Martian (other) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a setting

Setting may refer to:

* A location (geography) where something is set

* Set construction in theatrical scenery

* Setting (narrative), the place and time in a work of narrative, especially fiction

* Setting up to fail a manipulative technique to eng ...

in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s as the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

was evidently lifeless. At the time, the predominant genre depicting Mars was utopian fiction. Contemporaneously, the mistaken belief that there are canals on Mars emerged and made its way into fiction. '' The War of the Worlds'', H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

alien invasion of

Before the 1800s,

Before the 1800s,

In

In

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

by sinister Martians, was published in 1897 and went on to have a large influence on the science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

genre. Life on Mars appeared frequently in fiction throughout the first half of the 1900s. Apart from enlightened as in the utopian works from the turn of the century, or evil as in the works inspired by Wells, intelligent and human-like Martians also began to be depicted as decadent, a portrayal that was popularized by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American author, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best-known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, he ...

in the ''Barsoom

Barsoom is a fictional representation of the planet Mars created by American pulp fiction author Edgar Rice Burroughs. The first Barsoom tale was serialized as ''Under the Moons of Mars'' in 1912 and published as a novel as ''A Princess of Mars' ...

'' series and adopted by Leigh Brackett among others. Besides these, more exotic lifeforms appeared in stories like Stanley G. Weinbaum's "A Martian Odyssey

"A Martian Odyssey" is a science fiction short story by American writer Stanley G. Weinbaum originally published in the July 1934 issue of ''Wonder Stories''. It was Weinbaum's second published story (in 1933 he had sold a romantic novel, ''The ...

". The theme of colonizing Mars replaced stories about native inhabitants of the planet in the second half of the 1900s following emerging evidence of the planet being inhospitable to life, eventually confirmed by data from Mars exploration

The planet Mars has been explored remotely by spacecraft. Probes sent from Earth, beginning in the late 20th century, have yielded a large increase in knowledge about the Martian system, focused primarily on understanding its geology and habit ...

probes. A significant minority of works nevertheless persisted in portraying Mars in a way that was by then scientifically outdated, including Ray Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury (; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of modes, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, and r ...

's '' The Martian Chronicles''. Terraforming Mars to enable human habitation

Habitability refers to the adequacy of an environment for human living. Where housing is concerned, there are generally local ordinances which define habitability. If a residence complies with those laws it is said to be habitable. In extreme e ...

has been another major theme, especially in the final quarter of the century, with the most prominent example being Kim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson (born March 23, 1952) is an American writer of science fiction. He has published twenty-two novels and numerous short stories and is best known for his ''Mars'' trilogy. His work has been translated into 24 languages. Many ...

's ''Mars'' trilogy. Stories of the first human mission to Mars appeared throughout the 1990s in response to the Space Exploration Initiative

The Space Exploration Initiative was a 1989–1993 space public policy initiative of the George H. W. Bush administration.

On July 20, 1989, the 20th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, US President George H. W. Bush announced plans for ...

. The moons of Mars— Phobos and Deimos Deimos, a Greek word for ''dread'', may refer to:

* Deimos (deity), one of the sons of Ares and Aphrodite in Greek mythology

* Deimos (moon), the smaller and outermost of Mars' two natural satellites

* Elecnor Deimos, a Spanish aerospace company

* ...

—have made only sporadic appearances in fiction.

Early depictions

Before the 1800s,

Before the 1800s, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

did not get much attention in fiction writing as a primary setting

Setting may refer to:

* A location (geography) where something is set

* Set construction in theatrical scenery

* Setting (narrative), the place and time in a work of narrative, especially fiction

* Setting up to fail a manipulative technique to eng ...

, though it did appear in some stories visiting multiple locations in the Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

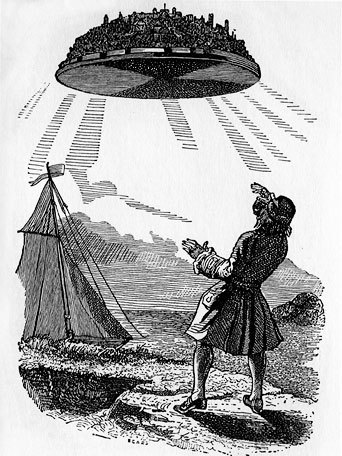

. The first fictional tour of the planets, the 1656 work '' Itinerarium exstaticum'' by Athanasius Kircher, portrays Mars as a volcanic wasteland. It also appears briefly in the 1686 work ''Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds

''Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds'' (french: Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes) is a popular science book by French author Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, published in 1686.

Content

The work consists of six lessons popularizin ...

'' by Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle, but is largely dismissed as uninteresting due to its presumed similarity to Earth. Mars is home to spirits in both the 1758 work '' De Telluribus in Mundo Nostro Solari'' (English title: '' Concerning the Earths in Our Solar System'') by Emanuel Swedenborg and the 1765 novel ''Voyage de Milord Céton dans les Sept Planètes

Voyage(s) or The Voyage may refer to:

Literature

*''Voyage : A Novel of 1896'', Sterling Hayden

* ''Voyage'' (novel), a 1996 science fiction novel by Stephen Baxter

*''The Voyage'', Murray Bail

* "The Voyage" (short story), a 1921 story by ...

'' by Marie-Anne de Roumier-Robert

Marie-Anne de Roumier-Robert was an 18th-century French writer. She wrote one of the earliest known works of science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals wi ...

. It later appeared alongside the other planets in the anonymously published 1839 novel ''A Fantastical Excursion into the Planets

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes'' ...

'' where it is divided between the Roman gods

The Roman deities most widely known today are those the Romans identified with Greek counterparts (see ''interpretatio graeca''), integrating Greek myths, iconography, and sometimes religious practices into Roman culture, including Latin litera ...

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and the second-smallest planet in the Solar System, only being larger than Mercury (planet), Mercury. In the English language, Mars is named for the Mars (mythology), Roman god of war. Mars is a terr ...

and Vulcan

Vulcan may refer to:

Mythology

* Vulcan (mythology), the god of fire, volcanoes, metalworking, and the forge in Roman mythology

Arts, entertainment and media Film and television

* Vulcan (''Star Trek''), name of a fictional race and their home p ...

, the anonymously published 1873 novel '' A Narrative of the Travels and Adventures of Paul Aermont among the Planets''—where, unlike the other planets, it is culturally rather similar to Earth—and the 1883 novel '' Aleriel, or A Voyage to Other Worlds'' by W. S. Lach-Szyrma

The Reverend Wladislaw Somerville Lach-Szyrma, M.A., F.R.H.S. (25 December 1841 – 25 June 1915) was a British curate, historian and science fiction writer. He is credited as one of the first science fiction writers to use the word "Martian" ...

where a visitor from Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is sometimes called Earth's "sister" or "twin" planet as it is almost as large and has a similar composition. As an interior planet to Earth, Venus (like Mercury) appears in Earth's sky never fa ...

relates the details of Martian society to Earthlings.

Mars became the most popular extraterrestrial location in fiction in the late 1800s as it became clear that the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It is the fifth largest satellite in the Solar System and the largest and most massive relative to its parent planet, with a diameter about one-quarter that of Earth (comparable to the width of ...

was devoid of life. A recurring theme in this time period was that of reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the philosophical or religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new life in a different physical form or body after biological death. Resurrection is a ...

on Mars, reflecting an upswing in interest in the paranormal in general and in relation to Mars in particular. Humans are reborn on Mars in the 1889 novel '' Uranie'' by Camille Flammarion

Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS (; 26 February 1842 – 3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction ...

as a form of afterlife

The afterlife (also referred to as life after death) is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's identity or their stream of consciousness continues to live after the death of their physical body. The surviving ess ...

, the 1896 novel '' Daybreak: The Story of an Old World'' by James Cowan depicts Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

reincarnated there, and the protagonist of the 1903 novel '' The Certainty of a Future Life in Mars'' by Louis Pope Gratacap receives a message in Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

from his deceased father on Mars. Another trope introduced during this time is Mars having a different local name such as Glintan in the 1889 novel ''Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet

'' Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet'' is a short novel by Hugh MacColl

Hugh MacColl (before April 1885 spelled as Hugh McColl; 1831–1909) was a Scottish mathematician, logician and novelist.

Life

MacColl was the youngest son of a poor Highland ...

'' by Hugh MacColl

Hugh MacColl (before April 1885 spelled as Hugh McColl; 1831–1909) was a Scottish mathematician, logician and novelist.

Life

MacColl was the youngest son of a poor Highland family that was at least partly Gaelic-speaking. Hugh's father died w ...

, Oron in the 1892 novel ''Messages from Mars, By Aid of the Telescope Plant

A message is a discrete unit of communication intended by the source for consumption by some recipient or group of recipients. A message may be delivered by various means, including courier, telegraphy, carrier pigeon and electronic bus.

A ...

'' by Robert D. Braine

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory, honou ...

, and Barsoom

Barsoom is a fictional representation of the planet Mars created by American pulp fiction author Edgar Rice Burroughs. The first Barsoom tale was serialized as ''Under the Moons of Mars'' in 1912 and published as a novel as ''A Princess of Mars' ...

in the 1912 novel '' A Princess of Mars'' by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American author, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best-known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, he ...

. This would carry on to later works such as the 1938 novel ''Out of the Silent Planet

''Out of the Silent Planet'' is a science fiction novel by the British author C. S. Lewis, first published in 1938 by John Lane, The Bodley Head. Two sequels were published in 1943 and 1945, completing the ''Space Trilogy''.

Plot

While on a ...

'' by C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

which refers to the planet as Malacandra. Several stories also depict Martians speaking Earth languages and provide explanations of varying levels of preposterousness: in the 1899 novel '' Pharaoh's Broker'' by Ellsworth Douglass they speak Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

as Mars goes through the same historical phases as Earth with a delay of a few thousand years and currently corresponds to the captivity of the Israelites in Biblical Egypt

Biblical Egypt (; ''Mīṣrāyīm''), or Mizraim, is a theological term used by historians and scholars to differentiate between Ancient Egypt as it is portrayed in Judeo-Christian texts and what is known about the region based on archaeological e ...

, in the 1901 novel ''A Honeymoon in Space

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes'' ...

'' by George Griffith

George Griffith (1857–1906), full name George Chetwynd Griffith-Jones, was a prolific British science fiction writer and noted explorer who wrote during the late Victorian and Edwardian age. Many of his visionary tales appeared in magazin ...

they speak English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

because they acknowledge it as the "most convenient" language of all, and in the 1920 novel ''A Trip to Mars

''Himmelskibet'', ''Excelsior'' / ''A Trip to Mars'' / ''Das Himmelschiff'' is a 1918 Danish film about a trip to Mars. In 2006, the film was restored and re-released on DVD by the Danish Film Institute.

Phil Hardy says it is "the film that mark ...

'' by Marcianus Rossi

Marcian (; la, Marcianus, link=no; grc-gre, Μαρκιανός, link=no ; 392 – 27 January 457) was Roman emperor of the Byzantine Empire, East from 450 to 457. Very little of his life before becoming emperor is known, other than that he wa ...

they speak Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

as a result of having been taught the language by a Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

who was flung into space by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79. Martians were often portrayed as existing within a racial hierarchy: the 1895 novel ''Journey to Mars

''Journey to Mars the Wonderful World: Its Beauty and Splendor; Its Mighty Races and Kingdoms; Its Final Doom'' is an 1894 in literature, 1894 science fiction novel written by Gustavus W. Pope. (The author called his work a "scientific novel.") T ...

'' by Gustavus W. Pope Gustavus may refer to:

*Gustavus, Alaska, a small community located on the edge of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve

*Gustavus Adolphus College, a private liberal arts college in southern Minnesota

*Gustavus (name), a given name

**Gustavus, the ...

features Martians with different skin colours (red, blue, and yellow) subject to strict anti-miscegenation laws

Anti-miscegenation laws or miscegenation laws are laws that enforce racial segregation at the level of marriage and intimate relationships by criminalization, criminalizing interracial marriage and sometimes also sex between members of different R ...

, Rossi's ''A Trip to Mars'' sees one portion of the Martian population described as "our inferior race, the same as your terrestrian negroes

In the English language, ''negro'' is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Black African heritage. The word ''negro'' means the color black in both Spanish and in Portuguese, where English took it from. The term can be ...

", and Burroughs' ''Barsoom'' series has red, green, yellow, and black Martians, with a white race that was responsible for the previous advanced civilization on Mars now extinct.

Means of travel

The issue of how humans would get to Mars was addressed in various ways: when not travelling there via spaceship as in the 1911 novel '' To Mars via the Moon: An Astronomical Story'' by Mark Wicks, they might use a flying carpet as in the 1905 novel '' Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation'' byEdwin Lester Arnold

Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (14 May 1857 – 1 March 1935) was an English author. Most of his works were issued under his working name of Edwin Lester Arnold.

Life and literary career

Arnold was born in Swanscombe, Kent, as son of Sir Edwin Arnol ...

, visit in a dream as in the 1899 play '' A Message from Mars'' by Richard Ganthony, teleport via astral projection

Astral projection (also known as astral travel) is a term used in esotericism to describe an intentional out-of-body experience (OBE) that assumes the existence of a subtle body called an " astral body" through which consciousness can functio ...

as in the 1912 novel ''A Princess of Mars'' by Edgar Rice Burroughs, or use a long-range communication device while staying on Earth as in the 1892 novel ''Messages from Mars, By Aid of the Telescope Plant'' by Robert D. Braine. Anti-gravity is employed in the 1880 novel ''Across the Zodiac

''Across the Zodiac: The Story of a Wrecked Record'' (1880) is a science fiction novel by Percy Greg, who has been credited as an originator of the sword and planet subgenre of science fiction.

Plot

The book details the creation and use of a ...

'' by Percy Greg

Percy Greg (7 January 1836 Bury – 24 December 1889, Chelsea), son of William Rathbone Greg, was an English writer.

Percy Greg, like his father, wrote about politics, but his views were violently reactionary: his ''History of the United States t ...

and the 1890 novel '' A Plunge into Space'' by Robert Cromie. Occasionally, the method of transport is not addressed at all. Some stories take the opposite approach of having Martians come to Earth; examples include 1891 novel '' The Man from Mars: His Morals, Politics and Religion'' by Thomas Blot (pseudonym of William Simpson) and the 1893 novel ''A Cityless and Countryless World

A, or a, is the first letter and the first vowel of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''a'' (pronounced ), plural ''aes'' ...

'' by Henry Olerich.

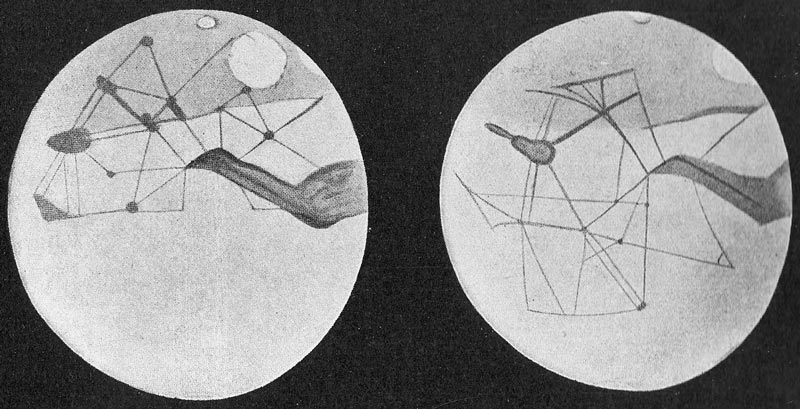

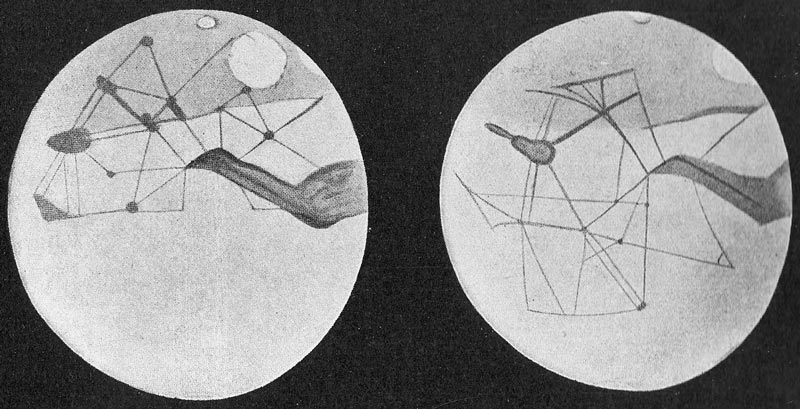

Canals

During the 1877 opposition of Mars, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli announced the discovery of linear structures he dubbed ''canali'' (literally "channels", but widely translated as "canals") on the Martian surface. These were generally interpreted—by those who accepted their existence—as waterways, and they made their earliest appearance in fiction in the anonymously published 1883 novel '' Politics and Life in Mars'', where the Martians live in the water. Schiaparelli's observations inspired Percival Lowell to speculate that these were artificial constructs and write a series of non-fiction books—''Mars'' in 1895, ''Mars and Its Canals'' in 1906, and ''Mars as the Abode of Life'' in 1908—popularizing the idea. Canals became a feature of romantic portrayals of Mars such as the 1912 novel ''A Princess of Mars'' by Edgar Rice Burroughs. Works that did not depict any waterways on Mars typically explained the appearance of straight lines on the surface in some other way, such as simooms or large tracts of vegetation. While they quickly fell out of favour as a serious scientific theory, largely as a result of higher-quality telescopic observations by astronomers such as E. M. Antoniadi failing to detect them, canals continued to make sporadic appearances in fiction in works such as the 1938 novel ''Out of the Silent Planet'' by C. S. Lewis and the 1949 novel '' Red Planet'' by Robert A. Heinlein until the flyby of Mars by Mariner 4 in 1965 conclusively determined that they were mereoptical illusion

Within visual perception, an optical illusion (also called a visual illusion) is an illusion caused by the visual system and characterized by a visual perception, percept that arguably appears to differ from reality. Illusions come in a wide v ...

s.

Utopias

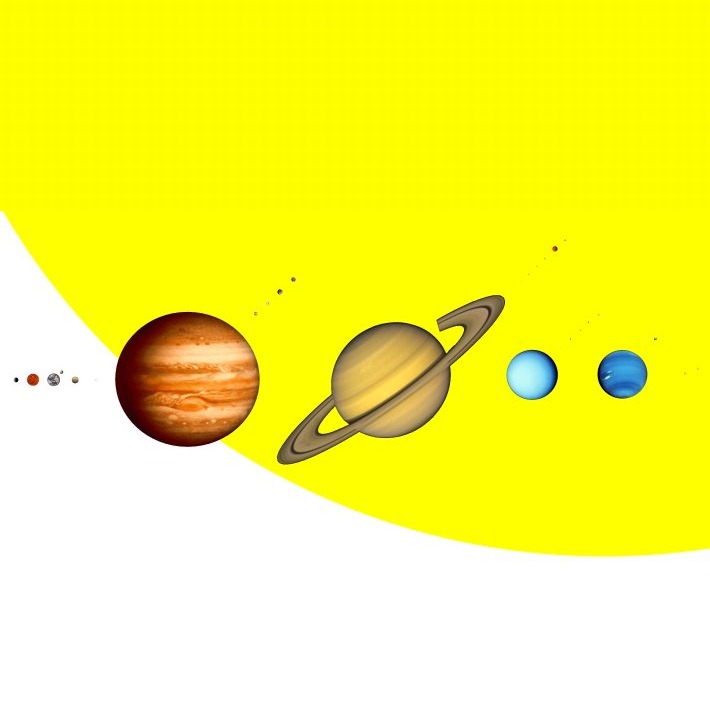

Because early versions of the nebular hypothesis ofSolar System formation

The formation of the Solar System began about 4.6 billion years ago with the gravitational collapse of a small part of a giant molecular cloud. Most of the collapsing mass collected in the center, forming the Sun, while the rest flattened into a ...

held that the planets were formed sequentially starting at the outermost planets, some authors envisioned Mars as an older and more mature world than the Earth, and it became the setting for a large number of utopian works of fiction. This genre made up the majority of stories about Mars in the late 1800s and continued to be represented through the early 1900s. The earliest of these works—as well as the first work of science fiction set primarily on Mars—was the 1880 novel ''Across the Zodiac'' by Percy Greg. The 1887 novel '' Bellona's Husband: A Romance'' by William James Roe

William James Roe II (September 1, 1843 – April 3, 1921) was an American author, artist, philosopher, and businessman.

Early life

Roe was born to William James Roe I (1811–1875) and Anna Lawrence Clark Roe (1814–1914) on September 1, 1 ...

portrays a Martian society where everyone ages backwards. The 1890 novel ''A Plunge into Space'' by Robert Cromie depicts a society that is so advanced that life there has become dull, and as a result the humans who visit succumb to boredom and leave ahead of schedule—to the approval of the Martians, who have come to view them as a corrupting influence. The 1892 novel ''Messages from Mars, By Aid of the Telescope Plant'' by Robert D. Braine is unusual in portraying a completely rural Martian utopia without any cities. An early work of feminist science fiction

Feminist science fiction is a subgenre of science fiction (abbreviated "SF") focused on theories that include feminist themes including but not limited to gender inequality, sexuality, race, economics, reproduction, and environment. Feminist ...

, the 1893 novel ''Unveiling a Parallel

''Unveiling a Parallel: A Romance'' is a Feminism, feminist science fiction and Utopian and dystopian fiction, utopian novel published in 1893 in literature, 1893. The first edition of the book attributed authorship to "Two Women of the West." Th ...

: A Romance'' by Alice Ilgenfritz Jones and Ella Robinson Merchant (writing jointly as "Two Women of the West"), depicts a man from Earth visiting two egalitarian societies on Mars: one where women have adopted male vices and one where equality has brought out everyone's best qualities. The 1897 novel '' Auf zwei Planeten'' by Kurd Lasswitz

Kurd Lasswitz (german: link=no, Kurd Laßwitz; 20 April 1848 – 17 October 1910) was a German author, scientist, and philosopher. He has been called "the father of German science fiction". He sometimes used the pseudonym ''Velatus''.

Biograph ...

contrasts a utopian society on Mars with that society's colonialist

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

actions on Earth. The book was translated into several languages and was highly influential in Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

, including inspiring rocket scientist Wernher von Braun, but did not receive a translation into English until the 1970s which limited its impact in the Anglosphere

The Anglosphere is a group of English-speaking world, English-speaking nations that share historical and cultural ties with England, and which today maintain close political, diplomatic and military co-operation. While the nations included in d ...

. The 1910 novel ''The Man from Mars, Or Service for Service's Sake

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in En ...

'' by Henry Wallace Dowding portrays a civilization on Mars based on a variation on Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

where woman was created first.

In

In Russian science fiction

Science fiction and fantasy have been part of mainstream Russian literature since the 18th century. Russian fantasy developed from the centuries-old traditions of Slavic mythology and folklore. Russian science fiction emerged in the mid-19th c ...

, Mars became the setting for socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

utopias and revolutions. The 1908 novel ''Red Star

A red star, five-pointed and filled, is a symbol that has often historically been associated with communist ideology, particularly in combination with the hammer and sickle, but is also used as a purely socialist symbol in the 21st century. I ...

'' by Alexander Bogdanov

Alexander Aleksandrovich Bogdanov (russian: Алекса́ндр Алекса́ндрович Богда́нов; – 7 April 1928), born Alexander Malinovsky, was a Russian and later Soviet physician, philosopher, science fiction writer, and B ...

is the primary example of this, and inspired numerous others. ''Red Star'' portrays a socialist society on Mars from the perspective of a Russian Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

invited there, where the struggle between classes has been replaced with a common struggle against the harshness of nature. The 1913 prequel ''Engineer Menni

''Red Star'' (russian: Красная звезда) is Alexander Bogdanov's 1908 science fiction novel about a communist society on Mars. The first edition was published in St. Petersburg in 1908, before eventually being republished in Moscow a ...

'', also by Bogdanov, is set several centuries earlier and serves as an origin story for the Martian society by detailing the events of the revolution that brought it about. Another prominent example is the 1922 novel '' Aelita'' by Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy—along with its 1924 film adaptation, the earliest Soviet science fiction film—which adapts the story of the 1905 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution of 1905,. also known as the First Russian Revolution,. occurred on 22 January 1905, and was a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The mass unrest was directed again ...

to the Martian surface. ''Red Star'' and ''Aelita'' are in some ways opposites. ''Red Star'', written between the unsuccessful 1905 Russian Revolution and the successful 1917 Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, sees Mars as a socialist utopia that Earth can learn from, whereas in ''Aelita'' the socialist revolution is instead exported from the early Soviet Russia to Mars. ''Red Star'' depicts a utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', describing a fictional ...

on Mars, in contrast to the dystopia

A dystopia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- "bad, hard" and τόπος "place"; alternatively cacotopiaCacotopia (from κακός ''kakos'' "bad") was the term used by Jeremy Bentham in his 1818 Plan of Parliamentary Reform (Works, vol. 3, p. 493). ...

initially found on Mars in ''Aelita''—though both are technocracies

Technocracy is a form of government in which the decision-maker or makers are selected based on their expertise in a given area of responsibility, particularly with regard to scientific or technical knowledge. This system explicitly contrasts wi ...

. ''Red Star'' is a sincere and idealistic work of traditional utopian fiction, whereas ''Aelita'' is a parody

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

.

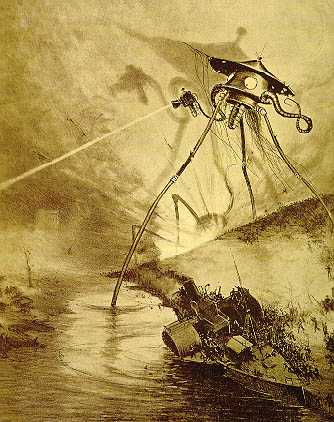

''The War of the Worlds''

The 1897 novel ''The War of the Worlds'' byH. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

alien invasion of  An unauthorized sequel—''

An unauthorized sequel—''

The portrayal of Martians as superior to Earthlings appeared throughout the utopian fiction of the late 1800s. In-depth treatment of the nuances of the concept was pioneered by

The portrayal of Martians as superior to Earthlings appeared throughout the utopian fiction of the late 1800s. In-depth treatment of the nuances of the concept was pioneered by

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

by Mars in search of resources, represented a turning point in Martian fiction. Rather than being portrayed as essentially human, the Martians have a completely inhuman appearance and cannot be communicated with. Rather than being noble creatures to emulate, the Martians dispassionately kill and exploit the Earthlings like livestock—a critique of contemporary British colonialism

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. I ...

in general and its devastating effects on the Aboriginal Tasmanians in particular. The novel set the tone for the majority of the science-fictional depictions of Mars in the decades that followed in portraying the Martians as malevolent and Mars as a dying world. Beyond Martian fiction, the novel had a large influence on the broader science fiction genre, and inspired rocket scientist Robert H. Goddard

Robert Hutchings Goddard (October 5, 1882 – August 10, 1945) was an American engineer, professor, physicist, and inventor who is credited with creating and building the world's first Liquid-propellant rocket, liquid-fueled rocket. ...

. Says Bud Webster

Clarence Howard "Bud" Webster (July 27, 1952 – February 13, 2016) was an American science fiction and fantasy writer who is also known for his essays on both the history of science fiction and sf/fantasy anthologies as well. He is perhaps bes ...

, "It's impossible to overstate the importance of ''The War of the Worlds'' and the influence it's had over the years."

An unauthorized sequel—''

An unauthorized sequel—''Edison's Conquest of Mars

''Edison's Conquest of Mars'' is an 1898 science fiction novel by American astronomer and writer Garrett P. Serviss. It was written as a sequel to ''Fighters from Mars'', an unauthorized and heavily altered version of H. G. Wells's 1897 story '' ...

'' by Garrett P. Serviss

Garrett Putnam Serviss (March 24, 1851 – May 25, 1929) was an American astronomer, popularizer of astronomy, and early science fiction writer. Serviss was born in Sharon Springs, New York and majored in science at Cornell University. He t ...

—was released in 1898. Wells' story gained further notoriety in 1938 when a radio adaptation by Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

in the style of a news broadcast was mistaken for the real thing by some listeners in the US, leading to panic; less famously, a 1949 broadcast in Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

, Ecuador similarly resulted in a riot. Several additional sequels by other authors have been written since, including the 1975 novel ''Sherlock Holmes's War of the Worlds

''Sherlock Holmes's War of the Worlds'' is a sequel to H. G. Wells's science fiction novel ''The War of the Worlds'', written by Manly Wade Wellman and his son Wade Wellman, and published in 1975. It is a pastiche crossover which combines H. G. ...

'' by Manly Wade Wellman

Manly Wade Wellman (May 21, 1903 – April 5, 1986) was an American writer. While his science fiction and fantasy stories appeared in such pulps as ''Astounding Stories'', ''Startling Stories'', ''Unknown'' and ''Strange Stories'', Wellman is ...

and Wade Wellman

Wade, WADE, or Wades may refer to:

Places in the United States

* Wade, California, a former settlement

* Wade, Maine, a town

* Wade, Mississippi, a census-designated place

* Wade, North Carolina, a town

* Wade, Ohio, an unincorporated communi ...

, the 1976 novel '' The Second War of the Worlds'' by George H. Smith, the 1976 novel ''The Space Machine

''The Space Machine'', subtitled ''A Scientific Romance'', is a science fiction novel written by English writer Christopher Priest.

First published in 1976, it follows the travels of protagonists Edward Turnbull and Amelia Fitzgibbon. The pair ...

'' by Christopher Priest, the 2002 short story " Ulla, Ulla" by Eric Brown, and the 2017 novel ''The Massacre of Mankind

''The Massacre of Mankind'' (2017) is a science fiction novel by British writer Stephen Baxter, a sequel to H. G. Wells' 1898 classic ''The War of the Worlds'', authorised by the Wells estate. It is set in 1920, 13 years after the events of the ...

'' by Stephen Baxter.

Life on Mars

The term ''Martians'' typically refers to inhabitants of Mars that are similar to humans in terms of having such things aslanguage

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of met ...

and civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

Ci ...

, though it is also occasionally used to refer to extraterrestrials in general. These inhabitants of Mars have variously been depicted as enlightened, evil, and decadent.

Martians have also been equated with humans in different ways. They are the descendants of humans from Earth in some works such as the 1889 novel ''Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet

'' Mr. Stranger's Sealed Packet'' is a short novel by Hugh MacColl

Hugh MacColl (before April 1885 spelled as Hugh McColl; 1831–1909) was a Scottish mathematician, logician and novelist.

Life

MacColl was the youngest son of a poor Highland ...

'' by Hugh MacColl

Hugh MacColl (before April 1885 spelled as Hugh McColl; 1831–1909) was a Scottish mathematician, logician and novelist.

Life

MacColl was the youngest son of a poor Highland family that was at least partly Gaelic-speaking. Hugh's father died w ...

, where a close approach between Mars and Earth in the past allowed some humans to get to Mars, and the 1922 novel '' Aelita'' by Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy where they are descended from inhabitants of the lost civilization of Atlantis. Conversely, humans are revealed to be the descendants of Martians in the 1954 short story "Survey Team

Survey may refer to:

Statistics and human research

* Statistical survey, a method for collecting quantitative information about items in a population

* Survey (human research), including opinion polls

Spatial measurement

* Surveying, the techniq ...

" by Philip K. Dick

Philip Kindred Dick (December 16, 1928March 2, 1982), often referred to by his initials PKD, was an American science fiction writer. He wrote 44 novels and about 121 short stories, most of which appeared in science fiction magazines during his l ...

. Human settlers take on the new identity of Martians in the 1946 short story " The Million Year Picnic" by Ray Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury (; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of modes, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, and r ...

(later included in the 1950 fix-up novel '' The Martian Chronicles''), and this theme of "becoming Martians" came to be a recurring motif in Martian fiction toward the end of the century.

Enlightened

The portrayal of Martians as superior to Earthlings appeared throughout the utopian fiction of the late 1800s. In-depth treatment of the nuances of the concept was pioneered by

The portrayal of Martians as superior to Earthlings appeared throughout the utopian fiction of the late 1800s. In-depth treatment of the nuances of the concept was pioneered by Kurd Lasswitz

Kurd Lasswitz (german: link=no, Kurd Laßwitz; 20 April 1848 – 17 October 1910) was a German author, scientist, and philosopher. He has been called "the father of German science fiction". He sometimes used the pseudonym ''Velatus''.

Biograph ...

with the 1897 novel '' Auf zwei Planeten'', wherein the Martians visit Earth to share their more advanced knowledge with humans and gradually end up acting as an occupying colonial power. Martians sharing wisdom or knowledge with humans is a recurring element in these stories, and some works such as the 1952 novel '' David Starr, Space Ranger'' by Isaac Asimov

yi, יצחק אזימאװ

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Petrovichi, Russian SFSR

, spouse =

, relatives =

, children = 2

, death_date =

, death_place = Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

, nationality = Russian (1920–1922)Soviet (192 ...

depict Martians sharing their advanced technology with the inhabitants of Earth. Several depictions of enlightened Martians have a religious dimension: in the 1938 novel ''Out of the Silent Planet

''Out of the Silent Planet'' is a science fiction novel by the British author C. S. Lewis, first published in 1938 by John Lane, The Bodley Head. Two sequels were published in 1943 and 1945, completing the ''Space Trilogy''.

Plot

While on a ...

'' by C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

, Martians are depicted as Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

beings free from original sin

Original sin is the Christian doctrine that holds that humans, through the fact of birth, inherit a tainted nature in need of regeneration and a proclivity to sinful conduct. The biblical basis for the belief is generally found in Genesis 3 (t ...

, the Martian Klaatu who visits Earth in the 1951 film ''The Day the Earth Stood Still

''The Day the Earth Stood Still'' (a.k.a. ''Farewell to the Master'' and ''Journey to the World'') is a 1951 American science fiction film from 20th Century Fox, produced by Julian Blaustein and directed by Robert Wise. It stars Michael Renn ...

'' is a Christ figure, and the 1961 novel '' Stranger in a Strange Land'' by Robert A. Heinlein revolves around a human raised by Martians who brings their religion to Earth as a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

. In comics, the superhero Martian Manhunter first appeared in 1955. In the 1956 novel '' No Man Friday'' by Rex Gordon, an astronaut stranded on Mars encounters pacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

Martians and feels compelled to omit the human history of warfare lest they think of humans as savage creatures akin to cannibals.

Evil

The seminal depiction of Martians as evil creatures was the 1897 novel '' The War of the Worlds'' byH. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

This characterization dominated the pulp era of science fiction, appearing in works such as the 1928 short story " The Menace of Mars" by

Martians characterized by decadence were first portrayed in the 1905 novel '' Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation'' by

Martians characterized by decadence were first portrayed in the 1905 novel '' Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation'' by

In light of the '' Mariner'' and ''

In light of the '' Mariner'' and ''

Clarke's ''The Sands of Mars'' features one of the earliest depictions of terraforming Mars to make it more hospitable to human life; in the novel, the atmosphere of Mars is made breathable by plants that release oxygen from minerals in the

Clarke's ''The Sands of Mars'' features one of the earliest depictions of terraforming Mars to make it more hospitable to human life; in the novel, the atmosphere of Mars is made breathable by plants that release oxygen from minerals in the

While most stories by the middle of the century acknowledged that advances in

While most stories by the middle of the century acknowledged that advances in  Following the arrival of the ''

Following the arrival of the ''

Clare Winger Harris

Clare Winger Harris (January 18, 1891 – October 26, 1968) was an early science fiction writer whose short stories were published during the 1920s. She is credited as the first woman to publish stories under her own name in science fiction mag ...

, the 1931 short story " Monsters of Mars" by Edmond Hamilton, and the 1935 short story " Mars Colonizes" by Miles J. Breuer

Miles John Breuer (January 3, 1889 – October 14, 1945) was an American physician and science fiction writer of Czech origin. Although he had published elsewhere since the early 20th century, he is considered the part of the first generation of ...

. It quickly became regarded as a cliché

A cliché ( or ) is an element of an artistic work, saying, or idea that has become overused to the point of losing its original meaning or effect, even to the point of being weird or irritating, especially when at some earlier time it was consi ...

and inspired a kind of countermovement

A countermovement in sociology means a social movement opposed to another social movement. Whenever one social movement starts up, another group establishes themselves to undermine the previous group. Many social movements start out as an effect ...

that portrayed Martians as meek in works like the 1933 short story " The Forgotten Man of Space" by P. Schuyler Miller

Peter Schuyler Miller (February 21, 1912 – October 13, 1974) was an American science fiction writer and critic.

Life

Miller was raised in New York's Mohawk Valley, which led to a lifelong interest in the Iroquois Indians. He pursued this as ...

and the 1934 short story " Old Faithful" by Raymond Z. Gallun

Raymond Zinke Gallun (March 22, 1911 – April 2, 1994) was an American science fiction writer.

Early life

Gallun (rhymes with "balloon") was born in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, the son of Adolph and Martha Zinke Gallun. He graduated from high scho ...

. Outside of the pulps, the alien invasion theme pioneered by Wells appeared in Olaf Stapledon's 1930 novel ''Last and First Men

''Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future'' is a "future history" science fiction novel written in 1930 by the British author Olaf Stapledon. A work of unprecedented scale in the genre, it describes the history of humanity from t ...

''—with the twist that the invading Martians are cloud-borne and microscopic, and neither aliens nor humans recognize the other as a sentient species. In film, this theme gained popularity in 1953 with the releases of '' The War of the Worlds'' and '' Invaders from Mars''; later films about Martian invasions of Earth include the 1954 film ''Devil Girl from Mars

''Devil Girl from Mars'' is a 1954 British black-and-white science fiction film, produced by the Danziger Brothers, directed by David MacDonald and starring Patricia Laffan, Hugh McDermott, Hazel Court, Peter Reynolds, and Adrienne Corri. It ...

'', the 1962 film ''The Day Mars Invaded Earth

''The Day Mars Invaded Earth'' (a.k.a. ''Spaceraid 63'') is an independently made 1963 black-and-white CinemaScope science fiction film, produced and directed by Maury Dexter, that stars Kent Taylor, Marie Windsor, and William Mims. The film was ...

'', a 1986 remake of ''Invaders from Mars'' and three different adaptations of ''The War of the Worlds'' in 2005. Martians attacking humans who come to Mars appear in the 1948 short story " Mars Is Heaven!" by Ray Bradbury (later revised and included in ''The Martian Chronicles'' as "The Third Expedition"), where they use telepathic abilities to impersonate the humans' deceased loved ones before killing them. Comical portrayals of evil Martians appear in the 1954 novel ''Martians, Go Home

''Martians, Go Home'' is a science fiction comic novel by American writer Fredric Brown, published in the magazine ''Astounding Science Fiction'' in September 1954 and later by E. P. Dutton in 1955. The novel concerns a writer who witnesses an a ...

'' by Fredric Brown, where they are little green men

Little green men is the stereotypical portrayal of extraterrestrials as little humanoid creatures with green skin and sometimes with antennae on their heads. The term is also sometimes used to describe gremlins, mythical creatures known for cau ...

who wreak havoc by exposing secrets and lies; in the form of the cartoon character Marvin the Martian

Marvin the Martian is an extraterrestrial character from Warner Bros.' ''Looney Tunes'' and '' Merrie Melodies'' cartoons. He frequently appears as a villain in cartoons and video games, and wears a helmet and skirt. The character has been voice ...

introduced in the 1948 short "Haredevil Hare

''Haredevil Hare'' is a 1948 ''Looney Tunes'' cartoon directed by Chuck Jones. It stars Bugs Bunny and it is the debut for Marvin the Martian — although he is unnamed in this film—along with his Martian dog, K-9. Marvin's nasal voice ...

", who seeks to destroy Earth to get a better view of Venus; and in the 1996 film '' Mars Attacks!'', a pastiche of 1950s alien invasion films.

Decadent

Martians characterized by decadence were first portrayed in the 1905 novel '' Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation'' by

Martians characterized by decadence were first portrayed in the 1905 novel '' Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation'' by Edwin Lester Arnold

Edwin Lester Linden Arnold (14 May 1857 – 1 March 1935) was an English author. Most of his works were issued under his working name of Edwin Lester Arnold.

Life and literary career

Arnold was born in Swanscombe, Kent, as son of Sir Edwin Arnol ...

, one of the earliest examples of the planetary romance

Planetary romance is a subgenre of science fiction in which the bulk of the action consists of adventures on one or more exotic alien planets, characterized by distinctive physical and cultural backgrounds. Some planetary romances take place ag ...

subgenre. The idea was developed further and popularized by Edgar Rice Burroughs

Edgar Rice Burroughs (September 1, 1875 – March 19, 1950) was an American author, best known for his prolific output in the adventure, science fiction, and fantasy genres. Best-known for creating the characters Tarzan and John Carter, he ...

in the 1912–1943 ''Barsoom

Barsoom is a fictional representation of the planet Mars created by American pulp fiction author Edgar Rice Burroughs. The first Barsoom tale was serialized as ''Under the Moons of Mars'' in 1912 and published as a novel as ''A Princess of Mars' ...

'' series starting with '' A Princess of Mars''. Burroughs presents a Mars in need of human intervention to regain its vitality, a place where violence has replaced sexual desire. This version of Mars functions as a kind of stand-in for the bygone American frontier

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of United States territorial acquisitions, American expansion in mainland North Amer ...

, where protagonist John Carter—a Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

veteran of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

who is made superhumanly strong by the lower gravity of Mars—encounters indigenous Martians representing Native Americans. Burroughs' vision of Mars would go on to have an influence approaching but not quite reaching Wells', inspiring among others C. L. Moore

Catherine Lucille Moore (January 24, 1911 – April 4, 1987) was an American science fiction and fantasy writer, who first came to prominence in the 1930s writing as C. L. Moore. She was among the first women to write in the science fiction and ...

's stories about Northwest Smith

Northwest Smith is a fictional character, and the hero of a series of stories by science fiction writer C. L. Moore.

Story setting

Smith is a spaceship pilot and smuggler who lives in an undisclosed future time when humanity has colonized the ...

starting with the 1933 short story "Shambleau

"Shambleau" is a short story by American science fiction and fantasy writer C. L. Moore. Though it was her first professional sale, it is her most famous story. It first appeared in the November 1933 issue of ''Weird Tales'' and has been reprinte ...

". Another author who followed Burroughs' lead in the decadent portrayal of Mars and its inhabitants—while updating the politics to reflect shifting attitudes toward colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

and imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

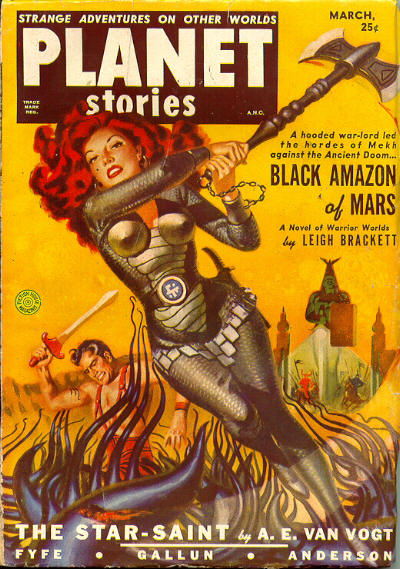

in the intervening years—was Leigh Brackett in works such as the 1940 short story "Martian Quest

Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a Setting (narrative), setting in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s as the Moon was evidently lifeless. ...

" and the 1944 novel '' Shadow Over Mars'', as well as the stories about Eric John Stark

Eric John Stark is a character created by the science fiction author Leigh Brackett. Stark is the hero of a series of pulp adventures set in a time when the Solar System has been colonized. His origin-story shares some characteristics with feral ...

including the 1949 short story "Queen of the Martian Catacombs

''The Secret of Sinharat'' is a science fantasy novel by American writer Leigh Brackett, set on the planet Mars, whose protagonist is Eric John Stark. The novel is expanded from the novella "Queen of the Martian Catacombs", published in the pulp ...

" and the 1951 short story "Black Amazon of Mars

''People of the Talisman'' is a science fantasy novel by American writer Leigh Brackett, set on the planet Mars, whose protagonist is Eric John Stark.

This story was first published under the title ''Black Amazon of Mars'' in the pulp magazine ...

" (later expanded into the 1964 novels '' The Secret of Sinharat'' and ''People of the Talisman

''People of the Talisman'' is a science fantasy novel by American writer Leigh Brackett, set on the planet Mars, whose protagonist is Eric John Stark.

This story was first published under the title ''Black Amazon of Mars'' in the pulp magazine ...

'', respectively). In the 1950 film '' Rocketship X-M'', Martians are depicted as disfigured cavepeople inhabiting a barren wasteland, descendants of the few survivors of a nuclear holocaust, while in the 1963 novel '' The Man Who Fell to Earth'' by Walter Tevis a survivor of nuclear holocaust on Mars comes to Earth for refuge but finds it to be similarly corrupt and degenerate. Inverting the premise of Heinlein's ''Stranger in a Strange Land'', the 1963 short story "A Rose for Ecclesiastes

"A Rose for Ecclesiastes" is a science fiction short story by American author Roger Zelazny, first published in the November 1963 issue of ''The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction'' with a special wraparound cover painting by Hannes Bok. I ...

" by Roger Zelazny sees decadent Martians visited by a preacher from Earth.

Past and non-humanoid life

In some stories where Mars is not inhabited by humanoid lifeforms, it used to be in the past or is inhabited by other types of lifeforms. The ruins of extinct Martian civilizations are depicted in the 1943 short story "Lost Art

Lost artworks are original pieces of art that credible sources indicate once existed but that cannot be accounted for in museums or private collections or are known to have been destroyed deliberately or accidentally, or neglected through igno ...

" by George O. Smith

George Oliver Smith (April 9, 1911 – May 27, 1981) (also known by the pseudonym Wesley Long) was an American science fiction author. He is not to be confused with George H. Smith, another American science fiction author.

Biography

Smith was ...

where their perpetual motion machine is recreated and the 1957 short story "Omnilingual

"Omnilingual" is a science fiction short story by American writer H. Beam Piper. Originally published in the February 1957 issue of ''Astounding Science Fiction'', it focuses on the problem of archaeology on an alien culture.

Synopsis

An expeditio ...

" by H. Beam Piper

Henry Beam Piper (March 23, 1904 – ) was an American science fiction writer. He wrote many short stories and several novels. He is best known for his extensive Terro-Human Future History series of stories and a shorter series of "Paratime" alt ...

where their fifty-thousand-year-old language is deciphered, while the 1933 novel ''The Outlaws of Mars

''The Outlaws of Mars'' is a science fiction novel by Otis Adelbert Kline in the planetary romance subgenre pioneered by Edgar Rice Burroughs. It was originally serialized in seven parts in the magazine '' Argosy'' beginning in November 1933. It ...

'' by Otis Adelbert Kline and the 1949 novel ''The Sword of Rhiannon

''The Sword of Rhiannon'' is a science fantasy novel by American writer Leigh Brackett, set in her usual venue of Mars. A 1942 Brackett story, "The Sorcerer of Rhiannon", also uses the name; however, it is the name of a place rather than a charac ...

'' by Leigh Brackett employ time travel

Time travel is the concept of movement between certain points in time, analogous to movement between different points in space by an object or a person, typically with the use of a hypothetical device known as a time machine. Time travel is a w ...

to set stories in the past when Mars was still alive.

The 1934 short story "A Martian Odyssey

"A Martian Odyssey" is a science fiction short story by American writer Stanley G. Weinbaum originally published in the July 1934 issue of ''Wonder Stories''. It was Weinbaum's second published story (in 1933 he had sold a romantic novel, ''The ...

" by Stanley G. Weinbaum broke new ground in portraying an entire Martian ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

wholly unlike that of Earth—inhabited by various species that are alien in anatomy and inscrutable in behaviour—and in depicting extraterrestrial life that is non-human and intelligent without being hostile. One Martian creature called Tweel is found to be intelligent, but have thought processes so inhuman that it is impossible for the alien and the human it encounters to learn each other's languages, and they can only communicate rudimentarily through the universal language

Universal language may refer to a hypothetical or historical language spoken and understood by all or most of the world's people. In some contexts, it refers to a means of communication said to be understood by all humans. It may be the idea of ...

of mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

. Isaac Asimov would later say that this story met the challenge John W. Campbell

John Wood Campbell Jr. (June 8, 1910 – July 11, 1971) was an American science fiction writer and editor. He was editor of ''Astounding Science Fiction'' (later called ''Analog Science Fiction and Fact'') from late 1937 until his death ...

made to science fiction writers in the 1940s: to write a creature who thinks at least as well as humans, yet not ''like'' humans.

Three different species of intelligent lifeforms appear on Mars in C. S. Lewis' 1938 novel ''Out of the Silent Planet'', only one of which is humanoid. In the 1943 short story " The Cave" by P. Schuyler Miller

Peter Schuyler Miller (February 21, 1912 – October 13, 1974) was an American science fiction writer and critic.

Life

Miller was raised in New York's Mohawk Valley, which led to a lifelong interest in the Iroquois Indians. He pursued this as ...

, various lifeforms endure on Mars long after the civilization that used to exist there has driven itself to extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

through ecological collapse

Ecological collapse refers to a situation where an ecosystem suffers a drastic, possibly permanent, reduction in carrying capacity for all organisms, often resulting in mass extinction. Usually, an ecological collapse is precipitated by a disastro ...

. The 1951 novel '' The Sands of Mars'' by Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Spac ...

features some indigenous life in the form of oxygen-producing plants and Martian creatures resembling Earth marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a po ...

s, but otherwise depicts a mostly desolate environment—reflecting then-emerging data about the scarcity of life-sustaining resources on Mars. Other novels of the 1950s likewise limited themselves to rudimentary lifeforms such as lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a composite organism that arises from algae or cyanobacteria living among filaments of multiple fungi species in a mutualistic relationship.tumbleweed

A tumbleweed is a structural part of the above-ground anatomy of a number of species of plants. It is a diaspore that, once mature and dry, detaches from its root or stem and rolls due to the force of the wind. In most such species, the tumble ...

that could conceivably exist in the absence of any appreciable atmosphere or quantities of water.

Lifeless Mars

In light of the '' Mariner'' and ''

In light of the '' Mariner'' and ''Viking

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

'' probes to Mars between 1965 and 1976 revealing the planet's inhospitable conditions, almost all fiction started to portray Mars as a lifeless world. The disappointment of finding Mars to be hostile to life is reflected in the 1970 novel '' The Earth Is Near'' by Luděk Pešek

Luděk Pešek (April 26, 1919 – December 4, 1999) was a Czech artist and novelist noted for his representations of astronomical subjects. Born in Kladno in what is now the Czech Republic, he died in Stäfa, Switzerland. The asteroid 6584 Ludekp ...

, which depicts the members of an astrobiological

Astrobiology, and the related field of exobiology, is an interdisciplinary scientific field that studies the origins, early evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. Astrobiology is the multidisciplinary field that investig ...

expedition on Mars driven to despair by the realization that their search for life there is futile. A handful of authors still found ways to place life on the red planet: microbial life exists on Mars in the 1977 novel ''The Martian Inca

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

'' by Ian Watson, and intelligent life is found in hibernation

Hibernation is a state of minimal activity and metabolic depression undergone by some animal species. Hibernation is a seasonal heterothermy characterized by low body-temperature, slow breathing and heart-rate, and low metabolic rate. It most ...

there in the 1977 short story " In the Hall of the Martian Kings" by John Varley John Varley may refer to:

* John Varley (canal engineer) (1740–1809), English canal engineer

* John Varley (painter) (1778–1842), English painter and astrologer

* John Varley (author) (born 1947), American science fiction author

* John Silvest ...

. By the turn of the millennium, the idea of microbial life on Mars gained popularity, appearing in the 1999 novel ''The Martian Race

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

'' by Gregory Benford

Gregory Benford (born January 30, 1941) is an American science fiction author and astrophysicist who is professor emeritus at the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California, Irvine. He is a contributing editor of ''Reason ...

and the 2001 novel ''The Secret of Life

"The Secret of Life" is a song written and recorded by American country music artist Gretchen Peters. It was then recorded by Faith Hill and released in April 1999 as the fifth and final single from her album ''Faith''. It peaked at No. 4 on the U. ...

'' by Paul J. McAuley

Paul J. McAuley (born 23 April 1955) is a British botanist and science fiction author. A biologist by training, McAuley writes mostly hard science fiction. His novels dealing with themes such as biotechnology, alternative history/alternative re ...

.

Human survival

As stories about an inhabited Mars fell out of favour in the mid-1900s amid mounting evidence of the planet's inhospitable nature, they were replaced by stories about enduring the harsh conditions of the planet. Themes in this tradition includecolonization

Colonization, or colonisation, constitutes large-scale population movements wherein migrants maintain strong links with their, or their ancestors', former country – by such links, gain advantage over other inhabitants of the territory. When ...

, terraforming, and pure survival stories.

Colonization

The colonization of Mars became a major theme in science fiction in the 1950s. The central piece of Martian fiction in this era wasRay Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury (; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of modes, including fantasy, science fiction, horror, mystery, and r ...

's 1950 fix-up novel '' The Martian Chronicles'', which contains a series of loosely connected stories depicting the first few decades of human efforts to colonize Mars. Unlike later works on this theme, ''The Martian Chronicles'' makes no attempt at realism (Mars has a breathable atmosphere, for instance, even though spectrographic analysis

Spectroscopy is the field of study that measures and interprets the electromagnetic spectra that result from the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter as a function of the wavelength or frequency of the radiation. Matter wa ...

had at that time revealed no detectable amounts of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

); Bradbury said that "Mars is a mirror, not a crystal" to be used in fiction for social commentary rather than predicting the future. Contemporary issues touched upon in the book include McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

in "Usher II

Usher may refer to:

Several jobs which originally involved directing people and ensuring people are in the correct place:

* Usher (occupation)

** Church usher

** Wedding usher, one of the male attendants to the groom in a wedding ceremony

** Fiel ...

", racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and lynching in the United States

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings wer ...

in " Way in the Middle of the Air", and nuclear anxiety throughout. There are also several allusions to the European colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale European colonization of the Americas took place between about 1492 and 1800. Although the Norse had explored and colonized areas of the North Atlantic, colonizing Greenland and creating a short ter ...

: the first few missions to Mars in the book encounter Martians, with direct references to both Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquess of the Valley of Oaxaca (; ; 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions of w ...

and the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

, but the indigenous population soon goes extinct due to chickenpox

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a highly contagious disease caused by the initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV). The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab ...

in a parallel to the virgin soil epidemics that devastated Native American populations as a result of the Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World (the Americas) in ...

.

The majority of works about colonizing Mars nevertheless endeavoured to portray the challenges of doing so realistically. The hostile environment of the planet is countered by the colonists bringing life-support system

A life-support system is the combination of equipment that allows survival in an environment or situation that would not support that life in its absence. It is generally applied to systems supporting human life in situations where the outsid ...

s in works like the 1951 novel '' The Sands of Mars'' by Arthur C. Clarke

Sir Arthur Charles Clarke (16 December 191719 March 2008) was an English science-fiction writer, science writer, futurist, inventor, undersea explorer, and television series host.

He co-wrote the screenplay for the 1968 film '' 2001: A Spac ...

and the 1966 short story " We Can Remember It for You Wholesale" by Philip K. Dick

Philip Kindred Dick (December 16, 1928March 2, 1982), often referred to by his initials PKD, was an American science fiction writer. He wrote 44 novels and about 121 short stories, most of which appeared in science fiction magazines during his l ...

, while the early colonists during the centuries-long terraforming process in the 1953 short story " Crucifixus Etiam" by Walter M. Miller Jr.

Walter Michael Miller Jr. (January 23, 1923 – January 9, 1996) was an American science fiction writer. His fix-up novel, ''A Canticle for Leibowitz'' (1959), the only novel published in his lifetime, won the 1961 Hugo Award for Best Novel. ...

are dependent on a machine that oxygenates their blood from the thin atmosphere, and the scarcity of oxygen even after generations of terraforming forces the colonists to live in a domed city in the 1953 novel ''Police Your Planet

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and ...

'' by Lester del Rey. In the 1955 fix-up novel ''Alien Dust

Alien primarily refers to:

* Alien (law), a person in a country who is not a national of that country

** Enemy alien, the above in times of war

* Extraterrestrial life, life which does not originate from Earth

** Specifically, intelligent extrate ...

'' by Edwin Charles Tubb, colonists are unable to return to a life on Earth because inhaling the Martian dust has given them pneumoconiosis

Pneumoconiosis is the general term for a class of interstitial lung disease where inhalation of dust ( for example, ash dust, lead particles, pollen grains etc) has caused interstitial fibrosis. The three most common types are asbestosis, silicos ...

and the lower gravity has atrophied their muscles.

Mars colonies seeking independence from or outright revolting against Earth is a recurring motif; in del Rey's ''Police Your Planet'' a revolution is precipitated by Earth using unrest against the colony's corrupt mayor as a pretext for bringing Mars under firmer Terran control, and in Tubb's ''Alien Dust'' the colonists threaten Earth with nuclear weapons unless their demands for necessary resources are met. In the 1952 short story " The Martian Way" by Isaac Asimov

yi, יצחק אזימאװ

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Petrovichi, Russian SFSR

, spouse =

, relatives =

, children = 2

, death_date =

, death_place = Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

, nationality = Russian (1920–1922)Soviet (192 ...

, Martian colonists extract water from the rings of Saturn so as not to depend on importing water from Earth. Besides direct conflicts with Earth, Mars colonies get other kinds of unfavourable treatment in several works. Mars is a dilapidated colony and neglected in favour of locations outside of the Solar System in the 1967 novel '' Born Under Mars'' by John Brunner John Brunner may refer to: