J. P. Morgan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated

In his ascent to power, Morgan focused on railroads, America's largest business enterprises. He wrested control of the

In his ascent to power, Morgan focused on railroads, America's largest business enterprises. He wrested control of the

the original

on July 10, 2010.

After his father's death in 1890, Morgan took control of J. S. Morgan & Co. (renamed Morgan, Grenfell & Company in 1910). He began talks with Charles M. Schwab, president of Carnegie Co., and businessman

After his father's death in 1890, Morgan took control of J. S. Morgan & Co. (renamed Morgan, Grenfell & Company in 1910). He began talks with Charles M. Schwab, president of Carnegie Co., and businessman

The

The

While conservatives in the

While conservatives in the

corporate finance

Corporate finance is the area of finance that deals with the sources of funding, the capital structure of corporations, the actions that managers take to increase the Value investing, value of the firm to the shareholders, and the tools and anal ...

on Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for t ...

throughout the Gilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Weste ...

. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known as J.P. Morgan and Co., he was the driving force behind the wave of industrial consolidation in the United States spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Over the course of his career on Wall Street, J.P. Morgan spearheaded the formation of several prominent multinational corporations

A multinational company (MNC), also referred to as a multinational enterprise (MNE), a transnational enterprise (TNE), a transnational corporation (TNC), an international corporation or a stateless corporation with subtle but contrasting senses, i ...

including U.S. Steel

United States Steel Corporation, more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an American integrated steel producer headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with production operations primarily in the United States of America and in severa ...

, International Harvester

The International Harvester Company (often abbreviated by IHC, IH, or simply International ( colloq.)) was an American manufacturer of agricultural and construction equipment, automobiles, commercial trucks, lawn and garden products, household e ...

and General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

which subsequently fell under his supervision. He and his partners also held controlling interests in numerous other American businesses including Aetna

Aetna Inc. () is an American managed health care company that sells traditional and consumer directed health care insurance and related services, such as medical, pharmaceutical, dental, behavioral health, long-term care, and disability plans, ...

, Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

, Pullman Car Company

The Pullman Company, founded by George Pullman, was a manufacturer of railroad cars in the mid-to-late 19th century through the first half of the 20th century, during the boom of railroads in the United States. Through rapid late-19th century ...

and 21 railroads. Due to the extent of his dominance over U.S. finance, Morgan exercised enormous influence over the nation's policies and the market forces underlying its economy. During the Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic or Knickerbocker Crisis, was a financial crisis that took place in the United States over a three-week period starting in mid-October, when the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from ...

, he organized a coalition of financiers that saved the American monetary system

A monetary system is a system by which a government provides money in a country's economy. Modern monetary systems usually consist of the national treasury, the mint, the central banks and commercial banks.

Commodity money system

A commodity m ...

from collapse.

As the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

's leading financier, J.P. Morgan's dedication to efficiency and modernization helped transform the shape of the American economy. Adrian Wooldridge

Adrian Wooldridge (born 1959) is an author and columnist. He is the Global Business Columnist at Bloomberg Opinion.

Life and career

Wooldridge was educated at Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied modern history and was awarded a fellowshi ...

characterized Morgan as America's "greatest banker". Morgan died in Rome, Italy, in his sleep in 1913 at the age of 75, leaving his fortune and business to his son, John Pierpont Morgan Jr. Biographer Ron Chernow

Ronald Chernow (; born March 3, 1949) is an American writer, journalist and biographer. He has written bestselling historical non-fiction biographies.

He won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for Biography and the 2011 American History Book Prize for his ...

estimated his fortune at $80million (equivalent to $billion in ).

Childhood and education

Morgan was born and raised inHartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

, to Junius Spencer Morgan

Junius Spencer Morgan I (April 14, 1813 – April 8, 1890) was an American banker and financier, as well as the father of John Pierpont "J.P." Morgan and patriarch to the Morgan banking house.

In 1864, he established J. S. Morgan & Co. in L ...

(1813–1890) and Juliet Pierpont (1816–1884) of the influential Morgan family

The Morgan family is an American family and banking dynasty, which became prominent in the U.S. and throughout the world in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Members of the family amassed an immense fortune over the generations, primar ...

. Pierpont, as he preferred to be known, had a varied education due in part to his father's plans. In the fall of 1848, he transferred to the Hartford Public School, then to the Episcopal Academy in Cheshire, Connecticut

Cheshire ( ), formerly known as New Cheshire Parish, is a town in New Haven County, Connecticut, United States. At the time of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population of Cheshire was 28,733. The center of population of Connecti ...

(now Cheshire Academy

Cheshire Academy is a selective, co-educational college preparatory school located in Cheshire, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1794 as the Episcopal Academy of Connecticut, it is currently the eleventh oldest boarding school in the United ...

), where he boarded with the principal. In September 1851, he passed the entrance exam for The English High School

The English High School of Boston, Massachusetts, United States, is one of the first public high schools in America, founded in 1821. Originally called The English Classical School, it was renamed The English High School upon its first relocation ...

of Boston, which specialized in mathematics for careers in commerce. In April 1852, an illness struck Morgan which became more common as his life progressed: Rheumatic fever

Rheumatic fever (RF) is an inflammatory disease that can involve the heart, joints, skin, and brain. The disease typically develops two to four weeks after a streptococcal throat infection. Signs and symptoms include fever, multiple painful jo ...

left him in such pain that he could not walk, and Junius sent him to the Azores

)

, motto =( en, "Rather die free than subjected in peace")

, anthem= ( en, "Anthem of the Azores")

, image_map=Locator_map_of_Azores_in_EU.svg

, map_alt=Location of the Azores within the European Union

, map_caption=Location of the Azores wi ...

to recover.

He convalesced there for almost a year, then returned to Boston to resume his studies. After graduation, his father sent him to Bellerive, a school in the Swiss village of La Tour-de-Peilz

La Tour-de-Peilz () is a municipality in Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut District in the canton of Vaud in Switzerland. The city is located on Lake Geneva between Montreux and Vevey (their agglomeration counting some 80,000 inhabitants).

History

In the ...

, where he gained fluency in French. His father then sent him to the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

to improve his German. He attained passable fluency within six months, and a degree in art history; then traveled back to London via Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden () is a city in central western Germany and the capital of the state of Hesse. , it had 290,955 inhabitants, plus approximately 21,000 United States citizens (mostly associated with the United States Army). The Wiesbaden urban area ...

, his formal education complete.

Career

Early years and life

Morgan went into banking in 1857 at the London branch ofmerchant banking

A merchant bank is historically a bank dealing in commercial loans and investment. In modern British usage it is the same as an investment bank. Merchant banks were the first modern banks and evolved from medieval merchants who traded in commodi ...

firm Peabody, Morgan & Co., a partnership between his father and George Peabody

George Peabody ( ; February 18, 1795 – November 4, 1869) was an American financier and philanthropist. He is widely regarded as the father of modern philanthropy.

Born into a poor family in Massachusetts, Peabody went into business in dry go ...

founded three years earlier. In 1858, he moved to New York City to join the banking house of Duncan, Sherman & Company

Duncan, Sherman & Company was a New York City banking firm, founded in 1852, that went bankrupt in 1875.

History

Duncan, Sherman & Company was established in 1852 by Scottish immigrant Alexander Duncan, Watts Sherman (the former cashier and gene ...

, the American representatives of George Peabody and Company. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, in an incident known as the Hall Carbine Affair

During the American Civil War, John Pierpont Morgan financed the purchase of 5,000 surplus rifles at $3.50 each, which were then sold back to the government for $22 each. The incident became renowned as a scandalous example of wartime profiteering ...

, Morgan financed the purchase of five thousand rifles from an army arsenal at $3.50 each, which were then resold to a field general for $22 each. Morgan had avoided serving during the war by paying a substitute $300 to take his place. From 1860 to 1864, as J. Pierpont Morgan & Company, he acted as agent in New York for his father's firm, renamed "J.S. Morgan & Co." upon Peabody's retirement in 1864. From 1864 to 1872, he was a member of the firm of Dabney, Morgan, and Company. In 1871, Anthony J. Drexel

Anthony Joseph Drexel Sr. (September 13, 1826 – June 30, 1893) was an American banker who played a major role in the rise of modern global finance after the American Civil War. As the dominant partner of Drexel & Co. of Philadelphia, he founde ...

founded the New York firm of Drexel, Morgan & Company with his apprentice Pierpont.

J.P. Morgan & Company

After the death ofAnthony Drexel

Anthony Joseph Drexel Sr. (September 13, 1826 – June 30, 1893) was an American banker who played a major role in the rise of modern global finance after the American Civil War. As the dominant partner of Drexel & Co. of Philadelphia, he founde ...

, the firm was rechristened J. P. Morgan & Company in 1895, retaining close ties with Drexel & Company

Drexel Burnham Lambert was an American multinational investment bank that was forced into bankruptcy in 1990 due to its involvement in illegal activities in the junk bond market, driven by senior executive Michael Milken. At its height, it was a ...

of Philadelphia; Morgan, Harjes & Company of Paris; and J.S. Morgan & Company (after 1910 Morgan, Grenfell & Company) of London. By 1900 it was one of the world's most powerful banking houses, focused primarily on reorganizations and consolidations.

Morgan had many partners over the years, such as George W. Perkins, but always remained firmly in charge. He often took over troubled business and reorganized their structures and management to return them to profitability, a process that became known as "Morganization". His reputation as a banker and financier drew interest from investors to the businesses that he took over.

Railroads

Albany and Susquehanna Railroad

The Albany and Susquehanna Railroad (A&S) was a broad gauge railroad from Albany to Binghamton, New York, operating 1851 to 1870. It was subsequently leased by the Delaware and Hudson Canal Company and later merged into the Delaware and Hudson ...

from Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made hi ...

and Jim Fisk in 1869; led the syndicate that broke the government-financing privileges of Jay Cooke

Jay Cooke (August 10, 1821 – February 16, 1905) was an American financier who helped finance the Union war effort during the American Civil War and the postwar development of railroads in the northwestern United States. He is generally acknowle ...

; and developed and financed a railroad empire by reorganization and consolidation in all parts of the United States. He raised large sums in Europe; but rather than participating solely as a financier, he helped the railroads reorganize and achieve greater efficiency. He fought speculators interested only in profit and built a vision of an integrated transportation system. He successfully marketed a large part of William H. Vanderbilt

William Henry Vanderbilt (May 8, 1821 – December 8, 1885) was an American businessman and philanthropist. He was the eldest son of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, an heir to his fortune and a prominent member of the Vanderbilt family. Vanderbi ...

's New York Central

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Midw ...

holdings in 1883. In 1885 he reorganized the New York, West Shore & Buffalo Railroad, leasing it to the New York Central. In 1886 he reorganized the Philadelphia & Reading, and in 1888 the Chesapeake & Ohio. After Congress passed the Interstate Commerce Act

The Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 is a United States federal law that was designed to regulate the railroad industry, particularly its monopolistic practices. The Act required that railroad rates be "reasonable and just," but did not empower ...

in 1887, Morgan set up conferences in 1889 and 1890 that brought together railroad presidents to help the industry follow the new laws and write agreements for the maintenance of "public, reasonable, uniform and stable rates". The first of their kind, the conferences created a community of interest among competing lines, paving the way for the great consolidations of the early 20th century. In addition, J P Morgan & Co, and the banking houses which it succeeded, reorganized a large number of railroads between 1869 and 1899. Morgan also financed street railways, especially in New York City.

A major political debacle came in 1904. The Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, whic ...

went bankrupt in the great depression of 1893. The bankruptcy wiped out the railroad's bondholders, leaving it free of debt, and a complex financial battle for its control ensued. In 1901, a compromise was reached between Morgan, New York financier E. H. Harriman

Edward Henry Harriman (February 20, 1848 – September 9, 1909) was an American financier and railroad executive.

Early life

Harriman was born on February 20, 1848, in Hempstead, New York, the son of Orlando Harriman Sr., an Episcopal clergyman ...

and St. Paul, MN railroad builder James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railroad director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwes ...

. To reduce expensive competition in the Midwest, they created the Northern Securities Company

The Northern Securities Company was a short-lived American railroad trust formed in 1901 by E. H. Harriman, James J. Hill, J.P. Morgan and their associates. The company controlled the Northern Pacific Railway; Great Northern Railway; Chicago, ...

to consolidate the operations of three of the region's most important railways: the Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, whic ...

, the Great Northern Railway, and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad

The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad was a railroad that operated in the Midwestern United States. Commonly referred to as the Burlington Route, the Burlington, or as the Q, it operated extensive trackage in the states of Colorado, Illin ...

. The consolidators ran into unexpected opposition, however, from President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

. An energetic trustbuster, Roosevelt considered the giant merger bad for consumers and a violation of the (until then) seldom-enforced Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 (, ) is a United States antitrust law which prescribes the rule of free competition among those engaged in commerce. It was passed by Congress and is named for Senator John Sherman, its principal author.

T ...

. In 1902, Roosevelt ordered his Justice Department to sue to break it up. In 1904 the Supreme Court dissolved the Northern Security company and the railroads had to go their separate, competitive ways. Morgan did not lose money on the project, but his all-powerful political reputation suffered.

Treasury gold

The Federal Treasury was nearly out of gold in 1895, at the depths of thePanic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

. Morgan had put forward a plan for the federal government to buy gold from his and European banks but it was declined in favor of a plan to sell bonds directly to the general public to overcome the crisis. Morgan, sure there was not enough time to implement such a plan, demanded and eventually obtained a meeting with Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

where he claimed the government could default that day if they didn't do something. Morgan came up with a plan to use an old civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

statute that allowed Morgan and the Rothschilds

The Rothschild family ( , ) is a wealthy Ashkenazi Jewish family originally from Frankfurt that rose to prominence with Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744–1812), a court factor to the German Landgraves of Hesse-Kassel in the Free City of F ...

to sell gold directly to the U.S. Treasury, 3.5 million ounces, to restore the treasury surplus, in exchange for a 30-year bond issue. The episode saved the Treasury but hurt Cleveland's standing with the agrarian wing of the Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

, and became an issue in the election of 1896

The following elections occurred in 1896:

{{TOC right

North America

Canada

* 1896 Canadian federal election

* December 1896 Edmonton municipal election

* January 1896 Edmonton municipal election

* 1896 Manitoba general election

United States

* ...

when banks came under a withering attack from William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

. Morgan and Wall Street bankers donated heavily to Republican William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

, who was elected in 1896 and re-elected in 1900. Gordon, John Steele (Winter 2010). , American Heritage.com; retrieved December 22, 2011; archived frothe original

on July 10, 2010.

Steel

After his father's death in 1890, Morgan took control of J. S. Morgan & Co. (renamed Morgan, Grenfell & Company in 1910). He began talks with Charles M. Schwab, president of Carnegie Co., and businessman

After his father's death in 1890, Morgan took control of J. S. Morgan & Co. (renamed Morgan, Grenfell & Company in 1910). He began talks with Charles M. Schwab, president of Carnegie Co., and businessman Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

in 1900, with the goal of buying Carnegie's steel business and merging it with several other steel, coal, mining and shipping firms. After financing the creation of the Federal Steel Company, he merged it in 1901 with the Carnegie Steel Company

Carnegie Steel Company was a steel-producing company primarily created by Andrew Carnegie and several close associates to manage businesses at steel mills in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area in the late 19th century. The company was forme ...

and several other steel and iron businesses (including William Edenbirn's Consolidated Steel and Wire Company), forming the United States Steel Corporation. In 1901, U.S. Steel was the world's first billion-dollar company, with an authorized capitalization of $1.4 billion, much larger than any other industrial firm and comparable in size to the largest railroads.

U.S. Steel's goals were to achieve greater economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of output produced per unit of time. A decrease in cost per unit of output enables ...

, reduce transportation and resource costs, expand product lines, and improve distribution to allow the United States to compete globally with the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. Schwab and others claimed the company's size would enable it to be more aggressive and effective in pursuing distant international markets ("globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

"). U.S. Steel was regarded as a monopoly by critics, as it sought to dominate not only steel but the construction of bridges, ships, railroad cars and rails, wire, nails, and many other products. With U.S. Steel, Morgan captured two-thirds of the steel market, and Schwab was confident that the company would soon hold a 75% market share. However, after 1901, its market share dropped; and in 1903, Schwab resigned to form Bethlehem Steel

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was an American steelmaking company headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. For most of the 20th century, it was one of the world's largest steel producing and shipbuilding companies. At the height of its succe ...

, which became the second largest U.S. steel producer.

Labor policy was a contentious issue. U.S. Steel was non-union, and experienced steel producers, led by Schwab, used aggressive tactics to identify and root out pro-union "troublemakers". The lawyers and bankers who had organized the merger—including Morgan and CEO Elbert Gary

Elbert Henry Gary (October 8, 1846August 15, 1927) was an American lawyer, county judge and business executive. He was a founder of U.S. Steel in 1901, bringing together partners J. P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie, and Charles M. Schwab. The city o ...

—were more concerned with long-range profits, stability, good public relations, and avoiding trouble. The bankers' views generally prevailed, and the result was a "paternalistic" labor policy. (U.S. Steel was eventually unionized in the late 1930s.)

Panic of 1907

The

The Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic or Knickerbocker Crisis, was a financial crisis that took place in the United States over a three-week period starting in mid-October, when the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from ...

was a financial crisis that almost crippled the American economy. Major New York banks were on the verge of bankruptcy and there was no mechanism to rescue them, until Morgan stepped in to help resolve the crisis.Carosso, ''The Morgans'' pp. 528–48 Treasury Secretary George B. Cortelyou earmarked $35 million of federal money to deposit in New York banks. Morgan then met with the nation's leading financiers in his New York mansion, where he forced them to devise a plan to meet the crisis. James Stillman

James Jewett Stillman (June 9, 1850 – March 15, 1918) was an American businessman who invested in land, banking, and railroads in New York, Texas, and Mexico. He was chairman of the board of directors of the National City Bank. He forged alli ...

, president of the National City Bank, also played a central role. Morgan organized a team of bank and trust executives which redirected money between banks, secured further international lines of credit, and bought up the plummeting stocks of healthy corporations.

A delicate political issue arose regarding the brokerage firm of Moore and Schley, which was deeply involved in a speculative pool in the stock of the Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company

The Tennessee Coal, Iron and Railroad Company (1852–1952), also known as TCI and the Tennessee Company, was a major American steel manufacturer with interests in coal mining, coal and iron ore mining and railroad operations. Originally based en ...

. Moore and Schley had pledged over $6 million of the Tennessee Coal and Iron (TCI) stock for loans among the Wall Street banks. The banks had called the loans, and the firm could not pay. If Moore and Schley should fail, a hundred more failures would follow and then all Wall Street might go to pieces. Morgan decided they had to save Moore and Schley. TCI was one of the chief competitors of U.S. Steel, owning valuable iron and coal deposits. Morgan controlled U.S. Steel; he decided it had to buy the TCI stock from Moore and Schley. Elbert Gary, head of U.S. Steel, agreed, but was concerned there would be antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

implications that could cause grave trouble for U.S. Steel, which was already dominant in the steel industry. Morgan sent Gary to see President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, who promised legal immunity for the deal. U.S. Steel thereupon paid $30 million for the TCI stock and Moore and Schley was saved. The announcement had an immediate effect; by November 7, 1907, the panic was over. The crisis underscored the need for a powerful oversight mechanism.

Vowing never to let it happen again, and realizing that in a future crisis there was unlikely to be another Morgan, in 1913 banking and political leaders, led by Senator Nelson Aldrich

Nelson Wilmarth Aldrich (/ ˈɑldɹɪt͡ʃ/; November 6, 1841 – April 16, 1915) was a prominent American politician and a leader of the Republican Party in the United States Senate, where he represented Rhode Island from 1881 to 1911. By the ...

, devised a plan that resulted in the creation of the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States of America. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a ...

in 1913.

Banking's critics

While conservatives in the

While conservatives in the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

hailed Morgan for his civic responsibility, his strengthening of the national economy, and his devotion to the arts and religion, the left wing viewed him as one of the central figures in the system it rejected. Morgan redefined conservatism in terms of financial prowess coupled with strong commitments to religion and high culture.

Enemies of banking attacked Morgan for the terms of his loan of gold to the federal government

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government (federalism). In a federation, the self-governin ...

in the 1895 crisis and, together with writer Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

, they attacked him for the financial resolution of the Panic of 1907

The Panic of 1907, also known as the 1907 Bankers' Panic or Knickerbocker Crisis, was a financial crisis that took place in the United States over a three-week period starting in mid-October, when the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from ...

. They also attempted to attribute to him the financial ills of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad

The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad , commonly known as The Consolidated, or simply as the New Haven, was a railroad that operated in the New England region of the United States from 1872 to December 31, 1968. Founded by the merger of ...

. In December 1912, Morgan testified before the Pujo Committee

The Pujo Committee was a United States congressional subcommittee in 1912–1913 that was formed to investigate the so-called "money trust", a community of Wall Street bankers and financiers that exerted powerful control over the nation's finance ...

, a subcommittee of the House Banking and Currency committee. The committee ultimately concluded that a small number of financial leaders was exercising considerable control over many industries. The partners of J.P. Morgan & Co. and directors of First National and National City Bank controlled aggregate resources of $22.245 billion, which Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer and associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.

Starting in 1890, he helped develop the "right to privacy" concept ...

, later a U.S. Supreme Court Justice

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

, compared to the value of all the property in the twenty-two states west of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

.

Unsuccessful ventures

Morgan did not always invest well, as several failures demonstrated.Nikola Tesla

In 1900, the inventorNikola Tesla

Nikola Tesla ( ; ,"Tesla"

''

''

Wardenclyffe) that would outperform the short range radio wave-based wireless telegraph system then being demonstrated by

*

*

Morgan was a member of the Union Club in New York City. When a friend,

Morgan was a member of the Union Club in New York City. When a friend,

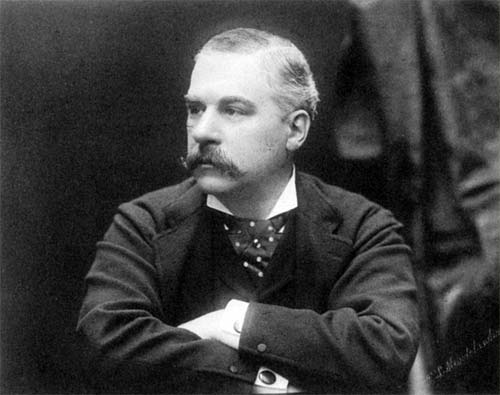

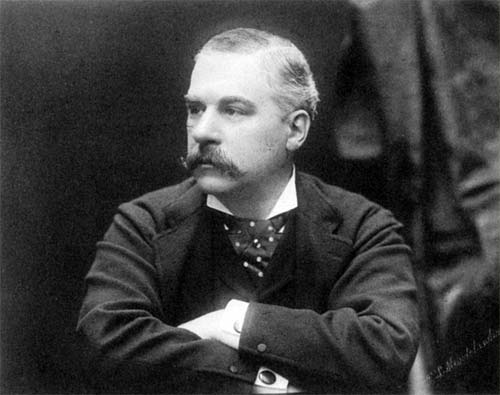

Morgan often had a tremendous physical effect on people; one man said that a visit from Morgan left him feeling "as if a gale had blown through the house." He was physically large with massive shoulders, piercing eyes, and a purple nose. He was known to dislike publicity and hated being photographed without his permission; as a result of his self-consciousness of his rosacea, all of his professional portraits were retouched. His deformed nose was due to a disease called

Morgan often had a tremendous physical effect on people; one man said that a visit from Morgan left him feeling "as if a gale had blown through the house." He was physically large with massive shoulders, piercing eyes, and a purple nose. He was known to dislike publicity and hated being photographed without his permission; as a result of his self-consciousness of his rosacea, all of his professional portraits were retouched. His deformed nose was due to a disease called

His house at 219 Madison Avenue was originally built in 1853 by John Jay Phelps and purchased by Morgan in 1882. It became the first electrically lit private residence in New York. His interest in the new technology was a result of his financing

His house at 219 Madison Avenue was originally built in 1853 by John Jay Phelps and purchased by Morgan in 1882. It became the first electrically lit private residence in New York. His interest in the new technology was a result of his financing

An avid yachtsman, Morgan owned several large yachts, the first being the ''Corsair'', built by

An avid yachtsman, Morgan owned several large yachts, the first being the ''Corsair'', built by

By the turn of the century, Morgan had become one of America's most important collectors of gems and had assembled the most important gem collection in the U.S. as well as of American gemstones (over 1,000 pieces). Tiffany & Co. assembled his first collection under their Chief Gemologist,

By the turn of the century, Morgan had become one of America's most important collectors of gems and had assembled the most important gem collection in the U.S. as well as of American gemstones (over 1,000 pieces). Tiffany & Co. assembled his first collection under their Chief Gemologist,

His estate was worth $68.3 million ($1.39 billion in today's dollars based on

His estate was worth $68.3 million ($1.39 billion in today's dollars based on

The gemstone

The gemstone

excerpt and text search

* Wheeler, George, ''Pierpont Morgan and Friends: the Anatomy of a Myth'', Englewood Cliffs, N.J., Prentice-Hall, 1973. Specialized studies * Brandeis, Louis D. ''

''Wall Street: A History from Its Beginnings to the Fall of Enron''

Oxford University Press. 2004. * Giedeman, Daniel C. "J. P. Morgan, the Clayton Antitrust Act, and Industrial Finance-Constraints in the Early Twentieth Century", ''Essays in Economic and Business History'', 2004 22: 111–126 * Hannah, Leslie. "J. P. Morgan in London and New York before 1914," ''Business History Review'' 85 (Spring 2011) 113–50 * * Moody, John

''The Masters of Capital: A Chronicle of Wall Street''

(1921) * Rottenberg, Dan. ''The Man Who Made Wall Street''. University of Pennsylvania Press.

The Morgan Library and Museum

225 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, J. P. 1837 births 1913 deaths 19th-century American businesspeople 19th-century American Episcopalians 20th-century American businesspeople 20th-century American Episcopalians American art collectors American bankers American book and manuscript collectors American financial company founders American financiers American railway entrepreneurs Burials at Cedar Hill Cemetery (Hartford, Connecticut) Businesspeople from Hartford, Connecticut Businesspeople from New York City Cheshire Academy alumni English High School of Boston alumni General Electric people Gilded Age J. P. JPMorgan Chase employees Knights of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus Members of the New York Yacht Club .J. P. Philanthropists from New York (state) Presidents of the Metropolitan Museum of Art U.S. Steel people University of Göttingen alumni

Guglielmo Marconi

Guglielmo Giovanni Maria Marconi, 1st Marquis of Marconi (; 25 April 187420 July 1937) was an Italians, Italian inventor and electrical engineering, electrical engineer, known for his creation of a practical radio wave-based Wireless telegrap ...

. Morgan agreed to give Tesla $150,000 () to build the system in return for a 51% control of the patents. Almost as soon as the contract was signed Tesla decided to scale up the facility to include his ideas of terrestrial wireless power transmission

Wireless power transfer (WPT), wireless power transmission, wireless energy transmission (WET), or electromagnetic power transfer is the transmission of electrical energy without wires as a physical link. In a wireless power transmission system ...

to make what he thought was a more competitive system. Morgan considered Tesla's changes (and requests for the additional amounts of money to build it) a breach of contract and refused to fund the changes. With no additional investment capital available, the project at Wardenclyffe was abandoned in 1906, and never became operational.

London Underground

Morgan suffered a rare business defeat in 1902 when he attempted to build and operate a line on theLondon Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent ceremonial counties of England, counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and He ...

. Transit magnate Charles Tyson Yerkes

Charles Tyson Yerkes Jr. ( ; June 25, 1837 – December 29, 1905) was an American financier. He played a part in developing mass-transit systems in Chicago and London.

Philadelphia

Yerkes was born into a Quaker family in the Northern Liberties, ...

thwarted Morgan's effort to obtain parliamentary authority to build the Piccadilly, City and North East London Railway, a subway line that would have competed with "tube" lines controlled by Yerkes. Morgan called Yerkes' coup "the greatest rascality and conspiracy I ever heard of".

International Mercantile Marine

In 1902, J.P. Morgan & Co. financed the formation ofInternational Mercantile Marine Company

The International Mercantile Marine Company, originally the International Navigation Company, was a trust formed in the early twentieth century as an attempt by J.P. Morgan to monopolize the shipping trade.

IMM was founded by shipping magnate ...

(IMMC), an Atlantic shipping company which absorbed several major American and British lines in an attempt to monopolize the shipping trade. IMMC was a holding company that controlled subsidiary corporations that had their own operating subsidiaries. Morgan hoped to dominate transatlantic shipping through interlocking directorates and contractual arrangements with the railroads, but that proved impossible because of the unscheduled nature of sea transport, American antitrust legislation, and an agreement with the British government. One of IMMC's subsidiaries was the White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between t ...

, which owned the RMS ''Titanic''. The ship's famous sinking in 1912, the year before Morgan's death, was a financial disaster for IMMC, which was forced to apply for bankruptcy protection in 1915. Analysis of financial records shows that IMMC was over-leveraged and suffered from inadequate cash flow causing it to default on bond interest payments. Saved by World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, IMMC eventually re-emerged as the United States Lines

United States Lines was the trade name of an organization of the United States Shipping Board (USSB), Emergency Fleet Corporation (EFC) created to operate German liners seized by the United States in 1917. The ships were owned by the USSB and all ...

, which went bankrupt in 1986.

Morgan corporations

From 1890 to 1913, 42 major corporations were organized or their securities wereunderwritten

Underwriting (UW) services are provided by some large financial institutions, such as banks, insurance companies and investment houses, whereby they guarantee payment in case of damage or financial loss and accept the financial risk for liabilit ...

, in whole or part, by J.P. Morgan and Company.

Manufacturing and construction industry

*

* American Bridge Company

The American Bridge Company is a heavy/civil construction firm that specializes in building and renovating bridges and other large, complex structures. Founded in 1900, the company is headquartered in Coraopolis, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Pitts ...

* American Telephone & Telegraph

AT&T Corporation, originally the American Telephone and Telegraph Company, is the subsidiary of AT&T Inc. that provides voice, video, data, and Internet telecommunications and professional services to businesses, consumers, and government agen ...

* Associated Merchants

* Atlas Portland Cement Company

* Boomer Coal & Coke

* Federal Steel Company

* General Electric

General Electric Company (GE) is an American multinational conglomerate founded in 1892, and incorporated in New York state and headquartered in Boston. The company operated in sectors including healthcare, aviation, power, renewable energ ...

* Hartford Carpet Corporation

* Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company

* International Harvester

The International Harvester Company (often abbreviated by IHC, IH, or simply International ( colloq.)) was an American manufacturer of agricultural and construction equipment, automobiles, commercial trucks, lawn and garden products, household e ...

* International Mercantile Marine

The International Mercantile Marine Company, originally the International Navigation Company, was a trust formed in the early twentieth century as an attempt by J.P. Morgan to monopolize the shipping trade.

IMM was founded by shipping magnates ...

* J. I. Case Threshing Machine

The Case Corporation was a manufacturer of agricultural machinery and construction equipment. Founded, in 1842, by Jerome Increase Case as the J. I. Case Threshing Machine Company, it operated under that name for most of a century. For ano ...

* National Tube

* United Dry Goods

Associated Dry Goods Corporation (ADG) was a chain of department stores that merged with May Department Stores in 1986. It was founded in 1916 as an association of independent stores called American Dry Goods, based in New York City.

History

T ...

* United States Steel Corporation

United States Steel Corporation, more commonly known as U.S. Steel, is an American integrated steel producer headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with production operations primarily in the United States of America and in several countries ...

Railroads

*Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway , often referred to as the Santa Fe or AT&SF, was one of the larger railroads in the United States. The railroad was chartered in February 1859 to serve the cities of Atchison, Kansas, Atchison and Top ...

* Atlantic Coast Line

* Central of Georgia Railway

* Chesapeake and Ohio Railway

The Chesapeake and Ohio Railway was a Class I railroad formed in 1869 in Virginia from several smaller Virginia railroads begun in the 19th century. Led by industrialist Collis P. Huntington, it reached from Virginia's capital city of Richmond t ...

* Chicago and Western Indiana Railroad

The Chicago and Western Indiana Railroad was the owner of Dearborn Station in Chicago and the trackage leading to it. It was owned equally by five of the railroads using it to reach the terminal, and kept those companies from needing their own ...

* Chicago, Burlington and Quincy

The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad was a railroad that operated in the Midwestern United States. Commonly referred to as the Burlington Route, the Burlington, or as the Q, it operated extensive trackage in the states of Colorado, Illin ...

* Chicago Great Western Railway

The Chicago Great Western Railway was a Class I railroad that linked Chicago, Minneapolis, Omaha, and Kansas City. It was founded by Alpheus Beede Stickney in 1885 as a regional line between St. Paul and the Iowa state line called the Minnesota a ...

* Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railroad

* Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railway

The Elgin, Joliet and Eastern Railway was a Class I railroad, operating between Waukegan, Illinois and Gary, Indiana. The railroad served as a link between Class I railroads traveling to and from Chicago, although it operated almost entirely wit ...

* Erie Railroad

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the northeastern United States, originally connecting New York City — more specifically Jersey City, New Jersey, where Erie's Pavonia Terminal, long demolished, used to stand — with Lake Erie ...

* Florida East Coast Railway

The Florida East Coast Railway is a Class II railroad operating in the U.S. state of Florida, currently owned by Grupo México.

Built primarily in the last quarter of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century, the FEC was a pr ...

* Hocking Valley Railway

The Hocking Valley Railway was a railroad in the U.S. state of Ohio, with a main line from Toledo to Athens and Pomeroy via Columbus. It also had several branches to the coal mines of the Hocking Valley near Athens. The company became part of ...

* Lehigh Valley Railroad

The Lehigh Valley Railroad was a railroad built in the Northeastern United States to haul anthracite coal from the Coal Region in Pennsylvania. The railroad was authorized on April 21, 1846 for freight and transportation of passengers, goods, w ...

* Louisville and Nashville Railroad

The Louisville and Nashville Railroad , commonly called the L&N, was a Class I railroad that operated freight and passenger services in the southeast United States.

Chartered by the Commonwealth of Kentucky in 1850, the road grew into one of the ...

* New York Central System

The New York Central Railroad was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Mid ...

* New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad

The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad , commonly known as The Consolidated, or simply as the New Haven, was a railroad that operated in the New England region of the United States from 1872 to December 31, 1968. Founded by the merger of ...

* New York, Ontario and Western Railway

The New York, Ontario and Western Railway, more commonly known as the O&W or NYO&W, was a regional railroad with origins in 1868, lasting until March 29, 1957 (the last train ran from Norwich to Middletown, NY on this date), after which it was or ...

* Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, whic ...

* Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad (reporting mark PRR), legal name The Pennsylvania Railroad Company also known as the "Pennsy", was an American Class I railroad that was established in 1846 and headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. It was named ...

* Pere Marquette Railroad

The Pere Marquette Railway operated in the Great Lakes region of the United States and southern parts of Ontario in Canada. It had trackage in the states of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana and the Canadian province of Ontario. Its primary connections in ...

* Reading Railroad

The Reading Company ( ) was a Philadelphia-headquartered railroad that provided passenger and commercial rail transport in eastern Pennsylvania and neighboring states that operated from 1924 until its 1976 acquisition by Conrail.

Commonly calle ...

* St. Louis–San Francisco Railway

The St. Louis–San Francisco Railway , commonly known as the "Frisco", was a railroad that operated in the Midwest and South Central United States from 1876 to April 17, 1980. At the end of 1970, it operated of road on of track, not includi ...

* Southern Railway

* Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis

The Terminal Railroad Association of St. Louis is a Class III switching and terminal railroad that handles traffic in the St. Louis, Missouri, metropolitan area. It is co-owned by five of the six Class I railroads that reach the city.

Present ope ...

Later years

Morgan was a member of the Union Club in New York City. When a friend,

Morgan was a member of the Union Club in New York City. When a friend, Erie Railroad

The Erie Railroad was a railroad that operated in the northeastern United States, originally connecting New York City — more specifically Jersey City, New Jersey, where Erie's Pavonia Terminal, long demolished, used to stand — with Lake Erie ...

president John King, was blackballed, Morgan resigned and organized the Metropolitan Club

The Metropolitan Club of New York is a private social club on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded as a gentlemen's club in 1891 for men only, but it was one of the first major clubs in New York to admit women, t ...

of New York. He donated the land on 5th Avenue and 60th Street at a cost of $125,000, and commanded Stanford White

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect. He was also a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms. He designed many houses for the rich, in additio ...

to "...build me a club fit for gentlemen, forget the expense..." He invited King in as a charter member and served as club president from 1891 to 1900.

Personal life

Marriages and children

In 1861, Morgan married Amelia Sturges, called Mimi (1835–1862). He married Frances Louisa "Fanny" Tracy (1842–1924), on May 31, 1865. They had four children: * Louisa Pierpont Morgan (1866–1946), who marriedHerbert L. Satterlee

Herbert Livingston Satterlee (October 31, 1863 – July 14, 1947) was an American lawyer, writer, and businessman who served as the Assistant Secretary of the Navy from 1908 to 1909.

Early life

Herbert Livingston Satterlee was born in New York Cit ...

(1863–1947)

* J. P. Morgan Jr.

John Pierpont Morgan Jr. (September 7, 1867 – March 13, 1943) was an American banker, finance executive, and philanthropist. He inherited the family fortune and took over the business interests including J.P. Morgan & Co. after his father J. P ...

(1867–1943), who married Jane Norton Grew

* Juliet Pierpont Morgan (1870–1952), who married William Pierson Hamilton (1869–1950)

* Anne Tracy Morgan (1873–1952), philanthropist

Appearance

Morgan often had a tremendous physical effect on people; one man said that a visit from Morgan left him feeling "as if a gale had blown through the house." He was physically large with massive shoulders, piercing eyes, and a purple nose. He was known to dislike publicity and hated being photographed without his permission; as a result of his self-consciousness of his rosacea, all of his professional portraits were retouched. His deformed nose was due to a disease called

Morgan often had a tremendous physical effect on people; one man said that a visit from Morgan left him feeling "as if a gale had blown through the house." He was physically large with massive shoulders, piercing eyes, and a purple nose. He was known to dislike publicity and hated being photographed without his permission; as a result of his self-consciousness of his rosacea, all of his professional portraits were retouched. His deformed nose was due to a disease called rhinophyma

Rhinophyma is a condition causing development of a large, bulbous nose associated with granulomatous infiltration, commonly due to untreated rosacea. The condition is most common in older white males.

Colloquial terms for the rhinophyma includ ...

, which can result from rosacea. As the deformity worsens, pits, nodules, fissures, lobulations, and pedunculation contort the nose. This condition inspired the crude taunt "Johnny Morgan's nasal organ has a purple hue." Surgeons could have shaved away the rhinophymous growth of sebaceous tissue during Morgan's lifetime, but as a child he suffered from infantile seizures, and Morgan's son-in-law, Herbert L. Satterlee, has speculated that he did not seek surgery for his nose because he feared the seizures would return.

His social and professional self-confidence were too well established to be undermined by this affliction. It appeared as if he dared people to meet him squarely and not shrink from the sight, asserting the force of his character over the ugliness of his face.

Religion

Morgan was a lifelong member of the Episcopal Church, and by 1890 was one of its most influential leaders. He was a founding member of the Church Club of New York, an Episcopal private member's club in Manhattan. Morgan was appointed as one of the first laymen on the committee that created the 1892 revision of the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'', where he petitioned for the creation of a special limited collectible printing that he later financed. In 1910, the General Convention The General Convention is the primary governing and legislative body of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America. With the exception of the Bible, the Book of Common Prayer, and the Constitution and Canons, it is the ultimate authority ...

of the Episcopal Church established a commission, proposed by Bishop Charles Brent, to implement a world conference of churches to address their differences in their “faith

Faith, derived from Latin ''fides'' and Old French ''feid'', is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or In the context of religion, one can define faith as "belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

Religious people often ...

and order.” Morgan was so impressed by the proposal for such a conference that he contributed $100,000 to finance the commission's work.

Homes

His house at 219 Madison Avenue was originally built in 1853 by John Jay Phelps and purchased by Morgan in 1882. It became the first electrically lit private residence in New York. His interest in the new technology was a result of his financing

His house at 219 Madison Avenue was originally built in 1853 by John Jay Phelps and purchased by Morgan in 1882. It became the first electrically lit private residence in New York. His interest in the new technology was a result of his financing Thomas Alva Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These invention ...

's Edison Electric Illuminating Company in 1878. It was there that a reception of 1,000 people was held for the marriage of Juliet Morgan and William Pierson Hamilton on April 12, 1894, where they were given a favorite clock of Morgan's. Morgan also owned the "Cragston" estate, located in Highland Falls, New York

Highland Falls, formerly named Buttermilk Falls, is a village in Orange County, New York, United States. The population was 3,900 at the 2010 census. The village was founded in 1906. It is part of the Poughkeepsie– Newburgh– Middletow ...

. His son, of the same name, was the owner of East Island in Glen Cove, New York

Glen Cove is a Political subdivisions of New York State#City, city in Nassau County, New York, United States, on the North Shore (Long Island), North Shore of Long Island. At the 2020 United States Census, the city population was 28,365 as of th ...

.

J.P. Morgan spent three months of every year in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

and owned two houses there. His 'town' house, 13 Prince's Gate was inherited from his father and was later expanded by the acquisition of the neighbouring Number 14 to house his growing art collection. After his death the merged houses were offered to the US government for use as the residence of the US Ambassador

Ambassadors of the United States are persons nominated by the president to serve as the country's diplomatic representatives to foreign nations, international organizations, and as ambassadors-at-large. Under Article II, Section 2 of the U.S ...

, from 1929 to 1955. His other property was Dover House, Putney

Putney () is a district of southwest London, England, in the London Borough of Wandsworth, southwest of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

History

Putney is an ancient paris ...

, which was later demolished and developed into the Dover House Estate

Dover House Estate is one of a number of important London County Council cottage estates inspired by the Garden city movement. The land was previously the estates of two large houses, ''Dover House'' and ''Putney Park House'', which were purchas ...

.

Yachting

An avid yachtsman, Morgan owned several large yachts, the first being the ''Corsair'', built by

An avid yachtsman, Morgan owned several large yachts, the first being the ''Corsair'', built by William Cramp & Sons

William Cramp & Sons Shipbuilding Company (also known as William Cramp & Sons Ship & Engine Building Company) of Philadelphia was founded in 1830 by William Cramp, and was the preeminent U.S. iron shipbuilder of the late 19th century.

Company hi ...

for Charles J. Osborn (1837–1885) and launched on May 26, 1880. Charles J. Osborn was Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made hi ...

's private banker. Morgan bought the yacht in 1882. The well-known quote, "If you have to ask the price, you can't afford it" is commonly attributed to Morgan in response to a question about the cost of maintaining a yacht, although the story is unconfirmed. A similarly unconfirmed legend attributes the quote to his son, J. P. Morgan Jr.

John Pierpont Morgan Jr. (September 7, 1867 – March 13, 1943) was an American banker, finance executive, and philanthropist. He inherited the family fortune and took over the business interests including J.P. Morgan & Co. after his father J. P ...

, in connection with the launching of the son's yacht ''Corsair IV'' at Bath Iron Works

Bath Iron Works (BIW) is a major United States shipyard located on the Kennebec River in Bath, Maine, founded in 1884 as Bath Iron Works, Limited. Since 1995, Bath Iron Works has been a subsidiary of General Dynamics. It is the fifth-largest de ...

in 1930.

Morgan was scheduled to travel on the ill-fated maiden voyage of the , but canceled at the last minute, choosing to remain at a resort in Aix-les-Bains

Aix-les-Bains (, ; frp, Èx-los-Bens; la, Aquae Gratianae), locally simply Aix, is a commune in the southeastern French department of Savoie.

, France. The White Star Line

The White Star Line was a British shipping company. Founded out of the remains of a defunct packet company, it gradually rose up to become one of the most prominent shipping lines in the world, providing passenger and cargo services between t ...

, which operated ''Titanic'', was part of Morgan's International Mercantile Marine Company, and Morgan was to have his own private suite and promenade deck on the ship. In response to the sinking of ''Titanic'', Morgan purportedly said:

Collector

Morgan was a collector of books, pictures, paintings, clocks and other art objects, many loaned or given to theMetropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

(of which he was president and was a major force in its establishment), and many housed in his London house and in his private library on 36th Street, near Madison Avenue

Madison Avenue is a north-south avenue in the borough of Manhattan in New York City, United States, that carries northbound one-way traffic. It runs from Madison Square (at 23rd Street) to meet the southbound Harlem River Drive at 142nd Stre ...

in New York City.

For a number of years the British artist and art critic Roger Fry worked for the museum, and in effect for Morgan, as a collector.

His son, J. P. Morgan Jr., made the Pierpont Morgan Library

The Morgan Library & Museum, formerly the Pierpont Morgan Library, is a museum and research library in the Murray Hill neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It is situated at 225 Madison Avenue, between 36th Street to the south and 37th ...

a public institution in 1924 as a memorial to his father, and kept Belle da Costa Greene

Belle da Costa Greene (November 26, 1879 – May 10, 1950) was an American librarian best known for managing and developing the personal library of J. P. Morgan. After Morgan's death in 1913, Greene continued as librarian for his son, Jack ...

, his father's private librarian, as its first director.

Benefactor

Morgan was a benefactor of the Morgan Library and Museum, theAmerican Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

, the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

, the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

, Groton School

Groton School (founded as Groton School for Boys) is a private college-preparatory boarding school located in Groton, Massachusetts. Ranked as one of the top five boarding high schools in the United States in Niche (2021–2022), it is affiliated ...

, Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

(especially its medical school

A medical school is a tertiary educational institution, or part of such an institution, that teaches medicine, and awards a professional degree for physicians. Such medical degrees include the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS, M ...

), Trinity College Trinity College may refer to:

Australia

* Trinity Anglican College, an Anglican coeducational primary and secondary school in , New South Wales

* Trinity Catholic College, Auburn, a coeducational school in the inner-western suburbs of Sydney, New ...

, the Lying-in Hospital

A maternity hospital specializes in caring for women during pregnancy and childbirth. It also provides care for newborn infants, and may act as a centre for clinical training in midwifery and obstetrics. Formerly known as lying-in hospitals, most ...

of the City of New York, and the New York trade schools.

Gem collector

By the turn of the century, Morgan had become one of America's most important collectors of gems and had assembled the most important gem collection in the U.S. as well as of American gemstones (over 1,000 pieces). Tiffany & Co. assembled his first collection under their Chief Gemologist,

By the turn of the century, Morgan had become one of America's most important collectors of gems and had assembled the most important gem collection in the U.S. as well as of American gemstones (over 1,000 pieces). Tiffany & Co. assembled his first collection under their Chief Gemologist, George Frederick Kunz

George Frederick Kunz (September 29, 1856 – June 29, 1932) was an American mineralogist and mineral collector.

Biography

Kunz was born in Manhattan, New York City, USA, and began an interest in minerals at a very young age. By his teens, he ...

. The collection was exhibited at the World's Fair in Paris in 1889. The exhibit won two golden awards and drew the attention of important scholars, lapidaries, and the general public.

George Frederick Kunz continued to build a second, even finer, collection which was exhibited in Paris in 1900. These collections have been donated to the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

in New York, where they were known as the Morgan-Tiffany and the Morgan-Bement collections. In 1911 Kunz named a newly found gem after his best customer morganite

Morganite is an orange or pink gemstone and is also a variety of beryl. Morganite can be mined in countries like Brazil, Afghanistan, Mozambique, Namibia, the United States, and Madagascar.

Morganite has grown in popularity since 2010. ''Brides ...

.

Photography

Morgan was a patron to photographerEdward S. Curtis

Edward Sherriff Curtis (February 19, 1868 – October 19, 1952) was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and on Native American people. Sometimes referred to as the "Shadow Catcher", Curtis travele ...

, offering Curtis $75,000 in 1906, to create a series on the American Indians. Curtis eventually published a 20-volume work entitled ''The North American Indian''. Curtis also produced a motion picture, '' In the Land of the Head Hunters'' (1914), which was restored in 1974 and re-released as ''In the Land of the War Canoes''. Curtis was also famous for a 1911 magic lantern

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name , is an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates (usually made of glass), one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a si ...

slide show ''The Indian Picture Opera

''The Indian Picture Opera'' is a magic lantern slide show by photographer Edward S. Curtis. In the early 1900s, Curtis published the renowned 20-volume book subscription entitled ''The North American Indian''. He compiled about 2400 photograph ...

'' which used his photos and original musical compositions by composer Henry F. Gilbert.

Other

Morgan smoked dozens of cigars per day and favored large Havana cigars dubbed ''Hercules' Clubs'' by observers.Death

Morgan died while traveling abroad on March 31, 1913, just shy of his 76th birthday. He died in his sleep at the Grand Hotel Plaza in Rome, Italy. His body was brought back to America aboard the , a French Line passenger ship. Flags on Wall Street flew athalf-staff

Half-mast or half-staff (American English) refers to a flag flying below the summit of a ship mast, a pole on land, or a pole on a building. In many countries this is seen as a symbol of respect, mourning, distress, or, in some cases, a salu ...

, and in an honor usually reserved for heads of state, the stock market closed for two hours when his body passed through New York City. His body was brought to lie in his home and adjacent library the first night of arrival in New York City. His remains were interred in the Cedar Hill Cemetery in his birthplace of Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

. His son, John Pierpont "Jack" Morgan Jr., inherited the banking business. He bequeathed his mansion and large book collections to the Morgan Library & Museum

The Morgan Library & Museum, formerly the Pierpont Morgan Library, is a museum and research library in the Murray Hill neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City. It is situated at 225 Madison Avenue, between 36th Street to the south and 37th S ...

in New York.

His estate was worth $68.3 million ($1.39 billion in today's dollars based on

His estate was worth $68.3 million ($1.39 billion in today's dollars based on CPI

A consumer price index (CPI) is a price index, the price of a weighted average market basket of consumer goods and services purchased by households. Changes in measured CPI track changes in prices over time.

Overview

A CPI is a statistic ...

, or $25.2 billion based on share of GDP), of which about $30 million represented his share in the New York and Philadelphia banks. The value of his art collection was estimated at $50 million.

Legacy

His son,J. P. Morgan Jr.

John Pierpont Morgan Jr. (September 7, 1867 – March 13, 1943) was an American banker, finance executive, and philanthropist. He inherited the family fortune and took over the business interests including J.P. Morgan & Co. after his father J. P ...

, took over the business at his father's death, but he was never as influential. As required by the 1933 Glass–Steagall Act, the "House of Morgan" became three entities: J.P. Morgan & Co., which later became Morgan Guaranty Trust

J.P. Morgan & Co. is a commercial and investment banking institution founded by J. P. Morgan in 1871. Through a series of mergers and acquisitions, the company is now a subsidiary of JPMorgan Chase, one of the largest banking institutions in ...

; Morgan Stanley

Morgan Stanley is an American multinational investment management and financial services company headquartered at 1585 Broadway in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. With offices in more than 41 countries and more than 75,000 employees, the fir ...

, an investment house formed by his grandson Henry Sturgis Morgan

Henry Sturgis Morgan Sr. (October 24, 1900 – February 8, 1982) was an American banker, known for being the co-founder of Morgan Stanley and the president and chairman of the Morgan Library & Museum.

Early life and education

Morgan was b ...

; and Morgan Grenfell

Morgan, Grenfell & Co. was a leading London-based investment bank regarded as one of the oldest and once most influential British merchant banks. It had its origins in a merchant banking business commenced by George Peabody. Junius Spencer Morgan ...

in London, an overseas securities house.

The gemstone

The gemstone morganite

Morganite is an orange or pink gemstone and is also a variety of beryl. Morganite can be mined in countries like Brazil, Afghanistan, Mozambique, Namibia, the United States, and Madagascar.

Morganite has grown in popularity since 2010. ''Brides ...

was named in his honor.

The Cragston Dependencies

Cragston Dependencies is a group of historic buildings located at Highlands in Orange County, New York. They were built about 1860 as part of the Cragston estate of J. P. Morgan (1837–1913). They consist of a house, barn, well, carriage house, ...

, associated with his estate, Cragston (at Highlands, New York

Highlands is a town on the eastern border of Orange County, New York. The population was 12,492 at the 2010 census. West Point, including the United States Military Academy, is located alongside the Hudson River in Highlands, and the military re ...

), was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 1982.

Popular culture

* A contemporary literary biography of Morgan is used as an allegory for the financial environment in America after World War I in the second volume, ''Nineteen Nineteen'', ofJohn Dos Passos

John Roderigo Dos Passos (; January 14, 1896 – September 28, 1970) was an American novelist, most notable for his ''U.S.A.'' trilogy.

Born in Chicago, Dos Passos graduated from Harvard College in 1916. He traveled widely as a young man, visit ...

' ''U.S.A.'' trilogy.

* Morgan appears as a character in Caleb Carr's novel ''The Alienist