Herbert Marshall McLuhan (July 21, 1911 – December 31, 1980) was a Canadian philosopher whose work is among the cornerstones of the study of

media theory

Media studies is a discipline and field of study that deals with the content, history, and effects of various media; in particular, the mass media. Media Studies may draw on traditions from both the social sciences and the humanities, but mostly ...

.

He studied at the

University of Manitoba

The University of Manitoba (U of M, UManitoba, or UM) is a Canadian public research university in the province of Manitoba.[University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...](_blank)

. He began his teaching career as a professor of English at several universities in the United States and Canada before moving to the

University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institu ...

in 1946, where he remained for the rest of his life.

McLuhan coined the expression "

the medium is the message

"The medium is the message" is a phrase coined by the Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan and the name of the first chapter in his '' Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man'', published in 1964.Originally published in 1964 by Men ...

" in the first chapter in his ''Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man'' and the term ''

global village

Global village describes the phenomenon of the entire world becoming more interconnected as the result of the propagation of media technologies throughout the world. The term was coined by Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan in his books ' ...

.'' He even predicted the

World Wide Web

The World Wide Web (WWW), commonly known as the Web, is an information system enabling documents and other web resources to be accessed over the Internet.

Documents and downloadable media are made available to the network through web se ...

almost 30 years before it was invented. He was a fixture in media discourse in the late 1960s, though his influence began to wane in the early 1970s. In the years following his death, he continued to be a controversial figure in academic circles.

However, with the arrival of the Internet and the World Wide Web, interest was renewed in his work and perspectives.

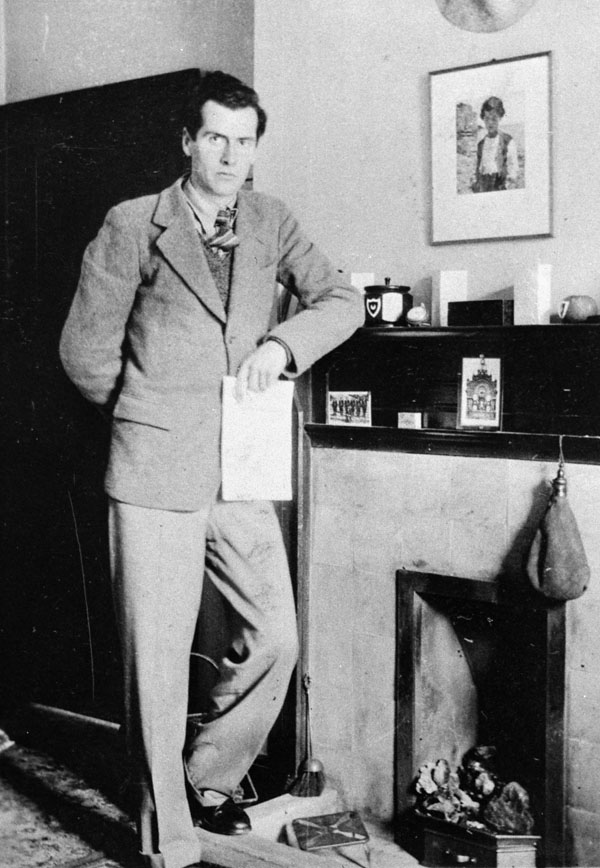

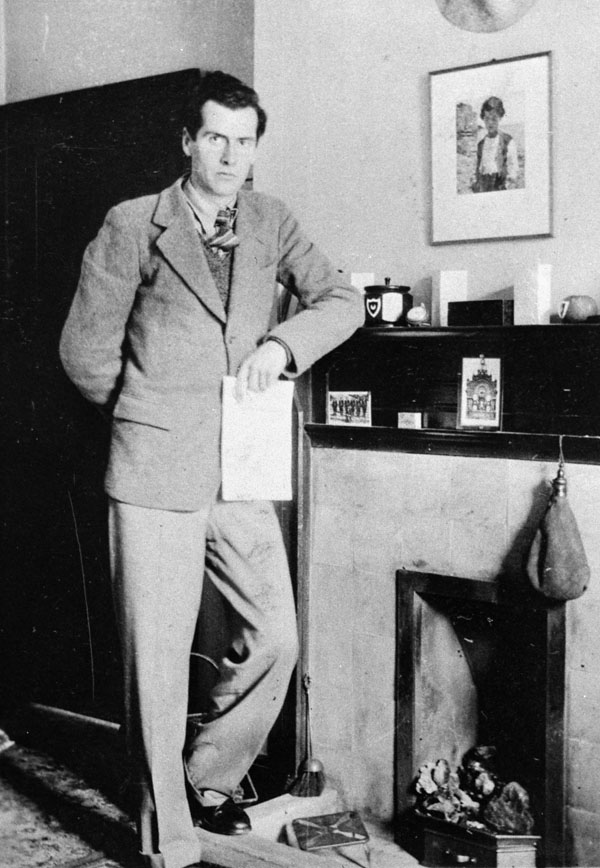

Life and career

McLuhan was born on July 21, 1911, in

Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city anc ...

, Alberta, and was named "Marshall" after his maternal grandmother's surname. His brother, Maurice, was born two years later. His parents were both also born in Canada: his mother, Elsie Naomi (née Hall), was a

Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christianity, Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe ...

school teacher who later became an actress; and his father, Herbert Ernest McLuhan, was a

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related Christian denomination, denominations of Protestantism, Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John W ...

with a real-estate business in Edmonton. When the business failed at the break out of

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, McLuhan's father enlisted in the

Canadian Army

The Canadian Army (french: Armée canadienne) is the command (military formation), command responsible for the operational readiness of the conventional ground forces of the Canadian Armed Forces. It maintains regular forces units at bases acr ...

. After a year of service, he contracted

influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

and remained in Canada, away from the front lines. After Herbert's discharge from the army in 1915, the McLuhan family moved to

Winnipeg

Winnipeg () is the capital and largest city of the province of Manitoba in Canada. It is centred on the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, near the longitudinal centre of North America. , Winnipeg had a city population of 749 ...

, Manitoba, where Marshall grew up and went to school, attending

Kelvin Technical School before enrolling in the

University of Manitoba

The University of Manitoba (U of M, UManitoba, or UM) is a Canadian public research university in the province of Manitoba.[University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...](_blank)

, having failed to secure a

Rhodes scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship is an international postgraduate award for students to study at the University of Oxford, in the United Kingdom.

Established in 1902, it is the oldest graduate scholarship in the world. It is considered among the world ...

to

Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the Un ...

.

Though having already earned his B.A. and M.A. in Manitoba, Cambridge required him to enroll as an undergraduate "affiliated" student, with one year's credit towards a three-year

bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

, before entering any

doctoral studies

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is a ...

. He entered

Trinity Hall, Cambridge

Trinity Hall (formally The College or Hall of the Holy Trinity in the University of Cambridge) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

It is the fifth-oldest surviving college of the university, having been founded in 1350 by ...

, in the autumn of 1934, where he studied under

I. A. Richards and

F. R. Leavis, and was influenced by

New Criticism

New Criticism was a formalist movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of literature functioned ...

.

[Marchand, pp. 33–34] Years afterward, upon reflection, he credited the faculty there with influencing the direction of his later work because of their emphasis on the "training of perception", as well as such concepts as Richards' notion of "

feedforward

Feedforward is the provision of context of what one wants to communicate prior to that communication. In purposeful activity, feedforward creates an expectation which the actor anticipates. When expected experience occurs, this provides confirmato ...

". These studies formed an important precursor to his later ideas on technological forms.

[Old Messengers, New Media: The Legacy of Innis and McLuhan]

" '' Collections Canada''. Government of Canada

The government of Canada (french: gouvernement du Canada) is the body responsible for the federal administration of Canada. A constitutional monarchy, the Crown is the corporation sole, assuming distinct roles: the executive, as the ''Crown-i ...

. 998

Year 998 ( CMXCVIII) was a common year starting on Saturday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* Spring – Otto III retakes Rome and restores power in the papal city. Crescent ...

2008. Archived from th

original

on 1 December 2019. He received the required bachelor's degree from Cambridge in 1936 and entered their graduate program.

Conversion to Catholicism

At the University of Manitoba, McLuhan explored his conflicted relationship with religion and turned to literature to "gratify his soul's hunger for truth and beauty," later referring to this stage as agnosticism. While studying the

trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ''De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii'' ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but t ...

at Cambridge, he took the first steps toward his eventual conversion to

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in 1937, founded on his reading of

G. K. Chesterton. In 1935, he wrote to his mother:

Had I not encountered Chesterton I would have remained agnostic for many years at least. Chesterton did not convince me of religious faith, but he prevented my despair from becoming a habit or hardening into misanthropy. He opened my eyes to European culture and encouraged me to know it more closely. He taught me the reasons for all that in me was simply blind anger and misery.

At the end of March 1937, McLuhan completed what was a slow but total conversion process, when he was formally received into the

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. After consulting a minister, his father accepted the decision to convert. His mother, however, felt that his conversion would hurt his career and was inconsolable. McLuhan was devout throughout his life, but his religion remained a private matter. He had a lifelong interest in the number three (e.g., the trivium, the

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

) and sometimes said that the

Virgin Mary

Mary; arc, ܡܪܝܡ, translit=Mariam; ar, مريم, translit=Maryam; grc, Μαρία, translit=María; la, Maria; cop, Ⲙⲁⲣⲓⲁ, translit=Maria was a first-century Jews, Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Jose ...

provided intellectual guidance for him. For the rest of his career, he taught in Catholic institutions of higher education.

Early career, marriage, and doctorate

Unable to find a suitable job in Canada, he returned from England to take a job as a teaching assistant at the

University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. ''University'' is derived from the Latin phrase ''universitas magistrorum et scholarium'', which ...

for the 1936–37 academic year. From 1937 to 1944, he taught English at

Saint Louis University

Saint Louis University (SLU) is a private Jesuit research university with campuses in St. Louis, Missouri, United States, and Madrid, Spain. Founded in 1818 by Louis William Valentine DuBourg, it is the oldest university west of the Mississip ...

(with an interruption from 1939 to 1940 when he returned to Cambridge). There he taught courses on

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, eventually tutoring and befriending

Walter J. Ong, who would write his doctoral dissertation on a topic that McLuhan had called to his attention, as well as become a well-known authority on communication and technology.

McLuhan met Corinne Lewis in St. Louis, a teacher and aspiring actress from

Fort Worth, Texas, whom he married on August 4, 1939. They spent 1939–40 in Cambridge, where he completed his master's degree (awarded in January 1940) and began to work on his doctoral dissertation on

Thomas Nashe

Thomas Nashe (baptised November 1567 – c. 1601; also Nash) was an Elizabethan playwright, poet, satirist and a significant pamphleteer. He is known for his novel '' The Unfortunate Traveller'', his pamphlets including ''Pierce Penniless,' ...

and the verbal arts. While the McLuhans were in England,

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

had broken out in Europe. For this reason, he obtained permission to complete and submit his dissertation from the United States, without having to return to Cambridge for an oral defence. In 1940, the McLuhans returned to Saint Louis University, where they started a family as he continued teaching. He was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy degree in December 1943.

He next taught at

Assumption College Assumption College may refer to these educational institutions:

Australia

* Assumption College, Kilmore, Victoria

* Assumption College, Warwick, Queensland

Canada

* Assumption University (Windsor, Ontario) (formerly Assumption College)

* Assumpt ...

in

Windsor, Ontario, from 1944 to 1946, then moved to

Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most pop ...

in 1946 where he joined the faculty of

St. Michael's College, a Catholic college of the

University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public research university in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park. It was founded by royal charter in 1827 as King's College, the first institu ...

, where

Hugh Kenner

William Hugh Kenner (January 7, 1923 – November 24, 2003) was a Canadian literary scholar, critic and professor. He published widely on Modernist literature with particular emphasis on James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and Samuel Beckett. His major ...

would be one of his students. Canadian economist and communications scholar

Harold Innis

Harold Adams Innis (November 5, 1894 – November 9, 1952) was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory, and economic history of Canada, Canadian econo ...

was a university colleague who had a strong influence on his work. McLuhan wrote in 1964: "I am pleased to think of my own book ''

The Gutenberg Galaxy

''The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man'' is a 1962 book by Marshall McLuhan, in which the author analyzes the effects of mass media, especially the printing press, on European culture and human consciousness. It popularized the te ...

'' as a footnote to the observations of Innis on the subject of the psychic and social consequences, first of writing then of printing."

Later career and reputation

In the early 1950s, McLuhan began the Communication and Culture seminars at the University of Toronto, funded by the

Ford Foundation

The Ford Foundation is an American private foundation with the stated goal of advancing human welfare. Created in 1936 by Edsel Ford and his father Henry Ford, it was originally funded by a US$25,000 gift from Edsel Ford. By 1947, after the dea ...

. As his reputation grew, he received a growing number of offers from other universities.

During this period, he published his first major work, ''

The Mechanical Bride'' (1951), in which he examines the effect of advertising on society and culture. Throughout the 1950s, he and

Edmund Carpenter also produced an important academic journal called ''

Explorations''. McLuhan and Carpenter have been characterized as the

Toronto School of communication theory The Toronto School is a school of thought in communication theory and literary criticism, the principles of which were developed chiefly by scholars at the University of Toronto. It is characterized by exploration of Ancient Greek literature and t ...

, together with

Harold Innis

Harold Adams Innis (November 5, 1894 – November 9, 1952) was a Canadian professor of political economy at the University of Toronto and the author of seminal works on media, communication theory, and economic history of Canada, Canadian econo ...

,

Eric A. Havelock, and

Northrop Frye

Herman Northrop Frye (July 14, 1912 – January 23, 1991) was a Canadian literary critic and literary theorist, considered one of the most influential of the 20th century.

Frye gained international fame with his first book, '' Fearful Symm ...

. During this time, McLuhan supervised the doctoral thesis of

modernist writer Sheila Watson on the subject of

Wyndham Lewis

Percy Wyndham Lewis (18 November 1882 – 7 March 1957) was a British writer, painter and critic. He was a co-founder of the Vorticist movement in art and edited '' BLAST,'' the literary magazine of the Vorticists.

His novels include '' Tarr'' ...

. Hoping to keep him from moving to another institute, the University of Toronto created the

Centre for Culture and Technology (CCT) in 1963.

From 1967 to 1968, McLuhan was named the

Albert Schweitzer

Ludwig Philipp Albert Schweitzer (; 14 January 1875 – 4 September 1965) was an Alsatian-German/French polymath. He was a theologian, organist, musicologist, writer, humanitarian, philosopher, and physician. A Lutheran minister, Schwei ...

Chair in Humanities at

Fordham University

Fordham University () is a Private university, private Jesuit universities, Jesuit research university in New York City. Established in 1841 and named after the Fordham, Bronx, Fordham neighborhood of the The Bronx, Bronx in which its origina ...

in the Bronx. While at Fordham, he was diagnosed with a

benign

Malignancy () is the tendency of a medical condition to become progressively worse.

Malignancy is most familiar as a characterization of cancer. A ''malignant'' tumor contrasts with a non-cancerous ''benign'' tumor in that a malignancy is not s ...

brain tumor

A brain tumor occurs when abnormal cells form within the brain. There are two main types of tumors: malignant tumors and benign (non-cancerous) tumors. These can be further classified as primary tumors, which start within the brain, and secon ...

, which was treated successfully. He returned to Toronto where he taught at the University of Toronto for the rest of his life and lived in

Wychwood Park

Wychwood Park is a neighbourhood enclave and private community in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is located west of Bathurst Street on the north side of Davenport Road, within the larger area of Bracondale Hill. It is considered part of the overal ...

, a bucolic enclave on a hill overlooking the

downtown

''Downtown'' is a term primarily used in North America by English speakers to refer to a city's sometimes commercial, cultural and often the historical, political and geographic heart. It is often synonymous with its central business distric ...

where

Anatol Rapoport

Anatol Rapoport ( uk, Анатолій Борисович Рапопо́рт; russian: Анато́лий Бори́сович Рапопо́рт; May 22, 1911January 20, 2007) was an American mathematical psychologist. He contributed to genera ...

was his neighbour.

In 1970, he was made a Companion of the

Order of Canada

The Order of Canada (french: Ordre du Canada; abbreviated as OC) is a Canadian state order and the second-highest honour for merit in the system of orders, decorations, and medals of Canada, after the Order of Merit.

To coincide with the c ...

. In 1975, the

University of Dallas

The University of Dallas is a private Catholic university in Irving, Texas. Established in 1956, it is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

The university comprises four academic units: the Braniff Graduate School ...

hosted him from April to May, appointing him to the McDermott Chair. Marshall and Corinne McLuhan had six children:

Eric

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, or Eirik is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-Norse ''* a ...

, twins Mary and Teresa, Stephanie, Elizabeth, and Michael. The associated costs of a large family eventually drove him to advertising work and accepting frequent consulting and speaking engagements for large corporations, including

IBM and

AT&T

AT&T Inc. is an American multinational telecommunications holding company headquartered at Whitacre Tower in Downtown Dallas, Texas. It is the world's largest telecommunications company by revenue and the third largest provider of mobile tel ...

.

Woody Allen

Heywood "Woody" Allen (born Allan Stewart Konigsberg; November 30, 1935) is an American film director, writer, actor, and comedian whose career spans more than six decades and multiple Academy Award-winning films. He began his career writing ...

's Oscar-winning ''

Annie Hall

''Annie Hall'' is a 1977 American Satire (film and television), satirical Romance film, romantic comedy-drama film directed by Woody Allen from a screenplay written by him and Marshall Brickman, and produced by Allen's manager, Charles H. Joff ...

'' (1977) featured McLuhan in a

cameo as himself. In the film, a pompous academic is arguing with Allen in a cinema queue when McLuhan suddenly appears and silences him, saying, "You know nothing of my work." This was one of McLuhan's most frequent statements to and about those who disagreed with him.

Death

In September 1979, McLuhan suffered a stroke which affected his ability to speak. The University of Toronto's School of Graduate Studies tried to close his research centre shortly thereafter, but was deterred by substantial protests. McLuhan never fully recovered from the stroke and died in his sleep on December 31, 1980.

He is buried at Holy Cross Cemetery in

Thornhill, Ontario, Canada.

Major works

During his years at Saint Louis University (1937–1944), McLuhan worked concurrently on two projects: his doctoral

dissertation and the manuscript that was eventually published in 1951 as a book, titled ''

The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man'', which included only a representative selection of the materials that McLuhan had prepared for it.

McLuhan's 1942 Cambridge University doctoral dissertation surveys the history of the verbal arts (

grammar

In linguistics, the grammar of a natural language is its set of structure, structural constraints on speakers' or writers' composition of clause (linguistics), clauses, phrases, and words. The term can also refer to the study of such constraint ...

,

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

, and

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

—collectively known as the

trivium

The trivium is the lower division of the seven liberal arts and comprises grammar, logic, and rhetoric.

The trivium is implicit in ''De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii'' ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury") by Martianus Capella, but t ...

) from the time of

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

down to the time of Thomas Nashe. In his later publications, McLuhan at times uses the Latin concept of the ''trivium'' to outline an orderly and systematic picture of certain periods in the history of

Western culture

image:Da Vinci Vitruve Luc Viatour.jpg, Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions, human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise '' ...

. McLuhan suggests that the

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Ren ...

, for instance, were characterized by the heavy emphasis on the formal study of logic. The key development that led to the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

was not the rediscovery of ancient texts, but a shift in emphasis from the formal study of logic to rhetoric and grammar.

Modern life

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the " Age of Rea ...

is characterized by the re-emergence of grammar as its most salient feature—a trend McLuhan felt was exemplified by the

New Criticism

New Criticism was a formalist movement in literary theory that dominated American literary criticism in the middle decades of the 20th century. It emphasized close reading, particularly of poetry, to discover how a work of literature functioned ...

of Richards and Leavis.

McLuhan also began the

academic journal

An academic journal or scholarly journal is a periodical publication in which scholarship relating to a particular academic discipline is published. Academic journals serve as permanent and transparent forums for the presentation, scrutiny, and ...

''Explorations'' with

anthropologist Edmund "Ted" Carpenter. In a letter to Walter Ong, dated 31 May 1953, McLuhan reports that he had received a two-year

grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

* Castle Grant

United States

*Grant, Alabama

* Grant, Inyo County, ...

of $43,000 from the Ford Foundation to carry out a communication project at the University of Toronto involving faculty from different disciplines, which led to the creation of the journal.

At a Fordham lecture in 1999,

Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

suggested that a major under-acknowledged influence on McLuhan's work is the

Jesuit philosopher

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin ( (); 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French Jesuit priest, scientist, paleontologist, theologian, philosopher and teacher. He was Darwinian in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philo ...

, whose ideas anticipated those of McLuhan, especially the evolution of the human mind into the "

noosphere

The noosphere (alternate spelling noösphere) is a philosophical concept developed and popularized by the Russian-Ukrainian Soviet biogeochemist Vladimir Vernadsky, and the French philosopher and Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Vernad ...

."

In fact, McLuhan warns against outright dismissing or whole-heartedly accepting de Chardin's observations early on in his second published book ''The Gutenberg Galaxy'':

In his private life, McLuhan wrote to friends saying: "I am not a fan of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. The idea that anything is better because it comes later is surely borrowed from pre-electronic technologies." Further, McLuhan noted to a Catholic collaborator: "The idea of a Cosmic thrust in one direction ... is surely one of the lamest semantic fallacies ever bred by the word 'evolution'.… That development should have any direction at all is inconceivable except to the highly literate community."

Some of McLuhan's main ideas were influenced or prefigured by anthropologist like

Edward Sapir

Edward Sapir (; January 26, 1884 – February 4, 1939) was an American Jewish anthropologist- linguist, who is widely considered to be one of the most important figures in the development of the discipline of linguistics in the United States.

Sa ...

and

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Claude Lévi-Strauss (, ; 28 November 1908 – 30 October 2009) was a French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He held the chair of Social Anthro ...

, arguably with a more complex historical and psychological analysis.

The idea of the retribalization of Western society by the far-reaching techniques of communication, the view on the function of the artist in society, and the characterization of means of transportation, like the railroad and the airplane, as means of communication, are prefigured in Sapir's 1933 article on ''Communication'' in the

Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences

The ''Encyclopaedia of the Social Sciences'' is a specialized fifteen-volume Encyclopedia first published in 1930 and last published in 1967. It was envisaged in the 1920s by scholars working in disciplines which increasingly were coming to be know ...

, while the distinction between "hot" and "cool" media draws from Lévi-Strauss' distinction between hot and cold societies.

[Claude Lévi-Strauss (1962) '']The Savage Mind

''The Savage Mind'' (french: La Pensée sauvage), also translated as ''Wild Thought'', is a 1962 work of structural anthropology by the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Summary

"The Savage Mind"

Lévi-Strauss makes clear that "''la pen ...

'', ch.8[Taunton, Matthew (2019) ]

Red Britain: The Russian Revolution in Mid-Century Culture

', p.223

''The Mechanical Bride'' (1951)

McLuhan's first book, ''

The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man'' (1951), is a pioneering study in the field now known as popular culture. In the book, McLuhan turns his attention to analysing and commenting on numerous examples of persuasion in contemporary popular culture. This followed naturally from his earlier work as both

dialectic

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different points of view about a subject but wishing to ...

and rhetoric in the classical trivium aimed at

persuasion

Persuasion or persuasion arts is an umbrella term for Social influence, influence. Persuasion can influence a person's Belief, beliefs, Attitude (psychology), attitudes, Intention, intentions, Motivation, motivations, or Behavior, behaviours.

...

. At this point, his focus shifted dramatically, turning inward to study the influence of

communication media

In mass communication, media are the communication outlets or tools used to store and deliver information or data. The term refers to components of the mass media communications industry, such as print media, publishing, the news media, photograp ...

independent of their content. His famous

aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by t ...

"

the medium is the message

"The medium is the message" is a phrase coined by the Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan and the name of the first chapter in his '' Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man'', published in 1964.Originally published in 1964 by Men ...

" (elaborated in his ''

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man'', 1964) calls attention to this intrinsic effect of communications media.

His interest in the critical study of popular culture was influenced by the 1933 book ''Culture and Environment'' by

F. R. Leavis and

Denys Thompson, and the title ''The Mechanical Bride'' is derived from a piece by the

Dada

Dada () or Dadaism was an art movement of the European avant-garde in the early 20th century, with early centres in Zürich, Switzerland, at the Cabaret Voltaire (Zurich), Cabaret Voltaire (in 1916). New York Dada began c. 1915, and after 192 ...

ist artist

Marcel Duchamp

Henri-Robert-Marcel Duchamp (, , ; 28 July 1887 – 2 October 1968) was a French painter, sculptor, chess player, and writer whose work is associated with Cubism, Dada, and conceptual art. Duchamp is commonly regarded, along with Pablo Picasso ...

.

Like his later ''The Gutenberg Galaxy'' (1962), ''The Mechanical Bride'' is composed of a number of short essays that may be read in any order—what he styled the "

mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

approach" to writing a book. Each essay begins with a newspaper or magazine article, or an advertisement, followed by McLuhan's analysis thereof. The analyses bear on

aesthetic

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed t ...

considerations as well as on the implications behind the imagery and text. McLuhan chose these ads and articles not only to draw attention to their

symbolism

Symbolism or symbolist may refer to:

Arts

* Symbolism (arts), a 19th-century movement rejecting Realism

** Symbolist movement in Romania, symbolist literature and visual arts in Romania during the late 19th and early 20th centuries

** Russian sym ...

, as well as their implications for the

corporate entities who created and disseminated them, but also to mull over what such advertising implies about the wider society at which it is aimed. Roland Barthes's essays 1957 ''

Mythologies

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of Narrative, narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or Origin myth, origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not Objectivity (philosophy), ...

'', echoes McLuhan's ''Mechanical Bride'', as a series of exhibits of popular mass culture (like advertisements, newspaper articles and photographs) that are analyzed in a

semiological way.

''The Gutenberg Galaxy'' (1962)

Written in 1961 and first published by

University of Toronto Press

The University of Toronto Press is a Canadian university press founded in 1901. Although it was founded in 1901, the press did not actually publish any books until 1911.

The press originally printed only examination books and the university cale ...

, ''

The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man'' (1962) is a pioneering study in the fields of

oral culture

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985) ...

,

print culture

Print culture embodies all forms of printed text and other printed forms of visual communication. One prominent scholar of print culture in Europe is Elizabeth Eisenstein, who contrasted the print culture of Europe in the centuries after the adv ...

,

cultural studies, and

media ecology

Media ecology theory is the study of media, technology, and communication and how they affect human environments. The theoretical concepts were proposed by Marshall McLuhan in 1964, while the term ''media ecology'' was first formally introduced b ...

.

Throughout the book, McLuhan efforts to reveal how

communication technology

Telecommunication is the transmission of information by various types of technologies over wire, radio, optical, or other electromagnetic systems. It has its origin in the desire of humans for communication over a distance greater than that fe ...

(i.e.,

alphabetic writing

An alphabet is a standardized set of basic written graphemes (called letters) that represent the phonemes of certain spoken languages. Not all writing systems represent language in this way; in a syllabary, each character represents a syll ...

, the

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

, and the

electronic media

Electronic media are media that use electronics or electromechanical means for the audience to access the content. This is in contrast to static media (mainly print media), which today are most often created digitally, but do not requir ...

) affects

cognitive

Cognition refers to "the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and processes such as: perception, attention, thought ...

organization, which in turn has profound ramifications for social organization:

a new technology extends one or more of our senses outside us into the social world, then new ratios among all of our senses will occur in that particular culture. It is comparable to what happens when a new note is added to a melody. And when the sense ratios alter in any culture then what had appeared lucid before may suddenly become opaque, and what had been vague or opaque will become translucent.

Movable type

McLuhan's episodic history takes the reader from pre-alphabetic,

tribal

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confli ...

humankind to the

electronic age. According to McLuhan, the invention of

movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuatio ...

greatly accelerated, intensified, and ultimately enabled cultural and cognitive changes that had already been taking place since the invention and implementation of the alphabet, by which McLuhan means

phonemic orthography

A phonemic orthography is an orthography (system for writing a language) in which the graphemes (written symbols) correspond to the phonemes (significant spoken sounds) of the language. Natural languages rarely have perfectly phonemic orthographi ...

. (McLuhan is careful to distinguish the phonetic alphabet from

logographic

In a written language, a logogram, logograph, or lexigraph is a written character that represents a word or morpheme. Chinese characters (pronounced '' hanzi'' in Mandarin, ''kanji'' in Japanese, ''hanja'' in Korean) are generally logograms, ...

or logogramic writing systems, such as

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (, ) were the formal writing system used in Ancient Egypt, used for writing the Egyptian language. Hieroglyphs combined logographic, syllabic and alphabetic elements, with some 1,000 distinct characters.There were about 1, ...

or

ideograms

An ideogram or ideograph (from Greek "idea" and "to write") is a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept, independent of any particular language, and specific words or phrases. Some ideograms are comprehensible only by familiarit ...

.)

Print culture, ushered in by the advance in printing during the middle of the 15th century when the

Gutenberg press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the c ...

was invented, brought about the cultural predominance of the visual over the aural/oral. Quoting (with approval) an observation on the nature of the printed word from

William Ivins

William Mills Ivins Jr. (1881–1961) was curator of the department of prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from its founding in 1916 until 1946, when he was succeeded by A. Hyatt Mayor.

The son of William Mills Ivins Sr. ( ...

' ''Prints and Visual Communication'', McLuhan remarks:

In this passage vins

Georgi Petrovich Vins (russian: Георгий Петрович Винс; August 4, 1928 Blagoveshchensk, Russian SFSR – January 11, 1998 Elkhart, Indiana) was a Russian Baptist pastor persecuted by the Soviet authorities for his involvement in ...

not only notes the ingraining of lineal, sequential habits, but, even more important, points out the visual homogenizing of experience of print culture, and the relegation of auditory and other sensuous complexity to the background.…The technology and social effects of typography incline us to abstain from noting interplay and, as it were, "formal" causality, both in our inner and external lives. Print exists by virtue of the static separation of functions and fosters a mentality that gradually resists any but a separative and compartmentalizing or specialist outlook.

The main concept of McLuhan's argument (later elaborated upon in ''

The Medium Is the Massage

''The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects'' is a book co-created by media analyst Marshall McLuhan and graphic designer Quentin Fiore, with coordination by Jerome Agel. It was published by Bantam Books in 1967 and became a bestsel ...

'') is that new technologies (such as alphabets, printing presses, and even speech) exert a gravitational effect on cognition, which in turn, affects

social organization

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and social groups.

Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership ...

: print technology changes our perceptual habits—"visual

homogenizing

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the uniformity of a substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in composition or character (i.e. color, shape, si ...

of experience"—which in turn affects social interactions—"fosters a mentality that gradually resists all but a…specialist outlook". According to McLuhan, this advance of print technology contributed to and made possible most of the salient trends in the modern period in the Western world:

individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-relia ...

, democracy,

Protestantism

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

,

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

, and

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

. For McLuhan, these trends all reverberate with print technology's principle of "segmentation of actions and functions and principle of visual

quantification."

Global village

In the early 1960s, McLuhan wrote that the visual, individualistic print culture would soon be brought to an end by what he called "electronic

interdependence

Systems theory is the interdisciplinary study of systems, i.e. cohesive groups of interrelated, interdependent components that can be natural or human-made. Every system has causal boundaries, is influenced by its context, defined by its structu ...

" wherein electronic media replaces visual culture with aural/oral culture. In this new age, humankind would move from individualism and fragmentation to a

collective identity

Collective identity is the shared sense of belonging to a group.

In sociology

In 1989, Alberto Melucci published ''Nomads of the Present'', which introduces his model of collective identity based on studies of the social movements of the 1980 ...

, with a "tribal base." McLuhan's coinage for this new social organization is the ''

global village

Global village describes the phenomenon of the entire world becoming more interconnected as the result of the propagation of media technologies throughout the world. The term was coined by Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan in his books ' ...

''.

The term is sometimes described as having negative connotations in ''The Gutenberg Galaxy'', but McLuhan was interested in exploring effects, not making

value judgment

A value judgment (or value judgement) is a judgment of the rightness or wrongness of something or someone, or of the usefulness of something or someone, based on a comparison or other relativity. As a generalization, a value judgment can refer t ...

s:

Instead of tending towards a vast Alexandrian library

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. The Library was part of a larger research institution called the Mouseion, which was dedicated to the Muses, th ...

the world has become a computer, an electronic brain, exactly as an infantile piece of science fiction. And as our senses have gone outside us, Big Brother goes inside. So, unless aware of this dynamic, we shall at once move into a phase of panic terrors, exactly befitting a small world of tribal drums, total interdependence, and superimposed co-existence.… Terror is the normal state of any oral society, for in it everything affects everything all the time.…In our long striving to recover for the Western world a unity of sensibility and of thought and feeling we have no more been prepared to accept the tribal consequences of such unity than we were ready for the fragmentation of the human psyche by print culture.

Key to McLuhan's argument is the idea that technology has no ''per se'' moral bent—it is a tool that profoundly shapes an individual's and, by extension, a society's

self-conception and

realization:

Is it not obvious that there are always enough moral problems without also taking a moral stand on technological grounds?…Print is the extreme phase of alphabet culture that detribalizes or decollectivizes man in the first instance. Print raises the visual features of alphabet to highest intensity of definition. Thus, print carries the individuating power of the phonetic alphabet much further than manuscript culture could ever do. Print is the technology of individualism. If men decided to modify this

visual technology

Visual technology is the engineering discipline dealing with visual representation.

Types

Visual technology includes photography, printing, augmented reality, virtual reality and video.

See also

*Audiovisual

* Audiovisual education

*Informati ...

by an electric technology, individualism would also be modified. To raise a moral complaint about this is like cussing a buzz-saw for lopping off fingers. "But", someone says, "we didn't know it would happen." Yet even witlessness is not a moral issue. It is a problem, but not a moral problem; and it would be nice to clear away some of the moral fogs that surround our technologies. It would be good for morality.

The moral

valence

Valence or valency may refer to:

Science

* Valence (chemistry), a measure of an element's combining power with other atoms

* Degree (graph theory), also called the valency of a vertex in graph theory

* Valency (linguistics), aspect of verbs rel ...

of technology's effects on cognition is, for McLuhan, a matter of perspective. For instance, McLuhan contrasts the considerable alarm and revulsion that the growing quantity of books aroused in the latter 17th century with the modern concern for the "end of the book." If there can be no universal moral sentence passed on technology, McLuhan believes that "there can only be disaster arising from unawareness of the

causalities and effects inherent in our technologies".

Though the World Wide Web was invented almost 30 years after ''The Gutenberg Galaxy'', and 10 years after his death, McLuhan prophesied the web technology seen today as early as 1962:

The next medium, whatever it is—it may be the extension of consciousness—will include television as its content, not as its environment, and will transform television into an art form. A computer as a research and communication instrument could enhance retrieval, obsolesce mass library organization, retrieve the individual's encyclopedic function and flip into a private line to speedily tailored data of a saleable kind.

Furthermore, McLuhan coined and certainly popularized the usage of the term ''

surfing'' to refer to rapid, irregular, and multidirectional movement through a heterogeneous body of documents or knowledge, e.g., statements such as "

Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centu ...

surf-boards along on the electronic wave as triumphantly as

Descartes rode the mechanical wave."

Paul Levinson's 1999 book ''Digital McLuhan'' explores the ways that McLuhan's work may be understood better through using the lens of the digital revolution.

McLuhan frequently quoted Walter Ong's ''Ramus, Method, and the Decay of Dialogue'' (1958), which evidently had prompted McLuhan to write ''The Gutenberg Galaxy''. Ong wrote a highly favorable review of this new book in ''America''. However, Ong later tempered his praise, by describing McLuhan's ''The Gutenberg Galaxy'' as "a racy survey, indifferent to some scholarly detail, but uniquely valuable in suggesting the sweep and depth of the cultural and psychological changes entailed in the passage from illiteracy to print and beyond." McLuhan himself said of the book, "I'm not concerned to get any kudos out of

'The Gutenberg Galaxy'' It seems to me a book that somebody should have written a century ago. I wish somebody else had written it. It will be a useful prelude to the rewrite of ''Understanding Media''

he 1960 NAEB report

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

that I'm doing now."

McLuhan's ''The Gutenberg Galaxy'' won Canada's highest literary award, the

Governor-General's Award for Non-Fiction, in 1962. The chairman of the selection committee was McLuhan's colleague at the University of Toronto and oftentime intellectual sparring partner,

Northrop Frye

Herman Northrop Frye (July 14, 1912 – January 23, 1991) was a Canadian literary critic and literary theorist, considered one of the most influential of the 20th century.

Frye gained international fame with his first book, '' Fearful Symm ...

.

''Understanding Media'' (1964)

McLuhan's most widely-known work, ''

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man'' (1964), is a seminal study in media theory. Dismayed by the way in which people approach and use new media such as television, McLuhan famously argues that in the modern world "we live mythically and integrally…but continue to think in the old, fragmented space and time patterns of the pre-electric age."

McLuhan proposed that media themselves, not the content they carry, should be the focus of study—popularly quoted as "the medium is the message." McLuhan's insight was that a medium affects the society in which it plays a role not by the content delivered over the medium, but by the characteristics of the medium itself. McLuhan pointed to the light bulb as a clear demonstration of this concept. A light bulb does not have content in the way that a newspaper has articles, or a television has programs, yet it is a medium that has a social effect; that is, a light bulb enables people to create spaces during nighttime that would otherwise be enveloped by darkness. He describes the light bulb as a medium without any content. McLuhan states that "a light bulb creates an environment by its mere presence." More controversially, he postulated that content had little effect on society—in other words, it did not matter if television broadcasts children's shows or violent programming, to illustrate one example—the effect of television on society would be identical. He noted that all media have characteristics that engage the viewer in different ways; for instance, a passage in a book could be reread at will, but a movie had to be screened again in its entirety to study any individual part of it.

"Hot" and "cool" media

In the first part of ''Understanding Media'', McLuhan states that different media invite different degrees of participation on the part of a person who chooses to consume a medium. Using a terminology derived from French anthropologist Lévi-Strauss' distinction between hot and cold societies,

McLuhan argues that a cool medium requires increased involvement due to decreased description, while a hot medium is the opposite, decreasing involvement and increasing description. In other words, a society that appears to be actively participating in the streaming of content but not considering the effects of the tool is not allowing an "extension of ourselves." A movie is thus said to be "high definition," demanding a viewer's attention, while a comic book to be "low definition," requiring much more conscious participation by the reader to extract value: "Any hot medium allows of less participation than a cool one, as a lecture makes for less participation than a seminar, and a book for less than a dialogue."

Some media, such as movies, are ''hot''—that is, they enhance one single sense, in this case vision, in such a manner that a person does not need to exert much effort to perceive a detailed moving image. Hot media usually, but not always, provide complete involvement with considerable

stimulus. In contrast, "cool" print may also occupy

visual space

Visual space is the experience of space by an aware observer. It is the subjective counterpart of the space of physical objects. There is a long history in philosophy, and later psychology of writings describing visual space, and its relationshi ...

, using

visual senses, but requires focus and comprehension to immerse its reader. Hot media creation favour

analytical precision,

quantitative analysis

Quantitative analysis may refer to:

* Quantitative research, application of mathematics and statistics in economics and marketing

* Quantitative analysis (chemistry), the determination of the absolute or relative abundance of one or more substanc ...

and sequential ordering, as they are usually sequential,

linear

Linearity is the property of a mathematical relationship ('' function'') that can be graphically represented as a straight line. Linearity is closely related to '' proportionality''. Examples in physics include rectilinear motion, the linear ...

, and logical. They emphasize one sense (for example, of sight or sound) over the others. For this reason, hot media also include film (especially

silent film

A silent film is a film with no synchronized Sound recording and reproduction, recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) ...

s), radio, the lecture, and photography.

McLuhan contrasts ''hot'' media with ''cool''—specifically, television

f the 1960s i.e. small black-and-white screens which he claims requires more effort on the part of the viewer to determine meaning; and comics, which, due to their minimal presentation of visual detail, require a high degree of effort to fill in details that the cartoonist may have intended to portray. Cool media are usually, but not always, those that provide little involvement with substantial stimulus. They require more active participation on the part of the user, including the perception of

abstract

Abstract may refer to:

* ''Abstract'' (album), 1962 album by Joe Harriott

* Abstract of title a summary of the documents affecting title to parcel of land

* Abstract (law), a summary of a legal document

* Abstract (summary), in academic publishi ...

patterning and simultaneous comprehension of all parts. Therefore, in addition to television, cool media include the

seminar

A seminar is a form of academic instruction, either at an academic institution or offered by a commercial or professional organization. It has the function of bringing together small groups for recurring meetings, focusing each time on some parti ...

and cartoons. McLuhan describes the term ''cool media'' as emerging from jazz and popular music used, in this context, to mean "detached."

This concept appears to force media into binary categories. However, McLuhan's hot and cool exist on a continuum: they are more correctly measured on a scale than as

dichotomous

A dichotomy is a partition of a whole (or a set) into two parts (subsets). In other words, this couple of parts must be

* jointly exhaustive: everything must belong to one part or the other, and

* mutually exclusive: nothing can belong simul ...

terms.

Critiques of ''Understanding Media''

Some theorists have attacked McLuhan's definition and treatment of the word "

medium

Medium may refer to:

Science and technology

Aviation

*Medium bomber, a class of war plane

* Tecma Medium, a French hang glider design

Communication

* Media (communication), tools used to store and deliver information or data

* Medium of ...

" for being too simplistic.

Umberto Eco

Umberto Eco (5 January 1932 – 19 February 2016) was an Italian medievalist, philosopher, semiotician, novelist, cultural critic, and political and social commentator. In English, he is best known for his popular 1980 novel '' The Name of th ...

, for instance, contends that McLuhan's medium conflates channels,

codes, and messages under the overarching term of the medium, confusing the vehicle,

internal code, and content of a given message in his framework.

In ''Media Manifestos'',

Régis Debray

Jules Régis Debray (; born 2 September 1940) is a French philosopher, journalist, former government official and academic. He is known for his theorization of mediology, a critical theory of the long-term transmission of cultural meaning in ...

also takes issue with McLuhan's envisioning of the medium. Like Eco, he is ill at ease with this

reductionist approach, summarizing its ramifications as follows:

The list of objections could be and has been lengthened indefinitely: confusing technology itself with its use of the media makes of the media an abstract, undifferentiated force and produces its image in an imaginary "public" for mass consumption; the magical naivete of supposed causalities turns the media into a catch-all and contagious "mana

According to Melanesian and Polynesian mythology, ''mana'' is a supernatural force that permeates the universe. Anyone or anything can have ''mana''. They believed it to be a cultivation or possession of energy and power, rather than being ...

"; apocalyptic millenarianism

Millenarianism or millenarism (from Latin , "containing a thousand") is the belief by a religious, social, or political group or movement in a coming fundamental transformation of society, after which "all things will be changed". Millenaria ...

invents the figure of a ''homo mass-mediaticus'' without ties to historical and social context, and so on.

Furthermore, when ''

Wired

''Wired'' (stylized as ''WIRED'') is a monthly American magazine, published in print and online editions, that focuses on how emerging technologies affect culture, the economy, and politics. Owned by Condé Nast, it is headquartered in San Fran ...

'' magazine interviewed him in 1995, Debray stated that he views McLuhan "more as a poet than a historian, a master of intellectual collage rather than a systematic analyst.… McLuhan overemphasizes the technology behind cultural change at the expense of the usage that the messages and codes make of that technology."

Dwight Macdonald

Dwight Macdonald (March 24, 1906 – December 19, 1982) was an American writer, editor, film critic, social critic, literary critic, philosopher, and activist. Macdonald was a member of the New York Intellectuals and editor of their leftist mag ...

, in turn, reproached McLuhan for his focus on television and for his "

aphoristic" style of

prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the f ...

, which he believes leaves ''Understanding Media'' filled with "contradictions,

non-sequiturs, facts that are distorted and facts that are not facts, exaggerations, and chronic

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

al

vagueness

In linguistics and philosophy, a vague predicate is one which gives rise to borderline cases. For example, the English adjective "tall" is vague since it is not clearly true or false for someone of middling height. By contrast, the word "prime" ...

."

Additionally,

Brian Winston's ''Misunderstanding Media'', published in 1986, chides McLuhan for what he sees as his

technologically deterministic stances.

Raymond Williams

Raymond Henry Williams (31 August 1921 – 26 January 1988) was a Welsh socialist writer, academic, novelist and critic influential within the New Left and in wider culture. His writings on politics, culture, the media and literature contribut ...

furthers this point of contention, claiming:

The work of McLuhan was a particular culmination of an aesthetic theory which became, negatively, a social theory ... It is an apparently sophisticated technological determinism which has the significant effect of indicating a Social determinism, social and cultural determinism.… For if the medium – whether print or television – is the cause, all other causes, all that men ordinarily see as history, are at once reduced to effects.

David Carr states that there has been a long line of "academics who have made a career out of deconstructing McLuhan’s effort to define the modern media ecosystem", whether it be due to what they see as McLuhan's ignorance toward sociohistorical context or the style of his argument.

While some critics have taken issue with McLuhan's writing style and mode of argument, McLuhan himself urged readers to think of his work as "probes" or "mosaics" offering a toolkit approach to thinking about the media. His Eclecticism, eclectic writing style has also been praised for its postmodern sensibilities and suitability for virtual space.

''The Medium Is the Massage'' (1967)

''The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects'', published in 1967, was McLuhan's best seller,

[Gary Wolf (journalist), Wolf, Gary. 1 January 1996.]

The Wisdom of Saint Marshall, the Holy Fool

" Wired (magazine), ''Wired'' 4(1). Retrieved 24 June 2020. "eventually selling nearly a million copies worldwide." Initiated by Quentin Fiore, McLuhan adopted the term "massage" to denote the effect each medium has on the human sensorium, taking inventory of the "effects" of numerous media in terms of how they "massage" the sensorium.

Fiore, at the time a prominent graphic designer and communications consultant, set about composing the visual illustration of these effects which were compiled by Jerome Agel. Near the beginning of the book, Fiore adopted a pattern in which an image demonstrating a media effect was presented with a Textuality, textual synopsis on the facing page. The reader experiences a repeated shifting of analytic registers—from "reading" Typography, typographic print to "scanning" photographic facsimiles—reinforcing McLuhan's overarching argument in this book: namely, that each medium produces a different "massage" or "effect" on the human sensorium.

In ''The Medium Is the Massage'', McLuhan also rehashed the argument—which first appeared in the Prologue to 1962's ''The Gutenberg Galaxy''—that all media are "extensions" of our human senses, bodies and minds.

Finally, McLuhan described key points of change in how man has viewed the world and how these views were changed by the adoption of new media. "The technique of invention was the discovery of the nineteenth [century]", brought on by the adoption of fixed points of view and perspective by typography, while "[t]he technique of the suspension of judgement, suspended judgment is the discovery of the twentieth century," brought on by the bard abilities of radio, movies and television.

The past went that-a-way. When faced with a totally new situation we tend always to attach ourselves to the objects, to the flavor of the most recent past. We look at the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backward into the future. Suburbia lives imaginatively in Bonanza-land.

An audio recording version of McLuhan's famous work was made by Columbia Records. The recording consists of a pastiche of statements made by McLuhan ''interrupted'' by other speakers, including people speaking in various phonations and falsettos, discordant sounds and 1960s incidental music in what could be considered a deliberate attempt to translate the disconnected images seen on TV into an audio format, resulting in the prevention of a connected stream of conscious thought. Various audio recording techniques and statements are used to illustrate the relationship between spoken, literary speech and the characteristics of electronic audio media. McLuhan biographer Philip Marchand called the recording "the 1967 equivalent of a McLuhan video."

"I wouldn't be seen dead with a living work of art."—'Old man' speaking

"Drop this jiggery-pokery and talk straight turkey."—'Middle aged man' speaking

''War and Peace in the Global Village'' (1968)

In ''War and Peace in the Global Village'', McLuhan used James Joyce's ''Finnegans Wake'', an inspiration for this study of war throughout history, as an indicator as to how war may be conducted in the future.

Joyce's ''Wake'' is claimed to be a gigantic cryptogram which reveals a cyclic pattern for the whole history of man through its Ten Thunders. Each "thunder" below is a 100-character portmanteau of other words to create a statement he likens to an effect that each technology has on the society into which it is introduced. In order to glean the most understanding out of each, the reader must break the portmanteau into separate words (and many of these are themselves portmanteaus of words taken from multiple languages other than English) and speak them aloud for the spoken effect of each word. There is much dispute over what each portmanteau truly denotes.

McLuhan claims that the ten thunders in ''Wake'' represent different stages in the history of man:

*''Thunder 1: Paleolithic to Neolithic.'' Speech. Split of East/West. From herding to harnessing animals.

*''Thunder 2: Clothing as weaponry.'' Enclosure of private parts. First social aggression.

*''Thunder 3: Specialism.'' Centralism via wheel, transport, cities: civil life.

*''Thunder 4: Markets and truck gardens.'' Patterns of nature submitted to greed and power.

*''Thunder 5: Printing.'' Distortion and translation of human patterns and postures and pastors.

*''Thunder 6: Industrial Revolution.'' Extreme development of print process and individualism.

*''Thunder 7: Tribal man again.'' All characters end up separate, private man. Return of choric.

*''Thunder 8: Movies.'' Pop art, pop Kulch via tribal radio. Wedding of sight and sound.

*''Thunder 9: Car and Plane.'' Both centralizing and Decentralization, decentralizing at once create cities in crisis. Speed and death.

*''Thunder 10: Television.'' Back to tribal involvement in tribal mood-mud. The last thunder is a turbulent, muddy wake, and murk of non-visual, tactile man.

''From Cliché to Archetype'' (1970)

Collaborating with Canadian poetry, Canadian poet Wilfred Watson in ''From Cliché to Archetype'' (1970), McLuhan approaches the various implications of the verbal cliché and of the archetype. One major facet in McLuhan's overall framework introduced in this book that is seldom noticed is the provision of a new term that actually succeeds the global village: the ''global theater''.

In McLuhan's terms, a ''cliché'' is a "normal" action, phrase, etc. which becomes so often used that we are "Anesthesia, anesthetized" to its effects. McLuhan provides the example of Eugène Ionesco's play ''The Bald Soprano'', whose dialogue consists entirely of phrases Ionesco pulled from an Assimil language book: "Ionesco originally put all these idiomatic English clichés into literary French which presented the English in the most absurd aspect possible."

McLuhan's ''archetype'' "is a quoted extension, medium, technology, or environment." ''Environment'' would also include the kinds of "awareness" and cognitive shifts brought upon people by it, not totally unlike the psychological context Carl Jung described.

McLuhan also posits that there is a factor of interplay between the ''cliché'' and the ''archetype'', or a "doubleness:"

Another theme of the Wake [''Finnegans Wake''] that helps in the understanding of the paradoxical shift from cliché to archetype is 'past time are pastimes.' The dominant technologies of one age become the games and pastimes of a later age. In the 20th century, the number of 'past times' that are simultaneously available is so vast as to create cultural anarchy. When all the cultures of the world are simultaneously present, the work of the artist in the elucidation of form takes on new scope and new urgency. Most men are pushed into the artist's role. The artist cannot dispense with the principle of 'doubleness' or 'interplay' because this type of hendiadys dialogue is essential to the very structure of consciousness, awareness, and autonomy.

McLuhan relates the cliché-to-archetype process to the Theatre of the Absurd, Theater of the Absurd:

Pascal, in the seventeenth century, tells us that the heart has many reasons of which the head knows nothing. The Theater of the Absurd is essentially a communicating to the head of some of the silent languages of the heart which in two or three hundred years it has tried to forget all about. In the seventeenth century world the languages of the heart were pushed down into the unconscious by the dominant print cliché.

The "languages of the heart," or what McLuhan would otherwise define as oral culture, were thus made archetype by means of the printing press, and turned into cliché.

The satellite medium, McLuhan states, encloses the Earth in a man-made environment, which "ends 'Nature' and turns the globe into a repertory theater to be programmed." All previous environments (book, newspaper, radio, etc.) and their artifacts are retrieved under these conditions ("past times are pastimes"). McLuhan thereby meshes this into the term ''global theater''. It serves as an update to his older concept of the global village, which, in its own definitions, can be said to be subsumed into the overall condition described by that of the global theater.

''The Global Village'' (1989)

In his posthumous book, ''The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century'' (1989), McLuhan, collaborating with Bruce R. Powers, provides a strong conceptual framework for understanding the cultural implications of the technological advances associated with the rise of a worldwide Electronic communication network, electronic network. This is a major work of McLuhan's as it contains the most extensive elaboration of his concept of ''acoustic space'', and provides a critique of standard 20th-century communication models such as the Shannon–Weaver model.

McLuhan distinguishes between the existing worldview of ''visual space''—a linear, quantitative, classically geometric model—and that of ''acoustic space''—a Holism, holistic, qualitative order with an intricate, paradoxical topology: "Acoustic Space has the basic character of a sphere whose focus or center is simultaneously everywhere and whose margin is nowhere." The transition from ''visual'' to ''acoustic'' ''space'' was not automatic with the advent of the global network, but would have to be a conscious project. The "universal environment of simultaneous electronic flow" inherently favors Right brain, right-brain Acoustic Space, yet we are held back by habits of adhering to a fixed point of view. There are no boundaries to sound. We hear from all directions at once. Yet Acoustic and Visual Space are, in fact, inseparable. The resonant interval is the invisible borderline between Visual and Acoustic Space. This is like the television camera that the Apollo 8 astronauts focused on the Earth after they had orbited the moon.

McLuhan illustrates how it feels to exist within acoustic space by quoting from the autobiography of Jacques Lusseyran, ''And There Was Light.'' Lusseyran lost his eyesight in a violent accident as a child, and the autobiography describes how a reordering of his sensory life and perception followed:

When I came upon the myth of objectivity in certain modern thinkers, it made me angry. So, there was only one world for these people, the same for everyone. And all the other worlds were to be counted as illusions left over from the past. Or why not call them by their name - hallucinations? I had learned to my cost how wrong they were.