 1980) was a Soviet biochemist notable for his theories about the origin of life, and for his book ''The Origin of Life''. He also studied the bi ...

's and J. B. S. Haldane's hypothesis that the hypothesized conditions on the primitive Earth favored chemical reactions that synthesized more complex organic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon- hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. Th ...

s from simpler inorganic precursors. One of the most famous experiments of all time, it is considered to be groundbreaking, and to be the classic experiment investigating abiogenesis

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothe ...

. It was performed in 1952 by Stanley Miller, supervised by Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the ...

at the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chic ...

, and published the following year.

After Miller's death in 2007, scientists examining sealed vials preserved from the original experiments were able to show that there were actually well over 20 different amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

s produced in Miller's original experiments. That is considerably more than what Miller originally reported, and more than the 20 that naturally occur in the genetic code. More recent evidence suggests that Earth's original atmosphere might have had a composition different from the gas used in the Miller experiment, but prebiotic experiments continue to produce racemic mixture

In chemistry, a racemic mixture, or racemate (), is one that has equal amounts of left- and right-handed enantiomers of a chiral molecule or salt. Racemic mixtures are rare in nature, but many compounds are produced industrially as racemates. ...

s of simple-to-complex compounds—such as cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

—under varying conditions.

Experiment

Methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Ear ...

(CH4), water

Water (chemical formula ) is an inorganic, transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, which is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as ...

(H2O), ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogeno ...

(NH3), and hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic ...

(H2) were all sealed together inside a sterile 5-liter glass flask connected to a 500 ml flask half-full of water. The water in the smaller flask was heated to induce evaporation, and the water vapor was allowed to enter the larger flask. A continuous electrical spark was discharged between a pair of electrodes in the larger flask. The spark passed through the mixture of gases and water vapor, simulating lightning

Lightning is a naturally occurring electrostatic discharge during which two electrically charged regions, both in the atmosphere or with one on the ground, temporarily neutralize themselves, causing the instantaneous release of an average ...

in the hypothesized primordial atmosphere of the earth. Then the apparatus was cooled so that the water condensed and trickled into a U-shaped trap at the bottom.

After a day, the solution that had collected at the trap was pink, and after a week of continuous operation the solution was a deep red and turbid. The boiling flask was then removed, and mercuric chloride was added to prevent microbial contamination. The reaction was stopped by adding barium hydroxide and sulfuric acid, and evaporated to remove impurities. Using paper chromatography

Paper chromatography is an analytical method used to separate coloured chemicals or substances. It is now primarily used as a teaching tool, having been replaced in the laboratory by other chromatography methods such as thin-layer chromatograph ...

, Miller identified five amino acids present in the solution: glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid ( carbamic acid is unstable), with the chemical formula NH2‐ CH2‐ COOH. Glycine is one of the proteinog ...

, α-alanine and β-alanine were positively identified, while aspartic acid

Aspartic acid (symbol Asp or D; the ionic form is known as aspartate), is an α- amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Like all other amino acids, it contains an amino group and a carboxylic acid. Its α-amino group is in the pr ...

and α-aminobutyric acid (AABA) were less certain, due to the spots being faint.

In a 1996 interview, Stanley Miller recollected his lifelong experiments following his original work and stated: "Just turning on the spark in a basic pre-biotic experiment will yield 11 out of 20 amino acids."

The original experiment remained in 2017 under the care of Miller and Urey's former student Jeffrey Bada, a professor at the UCSD

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UC San Diego is th ...

, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography (sometimes referred to as SIO, Scripps Oceanography, or Scripps) in San Diego, California, US founded in 1903, is one of the oldest and largest centers for ocean and Earth science research, public servi ...

. , the apparatus used to conduct the experiment was on display at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science

The Denver Museum of Nature & Science is a municipal natural history and science museum in Denver, Colorado. It is a resource for informal science education in the Rocky Mountain region. A variety of exhibitions, programs, and activities help mus ...

.

Chemistry of experiment

One-step reactions among the mixture components can producehydrogen cyanide

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure . It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at . HCN is produced on a ...

(HCN), formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) ( systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section ...

(CH2O), and other active intermediate compounds (acetylene

Acetylene ( systematic name: ethyne) is the chemical compound with the formula and structure . It is a hydrocarbon and the simplest alkyne. This colorless gas is widely used as a fuel and a chemical building block. It is unstable in its pur ...

, cyanoacetylene

Cyanoacetylene is an organic compound with formula or . It is the simplest cyanopolyyne. Cyanoacetylene has been detected by spectroscopic methods in interstellar clouds, in the coma of comet Hale–Bopp and in the atmosphere of Saturn's mo ...

, etc.):

: CO2 → CO + (atomic oxygen)

: CH4 + 2 → CH2O + H2O

: CO + NH3 → HCN + H2O

: CH4 + NH3 → HCN + 3H2 ( BMA process)

The formaldehyde, ammonia, and HCN then react by Strecker synthesis

The Strecker amino acid synthesis, also known simply as the Strecker synthesis, is a method for the synthesis of amino acids by the reaction of an aldehyde with ammonia in the presence of potassium cyanide. The condensation reaction yields an α- ...

to form amino acids and other biomolecules:

: CH2O + HCN + NH3 → NH2-CH2-CN + H2O

: NH2-CH2-CN + 2H2O → NH3 + NH2-CH2-COOH (glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid ( carbamic acid is unstable), with the chemical formula NH2‐ CH2‐ COOH. Glycine is one of the proteinog ...

)

Furthermore, water and formaldehyde can react, via Butlerov's reaction to produce various sugars like ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally-occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this compou ...

.

The experiments showed that simple organic compounds of building blocks of proteins and other macromolecules can be formed from gases with the addition of energy.

Other experiments

This experiment inspired many others. In 1961, Joan Oró found that thenucleotide

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecul ...

base adenine

Adenine () (symbol A or Ade) is a nucleobase (a purine derivative). It is one of the four nucleobases in the nucleic acid of DNA that are represented by the letters G–C–A–T. The three others are guanine, cytosine and thymine. Its derivativ ...

could be made from hydrogen cyanide

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure . It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at . HCN is produced on a ...

(HCN) and ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogeno ...

in a water solution. His experiment produced a large amount of adenine, the molecules of which were formed from 5 molecules of HCN.

Also, many amino acids are formed from HCN and ammonia under these conditions.

Experiments conducted later showed that the other RNA and DNA nucleobases could be obtained through simulated prebiotic chemistry with a reducing atmosphere

A reducing atmosphere is an atmospheric condition in which oxidation is prevented by removal of oxygen and other oxidizing gases or vapours, and which may contain actively reducing gases such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and gases such as hydro ...

.

There also had been similar electric discharge experiments related to the origin of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

contemporaneous with Miller–Urey. An article in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' (March 8, 1953:E9), titled "Looking Back Two Billion Years" describes the work of Wollman (William) M. MacNevin at Ohio State University

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best pu ...

, before the Miller ''Science'' paper was published in May 1953. MacNevin was passing 100,000 volt sparks through methane and water vapor and produced "resinous solids" that were "too complex for analysis." The article describes other early earth experiments being done by MacNevin. It is not clear if he ever published any of these results in the primary scientific literature.

K. A. Wilde submitted a paper to ''Science'' on December 15, 1952, before Miller submitted his paper to the same journal on February 10, 1953. Wilde's paper was published on July 10, 1953. Wilde used voltages up to only 600 V on a binary mixture of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

(CO2) and water in a flow system. He observed only small amounts of carbon dioxide reduction to carbon monoxide, and no other significant reduction products or newly formed carbon compounds.

Other researchers were studying UV-photolysis

Photodissociation, photolysis, photodecomposition, or photofragmentation is a chemical reaction in which molecules of a chemical compound are broken down by photons. It is defined as the interaction of one or more photons with one target molecule. ...

of water vapor with carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide ( chemical formula CO) is a colorless, poisonous, odorless, tasteless, flammable gas that is slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

. They have found that various alcohols, aldehydes and organic acids were synthesized in reaction mixture.

More recent experiments by chemists Jeffrey Bada, one of Miller's graduate students, and Jim Cleaves at Scripps Institution of Oceanography

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography (sometimes referred to as SIO, Scripps Oceanography, or Scripps) in San Diego, California, US founded in 1903, is one of the oldest and largest centers for ocean and Earth science research, public servi ...

of the University of California, San Diego

The University of California, San Diego (UC San Diego or colloquially, UCSD) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in San Diego, California. Established in 1960 near the pre-existing Scripps Insti ...

were similar to those performed by Miller. However, Bada noted that in current models of early Earth conditions, carbon dioxide and nitrogen

Nitrogen is the chemical element with the symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at seve ...

(N2) create nitrite

The nitrite ion has the chemical formula . Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name nitrite also re ...

s, which destroy amino acids as fast as they form. When Bada performed the Miller-type experiment with the addition of iron and carbonate minerals, the products were rich in amino acids. This suggests the origin of significant amounts of amino acids may have occurred on Earth even with an atmosphere containing carbon dioxide and nitrogen.Earth's early atmosphere

Some evidence suggests that Earth's original atmosphere might have contained fewer of the reducing molecules than was thought at the time of the Miller–Urey experiment. There is abundant evidence of major volcanic eruptions 4 billion years ago, which would have released carbon dioxide, nitrogen,hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is poisonous, corrosive, and flammable, with trace amounts in ambient atmosphere having a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. The und ...

(H2S), and sulfur dioxide

Sulfur dioxide ( IUPAC-recommended spelling) or sulphur dioxide (traditional Commonwealth English) is the chemical compound with the formula . It is a toxic gas responsible for the odor of burnt matches. It is released naturally by volcanic ...

(SO2) into the atmosphere. Experiments using these gases in addition to the ones in the original Miller–Urey experiment have produced more diverse molecules. The experiment created a mixture that was racemic (containing both L and D enantiomer

In chemistry, an enantiomer ( /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''; from Ancient Greek ἐνάντιος ''(enántios)'' 'opposite', and μέρος ''(méros)'' 'part') – also called optical isomer, antipode, or optical ant ...

s) and experiments since have shown that "in the lab the two versions are equally likely to appear"; however, in nature, L amino acids dominate. Later experiments have confirmed disproportionate amounts of L or D oriented enantiomers are possible.

Originally it was thought that the primitive secondary atmosphere contained mostly ammonia and methane. However, it is likely that most of the atmospheric carbon was CO2, with perhaps some CO and the nitrogen mostly N2. In practice gas mixtures containing CO, CO2, N2, etc. give much the same products as those containing CH4 and NH3 so long as there is no O2. The hydrogen atoms come mostly from water vapor. In fact, in order to generate aromatic amino acids under primitive Earth conditions it is necessary to use less hydrogen-rich gaseous mixtures. Most of the natural amino acids, hydroxyacids, purines, pyrimidines, and sugars have been made in variants of the Miller experiment.

More recent results may question these conclusions. The University of Waterloo and University of Colorado conducted simulations in 2005 that indicated that the early atmosphere of Earth could have contained up to 40 percent hydrogen—implying a much more hospitable environment for the formation of prebiotic organic molecules. The escape of hydrogen from Earth's atmosphere into space may have occurred at only one percent of the rate previously believed based on revised estimates of the upper atmosphere's temperature. One of the authors, Owen Toon notes: "In this new scenario, organics can be produced efficiently in the early atmosphere, leading us back to the organic-rich soup-in-the-ocean concept... I think this study makes the experiments by Miller and others relevant again." Outgassing calculations using a chondritic model for the early Earth complement the Waterloo/Colorado results in re-establishing the importance of the Miller–Urey experiment.

In contrast to the general notion of early Earth's reducing atmosphere, researchers at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute () (RPI) is a private research university in Troy, New York, with an additional campus in Hartford, Connecticut. A third campus in Groton, Connecticut closed in 2018. RPI was established in 1824 by Stephen Va ...

in New York reported the possibility of oxygen available around 4.3 billion years ago. Their study reported in 2011 on the assessment of Hadean zircons from the Earth's interior (magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natura ...

) indicated the presence of oxygen traces similar to modern-day lavas. This study suggests that oxygen could have been released in the earth's atmosphere earlier than generally believed.

In November 2020, a team of international scientists reported their study on oxidation of the magma

Magma () is the molten or semi-molten natural material from which all igneous rocks are formed. Magma is found beneath the surface of the Earth, and evidence of magmatism has also been discovered on other terrestrial planets and some natura ...

around 4.5 billion years ago suggesting that the original atmosphere of the Earth contained little amount of oxygen and no methane or ammonia as presumed in the Miller–Urey experiment. CO2 was likely the most abundant component, with nitrogen and water as additional constituents. However, methane and ammonia could have appeared a little later as the atmosphere became more reducing. These gases being unstable were gradually destroyed by solar radiation (photolysis) and lasted about ten million years before they were eventually replaced by hydrogen and CO2.

Extraterrestrial sources

Conditions similar to those of the Miller–Urey experiments are present in other regions of theSolar System

The Solar System Capitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar ...

, often substituting ultraviolet

Ultraviolet (UV) is a form of electromagnetic radiation with wavelength from 10 nm (with a corresponding frequency around 30 PHz) to 400 nm (750 THz), shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiati ...

light for lightning as the energy source for chemical reactions. The Murchison meteorite

The Murchison meteorite is a meteorite that fell in Australia in 1969 near Murchison, Victoria. It belongs to the carbonaceous chondrite class, a group of meteorites rich in organic compounds. Due to its mass (over ) and the fact that it was an ...

that fell near Murchison, Victoria

Murchison is a small riverside rural village located on the Goulburn River in Victoria, Australia. Murchison is located 167 kilometres from Melbourne and is just to the west of the Goulburn Valley Highway between Shepparton and Nagambie. The s ...

, Australia in 1969 was found to contain many different amino acid types. Comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma, and sometimes also a Comet ta ...

s and other icy outer-solar-system bodies are thought to contain large amounts of complex carbon compounds (such as tholin

Tholins (after the Greek (') "hazy" or "muddy"; from the ancient Greek word meaning "sepia ink") are a wide variety of organic compounds formed by solar ultraviolet or cosmic ray irradiation of simple carbon-containing compounds such as carbon ...

s) formed by these processes, darkening surfaces of these bodies. The early Earth was bombarded heavily by comets, possibly providing a large supply of complex organic molecules along with the water and other volatiles they contributed. This has been used to infer an origin of life outside of Earth: the panspermia

Panspermia () is the hypothesis, first proposed in the 5th century BCE by the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras, that life exists throughout the Universe, distributed by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, and planetoids, as well as by space ...

hypothesis.

Recent related studies

In recent years, studies have been made of theamino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha ...

composition of the products of "old" areas in "old" genes, defined as those that are found to be common to organisms from several widely separated species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

, assumed to share only the last universal ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; th ...

(LUA) of all extant species. These studies found that the products of these areas are enriched in those amino acids that are also most readily produced in the Miller–Urey experiment. This suggests that the original genetic code was based on a smaller number of amino acids – only those available in prebiotic nature – than the current one.

Jeffrey Bada, himself Miller's student, inherited the original equipment from the experiment when Miller died in 2007. Based on sealed vials from the original experiment, scientists have been able to show that although successful, Miller was never able to find out, with the equipment available to him, the full extent of the experiment's success. Later researchers have been able to isolate even more different amino acids, 25 altogether. Bada has estimated that more accurate measurements could easily bring out 30 or 40 more amino acids in very low concentrations, but the researchers have since discontinued the testing. Miller's experiment was therefore a remarkable success at synthesizing complex organic molecules from simpler chemicals, considering that all known life uses just 20 different amino acids.

In 2008, a group of scientists examined 11 vials left over from Miller's experiments of the early 1950s. In addition to the classic experiment, reminiscent of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

's envisioned "warm little pond", Miller had also performed more experiments, including one with conditions similar to those of volcanic

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates ...

eruptions. This experiment had a nozzle spraying a jet of steam at the spark discharge. By using high-performance liquid chromatography

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), formerly referred to as high-pressure liquid chromatography, is a technique in analytical chemistry used to separate, identify, and quantify each component in a mixture. It relies on pumps to pa ...

and mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a '' mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is u ...

, the group found more organic molecules than Miller had. They found that the volcano-like experiment had produced the most organic molecules, 22 amino acids, 5 amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are compounds and functional groups that contain a basic nitrogen atom with a lone pair. Amines are formally derivatives of ammonia (), wherein one or more hydrogen atoms have been replaced by a substituent su ...

s and many hydroxylate

In chemistry, hydroxylation can refer to:

*(i) most commonly, hydroxylation describes a chemical process that introduces a hydroxyl group () into an organic compound.

*(ii) the ''degree of hydroxylation'' refers to the number of OH groups in a ...

d molecules, which could have been formed by hydroxyl radical

The hydroxyl radical is the diatomic molecule . The hydroxyl radical is very stable as a dilute gas, but it decays very rapidly in the condensed phase. It is pervasive in some situations. Most notably the hydroxyl radicals are produced from the ...

s produced by the electrified steam. The group suggested that volcanic island systems became rich in organic molecules in this way, and that the presence of carbonyl sulfide

Carbonyl sulfide is the chemical compound with the linear formula OCS. It is a colorless flammable gas with an unpleasant odor. It is a linear molecule consisting of a carbonyl group double bonded to a sulfur atom. Carbonyl sulfide can be consid ...

there could have helped these molecules form peptide

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides. ...

s.

The main problem of theories based around amino acids is the difficulty in obtaining spontaneous formation of peptides. Since John Desmond Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular book ...

's suggestion that clay surfaces could have played a role in abiogenesis

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothe ...

, scientific efforts have been dedicated to investigating clay-mediated peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 ( nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein c ...

formation, with limited success. Peptides formed remained over-protected and shown no evidence of inheritance or metabolism. In December 2017 a theoretical model developed by Valentina Erastova and collaborators suggested that peptides could form at the interlayers of layered double hydroxides

Layered double hydroxides (LDH) are a class of ionic solids characterized by a layered structure with the generic layer sequence cB Z AcBsub>''n'', where c represents layers of metal cations, A and B are layers of hydroxide () anions, and Z are ...

such as green rust

Green rust is a generic name for various green crystalline chemical compounds containing iron(II) and iron(III) cations, the hydroxide () anion, and another anion such as carbonate (), chloride (), or sulfate (), in a layered double hydroxi ...

in early earth conditions. According to the model, drying of the intercalated layered material should provide energy and co-alignment required for peptide bond formation in a ribosome-like fashion, while re-wetting should allow mobilising the newly formed peptides and repopulate the interlayer with new amino acids. This mechanism is expected to lead to the formation of 12+ amino acid-long peptides within 15-20 washes. Researches also observed slightly different adsorption preferences for different amino acids, and postulated that, if coupled to a diluted solution of mixed amino acids, such preferences could lead to sequencing.

In October 2018, researchers at McMaster University

McMaster University (McMaster or Mac) is a public research university in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The main McMaster campus is on of land near the residential neighbourhoods of Ainslie Wood and Westdale, adjacent to the Royal Botanical ...

on behalf of the Origins Institute announced the development of a new technology, called a '' Planet Simulator'', to help study the origin of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothes ...

on planet Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

and beyond.

Amino acids identified

Below is a table of amino acids produced and identified in the "classic" 1952 experiment, as published by Miller in 1953, the 2008 re-analysis of vials from the volcanic spark discharge experiment, and the 2010 re-analysis of vials from the H2S-rich spark discharge experiment.References

External links

A simulation of the Miller–Urey Experiment along with a video Interview with Stanley Miller

by Scott Ellis from CalSpace (UCSD)

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20090821213017/http://www.chem.duke.edu/~jds/cruise_chem/Exobiology/miller.html Miller–Urey experiment explained

Miller experiment with Lego bricks

* ttp://www.millerureyexperiment.com/ The Miller-Urey experiment website*

Details of 2008 re-analysis

{{DEFAULTSORT:Miller-Urey Experiment Articles containing video clips Biology experiments Chemical synthesis of amino acids Chemistry experiments Origin of life 1952 in biology 1953 in biology 2008 in science