metabolic process on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of

Most of the structures that make up animals, plants and microbes are made from four basic classes of

Most of the structures that make up animals, plants and microbes are made from four basic classes of

Carbohydrates are

Carbohydrates are

Metabolism involves a vast array of chemical reactions, but most fall under a few basic types of reactions that involve the transfer of

Metabolism involves a vast array of chemical reactions, but most fall under a few basic types of reactions that involve the transfer of

Fats are catabolized by

Fats are catabolized by

Pumping protons out of the mitochondria creates a proton concentration difference across the membrane and generates an

Pumping protons out of the mitochondria creates a proton concentration difference across the membrane and generates an

Photosynthesis is the synthesis of carbohydrates from sunlight and

Photosynthesis is the synthesis of carbohydrates from sunlight and

Fatty acids are made by

Fatty acids are made by

There are multiple levels of metabolic regulation. In intrinsic regulation, the metabolic pathway self-regulates to respond to changes in the levels of substrates or products; for example, a decrease in the amount of product can increase the

There are multiple levels of metabolic regulation. In intrinsic regulation, the metabolic pathway self-regulates to respond to changes in the levels of substrates or products; for example, a decrease in the amount of product can increase the

The central pathways of metabolism described above, such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, are present in all three domains of living things and were present in the

The central pathways of metabolism described above, such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, are present in all three domains of living things and were present in the

Classically, metabolism is studied by a

Classically, metabolism is studied by a

In these early studies, the mechanisms of these metabolic processes had not been identified and a vital force was thought to animate living tissue. In the 19th century, when studying the

In these early studies, the mechanisms of these metabolic processes had not been identified and a vital force was thought to animate living tissue. In the 19th century, when studying the

The Biochemistry of Metabolism

(archived 8 March 2005)

Sparknotes SAT biochemistry

Overview of biochemistry. School level.

Undergraduate-level guide to molecular biology. Human metabolism

Guide to human metabolic pathways. School level.

THE Medical Biochemistry Page

Comprehensive resource on human metabolism. Databases

Flow Chart of Metabolic Pathways

at ExPASy

IUBMB-Nicholson Metabolic Pathways Chart

SuperCYP: Database for Drug-Cytochrome-Metabolism

Metabolic pathways

* {{Authority control, state=collapsed Metabolism, Underwater diving physiology

life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

-sustaining chemical reactions

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an energy change as new products ...

in organisms

An organism is any living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have been pr ...

. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

available to run cellular processes; the conversion of food to building blocks of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s, lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s, nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s, and some carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s; and the elimination of metabolic waste

Metabolic wastes or excrements are substances left over from metabolic processes (such as cellular respiration) which cannot be used by the organism (they are surplus or toxic), and must therefore be excreted. This includes nitrogen compounds ...

s. These enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

-catalyzed reactions allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

, and respond to their environments. The word ''metabolism'' can also refer to the sum of all chemical reactions that occur in living organisms, including digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into th ...

and the transportation of substances into and between different cells, in which case the above described set of reactions within the cells is called intermediary (or intermediate) metabolism.

Metabolic reactions may be categorized as ''catabolic

Catabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidized to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. Catabolism breaks down large molecules (such as polysaccharides, lipi ...

''—the ''breaking down'' of compounds (for example, of glucose to pyruvate by cellular respiration

Cellular respiration is the process of oxidizing biological fuels using an inorganic electron acceptor, such as oxygen, to drive production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which stores chemical energy in a biologically accessible form. Cell ...

); or ''anabolic

Anabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that construct macromolecules like DNA or RNA from smaller units. These reactions require energy, known also as an endergonic process. Anabolism is the building-up aspect of metabolism, whereas catab ...

''—the ''building up'' (synthesis

Synthesis or synthesize may refer to:

Science Chemistry and biochemistry

*Chemical synthesis, the execution of chemical reactions to form a more complex molecule from chemical precursors

**Organic synthesis, the chemical synthesis of organi ...

) of compounds (such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic acids). Usually, catabolism releases energy, and anabolism consumes energy.

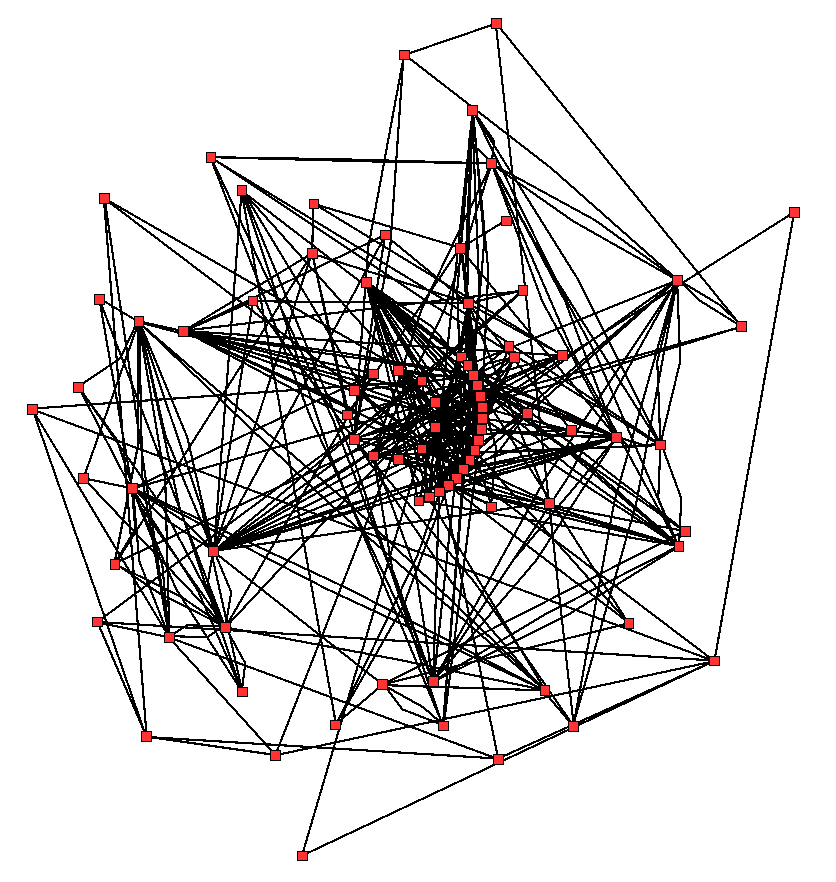

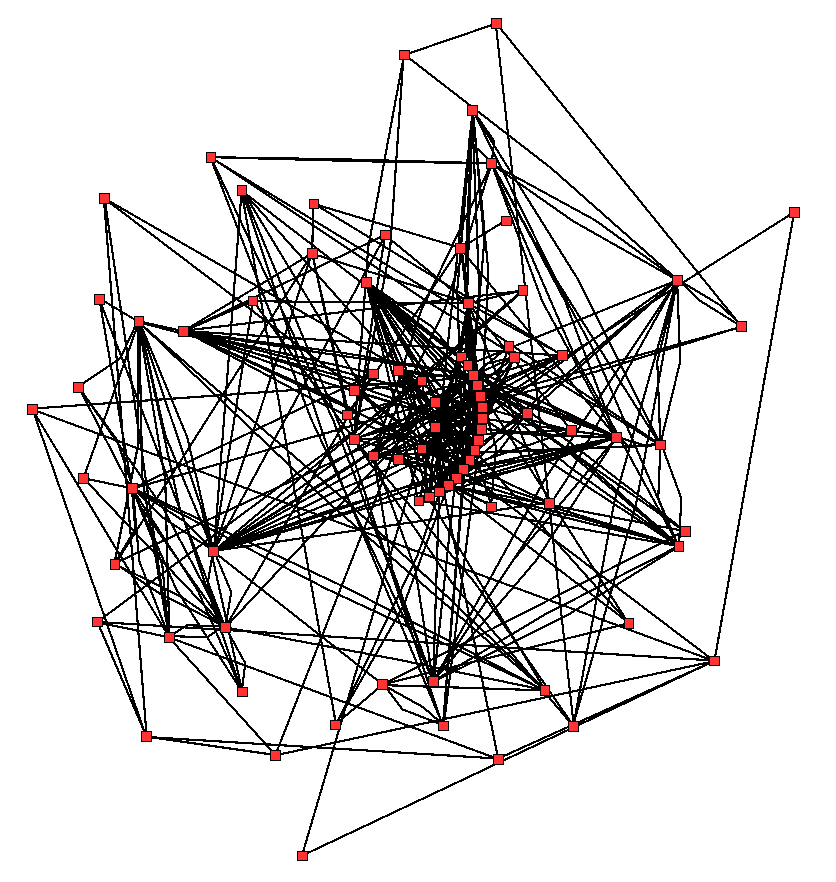

The chemical reactions of metabolism are organized into metabolic pathway

In biochemistry, a metabolic pathway is a linked series of chemical reactions occurring within a cell (biology), cell. The reactants, products, and Metabolic intermediate, intermediates of an enzymatic reaction are known as metabolites, which are ...

s, in which one chemical is transformed through a series of steps into another chemical, each step being facilitated by a specific enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

. Enzymes are crucial to metabolism because they allow organisms to drive desirable reactions that require energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

and will not occur by themselves, by coupling

A coupling is a device used to connect two shafts together at their ends for the purpose of transmitting power. The primary purpose of couplings is to join two pieces of rotating equipment while permitting some degree of misalignment or end mo ...

them to spontaneous reactions that release energy. Enzymes act as catalysts

Catalysis () is the increase in reaction rate, rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst ...

—they allow a reaction to proceed more rapidly—and they also allow the regulation

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology and society, but the term has slightly different meanings according to context. Fo ...

of the rate of a metabolic reaction, for example in response to changes in the cell's environment or to signals

A signal is both the process and the result of Signal transmission, transmission of data over some transmission media, media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processin ...

from other cells.

The metabolic system of a particular organism determines which substances it will find nutritious

Nutrition is the biochemical and physiological process by which an organism uses food and water to support its life. The intake of these substances provides organisms with nutrients (divided into macro- and micro-) which can be metabolized t ...

and which poison

A poison is any chemical substance that is harmful or lethal to living organisms. The term is used in a wide range of scientific fields and industries, where it is often specifically defined. It may also be applied colloquially or figurati ...

ous. For example, some prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s use hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

as a nutrient, yet this gas is poisonous to animals. The basal metabolic rate

Basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the rate of energy expenditure per unit time by endothermic animals at rest.. In other words it is the energy required by body organs to perform normal It is reported in energy units per unit time ranging from watt ( ...

of an organism is the measure of the amount of energy consumed by all of these chemical reactions.

A striking feature of metabolism is the similarity of the basic metabolic pathways among vastly different species. For example, the set of carboxylic acid

In organic chemistry, a carboxylic acid is an organic acid that contains a carboxyl group () attached to an Substituent, R-group. The general formula of a carboxylic acid is often written as or , sometimes as with R referring to an organyl ...

s that are best known as the intermediates in the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reaction, biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-Co ...

are present in all known organisms, being found in species as diverse as the unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

bacterium ''Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

'' and huge multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell (biology), cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, Embryophyte, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organism ...

s like elephant

Elephants are the largest living land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant ('' Loxodonta africana''), the African forest elephant (''L. cyclotis''), and the Asian elephant ('' Elephas maximus ...

s. These similarities in metabolic pathways are likely due to their early appearance in evolutionary history

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and extinct organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to the present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for '' gigaannum'') and ...

, and their retention is likely due to their efficacy

Efficacy is the ability to perform a task to a satisfactory or expected degree. The word comes from the same roots as '' effectiveness'', and it has often been used synonymously, although in pharmacology a distinction is now often made betwee ...

. In various diseases, such as type II diabetes

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), formerly known as adult-onset diabetes, is a form of diabetes mellitus that is characterized by high blood sugar, insulin resistance, and relative lack of insulin. Common symptoms include increased thirst, frequent ...

, metabolic syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a clustering of at least three of the following five medical conditions: abdominal obesity, high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high serum triglycerides, and low serum high-density lipoprotein (HDL).

Metabolic syndro ...

, and cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

, normal metabolism is disrupted. The metabolism of cancer cells is also different from the metabolism of normal cells, and these differences can be used to find targets for therapeutic intervention in cancer.

Key biochemicals

Most of the structures that make up animals, plants and microbes are made from four basic classes of

Most of the structures that make up animals, plants and microbes are made from four basic classes of molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

s: amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s, carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s, nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

and lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s (often called fat

In nutrition science, nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such chemical compound, compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specif ...

s). As these molecules are vital for life, metabolic reactions either focus on making these molecules during the construction of cells and tissues, or on breaking them down and using them to obtain energy, by their digestion. These biochemicals can be joined to make polymer

A polymer () is a chemical substance, substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeat unit, repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their br ...

s such as DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

and protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s, essential macromolecules

A macromolecule is a "molecule of high relative molecular mass, the structure of which essentially comprises the multiple repetition of units derived, actually or conceptually, from molecules of low relative molecular mass." Polymers are physi ...

of life.

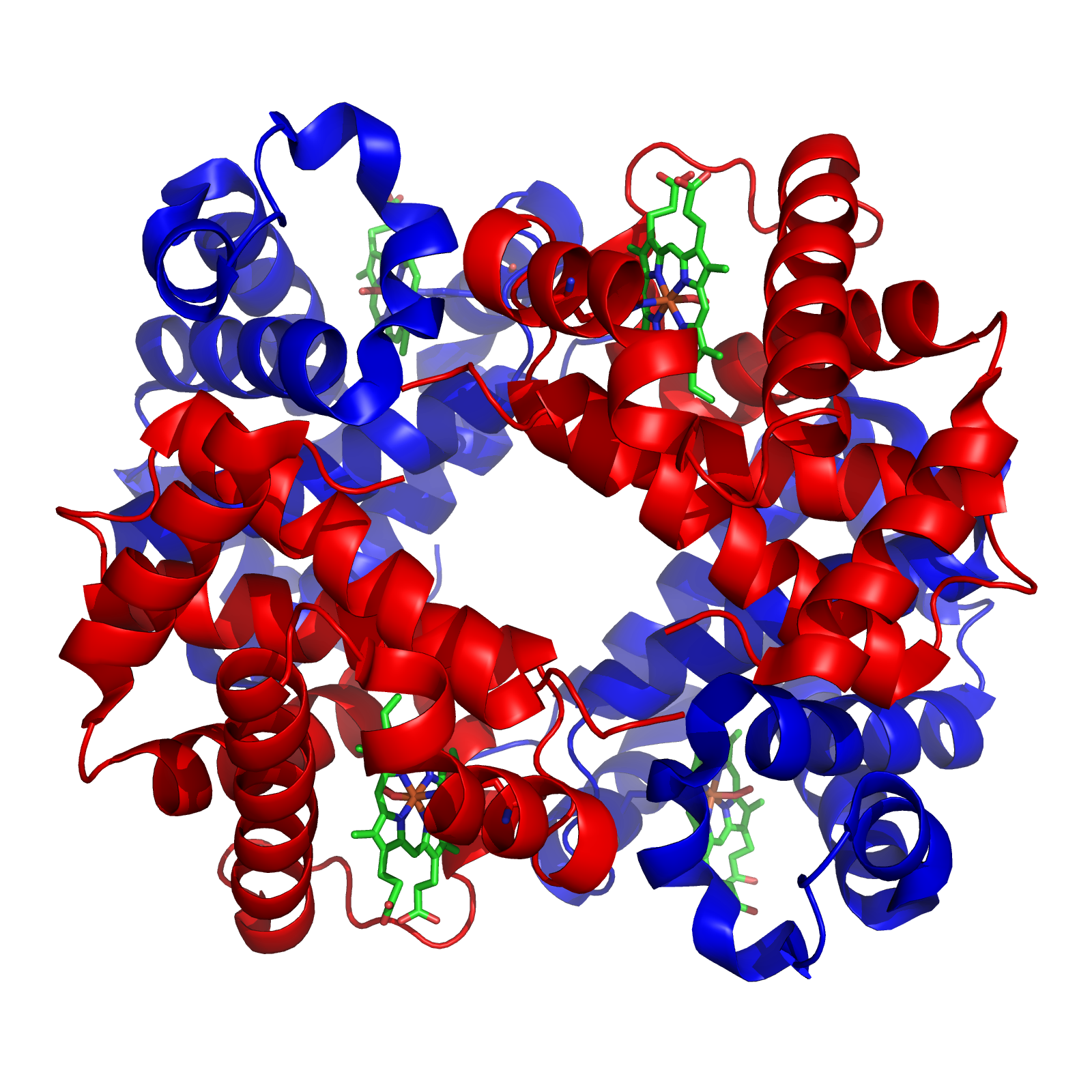

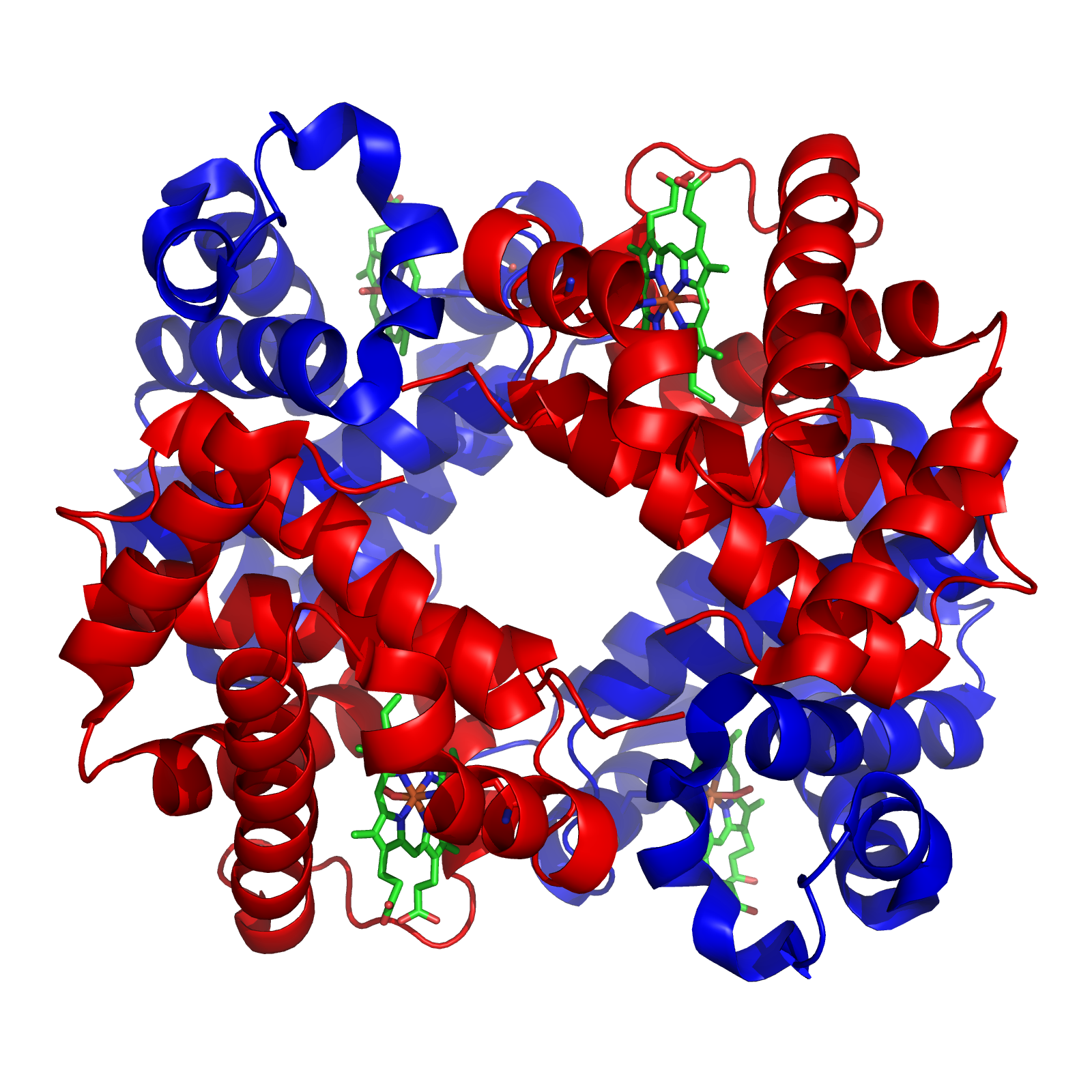

Amino acids and proteins

Proteins are made ofamino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s arranged in a linear chain joined by peptide bond

In organic chemistry, a peptide bond is an amide type of covalent chemical bond linking two consecutive alpha-amino acids from C1 (carbon number one) of one alpha-amino acid and N2 (nitrogen number two) of another, along a peptide or protein cha ...

s. Many proteins are enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s that catalyze

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

the chemical reactions in metabolism. Other proteins have structural or mechanical functions, such as those that form the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

, a system of scaffolding

Scaffolding, also called scaffold or staging, is a temporary structure used to support a work crew and materials to aid in the construction, maintenance and repair of buildings, bridges and all other human-made structures. Scaffolds are widely u ...

that maintains the cell shape. Proteins are also important in cell signaling

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the Biological process, process by which a Cell (biology), cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all Cell (biol ...

, immune responses, cell adhesion

Cell adhesion is the process by which cells interact and attach to neighbouring cells through specialised molecules of the cell surface. This process can occur either through direct contact between cell surfaces such as Cell_junction, cell junc ...

, active transport

In cellular biology, active transport is the movement of molecules or ions across a cell membrane from a region of lower concentration to a region of higher concentration—against the concentration gradient. Active transport requires cellula ...

across membranes, and the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell (biology), cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA re ...

. Amino acids also contribute to cellular energy metabolism by providing a carbon source for entry into the citric acid cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-CoA oxidation. The e ...

), especially when a primary source of energy, such as glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

, is scarce, or when cells undergo metabolic stress.

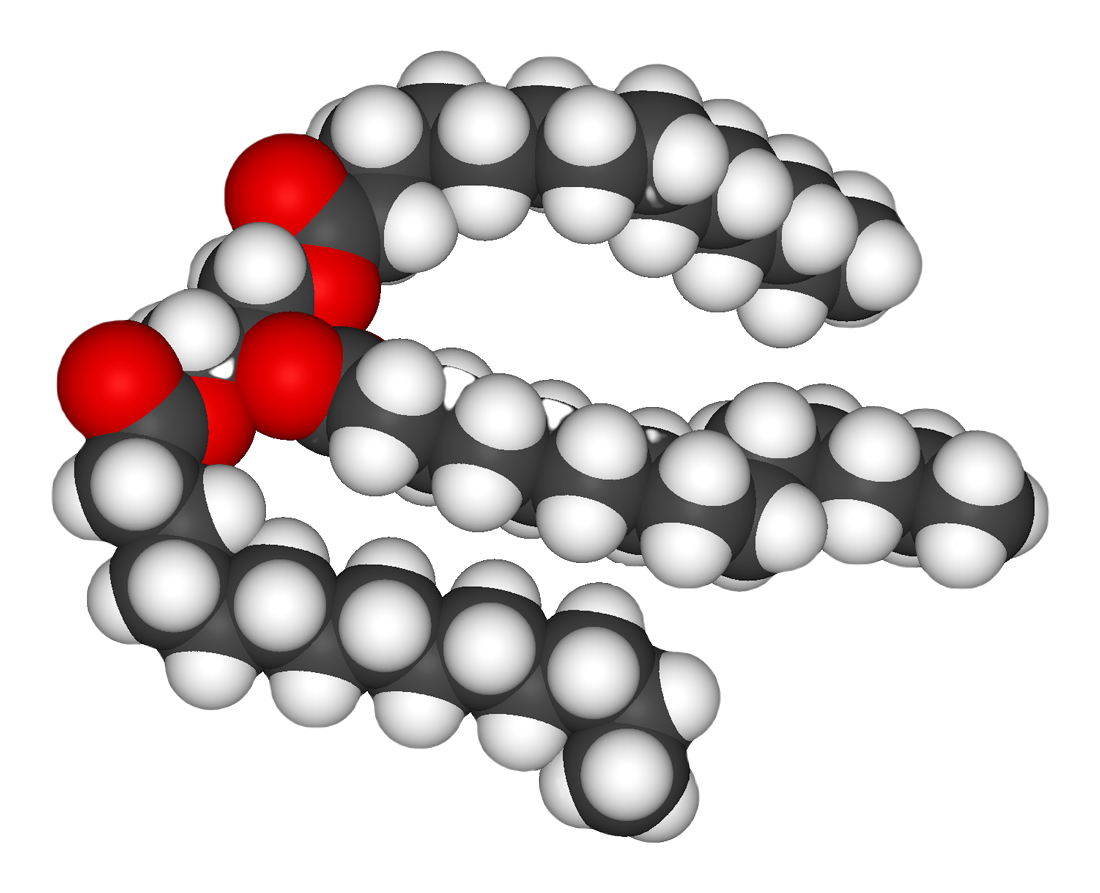

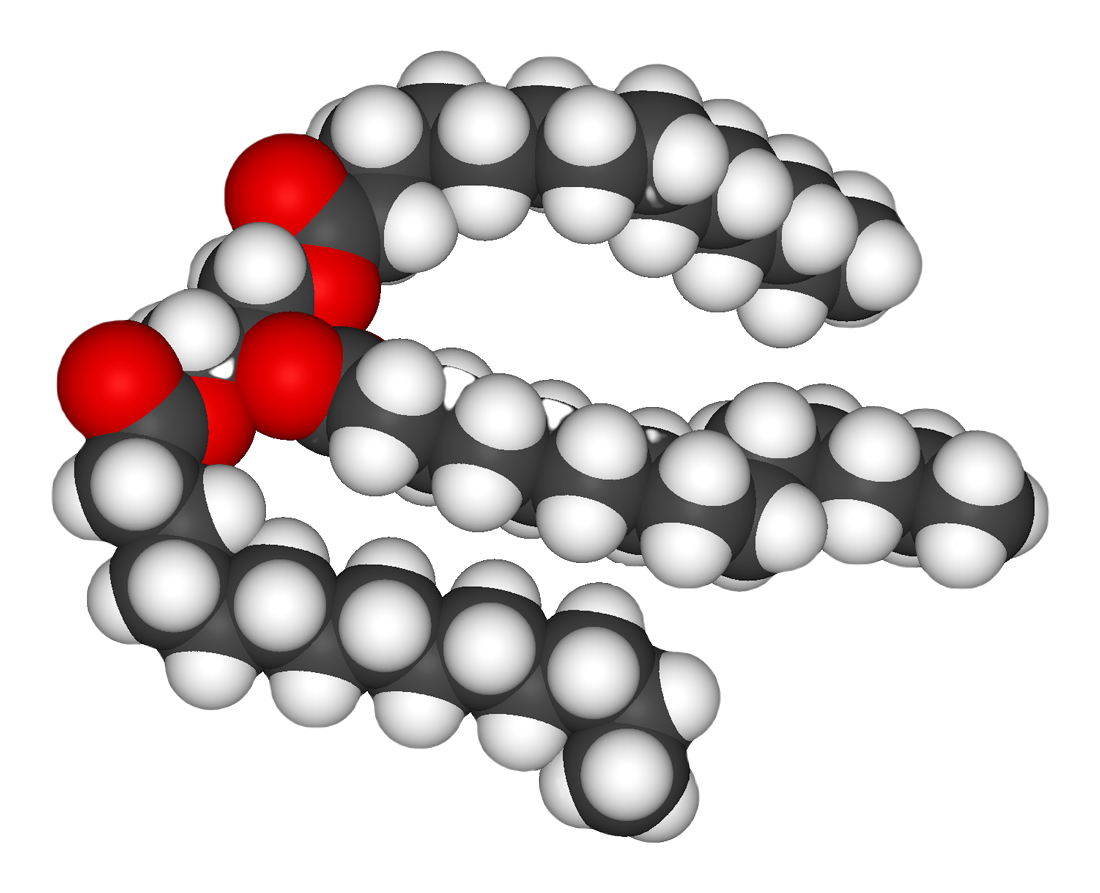

Lipids

Lipids are the most diverse group of biochemicals. Their main structural uses are as part of internal and externalbiological membrane

A biological membrane, biomembrane or cell membrane is a selectively permeable membrane that separates the interior of a cell from the external environment or creates intracellular compartments by serving as a boundary between one part of th ...

s, such as the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

. Their chemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when the substances undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (20 ...

can also be used. Lipids contain a long, non-polar hydrocarbon chain

In organic chemistry, hydrocarbons ( compounds composed solely of carbon and hydrogen) are divided into two classes: aromatic compounds and aliphatic compounds (; G. ''aleiphar'', fat, oil). Aliphatic compounds can be saturated (in which all ...

with a small polar region containing oxygen. Lipids are usually defined as hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thu ...

or amphipathic

In chemistry, an amphiphile (), or amphipath, is a chemical compound possessing both hydrophilic (''water-loving'', polar) and lipophilic (''fat-loving'', nonpolar) properties. Such a compound is called amphiphilic or amphipathic. Amphiphilic c ...

biological molecules but will dissolve in organic solvent

A solvent (from the Latin '' solvō'', "loosen, untie, solve") is a substance that dissolves a solute, resulting in a solution. A solvent is usually a liquid but can also be a solid, a gas, or a supercritical fluid. Water is a solvent for p ...

s such as ethanol

Ethanol (also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound with the chemical formula . It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol, with its formula also written as , or EtOH, where Et is the ps ...

, benzene

Benzene is an Organic compound, organic chemical compound with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar hexagonal Ring (chemistry), ring with one hyd ...

or chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane (often abbreviated as TCM), is an organochloride with the formula and a common solvent. It is a volatile, colorless, sweet-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to refrigerants and po ...

. The fat

In nutrition science, nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such chemical compound, compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specif ...

s are a large group of compounds that contain fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s and glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

; a glycerol molecule attached to three fatty acids by ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an acid (either organic or inorganic) in which the hydrogen atom (H) of at least one acidic hydroxyl group () of that acid is replaced by an organyl group (R). These compounds contain a distin ...

linkages is called a triacylglyceride. Several variations of the basic structure exist, including backbones such as sphingosine

Sphingosine (2-amino-4-trans-octadecene-1,3-diol) is an 18-carbon amino alcohol with an unsaturated hydrocarbon chain, which forms a primary part of sphingolipids, a class of cell membrane lipids that include sphingomyelin, an important phosphol ...

in sphingomyelin

Sphingomyelin (SPH, ) is a type of sphingolipid found in animal cell membranes, especially in the membranous myelin sheath that surrounds some nerve cell axons. It usually consists of phosphocholine and ceramide, or a phosphoethanolamine hea ...

, and hydrophilic

A hydrophile is a molecule or other molecular entity that is attracted to water molecules and tends to be dissolved by water.Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon'' Oxford: Clarendon Press.

In contrast, hydrophobes are n ...

groups such as phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

in phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s. Steroid

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused compound, fused rings (designated A, B, C, and D) arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes t ...

s such as sterol

A sterol is any organic compound with a Skeletal formula, skeleton closely related to Cholestanol, cholestan-3-ol. The simplest sterol is gonan-3-ol, which has a formula of , and is derived from that of gonane by replacement of a hydrogen atom on ...

are another major class of lipids.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are

Carbohydrates are aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

s or ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

s, with many hydroxyl

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

groups attached, that can exist as straight chains or rings. Carbohydrates are the most abundant biological molecules, and fill numerous roles, such as the storage and transport of energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

(starch

Starch or amylum is a polymeric carbohydrate consisting of numerous glucose units joined by glycosidic bonds. This polysaccharide is produced by most green plants for energy storage. Worldwide, it is the most common carbohydrate in human diet ...

, glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

) and structural components (cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

in plants, chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

in animals). The basic carbohydrate units are called monosaccharide

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhy ...

s and include galactose

Galactose (, ''wikt:galacto-, galacto-'' + ''wikt:-ose#Suffix 2, -ose'', ), sometimes abbreviated Gal, is a monosaccharide sugar that is about as sweetness, sweet as glucose, and about 65% as sweet as sucrose. It is an aldohexose and a C-4 epime ...

, fructose

Fructose (), or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and gal ...

, and most importantly glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

. Monosaccharides can be linked together to form polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s in almost limitless ways.

Nucleotides

The two nucleic acids, DNA andRNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

, are polymers of nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s. Each nucleotide is composed of a phosphate attached to a ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this comp ...

or deoxyribose

Deoxyribose, or more precisely 2-deoxyribose, is a monosaccharide with idealized formula H−(C=O)−(CH2)−(CHOH)3−H. Its name indicates that it is a deoxy sugar, meaning that it is derived from the sugar ribose by loss of a hydroxy group. D ...

sugar group which is attached to a nitrogenous base

Nucleotide bases (also nucleobases, nitrogenous bases) are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nuc ...

. Nucleic acids are critical for the storage and use of genetic information, and its interpretation through the processes of transcription and protein biosynthesis

Protein biosynthesis, or protein synthesis, is a core biological process, occurring inside Cell (biology), cells, homeostasis, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via Proteolysis, degradation or Protein targeting, export) through the produc ...

. This information is protected by DNA repair

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell (biology), cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encode its genome. A weakened capacity for DNA repair is a risk factor for the development of cancer. DNA is cons ...

mechanisms and propagated through DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

. Many virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es have an RNA genome, such as HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

, which uses reverse transcription

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to convert RNA genome to DNA, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B virus, hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, by retrot ...

to create a DNA template from its viral RNA genome. RNA in ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to Catalysis, catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozy ...

s such as spliceosome

A spliceosome is a large ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex found primarily within the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The spliceosome is assembled from small nuclear RNAs ( snRNA) and numerous proteins. Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) molecules bind to sp ...

s and ribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

s is similar to enzymes as it can catalyze chemical reactions. Individual nucleoside

Nucleosides are glycosylamines that can be thought of as nucleotides without a phosphate group. A nucleoside consists simply of a nucleobase (also termed a nitrogenous base) and a five-carbon sugar (ribose or 2'-deoxyribose) whereas a nucleotid ...

s are made by attaching a nucleobase

Nucleotide bases (also nucleobases, nitrogenous bases) are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which, in turn, are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nuc ...

to a ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this comp ...

sugar. These bases are heterocyclic

A heterocyclic compound or ring structure is a cyclic compound that has atoms of at least two different elements as members of its ring(s). Heterocyclic organic chemistry is the branch of organic chemistry dealing with the synthesis, proper ...

rings containing nitrogen, classified as purine

Purine is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound that consists of two rings (pyrimidine and imidazole) fused together. It is water-soluble. Purine also gives its name to the wider class of molecules, purines, which include substituted puri ...

s or pyrimidine

Pyrimidine (; ) is an aromatic, heterocyclic, organic compound similar to pyridine (). One of the three diazines (six-membered heterocyclics with two nitrogen atoms in the ring), it has nitrogen atoms at positions 1 and 3 in the ring. The oth ...

s. Nucleotides also act as coenzymes in metabolic-group-transfer reactions.

Coenzymes

functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is any substituent or moiety (chemistry), moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions r ...

s of atoms and their bonds within molecules. This common chemistry allows cells to use a small set of metabolic intermediates to carry chemical groups between different reactions. These group-transfer intermediates are called coenzyme

A cofactor is a non-protein chemical compound or Metal ions in aqueous solution, metallic ion that is required for an enzyme's role as a catalysis, catalyst (a catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction). Cofactors can ...

s. Each class of group-transfer reactions is carried out by a particular coenzyme, which is the substrate

Substrate may refer to:

Physical layers

*Substrate (biology), the natural environment in which an organism lives, or the surface or medium on which an organism grows or is attached

** Substrate (aquatic environment), the earthy material that exi ...

for a set of enzymes that produce it, and a set of enzymes that consume it. These coenzymes are therefore continuously made, consumed and then recycled.

One central coenzyme is adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a nucleoside triphosphate that provides energy to drive and support many processes in living cell (biology), cells, such as muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known ...

(ATP), the energy currency of cells. This nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

is used to transfer chemical energy between different chemical reactions. There is only a small amount of ATP in cells, but as it is continuously regenerated, the human body can use about its own weight in ATP per day. ATP acts as a bridge between catabolism

Catabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidized to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. Catabolism breaks down large molecules (such as polysaccharides, lipid ...

and anabolism

Anabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that construct macromolecules like DNA or RNA from smaller units. These reactions require energy, known also as an Endergonic reaction, endergonic process. Anabolism is the building-up aspect of metabo ...

. Catabolism breaks down molecules, and anabolism puts them together. Catabolic reactions generate ATP, and anabolic reactions consume it. It also serves as a carrier of phosphate groups in phosphorylation

In biochemistry, phosphorylation is described as the "transfer of a phosphate group" from a donor to an acceptor. A common phosphorylating agent (phosphate donor) is ATP and a common family of acceptor are alcohols:

:

This equation can be writ ...

reactions.

A vitamin

Vitamins are Organic compound, organic molecules (or a set of closely related molecules called vitamer, vitamers) that are essential to an organism in small quantities for proper metabolism, metabolic function. Nutrient#Essential nutrients, ...

is an organic compound needed in small quantities that cannot be made in cells. In human nutrition

Human nutrition deals with the provision of essential nutrients in food that are necessary to support human life and good health. Poor nutrition is a chronic problem often linked to poverty, food security, or a poor understanding of nutrition ...

, most vitamins function as coenzymes after modification; for example, all water-soluble vitamins are phosphorylated or are coupled to nucleotides when they are used in cells. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a Cofactor (biochemistry), coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cell (biology), cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphat ...

(NAD+), a derivative of vitamin B3 (niacin

Nicotinic acid, or niacin, is an organic compound and a vitamer of vitamin B3, an essential human nutrient. It is produced by plants and animals from the amino acid tryptophan.

Nicotinic acid is also a prescription medication. Amounts f ...

), is an important coenzyme that acts as a hydrogen acceptor. Hundreds of separate types of dehydrogenase

A dehydrogenase is an enzyme belonging to the group of oxidoreductases that oxidizes a substrate by reducing an electron acceptor, usually NAD+/NADP+ or a flavin coenzyme such as FAD or FMN. Like all catalysts, they catalyze reverse as well as ...

s remove electrons from their substrates and reduce NAD+ into NADH. This reduced form of the coenzyme is then a substrate for any of the reductase

In biochemistry, an oxidoreductase is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of electrons from one molecule, the reductant, also called the electron donor, to another, the oxidant, also called the electron acceptor. This group of enzymes usually uti ...

s in the cell that need to transfer hydrogen atoms to their substrates. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide exists in two related forms in the cell, NADH and NADPH. The NAD+/NADH form is more important in catabolic reactions, while NADP+/NADPH is used in anabolic reactions.

Mineral and cofactors

Inorganic elements play critical roles in metabolism; some are abundant (e.g.sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

and potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

) while others function at minute concentrations. About 99% of a human's body weight is made up of the elements carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

, nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

, sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

, chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

, potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

, hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

, oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

and sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

. Organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s (proteins, lipids and carbohydrates) contain the majority of the carbon and nitrogen; most of the oxygen and hydrogen is present as water.

The abundant inorganic elements act as electrolyte

An electrolyte is a substance that conducts electricity through the movement of ions, but not through the movement of electrons. This includes most soluble Salt (chemistry), salts, acids, and Base (chemistry), bases, dissolved in a polar solven ...

s. The most important ions are sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

, potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

, calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

, magnesium

Magnesium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mg and atomic number 12. It is a shiny gray metal having a low density, low melting point and high chemical reactivity. Like the other alkaline earth metals (group 2 ...

, chloride

The term chloride refers to a compound or molecule that contains either a chlorine anion (), which is a negatively charged chlorine atom, or a non-charged chlorine atom covalently bonded to the rest of the molecule by a single bond (). The pr ...

, phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

and the organic ion bicarbonate

In inorganic chemistry, bicarbonate (IUPAC-recommended nomenclature: hydrogencarbonate) is an intermediate form in the deprotonation of carbonic acid. It is a polyatomic anion with the chemical formula .

Bicarbonate serves a crucial bioche ...

. The maintenance of precise ion gradient

An electrochemical gradient is a gradient of electrochemical potential, usually for an ion that can move across a membrane. The gradient consists of two parts:

* The chemical gradient, or difference in solute concentration across a membrane.

...

s across cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

s maintains osmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a Solution (chemistry), solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.

It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a soluti ...

and pH. Ions are also critical for nerve

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons). Nerves have historically been considered the basic units of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the Electrochemistry, electrochemical nerv ...

and muscle

Muscle is a soft tissue, one of the four basic types of animal tissue. There are three types of muscle tissue in vertebrates: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Muscle tissue gives skeletal muscles the ability to muscle contra ...

function, as action potential

An action potential (also known as a nerve impulse or "spike" when in a neuron) is a series of quick changes in voltage across a cell membrane. An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific Cell (biology), cell rapidly ri ...

s in these tissues are produced by the exchange of electrolytes between the extracellular fluid

In cell biology, extracellular fluid (ECF) denotes all body fluid outside the cells of any multicellular organism. Total body water in healthy adults is about 50–60% (range 45 to 75%) of total body weight; women and the obese typically ha ...

and the cell's fluid, the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells ( intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

. Electrolytes enter and leave cells through proteins in the cell membrane called ion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by Gating (electrophysiol ...

s. For example, muscle contraction

Muscle contraction is the activation of Tension (physics), tension-generating sites within muscle cells. In physiology, muscle contraction does not necessarily mean muscle shortening because muscle tension can be produced without changes in musc ...

depends upon the movement of calcium, sodium and potassium through ion channels in the cell membrane and T-tubule

T-tubules (transverse tubules) are extensions of the cell membrane that penetrate into the center of skeletal and cardiac muscle cells. With membranes that contain large concentrations of ion channels, transporters, and pumps, T-tubules permi ...

s.

Transition metal

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. The lanthanide and actinid ...

s are usually present as trace element

__NOTOC__

A trace element is a chemical element of a minute quantity, a trace amount, especially used in referring to a micronutrient, but is also used to refer to minor elements in the composition of a rock, or other chemical substance.

In nutr ...

s in organisms, with zinc

Zinc is a chemical element; it has symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic tabl ...

and iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

being most abundant of those. Metal cofactors are bound tightly to specific sites in proteins; although enzyme cofactors can be modified during catalysis, they always return to their original state by the end of the reaction catalyzed. Metal micronutrients are taken up into organisms by specific transporters and bind to storage proteins such as ferritin

Ferritin is a universal intracellular and extracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. The protein is produced by almost all living organisms, including archaea, bacteria, algae, higher plants, and animals. ...

or metallothionein

Metallothionein (MT) is a family of cysteine-rich, low molecular weight (MW ranging from 500 to 14000 Da) proteins. They are localized to the membrane of the Golgi apparatus. MTs have the capacity to bind both physiological (such as zinc, copp ...

when not in use.

Catabolism

Catabolism is the set of metabolic processes that break down large molecules. These include breaking down and oxidizing food molecules. The purpose of the catabolic reactions is to provide the energy and components needed by anabolic reactions which build molecules. The exact nature of these catabolic reactions differ from organism to organism, and organisms can be classified based on their sources of energy, hydrogen, and carbon (theirprimary nutritional groups

Primary nutritional groups are groups of organisms, divided in relation to the nutrition mode according to the sources of energy and carbon, needed for living, growth and reproduction. The sources of energy can be light or chemical compounds; the ...

), as shown in the table below. Organic molecules are used as a source of hydrogen atoms or electrons by organotroph

An organotroph is an organism that obtains hydrogen or electrons from organic substrates. This term is used in microbiology to classify and describe organisms based on how they obtain electrons for their respiration processes. Some organotrophs s ...

s, while lithotroph

Lithotrophs are a diverse group of organisms using an inorganic substrate (usually of mineral origin) to obtain reducing equivalents for use in biosynthesis (e.g., carbon fixation, carbon dioxide fixation) or energy conservation (i.e., Adenosine tr ...

s use inorganic substrates. Whereas phototroph

Phototrophs () are organisms that carry out photon capture to produce complex organic compounds (e.g. carbohydrates) and acquire energy. They use the energy from light to carry out various cellular metabolic processes. It is a list of common m ...

s convert sunlight to chemical energy

Chemical energy is the energy of chemical substances that is released when the substances undergo a chemical reaction and transform into other substances. Some examples of storage media of chemical energy include batteries, Schmidt-Rohr, K. (20 ...

, chemotroph

A chemotroph is an organism that obtains energy by the oxidation of electron donors in their environments. These molecules can be organic ( chemoorganotrophs) or inorganic ( chemolithotrophs). The chemotroph designation is in contrast to phot ...

s depend on redox

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is t ...

reactions that involve the transfer of electrons from reduced donor molecules such as organic molecule

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-cont ...

s, hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

, hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

or ferrous ions to oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

or sulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ...

. In animals, these reactions involve complex organic molecule

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-cont ...

s that are broken down to simpler molecules, such as carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

and water. Photosynthetic

Photosynthesis ( ) is a Biological system, system of biological processes by which Photoautotrophism, photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical ener ...

organisms, such as plants and cyanobacteria

Cyanobacteria ( ) are a group of autotrophic gram-negative bacteria that can obtain biological energy via oxygenic photosynthesis. The name "cyanobacteria" () refers to their bluish green (cyan) color, which forms the basis of cyanobacteri ...

, use similar electron-transfer reactions to store energy absorbed from sunlight.

The most common set of catabolic reactions in animals can be separated into three main stages. In the first stage, large organic molecules, such as protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s, polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s or lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s, are digested into their smaller components outside cells. Next, these smaller molecules are taken up by cells and converted to smaller molecules, usually acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which releases some energy. Finally, the acetyl group on acetyl-CoA is oxidized to water and carbon dioxide in the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reaction, biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-Co ...

and electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules which transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples th ...

, releasing more energy while reducing the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a Cofactor (biochemistry), coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cell (biology), cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphat ...

(NAD+) into NADH.

Digestion

Macromolecules cannot be directly processed by cells. Macromolecules must be broken into smaller units before they can be used in cell metabolism. Different classes of enzymes are used to digest these polymers. Thesedigestive enzyme

Digestive enzymes take part in the chemical process of digestion, which follows the mechanical process of digestion. Food consists of macromolecules of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats that need to be broken down chemically by digestive enzymes ...

s include protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s that digest proteins into amino acids, as well as glycoside hydrolase

In biochemistry, glycoside hydrolases (also called glycosidases or glycosyl hydrolases) are a class of enzymes which catalysis, catalyze the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds in polysaccharide, complex sugars. They are extremely common enzymes, wi ...

s that digest polysaccharides into simple sugars known as monosaccharides

Monosaccharides (from Greek ''monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhydr ...

.

Microbes simply secrete digestive enzymes into their surroundings, while animals only secrete these enzymes from specialized cells in their guts, including the stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

and pancreas

The pancreas (plural pancreases, or pancreata) is an Organ (anatomy), organ of the Digestion, digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdominal cavity, abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a ...

, and in salivary gland

The salivary glands in many vertebrates including mammals are exocrine glands that produce saliva through a system of ducts. Humans have three paired major salivary glands ( parotid, submandibular, and sublingual), as well as hundreds of min ...

s. The amino acids or sugars released by these extracellular enzymes are then pumped into cells by active transport

In cellular biology, active transport is the movement of molecules or ions across a cell membrane from a region of lower concentration to a region of higher concentration—against the concentration gradient. Active transport requires cellula ...

proteins.

Energy from organic compounds

Carbohydrate catabolism is the breakdown of carbohydrates into smaller units. Carbohydrates are usually taken into cells after they have been digested intomonosaccharide

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhy ...

s such as glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

and fructose

Fructose (), or fruit sugar, is a Ketose, ketonic monosaccharide, simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and gal ...

. Once inside, the major route of breakdown is glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvic acid, pyruvate and, in most organisms, occurs in the liquid part of cells (the cytosol). The Thermodynamic free energy, free energy released in this process is used to form ...

, in which glucose is converted into pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic ...

. This process generates the energy-conveying molecule NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an ade ...

from NAD+, and generates ATP from ADP for use in powering many processes within the cell. Pyruvate is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways, but the majority is converted to acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidation, o ...

and fed into the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reaction, biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-Co ...

, which enables more ATP production by means of oxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation(UK , US : or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation, is the metabolic pathway in which Cell (biology), cells use enzymes to Redox, oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order ...

. This oxidation consumes molecular oxygen and releases water and the waste product carbon dioxide. When oxygen is lacking, or when pyruvate is temporarily produced faster than it can be consumed by the citric acid cycle (as in intense muscular exertion), pyruvate is converted to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH or LD) is an enzyme found in nearly all living cells. LDH catalyzes the conversion of pyruvic acid, pyruvate to lactic acid, lactate and back, as it converts NAD+ to NADH and back. A dehydrogenase is an enzyme that t ...

, a process that also oxidizes NADH back to NAD+ for re-use in further glycolysis, allowing energy production to continue. The lactate is later converted back to pyruvate for ATP production where energy is needed, or back to glucose in the Cori cycle

The Cori cycle (also known as the lactic acid cycle), named after its discoverers, Carl Ferdinand Cori and Gerty Cori, is a metabolic pathway in which lactic acid, lactate, produced by anaerobic glycolysis in muscles, is transported to the liver ...

. An alternative route for glucose breakdown is the pentose phosphate pathway

The pentose phosphate pathway (also called the phosphogluconate pathway and the hexose monophosphate shunt or HMP shunt) is a metabolic pathway parallel to glycolysis. It generates NADPH and pentoses (five-carbon sugars) as well as ribose 5-ph ...

, which produces less energy but supports anabolism

Anabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that construct macromolecules like DNA or RNA from smaller units. These reactions require energy, known also as an Endergonic reaction, endergonic process. Anabolism is the building-up aspect of metabo ...

(biomolecule synthesis). This pathway reduces the coenzyme NADP+ to NADPH and produces pentose

In chemistry, a pentose is a monosaccharide (simple sugar) with five carbon atoms. The chemical formula of many pentoses is , and their molecular weight is 150.13 g/mol.ribose 5-phosphate

Ribose 5-phosphate (R5P) is both a product and an intermediate of the pentose phosphate pathway. The last step of the oxidative reactions in the pentose phosphate pathway is the production of ribulose 5-phosphate. Depending on the body's state, ...

for synthesis of many biomolecules such as nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s and aromatic amino acid

An aromatic amino acid is an amino acid that includes an aromaticity, aromatic ring.

Among the 20 standard amino acids, histidine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, tyrosine, are classified as aromatic.

Properties and function Optical properties

Ar ...

s.

Fats are catabolized by

Fats are catabolized by hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

to free fatty acids and glycerol. The glycerol enters glycolysis and the fatty acids are broken down by beta oxidation

In biochemistry and metabolism, beta oxidation (also β-oxidation) is the catabolic process by which fatty acid molecules are broken down in the cytosol in prokaryotes and in the mitochondria in eukaryotes to generate acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA enter ...

to release acetyl-CoA, which then is fed into the citric acid cycle. Fatty acids release more energy upon oxidation than carbohydrates. Steroids are also broken down by some bacteria in a process similar to beta oxidation, and this breakdown process involves the release of significant amounts of acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, and pyruvate, which can all be used by the cell for energy. ''M. tuberculosis'' can also grow on the lipid cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

as a sole source of carbon, and genes involved in the cholesterol-use pathway(s) have been validated as important during various stages of the infection lifecycle of ''M. tuberculosis''.

Amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s are either used to synthesize proteins and other biomolecules, or oxidized to urea

Urea, also called carbamide (because it is a diamide of carbonic acid), is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two Amine, amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest am ...

and carbon dioxide to produce energy. The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase

Transaminases or aminotransferases are enzymes that catalyze a transamination reaction between an amino acid and an α-keto acid. They are important in the synthesis of amino acids, which form proteins.

Function and mechanism

An amino acid con ...

. The amino group is fed into the urea cycle

The urea cycle (also known as the ornithine cycle) is a cycle of biochemical reactions that produces urea (NH2)2CO from ammonia (NH3). Animals that use this cycle, mainly amphibians and mammals, are called ureotelic.

The urea cycle converts highl ...

, leaving a deaminated carbon skeleton in the form of a keto acid

In organic chemistry, keto acids or ketoacids (also called oxo acids or oxoacids) are organic compounds that contain a carboxylic acid group () and a ketone group ().Franz Dietrich Klingler, Wolfgang Ebertz "Oxocarboxylic Acids" in Ullmann's En ...

. Several of these keto acids are intermediates in the citric acid cycle, for example α- ketoglutarate formed by deamination of glutamate

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; known as glutamate in its anionic form) is an α-amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a Essential amino acid, non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that ...

. The glucogenic amino acid

A glucogenic amino acid (or glucoplastic amino acid) is an amino acid that can be converted into glucose through gluconeogenesis. This is in contrast to the ketogenic amino acids, which are converted into ketone bodies.

The production of glucose ...

s can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis

Gluconeogenesis (GNG) is a metabolic pathway that results in the biosynthesis of glucose from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates. It is a ubiquitous process, present in plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. In verte ...

.

Energy transformations

Oxidative phosphorylation

In oxidative phosphorylation, the electrons removed from organic molecules in areas such as the citric acid cycle are transferred to oxygen and the energy released is used to make ATP. This is done ineukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s by a series of proteins in the membranes of mitochondria called the electron transport chain

An electron transport chain (ETC) is a series of protein complexes and other molecules which transfer electrons from electron donors to electron acceptors via redox reactions (both reduction and oxidation occurring simultaneously) and couples th ...

. In prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s, these proteins are found in the cell's inner membrane. These proteins use the energy from reduced molecules like NADH to pump proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

s across a membrane.

Pumping protons out of the mitochondria creates a proton concentration difference across the membrane and generates an

Pumping protons out of the mitochondria creates a proton concentration difference across the membrane and generates an electrochemical gradient