martyrs on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'',

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'',

In

In  The concept of Jesus as a martyr has recently received greater attention. Analyses of the Gospel passion narratives have led many scholars to conclude that they are martyrdom accounts in terms of genre and style. Several scholars have also concluded that

The concept of Jesus as a martyr has recently received greater attention. Analyses of the Gospel passion narratives have led many scholars to conclude that they are martyrdom accounts in terms of genre and style. Several scholars have also concluded that  In Christianity, death in

In Christianity, death in

''Shahid'' originates from the

''Shahid'' originates from the

Martyrdom (called ''shahadat'' in Punjabi) is a fundamental concept in

Martyrdom (called ''shahadat'' in Punjabi) is a fundamental concept in

* 399 BCE –

* 399 BCE –

"Martyrs"

''Catholic Encyclopedia'' * Foster, Claude R. Jr. (1995). ''Paul Schneider, the Buchenwald apostle: a Christian martyr in Nazi Germany: A Sourcebook on the German Church Struggle''. Westchester, PA: SSI Bookstore, West Chester University. * History.com Editors. "Abolitionist John Brown Is Hanged". History.com, 4 Mar. 2010, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/john-brown-hanged.

– 16th century classic book, accounts of martyrdoms

''Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion''. {{Authority control Religious terminology Jungian archetypes

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'',

A martyr (, ''mártys'', "witness", or , ''marturia'', stem

Stem or STEM may refer to:

Plant structures

* Plant stem, a plant's aboveground axis, made of vascular tissue, off which leaves and flowers hang

* Stipe (botany), a stalk to support some other structure

* Stipe (mycology), the stem of a mushro ...

, ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In the martyrdom narrative of the remembering community, this refusal to comply with the presented demands results in the punishment or execution of an actor by an alleged oppressor. Accordingly, the status of the 'martyr' can be considered a posthumous title

A posthumous name is an honorary name given mostly to the notable dead in East Asian culture. It is predominantly practiced in East Asian countries such as China, Korea, Vietnam, Japan, and Thailand. Reflecting on the person's accomplishments or ...

as a reward for those who are considered worthy of the concept of martyrdom by the living, regardless of any attempts by the deceased to control how they will be remembered in advance. Insofar, the martyr is a relational figure of a society's boundary work that is produced by collective memory. Originally applied only to those who suffered for their religious beliefs, the term has come to be used in connection with people killed for a political cause.

Most martyrs are considered holy or are respected by their followers, becoming symbols of exceptional leadership and heroism in the face of difficult circumstances. Martyrs play significant roles in religions. Similarly, martyrs have had notable effects in secular life, including such figures as Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

, among other political and cultural examples.

Meaning

In its original meaning, the word martyr, meaning ''witness

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

'', was used in the secular sphere as well as in the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

of the Bible

The Bible (from Koine Greek , , 'the books') is a collection of religious texts or scriptures that are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, and many other religions. The Bible is an anthologya compilation of texts of a ...

. The process of bearing witness was not intended to lead to the death of the witness, although it is known from ancient writers (e.g. Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for ''The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

) and from the New Testament that witnesses often died for their testimonies.

During the early Christian

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Jewish d ...

centuries, the term acquired the extended meaning of believers who are called to witness for their religious belief, and on account of this witness, endure suffering or death. The term, in this later sense, entered the English language

English is a West Germanic language of the Indo-European language family, with its earliest forms spoken by the inhabitants of early medieval England. It is named after the Angles, one of the ancient Germanic peoples that migrated to the is ...

as a loanword

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because th ...

. The death of a martyr or the value attributed to it is called ''martyrdom''.

The early Christians who first began to use the term ''martyr'' in its new sense saw Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

as the first and greatest martyr, on account of his crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the victim is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross or beam and left to hang until eventual death from exhaustion and asphyxiation. It was used as a punishment by the Persians, Carthagin ...

. The early Christians appear to have seen Jesus as the archetypal

The concept of an archetype (; ) appears in areas relating to behavior, historical psychology, and literary analysis.

An archetype can be any of the following:

# a statement, pattern of behavior, prototype, "first" form, or a main model that ...

martyr.A. J. Wallace and R. D. Rusk, ''Moral Transformation: The Original Christian Paradigm of Salvation'' (New Zealand: Bridgehead, 2011), pp. 217–229.

The word ''martyr'' is used in English to describe a wide variety of people. However, the following table presents a general outline of common features present in stereotypical martyrdoms.

Christianity

In

In Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, a martyr, in accordance with the meaning of the original Greek ''martys'' in the New Testament, is one who brings a testimony, usually written or verbal. In particular, the testimony is that of the Christian Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words an ...

, or more generally, the Word of God. A Christian witness is a biblical witness whether or not death follows.

The concept of Jesus as a martyr has recently received greater attention. Analyses of the Gospel passion narratives have led many scholars to conclude that they are martyrdom accounts in terms of genre and style. Several scholars have also concluded that

The concept of Jesus as a martyr has recently received greater attention. Analyses of the Gospel passion narratives have led many scholars to conclude that they are martyrdom accounts in terms of genre and style. Several scholars have also concluded that Paul the Apostle

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

understood Jesus' death as a martyrdom. In light of such conclusions, some have argued that the Christians of the first few centuries would have interpreted the crucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and consid ...

as a martyrdom.

In the context of church history, from the time of the persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire

The persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire occurred, sporadically and usually locally, throughout the Roman Empire, beginning in the 1st century CE and ending in the 4th century CE. Originally a polytheistic empire in the traditions of Ro ...

, and Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68), was the fifth Roman emperor and final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 un ...

it developed that a martyr was one who was killed for maintaining a religious

Religion is usually defined as a social system, social-cultural system of designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morality, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sacred site, sanctified places, prophecy, prophecie ...

belief, ''knowing'' that this will almost certainly result in imminent death (though without intentionally seeking death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

). This definition of ''martyr'' is not specifically restricted to the Christian faith. Though Christianity recognizes certain Old Testament Jewish figures, like Abel

Abel ''Hábel''; ar, هابيل, Hābīl is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He was the younger brother of Cain, and the younger son of Adam and Eve, the first couple in Biblical history. He was a shepher ...

and the Maccabees

The Maccabees (), also spelled Machabees ( he, מַכַּבִּים, or , ; la, Machabaei or ; grc, Μακκαβαῖοι, ), were a group of Jewish rebel warriors who took control of Judea, which at the time was part of the Seleucid Empire. ...

, as holy, and the New Testament mentions the imprisonment and beheading of John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

, Jesus's possible cousin and his prophet and forerunner, the first Christian witness, after the establishment of the Christian faith (at Pentecost), to be killed for his testimony was Saint Stephen

Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ''Stéphanos'', meaning "wreath, crown" and by extension "reward, honor, renown, fame", often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 AD) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first ...

(whose name means "crown"), and those who suffer martyrdom are said to have been "crowned". From the time of Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

, Christianity was decriminalized, and then, under Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

, became the state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

, which greatly diminished persecution (although not for non-Nicene Christians). As some wondered how then they could most closely follow Christ there was a development of ''desert spirituality'', desert monks, self-mortification, ascetics, (Paul the Hermit

Paul of Thebes (; , ''Paûlos ho Thēbaîos''; ; c. 227 – c. 341), commonly known as Paul the First Hermit or Paul the Anchorite, was an Egyptian saint regarded as the first Christian hermit, who was claimed to have lived alone in the deser ...

, St. Anthony), following Christ by separation from the world. This was a kind of ''white martyrdom'', dying to oneself every day, as opposed to a ''red martyrdom'', the giving of one's life in a violent death.

sectarian

Sectarianism is a political or cultural conflict between two groups which are often related to the form of government which they live under. Prejudice, discrimination, or hatred can arise in these conflicts, depending on the political status quo ...

persecution can be viewed as martyrdom. There were martyrs recognized on both sides of the schism between the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of England after 1534. Two hundred and eighty-eight Christians were martyred for their faith by public burning between 1553 and 1558 by the Roman Catholic Queen Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, and as "Bloody Mary" by her Protestant opponents, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain from January 1556 until her death in 1558. Sh ...

in England leading to the reversion to the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

under Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

in 1559. "From hundreds to thousands" of Waldensians

The Waldensians (also known as Waldenses (), Vallenses, Valdesi or Vaudois) are adherents of a church tradition that began as an ascetic movement within Western Christianity before the Reformation.

Originally known as the "Poor Men of Lyon" in ...

were martyred in the Massacre of Mérindol

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

in 1545. Three hundred Roman Catholics were said to be martyred by the Church authorities in England in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Even more modern day accounts of martyrdom for Christ exist, depicted in books such as ''Jesus Freaks

''Jesus freak'' is a term arising from the late 1960s and early 1970s counterculture and is frequently used as a pejorative for those involved in the Jesus movement. As Tom Wolfe illustrates in ''The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test'', the term "fre ...

,'' though the numbers are disputed. There are claims that the numbers of Christians killed for their faith annually are greatly exaggerated, but the fact of ongoing Christian martyrdoms remains undisputed.

Baháʼí Faith

In theBaháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the Baháʼí Faith and the unity of religion, essential worth of all religions and Baháʼí Faith and the unity of humanity, the unity of all people. Established by ...

, martyrs are those who sacrifice their lives serving humanity in the name of God. However, Bahá'u'lláh, the founder of the Baháʼí Faith, discouraged the literal meaning of sacrificing one's life. Instead, he explained that martyrdom is devoting oneself to service to humanity.

Chinese culture

Martyrdom was extensively promoted by theTongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China (or T'ung-meng Hui, variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, ) was a secret society and underground resistance movement ...

and the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

party in modern China. Revolutionaries who died fighting against the Qing dynasty in the Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

and throughout the Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

period, furthering the cause of the revolution, were recognized as martyrs.

Hinduism

Despite the promotion of ''ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India � ...

'' (non-violence) within Sanatana Dharma, and there being no concept of martyrdom, there is the belief of righteous duty (''dharma

Dharma (; sa, धर्म, dharma, ; pi, dhamma, italic=yes) is a key concept with multiple meanings in Indian religions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism and others. Although there is no direct single-word translation for '' ...

''), where violence is used as a last resort to resolution after all other means have failed. Examples of this are found in the Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the ''Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kuruk ...

. Upon completion of their exile, the Pandavas were refused the return of their portion of the kingdom by their cousin Duruyodhana; and following which all means of peace talks by Krishna

Krishna (; sa, कृष्ण ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the eighth avatar of Vishnu and also as the Supreme god in his own right. He is the god of protection, compassion, tenderness, and love; and is one ...

, Vidura

Vidura (Sanskrit: विदुर, lit. ''skilled'', ''intelligent'' or ''wise''), also known as Kshatri, plays a key role in the Hindu epic ''Mahabharata''. He is described as the prime minister of the Kuru kingdom and is the paternal uncle o ...

and Sanjaya

Sanjaya or Sanjay (Sanskrit: सञ्जय, meaning "victory") or Sanjaya Gavalgana is an advisor from the ancient Indian Hindu war epic ''Mahābhārata''.

In ''Mahabharata''—An ancient story of a war between the Pandavas and the Kauravas ...

failed. During the great war which commenced, even Arjuna

Arjuna (Sanskrit: अर्जुन, ), also known as Partha and Dhananjaya, is a character in several ancient Hindu texts, and specifically one of the major characters of the Indian epic Mahabharata. In the epic, he is the third among Panda ...

was brought down with doubts, e.g., attachment, sorrow, fear. This is where Krishna instructs Arjuna

Arjuna (Sanskrit: अर्जुन, ), also known as Partha and Dhananjaya, is a character in several ancient Hindu texts, and specifically one of the major characters of the Indian epic Mahabharata. In the epic, he is the third among Panda ...

how to carry out his duty as a righteous warrior

A warrior is a person specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracies, class, or caste.

History

Warriors seem to have been p ...

and fight.

Islam

''Shahid'' originates from the

''Shahid'' originates from the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

ic Arabic word meaning "witness" and is also used to denote a martyr. ''Shahid'' occurs frequently in the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

in the generic sense "witness", but only once in the sense "martyr, one who dies for his faith"; this latter sense acquires wider use in the hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

s. Islam views a martyr as a man or woman who dies while conducting ''jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

'', whether on or off the battlefield (see greater jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with Go ...

and lesser jihad).

The concept of the martyr in Islam had been made prominent during the Islamic revolution (1978/79) in Iran and the subsequent Iran-Iraq war, so that the cult of the martyr had a lasting impact on the course of revolution and war.

Judaism

Martyrdom inJudaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

is one of the main examples of ''Kiddush Hashem

''Kiddush HaShem'' ( he, קידוש השם "sanctification of the Name") is a precept of Judaism. In Rabbinic sources and modern parlance, it refers to private and communal conduct which reflect well, instead of poorly, on the Jewish people.

Or ...

'', meaning "sanctification of God's name" through public dedication to Jewish practice. Religious martyrdom is considered one of the more significant contributions of Hellenistic Judaism

Hellenistic Judaism was a form of Judaism in classical antiquity that combined Jewish religious tradition with elements of Greek culture. Until the early Muslim conquests of the eastern Mediterranean, the main centers of Hellenistic Judaism were A ...

to Western Civilization

Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions">human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise ''De architectura''.

image:Plato Pio-Cle ...

. 1 Maccabees

The First Book of Maccabees, also known as First Maccabees (written in shorthand as 1 Maccabees or 1 Macc.), is a book written in Hebrew by an anonymousRappaport, U., ''47. 1 Maccabees'' in Barton, J. and Muddiman, J. (2001)The Oxford Bible Comme ...

and 2 Maccabees recount numerous martyrdoms suffered by Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

resisting Hellenizing (adoption of Greek ideas or customs of a Hellenistic civilization

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in History of the Mediterranean region, Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as sig ...

) by their Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

overlords, being executed for such crimes as observing the Sabbath, circumcising their boys or refusing to eat pork or meat sacrificed to foreign gods. According to W. H. C. Frend

William Hugh Clifford Frend (11 January 1916 – 1 August 2005) was an English ecclesiastical historian, archaeologist, and Anglican priest.

Academic career

* Haileybury College (scholar)

* Keble College, Oxford (scholar, BA first class in mo ...

, "Judaism was itself a religion of martyrdom" and it was this "Jewish psychology of martyrdom" that inspired Christian martyrdom. However, the notion of martyrdom in the two traditions differ considerably.

Sikhism

Martyrdom (called ''shahadat'' in Punjabi) is a fundamental concept in

Martyrdom (called ''shahadat'' in Punjabi) is a fundamental concept in Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit=Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fro ...

and represents an important institution of the faith. Sikhs believe in ''Ibaadat se Shahadat'' (from love to martyrdom). Some famous Sikh martyrs include:

* Guru Arjan

Guru Arjan (Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰੂ ਅਰਜਨ, pronunciation: ; 15 April 1563 – 30 May 1606) was the first of the two Gurus martyred in the Sikh faith and the fifth of the ten total Sikh Gurus. He compiled the first official edition of th ...

, the fifth leader of Sikhism. Guru ji was brutally tortured for almost 5 days before he attained shaheedi, or martyrdom.

* Guru Tegh Bahadur

Guru Tegh Bahadur ( Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਤੇਗ਼ ਬਹਾਦਰ (Gurmukhi); ; 1 April 1621 – 11 November 1675) was the ninth of ten Gurus who founded the Sikh religion and the leader of Sikhs from 1665 until his beheading in 1675 ...

, the ninth guru of Sikhism, martyred on 11 November 1675. He is also known as ''Dharam Di Chadar'' (i.e. "the shield of Religion"), suggesting that to save Hinduism, the guru gave his life.

* Bhai Dayala

Bhai Dayala Ji ( pa, ਭਾਈ ਦਿਆਲਾ ਜੀ, hi, भाई दयाला जी) died 9 November 1675, also known as ''Bhai Dayal Das'' He was boiled alongside his Sikh companions Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Sati Das and the Ninth Guru, ...

is one of the Sikhs who was martyred at Chandni Chowk at Delhi in November 1675 due to his refusal to accept Islam.

* Bhai Mati Das

Bhai Mati Das ( Punjabi: ਭਾਈ ਮਤੀ ਦਾਸ; died 1675) along with his younger brother Bhai Sati Das were martyrs of early Sikh history. Bhai Mati Das, Bhai Dayala, and Bhai Sati Das were executed at a ''kotwali'' (police-station) in ...

is considered by some one of the greatest martyrs in Sikh history, martyred at Chandni Chowk at Delhi in November 1675 to save Hindu Brahmins.

* Bhai Sati Das

Bhai Sati Das ( Punjabi: ਭਾਈ ਸਤੀ ਦਾਸ; died 1675) along with his elder brother Bhai Mati Das were martyrs of early Sikh history. Bhai Sati Das, Bhai Mati Das and Bhai Dyal Das were all executed at ''kotwali'' (police-station) ...

is also considered by some one of the greatest martyrs in Sikh history, martyred along with Guru Teg Bahadur at Chandni Chowk at Delhi in November 1675 to save kashmiri pandits.

* Sahibzada Ajit Singh

Ajit Singh (Gurmukhi: ਅਜੀਤ ਸਿੰਘ; 11 February 1687 –23 December 1704), also referred to with honorifics as Sahibzada Ajit Singh or Baba Ajit Singh, was the eldest son of Guru Gobind Singh and the son of Mata Sundari. His younger ...

, Sahibzada Jujhar Singh

Jujhar Singh (Gurmukhi: ਸਾਹਿਬਜ਼ਾਦਾ ਜੁਝਾਰ ਸਿੰਘ; 9 April 1691 – 22 December 1704), the second son of Gobind Singh, was born to Mata Jito at Anandpur Sahib. This event is now celebrated on April 9 each y ...

, Sahibzada Zorawar Singh

Zorawar Singh (17 November 1696 – 5 or 6 December 1705, pa, ਸਾਹਿਬਜ਼ਾਦਾ ਜ਼ੋਰਾਵਰ ਸਿੰਘ), alternatively spelt as Jorawar Singh, was a son of Guru Gobind Singh who was executed in the court of Wazir Khan, t ...

and Sahibzada Fateh Singh

Sahib or Saheb (; ) is an Arabic title meaning 'companion'. It was historically used for the first caliph Abu Bakr in the Quran. The title is still applied to the caliph by Sunni Muslims.

As a loanword, ''Sahib'' has passed into several langua ...

– the four sons of Guru Gobind Singh, the 10th Sikh guru.

* Bhai Mani Singh

Bhai Mani Singh was an 18th-century Sikh scholar and martyr. He was a childhood companion of Guru Gobind Singh and took the vows of Sikhism when the Guru inaugurated the Khalsa in March 1699. Soon after that, the Guru sent him to Amritsar t ...

, who came from a family of over 20 different martyrs

Notable martyrs

* 399 BCE –

* 399 BCE – Socrates

Socrates (; ; –399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy and among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no te ...

, a Greek philosopher who chose death rather than renounce his ideals.

* c. 34 CE – Saint Stephen

Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ''Stéphanos'', meaning "wreath, crown" and by extension "reward, honor, renown, fame", often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 AD) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first ...

, considered to be the first Christian martyr.

* c. 2nd century CE – Ten Martyrs

The Ten Martyrs ( he, עֲשֶׂרֶת הָרוּגֵי מַלְכוּת ''ʿAsereṯ hāRūgēi Malḵūṯ'', "The Ten Royal Martyrs") were ten rabbis living during the era of the Mishnah who were martyred by the Roman Empire in the period after ...

of Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

.

* c. 288 – Saint Sebastian

Saint Sebastian (in Latin: ''Sebastianus''; Narbo, Gallia Narbonensis, Roman Empire c. AD 255 – Rome, Italia, Roman Empire c. AD 288) was an early Christian saint and martyr. According to traditional belief, he was killed during the Dioclet ...

, the subject of many works of art.

* c. 304 – Saint Agnes of Rome, beheaded for refusing to forsake her devotion to Christ, for Roman paganism.

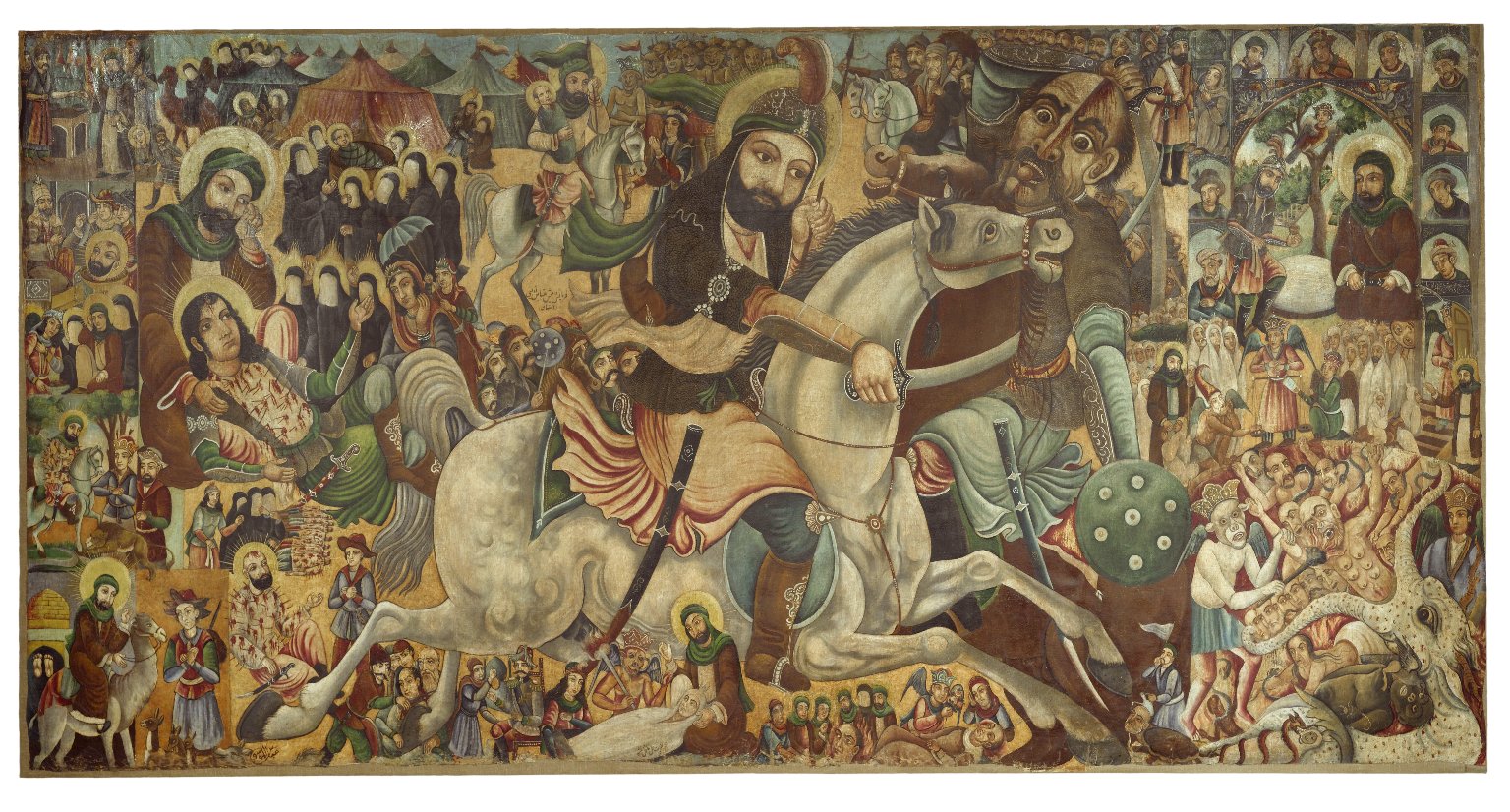

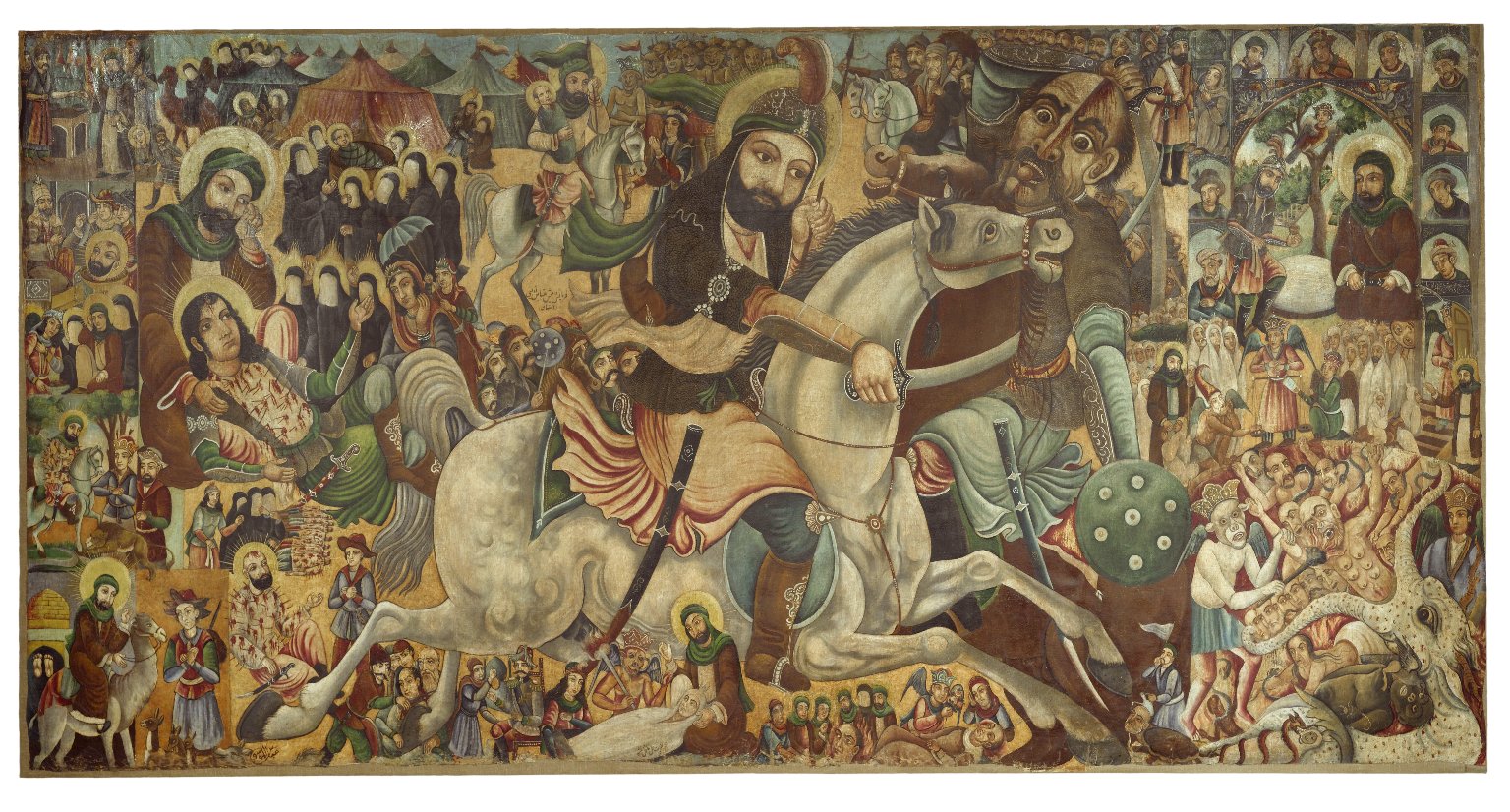

* c. 680 – Husayn ibn Ali

Abū ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib ( ar, أبو عبد الله الحسين بن علي بن أبي طالب; 10 January 626 – 10 October 680) was a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a son of Ali ibn Abi ...

, grandson of Muhammed

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

beheaded for opposing the Umayyad caliphate.

* 1415 – Jan Hus

Jan Hus (; ; 1370 – 6 July 1415), sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as ''Iohannes Hus'' or ''Johannes Huss'', was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the inspir ...

, Christian reformer burned at the stake for heresy

* 1535 – Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord ...

, beheaded for refusing to acknowledge Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

as Supreme Head of the Church of England.

* 1606 – Guru Arjan Dev

Guru Arjan (Gurmukhi: ਗੁਰੂ ਅਰਜਨ, pronunciation: ; 15 April 1563 – 30 May 1606) was the first of the two Gurus martyred in the Sikh faith and the fifth of the ten total Sikh Gurus. He compiled the first official edition of t ...

, the fifth leader of Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit=Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fro ...

.

* 1675 – Guru Tegh Bahadur

Guru Tegh Bahadur ( Punjabi: ਗੁਰੂ ਤੇਗ਼ ਬਹਾਦਰ (Gurmukhi); ; 1 April 1621 – 11 November 1675) was the ninth of ten Gurus who founded the Sikh religion and the leader of Sikhs from 1665 until his beheading in 1675 ...

, the ninth Guru of Sikhism

Sikhism (), also known as Sikhi ( pa, ਸਿੱਖੀ ', , from pa, ਸਿੱਖ, lit=disciple', 'seeker', or 'learner, translit=Sikh, label=none),''Sikhism'' (commonly known as ''Sikhī'') originated from the word ''Sikh'', which comes fro ...

, referred to as "Hind di Chadar" or "Shield of India" martyred in defense of religious freedom of Hindus.

* 1844 – Joseph Smith, Jr.

Joseph Smith Jr. (December 23, 1805June 27, 1844) was an American religious leader and founder of Mormonism and the Latter Day Saint movement. When he was 24, Smith published the Book of Mormon. By the time of his death, 14 years later, he ...

, founder of Mormonism

Mormonism is the religious tradition and theology of the Latter Day Saint movement of Restorationist Christianity started by Joseph Smith in Western New York in the 1820s and 1830s. As a label, Mormonism has been applied to various aspects of t ...

, killed by a mob in Carthage Jail

Carthage Jail is a historic building in Carthage, Illinois, listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP). It was built in 1839 and is best known as the location of the 1844 killing of Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saint mov ...

, Illinois.

* 1941 – Maximilian Kolbe

Maximilian Maria Kolbe (born Raymund Kolbe; pl, Maksymilian Maria Kolbe; 1894–1941) was a Polish Catholic priest and Conventual Franciscan friar who volunteered to die in place of a man named Franciszek Gajowniczek in the German death camp ...

, OFM, a Roman Catholic priest, who was martyred in the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

, August 1941.

Political martyrs

A political martyr is someone who suffers persecution or death for advocating, renouncing, refusing to renounce, or refusing to advocate a political belief or cause. Notable political martyrs include: *1793 –Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (; born Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the ''sans-culottes'', a radical ...

, a French Jacobin

, logo = JacobinVignette03.jpg

, logo_size = 180px

, logo_caption = Seal of the Jacobin Club (1792–1794)

, motto = "Live free or die"(french: Vivre libre ou mourir)

, successor = Pa ...

assassinated by Charlotte Corday

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont (27 July 1768 – 17 July 1793), known as Charlotte Corday (), was a figure of the French Revolution. In 1793, she was executed by guillotine for the assassination of Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat, who w ...

.

*1793 – Charlotte Corday

Marie-Anne Charlotte de Corday d'Armont (27 July 1768 – 17 July 1793), known as Charlotte Corday (), was a figure of the French Revolution. In 1793, she was executed by guillotine for the assassination of Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat, who w ...

, a Girondin

The Girondins ( , ), or Girondists, were members of a loosely knit political faction during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnard ...

sympathizer executed during the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

for assassinating Jean-Paul Marat

Jean-Paul Marat (; born Mara; 24 May 1743 – 13 July 1793) was a French political theorist, physician, and scientist. A journalist and politician during the French Revolution, he was a vigorous defender of the ''sans-culottes'', a radical ...

.

*1835 - King Hintsa kaKhawuta, a Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

monarch who was shot and killed while attempting to escape captivity during Sixth Frontier War

The Xhosa Wars (also known as the Cape Frontier Wars or the Kaffir Wars) were a series of nine wars (from 1779 to 1879) between the Xhosa Kingdom and the British Empire as well as Trekboers in what is now the Eastern Cape in South Africa. Th ...

, also known as the Hintsa War.

*1859 - John Brown John Brown most often refers to:

*John Brown (abolitionist) (1800–1859), American who led an anti-slavery raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in 1859

John Brown or Johnny Brown may also refer to:

Academia

* John Brown (educator) (1763–1842), Ir ...

, a militant abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

who was executed

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

after his raid on Harper’s Ferry. Many abolitionists of the time extolled him as a martyr.

*1865 – Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, the 16th U.S. President

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

. Assassinated by a Confederate sympathizer after the end of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

.

*1919 – Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg (; ; pl, Róża Luksemburg or ; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary socialist, Marxist philosopher and anti-war activist. Successively, she was a member of the Proletariat party, ...

, a German Marxist revolutionary summarily executed along with Karl Liebknecht

Karl Paul August Friedrich Liebknecht (; 13 August 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a German socialist and anti-militarist. A member of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) beginning in 1900, he was one of its deputies in the Reichstag from ...

for their roles in the Spartacist uprising

The Spartacist uprising (German: ), also known as the January uprising (), was a general strike and the accompanying armed struggles that took place in Berlin from 5 to 12 January 1919. It occurred in connection with the November Revolutio ...

.

*1920 - Yusuf al-Azma

Yusuf al-Azma ( ar, يوسف العظمة, ALA-LC: ''Yūsuf al-ʻAẓmah''; 1883 – 24 July 1920) was the Syrian minister of war in the governments of prime ministers Rida al-Rikabi and Hashim al-Atassi, and the Arab Army's chief of general st ...

, Syrian army commander whose refusal to surrender to the French, his insistence on entering battle with inferior forces and his death commanding the Syrians in Maysalun made him a hero in Syria and the Arab world

*1929 – Nurkhon Yuldashkhojayeva

Nurkhon Yuldashkhojayeva ( uz, Nurxon Yoʻldoshxoʻjayeva, often anglicized as ''Nurkhon Yuldasheva'') was one of the first Uzbek women to dance onstage without a paranja Paranja, veil. She was born in 1913 in Margilan, a city in Fergana Province ...

, an Uzbek dancer murdered in an honor killing

An honor killing (American English), honour killing (Commonwealth English), or shame killing is the murder of an individual, either an outsider or a member of a family, by someone seeking to protect what they see as the dignity and honor of t ...

for dancing without veil; depicted as a martyr of Hujum

Hujum ( rus, Худжум, Khudzhum, xʊd͡ʐʐʊm; in Turkic languages, ''storming'' or ''assault'', from ar, هجوم) was a series of policies and actions taken by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, initiated by Joseph Stalin, to remove ...

in the play "Nurkhon" by Kamil Yashin after her death.

*1930 – Horst Wessel

Horst Ludwig Georg Erich Wessel (9 October 1907 – 23 February 1930) was a Berlin ''Sturmführer'' ("Assault Leader", the lowest commissioned officer rank) of the ''Sturmabteilung'' (SA), the Nazi Party's stormtroopers. After his killing in 1 ...

killed by Albrecht Höhler

Albrecht "Ali" Höhler (April 30, 1898 – September 20, 1933) was a German communist. He was a member of the Red Front Fighters Association (''Roter Frontkämpferbund'' or RFB), the street-fighters of the Communist Party of Germany. He is know ...

(a Communist Party member). Became Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

martyr, due to promotion by Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

.

*1943 – Hans and Sophie Scholl, killed during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

for distributing leaflets opposing Nazism.

*1948 – Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, an Indian nationalist

Indian nationalism is an instance of territorial nationalism, which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, b ...

leader referred as the 'Father of the Nation' by Indians, assassinated by Hindu fanatic Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He was a Hindu nationalist from Maharashtra who shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith prayer meeting in B ...

for trying to spread communal harmony.

*1956 – Imre Nagy

Imre Nagy (; 7 June 1896 – 16 June 1958) was a Hungarian communist politician who served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers (''de facto'' Prime Minister) of the Hungarian People's Republic from 1953 to 1955. In 1956 Nagy became leader ...

, a Hungarian communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

. Executed for his leadership role in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hunga ...

.

*1957- Larbi Ben Mhidi, an Algerian Revolutionary leader also one of the 6 leaders of the FLN that fought for the independence of Algeria against the French. He was captured, arrested and tortured to death by the French.

*1961 – Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba (; 2 July 1925 – 17 January 1961) was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then known as the Republic of the Congo) from June u ...

, born in 1925, assassinated in Mwadingusha in Katanga, Prime minister at the time in 61. He is considered the symbol of the independence of Congo.

*1963 – Medgar Evers

Medgar Wiley Evers (; July 2, 1925June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist and the NAACP's first field secretary in Mississippi, who was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith. Evers, a decorated U.S. Army combat veteran who had served i ...

, assassinated in 1963 for his leadership of the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

in his home state Mississippi.

*1965 – Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of Is ...

, assassinated in 1965 on account of his leadership in Black nationalism

Black nationalism is a type of racial nationalism or pan-nationalism which espouses the belief that black people are a race, and which seeks to develop and maintain a black racial and national identity. Black nationalist activism revolves ar ...

.

*1966 – Sayyid Qutb

Sayyid 'Ibrāhīm Ḥusayn Quṭb ( or ; , ; ar, سيد قطب إبراهيم حسين ''Sayyid Quṭb''; 9 October 1906 – 29 August 1966), known popularly as Sayyid Qutb ( ar, سيد قطب), was an Egyptians, Egyptian author, educato ...

, an Egyptian Islamist and a key figure in the founding of modern political Islam

Political Islam is any interpretation of Islam as a source of political identity and action. It can refer to a wide range of individuals and/or groups who advocate the formation of state and society according to their understanding of Islamic pri ...

in the 1950s. Hung in 1966 for plotting the assassination of Egyptian president

The president of Egypt is the executive head of state of Egypt and the de facto appointer of the official head of government under the Egyptian Constitution of 2014. Under the various iterations of the Constitution of Egypt following the Egy ...

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

.

*1967 – Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

, an Argentine

Argentines (mistakenly translated Argentineans in the past; in Spanish (masculine) or (feminine)) are people identified with the country of Argentina. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Argentines, s ...

Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective, to refer to something that has a major, sudden impact on society or on some aspect of human endeavor.

...

. Executed for trying to foment revolution in Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

.

*1968 – Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, assassinated in 1968 for his leadership of the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

.

*1977 – Steve Biko

Bantu Stephen Biko (18 December 1946 – 12 September 1977) was a South African anti-apartheid activist. Ideologically an African nationalist and African socialist, he was at the forefront of a grassroots anti-apartheid campaign known ...

, a South African activist killed in Police Custody for his anti-Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

activism.

*1978 – Harvey Milk

Harvey Bernard Milk (May 22, 1930 – November 27, 1978) was an American politician and the first openly gay man to be elected to public office in California, as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Milk was born and raised in N ...

, the first openly gay city council member of a major US city (San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

), murdered by fellow city council member Dan White

Daniel James White (September 2, 1946 – October 21, 1985) was an American politician who assassinated San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk, on Monday, November 27, 1978, at City Hall. White was convicted of manslaugh ...

who had previously expressed prejudiced views against homosexuals.

*1980 – Óscar Romero

Óscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez (15 August 1917 – 24 March 1980) was a prelate of the Catholic Church in El Salvador. He served as Auxiliary Bishop of the Archdiocese of San Salvador, the Titular Bishop of Tambeae, as Bishop of Santiago ...

, Archbishop of San Salvador

San Salvador (; ) is the capital and the largest city of El Salvador and its eponymous department. It is the country's political, cultural, educational and financial center. The Metropolitan Area of San Salvador, which comprises the capital i ...

, assassinated on the orders of far-right death-squad leader Roberto D'Aubuisson

Roberto D'Aubuisson Arrieta (23 August 1943 – 20 February 1992) was a neo-fascist Salvadoran soldier, politician and death squad leader. In 1981, he co-founded and became the first leader of the far-right Nationalist Republican Alliance ...

after calling on Salvadoran soldiers to disobey commands to kill civilians.

*1981 – Bobby Sands

Robert Gerard Sands ( ga, Roibeárd Gearóid Ó Seachnasaigh; 9 March 1954 – 5 May 1981) was a member (and leader in the Maze prison) of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) who died on hunger strike while imprisoned at HM Prison Maze ...

, an Irish Republican who died during a hunger strike while imprisoned.

*1987 – Thomas Sankara

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara (; 21 December 1949 – 15 October 1987) was a Burkinabé military officer, Marxist–Leninist revolutionary, and Pan-Africanist, who served as President of Burkina Faso from his coup in 1983 to his deposition and ...

, a Burkinabé Marxist revolutionary, deposed and assassinated for his efforts to transform the Republic of Upper Volta

The Republic of Upper Volta (french: République de Haute-Volta) was a landlocked West African country established on 11 December 1958 as a self-governing colony within the French Community. Before becoming autonomous, it had been part of the ...

(which he renamed Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮, italic=no) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of , bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana to the ...

) into a socialist state

A socialist state, socialist republic, or socialist country, sometimes referred to as a workers' state or workers' republic, is a Sovereign state, sovereign State (polity), state constitutionally dedicated to the establishment of socialism. The ...

.

*1989 – Safdar Hashmi

Safdar Hashmi (12 April 1954 – 2 January 1989) was a communist playwright and director, best known for his work with street theatre in India. He was also an actor, lyricist, and theorist, and he is still considered an important voice in Indian ...

, an India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

n Marxist revolutionary playwright and actor, killed while performing a street play in support of workers' rights.

*1993 - Thembisile Chris Hani

Chris Hani (28 June 1942 – 10 April 1993), born Martin Thembisile Hani , was the leader of the South African Communist Party and chief of staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe, uMkhonto we Sizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC) ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

anti-Apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

Activist, ANC

The African National Congress (ANC) is a social-democratic political party in South Africa. A liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid, it has governed the country since 1994, when the first post-apartheid election install ...

military wing Mkhonto weSizwe commander was assassinated by Janusz Walus Janusz () is a masculine Polish given name.

It is also the shortened form of January and Januarius.

People

*Janusz Akermann (born 1957), Polish painter

*Janusz Bardach, Polish gulag survivor and physician

* Janusz Bielański, Roman Catholic prie ...

outside his home.

*1995 – Ken Saro-Wiwa

Kenule Beeson "Ken" Saro-Wiwa (10 October 1941 – 10 November 1995) was a Nigerian writer, television producer, and environmental activist. Ken Saro-Wiwa was a member of the Ogoni people, an ethnic minority in Nigeria whose homeland, Ogonilan ...

, Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

n activist killed for speaking against the destruction of indigenous Ogoni

The Ogonis are a people in the Rivers South East senatorial district of Rivers State, in the Niger Delta region of southern Nigeria. They number just over 2 million and live in a homeland which they also refer to as Ogoniland. They share common ...

land.

*1995 – Iqbal Masih

Iqbal Masih ( pa, اقبال مسیح; 1983 – 16 April 1995) was a Pakistani Christian child labourer and activist who campaigned against abusive child labour in Pakistan.

He was assassinated on 16 April 1995. On 23 March 2022, he was p ...

, a Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

i child killed at age 12 for advocating against child labor.

Revolutionary martyr

The term "revolutionary martyr" usually relates to those dying inrevolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

ary struggle. During the 20th century, the concept was developed in particular in the culture and propaganda of communist or socialist revolutions, although it was and is also used in relation to nationalist revolutions.

* In the culture of North Korea

The contemporary culture of North Korea is based on traditional Korean culture, but has developed since the division of Korea in 1945. ''Juche'' ideology formed by Kim Il-sung (1948–1994) asserts Korea's cultural distinctiveness and creativit ...

, martyrdom is a consistent theme in the ongoing revolutionary struggle, as depicted in literary works such as ''Sea of Blood

''Sea of Blood'' () is a propagandist North Korean opera credited to Kim Il-sung. It was first produced as an opera by Sea of Blood Theatrical Troupe (''Pibada Guekdan'') in 1971. It was then later adapted into a novel by the Choseon Novelist ...

''. There is also a Revolutionary Martyrs' Cemetery

Taesongsan Revolutionary Martyrs' Cemetery () is a cemetery and memorial to the North Korean soldiers fighting for freedom and independence against Japanese rule. It is located near the top of Mount Taesong (Taesongsan) in the Taesong-guyŏk ...

in the country.

* In Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, those who died in the independence struggle are often honoured as martyrs, or ''liệt sĩ'' in Vietnamese. Nguyễn Thái Học

Nguyễn Thái Học ( Hán tự: 阮 太 學; 1 December 1902 – 17 June 1930) was a Vietnamese revolutionary who was the founding leader of the Việt Nam Quốc Dân Đảng, the Vietnamese Nationalist Party. He was captured and executed by ...

and schoolgirl Võ Thị Sáu are two examples.Vietnam At War Mark Philip Bradley – 2009 "As the concept of 'sacrifice' (hi sinh) came to embody the state's narrative of sacred war (chien tranh than thanh), the ultimate sacrifice was considered to be death in battle as a 'revolutionary martyr' (liet si)."

* In India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, the term "revolutionary martyr" is often used when referring to the world history of socialist struggle. Guru Radha Kishan was a notable Indian independence activist and communist politician known to have used this phrasing.

*In Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, 132 years of colonialism and the Algerian War for independence

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

may have created up to 20 million martyrs. Algeria in the Arabic world is known as "the land of a million and a half martyrs." In the last 6 years leading to 1962, there were 1.6 million Algerian martyrs. The famous movie ''The Battle of Algiers

ar, Maʿrakat al-Jazāʾir

, director = Gillo Pontecorvo

, producer = Antonio MusuSaadi Yacef

, writer = Franco Solinas

, story = Franco SolinasGillo Pontecorvo

, starring = Jean MartinSaadi YacefBrahim H ...

'' is seen as a classic and a controversial movie that depicts the last 6 years of the Algerian Revolution including the famous revolutionary leader, Ali La Pointe.

See also

References

Bibliography

"Martyrs"

''Catholic Encyclopedia'' * Foster, Claude R. Jr. (1995). ''Paul Schneider, the Buchenwald apostle: a Christian martyr in Nazi Germany: A Sourcebook on the German Church Struggle''. Westchester, PA: SSI Bookstore, West Chester University. * History.com Editors. "Abolitionist John Brown Is Hanged". History.com, 4 Mar. 2010, www.history.com/this-day-in-history/john-brown-hanged.

Further reading

* Bélanger, Jocelyn J., et al. "The Psychology of Martyrdom: Making the Ultimate Sacrifice in the Name of a Cause." Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 107.3 (2014): 494–515. Print. * Kateb, George. "Morality and Self-Sacrifice, Martyrdom and Self-Denial." Social Research 75.2 (2008): 353–394. Print. * Olivola, Christopher Y. and Eldar Shafir. "The Martyrdom Effect: When Pain and Effort Increase Prosocial Contributions." Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 26, no. 1 (2013): 91–105. * PBS. "Plato and the Legacy of Socrates." PBS. https://www.pbs.org/empires/thegreeks/background/41a.html (accessed October 21, 2014). * Reeve, C. D. C.. ''A Plato Reader: Eight Essential Dialogues''. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Pub. Co., 2012.External links

– 16th century classic book, accounts of martyrdoms

''Encyclopedia of Politics and Religion''. {{Authority control Religious terminology Jungian archetypes