Liesegang Sandstein ReiKi Cropped on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Liesegang rings () are a phenomenon seen in many, if not most, chemical systems undergoing a

Liesegang rings () are a phenomenon seen in many, if not most, chemical systems undergoing a

Several different theories have been proposed to explain the formation of Liesegang rings. The chemist

Several different theories have been proposed to explain the formation of Liesegang rings. The chemist

It can account for several important features sometimes seen, such as revert and helical banding.

"Ueber einige Eigenschaften von Gallerten"

Naturwissenschaftliche Wochenschrift, Vol. 11, Nr. 30, 353-362 (1896). * J.A. Pask and C.W. Parmelee, "Study of Diffusion in Glass," Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Vol. 26, Nr. 8, 267-277 (1943). *K. H. Stern, ''The Liesegang Phenomenon'' Chem. Rev. 54, 79-99 (1954). *Ernest S. Hedges, ''Liesegang Rings and other Periodic Structures'' Chapman and Hall (1932).

A Thesis having a summary on reaction-diffusion processes and Liesegang banding (pp. 1-36)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Liesegang Rings Chemical reactions Diffusion Petrology concepts Physical chemistry Thermodynamics Articles containing video clips

Liesegang rings () are a phenomenon seen in many, if not most, chemical systems undergoing a

Liesegang rings () are a phenomenon seen in many, if not most, chemical systems undergoing a precipitation reaction

In an aqueous solution, precipitation is the process of transforming a dissolved substance into an insoluble solid from a super-saturated solution. The solid formed is called the precipitate. In case of an inorganic chemical reaction leading ...

under certain conditions of concentration

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', ''molar concentration'', ''number concentration'', an ...

and in the absence of convection

Convection is single or multiphase fluid flow that occurs spontaneously due to the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoyancy). When the cause of the convec ...

. Rings are formed when weakly soluble

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

The extent of the solubil ...

salts

In chemistry, a salt is a chemical compound consisting of an ionic assembly of positively charged cations and negatively charged anions, which results in a compound with no net electric charge. A common example is table salt, with positively cha ...

are produced from reaction of two soluble substances, one of which is dissolved in a gel

A gel is a semi-solid that can have properties ranging from soft and weak to hard and tough. Gels are defined as a substantially dilute cross-linked system, which exhibits no flow when in the steady-state, although the liquid phase may still dif ...

medium. The phenomenon is most commonly seen as rings in a Petri dish

A Petri dish (alternatively known as a Petri plate or cell-culture dish) is a shallow transparent lidded dish that biologists use to hold growth medium in which cells can be cultured,R. C. Dubey (2014): ''A Textbook Of Biotechnology For Class- ...

or bands in a test tube

A test tube, also known as a culture tube or sample tube, is a common piece of laboratory glassware consisting of a finger-like length of glass or clear plastic tubing, open at the top and closed at the bottom.

Test tubes are usually placed in s ...

; however, more complex patterns have been observed, such as dislocations of the ring structure in a Petri dish, helices

A helix () is a shape like a corkscrew or spiral staircase. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is formed as two intertwined helices, ...

, and " Saturn rings" in a test tube. Despite continuous investigation since rediscovery of the rings in 1896, the mechanism for the formation of Liesegang rings is still unclear.

History

The phenomenon was first noticed in 1855 by the German chemistFriedlieb Ferdinand Runge

Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge (8 February 1794 – 25 March 1867) was a German analytical chemist. Runge identified the mydriatic (pupil dilating) effects of belladonna (deadly nightshade) extract, identified caffeine, and discovered the first coal ...

. He observed them in the course of experiments on the precipitation of reagents in blotting paper

Blotting paper, called bibulous paper, is a highly absorbent type of paper or other material. It is used to absorb an excess of liquid substances (such as ink or oil) from the surface of writing paper or objects. Blotting paper referred to as b ...

. In 1896 the German chemist Raphael E. Liesegang noted the phenomenon when he dropped a solution of silver nitrate

Silver nitrate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula . It is a versatile precursor to many other silver compounds, such as those used in photography. It is far less sensitive to light than the halides. It was once called ''lunar caustic' ...

onto a thin layer of gel containing potassium dichromate

Potassium dichromate, , is a common inorganic chemical reagent, most commonly used as an oxidizing agent in various laboratory and industrial applications. As with all hexavalent chromium compounds, it is acutely and chronically harmful to health ...

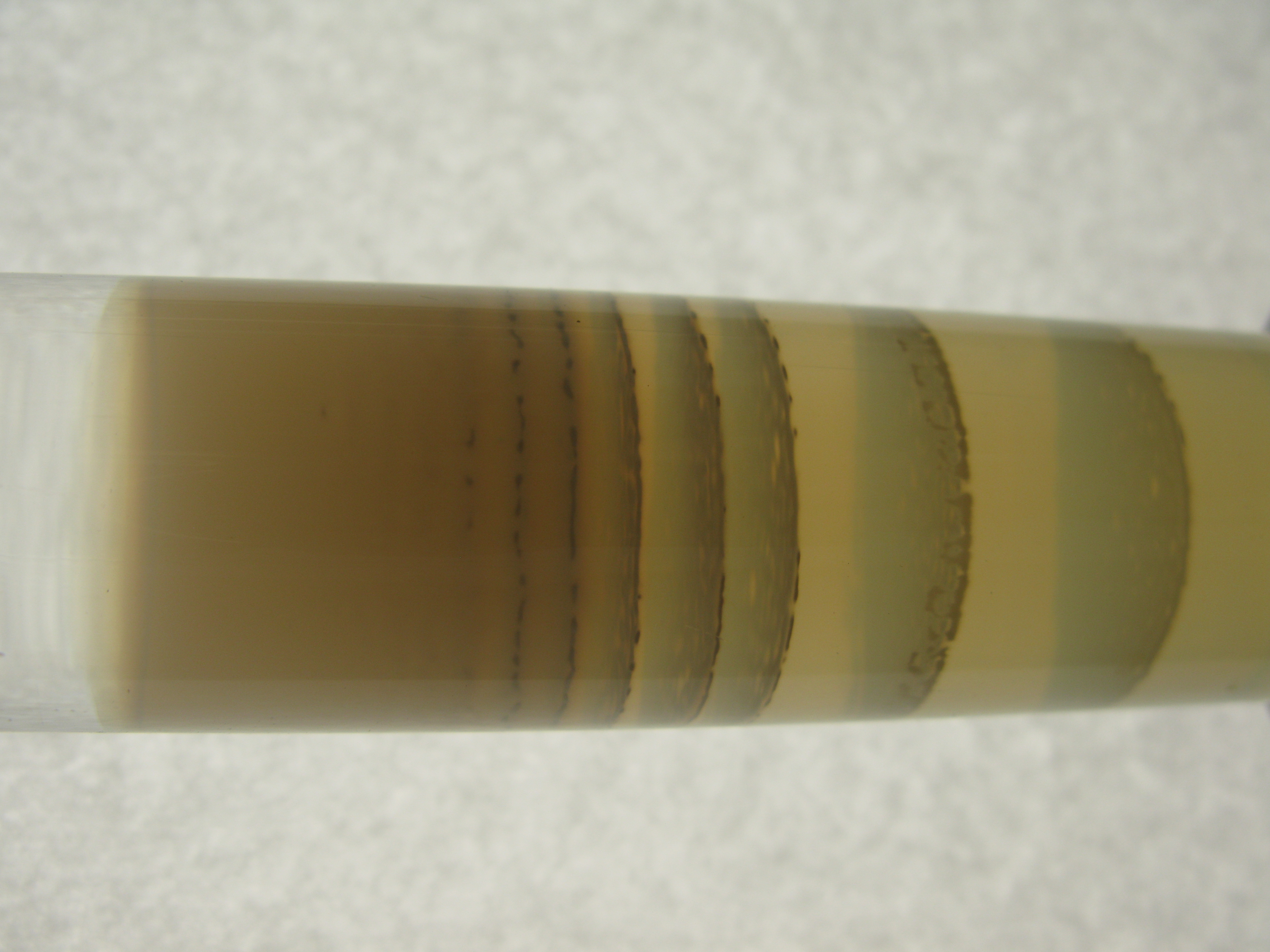

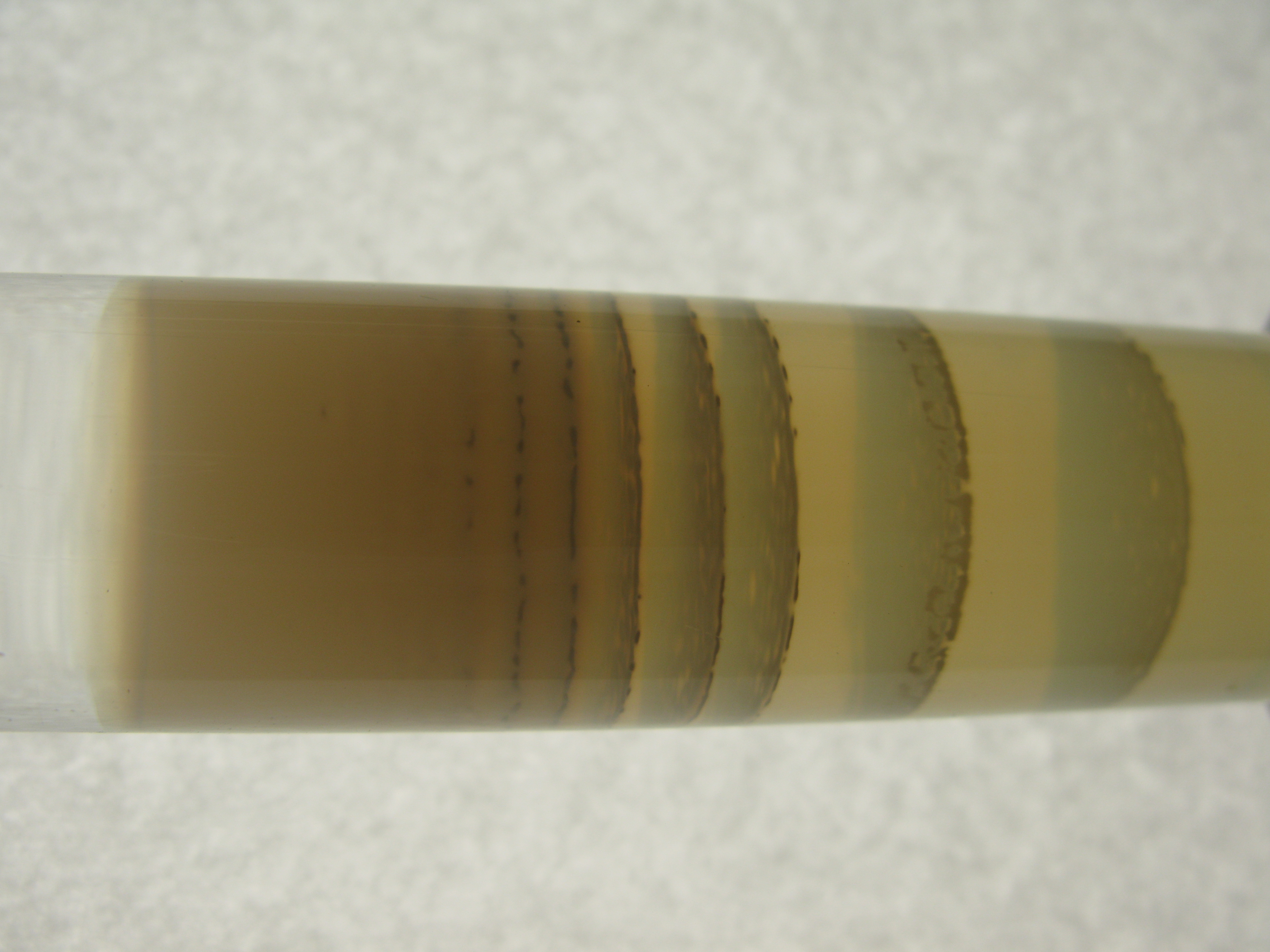

. After a few hours, sharp concentric rings of insoluble silver dichromate formed. It has aroused the curiosity of chemists for many years. When formed in a test tube by diffusing one component from the top, layers or bands of precipitate form, rather than rings.

Silver nitrate potassium dichromate reaction

The reactions are most usually carried out in test tubes into which agel

A gel is a semi-solid that can have properties ranging from soft and weak to hard and tough. Gels are defined as a substantially dilute cross-linked system, which exhibits no flow when in the steady-state, although the liquid phase may still dif ...

is formed that contains a dilute solution of one of the reactants.

If a hot solution of agar gel also containing a dilute solution of potassium dichromate

Potassium dichromate, , is a common inorganic chemical reagent, most commonly used as an oxidizing agent in various laboratory and industrial applications. As with all hexavalent chromium compounds, it is acutely and chronically harmful to health ...

is poured in a test tube, and after the gel solidifies a more concentrated solution of silver nitrate

Silver nitrate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula . It is a versatile precursor to many other silver compounds, such as those used in photography. It is far less sensitive to light than the halides. It was once called ''lunar caustic' ...

is poured on top of the gel, the silver nitrate will begin to diffuse into the gel. It will then encounter the potassium dichromate and will form a continuous region of precipitate at the top of the tube.

After some hours, the continuous region of precipitation is followed by a clear region with no sensible precipitate, followed by a short region of precipitate further down the tube. This process continues down the tube forming several, up to perhaps a couple dozen, alternating regions of clear gel and precipitate rings.

Some general observations

Over the decades huge number of precipitation reactions have been used to study the phenomenon, and it seems quite general.Chromates

Chromate salts contain the chromate anion, . Dichromate salts contain the dichromate anion, . They are oxyanions of chromium in the +6 oxidation state and are moderately strong oxidizing agents. In an aqueous solution, chromate and dichromate i ...

, metal hydroxides, carbonates

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate g ...

, and sulfides

Sulfide (British English also sulphide) is an inorganic anion of sulfur with the chemical formula S2− or a compound containing one or more S2− ions. Solutions of sulfide salts are corrosive. ''Sulfide'' also refers to chemical compounds la ...

, formed with lead, copper, silver, mercury and cobalt salts are sometimes favored by investigators, perhaps because of the pretty, colored precipitates formed.

The gels used are usually gelatin

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

, agar

Agar ( or ), or agar-agar, is a jelly-like substance consisting of polysaccharides obtained from the cell walls of some species of red algae, primarily from ogonori (''Gracilaria'') and "tengusa" (''Gelidiaceae''). As found in nature, agar is ...

or silicic acid

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one ...

gel.

The concentration ranges over which the rings form in a given gel for a precipitating system can usually be found for any system by a little systematic empirical experimentation in a few hours. Often the concentration of the component in the agar gel should be substantially less concentrated (perhaps an order of magnitude or more) than the one placed on top of the gel.

The first feature usually noted is that the bands which form farther away from the liquid-gel interface are generally farther apart. Some investigators measure this distance and report in some systems, at least, a systematic formula for the distance that they form at. The most frequent observation is that the distance apart that the rings form is proportional to the distance from the liquid-gel interface. This is by no means universal, however, and sometimes they form at essentially random, irreproducible distances.

Another feature often noted is that the bands themselves do not move with time, but rather form in place and stay there.

For very many systems the precipitate that forms is not the fine coagulant or flocs seen on mixing the two solutions in the absence of the gel, but rather coarse, crystalline dispersions. Sometimes the crystals are well separated from one another, and only a few form in each band.

The precipitate that forms a band is not always a binary insoluble compound, but may be even a pure metal. Water glass

Sodium silicate is a generic name for chemical compounds with the formula or ·, such as sodium metasilicate , sodium orthosilicate , and sodium pyrosilicate . The anions are often polymeric. These compounds are generally colorless transparent ...

of density 1.06 made acidic by sufficient acetic acid

Acetic acid , systematically named ethanoic acid , is an acidic, colourless liquid and organic compound with the chemical formula (also written as , , or ). Vinegar is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main component ...

to make it gel, with 0.05 N copper sulfate Copper sulfate may refer to:

* Copper(II) sulfate, CuSO4, a common compound used as a fungicide and herbicide

* Copper(I) sulfate

Copper(I) sulfate, also known as cuprous sulfate, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula Cu2 SO4. It ...

in it, covered by a 1 percent solution of hydroxylamine hydrochloride

Hydroxylammonium chloride is the hydrochloric acid salt of hydroxylamine. Hydroxylamine is a biological intermediate in nitrification (biological oxidation of ammonia with oxygen into nitrite) and in anammox (biological oxidation of nitrite and am ...

produces large tetrahedrons of metallic copper in the bands.

It is not possible to make any general statement of the effect of the composition of the gel. A system that forms nicely for one set of components, might fail altogether and require a different set of conditions if the gel is switched, say, from agar to gelatin. The essential feature of the gel required is that thermal convection in the tube be prevented altogether.

Most systems will form rings in the absence of the gelling system if the experiment is carried out in a capillary, where convection does not disturb their formation. In fact, the system does not have to even be liquid. A tube plugged with cotton with a little ammonium hydroxide at one end, and a solution of hydrochloric acid at the other will show rings of deposited ammonium chloride where the two gases meet, if the conditions are chosen correctly. Ring formation has also been observed in solid glasses containing a reducible species. For example, bands of silver have been generated by immersing silicate glass in molten AgNO3 for extended periods of time (Pask and Parmelee, 1943).

Theories

Several different theories have been proposed to explain the formation of Liesegang rings. The chemist

Several different theories have been proposed to explain the formation of Liesegang rings. The chemist Wilhelm Ostwald

Friedrich Wilhelm Ostwald (; 4 April 1932) was a Baltic German chemist and German philosophy, philosopher. Ostwald is credited with being one of the founders of the field of physical chemistry, with Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, Walther Nernst, ...

in 1897 proposed a theory based on the idea that a precipitate is not formed immediately upon the concentration of the ions exceeding a solubility product, but a region of supersaturation

In physical chemistry, supersaturation occurs with a solution when the concentration of a solute exceeds the concentration specified by the value of solubility at equilibrium. Most commonly the term is applied to a solution of a solid in a liqu ...

occurs first. When the limit of stability of the supersaturation is reached, the precipitate forms, and a clear region forms ahead of the diffusion front because the precipitate that is below the solubility limit diffuses into the precipitate. This was argued to be a critically flawed theory when it was shown that seeding the gel with a colloidal dispersion of the precipitate (which would arguably prevent any significant region of supersaturation) did not prevent the formation of the rings.

Another theory focuses on the adsorption

Adsorption is the adhesion of atoms, ions or molecules from a gas, liquid or dissolved solid to a surface. This process creates a film of the ''adsorbate'' on the surface of the ''adsorbent''. This process differs from absorption, in which a f ...

of one or the other of the precipitating ions onto the colloidal particles of the precipitate which forms. If the particles are small, the absorption is large, diffusion is "hindered" and this somehow results in the formation of the rings.

Still another proposal, the "coagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It potentially results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The mechanism o ...

theory" states that the precipitate first forms as a fine colloidal dispersion, which then undergoes coagulation by an excess of the diffusing electrolyte and this somehow results in the formation of the rings.

Some more recent theories invoke an auto-catalytic step in the reaction that results in the formation of the precipitate. This would seem to contradict the notion that auto-catalytic reactions are, actually, quite rare in nature.

The solution of the diffusion equation

The diffusion equation is a parabolic partial differential equation. In physics, it describes the macroscopic behavior of many micro-particles in Brownian motion, resulting from the random movements and collisions of the particles (see Fick's la ...

with proper boundary conditions, and a set of good assumptions on supersaturation, adsorption, auto-catalysis, and coagulation alone, or in some combination, has not been done yet, it appears, at least in a way that makes a quantitative comparison with experiment possible. However, a theoretical approach for the Matalon-Packter law predicting the position of the precipitate bands when the experiments are performed in a test tube, has been provided

A general theory based on Ostwald's 1897 theory has recently been proposeIt can account for several important features sometimes seen, such as revert and helical banding.

References

*Liesegang, R. E"Ueber einige Eigenschaften von Gallerten"

Naturwissenschaftliche Wochenschrift, Vol. 11, Nr. 30, 353-362 (1896). * J.A. Pask and C.W. Parmelee, "Study of Diffusion in Glass," Journal of the American Ceramic Society, Vol. 26, Nr. 8, 267-277 (1943). *K. H. Stern, ''The Liesegang Phenomenon'' Chem. Rev. 54, 79-99 (1954). *Ernest S. Hedges, ''Liesegang Rings and other Periodic Structures'' Chapman and Hall (1932).

External links

A Thesis having a summary on reaction-diffusion processes and Liesegang banding (pp. 1-36)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Liesegang Rings Chemical reactions Diffusion Petrology concepts Physical chemistry Thermodynamics Articles containing video clips