Leopold of Saxe-Coburg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

* nl, Leopold Joris Christiaan Frederik

* en, Leopold George Christian Frederick

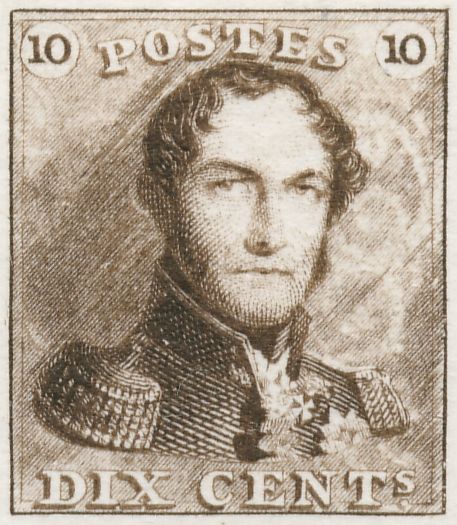

, image = NICAISE Leopold ANV.jpg

, caption = Portrait by  After the

After the

Leopold was born in Coburg in the tiny German duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld in modern-day

Leopold was born in Coburg in the tiny German duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld in modern-day

Leopold received British citizenship in March 1816. On 2 May 1816, Leopold married

Leopold received British citizenship in March 1816. On 2 May 1816, Leopold married

At the end of August 1830, rebels in the Southern provinces (modern-day

At the end of August 1830, rebels in the Southern provinces (modern-day

Leopold I's reign was also marked by an economic crisis which lasted until the late 1850s. In the aftermath of the revolution, the Dutch had closed the

Leopold I's reign was also marked by an economic crisis which lasted until the late 1850s. In the aftermath of the revolution, the Dutch had closed the

Nicaise de Keyser

Nicaise de Keyser (alternative first names: Nicaas, Nikaas of Nicasius; 26 August 1813, Zandvliet – 17 July 1887, Antwerp) was a Belgian painter of mainly history paintings and portraits who was one of the key figures in the Belgian Romantic- ...

, 1856

, reign = 21 July 1831 –

, predecessor = Erasme Louis Surlet de Chokier

Érasme-Louis, Baron Surlet de Chokier (27 November 1769 – 7 August 1839), born in Liège, was a Belgian politician and, before the accession of Leopold I to the Belgian throne, was the first Regent of Belgium.

During the Liège Revolution ...

(as Regent of Belgium)

, successor = Leopold II

, reg-type =

, regent =

, spouse =

, issue =

, house =

, father = Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

, mother = Countess Augusta Reuss of Ebersdorf

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Ehrenburg Palace, Coburg, Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a Polity, political entity in Western Europe, Western, Central Europe, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its Dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, dissolution i ...

(modern-day Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

)

, death_date =

, death_place = Castle of Laeken

The Palace of Laeken or Castle of Laeken (french: Château de Laeken, nl, Kasteel van Laken, german: Schloss zu Laeken) is the official residence of the King of the Belgians and the Belgian Royal Family. It lies in the Brussels-Capital Regio ...

, Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, burial_place = Church of Our Lady of Laeken

, religion = Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched th ...

, module =

, signature = Signatur Leopold I. (Belgien).PNG

Leopold I (french: Léopold; 16 December 1790 – 10 December 1865) was the first king of the Belgians

Belgium is a constitutional, hereditary, and popular monarchy. The monarch is titled king or queen of the Belgians ( nl, Koning(in) der Belgen, french: Roi / Reine des Belges}, german: König(in) der Belgier) and serves as the country's h ...

, reigning from 21 July 1831 until his death in 1865.

The youngest son of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, Leopold took a commission in the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

and fought against Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

after French troops overran Saxe-Coburg during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. After Napoleon's defeat, Leopold moved to the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

where he married Princess Charlotte of Wales Princess Charlotte of Wales may refer to:

* Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796–1817), the only child of George, Prince of Wales, later King George IV of the United Kingdom

** Princess Charlotte of Wales (1812 EIC ship), a ship named after the pri ...

, who was second in line to the British throne and the only legitimate child of the Prince Regent (the future King George IV

George IV (George Augustus Frederick; 12 August 1762 – 26 June 1830) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from the death of his father, King George III, on 29 January 1820, until his own death ten y ...

). Charlotte died after only a year of marriage, but Leopold continued to enjoy considerable status in Britain.

After the

After the Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. The Greeks were later assisted by ...

(1821–1830), Leopold was offered the throne of Greece under the 1830 London Protocol that created an independent Greek state, but turned it down, believing it to be too precarious. Instead, he accepted the throne of Belgium in 1831 following the country's independence in 1830. The Belgian government offered the position to Leopold because of his diplomatic connections with royal houses across Europe, and because as the British-backed candidate, he was not affiliated with other powers, such as France, which were believed to have territorial ambitions in Belgium which might threaten the European balance of power created by the 1815 Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna (, ) of 1814–1815 was a series of international diplomatic meetings to discuss and agree upon a possible new layout of the European political and constitutional order after the downfall of the French Emperor Napoleon B ...

.

Leopold took his oath as King of the Belgians on 21 July 1831, an event commemorated annually as Belgian National Day

Belgian National Day ( nl, Nationale feestdag van België; french: Fête nationale belge; german: Belgischer Nationalfeiertag) is the national holiday of Belgium commemorated annually on 21 July. It is one of the country's ten public holidays a ...

. His reign was marked by attempts by the Dutch to recapture Belgium and, later, by internal political division between liberals and Catholics. As a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, Leopold was considered liberal and encouraged economic modernisation, playing an important role in encouraging the creation of Belgium's first railway

Belgium was heavily involved in the early development of railway transport. Belgium was the second country in Europe, after Great Britain, to open a railway and produce locomotives. The first line, between the cities of Brussels and Mechelen ope ...

in 1835 and subsequent industrialisation

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

. As a result of the ambiguities in the Belgian Constitution

The Constitution of Belgium ( nl, Belgische Grondwet, french: Constitution belge, german: Verfassung Belgiens) dates back to 1831. Since then Belgium has been a parliamentary monarchy that applies the principles of ministerial responsibility f ...

, Leopold was able to slightly expand the monarch's powers during his reign. He also played an important role in stopping the spread of the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Europea ...

into Belgium. He died in 1865 and was succeeded by his son, Leopold II.

Early life

Leopold was born in Coburg in the tiny German duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld in modern-day

Leopold was born in Coburg in the tiny German duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld in modern-day Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

on 16 December 1790. He was the youngest son of Francis, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, and Countess Augusta of Reuss-Ebersdorf

Countess Augusta Caroline Sophie Reuss-Ebersdorf () (19 January 1757 – 16 November 1831), was by marriage the Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. She was the maternal grandmother of Queen Victoria and the paternal grandmother of Albert, Princ ...

. In 1826, Saxe-Coburg acquired the city of Gotha from the neighboring Duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg

Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg () was a duchy ruled by the Ernestine branch of the House of Wettin in today's Thuringia, Germany. The extinction of the line in 1825 led to a major re-organisation of the Thuringian states.

History

In 1640 the sons of the l ...

and gave up Saalfeld to Saxe-Meiningen, becoming Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (german: Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha), or Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (german: Sachsen-Coburg-Gotha, links=no ), was an Ernestine, Thuringian duchy ruled by a branch of the House of Wettin, consisting of territories in the present-d ...

.

Military career

In 1797, at just six years old, Leopold was given an honorary commission of the rank ofcolonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

in the ''Izmaylovsky'' Regiment, part of the Imperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the Emperor or Empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial forces, in ...

, in the Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

. Six years later, he received a promotion to the rank of Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

.

When French troops occupied the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, Leopold went to Paris where he became part of the Imperial Court of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

. Napoleon offered him the position of adjutant, but Leopold refused. Instead, he went to Russia to take up a military career in the Imperial Russian cavalry, which was at war with France at the time. He campaigned against Napoleon and distinguished himself at the Battle of Kulm at the head of his '' cuirassier'' division. By 1815, the time of the final defeat of Napoleon, he had reached the rank of lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

at only 25 years of age.

Marriage to Charlotte

Leopold received British citizenship in March 1816. On 2 May 1816, Leopold married

Leopold received British citizenship in March 1816. On 2 May 1816, Leopold married Princess Charlotte of Wales Princess Charlotte of Wales may refer to:

* Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796–1817), the only child of George, Prince of Wales, later King George IV of the United Kingdom

** Princess Charlotte of Wales (1812 EIC ship), a ship named after the pri ...

at Carlton House in London. Charlotte was the only legitimate child of the Regent George (later George IV) and therefore second in line to the British throne. The Prince Regent had hoped Charlotte would marry William, Prince of Orange

William, Prince of Orange (Willem Nicolaas Alexander Frederik Karel Hendrik; 4 September 1840 – 11 June 1879), was heir apparent to the Dutch throne as the eldest son of King William III from 17 March 1849 until his death.

Early life

Prince Wi ...

, but she favoured Leopold. Although the Regent was displeased, he found Leopold to be charming and possessing every quality to make his daughter happy, and so approved their marriage. The same year Leopold received an honorary commission to the rank of Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

and Knight of the Order of the Garter

The Most Noble Order of the Garter is an order of chivalry founded by Edward III of England in 1348. It is the most senior order of knighthood in the British honours system, outranked in precedence only by the Victoria Cross and the George C ...

. The Regent also considered making Leopold a royal duke

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they are ranked ...

, the Duke of Kendal

The titles of Earl of Kendal and Duke of Kendal have been created several times, usually for people with some connection to the royal family.

*The first creation was for John, 4th son of King Henry IV, who was created Earl of Kendal, Earl of Ri ...

, though the plan was abandoned due to government fears that it would draw Leopold into party politics and would be viewed as a demotion for Charlotte. The couple lived initially at Camelford House on Park Lane

Park Lane is a dual carriageway road in the City of Westminster in Central London. It is part of the London Inner Ring Road and runs from Hyde Park Corner in the south to Marble Arch in the north. It separates Hyde Park to the west from May ...

, and then at Marlborough House on Pall Mall.

On 5 November 1817, after having suffered a miscarriage, Princess Charlotte gave birth to a stillborn son. She herself died the next day following complications. Leopold was said to have been heartbroken by her death.

Had Charlotte survived, she would have become queen of the United Kingdom on the death of her father and Leopold presumably would have assumed the role of prince consort, later taken by his nephew Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Franz August Karl Albert Emanuel; 26 August 1819 – 14 December 1861) was the consort of Queen Victoria from their marriage on 10 February 1840 until his death in 1861.

Albert was born in the Saxon duch ...

. Despite Charlotte's death, the Prince Regent granted Prince Leopold the British style of '' Royal Highness'' by Order in Council on 6 April 1818.

From 1828 to 1829, Leopold had an affair with the actress Caroline Bauer

Caroline Bauer (29 March 1807 – 18 October 1877) was a German actress of the Biedermeier era who used the name Lina Bauer.

Biography

Caroline Philippina Augusta Bauer (german: Karoline Philippine Auguste Bauer) was born in Heidelberg, Ger ...

, who bore a striking resemblance to Charlotte. Caroline was a cousin of his advisor Baron Christian Friedrich von Stockmar. She came to England with her mother and took up residence at Longwood House, a few miles from Claremont House

Claremont, also known historically as 'Clermont', is an 18th-century Palladian mansion less than a mile south of the centre of Esher in Surrey, England. The buildings are now occupied by Claremont Fan Court School, and its landscaped gardens are ...

. But, by mid-1829, the liaison was over, and the actress and her mother returned to Berlin. Many years later, in memoirs published after her death, she declared that she and Leopold had engaged in a morganatic marriage and that he had bestowed upon her the title of Countess Montgomery. He would have broken this marriage when the possibility arose that he could become King of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach between 1832 and 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924, temporarily abolished during the Second Hellenic Republic, and from 1935 to 1973, when it was once more abolishe ...

. The son of Baron Stockmar denied that these events ever happened, and indeed no records have been found of a civil or religious marriage with the actress.

Refusal of the Greek throne

Following a Greek rebellion against theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, Leopold was offered the throne of an independent Greece as part of the London Protocol of February 1830. Though initially showing interest in the position, Leopold eventually turned down the offer on 17 May 1830. The role would subsequently be accepted by Otto of Wittelsbach in May 1832 who ruled until he was finally deposed in October 1862.

Acceptance of the Belgian throne

Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

) of the United Netherlands rose up against Dutch rule. The rising, which began in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

, pushed the Dutch army back, and the rebels defended themselves against a Dutch attack. International powers meeting in London agreed to support the independence of Belgium, even though the Dutch refused to recognize the new state.

In November 1830, a National Congress ''National Congress'' is a term used in the names of various political parties and legislatures .

Political parties

*Ethiopia: Oromo National Congress

*Guyana: People's National Congress (Guyana)

*India: Indian National Congress

*Iraq: Iraqi Nati ...

was established in Belgium to create a constitution for the new state. Fears of "mob rule

Mob rule or ochlocracy ( el, ὀχλοκρατία, translit=okhlokratía; la, ochlocratia) is the rule of government by a mob or mass of people and the intimidation of legitimate authorities. Insofar as it represents a pejorative for majori ...

" associated with republicanism after the French Revolution of 1789, as well as the example of the recent, liberal July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

in France, led the Congress to decide that Belgium would be a popular, constitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

.

Search for a monarch

The choice of candidates for the position was one of the most controversial issues faced by the revolutionaries. The Congress refused to consider any candidate from the Dutch rulinghouse of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau (Dutch: ''Huis van Oranje-Nassau'', ) is the current reigning house of the Netherlands. A branch of the European House of Nassau, the house has played a central role in the politics and government of the Netherlands ...

. Some Orangists had hoped to offer the position to William I

William I; ang, WillelmI (Bates ''William the Conqueror'' p. 33– 9 September 1087), usually known as William the Conqueror and sometimes William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England, reigning from 1066 until his death in 1087 ...

or his son, William, Prince of Orange

William, Prince of Orange (Willem Nicolaas Alexander Frederik Karel Hendrik; 4 September 1840 – 11 June 1879), was heir apparent to the Dutch throne as the eldest son of King William III from 17 March 1849 until his death.

Early life

Prince Wi ...

, which would bring Belgium into personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interlink ...

with the Netherlands like Luxembourg. The Great Power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

s also worried that a candidate from another state could risk destabilizing the international balance of power and lobbied for a neutral candidate.

Eventually the Congress was able to draw up a shortlist. The three viable possibilities were felt to be Eugène de Beauharnais

Eugène Rose de Beauharnais, Duke of Leuchtenberg (; 3 September 1781 – 21 February 1824) was a French nobleman, statesman, and military commander who served during the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars.

Through the second marr ...

, a French nobleman and stepson of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

; Auguste of Leuchtenberg, son of Eugène; and Louis, Duke of Nemours

Prince Louis of Orléans, Duke of Nemours (Louis Charles Philippe Raphaël d'Orléans; 25 October 1814 – 26 June 1896) was the second son of King Louis-Philippe I of France, and his wife Maria Amalia of Naples and Sicily.

Life

Childhoo ...

, who was the son of the French King Louis-Philippe. All the candidates were French and the choice between them was principally between choosing the Bonapartism

Bonapartism (french: Bonapartisme) is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was used to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In thi ...

of Beauharnais or Leuchtenberg and supporting the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 F ...

of Louis-Philippe. Louis-Philippe realized that the choice of either of the Bonapartists could be first stage of a coup against him, but that his son would also be unacceptable to other European powers suspicious of French intentions. Nemours refused the offer. With no definitive choice in sight, Catholics and Liberals united to elect Erasme Louis Surlet de Chokier

Érasme-Louis, Baron Surlet de Chokier (27 November 1769 – 7 August 1839), born in Liège, was a Belgian politician and, before the accession of Leopold I to the Belgian throne, was the first Regent of Belgium.

During the Liège Revolution ...

, a minor Belgian nobleman, as regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

to buy more time for a definitive decision in February 1831.

Leopold of Saxe-Coburg had been proposed at an early stage, but had been dropped because of French opposition. The problems caused by the French candidates and the increased international pressure for a solution led to his reconsideration. On 22 April, he was finally approached by a Belgian delegation at Marlborough House to officially offer him the throne. Leopold, however, was reluctant to accept.

Accession

On 17 July 1831, Leopold travelled from Calais to Belgium, entering the country atDe Panne

De Panne (; french: La Panne ) is a town and a municipality located on the North Sea coast of the Belgian province of West Flanders. There it borders France, making it the westernmost town in Belgium. It is one of the most popular resort town dest ...

. Travelling to Brussels, he was greeted with patriotic enthusiasm along his route. The accession ceremony took place on 21 July on the Place Royale/Koningsplein in Brussels. A stand had been erected on the steps of the Church of St. James on Coudenberg, surrounded by the names of revolutionaries fallen during the fighting in 1830. After a ceremony of resignation by the regent, Leopold, dressed in the uniform of a Belgian lieutenant-general, swore loyalty to the constitution and became king.

The enthronement is generally used to mark the end of the revolution and the start of the Kingdom of Belgium and is celebrated each year as the Belgian national holiday.

Reign

Consolidation of independence

Less than two weeks after Leopold's accession, on 2 August, the Netherlands invaded Belgium, starting the Ten Days' Campaign. The small Belgian army was overwhelmed by the Dutch assault and was pushed back. Faced with a military crisis, Leopold appealed to the French for support. The French promised support, and the arrival of their ' in Belgium forced the Dutch to accept a diplomatic mediation and retreat back to the pre-war border. Skirmishes continued for eight years, but in April 1839, the two countries signed the Treaty of London, whereby the Dutch recognised Belgium's independence. Leopold was generally unsatisfied with the amount of power allocated to the monarch in the Constitution, and sought to extend it wherever the Constitution was ambiguous or unclear while generally avoiding involvement in routine politics.Subsequent reign

Leopold I's reign was also marked by an economic crisis which lasted until the late 1850s. In the aftermath of the revolution, the Dutch had closed the

Leopold I's reign was also marked by an economic crisis which lasted until the late 1850s. In the aftermath of the revolution, the Dutch had closed the Scheldt

The Scheldt (french: Escaut ; nl, Schelde ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of Netherlands, the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corr ...

to Belgian shipping, meaning that the port of Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

was effectively useless. The Netherlands and the Dutch colonies in particular, which had been profitable markets for Belgian manufacturers before 1830, were totally closed to Belgian goods. The period between 1845 and 1849 was particularly hard in Flanders, where harvests failed and a third of the population became dependent on poor relief, and have been described as the "worst years of Flemish history". The economic situation in Flanders also increased the internal migration to Brussels and the industrial areas of Wallonia

Wallonia (; french: Wallonie ), or ; nl, Wallonië ; wa, Waloneye or officially the Walloon Region (french: link=no, Région wallonne),; nl, link=no, Waals gewest; wa, link=no, Redjon walone is one of the three regions of Belgium—alo ...

, which continued throughout the period.

Politics in Belgium under Leopold I were polarized between liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

political factions, though before 1847 they collaborated in " Unionist" governments. The liberals were opposed to the Church's influence in politics and society, while supporting free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

, personal liberties and secularization

In sociology, secularization (or secularisation) is the transformation of a society from close identification with religious values and institutions toward non-religious values and secular institutions. The ''secularization thesis'' expresses the ...

. The Catholics wanted religious teachings to be a fundamental basis for the state and society and opposed all attempts by the liberals to attack the Church's official privileges. Initially, these factions existed only as informal groups with which prominent politicians were generally identified. The liberals held power through much of Leopold I's reign. An official Liberal Party was formed in 1846, although a formal Catholic Party was only established in 1869. Leopold, who was himself a Protestant, tended to favor liberals and shared their desire for reform, even though he was not partisan. On his own initiative, in 1842, Leopold proposed a law which would have stopped women and children from working in some industries, but the bill was defeated. Leopold was an early supporter of railway

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a pre ...

s, and Belgium's first stretch of railway, between northern Brussels and Mechelen

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

, was completed in 1835. When completed, it was one of the first passenger railways in