Lord Howe Island Subtropical Forests on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lord Howe Island (; formerly Lord Howe's Island) is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the

Prior to European discovery and settlement, Lord Howe Island apparently was uninhabited, and unknown to

Prior to European discovery and settlement, Lord Howe Island apparently was uninhabited, and unknown to

Permanent settlement on Lord Howe was established in June 1834, when the British whaling

Permanent settlement on Lord Howe was established in June 1834, when the British whaling

In 1849, just 11 people were living on the island, but soon the island farms expanded. In the 1850s, gold was discovered on mainland Australia, where crews would abandon their ships, preferring to dig for gold than to risk their lives at sea. As a consequence, many vessels avoided the mainland and Lord Howe Island experienced an increasing trade, which peaked between 1855 and 1857. In 1851, about 16 people were living on the island. Vegetable crops now included potatoes, carrots, maize, pumpkin, taro, watermelon, and even grapes, passionfruit, and coffee. Between 1851 and 1853, several aborted proposals were made by the NSW government to establish a penal settlement on the island.

From 1851 to 1854,

In 1849, just 11 people were living on the island, but soon the island farms expanded. In the 1850s, gold was discovered on mainland Australia, where crews would abandon their ships, preferring to dig for gold than to risk their lives at sea. As a consequence, many vessels avoided the mainland and Lord Howe Island experienced an increasing trade, which peaked between 1855 and 1857. In 1851, about 16 people were living on the island. Vegetable crops now included potatoes, carrots, maize, pumpkin, taro, watermelon, and even grapes, passionfruit, and coffee. Between 1851 and 1853, several aborted proposals were made by the NSW government to establish a penal settlement on the island.

From 1851 to 1854,

The first plane to appear on the island was in 1931, when

The first plane to appear on the island was in 1931, when

Parliamentary Electorates and Elections Act, 1893

'. Since 1894, Lord Howe Island has been included in the following

Lord Howe Island is known for its geology, birds, plants, and marine life. Popular tourist activities include

Lord Howe Island is known for its geology, birds, plants, and marine life. Popular tourist activities include

As distances to sites of interest are short,

As distances to sites of interest are short,

Lord Howe Island is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Lying in the

Lord Howe Island is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Lying in the  Both the north and south sections of the island are high ground of relatively untouched forest, in the south comprising two

Both the north and south sections of the island are high ground of relatively untouched forest, in the south comprising two

Lord Howe Island is the highly eroded remains of a 7-million-year-old

Lord Howe Island is the highly eroded remains of a 7-million-year-old

Tasman Sea

The Tasman Sea (Māori: ''Te Tai-o-Rēhua'', ) is a marginal sea of the South Pacific Ocean, situated between Australia and New Zealand. It measures about across and about from north to south. The sea was named after the Dutch explorer Abe ...

between Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, part of the Australian state of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

. It lies directly east of mainland Port Macquarie

Port Macquarie is a coastal town in the local government area of Port Macquarie-Hastings. It is located on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, Australia, about north of Sydney, and south of Brisbane. The town is located on the Tasman Sea co ...

, northeast of Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, and about southwest of Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

. It is about long and between wide with an area of , though just of that comprise the low-lying developed part of the island.

Along the west coast is a sandy semi-enclosed sheltered coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Co ...

lagoon. Most of the population lives in the north, while the south is dominated by forested hills rising to the highest point on the island, Mount Gower (). The Lord Howe Island Group comprises 28 islands, islets, and rocks. Apart from Lord Howe Island itself, the most notable of these is the volcanic and uninhabited Ball's Pyramid

Ball's Pyramid is an erosional remnant of a shield volcano and caldera lying southeast of Lord Howe Island in the Pacific Ocean. It is high, while measuring in length and only across, making it the tallest volcanic stack in the world. Bal ...

about to the southeast of Howe. To the north lies a cluster of seven small uninhabited islands called the Admiralty Group

The Admiralty Group of islets consists of eight rocky outcrops within 2 km of the north of Lord Howe Island. From south to north, these are:

#Soldier’s Cap

#Sugarloaf

#South Island

#Noddy

#Roach Island

#Tenth of June

#North Rock

#Flat Rock

...

.

The first reported sighting of Lord Howe Island took place on 17 February 1788, when Lieutenant Henry Lidgbird Ball

Henry Lidgbird Ball (7 December 1756 – 22 October 1818) was a Rear-Admiral in the Royal Navy of the British Empire. While Ball was best known as the commander of the First Fleet's , he was also notable for the exploration and the establishmen ...

, commander of the Armed Tender HMS ''Supply'', was en route from Botany Bay

Botany Bay (Dharawal: ''Kamay''), an open oceanic embayment, is located in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, south of the Sydney central business district. Its source is the confluence of the Georges River at Taren Point and the Cook ...

to found a penal settlement on Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

. On the return journey, Ball sent a party ashore on Lord Howe Island to claim it as a British possession. It subsequently became a provisioning port for the whaling industry, and was permanently settled in June 1834. When whaling declined, the 1880s saw the beginning of the worldwide export of the endemic kentia palms, which remains a key component of the island's economy. The other continuing industry, tourism, began after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

ended in 1945.

The Lord Howe Island Group is part of the state of New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

and is regarded legally as an unincorporated area

An unincorporated area is a region that is not governed by a local municipal corporation. Widespread unincorporated communities and areas are a distinguishing feature of the United States and Canada. Most other countries of the world either have ...

administered by the Lord Howe Island Board, which reports to the New South Wales Minister for Environment and Heritage. The island's standard time zone

A time zone is an area which observes a uniform standard time for legal, Commerce, commercial and social purposes. Time zones tend to follow the boundaries between Country, countries and their Administrative division, subdivisions instead of ...

is UTC+10:30, or UTC+11

UTC+11:00 is an identifier for a time offset from UTC of +11:00. This time is used in:

As standard time (year-round)

''Principal cities: Nouméa, Magadan, Honiara, Port Vila, Palikir, Weno, Buka, Arawa '' North Asia

*Russia – Magad ...

when daylight saving time

Daylight saving time (DST), also referred to as daylight savings time or simply daylight time (United States, Canada, and Australia), and summer time (United Kingdom, European Union, and others), is the practice of advancing clocks (typicall ...

applies. The currency is the Australian dollar

The Australian dollar (sign: $; code: AUD) is the currency of Australia, including its external territories: Christmas Island, Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Norfolk Island. It is officially used as currency by three independent Pacific Island s ...

. Commuter airlines provide flights to Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

, and Port Macquarie

Port Macquarie is a coastal town in the local government area of Port Macquarie-Hastings. It is located on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, Australia, about north of Sydney, and south of Brisbane. The town is located on the Tasman Sea co ...

.

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. It ...

records the Lord Howe Island Group as a World Heritage Site

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

of global natural significance. Most of the island is virtually untouched forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

, with many of the plants and animals found nowhere else in the world. Other natural attractions include the diversity of the landscapes, the variety of upper mantle

The upper mantle of Earth is a very thick layer of rock inside the planet, which begins just beneath the crust (at about under the oceans and about under the continents) and ends at the top of the lower mantle at . Temperatures range from appro ...

and oceanic basalts, the world's southernmost barrier coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Co ...

, nesting seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s, and the rich historical and cultural heritage. The Lord Howe Island Act 1981 established a "Permanent Park Preserve" (covering about 70% of the island). The island was added to the Australian National Heritage List

The Australian National Heritage List or National Heritage List (NHL) is a heritage register, a list of national heritage places deemed to be of outstanding heritage significance to Australia, established in 2003. The list includes natural and ...

on 21 May 2007 and the New South Wales State Heritage Register

The New South Wales State Heritage Register, also known as NSW State Heritage Register, is a heritage list of places in the state of New South Wales, Australia, that are protected by New South Wales legislation, generally covered by the Heritag ...

on 2 April 1999. The surrounding waters are a protected region designated the Lord Howe Island Marine Park

Lord Howe Island Marine Park is the site of Australia's and the world's most southern coral reef ecosystem. The island is 10 km in length, 2 km wide and consists of a large lagoonal reef system along its leeward side, with 28 small isl ...

.

Bioregion

Lord Howe Island is part of theIBRA

The Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) is a biogeographic regionalisation of Australia developed by the Australian government's Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population, and Communities. It was devel ...

region Pacific Subtropical Islands (code PSI) and is subregion PSI01 with an area of . In the WWF ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of l ...

system, Lord Howe Island constitutes the entirety of the 'Lord Howe Island subtropical forests' ecoregion (WWF ID#AA0109). This ecoregion is in the Australasian realm

The Australasian realm is a biogeographic realm that is coincident with, but not (by some definitions) the same as, the geographical region of Australasia. The realm includes Australia, the island of New Guinea (comprising Papua New Guinea and ...

, and the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests

Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests (TSMF), also known as tropical moist forest, is a subtropical and tropical forest habitat type defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature.

Description

TSMF is generally found in large, discont ...

biome

A biome () is a biogeographical unit consisting of a biological community that has formed in response to the physical environment in which they are found and a shared regional climate. Biomes may span more than one continent. Biome is a broader ...

. The WWF ecoregion has an area of 14 km2.

History

Prehistory

Prior to European discovery and settlement, Lord Howe Island apparently was uninhabited, and unknown to

Prior to European discovery and settlement, Lord Howe Island apparently was uninhabited, and unknown to Polynesian peoples

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sout ...

of the South Pacific. No evidence to suggest prehistoric human activity has ever been found on Lord Howe Island, even after an extensive archaeological investigation in 1996. In ''Australian Archaeology'' Atholl Anderson concluded in 2003 that, "the case for no pre-European settlement on Lord Howe Island is now more compelling than before" and that "the absence of pre-European settlement on Lord Howe Island is not easily explained. At 16 km2 it is twice the size of Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

and half the size of Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

, two other remote subtropical islands that were inhabited prehistorically, and it had a biota very similar to that of Norfolk Island."http://australianarchaeology.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Anderson-2003.pdf

1788–1834: First European visits

The first reported European sighting of Lord Howe Island was on 17 February 1788 by LieutenantHenry Lidgbird Ball

Henry Lidgbird Ball (7 December 1756 – 22 October 1818) was a Rear-Admiral in the Royal Navy of the British Empire. While Ball was best known as the commander of the First Fleet's , he was also notable for the exploration and the establishmen ...

, commander of the Armed Tender (the oldest and smallest of the First Fleet

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 ships that brought the first European and African settlers to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command ...

ships), which was on its way from Botany Bay with a cargo of nine male and six female convicts to found a penal settlement

A penal colony or exile colony is a settlement used to exile prisoners and separate them from the general population by placing them in a remote location, often an island or distant colonial territory. Although the term can be used to refer to ...

on Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

. On the return journey of 13 March 1788, Ball observed Ball's Pyramid

Ball's Pyramid is an erosional remnant of a shield volcano and caldera lying southeast of Lord Howe Island in the Pacific Ocean. It is high, while measuring in length and only across, making it the tallest volcanic stack in the world. Bal ...

and sent a party ashore on Lord Howe Island to claim it as a British possession. Numerous turtles and tame birds were captured and returned to Sydney. Ball named Mount Lidgbird

Mount Lidgbird, also Mount Ledgbird and Big Hill, is located in the southern section of Lord Howe Island, just north of Mount Gower, from which it is separated by the saddle at the head of Erskine Valley, and has its peak at above sea level.

...

and Ball's Pyramid after himself and the main island after Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, (8 March 1726 – 5 August 1799) was a British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations aga ...

, who was First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

at the time.

Many names on the island date from this time, and also from May of the same year, when four ships of the First Fleet, , , ''Lady Penrhyn

''Lady Penrhyn'' was built on the River Thames in 1786 as a slave ship.

''Lady Penrhyn'' was designed as a two-deck ship for use in the Atlantic slave trade, with a capacity of 275 slaves. She was part-owned by William Compton Sever, who serve ...

'' and , visited it. Much of the plant and animal life was first recorded in the journals and diaries of visitors such as David Blackburn, Master of ''Supply'', and Arthur Bowes Smyth

Arthur Bowes Smyth (23 August 175031 March 1790) was a naval surgeon, who traveled on ''Lady Penrhyn'' as a part of the First Fleet that established a penal colony in New South Wales. Smyth kept a diary and documented the natural history he enc ...

, surgeon of the ''Lady Penrhyn''.

Smyth was in Sydney when the ''Supply'' returned from the first voyage to Norfolk Island. His journal entry for 19 March 1788 noted that "the ''Supply'', in her return, landed at the island she iscoveredin going out, and all were very agreeably surprised to find great numbers of fine turtle on the beach and, on the land amongst the trees, great numbers of fowls very like a guinea hen, and another species of fowl not unlike the landrail in England, and all so perfectly tame that you could frequently take hold of them with your hands but could, at all times, knock down as many as you thought proper, with a short stick. Inside the reef also there were fish innumerable, which were so easily taken with a hook and line as to be able to catch a boat full in a short time. She brought thirteen large turtle to Port Jackson and many were distributed among the camp and fleet."

Watercolour sketches of native birds including the Lord Howe woodhen

The Lord Howe woodhen (''Hypotaenidia sylvestris'') also known as the Lord Howe Island woodhen or Lord Howe (Island) rail, is a flightless bird of the rail family, (Rallidae). It is endemic to Lord Howe Island off the Australian coast. It is curr ...

(''Gallirallus sylvestris''), white gallinule ('' Porphyrio albus''), and Lord Howe pigeon (''Columba vitiensis godmanae''), were made by artists including George Raper

George Raper (19 September 1769 – 29 September 1796) was a Royal Navy officer who as an able seaman joined the crew of and the First Fleet to establish a colony at Botany Bay, New South Wales, now Australia. He is best known today for his ...

and John Hunter. As the latter two birds were soon hunted to extinction, these paintings are their only remaining pictorial record. Over the next three years, the ''Supply'' returned to the island several times in search of turtles, and the island was also visited by ships of the Second

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds ...

and Third Fleet

The United States Third Fleet is one of the numbered fleets in the United States Navy. Third Fleet's area of responsibility includes approximately fifty million square miles of the eastern and northern Pacific Ocean areas including the Bering ...

s. Between 1789 and 1791, the Pacific whale industry was born with British and American whaling ships chasing sperm whale

The sperm whale or cachalot (''Physeter macrocephalus'') is the largest of the toothed whales and the largest toothed predator. It is the only living member of the genus ''Physeter'' and one of three extant species in the sperm whale famil ...

s (''Physeter macrocephalus'') along the equator to the Gilbert and Ellice archipelago, then south into Australian and New Zealand waters. The American fleet numbered 675 ships and Lord Howe was located in a region known as the Middle Ground noted for sperm whales and southern right whale

The southern right whale (''Eubalaena australis'') is a baleen whale, one of three species classified as right whales belonging to the genus ''Eubalaena''. Southern right whales inhabit oceans south of the Equator, between the latitudes of 20 ...

s (''Eubalaena australis'').

The island was subsequently visited by many government and whaling ships sailing between New South Wales and Norfolk Island and across the Pacific, including many from the American whaling fleet, so its reputation as a provisioning port preceded settlement, with some ships leaving goats and pigs on the island as food for future visitors. Between July and October 1791, the Third Fleet ships arrived at Sydney and within days, the deckwork was being reconstructed for a future in the lucrative whaling industry. Whale oil

Whale oil is oil obtained from the blubber of whales. Whale oil from the bowhead whale was sometimes known as train oil, which comes from the Dutch word ''traan'' ("tears, tear" or "drop").

Sperm oil, a special kind of oil obtained from the ...

was to become Australia's most profitable export until the 1830s, and the whaling industry shaped Lord Howe Island's early history.

1834–1841: Settlement

Permanent settlement on Lord Howe was established in June 1834, when the British whaling

Permanent settlement on Lord Howe was established in June 1834, when the British whaling barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel with three or more mast (sailing), masts having the fore- and mainmasts Square rig, rigged square and only the mizzen (the aftmost mast) Fore-and-aft rig, rigged fore and aft. Som ...

''Caroline'', sailing from New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

and commanded by Captain John Blinkenthorpe, landed at what is now known as Blinky Beach. They left three men, George Ashdown, James Bishop, and Chapman, who were employed by a Sydney whaling firm to establish a supply station. The men were initially to provide meat by fishing and by raising pigs and goats from feral stock. They landed with (or acquired from a visiting ship) their Māori

Māori or Maori can refer to:

Relating to the Māori people

* Māori people of New Zealand, or members of that group

* Māori language, the language of the Māori people of New Zealand

* Māori culture

* Cook Islanders, the Māori people of the C ...

wives and two Māori boys. Huts were built in an area now known as Old Settlement, which had a supply of fresh water, and a garden was established west of Blinky Beach.

This was a cashless society

In a cashless society, financial transactions are not conducted with physical banknotes or coins, but instead with digital information (usually an electronic representation of money). Cashless societies have existed from the time when human so ...

; the settlers barter

In trade, barter (derived from ''baretor'') is a system of exchange in which participants in a transaction directly exchange goods or services for other goods or services without using a medium of exchange, such as money. Economists distingu ...

ed their stores of water, wood, vegetables, meat, fish, and bird feathers for clothes, tea, sugar, tools, tobacco, and other commodities not available on the island, but it was the whalers' valuation that had to be accepted. These first settlers eventually left the island when they were bought out for £350 in September 1841 by businessmen Owen Poole and Richard Dawson (later joined by John Foulis), whose employees and others then settled on the island.

1842–1860: Trading provisions

The new business was advertised and ships trading between Sydney and theNew Hebrides

New Hebrides, officially the New Hebrides Condominium (french: link=no, Condominium des Nouvelles-Hébrides, "Condominium of the New Hebrides") and named after the Hebrides Scottish archipelago, was the colonial name for the island group ...

(Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

) would also put into the island. ''Rover's Bride'', a small cutter, became the first regular trading vessel. Between 1839 and 1859, five to 12 ships made landfall each year, occasionally closer to 20, with seven or eight at a time laying off the reef. In 1842 and 1844, the first children were born on the island. Then in 1847, Poole, Dawson, and Foulis, bitter at failing to obtain a land lease from the New South Wales government, abandoned the settlement although three of their employees remained. One family, the Andrews, after finding some onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' L., from Latin ''cepa'' meaning "onion"), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus ''Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the onion ...

s on the beach in 1848, cultivated them as the "Lord Howe red onion", which was popular in the Southern Hemisphere for about 30 years until the crop was attacked by smut disease.

In 1849, just 11 people were living on the island, but soon the island farms expanded. In the 1850s, gold was discovered on mainland Australia, where crews would abandon their ships, preferring to dig for gold than to risk their lives at sea. As a consequence, many vessels avoided the mainland and Lord Howe Island experienced an increasing trade, which peaked between 1855 and 1857. In 1851, about 16 people were living on the island. Vegetable crops now included potatoes, carrots, maize, pumpkin, taro, watermelon, and even grapes, passionfruit, and coffee. Between 1851 and 1853, several aborted proposals were made by the NSW government to establish a penal settlement on the island.

From 1851 to 1854,

In 1849, just 11 people were living on the island, but soon the island farms expanded. In the 1850s, gold was discovered on mainland Australia, where crews would abandon their ships, preferring to dig for gold than to risk their lives at sea. As a consequence, many vessels avoided the mainland and Lord Howe Island experienced an increasing trade, which peaked between 1855 and 1857. In 1851, about 16 people were living on the island. Vegetable crops now included potatoes, carrots, maize, pumpkin, taro, watermelon, and even grapes, passionfruit, and coffee. Between 1851 and 1853, several aborted proposals were made by the NSW government to establish a penal settlement on the island.

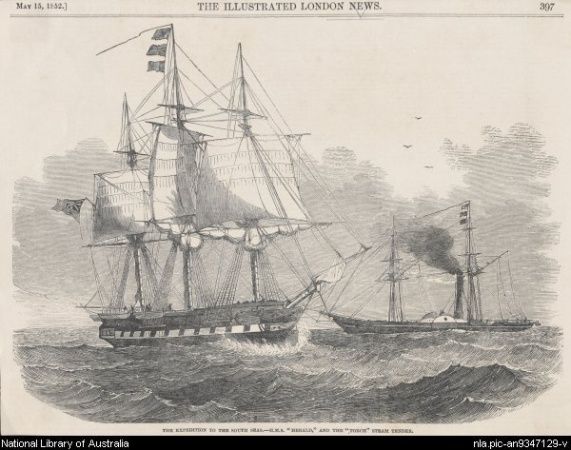

From 1851 to 1854, Henry Denham

Henry Denham was one of the outstanding England, English Printer (publisher), printers of the sixteenth century.

He was apprenticed to Richard Tottel and took up the freedom of the Stationers' Company on 30 August 1560. In 1564 he set up his own ...

captain of HMS ''Herald'', which was on a scientific expedition to the southwest Pacific (1852–1856), completed the island's first hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore oil exploration/offshore oil drilling and related activities. Strong emphasis is placed ...

. On board were three Scottish biologists, William Milne (a gardener-botanist from the Edinburgh Botanic Garden

The Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) is a scientific centre for the study of plants, their diversity and conservation, as well as a popular tourist attraction. Founded in 1670 as a physic garden to grow medicinal plants, today it occupies ...

), John MacGillivray

John MacGillivray (18 December 1821 – 6 June 1867) was a Scottish naturalist, active in Australia between 1842 and 1867.

MacGillivray was born in Aberdeen, the son of ornithologist William MacGillivray. He took part in three of the Royal Nav ...

(naturalist) who collected fish and plant specimens, and assistant surgeon and zoologist Denis Macdonald. Together, these men established much basic information on the geology, flora, and fauna of the island.

Around 1853, a further three settlers arrived on the American whaling barque ''Belle'', captained by Ichabod Handy. George Campbell (who died in 1856) and Jack Brian (who left the island in 1854) arrived, and the third, Nathan Thompson, brought three women (called Botanga, Bogoroo, and a girl named Bogue) from the Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands ( gil, Tungaru;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this n ...

. When his first wife Botanga died, he then married Bogue. Thompson was the first resident to build a substantial house in the 1860s from mainland cedar washed up on the beach. Most of the residents with island ancestors have blood relations or are connected by marriage to Thompson and his second wife Bogue.

In 1855, the island was officially designated as part of New South Wales by the Constitution Act.

1861–1890: Scientific expeditions

From the early 1860s, whaling declined rapidly with the increasing use of petroleum, the onset of theCalifornia Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

, and the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

—with unfortunate consequences for the island. To explore alternative means of income, Thompson, in 1867, purchased the ''Sylph'', which was the first local vessel to trade with Sydney (mainly pigs and onions). It anchored in deep water at what is now Sylph's Hole off Old Settlement Beach, but was eventually tragically lost at sea in 1873, which added to the woes of the island at that time.

In 1869, the island was visited by magistrate P. Cloete aboard the ''Thetis'' investigating a possible murder. He was accompanied by Charles Moore, director of the Botanic Gardens in Sydney, and his assistant William Carron, who forwarded plant specimens to Ferdinand Mueller at the botanic gardens in Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, who by 1875, had catalogued and published 195 species. Also on the ship was William Fitzgerald, a surveyor, and Mr Masters from the Australian Museum

The Australian Museum is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It is the oldest museum in Australia,Design 5, 2016, p.1 and the fifth oldest natural history museum in the ...

. Together, they surveyed the island with the findings published in 1870 when the population was listed as 35 people, their 13 houses built of split palm

Palm most commonly refers to:

* Palm of the hand, the central region of the front of the hand

* Palm plants, of family Arecaceae

**List of Arecaceae genera

* Several other plants known as "palm"

Palm or Palms may also refer to:

Music

* Palm (ba ...

batten

A batten is most commonly a strip of solid material, historically wood but can also be of plastic, metal, or fiberglass. Battens are variously used in construction, sailing, and other fields.

In the lighting industry, battens refer to linea ...

s thatched

Thatching is the craft of building a roof with dry vegetation such as straw, water reed, sedge (''Cladium mariscus''), rushes, heather, or palm branches, layering the vegetation so as to shed water away from the inner roof. Since the bulk of ...

on the roof and sides with palm leaves. Around this time, a downturn of trade began with the demise of the whaling industry and sometimes six to 12 months passed without a vessel calling. With the provisions rotting in the storehouses, the older families lost interest in market gardening.

From 1860 to 1872, 43 ships had collected provisions, but from 1873 to 1887, fewer than a dozen had done so. This prompted some activity from the mainland. In 1876, a government report on the island was submitted by surveyor William Fitzgerald based on a visit in the same year. He suggested that coffee be grown, but the kentia palm was already catching world attention. In 1878, the island was declared a forest reserve and Captain Richard Armstrong became the first resident government administrator. He encouraged schools, tree-planting, and the palm trade, dynamited the north passage to the lagoon, and built roads. He also managed to upset the residents, and parliamentarian Bowie Wilson

John Bowie Wilson (17 June 1820 – 30 April 1883), often referred to as J. Bowie Wilson, was a politician, gold miner and hydropath in colonial New South Wales, a member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly for more than 12 years. Person ...

was sent from the mainland in April 1882 to investigate the situation. With Wilson was a team of scientists who included H. Wilkinson from the Mines Department, W. Condor from the Survey Department, J. Duff from the Sydney Botanical Gardens, and A. Morton from the Australian Museum. J. Sharkey from the Government Printing Office took the earliest known photographs of the island and its residents. A full account of the island appeared in the report from this visit, which recommended that Armstrong be replaced. Meanwhile, the population had increased considerably and included 29 children; the report recommended that a schoolmaster be appointed. This study sealed a lasting relationship with three scientific organisations, the Australian Museum, Sydney Royal Botanic Gardens, and Kew Royal Botanic Gardens

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,100 ...

.

1890–1999

In 1883, the companyBurns Philp

Burns Philp (properly Burns, Philp & Co, Limited) was once a major Australian shipping line and merchant that operated in the South Pacific. When the well-populated islands around New Guinea were targeted for blackbirding in the 1880s, a new ...

started a regular shipping service and the number of tourists gradually increased. By 1932, with the regular tourist run of SS ''Morinda'', tourism became the second-largest source of external income after palm sales to Europe. ''Morinda'' was replaced by in 1932, and she in turn by other vessels. The service continues into the present day with the fortnightly Island Trader service from Port Macquarie.

The palm trade began in the 1880s when the lowland kentia palm (''Howea forsteriana

''Howea forsteriana'', the Kentia palm, thatch palm or palm court palm, is a species of flowering plant in the palm family, Arecaceae, endemic to Lord Howe Island in Australia. It is also widely grown on Norfolk Island. It is a relatively slow-g ...

'') was first exported to Britain, Europe, and America, but the trade was only placed on a firm financial footing when the Lord Howe Island Kentia Palm Nursery was formed in 1906 (see below).

The first plane to appear on the island was in 1931, when

The first plane to appear on the island was in 1931, when Francis Chichester

Sir Francis Charles Chichester KBE (17 September 1901 – 26 August 1972) was a British businessman, pioneering aviator and solo sailor.

He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for becoming the first person to sail single-handed around the worl ...

alighted on the lagoon in a de Havilland Gipsy Moth

The de Havilland DH.60 Moth is a 1920s British two-seat touring and training aircraft that was developed into a series of aircraft by the de Havilland Aircraft Company.

Development

The DH.60 was developed from the larger DH.51 biplane. ...

converted into a floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

. It was damaged there in an overnight storm, but repaired with the assistance of islanders and then took off successfully nine weeks later for a flight to Sydney. After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, in 1947, tourists arrived on Catalina

Catalina may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''The Catalina'', a 2012 American reality television show

* ''Catalina'' (novel), a 1948 novel by W. Somerset Maugham

* Catalina (''My Name Is Earl''), character from the NBC sitcom ''My Name Is Earl''

...

and then four-engined Sandringham Sandringham can refer to:

Places

* Sandringham, New South Wales, Australia

* Sandringham, Queensland, Australia

* Sandringham, Victoria, Australia

**Sandringham railway line

**Sandringham railway station

**Electoral district of Sandringham

* Sand ...

flying boats of Ansett Flying Boat Services

Ansett Australia was a major Australian airline group, based in Melbourne, Australia. The airline flew domestically within Australia and from the 1990s to destinations in Asia. After operating for 65 years, the airline was placed into adminis ...

operating out of Rose Bay, Sydney, and landing on the lagoon, the journey taking about 3½ hours. When Lord Howe Island Airport

Lord Howe Island Airport is an airport providing air transportation to Lord Howe Island. Lord Howe Island is located in the Tasman Sea, east of Port Macquarie on the coast of mainland Australia. The airport is operated by the Lord Howe Island ...

was completed in 1974, the seaplanes were eventually replaced with QantasLink

QantasLink is a regional brand of Australian airline Qantas and is an affiliate member of the Oneworld airline alliance. It is a major competitor to Regional Express Airlines and Virgin Australia Regional Airlines. As of September 2010 Qantas ...

twin-engined turboprop Dash 8–200 aircraft.

21st century

In 2002, theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

destroyer struck Wolf Rock, a reef at Lord Howe Island, and almost sank. In recent times, tourism has increased and the government of New South Wales has been increasingly involved with issues of conservation.

On 17 October 2011, a supply ship, M/V ''Island Trader'', with 20 tons of fuel, ran aground in the lagoon. The ship refloated at high tide with no loss of crew or cargo.

The 2016 film '' The Shallows'' starring Blake Lively

Blake Ellender Lively ( Brown; born August 25, 1987) is an American actress. Born in Los Angeles, Lively is the daughter of actor Ernie Lively, and made her professional debut in his directorial project ''Sandman'' (1998). She starred as Brid ...

was largely filmed on the island.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in New South Wales

The COVID-19 pandemic in New South Wales is part of the ongoing worldwide pandemic of the coronavirus disease 2019 () caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (). The first confirmed case in New South Wales was identified on 1 ...

, a public health order was issued on 22 March 2020 that declared Lord Howe Island a public risk area and directed restricted access. As of that date there were no known cases of COVID-19 on the Island.

One of the most contentious issues amongst islanders in the 21st century is what to do about the rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the order Rodentia (), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal species are rodents. They are na ...

situation. Rodents have only been on the island since the ran aground in 1918, and have wiped out several endemic bird species and were thought to have done the same to the Lord Howe Island stick insect. A plan in 2016 was made to drop 42 tonnes of rat bait across the island, but the community was heavily divided.

The island was due to be declared rodent-free in October 2021, two years after the last live rat was found, but a living male and pregnant female were discovered in April 2021. The eradication, contrary to many community reservations, has seen birds, insects and plants flourish at levels not seen in decades.

Demographics

As at the 2016 census, the resident population was 382 people, and the number of tourists was not allowed to exceed 400. Early settlers were European and American whalers and many of their offspring have remained on the island for more than six generations. Residents now work in the kentia palm industry, tourism, retail, some fishing, and farming. In 1876 on Sundays, games and labour were suspended, but no religious services were held. Nowadays, the area known locally as Church Paddock hasAnglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

, Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

, and Adventist

Adventism is a branch of Protestant Christianity that believes in the imminent Second Coming (or the "Second Advent") of Jesus Christ. It originated in the 1830s in the United States during the Second Great Awakening when Baptist preacher Wil ...

churches, the religious affiliations on the island being 30% Anglican, 22% no religion, 18% Catholic and 12% Seventh Day Adventist. The ratio of the sexes is roughly equal, with 47% of the population in the age group 25–54 and 92% holding Australian citizenship

Australian nationality law details the conditions in which a person holds Australian legal nationality. The primary law governing nationality regulations is the Australian Citizenship Act 2007, which came into force on 1 July 2007 and is applic ...

.

Governance and land tenure

Official control of Lord Howe Island lay initially with theBritish Crown

The Crown is the state (polity), state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, British Overseas Territories, overseas territories, Provinces and territorie ...

until it passed to New South Wales in 1855, although until at least 1876, the islanders lived in "a relatively harmonious and self-regulating community". In 1878, Richard Armstrong was appointed administrator when the NSW Parliament declared the island a forest reserve, but as a result of ill feeling, and an enquiry, he was eventually removed from office on 31 May 1882 (he returned later that year though to view the transit of Venus

frameless, upright=0.5

A transit of Venus across the Sun takes place when the planet Venus passes directly between the Sun and a superior planet, becoming visible against (and hence obscuring a small portion of) the solar disk. During a trans ...

from present-day Transit Hill). After his removal, the island was administered by four successive magistrates until 1913, when a Sydney-based board was formed; in 1948, a resident superintendent was appointed. In 1913, the three-man Lord Howe Island Board of Control was established, mostly to regulate the palm seed

The Arecaceae is a family of perennial flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are called palm trees ...

industry, but also administering the affairs of the island from Sydney until the present Lord Howe Island Board was set up in 1954.

The Lord Howe Island Board

The Lord Howe Island Board is a NSW Statutory Authority established under the ''Lord Howe Island Act, 1953'', to administer Lord Howe Island, an unincorporated island territory within the jurisdiction of the State of New South Wales, Australia, ...

is a NSW Statutory Authority established under the Lord Howe Island Act 1953, to administer the island as part of the state of New South Wales. It reports directly to the state's Minister for Environment and Heritage, and is responsible for the care, control, and management of the island. Its duties include the protection of World Heritage

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for h ...

values; the control of development; the administration of Crown Land, including the island's protected area; provision of community services and infrastructure; and regulating sustainable tourism

Sustainable tourism is a concept that covers the complete tourism experience, including concern for economic, social and environmental issues as well as attention to improving tourists' experiences and addressing the needs of host communities. Su ...

. In 1981, the Lord Howe Island Amendment Act gave islanders the administrative power of three members on a five-member board. The board also manages the Lord Howe Island kentia palm nursery, which together with tourism, provides the island's only sources of external income. Under an amendment bill in 2004, the board now comprises seven members, four of whom are elected from the islander community, thus giving about 350 permanent residents a high level of autonomy. The remaining three members are appointed by the minister to represent the interests of business, tourism, and conservation. The full board meets on the island every three months, while the day-to-day affairs of the island are managed by the board's administration, with a permanent staff that had increased to 22 people by 1988.

Land tenure

In common law systems, land tenure, from the French verb "tenir" means "to hold", is the legal regime in which land owned by an individual is possessed by someone else who is said to "hold" the land, based on an agreement between both individual ...

has been an issue since first settlement, as island residents repeatedly requested freehold title

In English law, a fee simple or fee simple absolute is an estate in land, a form of freehold ownership. A "fee" is a vested, inheritable, present possessory interest in land. A "fee simple" is real property held without limit of time (i.e., per ...

or an absolute gift of cultivated land. Original settlers were squatters

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there ...

. The granting of a lease to Richard Armstrong in 1878 drew complaints, and a few short-term leases ("permissive occupancies") were granted. In 1913, with the appointment of a board of control, permissive occupancies were revoked and the board itself given permissive occupancy of the island. Then the Lord Howe Island Act 1953 made all land the property of the Crown. Direct descendants of islanders with permissive occupancies in 1913 were granted perpetual leases on blocks up to for residential purposes. Short-term special leases were granted for larger areas used for agriculture, so in 1955, 55 perpetual leases and 43 special leases were granted. The 1981 amendment to the act extended political and land rights to all residents of 10 years or more. An active debate exists concerning the proportion of residents with tenure and the degree of influence on the board of resident islanders in relation to long-term planning for visitors, and issues relating to the environment, amenity, and global heritage.

Parliamentary representation

New South Wales

As a dependency of theColony of New South Wales

The Colony of New South Wales was a colony of the British Empire from 1788 to 1901, when it became a State of the Commonwealth of Australia. At its greatest extent, the colony of New South Wales included the present-day Australian states of New ...

, Lord Howe Island was not represented in parliament until the 1894 New South Wales colonial election following the passage of the Parliamentary Electorates and Elections Act, 1893

'. Since 1894, Lord Howe Island has been included in the following

New South Wales Legislative Assembly

The New South Wales Legislative Assembly is the lower of the two houses of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The upper house is the New South Wales Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament Ho ...

districts:

As part of the redistribution of electoral districts for the 2023 state election, a proposal was received to move Lord Howe Island back into the electorate of Sydney. However, the NSW Electoral Commission

The New South Wales Electoral Commission is a statutory agency with responsibility for the administration, organisation, and supervision of elections in New South Wales. It reports to the Government of New South Wales, NSW Government Departmen ...

eventually decided to retain the island within the electorate of Port Macquarie.

Commonwealth

Since 1901, Lord Howe Island has been included in the followingAustralian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is the lower house of the bicameral Parliament of Australia, the upper house being the Senate. Its composition and powers are established in Chapter I of the Constitution of Australia.

The term of members of the ...

electoral divisions:

Economy

Kentia palm industry

The first exporter ofpalm seed

The Arecaceae is a family of perennial flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are called palm trees ...

s was Ned King, a mountain guide for the Fitzgerald surveys of 1869 and 1876, who sent seed to the Sydney Botanic Gardens. Overseas trade began in the 1880s, when one of the four palms endemic to the island, the kentia palm (''Howea forsteriana

''Howea forsteriana'', the Kentia palm, thatch palm or palm court palm, is a species of flowering plant in the palm family, Arecaceae, endemic to Lord Howe Island in Australia. It is also widely grown on Norfolk Island. It is a relatively slow-g ...

''), which grows naturally in the lowlands, was found to be ideally suited to the fashionable conservatories of the well-to-do in Britain, Europe, and the United States,. The assistance of mainland magistrate, Frank Farnell, was needed to put the business on a sound commercial footing when in 1906, he became company director of the Lord Howe Island Kentia Palm Nursery, whose shareholders included 21 islanders and a Sydney-based seed company. However, the formation of the Lord Howe Island Board of Control was needed in 1913 to resolve outstanding issues.

The kentia palm (known locally as the thatch palm, as it was used to roof the houses of the early settlers) is popular worldwide as decorative palm that grows well both outdoors (in sufficiently warm climates) and indoors; the mild climate of the island has led to the evolution of a palm that can tolerate low light, a dry atmosphere and lowish temperatures — ideal for indoor conditions, particularly in higher-end venues such as hotel lobbies, galleries and large foyers where their high price (thanks to their relative rarity) is no disincentive to their use. Up until the 1980s the palms were only sold as seed but from then onwards only as high quality seedlings. The nursery received certification in 1997 for its high quality management complying with the requirements of Australian Standard

Standards Australia is a standards organisation established in 1922 and is recognised through a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the Australian government as the primary non-government standards development body in Australia. It is a c ...

AS/NZS ISO 9002.

Seed is gathered from both natural forest and plantations, most collectors being descendants of the original settlers. The seed is then germinated in soilless media and sealed from the atmosphere to prevent contamination. After testing, seedlings are picked, washed (bare-rooted), sanitized and certified, then packed and sealed into insulated containers for export. Nursery profits, in turn, are used in projects that enhance the island's ecosystems. The nursery plans to expand the business to include the curly palm (''Howea belmoreana'') and other native plants of special interest.

By the late 1980s, annual exports had begun to provide a revenue of over A$2 million, constituting the only major industry on the island apart from tourism.

Tourism

Lord Howe Island is known for its geology, birds, plants, and marine life. Popular tourist activities include

Lord Howe Island is known for its geology, birds, plants, and marine life. Popular tourist activities include scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chris ...

, birdwatching, snorkelling

Snorkeling ( British and Commonwealth English spelling: snorkelling) is the practice of swimming on or through a body of water while equipped with a diving mask, a shaped breathing tube called a snorkel, and usually swimfins. In cooler waters, ...

, surfing

Surfing is a surface water sport in which an individual, a surfer (or two in tandem surfing), uses a board to ride on the forward section, or face, of a moving wave of water, which usually carries the surfer towards the shore. Waves suitabl ...

, kayaking

Kayaking is the use of a kayak for moving over water. It is distinguished from canoeing by the sitting position of the paddler and the number of blades on the paddle. A kayak is a low-to-the-water, canoe-like boat in which the paddler sits fac ...

, and fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

. To relieve pressure on the small island environment, only 400 tourists are permitted at any one time. The island is reached by plane from Sydney Airport

Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport (colloquially Mascot Airport, Kingsford Smith Airport, or Sydney Airport; ; ) is an international airport in Sydney, Australia, located 8 km (5 mi) south of the Sydney central business district, in the ...

or Brisbane Airport

Brisbane Airport is the primary international airport serving Brisbane and South East Queensland. The airport services 31 airlines flying to 50 domestic and 29 international destinations, in total amounting to more than 22.7 million passeng ...

in less than two hours. The Permanent Park Preserve declared in 1981 has similar management guidelines to a national park

A national park is a nature park, natural park in use for conservation (ethic), conservation purposes, created and protected by national governments. Often it is a reserve of natural, semi-natural, or developed land that a sovereign state dec ...

.

Facilities

With fewer than 800 people on the island at any time, facilities are limited; they include a bakery, butcher, general store, liquor store, restaurants, post office, museum, and information centre, a police officer, a ranger, and an ATM at the bowling club. Stores are shipped to the island fortnightly by the ''Island Trader'' from Port Macquarie. The island has a small four-bed hospital and dispensary. A small botanic garden displays labelled local plants in its grounds. Diesel-generated power is 240 volts AC, complemented by 1.3 MW solar power and 3.7 MWhbattery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

. No public transport or mobile phone coverage is available, but public telephones, fax facilities, and internet access are, as well as a local radio station and newsletter, ''The Signal''.

Tourist accommodation ranges from luxury lodges to apartments and villa units. The currency is the Australian dollar, and there are two banks. No camping facilities are on the island and remote-area camping is not permitted. To protect the fragile environment of Ball's Pyramid (which carries the last remaining wild population of the endangered Lord Howe Island stick insect), recreational climbing there is prohibited. No pets are allowed without permission from the board. Islanders use tanked rain

Rain is water droplets that have condensed from atmospheric water vapor and then fall under gravity. Rain is a major component of the water cycle and is responsible for depositing most of the fresh water on the Earth. It provides water f ...

water, supplemented by bore water for showers and washing clothes.

Activities

As distances to sites of interest are short,

As distances to sites of interest are short, cycling

Cycling, also, when on a two-wheeled bicycle, called bicycling or biking, is the use of cycles for transport, recreation, exercise or sport. People engaged in cycling are referred to as "cyclists", "bicyclists", or "bikers". Apart from two ...

is the main means of transport on the island. Tourist activities include golf

Golf is a club-and-ball sport in which players use various clubs to hit balls into a series of holes on a course in as few strokes as possible.

Golf, unlike most ball games, cannot and does not use a standardized playing area, and coping wi ...

(9-hole), lawn bowls

Bowls, also known as lawn bowls or lawn bowling, is a sport in which the objective is to roll biased balls so that they stop close to a smaller ball called a "jack" or "kitty". It is played on a bowling green, which may be flat (for "flat-gre ...

, tennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent ( singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball ...

, fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

(including deep-sea game fishing), yachting

Yachting is the use of recreational boats and ships called ''yachts'' for racing or cruising. Yachts are distinguished from working ships mainly by their leisure purpose. "Yacht" derives from the Dutch word '' jacht'' ("hunt"). With sailboats, t ...

, windsurfing

Windsurfing is a wind propelled water sport that is a combination of sailing and surfing. It is also referred to as "sailboarding" and "boardsailing", and emerged in the late 1960s from the aerospace and surf culture of California. Windsurfing ga ...

, kitesurfing

Kiteboarding or kitesurfing is a sport that involves using wind power with a large power kite to pull a rider across a water, land, or snow surface. It combines aspects of paragliding, surfing, windsurfing, skateboarding, snowboarding, and wak ...

, kayaking

Kayaking is the use of a kayak for moving over water. It is distinguished from canoeing by the sitting position of the paddler and the number of blades on the paddle. A kayak is a low-to-the-water, canoe-like boat in which the paddler sits fac ...

, and boat trips (including glass-bottom tours of the lagoon). Swimming, snorkelling

Snorkeling ( British and Commonwealth English spelling: snorkelling) is the practice of swimming on or through a body of water while equipped with a diving mask, a shaped breathing tube called a snorkel, and usually swimfins. In cooler waters, ...

, and scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chris ...

are also popular in the lagoon, as well as off Tenth of June Island, a small rocky outcrop in the Admiralty group where an underwater plateau

An oceanic or submarine plateau is a large, relatively flat elevation that is higher than the surrounding relief with one or more relatively steep sides.

There are 184 oceanic plateaus in the world, covering an area of or about 5.11% of the ...

drops to reveal extensive gorgonia

''Gorgonia'' is a genus of soft corals, sea fans in the family Gorgoniidae.

Species

The World Register of Marine Species lists these species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organi ...

and black coral

Antipatharians, also known as black corals or thorn corals, are an order of soft deep-water corals. These corals can be recognized by their jet-black or dark brown chitin skeletons, surrounded by the polyps (part of coral that is alive). Antipat ...

s growing on the vertical walls. Other diving sites are found off Ball's Pyramid, away, where trenches, caves, and volcanic drop-offs occur.

Bushwalking, natural history tours, talks, and guided walks take place along the many tracks, the most challenging being the eight-hour guided hike to the top of Mount Gower. The island has 11 beaches, and hand-feeding the kingfish (''Seriola lalandi'') and large wrasse

The wrasses are a family, Labridae, of marine fish, many of which are brightly colored. The family is large and diverse, with over 600 species in 81 genera, which are divided into 9 subgroups or tribes.

They are typically small, most of them le ...

at Ned's Beach is very popular. Walking tracks cover the island with difficulty graded from 1–5, they include—in the north: Transit Hill 2-hour return, ; Clear Place, 1– to 2-hour return; Stevens Reserve; North Bay, 4-hour return, ; Mount Eliza; Old Gulch, 20-minute return, ; Malabar Hill and Kims Lookout, 3 or 5-hour return, and—in the south: Goat House Cave, 5-hour return, ; Mount Gower, 8-hour return, ; Rocky Run and Boat Harbour; Intermediate Hill, 45-minute return, ; and Little Island, 40-minute return, . Recreational climbers must obtain permission from the Lord Howe Island Board.

Geography

Lord Howe Island is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Lying in the

Lord Howe Island is an irregularly crescent-shaped volcanic remnant in the southwest Pacific Ocean. Lying in the Tasman Sea

The Tasman Sea (Māori: ''Te Tai-o-Rēhua'', ) is a marginal sea of the South Pacific Ocean, situated between Australia and New Zealand. It measures about across and about from north to south. The sea was named after the Dutch explorer Abe ...

between Australia and New Zealand, the island is east of mainland Port Macquarie

Port Macquarie is a coastal town in the local government area of Port Macquarie-Hastings. It is located on the Mid North Coast of New South Wales, Australia, about north of Sydney, and south of Brisbane. The town is located on the Tasman Sea co ...

, northeast of Sydney, and about from Norfolk Island to its northeast. The island is about long and between wide with an area of . Along the west coast is a semienclosed, sheltered coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in groups.

Co ...

lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') a ...

with white sand, the most accessible of the island's 11 beaches.

Both the north and south sections of the island are high ground of relatively untouched forest, in the south comprising two

Both the north and south sections of the island are high ground of relatively untouched forest, in the south comprising two volcanic mountains

A volcano is a rupture in the crust of a planetary-mass object, such as Earth, that allows hot lava, volcanic ash, and gases to escape from a magma chamber below the surface.

On Earth, volcanoes are most often found where tectonic plates are ...

, Mount Lidgbird

Mount Lidgbird, also Mount Ledgbird and Big Hill, is located in the southern section of Lord Howe Island, just north of Mount Gower, from which it is separated by the saddle at the head of Erskine Valley, and has its peak at above sea level.

...

() and Mount Gower

Mount Gower (also known as Big Hill), is the highest mountain on Australia's subtropical Lord Howe Island in the Tasman Sea. With a height of above sea level, and a relatively flat summit plateau, it stands at the southern end of Lord Howe, jus ...

which, rising to , is the highest point on the island. The two mountains are separated by the saddle

The saddle is a supportive structure for a rider of an animal, fastened to an animal's back by a girth. The most common type is equestrian. However, specialized saddles have been created for oxen, camels and other animals. It is not kno ...

at the head of Erskine Valley. In the north, where most of the population live, high points are Malabar () and Mount Eliza (). Between these two uplands is an area of cleared lowland with some farming, the airstrip, and housing.

The Lord Howe Island Group of islands comprises 28 islands, islets, and rocks. Apart from Lord Howe Island itself, the most notable of these is the pointed rocky islet Balls Pyramid, a eroded volcano about to the southeast, which is uninhabited by humans but bird-colonised. It contains the only known wild population of the Lord Howe Island stick insect, formerly thought to be extinct. To the north is the Admiralty Group

The Admiralty Group of islets consists of eight rocky outcrops within 2 km of the north of Lord Howe Island. From south to north, these are:

#Soldier’s Cap

#Sugarloaf

#South Island

#Noddy

#Roach Island

#Tenth of June

#North Rock

#Flat Rock

...

, a cluster of seven small, uninhabited islands. Just off the east coast is Mutton Bird Island, and in the lagoon is the Blackburn (Rabbit) Island.

Geological origins

Lord Howe Island is the highly eroded remains of a 7-million-year-old

Lord Howe Island is the highly eroded remains of a 7-million-year-old shield volcano

A shield volcano is a type of volcano named for its low profile, resembling a warrior's shield lying on the ground. It is formed by the eruption of highly fluid (low viscosity) lava, which travels farther and forms thinner flows than the more v ...

, the product of eruptions that lasted for about 500,000 years. It is one of a chain of islands that occur on the western rim of an undersea shelf, the Lord Howe Rise

The Lord Howe Rise is a deep sea plateau which extends from south west of New Caledonia to the Challenger Plateau, west of New Zealand in the south west of the Pacific Ocean. To its west is the Tasman Basin and to the east is the New Caledonia ...

, which is long and wide extending from New Zealand to the west of New Caledonia and consisting of continental rocks that separated from the Australian plate 60 to 80 million years ago to form a new crust in the deep Tasman Basin

Tasman most often refers to Abel Tasman (1603–1659), Dutch explorer.

Tasman may also refer to:

Animals and plants

* Tasman booby

* Tasman flax-lily

* Tasman parakeet (disambiguation)

* Tasman starling

* Tasman whale

People

* Tasman ( ...

. The shelf is part of Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as (Māori) or Tasmantis, is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust that subsided after breaking away from Gondwanaland 83–79 million years ago.Gurnis, M., Hall, C.E., and Lavier, L.L., ...

, a microcontinent

Continental crustal fragments, partly synonymous with microcontinents, are pieces of continents that have broken off from main continental masses to form distinct islands that are often several hundred kilometers from their place of origin.

Caus ...

nearly half the size of Australia that gradually submerged after breaking away from the Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final stages ...

n supercontinent. The Lord Howe Seamount Chain

The Lord Howe Seamount Chain formed during the Miocene. It features many coral-capped guyots and is one of the two parallel seamount chains alongside the east coast of Australia; the Lord Howe and Tasmantid seamount chains both run north-south t ...

is defined by coral-capped guyot

In marine geology, a guyot (pronounced ), also known as a tablemount, is an isolated underwater volcanic mountain ( seamount) with a flat top more than below the surface of the sea. The diameters of these flat summits can exceed .Middleton ( away) and

Two periods of volcanic activity produced the major features of the island. The first about 6.9 million years (Mya) ago produced the northern and central hills, while the younger and highly eroded Mount Gower and Mount Lidgbird were produced about 6.3 Mya by successive

Two periods of volcanic activity produced the major features of the island. The first about 6.9 million years (Mya) ago produced the northern and central hills, while the younger and highly eroded Mount Gower and Mount Lidgbird were produced about 6.3 Mya by successive

Rocks and land at the foot of these mountains is

Rocks and land at the foot of these mountains is

Lord Howe Island is a distinct terrestrial

Lord Howe Island is a distinct terrestrial  The high degree of endemism is emphasised by the presence of five endemic genera: ''

The high degree of endemism is emphasised by the presence of five endemic genera: ''

Plant communities have been classified into nine categories: lowland subtropical rainforest, submontane rainforest, cloud-forest and scrub, lowland swamp forest, mangrove scrub and seagrass, coastal scrub and cliff vegetation, inland scrub and herbland, offshore island vegetation, shoreline and beach vegetation, and disturbed vegetation.

Several plants are immediately evident to the visitor. Banyan (''

Plant communities have been classified into nine categories: lowland subtropical rainforest, submontane rainforest, cloud-forest and scrub, lowland swamp forest, mangrove scrub and seagrass, coastal scrub and cliff vegetation, inland scrub and herbland, offshore island vegetation, shoreline and beach vegetation, and disturbed vegetation.

Several plants are immediately evident to the visitor. Banyan (''

A total of 202 different birds have been recorded on the island. Eighteen species of land birds breed on the island and many more migratory species occur on the island and its adjacent islets, many tame enough that humans can get quite close. The island has been identified by

A total of 202 different birds have been recorded on the island. Eighteen species of land birds breed on the island and many more migratory species occur on the island and its adjacent islets, many tame enough that humans can get quite close. The island has been identified by  The flesh-footed shearwater, which breeds in large numbers on the main island in spring-autumn, once had its chicks harvested for food by the islanders. The wedge-tailed and

The flesh-footed shearwater, which breeds in large numbers on the main island in spring-autumn, once had its chicks harvested for food by the islanders. The wedge-tailed and

*

*

Only one native

Only one native

The Lord Howe Island stick insect disappeared from the main island soon after the accidental introduction of rats when the SS ''Makambo'' ran aground near Ned's Beach on 15 June 1918. In 2001, a tiny population was discovered in a single ''