Kolyma Basin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kolyma (russian: Колыма́, ) is a region located in the

Kolyma (russian: Колыма́, ) is a region located in the

The initial efforts to develop the region began in 1932, with the building of the town of Magadan by

The initial efforts to develop the region began in 1932, with the building of the town of Magadan by

At the height of the Purges, around 1937,

At the height of the Purges, around 1937,

Calendar of events:

*1928–1929: Gold mines established in the Kolyma River region. Commencement of regular mining operations

*13 November 1931: Establishment of

Calendar of events:

*1928–1929: Gold mines established in the Kolyma River region. Commencement of regular mining operations

*13 November 1931: Establishment of

he recalled how he was released from exile temporarily and flown into

Gulag: Understanding the Magnitude of What Happened

Heritage.org (16 October 2003). Retrieved on 2016-12-14.

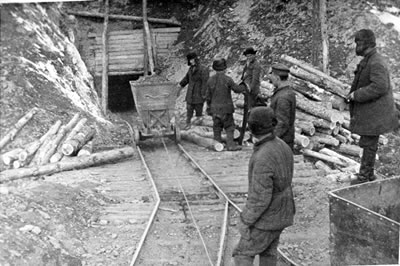

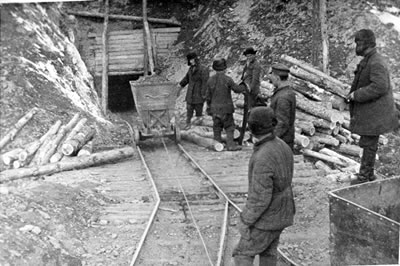

The Soviet Gulag Era in Pictures, 1927–1953

Photographs, several of Kolyma, collected by James Duncan

in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:1 (Spring 2006), pp. 58–71.

Work in the Gulag

from the Stalin's Gulag section of the Online Gulag Museum with a short description and images of Kolyma

Italian-American artist Thomas Sgovio (1916–1997) created a series of drawings and paintings, based on his life as a prisoner in the Soviet GulagShalamv Kolyma Tales

Private site of a former Polish prisoner, Stanislaw J. Kowalski.

at the Memorial website {{Regions of the world Historical regions in Russia History of the Russian Far East Geography of Gulag de:Kolyma#Goldgewinnung in Straflagern

Kolyma (russian: Колыма́, ) is a region located in the

Kolyma (russian: Колыма́, ) is a region located in the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admini ...

. It is bounded to the north by the East Siberian Sea

The East Siberian Sea ( rus, Восто́чно-Сиби́рское мо́ре, r=Vostochno-Sibirskoye more) is a marginal sea in the Arctic Ocean. It is located between the Arctic Cape to the north, the coast of Siberia to the south, the New Si ...

and the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceans. It spans an area of approximately and is known as the coldest of all the oceans. The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, a ...

, and by the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

to the south. The region gets its name from the Kolyma River

The Kolyma ( rus, Колыма, p=kəlɨˈma; sah, Халыма, translit=Khalyma) is a river in northeastern Siberia, whose basin covers parts of the Sakha Republic, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, and Magadan Oblast of Russia.

The Kolyma is frozen ...

and mountain system

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have arise ...

, parts of which were not accurately mapped by Russian surveyors until 1926. Today the region consists roughly of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug

Chukotka (russian: Чуко́тка), officially the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug,, ''Čukotkakèn avtonomnykèn okrug'', is the easternmost federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia. It is an autonomous okrug situated in the Russian ...

and the Magadan Oblast

Magadan Oblast ( rus, Магаданская область, r=Magadanskaya oblast, p=məgɐˈdanskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject (an oblast) of Russia. It is geographically located in the Far East region of the country, and is adminis ...

.

The area, part of which is within the Arctic Circle

The Arctic Circle is one of the two polar circles, and the most northerly of the five major circles of latitude as shown on maps of Earth. Its southern equivalent is the Antarctic Circle.

The Arctic Circle marks the southernmost latitude at w ...

, has a subarctic climate

The subarctic climate (also called subpolar climate, or boreal climate) is a climate with long, cold (often very cold) winters, and short, warm to cool summers. It is found on large landmasses, often away from the moderating effects of an ocean, ge ...

with very cold winters lasting up to six months of the year. Permafrost

Permafrost is ground that continuously remains below 0 °C (32 °F) for two or more years, located on land or under the ocean. Most common in the Northern Hemisphere, around 15% of the Northern Hemisphere or 11% of the global surface ...

and tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless moun ...

cover a large part of the region. Average winter temperatures range from (even lower in the interior), and average summer temperatures, from . There are rich reserves of gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European wikt:Reconstruction:Proto-Indo-European/h₂erǵ-, ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, whi ...

, tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn (from la, stannum) and atomic number 50. Tin is a silvery-coloured metal.

Tin is soft enough to be cut with little force and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, t ...

, tungsten

Tungsten, or wolfram, is a chemical element with the symbol W and atomic number 74. Tungsten is a rare metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively as compounds with other elements. It was identified as a new element in 1781 and first isolat ...

, mercury

Mercury commonly refers to:

* Mercury (planet), the nearest planet to the Sun

* Mercury (element), a metallic chemical element with the symbol Hg

* Mercury (mythology), a Roman god

Mercury or The Mercury may also refer to:

Companies

* Merc ...

, copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkis ...

, antimony

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient time ...

, coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

, oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

, and peat

Peat (), also known as turf (), is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, moors, or muskegs. The peatland ecosystem covers and is the most efficien ...

. Twenty-nine zones of possible oil and gas accumulation have been identified in the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

shelf. Total reserves are estimated at 3.5 billion tons of equivalent fuel, including 1.2 billion tons of oil and 1.5 billion m3 of gas.

The principal town Magadan

Magadan ( rus, Магадан, p=məɡɐˈdan) is a port town and the administrative center of Magadan Oblast, Russia, located on the Sea of Okhotsk in Nagayev Bay (within Taui Bay) and serving as a gateway to the Kolyma region.

History

Maga ...

has nearly 100,000 inhabitants and is the largest port in north-eastern Russia. It has a large fishing fleet and remains open year-round thanks to icebreakers. Magadan is served by the nearby Sokol Airport

Sokol Airport, formally Vladimir Vysotsky International Airport (russian: Аэропорт Сокол) is an airport in Sokol in Magadan Oblast, Russia. The airport is located 50 km (31 mi) north of the Magadan city center. The airpor ...

. There are many public and private farming enterprises. Gold mines, pasta and sausage factories, fishing companies, and a distillery form the city's industrial base.

Prehistory

During archaeological investigations of Paleolithic sites on the Angara, in 1936 the unique Stone Age site of Buret’ was discovered which yielded an anthropomorphic sculpture, skulls of rhinoceroses, and surface and semisubterranean dwellings. The houses were analogous, on one hand, to Paleolithic European houses and, on the other, to ethnographically studied houses of theEskimo

Eskimo () is an exonym used to refer to two closely related Indigenous peoples: the Inuit (including the Alaska Native Iñupiat, the Greenlandic Inuit, and the Canadian Inuit) and the Yupik peoples, Yupik (or Siberian Yupik, Yuit) of eastern Si ...

s, Chukchi and Koryaks.

The indigenous peoples of this region include the Evens

The Evens ( eve, эвэн; pl. , in Even and , in Russian; formerly called ''Lamuts'') are a people in Siberia and the Russian Far East. They live in regions of the Magadan Oblast and Kamchatka Krai and northern parts of Sakha east of the ...

, Koryaks

Koryaks () are an indigenous people of the Russian Far East, who live immediately north of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Kamchatka Krai and inhabit the coastlands of the Bering Sea. The cultural borders of the Koryaks include Tigilsk in the sou ...

, Yupiks

The Yupik (plural: Yupiit) (; russian: Юпикские народы) are a group of indigenous or aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Yup ...

, Chukchis

The Chukchi, or Chukchee ( ckt, Ԓыгъоравэтԓьэт, О'равэтԓьэт, ''Ḷygʺoravètḷʹèt, O'ravètḷʹèt''), are a Siberian indigenous people native to the Chukchi Peninsula, the shores of the Chukchi Sea and the Berin ...

, Orochs

Orochs (Russian ''О́рочи''), Orochons, or Orochis (self-designation: ''Nani'') are a people of Russia that speak the Oroch (''Orochon'') language of the Southern group of Tungusic languages. According to the 2002 census there were 686 Or ...

, Chuvans

Chuvans (russian: чуванцы) are one of the forty or so "Indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North, Siberia and the Far East" recognized by the Russian government. Most Chuvans today live within Chukotka Autonomous Okrug in the far n ...

and Itelmens

The Itelmens (Itelmen: Итәнмән, russian: Ительмены) are an indigenous ethnic group of the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia. The Itelmen language is distantly related to Chukchi and Koryak, forming the Chukotko-Kamchatkan language ...

, who traditionally lived from fishing along the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

coast or from reindeer herding in the River Kolyma valley.

History

UnderJoseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's rule, Kolyma became the most notorious region for the Gulag

The Gulag, an acronym for , , "chief administration of the camps". The original name given to the system of camps controlled by the GPU was the Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps (, )., name=, group= was the government agency in ...

labor camp

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (especi ...

s. Tens of thousands or more people died en route to the area or in the Kolyma's series of gold mining

Gold mining is the extraction of gold resources by mining. Historically, mining gold from alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. However, with the expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface ...

, road building, lumbering, and construction camps between 1932 and 1954. It was Kolyma's reputation that caused Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

, author of ''The Gulag Archipelago

''The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation'' (russian: Архипелаг ГУЛАГ, ''Arkhipelag GULAG'') is a three-volume non-fiction text written between 1958 and 1968 by Russian writer and Soviet dissident Aleksandr So ...

'', to characterize it as the "pole of cold and cruelty" in the Gulag system. The Mask of Sorrow

The Mask of Sorrow (russian: Маска скорби, ''Maska skorbi'') is a monument located on a hill above Magadan, Russia, commemorating the many prisoners who suffered and died in the Gulag prison camps in the Kolyma region of the Soviet U ...

monument in Magadan commemorates all those who died in the Kolyma forced-labour camps and the recently dedicated Church of the Nativity

The Church of the Nativity, or Basilica of the Nativity,; ar, كَنِيسَةُ ٱلْمَهْد; el, Βασιλική της Γεννήσεως; hy, Սուրբ Ծննդեան տաճար; la, Basilica Nativitatis is a basilica located in B ...

remembers the victims in its icons and Stations of the Camps.

Emergence of the Gulag camps

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

and platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Platinu ...

were discovered in the region in the early 20th century. During the time of the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

's industrialization (beginning with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

's first five-year plan

The first five-year plan (russian: I пятилетний план, ) of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was a list of economic goals, created by Communist Party General Secretary Joseph Stalin, based on his policy of socialism in ...

, 1928–1932) the need for capital to finance economic development was great. The abundant gold resources of the area seemed tailor-made to provide this capital. A government agency Dalstroy

Dalstroy (russian: Дальстро́й, ), also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Russian Far East, including the Magadan Region, Chukotka ...

(russian: Дальстрой, acronym for '' Far North Construction Trust'') was formed to organize the exploitation of the area. Prisoners were being drawn into the Soviet penal system in large numbers during the initial period of Kolyma's development, most notably from the so-called anti-Kulak campaign and the government's internal war to force collectivization

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member ...

on the USSR's peasantry. These prisoners formed a readily available workforce.

The initial efforts to develop the region began in 1932, with the building of the town of Magadan by

The initial efforts to develop the region began in 1932, with the building of the town of Magadan by forced labor

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, violence including death, or other forms of ex ...

. (Many projects in the USSR were already using forced labor, most notably the White Sea-Baltic Canal

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

.) After a gruelling train ride in unheated boxcars on the Trans-Siberian Railway

The Trans-Siberian Railway (TSR; , , ) connects European Russia to the Russian Far East. Spanning a length of over , it is the longest railway line in the world. It runs from the city of Moscow in the west to the city of Vladivostok in the ea ...

, prisoners were disembarked at one of several transit camps (such as Nakhodka

Nakhodka ( rus, Нахо́дка, p=nɐˈxotkə) is a port city in Primorsky Krai, Russia, located on the Trudny Peninsula jutting into the Nakhodka Bay of the Sea of Japan, about east of Vladivostok, the administrative center of the krai. Po ...

and later Vanino) and transported across the Sea of Okhotsk

The Sea of Okhotsk ( rus, Охо́тское мо́ре, Ohótskoye móre ; ja, オホーツク海, Ohōtsuku-kai) is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean. It is located between Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on the east, the Kuril Islands ...

to the natural harbor chosen for Magadan's construction. Conditions aboard the ships were harsh. According to a 1987 article in ''Time Magazine

''Time'' (stylized in all caps) is an American news magazine based in New York City. For nearly a century, it was published weekly, but starting in March 2020 it transitioned to every other week. It was first published in New York City on Mar ...

'': "During the 1930s the only way to reach Magadan was by ship from Khabarovsk

Khabarovsk ( rus, Хабaровск, a=Хабаровск.ogg, r=Habárovsk, p=xɐˈbarəfsk) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative centre of Khabarovsk Krai, Russia,Law #109 located from the China ...

, which created an island psychology and the term Gulag archipelago. Within the crowded prison ships thousands died during transportation. One survivor's memoir recounts that the prison ship SS Dzhurma

SS ''Djurma''This ship never had name ''Dzhurma'' during her life. The name ''Dzhuma'' could be mentioned after 1974 as per ''Protocol of Third Soviet-American Session regarding maritime shipping'' dated first part of 1974 about translation of Russ ...

was caught in the autumn ice in 1933 while trying to get to the mouth of the Kolyma River. When it reached port the following spring, it carried only crew and guards. All 12,000 prisoners were missing, left dead on the ice." It turns out that this incident, widely reported since it was first mentioned in a book published in 1947, could not have happened as the ship ''Dzhurma'' was not in Soviet hands until mid 1935.

In 1932 expeditions pushed their way into the interior of the Kolyma, embarking on the construction of the Kolyma Highway

The R504 Kolyma Highway (russian: Федеральная автомобильная дорога «Колыма», ''Federal'naya Avtomobil'naya Doroga «Kolyma»,'' "Federal Automobile Highway 'Kolyma'"), part of the M56 route, is a road throu ...

, which was to become known as the Road of Bones. Eventually, about 80 different camps dotted the region of the uninhabited taiga

Taiga (; rus, тайга́, p=tɐjˈɡa; relates to Mongolic and Turkic languages), generally referred to in North America as a boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruce ...

.

The original director of the Kolyma camps was Eduard Berzin

Eduard Petrovich Berzin (russian: Эдуа́рд Петро́вич Бе́рзин, lv, Eduards Bērziņš; 19 February 1894 – 1 August 1938) was a Soviet Union, Soviet soldier، Chekism, Chekist and NKVD officer that set up Dalstroy, which ...

, a Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

officer. Berzin was later removed (1937) and shot during the period of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

s in the USSR.

The Arctic camps

At the height of the Purges, around 1937,

At the height of the Purges, around 1937, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

's account imagines camp commander Naftaly Frenkel

Naftaly Aronovich Frenkel (russian: Нафталий Аронович Френкель; 1883 in Haifa – 1960 in Moscow) was a Soviet security officer and member of the Soviet secret police. Frenkel is best known for his role in the organisation ...

as establishing the new law of the Archipelago: "We have to squeeze everything out of a prisoner in the first three months—after that we don't need him anymore." But there is no documentary evidence of this beyond Solzhenitsyn's speculation.The system of hard labor and minimal or no food reduced most prisoners to helpless "goners" (''dokhodyaga'', in Russian). Conditions varied depending on the state of the country.

Many of the prisoners in Kolyma were academics or intellectuals. They included Mikhail Kravchuk

Mykhailo Pylypovych Kravchuk, also Krawtchouk ( uk, Миха́йло Пили́пович Кравчу́к) (September 27, 1892 – March 9, 1942), was a Soviet Ukrainian mathematician and the author of around 180 articles on mathematics.

He pr ...

(Krawtschuk), a Ukrainian mathematician who by the early 1930s had received considerable acclaim in the West. After a summary trial, apparently for reluctance to take part in the accusations of some of his colleagues, he was sent to Kolyma where he died in 1942. Hard work in the labor camp, harsh climate and meager food, poor health as well as accusations and abandonment by most of his colleagues, took their toll. Kravchuk perished in Magadan in Eastern Siberia, about 4,000 miles (6,000 km) from the place where he was born. Kravchuk's last article had appeared soon after his arrest in 1938. However, after this publication, Kravchuk's name was stricken from books and journals.

The prisoner population of Kolyma increased substantially in 1946 with the arrival of thousands of former Soviet POWs liberated by Western Allied forces or the Red Army at the close of World War II.Conquest, Robert, ''Kolyma: The Arctic Death Camps'', Viking Press, (1978), , pp. 228–229

Those judged guilty of collaboration with the enemy frequently received ten or twenty-five year prison sentences to the gulag, including Kolyma.

There were, however, some exceptions. Rumor suggested that Soviet agents seized Léon Theremin

Leon Theremin (born Lev Sergeyevich Termen rus, Лев Сергеевич Термéн, p=ˈlʲef sʲɪrˈɡʲejɪvʲɪtɕ tɨrˈmʲen; – 3 November 1993) was a Russian and Soviet inventor, most famous for his invention of the theremin, one o ...

, an inventor, in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and forced him to return to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

; he actually returned voluntarily. Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

had Theremin imprisoned at the Butyrka

Butyrskaya prison ( rus, Бутырская тюрьма, r= Butýrskaya tyurmá), usually known simply as Butyrka ( rus, Бутырка, p=bʊˈtɨrkə), is a prison in the Tverskoy District of central Moscow, Russia. In Imperial Russia i ...

in Moscow; he later came to work in the Kolyma gold mines. Although rumors of his execution circulated widely, Theremin was, in fact, put to work in a sharashka

A Special Design Bureau (, ''osoboje konstruktorskoe bûro''; ОКБ), commonly informally known as a ''sharashka'' (russian: шара́шка, ; sometimes ''sharaga'', ''sharazhka'') was any of several secret research and development laboratories ...

(a secret research-laboratory), together with other scientists and engineers, including aircraft designer Andrei Tupolev

Andrei Nikolayevich Tupolev (russian: Андрей Николаевич Туполев; – 23 December 1972) was a Russian Empire, Russian and later Soviet Union, Soviet aeronautical engineer known for his pioneering aircraft designs as Di ...

and rocket scientist Sergei Korolyov

Sergei Pavlovich Korolev (russian: Сергей Павлович Королёв, Sergey Pavlovich Korolyov, sʲɪrˈɡʲej ˈpavləvʲɪtɕ kərɐˈlʲɵf, Ru-Sergei Pavlovich Korolev.ogg; ukr, Сергій Павлович Корольов, ...

(also a Kolyma inmate). The Soviet Union rehabilitated Theremin in 1956.

The Kolyma camps switched to using (mostly) free labor after 1954, and in 1956 Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

ordered a general amnesty that freed many prisoners. Various estimates have put the Kolyma death-toll from 1930 to the mid-1950s between 250,000 and over a million people.

Dalstroy officials

Dalstroy

Dalstroy (russian: Дальстро́й, ), also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Russian Far East, including the Magadan Region, Chukotka ...

was the agency created to manage exploitation of the Kolyma area, based principally on the use of forced labour.

In the words of Azerbaijani prisoner Ayyub Baghirov, "The entire administration of the Dalstroy

Dalstroy (russian: Дальстро́й, ), also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Russian Far East, including the Magadan Region, Chukotka ...

—economic, administrative, physical and political—was in the hands of one person who was invested with many rights and privileges." The officials in charge of Dalstroy, i.e., the Kolyma Gulag camps were:

* Eduard Petrovich Berzin, 1932–1937

* Karp Aleksandrovich Pavlov, 1937–1939.

* Ivan Fedorovich Nikishev, 1940–1948.

* Ivan Grigorevich Petrenko, 1948–1950.

* I.L. Mitrakov, from 1950 until Dalstroy was taken over by the Ministry of Metallurgy on 18 March 1953.

Calendar of historical events

Calendar of events:

*1928–1929: Gold mines established in the Kolyma River region. Commencement of regular mining operations

*13 November 1931: Establishment of

Calendar of events:

*1928–1929: Gold mines established in the Kolyma River region. Commencement of regular mining operations

*13 November 1931: Establishment of Dalstroy

Dalstroy (russian: Дальстро́й, ), also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Russian Far East, including the Magadan Region, Chukotka ...

*4 February 1932: Eduard Berzin

Eduard Petrovich Berzin (russian: Эдуа́рд Петро́вич Бе́рзин, lv, Eduards Bērziņš; 19 February 1894 – 1 August 1938) was a Soviet Union, Soviet soldier، Chekism, Chekist and NKVD officer that set up Dalstroy, which ...

, Manager of Dalstroy, arrives with the first 10 prisoners.

*1934: The headcount increases to 30,000 inmates.

*1937: The number of inmates increases to over 70,000; 51,500 kg of gold mined

*June 1937: Stalin reprimands the Kolyma commandants for their undue leniency towards the inmates.

*December 1937: Berzin is charged with espionage and subsequently tried and shot in August 1938.

*4 March 1938: Dalstroy is put under the jurisdiction of NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

, USSR.

*December 1938: Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam ( rus, Осип Эмильевич Мандельштам, p=ˈosʲɪp ɨˈmʲilʲjɪvʲɪtɕ mənʲdʲɪlʲˈʂtam; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the Acm ...

, an eminent Russian poet, dies in a transit camp en route to Kolyma.

*1939: Number of inmates now 138,200.

*11 October 1939: Commandants Pavlov (Dalstroy

Dalstroy (russian: Дальстро́й, ), also known as Far North Construction Trust, was an organization set up in 1931 in order to manage road construction and the mining of gold in the Russian Far East, including the Magadan Region, Chukotka ...

) and (Sevvostlag

Sevvostlag (russian: Северо-восточные исправительно-трудовые лагеря, Севвостлаг, СВИТЛ, North-Eastern Corrective Labor Camps) was a system of forced labor camps set up to satisfy the work ...

) sacked from their posts. Garanin subsequently shot.

*1941: Headcount of inmates reaches 190,000. Also some 3,700 Dalstroy contract workers.

*23 May 1944: US Vice President Henry A. Wallace

Henry Agard Wallace (October 7, 1888 – November 18, 1965) was an American politician, journalist, farmer, and businessman who served as the 33rd vice president of the United States, the 11th U.S. Secretary of Agriculture, and the 10th U.S. S ...

arrives for a NKVD-hosted 25-day tour of Magadan, Kolyma, and the Russian Far East.

*October 1945: Camp for the Japanese prisoners of war is established in Magadan, to provide extra labour.

*1952: 199,726 inmates, the highest ever in the history of the Kolyma camps and Dalstroy.

*May 1952: According to commandant Mitrakov, Sevvoslag is dissolved, Dalstroy transformed into the General Board of Labour Camps

*March 1953: After Stalin's death, Dalstroy transferred to the Ministry of Metallurgy, camp units come under the jurisdiction of the Soviet Ministry of Justice.

*September 1953: Dalstroy camp units taken over by the newly established management board of the North-Eastern Corrective Labour Camps. Harsh camp regime gradually relaxed.

*1953–1956: Period of mass amnesties and the release of most political prisoners. Some camp closures begin.

*1957: Dalstroy liquidated. Many of the former prisoners continued to work in the mines with a modified status and a few new prisoners arrived, at least until the early 1970s.

Post-Dalstroy developments

The Chukot Autonomous Okrug site provides details of developments after the official closure of the camps. In 1953, theMagadan Oblast

Magadan Oblast ( rus, Магаданская область, r=Magadanskaya oblast, p=məgɐˈdanskəjə ˈobləsʲtʲ) is a federal subject (an oblast) of Russia. It is geographically located in the Far East region of the country, and is adminis ...

(or region) was established. Dalstroy was transferred to the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Metallurgy and later to the Ministry of Non-Ferrous Metallurgy.

Industrial and economic evolution

Industrial gold-mining started in 1958 leading to the development of mining settlements, industrial enterprises, power plants, hydro-electric dams, power transmission lines and improved roads. By the 1960s, the region's population exceeded 100,000. With the dissolution of Dalstroy, the Soviets adopted new labor policies. While the prison labor was still important, it mainly consisted of common criminals. New manpower was recruited from all Soviet nationalities on a voluntary basis, to make up for the sudden lack ofpolitical prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s. Young men and women were lured to the frontier land of Kolyma with the promise of high earnings and better living. But many decided to leave.

The region's prosperity suffered under Soviet liberal policies in the end of the 1980s and 1990s with a considerable reduction in population, apparently by 40% in Magadan. A U.S. report from the late 1990s gives details of the region's economic shortfall citing outdated equipment, bankruptcies of local companies and lack of central support. It does however report substantial investments from the United States and the governor's optimism for future prosperity based on revival of the mining industries.

Last political prisoners

Dalstroy and the camps did not close down completely. The Kolyma authority, which was reorganised in 1958/59 (31 December 1958), finally closed in 1968. However the mining activities did not stop. Indeed, government structures still exist today under the Ministry of Natural Resources. In some cases, the same individuals seem to have stayed on over the years under new management. There are indications that thepolitical prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s were gradually phased out over the years but it was only as a result of Boris Yeltsin

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin ( rus, Борис Николаевич Ельцин, p=bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈla(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn, a=Ru-Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin.ogg; 1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician wh ...

's far reaching reforms in the 1990s that the very last prisoners were released from Kolyma.

The Russian author Andrei Amalrik

Andrei Alekseevich Amalrik (russian: Андре́й Алексе́евич Ама́льрик, 12 May 1938, Moscow – 12 November 1980, Guadalajara, Castile-La Mancha, Spain), alternatively spelled ''Andrei'' or ''Andrey'', was a Russian writer ...

appears to have been one of the last high-profile political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although n ...

s to be sent to Kolyma. In 1970, he published two books: ''Will the Soviet Union Survive Until 1984?'' and ''Involuntary Journey to Siberia''. As a result, he was arrested for "defaming the Soviet state" in November 1970 and sentenced to hard labour, apparently in Kolyma, for what turned out to be a total of almost five years.

Accounts of the Kolyma Gulag camps

Varlam Shalamov

A detailed description of conditions in the camps is provided byVarlam Shalamov

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov (russian: Варла́м Ти́хонович Шала́мов; 18 June 1907 – 17 January 1982), baptized as Varlaam, was a Russian writer, journalist, poet and Gulag survivor. He spent much of the period from 1 ...

in his ''Kolyma Tales

''Kolyma Tales'' or ''Kolyma Stories'' (russian: Колымские рассказы, ''Kolymskiye rasskazy'') is the name given to six collections of short stories by Russian author Varlam Shalamov, about labour camp life in the Soviet Union. He ...

''. In ''Dry Rations'' he writes: "Each time they brought in the soup... it made us all want to cry. We were ready to cry for fear that the soup would be thin. And when a miracle occurred and the soup was thick we couldn’t believe it and ate it as slowly as possible. But even with thick soup in a warm stomach there remained a sucking pain; we’d been hungry for too long. All human emotions—love, friendship, envy, concern for one’s fellow man, compassion, longing for fame, honesty—had left us with the flesh that had melted from our bodies...."

Michael M. Solomon

During and after theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the region saw major influxes of Ukrainians

Ukrainians ( uk, Українці, Ukraintsi, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. They are the seventh-largest nation in Europe. The native language of the Ukrainians is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian. The majority ...

, Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

*Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin screenwr ...

, German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

ese, and Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

n prisoners. There is a particularly memorable account written by a Jewish Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n survivor, Michael M. Solomon, in his book ''Magadan'' (see Bibliography below) which gives us a vivid picture of both the transit camps leading to the Kolyma and the region itself. Hungarian George Bien

George may refer to:

People

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Washington, First President of the United States

* George W. Bush, 43rd President ...

, author of the ''Lost Years'', also recounts the horrors of Kolyma. His story has also led to a film.

Vladimir Nikolayevich Petrov

''Soviet Gold'', the first autobiographical book written byVladimir Nikolayevich Petrov

Vladimir Nikolayevich Petrov (1915 in Ekaterinodar oblast, Russian Empire – March 17, 1999 in Kensington, Maryland) was at various times an academic, philatelist, prisoner, forced laborer, political prisoner, adventurer, factory worker, chess ...

, is almost entirely a description of the author's life in Magadan and the Kolyma gold fields.

Ayyub Baghirov

In ''Bitter Days of Kolyma'', Ayyub Baghirov, an Azerbaijani accountant who was finally rehabilitated, provides details of his arrest, torture and sentencing to eight (finally to become 18) years imprisonment in a labour camp for refusing to incriminate a fellow official for financial irregularities. Describing the train journey to Siberia, he writes: "The terrible heat, the lack of fresh air, the unbearable overcrowded conditions all exhausted us. We were all half starved. Some of the elderly prisoners, who had become so weak and emaciated, died along the way. Their corpses were left abandoned alongside the railroad tracks."Brother Gene Thompson

A vivid account of the conditions in Kolyma is that of Brother Gene Thompson of Kiev's Faith Mission. He recounts how he met Vyacheslav Palman, a prisoner who survived because he knew how to grow cabbages. Palman spoke of how guards read out the names of those to be shot every evening. On one occasion a group of 169 men were shot and thrown into a pit. Their fully clothed bodies were found after the ice melted in 1998.Vadim Kozin

One of the most famous political prisoners in Kolyma wasVadim Kozin

Vadim Alekseyevich Kozin (russian: Вадим Алексеевич Козин; March 21, 1903 – December 19, 1994) was a Russian tenor, songwriter, and an openly homosexual man until 1934 when male homosexuality became a crime in USSR.

Vadim Al ...

, possibly Russia's most popular romantic tenor

A tenor is a type of classical music, classical male singing human voice, voice whose vocal range lies between the countertenor and baritone voice types. It is the highest male chest voice type. The tenor's vocal range extends up to C5. The lo ...

, who was sent to the camps in February 1945, apparently for refusing to write a song about Stalin. Although he was initially freed in 1950 and could return to his singing career, he was soon framed by his enemies on charges of homosexuality and sent back to the camps. Though released once again several years later, he was never officially rehabilitated and remained in exile in Magadan where he died in 1994. Speaking to journalists in 1982, he explained how he had been forced to tour the camps: "The Polit bureau formed brigades which would, under surveillance, go on tours of the concentration camps and perform for the prisoners and the guards, including those of the highest rank."

In 1993, while being interviewed by Theo Uittenbogaard

Theo Uittenbogaard (born Amstelveen, Nieuwer-Amstel, Netherlands, 1946 – 2022) was a Dutch radio & TV-producer, who worked for almost all nationwide public networks in The Netherlands since 1965. His training was on-the-job, since no school or a ...

for the TV documentary ''Gold – Lost in Siberia'he recalled how he was released from exile temporarily and flown into

Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crimea ...

for a few hours, because Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, unaware of Kozin's forced exile, had asked Stalin for the famous singer Vadim Kozin to perform, during a break in the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

, held February 4–11, 1945.

Nikolai Getman

Finally, Ukrainian prisonerNikolai Getman

Nikolai Ivanovich Getman or Mykola Ivanovich Hetman (russian: Николай Иванович Гетман, uk, Микола Іванович Гетьман), an artist, was born in 1917 in Kharkiv, Ukraine, and died at his home in Orel, Russia ...

who spent the years 1945–1953 in Kolyma, records his testimony in pictures rather than words. But he does have a plea: "Some may say that the Gulag is a forgotten part of history and that we do not need to be reminded. But I have witnessed monstrous crimes. It is not too late to talk about them and reveal them. It is essential to do so. Some have expressed fear on seeing some of my paintings that I might end up in Kolyma again—this time for good. But the people must be reminded... of one of the harshest acts of political repression in the Soviet Union. My paintings may help achieve this." The Jamestown Foundation provides access to all 50 of Getman's paintings together with explanations of their significance.

Estimating the number of victims

The amount of hard evidence in regard to Kolyma is extremely limited. Unfortunately, no reliable archives exist about the total number of victims ofStalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

; all numbers are estimates. In his book, ''Stalin'' (1996), Edvard Radzinsky

Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky (russian: Э́двард Станисла́вович Радзи́нский) (born September 23, 1936) is a Russian playwright, television personality, screenwriter, and the author of more than forty popular history ...

explains how Stalin, while systematically destroying his comrades-in-arms "at once obliterated every trace of them in history. He personally directed the constant and relentless purging of the archives." That practice continued to exist after the death of the dictator.

In an account of a visit to Magadan by Harry Wu

Harry Wu (; February 8, 1937 – April 26, 2016) was a Chinese-American human rights activist. Wu spent 19 years in Chinese labor camps, and he became a resident and citizen of the United States. In 1992, he founded the Laogai Research Foun ...

in 1999, there is a reference to the efforts of Alexander Biryukov, a Magadan lawyer to document the terror. He is said to have compiled a book listing every one of the 11,000 people documented to have been shot in Kolyma camps by the state security organ, the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

. Biryukov, whose father was in the Gulag at the time he was born, has begun researching the location of graves. He believed some of the bodies were still partially preserved in the permafrost.

It is therefore impossible to provide final figures on the number of victims who died in Kolyma. Robert Conquest, author of ''The Great Terror'', now admits that his original estimate of three million victims was far too high. In his article ''Death Tolls for the Man-made Megadeaths of the 20th Century'', Matthew White estimates the number of those who died at 500,000. In ''Stalin's Slave Ships'', Martin Bollinger undertakes a careful analysis of the number of prisoners who could have been transported by ship to Magadan between 1932 and 1953 (some 900,000) and the probable number of deaths each year (averaging 27%). This produces figures significantly below earlier estimates but, as the author emphasizes, his calculations are by no means definitive. In addition to the number of deaths, the dreadful conditions of the camps and the hardships experienced by the prisoners over the years need to be taken into account. In his review of Bollinger's book, Norman Polmar

Norman Polmar is a prominent author specializing in the naval, aviation, and intelligence areas.

He has led major projects for the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Navy, and foreign governments. His professional expertise has served three ...

refers to 130,000 victims who died at Kolyma. As Bollinger reports in his book, the 3,000,000 estimate originated with the CIA in the 1950s and appears to be a flawed estimate. This number is also estimated by the last survivors.

Anne Applebaum

Anne Elizabeth Applebaum (born July 25, 1964) is an American journalist and historian. She has written extensively about the history of Communism and the development of civil society in Central and Eastern Europe.

She has worked at ''The Econo ...

, 2004 Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

winner for her book ''Gulag: A History'', carried out an extensive investigation of the gulags. In a lecture in 2003, she explained that it's extremely difficult not only to document the facts given the extent of the cover-up but to bring the truth home.Heritage.org (16 October 2003). Retrieved on 2016-12-14.

Ecology

Thisecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of l ...

encompasses the drainages of Arctic rivers from the Indigirka River

The Indigirka ( rus, Индиги́рка, r=; sah, Индигиир, translit=Indigiir) is a river in the Sakha Republic in Russia between the Yana to the west and the Kolyma to the east. It is long. The area of its basin is .

History

The is ...

eastward to Chaunskaya Guba Bay. In the west, the Indigirka River

The Indigirka ( rus, Индиги́рка, r=; sah, Индигиир, translit=Indigiir) is a river in the Sakha Republic in Russia between the Yana to the west and the Kolyma to the east. It is long. The area of its basin is .

History

The is ...

drainage is separated from the Khroma River

The Khroma (russian: Хрома) is a river in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia) of the Russian Federation. It is long, and has a drainage basin of .

Course

The source of the Khroma is at the confluence of the Tamteken and the Nemalak-Arangas, flowin ...

and Yana rivers by the spurs of the Polousnyy Kryazh Range and the Chersky Range

The Chersky Range (, ) is a chain of mountains in northeastern Siberia between the Yana River and the Indigirka River. Administratively the area of the range belongs to the Sakha Republic, although a small section in the east is within Magadan O ...

.

Paleoecology

During thePleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

the ecology of this part of Beringia

Beringia is defined today as the land and maritime area bounded on the west by the Lena River in Russia; on the east by the Mackenzie River in Canada; on the north by 72 degrees north latitude in the Chukchi Sea; and on the south by the tip ...

was quite different from modern times, with the extinct Wooly mammoth

Wool is the textile fibre obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have properties similar to animal wool.

As an ...

and the wooly rhinoceros

The woolly rhinoceros (''Coelodonta antiquitatis'') is an extinct species of rhinoceros that was common throughout Europe and Asia during the Pleistocene Epoch (geology), epoch and survived until the end of the last glacial period. The woolly rhi ...

being present.

The polar bear

The polar bear (''Ursus maritimus'') is a hypercarnivorous bear whose native range lies largely within the Arctic Circle, encompassing the Arctic Ocean, its surrounding seas and surrounding land masses. It is the largest extant bear specie ...

most likely evolved here.

See also

* *References

Further reading

* *External links

The Soviet Gulag Era in Pictures, 1927–1953

Photographs, several of Kolyma, collected by James Duncan

in Azerbaijan International, Vol. 14:1 (Spring 2006), pp. 58–71.

Work in the Gulag

from the Stalin's Gulag section of the Online Gulag Museum with a short description and images of Kolyma

Italian-American artist Thomas Sgovio (1916–1997) created a series of drawings and paintings, based on his life as a prisoner in the Soviet Gulag

Private site of a former Polish prisoner, Stanislaw J. Kowalski.

at the Memorial website {{Regions of the world Historical regions in Russia History of the Russian Far East Geography of Gulag de:Kolyma#Goldgewinnung in Straflagern