Joe Pearce (politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Pearce (born February 12, 1961), is an English-born American writer, and Director of the Center for Faith and Culture at

Pearce decided to convert to Catholicism during his second prison term (1985-1986). He was received into the Catholic Church during

Pearce decided to convert to Catholicism during his second prison term (1985-1986). He was received into the Catholic Church during

41st Annual Chesterton Conference, July 28-30, 2022

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

Autobiographical page

''Saint Austin Review''

* Clips of Joseph Pearce speaking about his conversion

12

Joseph Pearce speaks about his conversion

EWTN's page for the TV show

Tolkien's Lord Of The Rings — A Catholic Worldview

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pearce, Joseph 1961 births American Roman Catholic poets American modernist poets Ave Maria University faculty British expatriate academics in the United States British modernist poets Catholic philosophers Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism Distributism English biographers English emigrants to the United States English Catholic poets English Roman Catholics English Roman Catholic writers Formalist poets Living people National Front (UK) politicians Naturalized citizens of the United States People from Dagenham People from Nashville, Tennessee Shakespearean scholars Sonneteers Tolkien studies

Aquinas College :''See also List of institutions named after Thomas Aquinas''

Aquinas College may refer to any one of several educational institutions:

In Australia

*Aquinas College, Perth, Roman Catholic boys' R–12 school

*Aquinas College, Adelaide, residenti ...

in Nashville, Tennessee

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the county seat, seat of Davidson County, Tennessee, Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the List of muni ...

, before which he held positions at Thomas More College of Liberal Arts

The Thomas More College of Liberal Arts is a private Roman Catholic liberal arts college in Merrimack, New Hampshire. It emphasizes classical education in the Catholic intellectual tradition and is named after Saint Thomas More. It is accredite ...

in Merrimack, New Hampshire

Merrimack is a New England town, town in Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire, United States. The population was 26,632 as of the 2020 census.

There are four villages in the town: Merrimack Village (formerly kno ...

, Ave Maria College

''Alta Velocidad Española'' (''AVE'') is a service of high-speed rail in Spain operated by Renfe, the Spanish national railway company, at speeds of up to . As of December 2021, the Spanish high-speed rail network, on part of which the AVE ...

in Ypsilanti, Michigan

Ypsilanti (), commonly shortened to Ypsi, is a city in Washtenaw County in the U.S. state of Michigan.

As of the 2020 census, the city's population was 20,648. The city is bounded to the north by Superior Township and on the west, south, and ...

and Ave Maria University in Ave Maria, Florida

Ave Maria, Florida, United States, is a planned community and Census-designated place in Collier County, Florida.

History

Ave Maria, Florida was founded in 2005 by Ave Maria Development Company, a partnership consisting of the Barron Collier ...

.

Formerly aligned with the National Front, a white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

group, he converted to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

in 1989, repudiated his earlier views, and now writes from a Catholic perspective and espouses Monarchism

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

and Catholic Social Teaching

Catholic social teaching, commonly abbreviated CST, is an area of Catholic doctrine concerning matters of human dignity and the common good in society. The ideas address oppression, the role of the state (polity), state, subsidiarity, social o ...

. He is a co-editor of the ''St. Austin Review

The ''St. Austin Review'' (StAR) is a Catholic international review of culture and ideas. It is edited by author, columnist and EWTN TV host Joseph Pearce and literary scholar Robert Asch. StAR includes book reviews, discussions on Christian art ...

'' and editor-in-chief of Sapientia Press. He also teaches Shakespearian literature for an online Catholic curriculum provider.

Pearce has written biographies of literary figures, often Christian, including William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

, J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philology, philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was ...

, Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, C. S. Lewis

Clive Staples Lewis (29 November 1898 – 22 November 1963) was a British writer and Anglican lay theologian. He held academic positions in English literature at both Oxford University (Magdalen College, 1925–1954) and Cambridge Univers ...

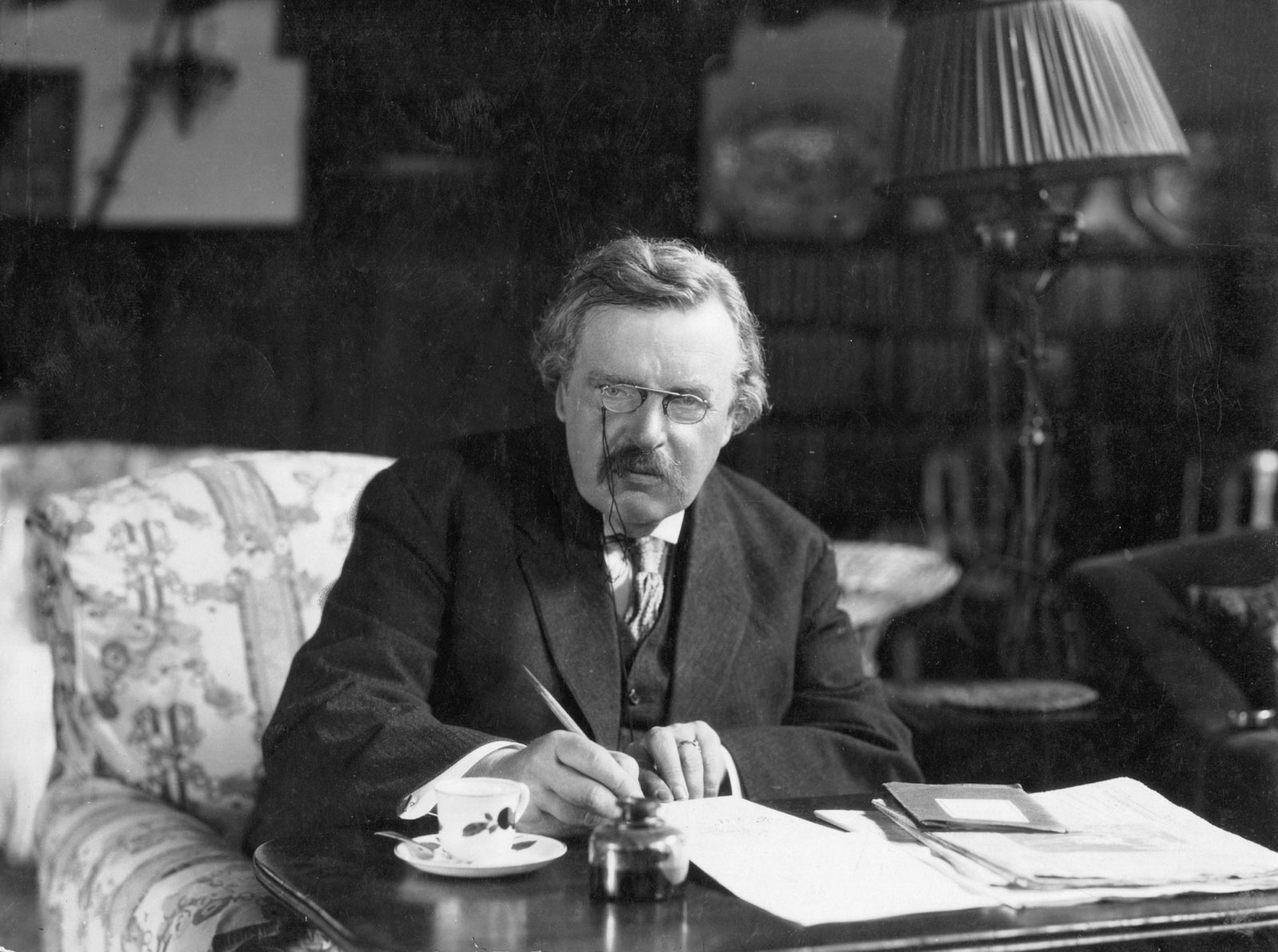

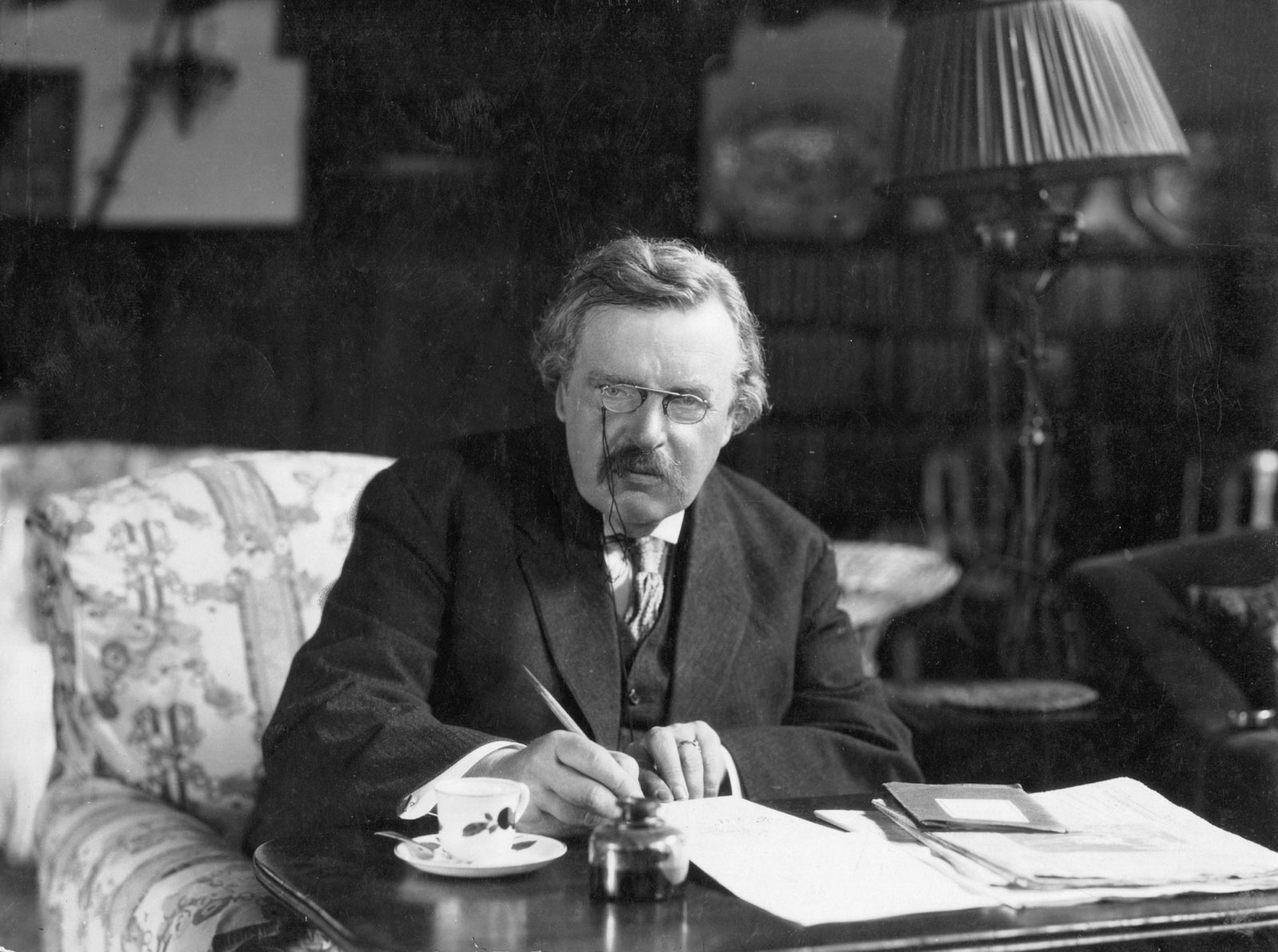

, G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Aleksandr Isayevich Solzhenitsyn. (11 December 1918 – 3 August 2008) was a Russian novelist. One of the most famous Soviet dissidents, Solzhenitsyn was an outspoken critic of communism and helped to raise global awareness of political repress ...

and Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

. His books have been translated into at least nine languages.

Biography

Early life

Joseph Pearce was born inBarking, London

Barking is a suburb and List of areas of London, area in Greater London, within the London Borough of Barking and Dagenham, Borough of Barking and Dagenham. It is east of Charing Cross. The total population of Barking was 59,068 at the 2011 cen ...

, and brought up in Haverhill, Suffolk

Haverhill ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in the county of Suffolk, England, next to the borders of Essex and Cambridgeshire. It lies about south east of Cambridge, south west of Bury St Edmunds, and north west of Braintree and Colche ...

. His father, Albert Arthur Pearce, was a heavy drinker with a history of brawling in pub

A pub (short for public house) is a kind of drinking establishment which is licensed to serve alcoholic drinks for consumption on the premises. The term ''public house'' first appeared in the United Kingdom in late 17th century, and was ...

s with Irishmen and non-Whites, had an encyclopedic knowledge of English poetry

This article focuses on poetry from the United Kingdom written in the English language. The article does not cover poetry from other countries where the English language is spoken, including Republican Ireland after December 1922.

The earliest ...

and British military history

The military history of the United Kingdom covers the period from the creation of the united Kingdom of Great Britain, with the political union of England and Scotland in 1707, to the present day.

From the 18th century onwards, with the expansio ...

, and an intense nostalgia

Nostalgia is a sentimentality for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations. The word ''nostalgia'' is a learned formation of a Greek language, Greek compound, consisting of (''nóstos''), meaning "homecoming", ...

for the vanished British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. In 1973 the family moved to Barking in the East End of London

The East End of London, often referred to within the London area simply as the East End, is the historic core of wider East London, east of the Roman and medieval walls of the City of London and north of the River Thames. It does not have uni ...

, so that the Pearce boys would grow up with Cockney accent

Cockney is an accent and dialect of English, mainly spoken in London and its environs, particularly by working-class and lower middle-class Londoners. The term "Cockney" has traditionally been used to describe a person from the East End, or b ...

s. Pearce had been a compliant pupil at the school in Haverhill, but at Eastbury comprehensive school

A comprehensive school typically describes a secondary school for pupils aged approximately 11–18, that does not select its intake on the basis of academic achievement or aptitude, in contrast to a selective school system where admission is res ...

in Barking he led the racist

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

disruption of the lessons taught by a young Pakistani British

British Pakistanis ( ur, (Bratānia men maqīm pākstānī); also known as Pakistani British people or Pakistani Britons) are citizens or residents of the United Kingdom whose ancestral roots lie in Pakistan. This includes people born in ...

mathematics teacher.

Neo-Nazism

At 15, Pearce joined theyouth wing

A youth wing is a subsidiary, autonomous, or independently allied front of a larger organization (usually a political party but occasionally another type of organization) that is formed in order to rally support for that organization from members ...

of the National Front, an anti-Semitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and white supremacist

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other Race (human classification), races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any Power (social and polit ...

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

advocating the compulsory repatriation of all immigrants

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not natives or where they do not possess citizenship in order to settle as permanent residents or naturalized citizens. Commuters, tourists, and ...

and British-born non-Whites. He came to prominence in 1977 when he set up ''Bulldog'', the NF's openly racist newspaper. Like his father, Pearce became an enthusiastic supporter of Ulster Loyalism

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a uni ...

during the Troubles

The Troubles ( ga, Na Trioblóidí) were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "i ...

from 1978, and joined the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

, a militantly anti-Catholic

Anti-Catholicism is hostility towards Catholics or opposition to the Catholic Church, its Hierarchy of the Catholic Church, clergy, and/or its adherents. At various points after the Reformation, some majority Protestantism, Protestant states, ...

secret society

A secret society is a club or an organization whose activities, events, inner functioning, or membership are concealed. The society may or may not attempt to conceal its existence. The term usually excludes covert groups, such as intelligence a ...

closely linked to Ulster Loyalist paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

organizations. In 1980, he became editor of ''Nationalism Today'', advocating white supremacy. Pearce was twice prosecuted and imprisoned under the Race Relations Act of 1976 for his writings, in 1981 and 1985. At one stage, he contacted John Tyndall

John Tyndall FRS (; 2 August 1820 – 4 December 1893) was a prominent 19th-century Irish physicist. His scientific fame arose in the 1850s from his study of diamagnetism. Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the p ...

to suggest coalition talks with the British National Party

The British National Party (BNP) is a far-right, fascist political party in the United Kingdom. It is headquartered in Wigton, Cumbria, and its leader is Adam Walker. A minor party, it has no elected representatives at any level of UK gover ...

, but Tyndall rejected the plan. Pearce was a close associate of Nick Griffin

Nicholas John Griffin (born 1 March 1959) is a British politician and white supremacist who represented North West England as a Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from 2009 to 2014. He served as chairman and then president of the far-righ ...

, whom he helped to oust Martin Webster

Martin Guy Alan Webster (born 14 May 1943) is a British neo-nazi, a former leading figure on the far-right in the United Kingdom. An early member of the National Labour Party, he was John Tyndall's closest ally, and followed him in joining ...

from the NF's leadership. As a spokesman for the Strasserite

Strasserism (german: Strasserismus or ''Straßerismus'') is a strand of Nazism calling for a more radical, mass-action and worker-based form of the ideology, espousing economic antisemitism above other antisemitic forms, to achieve a national ...

Political Soldier faction within the NF, Pearce argued for white supremacy, publishing the ''Fight for Freedom!'' pamphlet in 1984. At the same time, however, Pearce adopted the group's support for ethnopluralism

Ethnopluralism or ethno-pluralism, also known as ethno-differentialism, is a political concept which relies on preserving and mutually respecting separate and bordered ethno-cultural regions. Among the key components are the "right to difference" ( ...

, contacting the Iranian embassy in London in 1984 in a vain attempt to secure funding from the Government of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

. Pearce became a leading member of a new NF political faction known as the Flag Group, writing for its publications and contributing to its ideology. Pearce notably argued, based on the writings of G.K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

and Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

, for distributism

Distributism is an economic theory asserting that the world's productive assets should be widely owned rather than concentrated.

Developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, distributism was based upon Catholic social teaching prin ...

as an alternative to both Marxism

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

and Laissez faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. A ...

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

in a 1987 article for the party magazine ''Vanguard''.

Conversion

Pearce decided to convert to Catholicism during his second prison term (1985-1986). He was received into the Catholic Church during

Pearce decided to convert to Catholicism during his second prison term (1985-1986). He was received into the Catholic Church during Mass

Mass is an intrinsic property of a body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the quantity of matter in a physical body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physics. It was found that different atoms and different elementar ...

at Our Lady Mother of God Church in Norwich, England

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

on Saint Joseph's Day

Saint Joseph's Day, also called the Feast of Saint Joseph or the Solemnity of Saint Joseph, is in Western Christianity the principal feast day of Saint Joseph, husband of the Virgin Mary and legal father of Jesus Christ, celebrated on 19 March. ...

, 19 March 1989. Following the Mass, the women of the parish held a surprise party for Pearce, accompanied by a cake with, "Welcome Home, Joe", emblazoned on it. Pearce has attributed his conversion to reading books by Catholic authors G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

, John Henry Newman

John Henry Newman (21 February 1801 – 11 August 1890) was an English theologian, academic, intellectual, philosopher, polymath, historian, writer, scholar and poet, first as an Anglican ministry, Anglican priest and later as a Catholi ...

, J.R.R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was the Rawlins ...

, and Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

.

Ed West, writing about Pearce's conversion in ''The Catholic Herald

The ''Catholic Herald'' is a London-based Roman Catholic monthly newspaper and starting December 2014 a magazine, published in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and, formerly, the United States. It reports a total circulation of abo ...

'' in 2010, called his subject "a happy man" and one of the English-speaking world

Speakers of English are also known as Anglophones, and the countries where English is natively spoken by the majority of the population are termed the '' Anglosphere''. Over two billion people speak English , making English the largest languag ...

's leading Catholic biographers, hard to square with "the figure familiar to anti-racist campaigners of the Seventies and Eighties: the pugnacious and frightening leader of the Young National Front".

Biographer

Catholic subjects

As a Catholic author, Pearce has focused mainly on the life and work of English Catholic writers, such asJ. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien (, ; 3 January 1892 – 2 September 1973) was an English writer and philology, philologist. He was the author of the high fantasy works ''The Hobbit'' and ''The Lord of the Rings''.

From 1925 to 1945, Tolkien was ...

, G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

and Hilaire Belloc

Joseph Hilaire Pierre René Belloc (, ; 27 July 187016 July 1953) was a Franco-English writer and historian of the early twentieth century. Belloc was also an orator, poet, sailor, satirist, writer of letters, soldier, and political activist. H ...

. ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'' commented that ''Old Thunder: A Life of Hilaire Belloc'' "skates over" Belloc's anti-semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, "the central disfiguring fact of his oeuvre".

He chose the pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

"Robert Williamson" after a character in the Ulster Loyalist

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a uni ...

ballad ''The Old Orange Flute

The Old Orange Flute (also spelt Ould Orange Flute) is a folk song originating in Ireland. It is often associated with the Orange Order. Despite this, its humour ensured a certain amount of cross-community appeal, especially in the period before th ...

'', who, like Pearce, is an Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

member who converts to Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwide . It is am ...

. Pearce's biography of G. K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

, ''Wisdom and Innocence: A Life of G. K. Chesterton'', was published, under the pseudonym

A pseudonym (; ) or alias () is a fictitious name that a person or group assumes for a particular purpose, which differs from their original or true name (orthonym). This also differs from a new name that entirely or legally replaces an individua ...

of Robert Williamson, by Hodder and Stoughton

Hodder & Stoughton is a British publishing house, now an imprint of Hachette.

History

Early history

The firm has its origins in the 1840s, with Matthew Hodder's employment, aged 14, with Messrs Jackson and Walford, the official publisher ...

in 1996. Jay P. Corrin, reviewing the book for ''The Catholic Historical Review

''The Catholic Historical Review'' (CHR) is the official organ of the American Catholic Historical Association. It was established at The Catholic University of America in 1915 by Thomas Joseph Shahan and Peter Guilday and is published quarterly by ...

'', called it "a venture of love and high praise", but which adds little to existing biographies. Its contribution, Corrin wrote, is its focus on Chesterton's religious vision and personal relationships, contrasting his friendly style with the combative Belloc.

Pearce's 2000 biography ''The Unmasking of Oscar Wilde'' focused on the conflict between Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

's homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

and his lifelong attraction to the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and how it was finally settled by his reception into the Church on his deathbed in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

.

In a review for ''The Wildean'', Michael Seeney, described Pearce's biography, as "badly written and muddled", "woefully poorly annotated" and using "odd sources without question". Seeney wrote that it "does not 'unmask' anything", but contains too much "cod psychology" and "hyperbolic cliché" to be a "workmanlike biography".

In 2001, Pearce published a biography of Anglo

Anglo is a prefix indicating a relation to, or descent from, the Angles, England, English culture, the English people or the English language, such as in the term '' Anglosphere''. It is often used alone, somewhat loosely, to refer to people ...

-South African __NOTOC__

South African may relate to:

* The nation of South Africa

* South African Airways

* South African English

* South African people

* Languages of South Africa

* Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the Afric ...

poet and Catholic convert Roy Campbell, followed in 2003 by an edited anthology of Campbell's poetry and verse translations.

Tolkien

Pearce has also written and published a variety of books ofTolkien studies

''Tolkien Studies: An Annual Scholarly Review'' is an academic journal publishing papers on the works of J. R. R. Tolkien. The journal's founding editors are Douglas A. Anderson, Michael D. C. Drout, and Verlyn Flieger, and the current editors ...

. His essay ''Letting the Catholic Out of the Baggins'' discusses why. In 1997, the British people, in a nationwide poll by the Folio Society

The Folio Society is a London-based publisher, founded by Charles Ede in 1947 and incorporated in 1971. Formerly privately owned, it operates as an employee ownership trust since 2021.

It produces illustrated hardback editions of classic fict ...

, voted ''The Lord of the Rings

''The Lord of the Rings'' is an epic high-fantasy novel by English author and scholar J. R. R. Tolkien. Set in Middle-earth, intended to be Earth at some time in the distant past, the story began as a sequel to Tolkien's 1937 children's boo ...

'' the greatest book of the 20th-century and the outraged reactions of literary celebrities such as Howard Jacobson

Howard Eric Jacobson (born 25 August 1942) is a British novelist and journalist. He is known for writing comic novels that often revolve around the dilemmas of British Jewish characters.Ragi, K. R., "Howard Jacobson's ''The Finkler Question'' a ...

, Griff Rhys Jones

Griffith Rhys Jones (born 16 November 1953) is a Welsh comedian, writer, actor, and television presenter. He starred in a number of television series with his comedy partner, Mel Smith. Rhys Jones came to national attention in the 1980s for h ...

, and Germaine Greer

Germaine Greer (; born 29 January 1939) is an Australian writer and public intellectual, regarded as one of the major voices of the radical feminist movement in the latter half of the 20th century.

Specializing in English and women's literatu ...

, inspired Pearce to write the books ''Tolkien: Man and Myth'' (1998), ''Tolkien, a Celebration'' (1999) and ''Bilbo's Journey: Discovering the Hidden Meaning in The Hobbit'' (2012). All of Pearce's Tolkien-themed books consider his subject's person and writings from a Catholic perspective. Bradley J. Birzer

Bradley J. Birzer (born 1967) is an American historian. He is a History professor and the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in American Studies at Hillsdale College, the author of five books and the co-founder of ''The Imaginative Conservative''. He is kno ...

writes in ''The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia

The ''J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment'', edited by Michael D. C. Drout, was published by Routledge in 2006. A team of 127 Tolkien scholars on 720 pages cover topics of Tolkien's fiction, his academic works, his ...

'' that scholars had hardly discussed Tolkien's Catholicism until Pearce's ''Tolkien: Man and Myth'', describing the book as "outstanding", treating ''The Lord of the Rings'' as a "theological thriller" that "inspired a whole new wave of Christian evaluations".

Pearce has credited his previously published books of Tolkien studies

''Tolkien Studies: An Annual Scholarly Review'' is an academic journal publishing papers on the works of J. R. R. Tolkien. The journal's founding editors are Douglas A. Anderson, Michael D. C. Drout, and Verlyn Flieger, and the current editors ...

and, "the wave of Tolkien enthusiasm", caused by Peter Jackson

Sir Peter Robert Jackson (born 31 October 1961) is a New Zealand film director, screenwriter and producer. He is best known as the director, writer and producer of the ''Lord of the Rings'' trilogy (2001–2003) and the ''Hobbit'' trilogy ( ...

's film adaptation

A film adaptation is the transfer of a work or story, in whole or in part, to a feature film. Although often considered a type of derivative work, film adaptation has been conceptualized recently by academic scholars such as Robert Stam as a dial ...

of ''The Lord of the Rings'', with making Pearce into a celebrity intellectual following his 2001 emigration from England to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

.

New life, new world

Pearce married Susannah Brown, anIrish-American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

woman with family roots in Dungannon

Dungannon () is a town in County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. It is the second-largest town in the county (after Omagh) and had a population of 14,340 at the 2011 Census. The Dungannon and South Tyrone Borough Council had its headquarters in the ...

, County Tyrone

County Tyrone (; ) is one of the six Counties of Northern Ireland, counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the thirty-two traditional Counties of Ireland, counties of Ireland. It is no longer used as an admini ...

, in St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church in Steubenville, Ohio

Steubenville is a city in and the county seat of Jefferson County, Ohio, United States. Located along the Ohio River 33 miles west of Pittsburgh, it had a population of 18,161 at the 2020 census. The city's name is derived from Fort Steuben, a 1 ...

in April 2001. They have two children. He then received a telephone call and a job offer from the President of Ave Maria College

''Alta Velocidad Española'' (''AVE'') is a service of high-speed rail in Spain operated by Renfe, the Spanish national railway company, at speeds of up to . As of December 2021, the Spanish high-speed rail network, on part of which the AVE ...

in Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

. The Pearces arrived in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

on September 7, 2001. Pearce recalls that his first day of teaching coincided with the September 11 attacks

The September 11 attacks, commonly known as 9/11, were four coordinated suicide terrorist attacks carried out by al-Qaeda against the United States on Tuesday, September 11, 2001. That morning, nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercia ...

, "making my arrival in the States something of a baptism of fire." The first issue of the Catholic literary magazine

A literary magazine is a periodical devoted to literature in a broad sense. Literary magazines usually publish short stories, poetry, and essays, along with literary criticism, book reviews, biographical profiles of authors, interviews and letter ...

the ''St. Austin Review

The ''St. Austin Review'' (StAR) is a Catholic international review of culture and ideas. It is edited by author, columnist and EWTN TV host Joseph Pearce and literary scholar Robert Asch. StAR includes book reviews, discussions on Christian art ...

'', which Pearce has coedited ever since alongside Robert Asch

Robert Charles Asch (born 1968) is an English Catholic writer, literary critic, and scholar.

Early life

Robert Asch was born in London in 1968, into a family of mixed Canadian- and Austrian Jewish descent. His parents were both opera singers. He ...

, was also published in September 2001.

Pearce was the host of the 2009 EWTN

The Eternal Word Television Network, more commonly known by its initials EWTN, is an American basic cable television network which presents around-the-clock Catholic-themed programming. It is not only the largest Catholic television network in ...

television series ''The Quest for Shakespeare

''The Quest for Shakespeare'' is a television series, television documentary series shown on cable channel EWTN. It is written and presented by author Joseph Pearce about William Shakespeare, and specifically the evidence that his Shakespeare's re ...

''. Based upon his eponymous book, the show is concerned with Pearce's belief that Shakespeare was a Catholic.

In a 2014 essay, Pearce announced that he had become an American citizen.

In his 2017 stage play

A play is a work of drama, usually consisting mostly of dialogue between Character (arts), characters and intended for theatre, theatrical performance rather than just Reading (process), reading. The writer of a play is called a playwright.

Pla ...

''Death Comes for the War Poets'', according to ''Catholic Arts Today'', Pearce weaves "a verse tapestry," about the military and spiritual journeys of war poet

A war poet is a poet who participates in a war and writes about their experiences, or a non-combatant who writes poems about war. While the term is applied especially to those who served during the First World War, the term can be applied to a p ...

s Siegfried Sassoon

Siegfried Loraine Sassoon (8 September 1886 – 1 September 1967) was an English war poet, writer, and soldier. Decorated for bravery on the Western Front, he became one of the leading poets of the First World War. His poetry both describ ...

and Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced by ...

.

In a 2022 interview with Pearce, Polish journalist Anna Szyda from the literary magazine

A literary magazine is a periodical devoted to literature in a broad sense. Literary magazines usually publish short stories, poetry, and essays, along with literary criticism, book reviews, biographical profiles of authors, interviews and letter ...

''Magna Polonia'' explained that the nihilism

Nihilism (; ) is a philosophy, or family of views within philosophy, that rejects generally accepted or fundamental aspects of human existence, such as objective truth, knowledge, morality, values, or meaning. The term was popularized by Ivan ...

of modern American poetry

American poetry refers to the poetry of the United States. It arose first as efforts by American colonists to add their voices to English poetry in the 17th century, well before the constitutional unification of the Thirteen Colonies (although ...

is widely noticed and commented upon in the Third Polish Republic

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* Hig ...

as reflecting, "the deleterious influence of the contemporary civilisation on the American soul." In response, Pearce described "the neo-formalist revival" inspired by the late Richard Wilbur

Richard Purdy Wilbur (March 1, 1921 – October 14, 2017) was an American poet and literary translator. One of the foremost poets of his generation, Wilbur's work, composed primarily in traditional forms, was marked by its wit, charm, and gentle ...

and how it has been reflected in recent verse by the Catholic poets whom he and Robert Asch

Robert Charles Asch (born 1968) is an English Catholic writer, literary critic, and scholar.

Early life

Robert Asch was born in London in 1968, into a family of mixed Canadian- and Austrian Jewish descent. His parents were both opera singers. He ...

publish in the ''St. Austin Review

The ''St. Austin Review'' (StAR) is a Catholic international review of culture and ideas. It is edited by author, columnist and EWTN TV host Joseph Pearce and literary scholar Robert Asch. StAR includes book reviews, discussions on Christian art ...

''. Pearce said that the Catholic faith and optimism

Optimism is an attitude reflecting a belief or hope that the outcome of some specific endeavor, or outcomes in general, will be positive, favorable, and desirable. A common idiom used to illustrate optimism versus pessimism is a glass filled wi ...

of the younger generation of Catholic poets made him feel hope for the future.

In July 2022, Pearce was a speaker at the 41st Annual Conference of the American Chesterton Society in Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

. Pearce's lecture was titled "How Chesterton Saved Me from anti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

".Works

Publications

* * * * * * * * * * Published in the United States as * Published in the United States as* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

References

Primary

Secondary

External links

*Autobiographical page

''Saint Austin Review''

* Clips of Joseph Pearce speaking about his conversion

1

Joseph Pearce speaks about his conversion

EWTN's page for the TV show

Tolkien's Lord Of The Rings — A Catholic Worldview

{{DEFAULTSORT:Pearce, Joseph 1961 births American Roman Catholic poets American modernist poets Ave Maria University faculty British expatriate academics in the United States British modernist poets Catholic philosophers Converts to Roman Catholicism from atheism or agnosticism Distributism English biographers English emigrants to the United States English Catholic poets English Roman Catholics English Roman Catholic writers Formalist poets Living people National Front (UK) politicians Naturalized citizens of the United States People from Dagenham People from Nashville, Tennessee Shakespearean scholars Sonneteers Tolkien studies