Military Tactics Of Alexander The Great on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The military tactics of

However its true creator was

However its true creator was  Philip's army consisted of a core of professional infantrymen, the ''

Philip's army consisted of a core of professional infantrymen, the ''

Darius fled with his guard of

Darius fled with his guard of

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

(356 BC - 323 BC) show that he was one of the greatest generals in history. During the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC), won against the Athenian and Theban armies, and the battles of Granicius (334 BC) and of Issos (333 BC), won against the Achaemenid Persian army of Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dar ...

, Alexander employed the so-called "hammer and anvil" tactic. However, in the battle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

(331 BC), the Persians possessed an army vastly superior in numbers to the Macedonian army. This tactic of encirclement by rapid shock units was not very feasible. Alexander had to compose and decide on an innovative combat formation for the time; he arranged his units in levels; he pretended to want to encircle the enemy in order to better divide it and thus opened a breach in its defensive lines.

Troop composition and weapons

The origin of aline infantry

Line infantry was the type of infantry that composed the basis of European land armies from the late 17th century to the mid-19th century. Maurice of Nassau and Gustavus Adolphus are generally regarded as its pioneers, while Turenne and Monte ...

with a hoplitic formation has to be traced back to the reign of Archelaus.

Before him, the only heavy infantry available to the Kingdom of Macedonia

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled by ...

was supplied by the allied Greek cities.

However its true creator was

However its true creator was Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

, considered the inventor of the Macedonian phalanx

The Macedonian phalanx ( gr, Μακεδονική φάλαγξ) was an infantry formation developed by Philip II from the classical Greek phalanx, of which the main innovation was the use of the sarissa, a 6 meter pike. It was famously commanded b ...

: a particularly effective heavy infantry, freed of a part of its defensive armament—the shield was reduced by a third, the cuirass abandoned—in favor of a longer pike

Pike, Pikes or The Pike may refer to:

Fish

* Blue pike or blue walleye, an extinct color morph of the yellow walleye ''Sander vitreus''

* Ctenoluciidae, the "pike characins", some species of which are commonly known as pikes

* ''Esox'', genus of ...

(),Daremberg et Saglio, ''Phalanx'' dans le ''Dictionnaire des Antiquités grecques et romaines'', p. 425. Université de Toulouse. the sarissa

The sarisa or sarissa ( el, σάρισα) was a long spear or pike about in length. It was introduced by Philip II of Macedon and was used in his Macedonian phalanxes as a replacement for the earlier dory, which was considerably shorter. Thes ...

, and of an increased loading speed.

The length of the sarissa allowed to increase the number of file

File or filing may refer to:

Mechanical tools and processes

* File (tool), a tool used to ''remove'' fine amounts of material from a workpiece

**Filing (metalworking), a material removal process in manufacturing

** Nail file, a tool used to gent ...

of hoplites

Hoplites ( ) ( grc, ὁπλίτης : hoplítēs) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The fo ...

that could fight. The sarissa consisted of a point at each extremity and was heavy (). At its base, a short iron point allowed it to be planted in the ground to stop the charge of enemy soldiers. This strategy was particularly effective in breaking the cavalry charges

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating a ...

or the opposing phalanxs. But the Macedonian phalanx was also fearsome in offensive use. The principle was to accumulate the maximum kinetic energy

In physics, the kinetic energy of an object is the energy that it possesses due to its motion.

It is defined as the work needed to accelerate a body of a given mass from rest to its stated velocity. Having gained this energy during its accele ...

so that the impact of the lances

A lance is a spear designed to be used by a mounted warrior or cavalry soldier (lancer). In ancient and medieval warfare, it evolved into the leading weapon in cavalry charges, and was unsuited for throwing or for repeated thrusting, unlike sim ...

would be as devastating as possible. To this end, the hoplites charged in compact group of 16 files so tightly packed that their masses were built up. The lightening of the equipment increased the speed of the phalanx.

The Macedonian phalanxes were from then on much more powerful than their classical counterparts and the impact was likely to bring down many ranks of enemy infantrymen. To increase this effect the sarissas were raised to the vertical during the charge

Charge or charged may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Charge, Zero Emissions/Maximum Speed'', a 2011 documentary

Music

* ''Charge'' (David Ford album)

* ''Charge'' (Machel Montano album)

* ''Charge!!'', an album by The Aqua ...

—they formed a very tight net that stopped the projectiles—and set horizontal at the last moment, the pole impelled forward the shoulder of the infantryman creating a shock wave that propagated to the front rank and released a destructive impact on the enemy infantry, accumulating the energy of the driven mass of the hoplites with that of the lowering of the sarissas. Outside the tight formation of the phalanx, the sarissa caused discomfort during marches

In medieval Europe, a march or mark was, in broad terms, any kind of borderland, as opposed to a national "heartland". More specifically, a march was a border between realms or a neutral buffer zone under joint control of two states in which diff ...

and therefore, it was divided into two parts that were united before the battle.

Another advantage of this armament

A weapon, arm or armament is any implement or device that can be used to deter, threaten, inflict physical damage, harm, or kill. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, s ...

was that it was less expensive, thus allowing to equip a large number of soldiers

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word , from Old French ...

. This military reform also had considerable political consequences, since it made it possible to integrate a considerably larger number of Macedonians in the defense of the kingdom and in its political life. At the end of Philip's reign, the number of Macedonians mobilizable in heavy infantry recruited on a territorial basis was estimated at 30,000.

Philip's army consisted of a core of professional infantrymen, the ''

Philip's army consisted of a core of professional infantrymen, the ''pezhetairoi

The pezhetairoi (Greek: , singular: ''pezhetairos)'' were the backbone of the Macedonian army and Diadochi kingdoms. They were literally "foot companions" (in Greek, ''pezos'' means "pedestrian" and ''hetairos'' means "companion" or "friend").

T ...

'' (fellow footmen)—who constituted the royal guard—and a territorial levy.

Alexander's army consisted of 24,000 infantrymen divided into 12 '' taxeis'' of phalangites of about 1,500 men and three '' quiliarchies'' of 1000 ''hypaspists

A hypaspist ( el, Ὑπασπιστής "shield bearer" or "shield covered") is a squire, man at arms, or "shield carrier". In Homer, Deiphobos advances "" () or under cover of his shield. By the time of Herodotus (426 BC), the word had come ...

''. It is necessary to add an undetermined number of archers and other light phalangites. Alexander extended the denomination of ''pezhetairoi

The pezhetairoi (Greek: , singular: ''pezhetairos)'' were the backbone of the Macedonian army and Diadochi kingdoms. They were literally "foot companions" (in Greek, ''pezos'' means "pedestrian" and ''hetairos'' means "companion" or "friend").

T ...

'' to the group of phalangites

The Macedonian phalanx ( gr, Μακεδονική φάλαγξ) was an infantry formation developed by Philip II from the classical Greek phalanx, of which the main innovation was the use of the sarissa, a 6 meter pike. It was famously commanded b ...

, which explains the loyalty that the latter showed to him, and after his death, to his direct descendants.

The second masterpiece of the Macedonian army was the heavy cavalry recruited among the Macedonian nobility, called the Companion Cavalry ('' hetairoi''). It consisted of 3,000 heavy, shock-capable cavalry, at the beginning of Alexander's campaigns, of which 1,800 accompanied him in Asia. It was divided into 12 squadrons, the first being the Royal Squadron (''basilikè ilè''), also called the άγεμα, ''agêma'', 'that which leads'. This squadron was 300 strong, while the other squadrons consisted of 250 lancers.

The basic cavalry unit was an '' ilē'', a squadron of 250 Companions commanded by an ''ilarch'', and was divided into two ''lochoi'', in turn divided into two ''tetrarchies'' of 60 cavalrymen, commanded by a ''tetrarch''. Between 330 BC and 328 BC, the Companions were reformed into regiments (hipparchies) of 2-3 squadrons. In conjunction with this, each squadron was divided into two lochoi.

The tactical formation of the Companions was the wedge, adopted by Philip II from the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Eastern Iranian languages, Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved f ...

. The squadron commander was at the point of this triangular formation. The formation was very manoeuvrable, with the squadron following its leader at the apex, "like a flight of cranes".

Each Companion had a servant in charge of looking after his horse and equipment. The cavalrymen owned their mount, and when they enlisted they received the money needed to buy a quality one.

The Companion cavalry wore helmets, at first of the ''Phrygian'' type, painted with the colors of the squadron, until Alexander imposed the simpler ''boeotian

Boeotia ( ), sometimes Latinized as Boiotia or Beotia ( el, Βοιωτία; modern: ; ancient: ), formerly known as Cadmeis, is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Central Greece. Its capital is Livadeia, and its lar ...

'' model. The helmets of officers were decorated with painted or metallic laurel wreaths, which indicated their rank. They wore a cuirass and boots, but no shield. They were armed with a long spear (''xyston

The xyston ( grc, ξυστόν "spear, javelin; pointed or spiked stick, goad (lit. 'shaved', a derivative of the verb ξύω "scrape, shave")), was a type of a long thrusting spear in ancient Greece. It measured about long and was probably he ...

'') made of cornelian

Carnelian (also spelled cornelian) is a brownish-red mineral commonly used as a semi-precious gemstone. Similar to carnelian is sard, which is generally harder and darker (the difference is not rigidly defined, and the two names are often use ...

wood, provided with a point at either end, so that it could be used if it broke. As a secondary weapon, the Companion carried on the left side a sword (''kopis

The term kopis ( grc, Κόπις) in Ancient Greece could describe a heavy knife with a forward-curving blade, primarily used as a tool for cutting meat, for ritual slaughter and animal sacrifice, or refer to a single edged cutting or "cut and ...

'', ''makhaira

The makhaira is a type of Ancient Greek bladed weapon, generally a large knife or sword with a single cutting edge.

Terminology

The Greek word μάχαιρα (''mákhaira'', plural ''mákhairai''), also transliterated ''machaira'' or ''mac ...

'' or ''xyston

The xyston ( grc, ξυστόν "spear, javelin; pointed or spiked stick, goad (lit. 'shaved', a derivative of the verb ξύω "scrape, shave")), was a type of a long thrusting spear in ancient Greece. It measured about long and was probably he ...

'').

The tactical use of this cavalry was based on the Achilles heel

An Achilles' heel (or Achilles heel) is a weakness in spite of overall strength, which can lead to downfall. While the mythological origin refers to a physical vulnerability, idiomatic references to other attributes or qualities that can lead to ...

of the phalanxes. Their vulnerability in the flanks and rearguard

A rearguard is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an army. Even more ...

—it was practically impossible to pivot to stop a flank and rearguard attack due to the hindrance of the sarissas. The destructive effect of the phalanx was due to the cohesion of the hoplites during the impact, a cavalry attack from the flanks or from the rearguard was likely to disorganize the formation and make it vulnerable during the impact against another phalanx. It was the combination of phalanx and cavalry in the tactics of the hammer and the anvil that provided the decisive tactical advantage to the armies of Alexander the Great and that was the basis of the conquest of his immense empire.

Alexander, in his journey to the Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

, integrated into his army that of the defeated countries and was inspired by them to modify the equipment of his own forces.

Hammer and anvil tactics

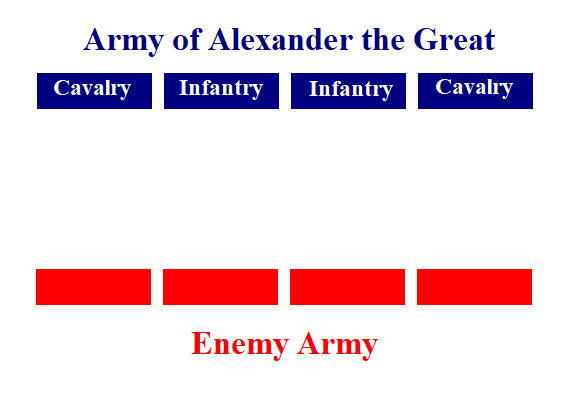

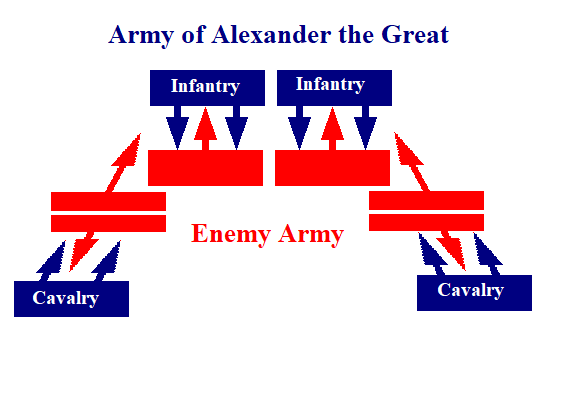

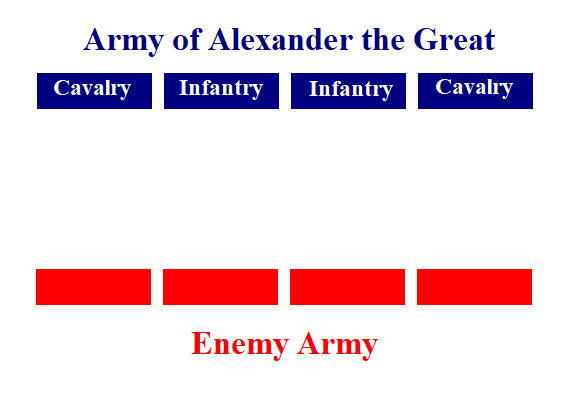

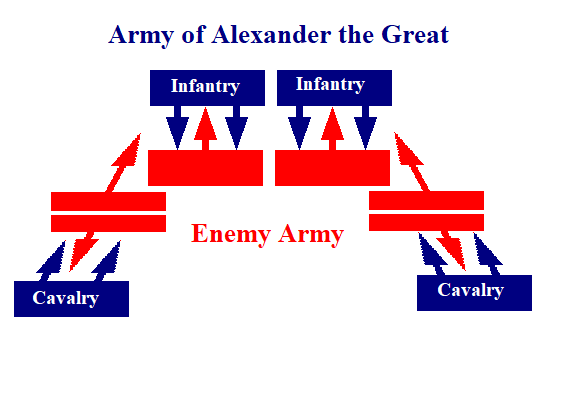

Principle

This tactic could not be carried out unless the two armies had more or less the same number of troops, since it consisted of enclosing the opponent on the sides. * The "anvil" corresponded to thephalanx

The phalanx ( grc, φάλαγξ; plural phalanxes or phalanges, , ) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar pole weapons. The term is particularly use ...

and the hypaspists

A hypaspist ( el, Ὑπασπιστής "shield bearer" or "shield covered") is a squire, man at arms, or "shield carrier". In Homer, Deiphobos advances "" () or under cover of his shield. By the time of Herodotus (426 BC), the word had come ...

(the elite infantry) that pressed the adversary and contained it in an enclosed space.

* The "hammer" corresponded to the heavy cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

of the hetairoi that intervened right after.

Phase 1: "The hammer"

In order to drive the enemy forces away from their center, the Macedonian cavalry surrounded the flanks of the opposing army, systematically on the right flank which was commanded by Alexander himself, and then tried to make a gap and position themselves in the enemy lines, thus forcing their enemies to regroup.

Phase 2: "The anvil"

Attacking from the flanks, the Macedonian cavalry surprised the enemy troops by the speed and force of its impact; in the center, the phalanx and the hypaspists advanced to open the second front. Once the enemy's way was closed, it was left in a trap. Generally, this caused great confusion because it could not be distinguished whether the units were dispersed or just poorly coordinated.

Battle of Gaugamela tactics

TheBattle of Gaugamela

The Battle of Gaugamela (; grc, Γαυγάμηλα, translit=Gaugámela), also called the Battle of Arbela ( grc, Ἄρβηλα, translit=Árbela), took place in 331 BC between the forces of the Army of Macedon under Alexander the Great a ...

was the decisive confrontation between Alexander's army and that of Darius III

Darius III ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; c. 380 – 330 BC) was the last Achaemenid King of Kings of Persia, reigning from 336 BC to his death in 330 BC.

Contrary to his predecessor Artaxerxes IV Arses, Dar ...

(October 1, 331 BC). It is also known as the Battle of Arbela, due to its relative proximity () to the city of Arbela, today's Erbil

Erbil, also called Hawler (, ar, أربيل, Arbīl; syr, ܐܲܪܒܹܝܠ, Arbel), is the capital and most populated city in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. It lies in the Erbil Governorate. It has an estimated population of around 1,600,000.

Hu ...

, in northern Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

.

Number of troops

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

had an army of 47,000 men, which was small compared to those of Darius—who according to modern historians assembled between 100,000 and 240,000 soldiers, maximum figure due to supply problems. The "hammer" and "anvil" tactics, which were the key to Alexander's victories until then, could no longer lead to victory, for it was indeed impossible to surround the entire Persian army.

Battle development

Levels disposition

In order not to be surrounded by the innumerable Persian cavalry, Alexander decided to arrange his troops in levels, something completely innovative at the time. Alexander took command of the right wing of the companion cavalry (''hetairoi''), while Darius III remained in the center, in the middle of his troops. To cover as much ground as possible, Alexander decided to lengthen his right flank. He advanced at a trot to be closely followed by his battalions of elite sharpshooters (foot soldiers equipped with slings or short-range spears), which Alexander had as support troops. This tactic served to make the Persian army unaware of his presence. The phalangists and the cavalry ofThessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

and Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

, placed on the left wing under the command of Parmenion

Parmenion (also Parmenio; grc-gre, Παρμενίων; c. 400 – 330 BC), son of Philotas, was a Macedonian general in the service of Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great. A nobleman, Parmenion rose to become Philip's chief milita ...

, had to hold their position for as long as possible.

Maximum ground coverage

Alexander's plan worked: troops A, B, and C (letters arbitrarily assigned to allow for quick definition) blocked their way, thus creating a gap in the Persian army. Making a quick about-face, Alexander turned around to head for the gap. The slingers and lancers, hitherto covered by the right wing of the cavalry, were uncovered and carried out their mission. On the other fronts, the cavalry of the left wing and Alexander's infantry nevertheless resisted the onslaught of the Persian chariots on the Macedonian center.

Darius retreat

The slingers and lancers attacked troops A, B and C to prevent them from performing their maneuvers. As these troops were destabilized, they lost formation. Alexander stepped into the breach and decided to go after Darius III, riding in his chariot and protected by the Royal Guard. When Darius saw what Alexander intended to do, he realized that he had no choice but to flee. His flight demoralized the troops. On the other fronts, the left wing and the phalanx began to show signs of weakness, since the troops attacking them did not hear the signal to retreat because they were in the midst of the heat of battle and far from the Persian king.

Darius persecution and death

As happened during thebattle of Issus

The Battle of Issus (also Issos) occurred in southern Anatolia, on November 5, 333 BC between the Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Empire, led by Darius III. It was the second great battle of Alexander's conquest of ...

, Alexander almost captured Darius, but the cavalry of the left wing was very weakened. Alexander then decided to let Darius go in order to save his army. Taking advantage of the situation in which the Macedonians found themselves, the Persian troops fled the battlefield with their leaders. Alexander was assured of victory, even though at the beginning of the battle his position was not favorable, but he was disappointed that he had not been able to capture or kill the Great King.

Darius fled with his guard of

Darius fled with his guard of Immortals

Immortality is the ability to live forever, or eternal life.

Immortal or Immortality may also refer to:

Film

* ''The Immortals'' (1995 film), an American crime film

* ''Immortality'', an alternate title for the 1998 British film ''The Wisdom of ...

and the Bactriana

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, southwe ...

cavalry. Alexander and his companions pursued them for . Seeing that Alexander was determined to capture Darius, a group of nobles, including the Bessi

The Bessi (; grc, Βῆσσοι, or , ) were a Thracian tribe that inhabited the upper valley of the Hebros and the lands between the Haemus and Rhodope mountain ranges in historical Thrace.

Geography

The exact geographic location of the Bes ...

, Barsaentes Barsaentes ( el, Βαρσαέντης, translit=Barsaéntēs) was a Persian nobleman, who served as the satrap of Arachosia and Drangiana under the Achaemenid King of Kings Darius III ().

Barsaentes took part in the Battle of Gaugamela against th ...

and Nabarzanes Nabarzanes (died ) was a high-ranking Persian commander, who served as the chiliarch of the royal cavalry of the Achaemenid King of Kings Darius III ().

Following the Persian defeat against the Macedonian king Alexander the Great () at the Batt ...

satraps

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with con ...

, took the Persian King hostage, so that they could make a pact with Alexander. However, they decided to assassinate and abandon him shortly before his arrival for fear that Alexander would not accept such a negotiation. Following this victory, Alexander was crowned as King of Asia in a lavish ceremony held in Arbela and upon his arrival in Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

.

See also

*Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

* Ancient Macedonian army

The army of the Kingdom of Macedon was among the greatest military forces of the ancient world. It was created and made formidable by King Philip II of Macedon; previously the army of Macedon had been of little account in the politics of the Gre ...

* Chronology of European exploration of Asia

This is a chronology of the early European exploration of Asia.

First wave of exploration (mainly by land)

Antiquity

* 515 BC: Scylax explores the Indus and the sea route across the Indian Ocean to Egypt.

* 330 BC: Alexander the Great conquers ...

References

{{reflistBibliography

* Antonis y Pavlo Georgakis, ''Arbèles'', Socomer, coll. «Les grandes batailles de l'histoire», 1989. * Sekunda, N. y Warry, J., ''Alexander the Great: His Armies and Campaigns 334-323 BC'', London, 1998. * Sekunda, N., The army of Alexander the Great, London, 1984. * Sekunda, N., ''The Persian army 560-330 BC'', London, 1992. * Ashley, J. R., ''The Macedonian empire. The era of warfare under Philip II and Alexander the Great 359-323BC'', London, 1998. * Brunt, P. A., «Alexander's Macedonian cavalry» en ''JHS'' 83, 1963. * Burn, A. R., ''The generalship of Alexander the Great'' en Greece and Rome 12, 1965. * Cassin-Scott, J., ''The Greek and Persian wars 500-323 BC'', London, 1977. * Devine, A. M., «Grand tactics at Gaugamela» en ''Phoenix'' 29, 1975. * Ellis, J. R., «Alexander's hypaspists again» en ''Historia'' 24, 1975. * Engels, D. W., ''Alexander the Great and the logistics of the Macedonian army'', Berkeley, 1978. * Engels, D., ''Alexander's intelligence system'' en CQ 30, 1980. * Fuller, J. F. C., ''The generalship of Alexander the Great'', London, 1958. * Griffith, G. T., «Alexander's generalship at Gaugamela» en ''JHS'' 67, 1947. * Griffith,G. T., «A note on the hipparchies of Alexander» en ''JHS'' 83, 1963. * Hamilton, J. R., «The cavalry battle at the Hydaspes» en ''JHS'' 76, 1956. * Hammond, N. G. L., «The battle of the Granicus river» en ''JHS'' 100, 1980. * Hammond, N. G. L., «The various guards of Philip II and Alexander III» en: ''Historia'' 40, 1991. * Hammond, N. G. L., «Alexander's charge at the battle of Issus in 333 BC» en ''Historia'' 41, 1992. * Hanson, V.D. (ed.), ''Hoplites: the classical Greek battle experience'', London, 1991. * Hanson, V. D., «Genesis of the infantry 600-350BC» en G. Parker (ed.), ''The Cambridge illustrated history of warfare. The triumph of the West'', Cambridge, 1995. * Head, D., ''The Achaemenid Persian army'', Stockworth, 1992. * Heckel, W., ''The somatophylakes of Alexander the Great: some notes'' en Historia 27, 1978. * Lock, R.A., ''The origins of the argyraspids'' en Historia 26, 1977. * Markle III, M.M., ''The Macedonian sarissa, spear and related armor'' en AJA 81, 1977. * Markle III, M.M., ''Use of the sarissa by Philip and Alexander of Macedon'' en AJA 82, 1978. * Markle III, M.M., ''Macedonian arms and tactics under Alexander the Great'' en B. Barr-Sharrar (ed.), Macedonia and Greece in late classical and early Hellenistic times, Washington, 1982. * Marsden, E.W., ''The campaign of Gaugamela'', Liverpool, 1964. * Milns, R.D., ''Alexander's Macedonian cavalry and Diodorus XVII 17.4'' en JHS 86 * Milns, R.D., ''Alexander's seventh phalanx battalion'' en GRBS 7, 1966. * Milns, R.D., ''Alexander's seventh phalanx battalion'' en GRBS 7, 1966. * Milns, R.D., ''The hypaspists of Alexander III - some problems'' en Historia 20, 1971. * Milns, R.D., ''The army of Alexander the Great'' en Fondations Hardt 22, 1976. * Neumann, C., ''A note on Alexander's march-rates'' en Historia 20, 1971. * Parke, H.W., ''Greek mercenary soldiers from the earliest times to the battle of Ipsus'' , Chicago, 1981. * Warry, J., ''Alexander 334-323 BC: conquest of the Persian empire'', London, 1991. * Worley, L.J., ''Hippeis. The cavalry of Ancient Greece'' Oxford, 1994. Alexander the Great Military tactics Military history of ancient Greece