Mauryas on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Maurya Empire, or the Mauryan Empire, was a geographically extensive

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, Chandragupta led a series of campaigns in 305 BCE to take satrapies in the Indus Valley and northwest India. When Alexander's remaining forces were

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, Chandragupta led a series of campaigns in 305 BCE to take satrapies in the Indus Valley and northwest India. When Alexander's remaining forces were

Bindusara was born to Chandragupta, the founder of the Mauryan Empire. This is attested by several sources, including the various

Bindusara was born to Chandragupta, the founder of the Mauryan Empire. This is attested by several sources, including the various

As a young prince, Ashoka ( BCE) was a brilliant commander who crushed revolts in Ujjain and Takshashila. As monarch he was ambitious and aggressive, re-asserting the Empire's superiority in southern and western India. But it was his conquest of Kalinga (262–261 BCE) which proved to be the pivotal event of his life. Ashoka used Kalinga to project power over a large region by building a fortification there and securing it as a possession. Although Ashoka's army succeeded in overwhelming Kalinga forces of royal soldiers and civilian units, an estimated 100,000 soldiers and civilians were killed in the furious warfare, including over 10,000 of Ashoka's own men. Hundreds of thousands of people were adversely affected by the destruction and fallout of war. When he personally witnessed the devastation, Ashoka began feeling remorse. Although the annexation of Kalinga was completed, Ashoka embraced the teachings of Buddhism, and renounced war and violence. He sent out missionaries to travel around Asia and spread Buddhism to other countries.

Ashoka implemented principles of ''

As a young prince, Ashoka ( BCE) was a brilliant commander who crushed revolts in Ujjain and Takshashila. As monarch he was ambitious and aggressive, re-asserting the Empire's superiority in southern and western India. But it was his conquest of Kalinga (262–261 BCE) which proved to be the pivotal event of his life. Ashoka used Kalinga to project power over a large region by building a fortification there and securing it as a possession. Although Ashoka's army succeeded in overwhelming Kalinga forces of royal soldiers and civilian units, an estimated 100,000 soldiers and civilians were killed in the furious warfare, including over 10,000 of Ashoka's own men. Hundreds of thousands of people were adversely affected by the destruction and fallout of war. When he personally witnessed the devastation, Ashoka began feeling remorse. Although the annexation of Kalinga was completed, Ashoka embraced the teachings of Buddhism, and renounced war and violence. He sent out missionaries to travel around Asia and spread Buddhism to other countries.

Ashoka implemented principles of ''

The Empire was divided into four provinces, with the imperial capital at

The Empire was divided into four provinces, with the imperial capital at

For the first time in

For the first time in

According to a Jain text from 12th century, Chandragupta Maurya followed

According to a Jain text from 12th century, Chandragupta Maurya followed  The Buddhist texts ''

The Buddhist texts ''

The greatest monument of this period, executed in the reign of

The greatest monument of this period, executed in the reign of  During the Ashokan period, stonework was of a highly diversified order and comprised lofty free-standing pillars, railings of stupas, lion thrones and other colossal figures. The use of stone had reached such great perfection during this time that even small fragments of stone art were given a high lustrous polish resembling fine enamel. This period marked the beginning of

During the Ashokan period, stonework was of a highly diversified order and comprised lofty free-standing pillars, railings of stupas, lion thrones and other colossal figures. The use of stone had reached such great perfection during this time that even small fragments of stone art were given a high lustrous polish resembling fine enamel. This period marked the beginning of

The protection of animals in India was advocated by the time of the Maurya dynasty; being the first empire to provide a unified political entity in India, the attitude of the Mauryas towards forests, their denizens, and fauna in general is of interest.

The Mauryas firstly looked at forests as resources. For them, the most important forest product was the elephant. Military might in those times depended not only upon horses and men but also battle-elephants; these played a role in the defeat of

The protection of animals in India was advocated by the time of the Maurya dynasty; being the first empire to provide a unified political entity in India, the attitude of the Mauryas towards forests, their denizens, and fauna in general is of interest.

The Mauryas firstly looked at forests as resources. For them, the most important forest product was the elephant. Military might in those times depended not only upon horses and men but also battle-elephants; these played a role in the defeat of

Chandragupta and

Chandragupta and

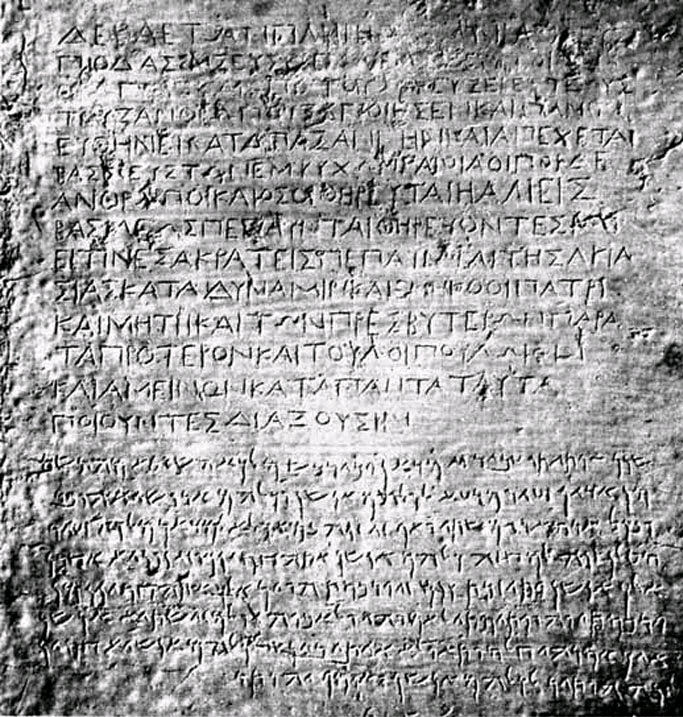

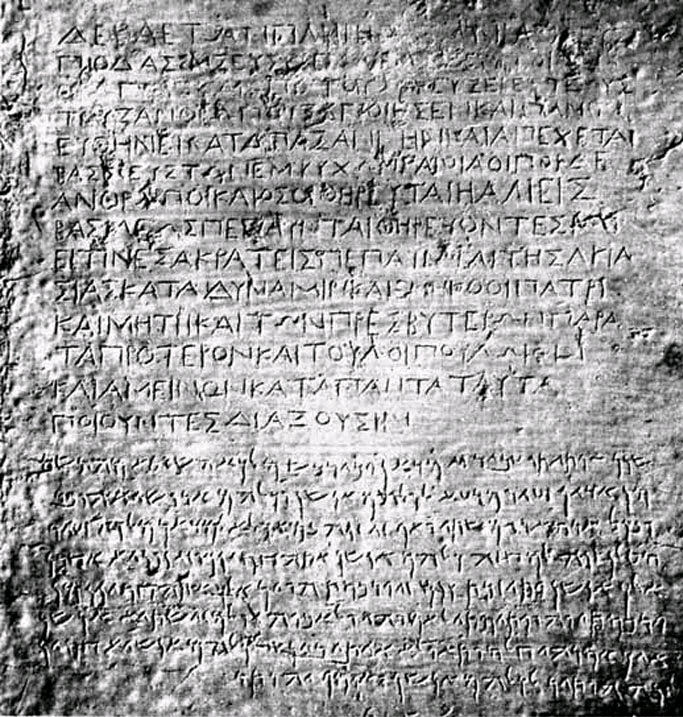

An influential and large Greek population was present in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Ashoka's rule, possibly remnants of Alexander's conquests in the Indus Valley region. In the Rock Edicts of Ashoka, some of them inscribed in Greek, Ashoka states that the Greeks within his dominion were converted to Buddhism:

Fragments of Edict 13 have been found in Greek, and a full Edict, written in both Greek and Aramaic, has been discovered in

An influential and large Greek population was present in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent under Ashoka's rule, possibly remnants of Alexander's conquests in the Indus Valley region. In the Rock Edicts of Ashoka, some of them inscribed in Greek, Ashoka states that the Greeks within his dominion were converted to Buddhism:

Fragments of Edict 13 have been found in Greek, and a full Edict, written in both Greek and Aramaic, has been discovered in

AiKhanoumAndIndia.jpg, The distribution of the

Also, in the

Livius.org: Maurya dynasty

{{DEFAULTSORT:Maurya Empire Ancient empires and kingdoms of India Ancient Hindu kingdoms Iron Age countries in Asia Iron Age cultures of South Asia Dynasties of Bengal Former empires Ancient history of Pakistan Ancient history of Afghanistan Jain empires and kingdoms Buddhist dynasties of India Magadha Kingdoms of Bihar Ruling Buddhist clans 4th century BC in India 3rd century BC in India 2nd century BC in India 320s BC establishments States and territories established in the 4th century BC States and territories disestablished in the 2nd century BC 4th-century BC establishments in India 2nd-century BC disestablishments Former monarchies of South Asia History of Nepal 4th-century BC establishments in Nepal 2nd-century BC disestablishments in Nepal

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

historical power in the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India ...

based in Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

, having been founded by Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an emp ...

in 322 BCE, and existing in loose-knit fashion until 185 BCE.

Quote: "Magadha power came to extend over the main cities and communication routes of the Ganges basin. Then, under Chandragupta Maurya (c.321–297 bce), and subsequently Ashoka his grandson, Pataliputra became the centre of the loose-knit Mauryan 'Empire' which during Ashoka's reign (c.268–232 bce) briefly had a presence throughout the main urban centres and arteries of the subcontinent, except for the extreme south." The Maurya Empire was centralized by the conquest of the Indo-Gangetic Plain

The Indo-Gangetic Plain, also known as the North Indian River Plain, is a fertile plain encompassing northern regions of the Indian subcontinent, including most of northern and eastern India, around half of Pakistan, virtually all of Bangla ...

, and its capital city was located at Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at ...

(modern Patna

Patna (

), historically known as Pataliputra, is the capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Patna had a population of 2.35 million, making it the 19th largest city in India. ...

). Outside this imperial center, the empire's geographical extent was dependent on the loyalty of military commanders who controlled the armed cities sprinkling it. During Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

's rule (ca. 268–232 BCE) the empire briefly controlled the major urban hubs and arteries of the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a physiographical region in Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian Ocean from the Himalayas. Geopolitically, it includes the countries of Bangladesh, Bhutan, India ...

excepting the deep south. It declined for about 50 years after Ashoka's rule, and dissolved in 185 BCE with the assassination of Brihadratha by Pushyamitra Shunga

Pushyamitra Shunga ( IAST: ) or Pushpamitra Shunga ( IAST: ) (ruled ) was the co-founder and the first or second ruler of the Shunga Empire which he and Gopāla established against the Maurya Empire. His original name was Puṣpaka or Puṣ ...

and foundation of the Shunga Empire

The Shunga Empire ( IAST: ') was an ancient Indian dynasty from Magadha that controlled areas of the most of the northern Indian subcontinent from around 185 to 73 BCE. The dynasty was established by Pushyamitra, after taking the throne of the ...

in Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

.

Chandragupta Maurya raised an army, with the assistance of Chanakya

Chanakya (Sanskrit: चाणक्य; IAST: ', ; 375–283 BCE) was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor. He is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya ...

, author of Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

, and overthrew the Nanda Empire in . Chandragupta rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India by conquering the satrap

A satrap () was a governor of the provinces of the ancient Median and Achaemenid Empires and in several of their successors, such as in the Sasanian Empire and the Hellenistic empires.

The satrap served as viceroy to the king, though with cons ...

s left by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, and by 317 BCE the empire had fully occupied northwestern India. The Mauryan Empire then defeated Seleucus I

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the po ...

, a diadochus and founder of the Seleucid Empire, during the Seleucid–Mauryan war, thus acquiring territory west of the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kash ...

.

Under the Mauryas, internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities thrived and expanded across South Asia due to the creation of a single and efficient system of finance, administration, and security. The Maurya dynasty built a precursor of the Grand Trunk Road

The Grand Trunk Road (formerly known as Uttarapath, Sarak-e-Azam, Shah Rah-e-Azam, Badshahi Sarak, and Long Walk) is one of Asia's oldest and longest major roads. For at least 2,500 years it has linked Central Asia to the Indian subcontinent ...

from Patliputra to Taxila. After the Kalinga War, the Empire experienced nearly half a century of centralized rule under Ashoka. Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

and sponsorship of Buddhist missionaries allowed for the expansion of that faith into Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, northwest India, and Central Asia.

The population of South Asia during the Mauryan period has been estimated to be between 15 and 30 million.

Quote: "Yet Sumit Guha considers that 20 million is an upper limit. This is because the demographic growth experienced in core areas is likely to have been less than that experienced in areas that were more lightly settled in the early historic period. The position taken here is that the population in Mauryan times (320–220 BCE) was between 15 and 30 million—although it may have been a little more, or it may have been a little less."

The empire's period of dominion was marked by exceptional creativity in art, architecture, inscriptions and produced texts,

but also by the consolidation of caste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultural ...

in the Gangetic plain, and the declining rights of women in the mainstream Indo-Aryan speaking regions of India.

Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware

The Northern Black Polished Ware culture (abbreviated NBPW or NBP) is an urban Iron Age Indian culture of the Indian Subcontinent, lasting c. 700–200 BCE (proto NBPW between 1200 and 700 BCE), succeeding the Painted Grey Ware culture and Bla ...

(NBPW). The ''Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

'' and the Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the expres ...

are the primary sources of written records of Mauryan times. The Lion Capital of Ashoka

The Lion Capital of Ashoka is the capital, or head, of a column erected by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in Sarnath, India, . Its crowning features are four life-sized lions set back to back on a drum-shaped abacus. The side of the abacus is a ...

at Sarnath

Sarnath (Hindustani pronunciation: aːɾnaːtʰ also referred to as Sarangnath, Isipatana, Rishipattana, Migadaya, or Mrigadava) is a place located northeast of Varanasi, near the confluence of the Ganges and the Varuna rivers in Uttar ...

is the national emblem

An emblem is an abstract or representational pictorial image that represents a concept, like a moral truth, or an allegory, or a person, like a king or saint.

Emblems vs. symbols

Although the words ''emblem'' and ''symbol'' are often used in ...

of the Republic of India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

.

Etymology

The name "Maurya" does not occur in Ashoka's inscriptions, or the contemporary Greek accounts such asMegasthenes

Megasthenes ( ; grc, Μεγασθένης, c. 350 BCE– c. 290 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian, diplomat and Indian ethnographer and explorer in the Hellenistic period. He described India in his book '' Indica'', which is now lost, but ...

's '' Indica'', but it is attested by the following sources:

*The Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman (c. 150 CE) prefixes "Maurya" to the names Chandragupta and Ashoka.

* The Puranas

Purana (; sa, , '; literally meaning "ancient, old"Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, , page 915) is a vast genre of Indian literature about a wide range of topics, particularly about legends an ...

(c. 4th century CE or earlier) use Maurya as a dynastic appellation.

* The Buddhist texts state that Chandragupta belonged to the " Moriya" clan of the Shakyas, the tribe to which Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in ...

belonged.

* The Jain texts state that Chandragupta was the son of a royal superintendent of peacocks (''mayura-poshaka'').

*Tamil Sangam literature

The Sangam literature (Tamil: சங்க இலக்கியம், ''caṅka ilakkiyam'';) historically known as 'the poetry of the noble ones' (Tamil: சான்றோர் செய்யுள், ''Cāṉṟōr ceyyuḷ'') connotes ...

also designate them as '' and mention them after the Nandas

* Kuntala inscription (from the town of Bandanikke, North Mysore ) of 12th century AD chronologically mention Mauryya as one of the dynasties which ruled the region.

According to some scholars, Kharavela' Hathigumpha inscription

The Hathigumpha Inscription is a seventeen line inscription in Prakrit language incised in Brahmi script in a cavern called Hathigumpha in Udayagiri hills, near Bhubaneswar in Odisha, India. Dated between 2nd-century BCE and 1st-century CE, it ...

(2nd-1st century BC) mentions era of Maurya Empire as Muriya Kala (Mauryan era), but this reading is disputed: other scholars—such as epigraphist D. C. Sircar—read the phrase as mukhiya-kala ("the principal art").

According to the Buddhist tradition, the ancestors of the Maurya kings had settled in a region where peacocks (''mora'' in Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist '' Pāli Canon'' or '' Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of '' Theravāda'' Bud ...

) were abundant. Therefore, they came to be known as "Moriyas", literally, "belonging to the place of peacocks". According to another Buddhist account, these ancestors built a city called Moriya-nagara ("Moriya-city"), which was so called, because it was built with the "bricks coloured like peacocks' necks".

The dynasty's connection to the peacocks, as mentioned in the Buddhist and Jain traditions, seems to be corroborated by archaeological evidence. For example, peacock figures are found on the Ashoka pillar at Nandangarh and several sculptures on the Great Stupa of Sanchi

Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometres from Raisen town, district headquarter and north-east of Bhop ...

. Based on this evidence, modern scholars theorize that the peacock may have been the dynasty's emblem.

Some later authors, such as Dhundiraja (a commentator on the ''Mudrarakshasa

The Mudrarakshasa (मुद्राराक्षस, IAST: ''Mudrārākṣasa'', ) is a Sanskrit-language play by Vishakhadatta that narrates the ascent of the king Chandragupta Maurya ( BCE) to power in India. The play is an example of ...

'') and an annotator of the ''Vishnu Purana

The Vishnu Purana ( IAST:, sa, विष्णुपुराण) is one of the eighteen Mahapuranas, a genre of ancient and medieval texts of Hinduism. It is an important Pancharatra text in the Vaishnavism literature corpus.

The manusc ...

'', state that the word "Maurya" is derived from Mura and the mother of the first Maurya king. However, the Puranas themselves make no mention of Mura and do not talk of any relation between the Nanda and the Maurya dynasties. Dhundiraja's derivation of the word seems to be his own invention: according to the Sanskrit rules, the derivative of the feminine name Mura ( IAST: Murā) would be "Maureya"; the term "Maurya" can only be derived from the masculine "Mura".

History

Founding

Prior to the Maurya Empire, the Nanda Empire ruled over most of the Indian subcontinent. The Nanda Empire was a large, militaristic, and economically powerful empire due to conquering theMahajanapadas

The Mahājanapadas ( sa, great realm, from ''maha'', "great", and '' janapada'' "foothold of a people") were sixteen kingdoms or oligarchic republics that existed in ancient India from the sixth to fourth centuries BCE during the second ur ...

. According to several legends, Chanakya travelled to Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at ...

, Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

, the capital of the Nanda Empire where Chanakya worked for the Nandas as a minister. However, Chanakya was insulted by the Emperor Dhana Nanda, of the Nanda dynasty and Chanakya swore revenge and vowed to destroy the Nanda Empire. He had to flee in order to save his life and went to Taxila, a notable center of learning, to work as a teacher. On one of his travels, Chanakya witnessed some young men playing a rural game practicing a pitched battle. He was impressed by the young Chandragupta and saw royal qualities in him as someone fit to rule.

Meanwhile, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

was leading his Indian campaigns and ventured into Punjab. His army mutinied at the Beas River

The Beas River ( Sanskrit: ; Hyphasis in Ancient Greek) is a river in north India. The river rises in the Himalayas in central Himachal Pradesh, India, and flows for some to the Sutlej River in the Indian state of Punjab. Its total lengt ...

and refused to advance farther eastward when confronted by another army. Alexander returned to Babylon and re-deployed most of his troops west of the Indus River

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kash ...

. Soon after Alexander died in Babylon in 323 BCE, his empire fragmented into independent kingdoms led by his generals.

The Maurya Empire was established in the Magadha region under the leadership of Chandragupta Maurya and his mentor Chanakya. Chandragupta was taken to Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area ...

by Chanakya and was tutored about statecraft and governing. Requiring an army Chandragupta recruited and annexed local military republics such as the Yaudheyas that had resisted Alexanders Empire. The Mauryan army quickly rose to become the prominent regional power in the North West of the Indian subcontinent. The Mauryan army then conquered the satraps established by the Macedonians. Ancient Greek historians Nearchus, Onesictrius, and Aristobolus have provided lot of information about the Mauryan empire. The Greek generals Eudemus and Peithon ruled in the Indus Valley until around 317 BCE, when Chandragupta Maurya (with the help of Chanakya, who was now his advisor) fought and drove out the Greek governors, and subsequently brought the Indus Valley under the control of his new seat of power in Magadha.

Chandragupta Maurya's ancestry is shrouded in mystery and controversy. On one hand, a number of ancient Indian accounts, such as the drama ''Mudrarakshasa

The Mudrarakshasa (मुद्राराक्षस, IAST: ''Mudrārākṣasa'', ) is a Sanskrit-language play by Vishakhadatta that narrates the ascent of the king Chandragupta Maurya ( BCE) to power in India. The play is an example of ...

'' (''Signet ring of Rakshasa'' – ''Rakshasa'' was the prime minister of Magadha) by Vishakhadatta

Vishakhadatta ( sa, विशाखदत्त) was an Indian Sanskrit poet and playwright. Although Vishakhadatta furnishes the names of his father and grandfather as ''Maharaja'' Bhaskaradatta and ''Maharaja'' Vateshvaradatta in his political ...

, describe his royal ancestry and even link him with the Nanda family. A kshatriya clan known as the Mauryas are referred to in the earliest Buddhist texts

Buddhist texts are those religious texts which belong to the Buddhism, Buddhist tradition. The earliest Buddhist texts were not committed to writing until some centuries after the death of Gautama Buddha. The oldest surviving Buddhist manu ...

, Mahaparinibbana Sutta. However, any conclusions are hard to make without further historical evidence. Chandragupta first emerges in Greek accounts as "Sandrokottos". As a young man he is said to have met Alexander. Chanakya is said to have met the Nanda king, angered him, and made a narrow escape.

Conquest of the Nanda Empire

Historically reliable details of Chandragupta's campaign against Nanda Empire are unavailable and legends written centuries later are inconsistent. Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu texts claimMagadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

was ruled by the Nanda dynasty, which, with Chanakya

Chanakya (Sanskrit: चाणक्य; IAST: ', ; 375–283 BCE) was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor. He is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya ...

's counsel, Chandragupta conquered Nanda Empire. The army of Chandragupta and Chanakya first conquered the Nanda outer territories, and finally besieged the Nanda capital Pataliputra. In contrast to the easy victory in Buddhist sources, the Hindu and Jain texts state that the campaign was bitterly fought because the Nanda dynasty had a powerful and well-trained army.

The Buddhist ''Mahavamsa Tika'' and Jain ''Parishishtaparvan'' records Chandragupta's army unsuccessfully attacking the Nanda capital. Chandragupta and Chanakya then began a campaign at the frontier of the Nanda empire, gradually conquering various territories on their way to the Nanda capital. He then refined his strategy by establishing garrisons in the conquered territories, and finally besieged the Nanda capital Pataliputra. There Dhana Nanda accepted defeat, The conquest was fictionalised in ''Mudrarakshasa'' play, it contains narratives not found in other versions of the Chanakya-Chandragupta legend. Because of this difference, Thomas Trautmann suggests that most of it is fictional or legendary, without any historical basis. Radha Kumud Mukherjee

Radha Kumud Mukherjee (also spelled Radhakumud or Radha Kumud Mookerji and also known as Radha Kumud Mukhopadhyaya; 25 January 1884 – 9 September 1963) was an Indian historian and a noted Indian nationalist during the period of British colon ...

similarly considers Mudrakshasa play without historical basis.

These legends state that the Nanda king was defeated, deposed and exiled by some accounts, while Buddhist accounts claim he was killed. With the defeat of Nanda, Chandragupta Maurya founded the Maurya Empire.

Chandragupta Maurya

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, Chandragupta led a series of campaigns in 305 BCE to take satrapies in the Indus Valley and northwest India. When Alexander's remaining forces were

After the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, Chandragupta led a series of campaigns in 305 BCE to take satrapies in the Indus Valley and northwest India. When Alexander's remaining forces were rout

A rout is a panicked, disorderly and undisciplined retreat of troops from a battlefield, following a collapse in a given unit's command authority, unit cohesion and combat morale (''esprit de corps'').

History

Historically, lightly-e ...

ed, returning westwards, Seleucus I Nicator fought to defend these territories. Not many details of the campaigns are known from ancient sources. Seleucus was defeated and retreated into the mountainous region of Afghanistan.

The two rulers concluded a peace treaty in 303 BCE, including a marital alliance. Under its terms, Chandragupta received the satrapies of Paropamisadae ( Kamboja and Gandhara) and Arachosia

Arachosia () is the Hellenized name of an ancient satrapy situated in the eastern parts of the Achaemenid empire. It was centred around the valley of the Arghandab River in modern-day southern Afghanistan, and extended as far east as the In ...

( Kandhahar) and Gedrosia

Gedrosia (; el, Γεδρωσία) is the Hellenized name of the part of coastal Balochistan that roughly corresponds to today's Makran. In books about Alexander the Great and his successors, the area referred to as Gedrosia runs from the Indu ...

(Balochistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastl ...

). Seleucus I received the 500 war elephant

A war elephant was an elephant that was trained and guided by humans for combat. The war elephant's main use was to charge the enemy, break their ranks and instill terror and fear. Elephantry is a term for specific military units using elepha ...

s that were to have a decisive role in his victory against western Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium i ...

kings at the Battle of Ipsus

The Battle of Ipsus ( grc, Ἱψός) was fought between some of the Diadochi (the successors of Alexander the Great) in 301 BC near the town of Ipsus in Phrygia. Antigonus I Monophthalmus, the Macedonian ruler of large parts of Asia, and his ...

in 301 BCE. Diplomatic relations were established and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes

Megasthenes ( ; grc, Μεγασθένης, c. 350 BCE– c. 290 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian, diplomat and Indian ethnographer and explorer in the Hellenistic period. He described India in his book '' Indica'', which is now lost, but ...

, Deimakos and Dionysius

The name Dionysius (; el, Διονύσιος ''Dionysios'', "of Dionysus"; la, Dionysius) was common in classical and post-classical times. Etymologically it is a nominalized adjective formed with a -ios suffix from the stem Dionys- of the name ...

resided at the Mauryan court.

Megasthenes in particular was a notable Greek ambassador in the court of Chandragupta Maurya. According to Arrian

Arrian of Nicomedia (; Greek: ''Arrianos''; la, Lucius Flavius Arrianus; )

was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander and philosopher of the Roman period.

'' The Anabasis of Alexander'' by Arrian is considered the best ...

, ambassador Megasthenes (c. 350 – c. 290 BCE) lived in Arachosia and travelled to Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at ...

. Megasthenes' description of Mauryan society as freedom-loving gave Seleucus a means to avoid invasion, however, underlying Seleucus' decision was the improbability of success. In later years, Seleucus' successors maintained diplomatic relations with the Empire based on similar accounts from returning travellers.

Chandragupta established a strong centralised state with an administration at Pataliputra, which, according to Megasthenes, was "surrounded by a wooden wall pierced by 64 gates and 570 towers". Aelian, although not expressly quoting Megasthenes nor mentioning Pataliputra, described Indian palaces as superior in splendor to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

's Susa

Susa ( ; Middle elx, 𒀸𒋗𒊺𒂗, translit=Šušen; Middle and Neo- elx, 𒋢𒋢𒌦, translit=Šušun; Neo-Elamite and Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼𒀭, translit=Šušán; Achaemenid elx, 𒀸𒋗𒐼, translit=Šušá; fa, شوش ...

or Ecbatana

Ecbatana ( peo, 𐏃𐎥𐎶𐎫𐎠𐎴 ''Hagmatāna'' or ''Haŋmatāna'', literally "the place of gathering" according to Darius I's inscription at Bisotun; Persian: هگمتانه; Middle Persian: 𐭠𐭧𐭬𐭲𐭠𐭭; Parthian: 𐭀� ...

. The architecture of the city seems to have had many similarities with Persian cities of the period.

Chandragupta's son Bindusara

Bindusara (), also Amitraghāta or Amitrakhāda (Sanskrit: अमित्रघात, "slayer of enemies" or "devourer of enemies") or Amitrochates (Greek: Ἀμιτροχάτης) (Strabo calls him Allitrochades (Ἀλλιτροχάδης)) ...

extended the rule of the Mauryan empire towards southern India. The famous Tamil poet Mamulanar of the Sangam literature

The Sangam literature ( Tamil: சங்க இலக்கியம், ''caṅka ilakkiyam'';) historically known as 'the poetry of the noble ones' ( Tamil: சான்றோர் செய்யுள், ''Cāṉṟōr ceyyuḷ'') connote ...

described how areas south of the Deccan Plateau

The large Deccan Plateau in southern India is located between the Western Ghats and the Eastern Ghats, and is loosely defined as the peninsular region between these ranges that is south of the Narmada river. To the north, it is bounded by t ...

which comprised Tamil country was invaded by the Maurya army using troops from Karnataka. Mamulanar states that Vadugar (people who resided in Andhra-Karnataka regions immediately to the north of Tamil Nadu) formed the vanguard of the Mauryan army. He also had a Greek ambassador at his court, named Deimachus. According to Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ...

, Chandragupta Maurya subdued all of India, and Justin also observed that Chandragupta Maurya was "in possession of India". These accounts are corroborated by Tamil sangam literature which mentions about Mauryan invasion with their south Indian allies and defeat of their rivals at Podiyil hill in Tirunelveli district in present-day Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil languag ...

.

Chandragupta renounced his throne and followed Jain teacher Bhadrabahu. He is said to have lived as an ascetic at Shravanabelagola

Shravanabelagola () is a town located near Channarayapatna of Hassan district in the Indian state of Karnataka and is from Bengaluru. The Gommateshwara Bahubali statue at Shravanabelagola is one of the most important tirthas (pilgrimage des ...

for several years before fasting to death, as per the Jain practice of '' sallekhana''.

Bindusara

Bindusara was born to Chandragupta, the founder of the Mauryan Empire. This is attested by several sources, including the various

Bindusara was born to Chandragupta, the founder of the Mauryan Empire. This is attested by several sources, including the various Puranas

Purana (; sa, , '; literally meaning "ancient, old"Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, , page 915) is a vast genre of Indian literature about a wide range of topics, particularly about legends an ...

and the '' Mahavamsa''. He is attested by the Buddhist texts such as '' Dipavamsa'' and '' Mahavamsa'' ("Bindusaro"); the Jain texts such as ''Parishishta-Parvan''; as well as the Hindu texts such as ''Vishnu Purana

The Vishnu Purana ( IAST:, sa, विष्णुपुराण) is one of the eighteen Mahapuranas, a genre of ancient and medieval texts of Hinduism. It is an important Pancharatra text in the Vaishnavism literature corpus.

The manusc ...

'' ("Vindusara"). According to the 12th century Jain writer Hemachandra

Hemachandra was a 12th century () Indian Jain saint, scholar, poet, mathematician, philosopher, yogi, grammarian, law theorist, historian, lexicographer, rhetorician, logician, and prosodist. Noted as a prodigy by his contemporaries, he gai ...

's '' Parishishta-Parvan'', the name of Bindusara's mother was Durdhara. Some Greek sources also mention him by the name "Amitrochates" or its variations.

Historian Upinder Singh estimates that Bindusara ascended the throne around 297 BCE. Bindusara, just 22 years old, inherited a large empire that consisted of what is now, Northern, Central and Eastern parts of India along with parts of Afghanistan and Baluchistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. ...

. Bindusara extended this empire to the southern part of India, as far as what is now known as Karnataka

Karnataka (; ISO: , , also known as Karunāḍu) is a state in the southwestern region of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act. Originally known as Mysore State , it was renamed ''Kar ...

. He brought sixteen states under the Mauryan Empire and thus conquered almost all of the Indian peninsula (he is said to have conquered the 'land between the two seas' – the peninsular region between the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean, bounded on the west and northwest by India, on the north by Bangladesh, and on the east by Myanmar and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India. Its southern limit is a line bet ...

and the Arabian Sea

The Arabian Sea ( ar, اَلْبَحرْ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Bahr al-ˁArabī) is a region of the northern Indian Ocean bounded on the north by Pakistan, Iran and the Gulf of Oman, on the west by the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel ...

). Bindusara did not conquer the friendly Tamil kingdoms of the Cholas, ruled by King Ilamcetcenni, the Pandyas, and Cheras. Apart from these southern states, Kalinga (modern Odisha) was the only kingdom in India that did not form part of Bindusara's empire. It was later conquered by his son Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

, who served as the viceroy of Ujjaini

Ujjain (, Hindustani pronunciation: �d͡ːʒɛːn is a city in Ujjain district of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It is the fifth-largest city in Madhya Pradesh by population and is the administrative centre of Ujjain district and Uj ...

during his father's reign, which highlights the importance of the town.

Bindusara's life has not been documented as well as that of his father Chandragupta or of his son Ashoka. Chanakya continued to serve as prime minister during his reign. According to the medieval Tibetan scholar Taranatha who visited India, Chanakya helped Bindusara "to destroy the nobles and kings of the sixteen kingdoms and thus to become absolute master of the territory between the eastern and western oceans". During his rule, the citizens of Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area ...

revolted twice. The reason for the first revolt was the maladministration of Susima

Susima (also Sushima) was the Crown prince of the Maurya Empire of ancient India and the eldest son and heir-apparent of the second Mauryan emperor Bindusara. He was next in line for his father's throne, but was killed by his younger half-bro ...

, his eldest son. The reason for the second revolt is unknown, but Bindusara could not suppress it in his lifetime. It was crushed by Ashoka after Bindusara's death.

Bindusara maintained friendly diplomatic relations with the Hellenic world. Deimachus was the ambassador of Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the M ...

emperor Antiochus I at Bindusara's court. Diodorus states that the king of Palibothra (Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at ...

, the Mauryan capital) welcomed a Greek author, Iambulus. This king is usually identified as Bindusara. Pliny states that the Egyptian king Philadelphus

''Philadelphus'' () (mock-orange) is a genus of about 60 species of shrubs from 3–20 ft (1–6 m) tall, native to North America, Central America, Asia and (locally) in southeast Europe.

They are named "mock-orange" in reference to their ...

sent an envoy named Dionysius

The name Dionysius (; el, Διονύσιος ''Dionysios'', "of Dionysus"; la, Dionysius) was common in classical and post-classical times. Etymologically it is a nominalized adjective formed with a -ios suffix from the stem Dionys- of the name ...

to India. According to Sailendra Nath Sen, this appears to have happened during Bindusara's reign.

Unlike his father Chandragupta (who at a later stage converted to Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

), Bindusara believed in the Ajivika sect. Bindusara's guru Pingalavatsa (Janasana) was a Brahmin of the Ajivika sect. Bindusara's wife, Queen Subhadrangi

The information about Mother of Ashoka The Great (c. 3rd century BCE), the 3rd Mauryan emperor of ancient India, varies between different sources. Ashoka's own inscriptions and the main texts that provide information about his life (such as ''As ...

(Queen Dharma/ Aggamahesi) was a Brahmin also of the Ajivika sect from Champa (present Bhagalpur district). Bindusara is credited with giving several grants to Brahmin monasteries (''Brahmana-bhatto'').

Historical evidence suggests that Bindusara died in the 270s BCE. According to Upinder Singh, Bindusara died around 273 BCE. Alain Daniélou believes that he died around 274 BCE. Sailendra Nath Sen believes that he died around 273–272 BCE, and that his death was followed by a four-year struggle of succession, after which his son Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

became the emperor in 269–268 BCE. According to the '' Mahavamsa'', Bindusara reigned for 28 years. The ''Vayu Purana

The ''Vayu Purana'' ( sa, वायुपुराण, ) is a Sanskrit text and one of the eighteen major Puranas of Hinduism.

''Vayu Purana'' is mentioned in the manuscripts of the Mahabharata and other Hindu texts, which has led scholars to pr ...

'', which names Chandragupta's successor as "Bhadrasara", states that he ruled for 25 years.

Ashoka

ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India � ...

'' by banning hunting and violent sports activity and ending indentured and forced labor (many thousands of people in war-ravaged Kalinga had been forced into hard labour and servitude). While he maintained a large and powerful army, to keep the peace and maintain authority, Ashoka expanded friendly relations with states across Asia and Europe, and he sponsored Buddhist missions. He undertook a massive public works building campaign across the country. Over 40 years of peace, harmony and prosperity made Ashoka one of the most successful and famous monarchs in Indian history. He remains an idealized figure of inspiration in modern India.

The Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of more than thirty inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Maurya Empire who reigned from 268 BCE to 232 BCE. Ashoka used the expres ...

, set in stone, are found throughout the Subcontinent. Ranging from as far west as Afghanistan and as far south as Andhra ( Nellore District), Ashoka's edicts state his policies and accomplishments. Although predominantly written in Prakrit, two of them were written in Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, and one in both Greek and Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

. Ashoka's edicts refer to the Greeks, Kambojas

Kamboja ( sa, कम्बोज) was a kingdom of Iron Age India that spanned parts of South and Central Asia, frequently mentioned in Sanskrit and Pali literature. Eponymous with the kingdom name, the Kambojas were an Indo-Iranian peopl ...

, and Gandhara

Gandhāra is the name of an ancient region located in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, more precisely in present-day north-west Pakistan and parts of south-east Afghanistan. The region centered around the Peshawar Val ...

s as peoples forming a frontier region of his empire. They also attest to Ashoka's having sent envoys to the Greek rulers in the West as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts precisely name each of the rulers of the Hellenic world at the time such as ''Amtiyoko'' (Antiochus

Antiochus is a Greek male first name, which was a dynastic name for rulers of the Seleucid Empire and the Kingdom of Commagene.

In Jewish historical memory, connected with the Maccabean Revolt and the holiday of Hanukkah, "Antiochus" refers spec ...

), ''Tulamaya'' (Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

), ''Amtikini'' ( Antigonos), ''Maka'' ( Magas) and ''Alikasudaro'' (Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

) as recipients of Ashoka's proselytism. The Edicts also accurately locate their territory "600 yojanas away" (a yojanas being about 7 miles), corresponding to the distance between the center of India and Greece (roughly 4,000 miles).

Decline

Ashoka was followed for 50 years by a succession of weaker kings. He was succeeded by Dasharatha Maurya, who was Ashoka's grandson. None of Ashoka's sons could ascend to the throne after him. Mahinda, his firstborn, became a Buddhist monk. Kunala Maurya was blind and hence couldn't ascend to the throne; and Tivala, son of Kaurwaki, died even earlier than Ashoka. Little is known about another son, Jalauka. The empire lost many territories under Dasharatha, which were later reconquered by Samprati, Kunala's son. Post Samprati, the Mauryas slowly lost many territories. In 180 BCE, Brihadratha Maurya, was killed by his generalPushyamitra Shunga

Pushyamitra Shunga ( IAST: ) or Pushpamitra Shunga ( IAST: ) (ruled ) was the co-founder and the first or second ruler of the Shunga Empire which he and Gopāla established against the Maurya Empire. His original name was Puṣpaka or Puṣ ...

in a military parade without any heir. Hence, the great Maurya empire finally ended, giving rise to the Shunga Empire

The Shunga Empire ( IAST: ') was an ancient Indian dynasty from Magadha that controlled areas of the most of the northern Indian subcontinent from around 185 to 73 BCE. The dynasty was established by Pushyamitra, after taking the throne of the ...

.

Reasons advanced for the decline include the succession of weak kings after Aśoka Maurya, the partition of the empire into two, the growing independence of some areas within the empire, such as that ruled by Sophagasenus, a top-heavy administration where authority was entirely in the hands of a few persons, an absence of any national consciousness, the pure scale of the empire making it unwieldy, and invasion by the Greco-Bactrian Empire.

Some historians, such as H. C. Raychaudhuri, have argued that Ashoka's pacifism undermined the "military backbone" of the Maurya empire. Others, such as Romila Thapar

Romila Thapar (born 30 November 1931) is an Indian historian. Her principal area of study is ancient India, a field in which she is pre-eminent. Quotr: "The pre-eminent interpreter of ancient Indian history today. ... " Thapar is a Professor ...

, have suggested that the extent and impact of his pacifism have been "grossly exaggerated".

Shunga coup (185 BCE)

Buddhist records such as theAshokavadana

The Ashokavadana ( sa, अशोकावदान; ; "Narrative of Ashoka") is an Indian Sanskrit-language text that describes the birth and reign of the Third Mauryan Emperor Ashoka. It contains legends as well as historical narratives, and ...

write that the assassination of Brihadratha and the rise of the Shunga empire led to a wave of religious persecution for Buddhists

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and g ...

, and a resurgence of Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Indian religion or ''dharma'', a religious and universal order or way of life by which followers abide. As a religion, it is the world's third-largest, with over 1.2–1.35 billion followers, or 15–16% of the global po ...

. According to Sir John Marshall

Sir John Hubert Marshall (19 March 1876, Chester, England – 17 August 1958, Guildford, England) was an English archaeologist who was Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India from 1902 to 1928. He oversaw the excavations of Ha ...

, Pushyamitra may have been the main author of the persecutions, although later Shunga kings seem to have been more supportive of Buddhism. Other historians, such as Etienne Lamotte and Romila Thapar

Romila Thapar (born 30 November 1931) is an Indian historian. Her principal area of study is ancient India, a field in which she is pre-eminent. Quotr: "The pre-eminent interpreter of ancient Indian history today. ... " Thapar is a Professor ...

, among others, have argued that archaeological evidence in favour of the allegations of persecution of Buddhists are lacking, and that the extent and magnitude of the atrocities have been exaggerated.

Establishment of the Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BCE)

The fall of the Mauryas left theKhyber Pass

The Khyber Pass (خیبر درہ) is a mountain pass in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, on the border with the Nangarhar Province of Afghanistan. It connects the town of Landi Kotal to the Valley of Peshawar at Jamrud by traversi ...

unguarded, and a wave of foreign invasion followed. The Greco-Bactrian

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the Ind ...

king, Demetrius

Demetrius is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning “Demetris” - "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, Dimitri, Dimitrie, Dimitar, Du ...

, capitalized on the break-up, and he conquered southern Afghanistan and parts of northwestern India around 180 BCE, forming the Indo-Greek Kingdom

The Indo-Greek Kingdom, or Graeco-Indian Kingdom, also known historically as the Yavana Kingdom (Yavanarajya), was a Hellenistic-era Greek kingdom covering various parts of Afghanistan and the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinen ...

. The Indo-Greeks would maintain holdings on the trans-Indus region, and make forays into central India, for about a century. Under them, Buddhism flourished, and one of their kings, Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His re ...

, became a famous figure of Buddhism; he was to establish a new capital of Sagala, the modern city of Sialkot

Sialkot ( ur, ) is a city located in Punjab, Pakistan. It is the capital of Sialkot District and the 13th most populous city in Pakistan. The boundaries of Sialkot are joined with Jammu (the winter capital of Indian administered Jammu and Kas ...

. However, the extent of their domains and the lengths of their rule are subject to much debate. Numismatic evidence indicates that they retained holdings in the subcontinent right up to the birth of Christ. Although the extent of their successes against indigenous powers such as the Shungas, Satavahana

The Satavahanas (''Sādavāhana'' or ''Sātavāhana'', IAST: ), also referred to as the Andhras in the Puranas, were an ancient Indian dynasty based in the Deccan region. Most modern scholars believe that the Satavahana rule began in the la ...

s, and Kalingas are unclear, what is clear is that Scythian tribes, renamed Indo-Scythians

Indo-Scythians (also called Indo-Sakas) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples of Scythian origin who migrated from Central Asia southward into modern day Pakistan and Northwestern India from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 4th c ...

, brought about the demise of the Indo-Greeks from around 70 BCE and retained lands in the trans-Indus, the region of Mathura

Mathura () is a city and the administrative headquarters of Mathura district in the states and union territories of India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is located approximately north of Agra, and south-east of Delhi; about from the to ...

, and Gujarat.

Military

Megasthenes mentions military command consisting of six boards of five members each, (i)Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It include ...

(ii) military transport (iii) Infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and m ...

(iv) Cavalry with Catapults (v) Chariot divisions and (vi) Elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae ...

s.

Administration

The Empire was divided into four provinces, with the imperial capital at

The Empire was divided into four provinces, with the imperial capital at Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at ...

. From Ashokan edicts, the names of the four provincial capitals are Tosali (in the east), Ujjain

Ujjain (, Hindustani pronunciation: �d͡ːʒɛːn is a city in Ujjain district of the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. It is the fifth-largest city in Madhya Pradesh by population and is the administrative centre of Ujjain district and Ujjain ...

(in the west), Suvarnagiri (in the south), and Taxila

Taxila or Takshashila (; sa, तक्षशिला; pi, ; , ; , ) is a city in Punjab, Pakistan. Located in the Taxila Tehsil of Rawalpindi District, it lies approximately northwest of the Islamabad–Rawalpindi metropolitan area ...

(in the north). The head of the provincial administration was the ''Kumara'' (royal prince), who governed the provinces as king's representative. The ''kumara'' was assisted by Mahamatyas and council of ministers. This organizational structure was reflected at the imperial level with the Emperor and his ''Mantriparishad'' (Council of Ministers).. The mauryans established a well developed coin minting system. Coins were mostly made of silver and copper. Certain gold coins were in circulation as well. The coins were widely used for trade and commerce

Historians theorise that the organisation of the Empire was in line with the extensive bureaucracy described by Chanakya

Chanakya (Sanskrit: चाणक्य; IAST: ', ; 375–283 BCE) was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor. He is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya ...

in the Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

: a sophisticated civil service governed everything from municipal hygiene to international trade. The expansion and defense of the empire was made possible by what appears to have been one of the largest armies in the world during the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

. According to Megasthenes, the empire wielded a military of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, 8,000 chariots and 9,000 war elephants besides followers and attendants. A vast espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

system collected intelligence for both internal and external security purposes. Having renounced offensive warfare and expansionism, Ashoka nevertheless continued to maintain this large army, to protect the Empire and instil stability and peace across West and South Asia..Even though large parts were under the control of Mauryan empire the spread of information and imperial message was limited since many parts were inaccessible and were situated far away from capital of empire.

The economy of the empire has been described as, "a socialized monarchy", "a sort of state socialism", and the world's first welfare state. Under the Mauryan system there was no private ownership of land as all land was owned by the king to whom tribute was paid by the by the laboring class. In return the emperor supplied the laborers with agricultural products, animals, seeds, tools, public infrastructure, and stored food in reserve for times of crisis.

Local government

Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

and Megasthenes

Megasthenes ( ; grc, Μεγασθένης, c. 350 BCE– c. 290 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian, diplomat and Indian ethnographer and explorer in the Hellenistic period. He described India in his book '' Indica'', which is now lost, but ...

accounts of Pataliputra

Pataliputra ( IAST: ), adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE as a small fort () near the Ganges river.. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at ...

describe the intricate municipal system formed by Maurya empire to govern its cities. A city counsel made up of thirty commissioners was divided into six committees or boards which governed the city. The first board fixed wages and looked after provided goods, second board made arrangement for foreign dignitaries, tourists and businessmen, third board made records and registrations, fourth looked after manufactured goods and sale of commodities, fifth board regulated trade, issued licenses and checked weights and measurements, sixth board collected sales taxes. Some cities such as Taxila had autonomy to issue their own coins. The city counsel had officers who looked after public welfare such as maintenance of roads, public buildings, markets, hospitals, educational institutions etc. The official head of the village was Gramika (in towns Nagarika). The city counsel also had some magisterial powers.

Economy

For the first time in

For the first time in South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;; ...

, political unity and military security allowed for a common economic system and enhanced trade and commerce, with increased agricultural productivity. The previous situation involving hundreds of kingdoms, many small armies, powerful regional chieftains, and internecine warfare, gave way to a disciplined central authority. Farmers were freed of tax and crop collection burdens from regional kings, paying instead to a nationally administered and strict-but-fair system of taxation as advised by the principles in the ''Arthashastra''. Chandragupta Maurya established a single currency across India, and a network of regional governors and administrators and a civil service provided justice and security for merchants, farmers and traders. The Mauryan army wiped out many gangs of bandits, regional private armies, and powerful chieftains who sought to impose their own supremacy in small areas. Although regimental in revenue collection, Maurya also sponsored many public works and waterways to enhance productivity, while internal trade in India expanded greatly due to new-found political unity and internal peace.

Under the Indo-Greek friendship treaty, and during Ashoka's reign, an international network of trade expanded. The Khyber Pass

The Khyber Pass (خیبر درہ) is a mountain pass in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan, on the border with the Nangarhar Province of Afghanistan. It connects the town of Landi Kotal to the Valley of Peshawar at Jamrud by traversi ...

, on the modern boundary of Pakistan and Afghanistan, became a strategically important port of trade and intercourse with the outside world. Greek states and Hellenic kingdoms in West Asia became important trade partners of India. Trade also extended through the Malay peninsula

The Malay Peninsula ( Malay: ''Semenanjung Tanah Melayu'') is a peninsula in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The are ...

into Southeast Asia. India's exports included silk goods and textiles, spices and exotic foods. The external world came across new scientific knowledge and technology with expanding trade with the Mauryan Empire. Ashoka also sponsored the construction of thousands of roads, waterways, canals, hospitals, rest-houses and other public works. The easing of many over-rigorous administrative practices, including those regarding taxation and crop collection, helped increase productivity and economic activity across the Empire.

In many ways, the economic situation in the Mauryan Empire is analogous to the Roman Empire of several centuries later. Both had extensive trade connections and both had organizations similar to corporation

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and ...

s. While Rome had organizational entities which were largely used for public state-driven projects, Mauryan India had numerous private commercial entities. These existed purely for private commerce and developed before the Mauryan Empire itself.

Religion

Throughout the period of empire,Brahmanism

The historical Vedic religion (also known as Vedicism, Vedism or ancient Hinduism and subsequently Brahmanism (also spelled as Brahminism)), constituted the religious ideas and practices among some Indo-Aryan peoples of northwest Indian Subco ...

was an important religion. The Mauryans favored Brahmanism as well as Jainism and Buddhism. Minor religious sects such as Ajivikas also received patronage. A number of Hindu texts

Hindu texts are manuscripts and voluminous historical literature which are related to any of the diverse traditions within Hinduism. A few of these texts are shared across these traditions and they are broadly considered Hindu scriptures. These ...

were written during the Mauryan period.

According to a Jain text from 12th century, Chandragupta Maurya followed

According to a Jain text from 12th century, Chandragupta Maurya followed Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

after retiring, when he renounced his throne and material possessions to join a wandering group of Jain monks and in his last days, he observed the rigorous but self-purifying Jain ritual of santhara (fast unto death), at Shravana Belgola in Karnataka

Karnataka (; ISO: , , also known as Karunāḍu) is a state in the southwestern region of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act. Originally known as Mysore State , it was renamed ''Kar ...

. Samprati, the grandson of Ashoka

Ashoka (, ; also ''Asoka''; 304 – 232 BCE), popularly known as Ashoka the Great, was the third emperor of the Maurya Empire of Indian subcontinent during to 232 BCE. His empire covered a large part of the Indian subcontinent, ...

, also patronized Jainism. Samprati was influenced by the teachings of Jain monks like Suhastin and he is said to have built 125,000 derasars across India. Some of them are still found in the towns of Ahmedabad, Viramgam, Ujjain, and Palitana. It is also said that just like Ashoka, Samprati sent messengers and preachers to Greece, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkme ...

and the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Province), East Thrace (Europ ...

for the spread of Jainism, but, to date, no evidence has been found to support this claim.

The Buddhist texts ''

The Buddhist texts ''Samantapasadika

Samantapāsādikā refers to a collection of Pali commentaries on the Theravada Tipitaka Vinaya. It was a translation of Sinhala commentaries into Pali by Buddhaghosa

Buddhaghosa was a 5th-century Indian Theravada Buddhist commentator, transl ...

'' and '' Mahavamsa'' suggest that Bindusara followed Hindu Brahmanism, calling him a "''Brahmana bhatto''" ("monk of the Brahmanas").

Magadha

Magadha was a region and one of the sixteen sa, script=Latn, Mahajanapadas, label=none, lit=Great Kingdoms of the Second Urbanization (600–200 BCE) in what is now south Bihar (before expansion) at the eastern Ganges Plain. Magadha was ruled ...

, the centre of the empire, was also the birthplace of Buddhism. Ashoka initially practised Brahmanism but later followed Buddhism; following the Kalinga War, he renounced expansionism and aggression, and the harsher injunctions of the ''Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...

'' on the use of force, intensive policing, and ruthless measures for tax collection and against rebels. Ashoka sent a mission led by his son Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta to Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, whose king Tissa was so charmed with Buddhist ideals that he adopted them himself and made Buddhism the state religion. Ashoka sent many Buddhist missions to West Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes A ...

, Greece and South East Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, and commissioned the construction of monasteries and schools, as well as the publication of Buddhist literature across the empire. He is believed to have built as many as 84,000 stupas across India, such as Sanchi

Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometres from Raisen town, district headquarter and north-east of Bhop ...

and Mahabodhi Temple

The Mahabodhi Temple (literally: "Great Awakening Temple") or the Mahābodhi Mahāvihāra, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is an ancient, but rebuilt and restored Buddhist temple in Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India, marking the location where the Buddha i ...

, and he increased the popularity of Buddhism in Afghanistan and Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

. Ashoka helped convene the Third Buddhist Council

The Third Buddhist council was convened in about 250 BCE at Asokarama in Pataliputra, under the patronage of Emperor Ashoka.

The traditional reason for convening the Third Buddhist Council is reported to have been to rid the Sangha of corrupti ...

of India's and South Asia's Buddhist orders near his capital, a council that undertook much work of reform and expansion of the Buddhist religion. Indian merchants embraced Buddhism and played a large role in spreading the religion across the Mauryan Empire.

Society

The population of South Asia during the Mauryan period has been estimated to be between 15 and 30 million. Quote: "Yet Sumit Guha considers that 20 million is an upper limit. This is because the demographic growth experienced in core areas is likely to have been less than that experienced in areas that were more lightly settled in the early historic period. The position taken here is that the population in Mauryan times (320–220 bce) was between 15 and 30 million—although it may have been a little more, or it may have been a little less." According to Tim Dyson, the period of the Mauryan Empire saw the consolidation ofcaste

Caste is a form of social stratification characterised by endogamy, hereditary transmission of a style of life which often includes an occupation, ritual status in a hierarchy, and customary social interaction and exclusion based on cultural ...

among the Indo-Aryan people who had settled in the Gangetic plain, increasingly meeting tribal people who were incorporated into their evolving caste-system, and the declining rights of women in the Indo-Aryan speaking regions of India, though "these developments did not affect people living in large parts of the subcontinent."

Architectural remains

Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an emp ...

, was the old palace at Paliputra, modern Kumhrar in Patna

Patna (

), historically known as Pataliputra, is the capital and largest city of the state of Bihar in India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Patna had a population of 2.35 million, making it the 19th largest city in India. ...

. Excavations have unearthed the remains of the palace, which is thought to have been a group of several buildings, the most important of which was an immense pillared hall supported on a high substratum of timbers. The pillars were set in regular rows, thus dividing the hall into a number of smaller square bays. The number of columns is 80, each about meters high. According to the eyewitness account of Megasthenes

Megasthenes ( ; grc, Μεγασθένης, c. 350 BCE– c. 290 BCE) was an ancient Greek historian, diplomat and Indian ethnographer and explorer in the Hellenistic period. He described India in his book '' Indica'', which is now lost, but ...

, the palace was chiefly constructed of timber, and was considered to exceed in splendour and magnificence the palaces of Susa and Ecbatana, its gilded pillars being adorned with golden vines and silver birds. The buildings stood in an extensive park studded with fish ponds and furnished with a great variety of ornamental trees and shrubs. Kauṭilya's Arthashastra

The ''Arthashastra'' ( sa, अर्थशास्त्रम्, ) is an Ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, political science, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is ...