Law on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality. John Austin's utilitarian answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".Bix

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality. John Austin's utilitarian answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".Bix

John Austin

Later in the 20th century, H. L. A. Hart attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in '' The Concept of Law''. Hart argued law is a system of rules, divided into primary (rules of conduct) and secondary ones (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are further divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students continued the debate: In his book '' Law's Empire'', Ronald Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an " interpretive concept",Law's Empire, 410" /> that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions.

Later in the 20th century, H. L. A. Hart attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in '' The Concept of Law''. Hart argued law is a system of rules, divided into primary (rules of conduct) and secondary ones (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are further divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students continued the debate: In his book '' Law's Empire'', Ronald Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an " interpretive concept",Law's Empire, 410" /> that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions.

The history of law links closely to the development of

The history of law links closely to the development of  Ancient

Ancient

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems. Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined; the numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing by modern legal systems of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.Mattei, ''Comparative Law and Economics'', 71 The term "civil law", referring to the civilian legal system originating in continental Europe, should not be confused with "civil law" in the sense of the common law topics distinct from criminal law and

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems. Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined; the numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing by modern legal systems of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.Mattei, ''Comparative Law and Economics'', 71 The term "civil law", referring to the civilian legal system originating in continental Europe, should not be confused with "civil law" in the sense of the common law topics distinct from criminal law and

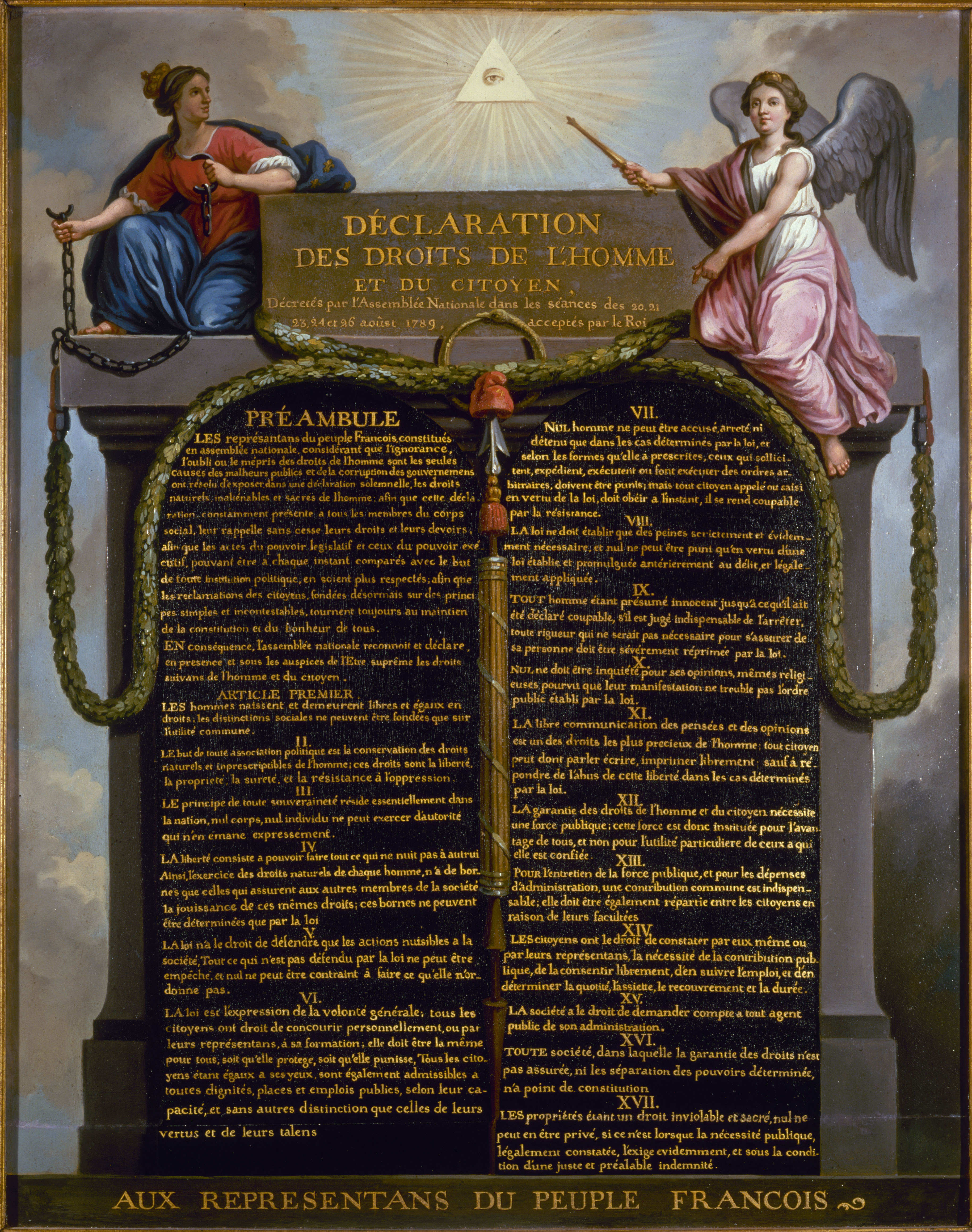

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislationŌĆöespecially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by governmentŌĆöand custom. Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislationŌĆöespecially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by governmentŌĆöand custom. Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the

In

In

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

and as the art of justice. State-enforced laws can be made by a group legislature

A legislature is an deliberative assembly, assembly with the authority to make laws for a Polity, political entity such as a Sovereign state, country or city. They are often contrasted with the Executive (government), executive and Judiciary, ...

or by a single legislator, resulting in statutes; by the executive through decree

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used f ...

s and regulation

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a ...

s; or established by judges through precedent, usually in common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

jurisdictions. Private individuals may create legally binding contract

A contract is a legally enforceable agreement between two or more parties that creates, defines, and governs mutual rights and obligations between them. A contract typically involves the transfer of goods, services, money, or a promise to ...

s, including arbitration agreements that adopt alternative ways of resolving disputes to standard court litigation. The creation of laws themselves may be influenced by a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

, written or tacit, and the rights

Rights are legal, social, or ethical principles of freedom or entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal system, social convention, or ethical th ...

encoded therein. The law shapes politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

, economics

Economics () is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interactions of economic agents and how economies work. Microeconomics analy ...

, history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

and society

A society is a Social group, group of individuals involved in persistent Social relation, social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same Politics, political authority an ...

in various ways and serves as a mediator of relations between people.

Legal systems vary between jurisdictions, with their differences analysed in comparative law. In civil law

Civil law may refer to:

* Civil law (common law), the part of law that concerns private citizens and legal persons

* Civil law (legal system), or continental law, a legal system originating in continental Europe and based on Roman law

** Private la ...

jurisdictions, a legislature or other central body codifies and consolidates the law. In common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

systems, judges may make binding case law through precedent, although on occasion this may be overturned by a higher court or the legislature. Historically, religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas other ...

has influenced secular matters and is, as of the 21st century, still in use in some religious communities. Sharia law

Sharia (; ar, ž┤ž▒┘Ŗž╣ž®, shar─½╩┐a ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the ...

based on Islamic principles is used as the primary legal system in several countries, including Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

and Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

.

The scope of law can be divided into two domains. Public law

Public law is the part of law that governs relations between legal persons and a government, between different institutions within a State (polity), state, between Separation of powers, different branches of governments, as well as relationship ...

concerns government and society, including constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in fed ...

, administrative law

Administrative law is the division of law that governs the activities of executive branch agencies of government. Administrative law concerns executive branch rule making (executive branch rules are generally referred to as " regulations"), ...

, and criminal law. Private law deals with legal disputes between individuals and/or organisations in areas such as contracts, property

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, r ...

, torts/ delicts and commercial law. This distinction is stronger in civil law

Civil law may refer to:

* Civil law (common law), the part of law that concerns private citizens and legal persons

* Civil law (legal system), or continental law, a legal system originating in continental Europe and based on Roman law

** Private la ...

countries, particularly those with a separate system of administrative courts; by contrast, the public-private law divide is less pronounced in common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

jurisdictions.

Law provides a source of scholarly inquiry into legal history

Legal history or the history of law is the study of how law has Sociocultural evolution, evolved and why it has changed. Legal history is closely connected to the development of civilisations and operates in the wider context of social history. C ...

, philosophy, economic analysis and sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation and ...

. Law also raises important and complex issues concerning equality, fairness, and justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

.

Philosophy of law

The philosophy of law is commonly known as jurisprudence. Normative jurisprudence asks "what should law be?", while analytic jurisprudence asks "what is law?"Analytical jurisprudence

There have been several attempts to produce "a universally acceptable definition of law". In 1972, Baron Hampstead suggested that no such definition could be produced. Dennis Lloyd, Baron Lloyd of Hampstead. ''Introduction to Jurisprudence''. Third Edition. Stevens & Sons. London. 1972. Second Impression. 1975. p. 39. McCoubrey and White said that the question "what is law?" has no simple answer. Glanville Williams said that the meaning of the word "law" depends on the context in which that word is used. He said that, for example, "early customary law

A legal custom is the established pattern of behavior that can be objectively verified within a particular social setting. A claim can be carried out in defense of "what has always been done and accepted by law".

Customary law (also, consuetudina ...

" and " municipal law" were contexts where the word "law" had two different and irreconcilable meanings. Thurman Arnold said that it is obvious that it is impossible to define the word "law" and that it is also equally obvious that the struggle to define that word should not ever be abandoned. It is possible to take the view that there is no need to define the word "law" (e.g. "let's forget about generalities and get down to cases").

One definition is that law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behaviour. In '' The Concept of Law,'' H.L.A Hart argued that law is a "system of rules"; John Austin said law was "the command of a sovereign, backed by the threat of a sanction"; Ronald Dworkin describes law as an "interpretive concept" to achieve justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

in his text titled '' Law's Empire'';Law's Empire, 410">Dworkin, '' Law's Empire'', 410 and Joseph Raz

Joseph Raz (; he, ūÖūĢūĪūŻ ū©ū¢; born Zaltsman; 21 March 19392 May 2022) was an Israeli legal, moral and political philosopher. He was an advocate of legal positivism and is known for his conception of perfectionist liberalism. Raz spent m ...

argues law is an "authority" to mediate people's interests. Oliver Wendell Holmes said, "The prophecies of what the courts will do in fact, and nothing more pretentious, are what I mean by the law." In his ''Treatise on Law

''Treatise on Law'' is Thomas Aquinas' major work of legal philosophy. It forms questions 90ŌĆō108 of the ''Prima Secund├”'' ("First artof the Second art) of the ''Summa Theologi├”'', Aquinas' masterwork of Scholastic philosophical theology. ...

,'' Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 ŌĆō 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

argues that law is a rational ordering of things which concern the common good that is promulgated by whoever is charged with the care of the community. This definition has both positivist and naturalist elements.

Connection to morality and justice

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality. John Austin's utilitarian answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".Bix

Definitions of law often raise the question of the extent to which law incorporates morality. John Austin's utilitarian answer was that law is "commands, backed by threat of sanctions, from a sovereign, to whom people have a habit of obedience".BixJohn Austin

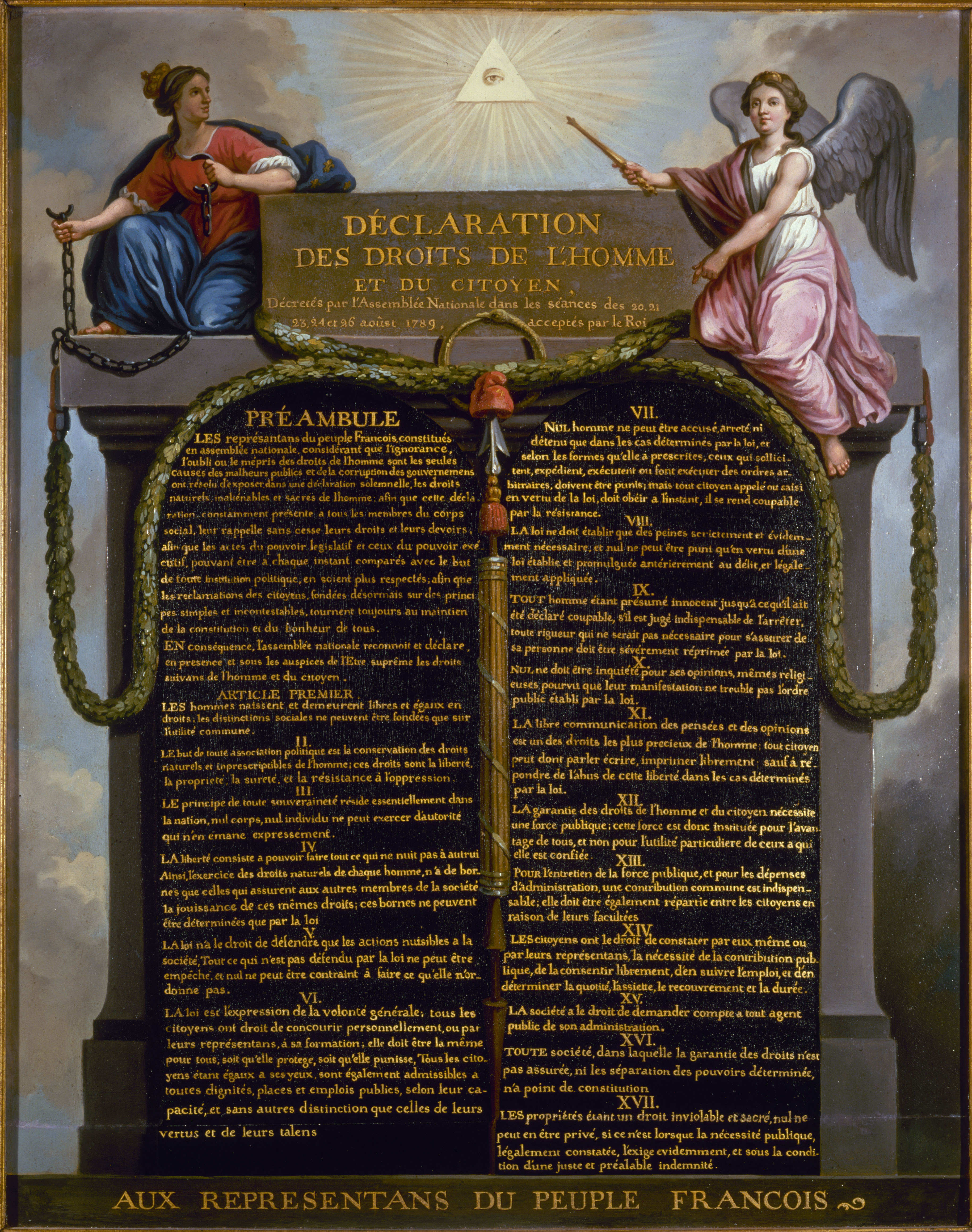

Natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacted ...

yers on the other side, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 ŌĆō 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revol ...

, argue that law reflects essentially moral and unchangeable laws of nature. The concept of "natural law" emerged in ancient Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empi ...

concurrently and in connection with the notion of justice, and re-entered the mainstream of Western culture

image:Da Vinci Vitruve Luc Viatour.jpg, Leonardo da Vinci's ''Vitruvian Man''. Based on the correlations of ideal Body proportions, human proportions with geometry described by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius in Book III of his treatise '' ...

through the writings of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 ŌĆō 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, notably his ''Treatise on Law

''Treatise on Law'' is Thomas Aquinas' major work of legal philosophy. It forms questions 90ŌĆō108 of the ''Prima Secund├”'' ("First artof the Second art) of the ''Summa Theologi├”'', Aquinas' masterwork of Scholastic philosophical theology. ...

''.

When having completed the first two parts of his book '' Splendeurs et mis├©res des courtisanes'', which he intended to be the end of the entire work, Honor├® de Balzac

Honor├® de Balzac ( , more commonly , ; born Honor├® Balzac;Jean-Louis Dega, La vie prodigieuse de Bernard-Fran├¦ois Balssa, p├©re d'Honor├® de Balzac : Aux sources historiques de La Com├®die humaine, Rodez, Subervie, 1998, 665 p. 20 May 179 ...

visited the Conciergerie. Thereafter, he decided to add a third part, finally named ''O├╣ m├©nent les mauvais chemins'' (''The Ends of Evil Ways''), entirely dedicated to describing the conditions in prison.. In this third part, he states:

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius (; 10 April 1583 ŌĆō 28 August 1645), also known as Huig de Groot () and Hugo de Groot (), was a Dutch humanist, diplomat, lawyer, theologian, jurist, poet and playwright.

A teenage intellectual prodigy, he was born in Delf ...

, the founder of a purely rationalistic system of natural law, argued that law arises from both a social impulseŌĆöas Aristotle had indicatedŌĆöand reason. Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 ŌĆō 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in K├Čnigsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aes ...

believed a moral imperative requires laws "be chosen as though they should hold as universal laws of nature". Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747ref name="Johnson2012" /> ŌĆō 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, an ...

and his student Austin, following David Hume, believed that this conflated the "is" and what "ought to be" problem. Bentham and Austin argued for law's positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positiveŌĆömeaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. ...

; that real law is entirely separate from "morality". Kant was also criticised by Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 ŌĆō 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his c ...

, who rejected the principle of equality, and believed that law emanates from the will to power, and cannot be labeled as "moral" or "immoral".

In 1934, the Austrian philosopher Hans Kelsen continued the positivist tradition in his book the '' Pure Theory of Law''. Kelsen believed that although law is separate from morality, it is endowed with "normativity", meaning we ought to obey it. While laws are positive "is" statements (e.g. the fine for reversing on a highway ''is'' Ōé¼500); law tells us what we "should" do. Thus, each legal system can be hypothesised to have a basic norm ('' Grundnorm'') instructing us to obey. Kelsen's major opponent, Carl Schmitt, rejected both positivism and the idea of the rule of law because he did not accept the primacy of abstract normative principles over concrete political positions and decisions. Therefore, Schmitt advocated a jurisprudence of the exception (state of emergency

A state of emergency is a situation in which a government is empowered to be able to put through policies that it would normally not be permitted to do, for the safety and protection of its citizens. A government can declare such a state du ...

), which denied that legal norms could encompass all of the political experience.Finn, ''Constitutions in Crisis'', 170ŌĆō171

Later in the 20th century, H. L. A. Hart attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in '' The Concept of Law''. Hart argued law is a system of rules, divided into primary (rules of conduct) and secondary ones (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are further divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students continued the debate: In his book '' Law's Empire'', Ronald Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an " interpretive concept",Law's Empire, 410" /> that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions.

Later in the 20th century, H. L. A. Hart attacked Austin for his simplifications and Kelsen for his fictions in '' The Concept of Law''. Hart argued law is a system of rules, divided into primary (rules of conduct) and secondary ones (rules addressed to officials to administer primary rules). Secondary rules are further divided into rules of adjudication (to resolve legal disputes), rules of change (allowing laws to be varied) and the rule of recognition (allowing laws to be identified as valid). Two of Hart's students continued the debate: In his book '' Law's Empire'', Ronald Dworkin attacked Hart and the positivists for their refusal to treat law as a moral issue. Dworkin argues that law is an " interpretive concept",Law's Empire, 410" /> that requires judges to find the best fitting and most just solution to a legal dispute, given their constitutional traditions. Joseph Raz

Joseph Raz (; he, ūÖūĢūĪūŻ ū©ū¢; born Zaltsman; 21 March 19392 May 2022) was an Israeli legal, moral and political philosopher. He was an advocate of legal positivism and is known for his conception of perfectionist liberalism. Raz spent m ...

, on the other hand, defended the positivist outlook and criticised Hart's "soft social thesis" approach in ''The Authority of Law''.Raz, ''The Authority of Law'', 3ŌĆō36 Raz argues that law is authority, identifiable purely through social sources and without reference to moral reasoning. In his view, any categorisation of rules beyond their role as authoritative instruments in mediation are best left to sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation and ...

, rather than jurisprudence.

History

The history of law links closely to the development of

The history of law links closely to the development of civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

C ...

. Ancient Egyptian law, dating as far back as 3000 BC, was based on the concept of Ma'at and characterised by tradition, rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate par ...

al speech, social equality and impartiality. By the 22nd century BC, the ancient Sumerian ruler Ur-Nammu had formulated the first law code, which consisted of casuistic statements ("if ŌĆ” then ..."). Around 1760 BC, King Hammurabi further developed Babylonian law, by codifying and inscribing it in stone. Hammurabi placed several copies of his law code throughout the kingdom of Babylon as stelae, for the entire public to see; this became known as the Codex Hammurabi. The most intact copy of these stelae was discovered in the 19th century by British Assyriologists, and has since been fully transliterated and translated into various languages, including English, Italian, German, and French.

The Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

dates back to 1280 BC and takes the form of moral imperatives as recommendations for a good society. The small Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

city-state, ancient Athens

Athens ( ; el, ╬æ╬Ė╬«╬Į╬▒, Ath├Łna ; grc, ß╝ł╬Ėß┐å╬Į╬▒╬╣, Ath├¬nai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

, from about the 8th century BC was the first society to be based on broad inclusion of its citizenry, excluding women and enslaved people. However, Athens had no legal science or single word for "law", relying instead on the three-way distinction between divine law (''th├®mis''), human decree (''nomos'') and custom (''d├Łk─ō''). Yet Ancient Greek law contained major constitutional innovations in the development of democracy

Democracy (From grc, ╬┤╬Ę╬╝╬┐╬║Žü╬▒Žä╬»╬▒, d─ōmokrat├Ła, ''d─ōmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which people, the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation ("direct democracy"), or to choo ...

.

Roman law

Roman law is the legal system of ancient Rome, including the legal developments spanning over a thousand years of jurisprudence, from the Twelve Tables (c. 449 BC), to the '' Corpus Juris Civilis'' (AD 529) ordered by Eastern Roman emperor Jus ...

was heavily influenced by Greek philosophy, but its detailed rules were developed by professional jurists and were highly sophisticated. Over the centuries between the rise and decline of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, ╬Æ╬▒Žā╬╣╬╗╬Ą╬»╬▒ Žäß┐Č╬Į ß┐¼Žē╬╝╬▒╬»Žē╬Į, Basile├Ła t├┤n Rh┼Źma├Ł┼Źn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, law was adapted to cope with the changing social situations and underwent major codification under Theodosius II and Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, ß╝Ė╬┐ŽģŽāŽä╬╣╬Į╬╣╬▒╬ĮŽīŽé ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

.As a legal system, Roman law has affected the development of law worldwide. It also forms the basis for the law codes of most countries of continental Europe and has played an important role in the creation of the idea of a common European culture (Stein, ''Roman Law in European History'', 2, 104ŌĆō107). Although codes were replaced by custom and case law during the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the M ...

, Roman law was rediscovered around the 11th century when medieval legal scholars began to research Roman codes and adapt their concepts to the canon law, giving birth to the '' jus commune''. Latin legal maxims (called brocards) were compiled for guidance. In medieval England, royal courts developed a body of precedent which later became the common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

. A Europe-wide Law Merchant was formed so that merchants could trade with common standards of practice rather than with the many splintered facets of local laws. The Law Merchant, a precursor to modern commercial law, emphasised the freedom to contract and alienability of property. As nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Law Merchant was incorporated into countries' local law under new civil codes. The Napoleonic and German Codes became the most influential. In contrast to English common law, which consists of enormous tomes of case law, codes in small books are easy to export and easy for judges to apply. However, today there are signs that civil and common law are converging. EU law is codified in treaties, but develops through ''de facto'' precedent laid down by the European Court of Justice.

Ancient

Ancient India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

and China represent distinct traditions of law, and have historically had independent schools of legal theory and practice. The '' Arthashastra'', probably compiled around 100 AD (although it contains older material), and the '' Manusmriti'' (c. 100ŌĆō300 AD) were foundational treatises in India, and comprise texts considered authoritative legal guidance. Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and pluralism

Pluralism denotes a diversity of views or stands rather than a single approach or method.

Pluralism or pluralist may refer to:

Politics and law

* Pluralism (political philosophy), the acknowledgement of a diversity of political systems

* Plur ...

, and was cited across Southeast Asia. During the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent, sharia was established by the Muslim sultanates and empires, most notably Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the ...

's Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, compiled by emperor Aurangzeb and various scholars of Islam. In India, the Hindu legal tradition, along with Islamic law, were both supplanted by common law when India became part of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

. Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

and Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta i ...

also adopted the common law system. The eastern Asia legal tradition reflects a unique blend of secular and religious influences. Japan was the first country to begin modernising its legal system along western lines, by importing parts of the French

French (french: fran├¦ais(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, but mostly the German Civil Code. This partly reflected Germany's status as a rising power in the late 19th century. Similarly, traditional Chinese law gave way to westernisation towards the final years of the Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in the form of six private law codes based mainly on the Japanese model of German law. Today Taiwanese law retains the closest affinity to the codifications from that period, because of the split between Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists, who fled there, and Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 ŌĆō 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

's communists who won control of the mainland in 1949. The current legal infrastructure in the People's Republic of China was heavily influenced by Soviet Socialist law, which essentially inflates administrative law at the expense of private law rights. Due to rapid industrialisation, today China is undergoing a process of reform, at least in terms of economic, if not social and political, rights. A new contract code in 1999 represented a move away from administrative domination. Furthermore, after negotiations lasting fifteen years, in 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is an intergovernmental organization that regulates and facilitates international trade. With effective cooperation

in the United Nations System, governments use the organization to establish, revise, and ...

.

Legal systems

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems. Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined; the numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing by modern legal systems of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.Mattei, ''Comparative Law and Economics'', 71 The term "civil law", referring to the civilian legal system originating in continental Europe, should not be confused with "civil law" in the sense of the common law topics distinct from criminal law and

In general, legal systems can be split between civil law and common law systems. Modern scholars argue that the significance of this distinction has progressively declined; the numerous legal transplants, typical of modern law, result in the sharing by modern legal systems of many features traditionally considered typical of either common law or civil law.Mattei, ''Comparative Law and Economics'', 71 The term "civil law", referring to the civilian legal system originating in continental Europe, should not be confused with "civil law" in the sense of the common law topics distinct from criminal law and public law

Public law is the part of law that governs relations between legal persons and a government, between different institutions within a State (polity), state, between Separation of powers, different branches of governments, as well as relationship ...

.

The third type of legal systemŌĆöaccepted by some countries without separation of church and stateŌĆöis religious law, based on scriptures. The specific system that a country is ruled by is often determined by its history, connections with other countries, or its adherence to international standards. The sources that jurisdictions adopt as authoritatively binding are the defining features of any legal system. Yet classification is a matter of form rather than substance since similar rules often prevail.

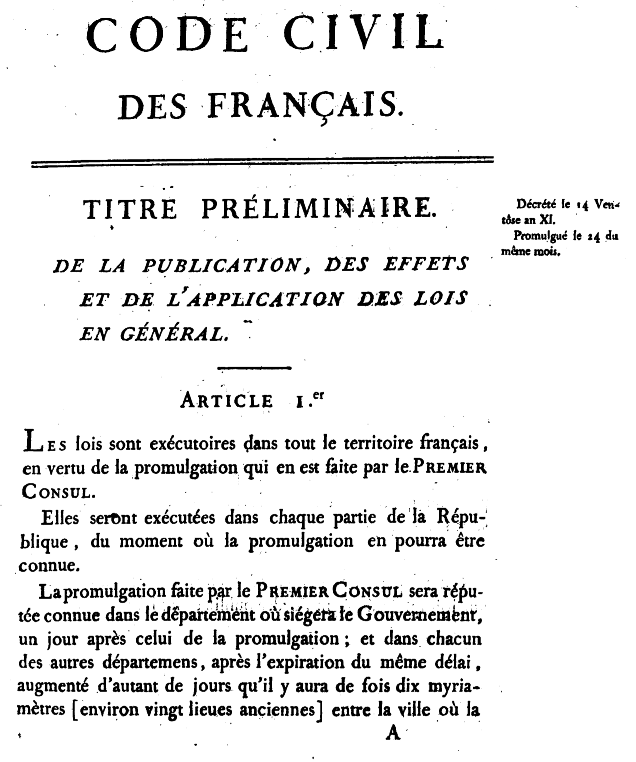

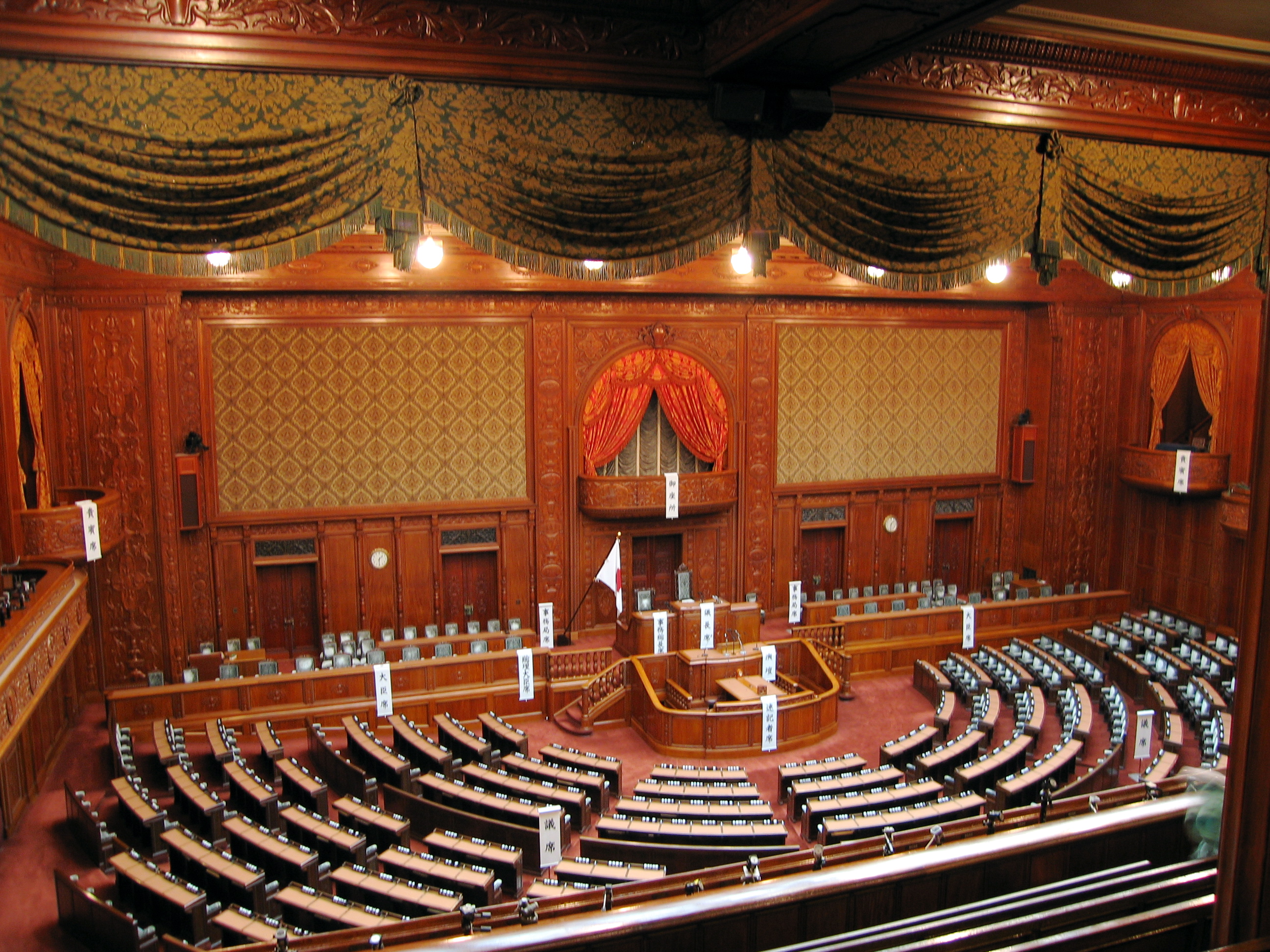

Civil law

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislationŌĆöespecially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by governmentŌĆöand custom. Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the

Civil law is the legal system used in most countries around the world today. In civil law the sources recognised as authoritative are, primarily, legislationŌĆöespecially codifications in constitutions or statutes passed by governmentŌĆöand custom. Codifications date back millennia, with one early example being the Babylonian Babylonian may refer to:

* Babylon, a Semitic Akkadian city/state of ancient Mesopotamia founded in 1894 BC

* Babylonia, an ancient Akkadian-speaking Semitic nation-state and cultural region based in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq)

...

'' Codex Hammurabi''. Modern civil law systems essentially derive from legal codes issued by Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, ß╝Ė╬┐ŽģŽāŽä╬╣╬Į╬╣╬▒╬ĮŽīŽé ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

in the 6th century, which were rediscovered by 11th century Italy. Roman law in the days of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

and Empire was heavily procedural, and lacked a professional legal class. Instead a lay magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a ''magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

, ''iudex'', was chosen to adjudicate. Decisions were not published in any systematic way, so any case law that developed was disguised and almost unrecognised. Each case was to be decided afresh from the laws of the State, which mirrors the (theoretical) unimportance of judges' decisions for future cases in civil law systems today. From 529 to 534 AD the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, ß╝Ė╬┐ŽģŽāŽä╬╣╬Į╬╣╬▒╬ĮŽīŽé ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

codified and consolidated Roman law up until that point, so that what remained was one-twentieth of the mass of legal texts from before. This became known as the '' Corpus Juris Civilis''. As one legal historian wrote, "Justinian consciously looked back to the golden age of Roman law and aimed to restore it to the peak it had reached three centuries before." The Justinian Code remained in force in the East until the fall of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

. Western Europe, meanwhile, relied on a mix of the Theodosian Code and Germanic customary law until the Justinian Code was rediscovered in the 11th century, and scholars at the University of Bologna used it to interpret their own laws. Civil law codifications based closely on Roman law, alongside some influences from religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Different religious systems hold sacred law in a greater or lesser degree of importance to their belief systems, with some being explicitly antinomian whereas other ...

s such as canon law, continued to spread throughout Europe until the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

; then, in the 19th century, both France, with the '' Code Civil'', and Germany, with the ''B├╝rgerliches Gesetzbuch

The ''B├╝rgerliches Gesetzbuch'' (, ), abbreviated BGB, is the civil code of Germany. In development since 1881, it became effective on 1 January 1900, and was considered a massive and groundbreaking project.

The BGB served as a template in se ...

'', modernised their legal codes. Both these codes influenced heavily not only the law systems of the countries in continental Europe (e.g. Greece), but also the Japanese and Korean legal traditions. Today, countries that have civil law systems range from Russia and Turkey to most of Central and Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Am├®rique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, Am├®rica Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages ŌĆö languages derived ...

.

Anarchist law

Anarchism has been practiced in society in much of the world. Mass anarchist communities, ranging from Syria to the United States, exist and vary from hundreds to millions. Anarchism encompasses a broad range ofsocial

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

political philosophies with different tendencies and implementation.

Anarchist law primarily deals with how anarchism is implemented upon a society, the framework based on decentralized organizations and mutual aid, with representation through a form of direct democracy. Laws being based upon their need. A large portion of anarchist ideologies such as anarcho-syndicalism and anarcho-communism primarily focuses on decentralized worker unions, cooperatives and syndicates as the main instrument of society.

Socialist law

Socialist law is the legal systems incommunist state

A communist state, also known as a MarxistŌĆōLeninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by MarxismŌĆōLeninism. MarxismŌĆōLeninism was the Ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet U ...

s such as the former Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, sli ...

. Academic opinion is divided on whether it is a separate system from civil law, given major deviations based on MarxistŌĆōLeninist ideology, such as subordinating the judiciary to the executive ruling party.

Common law and equity

In

In common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

legal systems, decisions by courts are explicitly acknowledged as "law" on equal footing with statutes adopted through the legislative process and with regulations issued by the executive branch

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems b ...

. The "doctrine of precedent", or '' stare decisis'' (Latin for "to stand by decisions") means that decisions by higher courts bind lower courts, and future decisions of the same court, to assure that similar cases reach similar results. In contrast, in "civil law

Civil law may refer to:

* Civil law (common law), the part of law that concerns private citizens and legal persons

* Civil law (legal system), or continental law, a legal system originating in continental Europe and based on Roman law

** Private la ...

" systems, legislative statutes are typically more detailed, and judicial decisions are shorter and less detailed, because the judge or barrister is only writing to decide the single case, rather than to set out reasoning that will guide future courts.

Common law originated from England and has been inherited by almost every country once tied to the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

(except Malta, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to th ...

, the U.S. state of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a U.S. state, state in the Deep South and South Central United States, South Central regions of the United States. It is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 20th-smal ...

, and the Canadian province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Government of Canada, Canadian government, ''Qu├®bec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is ...

). In medieval England, the Norman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

the law varied shire-to-shire, based on disparate tribal customs. The concept of a "common law" developed during the reign of Henry II during the late 12th century, when Henry appointed judges that had authority to create an institutionalised and unified system of law "common" to the country. The next major step in the evolution of the common law came when King John King John may refer to:

Rulers

* John, King of England (1166ŌĆō1216)

* John I of Jerusalem (c. 1170ŌĆō1237)

* John Balliol, King of Scotland (c. 1249ŌĆō1314)

* John I of France (15ŌĆō20 November 1316)

* John II of France (1319ŌĆō1364)

* John I o ...

was forced by his barons to sign a document limiting his authority to pass laws. This "great charter" or ''Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, Berkshire, Windsor, on 15 June 1215. ...

'' of 1215 also required that the King's entourage of judges hold their courts and judgments at "a certain place" rather than dispensing autocratic justice in unpredictable places about the country. A concentrated and elite group of judges acquired a dominant role in law-making under this system, and compared to its European counterparts the English judiciary became highly centralised. In 1297, for instance, while the highest court in France had fifty-one judges, the English Court of Common Pleas had five. This powerful and tight-knit judiciary gave rise to a systematised process of developing common law.

However, the system became overly systematisedŌĆöoverly rigid and inflexible. As a result, as time went on, increasing numbers of citizens petitioned the King to override the common law, and on the King's behalf the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. T ...

gave judgment to do what was equitable in a case. From the time of Sir Thomas More, the first lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solici ...

to be appointed as Lord Chancellor, a systematic body of equity grew up alongside the rigid common law, and developed its own Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid a slow pace of change and possible harshness (or "inequity") of the Common law#History, common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over ...

. At first, equity was often criticised as erratic, that it varied according to the length of the Chancellor's foot. Over time, courts of equity developed solid principles, especially under Lord Eldon. In the 19th century in England, and in 1937 in the U.S., the two systems were merged.

In developing the common law, academic writings have always played an important part, both to collect overarching principles from dispersed case law, and to argue for change. William Blackstone

Sir William Blackstone (10 July 1723 ŌĆō 14 February 1780) was an English jurist, judge and Tory (British political party), Tory politician of the eighteenth century. He is most noted for writing the ''Commentaries on the Laws of England''. Bo ...

, from around 1760, was the first scholar to collect, describe, and teach the common law. But merely in describing, scholars who sought explanations and underlying structures slowly changed the way the law actually worked.

Religious law

Religious law is explicitly based on religious precepts. Examples include the JewishHalakha

''Halakha'' (; he, ūöų▓ū£ųĖūøųĖūö, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical comm ...

and Islamic ShariaŌĆöboth of which translate as the "path to follow"ŌĆöwhile Christian canon law also survives in some church communities. Often the implication of religion for law is unalterability, because the word of God cannot be amended or legislated against by judges or governments. However, a thorough and detailed legal system generally requires human elaboration. For instance, the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

has some law, and it acts as a source of further law through interpretation, ''Qiyas

In Islamic jurisprudence, qiyas ( ar, ┘é┘Ŗž¦ž│ , " analogy") is the process of deductive analogy in which the teachings of the hadith are compared and contrasted with those of the Quran, in order to apply a known injunction ('' nass'') to a ...

'' (reasoning by analogy), ''Ijma

''Ijm─ü╩┐'' ( ar, žźž¼┘ģž¦ž╣ , " consensus") is an Arabic term referring to the consensus or agreement of the Islamic community on a point of Islamic law. Sunni Muslims regard ''ijm─ü as one of the secondary sources of Sharia law, after the Qur ...

'' (consensus) and precedent. This is mainly contained in a body of law and jurisprudence known as Sharia and Fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, ┘ü┘é┘ć ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ...

respectively. Another example is the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''T┼Źr─ü'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

or Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, in the Pentateuch

The Torah (; hbo, ''T┼Źr─ü'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the ...

or Five Books of Moses. This contains the basic code of Jewish law, which some Israeli communities choose to use. The Halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, ūöų▓ū£ųĖūøųĖūö, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical comm ...

is a code of Jewish law that summarizes some of the Talmud's interpretations. Nevertheless, Israeli law allows litigants to use religious laws only if they choose. Canon law is only in use by members of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

and the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and oth ...

.

Canon law

Canon law (fromGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''kanon'', a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority Ecclesiastical government, ecclesiastical hierarchy, or ecclesiocracy may refer to:

* Theocracy, a form of religious State government

* Hierocracy (medieval)

In the Middle Ages, hierocracy or papalism''Hierocracy'' is sometimes construed as a mor ...

(Church leadership), for the government of a Christian organisation or church and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical

{{Short pages monitor

Some countries allow their highest judicial authority to overrule legislation they determine to be

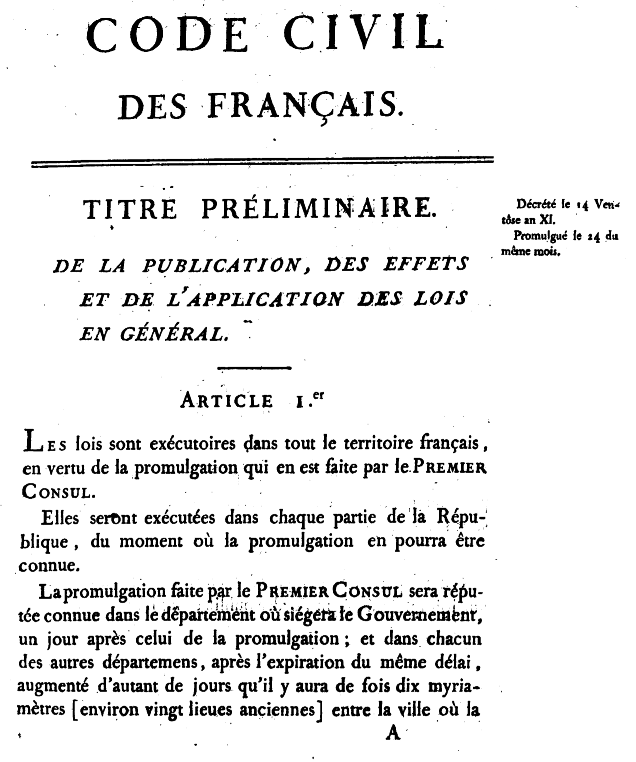

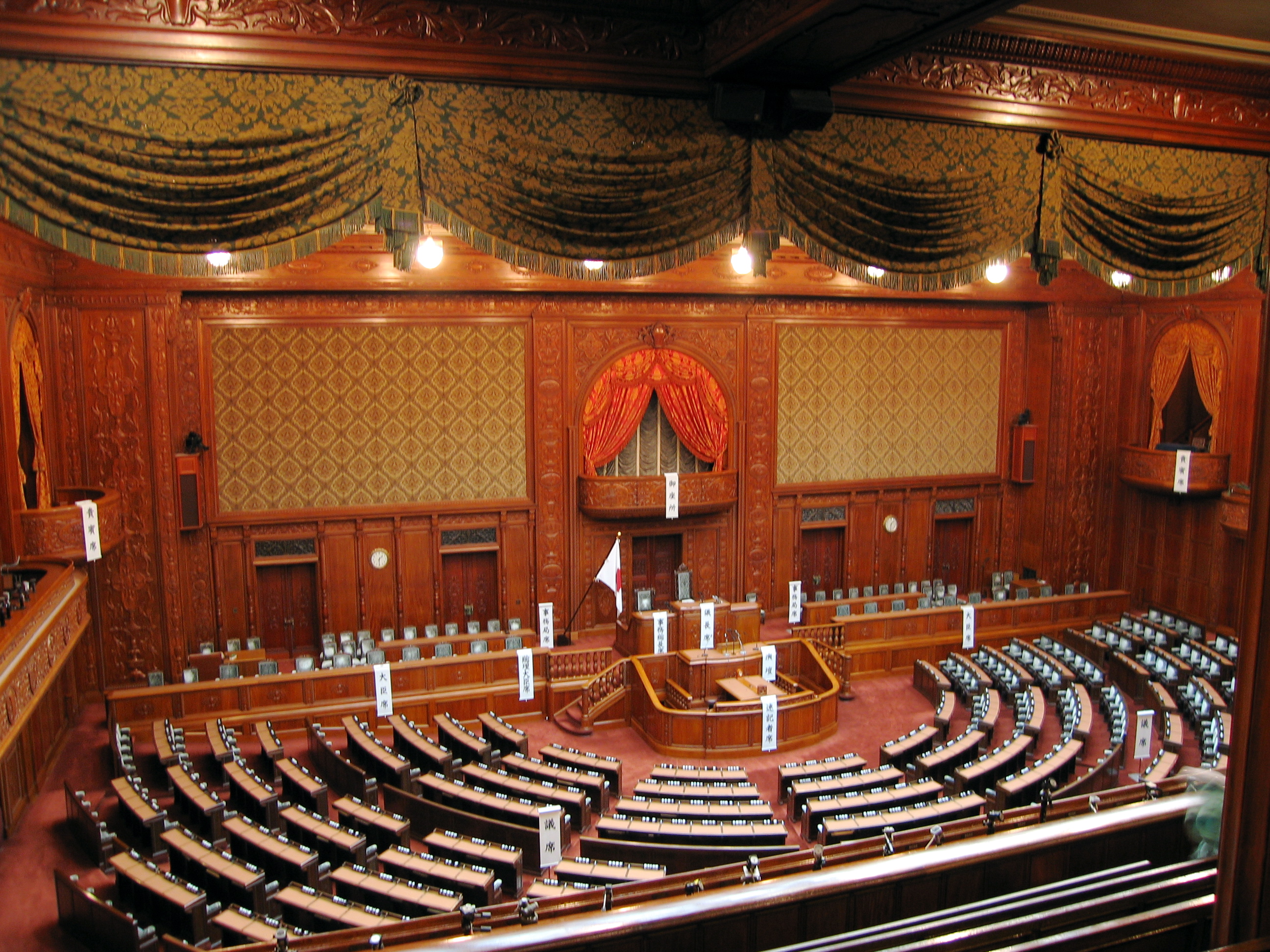

Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the Congress in Washington, D.C., the

Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the Congress in Washington, D.C., the

The executive in a legal system serves as the centre of political authority of the

The executive in a legal system serves as the centre of political authority of the

While military organisations have existed as long as government itself, the idea of a standing police force is a relatively modern concept. For example, Medieval England's system of travelling criminal courts, or assizes, used show trials and public executions to instill communities with fear to maintain control. The first modern police were probably those in 17th-century Paris, in the court of

While military organisations have existed as long as government itself, the idea of a standing police force is a relatively modern concept. For example, Medieval England's system of travelling criminal courts, or assizes, used show trials and public executions to instill communities with fear to maintain control. The first modern police were probably those in 17th-century Paris, in the court of

The etymology of ''bureaucracy'' derives from the French word for ''office'' (''bureau'') and the

The etymology of ''bureaucracy'' derives from the French word for ''office'' (''bureau'') and the

A corollary of the rule of law is the existence of a legal profession sufficiently autonomous to invoke the authority of the independent judiciary; the right to assistance of a barrister in a court proceeding emanates from this corollaryŌĆöin England the function of barrister or advocate is distinguished from legal counselor. As the European Court of Human Rights has stated, the law should be adequately accessible to everyone and people should be able to foresee how the law affects them.

In order to maintain professionalism, the

A corollary of the rule of law is the existence of a legal profession sufficiently autonomous to invoke the authority of the independent judiciary; the right to assistance of a barrister in a court proceeding emanates from this corollaryŌĆöin England the function of barrister or advocate is distinguished from legal counselor. As the European Court of Human Rights has stated, the law should be adequately accessible to everyone and people should be able to foresee how the law affects them.

In order to maintain professionalism, the

The Classical republican concept of "civil society" dates back to Hobbes and Locke. Locke saw civil society as people who have "a common established law and judicature to appeal to, with authority to decide controversies between them." German philosopher

The Classical republican concept of "civil society" dates back to Hobbes and Locke. Locke saw civil society as people who have "a common established law and judicature to appeal to, with authority to decide controversies between them." German philosopher

Constitutional and administrative law govern the affairs of the state. Constitutional law concerns both the relationships between the executive, legislature and judiciary and the human rights or civil liberties of individuals against the state. Most jurisdictions, like the

Constitutional and administrative law govern the affairs of the state. Constitutional law concerns both the relationships between the executive, legislature and judiciary and the human rights or civil liberties of individuals against the state. Most jurisdictions, like the

Examples of crimes include murder, assault, fraud and theft. In exceptional circumstances defences can apply to specific acts, such as killing in self defence, or pleading insanity. Another example is in the 19th-century English case of '' R v Dudley and Stephens'', which tested a defence of " necessity". The ''Mignonette'', sailing from

Examples of crimes include murder, assault, fraud and theft. In exceptional circumstances defences can apply to specific acts, such as killing in self defence, or pleading insanity. Another example is in the 19th-century English case of '' R v Dudley and Stephens'', which tested a defence of " necessity". The ''Mignonette'', sailing from

Contract law concerns enforceable promises, and can be summed up in the Latin phrase '' pacta sunt servanda'' (agreements must be kept). In common law jurisdictions, three key elements to the creation of a contract are necessary: offer and acceptance, consideration and the intention to create legal relations. In '' Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company'' a medical firm advertised that its new wonder drug, the smokeball, would cure people's flu, and if it did not, the buyers would get ┬Ż100. Many people sued for their ┬Ż100 when the drug did not work. Fearing bankruptcy, Carbolic argued the advert was not to be taken as a serious, legally binding offer. It was an invitation to treat, mere puffery, a gimmick. But the Court of Appeal held that to a reasonable man Carbolic had made a serious offer, accentuated by their reassuring statement, "┬Ż1000 is deposited". Equally, people had given good consideration for the offer by going to the "distinct inconvenience" of using a faulty product. "Read the advertisement how you will, and twist it about as you will", said Lord Justice Lindley, "here is a distinct promise expressed in language which is perfectly unmistakable".About

Contract law concerns enforceable promises, and can be summed up in the Latin phrase '' pacta sunt servanda'' (agreements must be kept). In common law jurisdictions, three key elements to the creation of a contract are necessary: offer and acceptance, consideration and the intention to create legal relations. In '' Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company'' a medical firm advertised that its new wonder drug, the smokeball, would cure people's flu, and if it did not, the buyers would get ┬Ż100. Many people sued for their ┬Ż100 when the drug did not work. Fearing bankruptcy, Carbolic argued the advert was not to be taken as a serious, legally binding offer. It was an invitation to treat, mere puffery, a gimmick. But the Court of Appeal held that to a reasonable man Carbolic had made a serious offer, accentuated by their reassuring statement, "┬Ż1000 is deposited". Equally, people had given good consideration for the offer by going to the "distinct inconvenience" of using a faulty product. "Read the advertisement how you will, and twist it about as you will", said Lord Justice Lindley, "here is a distinct promise expressed in language which is perfectly unmistakable".About

Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company

'' 8931 QB 256, and the element of consideration, see Beale and Tallon, ''Contract Law'', 142ŌĆō143 Consideration indicates the fact that all parties to a contract have exchanged something of value. Some common law systems, including Australia, are moving away from the idea of consideration as a requirement. The idea of estoppel or ''culpa in contrahendo'', can be used to create obligations during pre-contractual negotiations. Civil law jurisdictions treat contracts differently in a number of respects, with a more interventionist role for the state in both the formation and enforcement of contracts. Compared to common law jurisdictions, civil law systems incorporate more mandatory terms into contracts, allow greater latitude for courts to interpret and revise contract terms and impose a stronger duty of good faith, but are also more likely to enforce penalty clauses and specific performance of contracts. They also do not require consideration for a contract to be binding. In France, an ordinary contract is said to form simply on the basis of a "meeting of the minds" or a "concurrence of wills".

Certain civil wrongs are grouped together as torts under common law systems and delicts under civil law systems. To have acted tortiously, one must have breached a duty to another person, or infringed some pre-existing legal right. A simple example might be unintentionally hitting someone with a cricket ball. Under the law of

Certain civil wrongs are grouped together as torts under common law systems and delicts under civil law systems. To have acted tortiously, one must have breached a duty to another person, or infringed some pre-existing legal right. A simple example might be unintentionally hitting someone with a cricket ball. Under the law of

UK Law Online

. A friend of Donoghue ordered an opaque bottle of ginger beer (intended for the consumption of Donoghue) in a caf├® in Paisley, Renfrewshire, Paisley. Having consumed half of it, Donoghue poured the remainder into a tumbler. The decomposing remains of a snail floated out. She claimed to have suffered from shock, fell ill with gastroenteritis and sued the manufacturer for carelessly allowing the drink to be contaminated. The

Equity is a body of rules that developed in England separately from the "common law". The common law was administered by judges and barristers. The

Equity is a body of rules that developed in England separately from the "common law". The common law was administered by judges and barristers. The

* Labour law is the study of a tripartite industrial relationship between worker, employer and trade union. This involves

* Labour law is the study of a tripartite industrial relationship between worker, employer and trade union. This involves  * Tax law involves regulations that concern value added tax, corporate tax, and

* Tax law involves regulations that concern value added tax, corporate tax, and

The most prominent economic analyst of law is 1991

The most prominent economic analyst of law is 1991

Around 1900

Around 1900

Perseus program

. * Barzilai, Gad (2003), ''Communities and Law: Politics and Cultures of Legal Identities''. The University of Michigan Press, 2003. Second print 2005 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Hamilton, Michael S., and George W. Spiro (2008). ''The Dynamics of Law'', 4th ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. . * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Silvestri, Paolo, "The ideal of good government in Luigi EinaudiŌĆÖs Thought and Life: Between Law and Freedom"

, in Paolo Heritier, Paolo Silvestri (Eds.), Good government, Governance, Human complexity. Luigi Einaudi's legacy and contemporary societies, Leo Olschki, Firenze, 2012, pp. 55ŌĆō95. ; Online sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

DRAGNET: Search of free legal databases from New York Law School

WorldLII ŌĆō World Legal Information Institute

CommonLII ŌĆō Commonwealth Legal Information Institute

AsianLII ŌĆō Asian Legal Information Institute (AsianLII)

AustLII ŌĆō Australasian Legal Information Institute

BaiLII ŌĆō British and Irish Legal Information Institute

CanLII ŌĆō Canadian Legal Information Institute

NZLII ŌĆō New Zealand Legal Information Institute

PacLII ŌĆō Pacific Islands Legal Information Institute

SAfLII ŌĆō Southern African Legal Information Institute

{{authority control Main topic articles Justice

unconstitutional

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

. For example, in '' Brown v. Board of Education'', the United States Supreme Court nullified many state statutes that had established racially segregated schools, finding such statutes to be incompatible with the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

A judiciary is theoretically bound by the constitution, just as all other government bodies are. In most countries judges may only interpret the constitution and all other laws. But in common law countries, where matters are not constitutional, the judiciary may also create law under the doctrine of precedent

A precedent is a principle or rule established in a previous legal case that is either binding on or persuasive for a court or other tribunal when deciding subsequent cases with similar issues or facts. Common-law legal systems place great valu ...

. The UK, Finland and New Zealand assert the ideal of parliamentary sovereignty, whereby the unelected judiciary may not overturn law passed by a democratic legislature.

In communist state

A communist state, also known as a MarxistŌĆōLeninist state, is a one-party state that is administered and governed by a communist party guided by MarxismŌĆōLeninism. MarxismŌĆōLeninism was the Ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet U ...

s, such as China, the courts are often regarded as parts of the executive, or subservient to the legislature; governmental institutions and actors exert thus various forms of influence on the judiciary. In Muslim countries, courts often examine whether state laws adhere to the Sharia: the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt may invalidate such laws,Sherif, ''Constitutions of Arab Countries'', 158 and in Iran the Guardian Council ensures the compatibility of the legislation with the "criteria of Islam".

Legislature

Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the Congress in Washington, D.C., the

Prominent examples of legislatures are the Houses of Parliament in London, the Congress in Washington, D.C., the Bundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet (assembly), Diet") is the German Federalism, federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representat ...

in Berlin, the Duma in Moscow, the Parlamento Italiano in Rome and the ''Assembl├®e nationale'' in Paris. By the principle of representative government people vote for politicians to carry out ''their'' wishes. Although countries like Israel, Greece, Sweden and China are unicameral

Unicameralism (from ''uni''- "one" + Latin ''camera'' "chamber") is a type of legislature, which consists of one house or assembly, that legislates and votes as one.

Unicameral legislatures exist when there is no widely perceived need for multi ...

, most countries are bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single gro ...

, meaning they have two separately appointed legislative houses.Riker, ''The Justification of Bicameralism'', 101

In the 'lower house' politicians are elected to represent smaller constituencies

An electoral district, also known as an election district, legislative district, voting district, constituency, riding, ward, division, or (election) precinct is a subdivision of a larger state (a country, administrative region, or other polit ...

. The 'upper house' is usually elected to represent states in a federal system (as in Australia, Germany or the United States) or different voting configuration in a unitary system (as in France). In the UK the upper house is appointed by the government as a house of review. One criticism of bicameral systems with two elected chambers is that the upper and lower houses may simply mirror one another. The traditional justification of bicameralism is that an upper chamber acts as a house of review. This can minimise arbitrariness and injustice in governmental action.

To pass legislation, a majority of the members of a legislature must vote

Voting is a method by which a group, such as a meeting or an Constituency, electorate, can engage for the purpose of making a collective decision making, decision or expressing an opinion usually following discussions, debates or election camp ...

for a bill (proposed law) in each house. Normally there will be several readings and amendments proposed by the different political factions. If a country has an entrenched constitution, a special majority for changes to the constitution may be required, making changes to the law more difficult. A government usually leads the process, which can be formed from Members of Parliament (e.g. the UK or Germany). However, in a presidential system, the government is usually formed by an executive and his or her appointed cabinet officials (e.g. the United States or Brazil).

Executive

The executive in a legal system serves as the centre of political authority of the

The executive in a legal system serves as the centre of political authority of the State

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* '' Our ...

. In a parliamentary system

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance

Governance is the process of interactions through the laws, norms, power or language of an organized society over a social system ( family, t ...

, as with Britain, Italy, Germany, India, and Japan, the executive is known as the cabinet, and composed of members of the legislature. The executive is led by the head of government

The head of government is the highest or the second-highest official in the executive branch of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presides over a cabinet, ...

, whose office holds power under the confidence of the legislature. Because popular elections appoint political parties to govern, the leader of a party can change in between elections.Haggard, ''Presidents, Parliaments and Policy'', 71

The head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state (polity), state#Foakes, Foakes, pp. 110ŌĆō11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international p ...

is apart from the executive, and symbolically enacts laws and acts as representative of the nation. Examples include the President of Germany (appointed by members of federal and state legislatures), the Queen of the United Kingdom (an hereditary office), and the President of Austria (elected by popular vote). The other important model is the presidential system, found in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., federal district, five ma ...

and in Brazil