The Xhosa Wars (also known as the Cape Frontier Wars or the Kaffir Wars) were a series of nine wars (from 1779 to 1879) between the

Xhosa Kingdom and the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

as well as

Trekboers

The Trekboers ( af, Trekboere) were nomadic pastoralists descended from European settlers on the frontiers of the Dutch Cape Colony in Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the C ...

in what is now the

Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape is one of the provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, but its two largest cities are East London and Gqeberha.

The second largest province in the country (at 168,966 km2) after Northern Cape, it was formed in ...

in South Africa. These events were the longest-running military action in the history of

European colonialism in Africa.

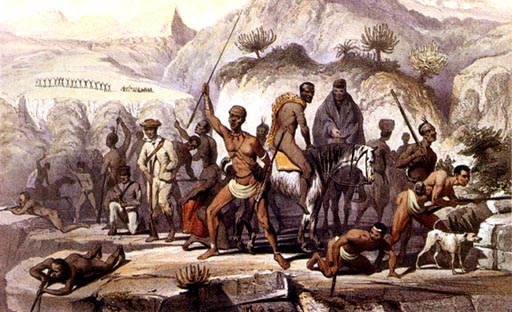

The reality of the conflicts between the Europeans and Xhosa involves a balance of tension. At times, tensions existed between the various Europeans in the Cape region, tensions between Empire administration and colonial governments, and tensions within the Xhosa Kingdom, e.g. chiefs rivalling each other, which usually led to Europeans taking advantage of the situation to meddle in Xhosa politics. A perfect example of this is the case of chief Ngqika and his uncle, chief Ndlambe.

Background

The first

European colonial settlement in modern-day

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

was a small supply station established by the

Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( nl, Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, the VOC) was a chartered company established on the 20th March 1602 by the States General of the Netherlands amalgamating existing companies into the first joint-stock ...

in 1652 at present-day

Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

as a place for their

merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

s to resupply ''en route'' to and from the

East Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around t ...

and

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

. Quickly expanding as a result of increasing numbers of

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

,

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

,

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

and

Irish immigrants

The Irish diaspora ( ga, Diaspóra na nGael) refers to ethnic Irish people and their descendants who live outside the island of Ireland.

The phenomenon of migration from Ireland is recorded since the Early Middle Ages,Flechner and Meeder, The ...

, the supply station soon expanded into a burgeoning

settler colony

Settler colonialism is a structure that perpetuates the elimination of Indigenous people and cultures to replace them with a settler society. Some, but not all, scholars argue that settler colonialism is inherently genocidal. It may be enacted ...

. Colonial expansion from the Cape into the valleys led to the

Khoikhoi–Dutch Wars

The Khoikhoi–Dutch Wars were a series of conflicts that took place in the last half of the 17th century in what was known then as the Cape of Good Hope (today it refers to a smaller geographic spot), in the area of present-day Cape Town, Sou ...

between encroaching ''

trekboers

The Trekboers ( af, Trekboere) were nomadic pastoralists descended from European settlers on the frontiers of the Dutch Cape Colony in Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the C ...

'' and the

Khoekhoe

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also '' Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 May 2018. Citing G. S. ...

.

By the second half of the 18th century, European colonists gradually expanded eastward up the coast and encountered the

Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

in the region of the

Great Fish River

The Great Fish River (called ''great'' to distinguish it from the Namibian Fish River) ( af, Groot-Visrivier) is a river running through the South African province of the Eastern Cape. The coastal area between Port Elizabeth and the Fish Riv ...

. The Xhosa were already established in the area and herded cattle, which led to tensions between them and the colonists; these tensions were the primary reason for the Cape Frontier Wars. The Dutch East India Company had demarcated the Great Fish River as the eastern boundary of the colony in 1779, though this was ignored by many settlers, leading to the First Cape Frontier War breaking out.

[2011. Conquest of the Eastern Cape 1779-1878. SA History. Accessed 13 March.]

/ref>

Early conflicts

First war (1779–1781)

The First Frontier War broke out in 1779 between Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

frontiersmen and the Xhosa. In December 1779, an armed clash occurred, resulting from allegations of cattle theft by Xhosa people. In November 1780, the Cape governor, Baron van Plettenberg declared that the eastern border of the Cape colony was the entire length of the Great Fish river

The Great Fish River (called ''great'' to distinguish it from the Namibian Fish River) ( af, Groot-Visrivier) is a river running through the South African province of the Eastern Cape. The coastal area between Port Elizabeth and the Fish Riv ...

despite that many Xhosa polities were already established west of the river, and no negotiations revolving around this decision were made with them before so.

Second war (1789–1793)

The second war involved a larger territory. It started when the Gqunukhwebe Ama Gqunukhwebe is a chiefdom of the Xhosa Nation that was created under the reign of King Tshiwo (1670–1702) of amaXhosa who was a grandfather to Gcaleka and Rharhabe. It consisted mostly of the Khoi chiefdoms (Gonaqua, Hoengeniqua, Inqua and ...

clans of the Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

started to penetrate back into the Zuurveld, a district between the Great Fish and the Sundays River

The !Khukaǁgamma or Sundaysriver ( af, Sondagsrivier) is a river in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. It is said to be the fastest flowing river in the country. The Inqua Khoi people, who historically were the wealthiest group in Sou ...

s. Some frontiersmen, under Barend Lindeque, allied themselves with Ndlambe (regent of the Western Xhosas) to repel the Gqunukhwebe. Panic ensued and farms were abandoned.[

]

Third war (1799–1803)

The third war started in January 1799 with a Xhosa rebellion that General T. P. Vandeleur crushed. Discontented Khoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also ''Hottentot (racial term), Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 ...

then revolted, joined with the Xhosa in the Zuurveld, and started attacking, raiding farms occupied by European and Dutch settlers, reaching Oudtshoorn by July 1799. Commandos from Graaf-Reinet and Swellendam then started fighting in a string of clashes. The government then made peace with the Xhosa and allowed them to stay in Zuurveld. In 1801, another Graaff-Reinet rebellion started forcing more Khoi desertions and farm abandonments. The commandos could achieve no result, so in February 1803 a peace was arranged, leaving the Xhosas still in the big Zuurveld.[

]

Start of British involvement

Fourth War (1811–1812)

The Fourth War was the first experienced under British rule. The Zuurveld acted as a buffer zone between the Cape Colony and Xhosa territory, empty of the Boers and British to the east and the Xhosa to the west. In 1811, the Xhosa occupied the area, and flashpoint conflicts with encroaching settlers followed. An expeditionary force under the command of Colonel John Graham drove the Xhosa back beyond the Fish River in an effort that the first Governor of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

, Lieutenant-General John Cradock

John Cradock (alias Craddock) (c. 1708 - 10 December 1778) was an English churchman, Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin from 1772.

Background and education

Born at Donington, Shropshire, England about 1708, he was the eldest son of the Reve ...

, characterized as involving no more bloodshed "than was necessary to impress on the minds of these savages a proper degree of terror and respect". About four thousand 1820 Settlers

The 1820 Settlers were several groups of British colonists from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales, settled by the government of the United Kingdom and the Cape Colony authorities in the Eastern Cape of South Africa in 1820.

Origins

After th ...

subsequently (after the fifth war) settled on the Fish River. "Graham's Town" arose on the site of Colonel Graham's headquarters; in time this became Grahamstown

Makhanda, also known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 140,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Port Elizabeth and southwest of East London, Eastern Cape, East London. Makhanda is the lar ...

.

Fifth War (1818–1819)

The fifth frontier war, also known as the "War of Nxele", initially developed from an 1817 judgment by the Cape Colony government about stolen cattle and their restitution by the Xhosa. An issue of ducks and geese overcrowding the area brought on a civil war between the Ngqika

The Ngqika people are a Xhosa people, Xhosa monarchy who lived west of the Great Kei River in what is today the Eastern Cape of South Africa. They were first ruled by Rharhabe, Rarabe kaPhalo who died with his son Mlawu, who was destined for chieft ...

(royal clan of the Rharhabe Xhosa) and the Gcaleka

The Gcaleka House is the Great house of the Xhosa Kingdom in what is now the Eastern Cape. Its royal palace is in the former Transkei and its counterpart in the former Ciskei is the Rharhabe, which is the right hand house of Phalo.

The Gcaleka H ...

Xhosa (those that remained in their homeland). A Cape Colony-Ngqika defence treaty legally required military assistance to the Ngqika request (1818).

The Xhosa prophet Nxele

Makhanda , also spelled Makana and also known as ''Nxele'' ("the left-handed"), ( – 25 December 1819) was a Xhosa witch doctor. He served as a top advisor to Chief Ndlambe. During the Xhosa Wars, on the 22nd of April, 1819, he instigated an ...

(also known as Makhanda) emerged at this time and promised "to turn bullets into water". Under the command of Mdushane, AmaNdlambe

The AmaNdlambe or the Ndlambe is a Xhosa chiefdom located in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Founded by Chief Ndlambe, son of Chief Rharhabe and grandson of King Phalo, Ndlambe's advisors and strong army were known as the 'AmaNdlambe'. Chief Ndla ...

's son, Nxele led a 10,000 Xhosa force attack (22 April 1819) on Grahamstown

Makhanda, also known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 140,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Port Elizabeth and southwest of East London, Eastern Cape, East London. Makhanda is the lar ...

, which was held by 350 troops. A Khoikhoi

Khoekhoen (singular Khoekhoe) (or Khoikhoi in the former orthography; formerly also ''Hottentot (racial term), Hottentots''"Hottentot, n. and adj." ''OED Online'', Oxford University Press, March 2018, www.oed.com/view/Entry/88829. Accessed 13 ...

group led by Jan Boesak enabled the garrison to repulse Nxele, who suffered the loss of 1,000 Xhosa. Nxele was eventually captured and imprisoned on Robben Island

Robben Island ( af, Robbeneiland) is an island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, north of Cape Town, South Africa. It takes its name from the Dutch word for seals (''robben''), hence the Dutch/Afrik ...

.

The British colonial authorities pushed the Xhosa further east beyond the Fish River to the Keiskamma River

The Keiskamma River ( af, Keiskammarivier) is a river in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. The river flows into the Indian Ocean in the Keiskamma Estuary, located by Hamburg Nature Reserve, near Hamburg, midway between East London and Po ...

. The resulting empty territory was designated as a buffer zone for loyal Africans' settlements, but was declared to be off limits for either side's military occupation. It came to be known as the "Ceded Territories". The Albany district was established in 1820, on the Cape's side of the Fish River, and was populated with some 5,000 settlers. The Grahamstown battle site continues to be called "Egazini" ("Place of Blood"), and a monument was erected there for the fallen Xhosa in 2001.

Battle of Amalinde

During the Fifth Frontier War in 1818, after a two-decade long conflict, King Ngqika

The Ngqika people are a Xhosa people, Xhosa monarchy who lived west of the Great Kei River in what is today the Eastern Cape of South Africa. They were first ruled by Rharhabe, Rarabe kaPhalo who died with his son Mlawu, who was destined for chieft ...

ka Mlawu and his uncle Ndlambe’s people clashed again in a battle called the Battle of Amalinde over several issues, including land ownership. The king appointed his eldest son Maqoma (despite him lacking experience in battle) and the renowned Jingqi to lead the fight that lasted from midday to the evening. Ngqika was defeated, losing about 500 men during what is considered by some as one of the most historical battles in Southern Africa.

Sixth war (1834–1836)

The earlier Xhosa Wars did not quell British-Xhosa tension in the Cape's eastern border at the Keiskamma River. Insecurity persisted because the Xhosa remained expelled from territory (especially the so-called "Ceded Territories") that was then settled by Europeans and other African peoples. They were also subjected to territorial expansions from other Africans that were themselves under pressure from the expanding

The earlier Xhosa Wars did not quell British-Xhosa tension in the Cape's eastern border at the Keiskamma River. Insecurity persisted because the Xhosa remained expelled from territory (especially the so-called "Ceded Territories") that was then settled by Europeans and other African peoples. They were also subjected to territorial expansions from other Africans that were themselves under pressure from the expanding Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom (, ), sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or the Kingdom of Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa. During the 1810s, Shaka established a modern standing army that consolidated rival clans and built a large following ...

. Nevertheless, the frontier region was seeing increasing amounts of admixture between Europeans, Khoikhoi, and Xhosa living and trading throughout the frontier region. The vacillation by the Cape Government's policy towards the return of the Xhosa to areas they previously inhabited did not dissipate Xhosa frustration toward the inability to provide for themselves, and they thus resorted to frontier cattle-raiding.

Outbreak

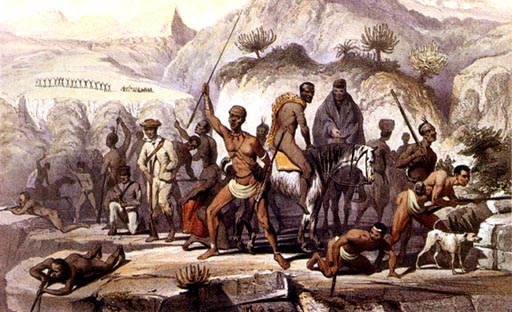

Cape responses to the Xhosa cattle raids varied, but in some cases were drastic and violent.On 11 December 1834, a Cape government commando party killed a chief of high rank, incensing the Xhosa: an army of 10,000 men, led by Maqoma

Jongumsobomvu Maqoma (1798–1873) was a Xhosa chief and a commander of the Xhosa forces during the Cape Frontier Wars. Born in the Right Hand House of the Xhosa Kingdom, he was the older brother of Chief Mgolombane Sandile and nephew to King Hin ...

, a brother of the chief who had been killed, swept across the frontier into the Cape Colony, pillaged and burned the homesteads, and killed all who resisted. Among the worst sufferers was a colony of freed Khoikhoi who, in 1829, had been settled in the Kat River Valley by the British authorities. Refugees from the farms and villages took to the safety of Grahamstown, where women and children found refuge in the church.

British campaign

The response was swift and multifaceted. Boer commando

The Boer Commandos or "Kommandos" were volunteer military units of guerilla militia organized by the Boer people of South Africa. From this came the term "commando" into the English language during the Second Boer War of 1899-1902 as per Costica ...

s mobilised under Piet Retief

Pieter Mauritz Retief (12 November 1780 – 6 February 1838) was a ''Voortrekker'' leader. Settling in 1814 in the frontier region of the Cape Colony, he assumed command of punitive expeditions in response to raiding parties from the adjacent ...

and inflicted a defeat on the Xhosa in the Winterberg Mountains in the north. Burgher and Khoi commandos also mobilised, and British Imperial troops arrived via Algoa Bay

Algoa Bay is a maritime bay in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. It is located in the east coast, east of the Cape of Good Hope.

Algoa Bay is bounded in the west by Cape Recife and in the east by Cape Padrone. The bay is up to deep. The harbour c ...

.

The British governor, Sir Benjamin d'Urban, mustered the combined forces under Colonel Sir Harry Smith, who reached Grahamstown on 6 January 1835, six days after news of the attack had reached Cape Town. It was from Grahamstown that the retaliatory campaign was launched and directed.

The campaign inflicted a string of defeats on the Xhosa, such as at Trompetter's Drift on the Fish River, and most of the Xhosa chiefs surrendered. However, the two primary Xhosa leaders, Maqoma and Tyali, retreated to the fastnesses of the Amatola Mountains

Amatola, Amatole or Amathole are a range of densely forested mountains, situated in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The word ''Amathole'' means ‘calves’ in Xhosa, and Amathole District Municipality, which lies to the south, is named ...

.

The treaty

British governor Sir Benjamin d'Urban believed that Hintsa ka Khawuta

Hintsa ka Khawuta (1780 – 12 May 1835), also known as ''Great'' or ''King Hintsa'', was the king of the Xhosa Kingdom, founded by his great ancestor, King Tshawe. He ruled from 1820 until his death in 1835. The Xhosa Kingdom, at its peak, durin ...

, King of the amaXhosa

The Xhosa people, or Xhosa-speaking people (; ) are African people who are direct kinsmen of Tswana people, Sotho people and Twa people, yet are narrowly sub grouped by European as Nguni ethnic group whose traditional homeland is primarily the ...

, commanded authority over all of the Xhosa tribes and therefore held him responsible for the initial attack on the Cape Colony, and for the looted cattle. D'Urban

came to the frontier in May 1835, and led a large force across the Kei river

The Great Kei River is a river in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is formed by the confluence of the Black Kei River and White Kei River, northeast of Cathcart. It flows for and ends in the Great Kei Estuary at the Indian Ocean wi ...

to confront Hintsa at his Great Place and dictate terms to him.

The terms stated that all the country from the Cape's prior frontier, the Keiskamma River, as far as the Great Kei River, was annexed as the British "Queen Adelaide Province", and its inhabitants declared British subjects. A site for the seat of the province's government was selected and named King William’s Town

Qonce, formerly known as King William's Town, is a city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa along the banks of the Buffalo River. The city is about northwest of the Indian Ocean port of East London. Qonce, with a population of around ...

. The new province was declared to be for the settlement of loyal tribes, rebel tribes who replaced their leadership, and the Fengu

The ''amaMfengu'' (in the Xhosa language ''Mfengu'', plural ''amafengu'') was a reference of Xhosa clans whose ancestors were refugees that fled from the Mfecane in the early 19th century to seek land and protection from the Xhosa and have sinc ...

(known to the Europeans as the "Fingo people"), who had recently arrived fleeing from the Zulu armies and had been living under Xhosa subjection. Magistrates were appointed to administer the territory in the hope that they would gradually, with the help of missionaries, undermine tribal authority. Hostilities finally died down on 17 September 1836, after having continued for nine months.

The killing of King Hintsa

Hintsa was the King of the Xhosa Kingdom and was recognised as Paramount by all Xhosa-speaking tribes and states in the Cape; his death proved to be an enduring memory in the collective imagination of the Xhosa nation. Originally assured of his personal safety during the treaty negotiations, Hintsa rapidly found himself held hostage and pressured with massive demands for cattle "restitution". Other sources say he offered himself as a hostage until the indemnity was paid and even suggested that he accompany Colonel Smith in collecting Xhosa cattle. He attempted to escape at the Nqabarha River but was pursued, pulled off his horse, and immobilized with shots through the back and the leg. Immediately, a soldier named George Southey (brother of colonial administrator Sir Richard Southey) came up behind Hintsa and shot him in the back of the head; furthermore, Hintsa's ears were cut off after his death. Other sources say his horse bolted and Harry Smith tried to shoot the fleeing man but both his pistols misfired. Giving chase, he caught hold of Hintsa and dragged him heavily to the ground. Hintsa was still full of fight. "He was jabbing at me furiously with his assegai," Colonel Smith recalled in his autobiography, and the king succeeded in breaking away to find cover in a nearby stream bed. There, while pleading for mercy, the top of his skull was blown off by one of Smith's officers; his corpse was subsequently badly mutilated by Smith and his men. These actions shocked the government in London, which condemned and repudiated Governor D’Urban. Hintsa's murder angered the Xhosa for decades thereafter.

Aftermath

By the end of the sixth war, 7,000 people of all races were left homeless.

The settlement of the Fengu in the annexed territory had far-reaching consequences. This wandering peoples claimed to be escaping oppression at the hands of the Gcaleka and, in return for the land they were given by the Cape, they became the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

's formidable allies. They swiftly acquired firearms and formed mounted commandos for the defense of their new land. In the following wars, they fought alongside the Cape Colony as invaluable allies, not as subordinates, and won considerable renown and respect for their martial ability.

The conflict was the catalyst for Piet Retief

Pieter Mauritz Retief (12 November 1780 – 6 February 1838) was a ''Voortrekker'' leader. Settling in 1814 in the frontier region of the Cape Colony, he assumed command of punitive expeditions in response to raiding parties from the adjacent ...

's manifesto and the Great Trek

The Great Trek ( af, Die Groot Trek; nl, De Grote Trek) was a Northward migration of Dutch-speaking settlers who travelled by wagon trains from the Cape Colony into the interior of modern South Africa from 1836 onwards, seeking to live beyon ...

. In total, 40 farmers (Boers) were killed and 416 farmhouses were burnt down. In addition, 5,700 horses, 115,000 head of cattle, and 162,000 sheep were plundered by Xhosa tribespeople. In retaliation, sixty thousand Xhosa cattle were taken or retaken by colonists

A settler is a person who has migrated to an area and established a permanent residence there, often to colonize the area.

A settler who migrates to an area previously uninhabited or sparsely inhabited may be described as a pioneer.

Settle ...

.

The British minister of colonies, Lord Glenelg

Charles Grant, 1st Baron Glenelg PC FRS (26 October 1778 – 23 April 1866) was a Scottish politician and colonial administrator who served as Secretary of State for War and the Colonies

Background and education

Grant was born in Kidderpore, ...

, repudiated d'Urban's actions and accused the Boer retaliation against cattle raiders as being what instigated the conflict. As a result, the Boer community lost faith in the British justice system and often took the law into their own hands when cattle rustlers were caught.

The territorial expansion and creation of "Queen Adelaide Province" was also condemned by London as being uneconomical and unjust. The province was disannexed in December 1836, the Cape's border was re-established at the Keiskamma river, and new treaties were made with the chiefs responsible for order beyond the Fish River.

Interlude: Stockenström's treaty system

In the aftermath of the previous frontier war, the new lieutenant-governor of the Eastern Province,

In the aftermath of the previous frontier war, the new lieutenant-governor of the Eastern Province, Andries Stockenström

Sir Andries Stockenström, 1st Baronet, (6 July 1792 in Cape Town – 16 March 1864 in London) was lieutenant governor of British Kaffraria from 13 September 1836 to 9 August 1838.

His efforts in restraining colonists from moving into Xhosa ...

, instituted a completely new border policy. Stockenström, who professed considerable respect for the Xhosa, developed a system of formal treaties to guard the border and return any stolen cattle from either side (cattle raiding was a regular grievance). Diplomatic agents were exchanged between the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

and the Xhosa Chiefs as reliable "ambassadors", and colonial expansion into Xhosa land was forbidden. Land annexed from the Xhosa in the previous war was also returned and the displaced Xhosa moved back into this land, assuaging overpopulation in the Xhosa territories.

In the framework of this new system, the frontier settled and saw nearly a decade of peace. The Xhosa chiefs generally honoured Stockenström's treaty and returned any cattle that their people had raided. On the Cape side, Stockenström, who saw the major problem as being the land management of the colonists, used his influence to rein in the frontier settlers and prevent any expansion onto Xhosa land. A level of trust also began to develop, and the Xhosa chiefs came to hold Stockenström in exceptionally high regard as a man who, although he had defeated the Xhosa armies on multiple occasions, nonetheless treated them as diplomatic equals.

The treaty system began to unravel as the settlers gained a determined leader and spokesman in the form of Robert Godlonton

Robert Godlonton (1794–1884) ("Moral Bob") was an influential politician of the Cape Colony. He was an 1820 Settler, who developed the press of the Eastern Cape and led the Eastern Cape separatist movement as a representative in the Cape's ...

, who led a large colonist movement to dismantle Stockenström's system and allow seizure of Xhosa lands. As one settler ominously declared of the Xhosa territory: ''"The appearance of the country is very fine, it will make excellent sheep farms."'' Godlonton also used his considerable influence in the religious institutions of the Cape to drive his opinions, declaring that: ''"the British race was selected by God himself to colonize Kaffraria"''.

In the face of massive pressure and ruinous lawsuits, Stockenström was eventually dismissed and the new British governor, Maitland, abrogated the treaties.

Seventh war (1846–1847)

The Seventh Xhosa War is often referred to as the "War of the Axe" or the "Amatola War". On the colonial side, two main groups were involved: columns of imperial British troops sent from London, and local mixed-race "Burgher forces", which were mainly Khoi, Fengu,

The Seventh Xhosa War is often referred to as the "War of the Axe" or the "Amatola War". On the colonial side, two main groups were involved: columns of imperial British troops sent from London, and local mixed-race "Burgher forces", which were mainly Khoi, Fengu, British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

settlers and Boer commando

The Boer Commandos or "Kommandos" were volunteer military units of guerilla militia organized by the Boer people of South Africa. From this came the term "commando" into the English language during the Second Boer War of 1899-1902 as per Costica ...

s, led by their commander-in-chief, Andries Stockenström

Sir Andries Stockenström, 1st Baronet, (6 July 1792 in Cape Town – 16 March 1864 in London) was lieutenant governor of British Kaffraria from 13 September 1836 to 9 August 1838.

His efforts in restraining colonists from moving into Xhosa ...

. Relations between the British Imperial troops and the local commandos broke down completely during the war.

On the Xhosa side, the Ngqika

The Ngqika people are a Xhosa people, Xhosa monarchy who lived west of the Great Kei River in what is today the Eastern Cape of South Africa. They were first ruled by Rharhabe, Rarabe kaPhalo who died with his son Mlawu, who was destined for chieft ...

(known to the Europeans as the "Gaika") were the chief tribe engaged in the war, assisted by portions of the Ndlambe and the Thembu

The Thembu Kingdom (''abaThembu ababhuzu-bhuzu, abanisi bemvula ilanga libalele'') was a Xhosa-state in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

According to Xhosa oral tradition, the AbaThembu migrated along the east coast of Southern Africa ...

. The Xhosa forces were greater in number, and some of them had by this time replaced their traditional weapons with firearms. Both sides engaged in the widespread use of scorched earth tactics

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

. The conflict was also marked by widespread massacres of Xhosa and Thembu people by both British settlers and Fengu auxiliaries, many of them justified as revenge for earlier Xhosa attacks on British settlements and for the Xhosa's oppression and treatment of the Fengu people as second class citizens following their refugee exodus into the Xhosa Kingdom from the violence of the Mfecane.

King Mgolombane Sandile

Mgolombane Sandile (1820–1878) was a ruler of the Right Hand House of the Xhosa Kingdom. A dynamic leader, he led the Xhosa armies in several of the Xhosa-British Wars.

Having recently been equipped with modern fire-arms, Sandile's forces succ ...

led the Ngqika people in the Seventh Frontier War (1846–47), Eighth Frontier War (1850–53) and the Ninth Frontier War (1877–78), in which he was killed. These clashes marked the beginning of the use of firearms by Xhosa armies, scoring many victories for King Sandile, gaining him a reputation as a Xhosa hero and mighty warrior.[ 008. Nienaber WC, Steyn M and Hutten L.The grave of King Mgolombane Sandile Ngqika: Revisiting the legend. South African Archaeological Bulletin. Accessed 13 March./ref>

]

Background

Tension had been simmering between farmers and marauders, on both sides of the frontier, since the dismantlement of Stockenstrom's treaty system. Governor Maitland imposed a new system of treaties on the chiefs without consulting them, while a severe drought forced desperate Xhosa to engage in cattle raids across the frontier in order to survive. In addition, politician Robert Godlonton

Robert Godlonton (1794–1884) ("Moral Bob") was an influential politician of the Cape Colony. He was an 1820 Settler, who developed the press of the Eastern Cape and led the Eastern Cape separatist movement as a representative in the Cape's ...

continued to use his newspaper the ''Graham's Town Journal'' to agitate for Eastern Cape settlers to annex and settle the land that had been returned to the Xhosa after the previous war.

The event that actually ignited the war was a trivial dispute over a raid. A Khoi escort was transporting a manacled Xhosa thief to Grahamstown to be tried for stealing an axe, when Xhosa raiders attacked and killed the Khoi escort. The Xhosa refused to surrender the murderer and war broke out in March 1846.

Initial British setbacks

The regular British forces suffered initial setbacks. A British column sent to confront the Ngqika chief,

The regular British forces suffered initial setbacks. A British column sent to confront the Ngqika chief, Mgolombane Sandile

Mgolombane Sandile (1820–1878) was a ruler of the Right Hand House of the Xhosa Kingdom. A dynamic leader, he led the Xhosa armies in several of the Xhosa-British Wars.

Having recently been equipped with modern fire-arms, Sandile's forces succ ...

, was delayed at the Amatola Mountains, and the attacking Xhosa captured the centre of the three-mile long wagon train which was not being defended, carrying away the British officer's supply of wine and other supplies.

Large numbers of Xhosa then poured across the border as the outnumbered imperial troops fell back, abandoning their outposts. The only successful resistance was from the local Fengu, who heroically defended their villages from the Xhosa forces.

On 28 May, a force of 8,000 Xhosa attacked the last remaining British garrison, at Fort Peddie, but fell back after a long shootout with British and Fengu troops. The Xhosa army then marched on Grahamstown itself, but was held up when a sizable army of Ndlambe Xhosa were defeated on 7 June 1846 by General Somerset on the Gwangu, a few miles from Fort Peddie. However the slow-moving British columns, were considerably hampered by drought and were becoming desperate.

After much debate, they were forced to call in Stockenström and the local Burgher forces.

The local Burghers' campaign

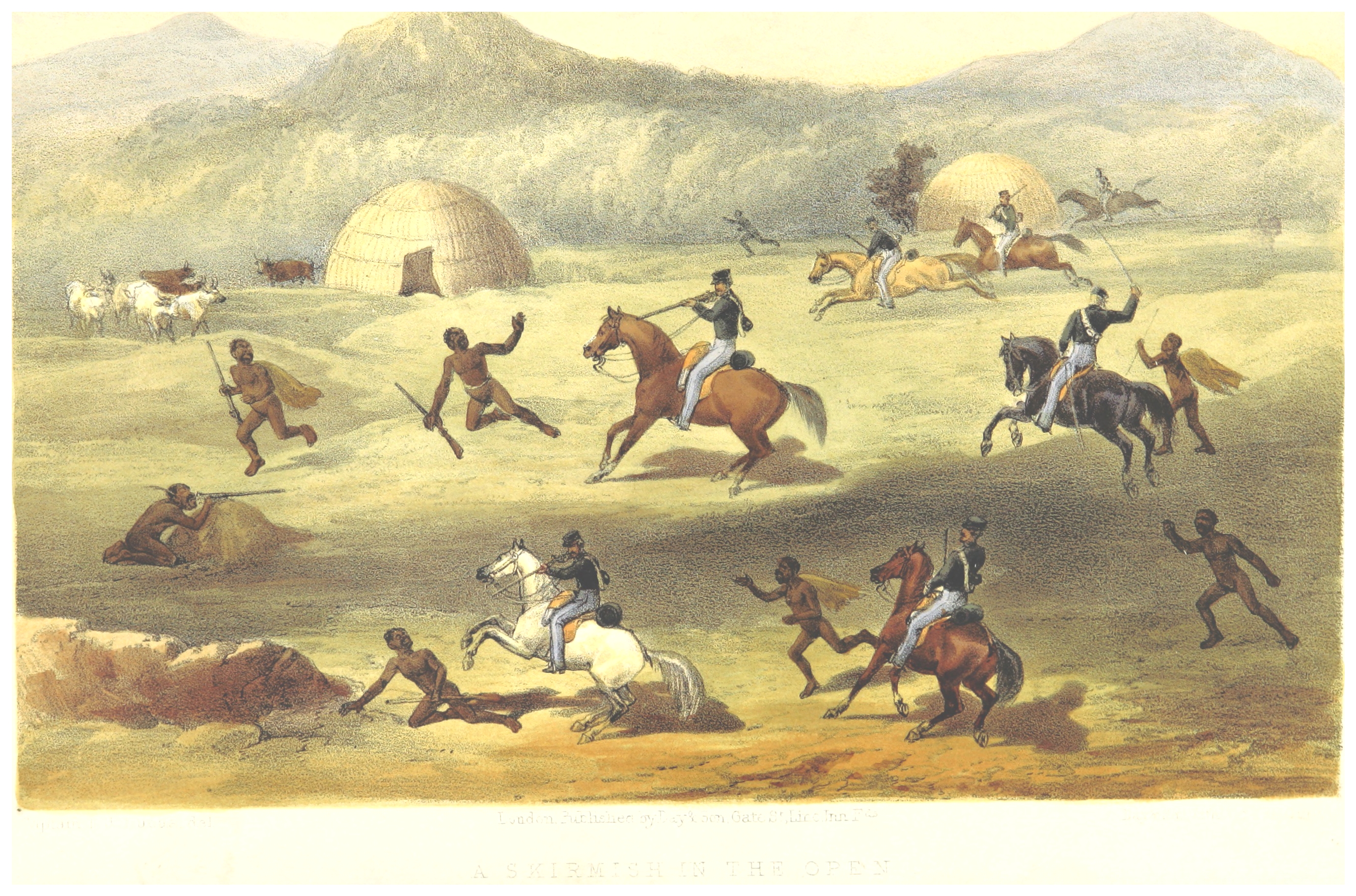

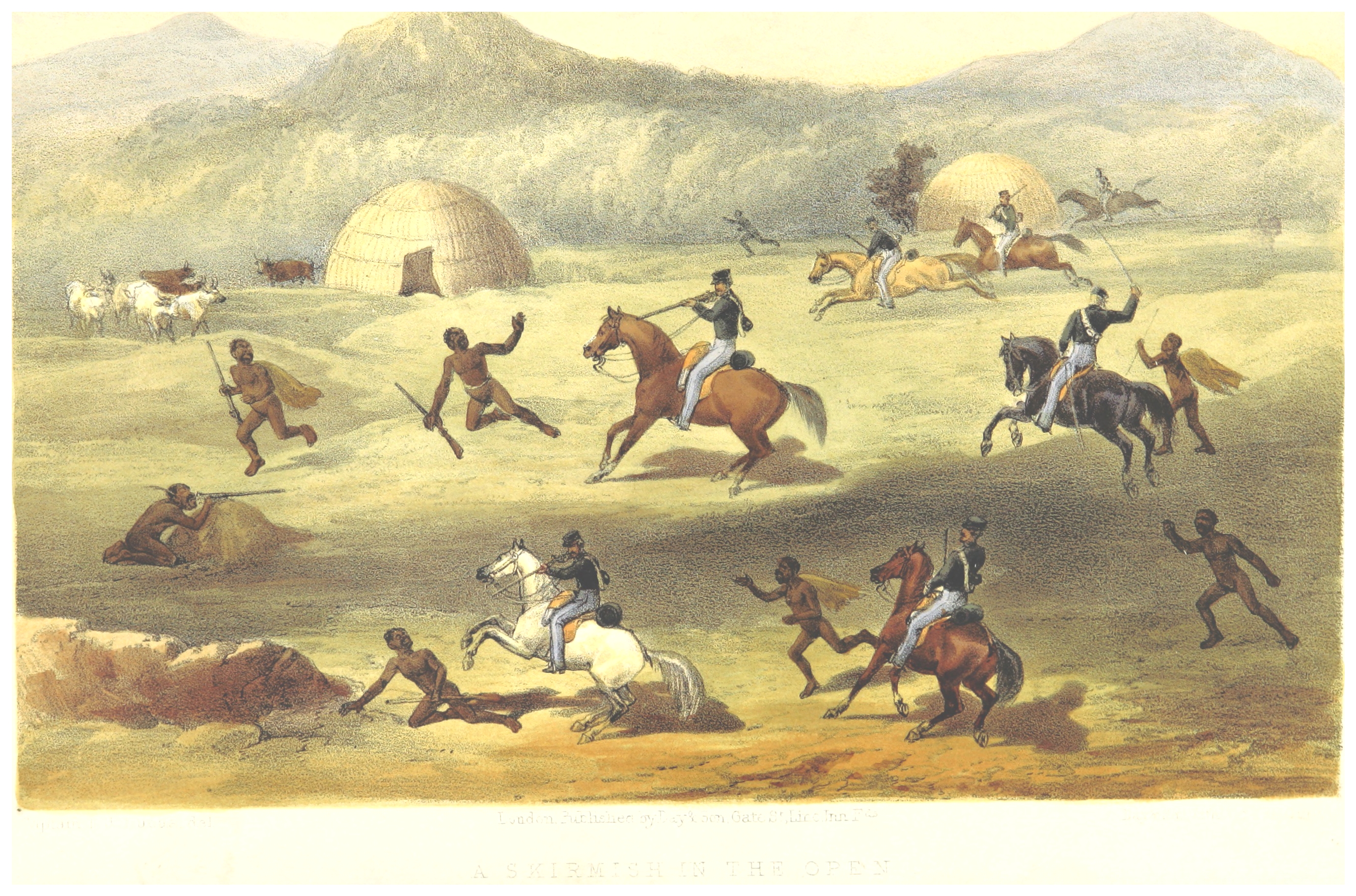

The local Commandos were much more effective in the rough and mountainous terrain, of which they had considerable local knowledge.

After inflicting a string of defeats on the Ngqika, Stockenström took a small and select group of his mounted commandos across the Colony's border and rapidly pushed into the independent Xhosa lands beyond the frontier. They rode deep into the

The local Commandos were much more effective in the rough and mountainous terrain, of which they had considerable local knowledge.

After inflicting a string of defeats on the Ngqika, Stockenström took a small and select group of his mounted commandos across the Colony's border and rapidly pushed into the independent Xhosa lands beyond the frontier. They rode deep into the Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ban ...

Xhosa heartland, directly towards the kraal of Sarhili ("Kreli"), the paramount chief of all the Xhosa.

Due in part to the speed of their approach, they were barely engaged by Xhosa forces and rode directly into Sarhili's capital.

Paramount Chief Sarhili and his generals agreed to meet Stockenström (with his commandants Groepe, Molteno

Molteno (; lmo, label= Brianzöö, Mültée) is a ''comune'' (municipality) and a hill-top town in the Province of Lecco in the Italian region Lombardy, located about northeast of Milan and about southwest of Lecco. As of 31 December 2004, it h ...

and Brownlee), unarmed, on a nearby mountain ridge. The meeting was initially tense – the fathers of both Sarhili and Stockenström had been killed whilst unarmed. Both men were also veterans of several frontier wars against each other and, while they treated each other with extreme respect, Stockenström nonetheless made the extreme demand that Sarhili assume responsibility for any future Ngqika attacks.

After protracted negotiations, Sarhili agreed to return any raided cattle & other property and to relinquish claims to the Ngqika land west of the Kei. He also promised to use his limited authority over the frontier Ngqika to restrain cross-border attacks.

A treaty was signed and the commandos departed on good terms.

Also leading his commando on this campaign was a young man named John Molteno

Sir John Charles Molteno (5 June 1814 – 1 September 1886) was a soldier, businessman, champion of responsible government and the first Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.

Early life

Born in London into a large Anglo-Italian family, Molten ...

, who in later life became the Cape's first Prime Minister. Significantly, his experience of what he believed to be the ineptitude and injustice of the British Empire's frontier policy later informed his government's decisions to oppose the British in the final frontier war.

Later stage of the conflict

However, British Imperial General

However, British Imperial General Peregrine Maitland

General Sir Peregrine Maitland, GCB (6 July 1777 – 30 May 1854) was a British soldier and colonial administrator. He also was a first-class cricketer from 1798 to 1808 and an early advocate for the establishment of what would become the Canadi ...

rejected the treaty and sent an insulting letter back to the Xhosa paramount-chief, demanding greater acts of submission and servility. Furious, Stockenström and his local commandos resigned and departed from the war, leaving the British and the Xhosa – both starving and afflicted by fever – to a long, drawn-out war of attrition.

The effects of the drought were worsened through the use, by both sides, of scorched earth tactics

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

. Gradually, as the armies weakened, the conflict subsided into waves of petty and bloody recriminations. At one point, violence flared up again after Ngqika tribesmen supposedly stole four goats from the neighbouring Kat River Settlement. When the rains came, floods turned the surrounding lands into a quagmire. The violence slowly wound down as both sides weakened, immobile and fever-ridden.

The war continued until Sandile was captured during negotiations and sent to Grahamstown. Although Sandile was soon released, the other chiefs gradually stopped fighting, and by the end of 1847 the Xhosa had been completely subdued after 21 months of fighting.

In the last month of the war (December 1847) Sir Harry Smith reached Cape Town as governor of the colony, and on the 23rd, at a meeting of the Xhosa chiefs, announced the annexation of the country between the Keiskamma and the Kei rivers to the British crown, thus reabsorbing the territory abandoned by order of Lord Glenelg. It was not, however, incorporated with the Cape Colony, but made a crown dependency under the name of British Kaffraria

British Kaffraria was a British colony/subordinate administrative entity in present-day South Africa, consisting of the districts now known as Qonce and East London. It was also called Queen Adelaide's Province.

The British Kaffraria was establish ...

Colony, with King William's Town as capital.

Eighth war (1850–1853)

Background

Large numbers of Xhosa were displaced across the Keiskamma by Governor Harry Smith, and these refugees supplemented the original inhabitants there, causing overpopulation and hardship. Those Xhosa who remained in the colony were moved to towns and encouraged to adopt European lifestyles.

Harry Smith also attacked and annexed the independent

Large numbers of Xhosa were displaced across the Keiskamma by Governor Harry Smith, and these refugees supplemented the original inhabitants there, causing overpopulation and hardship. Those Xhosa who remained in the colony were moved to towns and encouraged to adopt European lifestyles.

Harry Smith also attacked and annexed the independent Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

, hanging the Boer resistance leaders, and in the process alienating the Burghers of the Cape Colony. To cover the mounting expenses he then imposed exorbitant taxes on the local people of the frontier and cut the Cape's standing forces to less than five thousand men.

In June 1850 there followed an unusually cold winter, together with an extreme drought. It was at this time that Smith ordered the displacement of large numbers of Xhosa squatters from the Kat River region.

The war became known as "Mlanjeni's War", after the prophet Mlanjeni who arose among the homeless Xhosa, and who predicted that the Xhosa would be unaffected by the colonists' bullets. Large numbers of Xhosa began leaving the colony's towns and mobilizing in the tribal areas.

The Outbreak of War (December 1850)

Believing that the chiefs were responsible for the unrest caused by Mlanjeni's preaching, Governor Sir Harry Smith travelled to meet with the prominent chiefs. When Sandile refused to attend a meeting outside Fort Cox, Governor Smith deposed him and declared him a fugitive. On 24 December, a British detachment of 650 men under Colonel Mackinnon was attacked by Xhosa warriors in the Boomah Pass. The party was forced to retreat to Fort White, under attack from the Xhosa, having sustained forty-two casualties. The very next day, during Christmas festivities in towns throughout the border region, apparently friendly Xhosa entered the towns to partake in the festivities. At a given signal though, they fell upon the settlers who had invited them into their homes and killed them. With this attack, the bulk of the Ngqika joined the war.

Believing that the chiefs were responsible for the unrest caused by Mlanjeni's preaching, Governor Sir Harry Smith travelled to meet with the prominent chiefs. When Sandile refused to attend a meeting outside Fort Cox, Governor Smith deposed him and declared him a fugitive. On 24 December, a British detachment of 650 men under Colonel Mackinnon was attacked by Xhosa warriors in the Boomah Pass. The party was forced to retreat to Fort White, under attack from the Xhosa, having sustained forty-two casualties. The very next day, during Christmas festivities in towns throughout the border region, apparently friendly Xhosa entered the towns to partake in the festivities. At a given signal though, they fell upon the settlers who had invited them into their homes and killed them. With this attack, the bulk of the Ngqika joined the war.

Initial Xhosa victories

While the Governor was still at Fort Cox, the Xhosa forces advanced on the colony, isolating him there. The Xhosa burned British military villages along the frontier and captured the post at Line Drift. Meanwhile, the Khoi of the Blinkwater River Valley and Kat River Settlement revolted, under the leadership of a half-Khoi, half-Xhosa chief Hermanus Matroos, and managed to capture Fort Armstrong

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

. Large numbers of the "Kaffir Police" – a paramilitary police force the British had established to combat cattle theft – deserted their posts and joined Xhosa war parties. For a while, it appeared that while the Xhosa declared war, Khoi people of the eastern Cape were also fighting and taking up arms against the British.

Harry Smith finally fought his way out of Fort Cox with the help of the local Cape Mounted Riflemen

The Cape Mounted Riflemen were South African military units.

There were two separate successive regiments of that name. To distinguish them, some military historians describe the first as the "imperial" Cape Mounted Riflemen (originally the ' ...

, but found that he had alienated most of his local allies. His policies had made enemies of the Burghers and Boer Commandos, the Fengu, and the Khoi, who formed much of the Cape's local defences. Even some of the Cape Mounted Riflemen refused to fight.

British counter-attack (January 1851)

After these initial successes, however, the Xhosa experienced a series of setbacks. Xhosa forces were repulsed in separate attacks on Fort White and Fort Hare

Fort Hare was an 1835 British-built fort on a rocky outcrop at the foothills of the Amatola Mountains; close to the present day town of Alice, Eastern Cape in South Africa.

History

Originally, Fort Hare was a British fort in the wars between ...

. Similarly, on 7 January, Hermanus and his supporters launched an offensive on the town of Fort Beaufort

Fort Beaufort ( Xhosa: iBhofolo) is a town in the Amatole District of South Africa's Eastern Cape Province, and had a population of 25,668 in 2011. The town was established in 1837 and became a municipality in 1883. The town lies at the conflu ...

, which was defended by a small detachment of troops and local volunteers. The attack failed however, and Hermanus was killed. The Cape Government also eventually agreed to levy a force of local gunmen (predominantly Khoi) to hold the frontier, allowing Smith to free some imperial troops for offensive action.

By the end of the month of January, the British were beginning to receive reinforcements from Cape Town

Cape Town ( af, Kaapstad; , xh, iKapa) is one of South Africa's three capital cities, serving as the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. It is the legislative capital of the country, the oldest city in the country, and the second largest ...

and a force under Colonel Mackinnon was able to drive north from King William's Town

Qonce, formerly known as King William's Town, is a city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa along the banks of the Buffalo River. The city is about northwest of the Indian Ocean port of East London. Qonce, with a population of around ...

to resupply the beleaguered garrisons at Fort White, Fort Cox and Fort Hare

Fort Hare was an 1835 British-built fort on a rocky outcrop at the foothills of the Amatola Mountains; close to the present day town of Alice, Eastern Cape in South Africa.

History

Originally, Fort Hare was a British fort in the wars between ...

. With fresh men and supplies, the British expelled the remainder of Hermanus' rebel forces (now under the command of Willem Uithaalder) from Fort Armstrong and drove them west toward the Amatola Mountains

Amatola, Amatole or Amathole are a range of densely forested mountains, situated in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The word ''Amathole'' means ‘calves’ in Xhosa, and Amathole District Municipality, which lies to the south, is named ...

. Over the coming months, increasing numbers of Imperial troops arrived, reinforcing the heavily outnumbered British and allowing Smith to lead sweeps across the frontier country.

In 1852, HMS Birkenhead

Two ships of the British Royal Navy have been named HMS ''Birkenhead'', after the English town of Birkenhead.

* was an iron-hulled troopship launched in 1845 and notably wrecked in 1852.

* was a light cruiser launched in 1915, in action at Jut ...

was wrecked at Gansbaai

Gansbaai (Dutch/Afrikaans for "bay of geese," sometimes referred to as Gans Bay or Gangs Bay) is a fishing town and popular tourist destination in the Overberg District Municipality, Western Cape, South Africa. It is known for its dense populatio ...

while bringing reinforcements to the war at the request of Sir Harry Smith

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry George Wakelyn Smith, 1st Baronet, GCB (28 June 1787 – 12 October 1860) was a notable English soldier and military commander in the British Army of the early 19th century. A veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, he is a ...

. As the ship sank, the men (mostly new recruits) stood silently in rank, while the women and children were loaded into the lifeboats. They remained in rank as the ship slipped under and over 300 died.

Final stages of the conflict

Insurgents led by Maqoma established themselves in the forested Waterkloof. From this base they managed to plunder surrounding farms and torch the homesteads. Maqoma's stronghold was situated on Mount Misery, a natural fortress on a narrow neck wedged between the Waterkloof and Harry's Kloof. The Waterkloof conflicts lasted two years. Maqoma also led an attack on Fort Fordyce and inflicted heavy losses on the forces of Sir Harry Smith.

In February 1852, the British Government decided that Sir Harry Smith's inept rule had been responsible for much of the violence, and ordered him replaced by

Insurgents led by Maqoma established themselves in the forested Waterkloof. From this base they managed to plunder surrounding farms and torch the homesteads. Maqoma's stronghold was situated on Mount Misery, a natural fortress on a narrow neck wedged between the Waterkloof and Harry's Kloof. The Waterkloof conflicts lasted two years. Maqoma also led an attack on Fort Fordyce and inflicted heavy losses on the forces of Sir Harry Smith.

In February 1852, the British Government decided that Sir Harry Smith's inept rule had been responsible for much of the violence, and ordered him replaced by George Cathcart

Major-General Sir George Cathcart (12 May 1794 – 5 November 1854) was a British general and diplomat.

Military career

He was born in Renfrewshire, son of William Cathcart, 1st Earl Cathcart. After receiving his education at Eton and in Edin ...

, who took charge in March. For the last six months, Cathcart ordered scourings of the countryside for rebels. In February 1853, Sandile and the other chiefs surrendered.

The 8th frontier war was the most bitter and brutal in the series of Xhosa wars. It lasted over two years and ended in the complete subjugation of the Ciskei Xhosa.

Cattle-killing movement (1856–1858)

The great Cattle-killing was a millennialist movement which began among the Xhosa in 1856, and led them to destroy their own means of subsistence in the belief that it would bring about salvation by supernatural spirits.

In April 1856 the 16-year-old Xhosa

The great Cattle-killing was a millennialist movement which began among the Xhosa in 1856, and led them to destroy their own means of subsistence in the belief that it would bring about salvation by supernatural spirits.

In April 1856 the 16-year-old Xhosa prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings from the s ...

ess Nongqawuse began to declare that she had received a message from the Xhosa people's ancestors, promising deliverance from their hardships. She preached that the ancestors would return from the afterlife in huge numbers, drive all Europeans into the sea, and give the Xhosa bounteous gifts of horses, sheep, goats, dogs, fowls, and all manner of clothing and food in great amounts. They would also restore the elderly to youth and would usher in a utopian era of prosperity. However, she declared that the dead ancestors would only enact this on condition that the Xhosa first destroyed all their means of subsistence. They needed to kill all of their cattle and burn all of their crops.

At first no one believed Nongquwuse's prophecy and the Xhosa nation ignored her prophecy. But when King Sarhili began to kill his cattle, more and more people began to believe that Nongquwuse was an ''igqirha'' (diviner) who could communicate with the ancestors. They too killed their cattle and destroyed their crops. The cult grew and built up momentum, sweeping across the eastern Cape. The government authorities of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

feared chaos, famine and economic collapse, so they desperately appealed in vain to the Xhosa to ignore the prophecies. They even arrested Nongqawuse herself for disturbance caused.

The return of the ancestors

An ancestor, also known as a forefather, fore-elder or a forebear, is a parent or (recursively) the parent of an antecedent (i.e., a grandparent, great-grandparent, great-great-grandparent and so forth). ''Ancestor'' is "any person from whom ...

was predicted to occur on 18 February 1857. The Xhosa, especially the King, Sarhili, heeded the demand to destroy food sources and clothes and enforced it on others throughout the country. When the day came, the Xhosa nation waited en masse for the momentous events to occur, only to be bitterly disappointed. With no means of subsistence, famine set in.

The cattle killings continued into 1858, leading to the starvation of thousands. Disease was also spread from the cattle killings. This gave the settlers power over the remainder of the Xhosa nation who were often forced to turn to the colonists for food, blankets and other relief.

Ninth war (1877–1879)

Background

The ninth and final frontier war – also known as the "Fengu-Gcaleka War" or "Ngcayechibi's War", the latter being the name of the headman at whose feast the initial bar fight occurred – involved several competing powers: the

The ninth and final frontier war – also known as the "Fengu-Gcaleka War" or "Ngcayechibi's War", the latter being the name of the headman at whose feast the initial bar fight occurred – involved several competing powers: the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

Government and its Fengu allies, the British Empire, and the Xhosa armies (Gcaleka and Ngqika). The Cape Colony addressed local needs through their own devices, creating a period of peace and prosperity, and achieved partial independence from Britain with "Responsible Government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive bran ...

"; it had relatively little interest in territorial expansion. The frontier was policed lightly using small, highly mobile, mounted mixed-race commandos that were recruited locally from Boer, Fengu, Khoi and settler frontier peoples. The multi-racial franchise, and legal recognition for indigenous systems of land tenure, had also gone some way to easing frontier tensions. Any further intrusion of the British government in Cape affairs to disrupt this state was thought unnecessary and ill-advised.

The British Government sought to increase control in southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number of ...

by uniting all the states of the region into a Confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

under the overall rule of the British Empire, the same policy that was successfully applied to Canada. This Confederation scheme required that the remaining independent Black States be annexed; a frontier war was seen as an ideal opportunity for such a conquest. Both the Cape Colony and Xhosa shared the view that actions to achieve such a scheme at that time would create instability.

The integration of the Black African

Black is a Racialization, racialized classification of people, usually a Politics, political and Human skin color, skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have ...

population of the frontier into the life patterns and practices of the Cape Colony had developed unevenly. The Fengu had rapidly adapted to and accepted the changes coming to southern Africa by taking to urban trade. The Gcaleka Xhosa resided predominately in the independent Gcaleka

The Gcaleka House is the Great house of the Xhosa Kingdom in what is now the Eastern Cape. Its royal palace is in the former Transkei and its counterpart in the former Ciskei is the Rharhabe, which is the right hand house of Phalo.

The Gcaleka H ...

land to the east and had suffered greatly from the effects of war, alcoholism and Nongqawuse's cattle killing. They bitterly resented the material success of the Fengu, although some Gcaleka lived within the Cape's borders.

A series of devastating droughts across the Transkei threatened the relative peace which had prevailed for the previous few decades. In the memorable summary of the historian De Kiewiet: ''"In South Africa, the heat of drought easily becomes the fever of war."'' The drought had started in 1875 in Gcalekaland and had spread to other parts of the Transkei and Basutoland, as well as to the Cape Colony controlled Ciskei. By 1877, it had become the most severe drought ever recorded. In 1877, political tensions among Xhosa e began to emerge, particularly between the Mfengu

The ''amaMfengu'' (in the Xhosa language ''Mfengu'', plural ''amafengu'') was a reference of Xhosa clans whose ancestors were refugees that fled from the Mfecane in the early 19th century to seek land and protection from the Xhosa and have sinc ...

, the Thembu

The Thembu Kingdom (''abaThembu ababhuzu-bhuzu, abanisi bemvula ilanga libalele'') was a Xhosa-state in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

According to Xhosa oral tradition, the AbaThembu migrated along the east coast of Southern Africa ...

and the Gcaleka. A wedding celebration in September 1877 was the scene of a bar fight when the tensions emerged after Gcaleka harassed the Fengu in attendance. Later in the same day, Gcaleka attacked a Cape Colony police outpost, which was manned predominantly by a Fengu ethnic police force.

Outbreak

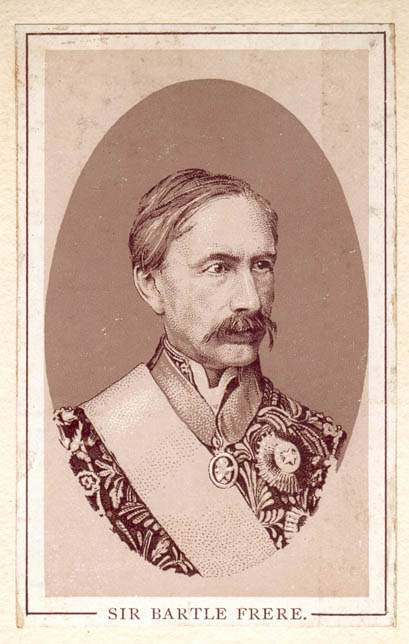

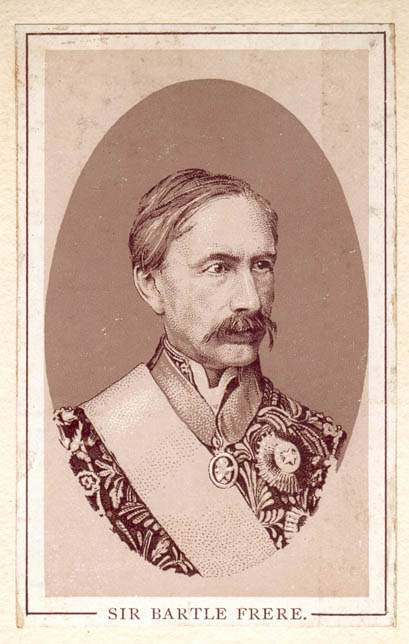

In September 1877 the Cape Colony government rejected the second attempt to implement the Confederation scheme, this time put forth by Governor

In September 1877 the Cape Colony government rejected the second attempt to implement the Confederation scheme, this time put forth by Governor Henry Bartle Frere

Sir Henry Bartle Edward Frere, 1st Baronet, (29 March 1815 – 29 May 1884) was a Welsh British colonial administrator. He had a successful career in India, rising to become Governor of Bombay (1862–1867). However, as High Commissioner for ...

. The attack by the Gcaleka on the predominantly Fengu ethnic police force at a Cape Colony police outpost was thought by the Cape Colony government as tribal violence best left for local police management. Frere used the incident as a pretext for launching an invasion of the independent neighbouring state of Gcalekaland. Sarhili, the paramount-chief of Gcalekaland, was summoned by Frere, but declined the invitation in fear of arrest and coercion. Frere wrote to him to declare him deposed and at war. Frere contacted radical settler groups who desired further intervention on the Cape frontier, and did not quell rumours of an impending Xhosa invasion.

The Cape Colony's War

Chief Sarhili faced intense pressure from belligerent factions within his own government and mobilised his armies for their movement to the frontier. The Cape Government reiterated its insistence that the matter was best left to local resolution and did not constitute an international war for imperial military intervention. High-pressure negotiations by Cape Prime Minister John Charles Molteno extracted a promise from Britain that imperial troops would stay put and on no account cross the frontier. Gcaleka forces of 8000 attacked a Cape police outpost near the frontier at Ibeka; a fierce shoot-out followed but the Gcaleka forces were dispersed. Soon, several other outposts and stations along the frontier were coming under attack. The Cape Government now had to use all available diplomatic leverage it had to prevent British imperial forces from crossing the frontier.

The Cape's local paramilitaries (mounted commandos of mainly

Chief Sarhili faced intense pressure from belligerent factions within his own government and mobilised his armies for their movement to the frontier. The Cape Government reiterated its insistence that the matter was best left to local resolution and did not constitute an international war for imperial military intervention. High-pressure negotiations by Cape Prime Minister John Charles Molteno extracted a promise from Britain that imperial troops would stay put and on no account cross the frontier. Gcaleka forces of 8000 attacked a Cape police outpost near the frontier at Ibeka; a fierce shoot-out followed but the Gcaleka forces were dispersed. Soon, several other outposts and stations along the frontier were coming under attack. The Cape Government now had to use all available diplomatic leverage it had to prevent British imperial forces from crossing the frontier.

The Cape's local paramilitaries (mounted commandos of mainly Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

, Thembu

The Thembu Kingdom (''abaThembu ababhuzu-bhuzu, abanisi bemvula ilanga libalele'') was a Xhosa-state in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

According to Xhosa oral tradition, the AbaThembu migrated along the east coast of Southern Africa ...

and Fengu origin) were deployed by Molteno under the leadership of Commander Veldman Bikitsha and Chief Magistrate

Chief magistrate is a public official, executive or judicial, whose office is the highest in its class. Historically, the two different meanings of magistrate have often overlapped and refer to, as the case may be, to a major political and admini ...

Charles Griffith. The commandos swiftly engaged and defeated an army of Gcaleka gunmen. They then crossed the frontier and pushed into Gcalekaland. Dividing into three lightly equipped, fast-moving columns, the commandos devastated the Gcaleka armies, which dispersed and fled eastwards. The Cape units tracked the fleeing remnants right through Gcalekaland, stopping only when they reached neutral Bomvanaland on the far side. The war was over in three weeks. Sarhili had also recently applied for peace. With few incentives to conquer or occupy the land, and with the violence subsiding, the Cape Government recalled their commandos, who returned home and disbanded.

Bartle Frere's War Council

During the Cape's lightning quick campaign, Governor Frere had established a "war-council" at nearby

During the Cape's lightning quick campaign, Governor Frere had established a "war-council" at nearby King William's Town

Qonce, formerly known as King William's Town, is a city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa along the banks of the Buffalo River. The city is about northwest of the Indian Ocean port of East London. Qonce, with a population of around ...

to direct the war against Gcalekaland. Frere and his Lieutenant General Sir Arthur Cunynghame were to represent the British Empire on this council, while two of Molteno's ministers, John X. Merriman

John Xavier Merriman (15 March 1841 – 1 August 1926) was the last prime minister of the Cape Colony before the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910.

Early life

He was born in Street, Somerset, England. His parents were Nathaniel Jame ...

and Charles Brownlee

Charles Pacalt Brownlee (1821- 13 September 1890) was a politician and writer of the Cape Colony. He was the first Secretary for Native Affairs in the Cape.

Early life

Born in 1821, the son of the linguist, botanist and missionary, John Brownle ...

, were appointed to represent local Cape interests.

The council was torn apart by argument from the beginning, as Frere refused Gcaleka appeals and worked towards full British occupation of Gcalekaland for white settlement and his future confederation. Frere also increasingly insisted on having complete imperial control of the war.

The Cape government on the other hand was reluctant to see its local Commandos brought under British imperial command, in what it considered to be essentially a local conflict, not an imperial war of conquest. The Cape had only recently attained local democracy and was extremely suspicious of Imperial infringements upon it. It also considered the slow-moving British troop columns to be absurdly unsuitable for frontier warfare – immobile, ineffective and vastly more expensive than local Cape forces. This last point of contention was chiefly exacerbated by Frere's insistence that the Cape's government pay for his imported British imperial troops, as well as its own local forces. The Cape Government wanted to fund and use only its own local forces. It did not desire British troops to operate in the Cape Colony in the first place, and especially objected to being forced to fund them.

Merriman, who Molteno had appointed to oversee the Cape's war effort, initially worked hard to cooperate with Frere, but increasingly came to share Molteno's views on the ineptitude and injustice of British imperial policy in southern Africa.

The Imperial War

The second stage of the war began when Frere ordered the disarmament of all Black peoples of the Cape. There was confusion and uproar from the Cape's many black soldiers and a furious protest from the Cape Government. Militia deserted and protests erupted, in the face of which Cunynghame panicked and overreacted by unilaterally deploying the imperial troops to thinly encircle the whole of

The second stage of the war began when Frere ordered the disarmament of all Black peoples of the Cape. There was confusion and uproar from the Cape's many black soldiers and a furious protest from the Cape Government. Militia deserted and protests erupted, in the face of which Cunynghame panicked and overreacted by unilaterally deploying the imperial troops to thinly encircle the whole of British Kaffraria

British Kaffraria was a British colony/subordinate administrative entity in present-day South Africa, consisting of the districts now known as Qonce and East London. It was also called Queen Adelaide's Province.

The British Kaffraria was establish ...

. Faced with growing discontent, the Cape demanded that the British Government fire Cunynghame, abandon its racial disarmament policy, and allow the Cape to deploy its (predominantly black) paramilitaries to establish order. However Frere refused and brought in Imperial troops to enforce the disarmament, and then to invade Gcalekaland once again. This time to annex it and occupy it for the purpose of white settlement.

The British initially attempted to repeat the successful strategy of the Cape's previous campaign. After similarly dividing into three columns, the slow-moving foreign troops soon became disorientated and exhausted. They were unable to engage or even to find the dispersed Gcaleka, who were swiftly moving and regrouping. As the British scoured Gcalekaland, the regrouped Gcaleka army easily slipped past them and crossed the border into the Cape Colony. Here they were joined by Sandile who led his Ngqika nation into rebellion.

The combined Xhosa armies laid waste to the frontier region. Fengu towns and other frontier settlements were sacked, supply lines were cut and outposts were evacuated as the British fell back.

Up until now, Molteno had been heavily engaged in a high-level diplomatic battle with Britain to preserve the Cape Colony's constitutional independence. However, with the Cape's frontier collapsing in chaos, he now made for the frontier in person, where he confronted the British Governor with a heavy condemnation for bad intentions and incompetence. He demanded the free command of the Cape's indigenous forces to operate and contain the violence, making it clear that he was content to sacrifice his job rather than tolerate further British interference.

Frere's next move was to appeal to the authority of the

The combined Xhosa armies laid waste to the frontier region. Fengu towns and other frontier settlements were sacked, supply lines were cut and outposts were evacuated as the British fell back.

Up until now, Molteno had been heavily engaged in a high-level diplomatic battle with Britain to preserve the Cape Colony's constitutional independence. However, with the Cape's frontier collapsing in chaos, he now made for the frontier in person, where he confronted the British Governor with a heavy condemnation for bad intentions and incompetence. He demanded the free command of the Cape's indigenous forces to operate and contain the violence, making it clear that he was content to sacrifice his job rather than tolerate further British interference.

Frere's next move was to appeal to the authority of the British Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of col ...

to formally dissolve the elected Cape government, which was now stubbornly standing in the way of the British Empire, and assume direct imperial control over the entire country.

Increasing numbers of Xhosa armies now poured across the frontier. Towns and farms throughout the region were now burning, and the remaining frontier forts filled with refugees fleeing the invasion. British troops remained thin on the ground as much of them still remained idle in Gcalekaland, where they had been sent for the purpose of occupation.

However Frere was lucky in that he still had access to the frontier militia and Fengu regiments of the Cape Government he had just overthrown. These forces, again under their legendary commander Veldman Bikitsha, managed to engage and finally defeat the Gcaleka on 13 January (near Nyumaxa).

The imperial troops assisted, but were tired, short of rations and unable to follow up on the victory. A subsequent attack was barely repelled on 7 February (Battle of Kentani

Centane, formerly Kentane or Kentani is a settlement in Amathole District Municipality

Amathole is one of the 7 districts of Eastern Cape province of South Africa. The seat of Amathole is East London. Over 90% of its 892,637 people speak ...

or "Centane") with considerable more help from the Fengu and the local Frontier Light Horse

The Frontier Light Horse, a mounted unit of 200 volunteers, was raised at King William's Town, Eastern Cape Colony in 1877 by Lieutenant Frederick Carrington.

It is often referred to as the Cape Frontier Light Horse and served under Brevet Lieute ...

militia.

The exhausted Gcaleka finally pulled out from the conflict, but Sandile's rebel Ngqika armies fought on. The rebels eluded the Imperial troops once again and moved into the Amatola mountain range, beginning a final stage of guerrilla warfare. Cunynghame was meanwhile removed from his authority by London, and his replacement, Lieutenant General Thesiger took over command.

The Guerrilla War

The Amatola Range had served as a mountain stronghold for Xhosa insurgents many times before, with its vast, dark, creeper-entwined forests.

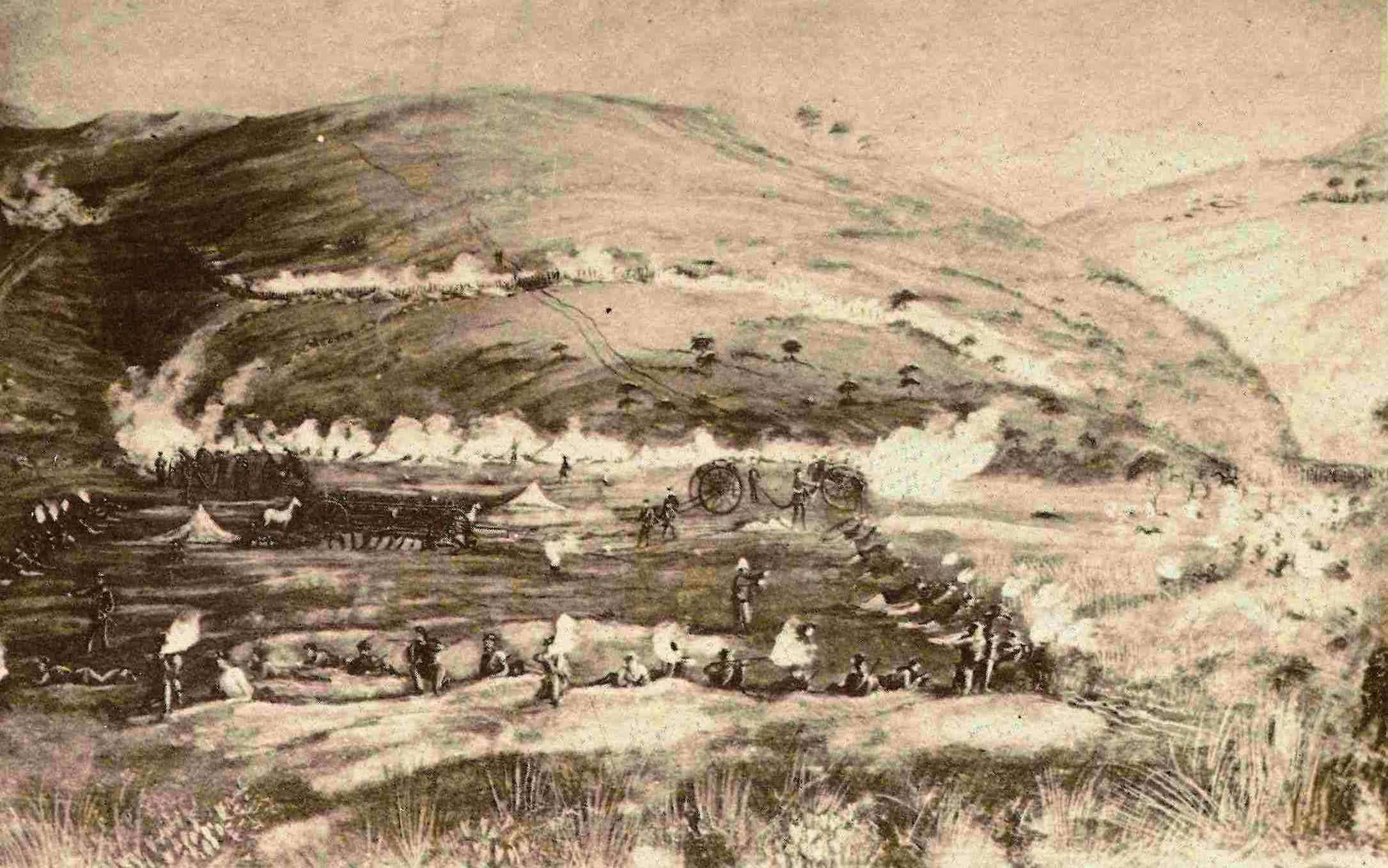

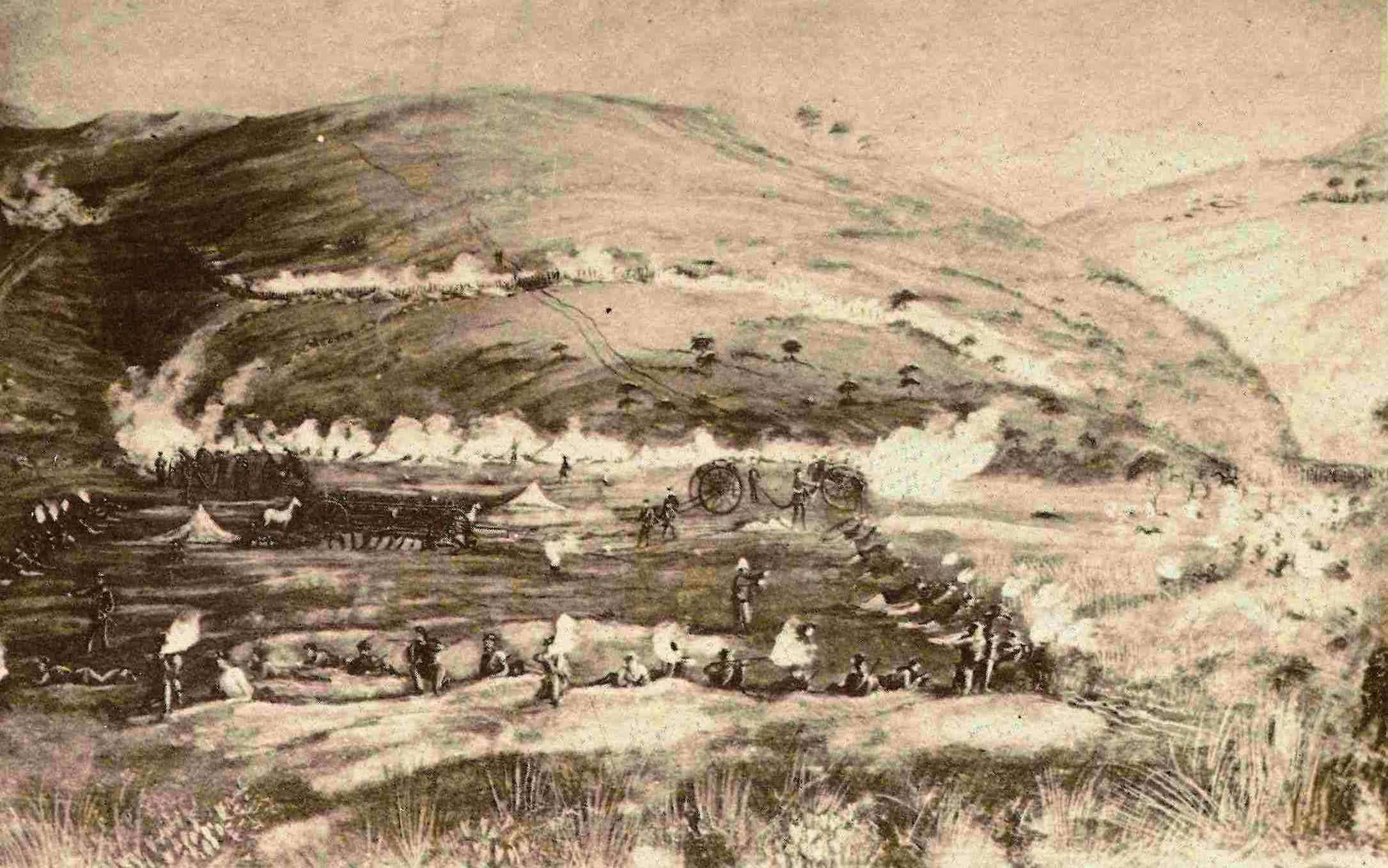

In March 1878, British troops entered the mountain ranges to pursue Sandile's rebels but were hopelessly outmaneuvered. They were eluded, led astray and ambushed time and time again, as the rebels easily slipped past their slow-moving troop columns. Flag signalling, path systems and other techniques were tried, but to no effect. The British were very inexperienced with the environment and plagued by mismanagement, stretched supply lines, sickness and other hardships. Meanwhile, the local Cape commandos (Boer and Fengu) held back, reluctant to get involved.

Finally the British adopted the strategy which the locals had been recommending from the beginning. This involved dividing the vast territory into 11 military provinces and stationing a mounted garrison in each. If a rebel regiment was encountered it was chased, until it entered the next military province, where the next garrison (fresh and close to supplies) would take over the pursuit. The valley exits from the range were then fortified. Under this uninterrupted pressure the rebel forces quickly splintered and began to surrender, Sandile himself fled down into the valley of the Fish River where he was intercepted by a Fengu commando. In the final shoot out he was accidentally killed by a stray bullet. The surviving rebels were granted an amnesty.

The Amatola Range had served as a mountain stronghold for Xhosa insurgents many times before, with its vast, dark, creeper-entwined forests.

In March 1878, British troops entered the mountain ranges to pursue Sandile's rebels but were hopelessly outmaneuvered. They were eluded, led astray and ambushed time and time again, as the rebels easily slipped past their slow-moving troop columns. Flag signalling, path systems and other techniques were tried, but to no effect. The British were very inexperienced with the environment and plagued by mismanagement, stretched supply lines, sickness and other hardships. Meanwhile, the local Cape commandos (Boer and Fengu) held back, reluctant to get involved.