John XXIII on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

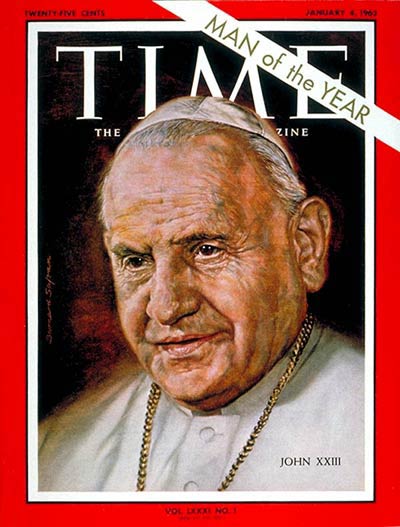

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was born on 25 November 1881 in

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was born on 25 November 1881 in

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation has carried out exhaustive historical research related to different events connected with interventions of Nuncio Roncalli in favour of Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. As of September 2000 three reports have been published compiling different studies and materials of historical research about the humanitarian actions carried out by Roncalli when he was nuncio.

In 2011, the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation submitted a massive file (the Roncalli Dossier) to Yad Vashem, with a strong petition and recommendation to bestow upon him the title of

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation has carried out exhaustive historical research related to different events connected with interventions of Nuncio Roncalli in favour of Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. As of September 2000 three reports have been published compiling different studies and materials of historical research about the humanitarian actions carried out by Roncalli when he was nuncio.

In 2011, the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation submitted a massive file (the Roncalli Dossier) to Yad Vashem, with a strong petition and recommendation to bestow upon him the title of

Roncalli received a message from Mgr. Montini on 14 November 1952 asking him if he would want to become the new Patriarch of Venice in light of the nearing death of

Roncalli received a message from Mgr. Montini on 14 November 1952 asking him if he would want to become the new Patriarch of Venice in light of the nearing death of

On 25 December 1958, he became the first pope since 1870 to make pastoral visits in his

On 25 December 1958, he became the first pope since 1870 to make pastoral visits in his

Far from being a mere "stopgap" pope, to great excitement, John XXIII called for an

Far from being a mere "stopgap" pope, to great excitement, John XXIII called for an

John XXIII beatified four individuals in his reign:

John XXIII beatified four individuals in his reign:

On 11 October 1962, the first session of the

On 11 October 1962, the first session of the

On 23 September 1962, Pope John XXIII was diagnosed with

On 23 September 1962, Pope John XXIII was diagnosed with

He was known affectionately as the "Good Pope". His cause for canonization was opened under

He was known affectionately as the "Good Pope". His cause for canonization was opened under

From his teens when he entered the seminary, he maintained a diary of spiritual reflections that was subsequently published as the ''Journal of a Soul''. The collection of writings charts Roncalli's goals and his efforts as a young man to "grow in holiness" and continues after his election to the papacy; it remains widely read.

The opening titles of

From his teens when he entered the seminary, he maintained a diary of spiritual reflections that was subsequently published as the ''Journal of a Soul''. The collection of writings charts Roncalli's goals and his efforts as a young man to "grow in holiness" and continues after his election to the papacy; it remains widely read.

The opening titles of

online

* Hebblethwaite, Peter. ''Pope John XXIII, Shepherd of the Modern World'' (1985). 550pp. * * . * * * * * Wilsford, David. ed., ''Political Leaders of Contemporary Western Europe: A Biographical Dictionary'' (Greenwood, 1995) pp 203–207. * Zizola, Giancarlo; Barolini, Helen. ''Utopia of Pope John XXIII'' (1979), 379pp.

online

*

excerpt

his spiritual diary.

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and sovereign of the Vatican City State

Vatican City (), officially the Vatican City State ( it, Stato della Città del Vaticano; la, Status Civitatis Vaticanae),—'

* german: Vatikanstadt, cf. '—' (in Austria: ')

* pl, Miasto Watykańskie, cf. '—'

* pt, Cidade do Vati ...

from 28 October 1958 until his death in June 1963. Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was one of thirteen children born to Marianna Mazzola and Giovanni Battista Roncalli in a family of sharecroppers

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

who lived in Sotto il Monte

Sotto il Monte ( lmo, label=Bergamasque, Sóta 'l Mut; "Under the Mountain"), officially Sotto il Monte Giovanni XXIII, is a ''comune'' in northern Italy. Located in the Province of Bergamo in the Region of Lombardy, the town's official name, mu ...

, a village in the province of Bergamo

Bergamo (; lmo, Bèrghem ; from the proto- Germanic elements *''berg +*heim'', the "mountain home") is a city in the alpine Lombardy region of northern Italy, approximately northeast of Milan, and about from Switzerland, the alpine lakes Como ...

, Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

. He was ordained to the priesthood on 10 August 1904 and served in a number of posts, as nuncio

An apostolic nuncio ( la, nuntius apostolicus; also known as a papal nuncio or simply as a nuncio) is an ecclesiastical diplomat, serving as an envoy or a permanent diplomatic representative of the Holy See to a state or to an international or ...

in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and a delegate to Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. In a consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

*Consistory ...

on 12 January 1953 Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

made Roncalli a cardinal as the Cardinal-Priest of Santa Prisca

Santa Prisca is a titular church of Rome, on the Aventine Hill, for Cardinal-priests. It is recorded as the ''Titulus Priscae'' in the acts of the 499 synod.

Church

It is devoted to Saint Prisca, a 1st-century martyr, whose relics are contai ...

in addition to naming him as the Patriarch of Venice

The Patriarch of Venice ( la, Patriarcha Venetiarum; it, Patriarca di Venezia) is the ordinary bishop of the Archdiocese of Venice. The bishop is one of the few patriarchs in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church (currently three other Latin ...

. Roncalli was unexpectedly elected pope

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

on 28 October 1958 at age 76 after 11 ballots. Pope John XXIII surprised those who expected him to be a caretaker pope by calling the historic Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

(1962–1965), the first session opening on 11 October 1962.

John XXIII made many passionate speeches during his pontificate. His views on equality were summed up in his statement, "We were all made in God's image, and thus, we are all Godly alike." He made a major impact on the Catholic Church, opening it up to dramatic unexpected changes promulgated at the Vatican Council and by his own dealings with other churches and nations. In Italian politics, he prohibited bishops from interfering with local elections, and he helped the Christian Democracy

Christian democracy (sometimes named Centrist democracy) is a political ideology that emerged in 19th-century Europe under the influence of Catholic social teaching and neo-Calvinism.

It was conceived as a combination of modern democratic ...

to cooperate with the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a socialist and later social-democratic political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parties of the country.

Founded in Genoa in 1892, ...

. In international affairs, his "Ostpolitik" engaged in dialogue with the communist countries of Eastern Europe. He especially reached out to the Eastern Orthodox churches. His overall goal was to modernize the Church by emphasizing its pastoral role

Pastoral care is an ancient model of emotional, social and spiritual support that can be found in all cultures and traditions.

The term is considered inclusive of distinctly non-religious forms of support, as well as support for people from rel ...

, and its necessary involvement with affairs of state. He dropped the traditional rule of 70 cardinals, increasing the size to 85. He used the opportunity to name the first cardinals from Africa, Japan, and the Philippines. He promoted ecumenical movements in cooperation with other Christian faiths. In doctrinal matters, he was a traditionalist, but he ended the practice of automatically formulating social and political policies on the basis of old theological propositions.

He did not live to see the Vatican Council to completion. His cause for canonization

Canonization is the declaration of a deceased person as an officially recognized saint, specifically, the official act of a Christian communion declaring a person worthy of public veneration and entering their name in the canon catalogue of ...

was opened on 18 November 1965 by his successor, Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his ...

, who declared him a Servant of God

"Servant of God" is a title used in the Catholic Church to indicate that an individual is on the first step toward possible canonization as a saint.

Terminology

The expression "servant of God" appears nine times in the Bible, the first five in th ...

. On 5 July 2013, Pope Francis

Pope Francis ( la, Franciscus; it, Francesco; es, link=, Francisco; born Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 17 December 1936) is the head of the Catholic Church. He has been the bishop of Rome and sovereign of the Vatican City State since 13 March 2013. ...

– bypassing the traditionally required second miracle – declared John XXIII a saint, based on his virtuous, model lifestyle, and because of the good which had come from his opening of the Second Vatican Council. He was canonized alongside Pope John Paul II

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

on 27 April 2014. John XXIII today is affectionately known as the Good Pope ( it, il Papa buono).

Early life

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was born on 25 November 1881 in

Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli was born on 25 November 1881 in Sotto il Monte

Sotto il Monte ( lmo, label=Bergamasque, Sóta 'l Mut; "Under the Mountain"), officially Sotto il Monte Giovanni XXIII, is a ''comune'' in northern Italy. Located in the Province of Bergamo in the Region of Lombardy, the town's official name, mu ...

, a small country village in the Bergamo

Bergamo (; lmo, Bèrghem ; from the proto- Germanic elements *''berg +*heim'', the "mountain home") is a city in the alpine Lombardy region of northern Italy, approximately northeast of Milan, and about from Switzerland, the alpine lakes Como ...

province of the Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

region of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. He was the eldest son of Giovanni Battista Roncalli (1854–1935) and his wife Marianna Giulia Mazzola (1855–1939), and fourth in a family of thirteen. His siblings were:

* Maria Caterina (1877–1883)

* Teresa (1879–1954), who married Michele Ghisleni in 1899

* Ancilla (1880–1953)

* Francesco Saverio (1883–1976), who married Maria Carrara in 1907

* Maria Elisa (1884–1955)

* Assunta Casilda (1886–1980), who married Giovanni Battista Marchesi in 1907

* Domenico Giuseppe (1888–1888)

* Alfredo (1889–1972)

* Giovanni Francesco (1891–1956), who married Caterina Formenti in 1919

* Enrica (1893–1918)

* Giuseppe Luigi (1894–1981), who married Ida Biffi in 1922

* Luigi (1896–1898)

His family worked as sharecroppers

Sharecropping is a legal arrangement with regard to agricultural land in which a landowner allows a tenant to use the land in return for a share of the crops produced on that land.

Sharecropping has a long history and there are a wide range ...

, as did most of the people of Sotto il Monte – a striking contrast to that of his predecessor, Eugenio Pacelli

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

(Pope Pius XII), who came from an ancient aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

family long connected to the papacy. Roncalli was nonetheless a descendant of an Italian noble family, albeit from a secondary and impoverished branch; "(he) derived from no mean origins but from worthy and respected folk who can be traced right back to the beginning of the fifteenth century". The Roncallis maintained a vineyard and cornfields, and kept cattle.

In 1889, Roncalli received both his First Communion and Confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. For adults, it is an affirmation of belief. It involves laying on ...

at the age of 8.

On 1 March 1896, Luigi Isacchi, the spiritual director of his seminary, enrolled him into the Secular Franciscan Order

The Secular Franciscan Order ( la, Ordo Franciscanus Saecularis; abbreviated OFS) is the third branch of the Franciscan Family formed by Catholic Church, Catholic men and women who seek to observe the Gospel of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus by fo ...

. He professed his vows as a member of that order on 23 May 1897.

In 1904, Roncalli completed his doctorate in canon law

Doctor of Canon Law ( la, Juris Canonici Doctor, JCD) is the doctoral-level terminal degree in the studies of canon law of the Roman Catholic Church. It can also be an honorary degree awarded by Anglican colleges. It may also be abbreviated ICD ...

and was ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform va ...

a priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particu ...

in the Catholic Church of Santa Maria in Monte Santo in Piazza del Popolo in Rome on 10 August. Shortly after that, while still in Rome, Roncalli was taken to Saint Peter's Basilica to meet Pope Pius X. After this, he would return to his town to celebrate Mass for the Assumption.

Priesthood

In 1905, Giacomo Radini-Tedeschi, the newBishop of Bergamo

The Diocese of Bergamo ( la, Dioecesis Bergomensis; it, Diocesi di Bergamo; lmo, Diocesi de Bergum) is a Episcopal see, see of the Catholic Church in Italy, and is a suffragan of the Archdiocese of Milan.seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological seminary, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called ''seminarians'') in scripture, theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as clergy, ...

in Bergamo

Bergamo (; lmo, Bèrghem ; from the proto- Germanic elements *''berg +*heim'', the "mountain home") is a city in the alpine Lombardy region of northern Italy, approximately northeast of Milan, and about from Switzerland, the alpine lakes Como ...

.

During World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Roncalli was drafted into the Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army ( it, Regio Esercito, , Royal Army) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfre ...

as a sergeant

Sergeant (abbreviated to Sgt. and capitalized when used as a named person's title) is a rank in many uniformed organizations, principally military and policing forces. The alternative spelling, ''serjeant'', is used in The Rifles and other uni ...

, serving in the medical corps as a stretcher-bearer and as a chaplain

A chaplain is, traditionally, a cleric (such as a Minister (Christianity), minister, priest, pastor, rabbi, purohit, or imam), or a laity, lay representative of a religious tradition, attached to a secularity, secular institution (such as a hosp ...

. After being discharged from the army in early 1919, he was named spiritual director

Spiritual direction is the practice of being with people as they attempt to deepen their relationship with the divine, or to learn and grow in their personal spirituality. The person seeking direction shares stories of their encounters of the di ...

of the seminary. On 7 May 1921, Roncalli was appointed a Domestic Prelate of His Holiness, which gave him the title of ''Monsignor

Monsignor (; it, monsignore ) is an honorific form of address or title for certain male clergy members, usually members of the Roman Catholic Church. Monsignor is the apocopic form of the Italian ''monsignore'', meaning "my lord". "Monsignor" ca ...

''. On 6 November, he travelled to Rome where he was scheduled to meet the Pope. After their meeting, Pope Benedict XV

Pope Benedict XV (Latin: ''Benedictus XV''; it, Benedetto XV), born Giacomo Paolo Giovanni Battista della Chiesa, name=, group= (; 21 November 185422 January 1922), was head of the Catholic Church from 1914 until his death in January 1922. His ...

appointed him as the Italian president of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith

The Society for the Propagation of the Faith (Latin: ''Propagandum Fidei'') is an international association coordinating assistance for Catholic missionary priests, brothers, and nuns in mission areas. The society was founded in Lyon, France, in ...

. Roncalli would recall Benedict XV as being the most sympathetic of the popes he had met.

Episcopate

In February 1925, the Cardinal Secretary of StatePietro Gasparri

Pietro Gasparri, GCTE (5 May 1852 – 18 November 1934) was a Roman Catholic cardinal, diplomat and politician in the Roman Curia and the signatory of the Lateran Pacts. He served also as Cardinal Secretary of State under Popes Benedict XV and ...

summoned him to the Vatican and informed him of Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

's decision to appoint him the Apostolic Visitor

In the Catholic Church, an apostolic visitor (or ''Apostolic Visitator''; Italian: Visitatore apostolico) is a papal representative with a transient mission to perform a canonical visitation of relatively short duration. The visitor is deputed ...

to Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

(1925–1935). On 3 March, Pius XI also appointed him titular archbishop

A titular bishop in various churches is a bishop who is not in charge of a diocese.

By definition, a bishop is an "overseer" of a community of the faithful, so when a priest is ordained a bishop, the tradition of the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox an ...

of Areopolis, Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

. Roncalli was initially reluctant about a mission to Bulgaria, but he soon relented. His nomination as apostolic visitor was made official on 19 March. Roncalli was consecrated a bishop by Giovanni Tacci Porcelli

Giovanni Tacci Porcelli known as Giovanni Tacci (12 November 1863 – 30 June 1928) was an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church who was Bishop of Città della Pieve for twenty years, then a papal ambassador, and finally secretary of the Co ...

in the church of San Carlo al Corso

Sant'Ambrogio e Carlo al Corso (usually known simply as ''San Carlo al Corso'') is a basilica church in Rome, Italy, facing onto the central part of the Via del Corso. The apse of the church faces across the street, the Mausoleum of Augustus o ...

in Rome.

On 30 November 1934, he was appointed Apostolic Delegate to Turkey and Greece and titular archbishop of Mesembria

Mesembria ( grc, Μεσημβρία; grc-x-doric, Μεσαμβρία, Mesambria) was an important Greek city in ancient Thrace. It was situated on the coast of the Euxine and at the foot of Mount Haemus; consequently upon the confines of Moe ...

, Bulgaria. He became known in Turkey's predominantly Muslim society as "the Turcophile

A Turkophile or Turcophile, ( tr, Türksever) is a person who has a strong positive predisposition or sympathy toward the government, culture, history, or people of Turkey. This could include Turkey itself and its history, the Turkish language, Tur ...

Pope". Roncalli took up this post in 1935 and used his office to help the Jewish underground in saving thousands of refugees in Europe, leading some to consider him to be a Righteous Gentile (see Pope John XXIII and Judaism). In October 1935, he led Bulgarian pilgrims to Rome and introduced them to Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI ( it, Pio XI), born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti (; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939), was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 to his death in February 1939. He was the first sovereign of Vatican City fro ...

on 14 October.

In February 1939, he received news from his sisters that his mother was dying. On 10 February 1939, Pope Pius XI died. Roncalli was unable to see his mother for the end as the death of a pontiff meant that he would have to stay at his post until the election of a new pontiff. Unfortunately, she died on 20 February 1939, during the nine days of mourning for the late Pius XI. He was sent a letter by Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, and Roncalli later recalled that it was probably the last letter Pacelli sent until his election as Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

on 2 March 1939. Roncalli expressed happiness that Pacelli was elected, and, on radio, listened to the coronation of the new pontiff. In 1939, Roncalli was made head of the Vatican Jewish Agency in Geneva.

Roncalli remained in Bulgaria at the time that World War II commenced, optimistically writing in his journal in April 1939, "I don't believe we will have a war". At the time that the war did in fact commence, he was in Rome, meeting with Pope Pius XII on 5 September 1939. In 1940, Roncalli was asked by the Vatican to devote more of his time to Greece; therefore, he made several visits there in January and May of that year. The same year, Roncalli departed as head of the Vatican Jewish Agency and migrated to Turkey. However, Roncalli still maintained close relations with the Jews and also intervened to convince Bulgaria's King Boris III

Boris III ( bg, Борѝс III ; Boris Treti; 28 August 1943), originally Boris Klemens Robert Maria Pius Ludwig Stanislaus Xaver (Boris Clement Robert Mary Pius Louis Stanislaus Xavier) , was the Tsar of the Kingdom of Bulgaria from 1918 until h ...

to cancel deportations of Greek Jews during the Nazi occupation of Greece.

Efforts during the Holocaust

As nuncio, Roncalli made various efforts duringThe Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

to save refugees, mostly Jewish people, from the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

. Among his efforts were:

* Delivery of "immigration certificates" to Palestine through the Nunciature diplomatic courier.

* Rescue of Jews by means of certificates of "baptism of convenience" sent by Monsignor Roncalli to priests in Europe.

* Children managed to leave Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the s ...

due to his interventions.

* Jewish refugees whose names were included on a list submitted by Rabbi Markus of Istanbul to Nuncio Roncalli.

* Jews held at Jasenovac concentration camp

Jasenovac () was a concentration camp, concentration and extermination camps, extermination camp established in the Jasenovac, Sisak-Moslavina County, village of the same name by the authorities of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) in I ...

, near Stara Gradiška

Stara Gradiška (, german: Altgradisch) is a village and a municipality in Slavonia, in the Brod-Posavina County of Croatia. It is located on the left bank of the river Sava, across from Gradiška in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Etymology

The first w ...

, were liberated as a result of his intervention.

* Bulgarian Jews who left Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

, a result of his request to King Boris III of Bulgaria.

* Romanian

Romanian may refer to:

*anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Romania

**Romanians, an ethnic group

**Romanian language, a Romance language

***Romanian dialects, variants of the Romanian language

**Romanian cuisine, traditional ...

Jews from Transnistria

Transnistria, officially the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), is an unrecognised breakaway state that is internationally recognised as a part of Moldova. Transnistria controls most of the narrow strip of land between the Dniester riv ...

left Romania as a result of his intervention.

* Italian Jews helped by the Vatican as a result of his interventions.

* Orphaned children of Transnistria

Transnistria, officially the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic (PMR), is an unrecognised breakaway state that is internationally recognised as a part of Moldova. Transnistria controls most of the narrow strip of land between the Dniester riv ...

on board a refugee ship that weighed anchor from Constanța

Constanța (, ; ; rup, Custantsa; bg, Кюстенджа, Kyustendzha, or bg, Констанца, Konstantsa, label=none; el, Κωνστάντζα, Kōnstántza, or el, Κωνστάντια, Kōnstántia, label=none; tr, Köstence), histo ...

to Istanbul, and later arriving in Palestine as a result of his interventions.

* Jews held at the Sereď

Sereď (; hu, Szered ) is a town in southern Slovakia near Trnava, on the right bank of the Váh River on the Danubian Lowland. It has approximately 15,500 inhabitants.

Geography

Sereď lies at an altitude of above mean sea level, above sea l ...

concentration camp who were spared from being deported to German death camps as a result of his intervention.

* Hungarian Jews who saved themselves through their conversions to Christianity through the baptismal certificates sent by Nuncio Roncalli to the Hungarian Nuncio, Monsignor Angelo Rota.

In 1965, the Catholic Herald

The ''Catholic Herald'' is a London-based Roman Catholic monthly newspaper and starting December 2014 a magazine, published in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and, formerly, the United States. It reports a total circulation of abo ...

newspaper quoted Pope John XXIII as saying:

On 7 September 2000, the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation (IRWF) is a non-governmental organization which researches Holocaust rescuers and advocates for their recognition. The organization developed educational programs for school to promote peace and civil s ...

launched the International Campaign for the Acknowledgement of the humanitarian actions undertaken by Vatican Nuncio Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli for people, most of whom were Jewish, persecuted by the Nazi regime. The launching took place at the Permanent Observation Mission of the Vatican to the United Nations, in the presence of Vatican State Secretary Cardinal Angelo Sodano

Angelo Raffaele Sodano, GCC (23 November 1927 – 27 May 2022) was an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church and from 1991 on a cardinal. He was the Dean of the College of Cardinals from 2005 to 2019 and Cardinal Secretary of State from 1991 ...

.

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation has carried out exhaustive historical research related to different events connected with interventions of Nuncio Roncalli in favour of Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. As of September 2000 three reports have been published compiling different studies and materials of historical research about the humanitarian actions carried out by Roncalli when he was nuncio.

In 2011, the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation submitted a massive file (the Roncalli Dossier) to Yad Vashem, with a strong petition and recommendation to bestow upon him the title of

The International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation has carried out exhaustive historical research related to different events connected with interventions of Nuncio Roncalli in favour of Jewish refugees during the Holocaust. As of September 2000 three reports have been published compiling different studies and materials of historical research about the humanitarian actions carried out by Roncalli when he was nuncio.

In 2011, the International Raoul Wallenberg Foundation submitted a massive file (the Roncalli Dossier) to Yad Vashem, with a strong petition and recommendation to bestow upon him the title of Righteous among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sav ...

.

Relations with Israel

After 1944, he played an active role in gaining Catholic Church support for the establishment of theState of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. His support for Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

, and the establishment of Israel was the result of his cultural and religious openness toward other faiths and cultures, and especially concern with the fate of Jews after the war. He was one of the Vatican's most sympathetic diplomats toward Jewish immigration to Palestine, which he saw as a humanitarian issue, and not a matter of biblical theology.

Nuncio

On 22 December 1944, duringWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

named him to be the new Apostolic Nuncio to recently liberated France. In this capacity he had to negotiate the retirement of bishops

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

who had collaborated with the German occupying power.

Roncalli was chosen among several other candidates, one of whom was Archbishop Joseph Fietta. Roncalli met with Domenico Tardini

Domenico Tardini (29 February 1888 – 30 July 1961) was a longtime aide to Pope Pius XII in the Secretariat of State. Pope John XXIII named him Cardinal Secretary of State and, in this position the most prominent member of the Roman Curia in ...

to discuss his new appointment, and their conversation suggested that Tardini did not approve of it. One curial prelate referred to Roncalli as an "old fogey" while speaking with a journalist.

Roncalli left Ankara on 27 December 1944 on a series of short-haul flights that took him to several places, such as Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

, Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

and Naples. He ventured to Rome on 28 December and met with both Tardini and his friend Giovanni Battista Montini

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in Augus ...

. He left for France the next day to commence his newest role.

Cardinal

Carlo Agostini

Carlo Agostini (22 April 1888 – 28 December 1952) was an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church. He served as Patriarch of Venice from 1949 until his death, and died shortly after the announcement for his elevation to the cardinalate in ...

. Furthermore, Montini said to him via letter on 29 November 1952 that Pius XII had decided to raise him to the cardinalate. Roncalli knew that he would be appointed to lead the patriarchy of Venice due to the death of Agostini, who was to have been raised to the rank of cardinal.

On 12 January 1953, he was appointed Patriarch of Venice

The Patriarch of Venice ( la, Patriarcha Venetiarum; it, Patriarca di Venezia) is the ordinary bishop of the Archdiocese of Venice. The bishop is one of the few patriarchs in the Latin Church of the Catholic Church (currently three other Latin ...

and raised to the rank of Cardinal-Priest

A cardinal ( la, Sanctae Romanae Ecclesiae cardinalis, literally 'cardinal of the Holy Roman Church') is a senior member of the clergy of the Catholic Church. Cardinals are created by the ruling pope and typically hold the title for life. Col ...

of Santa Prisca

Santa Prisca is a titular church of Rome, on the Aventine Hill, for Cardinal-priests. It is recorded as the ''Titulus Priscae'' in the acts of the 499 synod.

Church

It is devoted to Saint Prisca, a 1st-century martyr, whose relics are contai ...

by Pope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

. Before departing Paris he invited to dinner the eight men who had served as prime minister during Roncalli's term as nuncio. Roncalli left France for Venice on 23 February 1953 stopping briefly in Milan and then to Rome. On 15 March 1953, he took possession of his new diocese in Venice. As a sign of his esteem, the President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (french: Président de la République française), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency i ...

, Vincent Auriol

Vincent Jules Auriol (; 27 August 1884 – 1 January 1966) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1947 to 1954.

Early life and politics

Auriol was born in Revel, Haute-Garonne, as the only child of Jacques Antoine Aurio ...

, claimed the ancient privilege possessed by French monarchs and bestowed the red biretta on Roncalli at a ceremony in the Élysée Palace

The Élysée Palace (french: Palais de l'Élysée; ) is the official residence of the President of the French Republic. Completed in 1722, it was built for nobleman and army officer Louis Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, who had been appointed Gover ...

. It was around this time that he, with the aid of Monsignor Bruno Heim

Bruno Bernard Heim (5 March 1911 – 18 March 2003) was the Vatican's first Apostolic Nuncio to Britain and was one of the most prominent armorists of twentieth century ecclesiastical heraldry. He published five books on heraldry and was respons ...

, formed his coat of arms with a lion of Saint Mark on a white ground. Auriol also awarded Roncalli three months later with the award of Commander of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

.

Roncalli decided to live on the second floor of the residence reserved for the patriarch, choosing not to live in the first floor room once resided in by Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto, who later became Pope Pius X

Pope Pius X ( it, Pio X; born Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto; 2 June 1835 – 20 August 1914) was head of the Catholic Church from 4 August 1903 to his death in August 1914. Pius X is known for vigorously opposing modernist interpretations of C ...

. On 29 May 1954, the late Pius X was canonized and Roncalli ensured that the late pontiff's patriarchal room was remodelled into a 1903 (the year of the new saint's papal election) look in his honor. With Pius X's few surviving relatives, Roncalli celebrated a Mass in his honor.

His sister Ancilla would soon be diagnosed with stomach cancer in the early 1950s. Roncalli's last letter to her was dated on 8 November 1953 where he promised to visit her within the next week. He could not keep that promise, as Ancilla died on 11 November 1953 at the time when he was consecrating a new church in Venice. He attended her funeral back in his hometown. In his will around this time, he mentioned that he wished to be buried in the crypt of Saint Mark's in Venice with some of his predecessors rather than with the family in Sotto il Monte.

In 1958, he held a diocesan synod.

Papacy

Papal election

Following the death ofPope Pius XII

Pope Pius XII ( it, Pio XII), born Eugenio Maria Giuseppe Giovanni Pacelli (; 2 March 18769 October 1958), was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 2 March 1939 until his death in October 1958. Before his e ...

on 9 October 1958, Roncalli watched the live funeral on his last full day in Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

on 11 October. His journal was specifically concerned with the funeral and the abused state of the late pontiff's corpse. Roncalli left Venice for the conclave in Rome well aware that he was ''papabile'', and after eleven ballots, was elected to succeed the late Pius XII, so it came as no surprise to him, though he had arrived at the Vatican with a return train ticket to Venice.

Many had considered Giovanni Battista Montini

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in Augus ...

, the Archbishop of Milan

The Archdiocese of Milan ( it, Arcidiocesi di Milano; la, Archidioecesis Mediolanensis) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical territory or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in Italy which covers the areas of Milan, Monza, Lecco and Varese. It has l ...

, a possible candidate, but, although he was the archbishop of one of the most ancient and prominent sees in Italy, he had not yet been made a cardinal. Though his absence from the 1958 conclave did not make him ineligible – under Canon Law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

any Catholic male who is capable of receiving priestly ordination and episcopal consecration may be elected – the College of Cardinals

The College of Cardinals, or more formally the Sacred College of Cardinals, is the body of all cardinals of the Catholic Church. its current membership is , of whom are eligible to vote in a conclave to elect a new pope. Cardinals are appoi ...

usually chose the new pontiff from among the Cardinals who attend the papal conclave. At the time, as opposed to modern practice, the participating Cardinals did not have to be below age 80 to vote, there were few Eastern-rite Cardinals, and some Cardinals were just priests at the time of their elevation.

Roncalli was summoned to the final ballot of the conclave at 4:00 pm. He was elected pope at 4:30 pm with a total of 38 votes. After the long pontificate of Pope Pius XII, the cardinals chose a man who – it was presumed because of his advanced age – would be a short-term or "stop-gap" pope. They wished to choose a candidate who would do little during the new pontificate. Upon his election, Cardinal Eugène Tisserant

Eugène-Gabriel-Gervais-Laurent Tisserant (; 24 March 1884 – 21 February 1972) was a French people, French prelate and Cardinal (Catholic Church), cardinal of the Catholic Church. Elevated to the cardinalate in 1936, Tisserant was a prominent ...

asked him the ritual questions of whether he would accept and if so, what name he would take for himself. Roncalli gave the first of his many surprises when he chose "John" as his regnal name

A regnal name, or regnant name or reign name, is the name used by monarchs and popes during their reigns and, subsequently, historically. Since ancient times, some monarchs have chosen to use a different name from their original name when they ac ...

. Roncalli's exact words were "I will be called John". This was the first time in over 500 years that this name had been chosen; previous popes had avoided its use since the time of the Antipope John XXIII

Baldassarre Cossa (c. 1370 – 22 December 1419) was Pisan antipope John XXIII (1410–1415) during the Western Schism. The Catholic Church regards him as an antipope, as he opposed Pope Gregory XII whom the Catholic Church now recognizes as ...

during the Western Schism

The Western Schism, also known as the Papal Schism, the Vatican Standoff, the Great Occidental Schism, or the Schism of 1378 (), was a split within the Catholic Church lasting from 1378 to 1417 in which bishops residing in Rome and Avignon bo ...

several centuries before.

On the choice of his papal name, Pope John XXIII said to the cardinals:

Upon his choosing the name, there was some confusion as to whether he would be known as John XXIII or John XXIV; in response, he declared that he was John XXIII, thus affirming the antipapal status of antipope John XXIII

Baldassarre Cossa (c. 1370 – 22 December 1419) was Pisan antipope John XXIII (1410–1415) during the Western Schism. The Catholic Church regards him as an antipope, as he opposed Pope Gregory XII whom the Catholic Church now recognizes as ...

.

Before this antipope, the most recent popes called John were John XXII

Pope John XXII ( la, Ioannes PP. XXII; 1244 – 4 December 1334), born Jacques Duèze (or d'Euse), was head of the Catholic Church from 7 August 1316 to his death in December 1334.

He was the second and longest-reigning Avignon Pope, elected by ...

(1316–1334) and John XXI (1276–1277). However, there was no Pope John XX

The numbering of "popes John" does not occur in strict numerical order. Although there have been twenty-one legitimate popes named John, the numbering has reached John XXIII because of two clerical errors that were introduced in the Middle Ages: f ...

, owing to confusion caused by medieval historians misreading the Liber Pontificalis

The ''Liber Pontificalis'' (Latin for 'pontifical book' or ''Book of the Popes'') is a book of biographies of popes from Saint Peter until the 15th century. The original publication of the ''Liber Pontificalis'' stopped with Pope Adrian II (867� ...

to refer to another Pope John between John XIV and John XV.

After his election, he confided in Cardinal Maurice Feltin

Maurice Feltin (15 May 1883 – 27 September 1975) was a French Cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as Archbishop of Paris from 1949 to 1966, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1953 by Pope Pius XII.

Biography

Born in Delle, ...

that he had chosen the name "in memory of France and in the memory of John XXII who continued the history of the papacy in France".

After he answered the two ritual questions, the traditional Habemus Papam announcement was delivered by Cardinal Nicola Canali

Nicola Canali (6 June 1874 – 3 August 1961) was an Italian cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church. He served as president of the Pontifical Commission for Vatican City State from 1939 and as Major Penitentiary from 1941 until his death, and wa ...

to the people at 6:08 pm, an exact hour after the white smoke appeared. A short while later, he appeared on the balcony and gave his first Urbi et Orbi

''Urbi et Orbi'' ('to the city f Romeand to the world') denotes a papal address and apostolic blessing given by the pope on certain solemn occasions.

Etymology

The term ''Urbi et Orbi'' evolved from the consciousness of the ancient Roman Empir ...

blessing to the crowds of the faithful below in Saint Peter's Square

Saint Peter's Square ( la, Forum Sancti Petri, it, Piazza San Pietro ,) is a large plaza located directly in front of St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, the papal enclave inside Rome, directly west of the neighborhood (rione) of Borgo. Bot ...

. That same night, he appointed Domenico Tardini

Domenico Tardini (29 February 1888 – 30 July 1961) was a longtime aide to Pope Pius XII in the Secretariat of State. Pope John XXIII named him Cardinal Secretary of State and, in this position the most prominent member of the Roman Curia in ...

as his Secretary of State. Of the three cassocks prepared for whomever the new pope was, even the largest was not enough to fit his five-foot-two, 200-plus-pound frame, which had to be let out in certain places and only to be held together with great effort by bobby pins. When he first saw himself in the mirror in his new vestments, he said with an apprising and critical look that "this man will be a disaster on television!", while later saying he felt his first appearance before the globe was as if he were a "newborn babe in swaddling clothes".

His coronation took place on 4 November 1958, on the feast of Saint Charles Borromeo

Charles Borromeo ( it, Carlo Borromeo; la, Carolus Borromeus; 2 October 1538 – 3 November 1584) was the Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584 and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. He was a leading figure of the Counter-Reformation combat a ...

, and it occurred on the central loggia of the Vatican. He was crowned with the 1877 Palatine Tiara

The papal tiara is the crown worn by popes of the Catholic Church for centuries, until 1978 when Pope John Paul I declined a coronation, opting instead for an inauguration. The tiara is still used as a symbol of the papacy. It features on the coat ...

. His coronation ran for the traditional five hours.

In John XXIII's first consistory

Consistory is the anglicized form of the consistorium, a council of the closest advisors of the Roman emperors. It can also refer to:

*A papal consistory, a formal meeting of the Sacred College of Cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church

*Consistory ...

on 15 December of that same year, Montini was created a cardinal and would become John XXIII's successor in 1963, taking the name of Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his ...

. That consistory was notable for being the first to expand the Sacred College membership beyond the then-traditional 70.

Following his election the new pope told the tale of how in his first weeks he was walking when he heard a woman exclaim in a loud voice: "My God, he's so fat!" The new pope casually remarked: "Madame, the holy conclave isn't exactly a beauty contest!"

Visits around Rome

On 25 December 1958, he became the first pope since 1870 to make pastoral visits in his

On 25 December 1958, he became the first pope since 1870 to make pastoral visits in his Diocese of Rome

The Diocese of Rome ( la, Dioecesis Urbis seu Romana; it, Diocesi di Roma) is the ecclesiastical district under the direct jurisdiction of the Pope, who is Bishop of Rome and hence the supreme pontiff and head of the worldwide Catholic Church. ...

, when he visited children infected with polio

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe s ...

at the Bambino Gesù Hospital

Ospedale Pediatrico Bambino Gesù (''Baby Jesus Paediatric Hospital'') is a tertiary care academic children's hospital located in Rome that is under extraterritorial jurisdiction of the Holy See. As a tertiary children referral centre, the hosp ...

and then visited Santo Spirito Hospital. The following day, he visited Rome's Regina Coeli prison

Regina Coeli (; it, Carcere di Regina Coeli ) is the best known prison in the city of Rome. Previously a Catholic convent (hence the name), it was built in 1654 in the rione of Trastevere. It started to serve as a prison in 1881.

The constructi ...

, where he told the inmates: "You could not come to me, so I came to you." These gestures created a sensation, and he wrote in his diary: "... great astonishment in the Roman, Italian and international press. I was hemmed in on all sides: authorities, photographers, prisoners, warders..."

During these visits, John XXIII put aside the normal papal use of the formal "we" when referring to himself, such as when he visited a reformatory school for juvenile delinquents in Rome telling them "I have wanted to come here for some time". The media noticed this and reported that "He talked to the youths in their own language".

"Ostpolitik" and Eastern Europe

In international affairs, his "Ostpolitik" Eastern policy"engaged in dialogue with the Communist countries of Eastern Europe. He worked to reconcile the Vatican with theRussian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

to settle tensions between the local churches. The Second Vatican Council did not condemn Communism and did not even mention it, in what some have called a secret agreement between the Holy See and the Soviet Union. In ''Pacem in terris

''Pacem in terris'' () was a papal encyclical issued by Pope John XXIII on 11 April 1963 on the rights and obligations of individuals and of the state, as well as the proper relations between states. It emphasized human dignity and equality a ...

'', John XXIII also sought to prevent nuclear war and tried to improve relations between the Soviet Union and the United States. He began a policy of dialogue with Soviet leaders in order to seek conditions in which Eastern Catholics could find relief from persecution.

Relations with Jews

One of the first acts of Pope John XXIII, in 1960, was to eliminate the description of Jews as ''perfidius'' (Latin for "perfidious" or "faithless") in the prayer for theconversion of the Jews

Many Christians believe in a widespread conversion of the Jews to Christianity, which they often consider as an end-time event. Some Christian denominations consider the conversion of the Jews imperative and pressing, and as a result they make i ...

in the Good Friday liturgy. He interrupted the first Good Friday liturgy in his pontificate to address this issue when he first heard a celebrant refer to the Jews with that word. He also made a confession for the Church of the sin of anti-semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

through the centuries.

While Vatican II was being held, John XXIII tasked Cardinal Augustin Bea

Augustin Bea, S.J. (28 May 1881 – 16 November 1968), was a German Jesuit priest, cardinal, and scholar at the Pontifical Gregorian University, specialising in biblical studies and biblical archaeology. He also served as the personal confessor ...

with the creation of several important documents that pertained to reconciliation with Jewish people.

Calling the Council

Far from being a mere "stopgap" pope, to great excitement, John XXIII called for an

Far from being a mere "stopgap" pope, to great excitement, John XXIII called for an ecumenical council

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote are ...

fewer than ninety years after the First Vatican Council

The First Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the First Vatican Council or Vatican I was convoked by Pope Pius IX on 29 June 1868, after a period of planning and preparation that began on 6 December 1864. This, the twentieth ecu ...

(Vatican I's predecessor, the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

, had been held in the 16th century). This decision was announced on 25 January 1959 at the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls

The Papal Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls ( it, Basilica Papale di San Paolo fuori le Mura), commonly known as Saint Paul's Outside the Walls, is one of Rome's four major papal basilicas, along with the basilicas of Saint John in the ...

. Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, who later became Pope Paul VI, remarked to Giulio Bevilacqua

Giulio Bevilacqua, Orat (14 November 1881 – 6 May 1965) was an Italian prelate of the Catholic Church who devoted himself to pastoral work in Brescia and served as a military chaplain, known for his opposition to fascism. A few weeks before h ...

that "this holy old boy doesn't realise what a hornet's nest he's stirring up". From the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

came changes that reshaped the face of Catholicism: a comprehensively revised liturgy, a stronger emphasis on ecumenism

Ecumenism (), also spelled oecumenism, is the concept and principle that Christians who belong to different Christian denominations should work together to develop closer relationships among their churches and promote Christian unity. The adjec ...

, and a new approach to the world.

Prior to the first session of the council, John XXIII visited Assisi

Assisi (, also , ; from la, Asisium) is a town and ''comune'' of Italy in the Province of Perugia in the Umbria region, on the western flank of Monte Subasio.

It is generally regarded as the birthplace of the Latin poet Propertius, born aroun ...

and Loreto on 4 October 1962 to pray for the new upcoming council as well as to mark the feast day of St. Francis of Assisi

Giovanni di Pietro di Bernardone, better known as Saint Francis of Assisi ( it, Francesco d'Assisi; – 3 October 1226), was a mystic Italian Catholic friar, founder of the Franciscans, and one of the most venerated figures in Christianit ...

. He was the first pope to travel outside of Rome since Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

. Along the way, there were several halts at Orte, Narni, Terni, Spoleto

Spoleto (, also , , ; la, Spoletum) is an ancient city in the Italian province of Perugia in east-central Umbria on a foothill of the Apennines. It is S. of Trevi, N. of Terni, SE of Perugia; SE of Florence; and N of Rome.

History

Spolet ...

, Foligno, Fabriano, Iesi

Jesi, also spelled Iesi (), is a town and ''comune'' of the province of Ancona in Marche, Italy.

It is an important industrial and artistic center in the floodplain on the left (north) bank of the Esino river before its mouth on the Adriatic ...

, Falconara and Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

where the crowds greeted him.

Moral theology

Contraception

In 1963, John XXIII established a commission of six non-theologians to investigate questions of birth control.Human rights

John XXIII was an advocate for human rights which included the unborn and the elderly. He wrote about human rights in his encyclical ''Pacem in terris

''Pacem in terris'' () was a papal encyclical issued by Pope John XXIII on 11 April 1963 on the rights and obligations of individuals and of the state, as well as the proper relations between states. It emphasized human dignity and equality a ...

''. He wrote, "Man has the right to live. He has the right to bodily integrity and to the means necessary for the proper development of life, particularly food, clothing, shelter, medical care, rest, and, finally, the necessary social services. In consequence, he has the right to be looked after in the event of ill health; disability stemming from his work; widowhood; old age; enforced unemployment; or whenever through no fault of his own he is deprived of the means of livelihood."

Divorce

John XXIII said that human life is transmitted through the family which is founded on the sacrament of marriage and is both one and indissoluble as a union in God, therefore, it is against the teachings of the Church for a married couple todivorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

.''Mater et magistra'', 193

Pope John XXIII and papal ceremonial

Pope John XXIII was the last pope to use full papal ceremony, some of which was abolished afterVatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions), each lasting between 8 and 1 ...

, while the rest fell into disuse. His papal coronation

A papal coronation is the formal ceremony of the placing of the papal tiara on a newly elected pope. The first recorded papal coronation was of Pope Nicholas I in 858. The most recent was the 1963 coronation of Paul VI, who soon afterwards aband ...

ran for the traditional five hours (Pope Paul VI, by contrast, opted for a shorter ceremony, while later popes declined to be crowned). Pope John XXIII, like his predecessor Pius XII, chose to have the coronation itself take place on the balcony of Saint Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

, in view of the crowds assembled in Saint Peter's Square

Saint Peter's Square ( la, Forum Sancti Petri, it, Piazza San Pietro ,) is a large plaza located directly in front of St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City, the papal enclave inside Rome, directly west of the neighborhood (rione) of Borgo. Bot ...

below.

He wore a number of papal tiaras during his papacy. On the most formal of occasions would he don the 1877 Palatine tiara he received at his coronation, but on other occasions, he used the 1922 tiara of Pope Pius XI, which was used so often that it was associated with him quite strongly. The people of Bergamo gave him an expensive silver tiara

A tiara (from la, tiara, from grc, τιάρα) is a jeweled head ornament. Its origins date back to ancient Greece and Rome. In the late 18th century, the tiara came into fashion in Europe as a prestigious piece of jewelry to be worn by women ...

, but he requested that the number of jewels used be halved and that the money be given to the poor.

Liturgical reform

Maintaining continuity with his predecessors, John XXIII continued the gradual reform of the Roman liturgy, and published changes that resulted in the1962 Roman Missal

The Tridentine Mass, also known as the Traditional Latin Mass or Traditional Rite, is the liturgy of Mass in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church that appears in typical editions of the Roman Missal published from 1570 to 1962. Celebrated almo ...

, the last typical edition containing the Tridentine Mass

The Tridentine Mass, also known as the Traditional Latin Mass or Traditional Rite, is the liturgy of Mass in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church that appears in typical editions of the Roman Missal published from 1570 to 1962. Celebrated almo ...

established in 1570 by Pope Pius V

Pope Pius V ( it, Pio V; 17 January 1504 – 1 May 1572), born Antonio Ghislieri (from 1518 called Michele Ghislieri, O.P.), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 January 1566 to his death in May 1572. He is v ...

at the request of the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

.

Beatifications and canonization ceremonies

John XXIII beatified four individuals in his reign:

John XXIII beatified four individuals in his reign: Elena Guerra

Elena Guerra (23 June 1835 – 11 April 1914) was an Italian Roman Catholic religious sister and the founder of the Oblates of the Holy Spirit. Guerra was a strong proponent on the Holy Spirit as a motivation to do pious works. She was known to ...

(26 April 1959), Innocenzo da Berzo

Innocenzo da Berzo (19 March 1844 - 3 March 1890), born Giovanni Scalvinoni, was an Italian Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic priest and a professed member of the Order of Friars Minor - or Capuchin branch of the Franciscan Order. Scalvinoni ...

(12 November 1961), Elizabeth Ann Seton

Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton (August 28, 1774 – January 4, 1821) was a Catholic religious sister in the United States and an educator, known as a founder of the country's parochial school system. After her death, she became the first person bo ...

(17 March 1963) and Luigi Maria Palazzolo

Luigi Maria Palazzolo (10 December 1827 – 15 June 1886) was an Italian Roman Catholic priest. He established the Sisters of the Poor which was also known as the Palazzolo Institute. Other contributions include the construction of an orphanage ...

(19 March 1963).

He also canonized a small number of individuals: he canonized Charles of Sezze

Charles of Sezze (19 October 1613 – 6 January 1670) - born Giancarlo Marchioni - was an Italian professed religious from the Order of Friars Minor. He became a religious despite the opposition of his parents who wanted him to become a priest a ...

and Joaquina Vedruna de Mas

Joaquina Vedruna de Mas (or Joaquima in Catalan) (16 April 1783 – 28 August 1854) - born Joaquima de Vedruna Vidal de Mas and in religious Joaquina of Saint Francis of Assisi - was a Spanish professed religious and the founder of the Car ...

on 12 April 1959, Gregorio Barbarigo

Gregorio Giovanni Gaspare Barbarigo (16 September 1625 – 18 June 1697) was an Italian people, Italian Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Cardinal (Catholic), cardinal who served as the Bishop of Bergamo and later as the Bishop of Padua. ...

on 26 May 1960, Juan de Ribera

Juan de Ribera (Seville, Spain, 20 March 1532 – Valencia, 6 January 1611) was an influential figure in 16th and 17th century Spain. Ribera held appointments as Archbishop and Viceroy of Valencia, Latin Patriarchate of Antioch, Commander in ...

on 12 June 1960, Maria Bertilla Boscardin

Maria Bertilla Boscardin (6 October 1888 – 20 October 1922) was an Italian nun and nurse who displayed a pronounced devotion to duty in working with sick children and victims of the air raids of World War I. She was later canonised a saint b ...

on 11 May 1961, Martin de Porres

Martín de Porres Velázquez (9 December 1579 – 3 November 1639) was a Peruvian lay brother of the Dominican Order who was beatified in 1837 by Pope Gregory XVI and canonized in 1962 by Pope John XXIII. He is the patron saint of mixed-r ...

on 6 May 1962, and Antonio Maria Pucci, Francis Mary of Camporosso and Peter Julian Eymard

Peter Julian Eymard ( ; 4 February 1811 – 1 August 1868) was a French Catholic priest and founder of two religious institutes: the Congregation of the Blessed Sacrament for men and the Servants of the Blessed Sacrament for women.

Eymard ente ...

on 9 December 1962. His final canonization was that of Vincent Pallotti

Vincent Pallotti (21 April 1795 – 22 January 1850) was an Italian ecclesiastic and a saint. Born in Rome, he was the founder of the Society of the Catholic Apostolate later to be known as the "Pious Society of Missions" (the Pallottines). The ...

on 20 January 1963.

Doctor of the Church

John XXIII proclaimed Saint Lawrence of Brindisi as aDoctor of the Church

Doctor of the Church (Latin: ''doctor'' "teacher"), also referred to as Doctor of the Universal Church (Latin: ''Doctor Ecclesiae Universalis''), is a title given by the Catholic Church to saints recognized as having made a significant contribu ...

on 19 March 1959 and conferred upon him the title "''Doctor apostolicus''" ("Apostolic Doctor").

Consistories

The pope created 52 cardinals in five consistories, including his successor who would become Pope Paul VI. John XXIII decided to expand the size of the College of Cardinals beyond its limit of seventy thatPope Sixtus V

Pope Sixtus V ( it, Sisto V; 13 December 1521 – 27 August 1590), born Felice Piergentile, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 24 April 1585 to his death in August 1590. As a youth, he joined the Franciscan order ...

established in 1586. The pope also reserved three additional cardinals "''in pectore

''In pectore'' (Latin for "in the breast/heart") is a term used in the Catholic Church for an action, decision, or document which is meant to be kept secret. It is most often used when there is a papal appointment to the College of Cardinals wit ...

''" in 1960 which meant he secretly named cardinals without revealing their identities. The pope died before he could reveal these names, therefore meaning that these appointments were never legitimized. John XXIII also sought to further internationalize the College of Cardinals like Pius XII attempted, while also naming the first ever cardinals from countries such as Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

(Peter Doi

Peter Tatsuo Doi (土井 辰雄 ''Doi Tatsuo'') (22 December 1892 – 21 February 1970) was a Japanese Cardinal of the Catholic Church. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2002) "Doi Tatsuo"in ''Japan Encyclopedia,'' p. 157. He served as Archbishop of T ...

) and Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

(Laurean Rugambwa

Laurean Rugambwa (July 12, 1912 – December 8, 1997) was the first modern native African Cardinal of the Catholic Church. He served as Archbishop of Dar es Salaam from 1968 to 1992, and was elevated to the cardinalate in 1960.

Biography

Laurea ...

). Unlike his predecessor, John XXIII held frequent consistories in a marked departure from Pius XII, returning to the frequency seen in the earlier 20th century.

John XXIII also issued a rule in 1962 mandating that all cardinals should be bishops; he himself ordained as bishops the twelve non-bishop cardinals in April 1962.

According to a June 2007 interview, Loris Francesco Capovilla revealed that Francesco Giuseppe Lardone was one of the cardinals that John XXIII had reserved ''in pectore'' in 1960. According to Capovilla, Lardone's precarious position in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

meant that he would have to abandon his position if he were named to the cardinalate. Lardone was of the opinion that he could assist bishops in the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

from his posting which he would be unable to do if he was relocated to accept a position in Rome. In November 1960, in preparation for the next consistory, John XXIII offered the cardinalate to Diego Venini who declined the offer.

Vatican II: The first session

On 11 October 1962, the first session of the

On 11 October 1962, the first session of the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

was held in the Vatican. He gave the Gaudet Mater Ecclesia

''Gaudet Mater Ecclesia'' (Latin for "Mother Church Rejoices") is John XXIII's opening speech of the Second Vatican Council.

Pope John opened the council by this speech on October 11, 1962.

In the speech, he rejected the thoughts of "prophets of ...

speech, which served as the opening address for the council. The day consisted of electing members for several council commissions that would work on the issues presented in the council. On the night following the conclusion of the first session, the people in Saint Peter's Square chanted and yelled with the objective of having John XXIII appear at the window to address them.

Pope John XXIII appeared at the window and delivered a speech to the people below, and told them to return home and hug their children, telling them that the hug came from the pope. This speech would later become known as the so-called 'Speech of the Moon'.

The first session ended in a solemn ceremony on 8 December 1962 with the next session scheduled to occur in 1963 from 12 May to 29 June – this was announced on 12 November 1962. John XXIII's closing speech made subtle references to Pope Pius IX

Pope Pius IX ( it, Pio IX, ''Pio Nono''; born Giovanni Maria Mastai Ferretti; 13 May 1792 – 7 February 1878) was head of the Catholic Church from 1846 to 1878, the longest verified papal reign. He was notable for convoking the First Vatican ...

, and he had expressed the desire to see Pius IX beatified and eventually canonized. In his journal in 1959 during a spiritual retreat, John XXIII made this remark: "I always think of Pius IX of holy and glorious memory, and by imitating him in his sacrifices, I would like to be worthy to celebrate his canonization".

Final months and death

On 23 September 1962, Pope John XXIII was diagnosed with