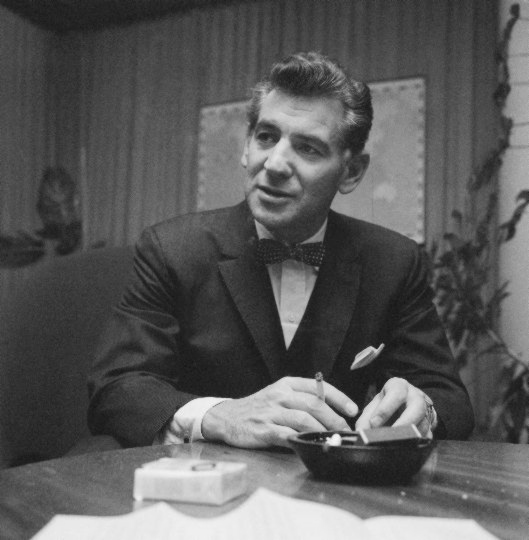

Leonard Bernstein ( ; August 25, 1918 – October 14, 1990) was an American conductor, composer, pianist, music educator, author, and humanitarian. Considered to be one of the most important conductors of his time, he was the first American conductor to receive international acclaim. According to music critic

Donal Henahan

Donal Henahan (February 28, 1921 – August 19, 2012) was an American music critic and journalist who had lengthy associations with the ''Chicago Daily News'' and ''The New York Times''. With the ''Times'' he won the annual Pulitzer Prize for ...

, he was "one of the most prodigiously talented and successful musicians in American history".

Bernstein was the recipient of many honors, including seven

Emmy Awards

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

, two

Tony Awards

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual cer ...

, sixteen

Grammy Awards

The Grammy Awards (stylized as GRAMMY), or simply known as the Grammys, are awards presented by the Recording Academy of the United States to recognize "outstanding" achievements in the music industry. They are regarded by many as the most pres ...

including the Lifetime Achievement Award, and the

Kennedy Center Honor

The Kennedy Center Honors are annual honors given to those in the performing arts for their lifetime of contributions to American culture. They have been presented annually since 1978, culminating each December in a gala celebrating five hono ...

.

As a composer he wrote in many genres, including symphonic and orchestral music, ballet, film and theatre music, choral works, opera, chamber music and works for the piano. His best-known work is the

Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

musical ''

West Side Story

''West Side Story'' is a musical conceived by Jerome Robbins with music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and a book by Arthur Laurents.

Inspired by William Shakespeare's play ''Romeo and Juliet'', the story is set in the mid-1 ...

'', which continues to be regularly performed worldwide, and has been adapted into two (

1961

Events January

* January 3

** United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower announces that the United States has severed diplomatic and consular relations with Cuba ( Cuba–United States relations are restored in 2015).

** Aero Flight 311 ...

and

2021

File:2021 collage V2.png, From top left, clockwise: the James Webb Space Telescope was launched in 2021; Protesters in Yangon, Myanmar following the 2021 Myanmar coup d'état, coup d'état; A civil demonstration against the October–November 2021 ...

) feature films.

His works include three symphonies, ''

Chichester Psalms

''Chichester Psalms'' is an extended choral composition in three movements by Leonard Bernstein for boy treble or countertenor, choir and orchestra. The text was arranged by the composer from the Book of Psalms in the original Hebrew. Part 1 us ...

'', ''

Serenade after Plato's "Symposium"

The ''Serenade, after Plato's Symposium'', is a composition by Leonard Bernstein for solo violin, strings and percussion. He completed the serenade in five movements on August 7, 1954. For the serenade, the composer drew inspiration from Plato's ...

'', the original score for the film ''

On the Waterfront

''On the Waterfront'' is a 1954 American crime drama film, directed by Elia Kazan and written by Budd Schulberg. It stars Marlon Brando and features Karl Malden, Lee J. Cobb, Rod Steiger, Pat Henning, and Eva Marie Saint in her film debut. ...

'', and theater works including ''

On the Town'', ''

Wonderful Town

''Wonderful Town'' is a 1953 musical with book written by Joseph A. Fields and Jerome Chodorov, lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and music by Leonard Bernstein. The musical tells the story of two sisters who aspire to be a writer and act ...

'', ''

Candide

( , ) is a French satire written by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment, first published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, The ...

'', and his ''

MASS

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

''.

Bernstein was the first American-born conductor to lead a major American symphony orchestra. He was music director of the

New York Philharmonic

The New York Philharmonic, officially the Philharmonic-Symphony Society of New York, Inc., globally known as New York Philharmonic Orchestra (NYPO) or New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, is a symphony orchestra based in New York City. It is ...

and conducted the world's major orchestras, generating a significant legacy of audio and video recordings. He was also a critical figure in the modern revival of the music of

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

, in whose music he was most passionately interested. A skilled pianist, he often conducted piano concertos from the keyboard. He was the first conductor to share and explore music on television with a mass audience. Through dozens of national and international broadcasts, including the Emmy Award-winning ''

Young People's Concerts

The Young People's Concerts with the New York Philharmonic are the longest-running series of family concerts of classical music in the world.

Genesis

They began in 1924 under the direction of "Uncle" Ernest Schelling. Earlier Family Matinees had ...

'' with the New York Philharmonic, he made even the most rigorous elements of classical music an adventure in which everyone could join. Through his educational efforts, including several books and the creation of two major international music festivals, he influenced several generations of young musicians.

A lifelong humanitarian, Bernstein worked in support of

civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

; protested against the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

; advocated nuclear disarmament; raised money for HIV/AIDS research and awareness; and engaged in multiple international initiatives for human rights and world peace. Near the end of his life, he conducted an historic performance of Beethoven's

Symphony No. 9 in Berlin to celebrate the

fall of the Berlin Wall

The fall of the Berlin Wall (german: Mauerfall) on 9 November 1989, during the Peaceful Revolution, was a pivotal event in world history which marked the destruction of the Berlin Wall and the figurative Iron Curtain and one of the series of eve ...

. The concert was televised live, worldwide, on Christmas Day, 1989.

Early life and education

1918–1934: Early life and family

Born Louis Bernstein in

Lawrence, Massachusetts, he was the son of

Ukrainian-Jewish

The history of the Jews in Ukraine dates back over a thousand years; Jewish communities have existed in the territory of Ukraine from the time of the Kievan Rus' (late 9th to mid-13th century). Some of the most important Jewish religious and ...

parents, Jennie (née Resnick) and Samuel Joseph Bernstein, both of whom immigrated to the United States from

Rivne

Rivne (; uk, Рівне ),) also known as Rovno (Russian: Ровно; Polish: Równe; Yiddish: ראָוונע), is a city in western Ukraine. The city is the administrative center of Rivne Oblast (province), as well as the surrounding Rivne Raio ...

(now in Ukraine).

[; als]

here

at ginnydougary.co.uk. His grandmother insisted that his first name be

Louis Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ( ...

, but his parents always called him

Leonard

Leonard or ''Leo'' is a common English masculine given name and a surname.

The given name and surname originate from the Old High German ''Leonhard'' containing the prefix ''levon'' ("lion") from the Greek Λέων ("lion") through the Latin '' L ...

. He legally changed his name to Leonard when he was eighteen, shortly after his grandmother's death. To his friends and many others he was simply known as "Lenny".

His father was the owner of The Samuel Bernstein Hair and Beauty Supply Company. It held the New England franchise for the Frederick's Permanent Wave Machine, whose immense popularity helped Sam get his family through

The Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

.

In Leonard's early youth, his only exposure to music was the household radio and music on Friday nights at Congregation Mishkan Tefila in

Roxbury, Massachusetts. When Leonard was ten years old, Samuel's sister Clara deposited her upright piano at her brother's house. Bernstein began teaching himself piano and music theory and was soon clamoring for lessons. He had a variety of piano teachers in his youth, including Helen Coates, who later became his secretary. In the summers, the Bernstein family would go to their vacation home in

Sharon, Massachusetts

Sharon is a New England town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 18,575 at the 2020 census. Sharon is part of Greater Boston, about southwest of downtown Boston, and is connected to both Boston and Providence by ...

, where young Leonard conscripted all the neighborhood children to put on shows ranging from Bizet's ''

Carmen

''Carmen'' () is an opera in four acts by the French composer Georges Bizet. The libretto was written by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on the Carmen (novella), novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. The opera was first perfo ...

'' to Gilbert and Sullivan's ''

The Pirates of Penzance

''The Pirates of Penzance; or, The Slave of Duty'' is a comic opera in two acts, with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert. Its official premiere was at the Fifth Avenue Theatre in New York City on 31 December 187 ...

''. He would often play entire operas or

Beethoven symphonies

The compositions of Ludwig van Beethoven consist of 722 works written over forty-five years, from his earliest work in 1782 (variations for piano on a march by Ernst Christoph Dressler) when he was only eleven years old and still in Bonn, until hi ...

with his younger sister Shirley. Leonard's youngest sibling, Burton, was born in 1932, thirteen years after Leonard. Despite the large span in age, the three siblings remained close their entire lives.

Sam was initially opposed to young Leonard's interest in music and attempted to discourage his son's interest by refusing to pay for his piano lessons. Leonard then took to giving lessons to young people in his neighborhood. One of his students,

Sid Ramin, became Bernstein's most frequent orchestrator and lifelong beloved friend.

Sam took his son to orchestral concerts in his teenage years and eventually supported his music education. In May 1932, Leonard attended his first orchestral concert with the

Boston Pops Orchestra

The Boston Pops Orchestra is an American orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts, specializing in light classical and popular music. The orchestra's current music director is Keith Lockhart.

Founded in 1885 as an offshoot of the Boston Symp ...

conducted by

Arthur Fiedler

Arthur Fiedler (December 17, 1894 – July 10, 1979) was an American conductor known for his association with both the Boston Symphony and Boston Pops orchestras. With a combination of musicianship and showmanship, he made the Boston Pops one ...

. Bernstein recalled, "To me, in those days, the Pops was heaven itself ... I thought ... it was the supreme achievement of the human race." It was at this concert that Bernstein first heard Ravel's ''

Boléro'', which made a tremendous impression on him.

Another strong musical influence was

George Gershwin

George Gershwin (; born Jacob Gershwine; September 26, 1898 – July 11, 1937) was an American composer and pianist whose compositions spanned popular, jazz and classical genres. Among his best-known works are the orchestral compositions ' ...

. Bernstein was a counselor at a summer camp when news came over the radio of Gershwin's death. In the mess hall, a shaken Bernstein demanded a moment of silence, and then played Gershwin's second

''Prelude'' as a memorial.

On March 30, 1932, Bernstein played Brahms's

''Rhapsody in G minor'' at his first public piano performance in Susan Williams's studio recital at the

New England Conservatory

The New England Conservatory of Music (NEC) is a private music school in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the oldest independent music conservatory in the United States and among the most prestigious in the world. The conservatory is located on Hu ...

. Two years later, he made his solo debut with orchestra in Grieg's

Piano Concerto in A minor

The Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16, composed by Edvard Grieg in 1868, was the only concerto Grieg completed. It is one of his most popular works and is among the most popular of the genre.

Structure

The concerto is in three movements:

...

with the Boston Public School Orchestra.

1935–1940: College years

Bernstein's first two education environments were both public schools: the

William Lloyd Garrison School, followed by the prestigious

Boston Latin School

The Boston Latin School is a public exam school in Boston, Massachusetts. It was established on April 23, 1635, making it both the oldest public school in the British America and the oldest existing school in the United States. Its curriculum f ...

, for which Bernstein and classmate Lawrence F. Ebb wrote the Class Song.

Harvard University

In 1935, Bernstein enrolled at

Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

, where he studied music with, among others,

Edward Burlingame Hill and

Walter Piston

Walter Hamor Piston, Jr. (January 20, 1894 – November 12, 1976), was an American composer of classical music, music theorist, and professor of music at Harvard University.

Life

Piston was born in Rockland, Maine at 15 Ocean Street to Walter Ha ...

. His first extant composition,

Psalm 148

Psalm 148 is the 148th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "Praise ye the Lord from the heavens". In Latin, it is known as "Laudate Dominum de caelis". The psalm is one of the Laudate psalms. Old Testamen ...

set for voice and piano, is dated in 1935. He majored in music with a final year thesis titled "The Absorption of Race Elements into American Music" (1939; reproduced in his book ''Findings''). One of Bernstein's intellectual influences at Harvard was the

aesthetics

Aesthetics, or esthetics, is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of beauty and taste, as well as the philosophy of art (its own area of philosophy that comes out of aesthetics). It examines aesthetic values, often expressed thr ...

Professor

David Prall

David Wight Prall (1886–1940) was a philosopher of art and an academic. His interests include aesthetics, value theory, abstract ideas, truth and the history of philosophy. He is noted for his notion of aesthetic surfaces.

Biography

Prall was ...

, whose multidisciplinary outlook on the arts inspired Bernstein for the rest of his life.

One of his friends at Harvard was future philosopher

Donald Davidson, with whom Bernstein played piano duets. Bernstein wrote and conducted the musical score for the production Davidson mounted of

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or ( grc, δῆμος, plural: demoi, δημοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Athens and other city-states ...

' play ''

The Birds'', performed in the original Greek. Bernstein recycled some of this music in future works.

While a student, he was briefly an accompanist for the

Harvard Glee Club

The Harvard Glee Club is a 60-voice, Tenor-Bass choral ensemble at Harvard University. Founded in 1858 in the tradition of English and American glee clubs, it is the oldest collegiate chorus in the United States. The Glee Club is part of the H ...

as well as an unpaid pianist for Harvard Film Society's silent film presentations.

Bernstein mounted a student production of ''

The Cradle Will Rock

''The Cradle Will Rock'' is a 1937 play in music by Marc Blitzstein. Originally a part of the Federal Theatre Project, it was directed by Orson Welles and produced by John Houseman. A Brechtian allegory of corruption and corporate greed, it ...

'', directing its action from the piano as the composer

Marc Blitzstein had done at the infamous premiere. Blitzstein, who attended the performance, subsequently became a close friend and mentor to Bernstein.

As a sophomore at Harvard, Bernstein met the conductor

Dimitri Mitropoulos

Dimitri Mitropoulos ( el, Δημήτρης Μητρόπουλος; The dates 18 February 1896 and 1 March 1896 both appear in the literature. Many of Mitropoulos's early interviews and program notes gave 18 February. In his later interviews, howe ...

. Mitropoulos's charisma and power as a musician were major influences on Bernstein's eventual decision to become a conductor. Mitropoulos invited Bernstein to come to Minneapolis for the 1940–41 season to be his assistant, but the plan fell through due to union issues.

In 1937, Bernstein sat next to

Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

at a dance recital at

Town Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses ...

in New York City. Copland invited Bernstein to his birthday party afterwards, where Bernstein impressed the guests by playing Copland's challenging

Piano Variations, a work Bernstein loved. Although he was never a formal student of Copland's, Bernstein would regularly seek his advice, often citing him as his "only real composition teacher".

[See for instance Bernstein's 1980 TV Documentary, ''Teachers and Teaching'' available on a Deutsche Grammophon DVD.]

Bernstein graduated from Harvard in 1939 with a

Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

''cum laude''.

Curtis Institute of Music

After graduating from Harvard, Bernstein enrolled at the

Curtis Institute of Music

The Curtis Institute of Music is a private conservatory in Philadelphia. It offers a performance diploma, Bachelor of Music, Master of Music in opera, and a Professional Studies Certificate in opera. All students attend on full scholarship.

Hi ...

in

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. At Curtis, Bernstein studied conducting with

Fritz Reiner

Frederick Martin "Fritz" Reiner (December 19, 1888 – November 15, 1963) was a prominent conductor of opera and symphonic music in the twentieth century. Hungarian born and trained, he emigrated to the United States in 1922, where he rose to ...

(who anecdotally is said to have given Bernstein the only "A" grade he ever awarded); piano with

Isabelle Vengerova

Isabelle Vengerova ( be, Ізабэла Венгерава; 7 February 1956) was a Russian, later American, pianist and music teacher.

She was born Izabella Afanasyevna Vengerova (Изабелла Афанасьевна Венгерова) in M ...

; orchestration with

Randall Thompson

Randall Thompson (April 21, 1899 – July 9, 1984) was an American composer, particularly noted for his choral works.

Career

Randall attended The Lawrenceville School, where his father was an English teacher. He then attended Harvard University, ...

; counterpoint with

Richard Stöhr; and score reading with Renée Longy Miquelle.

In 1940, Bernstein attended the inaugural year of the

Tanglewood Music Center

The Tanglewood Music Center is an annual summer music academy in Lenox, Massachusetts, United States, in which emerging professional musicians participate in performances, master classes and workshops. The center operates as a part of the Tanglew ...

(then called the Berkshire Music Center) at the

Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is an American orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the second-oldest of the five major American symphony orchestras commonly referred to as the " Big Five". Founded by Henry Lee Higginson in 1881, ...

's summer home. Bernstein studied conducting with the BSO's music director,

Serge Koussevitzky, who became a profound lifelong inspiration to Bernstein. He became Koussevitzky's conducting assistant at Tanglewood and later dedicated his

Symphony No. 2: ''The Age of Anxiety'' to his beloved mentor. One of Bernstein's classmates, both at Curtis and at Tanglewood, was

Lukas Foss

Lukas Foss (August 15, 1922 – February 1, 2009) was a German-American composer, pianist, and conductor.

Career

Born Lukas Fuchs in Berlin, Germany in 1922, Foss was soon recognized as a child prodigy. He began piano and theory lessons with J ...

, who remained a lifelong friend and colleague. Bernstein returned to Tanglewood nearly every summer for the rest of his life to teach and conduct the young music students.

Life and career

1940s

Soon after he left Curtis, Bernstein moved to New York City where he lived in various apartments in

Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

. Bernstein supported himself by coaching singers, teaching piano,

and playing the piano for dance classes in Carnegie Hall. He found work with Harms-Witmark, transcribing jazz and pop music and publishing his work under the pseudonym "Lenny Amber". (''Bernstein'' means "

amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In Ma ...

" in German.)

Bernstein briefly shared an apartment in

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

with his friend

Adolph Green

Adolph Green (December 2, 1914 – October 23, 2002) was an American lyricist and playwright who, with long-time collaborator Betty Comden, penned the screenplays and songs for some of the most beloved film musicals, particularly as part of Art ...

. Green was then part of a satirical music troupe called The Revuers, featuring

Betty Comden

Betty Comden (May 3, 1917 - November 23, 2006) was an American lyricist, playwright, and screenwriter who contributed to numerous Hollywood musicals and Broadway shows of the mid-20th century. Her writing partnership with Adolph Green spanned s ...

and

Judy Holliday

Judy Holliday (born Judith Tuvim, June 21, 1921 – June 7, 1965) was an American actress, comedian and singer.Obituary '' Variety'', June 9, 1965, p. 71.

She began her career as part of a nightclub act before working in Broadway plays and mus ...

. With Bernstein sometimes providing piano accompaniment, the Revuers often performed at the legendary jazz club the

Village Vanguard

The Village Vanguard is a jazz club at Seventh Avenue South in Greenwich Village, New York City. The club was opened on February 22, 1935, by Max Gordon. Originally, the club presented folk music and beat poetry, but it became primarily a jazz ...

.

On April 21, 1942, Bernstein performed the premiere of his first published work,

''Sonata for Clarinet and Piano'', with clarinetist David Glazer at the

Institute of Modern Art

The Institute of Modern Art (IMA) is a public art gallery located in the Judith Wright Arts Centre in the Brisbane inner-city suburb of Fortitude Valley, which features contemporary artworks and showcases emerging artists in a series of group an ...

in Boston.

New York Philharmonic conducting debut

On November 14, 1943, having recently been appointed assistant conductor to

Artur Rodziński

Artur Rodziński (2 January 1892 – 27 November 1958) was a Polish-American conductor of orchestral music and opera. He began his career after World War I in Poland, where he was discovered by Leopold Stokowski, who invited him to be his ass ...

of the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein made his major conducting debut at short notice—and without any rehearsal—after guest conductor

Bruno Walter

Bruno Walter (born Bruno Schlesinger, September 15, 1876February 17, 1962) was a German-born conductor, pianist and composer. Born in Berlin, he escaped Nazi Germany in 1933, was naturalised as a French citizen in 1938, and settled in the Un ...

came down with the flu. The challenging program included works by

Robert Schumann

Robert Schumann (; 8 June 181029 July 1856) was a German composer, pianist, and influential music critic. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest composers of the Romantic era. Schumann left the study of law, intending to pursue a career a ...

,

Miklós Rózsa

Miklós Rózsa (; April 18, 1907 – July 27, 1995) was a Hungarian-American composer trained in Germany (1925–1931) and active in France (1931–1935), the United Kingdom (1935–1940), and the United States (1940–1995), with extensi ...

,

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most op ...

, and

Richard Strauss

Richard Georg Strauss (; 11 June 1864 – 8 September 1949) was a German composer, conductor, pianist, and violinist. Considered a leading composer of the late Romantic and early modern eras, he has been described as a successor of Richard Wag ...

.

The next day, ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' carried the story on its front page and remarked in an editorial, "It's a good American success story. The warm, friendly triumph of it filled

Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

and spread far over the air waves."

Many newspapers throughout the country carried the story, which, in combination with the concert's live national

CBS Radio

CBS Radio was a radio broadcasting company and radio network operator owned by CBS Corporation and founded in 1928, with consolidated radio station groups owned by CBS and Westinghouse Broadcasting/Group W since the 1920s, and Infinity Broadc ...

Network broadcast, propelled Bernstein to instant fame.

Over the next two years, Bernstein made conducting debuts with ten different orchestras in the United States and Canada, greatly broadening his repertoire and initiating a lifelong frequent practice of conducting concertos from the piano.

Symphony No. 1: ''Jeremiah'', ''Fancy Free'', and ''On the Town''

On January 28, 1944, he conducted the premiere of his

Symphony No. 1: ''Jeremiah'' with the

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

The ''Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra'' (''PSO'') is an American orchestra based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The orchestra's home is Heinz Hall, located in Pittsburgh's Cultural District.

History

The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra is an America ...

with Jennie Tourel as soloist.

In the fall of 1943, Bernstein and

Jerome Robbins

Jerome Robbins (born Jerome Wilson Rabinowitz; October 11, 1918 – July 29, 1998) was an American dancer, choreographer, film director, theatre director and producer who worked in classical ballet, on stage, film, and television.

Among his nu ...

began work on their first collaboration, ''

Fancy Free Fancy Free may refer to:

Music

* Fancy Free (Donald Byrd album), ''Fancy Free'' (Donald Byrd album) (1969)

* Fancy Free (Richard Davis album), ''Fancy Free'' (Richard Davis album) (1977)

* Fancy Free (The Oak Ridge Boys album), ''Fancy Free'' (Th ...

'', a ballet about three young sailors on leave in wartime New York City. ''Fancy Free'' premiered on April 18, 1944, with the

Ballet Theatre (now the American Ballet Theatre) at the old

Metropolitan Opera House, with scenery by

Oliver Smith and costumes by

Kermit Love.

Bernstein and Robbins decided to expand the ballet into a musical and invited Comden and Green to write the book and lyrics. ''

On the Town'' opened on Broadway's

Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiv ...

on December 28, 1944. The show resonated with audiences during World War II, and it broke race barriers on Broadway: Japanese-American dancer

Sono Osato

was an American dancer and actress.

Early life

Osato was born in Omaha, Nebraska. She was the oldest of three children of a Japanese father (Shoji Osato, 1885–1955) and an Irish-French Canadian mother (Frances Fitzpatrick, 1897–1954).The G ...

in a leading role; a multiracial cast dancing as mixed race couples; and a Black concertmaster,

Everett Lee, who eventually took over as music director of the show. ''On the Town'' became

an MGM motion picture in 1949, starring

Gene Kelly

Eugene Curran Kelly (August 23, 1912 – February 2, 1996) was an American actor, dancer, singer, filmmaker, and choreographer. He was known for his energetic and athletic dancing style and sought to create a new form of American dance accessibl ...

,

Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Nicknamed the "Honorific nicknames in popular music, Chairman of the Board" and later called "Ol' Blue Eyes", Sinatra was one of the most popular ...

, and

Jules Munshin

Jules Munshin (February 22, 1915 – February 19, 1970) was an American actor, comedian and singer who had made his name on Broadway when he starred in '' Call Me Mister''. His additional Broadway credits include '' The Gay Life'' and ''Barefo ...

as the three sailors. Only part of Bernstein's score was used in the film and additional songs were provided by

Roger Edens

Roger Edens (November 9, 1905 – July 13, 1970) was a Hollywood composer, arranger and associate producer, and is considered one of the major creative figures in Arthur Freed's musical film production unit at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer during the "go ...

.

Rising conducting career

From 1945 to 1947, Bernstein was the music director of the New York City Symphony, which had been founded the previous year by the conductor

Leopold Stokowski

Leopold Anthony Stokowski (18 April 1882 – 13 September 1977) was a British conductor. One of the leading conductors of the early and mid-20th century, he is best known for his long association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and his appeara ...

. The orchestra (with support from Mayor Fiorello La Guardia) had modern programs and affordable tickets.

In 1946, he made his overseas debut with the

Czech Philharmonic in Prague. He also recorded Ravel's

Piano Concerto in G as soloist and conductor with the

Philharmonia Orchestra

The Philharmonia Orchestra is a British orchestra based in London. It was founded in 1945 by Walter Legge, a classical music record producer for EMI. Among the conductors who worked with the orchestra in its early years were Richard Strauss, W ...

. On July 4, 1946, Bernstein conducted the European premiere of ''Fancy Free'' with the Ballet Theatre at the

Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House (ROH) is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply Covent Garden, after a previous use of the site. It is the home of The Royal Op ...

in London.

In 1946, he conducted opera professionally for the first time at Tanglewood with the American premiere of

Benjamin Britten

Edward Benjamin Britten, Baron Britten (22 November 1913 – 4 December 1976, aged 63) was an English composer, conductor, and pianist. He was a central figure of 20th-century British music, with a range of works including opera, other ...

's ''

Peter Grimes

''Peter Grimes'', Op. 33, is an opera in three acts by Benjamin Britten, with a libretto by Montagu Slater based on the section "Peter Grimes", in George Crabbe's long narrative poem '' The Borough''. The "borough" of the opera is a fictional ...

'', which was commissioned by Koussevitzky. That same year,

Arturo Toscanini

Arturo Toscanini (; ; March 25, 1867January 16, 1957) was an Italian conductor. He was one of the most acclaimed and influential musicians of the late 19th and early 20th century, renowned for his intensity, his perfectionism, his ear for orch ...

invited Bernstein to guest conduct two concerts with the

NBC Symphony Orchestra

The NBC Symphony Orchestra was a radio orchestra conceived by David Sarnoff, the president of the Radio Corporation of America, especially for the conductor Arturo Toscanini. The NBC Symphony performed weekly radio concert broadcasts with Tosca ...

, one of which featured Bernstein as soloist in

Ravel

Joseph Maurice Ravel (7 March 1875 – 28 December 1937) was a French composer, pianist and conductor. He is often associated with Impressionism along with his elder contemporary Claude Debussy, although both composers rejected the term. In ...

's Piano Concerto in G.

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

In 1947, Bernstein conducted in

Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

for the first time, beginning a lifelong association with the

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra

The Israel Philharmonic Orchestra (abbreviation IPO; Hebrew: התזמורת הפילהרמונית הישראלית, ''ha-Tizmoret ha-Filharmonit ha-Yisra'elit'') is an Israeli symphony orchestra based in Tel Aviv. Its principal concert venue ...

, then known as the Palestine Symphony Orchestra. The next year he conducted an open-air concert for Israeli troops at

Beersheba

Beersheba or Beer Sheva, officially Be'er-Sheva ( he, בְּאֵר שֶׁבַע, ''Bəʾēr Ševaʿ'', ; ar, بئر السبع, Biʾr as-Sabʿ, Well of the Oath or Well of the Seven), is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. ...

in the middle of the desert during the

Arab-Israeli war

The Arab citizens of Israel are the largest ethnic minority in the country. They comprise a hybrid community of Israeli citizens with a heritage of Palestinian citizenship, mixed religions (Muslim, Christian or Druze), bilingual in Arabic an ...

. In 1957, he conducted the inaugural concert of the

Mann Auditorium

Heichal HaTarbut ( he, היכל התרבות), also known in English as the Culture Palace, officially the Charles Bronfman Auditorium, until 2013 the Fredric R. Mann Auditorium, is the largest concert hall in Tel Aviv, Israel, and home to the ...

in Tel Aviv. In 1967, he conducted a concert on

Mount Scopus

Mount Scopus ( he, הַר הַצּוֹפִים ', "Mount of the Watchmen/ Sentinels"; ar, جبل المشارف ', lit. "Mount Lookout", or ' "Mount of the Scene/Burial Site", or ) is a mountain (elevation: above sea level) in northeast Je ...

to commemorate the

Reunification of Jerusalem

The Israeli annexation of East Jerusalem, known to Israelis as the reunification of Jerusalem, refers to the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem during the 1967 Six-Day War, and its annexation.

Jerusalem was envisaged as a separate, internati ...

, featuring Mahler's Symphony No. 2 and Mendelssohn Violin Concerto with soloist

Isaac Stern

Isaac Stern (July 21, 1920 – September 22, 2001) was an American violinist.

Born in Poland, Stern came to the US when he was 14 months old. Stern performed both nationally and internationally, notably touring the Soviet Union and China, and ...

. The city of Tel Aviv added his name to the

Habima Square

Habima Square ( he, כיכר הבימה, lit. ''The Stage's Square'', also known as The Orchestra Plaza) is a public major space in the center of Tel Aviv, Israel, which is home to a number of cultural institutions such as the Habima Theatre, the ...

(Orchestra Plaza) in the center of the city.

First television appearance

On December 10, 1949, he made his first television appearance as conductor with the

Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is an American orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the second-oldest of the five major American symphony orchestras commonly referred to as the " Big Five". Founded by Henry Lee Higginson in 1881, ...

at

Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

. The concert, which included an address by

Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt () (October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the first lady of the United States from 1933 to 1945, during her husband President Franklin D. Roosevelt's four ...

, celebrated the one-year anniversary of the

United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

's ratification of the

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal De ...

, and included the premiere of

Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

's "Preamble" with

Sir Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the British stage ...

narrating text from the

UN Charter

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

. The concert was televised by

NBC Television Network

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American English-language commercial broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a division of Comcast, its headquarters are l ...

.

Summer at Tanglewood

In April 1949, Bernstein performed as piano soloist in the world premiere of his

Symphony No. 2: The Age of Anxiety with Koussevitzy conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Later that year, Bernstein conducted the world premiere of the ''

Turangalîla-Symphonie

The ''Turangalîla-Symphonie'' is the only symphony by Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992). It was written for an orchestra of large forces from 1946 to 1948 on a commission by Serge Koussevitzky in his wife's memory for the Boston Symphony Orches ...

'' by

Olivier Messiaen

Olivier Eugène Prosper Charles Messiaen (, ; ; 10 December 1908 – 27 April 1992) was a French composer, organist, and ornithologist who was one of the major composers of the 20th century. His music is rhythmically complex; harmonically ...

, with the

Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) is an American orchestra based in Boston, Massachusetts. It is the second-oldest of the five major American symphony orchestras commonly referred to as the " Big Five". Founded by Henry Lee Higginson in 1881, ...

. Part of the rehearsal for the concert was recorded and released by the orchestra. When Koussevitzky died in 1951, Bernstein became head of the orchestra and conducting departments at

Tanglewood

Tanglewood is a music venue in the towns of Lenox and Stockbridge in the Berkshire Hills of western Massachusetts. It has been the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra since 1937. Tanglewood is also home to three music schools: the ...

.

1950s

The 1950s comprised among the most active years of Bernstein's career. He created five new works for the Broadway stage; he composed several symphonic works and an iconic film score; he was appointed music director of the New York Philharmonic with whom he toured the world, including concerts behind the Iron Curtain; he harnessed the power of television to expand his educational reach; and he married and started a family.

Compositions in the 1950s

= Theatrical works

=

''Peter Pan''

In 1950, Bernstein composed incidental music for a Broadway production of J. M. Barrie's play ''

Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a fictional character created by List of Scottish novelists, Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie. A free-spirited and mischievous young boy who can fly and Puer aeternus, never grows up, Peter Pan spends his never-ending ...

''. The production, which opened on Broadway on April 24, 1950, starred

Jean Arthur

Jean Arthur (born Gladys Georgianna Greene; October 17, 1900 – June 19, 1991) was an American Broadway and film actress whose career began in silent films in the early 1920s and lasted until the early 1950s.

Arthur had feature roles in three F ...

as

Peter Pan

Peter Pan is a fictional character created by List of Scottish novelists, Scottish novelist and playwright J. M. Barrie. A free-spirited and mischievous young boy who can fly and Puer aeternus, never grows up, Peter Pan spends his never-ending ...

and

Boris Karloff

William Henry Pratt (23 November 1887 – 2 February 1969), better known by his stage name Boris Karloff (), was an English actor. His portrayal of Frankenstein's monster in the horror film ''Frankenstein'' (1931) (his 82nd film) established h ...

in the dual roles of

George Darling

George Darling, Baron Darling of Hillsborough, PC (20 July 1905 – 18 October 1985) was a politician in the United Kingdom. He was Labour Co-operative Member of Parliament for Sheffield Hillsborough from 1950 to 1974.

Early life and education ...

and

Captain Hook

Captain James Hook is a fictional character and the main antagonist of J. M. Barrie's 1904 play ''Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up'' and its various adaptations, in which he is Peter Pan's archenemy. The character is a pirate capta ...

. The show ran for 321 performances.

''Trouble in Tahiti''

In 1951, Bernstein composed ''Trouble in Tahiti'', a one-act

opera

Opera is a form of theatre in which music is a fundamental component and dramatic roles are taken by singers. Such a "work" (the literal translation of the Italian word "opera") is typically a collaboration between a composer and a librett ...

in seven scenes with an English

libretto

A libretto (Italian for "booklet") is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or Musical theatre, musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the t ...

by the composer. The opera portrays the troubled marriage of a couple whose idyllic suburban post-war environment belies their inner turmoil. Ironically, Bernstein wrote most of the opera while on his honeymoon in Mexico with his wife,

Felicia Montealegre

Felicia Montealegre Bernstein (6 February 1922 – 16 June 1978) was a Chilean-American stage and television actress born in San Jose, Costa Rica. From 1951 until her death, she was married to the American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein ...

.

Bernstein was a visiting music professor at

Brandeis University

, mottoeng = "Truth even unto its innermost parts"

, established =

, type = Private research university

, accreditation = NECHE

, president = Ronald D. Liebowitz

, pro ...

from 1951 to 1956. In 1952, he created the

Brandeis Festival of the Creative Arts, where he conducted the premiere of ''

Trouble in Tahiti

''Trouble in Tahiti'' is a one-act opera in seven scenes composed by Leonard Bernstein with an English libretto by the composer. It is the darkest among Bernstein's "musicals", and one of only two for which he wrote the words and the music. (He ...

'' on June 12 of that year.

The

NBC Opera Theatre The NBC Opera Theatre (sometimes mistakenly spelled NBC Opera Theater and sometimes referred to as the NBC Opera Company) was an American opera company operated by the National Broadcasting Company from 1949 to 1964. The company was established spec ...

subsequently presented the opera on television in November 1952. It opened on Broadway at the Playhouse Theatre on April 19, 1955, and ran for six weeks.

Three decades later, Bernstein wrote a second opera, ''

A Quiet Place

''A Quiet Place'' is a 2018 American post-apocalyptic horror film directed by John Krasinski and written by Bryan Woods, Scott Beck and Krasinski, from a story conceived by Woods and Beck. The plot revolves around a father (Krasinski) and a mo ...

'', which picked up the story and characters of ''Trouble in Tahiti'' in a later period.

''Wonderful Town''

In 1953, Bernstein wrote the score for the musical ''

Wonderful Town

''Wonderful Town'' is a 1953 musical with book written by Joseph A. Fields and Jerome Chodorov, lyrics by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, and music by Leonard Bernstein. The musical tells the story of two sisters who aspire to be a writer and act ...

'' on very short notice, with a book by

Joseph A. Fields and

Jerome Chodorov

Jerome Chodorov (August 10, 1911 – September 12, 2004) was an American playwright, librettist, and screenwriter. He co-wrote the book with Joseph A. Fields for the original Broadway musical ''Wonderful Town'' starring Rosalind Russell. The musi ...

and lyrics by

Betty Comden

Betty Comden (May 3, 1917 - November 23, 2006) was an American lyricist, playwright, and screenwriter who contributed to numerous Hollywood musicals and Broadway shows of the mid-20th century. Her writing partnership with Adolph Green spanned s ...

and

Adolph Green

Adolph Green (December 2, 1914 – October 23, 2002) was an American lyricist and playwright who, with long-time collaborator Betty Comden, penned the screenplays and songs for some of the most beloved film musicals, particularly as part of Art ...

. The musical tells the story of two sisters from Ohio who move to New York City and seek success from their squalid

basement apartment

A basement apartment is an apartment located below street level, underneath another structure—usually an apartment building, but possibly a house or a business. Cities in North America are beginning to recognize these units as a vital source ...

in

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

.

''Wonderful Town'' opened on

Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

on February 25, 1953, at the

Winter Garden Theatre

The Winter Garden Theatre is a Broadway theatre at 1634 Broadway in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It opened in 1911 under designs by architect William Albert Swasey. The Winter Garden's current design dates to 1922, when ...

, starring

Rosalind Russell

Catherine Rosalind Russell (June 4, 1907November 28, 1976) was an American actress, comedienne, screenwriter, and singer,Obituary ''Variety'', December 1, 1976, p. 79. known for her role as fast-talking newspaper reporter Hildy Johnson in the H ...

in the role of Ruth Sherwood,

Edie Adams

Edie Adams (born Edith Elizabeth Enke; April 16, 1927 – October 15, 2008) was an American comedian, actress, singer and businesswoman. She earned the Tony Award and was nominated for an Emmy Award.

Adams was well known for her impersonations ...

as Eileen Sherwood, and

George Gaynes

George Gaynes (born George Jongejans; May 16, 1917 – February 15, 2016) was a Finnish-born American singer, actor, and voice artist. Born to Dutch and Russian-Finnish parents in the Grand Duchy of Finland of the Russian Empire, he served in the ...

as Robert Baker. It won five

Tony Awards

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual cer ...

, including Best Musical and Best Actress.

''Candide''

In the three years leading up to Bernstein's appointment as music director of the New York Philharmonic, Bernstein was simultaneously working on the scores for two Broadway shows. The first of the two was the

operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs, and dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, length of the work, and at face value, subject matter. Apart from its s ...

-style musical ''

Candide

( , ) is a French satire written by Voltaire, a philosopher of the Age of Enlightenment, first published in 1759. The novella has been widely translated, with English versions titled ''Candide: or, All for the Best'' (1759); ''Candide: or, The ...

.''

Lillian Hellman

Lillian Florence Hellman (June 20, 1905 – June 30, 1984) was an American playwright, prose writer, memoirist and screenwriter known for her success on Broadway, as well as her communist sympathies and political activism. She was blacklisted aft ...

originally brought Bernstein her idea of adapting

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778) was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher. Known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' M. de Voltaire (; also ; ), he was famous for his wit, and his ...

's

novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

. The original collaborators on the show were book writer

John Latouche and lyricist

Richard Wilbur

Richard Purdy Wilbur (March 1, 1921 – October 14, 2017) was an American poet and literary translator. One of the foremost poets of his generation, Wilbur's work, composed primarily in traditional forms, was marked by its wit, charm, and gentle ...

.

''Candide'' opened on

Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

on December 1, 1956, at the

Martin Beck Theatre, in a production directed by

Tyrone Guthrie

Sir William Tyrone Guthrie (2 July 1900 – 15 May 1971) was an English theatrical director instrumental in the founding of the Stratford Festival of Canada, the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at his ...

. Anxious about the parallels Hellman had deliberately drawn between Voltaire's story and the ongoing hearings conducted by the

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly dubbed the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloy ...

, Guthrie persuaded the collaborators to cut their most incendiary sections prior to opening night.

While the production was a box office disaster, running for only two months for a total of 73 performances, the cast album became a cult classic, which kept Bernstein's score alive. There have been several revivals, with modifications to improve the book.

The elements of the music that have remained best known and performed over the decades are the Overture, which quickly became one of the most frequently performed orchestral compositions by a

20th century

The 20th (twentieth) century began on

January 1, 1901 ( MCMI), and ended on December 31, 2000 ( MM). The 20th century was dominated by significant events that defined the modern era: Spanish flu pandemic, World War I and World War II, nuclear ...

American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

composer; the coloratura aria "Glitter and Be Gay", which

Barbara Cook

Barbara Cook (October 25, 1927 – August 8, 2017) was an American actress and singer who first came to prominence in the 1950s as the lead in the original Broadway musicals '' Plain and Fancy'' (1955), ''Candide'' (1956) and ''The Music Man'' ( ...

sang in the original production; and the grand finale "Make Our Garden Grow".

''West Side Story''

The other musical Bernstein was writing simultaneously with ''Candide'' was ''

West Side Story

''West Side Story'' is a musical conceived by Jerome Robbins with music by Leonard Bernstein, lyrics by Stephen Sondheim, and a book by Arthur Laurents.

Inspired by William Shakespeare's play ''Romeo and Juliet'', the story is set in the mid-1 ...

''. Bernstein collaborated with director and choreographer

Jerome Robbins

Jerome Robbins (born Jerome Wilson Rabinowitz; October 11, 1918 – July 29, 1998) was an American dancer, choreographer, film director, theatre director and producer who worked in classical ballet, on stage, film, and television.

Among his nu ...

, book writer

Arthur Laurents

Arthur Laurents (July 14, 1917 – May 5, 2011) was an American playwright, theatre director, film producer and screenwriter.

After writing scripts for radio shows after college and then training films for the U.S. Army during World War II, ...

, and lyricist

Stephen Sondheim

Stephen Joshua Sondheim (; March 22, 1930November 26, 2021) was an American composer and lyricist. One of the most important figures in twentieth-century musical theater, Sondheim is credited for having "reinvented the American musical" with sho ...

.

The story is an updated retelling of Shakespeare's ''

Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetim ...

'', set in the mid-1950s in the slums of New York City's

Upper West Side

The Upper West Side (UWS) is a neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by Central Park on the east, the Hudson River on the west, West 59th Street to the south, and West 110th Street to the north. The Upper West ...

. The Romeo character, Tony, is affiliated with the Jets gang, who are of white Northern European descent. The Juliet character is Maria, who is connected to the Sharks gang, recently arrived immigrants from

Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

.

The original Broadway production opened at the

Winter Garden Theatre

The Winter Garden Theatre is a Broadway theatre at 1634 Broadway in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It opened in 1911 under designs by architect William Albert Swasey. The Winter Garden's current design dates to 1922, when ...

on September 26, 1957, and ran 732 performances. Robbins won the

Tony Award

The Antoinette Perry Award for Excellence in Broadway Theatre, more commonly known as the Tony Award, recognizes excellence in live Broadway theatre. The awards are presented by the American Theatre Wing and The Broadway League at an annual cer ...

for Best Choreographer, and

Oliver Smith won the Tony for Best Scenic Designer.

Bernstein's score for ''West Side Story'' blends "jazz, Latin rhythms, symphonic sweep and musical-comedy conventions in groundbreaking ways for Broadway". It was

orchestrated

Orchestration is the study or practice of writing music for an orchestra (or, more loosely, for any musical ensemble, such as a concert band) or of adapting music composed for another medium for an orchestra. Also called "instrumentation", orch ...

by

Sid Ramin and

Irwin Kostal

Irwin Kostal (October 1, 1911 – November 23, 1994) was an American musical arranger of films and an orchestrator of Broadway musicals.

Biography

Born in Chicago, Illinois, Kostal attended Harrison Technical High School, but opted not to at ...

following detailed instructions from Bernstein. The dark theme, sophisticated music, extended dance scenes, and focus on social problems marked a turning point in musical theatre.

In 1960, Bernstein prepared a

suite of orchestral music from the show, titled ''Symphonic Dances from West Side Story'', which continues to be popular with orchestras worldwide.

A

1961 United Artists film adaptation, directed by

Robert Wise

Robert Earl Wise (September 10, 1914 – September 14, 2005) was an American film director, producer, and editor. He won the Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Picture for his musical films ''West Side Story'' (1961) and ''The Sound of ...

and Robbins and starred

Natalie Wood

Natalie Wood ( Zacharenko; July 20, 1938 – November 29, 1981) was an American actress who began her career in film as a child and successfully transitioned to young adult roles.

Wood started acting at age four and was given a co-starring r ...

as Maria and

Richard Beymer

George Richard Beymer Jr. (born February 20, 1938) is an American actor, filmmaker and artist who played the roles of Tony in the film version of ''West Side Story'' (1961), Peter in ''The Diary of Anne Frank'' (1959), and Ben Horne on the telev ...

as Tony. The film won ten

Academy Awards

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

, including

Best Picture

This is a list of categories of awards commonly awarded through organizations that bestow film awards, including those presented by various film, festivals, and people's awards.

Best Actor/Best Actress

*See Best Actor#Film awards, Best Actress#F ...

and a ground-breaking Best Supporting Actress award for Puerto Rican-born

Rita Moreno

Rita Moreno (born Rosa Dolores Alverío Marcano; December 11, 1931) is a Puerto Rican actress, dancer, and singer. Noted for her work across different areas of the entertainment industry, she has appeared in numerous film, television, and thea ...

playing the role of Anita.

A

new film adaptation directed by Steven Spielberg opened in 2021.

= ''Serenade'', ''Prelude, Fugue and Riffs'', and ''On The Waterfront''

=

In addition to Bernstein's compositional activity for the stage, he wrote a symphonic work, ''

Serenade after Plato's "Symposium"

The ''Serenade, after Plato's Symposium'', is a composition by Leonard Bernstein for solo violin, strings and percussion. He completed the serenade in five movements on August 7, 1954. For the serenade, the composer drew inspiration from Plato's ...

''; the score to the Academy Award-winning film

''On The Waterfront''; and ''

Prelude, Fugue and Riffs'', composed for jazz big band and solo clarinet''.''

First American to conduct at La Scala

In 1953, Bernstein became the first American conductor to appear at

La Scala

La Scala (, , ; abbreviation in Italian of the official name ) is a famous opera house in Milan, Italy. The theatre was inaugurated on 3 August 1778 and was originally known as the ' (New Royal-Ducal Theatre alla Scala). The premiere performan ...

in Milan, conducting Cherubini's ''

Medea

In Greek mythology, Medea (; grc, Μήδεια, ''Mēdeia'', perhaps implying "planner / schemer") is the daughter of King Aeëtes of Colchis, a niece of Circe and the granddaughter of the sun god Helios. Medea figures in the myth of Jason an ...

'', with

Maria Callas

Maria Callas . (born Sophie Cecilia Kalos; December 2, 1923 – September 16, 1977) was an American-born Greek soprano who was one of the most renowned and influential opera singers of the 20th century. Many critics praised her ''bel cant ...

in the title role. Callas and Bernstein reunited at La Scala to perform Bellini's ''

La sonnambula

''La sonnambula'' (''The Sleepwalker'') is an opera semiseria in two acts, with music in the ''bel canto'' tradition by Vincenzo Bellini set to an Italian libretto by Felice Romani, based on a scenario for a ''ballet-pantomime'' written by Eu ...

'' in 1955.

Omnibus

On November 14, 1954, Bernstein presented the first of his television lectures for the CBS Television Network arts program

''Omnibus''. The live lecture, entitled "Beethoven's Fifth Symphony", involved Bernstein explaining the symphony's first movement with the aid of musicians from the "Symphony of the Air" (formerly

NBC Symphony Orchestra

The NBC Symphony Orchestra was a radio orchestra conceived by David Sarnoff, the president of the Radio Corporation of America, especially for the conductor Arturo Toscanini. The NBC Symphony performed weekly radio concert broadcasts with Tosca ...

). The program featured manuscripts from Beethoven's own hand, as well as a giant painting of the first page of the score covering the studio floor. Six more Omnibus lectures followed from 1955 to 1961 (later on ABC and then NBC) covering a broad range of topics: jazz, conducting, American musical comedy, modern music, J.S. Bach, and

grand opera

Grand opera is a genre of 19th-century opera generally in four or five acts, characterized by large-scale casts and orchestras, and (in their original productions) lavish and spectacular design and stage effects, normally with plots based on o ...

.

Music director of the New York Philharmonic

Bernstein was appointed the music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1957, sharing the post jointly with

Dimitri Mitropoulos

Dimitri Mitropoulos ( el, Δημήτρης Μητρόπουλος; The dates 18 February 1896 and 1 March 1896 both appear in the literature. Many of Mitropoulos's early interviews and program notes gave 18 February. In his later interviews, howe ...

until he took sole charge in 1958. Bernstein held the music directorship until 1969 when he was appointed "Laureate Conductor". He continued to conduct and make recordings with the orchestra for the rest of his life.

= Young People's Concerts with the New York Philharmonic

=

Bernstein's television teaching took a quantum leap when, as the new music director of the New York Philharmonic, he put the orchestra's traditional Saturday afternoon ''

Young People's Concerts

The Young People's Concerts with the New York Philharmonic are the longest-running series of family concerts of classical music in the world.

Genesis

They began in 1924 under the direction of "Uncle" Ernest Schelling. Earlier Family Matinees had ...

'' on the CBS Television Network. Millions of viewers of all ages and around the world enthusiastically embraced Bernstein and his engaging presentations about classical music. Bernstein often presented talented young performers on the broadcasts. Many of them became celebrated in their own right, including conductors

Claudio Abbado

Claudio Abbado (; 26 June 1933 – 20 January 2014) was an Italian conductor who was one of the leading conductors of his generation. He served as music director of the La Scala opera house in Milan, principal conductor of the London Symphony ...

and

Seiji Ozawa

Seiji (written: , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , or in hiragana) is a masculine Japanese given name. Notable people with the name include:

*, Japanese ski jumper

*, Japanese racing driver

*, Japanese politician

*, Japanese film directo ...

; flutist

Paula Robison

Paula Robison (born June 8, 1941) is a flute soloist and teacher.

Early life and education

Paula Robison was born in Nashville, Tennessee, the daughter of David V. and Naomi Robison, an actor. David Robison was a playwright and writer for film ...

; and pianist

André Watts

André Watts (born June 20, 1946) is an American classical pianist and professor at the Jacobs School of Music of Indiana University. In 2020, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.

Life and early performances

Born in Nurember ...

. From 1958 until 1972, the fifty-three ''Young People's Concerts'' comprised the most influential series of music education programs ever produced on television. They were highly acclaimed by critics and won numerous

Emmy Awards

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

.

Some of Bernstein's scripts, all of which he wrote himself, were released in book form and on records. A recording of ''Humor in Music'' was awarded a

Grammy

The Grammy Awards (stylized as GRAMMY), or simply known as the Grammys, are awards presented by the Recording Academy of the United States to recognize "outstanding" achievements in the music industry. They are regarded by many as the most pre ...

award for Best Documentary or Spoken Word Recording (other than comedy) in 1961. The programs were shown in many countries around the world, often with Bernstein dubbed into other languages, and the concerts were later released on home video by

Kultur Video

Kultur Video is a film company that specializes in the distribution and production of performing arts, history, literature, theater, and other genres on DVD, Blu-ray, and Streaming Video. The company has issued famous television programs by such a ...

.

= United States Department of State tours

=

In 1958, Bernstein and Mitropoulos led the New York Philharmonic on its first tour south of the border, through 12 countries in Central and South America. The

United States Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other n ...

sponsored the tour to improve the nation's relations with its southern neighbors.

In 1959, the Department of State also sponsored Bernstein and the Philharmonic on a 50-concert tour through Europe and the Soviet Union, portions of which were filmed by the

CBS Television Network

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainme ...

. A highlight of the tour was Bernstein's performance of

Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throughout his life as a major compo ...

's

Fifth Symphony, in the presence of the composer, who came on stage at the end to congratulate Bernstein and the musicians.

1960s

New York Philharmonic Innovations

Bernstein's innovative approach to themed programming included introducing audiences to lesser performed composers at the time such as

Gustav Mahler

Gustav Mahler (; 7 July 1860 – 18 May 1911) was an Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer, and one of the leading conductors of his generation. As a composer he acted as a bridge between the 19th-century Austro-German tradition and the modernism ...

,

Carl Nielsen

Carl August Nielsen (; 9 June 1865 – 3 October 1931) was a Danish composer, conductor and violinist, widely recognized as his country's most prominent composer.

Brought up by poor yet musically talented parents on the island of Funen, he ...

,

Jean Sibelius

Jean Sibelius ( ; ; born Johan Julius Christian Sibelius; 8 December 186520 September 1957) was a Finnish composer of the late Romantic and 20th-century classical music, early-modern periods. He is widely regarded as his country's greatest com ...

, and

Charles Ives

Charles Edward Ives (; October 20, 1874May 19, 1954) was an American modernist composer, one of the first American composers of international renown. His music was largely ignored during his early career, and many of his works went unperformed f ...

(including the world premiere of his

Symphony No. 2). Bernstein actively advocated for the commission and performance of works by contemporary composers, conducting over 40 world premieres by a diverse roster of composers ranging from

John Cage

John Milton Cage Jr. (September 5, 1912 – August 12, 1992) was an American composer and music theorist. A pioneer of indeterminacy in music, electroacoustic music, and non-standard use of musical instruments, Cage was one of the leading fi ...

to

Alberto Ginastera

Alberto Evaristo Ginastera (; April 11, 1916June 25, 1983) was an Argentinian composer of classical music. He is considered to be one of the most important 20th-century classical composers of the Americas.

Biography

Ginastera was born in Buen ...

to

Luciano Berio

Luciano Berio (24 October 1925 – 27 May 2003) was an Italian composer noted for his experimental work (in particular his 1968 composition ''Sinfonia'' and his series of virtuosic solo pieces titled '' Sequenza''), and for his pioneering work ...

. He also conducted US premieres of 19 major works from around the globe, including works by

Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, , group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his Symphony No. 1 (Shostakovich), First Symphony in 1926 and was regarded throug ...

,

Pierre Boulez

Pierre Louis Joseph Boulez (; 26 March 1925 – 5 January 2016) was a French composer, conductor and writer, and the founder of several musical institutions. He was one of the dominant figures of post-war Western classical music.

Born in Mont ...

, and

György Ligeti

György Sándor Ligeti (; ; 28 May 1923 – 12 June 2006) was a Hungarian-Austrian composer of contemporary classical music. He has been described as "one of the most important avant-garde composers in the latter half of the twentieth century" ...

.

Bernstein championed American composers, especially with whom he had a close friendship, such as

Aaron Copland

Aaron Copland (, ; November 14, 1900December 2, 1990) was an American composer, composition teacher, writer, and later a conductor of his own and other American music. Copland was referred to by his peers and critics as "the Dean of American Com ...

,

William Schuman

William Howard Schuman (August 4, 1910February 15, 1992) was an American composer and arts administrator.

Life

Schuman was born into a Jewish family in Manhattan, New York City, son of Samuel and Rachel Schuman. He was named after the 27th U.S. ...

, and

David Diamond. This decade saw a significant expansion of Bernstein and the Philharmonic's collaboration with

Columbia Records

Columbia Records is an American record label owned by Sony Music, Sony Music Entertainment, a subsidiary of Sony Corporation of America, the North American division of Japanese Conglomerate (company), conglomerate Sony. It was founded on Janua ...

, together they released

over 400 compositions, covering a broad swath of the classical music canon.

Bernstein welcomed the Philharmonic's additions of its first Black musician,

Sanford Allen

Sanford Allen (born 1939) is an American classical violinist. At the age of 10, he began studying violin at the Juilliard School of Music and continued at the Mannes School of Music under Vera Fonaroff. He was the first African-American regular ...

, and its second woman musician,

Orin O'Brien