lizard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lizard is the common name used for all

Lizards typically have rounded torsos, elevated heads on short necks, four limbs and long tails, although some are legless. Lizards and snakes share a movable quadrate bone, distinguishing them from the rhynchocephalians, which have more rigid diapsid skulls. Some lizards such as chameleons have prehensile tails, assisting them in climbing among vegetation.

As in other reptiles, the skin of lizards is covered in overlapping scales made of keratin. This provides protection from the environment and reduces water loss through evaporation. This adaptation enables lizards to thrive in some of the driest deserts on earth. The skin is tough and leathery, and is shed (sloughed) as the animal grows. Unlike snakes which shed the skin in a single piece, lizards slough their skin in several pieces. The scales may be modified into spines for display or protection, and some species have bone osteoderms underneath the scales.

Lizards typically have rounded torsos, elevated heads on short necks, four limbs and long tails, although some are legless. Lizards and snakes share a movable quadrate bone, distinguishing them from the rhynchocephalians, which have more rigid diapsid skulls. Some lizards such as chameleons have prehensile tails, assisting them in climbing among vegetation.

As in other reptiles, the skin of lizards is covered in overlapping scales made of keratin. This provides protection from the environment and reduces water loss through evaporation. This adaptation enables lizards to thrive in some of the driest deserts on earth. The skin is tough and leathery, and is shed (sloughed) as the animal grows. Unlike snakes which shed the skin in a single piece, lizards slough their skin in several pieces. The scales may be modified into spines for display or protection, and some species have bone osteoderms underneath the scales.

The dentitions of lizards reflect their wide range of diets, including carnivorous, insectivorous, omnivorous, herbivorous, nectivorous, and molluscivorous. Species typically have uniform teeth suited to their diet, but several species have variable teeth, such as cutting teeth in the front of the jaws and crushing teeth in the rear. Most species are pleurodont, though agamids and chameleons are acrodont.

The tongue can be extended outside the mouth, and is often long. In the beaded lizards, whiptails and monitor lizards, the tongue is forked and used mainly or exclusively to sense the environment, continually flicking out to sample the environment, and back to transfer molecules to the vomeronasal organ responsible for chemosensation, analogous to but different from smell or taste. In geckos, the tongue is used to lick the eyes clean: they have no eyelids. Chameleons have very long sticky tongues which can be extended rapidly to catch their insect prey.

Three lineages, the

The dentitions of lizards reflect their wide range of diets, including carnivorous, insectivorous, omnivorous, herbivorous, nectivorous, and molluscivorous. Species typically have uniform teeth suited to their diet, but several species have variable teeth, such as cutting teeth in the front of the jaws and crushing teeth in the rear. Most species are pleurodont, though agamids and chameleons are acrodont.

The tongue can be extended outside the mouth, and is often long. In the beaded lizards, whiptails and monitor lizards, the tongue is forked and used mainly or exclusively to sense the environment, continually flicking out to sample the environment, and back to transfer molecules to the vomeronasal organ responsible for chemosensation, analogous to but different from smell or taste. In geckos, the tongue is used to lick the eyes clean: they have no eyelids. Chameleons have very long sticky tongues which can be extended rapidly to catch their insect prey.

Three lineages, the

Aside from legless lizards, most lizards are quadrupedal and move using

Aside from legless lizards, most lizards are quadrupedal and move using

Some lizards, particularly iguanas, have retained a photosensory organ on the top of their heads called the parietal eye, a basal ("primitive") feature also present in the

Some lizards, particularly iguanas, have retained a photosensory organ on the top of their heads called the parietal eye, a basal ("primitive") feature also present in the

Until 2006 it was thought that the Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard were the only venomous lizards. However, several species of monitor lizards, including the Komodo dragon, produce powerful venom in their oral

Until 2006 it was thought that the Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard were the only venomous lizards. However, several species of monitor lizards, including the Komodo dragon, produce powerful venom in their oral

As with all amniotes, lizards rely on internal fertilisation and copulation involves the male inserting one of his hemipenes into the female's

As with all amniotes, lizards rely on internal fertilisation and copulation involves the male inserting one of his hemipenes into the female's  In most lizards, the eggs have leathery shells to allow for the exchange of water, although more arid-living species have calcified shells to retain water. Inside the eggs, the embryos use nutrients from the

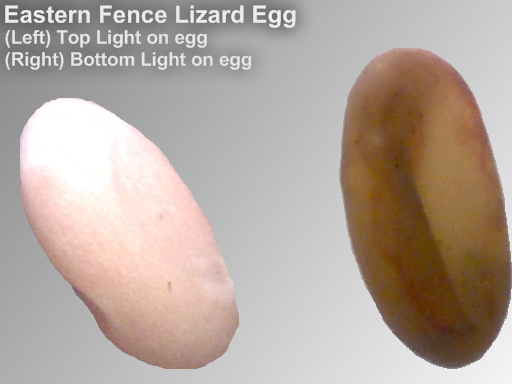

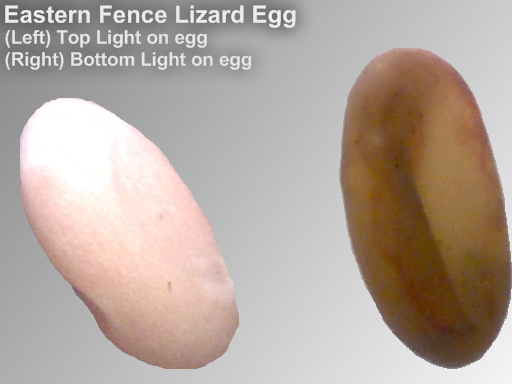

In most lizards, the eggs have leathery shells to allow for the exchange of water, although more arid-living species have calcified shells to retain water. Inside the eggs, the embryos use nutrients from the

Lizards signal both to attract mates and to intimidate rivals. Visual displays include body postures and inflation, push-ups, bright colours, mouth gapings and tail waggings. Male

Lizards signal both to attract mates and to intimidate rivals. Visual displays include body postures and inflation, push-ups, bright colours, mouth gapings and tail waggings. Male

The majority of lizard species are predatory and the most common prey items are small, terrestrial invertebrates, particularly

The majority of lizard species are predatory and the most common prey items are small, terrestrial invertebrates, particularly  Larger species, such as monitor lizards, can feed on larger prey including fish, frogs, birds, mammals and other reptiles. Prey may be swallowed whole and torn into smaller pieces. Both bird and reptile eggs may also be consumed as well. Gila monsters and beaded lizards climb trees to reach both the eggs and young of birds. Despite being venomous, these species rely on their strong jaws to kill prey. Mammalian prey typically consists of

Larger species, such as monitor lizards, can feed on larger prey including fish, frogs, birds, mammals and other reptiles. Prey may be swallowed whole and torn into smaller pieces. Both bird and reptile eggs may also be consumed as well. Gila monsters and beaded lizards climb trees to reach both the eggs and young of birds. Despite being venomous, these species rely on their strong jaws to kill prey. Mammalian prey typically consists of

Lizards have a variety of antipredator adaptations, including running and climbing,

Lizards have a variety of antipredator adaptations, including running and climbing,

Numerous species of lizard are kept as pets, including bearded dragons, iguanas,

Numerous species of lizard are kept as pets, including bearded dragons, iguanas,  Lizards such as the Gila monster produce toxins with medical applications. Gila toxin reduces plasma glucose; the substance is now synthesized for use in the anti-

Lizards such as the Gila monster produce toxins with medical applications. Gila toxin reduces plasma glucose; the substance is now synthesized for use in the anti-

squamate

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

s other than snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenia

Amphisbaenia (called amphisbaenians or worm lizards) is a group of typically legless lizards, comprising over 200 extant species. Amphisbaenians are characterized by their long bodies, the reduction or loss of the limbs, and rudimentary eyes. A ...

ns), encompassing over 7,000 species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

, ranging across all continents except Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

, as well as most oceanic island chains. The grouping is paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

as some lizards are more closely related to snakes than they are to other lizards. Lizards range in size from chameleons and gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates. They range from .

Geckos are unique among lizards ...

s a few centimeters long to the 3-meter-long Komodo dragon.

Most lizards are quadrupedal, running with a strong side-to-side motion. Some lineages (known as "legless lizard

Legless lizard may refer to any of several groups of lizards that have independently lost limbs or reduced them to the point of being of no use in locomotion.Pough ''et al.'' 1992. Herpetology: Third Edition. Pearson Prentice Hall:Pearson Education ...

s") have secondarily lost their legs, and have long snake-like bodies. Some lizards, such as the forest-dwelling '' Draco'', are able to glide. They are often territorial, the males fighting off other males and signalling, often with bright colours, to attract mates and to intimidate rivals. Lizards are mainly carnivorous, often being sit-and-wait predators; many smaller species eat insects, while the Komodo eats mammals as big as water buffalo

The water buffalo (''Bubalus bubalis''), also called domestic water buffalo, Asian water buffalo and Asiatic water buffalo, is a large bovid originating in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Today, it is also kept in Italy, the Balkans ...

.

Lizards make use of a variety of antipredator adaptations, including venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

, camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

, reflex bleeding, and the ability to sacrifice and regrow their tails.

Anatomy

Largest and smallest

The adult length of species within the suborder ranges from a few centimeters for chameleons such as '' Brookesia micra'' andgecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates. They range from .

Geckos are unique among lizards ...

s such as '' Sphaerodactylus ariasae'' to nearly in the case of the largest living varanid lizard, the Komodo dragon. Most lizards are fairly small animals.

Distinguishing features

Lizards typically have rounded torsos, elevated heads on short necks, four limbs and long tails, although some are legless. Lizards and snakes share a movable quadrate bone, distinguishing them from the rhynchocephalians, which have more rigid diapsid skulls. Some lizards such as chameleons have prehensile tails, assisting them in climbing among vegetation.

As in other reptiles, the skin of lizards is covered in overlapping scales made of keratin. This provides protection from the environment and reduces water loss through evaporation. This adaptation enables lizards to thrive in some of the driest deserts on earth. The skin is tough and leathery, and is shed (sloughed) as the animal grows. Unlike snakes which shed the skin in a single piece, lizards slough their skin in several pieces. The scales may be modified into spines for display or protection, and some species have bone osteoderms underneath the scales.

Lizards typically have rounded torsos, elevated heads on short necks, four limbs and long tails, although some are legless. Lizards and snakes share a movable quadrate bone, distinguishing them from the rhynchocephalians, which have more rigid diapsid skulls. Some lizards such as chameleons have prehensile tails, assisting them in climbing among vegetation.

As in other reptiles, the skin of lizards is covered in overlapping scales made of keratin. This provides protection from the environment and reduces water loss through evaporation. This adaptation enables lizards to thrive in some of the driest deserts on earth. The skin is tough and leathery, and is shed (sloughed) as the animal grows. Unlike snakes which shed the skin in a single piece, lizards slough their skin in several pieces. The scales may be modified into spines for display or protection, and some species have bone osteoderms underneath the scales.

The dentitions of lizards reflect their wide range of diets, including carnivorous, insectivorous, omnivorous, herbivorous, nectivorous, and molluscivorous. Species typically have uniform teeth suited to their diet, but several species have variable teeth, such as cutting teeth in the front of the jaws and crushing teeth in the rear. Most species are pleurodont, though agamids and chameleons are acrodont.

The tongue can be extended outside the mouth, and is often long. In the beaded lizards, whiptails and monitor lizards, the tongue is forked and used mainly or exclusively to sense the environment, continually flicking out to sample the environment, and back to transfer molecules to the vomeronasal organ responsible for chemosensation, analogous to but different from smell or taste. In geckos, the tongue is used to lick the eyes clean: they have no eyelids. Chameleons have very long sticky tongues which can be extended rapidly to catch their insect prey.

Three lineages, the

The dentitions of lizards reflect their wide range of diets, including carnivorous, insectivorous, omnivorous, herbivorous, nectivorous, and molluscivorous. Species typically have uniform teeth suited to their diet, but several species have variable teeth, such as cutting teeth in the front of the jaws and crushing teeth in the rear. Most species are pleurodont, though agamids and chameleons are acrodont.

The tongue can be extended outside the mouth, and is often long. In the beaded lizards, whiptails and monitor lizards, the tongue is forked and used mainly or exclusively to sense the environment, continually flicking out to sample the environment, and back to transfer molecules to the vomeronasal organ responsible for chemosensation, analogous to but different from smell or taste. In geckos, the tongue is used to lick the eyes clean: they have no eyelids. Chameleons have very long sticky tongues which can be extended rapidly to catch their insect prey.

Three lineages, the gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates. They range from .

Geckos are unique among lizards ...

s, anole

Dactyloidae are a family of lizards commonly known as anoles (singular anole ) and native to warmer parts of the Americas, ranging from southeastern United States to Paraguay. Instead of treating it as a family, some authorities prefer to treat ...

s, and chameleons, have modified the scales under their toes to form adhesive pads, highly prominent in the first two groups. The pads are composed of millions of tiny setae (hair-like structures) which fit closely to the substrate to adhere using van der Waals forces; no liquid adhesive is needed. In addition, the toes of chameleons are divided into two opposed groups on each foot ( zygodactyly), enabling them to perch on branches as birds do.

Physiology

Locomotion

gait

Gait is the pattern of Motion (physics), movement of the limb (anatomy), limbs of animals, including Gait (human), humans, during Animal locomotion, locomotion over a solid substrate. Most animals use a variety of gaits, selecting gait based on s ...

s with alternating movement of the right and left limbs with substantial body bending. This body bending prevents significant respiration during movement, limiting their endurance, in a mechanism called Carrier's constraint. Several species can run bipedally, and a few can prop themselves up on their hindlimbs and tail while stationary. Several small species such as those in the genus '' Draco'' can glide: some can attain a distance of , losing in height. Some species, like geckos and chameleons, adhere to vertical surfaces including glass and ceilings. Some species, like the common basilisk, can run across water.

Senses

Lizards make use of theirsense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditio ...

s of sight

Visual perception is the ability to detect light and use it to form an image of the surrounding Biophysical environment, environment. Photodetection without image formation is classified as ''light sensing''. In most vertebrates, visual percept ...

, touch, olfaction

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, ...

and hearing like other vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s. The balance of these varies with the habitat of different species; for instance, skinks that live largely covered by loose soil rely heavily on olfaction and touch, while geckos depend largely on acute vision for their ability to hunt and to evaluate the distance to their prey before striking. Monitor lizards have acute vision, hearing, and olfactory senses. Some lizards make unusual use of their sense organs: chameleons can steer their eyes in different directions, sometimes providing non-overlapping fields of view, such as forwards and backwards at once. Lizards lack external ears, having instead a circular opening in which the tympanic membrane (eardrum) can be seen. Many species rely on hearing for early warning of predators, and flee at the slightest sound.

As in snakes and many mammals, all lizards have a specialised olfactory system, the vomeronasal organ, used to detect pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s. Monitor lizards transfer scent from the tip of their tongue to the organ; the tongue is used only for this information-gathering purpose, and is not involved in manipulating food.

Some lizards, particularly iguanas, have retained a photosensory organ on the top of their heads called the parietal eye, a basal ("primitive") feature also present in the

Some lizards, particularly iguanas, have retained a photosensory organ on the top of their heads called the parietal eye, a basal ("primitive") feature also present in the tuatara

The tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') is a species of reptile endemic to New Zealand. Despite its close resemblance to lizards, it is actually the only extant member of a distinct lineage, the previously highly diverse order Rhynchocephal ...

. This "eye" has only a rudimentary retina and lens and cannot form images, but is sensitive to changes in light and dark and can detect movement. This helps them detect predators stalking it from above.

Venom

Until 2006 it was thought that the Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard were the only venomous lizards. However, several species of monitor lizards, including the Komodo dragon, produce powerful venom in their oral

Until 2006 it was thought that the Gila monster and the Mexican beaded lizard were the only venomous lizards. However, several species of monitor lizards, including the Komodo dragon, produce powerful venom in their oral gland

A gland is a Cell (biology), cell or an Organ (biology), organ in an animal's body that produces and secretes different substances that the organism needs, either into the bloodstream or into a body cavity or outer surface. A gland may also funct ...

s. Lace monitor venom, for instance, causes swift loss of consciousness and extensive bleeding through its pharmacological effects, both lowering blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of Circulatory system, circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term ...

and preventing blood clotting

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a thrombus, blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of co ...

. Nine classes of toxin

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

known from snakes are produced by lizards. The range of actions provides the potential for new medicinal drugs based on lizard venom protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s.

Genes associated with venom toxins have been found in the salivary glands of a wide range of lizards, including species traditionally thought of as non-venomous, such as iguanas and bearded dragons. This suggests that these genes evolved in the common ancestor of lizards and snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s, some 200 million years ago (forming a single clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

, the Toxicofera). However, most of these putative venom genes were "housekeeping genes" found in all cells and tissues, including skin and cloacal scent glands. The genes in question may thus be evolutionary precursors of venom genes.

Respiration

Recent studies (2013 and 2014) on the lung anatomy of the savannah monitor and green iguana found them to have a unidirectional airflow system, which involves the air moving in a loop through the lungs when breathing. This was previously thought to only exist in the archosaurs (crocodilian

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

s and bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s). This may be evidence that unidirectional airflow is an ancestral trait in diapsids.

Reproduction and life cycle

As with all amniotes, lizards rely on internal fertilisation and copulation involves the male inserting one of his hemipenes into the female's

As with all amniotes, lizards rely on internal fertilisation and copulation involves the male inserting one of his hemipenes into the female's cloaca

A cloaca ( ), : cloacae ( or ), or vent, is the rear orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive (rectum), reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles, birds, cartilagin ...

. Female lizards also have

hemiclitorises, a doubled

clitoris. The majority of species are oviparous

Oviparous animals are animals that reproduce by depositing fertilized zygotes outside the body (i.e., by laying or spawning) in metabolically independent incubation organs known as eggs, which nurture the embryo into moving offsprings kno ...

(egg laying). The female deposits the eggs in a protective structure like a nest or crevice or simply on the ground. Depending on the species, clutch size can vary from 4–5 percent of the females body weight to 40–50 percent and clutches range from one or a few large eggs to dozens of small ones.

In most lizards, the eggs have leathery shells to allow for the exchange of water, although more arid-living species have calcified shells to retain water. Inside the eggs, the embryos use nutrients from the

In most lizards, the eggs have leathery shells to allow for the exchange of water, although more arid-living species have calcified shells to retain water. Inside the eggs, the embryos use nutrients from the yolk

Among animals which produce eggs, the yolk (; also known as the vitellus) is the nutrient-bearing portion of the egg whose primary function is to supply food for the development of the embryo. Some types of egg contain no yolk, for example bec ...

. Parental care is uncommon and the female usually abandons the eggs after laying them. Brooding

Broodiness is the action or behavioral tendency to sit on a clutch of eggs to Egg incubation, incubate them, often requiring the non-expression of many other behaviors including feeding and drinking.Homedes Ranquini, J. y Haro-García, F. Zoogen� ...

and protection of eggs do occur in some species. The female prairie skink uses respiratory water loss to maintain the humidity of the eggs which facilitates embryonic development. In lace monitors, the young hatch close to 300 days, and the female returns to help them escape the termite mound where the eggs were laid.Pianka and Vitt, pp. 115–116.

Around 20 percent of lizard species reproduce via viviparity

In animals, viviparity is development of the embryo inside the body of the mother, with the maternal circulation providing for the metabolic needs of the embryo's development, until the mother gives birth to a fully or partially developed juv ...

(live birth). This is particularly common in Anguimorphs. Viviparous species give birth to relatively developed young which look like miniature adults. Embryos are nourished via a placenta-like structure. A minority of lizards have parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek + ) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which the embryo develops directly from an egg without need for fertilization. In animals, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an unfertiliz ...

(reproduction from unfertilised eggs). These species consist of all females who reproduce asexually with no need for males. This is known to occur in various species of whiptail lizards.Pianka and Vitt, pp. 119. Parthenogenesis was also recorded in species that normally reproduce sexually. A captive female Komodo dragon produced a clutch of eggs, despite being separated from males for over two years.

Sex determination in lizards can be temperature-dependent. The temperature of the eggs' micro-environment can determine the sex of the hatched young: low temperature incubation produces more females while higher temperatures produce more males. However, some lizards have sex chromosomes and both male heterogamety (XY and XXY) and female heterogamety (ZW) occur.

Aging

A significant component of aging in the painted dragon lizard '' Ctenophorus pictus'' is fading breeding colors.Olsson M, Tobler M, Healey M, Perrin C, Wilson M. A significant component of ageing (DNA damage) is reflected in fading breeding colors: an experimental test using innate antioxidant mimetics in painted dragon lizards. Evolution. 2012 Aug;66(8):2475-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01617.x. Epub 2012 Apr 9. PMID 22834746 By manipulatingsuperoxide

In chemistry, a superoxide is a compound that contains the superoxide ion, which has the chemical formula . The systematic name of the anion is dioxide(1−). The reactive oxygen ion superoxide is particularly important as the product of t ...

levels (using a superoxide dismutase mimetic) it was shown that this fading coloration is likely due to gradual loss with lizard age of an innate capacity for antioxidation due to increasing DNA damage.

Behaviour

Diurnality

Diurnality is a form of plant and ethology, animal behavior characterized by activity during daytime, with a period of sleeping or other inactivity at night. The common adjective used for daytime activity is "diurnal". The timing of activity by ...

and thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

The majority of lizard species are active during the day, though some are active at night, notably geckos. As ectotherms, lizards have a limited ability to regulate their body temperature, and must seek out and bask in sunlight to gain enough heat to become fully active. Thermoregulation behavior can be beneficial in the short term for lizards as it allows the ability to buffer environmental variation and endure climate warming.

In high altitudes, the ''Podarcis hispaniscus'' responds to higher temperature with a darker dorsal coloration to prevent UV-radiation and background matching. Their thermoregulatory mechanisms also allow the lizard to maintain their ideal body temperature for optimal mobility.

Territoriality

Most social interactions among lizards are between breeding individuals.Pianka and Vitt, pp. 86. Territoriality is common and is correlated with species that use sit-and-wait hunting strategies. Males establish and maintain territories that contain resources that attract females and which they defend from other males. Important resources include basking, feeding, and nesting sites as well as refuges from predators. The habitat of a species affects the structure of territories, for example, rock lizards have territories atop rocky outcrops.Pianka and Vitt, pp. 94–106. Some species may aggregate in groups, enhancing vigilance and lessening the risk of predation for individuals, particularly for juveniles. Agonistic behaviour typically occurs between sexually mature males over territory or mates and may involve displays, posturing, chasing, grappling and biting.Communication

Lizards signal both to attract mates and to intimidate rivals. Visual displays include body postures and inflation, push-ups, bright colours, mouth gapings and tail waggings. Male

Lizards signal both to attract mates and to intimidate rivals. Visual displays include body postures and inflation, push-ups, bright colours, mouth gapings and tail waggings. Male anole

Dactyloidae are a family of lizards commonly known as anoles (singular anole ) and native to warmer parts of the Americas, ranging from southeastern United States to Paraguay. Instead of treating it as a family, some authorities prefer to treat ...

s and iguanas have dewlaps or skin flaps which come in various sizes, colours and patterns and the expansion of the dewlap as well as head-bobs and body movements add to the visual signals. Some species have deep blue dewlaps and communicate with ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

signals. Blue-tongued skinks will flash their tongues as a threat display. Chameleons are known to change their complex colour patterns when communicating, particularly during agonistic encounters. They tend to show brighter colours when displaying aggression and darker colours when they submit or "give up".

Several gecko species are brightly coloured; some species tilt their bodies to display their coloration. In certain species, brightly coloured males turn dull when not in the presence of rivals or females. While it is usually males that display, in some species females also use such communication. In the bronze anole, head-bobs are a common form of communication among females, the speed and frequency varying with age and territorial status. Chemical cues or pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s are also important in communication. Males typically direct signals at rivals, while females direct them at potential mates. Lizards may be able to recognise individuals of the same species by their scent.Pianka and Vitt, pp. 87–94.

Acoustic communication is less common in lizards. Hissing, a typical reptilian sound, is mostly produced by larger species as part of a threat display, accompanying gaping jaws. Some groups, particularly geckos, snake-lizards, and some iguanids, can produce more complex sounds and vocal apparatuses have independently evolved in different groups. These sounds are used for courtship, territorial defense and in distress, and include clicks, squeaks, barks and growls. The mating call of the male tokay gecko is heard as "tokay-tokay!". Tactile communication involves individuals rubbing against each other, either in courtship or in aggression. Some chameleon species communicate with one another by vibrating the substrate that they are standing on, such as a tree branch or leaf.

Defence

Lizards are normally quick and agile to easily outrun attackers.Ecology

Distribution and habitat

Lizards are found worldwide, excluding the far north and Antarctica, and some islands. They can be found in elevations from sea level to . They prefer warmer, tropical climates but are adaptable and can live in all but the most extreme environments. Lizards also exploit a number of habitats; most primarily live on the ground, but others may live in rocks, on trees, underground and even in water. The marine iguana is adapted for life in the sea.Diet

The majority of lizard species are predatory and the most common prey items are small, terrestrial invertebrates, particularly

The majority of lizard species are predatory and the most common prey items are small, terrestrial invertebrates, particularly insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s. Many species are sit-and-wait predators though others may be more active foragers. Chameleons prey on numerous insect species, such as beetle

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

s, grasshopper

Grasshoppers are a group of insects belonging to the suborder Caelifera. They are amongst what are possibly the most ancient living groups of chewing herbivorous insects, dating back to the early Triassic around 250 million years ago.

Grassh ...

s and winged termites

Termites are a group of detritophagous eusocial cockroaches which consume a variety of decaying plant material, generally in the form of wood, leaf litter, and soil humus. They are distinguished by their moniliform antennae and the sof ...

as well as spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s. They rely on persistence and ambush to capture these prey. An individual perches on a branch and stays perfectly still, with only its eyes moving. When an insect lands, the chameleon focuses its eyes on the target and slowly moves toward it before projecting its long sticky tongue which, when hauled back, brings the attached prey with it. Geckos feed on cricket

Cricket is a Bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball game played between two Sports team, teams of eleven players on a cricket field, field, at the centre of which is a cricket pitch, pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two Bail (cr ...

s, beetles, termites and moth

Moths are a group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not Butterfly, butterflies. They were previously classified as suborder Heterocera, but the group is Paraphyly, paraphyletic with respect to butterflies (s ...

s.

Termites are an important part of the diets of some species of Autarchoglossa, since, as social insect

Eusociality (Ancient Greek, Greek 'good' and social) is the highest level of organization of sociality. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative Offspring, brood care (including care of offspring from other individuals), ove ...

s, they can be found in large numbers in one spot. Ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s may form a prominent part of the diet of some lizards, particularly among the lacertas. Horned lizards are also well known for specializing on ants. Due to their small size and indigestible chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, ants must be consumed in large amounts, and ant-eating lizards have larger stomachs than even herbivorous ones. Species of skink and alligator lizards eat snail

A snail is a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial molluscs, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class Gas ...

s and their power jaws and molar-like teeth are adapted for breaking the shells.

Larger species, such as monitor lizards, can feed on larger prey including fish, frogs, birds, mammals and other reptiles. Prey may be swallowed whole and torn into smaller pieces. Both bird and reptile eggs may also be consumed as well. Gila monsters and beaded lizards climb trees to reach both the eggs and young of birds. Despite being venomous, these species rely on their strong jaws to kill prey. Mammalian prey typically consists of

Larger species, such as monitor lizards, can feed on larger prey including fish, frogs, birds, mammals and other reptiles. Prey may be swallowed whole and torn into smaller pieces. Both bird and reptile eggs may also be consumed as well. Gila monsters and beaded lizards climb trees to reach both the eggs and young of birds. Despite being venomous, these species rely on their strong jaws to kill prey. Mammalian prey typically consists of rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s and leporids; the Komodo dragon can kill prey as large as water buffalo

The water buffalo (''Bubalus bubalis''), also called domestic water buffalo, Asian water buffalo and Asiatic water buffalo, is a large bovid originating in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Today, it is also kept in Italy, the Balkans ...

. Dragons are prolific scavengers, and a single decaying carcass can attract several from away. A dragon is capable of consuming a carcass in 17 minutes.Pianka and Vitt, pp. 41–51.

Around 2 percent of lizard species, including many iguanids, are herbivores. Adults of these species eat plant parts like flowers, leaves, stems and fruit, while juveniles eat more insects. Plant parts can be hard to digest, and, as they get closer to adulthood, juvenile iguanas eat faeces from adults to acquire the microflora necessary for their transition to a plant-based diet. Perhaps the most herbivorous species is the marine iguana which dives to forage for algae, kelp and other marine plants. Some non-herbivorous species supplement their insect diet with fruit, which is easily digested.

Antipredator adaptations

Lizards have a variety of antipredator adaptations, including running and climbing,

Lizards have a variety of antipredator adaptations, including running and climbing, venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

, camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the b ...

, tail autotomy, and reflex bleeding.

Camouflage

Lizards exploit a variety of different camouflage methods. Many lizards are disruptively patterned. In some species, such as Aegean wall lizards, individuals vary in colour, and select rocks which best match their own colour to minimise the risk of being detected by predators. The Moorish gecko is able to change colour for camouflage: when a light-coloured gecko is placed on a dark surface, it darkens within an hour to match the environment. The chameleons in general use their ability to change their coloration for signalling rather than camouflage, but some species such as Smith's dwarf chameleon do use active colour change for camouflage purposes. The flat-tail horned lizard's body is coloured like its desert background, and is flattened and fringed with white scales to minimise its shadow.Autotomy

Many lizards, includinggecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates. They range from .

Geckos are unique among lizards ...

s and skink

Skinks are a type of lizard belonging to the family (biology), family Scincidae, a family in the Taxonomic rank, infraorder Scincomorpha. With more than 1,500 described species across 100 different taxonomic genera, the family Scincidae is one o ...

s, are capable of shedding their tails ( autotomy). The detached tail, sometimes brilliantly coloured, continues to writhe after detaching, distracting the predator's attention from the fleeing prey. Lizards partially regenerate their tails over a period of weeks. Some 326 genes are involved in regenerating lizard tails. The fish-scale gecko '' Geckolepis megalepis '' sheds patches of skin and scales if grabbed.

Escape, playing dead, reflex bleeding

Many lizards attempt to escape from danger by running to a place of safety; for example, wall lizards can run up walls and hide in holes or cracks. Horned lizards adopt differing defences for specific predators. They may play dead to deceive a predator that has caught them; attempt to outrun the rattlesnake, which does not pursue prey; but stay still, relying on their cryptic coloration, for '' Masticophis'' whip snakes which can catch even swift prey. If caught, some species such as the greater short-horned lizard puff themselves up, making their bodies hard for a narrow-mouthed predator like a whip snake to swallow. Finally, horned lizards can squirt blood at cat and dog predators from a pouch beneath its eyes, to a distance of about ; the blood tastes foul to these attackers.Evolution

Fossil history

The closest living relatives of lizards are rhynchocephalians, a once diverse order of reptiles, of which is there is now only one living species, thetuatara

The tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') is a species of reptile endemic to New Zealand. Despite its close resemblance to lizards, it is actually the only extant member of a distinct lineage, the previously highly diverse order Rhynchocephal ...

of New Zealand. Some reptiles from the Early and Middle Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

, like '' Sophineta'' and '' Megachirella'', are suggested to be stem-group squamates, more closely related to modern lizards than rhynchocephalians, however, their position is disputed, with some studies recovering them as less closely related to squamates than rhynchocephalians are. The oldest undisputed lizards date to the Middle Jurassic, from remains found In Europe, Asia and North Africa. Lizard morphological and ecological diversity substantially increased over the course of the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

. In the Palaeogene, lizard body sizes in North America peaked during the middle of the period.

Mosasaurs likely evolved from an extinct group of aquatic lizards known as aigialosaurs in the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous (geochronology, geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphy, chronostratigraphic name) is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 143.1 ...

. Dolichosauridae

Dolichosauridae (from Latin, ''dolichos'' = "long" and Ancient Greek, Greek ''sauros''= lizard) is a family of Cretaceous Aquatic animal, aquatic lizards. They are widely considered to be the earliest and most primitive members of Mosasauria, tho ...

is a family of Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

aquatic varanoid lizards closely related to the mosasaurs.

Phylogeny

External

The position of the lizards and otherSquamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

among the reptiles was studied using fossil evidence by Rainer Schoch and Hans-Dieter Sues in 2015. Lizards form about 60% of the extant non-avian reptiles.

Internal

Both the snakes and theAmphisbaenia

Amphisbaenia (called amphisbaenians or worm lizards) is a group of typically legless lizards, comprising over 200 extant species. Amphisbaenians are characterized by their long bodies, the reduction or loss of the limbs, and rudimentary eyes. A ...

(worm lizards) are clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s deep within the Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

(the smallest clade that contains all the lizards), so "lizard" is paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

.

The cladogram is based on genomic analysis by Wiens and colleagues in 2012 and 2016. Excluded taxa are shown in upper case on the cladogram.

Taxonomy

In the 13th century, lizards were recognized in Europe as part of a broad category of ''reptiles'' that consisted of a miscellany of egg-laying creatures, including "snakes, various fantastic monsters, �� assorted amphibians, and worms", as recorded by Vincent of Beauvais in his ''Mirror of Nature''. The seventeenth century saw changes in this loose description. The name Sauria was coined by James Macartney (1802); it was the Latinisation of the French name ''Sauriens'', coined by Alexandre Brongniart (1800) for an order of reptiles in the classification proposed by the author, containing lizards andcrocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

ns, later discovered not to be each other's closest relatives. Later authors used the term "Sauria" in a more restricted sense, i.e. as a synonym of Lacertilia, a suborder of Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

that includes all lizards but excludes snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s. This classification is rarely used today because Sauria so-defined is a paraphyletic

Paraphyly is a taxonomic term describing a grouping that consists of the grouping's last common ancestor and some but not all of its descendant lineages. The grouping is said to be paraphyletic ''with respect to'' the excluded subgroups. In co ...

group. It was defined as a clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

by Jacques Gauthier, Arnold G. Kluge and Timothy Rowe (1988) as the group containing the most recent common ancestor of archosaurs and lepidosaurs (the groups containing crocodiles and lizards, as per Mcartney's original definition) and all its descendants. A different definition was formulated by Michael deBraga and Olivier Rieppel (1997), who defined Sauria as the clade containing the most recent common ancestor of Choristodera, Archosauromorpha, Lepidosauromorpha and all their descendants. However, these uses have not gained wide acceptance among specialists.

Suborder Lacertilia (Sauria) – (lizards)

* Family † Bavarisauridae

* Family † Eichstaettisauridae

* Infraorder Iguanomorpha

** Family † Arretosauridae

** Family † Euposauridae

** Family Corytophanidae (casquehead lizards)

** Family Iguanidae

The Iguanidae is a family of lizards composed of the iguanas, chuckwallas, and their prehistoric relatives, including the widespread green iguana.

Taxonomy

Iguanidae is thought to be the sister group to the Crotaphytidae, collared lizards (fam ...

( iguanas and spinytail iguanas)

** Family Phrynosomatidae ( earless, spiny, tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, e.g., including only woody plants with secondary growth, only ...

, side-blotched and horned lizards)

** Family Polychrotidae (anole

Dactyloidae are a family of lizards commonly known as anoles (singular anole ) and native to warmer parts of the Americas, ranging from southeastern United States to Paraguay. Instead of treating it as a family, some authorities prefer to treat ...

s)

*** Family Leiosauridae (see Polychrotinae)

** Family Tropiduridae (neotropical ground lizards)

*** Family Liolaemidae (see Tropidurinae)

*** Family Leiocephalidae (see Tropidurinae)

** Family Crotaphytidae ( collared and leopard lizards)

** Family Opluridae (Madagascar iguanids)

** Family Hoplocercidae (wood lizards, clubtails)

** Family † Priscagamidae

** Family † Isodontosauridae

** Family Agamidae ( agamas, frilled lizards)

** Family Chamaeleonidae ( chameleons)

* Infraorder Gekkota

** Family Gekkonidae (gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates. They range from .

Geckos are unique among lizards ...

s)

** Family Pygopodidae

Pygopodidae, commonly known as snake-lizards, or flap-footed lizards, are a Family (biology), family of Legless lizard, legless lizards with reduced or absent limbs, and are a type of gecko. The 47 species are placed in two subfamilies and eight ...

(legless geckos)

** Family Dibamidae

Dibamidae or blind skinks is a family of lizards characterized by their elongated cylindrical body and an apparent lack of limbs. Female dibamids are entirely limbless and the males retain small flap-like hind limbs, which they use to grip their ...

(blind lizards)

* Infraorder Scincomorpha

Scincomorpha is an infraorder and clade of lizards including skinks (Scincidae) and their close relatives. These include the living families Cordylidae (girdled lizards), Gerrhosauridae (plated lizards), and Xantusiidae (night lizards), as well a ...

** Family † Paramacellodidae

** Family † Slavoiidae

** Family Scincidae (skinks)

** Family Cordylidae (spinytail lizards)

** Family Gerrhosauridae (plated lizards)

** Family Xantusiidae (night lizards)

** Family Lacertidae (wall lizards or true lizards)

** Family † Mongolochamopidae

** Family † Adamisauridae

** Family Teiidae

Teiidae is a family of lacertoidean lizards native to the Americas. Members of this family are generally known as whiptails or racerunners; however, tegus also belong to this family. Teiidae is sister to the Gymnophthalmidae, Gymnopthalmidae, and ...

( tegus and whiptails)

** Family Gymnophthalmidae (spectacled lizards)

* Infraorder Diploglossa

** Family Anguidae (slowworms, glass lizards)

** Family Anniellidae (American legless lizards)

** Family Xenosauridae

Xenosauridae is a family of anguimorph lizards whose only living representative is the genus '' Xenosaurus'', which is native to Central America. Xenosauridae also includes the extinct genera '' Exostinus'' and '' Restes''. Also known as knob-sca ...

(knob-scaled lizards)

* Infraorder Platynota ( Varanoidea)

** Family Varanidae (monitor lizards)

** Family Lanthanotidae (earless monitor lizards)

** Family Helodermatidae ( Gila monsters and beaded lizards)

** Family †Mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Ancient Greek, Greek ' meaning 'lizard') are an extinct group of large aquatic reptiles within the family Mosasauridae that lived during the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains wer ...

idae (marine lizards)

Convergence

Lizards have frequently evolved convergently, with multiple groups independently developing similar morphology andecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

s. ''Anolis'' ecomorphs have become a model system in evolutionary biology for studying convergence. Limbs have been lost or reduced independently over two dozen times across lizard evolution, including in the Anniellidae, Anguidae, Cordylidae, Dibamidae

Dibamidae or blind skinks is a family of lizards characterized by their elongated cylindrical body and an apparent lack of limbs. Female dibamids are entirely limbless and the males retain small flap-like hind limbs, which they use to grip their ...

, Gymnophthalmidae, Pygopodidae

Pygopodidae, commonly known as snake-lizards, or flap-footed lizards, are a Family (biology), family of Legless lizard, legless lizards with reduced or absent limbs, and are a type of gecko. The 47 species are placed in two subfamilies and eight ...

, and Scincidae; snakes are just the most famous and species-rich group of Squamata to have followed this path.

Relationship with humans

Interactions and uses by humans

Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the largest lizard species, the Komodo dragon, which reaches in length and weighs up to , has been known to stalk, attack, and, on occasion, kill humans. An eight-year-old Indonesian boy died from blood loss after an attack in 2007. Numerous species of lizard are kept as pets, including bearded dragons, iguanas,

Numerous species of lizard are kept as pets, including bearded dragons, iguanas, anole

Dactyloidae are a family of lizards commonly known as anoles (singular anole ) and native to warmer parts of the Americas, ranging from southeastern United States to Paraguay. Instead of treating it as a family, some authorities prefer to treat ...

s, and gecko

Geckos are small, mostly carnivorous lizards that have a wide distribution, found on every continent except Antarctica. Belonging to the infraorder Gekkota, geckos are found in warm climates. They range from .

Geckos are unique among lizards ...

s (such as the popular leopard gecko). Monitor lizards such as the savannah monitor and tegus such as the Argentine tegu and red tegu are also kept.

Green iguanas are eaten in Central America, where they are sometimes referred to as "chicken of the tree" after their habit of resting in trees and their supposedly chicken-like taste, while spiny-tailed lizards are eaten in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

. In North Africa, ''Uromastyx'' species are considered ''dhaab'' or 'fish of the desert' and eaten by nomadic tribes. Lizards such as the Gila monster produce toxins with medical applications. Gila toxin reduces plasma glucose; the substance is now synthesized for use in the anti-

Lizards such as the Gila monster produce toxins with medical applications. Gila toxin reduces plasma glucose; the substance is now synthesized for use in the anti-diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

drug exenatide (Byetta). Another toxin from Gila monster saliva has been studied for use as an anti- Alzheimer's drug.

In culture

Lizards appear in myths and folktales around the world. In Australian Aboriginal mythology, Tarrotarro, the lizard god, split the human race into male and female, and gave people the ability to express themselves in art. A lizard king named Mo'o features in Hawaii and other cultures in Polynesia. In the Amazon, the lizard is the king of beasts, while among the Bantu of Africa, the god UNkulunkulu sent a chameleon to tell humans they would live forever, but the chameleon was held up, and another lizard brought a different message, that the time of humanity was limited. A popular legend inMaharashtra

Maharashtra () is a state in the western peninsular region of India occupying a substantial portion of the Deccan Plateau. It is bordered by the Arabian Sea to the west, the Indian states of Karnataka and Goa to the south, Telangana to th ...

tells the tale of how a common Indian monitor, with ropes attached, was used to scale the walls of the fort in the Battle of Sinhagad.

Lizards in many cultures share the symbolism of snakes, especially as an emblem of resurrection. This may have derived from their regular molting. The motif of lizards on Christian candle holders probably alludes to the same symbolism. According to Jack Tresidder, in Egypt and the Classical world, they were beneficial emblems, linked with wisdom. In African, Aboriginal and Melanesian folklore they are linked to cultural heroes or ancestral figures.

Notes

References

General sources

*Further reading

* * * * * * * * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Lizard Paraphyletic groups Extant Hettangian first appearances