Kul (Ottoman Empire) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe

'. pp. 15–26.

Notable occasions include the

Notable occasions include the

Very little is actually known about the Imperial Harem, and much of what is thought to be known is actually conjecture and imagination. There are two main reasons for the lack of accurate accounts on this subject. The first was the barrier imposed by the people of the Ottoman society – the Ottoman people did not know much about the machinations of the Imperial Harem themselves, due to it being physically impenetrable, and because the silence of insiders was enforced. The second was that any accounts from this period were from European travelers, who were both not privy to the information, and also inherently presented a Western bias and potential for misinterpretation by being outsiders to the Ottoman culture. Despite the acknowledged biases by many of these sources themselves, scandalous stories of the Imperial Harem and the sexual practices of the sultans were popular, even if they were not true. Accounts from the seventeenth century drew from both a newer, seventeenth century trend as well as a more traditional style of history-telling; they presented the appearance of debunking previous accounts and exposing new truths, while proceeding to propagate old tales as well as create new ones. However, European accounts from captives who served as pages in the imperial palace, and the reports, dispatches, and letters of ambassadors resident in Istanbul, their secretaries, and other members of their suites proved to be more reliable than other European sources. And further, of this group of more reliable sources, the writings of the Venetians in the sixteenth century surpassed all others in volume, comprehensiveness, sophistication, and accuracy.

Very little is actually known about the Imperial Harem, and much of what is thought to be known is actually conjecture and imagination. There are two main reasons for the lack of accurate accounts on this subject. The first was the barrier imposed by the people of the Ottoman society – the Ottoman people did not know much about the machinations of the Imperial Harem themselves, due to it being physically impenetrable, and because the silence of insiders was enforced. The second was that any accounts from this period were from European travelers, who were both not privy to the information, and also inherently presented a Western bias and potential for misinterpretation by being outsiders to the Ottoman culture. Despite the acknowledged biases by many of these sources themselves, scandalous stories of the Imperial Harem and the sexual practices of the sultans were popular, even if they were not true. Accounts from the seventeenth century drew from both a newer, seventeenth century trend as well as a more traditional style of history-telling; they presented the appearance of debunking previous accounts and exposing new truths, while proceeding to propagate old tales as well as create new ones. However, European accounts from captives who served as pages in the imperial palace, and the reports, dispatches, and letters of ambassadors resident in Istanbul, their secretaries, and other members of their suites proved to be more reliable than other European sources. And further, of this group of more reliable sources, the writings of the Venetians in the sixteenth century surpassed all others in volume, comprehensiveness, sophistication, and accuracy.

The concubines of the Ottoman Sultan consisted chiefly of purchased slaves. The Sultan's concubines were generally of Christian origin (usually European, Circassian, or Georgian). Most of the elites of the Harem Ottoman Empire included many women, such as the sultan's mother, preferred concubines, royal concubines, children (princes/princess), and administrative personnel. The administrative personnel of the palace were made up of many high-ranking women officers, they were responsible for the training of Jariyes for domestic chores. The mother of a Sultan, though technically a slave, received the extremely powerful title of ''

The concubines of the Ottoman Sultan consisted chiefly of purchased slaves. The Sultan's concubines were generally of Christian origin (usually European, Circassian, or Georgian). Most of the elites of the Harem Ottoman Empire included many women, such as the sultan's mother, preferred concubines, royal concubines, children (princes/princess), and administrative personnel. The administrative personnel of the palace were made up of many high-ranking women officers, they were responsible for the training of Jariyes for domestic chores. The mother of a Sultan, though technically a slave, received the extremely powerful title of ''

'' which raised her to the status of a ruler of the Empire (see

had only five of them that were freed slaves after they were concubines to the Sultan.

The concubines were guarded by enslaved

Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

was a lawful institution and a significant part of the Ottoman Empire's economy and traditional society. The main sources of slaves were wars and politically organized enslavement expeditions in the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

, Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

, Southern Europe

Southern Europe is the southern regions of Europe, region of Europe. It is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is essentially marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of Southern Europe include some or all of these countrie ...

, the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

, and Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

. It has been reported that the selling price of slaves decreased after large military operations.Spyropoulos Yannis, Slaves and freedmen in 17th- and early 18th-century Ottoman Crete, ''Turcica'', 46, 2015, p. 181, 182. In Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

(present-day Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

), the administrative and political center of the Ottoman Empire, about a fifth of the 16th- and 17th-century population consisted of slaves. Statistics of these centuries suggest that Istanbul's additional slave imports from the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

have totaled around 2.5 million from 1453 to 1700.

Even after several measures to ban slavery in the late 19th century, the practice continued largely unabated into the early 20th century. As late as 1908, female slaves were still sold in the Ottoman Empire. Sexual slavery

Sexual slavery and sexual exploitation is an attachment of any ownership rights, right over one or more people with the intent of Coercion, coercing or otherwise forcing them to engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activities. This include ...

was a central part of the Ottoman slave system throughout the history of the institution.

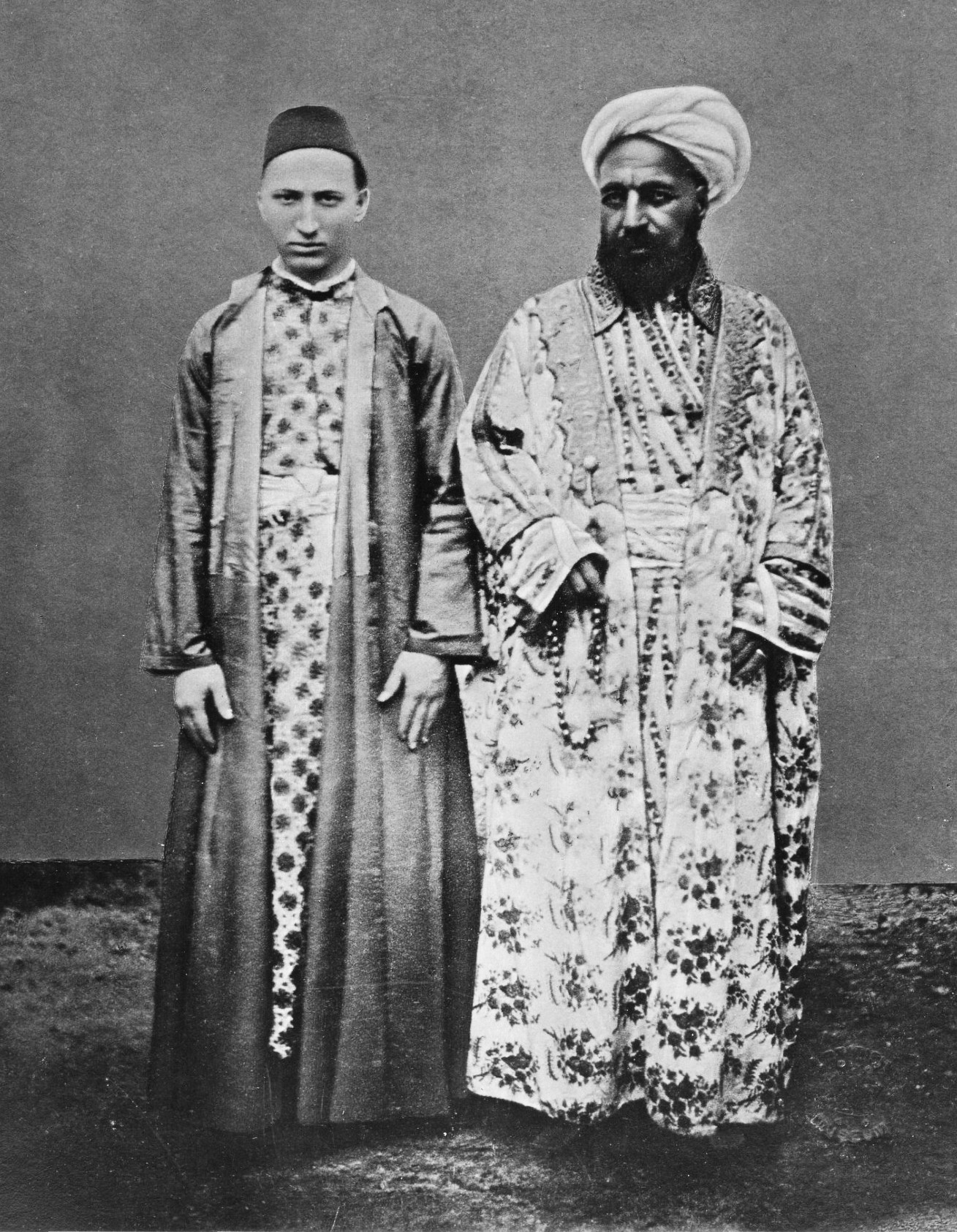

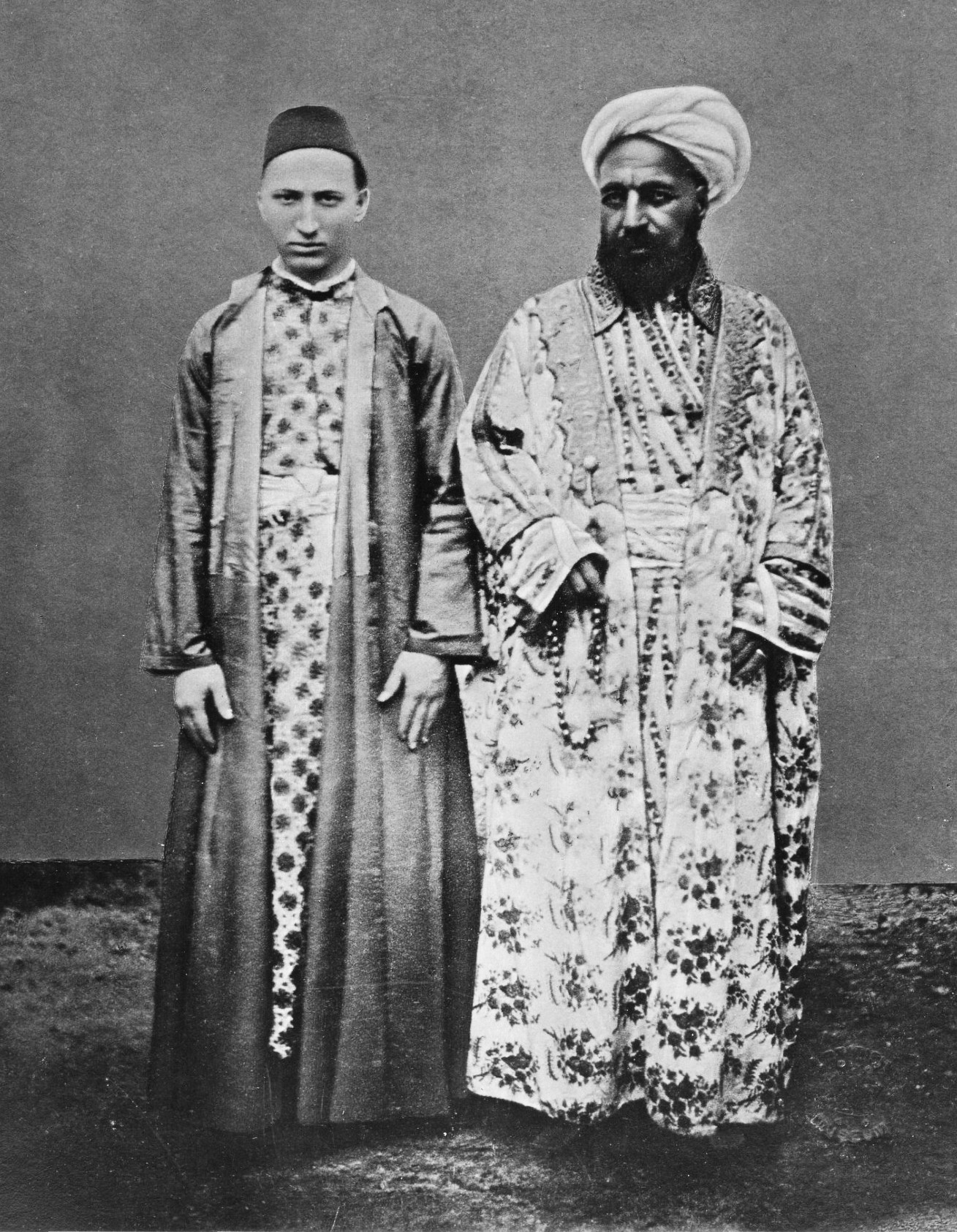

A member of the Ottoman slave class, called a ''kul Kul or KUL may refer to:

Airports

* KUL, current IATA code for Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia

* KUL, former IATA code for Sultan Abdul Aziz Shah Airport (Subang Airport), Malaysia

Populated places

* Kul, Iran, a village in Kurdistan ...

'' in Turkish

Turkish may refer to:

*a Turkic language spoken by the Turks

* of or about Turkey

** Turkish language

*** Turkish alphabet

** Turkish people, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

*** Turkish citizen, a citizen of Turkey

*** Turkish communities and mi ...

, could achieve high status. Eunuch

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millennium ...

harem

Harem (Persian: حرمسرا ''haramsarā'', ar, حَرِيمٌ ''ḥarīm'', "a sacred inviolable place; harem; female members of the family") refers to domestic spaces that are reserved for the women of the house in a Muslim family. A hare ...

guards and janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ( ...

are some of the better known positions an enslaved person could hold, but enslaved women were actually often supervised by them. However, women played and held the most important roles within the Harem institution.

A large percentage of officials in the Ottoman government were bought slaves, raised free, and integral to the success of the Ottoman Empire from the 14th century into the 19th. Many enslaved officials themselves owned numerous slaves, although the Sultan

Sultan (; ar, سلطان ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it ...

himself owned by far the most. By raising and specially training slaves as officials in palace schools such as Enderun, where they were taught to serve the Sultan and other educational subjects, the Ottomans created administrators with intricate knowledge of government, and fanatic loyalty.

Early Ottoman slavery

In the mid-14th century,Murad I

Murad I ( ota, مراد اول; tr, I. Murad, Murad-ı Hüdavendigâr (nicknamed ''Hüdavendigâr'', from fa, خداوندگار, translit=Khodāvandgār, lit=the devotee of God – meaning "sovereign" in this context); 29 June 1326 – 15 Jun ...

built an army of slaves, referred to as the ''Kapıkulu

''Kapıkulu'' ( ota, قپوقولو اوجاغی, ''Kapıkulu Ocağı'', "Slaves of the Sublime Porte") was the collective name for the Household Division of the Ottoman Sultans. They included the Janissary infantry corps as well as the Six Divis ...

''. The new force was based on the Sultan's right to a fifth of the war booty, which he interpreted to include captives taken in battle. The captives were trained in the sultan's personal service. The ''devşirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

'' system could be considered a form of slavery because the Sultans had absolute power over them. However, as the 'servant' or 'kul Kul or KUL may refer to:

Airports

* KUL, current IATA code for Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia

* KUL, former IATA code for Sultan Abdul Aziz Shah Airport (Subang Airport), Malaysia

Populated places

* Kul, Iran, a village in Kurdistan ...

' of the sultan, they had high status within the Ottoman society because of their training and knowledge. They could become the highest officers of the state and the military elite, and most recruits were privileged and remunerated. Though ordered to cut all ties with their families, a few succeeded in dispensing patronage at home. Christian parents might thus implore, or even bribe, officials to take their sons. Indeed, Bosnian and Albanian Muslims successfully requested their inclusion in the system.

Slaves were traded in special marketplaces called "Esir" or "Yesir" that were located in most towns and cities, central to the Ottoman Empire. It is said that Sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

"the Conqueror" established the first Ottoman slave market in Constantinople in the 1460s, probably where the former Byzantine slave market had stood. According to Nicolas de Nicolay

Nicolas de Nicolay, Sieur d'Arfeville & de Belair, (1517–1583) of the Nicolay (family) was a French geographer.

Biography

Born at la Grave in Oisans, in the Dauphiné, he left France in 1542 to participate in the siege of Perpignan which was t ...

, there were slaves of all ages and both sexes, most were displayed naked to be thoroughly checked – especially children and young women – by possible buyers.

Ottoman slavery in Central and Eastern Europe

In the ''devşirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

'', which connotes "draft", "blood tax" or "child collection", young Christian boys from the Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

were taken from their homes and families, forcibly converted to Islam, and enlisted into the most famous branch of the ''Kapıkulu'', the Janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ( ...

, a special soldier class of the Ottoman army

The military of the Ottoman Empire ( tr, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun silahlı kuvvetleri) was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire.

Army

The military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the ...

that became a decisive faction in the Ottoman invasions of Europe. Most of the military commanders of the Ottoman forces, imperial administrators, and ''de facto'' rulers of the Empire, such as Sokollu Mehmed Pasha

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha ( ota, صوقوللى محمد پاشا, Ṣoḳollu Meḥmed Pașa, tr, Sokollu Mehmet Paşa; ; ; 1506 – 11 October 1579) was an Ottoman statesman most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in ...

, were recruited in this way. By 1609, the Sultan's ''Kapıkulu'' forces increased to about 100,000.

A Hutterite

Hutterites (german: link=no, Hutterer), also called Hutterian Brethren (German: ), are a communal ethnoreligious group, ethnoreligious branch of Anabaptism, Anabaptists, who, like the Amish and Mennonites, trace their roots to the Radical Refor ...

chronicle reports that in 1605, during the Long Turkish War

The Long Turkish War or Thirteen Years' War was an indecisive land war between the Habsburg monarchy and the Ottoman Empire, primarily over the Principalities of Wallachia, Transylvania, and Moldavia. It was waged from 1593 to 1606 but in Europ ...

, some 240 Hutterites were abducted from their homes in Upper Hungary

Upper Hungary is the usual English translation of ''Felvidék'' (literally: "Upland"), the Hungarian term for the area that was historically the northern part of the Kingdom of Hungary, now mostly present-day Slovakia. The region has also been ...

by the Ottoman Turkish army and their Tatar

The Tatars ()Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

allies, and sold into Ottoman slavery. Many worked in the palace or for the Sultan personally.

On the basis of a list of estates belonging to members of the ruling class kept in in the Collins English Dictionary is an umbrella term for different

Edirne

Edirne (, ), formerly known as Adrianople or Hadrianopolis (Greek: Άδριανούπολις), is a city in Turkey, in the northwestern part of the province of Edirne in Eastern Thrace. Situated from the Greek and from the Bulgarian borders, ...

between 1545 and 1659, the following data was collected: out of 93 estates, 41 had slaves. The total number of slaves in the estates was 140; 54 female and 86 male. 134 of them bore Muslim names, 5 were not defined, and 1 was a Christian woman. Some of these slaves appear to have been employed on farms. In conclusion, the ruling class, because of extensive use of warrior slaves and because of its own high purchasing capacity, was undoubtedly the single major group keeping the slave market alive in the Ottoman Empire.

Rural slavery was largely a phenomenon endemic to the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range, have historically ...

region, which was carried to Anatolia and Rumelia after the Circassian migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

in 1864. Conflicts frequently emerged within the immigrant community and the Ottoman Establishment intervened on the side of the slaves at selective times.

The Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate ( crh, , or ), officially the Great Horde and Desht-i Kipchak () and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary ( la, Tartaria Minor), was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to ...

maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East until the early eighteenth century. In a series of slave raids

Slave raiding is a military raid for the purpose of capturing people and bringing them from the raid area to serve as slaves. Once seen as a normal part of warfare, it is nowadays widely considered a crime. Slave raiding has occurred since ant ...

euphemistically known as the " harvesting of the steppe", Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace

...

enslaved East Slavic peasants. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and, after 1791, as the Commonwealth of Poland, was a bi-confederal state, sometimes called a federation, of Crown of the Kingdom of ...

and Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

suffered a series of Tatar invasions

This article lists conflicts in Europe during the invasions of and subsequent occupations by the Mongol Empire and its successor states. The Mongol invasion of Europe took place in the 13th century. This resulted in the occupation of much of Easter ...

, the goal of which was to loot, pillage, and capture slaves, the Slavic languages even developed a term for the Ottoman slavery (, based on Turkish and Arabic words for capture - ''esir'' or ''asir''). The borderland area to the south-east was in a state of semi-permanent warfare until the 18th century. It is estimated that up to 75% of the Crimean population consisted of slaves or freed slaves

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

. The 17th century Ottoman writer and traveller Evliya Çelebi

Derviş Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi ( ota, اوليا چلبى), was an Ottoman explorer who travelled through the territory of the Ottoman Empire and neighboring lands over a period of forty years, recording ...

estimated that there were about 400,000 slaves in the Crimea but only 187,000 free Muslims. Polish historian Bohdan Baranowski assumed that in the 17th century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (present-day Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

and Belarus

Belarus,, , ; alternatively and formerly known as Byelorussia (from Russian ). officially the Republic of Belarus,; rus, Республика Беларусь, Respublika Belarus. is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by R ...

) lost an average of 20,000 yearly and as many as one million in all years combined from 1500 to 1644.Brian L. Davies (2014). Warfare, State and Society on the Black Sea Steppe

'. pp. 15–26.

Routledge

Routledge () is a British multinational publisher. It was founded in 1836 by George Routledge, and specialises in providing academic books, journals and online resources in the fields of the humanities, behavioural science, education, law, and ...

.

Prices and taxes

A study of theslave market

A slave market is a place where slaves are bought and sold. These markets became a key phenomenon in the history of slavery.

Slave markets in the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire during the mid-14th century, slaves were traded in special ...

of Ottoman Crete

The island of Crete ( ota, گریت ''Girīt'') was declared an Ottoman province (eyalet) in 1646, after the Ottomans managed to conquer the western part of the island as part of the Cretan War, but the Venetians maintained their hold on the c ...

produces details about the prices of slaves. Factors such as age, race, virginity

Virginity is the state of a person who has never engaged in sexual intercourse. The term ''virgin'' originally only referred to sexually inexperienced women, but has evolved to encompass a range of definitions, as found in traditional, modern ...

etc. significantly influenced prices. The most expensive slaves were those between 10 and 35 years of age, with the highest prices for European virgin girls 13–25 years of age and teenaged boys. The cheaper slaves were those with disabilities and sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

ns. Prices in Crete ranged between 65 and 150 "''esedi guruş''" (see Kuruş

Kuruş ( ; ), also gurush, ersh, gersh, grush, grosha, and grosi, are all names for currency denominations in and around the territories formerly part of the Ottoman Empire. The variation in the name stems from the different languages it is us ...

). But even the lowest prices were affordable to only high income persons. For example, in 1717 a 12-year-old boy with mental disabilities was sold for 27 ''guruş'', an amount that could buy in the same year of lamb meat, of bread or of milk. In 1671 a female slave was sold in Crete for 350 ''guruş'', while at the same time the value of a large two-floor house with a garden in Chania

Chania ( el, Χανιά ; vec, La Canea), also spelled Hania, is a city in Greece and the capital of the Chania regional unit. It lies along the north west coast of the island Crete, about west of Rethymno and west of Heraklion.

The muni ...

was 300 ''guruş''. There were various taxes to be paid on the importation and selling of slaves. One of them was the "''pençik''" or "''penç-yek''" tax, literally meaning "one fifth". This taxation was based on verses of the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

, according to which one fifth of the spoils of war belonged to God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

, to the Prophet and his family

''His Family'' is a novel by Ernest Poole published in 1917 about the life of a New York widower and his three daughters in the 1910s. It received the first Pulitzer Prize for the Novel in 1918.

Plot introduction

''His Family'' tells the story of ...

, to orphans, to those in need and to travelers. The Ottomans probably started collecting ''pençik'' at the time of Sultan Murad I

Murad I ( ota, مراد اول; tr, I. Murad, Murad-ı Hüdavendigâr (nicknamed ''Hüdavendigâr'', from fa, خداوندگار, translit=Khodāvandgār, lit=the devotee of God – meaning "sovereign" in this context); 29 June 1326 – 15 Jun ...

(1362–1389). ''Pençik'' was collected both in money and in kind, the latter including slaves as well. Tax was not collected in some cases of war captives. With war captives, slaves were given to soldiers and officers as a motive to participate in war.

The recapture of runaway slaves was a job for private individuals called "''yavacis''". Whoever managed to find a runaway enslaved person seeking their freedom would collect a fee of "good news" from the ''yavaci'' and the latter took this fee plus other expenses from the slaves' master. Slaves could also be rented, inherited, pawned, exchanged or given as gifts.

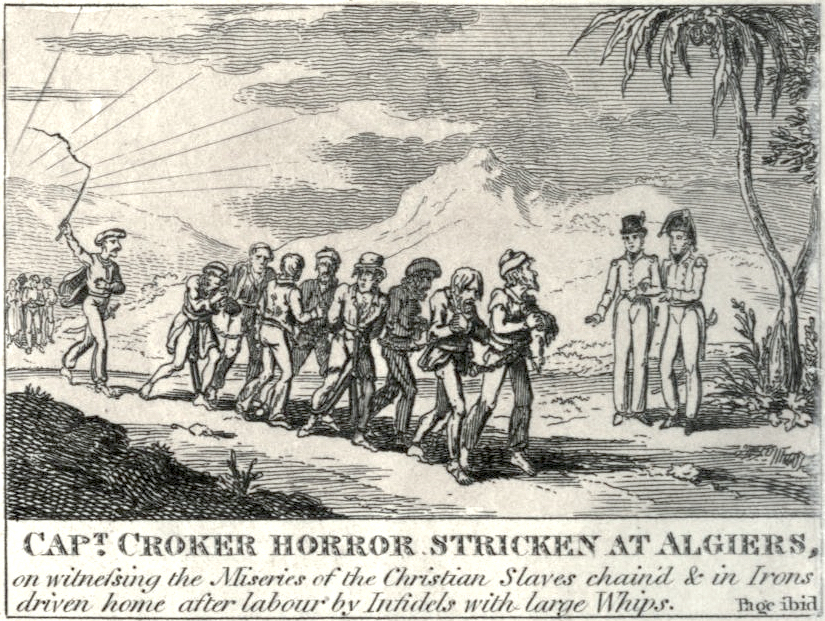

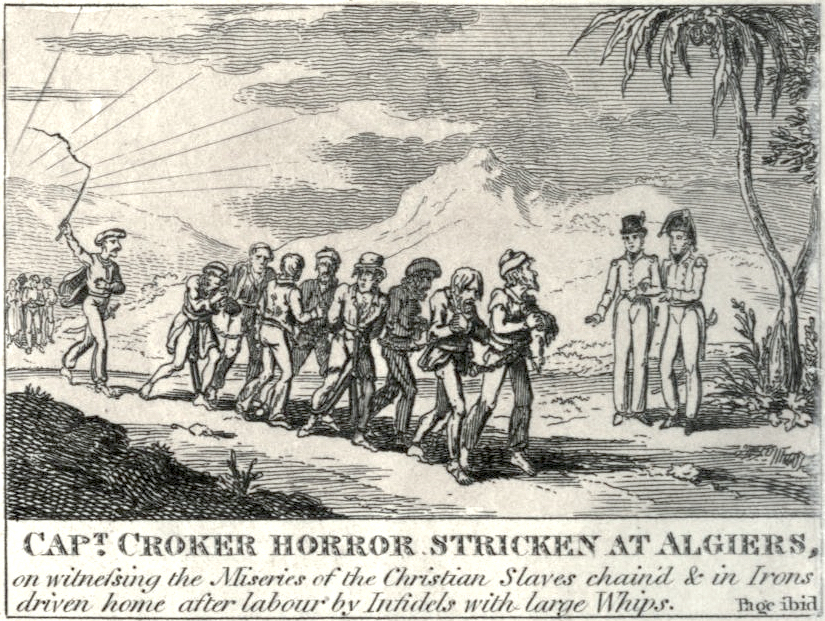

Barbary slave raids

For centuries, large vessels on the Mediterranean relied on Europeangalley slaves

A galley slave was a slave rowing in a galley, either a convicted criminal sentenced to work at the oar ('' French'': galérien), or a kind of human chattel, often a prisoner of war, assigned to the duty of rowing.

In the ancient Mediterranea ...

supplied by Ottoman and Barbary slave trade

The Barbary slave trade involved slave markets on the Barbary Coast of North Africa, which included the Ottoman states of Algeria, Tunisia and Tripolitania and the independent sultanate of Morocco, between the 16th and 19th century. The Ottom ...

rs. Hundreds of thousands of Europeans were captured by Barbary pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, Libya, Tripoli. This area was known i ...

and sold as slaves in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 19th centuries. These slave raids were conducted largely by Arabs

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Wester ...

and Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

rather than Ottoman Turks. However, during the height of the Barbary slave trade in the 16th, 17th, 18th centuries, the Barbary states were subject to Ottoman jurisdiction

Jurisdiction (from Latin 'law' + 'declaration') is the legal term for the legal authority granted to a legal entity to enact justice. In federations like the United States, areas of jurisdiction apply to local, state, and federal levels.

Jur ...

and, with the exception of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to ...

, were ruled by Ottoman pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

s. Furthermore, many slaves captured by the Barbary corsairs were sold eastward into Ottoman territories before, during, and after Barbary's period of Ottoman rule.

Notable occasions include the

Notable occasions include the Turkish Abductions

The Turkish Abductions ( is, Tyrkjaránið) were a series of Slave raiding, slave raids by Barbary pirates, pirates from Northwest Africa that took place in Iceland in the summer of 1627.

The pirates came from the cities of Algiers and Salé.

T ...

.

Zanj slaves

As there were restrictions on the enslavement of Muslims and of "People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

" (Jews and Christians) living under Muslim rule, pagan areas in Africa became a popular source of slaves. Known as the Zanj

Zanj ( ar, زَنْج, adj. , ''Zanjī''; fa, زنگی, Zangi) was a name used by medieval Muslim geographers to refer to both a certain portion of Southeast Africa (primarily the Swahili Coast) and to its Bantu inhabitants. This word is also ...

(Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

*Black Association for National ...

), these slaves originated mainly from the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes ( sw, Maziwa Makuu; rw, Ibiyaga bigari) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. They include Lake Victoria, the second-largest fresh water lake in the ...

region as well as from Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo, ...

. The Zanj were employed in households, on plantations and in the army as slave-soldiers. Some could ascend to become high-rank officials, but in general Zanj were considered inferior to European and Caucasian slaves.

One way for Zanj slaves to serve in high-ranking roles involved becoming one of the African eunuchs of the Ottoman palace. This position was used as a political tool by Sultan Murad III

Murad III ( ota, مراد ثالث, Murād-i sālis; tr, III. Murad; 4 July 1546 – 16 January 1595) was Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1574 until his death in 1595. His rule saw battles with the Habsburgs and exhausting wars with the Saf ...

() as an attempt to destabilize the Grand Vizier by introducing another source of power to the capital.

After being purchased by a member of the Ottoman court

Ottoman court was the culture that evolved around the court of the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman court was held at the Topkapı Palace in Constantinople where the sultan was served by an army of pages and scholars. Some served in the Treasury and the ...

, Mullah Ali was introduced to the first chief Black eunuch, Mehmed Aga. Due to Mehmed Aga's influence, Mullah Ali was able to make connections with prominent colleges and tutors of the day, including Hoca Sadeddin Efendi

Hoca Sadeddin Efendi ( ota, خواجه سعد الدین افندی; 1536/1537 – October 2, 1599İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, ''Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı'', Türkiye Yayınevi, İstanbul, 1971, p. 118. ) was an Ottoman scholar, official, and histor ...

(1536/37 – 1599), the tutor of Murad III. Through the network he had built with the help of his education and the black eunuchs, Mullah Ali secured several positions early on. He worked as a teacher in Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

, a deputy judge, and an inspector of royal endowments. In 1620, Mullah Ali was appointed as chief judge of the capital and in 1621 he became the ''kadiasker'', or chief judge, of the European provinces and the first black man to sit on the imperial council. At this time, he had risen to such power that a French ambassador described him as the person who truly ran the empire.

Although Mullah Ali was often challenged because of his blackness and his connection to the African eunuchs, he was able to defend himself through his powerful network of support and his own intellectual productions. As a prominent scholar, he wrote an influential book in which he used logic and the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

to debunk stereotypes and prejudice against dark-skinned people and to delegitimize arguments for why Africans should be slaves.

Today, thousands of Afro Turks

Afro-Turks ( tr, Afrikalı Türkler) are Turkish people of African Zanj ( Bantu) descent, who trace their origin to the Ottoman slave trade like the Afro-Abkhazians. Afro-Turk population is estimated to be between 5,000 and 20,000 people. Afr ...

, the descendants of the Zanj slaves in the Ottoman Empire, continue to live in modern Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. An Afro-Turk, Mustafa Olpak, founded the first officially recognised organisation of Afro-Turks, the Africans' Culture and Solidarity Society (Afrikalılar Kültür ve Dayanışma Derneği) in Ayvalık

Ayvalık () is a seaside town on the northwestern Aegean coast of Turkey. It is a district of Balıkesir province. The town centre is connected to Cunda Island by a causeway and is surrounded by the archipelago of Ayvalık Islands, which face ...

. Olpak claims that about 2,000 Afro-Turks live in modern Turkey.

East African slaves

The UpperNile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

Valley and southern Ethiopia

Ethiopia, , om, Itiyoophiyaa, so, Itoobiya, ti, ኢትዮጵያ, Ítiyop'iya, aa, Itiyoppiya officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country in the Horn of Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the ...

were also significant sources of slaves in the Ottoman Empire. Although the Christian Ethiopians defeated the Ottoman invaders, they did not tackle enslavement of southern pagans and muslims as long as they were paid taxes by the Ottoman slave traders. Pagans and muslims from southern Ethiopian areas such as kaffa and jimma were taken north to Ottoman Egypt

The Eyalet of Egypt (, ) operated as an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire from 1517 to 1867. It originated as a result of the conquest of Mamluk Egypt by the Ottomans in 1517, following the Ottoman–Mamluk War (1516–17) and the a ...

and also to ports on the Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

for export to Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

and the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Persis, Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a Mediterranean sea (oceanography), me ...

. In 1838, it was estimated that 10,000 to 12,000 slaves were arriving in Egypt annually using this route . A significant number of these slaves were young women, and European travellers in the region recorded seeing large numbers of Ethiopian slaves in the Arab world at the time. The Swiss traveller Johann Louis Burckhardt estimated that 5,000 Ethiopian slaves passed through the port of Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

alone every year, headed for Arabia, and added that most of them were young women who ended up being prostituted by their owners. The English traveler Charles M. Doughty

Charles Montagu Doughty (19 August 1843 – 20 January 1926) was an English poet, writer, explorer, adventurer and traveller, best known for his two-volume 1888 travel book '' Travels in Arabia Deserta''.

Early life and education

Son of Rev. Ch ...

later (in the 1880s) also recorded Ethiopian slaves in Arabia, and stated that they were brought to Arabia every year during the Hajj

The Hajj (; ar, حَجّ '; sometimes also spelled Hadj, Hadji or Haj in English) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for Muslims that must be carried ...

pilgrimage. In some cases, female Ethiopian slaves were preferred to male ones, with some Ethiopian slave cargoes recording female-to-male slave ratios of two to one.

Slaves in the Imperial Harem

Very little is actually known about the Imperial Harem, and much of what is thought to be known is actually conjecture and imagination. There are two main reasons for the lack of accurate accounts on this subject. The first was the barrier imposed by the people of the Ottoman society – the Ottoman people did not know much about the machinations of the Imperial Harem themselves, due to it being physically impenetrable, and because the silence of insiders was enforced. The second was that any accounts from this period were from European travelers, who were both not privy to the information, and also inherently presented a Western bias and potential for misinterpretation by being outsiders to the Ottoman culture. Despite the acknowledged biases by many of these sources themselves, scandalous stories of the Imperial Harem and the sexual practices of the sultans were popular, even if they were not true. Accounts from the seventeenth century drew from both a newer, seventeenth century trend as well as a more traditional style of history-telling; they presented the appearance of debunking previous accounts and exposing new truths, while proceeding to propagate old tales as well as create new ones. However, European accounts from captives who served as pages in the imperial palace, and the reports, dispatches, and letters of ambassadors resident in Istanbul, their secretaries, and other members of their suites proved to be more reliable than other European sources. And further, of this group of more reliable sources, the writings of the Venetians in the sixteenth century surpassed all others in volume, comprehensiveness, sophistication, and accuracy.

Very little is actually known about the Imperial Harem, and much of what is thought to be known is actually conjecture and imagination. There are two main reasons for the lack of accurate accounts on this subject. The first was the barrier imposed by the people of the Ottoman society – the Ottoman people did not know much about the machinations of the Imperial Harem themselves, due to it being physically impenetrable, and because the silence of insiders was enforced. The second was that any accounts from this period were from European travelers, who were both not privy to the information, and also inherently presented a Western bias and potential for misinterpretation by being outsiders to the Ottoman culture. Despite the acknowledged biases by many of these sources themselves, scandalous stories of the Imperial Harem and the sexual practices of the sultans were popular, even if they were not true. Accounts from the seventeenth century drew from both a newer, seventeenth century trend as well as a more traditional style of history-telling; they presented the appearance of debunking previous accounts and exposing new truths, while proceeding to propagate old tales as well as create new ones. However, European accounts from captives who served as pages in the imperial palace, and the reports, dispatches, and letters of ambassadors resident in Istanbul, their secretaries, and other members of their suites proved to be more reliable than other European sources. And further, of this group of more reliable sources, the writings of the Venetians in the sixteenth century surpassed all others in volume, comprehensiveness, sophistication, and accuracy.

The concubines of the Ottoman Sultan consisted chiefly of purchased slaves. The Sultan's concubines were generally of Christian origin (usually European, Circassian, or Georgian). Most of the elites of the Harem Ottoman Empire included many women, such as the sultan's mother, preferred concubines, royal concubines, children (princes/princess), and administrative personnel. The administrative personnel of the palace were made up of many high-ranking women officers, they were responsible for the training of Jariyes for domestic chores. The mother of a Sultan, though technically a slave, received the extremely powerful title of ''

The concubines of the Ottoman Sultan consisted chiefly of purchased slaves. The Sultan's concubines were generally of Christian origin (usually European, Circassian, or Georgian). Most of the elites of the Harem Ottoman Empire included many women, such as the sultan's mother, preferred concubines, royal concubines, children (princes/princess), and administrative personnel. The administrative personnel of the palace were made up of many high-ranking women officers, they were responsible for the training of Jariyes for domestic chores. The mother of a Sultan, though technically a slave, received the extremely powerful title of ''Valide Sultan #REDIRECT Valide sultan #REDIRECT Valide sultan

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from miscapitalization{{R unprintworthy ...

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from miscapitalization{{R unprintworthy ...Sultanate of Women

The Sultanate of Women ( Turkish: ''Kadınlar saltanatı'') was a period when wives and mothers of the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire exerted extraordinary political influence.

This phenomenon took place from roughly 1528-30 to 1715, beginning in ...

). The mother of the Sultan played a substantial role in decision-making for the Imperial Harem. One notable example was Kösem Sultan

Kösem Sultan ( ota, كوسم سلطان, translit=;, 1589Baysun, M. Cavid, s.v. "Kösem Walide or Kösem Sultan" in ''The Encyclopaedia of Islam'' vol. V (1986), Brill, p. 272 " – 2 September 1651), also known as Mahpeyker SultanDouglas Arth ...

, daughter of a Greek Christian priest, who dominated the Ottoman Empire during the early decades of the 17th century. Roxelana

Hurrem Sultan (, ota, خُرّم سلطان, translit=Ḫurrem Sulṭān, tr, Hürrem Sultan, label=Modern Turkish; 1500 – 15 April 1558), also known as Roxelana ( uk, Роксолана}; ), was the chief consort and legal wife of the Ottom ...

(also known as ''Hürrem Sultan''), another notable example, was the favorite wife of Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I ( ota, سليمان اول, Süleyman-ı Evvel; tr, I. Süleyman; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the West and Suleiman the Lawgiver ( ota, قانونى سلطان سليمان, Ḳ� ...

. Many historians who study the Ottoman Empire, rely on the factual evidence of observers of the 16th and 17th century Islam. The tremendous growth of the Harem institution reconstructed the careers and roles of women in the dynasty power structure. There were harem women who were the mothers, legal wives, consorts, Kalfas, and concubines of the Ottoman Sultan. Only a small amount of these harem women were freed from slavery and married their spouses. These women were : Hurrem Sultan, Nurbanu Sultan, Kosem Sultan, Gulnus Sultan, Bezmialem Sultan and Perestu Sultan. The Empress mothers who held the title Valide Sultan #REDIRECT Valide sultan #REDIRECT Valide sultan

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from miscapitalization{{R unprintworthy ...

{{redirect category shell, {{R from move{{R from miscapitalization{{R unprintworthy ...eunuchs

A eunuch ( ) is a male who has been castrated. Throughout history, castration often served a specific social function.

The earliest records for intentional castration to produce eunuchs are from the Sumerian city of Lagash in the 2nd millennium ...

, often from pagan Africa. The eunuchs were headed by the Kizlar Agha

The kizlar agha ( ota, قيزلر اغاسی, tr, kızlar ağası, ), formally the agha of the House of Felicity ( ota, links=no, دار السعاده اغاسي, tr, links=no, Darüssaade Ağası), was the head of the eunuchs who guarded the i ...

(" agha of the lave

''Lave'' was an ironclad floating battery of the French Navy during the 19th century. She was part of the of floating batteries.

In the 1850s, the British and French navies deployed iron-armoured floating batteries as a supplement to the wooden ...

girls"). While some interpretation of Islamic law forbade the emasculation of a man, Ethiopian Christians had no such compunctions; thus, they enslaved members of territories to the south and sold the resulting eunuchs to the Ottoman Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The nam ...

.Gwyn Campbell, ''The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia'', 1 edition, (Routledge: 2003), p.ix The Coptic Orthodox Church

The Coptic Orthodox Church ( cop, Ϯⲉⲕ̀ⲕⲗⲏⲥⲓⲁ ⲛ̀ⲣⲉⲙⲛ̀ⲭⲏⲙⲓ ⲛ̀ⲟⲣⲑⲟⲇⲟⲝⲟⲥ, translit=Ti.eklyseya en.remenkimi en.orthodoxos, lit=the Egyptian Orthodox Church; ar, الكنيسة القبطي� ...

participated extensively in the slave trade of eunuchs. Coptic priests sliced the penis and testicles off boys around the age of eight in a castration

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which an individual loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmaceut ...

operation.

The eunuch boys were then sold in the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The majority of Ottoman eunuchs endured castration at the hands of the Copts at Abou Gerbe monastery on Mount Ghebel Eter. Boys were captured from the African Great Lakes region and other areas in Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

like Darfur

Darfur ( ; ar, دار فور, Dār Fūr, lit=Realm of the Fur) is a region of western Sudan. ''Dār'' is an Arabic word meaning "home f – the region was named Dardaju ( ar, دار داجو, Dār Dājū, links=no) while ruled by the Daju, ...

and Kordofan

Kordofan ( ar, كردفان ') is a former province of central Sudan. In 1994 it was divided into three new federal states: North Kordofan, South Kordofan and West Kordofan. In August 2005, West Kordofan State was abolished and its territory di ...

, enslaved, then sold to customers in Egypt.

While the majority of eunuchs came from Africa, most white eunuchs were selected from the ''devshirme

Devshirme ( ota, دوشیرمه, devşirme, collecting, usually translated as "child levy"; hy, Մանկահավաք, Mankahavak′. or "blood tax"; hbs-Latn-Cyrl, Danak u krvi, Данак у крви, mk, Данок во крв, Danok vo krv ...

'', Christian boys recruited from the Ottoman Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

and Anatolian Greeks. Differently from the black eunuchs, who were castrated in their place of origin, they were castrated at the palace. A number of eunuchs of ''devshirme'' origin went on to hold important positions in the Ottoman military and the government, such as grand viziers

Grand vizier ( fa, وزيرِ اعظم, vazîr-i aʾzam; ota, صدر اعظم, sadr-ı aʾzam; tr, sadrazam) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. The office of Grand Vizier was first h ...

Hadım Ali Pasha

Hadım Ali Pasha (Turkish: ''Hadım Ali Paşa''; died July 1511), also known as Atik Ali Pasha (Turkish: ''Atik Ali Paşa''), was an Ottoman statesman and eunuch (''hadım'' means "eunuch" in Turkish) of Bosnian origin. He served as governor of ...

, Sinan Borovinić

Sinan (Arabic: سنان ''sinān'') is a name found in Arabic and Early Arabic, meaning ''spearhead''. The name may also be related to the Ancient Greek name Sinon. It was used as a male given name.

Etymology

The word is possibly stems from th ...

, and Hadım Hasan Pasha

Hadım Hasan Pasha ( ota, خادم حسن پاشا; died 1598 in Constantinople) was an Ottoman statesman. He was an Albanian Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire from 1597 to 1598.İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, Türkiye Yayın ...

.

Ottoman sexual slavery

In the Ottoman empire, female slaves owned by men were sexually available to their masters, and their children were considered as legitimate as any child born of a free woman, however female slaves owned by women could not be available to their masters' husband by law. This means that any child of a female slave could not be sold or given away. However, due to extreme poverty, some Circassian slaves and free people in the lower classes of Ottoman society felt forced to sell their children into slavery; this provided a potential benefit for the children as well, as slavery also held the opportunity for social mobility. If a harem slave became pregnant, it also became illegal for her to be further sold in slavery, and she would gain her freedom upon her current owner's death. Slavery in and of itself was long tied with the economic and expansionist activities of the Ottoman empire. There was a major decrease in slave acquisition by the late eighteenth century as a result of the lessening of expansionist activities. War efforts were a great source of slave procurement, so the Ottoman empire had to find other methods of obtaining slaves because they were a major source of income within the empire. The Caucasian War caused a major influx of Circassian slaves into the Ottoman market and a person of modest wealth could purchase a slave with a few pieces of gold. At a time, Circassian slaves became the most abundant in the imperial harem.

In the Ottoman empire, female slaves owned by men were sexually available to their masters, and their children were considered as legitimate as any child born of a free woman, however female slaves owned by women could not be available to their masters' husband by law. This means that any child of a female slave could not be sold or given away. However, due to extreme poverty, some Circassian slaves and free people in the lower classes of Ottoman society felt forced to sell their children into slavery; this provided a potential benefit for the children as well, as slavery also held the opportunity for social mobility. If a harem slave became pregnant, it also became illegal for her to be further sold in slavery, and she would gain her freedom upon her current owner's death. Slavery in and of itself was long tied with the economic and expansionist activities of the Ottoman empire. There was a major decrease in slave acquisition by the late eighteenth century as a result of the lessening of expansionist activities. War efforts were a great source of slave procurement, so the Ottoman empire had to find other methods of obtaining slaves because they were a major source of income within the empire. The Caucasian War caused a major influx of Circassian slaves into the Ottoman market and a person of modest wealth could purchase a slave with a few pieces of gold. At a time, Circassian slaves became the most abundant in the imperial harem.

Circassians

The Circassians (also referred to as Cherkess or Adyghe; Adyghe and Kabardian: Адыгэхэр, romanized: ''Adıgəxər'') are an indigenous Northwest Caucasian ethnic group and nation native to the historical country-region of Circassia in ...

, Syrians

Syrians ( ar, سُورِيُّون, ''Sūriyyīn'') are an Eastern Mediterranean ethnic group indigenous to the Levant. They share common Levantine Semitic roots. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend of both indi ...

, and Nubians

Nubians () (Nobiin: ''Nobī,'' ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the region which is now northern Sudan and southern Egypt. They originate from the early inhabitants of the central Nile valley, believed to be one of the earliest cradles of c ...

were the three primary races of females who were sold as sex slaves (Cariye

Cariye (, "Jariya") was a title and term used for category of enslaved women concubines in the Islamic world of the Middle East.Junius P. Rodriguez: Slavery in the Modern World: A History of Political, Social, and Economic' They are particularly ...

) in the Ottoman Empire. Circassian girls were described as fair and light-skinned and were frequently enslaved by Crimean Tatars

, flag = Flag of the Crimean Tatar people.svg

, flag_caption = Flag of Crimean Tatars

, image = Love, Peace, Traditions.jpg

, caption = Crimean Tatars in traditional clothing in front of the Khan's Palace

...

then sold to Ottoman Empire to live and serve in a Harem. They were the most expensive, reaching up to 500 pounds sterling

Sterling (abbreviation: stg; Other spelling styles, such as STG and Stg, are also seen. ISO 4217, ISO code: GBP) is the currency of the United Kingdom and nine of #Crown Dependencies and British Overseas Territories, its associated territori ...

, and the most popular with the Turks. Second in popularity were Syrian girls, which came largely from coastal regions in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

. Their price could reach up to 30 pounds sterling. Nubian girls were the cheapest and least popular, fetching up to 20 pounds sterling. Sex roles and symbolism in Ottoman society functioned as a normal action of power. The palace Harem excluded enslaved women from the rest of society.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, sexual slavery

Sexual slavery and sexual exploitation is an attachment of any ownership rights, right over one or more people with the intent of Coercion, coercing or otherwise forcing them to engage in Human sexual activity, sexual activities. This include ...

was not only central to Ottoman practice but a critical component of imperial governance and elite social reproduction. Boys could also become sexual slaves, though usually they worked in places like bathhouses (hammam

A hammam ( ar, حمّام, translit=ḥammām, tr, hamam) or Turkish bath is a type of steam bath or a place of public bathing associated with the Islamic world. It is a prominent feature in the culture of the Muslim world and was inherited f ...

) and coffeehouses. During this period, historians have documented men indulging in sexual behavior with other men and getting caught. Moreover, the visual illustrations during this period of exposing a sodomite being stigmatized by a group of people with Turkish wind instruments shows the disconnect between sexuality and tradition. However those that were accepted became ''tellaks'' (masseurs), '' köçeks'' (cross-dressing dancers) or ''sāqīs'' (wine pourers) for as long as they were young and beardless. The "Beloveds" were often loved by former Beloveds that were educated and considered upper class.

Some female slaves who were enslaved by women were sold as sex workers for short periods of time. Women also purchased slaves, but usually not for sexual purposes, and most likely searched for slaves who were loyal, healthy, and had good domestic skills. Beauty was also a valued trait when looking to buy a slave because they often were seen as objects to show off to people. While prostitution was against the law, there were very little recorded instances of punishment that came to shari'a courts for pimps, prostitutes, or for the people who sought out their services. Cases that did punish prostitution usually resulted in the expulsion of the prostitute or pimp from the area they were in. However, this does not mean that these people were always receiving light punishments. Sometimes military officials took it upon themselves to enforce extra judicial punishment. This involved pimps being strung up on trees, destruction of brothels, and harassing prostitutes.

The Ottoman Imperial Harem

The Imperial Harem ( ota, حرم همايون, ) of the Ottoman Empire was the Ottoman sultan's harem – composed of the wives, servants (both female slaves and eunuchs), female relatives and the sultan's concubines – occupying a secluded ...

was similar to a training institution for concubines, and served as a way to get closer to the Ottoman elite. Women from lower-class families had especially good opportunities for social mobility in the imperial harem because they could be trained to be concubines for high-ranking military officials. Concubines had an chance for even greater power in Ottoman society if they became favorites of the sultan. The sultan would keep a large number of girls as his concubines in the New Palace, which as a result became known as "the palace of the girls" in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These concubines mainly consisted of young Christian slave girls. Accounts claim that the sultan would keep a concubine in the New Palace for a period of two months, during which time he would do with her as he pleased. They would be considered eligible for the sultan's sexual attention until they became pregnant; if a concubine became pregnant, the sultan may take her as a wife and move her to the Old Palace where they would prepare for the royal child; if she did not become pregnant by the end of the two months, she would be married off to one of the sultan's high-ranking military men. If a concubine became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter, she may still be considered for further sexual attention from the sultan. The harem system was an important part of Ottoman-Egyptian society as well; it attempted to mimic the imperial harem in many ways, including the secrecy of the harem section of the household, where the women were kept hidden away from males that were outside of their own family, the guarding of the women by black eunuchs, and also having the function of training for becoming concubines.

Decline and suppression of Ottoman slavery

Responding to the influence and pressure of European countries in the 19th century, the Empire began taking steps to curtail theslave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, which had been legally valid under Ottoman law since the beginning of the empire. One of the important campaigns against Ottoman slavery and slave trade was conducted in the Caucasus by the Russian authorities

The Government of Russia exercises executive power in the Russian Federation. The members of the government are the prime minister, the deputy prime ministers, and the federal ministers. It has its legal basis in the Constitution of the Russia ...

.

A series of decrees were promulgated that initially limited the slavery of white persons, and subsequently that of all races and religions. In 1830, a ''firman

A firman ( fa, , translit=farmân; ), at the constitutional level, was a royal mandate or decree issued by a sovereign in an Islamic state. During various periods they were collected and applied as traditional bodies of law. The word firman com ...

'' of Sultan Mahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, محمود ثانى, Maḥmûd-u s̠ânî, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

gave freedom to white slaves. This category included Circassians, who had the custom of selling their own children, enslaved Greeks who had revolted against the Empire in 1821, and some others. Attempting to suppress the practice, another ''firman'' abolishing the trade of Circassians and Georgians

The Georgians, or Kartvelians (; ka, ქართველები, tr, ), are a nation and indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. Georgian diaspora communities are also present throughout Russia, Turkey, G ...

was issued in October, 1854.

Later, slave trafficking was prohibited in practice by enforcing specific conditions of slavery in ''sharia

Sharia (; ar, شريعة, sharīʿa ) is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition. It is derived from the religious precepts of Islam and is based on the sacred scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the H ...

'', Islamic law, even though sharia permitted slavery in principle. For example, under one provision, a person who was captured could not be kept a slave if they had already been Muslim prior to their capture. Moreover, they could not be captured legitimately without a formal declaration of war, and only the Sultan could make such a declaration. As late Ottoman Sultans wished to halt slavery, they did not authorize raids for the purpose of capturing slaves, and thereby made it effectively illegal to procure new slaves, although those already in slavery remained slaves.

The Ottoman Empire and 16 other countries signed the 1890 Brussels Conference Act for the suppression of the slave trade. Clandestine slavery persisted into the early 20th century. A circular by the Ministry of Internal Affairs in October 1895 warned local authorities that some steamships

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ca ...

stripped Zanj sailors of their "certificates of liberation" and threw them into slavery. Another circular of the same year reveals that some newly freed Zanj slaves were arrested based on unfounded accusations, imprisoned and forced back to their lords.

An instruction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs to the Vali of Bassora of 1897 ordered that the children of liberated slaves be issued separate certificates of liberation to avoid both being enslaved themselves and separated from their parents. George Young, Second Secretary of the British Embassy in Constantinople, wrote in his ''Corpus of Ottoman Law'', published in 1905, that at the time of this writing, the slave trade in the Empire was practiced only as contraband. The trade continued until World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Henry Morgenthau, Sr.

Henry Morgenthau (; April 26, 1856 – November 25, 1946) was a German-born American lawyer and businessman, best known for his role as the United States Ambassador to Turkey, ambassador to the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Morgenthau was on ...

, who served as the U.S. Ambassador in Constantinople from 1913 until 1916, reported in his ''Ambassador Morgenthau's Story

''Ambassador Morgenthau's Story'' (1918) is the title of the published memoirs of Henry Morgenthau Sr., U.S. Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1913 to 1916, until the day of his resignation from the post. The book was dedicated to the then U. ...

'' that there were gangs that traded white slaves during those years. Morgenthau's writings also confirmed reports that Armenian girls were being sold as slaves during the Armenian genocide

The Armenian genocide was the systematic destruction of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, Armenian people and identity in the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), it was ...

of 1915.

The Young Turks adopted an anti-slavery stance in the early 20th century. Sultan Abdul Hamid II

Abdülhamid or Abdul Hamid II ( ota, عبد الحميد ثانی, Abd ül-Hamid-i Sani; tr, II. Abdülhamid; 21 September 1842 10 February 1918) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 31 August 1876 to 27 April 1909, and the last sultan to ...

's personal slaves were freed in 1909 but members of his dynasty were allowed to keep their slaves. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, or Mustafa Kemal Pasha until 1921, and Ghazi Mustafa Kemal from 1921 Surname Law (Turkey), until 1934 ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish Mareşal (Turkey), field marshal, Turkish National Movement, re ...

ended legal slavery in the Turkish Republic

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

. Turkey waited until 1933 to ratify the 1926 League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

convention on the suppression of slavery. Nonetheless, illegal sales of girls were reportedly continued at least into the early 1930s. Legislation explicitly prohibiting slavery was finally adopted in 1964.

See also

*Islamic views on slavery

Islamic views on slavery represent a complex and multifaceted body of Islamic thought,Brockopp, Jonathan E., “Slaves and Slavery”, in: Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān, General Editor: Jane Dammen McAuliffe, Georgetown University, Washington D ...

* History of concubinage in the Muslim world

The history of concubinage in the Muslim world encompassed the practice of a men living with a woman without marriage, where the woman was a slave, though sometimes free. If the concubine gave birth to a child, she attained a higher status k ...

* History of slavery

The history of slavery spans many cultures, nationalities, and religions from ancient times to the present day. Likewise, its victims have come from many different ethnicities and religious groups. The social, economic, and legal positions of en ...

* History of slavery in the Muslim world

The history of slavery in the Muslim world began with institutions inherited from pre-Islamic Arabia;Lewis 1994Ch.1 and the practice of keeping slaves subsequently developed in radically different ways, depending on social-political factors suc ...

* Slavery and religion

Historically, slavery has been regulated, supported, or opposed on religious grounds.

In Judaism, slaves were given a range of treatments and protections. They were to be treated as an extended family with certain protections, and they could be ...

References

Footnotes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External link

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Slavery In The Ottoman Empire Society of the Ottoman Empire Social class in the Ottoman Empire Islam and slavery