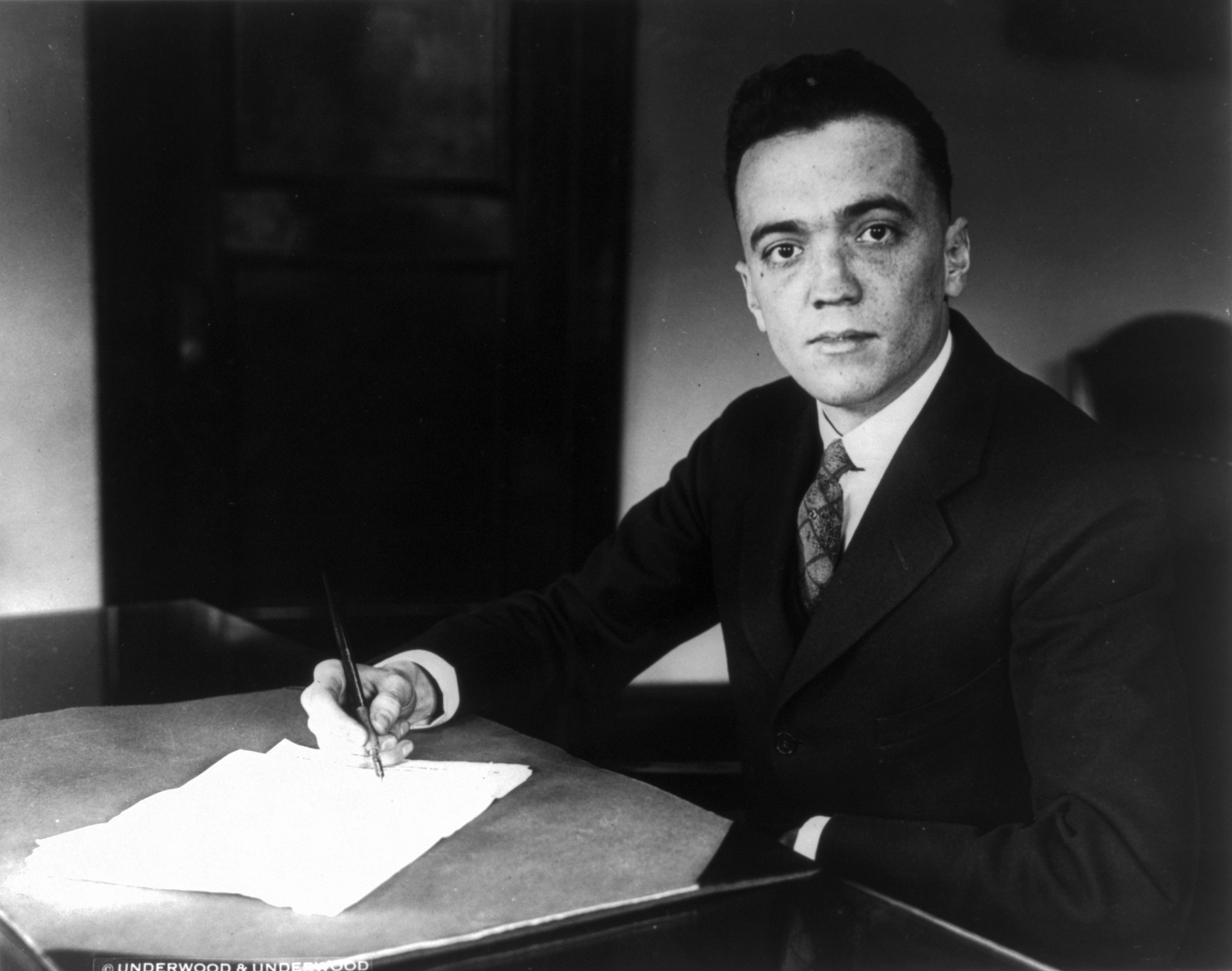

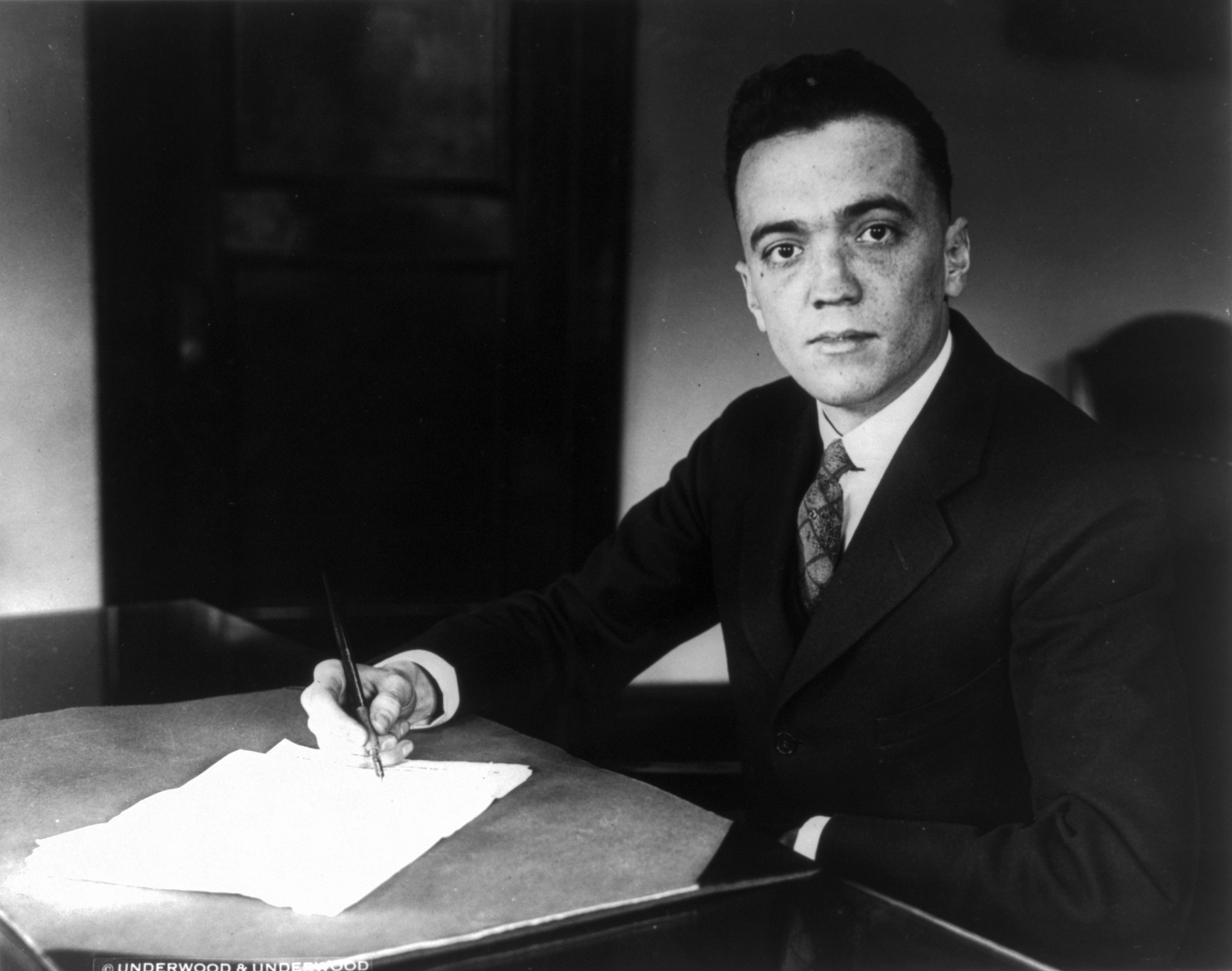

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first

Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the

Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

– the FBI's predecessor – in 1924 and was instrumental in founding the

FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

in 1935, where he remained director for another 37 years until his death in 1972. Hoover built the FBI into a larger crime-fighting agency than it was at its inception and instituted a number of modernizations to police technology, such as a centralized

fingerprint

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surfa ...

file and

forensic

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to criminal and civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standards of admissible evidence and crimin ...

laboratories. Hoover also established and expanded a national blacklist, referred to as the

FBI Index

The FBI Indexes, or Index List, was a system used to track American citizens and other people by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) before the adoption of computerized databases. The Index List was originally made of paper index cards, firs ...

or Index List.

Later in life and after his death, Hoover became a controversial figure as evidence of his secretive

abuses of power began to surface. He was found to have routinely violated the very laws the FBI was charged with enforcing, to have used the FBI to harass

political dissident

A dissident is a person who actively challenges an established political or religious system, doctrine, belief, policy, or institution. In a religious context, the word has been used since the 18th century, and in the political sense since the 20 ...

s, to amass secret files for

blackmail

Blackmail is an act of coercion using the threat of revealing or publicizing either substantially true or false information about a person or people unless certain demands are met. It is often damaging information, and it may be revealed to f ...

ing high-level politicians, and to collect evidence using

vigilantism

Vigilantism () is the act of preventing, investigating and punishing perceived offenses and crimes without legal authority.

A vigilante (from Spanish, Italian and Portuguese “vigilante”, which means "sentinel" or "watcher") is a person who ...

and many other illegal methods.

[

] Hoover consequently amassed a great deal of power and was in a position to intimidate and threaten others.

[

]

Early life and education

John Edgar Hoover was born on

New Year's Day

New Year's Day is a festival observed in most of the world on 1 January, the first day of the year in the modern Gregorian calendar. 1 January is also New Year's Day on the Julian calendar, but this is not the same day as the Gregorian one. Wh ...

1895 in

Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, to Anna Marie (''née'' Scheitlin; 1860–1938) and Dickerson Naylor Hoover (1856–1921), chief of the printing division of the

U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey

The National Geodetic Survey (NGS) is a United States federal agency that defines and manages a national coordinate system, providing the foundation for transportation and communication; mapping and charting; and a large number of applications ...

, formerly a plate maker for the same organization. Dickerson Hoover was of

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national id ...

and

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

ancestry. Hoover's maternal great-uncle, John Hitz, was a

Swiss

Swiss may refer to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Places

* Swiss, Missouri

*Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss-system tournament, in various games and sports

*Swiss Internati ...

honorary

consul general

A consul is an official representative of the government of one state in the territory of another, normally acting to assist and protect the citizens of the consul's own country, as well as to facilitate trade and friendship between the people ...

to the United States.

[Hoover had 7 Children

] Among his family, he was the closest to his mother, who was their moral guide and disciplinarian.

Hoover was born in a house on the present site of Capitol Hill United Methodist Church, located on

Seward Square near

Eastern Market in Washington's

Capitol Hill

Capitol Hill, in addition to being a metonym for the United States Congress, is the largest historic residential neighborhood in Washington, D.C., stretching easterly in front of the United States Capitol along wide avenues. It is one of the ...

neighborhood. A stained glass window in the church is dedicated to him. Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed upon his birth, although it was required in 1895 in Washington. Two of his siblings did have certificates, but Hoover's was not filed until 1938 when he was 43.

Hoover lived his entire life in Washington, D.C. He attended

Central High School, where he sang in the school choir, participated in the

Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all ...

program, and competed on the debate team.

During debates, he argued against women getting the right to vote and against the abolition of the death penalty. The school newspaper applauded his "cool, relentless logic."

[ Hoover ]stutter

Stuttering, also known as stammering, is a speech disorder in which the flow of speech is disrupted by involuntary repetitions and prolongations of sounds, syllables, words, or phrases as well as involuntary silent pauses or blocks in which the ...

ed as a boy, which he later learned to manage by teaching himself to talk quickly—a style that he carried through his adult career. He eventually spoke with such ferocious speed that stenographers had a hard time following him.

Hoover was 18 years old when he accepted his first job, an entry-level position as messenger in the orders department at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The librar ...

. The library was a half mile from his house. The experience shaped both Hoover and the creation of the FBI profiles; as Hoover noted in a 1951 letter: "This job ... trained me in the value of collating material. It gave me an excellent foundation for my work in the FBI where it has been necessary to collate information and evidence."

Hoover obtained a Bachelor of Laws

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of ...

from the George Washington University Law School

The George Washington University Law School (GW Law) is the law school of George Washington University, in Washington, D.C. Established in 1865, GW Law is the oldest top law school in the national capital. GW Law offers the largest range of co ...

in 1916, where he was a member of the Alpha Nu Chapter of the Kappa Alpha Order

Kappa Alpha Order (), commonly known as Kappa Alpha or simply KA, is a social Fraternities and sororities, fraternity and a fraternal order founded in 1865 at Washington and Lee University, Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) i ...

, and an LL.M.

A Master of Laws (M.L. or LL.M.; Latin: ' or ') is an advanced postgraduate academic degree, pursued by those either holding an undergraduate academic law degree, a professional law degree, or an undergraduate degree in a related subject. In mos ...

in 1917 from the same university. While a law student, Hoover became interested in the career of Anthony Comstock

Anthony Comstock (March 7, 1844 – September 21, 1915) was an anti-vice activist, United States Postal Inspector, and secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV), who was dedicated to upholding Christian morality. He o ...

, the New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

U.S. Postal Inspector, who waged prolonged campaigns against fraud

In law, fraud is intentional deception to secure unfair or unlawful gain, or to deprive a victim of a legal right. Fraud can violate civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrator to avoid the fraud or recover monetary compen ...

, vice

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or Habit (psychology), habit generally considered immorality, immoral, sinful, crime, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refe ...

, pornography

Pornography (often shortened to porn or porno) is the portrayal of sexual subject matter for the exclusive purpose of sexual arousal. Primarily intended for adults, , and birth control.[

]

Department of Justice

War Emergency Division

Immediately after getting his LL.M.

A Master of Laws (M.L. or LL.M.; Latin: ' or ') is an advanced postgraduate academic degree, pursued by those either holding an undergraduate academic law degree, a professional law degree, or an undergraduate degree in a related subject. In mos ...

degree, Hoover was hired by the Justice Department

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

to work in the War Emergency Division.[

] He accepted the clerkship on July 27, 1917, aged 22. The job paid $990 a year ($ in dollars) and was exempt from the draft.Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of P ...

at the beginning of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

to arrest and jail allegedly disloyal foreigners without trial.[ He received additional authority from the ]1917 Espionage Act

The Espionage Act of 1917 is a United States federal law enacted on June 15, 1917, shortly after the United States entered World War I. It has been amended numerous times over the years. It was originally found in Title 50 of the U.S. Code (War ...

. Out of a list of 1,400 suspicious Germans living in the U.S., the Bureau arrested 98 and designated 1,172 as arrestable.[

]

Bureau of Investigation

Head of the Radical Division

In August 1919, the 24-year-old Hoover became head of the Bureau of Investigation's new General Intelligence Division, also known as the Radical Division because its goal was to monitor and disrupt the work of domestic radicals.[

] America's First Red Scare

The First Red Scare was a period during the early 20th-century history of the United States marked by a widespread fear of far-left movements, including Bolshevism and anarchism, due to real and imagined events; real events included the Ru ...

was beginning, and one of Hoover's first assignments was to carry out the Palmer Raids

The Palmer Raids were a series of raids conducted in November 1919 and January 1920 by the United States Department of Justice under the administration of President Woodrow Wilson to capture and arrest suspected socialists, especially anarchists ...

.[

]

Hoover and his chosen assistant, George Ruch, monitored a variety of U.S. radicals with the intent to punish, arrest, or deport those whose politics they decided were dangerous. Targets during this period included Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Sr. (17 August 188710 June 1940) was a Jamaican political activist, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African ...

;[

] Rose Pastor Stokes

Rose Harriet Pastor Stokes (née Wieslander; July 18, 1879 – June 20, 1933) was an American socialist activist, writer, birth control advocate, and feminist. She was a figure of some public notoriety after her 1905 marriage to Episcopalian mi ...

and Cyril Briggs

Cyril Valentine Briggs (May 28, 1888 – October 18, 1966) was an African-Caribbean American writer and communist political activist. Briggs is best remembered as founder and editor of ''The Crusader,'' a seminal New York magazine of the New Ne ...

;[

] Emma Goldman

Emma Goldman (June 27, 1869 – May 14, 1940) was a Russian-born anarchist political activist and writer. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of th ...

and Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

Be ...

;[

] and future Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judi ...

, who, Hoover maintained, was "the most dangerous man in the United States."[

]

In 1920 the 25 year-old Edgar Hoover was initiated as a Freemason at D.C.'s Federal Lodge No. 1 in Washington D.C. He went on to join the Scottish Rite

The Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry (the Northern Masonic Jurisdiction in the United States often omits the ''and'', while the English Constitution in the United Kingdom omits the ''Scottish''), commonly known as simply the S ...

in which he was made a 33rd Degree Inspector General Honorary in 1955.

Head of the Bureau of Investigation

In 1921, Hoover rose in the Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, t ...

to deputy head, and in 1924 the Attorney General made him the acting director. On May 10, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States from 1923 to 1929. Born in Vermont, Coolidge was a Republican lawyer from New England who climbed up the ladder of Ma ...

appointed Hoover as the fifth Director of the Bureau of Investigation, partly in response to allegations that the prior director, William J. Burns, was involved in the Teapot Dome scandal

The Teapot Dome scandal was a bribery scandal involving the administration of United States President Warren G. Harding from 1921 to 1923. Secretary of the Interior Albert Bacon Fall had leased Navy petroleum reserves at Teapot Dome in Wy ...

. When Hoover took over the Bureau of Investigation, it had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents.

Hoover fired all female agents and banned the future hiring of them.

Early leadership

Hoover was sometimes unpredictable in his leadership. He frequently fired Bureau agents, singling out those he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers," or whom he considered "pinheads." He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations.

Hoover was sometimes unpredictable in his leadership. He frequently fired Bureau agents, singling out those he thought "looked stupid like truck drivers," or whom he considered "pinheads." He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations. Melvin Purvis

Melvin Horace Purvis II (October 24, 1903 – February 29, 1960) was an American law enforcement official and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent. Given the nickname "Little Mel" because of his short, frame, Purvis became noted for leadi ...

was a prime example: Purvis was one of the most effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs, and it is alleged that Hoover maneuvered him out of the Bureau because he was envious of the substantial public recognition Purvis received.

Hoover often praised local law-enforcement officers around the country, and built up a national network of supporters and admirers in the process. One whom he often commended for particular effectiveness was the conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

sheriff of Caddo Parish, Louisiana

Caddo Parish (French: ''Paroisse de Caddo'') is a parish located in the northwest corner of the U.S. state of Louisiana. According to the 2020 U.S. census, the parish had a population of 237,848. The parish seat is Shreveport, which developed ...

, J. Howell Flournoy.

In December 1929, Hoover oversaw the protection detail for the Japanese Naval Delegation who were visiting Washington, D.C., on their way to attend negotiations for the 1930 London Naval Treaty (officially called Treaty for the Limitation and Reduction of Naval Armament). The Japanese delegation was greeted at Washington Union (train) Station by U.S. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson and the Japanese Ambassador Katsuji Debuchi. The Japanese delegation then visited the White House to meet with President Herbert Hoover.

Name change

In 1933, Hoover learned of a namesake, John Edgar Hoover, who had failed to pay a debt of $900 to a store in Washington. As Hoover was particular about paying his bills on time and so did not want to be associated with this disreputable behavior, he changed his name to "J. Edgar Hoover".

Depression-era gangsters

In the early 1930s, criminal gangs carried out large numbers of bank robberies

Bank robbery is the criminal act of stealing from a bank, specifically while bank employees and customers are subjected to force, violence, or a threat of violence. This refers to robbery of a bank branch or teller, as opposed to other bank-ow ...

in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of the United States. ...

. They used their superior firepower and fast getaway cars to elude local law enforcement agencies and avoid arrest. Many of these criminals frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States, particularly John Dillinger

John Herbert Dillinger (June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934) was an American gangster during the Great Depression. He led the Dillinger Gang, which was accused of robbing 24 banks and four police stations. Dillinger was imprisoned several times and ...

, who became famous for leaping over bank cages, and repeatedly escaping from jails

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, correcti ...

and police

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest a ...

traps. The gangsters enjoyed a level of sympathy in the Midwest, as banks and bankers were widely seen as oppressors of common people during the Great Depression.

The robbers operated across state lines, and Hoover pressed to have their crimes recognized as federal offenses so that he and his men would have the authority to pursue them and get the credit for capturing them. Initially, the Bureau suffered some embarrassing foul-ups, in particular with Dillinger and his conspirators. A raid on a summer lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin, called " Little Bohemia," left a Bureau agent and a civilian bystander dead and others wounded; all the gangsters escaped.

Hoover realized that his job was then on the line, and he pulled out all stops to capture the culprits. In late July 1934, Special Agent Melvin Purvis, the Director of Operations in the Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

office, received a tip on Dillinger's whereabouts that paid off when Dillinger was located, ambushed, and killed by Bureau agents outside the Biograph Theater

The Biograph Theater on Lincoln Avenue in the Lincoln Park neighborhood of Chicago, Illinois, was originally a movie theater but now presents live productions. It gained early notoriety as the location where bank robber John Dillinger was lea ...

.

Hoover was credited for overseeing several highly publicized captures or shootings of outlaws and bank robbers

Bank robbery is the criminal act of stealing from a bank, specifically while bank employees and customers are subjected to force, violence, or a threat of violence. This refers to robbery of a bank branch or teller, as opposed to other bank-ow ...

. These included those of Machine Gun Kelly

George Kelly Barnes (July 18, 1895 – July 18, 1954), better known by his pseudonym "Machine Gun Kelly", was an American gangster from Memphis, Tennessee, active during the Prohibition era. His nickname came from his favorite weapon, a Thomp ...

in 1933, of Dillinger in 1934, and of Alvin Karpis

Alvin Francis Karpis (born Albin Francis Karpavičius; August 10, 1907 – August 26, 1979), a Depression-era gangster nicknamed "Creepy" for his sinister smile and called "Ray" by his gang members, was a Canadian-born (naturalized American) crim ...

in 1936, which led to the Bureau's powers being broadened.

In 1935, the ''Bureau of Investigation'' was renamed the ''Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

'' (FBI). It was not simply a name change. A lot of basic restructuring was done. In fact, Hoover visited the lab of Canadian forensic scientist Wilfrid Derome twice - in 1929 and 1932 - in order to plan the foundation of his own FBI laboratory in the USA.FBI Laboratory

The FBI Laboratory (also called the Laboratory Division) is a division within the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation that provides forensic analysis support services to the FBI, as well as to state and local law enforcement agencies ...

, a division established in 1932 to examine and analyze evidence

Evidence for a proposition is what supports this proposition. It is usually understood as an indication that the supported proposition is true. What role evidence plays and how it is conceived varies from field to field.

In epistemology, eviden ...

found by the FBI.

American Mafia

During the 1930s, Hoover persistently denied the existence of organized crime

Organized crime (or organised crime) is a category of transnational, national, or local groupings of highly centralized enterprises run by criminals to engage in illegal activity, most commonly for profit. While organized crime is generally tho ...

, despite numerous '' gangland'' shootings as Mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of ...

groups struggled for control of the lucrative profits deriving from illegal alcohol sales during Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

, and later for control of prostitution, illegal drugs

The prohibition of drugs through sumptuary legislation or religious law is a common means of attempting to prevent the recreational use of certain intoxicating substances.

While some drugs are illegal to possess, many governments regulate th ...

and other criminal enterprises.

Many writers believe Hoover's denial of the Mafia's existence and his failure to use the full force of the FBI to investigate it were due to Mafia gangsters Meyer Lansky

Meyer Lansky (born Maier Suchowljansky; July 4, 1902 – January 15, 1983), known as the "Mob's Accountant", was an American organized crime figure who, along with his associate Lucky Luciano, Charles "Lucky" Luciano, was instrumental in the deve ...

and Frank Costello

Frank Costello (; born Francesco Castiglia; ; January 26, 1891 – February 18, 1973) was an Italian-American crime boss of the Luciano crime family. In 1957, Costello survived an assassination attempt ordered by Vito Genovese and carried out by ...

's possession of embarrassing photographs of Hoover in the company of his ''protégé'', FBI Deputy Director Clyde Tolson

Clyde Anderson Tolson (May 22, 1900 – April 14, 1975) was the second-ranking official of the FBI from 1930 until 1972, from 1947 titled Associate Director, primarily responsible for personnel and discipline. He was the ''protégé'', long-tim ...

.gossip columnist

A gossip columnist is someone who writes a gossip column in a newspaper or magazine, especially a gossip magazine. Gossip columns are material written in a light, informal style, which relates the gossip columnist's opinions about the personal li ...

Walter Winchell

Walter Winchell (April 7, 1897 – February 20, 1972) was a syndicated American newspaper gossip columnist and radio news commentator. Originally a vaudeville performer, Winchell began his newspaper career as a Broadway reporter, critic and c ...

.

[

] Hoover had a reputation as "an inveterate horseplayer", and was known to send Special Agents to place $100 bets for him.[Sifakis, p.127.] Hoover once said the Bureau had "much more important functions" than arresting bookmakers and gamblers.vice

A vice is a practice, behaviour, or Habit (psychology), habit generally considered immorality, immoral, sinful, crime, criminal, rude, taboo, depraved, degrading, deviant or perverted in the associated society. In more minor usage, vice can refe ...

rackets such as illegal drugs

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhalat ...

, prostitution, and extortion

Extortion is the practice of obtaining benefit through coercion. In most jurisdictions it is likely to constitute a criminal offence; the bulk of this article deals with such cases. Robbery is the simplest and most common form of extortion, ...

and flatly denied the existence of the Mafia in the United States. In the 1950s, evidence of the FBI's unwillingness to investigate the Mafia became a topic of public criticism.

After the Apalachin meeting of crime bosses in 1957, Hoover could no longer deny the existence of a nationwide crime syndicate. At that time Cosa Nostra

The Sicilian Mafia, also simply known as the Mafia and frequently referred to as Cosa nostra (, ; "our thing") by its members, is an Italian Mafia- terrorist-type organized crime syndicate and criminal society originating in the region of Sic ...

's control of the Syndicate's many branches operating criminal activities throughout North America was heavily reported in popular newspapers and magazines. Hoover created the "Top Hoodlum Program" and went after the syndicate's top bosses throughout the country.

Investigation of subversion and radicals

Hoover was concerned about what he claimed was

Hoover was concerned about what he claimed was subversion

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to transform the established social order and its structures of power, authority, hierarchy, and social norms. Sub ...

, and under his leadership, the FBI investigated tens of thousands of suspected subversives and radicals. According to critics, Hoover tended to exaggerate the dangers of these alleged subversives

Subversion () refers to a process by which the values and principles of a system in place are contradicted or reversed in an attempt to transform the established social order and its structures of power, authority, hierarchy, and social norms. ...

and many times overstepped his bounds in his pursuit of eliminating that perceived threat.William G. Hundley

William George Hundley (August 16, 1925 – June 11, 2006) was an American criminal defense attorney, who specialized in the representation of political figures accused of white-collar crimes. Earlier in the 1950s and 1960s, as a United State ...

, a Justice Department prosecutor, joked that Hoover's investigations had actually helped the American communist movement survive, as Hoover's "informants were nearly the only ones that paid the party dues." Due to the FBI's aggressive targeting, by 1957 CPUSA membership had dwindled to less than 10,000, of whom some 1,500 were informants for the FBI.

Florida and Long Island U-boat landings

The FBI investigated rings of German saboteurs and spies starting in the late 1930s, and had primary responsibility for counter-espionage. The first arrests of German agents were made in 1938 and continued throughout World War II. In the Quirin affair, during World War II, German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

s set two small groups of Nazi agents ashore in Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, a ...

and on Long Island to cause acts of sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, disruption, or destruction. One who engages in sabotage is a ''saboteur''. Saboteurs typically try to conceal their identiti ...

within the country. The two teams were apprehended after one of the agents contacted the FBI and told them everything – he was also charged, and convicted.

Illegal wire-tapping

During this time period President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, out of concern over Nazi agents in the United States, gave "qualified permission" to wiretap

Telephone tapping (also wire tapping or wiretapping in American English) is the monitoring of telephone and Internet-based conversations by a third party, often by covert means. The wire tap received its name because, historically, the monitorin ...

persons "suspected ... fsubversive activities". He went on to add, in 1941, that the United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

had to be informed of its use in each case.

The Attorney General Robert H. Jackson

Robert Houghwout Jackson (February 13, 1892 – October 9, 1954) was an American lawyer, jurist, and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1941 until his death in 1954. He had previously served as Uni ...

left it to Hoover to decide how and when to use wiretaps, as he found the "whole business" distasteful. Jackson's successor at the post of Attorney General, Francis Biddle

Francis Beverley Biddle (May 9, 1886 – October 4, 1968) was an American lawyer and judge who was the United States Attorney General during World War II. He also served as the primary American judge during the postwar Nuremberg Trials as well a ...

, did turn down Hoover's requests on occasion.

Concealed espionage discoveries

In the late 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

gave Hoover the task to investigate both foreign espionage in the United States and the activities of domestic communists and fascists. When the Cold War began in the late 1940s, the FBI under Hoover undertook the intensive surveillance of communists and other left-wing activists in the United States.Venona project

The Venona project was a United States counterintelligence program initiated during World War II by the United States Army's Signal Intelligence Service (later absorbed by the National Security Agency), which ran from February 1, 1943, until Octo ...

, a pre-World War II joint project with the British to eavesdrop on Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

spies in the UK and the United States. They did not initially realize that espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

was being committed, but the Soviets' multiple use of one-time pad

In cryptography, the one-time pad (OTP) is an encryption technique that cannot be cracked, but requires the use of a single-use pre-shared key that is not smaller than the message being sent. In this technique, a plaintext is paired with a r ...

ciphers (which with single use are unbreakable) created redundancies that allowed some intercepts to be decoded. These established that espionage was being carried out.

Hoover kept the intercepts – America's greatest counterintelligence

Counterintelligence is an activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or o ...

secret – in a locked safe in his office. He chose not to inform President Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Frankli ...

, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath

James Howard McGrath (November 28, 1903September 2, 1966) was an American politician and attorney from Rhode Island. McGrath, a Democrat, served as U.S. Attorney for Rhode Island before becoming governor, U.S. Solicitor General, U.S. Senator ...

, or Secretaries of State Dean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson (pronounced ; April 11, 1893October 12, 1971) was an American statesman and lawyer. As the 51st U.S. Secretary of State, he set the foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration from 1949 to 1953. He was also Truma ...

and General George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (December 31, 1880 – October 16, 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the US Army under Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry ...

while they held office. He informed the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

(CIA) of the Venona Project in 1952.

Plans for expanding the FBI to do global intelligence

After World War II, Hoover advanced plans to create a "World-Wide Intelligence Service". These plans were shot down by the Truman administration. Truman objected to the plan, emerging bureaucratic competitors opposed the centralization of power inherent in the plans, and there was a considerable aversion to creating an American version of the "Gestapo."

Plans for suspending ''habeas corpus''

In 1946, Attorney General Tom C. Clark authorized Hoover to compile a list of potentially disloyal Americans who might be detained during a wartime national emergency. In 1950, at the outbreak of the Korean War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Korean War

, partof = the Cold War and the Korean conflict

, image = Korean War Montage 2.png

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Clockwise from top: ...

, Hoover submitted a plan to President Truman to suspend the writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' and detain 12,000 Americans suspected of disloyalty. Truman did not act on the plan.

COINTELPRO and the 1950s

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point ...

decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute people for their political opinions, most notably communists. Some of his aides reported that he purposely exaggerated the threat of communism to "ensure financial and public support for the FBI." At this time he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO ( syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program; 1956–1971) was a series of covert and illegal projects actively conducted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltrati ...

. COINTELPRO was first used to disrupt the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

, where Hoover ordered observation and pursuit of targets that ranged from suspected citizen spies to larger celebrity figures, such as Charlie Chaplin, whom he saw as spreading Communist Party propaganda.

COINTELPRO's methods included infiltration, burglaries, setting up illegal wiretaps, planting forged documents, and spreading false rumors about key members of target organizations. Some authors have charged that COINTELPRO methods also included inciting violence and arranging murders.

This program remained in place until it was exposed to the public in 1971, after the burglary by a group of eight activists of many internal documents from an office in Media, Pennsylvania

Media is a borough in and the county seat of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. It is located about west of Philadelphia, the sixth most populous city in the nation with 1.6 million residents as 2020. It is part of the Delaware Valley metropolita ...

, whereupon COINTELPRO became the cause of some of the harshest criticism of Hoover and the FBI. COINTELPRO's activities were investigated in 1975 by the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, called the "Church Committee

The Church Committee (formally the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities) was a US Senate select committee in 1975 that investigated abuses by the Central Intelligence ...

" after its chairman, Senator Frank Church

Frank Forrester Church III (July 25, 1924 – April 7, 1984) was an American politician and lawyer. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States senator from Idaho from 1957 until his defeat in 1981. As of 2022, he is the longe ...

( D-Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and W ...

); the committee declared COINTELPRO's activities were illegal and contrary to the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

.

Hoover amassed significant power by collecting files containing large amounts of compromising and potentially embarrassing information on many powerful people, especially politicians. According to Laurence Silberman

Laurence Hirsch Silberman (October 12, 1935 – October 2, 2022) was an American lawyer, diplomat, jurist, and government official who served as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ...

, appointed Deputy Attorney General

The Deputy Attorney General (DAG) is the second-highest-ranking official in a department of justice or of law, in various governments of the world. In those governments, the deputy attorney general oversees the day-to-day operation of the departme ...

in early 1974, FBI Director Clarence M. Kelley thought such files either did not exist or had been destroyed. After ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large n ...

'' broke a story in January 1975, Kelley searched and found them in his outer office. The House Judiciary Committee

The U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, also called the House Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is charged with overseeing the administration of justice within the federal courts, ...

then demanded that Silberman testify about them.

Reaction to civil rights groups

In 1956, several years before he targeted

In 1956, several years before he targeted Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, Hoover had a public showdown with T. R. M. Howard

Theodore Roosevelt Mason Howard (March 4, 1908 – May 1, 1976) was an American civil rights leader, fraternal organization leader, entrepreneur and surgeon. He was a mentor to activists such as Medgar Evers, Charles Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, ...

, a civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life ...

leader from Mound Bayou, Mississippi

Mound Bayou is a city in Bolivar County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,533 at the 2010 census, down from 2,102 in 2000. It was founded as an independent black community in 1887 by former slaves led by Isaiah Montgomery.

Mound ...

. During a national speaking tour, Howard had criticized the FBI's failure to investigate thoroughly the racially motivated murders of George W. Lee, Lamar Smith

Lamar Seeligson Smith (born November 19, 1947) is an American politician and lobbyist who served in the United States House of Representatives for for 16 terms, a district including most of the wealthier sections of San Antonio and Austin, as ...

, and Emmett Till

Emmett Louis Till (July 25, 1941August 28, 1955) was a 14-year-old African American boy who was abducted, tortured, and lynched in Mississippi in 1955, after being accused of offending a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in her family's grocery ...

. Hoover wrote an open letter

An open letter is a letter that is intended to be read by a wide audience, or a letter intended for an individual, but that is nonetheless widely distributed intentionally.

Open letters usually take the form of a letter addressed to an individ ...

to the press singling out these statements as "irresponsible."

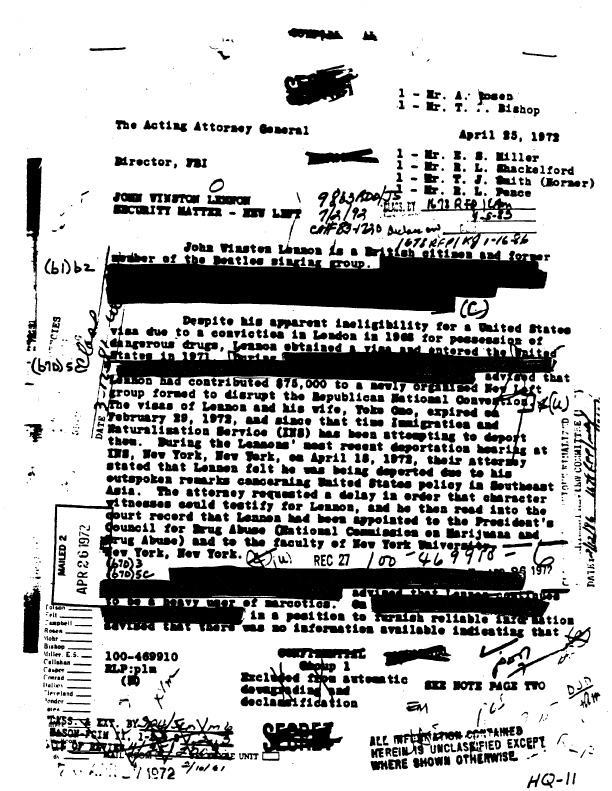

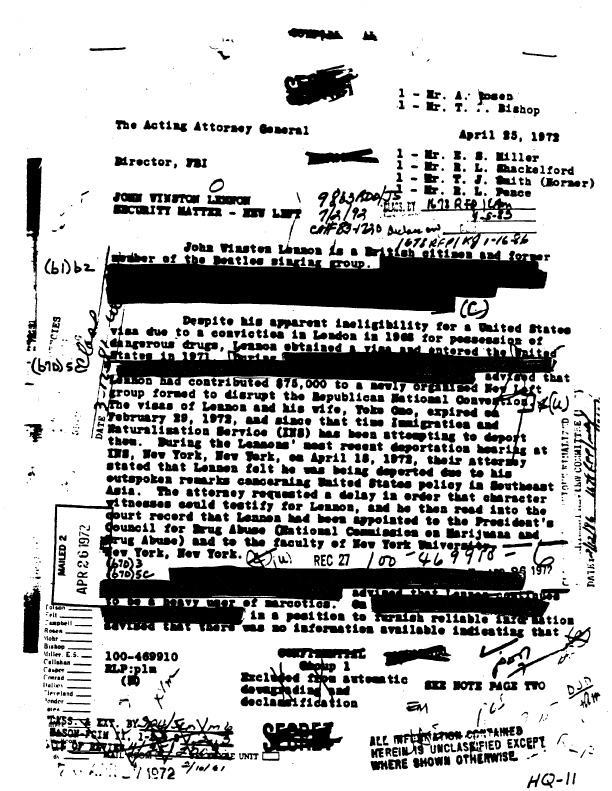

In the 1960s, Hoover's FBI monitored John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter, musician and peace activist who achieved worldwide fame as founder, co-songwriter, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of ...

, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an American Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figure during the civil rights movement. A spokesman for the Nation of ...

, and Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and activist. Nicknamed "The Greatest", he is regarded as one of the most significant sports figures of the 20th century, ...

. The COINTELPRO tactics were later extended to organizations such as the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious and political organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930.

A black nationalist organization, the NOI focuses its attention on the African diaspora, especially on African ...

, the Black Panther Party

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxist-Leninist and black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton in October 1966 in Oakland, Cali ...

, King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization based in Atlanta, Georgia. SCLC is closely associated with its first president, Martin Luther King Jr., who had a large role in the American civ ...

and others. Hoover's moves against people who maintained contacts with subversive elements, some of whom were members of the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

, also led to accusations of trying to undermine their reputations.

The treatment of Martin Luther King Jr. and actress Jean Seberg

Jean Dorothy Seberg (; ; November 13, 1938August 30, 1979) was an American actress who lived half of her life in France. Her performance in Jean-Luc Godard's 1960 film ''Breathless'' immortalized her as an icon of French New Wave cinema.

Seb ...

are two examples: Jacqueline Kennedy

Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis ( ; July 28, 1929 – May 19, 1994) was an American socialite, writer, photographer, and book editor who served as first lady of the United States from 1961 to 1963, as the wife of President John F. Kennedy. A po ...

recalled that Hoover told President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

that King had tried to arrange a sex party while in the capital for the March on Washington

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, also known as simply the March on Washington or The Great March on Washington, was held in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963. The purpose of the march was to advocate for the civil and economic rig ...

and that Hoover told Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, a ...

that King had made derogatory comments during the President's funeral. Under Hoover's leadership, the FBI sent an anonymous blackmail letter to King in 1964, urging him to commit suicide. King's aide

King's aide Andrew Young

Andrew Jackson Young Jr. (born March 12, 1932) is an American politician, diplomat, and activist. Beginning his career as a pastor, Young was an early leader in the civil rights movement, serving as executive director of the Southern Christian L ...

claimed in a 2013 interview with the Academy of Achievement

The American Academy of Achievement, colloquially known as the Academy of Achievement, is a non-profit educational organization that recognizes some of the highest achieving individuals in diverse fields and gives them the opportunity to meet o ...

that the main source of tension between the SCLC and FBI was the government agency's lack of black agents, and that both parties were willing to co-operate with each other by the time the Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three Demonstration (protest), protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery. The marches were organized ...

had taken place.

In one 1965 incident, white civil rights worker Viola Liuzzo

Viola Fauver Liuzzo (née Gregg; April 11, 1925 – March 25, 1965) was an American civil rights activist. In March 1965, Liuzzo heeded the call of Martin Luther King Jr. and traveled from Detroit, Michigan, to Selma, Alabama, in the wake of the ...

was murdered by Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

smen, who had given chase and fired shots into her car after noticing that her passenger was a young black man; one of the Klansmen was Gary Thomas Rowe, an acknowledged FBI informant.[Gary May, The Informant: The FBI, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Murder of Viola Luzzo, Yale University Press, 2005.] The FBI spread rumors that Liuzzo was a member of the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. ...

and had abandoned her children to have sexual relationships with African Americans involved in the civil rights movement.Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

.16th Street Baptist Church bombing

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was a white supremacist terrorist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on Sunday, September 15, 1963. Four members of a local Ku Klux Klan chapter planted 19 sticks of dynam ...

by members of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Ca ...

that killed four girls. By May 1965, local investigators and the FBI had identified suspects in the bombing and witnesses, and this information was relayed to Hoover.federal

Federal or foederal (archaic) may refer to:

Politics

General

*Federal monarchy, a federation of monarchies

*Federation, or ''Federal state'' (federal system), a type of government characterized by both a central (federal) government and states or ...

investigators.Weather Underground

The Weather Underground was a Far-left politics, far-left militant organization first active in 1969, founded on the Ann Arbor, Michigan, Ann Arbor campus of the University of Michigan. Originally known as the Weathermen, the group was organiz ...

per testimony from William C. Sullivan.

Late career and death

One of his biographers, Kenneth Ackerman, wrote that the allegation that Hoover's secret files kept presidents from firing him "is a myth."[

] However, Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was t ...

was recorded in 1971 as stating that one of the reasons he would not fire Hoover was that he was afraid of Hoover's reprisals against him. Similarly, Presidents Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Frankli ...

and John F. Kennedy considered dismissing Hoover as FBI Director, but ultimately concluded that the political cost of doing so would be too great.Jack Valenti

Jack Joseph Valenti (September 5, 1921 – April 26, 2007) was an American political advisor and lobbyist who served as a Special Assistant to U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson. He was also the longtime president of the Motion Picture Associatio ...

, a special assistant and confidant of President Lyndon Johnson. Despite Valenti's two-year marriage to Johnson's personal secretary, the investigation focused on rumors that he was having a gay relationship with a commercial photographer friend.

Hoover personally directed the FBI investigation of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was assassinated on Friday, November 22, 1963, at 12:30 p.m. CST in Dallas, Texas, while riding in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza. Kennedy was in the vehicle wit ...

. In 1964, just days before Hoover testified in the earliest stages of the Warren Commission

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President Lyndon B. Johnson through on November 29, 1963, to investigate the assassination of United States ...

hearings, President Lyndon B. Johnson waived the then-mandatory U.S. Government Service Retirement Age of 70, allowing Hoover to remain the FBI Director "for an indefinite period of time". The House Select Committee on Assassinations

The United States House of Representatives Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) was established in 1976 to investigate the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1963 and 1968, respectively. The HSCA completed its ...

issued a report in 1979 critical of the performance by the FBI, the Warren Commission, and other agencies. The report criticized the FBI's (Hoover's) reluctance to investigate thoroughly the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President.

When Richard Nixon took office in January 1969, Hoover had just turned 74. There was a growing sentiment in Washington, D.C., that the aging FBI chief should retire, but Hoover's power and friends in Congress remained too strong for him to be forced to do so.

Hoover remained director of the FBI until he died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which m ...

in his Washington home, on May 2, 1972,[

] whereupon operational command of the Bureau was passed onto Associate Director Clyde Tolson

Clyde Anderson Tolson (May 22, 1900 – April 14, 1975) was the second-ranking official of the FBI from 1930 until 1972, from 1947 titled Associate Director, primarily responsible for personnel and discipline. He was the ''protégé'', long-tim ...

. On May 3, 1972, Nixon appointed L. Patrick Gray

Louis Patrick Gray III (July 18, 1916 – July 6, 2005) was Acting Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from May 3, 1972 to April 27, 1973. During this time, the FBI was in charge of the initial investigation into the burglarie ...

– a Justice Department official with no FBI experience – as Acting Director of the FBI, with W. Mark Felt

William Mark Felt Sr. (August 17, 1913 – December 18, 2008) was an American law enforcement officer who worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1942 to 1973 and was known for his role in the Watergate scandal. Felt wa ...

becoming associate director.

Hoover's body lay in state in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, where Chief Justice Warren Burger

Warren Earl Burger (September 17, 1907 – June 25, 1995) was an American attorney and jurist who served as the 15th chief justice of the United States from 1969 to 1986. Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Burger graduated from the St. Paul College ...

eulogized him. Up to that time, Hoover was the only civil servant to have lain in state, according to ''The New York Daily News''. At the time, ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' observed that this was "an honor accorded to only 21 persons before, of whom eight were Presidents or former Presidents." (The Architect of the Capitol

The Architect of the Capitol (AOC) is the federal agency responsible for the maintenance, operation, development, and preservation of the United States Capitol Complex. It is an agency of the legislative branch of the federal government and i ...

website provides a list of all those so honored, including Capitol Police killed in the line of duty in 1998 and 2021.) President Nixon delivered another eulogy at the funeral service in the National Presbyterian Church

The National Presbyterian Church is a Christian congregation of approximately 1,500 members of all ages from the greater metropolitan Washington, D.C., area. The mission statement of the church is "Leading People to Become Faithful Followers of J ...

, and called Hoover "one of the Giants, hose

A hose is a flexible hollow tube designed to carry fluids from one location to another. Hoses are also sometimes called ''pipes'' (the word ''pipe'' usually refers to a rigid tube, whereas a hose is usually a flexible one), or more generally ' ...

long life brimmed over with magnificent achievement and dedicated service to this country which he loved so well". Hoover was buried in the Congressional Cemetery

The Congressional Cemetery, officially Washington Parish Burial Ground, is a historic and active cemetery located at 1801 E Street, SE, in Washington, D.C., on the west bank of the Anacostia River. It is the only American "cemetery of national m ...

in Washington, D.C., next to the graves of his parents and a sister who had died in infancy.

Legacy

Biographer Kenneth D. Ackerman summarizes Hoover's legacy thus:

Biographer Kenneth D. Ackerman summarizes Hoover's legacy thus:

For better or worse, he built the FBI into a modern, national organization stressing professionalism and scientific crime-fighting. For most of his life, Americans considered him a hero. He made the G-Man

''G-man'' (short for "government man", plural ''G-men'') is an American slang term for agents of the United States Government. It is especially used as a term for an agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

''G-man'' is also a term ...

brand so popular that, at its height, it was harder to become an FBI agent than to be accepted into an Ivy League college.

Hoover worked to groom the image of the FBI in American media; he was a consultant to Warner Brothers

Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. (commonly known as Warner Bros. or abbreviated as WB) is an American Film studio, film and entertainment studio headquartered at the Warner Bros. Studios, Burbank, Warner Bros. Studios complex in Burbank, Califo ...

for a theatrical film about the FBI, ''The FBI Story

''The FBI Story'' is a 1959 American drama film starring James Stewart, and produced and directed by Mervyn LeRoy. The screenplay by Richard L. Breen and John Twist is based on a book by Don Whitehead.

Plot

John Michael ("Chip") Hardesty ( Jam ...

'' (1959), and in 1965 on Warner's long-running spin-off television series, '' The F.B.I.'' Hoover personally made sure Warner Brothers portrayed the FBI more favorably than other crime dramas of the times.

U.S. President Harry S Truman

Harry may refer to:

TV shows

* ''Harry'' (American TV series), a 1987 American comedy series starring Alan Arkin

* ''Harry'' (British TV series), a 1993 BBC drama that ran for two seasons

* ''Harry'' (talk show), a 2016 American daytime talk show ...

said that Hoover transformed the FBI into his private secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

force:

... we want no Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

or secret police. The FBI is tending in that direction. They are dabbling in sex-life scandals and plain blackmail. J. Edgar Hoover would give his right eye to take over, and all congressmen and senators are afraid of him.

Because Hoover's actions came to be seen as abuses of power, FBI directors are now limited to one 10-year term, subject to extension by the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and ...

.

Jacob Heilbrunn, journalist and senior editor at ''The'' ''National Interest'' gives a mixed assessment of Hoover's legacy:

The FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C. is named the J. Edgar Hoover Building, after Hoover. Because of the controversial nature of Hoover's legacy, both Republicans and Democrats have periodically introduced legislation in the House and Senate to rename it. The first such proposal came just two months after the building's inauguration. On December 12, 1979, Gilbert Gude

Gilbert Gude (March 9, 1923 – June 7, 2007) was an American politician who served as the U.S. representative for Maryland's 8th congressional district from 1967 to 1977. He was a member of the Republican Party.

Early life and career

Gude was ...

– a Republican congressman from Maryland – introduced H.R. 11137, which would have changed the name of the edifice from the "J. Edgar Hoover F.B.I. Building" to simply the "F.B.I. Building."Howard Metzenbaum

Howard Morton Metzenbaum (June 4, 1917March 12, 2008) was an American politician and businessman who served for almost 20 years as a Democratic member of the U.S. Senate from Ohio (1974, 1976–1995). He also served in the Ohio House ...

pushed for a name change following a new report about Hoover's ordered "loyalty investigation" of future Senator Quentin Burdick

Quentin Northrup Burdick (June 19, 1908 – September 8, 1992) was an American lawyer and politician. A member of the North Dakota Democratic-NPL Party, he represented North Dakota in the U.S. House of Representatives (1959–1960) and the U.S ...

. In 1998, Democratic Senator Harry Reid

Harry Mason Reid Jr. (; December 2, 1939 – December 28, 2021) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Nevada from 1987 to 2017. He led the Senate Democratic Caucus from 2005 to 2017 and was the Sena ...

sponsored an amendment to strip Hoover's name from the building, stating that "J. Edgar Hoover's name on the FBI building is a stain on the building."[O'Keefe, Ed. "FBI J. Edgar Hoover Building 'Deteriorating,' Report Says." ''Washington Post.'' November 9, 2011.](_blank)

Accessed September 29, 2012. and its naming might eventually be made moot by the FBI moving its headquarters to a new suburban site.

Hoover's practice of violating civil liberties for the stated sake of national security has been questioned in reference to recent national surveillance programs. An example is a lecture titled ''Civil Liberties and National Security: Did Hoover Get it Right?'', given at The Institute of World Politics

The Institute of World Politics (IWP) is a private graduate school of national security, intelligence, and international affairs in Washington DC, and Reston, Virginia. Founded in 1990, it offers courses related to intelligence, national se ...

on April 21, 2015.

Private life

Pets

Hoover received his first dog from his parents when he was a child, after which he was never without one. He owned many throughout his lifetime and became an aficionado especially knowledgeable in breeding of pedigrees, particularly Cairn Terrier

The Cairn Terrier is a terrier breed originating in the Scottish Highlands and recognized as one of Scotland's earliest working dogs. The breed was given the name Cairn because the breed's function was to hunt and chase quarry between the c ...

s and Beagle

The beagle is a Dog breed, breed of small scent hound, similar in appearance to the much larger foxhound. The beagle was developed primarily for Tracking (hunting), hunting hare, known as beagling. Possessing a great sense of smell and sup ...

s. He gave many dogs to notable people, such as Presidents Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was an American politician who served as the 31st president of the United States from 1929 to 1933 and a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, holding o ...

(no relation) and Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

, and buried seven canine pets, including a Cairn Terrier named Spee De Bozo, at Aspen Hill Memorial Park, in Silver Spring, Maryland

Silver Spring is a census-designated place (CDP) in southeastern Montgomery County, Maryland, Montgomery County, Maryland, United States, near Washington, D.C. Although officially Unincorporated area, unincorporated, in practice it is an edge cit ...

.

Sexuality

From the 1940s, rumors circulated that Hoover, who was still living with his mother in his early 40s, was homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

. The historians John Stuart Cox and Athan G. Theoharis speculated that Clyde Tolson, who became an assistant director to Hoover in his mid 40s and became his primary heir, was a lover to Hoover until his death.[

] Hoover reportedly hunted down and threatened anyone who made insinuations about his sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied wi ...

.[

] Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

, who enjoyed repeating salacious rumors about Hoover, once remarked that he was more interested in making Hoover angry than determining whether the rumors were true.Screw

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to fa ...

'' published the first reference in print to J. Edgar Hoover's sexuality, titled "Is J. Edgar Hoover a Fag?"

Some associates and scholars dismiss rumors about Hoover's sexuality, and rumors about his relationship with Tolson in particular, as unlikely,[

] while others have described them as probable or even "confirmed".[

] Still other scholars have reported the rumors without expressing an opinion.

Cox and Theoharis concluded that "the strange likelihood is that Hoover never knew sexual desire at all."[ ]Anthony Summers

Anthony Bruce Summers (born 21 December 1942) is an Irish author. He is a Pulitzer Prize Finalist and has written ten non-fiction books.

Career

Summers is an Irish citizen who has been working with Robbyn Swan for more than thirty years bef ...

, who wrote ''Official and Confidential: The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover'' (1993), stated that there was no ambiguity about the FBI director's sexual proclivities and described him as "bisexual with failed heterosexuality."[

]

Hoover and Tolson

Hoover described Tolson as his

Hoover described Tolson as his alter ego

An alter ego (Latin for "other I", "doppelgänger") means an alternate self, which is believed to be distinct from a person's normal or true original personality. Finding one's alter ego will require finding one's other self, one with a differe ...

: the men worked closely together during the day and, both single, frequently took meals, went to night clubs, and vacationed together.Mark Felt

William Mark Felt Sr. (August 17, 1913 – December 18, 2008) was an American law enforcement officer who worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1942 to 1973 and was known for his role in the Watergate scandal. Felt wa ...

, say the relationship was "brotherly"; however, former FBI executive assistant director Mike Mason suggested that some of Hoover's colleagues denied that he had a sexual relationship with Tolson in an effort to protect Hoover's image.

The novelist William Styron

William Clark Styron Jr. (June 11, 1925 – November 1, 2006) was an American novelist and essayist who won major literary awards for his work.

Styron was best known for his novels, including:

* '' Lie Down in Darkness'' (1951), his acclaimed f ...

told Summers that he once saw Hoover and Tolson in a California beach house, where the director was painting his friend's toenails. Harry Hay

Henry "Harry" Hay Jr. (April 7, 1912 – October 24, 2002) was an American gay rights activist, communist, and labor advocate. He was a co-founder of the Mattachine Society, the first sustained gay rights group in the United States, as well as ...

, founder of the Mattachine Society

The Mattachine Society (), founded in 1950, was an early national gay rights organization in the United States, perhaps preceded only by Chicago's Society for Human Rights. Communist and labor activist Harry Hay formed the group with a collection ...

, one of the first gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , ...

organizations, said Hoover and Tolson sat in boxes owned by and used exclusively by gay men at the Del Mar racetrack

The Del Mar Fairgrounds is a event venue in Del Mar, California. The annual San Diego County Fair is held here, which was called the Del Mar Fair from 1984 to 2001. In 1936, the Del Mar Racetrack was built by the Thoroughbred Club with foundin ...

in California.American flag

The national flag of the United States of America, often referred to as the ''American flag'' or the ''U.S. flag'', consists of thirteen equal horizontal stripes of red (top and bottom) alternating with white, with a blue rectangle in the c ...

that draped Hoover's casket. Tolson is buried a few yards away from Hoover in the Congressional Cemetery.

Other romantic allegations

One of Hoover's biographers, Richard Hack, does not believe the director was gay. Hack notes that Hoover was romantically linked to actress Dorothy Lamour

Dorothy Lamour (born Mary Leta Dorothy Slaton; December 10, 1914 – September 22, 1996) was an American actress and singer. She is best remembered for having appeared in the '' Road to...'' movies, a series of successful comedies starring Bing ...

in the late 1930s and early 1940s and that after Hoover's death, Lamour did not deny rumors that she had had an affair with him.Lela Rogers

Lela E. Rogers (née Lela Emogene Owens; 1891–1977), sometimes known as Lela Liebrand, was an American journalist, film producer, film editor, and screenwriter. She was the mother of actress Ginger Rogers.

Biography

Beginnings

Born on C ...

, the divorced mother of dancer and actress Ginger Rogers

Ginger Rogers (born Virginia Katherine McMath; July 16, 1911 – April 25, 1995) was an American actress, dancer and singer during the Golden Age of Hollywood. She won an Academy Award for Best Actress for her starring role in ''Kitty Foyle'' ...

, so often that many of their mutual friends assumed the pair would eventually marry.

Pornography for blackmail

Hoover kept a large collection of pornographic material, possibly the world's largest, of films, photographs, and written materials, with particular emphasis on nude photos of celebrities. He reportedly used these for his own titillation and held them for blackmail