McCarthyism Records on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of

McCarthy's involvement in these issues began publicly with a speech he made on

McCarthy's involvement in these issues began publicly with a speech he made on

In the federal government, President Truman's Executive Order 9835 initiated a program of loyalty reviews for federal employees in 1947. It called for dismissal if there were "reasonable grounds ... for belief that the person involved is disloyal to the Government of the United States." Truman, a Democrat, was probably reacting in part to the Republican sweep in the 1946 Congressional election and felt a need to counter growing criticism from conservatives and anti-communists.

When President

In the federal government, President Truman's Executive Order 9835 initiated a program of loyalty reviews for federal employees in 1947. It called for dismissal if there were "reasonable grounds ... for belief that the person involved is disloyal to the Government of the United States." Truman, a Democrat, was probably reacting in part to the Republican sweep in the 1946 Congressional election and felt a need to counter growing criticism from conservatives and anti-communists.

When President

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover designed President Truman's loyalty-security program, and its background investigations of employees were carried out by FBI agents. This was a major assignment that led to the number of agents in the bureau being increased from 3,559 in 1946 to 7,029 in 1952. Hoover's sense of the communist threat and the standards of evidence applied by his bureau resulted in thousands of government workers losing their jobs. Due to Hoover's insistence upon keeping the identity of his informers secret, most subjects of loyalty-security reviews were not allowed to cross-examine or know the identities of those who accused them. In many cases, they were not even told of what they were accused.

Hoover's influence extended beyond federal government employees and beyond the loyalty-security programs. The records of loyalty review hearings and investigations were supposed to be confidential, but Hoover routinely gave evidence from them to congressional committees such as HUAC.

From 1951 to 1955, the FBI operated a secret " Responsibilities Program" that distributed anonymous documents with evidence from FBI files of communist affiliations on the part of teachers, lawyers, and others. Many people accused in these "blind memoranda" were fired without any further process.

The FBI engaged in a number of illegal practices in its pursuit of information on communists, including burglaries, opening mail, and illegal wiretaps.Cox and Theoharis (1988), p. 312. The members of the left-wing National Lawyers Guild (NLG) were among the few attorneys who were willing to defend clients in communist-related cases, and this made the NLG a particular target of Hoover's; the office of the NLG was burgled by the FBI at least 14 times between 1947 and 1951. Among other purposes, the FBI used its illegally obtained information to alert prosecuting attorneys about the planned legal strategies of NLG defense lawyers.

The FBI also used illegal undercover operations to disrupt communist and other dissident political groups. In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover designed President Truman's loyalty-security program, and its background investigations of employees were carried out by FBI agents. This was a major assignment that led to the number of agents in the bureau being increased from 3,559 in 1946 to 7,029 in 1952. Hoover's sense of the communist threat and the standards of evidence applied by his bureau resulted in thousands of government workers losing their jobs. Due to Hoover's insistence upon keeping the identity of his informers secret, most subjects of loyalty-security reviews were not allowed to cross-examine or know the identities of those who accused them. In many cases, they were not even told of what they were accused.

Hoover's influence extended beyond federal government employees and beyond the loyalty-security programs. The records of loyalty review hearings and investigations were supposed to be confidential, but Hoover routinely gave evidence from them to congressional committees such as HUAC.

From 1951 to 1955, the FBI operated a secret " Responsibilities Program" that distributed anonymous documents with evidence from FBI files of communist affiliations on the part of teachers, lawyers, and others. Many people accused in these "blind memoranda" were fired without any further process.

The FBI engaged in a number of illegal practices in its pursuit of information on communists, including burglaries, opening mail, and illegal wiretaps.Cox and Theoharis (1988), p. 312. The members of the left-wing National Lawyers Guild (NLG) were among the few attorneys who were willing to defend clients in communist-related cases, and this made the NLG a particular target of Hoover's; the office of the NLG was burgled by the FBI at least 14 times between 1947 and 1951. Among other purposes, the FBI used its illegally obtained information to alert prosecuting attorneys about the planned legal strategies of NLG defense lawyers.

The FBI also used illegal undercover operations to disrupt communist and other dissident political groups. In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by

McCarthyism was supported by a variety of groups, including the

McCarthyism was supported by a variety of groups, including the

In the film industry, more than 300 actors, authors, and directors were denied work in the U.S. through the unofficial Hollywood blacklist. Blacklists were at work throughout the entertainment industry, in universities and schools at all levels, in the legal profession, and in many other fields. A port-security program initiated by the Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless of cargo or destination. As with other loyalty-security reviews of McCarthyism, the identities of any accusers and even the nature of any accusations were typically kept secret from the accused. Nearly 3,000 seamen and longshoremen lost their jobs due to this program alone.

Some of the notable people who were blacklisted or suffered some other persecution during McCarthyism include:

* Larry Adler, musician

* Nelson Algren, writer

* Lucille Ball, actress, model, and film studio executive.

*

In the film industry, more than 300 actors, authors, and directors were denied work in the U.S. through the unofficial Hollywood blacklist. Blacklists were at work throughout the entertainment industry, in universities and schools at all levels, in the legal profession, and in many other fields. A port-security program initiated by the Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless of cargo or destination. As with other loyalty-security reviews of McCarthyism, the identities of any accusers and even the nature of any accusations were typically kept secret from the accused. Nearly 3,000 seamen and longshoremen lost their jobs due to this program alone.

Some of the notable people who were blacklisted or suffered some other persecution during McCarthyism include:

* Larry Adler, musician

* Nelson Algren, writer

* Lucille Ball, actress, model, and film studio executive.

*

". ''The New York Times'', August 11, 1989. Accessed March 7, 2011. * Garson Kanin, writer and director *

One of the most influential opponents of McCarthyism was the famed CBS newscaster and analyst Edward R. Murrow. On October 20, 1953, Murrow's show '' See It Now'' aired an episode about the dismissal of

One of the most influential opponents of McCarthyism was the famed CBS newscaster and analyst Edward R. Murrow. On October 20, 1953, Murrow's show '' See It Now'' aired an episode about the dismissal of

online

* Selverstone, Marc J. "A Literature So Immense: The Historiography of Anticommunism." ''Organization of American Historians Magazine of History'' 24.4 (2010): 7–11.

The Meaning of McCarthyism

' (1965). excerpts from primary and secondary sources * Lichtman, Robert M. ''The Supreme Court and McCarthy-Era Repression: One Hundred Decisions.'' Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2012. * McDaniel, Rodger. ''Dying for Joe McCarthy's Sins: The Suicide of Wyoming Senator Lester Hunt.'' WordsWorth, 2013. * * * * * Storrs, Landon R.Y., ''The Second Red Scare and the Unmaking of the New Deal Left.'' Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013. *

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to transform the established social order and its structures of power, authority, hierarchy, and social norms. Sub ...

and treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, especially when related to anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

, communism

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term originally referred to the controversial practices and policies of U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy

Joseph Raymond McCarthy (November 14, 1908 – May 2, 1957) was an American politician who served as a Republican U.S. Senator from the state of Wisconsin from 1947 until his death in 1957. Beginning in 1950, McCarthy became the most visi ...

, and has its origins in the period in the United States known as the Second Red Scare

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origina ...

, lasting from the late 1940s through the 1950s. It was characterized by heightened political repression

Political repression is the act of a state entity controlling a citizenry by force for political reasons, particularly for the purpose of restricting or preventing the citizenry's ability to take part in the political life of a society, thereb ...

and persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

of left-wing individuals, and a campaign spreading fear of alleged communist and socialist influence on American institutions and of espionage by Soviet agents. After the mid-1950s, McCarthyism began to decline, mainly due to Joseph McCarthy's gradual loss of public popularity and credibility after several of his accusations were found to be false, and sustained opposition from the U.S. Supreme Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitution ...

on human rights grounds. The Warren Court made a series of rulings on civil and political rights that overturned several key laws and legislative directives, and helped bring an end to the Second Red Scare. Historians have suggested since the 1980s that as McCarthy's involvement was less central than that of others, a different and more accurate term should be used instead that more accurately conveys the breadth of the phenomenon, and that the term ''McCarthyism'' is now outdated. Ellen Schrecker has suggested that ''Hooverism'' after FBI Head J. Edgar Hoover is more appropriate. Others, including Stanley Kutler, have instead suggested the term McCarranism after Senator Pat McCarran of Nevada, a key legislative figure in the movement.

What would become known as the McCarthy era began before McCarthy's rise to national fame. Following the breakdown of the wartime East-West alliance with the Soviet Union, and with many remembering the First Red Scare, President Harry S. Truman signed an executive order in 1947 to screen federal employees for possible association with organizations deemed "totalitarian, fascist, communist, or subversive", or advocating "to alter the form of Government of the United States by unconstitutional means." The following year, the Czech coup

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

*Czech, ...

by the Czechoslovakian Communist Party heightened concern in the West about Communist parties seizing power and the possibility of subversion. In 1949, a high-level State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

official was convicted of perjury in a case of espionage, and the Soviet Union tested a nuclear bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

. The Korean War started the next year, significantly raising tensions and fears of impending communist upheavals in the United States. In a speech in February 1950, McCarthy claimed to have a list of members of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

working in the State Department, which attracted substantial press attention, and the term ''McCarthyism'' was published for the first time in late March of that year in '' The Christian Science Monitor'', along with a political cartoon by Herblock in '' The Washington Post''. The term has since taken on a broader meaning, describing the excesses of similar efforts to crack down on alleged "subversive" elements. In the early 21st century, the term is used more generally to describe reckless and unsubstantiated accusations of treason and far-left extremism, along with demagogic personal attacks on the character and patriotism of political adversaries.

The primary targets for persecution were government employees, prominent figures in the entertainment industry, academics, left-wing politicians, and labor union activists. Suspicions were often given credence despite inconclusive and questionable evidence, and the level of threat posed by a person's real or supposed leftist associations and beliefs were often exaggerated. Many people suffered loss of employment and the destruction of their careers and livelihoods as a result of the crackdowns on suspected communists, and some were outright imprisoned. Most of these reprisals were initiated by trial verdicts that were later overturned, laws that were later struck down as unconstitutional, dismissals for reasons later declared illegal or actionable

A cause of action or right of action, in law, is a set of facts sufficient to justify suing to obtain money or property, or to justify the enforcement of a legal right against another party. The term also refers to the legal theory upon which a p ...

, and extra-judiciary procedures, such as informal blacklists by employers and public institutions, that would come into general disrepute, though by then many lives had been ruined. The most notable examples of McCarthyism include the investigations of alleged communists that were conducted by Senator McCarthy, and the hearings conducted by the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

(HUAC).

Origins

President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9835 of March 21, 1947, required that all federal civil-service employees be screened for "loyalty". The order said that one basis for determining disloyalty would be a finding of "membership in, affiliation with or sympathetic association" with any organization determined by the attorney general to be "totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive" or advocating or approving the forceful denial of constitutional rights to other persons or seeking "to alter the form of Government of the United States by unconstitutional means". The historical period that came to be known as the McCarthy era began well before Joseph McCarthy's own involvement in it. Many factors contributed to McCarthyism, some of them with roots in the First Red Scare (1917–20), inspired by communism's emergence as a recognized political force and widespread social disruption in the United States related to unionizing and anarchist activities. Owing in part to its success in organizing labor unions and its early opposition to fascism, and offering an alternative to the ills of capitalism during theGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, the Communist Party of the United States increased its membership through the 1930s, reaching a peak of about 75,000 members in 1940–41. While the United States was engaged in World War II and allied with the Soviet Union, the issue of anti-communism was largely muted. With the end of World War II, the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

began almost immediately, as the Soviet Union installed communist puppet régime

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sovere ...

s in areas it had occupied across Central and Eastern Europe. In a March 1947 address to Congress, Truman enunciated a new foreign policy doctrine that committed the United States to opposing Soviet geopolitical expansion. This doctrine came to be known as the Truman Doctrine, and it guided United States support for anti-communist forces in Greece and later in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

and elsewhere.

Although the Igor Gouzenko and Elizabeth Bentley

Elizabeth Terrill Bentley (January 1, 1908 – December 3, 1963) was an American spy and member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). She served the Soviet Union from 1938 to 1945 until she defected from the Communist Party and Soviet intelligenc ...

affairs had raised the issue of Soviet espionage in 1945, events in 1949 and 1950 sharply increased the sense of threat in the United States related to communism. The Soviet Union tested an atomic bomb in 1949, earlier than many analysts had expected, raising the stakes in the Cold War. That same year, Mao Zedong's communist army gained control of mainland China despite heavy American financial support of the opposing Kuomintang. In 1950, the Korean War began, pitting U.S., U.N., and South Korean forces against communists from North Korea and China.

During the following year, evidence of increased sophistication in Soviet Cold War espionage activities was found in the West. In January 1950, Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in con ...

, a high-level State Department official, was convicted of perjury. Hiss was in effect found guilty of espionage; the statute of limitations had run out for that crime, but he was convicted of having perjured himself when he denied that charge in earlier testimony before the HUAC. In Britain, Klaus Fuchs

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs (29 December 1911 – 28 January 1988) was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly aft ...

confessed to committing espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union while working on the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos National Laboratory during the War. Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested in 1950 in the United States on charges of stealing atomic-bomb secrets for the Soviets, and were executed in 1953.

Other forces encouraged the rise of McCarthyism. The more conservative politicians in the United States had historically referred to progressive reforms, such as child labor laws and women's suffrage, as "communist" or "Red plots", trying to raise fears against such changes. They used similar terms during the 1930s and the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

when opposing the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

policies of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Many conservatives equated the New Deal with socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

or Communism, and thought the policies were evidence of too much influence by allegedly communist policy makers in the Roosevelt administration. In general, the vaguely defined danger of "Communist influence" was a more common theme in the rhetoric of anti-communist politicians than was espionage or any other specific activity.

McCarthy's involvement in these issues began publicly with a speech he made on

McCarthy's involvement in these issues began publicly with a speech he made on Lincoln Day

A Lincoln Dinner is an annual celebration and fundraising event of many state and county organizations of the Republican Party in the United States. It is held annually in February or March depending on the county and often features a well known s ...

, February 9, 1950, to the Republican Women's Club of Wheeling, West Virginia. He brandished a piece of paper, which he claimed contained a list of known communists working for the State Department. McCarthy is usually quoted as saying: "I have here in my hand a list of 205—a list of names that were made known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who nevertheless are still working and shaping policy in the State Department." This speech resulted in a flood of press attention to McCarthy and helped establish his path to becoming one of the most recognized politicians in the United States.

The first recorded use of the term "McCarthyism" was in the ''Christian Science Monitor'' on March 28, 1950 ("Their little spree with McCarthyism is no aid to consultation"). The paper became one of the earliest and most consistent critics of the Senator. The next recorded use happened on the following day, in a political cartoon by ''Washington Post'' editorial cartoonist Herbert Block (Herblock). The cartoon depicts four leading Republicans trying to push an elephant (the traditional symbol of the Republican Party

Republican Party is a name used by many political parties around the world, though the term most commonly refers to the United States' Republican Party.

Republican Party may also refer to:

Africa

*Republican Party (Liberia)

* Republican Part ...

) to stand on a platform atop a teetering stack of ten tar buckets, the topmost of which is labeled "McCarthyism". Block later wrote:

"nothing asparticularly ingenious about the term, which is simply used to represent a national affliction that can hardly be described in any other way. If anyone has a prior claim on it, he's welcome to the word and to the junior senator from Wisconsin along with it. I will also throw in a set of free dishes and a case of soap."

Institutions

A number of anti-communist committees, panels, and "loyalty review boards" in federal, state, and local governments, as well as many private agencies, carried out investigations for small and large companies concerned about possible Communists in their work forces. In Congress, the primary bodies that investigated Communist activities were the HUAC, the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee, and the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Between 1949 and 1954, a total of 109 investigations were carried out by these and other committees of Congress. On December 2, 1954, the United States Senate voted 67 to 22 to condemn McCarthy for "conduct that tends to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute".Executive branch

Loyalty-security reviews

In the federal government, President Truman's Executive Order 9835 initiated a program of loyalty reviews for federal employees in 1947. It called for dismissal if there were "reasonable grounds ... for belief that the person involved is disloyal to the Government of the United States." Truman, a Democrat, was probably reacting in part to the Republican sweep in the 1946 Congressional election and felt a need to counter growing criticism from conservatives and anti-communists.

When President

In the federal government, President Truman's Executive Order 9835 initiated a program of loyalty reviews for federal employees in 1947. It called for dismissal if there were "reasonable grounds ... for belief that the person involved is disloyal to the Government of the United States." Truman, a Democrat, was probably reacting in part to the Republican sweep in the 1946 Congressional election and felt a need to counter growing criticism from conservatives and anti-communists.

When President Dwight Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

took office in 1953, he strengthened and extended Truman's loyalty review program, while decreasing the avenues of appeal available to dismissed employees. Hiram Bingham, chairman of the Civil Service Commission Loyalty Review Board

Loyalty, in general use, is a Fixation (psychology), devotion and faithfulness to a nation, cause, philosophy, country, group, or person. Philosophers disagree on what can be an object of loyalty, as some argue that loyalty is strictly interpers ...

, referred to the new rules he was obliged to enforce as "just not the American way of doing things." The following year, J. Robert Oppenheimer, scientific director of the Manhattan Project that built the first atomic bomb, then working as a consultant to the Atomic Energy Commission, was stripped of his security clearance after a four-week hearing. Oppenheimer had received a top-secret clearance in 1947, but was denied clearance in the harsher climate of 1954.

Similar loyalty reviews were established in many state and local government offices and some private industries across the nation. In 1958, an estimated one of every five employees in the United States was required to pass some sort of loyalty review. Once a person lost a job due to an unfavorable loyalty review, finding other employment could be very difficult. "A man is ruined everywhere and forever," in the words of the chairman of President Truman's Loyalty Review Board. "No responsible employer would be likely to take a chance in giving him a job."

The Department of Justice started keeping a list of organizations that it deemed subversive beginning in 1942. This list was first made public in 1948, when it included 78 groups. At its longest, it comprised 154 organizations, 110 of them identified as Communist. In the context of a loyalty review, membership in a listed organization was meant to raise a question, but not to be considered proof of disloyalty. One of the most common causes of suspicion was membership in the Washington Bookshop Association, a left-leaning organization that offered lectures on literature, classical music concerts, and discounts on books.

J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover designed President Truman's loyalty-security program, and its background investigations of employees were carried out by FBI agents. This was a major assignment that led to the number of agents in the bureau being increased from 3,559 in 1946 to 7,029 in 1952. Hoover's sense of the communist threat and the standards of evidence applied by his bureau resulted in thousands of government workers losing their jobs. Due to Hoover's insistence upon keeping the identity of his informers secret, most subjects of loyalty-security reviews were not allowed to cross-examine or know the identities of those who accused them. In many cases, they were not even told of what they were accused.

Hoover's influence extended beyond federal government employees and beyond the loyalty-security programs. The records of loyalty review hearings and investigations were supposed to be confidential, but Hoover routinely gave evidence from them to congressional committees such as HUAC.

From 1951 to 1955, the FBI operated a secret " Responsibilities Program" that distributed anonymous documents with evidence from FBI files of communist affiliations on the part of teachers, lawyers, and others. Many people accused in these "blind memoranda" were fired without any further process.

The FBI engaged in a number of illegal practices in its pursuit of information on communists, including burglaries, opening mail, and illegal wiretaps.Cox and Theoharis (1988), p. 312. The members of the left-wing National Lawyers Guild (NLG) were among the few attorneys who were willing to defend clients in communist-related cases, and this made the NLG a particular target of Hoover's; the office of the NLG was burgled by the FBI at least 14 times between 1947 and 1951. Among other purposes, the FBI used its illegally obtained information to alert prosecuting attorneys about the planned legal strategies of NLG defense lawyers.

The FBI also used illegal undercover operations to disrupt communist and other dissident political groups. In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover designed President Truman's loyalty-security program, and its background investigations of employees were carried out by FBI agents. This was a major assignment that led to the number of agents in the bureau being increased from 3,559 in 1946 to 7,029 in 1952. Hoover's sense of the communist threat and the standards of evidence applied by his bureau resulted in thousands of government workers losing their jobs. Due to Hoover's insistence upon keeping the identity of his informers secret, most subjects of loyalty-security reviews were not allowed to cross-examine or know the identities of those who accused them. In many cases, they were not even told of what they were accused.

Hoover's influence extended beyond federal government employees and beyond the loyalty-security programs. The records of loyalty review hearings and investigations were supposed to be confidential, but Hoover routinely gave evidence from them to congressional committees such as HUAC.

From 1951 to 1955, the FBI operated a secret " Responsibilities Program" that distributed anonymous documents with evidence from FBI files of communist affiliations on the part of teachers, lawyers, and others. Many people accused in these "blind memoranda" were fired without any further process.

The FBI engaged in a number of illegal practices in its pursuit of information on communists, including burglaries, opening mail, and illegal wiretaps.Cox and Theoharis (1988), p. 312. The members of the left-wing National Lawyers Guild (NLG) were among the few attorneys who were willing to defend clients in communist-related cases, and this made the NLG a particular target of Hoover's; the office of the NLG was burgled by the FBI at least 14 times between 1947 and 1951. Among other purposes, the FBI used its illegally obtained information to alert prosecuting attorneys about the planned legal strategies of NLG defense lawyers.

The FBI also used illegal undercover operations to disrupt communist and other dissident political groups. In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute communists. At this time, he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO. COINTELPRO actions included planting forged documents to create the suspicion that a key person was an FBI informer, spreading rumors through anonymous letters, leaking information to the press, calling for IRS audits, and the like. The COINTELPRO program remained in operation until 1971.

Historian Ellen Schrecker calls the FBI "the single most important component of the anti-communist crusade" and writes: "Had observers known in the 1950s what they have learned since the 1970s, when the Freedom of Information Act opened the Bureau's files, 'McCarthyism' would probably be called 'Hooverism'."

Allen Dulles and the CIA

In March 1950, McCarthy had initiated a series of investigations into potential infiltration of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) by communist agents and came up with a list of security risks that matched one previously compiled by the Agency itself. At the request of CIA directorAllen Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles (, ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he ov ...

, President Eisenhower demanded that McCarthy discontinue issuing subpoenas against the CIA. Documents made public in 2004 revealed that the CIA, under Dulles' orders, had broken into McCarthy's Senate office and fed disinformation to him in order to discredit him and stop his investigation from proceeding any further.

Congress

House Committee on Un-American Activities

The House Committee on Un-American Activities—commonly referred to as the HUAC—was the most prominent and active government committee involved in anti-communist investigations. Formed in 1938 and known as the Dies Committee, named for Rep. Martin Dies, who chaired it until 1944, HUAC investigated a variety of "activities", including those of German-American Nazis during World War II. The committee soon focused on Communism, beginning with an investigation into Communists in theFederal Theatre Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United ...

in 1938. A significant step for HUAC was its investigation of the charges of espionage brought against Alger Hiss in 1948. This investigation ultimately resulted in Hiss's trial and conviction for perjury, and convinced many of the usefulness of congressional committees for uncovering Communist subversion.

HUAC achieved its greatest fame and notoriety with its investigation into the Hollywood film industry. In October 1947, the committee began to subpoena screenwriters, directors, and other movie-industry professionals to testify about their known or suspected membership in the Communist Party, association with its members, or support of its beliefs. At these testimonies, this question was asked: "Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party of the United States?" Among the first film industry witnesses subpoenaed by the committee were ten who decided not to cooperate. These men, who became known as the " Hollywood Ten", cited the First Amendment's guarantee of free speech and free assembly, which they believed legally protected them from being required to answer the committee's questions. This tactic failed, and the ten were sentenced to prison for contempt of Congress

Contempt of Congress is the act of obstructing the work of the United States Congress or one of its committees. Historically, the bribery of a U.S. senator or U.S. representative was considered contempt of Congress. In modern times, contempt of Co ...

. Two of them were sentenced to six months, the rest to a year.

In the future, witnesses (in the entertainment industries and otherwise) who were determined not to cooperate with the committee would claim their Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination. William Grooper and Rockwell Kent, the only two visual artists to be questioned by McCarthy, both took this approach, and emerged relatively unscathed by the experience. However, while this usually protected witnesses from a contempt-of-Congress citation, it was considered grounds for dismissal by many government and private-industry employers. The legal requirements for Fifth Amendment protection were such that a person could not testify about his own association with the Communist Party and then refuse to "name names" of colleagues with communist affiliations. Thus, many faced a choice between "crawl ngthrough the mud to be an informer," as actor Larry Parks put it, or becoming known as a "Fifth Amendment Communist"—an epithet often used by Senator McCarthy.

Senate committees

In the Senate, the primary committee for investigating communists was the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS), formed in 1950 and charged with ensuring the enforcement of laws relating to "espionage, sabotage, and the protection of the internal security of the United States". The SISS was headed by Democrat Pat McCarran and gained a reputation for careful and extensive investigations. This committee spent a year investigating Owen Lattimore and other members of the Institute of Pacific Relations. As had been done numerous times before, the collection of scholars and diplomats associated with Lattimore (the so-called China Hands) were accused of "losing China", and while some evidence of pro-communist attitudes was found, nothing supported McCarran's accusation that Lattimore was "a conscious and articulate instrument of the Soviet conspiracy". Lattimore was charged with perjuring himself before the SISS in 1952. After many of the charges were rejected by a federal judge and one of the witnesses confessed to perjury, the case was dropped in 1955. McCarthy headed the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 1953 and 1954, and during that time, used it for a number of his communist-hunting investigations. McCarthy first examined allegations of communist influence in the Voice of America, and then turned to the overseas library program of the State Department. Card catalogs of these libraries were searched for works by authors McCarthy deemed inappropriate. McCarthy then recited the list of supposedly pro-communist authors before his subcommittee and the press. Yielding to the pressure, the State Department ordered its overseas librarians to remove from their shelves "material by any controversial persons, Communists,fellow traveler

The term ''fellow traveller'' (also ''fellow traveler'') identifies a person who is intellectually sympathetic to the ideology of a political organization, and who co-operates in the organization's politics, without being a formal member of that o ...

s, etc." Some libraries actually burned the newly forbidden books. Though he did not block the State Department from carrying out this order, President Eisenhower publicly criticized the initiative as well, telling the graduating class of Dartmouth College President in 1953: “Don’t join the book burners! … Don’t be afraid to go to the library and read every book so long as that document does not offend our own ideas of decency—that should be the only censorship.” The president then settled for a compromise by retaining the ban on Communist books written by Communists, while also allowing the libraries to keep books on Communism written by anti-Communists.

McCarthy's committee then began an investigation into the United States Army. This began at the Army Signal Corps laboratory at Fort Monmouth. McCarthy garnered some headlines with stories of a dangerous spy ring among the Army researchers, but ultimately nothing came of this investigation.

McCarthy next turned his attention to the case of a U.S. Army dentist who had been promoted to the rank of major despite having refused to answer questions on an Army loyalty review form. McCarthy's handling of this investigation, including a series of insults directed at a brigadier general, led to the Army–McCarthy hearings

The Army–McCarthy hearings were a series of televised hearings held by the United States Senate's Subcommittee on Investigations (April–June 1954) to investigate conflicting accusations between the United States Army and U.S. Senator Joseph ...

, with the Army and McCarthy trading charges and counter-charges for 36 days before a nationwide television audience. While the official outcome of the hearings was inconclusive, this exposure of McCarthy to the American public resulted in a sharp decline in his popularity. In less than a year, McCarthy was censured by the Senate, and his position as a prominent force in anti-communism was essentially ended.

Blacklists

On November 25, 1947, the day after the House of Representatives approved citations of contempt for the Hollywood Ten,Eric Johnston

Eric Allen Johnston (December 21, 1896 – August 22, 1963) was a business owner, president of the United States Chamber of Commerce, a Republican Party activist, president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), and a U.S. governme ...

, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, issued a press release on behalf of the heads of the major studios that came to be referred to as the Waldorf Statement. This statement announced the firing of the Hollywood Ten and stated: "We will not knowingly employ a Communist or a member of any party or group which advocates the overthrow of the government of the United States..." This marked the beginning of the Hollywood blacklist. In spite of the fact that hundreds were denied employment, the studios, producers, and other employers did not publicly admit that a blacklist existed.

At this time, private loyalty-review boards and anti-communist investigators began to appear to fill a growing demand among certain industries to certify that their employees were above reproach. Companies that were concerned about the sensitivity of their business, or which, like the entertainment industry, felt particularly vulnerable to public opinion, made use of these private services. For a fee, these teams investigated employees and questioned them about their politics and affiliations.

At such hearings, the subject usually did not have a right to the presence of an attorney, and as with HUAC, the interviewee might be asked to defend himself against accusations without being allowed to cross-examine the accuser. These agencies kept cross-referenced lists of leftist organizations, publications, rallies, charities, and the like, as well as lists of individuals who were known or suspected communists. Books such as '' Red Channels'' and newsletters such as ''Counterattack'' and ''Confidential Information'' were published to keep track of communist and leftist organizations and individuals. Insofar as the various blacklists of McCarthyism were actual physical lists, they were created and maintained by these private organizations.

Laws and arrests

Efforts to protect the United States from the perceived threat of communist subversion were particularly enabled by several federal laws. The Hatch Act of 1939 banned membership in subversive organizations, which was interpreted as being anti-labor legislation. The Hatch Act would allow for the reduction of influence of the Workers' Alliance, which was claimed to have been created by the Soviet Union based on a model of their unemployed councils. The Alien Registration Act or Smith Act of 1940 made the act of "knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the ... desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association" a criminal offense. Hundreds of communists and others were prosecuted under this law between 1941 and 1957. Eleven leaders of the Communist Party were convicted under the Smith Act in 1949 in the Foley Square trial. Ten defendants were given sentences of five years and the eleventh was sentenced to three years. The defense attorneys were cited forcontempt of court

Contempt of court, often referred to simply as "contempt", is the crime of being disobedient to or disrespectful toward a court of law and its officers in the form of behavior that opposes or defies the authority, justice, and dignity of the cour ...

and given prison sentences. In 1951, 23 other leaders of the party were indicted, including Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, a founding member of the American Civil Liberties Union. Many were convicted on the basis of testimony that was later admitted to be false. By 1957, 140 leaders and members of the Communist Party had been charged under the law, of whom 93 were convicted.

The McCarran Internal Security Act, which became law in 1950, has been described by scholar Ellen Schrecker as "the McCarthy era's only important piece of legislation" (the Smith Act technically antedated McCarthyism). However, the McCarran Act had no real effect beyond legal harassment. It required the registration of Communist organizations with the U.S. Attorney General and established the Subversive Activities Control Board The Subversive Activities Control Board (SACB) was a United States government committee to investigate Communist infiltration of American society during the 1950s Red Scare. It was the subject of a landmark United States Supreme Court decision of th ...

to investigate possible communist-action and communist-front organizations so they could be required to register. Due to numerous hearings, delays, and appeals, the act was never enforced, even with regard to the Communist Party of the United States itself, and the major provisions of the act were found to be unconstitutional in 1965 and 1967. In 1952, the Immigration and Nationality, or McCarran–Walter, Act was passed. This law allowed the government to deport immigrants or naturalized citizens engaged in subversive activities and also to bar suspected subversives from entering the country.

The Communist Control Act of 1954

The Communist Control Act of 1954 (68 Stat. 775, 50 U.S.C. §§ 841–844) is an American law signed by President Dwight Eisenhower on August 24, 1954, that outlaws the Communist Party of the United States and criminalizes membership i ...

was passed with overwhelming support in both houses of Congress after very little debate. Jointly drafted by Republican John Marshall Butler and Democrat Hubert Humphrey, the law was an extension of the Internal Security Act of 1950, and sought to outlaw the Communist Party by declaring that the party, as well as "Communist-Infiltrated Organizations" were "not entitled to any of the rights, privileges, and immunities attendant upon legal bodies." While the Communist Control Act had an odd mix of liberals and conservatives among its supporters, it never had any significant effect.

The act was successfully applied only twice. In 1954 it was used to prevent Communist Party members from appearing on the New Jersey state ballot, and in 1960, it was cited to deny the CPUSA recognition as an employer under New York state's unemployment compensation system. The '' New York Post'' called the act "a monstrosity", "a wretched repudiation of democratic principles," while '' The Nation'' accused Democratic liberals of a "neurotic, election-year anxiety to escape the charge of being 'soft on Communism' even at the expense of sacrificing constitutional rights."

Repression in the individual states

In addition to the federal laws and responding to the worries of the local opinion, several states enacted anti-communist statutes. By 1952, several states had enacted statutes against criminal anarchy, criminal syndicalism, and sedition; banned from public employment or even from receiving public aid, communists and "subversives"; asked for loyalty oaths from public servants, and severely restricted or even banned the Communist Party. In addition, six states had equivalents to the HUAC. TheCalifornia Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities California Senate Factfinding Subcommittee on Un-American Activities (CUAC) was established by the California State Legislature in 1941 as the Joint Fact-Finding Committee on UnAmerican Activities. The creation of the new joint committee (with memb ...

and the Florida Legislative Investigation Committee

The Florida Legislative Investigation Committee (commonly known as the Johns Committee) was established by the Florida Legislature in 1956, during the era of the Second Red Scare and the Lavender Scare. Like the more famous anti-Communist investi ...

were established by their respective legislatures.

Some of these states had very severe, or even extreme, laws against communism. In 1950, Michigan enacted life imprisonment for subversive propaganda; the following year, Tennessee enacted the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

for advocating the violent overthrow of the government. The death penalty for membership in the Communist Party was discussed in Texas by Governor Allan Shivers, who described it as "worse than murder."

Municipalities and counties also enacted anti-communist ordinances: Los Angeles banned any communist or "Muscovite model of police-state dictatorship" from owning arms and Birmingham, Alabama, and Jacksonville, Florida, banned any communist from being within the city's limits.

Popular support

McCarthyism was supported by a variety of groups, including the

McCarthyism was supported by a variety of groups, including the American Legion

The American Legion, commonly known as the Legion, is a non-profit organization of U.S. war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militi ...

and various other anti-communist organizations. One core element of support was a variety of militantly anti-communist women's groups such as the American Public Relations Forum

The American Public Relations Forum (APRF) was a conservative anti-communist organization for Catholic women, established in southern California in 1952 with its headquarters in Burbank. It was founded by Stephanie Williams, a San Fernando Vall ...

and the Minute Women of the U.S.A. The Minute Women of the U.S.A. was one of the largest of a number of anti-Communist women's groups that were active during the 1950s and early 1960s. Such groups, which organized American suburban housewives into anti-Communist study groups, polit ...

These organized tens of thousands of housewives into study groups, letter-writing networks, and patriotic clubs that coordinated efforts to identify and eradicate what they saw as subversion.

Although right-wing radicals were the bedrock of support for McCarthyism, they were not alone. A broad "coalition of the aggrieved" found McCarthyism attractive, or at least politically useful. Common themes uniting the coalition were opposition to internationalism, particularly the United Nations; opposition to social welfare provisions, particularly the various programs established by the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

; and opposition to efforts to reduce inequalities in the social structure of the United States.Rovere (1959), pp. 21–22.

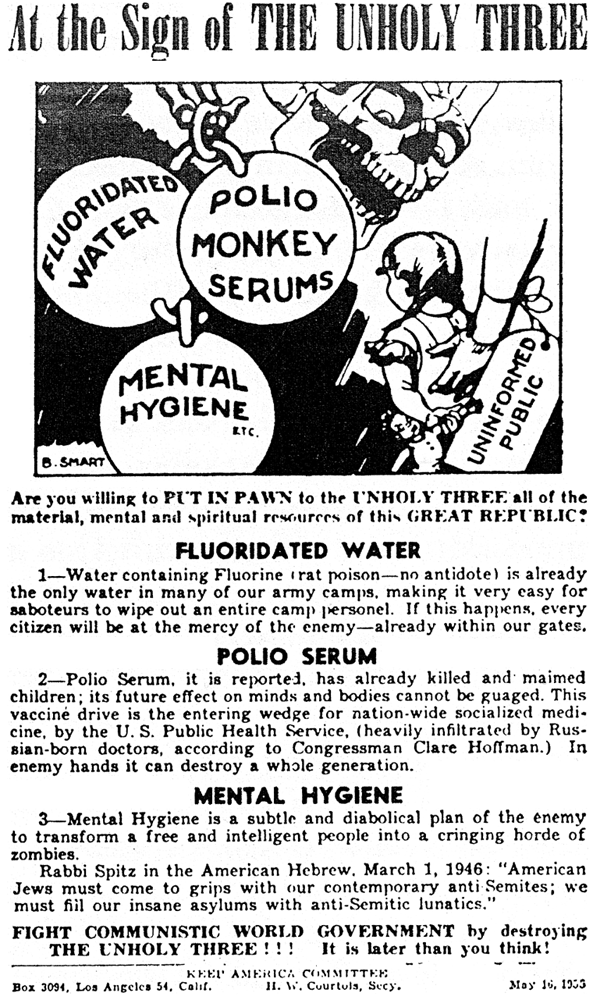

One focus of popular McCarthyism concerned the provision of public health services, particularly vaccination, mental health care services, and fluoridation, all of which were denounced by some to be communist plots to poison or brainwash the American people. Such viewpoints led to collisions between McCarthyite radicals and supporters of public-health programs, most notably in the case of the Alaska Mental Health Bill controversy of 1956.

William F. Buckley Jr., the founder of the influential conservative political magazine '' National Review'', wrote a defense of McCarthy, ''McCarthy and his Enemies'', in which he asserted that "McCarthyism ... is a movement around which men of good will and stern morality can close ranks."

In addition, as Richard Rovere points out, many ordinary Americans became convinced that there must be "no smoke without fire" and lent their support to McCarthyism. The Gallup poll found that at his peak in January 1954, 50% of the American public supported McCarthy, while 29% had an unfavorable opinion. His support fell to 34% in June 1954. Republicans tended to like what McCarthy was doing and Democrats did not, though McCarthy had significant support from traditional Democratic ethnic groups, especially Catholics, as well as many unskilled workers and small-business owners. (McCarthy himself was a Catholic.) He had very little support among union activists and Jews.

Portrayals of Communists

Those who sought to justify McCarthyism did so largely through their characterization of communism, and American communists in particular. Proponents of McCarthyism claimed that the CPUSA was so completely under Moscow's control that any American communist was a puppet of the Soviet intelligence services. This view, if restricted to the Communist Party's leadership is supported by recent documentation from the archives of the KGB as well as post-war decodes of wartime Soviet radio traffic from the Venona project, showing that Moscow provided financial support to the CPUSA and had significant influence on CPUSA policies. J. Edgar Hoover commented in a 1950 speech, "Communist members, body and soul, are the property of the Party." According to historian Richard G. Powers, McCarthy added "bogus specificity" to "sweeping accusation , gaining support among "countersubversive anticommunists" on one hand, who sought to find and punish perceived communists. On the other hand, "liberal anticommunists" believed that the Communist Party was "despicable and annoying" but ultimately politically irrelevant. President Harry Truman, who pursued the anti-Soviet Truman Doctrine, called McCarthy "the greatest asset the Kremlin has" by "torpedo ngthe bipartisan foreign policy of the United States." Historian Landon R. Y. Storrs writes that the CPUSA's "secretiveness, itsauthoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

internal structure, and the loyalty of its leaders to the Kremlin

The Kremlin ( rus, Московский Кремль, r=Moskovskiy Kreml', p=ˈmɐˈskofskʲɪj krʲemlʲ, t=Moscow Kremlin) is a fortified complex in the center of Moscow founded by the Rurik dynasty, Rurik dynasty. It is the best known of th ...

were fundamental flaws that help explain why and how it was demonized. On the other hand, most American Communists were idealists attracted by the party’s militance against various forms of social injustice." Furthermore, based on later declassified evidence, "The paradoxical lesson from several decades of scholarship is that the same organization that inspired democratic idealists in the pursuit of social justice also was secretive, authoritarian, and morally compromised by ties to the Stalin regime."

In the mid 20th century, this attitude was not confined to arch-conservatives. In 1940, the American Civil Liberties Union ejected founding member Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, saying that her membership in the Communist Party was enough to disqualify her as a civil libertarian. In the government's prosecutions of Communist Party members under the Smith Act (see above), the prosecution case was based not on specific actions or statements by the defendants, but on the premise that a commitment to violent overthrow of the government was inherent in the doctrines of Marxism–Leninism. Passages of the CPUSA constitution that specifically rejected revolutionary violence were dismissed as deliberate deception.

In addition, it was often claimed that the party didn't allow members to resign; thus someone who had been a member for a short time decades previously could be thought a current member. Many of the hearings and trials of McCarthyism featured testimony by former Communist Party members such as Elizabeth Bentley

Elizabeth Terrill Bentley (January 1, 1908 – December 3, 1963) was an American spy and member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). She served the Soviet Union from 1938 to 1945 until she defected from the Communist Party and Soviet intelligenc ...

, Louis Budenz

Louis Francis Budenz (pronounced "byew-DENZ"; July 17, 1891 – April 27, 1972) was an American activist and writer, as well as a Soviet espionage agent and head of the ''Buben group'' of spies. He began as a labor activist and became a member ...

, and Whittaker Chambers, speaking as expert witnesses.

Various historians and pundits have discussed alleged Soviet-directed infiltration of the U.S. government and the possible collaboration of high U.S. government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

officials.

Victims of McCarthyism

Estimating the number of victims of McCarthy is difficult. The number imprisoned is in the hundreds, and some ten or twelve thousand lost their jobs. In many cases, simply being subpoenaed by HUAC or one of the other committees was sufficient cause to be fired. For the vast majority, both the potential for them to do harm to the nation and the nature of their communist affiliation were tenuous. After the extremely damaging " Cambridge Five" spy scandal ( Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Kim Philby,Anthony Blunt

Anthony Frederick Blunt (26 September 1907 – 26 March 1983), styled Sir Anthony Blunt KCVO from 1956 to November 1979, was a leading British art historian and Soviet spy.

Blunt was professor of art history at the University of London, dire ...

, et al.), suspected homosexuality was also a common cause for being targeted by McCarthyism. The hunt for "sexual perverts", who were presumed to be subversive by nature, resulted in over 5,000 federal workers being fired, and thousands were harassed and denied employment. Many have termed this aspect of McCarthyism the "lavender scare

The "lavender scare" was a moral panic about homosexual people in the United States government which led to their mass dismissal from government service during the mid-20th century. It contributed to and paralleled the anti-communist campaign wh ...

".

Homosexuality was classified as a psychiatric disorder in the 1950s.Gary Kinsman and Patrizia Gentile. ''The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation''. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2010, p. 65. However, in the context of the highly politicized Cold War environment, homosexuality became framed as a dangerous, contagious social disease that posed a potential threat to state security. As the family was believed to be the cornerstone of American strength and integrity, the description of homosexuals as "sexual perverts" meant that they were both unable to function within a family unit and presented the potential to poison the social body.Kinsman and Gentile, p. 8. This era also witnessed the establishment of widely spread FBI surveillance intended to identify homosexual government employees.

The McCarthy hearings and according "sexual pervert" investigations can be seen to have been driven by a desire to identify individuals whose ability to function as loyal citizens had been compromised. McCarthy began his campaign by drawing upon the ways in which he embodied traditional American values to become the self-appointed vanguard of social morality.

In the film industry, more than 300 actors, authors, and directors were denied work in the U.S. through the unofficial Hollywood blacklist. Blacklists were at work throughout the entertainment industry, in universities and schools at all levels, in the legal profession, and in many other fields. A port-security program initiated by the Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless of cargo or destination. As with other loyalty-security reviews of McCarthyism, the identities of any accusers and even the nature of any accusations were typically kept secret from the accused. Nearly 3,000 seamen and longshoremen lost their jobs due to this program alone.

Some of the notable people who were blacklisted or suffered some other persecution during McCarthyism include:

* Larry Adler, musician

* Nelson Algren, writer

* Lucille Ball, actress, model, and film studio executive.

*

In the film industry, more than 300 actors, authors, and directors were denied work in the U.S. through the unofficial Hollywood blacklist. Blacklists were at work throughout the entertainment industry, in universities and schools at all levels, in the legal profession, and in many other fields. A port-security program initiated by the Coast Guard shortly after the start of the Korean War required a review of every maritime worker who loaded or worked aboard any American ship, regardless of cargo or destination. As with other loyalty-security reviews of McCarthyism, the identities of any accusers and even the nature of any accusations were typically kept secret from the accused. Nearly 3,000 seamen and longshoremen lost their jobs due to this program alone.

Some of the notable people who were blacklisted or suffered some other persecution during McCarthyism include:

* Larry Adler, musician

* Nelson Algren, writer

* Lucille Ball, actress, model, and film studio executive.

* Alvah Bessie

Alvah Cecil Bessie (June 4, 1904 – July 21, 1985) was an American novelist, journalist and screenwriter who was blacklisted by the movie studios for being one of the Hollywood Ten who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities ...

, Abraham Lincoln Brigade, writer, journalist, screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

* Elmer Bernstein

Elmer Bernstein ( '; April 4, 1922August 18, 2004) was an American composer and conductor. In a career that spanned over five decades, he composed "some of the most recognizable and memorable themes in Hollywood history", including over 150 origi ...

, composer and conductor

* Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first America ...

, conductor, pianist, composer

* David Bohm, physicist and philosopher

* Bertolt Brecht

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956), known professionally as Bertolt Brecht, was a German theatre practitioner, playwright, and poet. Coming of age during the Weimar Republic, he had his first successes as a pl ...

, poet, playwright, screenwriter

* Archie Brown, Abraham Lincoln Brigade, veteran of World War II, union leader, imprisoned. Successfully challenged Landrum–Griffin Act

The Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act of 1959 (also "LMRDA" or the Landrum–Griffin Act), is a US labor law that regulates labor unions' internal affairs and their officials' relationships with employers.

Background

After enactment ...

provision

* Esther Brunauer

Esther Caukin Brunauer (July 7, 1901 – June 26, 1959) was a longtime employee of the American Association of University Women (AAUW) and then a U.S. government civil servant, who with her husband was targeted by Senator Joseph McCarthy's campa ...

, forced from the U.S. State Department

* Luis Buñuel, film director, producer

* Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

, actor and director

* Aaron Copland, composerOn the ''Red Channels'' blacklist of artists and entertainers: Schrecker (2002), p. 244.

* Bartley Crum, attorney

* Howard Da Silva

Howard Da Silva (born Howard Silverblatt, May 4, 1909 – February 16, 1986) was an American actor, director and musical performer on stage, film, television and radio. He was cast in dozens of productions on the New York stage, appeared in mo ...

, actor

* Jules Dassin, director

* Dolores del Río

María de los Dolores Asúnsolo y López Negrete (3 August 1904 – 11 April 1983), known professionally as Dolores del Río (), was a Mexican actress. With a career spanning more than 50 years, she is regarded as the first major female Latin Am ...

, actress

* Edward Dmytryk, director, Hollywood Ten

* W.E.B. Du Bois, civil rights activist and author

* George A. Eddy

George A. Eddy (June 15, 1907 – April 13, 1998) was an American economist who served in the Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury Department between 1934 and 1954. He was in Harry Dexter White's Division of Monetary Research. Between 1948 and 19 ...

, pre-Keynesian Harvard economist, US Treasury monetary policy specialist

* Albert Einstein, Nobel Prize-winning physicist, philosopher, mathematician, activist

* Hanns Eisler, composer

* Howard Fast, writer

* Lion Feuchtwanger, novelist and playwright

* Carl Foreman, writer of ''High Noon

''High Noon'' is a 1952 American Western film produced by Stanley Kramer from a screenplay by Carl Foreman, directed by Fred Zinnemann, and starring Gary Cooper. The plot, which occurs in real time, centers on a town marshal whose sense of ...

''

* John Garfield, actor

* C.H. Garrigues

image:BrickAtTable.jpg, up

Charles Harris Garrigues (1902–1974) was an American writer and journalist who wrote as C.H. Garrigues. He was a general-assignment reporter in History of Los Angeles#Civic corruption and police brutality, Los Angeles, ...

, journalist

* Jack Gilford

Jack Gilford (born Jacob Aaron Gellman; July 25, 1908 – June 4, 1990) was an American Broadway, film, and television actor. He was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for ''Save the Tiger'' (1973).

Early life

Gilfor ...

, actor

* Allen Ginsberg, Beat poet

* Ruth Gordon, actress

* Lee Grant, actress

* Dashiell Hammett, author

* Elizabeth Hawes, clothing designer, author, equal rights activist

* Lillian Hellman, playwright

* Dorothy Healey, union organizer, CPUSA official

* Lena Horne

Lena Mary Calhoun Horne (June 30, 1917 – May 9, 2010) was an American dancer, actress, singer, and civil rights activist. Horne's career spanned more than seventy years, appearing in film, television, and theatre. Horne joined the chorus of th ...

, singer

* Langston Hughes

James Mercer Langston Hughes (February 1, 1901 – May 22, 1967) was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist from Joplin, Missouri. One of the earliest innovators of the literary art form called jazz poetry, Hug ...

, writer, poet, playwright

* Marsha Hunt, actress

* Sam Jaffe

Shalom "Sam" Jaffe (March 10, 1891 – March 24, 1984) was an American actor, teacher, musician, and engineer. In 1951, he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his performance in ''The Asphalt Jungle'' (1950) and app ...

, actor

* Theodore Kaghan, diplomat"Theodore Kaghan, 77; Was in Foreign Service". ''The New York Times'', August 11, 1989. Accessed March 7, 2011. * Garson Kanin, writer and director *

Danny Kaye

Danny Kaye (born David Daniel Kaminsky; yi, דוד־דניאל קאַמינסקי; January 18, 1911 – March 3, 1987) was an American actor, comedian, singer and dancer. His performances featured physical comedy, idiosyncratic pantomimes, and ...

, comedian, singer

* Benjamin Keen

Benjamin Keen (1913–2002) was an American historian specialising in the history of colonial Latin America.

Keen received his PhD from Yale and taught at Amherst College, West Virginia University, and Jersey State College before joining Northe ...

, historian

* Otto Klemperer, conductor and composer

* Gypsy Rose Lee

Gypsy Rose Lee (born Rose Louise Hovick, January 8, 1911 – April 26, 1970) was an American burlesque entertainer, stripper and vedette famous for her striptease act. Also an actress, author, and playwright, her 1957 memoir was adapted into ...

, actress and stripper

A stripper or exotic dancer is a person whose occupation involves performing striptease in a public adult entertainment venue such as a strip club. At times, a stripper may be hired to perform at a bachelor party or other private event.

M ...

* Cornelius Lanczos, mathematician and physicist

* Ring Lardner Jr., screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

* Arthur Laurents, playwright

* Philip Loeb, actor

* Joseph Losey

Joseph Walton Losey III (; January 14, 1909 – June 22, 1984) was an American theatre and film director, producer, and screenwriter. Born in Wisconsin, he studied in Germany with Bertolt Brecht and then returned to the United States. Blackliste ...

, director

* Albert Maltz, screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

* Heinrich Mann, novelist

* Klaus Mann

Klaus Heinrich Thomas Mann (18 November 1906 – 21 May 1949) was a German writer and dissident. He was the son of Thomas Mann, a nephew of Heinrich Mann and brother of Erika Mann, with whom he maintained a lifelong close relationship, and Golo ...

, writer

* Thomas Mann, Nobel Prize winning novelist and essayist

* Thomas McGrath, poet

* Burgess Meredith, actor

* Arthur Miller, playwright and essayist

* Jessica Mitford

Jessica Lucy "Decca" Treuhaft (née Freeman-Mitford, later Romilly; 11 September 1917 – 23 July 1996) was an English author, one of the six aristocratic Mitford sisters noted for their sharply conflicting politics.

Jessica married her second ...

, author, muckraker

The muckrakers were reform-minded journalists, writers, and photographers in the Progressive Era in the United States (1890s–1920s) who claimed to expose corruption and wrongdoing in established institutions, often through sensationalist publ ...

. Refused to testify to HUAC.

* Dimitri Mitropoulos, conductor, pianist, composer

* Zero Mostel

Samuel Joel "Zero" Mostel (February 28, 1915 – September 8, 1977) was an American actor, comedian, and singer. He is best known for his portrayal of comic characters such as Tevye on stage in ''Fiddler on the Roof'', Pseudolus on stage and on ...

, actor

* Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, in ...

, biochemist, sinologist, historian of science

* J. Robert Oppenheimer, physicist, scientific director of the Manhattan Project

* Dorothy Parker, writer, humorist

* Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

, chemist, Nobel prizes for Chemistry and Peace

* Samuel Reber, diplomat

* Al Richmond, union organizer, editor

* Martin Ritt, actor and director

* Paul Robeson, actor, athlete, singer, writer, political activist

* Edward G. Robinson

Edward G. Robinson (born Emanuel Goldenberg; December 12, 1893January 26, 1973) was a Romanian-American actor of stage and screen, who was popular during the Hollywood's Golden Age. He appeared in 30 Broadway plays and more than 100 films duri ...

, actor

* Waldo Salt, screenwriter

* Jean Seberg, actress

* Pete Seeger, folk singer, songwriter

* Artie Shaw, jazz musician, bandleader, author

* Irwin Shaw, writer

* William L. Shirer, journalist, author

* Lionel Stander, actor

* Dirk Jan Struik, mathematician, historian of maths

* Paul Sweezy, economist and founder-editor of ''Monthly Review

The ''Monthly Review'', established in 1949, is an independent socialist magazine published monthly in New York City. The publication is the longest continuously published socialist magazine in the United States.

History Establishment

Following ...

''

* Charles W. Thayer

Charles W. Thayer (February 9, 1910 – August 27, 1969) was an American diplomat and author. He was an expert on Soviet-American relations and headed the Voice of America.

Early years

Charles Wheeler Thayer was born in Villanova, Pennsylvania ...

, diplomat

* Dalton Trumbo, screenwriter, Hollywood Ten

* Tsien Hsue-shen, physicist

* Sam Wanamaker, actor, director, responsible for recreating Shakespeare's Globe Theatre in London, England.

* Orson Welles, actor, author, film director

* Gene Weltfish, anthropologist fired from Columbia University

In 1953, Robert K. Murray, a young professor of history at Pennsylvania State University who had served as an intelligence officer in World War II, was revising his dissertation on the Red Scare of 1919–20 for publication until Little, Brown and Company decided that "under the circumstances ... it wasn't wise for them to bring this book out." He learned that investigators were questioning his colleagues and relatives. The University of Minnesota press published his volume, ''Red Scare: A Study in National Hysteria, 1919–1920'', in 1955.

Critical reactions