Japanese-language Works on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

is spoken natively by about 128 million people, primarily by Japanese people and primarily in

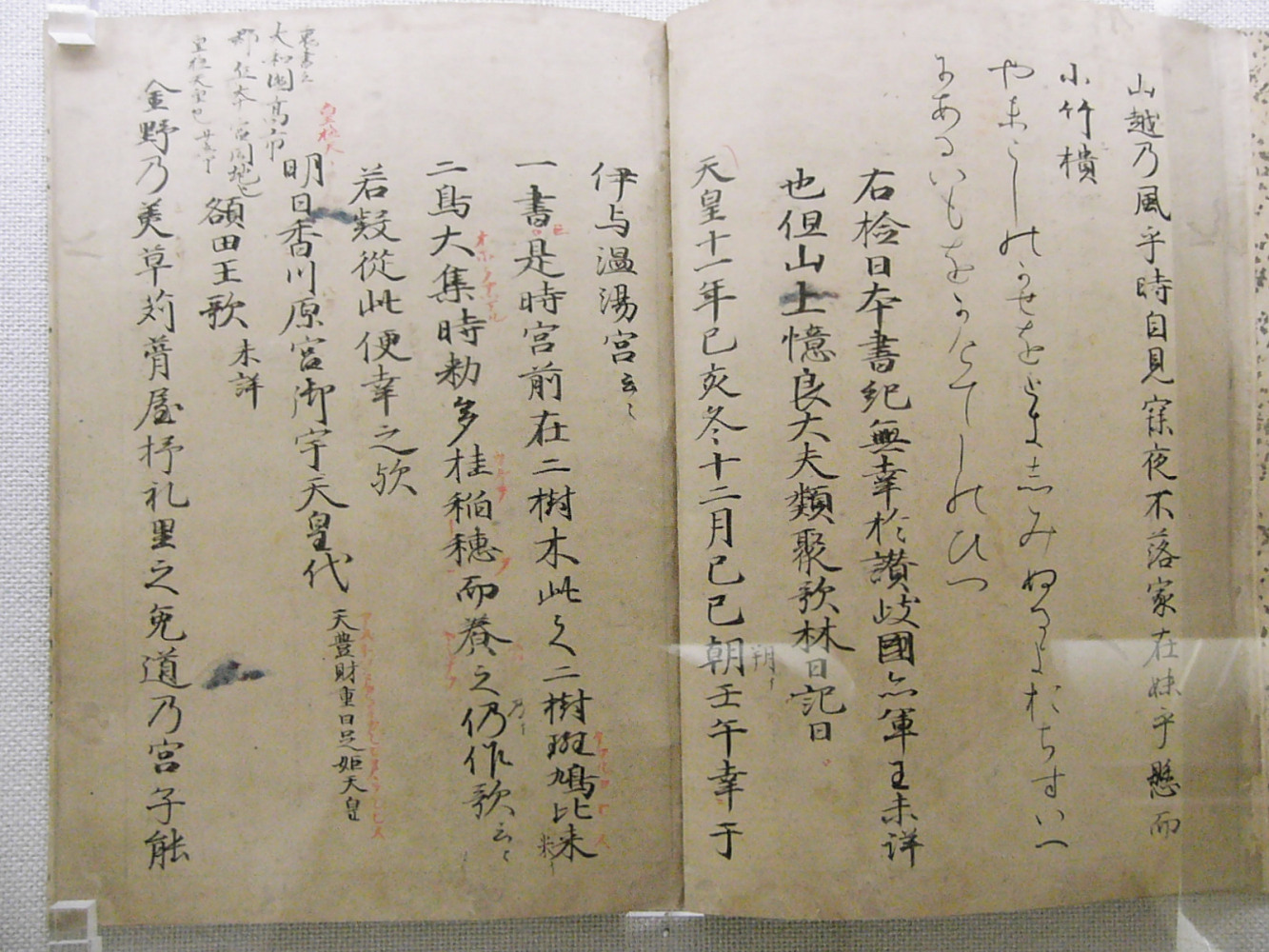

The Chinese writing system was imported to Japan from Baekje around the start of the fifth century, alongside Buddhism. The earliest texts were written in Classical Chinese, although some of these were likely intended to be read as Japanese using the kanbun method, and show influences of Japanese grammar such as Japanese word order. The earliest text, the ''

The Chinese writing system was imported to Japan from Baekje around the start of the fifth century, alongside Buddhism. The earliest texts were written in Classical Chinese, although some of these were likely intended to be read as Japanese using the kanbun method, and show influences of Japanese grammar such as Japanese word order. The earliest text, the ''

Early Middle Japanese is the Japanese of the Heian period, from 794 to 1185. It formed the basis for the literary standard of

Early Middle Japanese is the Japanese of the Heian period, from 794 to 1185. It formed the basis for the literary standard of

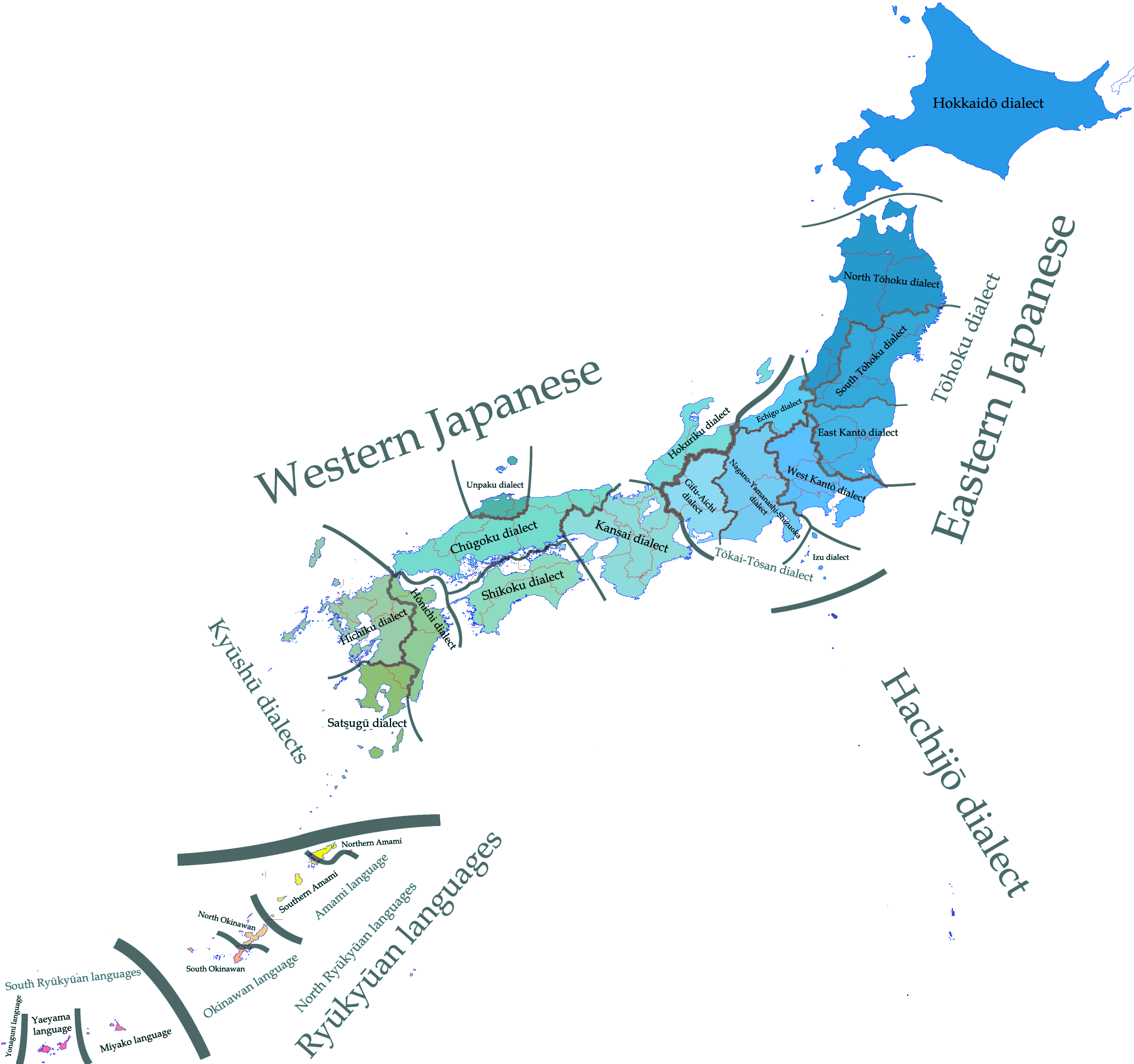

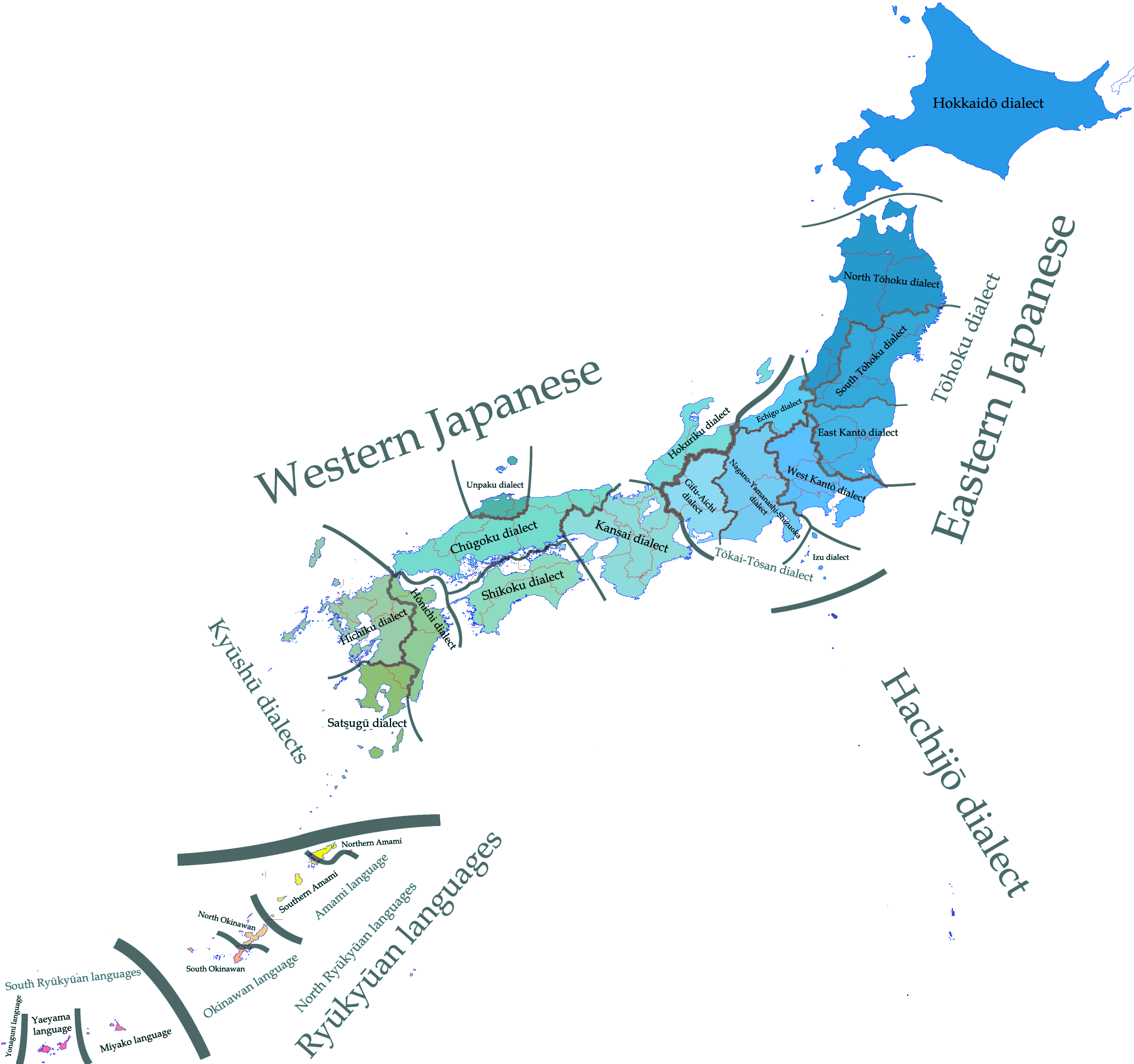

Japanese dialects typically differ in terms of pitch accent, inflectional morphology, vocabulary, and particle usage. Some even differ in vowel and consonant inventories, although this is uncommon.

In terms of mutual intelligibility, a survey in 1967 found the four most unintelligible dialects (excluding

Japanese dialects typically differ in terms of pitch accent, inflectional morphology, vocabulary, and particle usage. Some even differ in vowel and consonant inventories, although this is uncommon.

In terms of mutual intelligibility, a survey in 1967 found the four most unintelligible dialects (excluding

At first, the Japanese wrote in Classical Chinese, with Japanese names represented by characters used for their meanings and not their sounds. Later, during the 7th century AD, the Chinese-sounding phoneme principle was used to write pure Japanese poetry and prose, but some Japanese words were still written with characters for their meaning and not the original Chinese sound. This is when the history of Japanese as a written language begins in its own right. By this time, the Japanese language was already very distinct from the Ryukyuan languages.

An example of this mixed style is the

At first, the Japanese wrote in Classical Chinese, with Japanese names represented by characters used for their meanings and not their sounds. Later, during the 7th century AD, the Chinese-sounding phoneme principle was used to write pure Japanese poetry and prose, but some Japanese words were still written with characters for their meaning and not the original Chinese sound. This is when the history of Japanese as a written language begins in its own right. By this time, the Japanese language was already very distinct from the Ryukyuan languages.

An example of this mixed style is the

"Sotomayor, Denzel Washington, GE CEO Speak to Graduates,"

C-SPAN (US). 30 May 2011; retrieved 2011-05-30 International interest in the Japanese language dates from the 19th century but has become more prevalent following Japan's economic bubble of the 1980s and the global popularity of Japanese popular culture (such as anime and video games) since the 1990s. As of 2015, more than 3.6 million people studied the language worldwide, primarily in East and Southeast Asia. Nearly one million Chinese, 745,000 Indonesians, 556,000 South Koreans and 357,000 Australians studied Japanese in lower and higher educational institutions. Between 2012 and 2015, considerable growth of learners originated in

"Japanese,"

in ''Dictionary of Languages: the Definitive Reference to More than 400 Languages.'' New York: Columbia University Press. ; * * * * Kuno, Susumu (1973). ''The structure of the Japanese language''. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. . * Kuno, Susumu. (1976). "Subject, theme, and the speaker's empathy: A re-examination of relativization phenomena," in Charles N. Li (Ed.), ''Subject and topic'' (pp. 417–444). New York: Academic Press. . * McClain, Yoko Matsuoka. (1981). ''Handbook of modern Japanese grammar:'' 'Kōgo Nihon bumpō'' Tokyo: Hokuseido Press. . * Miller, Roy (1967). ''The Japanese language''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. * Miller, Roy (1980). ''Origins of the Japanese language: Lectures in Japan during the academic year, 1977–78''. Seattle: University of Washington Press. . * Mizutani, Osamu; & Mizutani, Nobuko (1987). ''How to be polite in Japanese:'' 'Nihongo no keigo'' Tokyo: The Japan Times. . * * * * Shibamoto, Janet S. (1985). ''Japanese women's language''. New York: Academic Press. . Graduate Level * (pbk). * Tsujimura, Natsuko (1996). ''An introduction to Japanese linguistics''. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. (hbk); (pbk). Upper Level Textbooks * Tsujimura, Natsuko (Ed.) (1999). ''The handbook of Japanese linguistics''. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. . Readings/Anthologies *

National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics

Japanese Language Student's Handbook

* {{Authority control Agglutinative languages Languages attested from the 8th century Languages of Japan Languages of Palau Subject–object–verb languages

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, the only country where it is the national language. Japanese belongs to the Japonic or Japanese- Ryukyuan language family. There have been many attempts to group the Japonic languages with other families such as the Ainu

Ainu or Aynu may refer to:

*Ainu people, an East Asian ethnic group of Japan and the Russian Far East

*Ainu languages, a family of languages

**Ainu language of Hokkaido

**Kuril Ainu language, extinct language of the Kuril Islands

**Sakhalin Ainu la ...

, Austroasiatic, Koreanic

Koreanic is a small language family consisting of the Korean language, Korean and Jeju language, Jeju languages. The latter is often described as a dialect of Korean, but is distinct enough to be considered a separate language. Alexander Vovin s ...

, and the now-discredited Altaic, but none of these proposals has gained widespread acceptance.

Little is known of the language's prehistory, or when it first appeared in Japan. Chinese documents from the 3rd century AD recorded a few Japanese words, but substantial Old Japanese texts did not appear until the 8th century. From the Heian period (794–1185), there was a massive influx of Sino-Japanese vocabulary into the language, affecting the phonology of Early Middle Japanese. Late Middle Japanese (1185–1600) saw extensive grammatical changes and the first appearance of European loanwords. The basis of the standard dialect moved from the Kansai

The or the , lies in the southern-central region of Japan's main island Honshu, Honshū. The region includes the Prefectures of Japan, prefectures of Nara Prefecture, Nara, Wakayama Prefecture, Wakayama, Kyoto Prefecture, Kyoto, Osaka Prefectur ...

region to the Edo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

region (modern Tokyo) in the Early Modern Japanese period (early 17th century–mid 19th century). Following the end of Japan's self-imposed isolation in 1853, the flow of loanwords from European languages increased significantly, and words from English roots have proliferated.

Japanese is an agglutinative, mora

Mora may refer to:

People

* Mora (surname)

Places Sweden

* Mora, Säter, Sweden

* Mora, Sweden, the seat of Mora Municipality

* Mora Municipality, Sweden

United States

* Mora, Louisiana, an unincorporated community

* Mora, Minnesota, a city

* M ...

-timed language with relatively simple phonotactics, a pure vowel

A monophthong ( ; , ) is a pure vowel sound, one whose articulation at both beginning and end is relatively fixed, and which does not glide up or down towards a new position of articulation. The monophthongs can be contrasted with diphthongs, wh ...

system, phonemic vowel and consonant length, and a lexically significant pitch-accent

A pitch-accent language, when spoken, has word accents in which one syllable in a word or morpheme is more prominent than the others, but the accentuated syllable is indicated by a contrasting pitch ( linguistic tone) rather than by loudness ...

. Word order is normally subject–object–verb

Subject ( la, subiectus "lying beneath") may refer to:

Philosophy

*'' Hypokeimenon'', or ''subiectum'', in metaphysics, the "internal", non-objective being of a thing

**Subject (philosophy), a being that has subjective experiences, subjective con ...

with particles marking the grammatical function of words, and sentence structure is topic–comment. Sentence-final particles are used to add emotional or emphatic impact, or form questions. Nouns have no grammatical number or gender, and there are no articles

Article often refers to:

* Article (grammar), a grammatical element used to indicate definiteness or indefiniteness

* Article (publishing), a piece of nonfictional prose that is an independent part of a publication

Article may also refer to:

G ...

. Verbs are conjugated, primarily for tense and voice, but not person. Japanese adjectives

This article deals with Japanese equivalents of English adjectives.

Types of adjective

In Japanese, nouns and verbs can modify nouns, with nouns taking the 〜の particles when functioning attributively (in the genitive case), and verbs in the ...

are also conjugated. Japanese has a complex system of honorifics, with verb forms and vocabulary to indicate the relative status of the speaker, the listener, and persons mentioned.

The Japanese writing system combines Chinese characters, known as , with two unique syllabaries

In the linguistic study of written languages, a syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent the syllables or (more frequently) moras which make up words.

A symbol in a syllabary, called a syllabogram, typically represents an (option ...

(or moraic

A mora (plural ''morae'' or ''moras''; often symbolized μ) is a basic timing (linguistics), timing unit in the phonology of some spoken languages, equal to or shorter than a syllable. For example, a short syllable such as ''ba'' consists of one m ...

scripts) derived by the Japanese from the more complex Chinese characters: ( or , 'simple characters') and ( or , 'partial characters'). Latin script ( ) is also used in a limited fashion (such as for imported acronyms) in Japanese writing. The numeral system uses mostly Arabic numerals

Arabic numerals are the ten numerical digits: , , , , , , , , and . They are the most commonly used symbols to write Decimal, decimal numbers. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers ...

, but also traditional Chinese numerals.

History

Prehistory

Proto-Japonic, the common ancestor of the Japanese and Ryukyuan languages, is thought to have been brought to Japan by settlers coming from the Korean peninsula sometime in the early- to mid-4th century BC (the Yayoi period), replacing the languages of the original Jōmon inhabitants, including the ancestor of the modernAinu language

Ainu (, ), or more precisely Hokkaido Ainu, is a language spoken by a few elderly members of the Ainu people on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido. It is a member of the Ainu language family, itself considered a language family isolate ...

. Because writing had yet to be introduced from China, there is no direct evidence, and anything that can be discerned about this period must be based on internal reconstruction from Old Japanese, or comparison with the Ryukyuan languages and Japanese dialects.

Old Japanese

Kojiki

The , also sometimes read as or , is an early Japanese chronicle of myths, legends, hymns, genealogies, oral traditions, and semi-historical accounts down to 641 concerning the origin of the Japanese archipelago, the , and the Japanese imperia ...

'', dates to the early eighth century, and was written entirely in Chinese characters, which are used to represent, at different times, Chinese, ''kanbun'', and Old Japanese. As in other texts from this period, the Old Japanese sections are written in Man'yōgana, which uses '' kanji'' for their phonetic as well as semantic values.

Based on the Man'yōgana system, Old Japanese can be reconstructed as having 88 distinct syllables. Texts written with Man'yōgana use two different sets of ''kanji'' for each of the syllables now pronounced (ki), (hi), (mi), (ke), (he), (me), (ko), (so), (to), (no), (mo), (yo) and (ro). (The ''Kojiki'' has 88, but all later texts have 87. The distinction between mo1 and mo2 apparently was lost immediately following its composition.) This set of syllables shrank to 67 in Early Middle Japanese, though some were added through Chinese influence. Man'yōgana also has a symbol for , which merges with before the end of the period.

Several fossilizations of Old Japanese grammatical elements remain in the modern language – the genitive particle ''tsu'' (superseded by modern ''no'') is preserved in words such as ''matsuge'' ("eyelash", lit. "hair of the eye"); modern ''mieru'' ("to be visible") and ''kikoeru'' ("to be audible") retain a mediopassive suffix -''yu(ru)'' (''kikoyu'' → ''kikoyuru'' (the attributive form, which slowly replaced the plain form starting in the late Heian period) → ''kikoeru'' (all verbs with the ''shimo-nidan'' conjugation pattern underwent this same shift in Early Modern Japanese)); and the genitive particle ''ga'' remains in intentionally archaic speech.

Early Middle Japanese

Early Middle Japanese is the Japanese of the Heian period, from 794 to 1185. It formed the basis for the literary standard of

Early Middle Japanese is the Japanese of the Heian period, from 794 to 1185. It formed the basis for the literary standard of Classical Japanese

The classical Japanese language ( ''bungo'', "literary language"), also called "old writing" ( ''kobun''), sometimes simply called "Medieval Japanese" is the literary form of the Japanese language that was the standard until the early Shōwa pe ...

, which remained in common use until the early 20th century.

During this time, Japanese underwent numerous phonological developments, in many cases instigated by an influx of Chinese loanwords. These included phonemic length distinction for both consonants and vowels, palatal consonants (e.g. ''kya'') and labial consonant clusters (e.g. ''kwa''), and closed syllables. This had the effect of changing Japanese into a mora-timed language.

Late Middle Japanese

Late Middle Japanese covers the years from 1185 to 1600, and is normally divided into two sections, roughly equivalent to theKamakura period

The is a period of Japanese history that marks the governance by the Kamakura shogunate, officially established in 1192 in Kamakura by the first ''shōgun'' Minamoto no Yoritomo after the conclusion of the Genpei War, which saw the struggle betwee ...

and the Muromachi period, respectively. The later forms of Late Middle Japanese are the first to be described by non-native sources, in this case the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

and Franciscan missionaries; and thus there is better documentation of Late Middle Japanese phonology than for previous forms (for instance, the '' Arte da Lingoa de Iapam''). Among other sound changes, the sequence merges to , in contrast with ; is reintroduced from Chinese; and merges with . Some forms rather more familiar to Modern Japanese speakers begin to appear – the continuative ending -''te'' begins to reduce onto the verb (e.g. ''yonde'' for earlier ''yomite''), the -k- in the final syllable of adjectives drops out (''shiroi'' for earlier ''shiroki''); and some forms exist where modern standard Japanese has retained the earlier form (e.g. ''hayaku'' > ''hayau'' > ''hayɔɔ'', where modern Japanese just has ''hayaku'', though the alternative form is preserved in the standard greeting ''o-hayō gozaimasu'' "good morning"; this ending is also seen in ''o-medetō'' "congratulations", from ''medetaku'').

Late Middle Japanese has the first loanwords from European languages – now-common words borrowed into Japanese in this period include ''pan'' ("bread") and ''tabako'' ("tobacco", now "cigarette"), both from Portuguese.

Modern Japanese

Modern Japanese is considered to begin with the Edo period (which spanned from 1603 to 1867). Since Old Japanese, the ''de facto'' standard Japanese had been the Kansai dialect, especially that of Kyoto. However, during the Edo period, Edo (now Tokyo) developed into the largest city in Japan, and the Edo-area dialect became standard Japanese. Since the end of Japan's self-imposed isolation in 1853, the flow of loanwords from European languages has increased significantly. The period since 1945 has seen many words borrowed from other languagessuch as German, Portuguese and English. Many English loan words especially relate to technologyfor example, ''pasokon'' (short for "personal computer"), ''intānetto'' ("internet"), and ''kamera'' ("camera"). Due to the large quantity of English loanwords, modern Japanese has developed a distinction between and , and and , with the latter in each pair only found in loanwords.Geographic distribution

Although Japanese is spoken almost exclusively in Japan, it has been spoken outside. Before and during World War II, through Japanese annexation of Taiwan and Korea, as well as partial occupation ofChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, the Philippines, and various Pacific islands, locals in those countries learned Japanese as the language of the empire. As a result, many elderly people in these countries can still speak Japanese.

Japanese emigrant communities (the largest of which are to be found in Brazil, with 1.4 million to 1.5 million Japanese immigrants and descendants, according to Brazilian IBGE data, more than the 1.2 million of the United States) sometimes employ Japanese as their primary language. Approximately 12% of Hawaii residents speak Japanese, with an estimated 12.6% of the population of Japanese ancestry in 2008. Japanese emigrants can also be found in Peru, Argentina, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

(especially in the eastern states), Canada (especially in Vancouver where 1.4% of the population has Japanese ancestry), the United States (notably Hawaii, where 16.7% of the population has Japanese ancestry, and California), and the Philippines (particularly in Davao region

Davao Region, formerly called Southern Mindanao ( ceb, Rehiyon sa Davao; fil, Rehiyon ng Davao), is an administrative region in the Philippines, designated as Region XI. It is situated at the southeastern portion of Mindanao and comprises fi ...

and Laguna

Laguna (Italian and Spanish for lagoon) may refer to:

People

* Abe Laguna (born 1992), American DJ known as Ookay

* Andrés Laguna (1499–1559), Spanish physician, pharmacologist, and botanist

* Ana Laguna (born 1955), Spanish-Swedish ballet d ...

province).

Official status

Japanese has no official status in Japan, but is the ''de facto'' national language of the country. There is a form of the language considered standard: , meaning "standard Japanese", or , "common language". The meanings of the two terms are almost the same. ''Hyōjungo'' or ''kyōtsūgo'' is a conception that forms the counterpart of dialect. This normative language was born after the from the language spoken in the higher-class areas of Tokyo (see Yamanote). ''Hyōjungo'' is taught in schools and used on television and in official communications. It is the version of Japanese discussed in this article. Formerly, standard was different from . The two systems have different rules of grammar and some variance in vocabulary. ''Bungo'' was the main method of writing Japanese until about 1900; since then ''kōgo'' gradually extended its influence and the two methods were both used in writing until the 1940s. ''Bungo'' still has some relevance for historians, literary scholars, and lawyers (many Japanese laws that survived World War II are still written in ''bungo'', although there are ongoing efforts to modernize their language). ''Kōgo'' is the dominant method of both speaking and writing Japanese today, although ''bungo'' grammar and vocabulary are occasionally used in modern Japanese for effect. The 1982 state constitution of Angaur, Palau, names Japanese along with Palauan and English as an official language of the state. However, the results of the 2005 census show that in April 2005 there were no usual or legal residents of Angaur aged 5 or older who spoke Japanese at home at all.Dialects and mutual intelligibility

Japanese dialects typically differ in terms of pitch accent, inflectional morphology, vocabulary, and particle usage. Some even differ in vowel and consonant inventories, although this is uncommon.

In terms of mutual intelligibility, a survey in 1967 found the four most unintelligible dialects (excluding

Japanese dialects typically differ in terms of pitch accent, inflectional morphology, vocabulary, and particle usage. Some even differ in vowel and consonant inventories, although this is uncommon.

In terms of mutual intelligibility, a survey in 1967 found the four most unintelligible dialects (excluding Ryūkyūan languages

The , also Lewchewan or Luchuan (), are the indigenous languages of the Ryukyu Islands, the southernmost part of the Japanese archipelago. Along with the Japanese language and the Hachijō language, they make up the Japonic language family.

Al ...

and Tohoku dialects) to students from Greater Tokyo are the Kiso dialect (in the deep mountains of Nagano Prefecture

is a landlocked prefecture of Japan located in the Chūbu region of Honshū. Nagano Prefecture has a population of 2,052,493 () and has a geographic area of . Nagano Prefecture borders Niigata Prefecture to the north, Gunma Prefecture to the ...

), the Himi dialect (in Toyama Prefecture), the Kagoshima dialect and the Maniwa

270px, Maniwa City Hall

270px, Aerial view of Kuse area of Maniwa

is a city located in Okayama Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 42,477 in 17568 households and a population density of 51 persons per km². The total are ...

dialect (in Okayama Prefecture

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Chūgoku region of Honshu. Okayama Prefecture has a population of 1,906,464 (1 February 2018) and has a geographic area of 7,114 Square kilometre, km2 (2,746 sq mi). Okayama Prefectur ...

). The survey is based on recordings of 12- to 20- second long, of 135 to 244 phonemes, which 42 students listened and translated word-by-word. The listeners are all Keio University

, mottoeng = The pen is mightier than the sword

, type = Private research coeducational higher education institution

, established = 1858

, founder = Yukichi Fukuzawa

, endowmen ...

students who grew up in the Kanto region

Kantō (Japanese)

Kanto is a simplified spelling of , a Japanese word, only omitting the diacritics.

In Japan

Kantō may refer to:

*Kantō Plain

*Kantō region

*Kantō-kai, organized crime group

*Kanto (Pokémon), a geographical region in the ' ...

.

There are some language islands in mountain villages or isolated islands such as Hachijō-jima island whose dialects are descended from the Eastern dialect of Old Japanese. Dialects of the Kansai region are spoken or known by many Japanese, and Osaka dialect in particular is associated with comedy (see Kansai dialect). Dialects of Tōhoku and North Kantō are associated with typical farmers.

The Ryūkyūan languages

The , also Lewchewan or Luchuan (), are the indigenous languages of the Ryukyu Islands, the southernmost part of the Japanese archipelago. Along with the Japanese language and the Hachijō language, they make up the Japonic language family.

Al ...

, spoken in Okinawa and the Amami Islands (politically part of Kagoshima), are distinct enough to be considered a separate branch of the Japonic family; not only is each language unintelligible to Japanese speakers, but most are unintelligible to those who speak other Ryūkyūan languages. However, in contrast to linguists, many ordinary Japanese people tend to consider the Ryūkyūan languages as dialects of Japanese. The imperial court also seems to have spoken an unusual variant of the Japanese of the time. Most likely being the spoken form of Classical Japanese language, a writing style that was prevalent during the Heian period, but began decline during the late Meiji period. The Ryūkyūan languages

The , also Lewchewan or Luchuan (), are the indigenous languages of the Ryukyu Islands, the southernmost part of the Japanese archipelago. Along with the Japanese language and the Hachijō language, they make up the Japonic language family.

Al ...

are spoken by a decreasing number of elderly people so UNESCO classified it as endangered, because they could become extinct by 2050. Young people mostly use Japanese and cannot understand the Ryukyuan languages. Okinawan Japanese is a variant of Standard Japanese influenced by the Ryukyuan languages. It is the primary dialect spoken among young people in the Ryukyu Islands.

Modern Japanese has become prevalent nationwide (including the Ryūkyū islands) due to education, mass media, and an increase of mobility within Japan, as well as economic integration.

Classification

Japanese is a member of the Japonic language family, which also includes the Ryukyuan languages spoken in the Ryukyu Islands. As these closely related languages are commonly treated as dialects of the same language, Japanese is often called alanguage isolate

Language isolates are languages that cannot be classified into larger language families. Korean and Basque are two of the most common examples. Other language isolates include Ainu in Asia, Sandawe in Africa, and Haida in North America. The num ...

.

According to Martine Irma Robbeets, Japanese has been subject to more attempts to show its relation to other languages than any other language in the world. Since Japanese first gained the consideration of linguists in the late 19th century, attempts have been made to show its genealogical relation to languages or language families such as Ainu

Ainu or Aynu may refer to:

*Ainu people, an East Asian ethnic group of Japan and the Russian Far East

*Ainu languages, a family of languages

**Ainu language of Hokkaido

**Kuril Ainu language, extinct language of the Kuril Islands

**Sakhalin Ainu la ...

, Korean, Chinese, Tibeto-Burman, Uralic, Altaic (or Ural-Altaic), Mon–Khmer and Malayo-Polynesian. At the fringe, some linguists have suggested a link to Indo-European languages, including Greek, and to Lepcha. Main modern theories try to link Japanese either to northern Asian languages, like Korean or the proposed larger Altaic family, or to various Southeast Asian languages, especially Austronesian

Austronesian may refer to:

*The Austronesian languages

*The historical Austronesian peoples

The Austronesian peoples, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples in Taiwan, Maritime Southeast Asia, M ...

. None of these proposals have gained wide acceptance (and the Altaic family itself is now considered controversial). As it stands, only the link to Ryukyuan has wide support.

Other theories view the Japanese language as an early creole language formed through inputs from at least two distinct language groups, or as a distinct language of its own that has absorbed various aspects from neighbouring languages.

Phonology

Vowels

Japanese has five vowels, and vowel length is phonemic, with each having both a short and a long version. Elongated vowels are usually denoted with a line over the vowel (amacron

Macron may refer to:

People

* Emmanuel Macron (born 1977), president of France since 2017

** Brigitte Macron (born 1953), French teacher, wife of Emmanuel Macron

* Jean-Michel Macron (born 1950), French professor of neurology, father of Emmanu ...

) in rōmaji, a repeated vowel character in hiragana, or a chōonpu

The , also known as , , , or Katakana-Hiragana Prolonged Sound Mark by the Unicode Consortium, is a Japanese typographic symbols, Japanese symbol that indicates a ''chōon'', or a long vowel of two mora (linguistics), morae in length. Its form ...

succeeding the vowel in katakana. is compressed rather than protruded, or simply unrounded.

Consonants

Some Japanese consonants have several allophones, which may give the impression of a larger inventory of sounds. However, some of these allophones have since become phonemic. For example, in the Japanese language up to and including the first half of the 20th century, the phonemic sequence was palatalized and realized phonetically as , approximately ''chi'' ; however, now and are distinct, as evidenced by words like ''tī'' "Western-style tea" and ''chii'' "social status". The "r" of the Japanese language is of particular interest, ranging between an apicalcentral

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

tap and a lateral approximant. The "g" is also notable; unless it starts a sentence, it may be pronounced , in the Kanto prestige dialect and in other eastern dialects.

The phonotactics of Japanese are relatively simple. The syllable structure is (C)(G)V(C), that is, a core vowel surrounded by an optional onset consonant, a glide and either the first part of a geminate consonant (/, represented as Q) or a moraic nasal

A mora (plural ''morae'' or ''moras''; often symbolized μ) is a basic timing unit in the phonology of some spoken languages, equal to or shorter than a syllable. For example, a short syllable such as ''ba'' consists of one mora (''monomoraic''), ...

in the coda (/, represented as N).

The nasal is sensitive to its phonetic environment and assimilates to the following phoneme, with pronunciations including . Onset-glide clusters only occur at the start of syllables but clusters across syllables are allowed as long as the two consonants are the moraic nasal followed by a homorganic

In phonetics, a homorganic consonant (from ''homo-'' "same" and ''organ'' "(speech) organ") is a consonant sound that is articulated in the same place of articulation as another. For example, , and are homorganic consonants of one another since ...

consonant.

Japanese also includes a pitch accent, which is not represented in syllabic writing; for example ("chopsticks") and ("bridge") are both spelled (''hashi''), and are only differentiated by the tone contour.

Grammar

Sentence structure

Japanese word order is classified assubject–object–verb

Subject ( la, subiectus "lying beneath") may refer to:

Philosophy

*'' Hypokeimenon'', or ''subiectum'', in metaphysics, the "internal", non-objective being of a thing

**Subject (philosophy), a being that has subjective experiences, subjective con ...

. Unlike many Indo-European languages, the only strict rule of word order is that the verb must be placed at the end of a sentence (possibly followed by sentence-end particles). This is because Japanese sentence elements are marked with particles that identify their grammatical functions.

The basic sentence structure is topic–comment. For example, ''Kochira wa Tanaka-san desu'' (). ''kochira'' ("this") is the topic of the sentence, indicated by the particle ''wa''. The verb ''de aru'' (''desu'' is a contraction of its polite form ''de arimasu'') is a copula, commonly translated as "to be" or "it is" (though there are other verbs that can be translated as "to be"), though technically it holds no meaning and is used to give a sentence 'politeness'. As a phrase, ''Tanaka-san desu'' is the comment. This sentence literally translates to "As for this person, (it) is Mx Tanaka." Thus Japanese, like many other Asian languages, is often called a topic-prominent language, which means it has a strong tendency to indicate the topic separately from the subject, and that the two do not always coincide. The sentence ''Zō wa hana ga nagai'' () literally means, "As for elephant(s), (the) nose(s) (is/are) long". The topic is ''zō'' "elephant", and the subject is ''hana'' "nose".

In Japanese, the subject or object of a sentence need not be stated if it is obvious from context. As a result of this grammatical permissiveness, there is a tendency to gravitate towards brevity; Japanese speakers tend to omit pronouns on the theory they are inferred from the previous sentence, and are therefore understood. In the context of the above example, ''hana-ga nagai'' would mean "heir

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Officiall ...

noses are long," while ''nagai'' by itself would mean " heyare long." A single verb can be a complete sentence: ''Yatta!'' () " / we / they / etcdid t". In addition, since adjectives can form the predicate in a Japanese sentence (below), a single adjective can be a complete sentence: ''Urayamashii!'' () " 'mjealous f it".

While the language has some words that are typically translated as pronouns, these are not used as frequently as pronouns in some Indo-European languages, and function differently. In some cases Japanese relies on special verb forms and auxiliary verbs to indicate the direction of benefit of an action: "down" to indicate the out-group gives a benefit to the in-group; and "up" to indicate the in-group gives a benefit to the out-group. Here, the in-group includes the speaker and the out-group does not, and their boundary depends on context. For example, ''oshiete moratta'' () (literally, "explained" with a benefit from the out-group to the in-group) means " e/she/theyexplained tto e/us. Similarly, ''oshiete ageta'' () (literally, "explained" with a benefit from the in-group to the out-group) means " /weexplained tto im/her/them. Such beneficiary auxiliary verbs thus serve a function comparable to that of pronouns and prepositions in Indo-European languages to indicate the actor and the recipient of an action.

Japanese "pronouns" also function differently from most modern Indo-European pronouns (and more like nouns) in that they can take modifiers as any other noun may. For instance, one does not say in English:

The amazed he ran down the street. (grammatically incorrect insertion of a pronoun)But one ''can'' grammatically say essentially the same thing in Japanese:

This is partly because these words evolved from regular nouns, such as ''kimi'' "you" ( "lord"), ''anata'' "you" ( "that side, yonder"), and ''boku'' "I" ( "servant"). This is why some linguists do not classify Japanese "pronouns" as pronouns, but rather as referential nouns, much like Spanish ''usted'' (contracted from ''vuestra merced'', "your majestic) Majestic plural">plural">Majestic_plural">majestic<_a&g.html" ;"title="Majestic_plural.html" ;"title="flattering Majestic plural">majestic) Majestic plural">pluralgrace") or Portuguese ''o senhor''. Japanese personal pronouns are generally used only in situations requiring special emphasis as to who is doing what to whom. The choice of words used as pronouns is correlated with the sex of the speaker and the social situation in which they are spoken: men and women alike in a formal situation generally refer to themselves as ''watashi'' ( "private") or ''watakushi'' (also ), while men in rougher or intimate conversation are much more likely to use the word ''ore'' ( "oneself", "myself") or ''boku''. Similarly, different words such as ''anata'', ''kimi'', and ''omae'' (, more formally "the one before me") may refer to a listener depending on the listener's relative social position and the degree of familiarity between the speaker and the listener. When used in different social relationships, the same word may have positive (intimate or respectful) or negative (distant or disrespectful) connotations. Japanese often use titles of the person referred to where pronouns would be used in English. For example, when speaking to one's teacher, it is appropriate to use ''sensei'' (, teacher), but inappropriate to use ''anata''. This is because ''anata'' is used to refer to people of equal or lower status, and one's teacher has higher status.Transliteration: ''Odoroita kare wa michi o hashitte itta.'' (grammatically correct)

Inflection and conjugation

Japanese nouns have no grammatical number, gender or article aspect. The noun ''hon'' () may refer to a single book or several books; ''hito'' () can mean "person" or "people", and ''ki'' () can be "tree" or "trees". Where number is important, it can be indicated by providing a quantity (often with a counter word) or (rarely) by adding a suffix, or sometimes by duplication (e.g. , ''hitobito'', usually written with an iteration mark as ). Words for people are usually understood as singular. Thus ''Tanaka-san'' usually means ''Mx Tanaka''. Words that refer to people and animals can be made to indicate a group of individuals through the addition of a collective suffix (a noun suffix that indicates a group), such as ''-tachi'', but this is not a true plural: the meaning is closer to the English phrase "and company". A group described as ''Tanaka-san-tachi'' may include people not named Tanaka. Some Japanese nouns are effectively plural, such as ''hitobito'' "people" and ''wareware'' "we/us", while the word ''tomodachi'' "friend" is considered singular, although plural in form. Verbs are conjugated to show tenses, of which there are two: past and present (or non-past) which is used for the present and the future. For verbs that represent an ongoing process, the ''-te iru'' form indicates a continuous (or progressive) aspect, similar to the suffix ''ing'' in English. For others that represent a change of state, the ''-te iru'' form indicates a perfect aspect. For example, ''kite iru'' means "They have come (and are still here)", but ''tabete iru'' means "They are eating". Questions (both with an interrogative pronoun and yes/no questions) have the same structure as affirmative sentences, but with intonation rising at the end. In the formal register, the question particle ''-ka'' is added. For example, ''ii desu'' () "It is OK" becomes ''ii desu-ka'' () "Is it OK?". In a more informal tone sometimes the particle ''-no'' () is added instead to show a personal interest of the speaker: ''Dōshite konai-no?'' "Why aren't (you) coming?". Some simple queries are formed simply by mentioning the topic with an interrogative intonation to call for the hearer's attention: ''Kore wa?'' "(What about) this?"; ''O-namae wa?'' () "(What's your) name?". Negatives are formed by inflecting the verb. For example, ''Pan o taberu'' () "I will eat bread" or "I eat bread" becomes ''Pan o tabenai'' () "I will not eat bread" or "I do not eat bread". Plain negative forms are ''i''-adjectives (see below) and inflect as such, e.g. ''Pan o tabenakatta'' () "I did not eat bread". The so-called ''-te'' verb form is used for a variety of purposes: either progressive or perfect aspect (see above); combining verbs in a temporal sequence (''Asagohan o tabete sugu dekakeru'' "I'll eat breakfast and leave at once"), simple commands, conditional statements and permissions (''Dekakete-mo ii?'' "May I go out?"), etc. The word ''da'' (plain), ''desu'' (polite) is the Copula (linguistics)#Japanese">copula verb. It corresponds approximately to the English ''be'', but often takes on other roles, including a marker for tense, when the verb is conjugated into its past form ''datta'' (plain), ''deshita'' (polite). This comes into use because only ''i''-adjectives and verbs can carry tense in Japanese. Two additional common verbs are used to indicate existence ("there is") or, in some contexts, property: ''aru'' (negative ''nai'') and ''iru'' (negative ''inai''), for inanimate and animate things, respectively. For example, ''Neko ga iru'' "There's a cat", ''Ii kangae-ga nai'' "[I] haven't got a good idea". The verb "to do" (''suru'', polite form ''shimasu'') is often used to make verbs from nouns (''ryōri suru'' "to cook", ''benkyō suru'' "to study", etc.) and has been productive in creating modern slang words. Japanese also has a huge number of compound verbs to express concepts that are described in English using a verb and an adverbial particle (e.g. ''tobidasu'' "to fly out, to flee," from ''tobu'' "to fly, to jump" + ''dasu'' "to put out, to emit"). There are three types of adjectives (seeJapanese adjectives

This article deals with Japanese equivalents of English adjectives.

Types of adjective

In Japanese, nouns and verbs can modify nouns, with nouns taking the 〜の particles when functioning attributively (in the genitive case), and verbs in the ...

):

# ''keiyōshi'', or ''i'' adjectives, which have a conjugating ending ''i'' () (such as ''atsui'' "to be hot") which can become past ( ''atsukatta'' "it was hot"), or negative ( ''atsuku nai'' "it is not hot"). Note that ''nai'' is also an ''i'' adjective, which can become past ( ''atsuku nakatta'' "it was not hot").

#: ''atsui hi'' "a hot day".

# ''keiyōdōshi'', or ''na'' adjectives, which are followed by a form of the copula, usually ''na''. For example, ''hen'' (strange)

#: ''hen na hito'' "a strange person".

# ''rentaishi'', also called true adjectives, such as ''ano'' "that"

#: ''ano yama'' "that mountain".

Both ''keiyōshi'' and ''keiyōdōshi'' may predicate sentences. For example,

Both inflect, though they do not show the full range of conjugation found in true verbs. The ''rentaishi'' in Modern Japanese are few in number, and unlike the other words, are limited to directly modifying nouns. They never predicate sentences. Examples include ''ookina'' "big", ''kono'' "this", ''iwayuru'' "so-called" and ''taishita'' "amazing". Both ''keiyōdōshi'' and ''keiyōshi'' form adverbs, by following with ''ni'' in the case of ''keiyōdōshi'':''Gohan ga atsui.'' "The rice is hot." ''Kare wa hen da.'' "He's strange."

''hen ni naru'' "become strange",and by changing ''i'' to ''ku'' in the case of ''keiyōshi'':

''atsuku naru'' "become hot".The grammatical function of nouns is indicated by postpositions, also called particles. These include for example: * ''ga'' for the nominative case. : ''Kare ga yatta.'' "He did it." * ''ni'' for the dative case. : ''Tanaka-san ni agete kudasai'' "Please give it to Mx Tanaka." It is also used for the

lative

In grammar, the lative (; list of glossing abbreviations, abbreviated ) is a grammatical case which indicates motion to a location. It corresponds to the English prepositions "to" and "into". The lative case belongs to the group of the general loca ...

case, indicating a motion to a location.

: ''Nihon ni ikitai'' "I want to go to Japan."

*However, へ ''e'' is more commonly used for the lative case.

: ''pātī e ikanai ka?'' "Won't you go to the party?"

* ''no'' for the genitive case

In grammar, the genitive case (abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can al ...

, or nominalizing phrases.

: watashi no kamera'' "my camera"

: ''Sukī-ni iku no ga suki desu'' "(I) like going skiing."

* ''o'' for the accusative case

The accusative case (abbreviated ) of a noun is the grammatical case used to mark the direct object of a transitive verb.

In the English language, the only words that occur in the accusative case are pronouns: 'me,' 'him,' 'her,' 'us,' and ‘the ...

.

: ''Nani o tabemasu ka?'' "What will (you) eat?"

* ''wa'' for the topic. It can co-exist with the case markers listed above, and it overrides ''ga'' and (in most cases) ''o''.

: ''Watashi wa sushi ga ii desu.'' (literally) "As for me, sushi is good." The nominative marker ''ga'' after ''watashi'' is hidden under ''wa''.

Note: The subtle difference between ''wa'' and ''ga'' in Japanese cannot be derived from the English language as such, because the distinction between sentence topic and subject is not made there. While ''wa'' indicates the topic, which the rest of the sentence describes or acts upon, it carries the implication that the subject indicated by ''wa'' is not unique, or may be part of a larger group.

''Ikeda-san wa yonjū-ni sai da.'' "As for Mx Ikeda, they are forty-two years old." Others in the group may also be of that age.Absence of ''wa'' often means the subject is the focus of the sentence.

''Ikeda-san ga yonjū-ni sai da.'' "It is Mx Ikeda who is forty-two years old." This is a reply to an implicit or explicit question, such as "who in this group is forty-two years old?"

Politeness

Japanese has an extensive grammatical system to express politeness and formality. This reflects the hierarchical nature of Japanese society. The Japanese language can express differing levels in social status. The differences in social position are determined by a variety of factors including job, age, experience, or even psychological state (e.g., a person asking a favour tends to do so politely). The person in the lower position is expected to use a polite form of speech, whereas the other person might use a plainer form. Strangers will also speak to each other politely. Japanese children rarely use polite speech until they are teens, at which point they are expected to begin speaking in a more adult manner. ''See uchi-soto''. Whereas ''teineigo'' () (polite language) is commonly an inflectional system, ''sonkeigo'' () (respectful language) and ''kenjōgo'' () (humble language) often employ many special honorific and humble alternate verbs: ''iku'' "go" becomes ''ikimasu'' in polite form, but is replaced by ''irassharu'' in honorific speech and ''ukagau'' or ''mairu'' in humble speech. The difference between honorific and humble speech is particularly pronounced in the Japanese language. Humble language is used to talk about oneself or one's own group (company, family) whilst honorific language is mostly used when describing the interlocutor and their group. For example, the ''-san'' suffix ("Mr" "Mrs.", "Miss", or "Mx") is an example of honorific language. It is not used to talk about oneself or when talking about someone from one's company to an external person, since the company is the speaker's in-group. When speaking directly to one's superior in one's company or when speaking with other employees within one's company about a superior, a Japanese person will use vocabulary and inflections of the honorific register to refer to the in-group superior and their speech and actions. When speaking to a person from another company (i.e., a member of an out-group), however, a Japanese person will use the plain or the humble register to refer to the speech and actions of their own in-group superiors. In short, the register used in Japanese to refer to the person, speech, or actions of any particular individual varies depending on the relationship (either in-group or out-group) between the speaker and listener, as well as depending on the relative status of the speaker, listener, and third-person referents. Most nouns in the Japanese language may be made polite by the addition of ''o-'' or ''go-'' as a prefix. ''o-'' is generally used for words of native Japanese origin, whereas ''go-'' is affixed to words of Chinese derivation. In some cases, the prefix has become a fixed part of the word, and is included even in regular speech, such as ''gohan'' 'cooked rice; meal.' Such a construction often indicates deference to either the item's owner or to the object itself. For example, the word ''tomodachi'' 'friend,' would become ''o-tomodachi'' when referring to the friend of someone of higher status (though mothers often use this form to refer to their children's friends). On the other hand, a polite speaker may sometimes refer to ''mizu'' 'water' as ''o-mizu'' in order to show politeness. Most Japanese people employ politeness to indicate a lack of familiarity. That is, they use polite forms for new acquaintances, but if a relationship becomes more intimate, they no longer use them. This occurs regardless of age, social class, or gender.Vocabulary

There are three main sources of words in the Japanese language, the ''yamato kotoba'' () or ''wago'' (), ''kango'' (), and ''gairaigo'' (). The original language of Japan, or at least the original language of a certain population that was ancestral to a significant portion of the historical and present Japanese nation, was the so-called '' yamato kotoba'' ( or infrequently , i.e. " Yamato words"), which in scholarly contexts is sometimes referred to as ''wago'' ( or rarely , i.e. the " Wa language"). In addition to words from this original language, present-day Japanese includes a number of words that were either borrowed from Chinese or constructed from Chinese roots following Chinese patterns. These words, known as '' kango'' (), entered the language from the 5th century onwards via contact with Chinese culture. According to the Japanese dictionary, ''kango'' comprise 49.1% of the total vocabulary, ''wago'' make up 33.8%, other foreign words or '' gairaigo'' () account for 8.8%, and the remaining 8.3% constitute hybridized words or ''konshugo'' () that draw elements from more than one language. There are also a great number of words of mimetic origin in Japanese, with Japanese having a rich collection of sound symbolism, both onomatopoeia for physical sounds, and more abstract words. A small number of words have come into Japanese from theAinu language

Ainu (, ), or more precisely Hokkaido Ainu, is a language spoken by a few elderly members of the Ainu people on the northern Japanese island of Hokkaido. It is a member of the Ainu language family, itself considered a language family isolate ...

. ''Tonakai'' ( reindeer), ''rakko'' (sea otter

The sea otter (''Enhydra lutris'') is a marine mammal native to the coasts of the northern and eastern North Pacific Ocean. Adult sea otters typically weigh between , making them the heaviest members of the weasel family, but among the small ...

) and '' shishamo'' ( smelt, a type of fish) are well-known examples of words of Ainu origin.

Words of different origins occupy different registers in Japanese. Like Latin-derived words in English, ''kango'' words are typically perceived as somewhat formal or academic compared to equivalent Yamato words. Indeed, it is generally fair to say that an English word derived from Latin/French roots typically corresponds to a Sino-Japanese word in Japanese, whereas an Anglo-Saxon word would best be translated by a Yamato equivalent.

Incorporating vocabulary from European languages, ''gairaigo'', began with borrowings from Portuguese in the 16th century, followed by words from Dutch during Japan's long isolation of the Edo period. With the Meiji Restoration and the reopening of Japan in the 19th century, borrowing occurred from German, French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

, and English. Today most borrowings are from English.

In the Meiji era, the Japanese also coined many neologisms using Chinese roots and morphology to translate European concepts; these are known as wasei kango (Japanese-made Chinese words). Many of these were then imported into Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese via their kanji in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. For example, , and are words derived from Chinese roots that were first created and used by the Japanese, and only later borrowed into Chinese and other East Asian languages. As a result, Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese share a large common corpus of vocabulary in the same way many Greek- and Latin-derived words – both inherited or borrowed into European languages, or modern coinages from Greek or Latin roots – are shared among modern European languages – see classical compound.

In the past few decades, '' wasei-eigo'' ("made-in-Japan English") has become a prominent phenomenon. Words such as ''wanpatān'' (< ''one'' + ''pattern'', "to be in a rut", "to have a one-track mind") and ''sukinshippu'' (< ''skin'' + ''-ship'', "physical contact"), although coined by compounding English roots, are nonsensical in most non-Japanese contexts; exceptions exist in nearby languages such as Korean however, which often use words such as ''skinship'' and ''rimokon'' (remote control) in the same way as in Japanese.

The popularity of many Japanese cultural exports has made some native Japanese words familiar in English, including ''emoji

An emoji ( ; plural emoji or emojis) is a pictogram, logogram, ideogram or smiley embedded in text and used in electronic messages and web pages. The primary function of emoji is to fill in emotional cues otherwise missing from typed conversat ...

'', '' futon, haiku, judo, kamikaze, karaoke, karate

(; ; Okinawan language, Okinawan pronunciation: ) is a martial arts, martial art developed in the Ryukyu Kingdom. It developed from the Okinawan martial arts, indigenous Ryukyuan martial arts (called , "hand"; ''tii'' in Okinawan) under the ...

, ninja, origami, rickshaw'' (from ''jinrikisha''), '' samurai, sayonara, Sudoku, sumo

is a form of competitive full-contact wrestling where a ''rikishi'' (wrestler) attempts to force his opponent out of a circular ring (''dohyō'') or into touching the ground with any body part other than the soles of his feet (usually by thr ...

, sushi, tofu, tsunami, tycoon''. See list of English words of Japanese origin for more.

Writing system

History

Literacy was introduced to Japan in the form of the Chinese writing system, by way of Baekje before the 5th century. Using this language, the Japanese king Bu presented a petition to Emperor Shun of Liu Song in AD 478. After the ruin of Baekje, Japan invited scholars from China to learn more of the Chinese writing system. Japanese emperors gave an official rank to Chinese scholars (/) and spread the use of Chinese characters from the 7th century to the 8th century.Kojiki

The , also sometimes read as or , is an early Japanese chronicle of myths, legends, hymns, genealogies, oral traditions, and semi-historical accounts down to 641 concerning the origin of the Japanese archipelago, the , and the Japanese imperia ...

, which was written in AD 712. Japanese writers then started to use Chinese characters to write Japanese in a style known as ''man'yōgana'', a syllabic script which used Chinese characters for their sounds in order to transcribe the words of Japanese speech syllable by syllable.

Over time, a writing system evolved. Chinese characters ( kanji) were used to write either words borrowed from Chinese, or Japanese words with the same or similar meanings. Chinese characters were also used to write grammatical elements, were simplified, and eventually became two syllabic scripts: hiragana and katakana which were developed based on Manyogana. Some scholars claim that Manyogana originated from Baekje, but this hypothesis is denied by mainstream Japanese scholars.

Hiragana and katakana were first simplified from kanji, and hiragana, emerging somewhere around the 9th century, was mainly used by women. Hiragana was seen as an informal language, whereas katakana and kanji were considered more formal and was typically used by men and in official settings. However, because of hiragana's accessibility, more and more people began using it. Eventually, by the 10th century, hiragana was used by everyone.

Modern Japanese is written in a mixture of three main systems: kanji, characters of Chinese origin used to represent both Chinese loanwords into Japanese and a number of native Japanese morphemes; and two syllabaries

In the linguistic study of written languages, a syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent the syllables or (more frequently) moras which make up words.

A symbol in a syllabary, called a syllabogram, typically represents an (option ...

: hiragana and katakana. The Latin script (or romaji in Japanese) is used to a certain extent, such as for imported acronyms and to transcribe Japanese names and in other instances where non-Japanese speakers need to know how to pronounce a word (such as "ramen" at a restaurant). Arabic numerals are much more common than the kanji when used in counting, but kanji numerals are still used in compounds, such as ''tōitsu'' ("unification").

Historically, attempts to limit the number of kanji in use commenced in the mid-19th century, but did not become a matter of government intervention until after Japan's defeat in the Second World War. During the period of post-war occupation (and influenced by the views of some U.S. officials), various schemes including the complete abolition of kanji and exclusive use of rōmaji were considered. The ''jōyō kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters and their readings, announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current ''jōyō kanji'' are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010. It is a slightly modified version of the ''tō ...

'' ("common use kanji", originally called '' tōyō kanji'' anji for general use scheme arose as a compromise solution.

Japanese students begin to learn kanji from their first year at elementary school. A guideline created by the Japanese Ministry of Education, the list of '' kyōiku kanji'' ("education kanji", a subset of ''jōyō kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters and their readings, announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current ''jōyō kanji'' are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010. It is a slightly modified version of the ''tō ...

''), specifies the 1,006 simple characters a child is to learn by the end of sixth grade. Children continue to study another 1,130 characters in junior high school, covering in total 2,136 ''jōyō kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters and their readings, announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current ''jōyō kanji'' are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010. It is a slightly modified version of the ''tō ...

''. The official list of ''jōyō kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters and their readings, announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current ''jōyō kanji'' are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010. It is a slightly modified version of the ''tō ...

'' was revised several times, but the total number of officially sanctioned characters remained largely unchanged.

As for kanji for personal names, the circumstances are somewhat complicated. ''Jōyō kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters and their readings, announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current ''jōyō kanji'' are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010. It is a slightly modified version of the ''tō ...

'' and '' jinmeiyō kanji'' (an appendix of additional characters for names) are approved for registering personal names. Names containing unapproved characters are denied registration. However, as with the list of ''jōyō kanji

The is the guide to kanji characters and their readings, announced officially by the Japanese Ministry of Education. Current ''jōyō kanji'' are those on a list of 2,136 characters issued in 2010. It is a slightly modified version of the ''tō ...

'', criteria for inclusion were often arbitrary and led to many common and popular characters being disapproved for use. Under popular pressure and following a court decision holding the exclusion of common characters unlawful, the list of '' jinmeiyō kanji'' was substantially extended from 92 in 1951 (the year it was first decreed) to 983 in 2004. Furthermore, families whose names are not on these lists were permitted to continue using the older forms.

Hiragana

'' Hiragana'' are used for words without kanji representation, for words no longer written in kanji, for replacement of rare kanji that may be unfamiliar to intended readers, and also following kanji to show conjugational endings. Because of the way verbs (and adjectives) in Japanese are conjugated, kanji alone cannot fully convey Japanese tense and mood, as kanji cannot be subject to variation when written without losing their meaning. For this reason, hiragana are appended to kanji to show verb and adjective conjugations. Hiragana used in this way are called okurigana. Hiragana can also be written in a superscript called furigana above or beside a kanji to show the proper reading. This is done to facilitate learning, as well as to clarify particularly old or obscure (or sometimes invented) readings.Katakana

'' Katakana'', like hiragana, constitute asyllabary

In the linguistic study of written languages, a syllabary is a set of written symbols that represent the syllables or (more frequently) moras which make up words.

A symbol in a syllabary, called a syllabogram, typically represents an (optiona ...

; katakana are primarily used to write foreign words, plant and animal names, and for emphasis. For example, "Australia" has been adapted as ''Ōsutoraria'' (), and "supermarket" has been adapted and shortened into ''sūpā'' ().

Gender in the Japanese language

Depending on the speakers’ gender, different linguistic features might be used. The typical lect used by females is called and the one used by males is called . ''Josiego'' and ''danseigo'' are different in various ways, including first-person pronouns (such as ''watashi'' or ''atashi'' for women and for men) and sentence-final particles (such as , , or for ''joseigo'', or , , or for ''danseigo''). In addition to these specific differences, expressions and pitch can also be different. For example, ''joseigo'' is more gentle, polite, refined, indirect, modest, and exclamatory, and often accompanied by raised pitch.Kogal Slang

In the 1990s, the traditional feminine speech patterns and stereotyped behaviors were challenged, and a popular culture of “naughty” teenage girls emerged, called , sometimes referenced in English-language materials as “kogal”. Their mischievous behaviors, deviant language usage, the particular make-up called , and the fashion became objects of focus in the mainstream media. Although kogal slang was not appreciated by older generations, these girls kept creating novel terms and expressions. Kogal culture changed Japanese norms of gender and the Japanese language as well.Non-native study

Many major universities throughout the world provide Japanese language courses, and a number of secondary and even primary schools worldwide offer courses in the language. This is a significant increase from before World War II; in 1940, only 65 Americans not of Japanese descent were able to read, write and understand the language. Beate Sirota Gordon commencement address at Mills College, 14 May 2011"Sotomayor, Denzel Washington, GE CEO Speak to Graduates,"

C-SPAN (US). 30 May 2011; retrieved 2011-05-30 International interest in the Japanese language dates from the 19th century but has become more prevalent following Japan's economic bubble of the 1980s and the global popularity of Japanese popular culture (such as anime and video games) since the 1990s. As of 2015, more than 3.6 million people studied the language worldwide, primarily in East and Southeast Asia. Nearly one million Chinese, 745,000 Indonesians, 556,000 South Koreans and 357,000 Australians studied Japanese in lower and higher educational institutions. Between 2012 and 2015, considerable growth of learners originated in

Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

(20.5%), Thailand (34.1%), Vietnam (38.7%) and the Philippines (54.4%).

The Japanese government provides standardized tests to measure spoken and written comprehension of Japanese for second language learners; the most prominent is the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT), which features five levels of exams. The JLPT is offered twice a year.

Example text

Article 1 of the '' Universal Declaration of Human Rights'' in Japanese:See also

* Aizuchi * Culture of Japan * Japanese dictionaries * Japanese exonyms * Japanese language and computers *Japanese literature

Japanese literature throughout most of its history has been influenced by cultural contact with neighboring Asian literatures, most notably China and its literature. Early texts were often written in pure Classical Chinese or , a Chinese-Japanes ...

* Japanese name

in modern times consist of a family name (surname) followed by a given name, in that order. Nevertheless, when a Japanese name is written in the Roman alphabet, ever since the Meiji era, the official policy has been to cater to Western expecta ...

* Japanese punctuation

* Japanese profanity

Profanity in the Japanese language can pertain to scatological references or aim to put down the listener by negatively commenting on their ability, intellect, or appearance. Furthermore, there are different levels of Japanese speech that indicate ...

* Japanese Sign Language family

* Japanese words and words derived from Japanese in other languages at Wiktionary, Wikipedia's sibling project

* Classical Japanese language

* Romanization of Japanese

The romanization of Japanese is the use of Latin script to write the Japanese language. This method of writing is sometimes referred to in Japanese as .

Japanese is normally written in a combination of logographic characters borrowed from Ch ...

** Hepburn romanization

* '' Shogakukan Progressive Japanese–English Dictionary'' (book)

* Rendaku

* Yojijukugo

*Other:

** History of Writing in Vietnam

Notes

References

Citations

Works cited

* Bloch, Bernard (1946). Studies in colloquial Japanese I: Inflection. ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'', ''66'', pp. 97–130. * Bloch, Bernard (1946). Studies in colloquial Japanese II: Syntax. ''Language'', ''22'', pp. 200–248. * Chafe, William L. (1976). Giveness, contrastiveness, definiteness, subjects, topics, and point of view. In C. Li (Ed.), ''Subject and topic'' (pp. 25–56). New York: Academic Press. . * Dalby, Andrew. (2004)"Japanese,"

in ''Dictionary of Languages: the Definitive Reference to More than 400 Languages.'' New York: Columbia University Press. ; * * * * Kuno, Susumu (1973). ''The structure of the Japanese language''. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. . * Kuno, Susumu. (1976). "Subject, theme, and the speaker's empathy: A re-examination of relativization phenomena," in Charles N. Li (Ed.), ''Subject and topic'' (pp. 417–444). New York: Academic Press. . * McClain, Yoko Matsuoka. (1981). ''Handbook of modern Japanese grammar:'' 'Kōgo Nihon bumpō'' Tokyo: Hokuseido Press. . * Miller, Roy (1967). ''The Japanese language''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. * Miller, Roy (1980). ''Origins of the Japanese language: Lectures in Japan during the academic year, 1977–78''. Seattle: University of Washington Press. . * Mizutani, Osamu; & Mizutani, Nobuko (1987). ''How to be polite in Japanese:'' 'Nihongo no keigo'' Tokyo: The Japan Times. . * * * * Shibamoto, Janet S. (1985). ''Japanese women's language''. New York: Academic Press. . Graduate Level * (pbk). * Tsujimura, Natsuko (1996). ''An introduction to Japanese linguistics''. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. (hbk); (pbk). Upper Level Textbooks * Tsujimura, Natsuko (Ed.) (1999). ''The handbook of Japanese linguistics''. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers. . Readings/Anthologies *

Further reading

* * * * * *External links

National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics

Japanese Language Student's Handbook

* {{Authority control Agglutinative languages Languages attested from the 8th century Languages of Japan Languages of Palau Subject–object–verb languages