Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

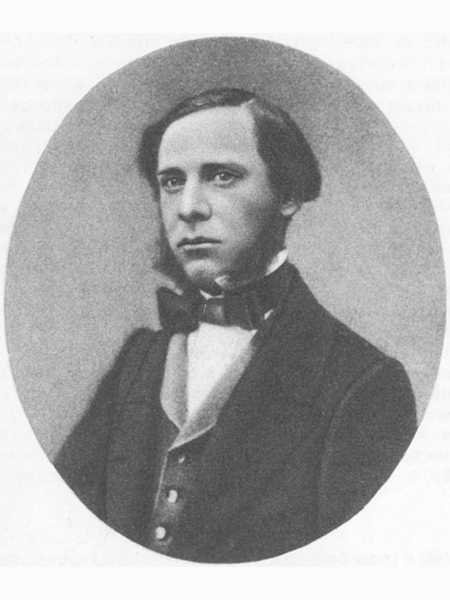

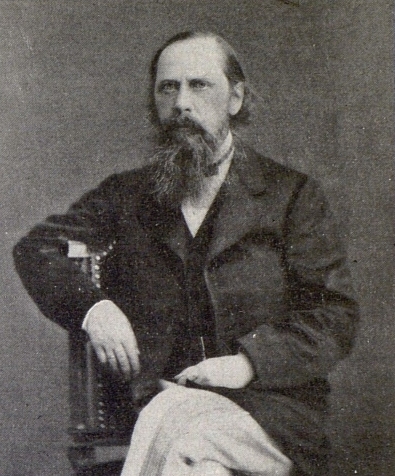

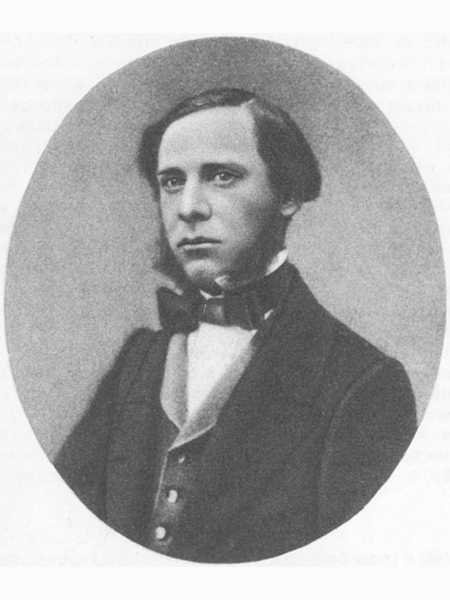

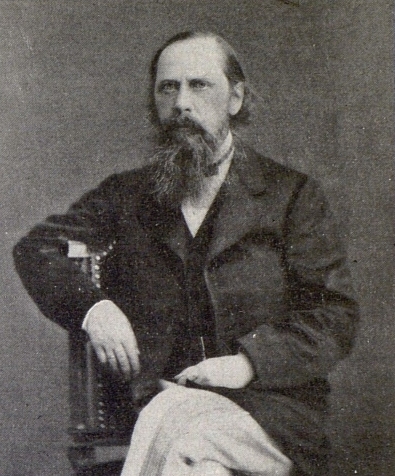

Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov-Shchedrin ( rus, Михаи́л Евгра́фович Салтыко́в-Щедри́н, p=mʲɪxɐˈil jɪvˈɡrafəvʲɪtɕ səltɨˈkof ɕːɪˈdrʲin; – ), born Mikhail Yevgrafovich Saltykov and known during his lifetime by the

Mikhail's early education was desultory, but, being an extraordinarily perceptive boy, by the age of six he spoke French and German fluently. He was taught to read and write Russian by the serf painter Pavel Sokolov and a local clergyman, and became an avid reader, later citing the

Mikhail's early education was desultory, but, being an extraordinarily perceptive boy, by the age of six he spoke French and German fluently. He was taught to read and write Russian by the serf painter Pavel Sokolov and a local clergyman, and became an avid reader, later citing the

М.S. М.Е.Saltykov-Shchedrin

The Selected Works. Critical and biographical essay. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow. 1954, pp. 5–24 While at the lyceum Saltykov started writing poetry and translated works from

In 1847 Saltykov debuted with his first novella ''Contradictions'' (under the pseudonym M.Nepanov), the title referring to the piece's main motif: the contrast between one's noble ideals and the horrors of real life. It was followed by ''A Complicated Affair'' (1848), a

In 1847 Saltykov debuted with his first novella ''Contradictions'' (under the pseudonym M.Nepanov), the title referring to the piece's main motif: the contrast between one's noble ideals and the horrors of real life. It was followed by ''A Complicated Affair'' (1848), a

In 1855 Tzar Nicholas I died and the climate in the country instantly changed. In November 1855 Saltykov received the permission to leave Vyatka, the new governor Lanskoy rumoured to be the major assisting force behind this. In January 1856 the writer returned to Saint Petersburg and in February was assigned to the Interior Ministry. By this time many of the stories and essays that would be known as ''Provincial Sketches'' have been written, a series of narratives about the fictitious town of Krutogorsk, shown as a symbol of Russian serfdom.

In 1855 Tzar Nicholas I died and the climate in the country instantly changed. In November 1855 Saltykov received the permission to leave Vyatka, the new governor Lanskoy rumoured to be the major assisting force behind this. In January 1856 the writer returned to Saint Petersburg and in February was assigned to the Interior Ministry. By this time many of the stories and essays that would be known as ''Provincial Sketches'' have been written, a series of narratives about the fictitious town of Krutogorsk, shown as a symbol of Russian serfdom.

In 1862 Saltykov retired from the government service and came to Moscow with the view of founding his own magazine there. The Ministry of Education's Special committee under the chairmanship of Prince D.A.Obolensky gave him no such permission. In the early 1863 Saltykov moved to Saint Petersburg to join Nekrasov's ''Sovremennik'', greatly undermined by the death of Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky's arrest. In this magazine he published first sketches of the ''Pompadours'' cycle and got involved with ''Svistok'' (The Whistle), a satirical supplement, using pseudonyms N.Shchedrin, K.Turin and Mikhail Zmiev-Mladentsev.

The series of articles entitled ''Our Social Life'' (1863–1864), examining “new tendencies in Russian

In 1862 Saltykov retired from the government service and came to Moscow with the view of founding his own magazine there. The Ministry of Education's Special committee under the chairmanship of Prince D.A.Obolensky gave him no such permission. In the early 1863 Saltykov moved to Saint Petersburg to join Nekrasov's ''Sovremennik'', greatly undermined by the death of Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky's arrest. In this magazine he published first sketches of the ''Pompadours'' cycle and got involved with ''Svistok'' (The Whistle), a satirical supplement, using pseudonyms N.Shchedrin, K.Turin and Mikhail Zmiev-Mladentsev.

The series of articles entitled ''Our Social Life'' (1863–1864), examining “new tendencies in Russian

On July 1, 1866, ''Sovremennik'' was closed. In the autumn Nekrasov approached the publisher

On July 1, 1866, ''Sovremennik'' was closed. In the autumn Nekrasov approached the publisher

''The Well-Meant Speeches'' (Благонамеренные речи, 1876) featured characters belonging to new Russian

''The Well-Meant Speeches'' (Благонамеренные речи, 1876) featured characters belonging to new Russian  In 1883, now critically ill, Saltykov published '' Modern Idyll'' (Современная идиллия), the novel he started in 1877–1878, targeting those of intelligentsia who were eager to prove their loyalty to the authorities. ''The Poshekhonye Stories'' (Пошехонские рассказы, 1883), ''Motley Letters'' (Пёстрые письма, 1884) and ''Unfinished Talks'' (Недоконченные беседы, 1886) followed, but by this time ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' were under increasing pressure from the censors, Shchedrin's prose being the latter's main target. The May 1874 issue with ''The Well-Meant Speeches'' has been destroyed, several other releases postponed for Saltykov's pieces to be excised. In 1874-1879 ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' suffered 18 censorial sanctions, all having to do with Shchedrin's work, most of which (''Well-Meant Speeches'', ''Letters to Auntie'', many fairytales) were banned. "It is despicable times that we are living through... and it takes a lot of strength not to give up," Saltykov wrote.

The demise of ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' in 1884 dealt Saltykov a heavy blow. "The possibility to talk with my readers has been taken away from me and this pain is stronger than any other," he complained. "The whole of the Russian press suffered from the ''Otechestvenny Zapiski''s closure… Where there's been a lively tissue now there is a chasm of emptiness. And Shchedrin's life has been curtailed, probably, for many years, by this 'excision'," wrote Korolenko in 1889. Saltykov-Shchedrin's last works were published by ''

In 1883, now critically ill, Saltykov published '' Modern Idyll'' (Современная идиллия), the novel he started in 1877–1878, targeting those of intelligentsia who were eager to prove their loyalty to the authorities. ''The Poshekhonye Stories'' (Пошехонские рассказы, 1883), ''Motley Letters'' (Пёстрые письма, 1884) and ''Unfinished Talks'' (Недоконченные беседы, 1886) followed, but by this time ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' were under increasing pressure from the censors, Shchedrin's prose being the latter's main target. The May 1874 issue with ''The Well-Meant Speeches'' has been destroyed, several other releases postponed for Saltykov's pieces to be excised. In 1874-1879 ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' suffered 18 censorial sanctions, all having to do with Shchedrin's work, most of which (''Well-Meant Speeches'', ''Letters to Auntie'', many fairytales) were banned. "It is despicable times that we are living through... and it takes a lot of strength not to give up," Saltykov wrote.

The demise of ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' in 1884 dealt Saltykov a heavy blow. "The possibility to talk with my readers has been taken away from me and this pain is stronger than any other," he complained. "The whole of the Russian press suffered from the ''Otechestvenny Zapiski''s closure… Where there's been a lively tissue now there is a chasm of emptiness. And Shchedrin's life has been curtailed, probably, for many years, by this 'excision'," wrote Korolenko in 1889. Saltykov-Shchedrin's last works were published by ''

Mikhail Bulgakov was among writers, influenced by Saltykov.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin is regarded to be the most prominent satirist in the history of the Russian literature. According to critic and biographer Maria Goryachkina, he's managed to compile "the satirical encyclopedia" of contemporary Russian life, targeting first serfdom with its degrading effect upon the society, then, after its abolition, - corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, opportunistic tendencies in intelligentsia, greed and amorality of those at power, but also - apathy, meekness and social immobility of the common people of Russia. His satirical cycle ''Fables'' and the two major works, ''

Mikhail Bulgakov was among writers, influenced by Saltykov.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin is regarded to be the most prominent satirist in the history of the Russian literature. According to critic and biographer Maria Goryachkina, he's managed to compile "the satirical encyclopedia" of contemporary Russian life, targeting first serfdom with its degrading effect upon the society, then, after its abolition, - corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, opportunistic tendencies in intelligentsia, greed and amorality of those at power, but also - apathy, meekness and social immobility of the common people of Russia. His satirical cycle ''Fables'' and the two major works, '' Most works of Saltykov's later period were written in a language that the satirist himself called Aesopian. This way, though, the writer was able to fool censors in the times of political oppression and take most radical ideas to print, which was the matter of his pride. "It is one continuous circumlocution because of censorship and requires a constant reading commentary," Mirsky argued. The use of Aesopic language was one reason why Saltykov-Shchedrin has never achieved as much acclaim in the West as had three of his great contemporaries, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, according to

Most works of Saltykov's later period were written in a language that the satirist himself called Aesopian. This way, though, the writer was able to fool censors in the times of political oppression and take most radical ideas to print, which was the matter of his pride. "It is one continuous circumlocution because of censorship and requires a constant reading commentary," Mirsky argued. The use of Aesopic language was one reason why Saltykov-Shchedrin has never achieved as much acclaim in the West as had three of his great contemporaries, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, according to

''The Village Priest and Other Stories from the Russian of Militsina & Saltikov'', T. Fisher Unwin, 1918

*''The Pompadours: A Satire on the Art of Government'', Ardis, 1982.

''The Humour of Russia'', London : W. Scott, 1895

''A Family of Noblemen (The Golovlyov Family)''

at the Internet Archive (translation by Avrahm Yarmolinsky)

''The Golovlyov Family''

at the Internet Archive (translation by Natalie Duddington)

''The Village Priest and Other Stories''

from the Russian of Militsina & Saltikov at the Internet Archive

''Tchinovnicks (Provincial Sketches)'' at Google books

Grave of M.Saltykov

{{DEFAULTSORT:Saltykov-Shchedrin, Mikhail 1826 births 1889 deaths People from Taldomsky District People from Kalyazinsky Uyezd Russian nobility Russian male novelists Journalists from the Russian Empire Male writers from the Russian Empire Russian satirists Russian male short story writers Russian civil servants Russian dramatists and playwrights Russian male dramatists and playwrights Russian fabulists Russian editors Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum alumni 19th-century journalists Russian male journalists 19th-century translators from the Russian Empire 19th-century novelists from the Russian Empire 19th-century dramatists and playwrights from the Russian Empire 19th-century short story writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire 19th-century pseudonymous writers

pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

Nikolai Shchedrin ( rus, Николай Щедрин), was a major Russian writer and satirist

This is an incomplete list of writers, cartoonists and others known for involvement in satire – humorous social criticism. They are grouped by era and listed by year of birth. Included is a list of modern satires.

Under Contemporary, 1930-196 ...

of the 19th century. He spent most of his life working as a civil servant in various capacities. After the death of poet Nikolay Nekrasov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov ( rus, Никола́й Алексе́евич Некра́сов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪtɕ nʲɪˈkrasəf, a=Ru-Nikolay_Alexeyevich_Nekrasov.ogg, – ) was a Russian poet, writer, critic and publi ...

, he acted as editor of a Russian literary magazine ''Otechestvenniye Zapiski

''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' ( rus, Отечественные записки, p=ɐˈtʲetɕɪstvʲɪnːɨjɪ zɐˈpʲiskʲɪ, variously translated as "Annals of the Fatherland", "Patriotic Notes", "Notes of the Fatherland", etc.) was a Russian lite ...

'' until the Tsarist government banned it in 1884. In his works Saltykov mastered both stark realism and satirical grotesque merged with fantasy. His most famous works, the family chronicle novel ''The Golovlyov Family

''The Golovlyov Family'' (russian: Господа Головлёвы, translit=Gospoda Golovlyovy; also translated as ''The Golovlevs'' or ''A Family of Noblemen: The Gentlemen Golovliov'') is a novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, written in the ...

'' (1880) and the political novel ''The History of a Town

''The History of a Town'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, История одного города, Istoriya odnogo goroda) is a 1870 novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. The plot presents the history of the town of Glupov (can be transl ...

'' (1870) became important works of 19th-century fiction

Fiction is any creative work, chiefly any narrative work, portraying individuals, events, or places that are imaginary, or in ways that are imaginary. Fictional portrayals are thus inconsistent with history, fact, or plausibility. In a traditi ...

, and Saltykov is regarded as a major figure of Russian literary Realism.

Biography

Mikhail Saltykov was born on 27 January 1826 in the village of Spas-Ugol (modern-dayTaldomsky District

Taldomsky District (russian: Талдомский район) was an administrativeLaw #11/2013-OZ and municipalLaw #42/2005-OZ district (raion) in Moscow Oblast, Russia.

At 2019, it was located in the north of the oblast and bordered with Tver Obl ...

of the Moscow Oblast

Moscow Oblast ( rus, Моско́вская о́бласть, r=Moskovskaya oblast', p=mɐˈskofskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ), or Podmoskovye ( rus, Подмоско́вье, p=pədmɐˈskovʲjə, literally "under Moscow"), is a federal subject of Rus ...

of Russia) as one of the eight children (five brothers and three sisters) in the large Russian noble family of Yevgraf Vasilievich Saltykov (1776–1851) and Olga Mikhaylovna Saltykova (née Zabelina; 1801–74). His father belonged to an ancient Saltykov noble house that originated as one of the branches of the Morozov boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the Feudalism, feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgarian Empire, Bulgaria, Russian nobility, Russia, Boyars of Moldavia and Wallachia, Wallachia and ...

family. According to the Velvet Book

The Velvet Book (russian: Бархатная книга, Barkhatnaya kniga) was an official register of genealogies of Russia's most noble families (Russian nobility). The book is bound in red velvet, hence the name.

, it was founded by Mikhail Ignatievich Morozov nicknamed Saltyk (from the Old Church Slavonic

Old Church Slavonic or Old Slavonic () was the first Slavic languages, Slavic literary language.

Historians credit the 9th-century Byzantine Empire, Byzantine missionaries Saints Cyril and Methodius with Standard language, standardizing the lan ...

word "saltyk" meaning "one's own way/taste"), the son of Ignaty Mikhailovich Morozov and a great-grandson of the founder of the dynasty Ivan Semyonovich Moroz who lived during the 14–15th centuries. The Saltykov family also shared the Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

Sołtyk coat of arms

Sołtyk - is a Polish coat of arms. It was used by several szlachta families in the times of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

History

Blazon

Notable bearers

Notable bearers of this coat of arms include:

* Tomasz Sołtyk

* Kajeta ...

. It gave birth to many important political figures throughout history, including the tsaritsa

Tsarina or tsaritsa (also spelled ''csarina'' or ''csaricsa'', ''tzarina'' or ''tzaritza'', or ''czarina'' or ''czaricza''; bg, царица, tsaritsa; sr, / ; russian: царица, tsaritsa) is the title of a female autocratic ruler (mon ...

of Russia Praskovia Saltykova

Praskovia Fyodorovna Saltykova (russian: Прасковья Фёдоровна Салтыкова; 12 October 1664 – 13 October 1723) was the tsaritsa of Russia as the only wife of joint-Tsar Ivan V of Russia. She was the mother of Empress Anna ...

and her daughter, the Empress of Russia Anna Ioannovna

Anna Ioannovna (russian: Анна Иоанновна; ), also russified as Anna Ivanovna and sometimes anglicized as Anne, served as regent of the duchy of Courland from 1711 until 1730 and then ruled as Empress of Russia from 1730 to 1740. Much ...

.

Saltykov's mother was an heir to a rich Moscow merchant of the 1st level guild Mikhail Petrovich Zabelin whose ancestors belonged to the so-called trading peasants and who was granted hereditary nobility for his handsome donation to the army needs in 1812; his wife Marfa Ivanovna Zabelina also came from wealthy Moscow merchants.''Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin (1975)''. Collection of Works in 20 Volumes. Volume 17. Leningrad: Khudozhestvennaya Literatura

Khudozhestvennaya Literatura (russian: Художественная литература) is a publishing house in Saint Petersburg, Russia. The name means "fiction literature" in Russian. It specializes in the publishing of Russian and foreign wor ...

, p. 548, 9 At the time of Mikhail Saltykov's birth, Yevgraf was fifty years old, while Olga was twenty five. Mikhail spent his early years on his parents' large estate in Spasskoye on the border of the Tver and Yaroslavl

Yaroslavl ( rus, Ярослáвль, p=jɪrɐˈsɫavlʲ) is a city and the administrative center of Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, located northeast of Moscow. The historic part of the city is a World Heritage Site, and is located at the confluence ...

governorates, in the Poshekhonye

Poshekhonye (russian: Пошехо́нье) is a town and the administrative center of Poshekhonsky District in Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, located on the Sogozha River, northwest of Yaroslavl, the administrative center of the oblast. Population:

...

region.

"In my childhood and teenage years I witnessed serfdom at its worst. It saturated all strata of social life, not just the landlords and the enslaved masses, degrading all classes, privileged or otherwise, with its atmosphere of a total lack of rights, when fraud and trickery were the order of the day, and there was an all-pervading fear of being crushed and destroyed at any moment," he remembered, speaking through one of the characters of his later novel ''Old Years in Poshekhonye''. Life in the Saltykov family was equally difficult. Dominating the weak, religious father was despotic mother whose intimidating persona horrified the servants and her own children. This atmosphere was later recreated in Shchedrin's novel ''The Golovlyov Family'', and the idea of "the devastating effect of legalized slavery upon the human psyche" would become one of the prominent motifs of his prose. Olga Mikhaylovna, though, was a woman of many talents; having perceived some in Mikhail, she treated him as her favorite.

The Saltykovs often quarreled; they gave their children neither love nor care and Mikhail, despite enjoying relative freedom in the house, remembered feeling lonely and neglected. Another thing Saltykov later regretted was his having been completely shut out from nature in his early years: the children lived in the main house and were rarely allowed to go out, knowing their "animals and birds only as boiled and fried." Characteristically, there were few descriptions of nature in the author's works.

Education

Mikhail's early education was desultory, but, being an extraordinarily perceptive boy, by the age of six he spoke French and German fluently. He was taught to read and write Russian by the serf painter Pavel Sokolov and a local clergyman, and became an avid reader, later citing the

Mikhail's early education was desultory, but, being an extraordinarily perceptive boy, by the age of six he spoke French and German fluently. He was taught to read and write Russian by the serf painter Pavel Sokolov and a local clergyman, and became an avid reader, later citing the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

, which he read at the age of eight, as a major influence. Among his childhood friends was Sergey Yuriev, the son of a neighbouring landlord and later a prominent literary figure, editor and publisher of the magazines '' Russkaya Mysl'' and ''Beseda''. In 1834 his elder sister Nadezhda graduated from the Moscow Ekaterininsky college, and Mikhail's education from then on was the prerogative of her friend Avdotya Vasilevskaya, a graduate of the same institute who had been invited to the house as a governess. Mikhail's other tutors included the local clergyman Ivan Vasilievich who taught the boy Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and the student Matvey Salmin.

At the age of ten Saltykov joined the third class of the Moscow Institute for sons of the nobility (Dvoryansky institute), skipping the first two classes, where he studied until 1838. He then enrolled in the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum in Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, spending the next six years there. Prince Aleksey Lobanov-Rostovsky

Prince Aleksey Borisovich Lobanov-Rostovsky (russian: Князь Алексе́й Бори́сович Лоба́нов-Росто́вский) ( in Voronezh Governorate – ) was a Russian statesman, probably best remembered for having conclude ...

, afterwards the Minister Of Foreign Affairs, was one of his schoolfellows. In the lyceum the quality of education was poor. "The information taught to us was scant, sporadic and all but meaningless… It was not so much an education as such, but a part of social privilege, the one that draws the line through life: above are you and me, people of leisure and power, beneath – just one single word: muzhik

Agriculture in the Russian Empire throughout the 19th-20th centuries Russia represented a major world force, yet it lagged technologically behind other developed countries. Imperial Russia (officially founded in 1721 and abolished in 1917) was am ...

," Saltykov wrote in his ''Letters to Auntie''.GoryachkinaМ.S. М.Е.Saltykov-Shchedrin

The Selected Works. Critical and biographical essay. Khudozhestvennaya Literatura Publishers. Moscow. 1954, pp. 5–24 While at the lyceum Saltykov started writing poetry and translated works from

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824), known simply as Lord Byron, was an English romantic poet and Peerage of the United Kingdom, peer. He was one of the leading figures of the Romantic movement, and h ...

and Heinrich Heine. He was proclaimed an 'heir to Pushkin' – after the local tradition which demanded that each course should have one. His first poem, "The Lyre", a hymn to the great Russian poet, was published by ''Biblioteka Dlya Chteniya

''Biblioteka Dlya Chteniya'' (russian: Библиоте́ка для чте́ния, en, The Reader's Library) was a Russian monthly magazine founded in Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire, in 1834 by Alexander Smirdin.

History

The magazine "of lit ...

'' in 1841. Eight more of Saltykov's verses made their way into ''Sovremennik

''Sovremennik'' ( rus, «Современник», p=səvrʲɪˈmʲenʲːɪk, a=Ru-современник.ogg, "The Contemporary") was a Russian literary, social and political magazine, published in Saint Petersburg in 1836–1866. It came out f ...

'' in 1844–45. At the time he was attending Mikhail Yazykov's literary circle, which was occasionally visited by Vissarion Belinsky

Vissarion Grigoryevich Belinsky ( rus, Виссарион Григорьевич БелинскийIn Belinsky's day, his name was written ., Vissarión Grigórʹjevič Belínskij, vʲɪsərʲɪˈon ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲjɪvʲɪdʑ bʲɪˈlʲinskʲ ...

. The latter's articles and essays made a great impression on Mikhail.

Upon graduating the Lyceum in 1844, Saltykov, who was one of the best students, was promoted directly to the chancellery of the Ministry of Defense. This success upset Mikhail, as it ended his dream of attending Saint Petersburg University

Saint Petersburg State University (SPBU; russian: Санкт-Петербургский государственный университет) is a public research university in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Founded in 1724 by a decree of Peter the G ...

. The same year he became involved with ''Otechestvennye zapiski

''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' ( rus, Отечественные записки, p=ɐˈtʲetɕɪstvʲɪnːɨjɪ zɐˈpʲiskʲɪ, variously translated as "Annals of the Fatherland", "Patriotic Notes", "Notes of the Fatherland", etc.) was a Russian lite ...

'' and ''Sovremennik'', reviewing for both magazines children's literature and textbooks. His criticism was sharp, and Belinsky's influence on it was evident. At this time Saltykov became a follower of the Socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

ideas coming from France. "Brought up by Belinsky's articles, I naturally drifted towards the Westernizers

Westernizers (; russian: За́падник, Západnik, p=ˈzapədnʲɪk) were a group of 19th-century intellectuals who believed that Russia's development depended upon the adoption of Western European technology and liberal government. In their v ...

' camp, but not to the major trend of it which was dominant in Russian literature at the time, promoting German philosophy

German philosophy, here taken to mean either (1) philosophy in the German language or (2) philosophy by Germans, has been extremely diverse, and central to both the analytic and continental traditions in philosophy for centuries, from Gottfried ...

, but to this tiny circle that felt instinctively drawn towards France - the country of Saint-Simon, Fourier... and, in particular, George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. One of the most popular writers in Europe in her lifetime, bein ...

... Such sympathies only grew stronger after 1848," he later remembered. Saltykov befriended literary critic Valerian Maykov

Valerian Nikolayevich Maykov (russian: Валериа́н Никола́евич Ма́йков, September 9, 1823, Moscow, Russia — July 27, 1847, v.Novoye) was a Russian writer and literary critic, son of painter Nikolay Maykov, brother of po ...

and economist and publicist Vladimir Milyutin, and became close to the Petrashevsky circle

The Petrashevsky Circle was a Russian literary discussion group of progressive-minded intellectuals in St. Petersburg in the 1840s. It was organized by Mikhail Petrashevsky, a follower of the French utopian socialist Charles Fourier. Among the mem ...

. "How easily we lived and what deep faith we had in the future, what single-mindedness and unity of hopes there was, giving us life!" he later remembered, calling Mikhail Petrashevsky

Mikhail Vasilyevich Butashevich-Petrashevsky (; – ), commonly known as Mikhail Petrashevsky, was a Russian revolutionary and Utopian theorist.Figes, p. 128

Biography Early life

Mikhail Petrashevsky graduated from the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum (18 ...

"a dear, unforgettable friend and teacher."

Literary career

social novel

The social novel, also known as the social problem (or social protest) novel, is a "work of fiction in which a prevailing social problem, such as gender, race, or class prejudice, is dramatized through its effect on the characters of a novel". Mor ...

la, reminiscent of Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

, both in its plotlines and the natures of its characters, dealing with social injustice and the inability of an individual to cope with social issues. The novella was praised by Nikolai Dobrolyubov

Nikolay Alexandrovich Dobrolyubov ( rus, Никола́й Алекса́ндрович Добролю́бов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɐlʲɪˈksandrəvʲɪtɕ dəbrɐˈlʲubəf, a=Nikolay Alyeksandrovich Dobrolyubov.ru.vorb.oga; 5 February Old_Style_a ...

who wrote: "It is full of heartfelt sympathy for destitute men... awakening in one humane feelings and manly thoughts," and Nikolai Chernyshevsky

Nikolay Gavrilovich Chernyshevsky ( – ) was a Russian literary and social critic, journalist, novelist, democrat, and socialist philosopher, often identified as a utopian socialist and leading theoretician of Russian nihilism. He was ...

, who referred to it as a book "that has created a stir and is of much interest to people of the new generation." It was the publication of ''Contradictions'' that caused Saltykov's banishment to Vyatka, - apparently the result of overreaction from the authorities in response to the French Revolution of 1848. On 26 April 1848, Tsar Nicholas I signed the order for the author's arrest and deportation.

In his first few months of exile Saltykov was mainly occupied with copying official documents. Then he was made a special envoy of the Vyatka governor; his major duty in this capacity was making inquiries concerning brawls, cases of minor bribery, embezzlement and police misdoings. Saltykov made desperate attempts to break free from what he called his 'Vyatka captivity', but after each of his requests he received the standard reply: "would be premature." He became more and more aware of the possibility that he'd have to spend the rest of his life there. "The very thought of that is so repellent that it makes by hair bristle," he complained in a letter to his brother. It helped that the local elite treated Saltykov with great warmth and sympathy; he was made a welcome guest in many respectable houses, including that of vice-governor Boltin whose daughter Elizaveta Apollonovna later became Saltykov's wife.

While in Vyatka Saltykov got carried away by the idea of radically improving the quality of education for young women and girls. There were no decent history textbooks at the time in Russia, so he decided to write one himself. Called ''A Brief History of Russia'', it amounted to 40 handwritten pages of compact text compiled from numerous sources. He worked on it while on vacation in a village near Tver, sending it to Vyatka to be published as a series.

As the numerous members of the Petrashevsky Circle were arrested in 1848, Saltykov got summoned to the capital to give evidence on his involvement in the group's activity. There he managed to convince the authorities that 'spreading harm' was not his intention and safely returned to Vyatka. In the summer of 1850 he became a councillor of the local government which implied long voyages through the province on official business, many of them having to do with issues concerning the Old Believers. As an investigator, he traveled throughout the Vyatka, Perm

Perm or PERM may refer to:

Places

*Perm, Russia, a city in Russia

** Permsky District, the district

**Perm Krai, a federal subject of Russia since 2005

**Perm Oblast, a former federal subject of Russia 1938–2005

**Perm Governorate, an administra ...

, Kazan

Kazan ( ; rus, Казань, p=kɐˈzanʲ; tt-Cyrl, Казан, ''Qazan'', IPA: ɑzan is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Tatarstan in Russia. The city lies at the confluence of the Volga and the Kazanka rivers, covering a ...

, Nizhny Novgorod

Nizhny Novgorod ( ; rus, links=no, Нижний Новгород, a=Ru-Nizhny Novgorod.ogg, p=ˈnʲiʐnʲɪj ˈnovɡərət ), colloquially shortened to Nizhny, from the 13th to the 17th century Novgorod of the Lower Land, formerly known as Gork ...

and Yaroslavl

Yaroslavl ( rus, Ярослáвль, p=jɪrɐˈsɫavlʲ) is a city and the administrative center of Yaroslavl Oblast, Russia, located northeast of Moscow. The historic part of the city is a World Heritage Site, and is located at the confluence ...

governorates. In 1850 he became the organizer of the Vyatka agricultural exhibition, one of the largest in the country. All this provided Saltykov with priceless material for his future satires.

''Provincial Sketches''

In 1855 Tzar Nicholas I died and the climate in the country instantly changed. In November 1855 Saltykov received the permission to leave Vyatka, the new governor Lanskoy rumoured to be the major assisting force behind this. In January 1856 the writer returned to Saint Petersburg and in February was assigned to the Interior Ministry. By this time many of the stories and essays that would be known as ''Provincial Sketches'' have been written, a series of narratives about the fictitious town of Krutogorsk, shown as a symbol of Russian serfdom.

In 1855 Tzar Nicholas I died and the climate in the country instantly changed. In November 1855 Saltykov received the permission to leave Vyatka, the new governor Lanskoy rumoured to be the major assisting force behind this. In January 1856 the writer returned to Saint Petersburg and in February was assigned to the Interior Ministry. By this time many of the stories and essays that would be known as ''Provincial Sketches'' have been written, a series of narratives about the fictitious town of Krutogorsk, shown as a symbol of Russian serfdom. Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

who happened to read them first was unimpressed and, following his advice (and bearing in mind still fierce censorship) Nikolai Nekrasov

Nikolay Alexeyevich Nekrasov ( rus, Никола́й Алексе́евич Некра́сов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪtɕ nʲɪˈkrasəf, a=Ru-Nikolay_Alexeyevich_Nekrasov.ogg, – ) was a Russian poet, writer, critic and publi ...

refused to publish the work in ''Sovremennik''. In August 1856 Mikhail Katkov

Mikhail Nikiforovich Katkov (russian: Михаи́л Ники́форович Катко́в; 13 February 1818 – 1 August 1887) was a conservative Russian journalist influential during the reign of tsar Alexander III. He was a proponent of Rus ...

’s ''The Russian Messenger

The ''Russian Messenger'' or ''Russian Herald'' (russian: Ру́сский ве́стник ''Russkiy Vestnik'', Pre-reform Russian: Русскій Вѣстникъ ''Russkiy Vestnik'') has been the title of three notable magazines published in ...

'' started publishing ''Provincial Sketches'', signed N.Shchedrin. The book, charged with anti-serfdom pathos and full of scathing criticism of provincial bureaucracy became instant success and made Saltykov famous. Many critics and colleagues called him the heir to Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; uk, link=no, Мико́ла Васи́льович Го́голь, translit=Mykola Vasyliovych Hohol; (russian: Яновский; uk, Яновський, translit=Yanovskyi) ( – ) was a Russian novelist, ...

. "I’m in awe... Oh immortal Gogol, you must now be a happy man now to see such a genius emerging as your follower," Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko ( uk, Тарас Григорович Шевченко , pronounced without the middle name; – ), also known as Kobzar Taras, or simply Kobzar (a kobzar is a bard in Ukrainian culture), was a Ukrainian poet, wr ...

wrote in his diary. In 1857 ''Sovremennik'' at last reacted: both Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky rather belatedly praised Saltykov, characteristically, imparting to his work what it's never had: "aiming at the undermining the Empire's foundations."

In 1857 ''The Russian Messenger'' published ''Pazukhin's Death'', a play which was quite in tune with ''Provincial Sketches''. The production of it was banned with characteristic verdict of censors: "Characters presented there are set to prove our society lies in the state of total moral devastation." Another of Saltykov's plays, ''Shadows'' (1862–1865), about careerism and immorality of bureaucracy, has been discovered in archives and published only in 1914, when it was premiered on stage too.

Contrary to left radicals' attempt to draw Saltykov closer to their camp, "undermining the Empire's foundations" was not his aim at all and on his return to Saint Petersburg he was soon promoted to administrative posts of considerable importance. His belief was that "all honest men should help the government in defeating serfdom apologist still clinging to their rights." Huge literary success has never made him think of retiring from work in the government. Partly reasons for his return to the state service were practical. In 1856 Saltykov married Elizaveta Boltina, daughter of a Vyatka vice-governor and found, on the one hand, his mother's financial support curtailed, on the other, his own needs risen sharply. Up until 1858 Saltykov continued working in the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Then after making a report on the condition of the Russian police

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and t ...

, he was appointed deputy governor of Ryazan

Ryazan ( rus, Рязань, p=rʲɪˈzanʲ, a=ru-Ryazan.ogg) is the largest city and administrative center of Ryazan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the banks of the Oka River in Central Russia, southeast of Moscow. As of the 2010 Census ...

where later he's got a nickname "the vice- Robespierre". On April 15, 1858, Saltykov arrived to Ryazan very informally, in an ordinary road carriage, which amazed the local 'society' for whom he'd been known already as ''Provincial Sketches'' author. He settled in a small house, often visited people and received guests. Saltykov's primary goal was to teach local minor officials elementary grammar and he spent many late evenings proof-reading and re-writing their incongruous reports. In 1862 Saltykov was transferred to Tver where he often performed governor's functions. Here Saltykov proved to be a zealous promoter of the 1861 reforms. He personally sued several landowners accusing them of cruel treatment of peasants.

All the while his literary activities continued. In 1860-1862 he wrote and published (mostly, in ''Vremya'' magazine) numerous sketches and short stories, some later included into ''Innocent Stories'' (1857–1863) which demonstrated what Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

later called a "talent for talking politics through domesticities" and ''Satires In Prose'' (1859–1862) where for the first time the author seemed to be quite vexed with the apathy of the oppressed. "One is hardly to be expected to engage oneself in self-development when one's only thought revolves around just one wish: not to die of hunger," he later explained. Many of Saltykov's articles on agrarian reforms were also written in those three years, mostly in ''Moskovskye Vedomosty'', where his major opponent was journalist Vladimir Rzhevsky.

''Sovremennik''

In 1862 Saltykov retired from the government service and came to Moscow with the view of founding his own magazine there. The Ministry of Education's Special committee under the chairmanship of Prince D.A.Obolensky gave him no such permission. In the early 1863 Saltykov moved to Saint Petersburg to join Nekrasov's ''Sovremennik'', greatly undermined by the death of Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky's arrest. In this magazine he published first sketches of the ''Pompadours'' cycle and got involved with ''Svistok'' (The Whistle), a satirical supplement, using pseudonyms N.Shchedrin, K.Turin and Mikhail Zmiev-Mladentsev.

The series of articles entitled ''Our Social Life'' (1863–1864), examining “new tendencies in Russian

In 1862 Saltykov retired from the government service and came to Moscow with the view of founding his own magazine there. The Ministry of Education's Special committee under the chairmanship of Prince D.A.Obolensky gave him no such permission. In the early 1863 Saltykov moved to Saint Petersburg to join Nekrasov's ''Sovremennik'', greatly undermined by the death of Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky's arrest. In this magazine he published first sketches of the ''Pompadours'' cycle and got involved with ''Svistok'' (The Whistle), a satirical supplement, using pseudonyms N.Shchedrin, K.Turin and Mikhail Zmiev-Mladentsev.

The series of articles entitled ''Our Social Life'' (1863–1864), examining “new tendencies in Russian nihilism

Nihilism (; ) is a philosophy, or family of views within philosophy, that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, such as objective truth, knowledge, morality, values, or meaning. The term was popularized by Ivan ...

,” caused a raw with equally radical '' Russkoye Slovo''. First Saltykov ridiculed Dmitry Pisarev

Dmitry Ivanovich Pisarevrussian: Дми́трий Ива́нович Пи́сарев ( – ) was a Russian literary critic and philosopher who was a central figure of Russian nihilism. He is noted as a forerunner of Nietzschean philosophy and ...

's unexpected call for Russian intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

to pay more attention to natural sciences. Then in 1864 Pisarev responded by "Flowers of Innocent Humor" article published by ''Russkoye Slovo'' implying that Saltykov was cultivating "laughter for good digestion's sake". The latter's reply contained accusations in isolationism and elitism

Elitism is the belief or notion that individuals who form an elite—a select group of people perceived as having an intrinsic quality, high intellect, wealth, power, notability, special skills, or experience—are more likely to be constructi ...

. All this (along with heated discussion of Chernyshevsky's novel ''What Is to Be Done?

''What Is to Be Done? Burning Questions of Our Movement'' is a political pamphlet written by Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin (credited as N. Lenin) in 1901 and published in 1902. Lenin said that the article represented "a skeleton plan t ...

'') was termed "raskol

The Schism of the Russian Church, also known as Raskol (russian: раскол, , meaning "split" or "schism"), was the splitting of the Russian Orthodox Church into an official church and the Old Believers movement in the mid-17th century. It ...

in Russian nihilism" by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

.

On the other front, Saltykov waged a war against the Dostoyevsky brothers’ ''Grazhdanin'' magazine. When Fyodor Dostoyevsky came out with the suggestion that with Dobrolyubov's death and Chernyshevsky's imprisonment the radical movement in Russia became lifeless and dogmatic, Saltykov labeled him and his fellow pochvennik

''Pochvennichestvo'' (; rus, Почвенничество, p=ˈpot͡ɕvʲɪnnʲɪt͡ɕɪstvə, roughly "return to the native soil", from почва "soil") was a late 19th-century movement in Russia that tied in closely with its contemporary i ...

s 'reactionaries'. Finally, the rift between him and Maxim Antonovich (supported by Grigory Eliseev

Grigory Zakharovich Eliseev (russian: Григо́рий Заха́рович Елисе́ев, 6 February (25 January) 1821, village Spasskoe, Kainsk district, Tomsk Governorate, Russian Empire – 30 (18) January 1891, Saint Petersburg, Russian ...

) made Saltykov-Schedrin quit the journal. Only a small part of stories and sketches that Saltykov wrote at the time has made its way into his later books (''Innocent Stories'', ''Sign of the Time'', ''Pompadours'').

Being dependent on his ''Sovremennik''s meagre salaries, Saltykov was looking for work on the side and quarreled with Nekrasov a lot, promising to quit literature. According to Avdotya Panayeva's memoirs, "those were the times when his moods darkened, and I noticed a new habit of his developing - this jerky movement of neck, as if he was trying to free himself from some unseen tie, the habit which stayed with him for the rest of his life." Finally, pecuniary difficulties compelled Saltykov to re-enter the governmental service and in November 1864 he was appointed the head of the treasury

A treasury is either

*A government department related to finance and taxation, a finance ministry.

*A place or location where treasure, such as currency or precious items are kept. These can be state or royal property, church treasure or i ...

department in Penza

Penza ( rus, Пе́нза, p=ˈpʲɛnzə) is the largest city and administrative center of Penza Oblast, Russia. It is located on the Sura River, southeast of Moscow. As of the 2010 Census, Penza had a population of 517,311, making it the 38th-l ...

. Two years later he moved to take the same post in Tula, then Ryazan. Supported by his lyceum friend Mikhail Reitern, now the Minister of Finance, Saltykov adopted rather aggressive finance revision policies, making many enemies in the administrative circles of Tula, Ryazan and Penza. According to Alexander Skabichevsky

Alexander Mikhailovich Skabichevsky (russian: Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Скабиче́вский, September 27 (o.s., 15), 1838, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire – January 11, 1911, o.s., December 29, 1910) was a Russian lit ...

(who's had conversations with provincial officials working under Saltykov's supervision) "he was a rare kind of boss. Even though his frightful barking was making people wince, nobody feared him and everybody loved him - mostly for his caring for his subordinates' needs and also the tendency to overlook people's minor weaknesses and faults when those were not interfering with work."

Finally the governor of Ryazan made an informal complaint which was accounted for by Count Shuvalov, the Chief of Staff of the Special Corps of Gendarmes

The Separate Corps of Gendarmes (russian: Отдельный корпус жандармов) was the uniformed security police of the Imperial Russian Army in the Russian Empire during the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its main responsibilitie ...

, who issued a note stating that Saltykov, as a senior state official "promoted ideas contradicting the needs of maintaining law and order" and was "always in conflict with people of local governments, criticizing and even sabotaging their orders." On July 14, 1868, Saltykov retired: thus the career of "one of the strangest officials in Russian history" ended. Years later, speaking to the historian M.Semevsky, Saltykov confessed he was trying to erase from memory years spent as a government official. But when his vis-a-vis argued that "only his thorough knowledge of every possible stage of the Russian bureaucratic hierarchy made him what he was," the writer had to agree.

''Otechestvennye Zapiski''

On July 1, 1866, ''Sovremennik'' was closed. In the autumn Nekrasov approached the publisher

On July 1, 1866, ''Sovremennik'' was closed. In the autumn Nekrasov approached the publisher Andrey Krayevsky

Andrey Alexandrovich Krayevsky (russian: Андре́й Алекса́ндрович Крае́вский; February 17 .S. 5 1810 – August 20 .S. 8 1889) was a Russian publisher and journalist, best known for his work as an editor-in-chief of ...

and 'rented' ''Otechestvennye Zapiski

''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' ( rus, Отечественные записки, p=ɐˈtʲetɕɪstvʲɪnːɨjɪ zɐˈpʲiskʲɪ, variously translated as "Annals of the Fatherland", "Patriotic Notes", "Notes of the Fatherland", etc.) was a Russian lite ...

''. In September 1868 Saltykov joined the re-vamped team of the magazine as a head of the journalistic department. As in December 1874 Saltykov's health problems (triggered by severe cold he's caught at his mother's funeral) made him travel abroad for treatment, Nekrasov confessed in his April 1875 letter to Pavel Annenkov

Pavel Vasilyevich Annenkov (russian: Па́вел Васи́льевич А́нненков) (July 1, 1813 – March 20, 1887) was a significant Russian Empire literary critic and memoirist.

Biography

Annenkov was born into a wealthy landowning fa ...

: "This journalism thing has always been tough for us and now it lies in tatters. Saltykov carried it all manly and bravely and we all tried our best to follow suit." "This was the only magazine that had its own face… Most talented people were coming to ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' as if it were their home. They trusted my taste and my common sense never to begrudge my editorial cuts. In "OZ" there were published weak things, but stupid things - never," he wrote in a letter to Pavel Annenkov

Pavel Vasilyevich Annenkov (russian: Па́вел Васи́льевич А́нненков) (July 1, 1813 – March 20, 1887) was a significant Russian Empire literary critic and memoirist.

Biography

Annenkov was born into a wealthy landowning fa ...

on May 28, 1884. In 1869 Saltykov's ''Signs of the Times'' and ''Letters About the Province'' came out, their general idea being that the reforms have failed and Russia remained the same country of absolute monarchy where peasant had no rights. "The bars have fallen but Russia's heart gave not a single twitch. Serfdom has been abolished, but landlords rejoiced," he wrote.

In 1870 ''The History of a Town

''The History of a Town'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, История одного города, Istoriya odnogo goroda) is a 1870 novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. The plot presents the history of the town of Glupov (can be transl ...

'' (История одного города) came out, a grotesque, politically risky novel relating the tragicomic history of the fictitious Foolsville, a vague caricature upon the Russian Empire, with its sequence of monstrous rulers, tormenting their hapless vassals. The book was a satire on the whole institution of Russian statehood and the way of life itself, plagued by routine mismanagement, needless oppression, pointless tyranny and sufferers’ apathy. The novel ended with the deadly "it" sweeping the whole thing away, "making the history stop" which was construed by many as a call for radical political change. A series called ''Pompadours and Pompadouresses'' (published in English as ''The Pompadours'', Помпадуры и помпадурши, 1863–1874) looked like a satellite to the ''History of a Town'', a set of real life illustrations to the fantastic chronicles. ''The History of a Town'' caused much controversy. Alexey Suvorin accused the author of deliberately distorting Russian history and insulting the Russian people. "By showing how people live under the yoke of madness I was hoping to invoke in a reader not mirth but most bitter feelings... It is not the history of the state as a whole that I make fun of, but a certain state of things," Saltykov explained.

In 1873 came out ''The Tashkenters Clique'' (Господа Ташкентцы ;''Tashkent

Tashkent (, uz, Toshkent, Тошкент/, ) (from russian: Ташкент), or Toshkent (; ), also historically known as Chach is the capital and largest city of Uzbekistan. It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of ...

’ers'' was a generic term invented by Shchedrin for administrators sent to tame riots in the remote regions of the Russian Empire), a snipe at right-wingers who advocated cruel suppression of peasants' riots, and an experiment in the new form of social novel. 1877 saw the publication of ''In the Spheres of Temperance and Accuracy'', a set of satirical sketches, featuring characters from the classical Russian literature (books by Fonvizin, Griboyedov Griboyedov may refer to:

* Alexander Griboyedov (1795-1829), Russian playwright and diplomat

* Griboyedov Canal

The Griboyedov Canal or Kanal Griboyedova () is a canal in Saint Petersburg, constructed in 1739 along the existing ''Krivusha'' r ...

, Gogol and others) in the contemporary political context.

Later years

''The Well-Meant Speeches'' (Благонамеренные речи, 1876) featured characters belonging to new Russian

''The Well-Meant Speeches'' (Благонамеренные речи, 1876) featured characters belonging to new Russian bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. They ...

. On January 2, 1881, Saltykov wrote to the lawyer and author Yevgeny Utin

Yevgeny Isaakovitch Utin () (3 November 1843 – 9 August 1894) was a Russian lawyer and journalist. He was arrested in the student unrest in Saint Petersburg in 1861 and held in the Peter and Paul Fortress for some time. After graduating from t ...

: "I took a look at the family, the state, the property and found out that none of such things exist. And that those very principles for the sake of which freedoms have been granted, were not respected as principles any more, even by those who seemed to hold them." ''The Well-Meant Speeches'' initially contained several stories about the Golovlyov family. In 1880 Saltykov-Shchedrin extracted all of them to begin a separate book which evolved into his most famous novel, showing the stagnation of the land-based dvoryanstvo. ''The Golovlyov Family

''The Golovlyov Family'' (russian: Господа Головлёвы, translit=Gospoda Golovlyovy; also translated as ''The Golovlevs'' or ''A Family of Noblemen: The Gentlemen Golovliov'') is a novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, written in the ...

'' (Господа Головлёвы, 1880; also translated as ''A Family of Noblemen''), a crushingly gloomy study of the institution of the family as cornerstone of society, traced the moral and physical decline of three generations of a Russian gentry family. Central to it was the figure of Porfiry 'Little Judas' Golovlyov, a character whose nickname (Iudushka, in Russian transcription) became synonymous with mindless hypocrisy and self-destructive egotism, leading to moral degradation and disintegration of personality.

In the 1870s Saltykov sold his Moscow estate and bought the one near Oranienbaum, Saint Petersburg, which he came to refer to as 'my Mon Repos'. He proved to be an unsuccessful landowner, though, and finally sold it, having lost a lot of money. Stories vaguely describing this experience later made it into the novel ''Mon Repos Haven'' (Убежище Монрепо, 1879) and the collection of sketches ''All the Year Round'' (Круглый год), both books attacking the very roots of Russian capitalism. "Fatherland is a pie - that's the idea those narrow, obnoxious minds follow," he wrote. The latter collection remained unfinished due to fierceness of censorship in the wake of the assassination of Alexander II.

In 1875-1885 Saltykov was often visiting Germany, Switzerland and France for medical treatment. The result of these recreational trips was the series of sketches called ''Abroad'' (За рубежом, 1880–1881), expressing skepticism about the Western veneer of respectability which hid underneath horrors similar to the ones that were open in Russia (the latter portrayed as The Boy Without Pants, as opposed to The Boy in Pants, symbolizing Europe). In 1882 ''Letters to Auntie'' (Письма к тётеньке), written in the atmosphere of tough censorship came out, a satire on the society in general and its cultural elite in particular (the 'auntie' in question).

In 1883, now critically ill, Saltykov published '' Modern Idyll'' (Современная идиллия), the novel he started in 1877–1878, targeting those of intelligentsia who were eager to prove their loyalty to the authorities. ''The Poshekhonye Stories'' (Пошехонские рассказы, 1883), ''Motley Letters'' (Пёстрые письма, 1884) and ''Unfinished Talks'' (Недоконченные беседы, 1886) followed, but by this time ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' were under increasing pressure from the censors, Shchedrin's prose being the latter's main target. The May 1874 issue with ''The Well-Meant Speeches'' has been destroyed, several other releases postponed for Saltykov's pieces to be excised. In 1874-1879 ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' suffered 18 censorial sanctions, all having to do with Shchedrin's work, most of which (''Well-Meant Speeches'', ''Letters to Auntie'', many fairytales) were banned. "It is despicable times that we are living through... and it takes a lot of strength not to give up," Saltykov wrote.

The demise of ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' in 1884 dealt Saltykov a heavy blow. "The possibility to talk with my readers has been taken away from me and this pain is stronger than any other," he complained. "The whole of the Russian press suffered from the ''Otechestvenny Zapiski''s closure… Where there's been a lively tissue now there is a chasm of emptiness. And Shchedrin's life has been curtailed, probably, for many years, by this 'excision'," wrote Korolenko in 1889. Saltykov-Shchedrin's last works were published by ''

In 1883, now critically ill, Saltykov published '' Modern Idyll'' (Современная идиллия), the novel he started in 1877–1878, targeting those of intelligentsia who were eager to prove their loyalty to the authorities. ''The Poshekhonye Stories'' (Пошехонские рассказы, 1883), ''Motley Letters'' (Пёстрые письма, 1884) and ''Unfinished Talks'' (Недоконченные беседы, 1886) followed, but by this time ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' were under increasing pressure from the censors, Shchedrin's prose being the latter's main target. The May 1874 issue with ''The Well-Meant Speeches'' has been destroyed, several other releases postponed for Saltykov's pieces to be excised. In 1874-1879 ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' suffered 18 censorial sanctions, all having to do with Shchedrin's work, most of which (''Well-Meant Speeches'', ''Letters to Auntie'', many fairytales) were banned. "It is despicable times that we are living through... and it takes a lot of strength not to give up," Saltykov wrote.

The demise of ''Otechestvennye Zapiski'' in 1884 dealt Saltykov a heavy blow. "The possibility to talk with my readers has been taken away from me and this pain is stronger than any other," he complained. "The whole of the Russian press suffered from the ''Otechestvenny Zapiski''s closure… Where there's been a lively tissue now there is a chasm of emptiness. And Shchedrin's life has been curtailed, probably, for many years, by this 'excision'," wrote Korolenko in 1889. Saltykov-Shchedrin's last works were published by ''Vestnik Evropy

''Vestnik Evropy'' (russian: Вестник Европы) (''Herald of Europe'' or ''Messenger of Europe'') was the major liberal magazine of late-nineteenth-century Russia. It was published from 1866 to 1918.

The magazine (named for an earlier ...

'' and ''Russkye Vedomosti'', among them a collection of satirical fable

Fable is a literary genre: a succinct fictional story, in prose or verse (poetry), verse, that features animals, legendary creatures, plants, inanimate objects, or forces of nature that are Anthropomorphism, anthropomorphized, and that illustrat ...

s and tales ''Fairy Tales for Children of a Fair Age'' (Сказки для детей изрядного возраста, better known as ''Fables'') and a cycle of sketches ''Small Things in Life'' (Мелочи жизни, 1881–1887), a set of realistic mini-dramas about common people destroyed by the terror of daily routine. Saltykov's last publication was semi-autobiographical novel ''Old Years in Poshekhonye'' (Пошехонская старина), published in 1887–1889 in ''Vestnik Evropy''. He planned another piece called ''Forgotten Words'' (writing to Nikolai Mikhailovsky

Nikolay Konstantinovich Mikhaylovsky () (, Meshchovsk–, Saint Petersburg) was a Russian literary critic, sociologist, writer on public affairs, and one of the theoreticians of the Narodniki movement.

Biography

The school of thinkers he be ...

not long before his death: "There were, you know, words in Russian: honour, fatherland, humanity… They are worth of being reminded about") but never even started it.

Mikhail Evgraphovich Saltykov-Schedrin died of stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

in Saint Petersburg and was interred in the Volkovo Cemetery

The Volkovo Cemetery (also Volkovskoe) (russian: Во́лковское кла́дбище or Во́лково кла́дбище) is one of the largest and oldest non- Orthodox cemeteries in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Until the early 20th century i ...

, next to Turgenev, according to his last wish.

Legacy

Mikhail Bulgakov was among writers, influenced by Saltykov.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin is regarded to be the most prominent satirist in the history of the Russian literature. According to critic and biographer Maria Goryachkina, he's managed to compile "the satirical encyclopedia" of contemporary Russian life, targeting first serfdom with its degrading effect upon the society, then, after its abolition, - corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, opportunistic tendencies in intelligentsia, greed and amorality of those at power, but also - apathy, meekness and social immobility of the common people of Russia. His satirical cycle ''Fables'' and the two major works, ''

Mikhail Bulgakov was among writers, influenced by Saltykov.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin is regarded to be the most prominent satirist in the history of the Russian literature. According to critic and biographer Maria Goryachkina, he's managed to compile "the satirical encyclopedia" of contemporary Russian life, targeting first serfdom with its degrading effect upon the society, then, after its abolition, - corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, opportunistic tendencies in intelligentsia, greed and amorality of those at power, but also - apathy, meekness and social immobility of the common people of Russia. His satirical cycle ''Fables'' and the two major works, ''The History of a Town

''The History of a Town'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, История одного города, Istoriya odnogo goroda) is a 1870 novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. The plot presents the history of the town of Glupov (can be transl ...

'' and ''The Golovlyov Family

''The Golovlyov Family'' (russian: Господа Головлёвы, translit=Gospoda Golovlyovy; also translated as ''The Golovlevs'' or ''A Family of Noblemen: The Gentlemen Golovliov'') is a novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, written in the ...

'', are widely regarded as his masterpieces. Maxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

wrote in 1909: "The importance of his satire is immense, first for… its almost clairvoyant vision of the path the Russian society had to travel - from 1860s to nowadays." "The pathos of satirical humanism was his driving force. The mere awareness of people being treated cruelly while causes for their suffer were removable, filled him with rage and with this murderous laughter that makes his satire so distinctive," wrote Alexander Fadeev.

James Wood calls Shchedrin a precursor of Knut Hamsun

Knut Hamsun (4 August 1859 – 19 February 1952) was a Norwegian writer who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1920. Hamsun's work spans more than 70 years and shows variation with regard to consciousness, subject, perspective a ...

and the modernists

Modernism is both a philosophy, philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western world, Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new fo ...

:

Saltykov-Shchedrin has been lavishly praised by Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

critics as "the true revolutionary", but his mindset (as far as they were concerned) was not without a fault, for he, according to Goryachkina, "failed to recognize the historically progressive role of capitalism and never understood the importance of the emerging proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philo ...

". Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

(who knew Russian and held Shchedrin in high esteem) read ''Haven in Mon Repos'' (1878–1879) and was unimpressed. "The last section, 'Warnings', is weak and the author in general seems to be not very strong on positivity," he wrote.

Some contemporaries (Nikolai Pisarev

Nikolai Nikolayevich Pisarev (russian: Николай Николаевич Писарев; born 23 November 1968) is a Russian football manager and a former player. He is an assistant coach with Russia national football team.

International car ...

, Alexei Suvorin) dismissed Saltykov-Shchedrin as the one taken to 'laughing for laughter's sake'. Vladimir Korolenko

Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko (russian: Влади́мир Галактио́нович Короле́нко, ua, Володи́мир Галактіо́нович Короле́нко; 27 July 1853 – 25 December 1921) was a Ukrainian-born ...

disagreed; he regarded Shchedrin's laughter to be the essential part of Russian life. "Shchedrin, he's still laughing, people were saying, by way of reproach... Thankfully, yes, no matter how hard it was for him to do this, in the most morbid times of our recent history this laughter was heard… One had to have a great moral power to make others laugh, while suffering deeply (as he did) from all the grieves of those times," he argued.

According to D.S.Mirsky, the greater part of Saltykov's work is a rather nondescript kind of satirical journalism

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation (profes ...

, generally with little or no narrative structure, and intermediate in form between the classical "character" and the contemporary ''feuilleton

A ''feuilleton'' (; a diminutive of french: feuillet, the leaf of a book) was originally a kind of supplement attached to the political portion of French newspapers, consisting chiefly of non-political news and gossip, literature and art critici ...

''. Greatly popular though it was in its own time, it has since lost much of its appeal simply because it satirizes social conditions that have long ceased to exist and much of it has become unintelligible without commentary. Mirsky saw ''The History of a Town'' (a sort of parody of Russian history, concentrated in the microcosm of a provincial town, whose successive governors are transparent caricatures of Russian sovereigns and ministers, and whose very name is representative of its qualities) as the work that summed up the achievement of Saltykov's first period. He praised ''The Golovlyov Family'', calling it the gloomiest book in all Russian literature—"all the more gloomy because the effect is attained by the simplest means without any theatrical, melodramatic, or atmospheric effects." "The most remarkable character of this novel is Porfiry Golovlyov, nicknamed 'Little Judas', the empty and mechanical hypocrite who cannot stop talking unctuous and meaningless humbug, not for any inner need or outer profit, but because his tongue is in need of constant exercise," Mirsky wrote.

Most works of Saltykov's later period were written in a language that the satirist himself called Aesopian. This way, though, the writer was able to fool censors in the times of political oppression and take most radical ideas to print, which was the matter of his pride. "It is one continuous circumlocution because of censorship and requires a constant reading commentary," Mirsky argued. The use of Aesopic language was one reason why Saltykov-Shchedrin has never achieved as much acclaim in the West as had three of his great contemporaries, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, according to

Most works of Saltykov's later period were written in a language that the satirist himself called Aesopian. This way, though, the writer was able to fool censors in the times of political oppression and take most radical ideas to print, which was the matter of his pride. "It is one continuous circumlocution because of censorship and requires a constant reading commentary," Mirsky argued. The use of Aesopic language was one reason why Saltykov-Shchedrin has never achieved as much acclaim in the West as had three of his great contemporaries, Turgenev, Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, according to Sofia Kovalevskaya

Sofya Vasilyevna Kovalevskaya (russian: link=no, Софья Васильевна Ковалевская), born Korvin-Krukovskaya ( – 10 February 1891), was a Russian mathematician who made noteworthy contributions to analysis, partial differen ...

. "It is unbelievable, how well we've learned to read between the lines in Russia," the great mathematician remarked in her essay written in 1889 in Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

. Another reason had to do with peculiarities of Saltykov's chosen genre: his credo "has always been a satire, spiced with fantasy, not far removed from Rabelais, the kind of literature that's tightly bound to its own national soil... Tears are the same wherever we go, but each nation laughs in its own way," Kovalevskaya argued.

Saltykov's style of writing, according to D.S.Mirsky, was based on the bad journalistic style of the period, which originated largely with Osip Senkovsky

Osip Ivanovich Senkovsky (russian: О́сип Ива́нович Сенко́вский), born Józef Julian Sękowski ( in Antagonka, near Vilnius – in Saint Petersburg), was a Polish-Russian orientalist, journalist, and entertainer.

Life

...

, and which "today invariably produces an impression of painfully elaborate vulgarity."D.S. Mirsky

D. S. Mirsky is the English pen-name of Dmitry Petrovich Svyatopolk-Mirsky (russian: Дми́трий Петро́вич Святопо́лк-Ми́рский), often known as Prince Mirsky ( – c. 7 June 1939), a Russian political and lit ...

. ''A History of Russian Literature''. Northwestern University Press, 1999. . Page 294. Many other critics (Goryachkina among them) disagreed, praising the author's lively, rich language and the way he mastered both stark realism (''The Golovlyov Family'', ''Old Times in Poshekhonye'') and satirical grotesque merged with fantasy. Of the writer's stylistic peculiarities biographer Sergey Krivenko (of the Narodnik movement, the one which Saltykov has always been in opposition to) wrote: "It is difficult to assess his works using the established criteria. It's a mix of a variety of genres: poetry and documentary report, epics and satire, tragedy and comedy. In the process of reading it is impossible to decide what exactly it is, but the general impression is invariably strong, as of something very lively and harmonic. Ignoring the established formats, Saltykov was driven by two things: current stream of new ideas and those lofty ideals he’s been aspiring to." Saltykov, according to Krivenko, occasionally repeated himself, but never denied this, explaining it by the need of always being engaged with 'hot' issues – "things which in the course of decades were in their own right repeating themselves with such damning monotony". "There are not many writers in Rus whose very name would give that much to one's mind and heart, and who'd leave such a vast literary heritage, rich and diverse both in essence and in form, written in a very special language which even in his lifetime became known as 'saltykovian'," wrote Krivenko in 1895. "Saltykov's gift was no lesser than that of Gogol, neither in originality nor in itspower," the biographer reckoned.

Saltykov-Schedrin was a controversial figure and often found himself a target of sharp criticism, mainly for his alleged 'lack of patriotism' and negativism. He's never seen himself a promoter of the latter and often proclaimed his belief in the strength of a common man, seeing the latter as holder of principles of real democracy. In 1882, as he, feeling depressed by the critical response to his work, made rather a pessimistic assessment of his life in literature, Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev (; rus, links=no, Ива́н Серге́евич Турге́невIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; 9 November 1818 – 3 September 1883 (Old Style dat ...

was quick to reassure him. "The writer who is most hated, is most loved, too. You'd have known none of this, had you remained M.E.Saltykov, a mere hereditary Russian aristocrat. But you are Saltykov-Schedrin, a writer who happened to draw a distinctive line in our literature: that's why you are either hated or loved, depending n who reads you Such is the true 'outcome' of your life in literature, and you must be pleased with it."

For all his insight and taste for detail, Saltykov was never keen on examining individual characters (even if he did create memorable ones). Admittedly, he was always more concerned with things general and typical, gauging social tendencies, collective urges and what he termed 'herd instincts in a modern man', often resorting to schemes and caricatures.

In his later years Saltykov-Schedrin found himself to be a strong influence upon the radical youth of the time. In 1885–1886, Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

's brother Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

and sister Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 12 ...

were members of one of the numerous student's delegations that came home to visit the ailing Schedrin, latter referring to him as "the revolutionary youth's favourite writer". Saltykov-Shedrin was a personal favourite of Lenin himself, who often namechecked the writer's characters to prove his point – Iudushka, in particular, served well to label many of his adversaries: Russian old landlords and emerging capitalists, Tzarist government members and, notably, his own associate Trotzky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian M ...

.

Selected works

Novels

* ''The History of a Town

''The History of a Town'' ( pre-reform Russian: ; post-reform rus, История одного города, Istoriya odnogo goroda) is a 1870 novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. The plot presents the history of the town of Glupov (can be transl ...

'' (История одного города, 1870)

* ''Ubezhishche Monrepo'' (Убежище Монрепо, 1879, Mon Repos Haven), not translated.

* ''The Golovlyov Family

''The Golovlyov Family'' (russian: Господа Головлёвы, translit=Gospoda Golovlyovy; also translated as ''The Golovlevs'' or ''A Family of Noblemen: The Gentlemen Golovliov'') is a novel by Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin, written in the ...

'' (Господа Головлёвы, 1880)

* ''Sovremennaya idilliya'' (Современная идиллия, 1883, ''Modern Idyll''), not translated.

* ''Poshekhonskaya starina'' (Пошехонская старина, 1889, Old Years in Poshekhonye), not translated.

Stories and sketches

* ''Provincial Sketches'' (also: ''Tchinovnicks: Sketches Of Provincial Life'', Губернские очерки, 1856) * ''The Pompadours'' (also: ''Pompadours and Pompadouresses'' and ''Messieurs et Mesdames Pompadours'', Помпадуры и Помпадурши, 1863–1874)Other