Indo-Pakistani War Of 1947–1948 on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, or the First Kashmir War, was a war fought between

in ''

The years 1946–1947 saw the rise of

The years 1946–1947 saw the rise of

With the independence of the Dominions, the

With the independence of the Dominions, the

Sometime in August 1947, the first signs of trouble broke out in

Sometime in August 1947, the first signs of trouble broke out in

Scholar

Scholar  Meanwhile, Sardar Ibrahim had escaped to West Punjab, along with dozens of rebels, and established a base in

Meanwhile, Sardar Ibrahim had escaped to West Punjab, along with dozens of rebels, and established a base in  The Maharaja was increasingly driven to the wall with the rebellion in the western districts and the Pakistani blockade. He managed to persuade Justice Mahajan to accept the post of Prime Minister (but not to arrive for another month, for procedural reasons). He sent word to the Indian leaders through Mahajan that he was willing to accede to India but needed more time to implement political reforms. However, it was India's position that it would not accept accession from the Maharaja unless it had the people's support. The Indian Prime Minister

The Maharaja was increasingly driven to the wall with the rebellion in the western districts and the Pakistani blockade. He managed to persuade Justice Mahajan to accept the post of Prime Minister (but not to arrive for another month, for procedural reasons). He sent word to the Indian leaders through Mahajan that he was willing to accede to India but needed more time to implement political reforms. However, it was India's position that it would not accept accession from the Maharaja unless it had the people's support. The Indian Prime Minister

In May 1948, the Pakistani army officially entered the conflict, in theory to defend the Pakistan borders, but it made

plans to push towards Jammu and cut the lines of communications of the Indian forces in the Mehndar Valley.

In

In May 1948, the Pakistani army officially entered the conflict, in theory to defend the Pakistan borders, but it made

plans to push towards Jammu and cut the lines of communications of the Indian forces in the Mehndar Valley.

In

On 22 October the Pashtun tribal attack was launched in the Muzaffarabad sector. The state forces stationed in the border regions around

On 22 October the Pashtun tribal attack was launched in the Muzaffarabad sector. The state forces stationed in the border regions around

After the accession, India airlifted troops and equipment to Srinagar under the command of Lt. Col.

After the accession, India airlifted troops and equipment to Srinagar under the command of Lt. Col.

Indian forces ceased pursuit of tribal forces after recapturing Uri and Baramula, and sent a

Indian forces ceased pursuit of tribal forces after recapturing Uri and Baramula, and sent a

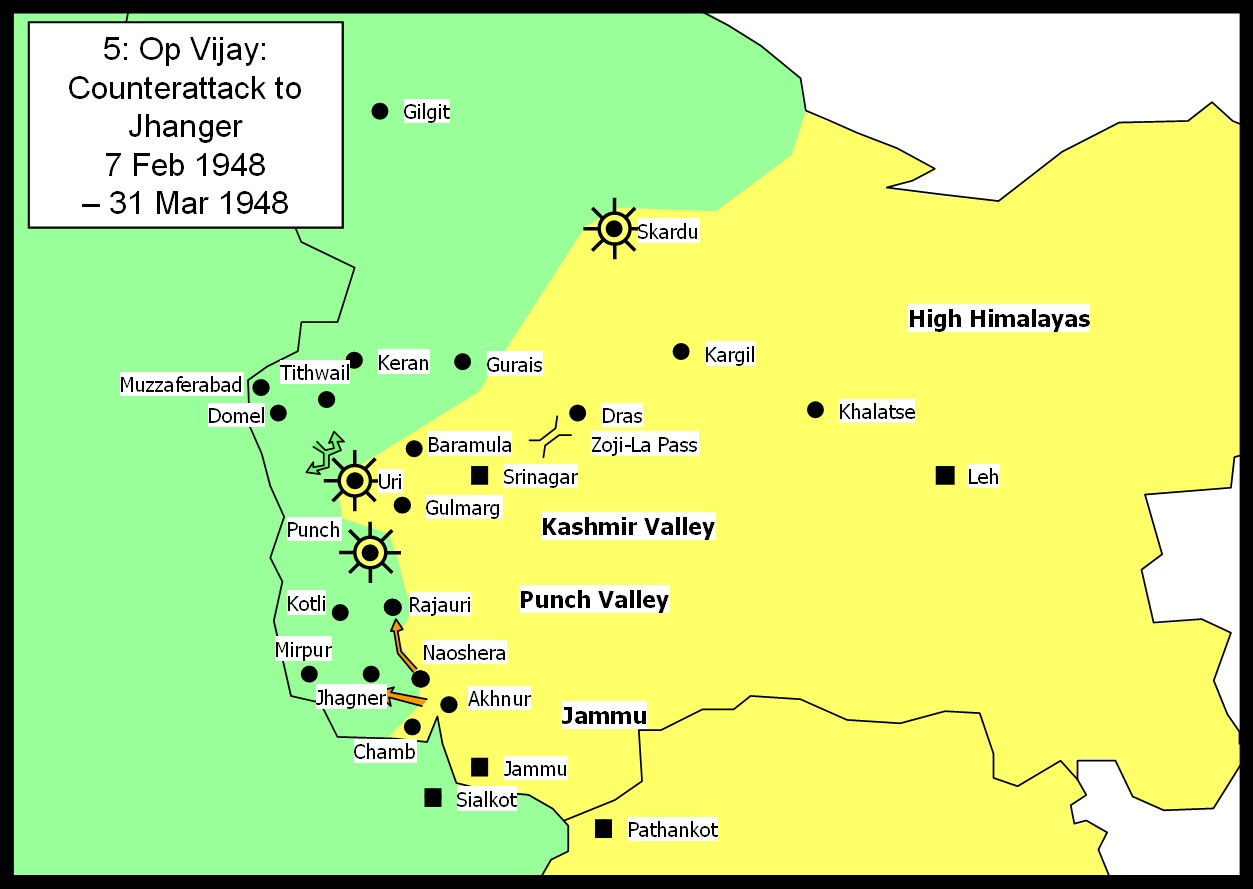

The tribal forces attacked and captured Jhanger. They then attacked Naoshera unsuccessfully, and made a series of unsuccessful attacks on

The tribal forces attacked and captured Jhanger. They then attacked Naoshera unsuccessfully, and made a series of unsuccessful attacks on

File:J&K06low.jpg, Indian Spring Offensive 1 May 1948 – 19 May 1948

File:J&K07low.jpg, Indian Spring Offensive 19 May 1948 – 14 August 1948

After protracted negotiations, both countries agreed to a cease-fire. The terms of the cease-fire, laid out in a UN Commission resolution on 13 August 1948, were adopted by the commission on 5 January 1949. This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimal forces within the state to preserve law and order. Upon compliance with these conditions, a

After protracted negotiations, both countries agreed to a cease-fire. The terms of the cease-fire, laid out in a UN Commission resolution on 13 August 1948, were adopted by the commission on 5 January 1949. This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimal forces within the state to preserve law and order. Upon compliance with these conditions, a

Partition and Indo Pak War of 1947–48

Indian Army, archived 5 April 2011. {{DEFAULTSORT:Indo-Pakistani War Of 1947 1947 in India 1948 in India 1949 in India Conflicts in 1947 Conflicts in 1948 Conflicts in 1949 Government of Liaquat Ali Khan History of Azad Kashmir History of Pakistan Indo-Pakistani wars

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

over the princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj, British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, ...

of Jammu and Kashmir from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four Indo-Pakistani wars

Since the Partition of India, Partition of British India in 1947 and subsequent creation of the dominions of Dominion of India, India and Dominion of Pakistan, Pakistan, the two countries have been involved in a number of wars, conflicts, and m ...

that was fought between the two newly independent nations. Pakistan precipitated the war a few weeks after its independence by launching tribal ''lashkar

Lashkar may refer to:

* Lascar, a type of sailor or militiaman employed by the British in South Asia (modern Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan)

* Lashkar (film), ''Lashkar'' (film), a 1989 Bollywood film

* Laskhar (novel), ''Laskhar'' (novel), a 2008 ...

'' (militias) from Waziristan

Waziristan (Pashto and ur, , "land of the Wazir") is a mountainous region covering the former FATA agencies of North Waziristan and South Waziristan which are now districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Waziristan covers some . ...

, in an effort to capture Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

and to preempt the possibility of its ruler joining India. The inconclusive result of the war still affects the geopolitics of both countries.

Hari Singh

Maharaja Sir Hari Singh (September 1895 – 26 April 1961) was the last ruling Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir (princely state), Jammu and Kashmir.

Hari Singh was the son of Amar Singh and Bhotiali Chib. In 1923, followi ...

, the Maharaja

Mahārāja (; also spelled Maharajah, Maharaj) is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king" or " high king".

A few ruled states informally called empires, including ruler raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, an ...

of Jammu and Kashmir, was facing an uprising by his Muslim subjects in Poonch Poonch, sometimes also spelt Punchh, may refer to:

* Historical Poonch District, a district in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in British India, split in 1947 between:

** Poonch district, India

** Poonch Division, in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, ...

, and lost control of the western districts of his kingdom. On 22 October 1947, Pakistan's Pashtun tribal militias crossed the border of the state. These local tribal militias and irregular Pakistani forces moved to take the capital city of Srinagar

Srinagar (English: , ) is the largest city and the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, India. It lies in the Kashmir Valley on the banks of the Jhelum River, a tributary of the Indus, and Dal and Anchar lakes. The city is known for its natu ...

, but upon reaching Baramulla

Baramulla (), also known as Varmul () in Kashmiri, is a town and a municipality in the Baramulla district in the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. It is also the administrative headquarters of the Baramulla district. It is on the ...

, they took to plunder and stalled. Maharaja Hari Singh made a plea to India for assistance, and help was offered, but it was subject to his signing of an Instrument of Accession to India.

The war was initially fought by the Jammu and Kashmir State Forces

Jammu is the winter capital of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. It is the headquarters and the largest city in Jammu district of the union territory. Lying on the banks of the river Tawi, the city of Jammu, with an area of , ...

and by militias from the frontier tribal areas adjoining the North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ps, شمال لویدیځ سرحدي ولایت, ) was a Chief Commissioner's Province of British India, established on 9 November 1901 from the north-western districts of the Punjab Province. Followin ...

.Kashmirin ''

Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

'' (2011), online edition Following the accession of the state to India on 26 October 1947, Indian troops were airlifted to Srinagar

Srinagar (English: , ) is the largest city and the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir, India. It lies in the Kashmir Valley on the banks of the Jhelum River, a tributary of the Indus, and Dal and Anchar lakes. The city is known for its natu ...

, the state capital. British commanding officers initially refused the entry of Pakistani troops into the conflict, citing the accession of the state to India. However, later in 1948, they relented and Pakistan's armies entered the war shortly afterwards. The fronts solidified gradually along what later came to be known as the Line of Control

The Line of Control (LoC) is a military control line between the Indian and Pakistanicontrolled parts of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir—a line which does not constitute a legally recognized international boundary, but serve ...

. A formal ceasefire was declared effective 1 January 1949.

Background

Prior to 1815, the area now known as "Jammu and Kashmir" comprised 22 small independent states (16 Hindu and six Muslim) carved out of territories controlled by the Amir (King) ofAfghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, combined with those of local small rulers. These were collectively referred to as the "Punjab Hill States". These small states, ruled by Rajput kings, were variously independent, vassals of the Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire was an early-modern empire that controlled much of South Asia between the 16th and 19th centuries. Quote: "Although the first two Timurid emperors and many of their noblemen were recent migrants to the subcontinent, the d ...

since the time of Emperor Akbar

Abu'l-Fath Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar (25 October 1542 – 27 October 1605), popularly known as Akbar the Great ( fa, ), and also as Akbar I (), was the third Mughal emperor, who reigned from 1556 to 1605. Akbar succeeded his father, Hum ...

or sometimes controlled from Kangra state

Kangra-Lambagraon was a historical princely estate (''jagir'') of British India located in the present-day state of Himachal Pradesh. In 1947, the estate comprised 437 villages, encompassing an area of 324 km2. It had with a Privy Purse o ...

in the Himachal area. Following the decline of the Mughals, turbulence in Kangra and invasions of Gorkhas, the hill states fell successively under the control of the Sikhs under Ranjit Singh

Ranjit Singh (13 November 1780 – 27 June 1839), popularly known as Sher-e-Punjab or "Lion of Punjab", was the first Maharaja of the Sikh Empire, which ruled the northwest Indian subcontinent in the early half of the 19th century. He s ...

.

The First Anglo-Sikh War

The First Anglo-Sikh War was fought between the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company in 1845 and 1846 in and around the Ferozepur district of Punjab. It resulted in defeat and partial subjugation of the Sikh empire and cession of ...

(1845–46) was fought between the Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire was a state originating in the Indian subcontinent, formed under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who established an empire based in the Punjab. The empire existed from 1799, when Maharaja Ranjit Singh captured Lahor ...

, which asserted sovereignty over Kashmir

Kashmir () is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term "Kashmir" denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. Today, the term encompas ...

, and the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Southea ...

. In the Treaty of Lahore

The Treaty of Lahore of 9 March 1846 was a peace-treaty marking the end of the First Anglo-Sikh War. The treaty was concluded, for the British, by the Governor-General Sir Henry Hardinge and two officers of the East India Company and, for the ...

of 1846, the Sikhs were made to surrender the valuable region (the Jullundur Doab) between the Beas River

The Beas River (Sanskrit: ; Hyphasis in Ancient Greek) is a river in north India. The river rises in the Himalayas in central Himachal Pradesh, India, and flows for some to the Sutlej River in the Indian state of Punjab. Its total length is ...

and the Sutlej River and required to pay an indemnity of 1.2 million rupees. Because they could not readily raise this sum, the East India Company allowed the Dogra

The Dogras or Dogra people, are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group in India and Pakistan consisting of the Dogri language speakers. They live predominantly in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir, and in adjoining areas of Punjab, Himachal ...

ruler Gulab Singh

Gulab Singh Jamwal (1792–1857) was the founder of Dogra dynasty and the first Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, the largest princely state under the British Raj, which was created after the defeat of the Sikh Empire in ...

to acquire Kashmir from the Sikh kingdom in exchange for making a payment of 750,000 rupees to the company. Gulab Singh became the first Maharaja

Mahārāja (; also spelled Maharajah, Maharaj) is a Sanskrit title for a "great ruler", "great king" or " high king".

A few ruled states informally called empires, including ruler raja Sri Gupta, founder of the ancient Indian Gupta Empire, an ...

of the newly formed princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Raj, British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, ...

of Jammu and Kashmir, founding a dynasty

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A ...

, that was to rule the state, the second-largest principality during the British Raj

The British Raj (; from Hindi ''rāj'': kingdom, realm, state, or empire) was the rule of the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent;

*

* it is also called Crown rule in India,

*

*

*

*

or Direct rule in India,

* Quote: "Mill, who was himsel ...

, until India gained its independence in 1947.

Partition of India

The years 1946–1947 saw the rise of

The years 1946–1947 saw the rise of All-India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when a group of prominent Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of British India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests on the Indian subcontin ...

and Muslim nationalism, demanding a separate state for India's Muslims. The demand took a violent turn on the Direct Action Day

Direct Action Day (16 August 1946), also known as the 1946 Calcutta Killings, was a day of nationwide communal riots. It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hinduism in India, Hindus in the city of Calcutta (now known as Kolkata) ...

(16 August 1946) and inter-communal violence between Hindus and Muslims became endemic. Consequently, a decision was taken on 3 June 1947 to divide British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

into two separate states, the Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of I ...

comprising the Muslim majority areas and the Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

comprising the rest. The two provinces Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising ...

and Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

with large Muslim-majority areas were to be divided between the two dominions. An estimated 11 million people eventually migrated between the two parts of Punjab, and possibly 1 million perished in the inter-communal violence. Jammu and Kashmir, being adjacent to the Punjab province, was directly affected by the happenings in Punjab.

The original target date for the transfer of power to the new dominions was June 1948. However, fearing the rise of inter-communal violence, the British Viceroy Lord Mountbatten advanced the date to 15 August 1947. This gave only 6 weeks to complete all the arrangements for partition. Mountbatten's original plan was to stay on the joint Governor General for both the dominions till June 1948. However, this was not accepted by the Pakistani leader Mohammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mono ...

. In the event, Mountbatten stayed on as the Governor General of India, whereas Pakistan chose Jinnah as its Governor General. It was envisaged that the nationalisation of the armed forces could not be completed by 15 August. Hence British officers stayed on after the transfer of power. The service chiefs were appointed by the Dominion governments and were responsible to them. The overall administrative control, but not operational control, was vested with Field Marshal Claude Auchinleck

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Army commander during the Second World War. He was a career soldier who spent much of his military career in India, where he rose to become Commander ...

, who was titled the 'Supreme Commander', answerable to a newly formed Joint Defence Council of the two dominions. India appointed General Rob Lockhart

General Sir Rob McGregor MacDonald Lockhart (23 June 1893 – 11 September 1981) was a senior British Army officer during the World War II and later a leading member of the Scout Association. He served as the first Commander-in-Chief of the ...

as its Army chief and Pakistan appointed General Frank Messervy

General Sir Frank Walter Messervy, (9 December 1893 – 2 February 1974) was a British Indian Army officer in the First and Second World Wars. Following its independence, he was the first Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army (15 August 1947 ...

.

The presence of the British commanding officers on both sides made the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 a strange war. The two commanding officers were in daily telephone contact and adopted mutually defensive positions. The attitude was that "you can hit them so hard but not too hard, otherwise there will be all kinds of repercussions." Both Lockhart and Messervy were replaced in the course of war, and their successors Roy Bucher

General Sir Francis Robert Roy Bucher (31 August 1895 – 5 January 1980) was a British soldier who became the second Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army and the final non-Indian to hold the top post of the Indian Army after Partition.

Mili ...

and Douglas Gracey

General Sir Douglas David Gracey & Bar (3 September 1894 – 5 June 1964) was a British Indian Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars. He also fought in French Indochina and was the second Commander-in-Chief of the P ...

tried to exercise restraint on their respective governments. Roy Bucher was apparently successful in doing so in India, but Gracey yielded and let British officers be used in operational roles on the side of Pakistan. One British officer even died in action.

Developments in Jammu and Kashmir (August–October 1947)

With the independence of the Dominions, the

With the independence of the Dominions, the British Paramountcy

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

over the princely states came to an end. The rulers of the states were advised to join one of the two dominions by executing an Instrument of Accession. Maharaja Hari Singh

Maharaja Sir Hari Singh (September 1895 – 26 April 1961) was the last ruling Maharaja of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Hari Singh was the son of Amar Singh and Bhotiali Chib. In 1923, following his uncle's death, Singh became ...

of Jammu and Kashmir, along with his prime minister Ram Chandra Kak

Ram Chandra Kak (5 June 1893 – 10 February 1983) was the prime minister of Jammu and Kashmir during 1945–1947.

One of the very few Kashmiri Pandits to ever hold that post, Kak had the intractable job of navigating the troubled wate ...

, decided not to accede to either dominion. The reasons cited were that the Muslim majority population of the State would not be comfortable with joining India, and that the Hindu and Sikh minorities would become vulnerable if the state joined Pakistan.

In 1947, the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir had a wide range of ethnic and religious communities. The Kashmir province consisting of the Kashmir Valley

The Kashmir Valley, also known as the ''Vale of Kashmir'', is an intermontane valley concentrated in the Kashmir Division of the Indian- union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The valley is bounded on the southwest by the Pir Panjal Range and ...

and the Muzaffarabad district

The Muzaffarabad District ( ur, ) is one of the 10 districts of Pakistan's dependent territory of Azad Kashmir. The district is located on the banks of the Jhelum River, Jhelum and Neelum River, Neelum rivers and is very hilly. The total area of ...

had a majority Muslim population (over 90%). The Jammu province, consisting of five districts, had a roughly equal division of Hindus and Muslims in the eastern districts (Udhampur

Udhampur (ˌʊd̪ʱəmpur) is a city and a municipal council in Udhampur district in the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. It is the headquarters of Udhampur District. Named after Raja Udham Singh, it serves as the district capital ...

, Jammu

Jammu is the winter capital of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), Jammu and Kashmir. It is the headquarters and the largest city in Jammu district of the union territory. Lying on the banks of the river Tawi Ri ...

and Reasi

Reasi is a town and a notified area committee and tehsil in Reasi district of the Indian States and union territories of India, union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), Jammu and Kashmir. Situated at the bank of River Chenab, It ...

) and Muslim majority in the western districts ( Mirpur and Poonch Poonch, sometimes also spelt Punchh, may refer to:

* Historical Poonch District, a district in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in British India, split in 1947 between:

** Poonch district, India

** Poonch Division, in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, ...

). The mountainous Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

district (''wazarat'') in the east had a significant Buddhist presence with a Muslim majority in Baltistan

Baltistan ( ur, ; bft, སྦལ་ཏི་སྟཱན, script=Tibt), also known as Baltiyul or Little Tibet ( bft, སྦལ་ཏི་ཡུལ་།, script=Tibt), is a mountainous region in the Pakistani-administered territory of Gilg ...

. The Gilgit Agency

The Gilgit Agency ( ur, ) was an agency of the British Indian Empire consisting of the subsidiary states of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir at its northern periphery, mainly with the objective of strengthening these territories agains ...

in the north was overwhelmingly Muslim and was directly governed by the British under an agreement with the Maharaja. Shortly before the transfer of power, the British returned the Gilgit Agency to the Maharaja, who appointed a Dogra

The Dogras or Dogra people, are an Indo-Aryan ethno-linguistic group in India and Pakistan consisting of the Dogri language speakers. They live predominantly in the Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir, and in adjoining areas of Punjab, Himachal ...

governor for the district and a British commander for the local forces.

The predominant political movement in the Kashmir Valley, the National Conference led by Sheikh Abdullah

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah (5 December 1905 – 8 September 1982) was an Indian politician who played a central role in the politics of Jammu and Kashmir Abdullah was the founding leader of the All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference (later re ...

, believed in secular politics. It was allied with the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Em ...

and was believed to favour joining India. On the other hand, the Muslims of the Jammu province supported the Muslim Conference, which was allied to the All-India Muslim League

The All-India Muslim League (AIML) was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when a group of prominent Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of British India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests on the Indian subcontin ...

and favoured joining Pakistan. The Hindus of the Jammu province favoured an outright merger with India. In the midst of all the diverging views, the Maharaja's decision to remain independent was apparently a judicious one.

Operation Gulmarg plan

According to Indian military sources, the Pakistani Army prepared a plan called Operation Gulmarg and put it into action as early as 20 August, a few days after Pakistan's independence. The plan was accidentally revealed to an Indian officer, Major O. S. Kalkat serving with the Bannu Brigade. According to the plan, 20 ''lashkars'' (tribal militias), each consisting of 1000 Pashtun tribesmen, were to be recruited from among various Pashtun tribes, and armed at the brigade headquarters atBannu

Bannu ( ps, بنو, translit=banū ; ur, , translit=bannū̃, ) is a city located on the Kurram River in southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. It is the capital of Bannu Division. Bannu's residents are primarily members of the Banuchi tribe ...

, Wanna, Peshawar

Peshawar (; ps, پېښور ; hnd, ; ; ur, ) is the sixth most populous city in Pakistan, with a population of over 2.3 million. It is situated in the north-west of the country, close to the International border with Afghanistan. It is ...

, Kohat

Kohat ( ps, کوهاټ; ur, ) is a city that serves as the capital of the Kohat District in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. It is regarded as a centre of the Bangash tribe of Pashtuns, who have lived in the region since the late 15th century ...

, Thall

Thall ( ps, ټل, ''Ṭəl'') is a town in Thall Tehsil of Hangu District in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is ...

and Nowshera by the first week of September. They were expected to reach the launching point of Abbottabad

Abbottabad (; Urdu, Punjabi language(HINDKO dialect) آباد, translit=aibṭabād, ) is the capital city of Abbottabad District in the Hazara region of eastern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. It is the 40th largest city in Pakistan and fourth ...

on 18 October, and cross into Jammu and Kashmir on 22 October. Ten lashkars were expected to attack the Kashmir Valley

The Kashmir Valley, also known as the ''Vale of Kashmir'', is an intermontane valley concentrated in the Kashmir Division of the Indian- union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The valley is bounded on the southwest by the Pir Panjal Range and ...

through Muzaffarabad

Muzaffarabad (; ur, ) is the capital and largest city of Azad Kashmir, and the 60th largest in Pakistan.

The city is located in Muzaffarabad District, near the confluence of the Jhelum and Neelum rivers. The district is bounded by the Pak ...

and another ten lashkars were expected to join the rebels in Poonch Poonch, sometimes also spelt Punchh, may refer to:

* Historical Poonch District, a district in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in British India, split in 1947 between:

** Poonch district, India

** Poonch Division, in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, ...

, Bhimber

Bhimber ( ur, ) is the capital of Bhimber District, in the Azad Kashmir. The town is on the border between Jammu region and Punjab in Pakistan proper about by road southeast of Mirpur.

History

Bhimber was the capital of the Chibhal dynasty, ...

and Rawalakot

Rawalakot ( ur, ) is the capital of Poonch district in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. It is located in the Pir Panjal Range.

History

Along with Pallandri, Rawalakot was the focal point of the 1955 Poonch uprising. It was led by the local Sudhans ...

with a view to advance to Jammu

Jammu is the winter capital of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), Jammu and Kashmir. It is the headquarters and the largest city in Jammu district of the union territory. Lying on the banks of the river Tawi Ri ...

. Detailed arrangements for the military leadership and armaments were described in the plan.

The regimental records show that, by the last week of August, the Prince Albert Victor's Own Cavalry (PAVO Cavalry) regiment was briefed about the invasion plan. Colonel Sher Khan, the Director of Military Intelligence, was in charge of the briefing, along with Colonels Akbar Khan and Khanzadah. The Cavalry regiment was tasked with procuring arms and ammunition for the 'freedom fighters' and establishing three wings of the insurgent forces: the South Wing commanded by General Kiani, a Central Wing based at Rawalpindi and a North Wing based at Abbottabad. By 1 October, the Cavalry regiment completed the task of arming the insurgent forces. "Throughout the war there was no shortage of small arms, ammunitions, or explosives at any time." The regiment was also told to be on stand by for induction into fighting at an appropriate time.

Scholars have noted considerable movement of Pashtun tribes during September–October. By 13 September, armed Pashtuns drifted into Lahore and Rawalpindi. The Deputy Commissioner of Dera Ismail Khan

Dera Ismail Khan (; bal, , Urdu and skr, , ps, ډېره اسماعيل خان), abbreviated as D.I. Khan, is a city and capital of Dera Ismail Khan District, located in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. It is the 37th largest city of Pakistan ...

noted a scheme to send tribesmen from Malakand to Sialkot

Sialkot ( ur, ) is a city located in Punjab, Pakistan. It is the capital of Sialkot District and the 13th most populous city in Pakistan. The boundaries of Sialkot are joined with Jammu (the winter capital of Indian administered Jammu and Ka ...

, in lorries provided by the Pakistan Government. Preparations for attacking Kashmir were also noted in the princely states of Swat

In the United States, a SWAT team (special weapons and tactics, originally special weapons assault team) is a police tactical unit that uses specialized or military equipment and tactics. Although they were first created in the 1960s to ...

, Dir, and Chitral. Scholar Robin James Moore states there is "little doubt" that Pashtuns were involved in border raids all along the Punjab border from the Indus

The Indus ( ) is a transboundary river of Asia and a trans-Himalayan river of South and Central Asia. The river rises in mountain springs northeast of Mount Kailash in Western Tibet, flows northwest through the disputed region of Kashmir, ...

to the Ravi Ravi may refer to:

People

* Ravi (name), including a list of people and characters with the name

* Ravi (composer) (1926–2012), Indian music director

* Ravi (Ivar Johansen) (born 1976), Norwegian musical artist

* Ravi (music director) (1926–201 ...

.

Pakistani sources deny the existence of any plan called Operation Gulmarg. However, Shuja Nawaz does list 22 Pashtun tribes involved in the invasion of Kashmir on 22 October.

Rebellion in Poonch

Sometime in August 1947, the first signs of trouble broke out in

Sometime in August 1947, the first signs of trouble broke out in Poonch Poonch, sometimes also spelt Punchh, may refer to:

* Historical Poonch District, a district in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in British India, split in 1947 between:

** Poonch district, India

** Poonch Division, in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, ...

, about which diverging views have been received. Poonch was originally an internal ''jagir'' (autonomous principality), governed by an alternative family line of Maharaja Hari Singh. The taxation is said to have been heavy. The Muslims of Poonch had long campaigned for the principality to be absorbed into the Punjab province of British India. In 1938, a notable disturbance occurred for religious reasons, but a settlement was reached. During the Second World War, over 60,000 men from Poonch and Mirpur districts enrolled in the British Indian Army. After the war, they were discharged with arms, which is said to have alarmed the Maharaja. In June, Poonchis launched a 'No Tax' campaign. In July, the Maharaja ordered that all the soldiers in the region be disarmed. The absence of employment prospects coupled with high taxation drove the Poonchis to rebellion. The "gathering head of steam", states scholar Srinath Raghavan, was utilised by the local Muslim Conference led by Sardar Muhammad Ibrahim Khan

Sardar Muhammad Ibrahim Khan (22 April 1915 – 31 July 2003) was the key instigator of the 1947 Poonch Rebellion in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in British India and the later establishment of Azad Kashmir under Pakistani admi ...

(Sardar Ibrahim) to further their campaign for accession to Pakistan.

According to state government sources, the rebellious militias gathered in the Naoshera-Islamabad area, attacking the state troops and their supply trucks. A battalion of state troops was dispatched, which cleared the roads and dispersed the militias. By September, order was reestablished. The Muslim Conference sources, on the other hand, narrate that hundreds of people were killed in Bagh

Bagh ( fa, باغ, link=no, meaning "garden") may refer to:

Places India

* Bagh Caves in Madhya Pradesh, India

* Bagh, Dhar, a town in Madhya Pradesh, India

Iran

* Bagh, Ardabil, a village in Ardabil Province

* Bagh, Larestan, a village ...

during flag hoisting around 15 August and that the Maharaja unleashed a 'reign of terror' on 24 August. Local Muslims also told Richard Symonds, a British Quaker social worker, that the army fired on crowds, and burnt houses and villages indiscriminately. According to the Assistant British High Commissioner in Pakistan, H. S. Stephenson, "the Poonch affair... was greatly exaggerated".

Pakistan's preparations, Maharaja's manoeuvring

Scholar

Scholar Prem Shankar Jha

Prem Shankar Jha (born 22 December 1938) is an Indian economist, journalist and writer. He has served in the United Nations Development Programme, the World Bank and as the information advisor to the Prime Minister of India. As a journalist, he ...

states that the Maharaja had decided, as early as April 1947, that he would accede to India if it was not possible to stay independent. The rebellion in Poonch possibly unnerved the Maharaja. Accordingly, on 11 August, he dismissed his pro-Pakistan Prime Minister, Ram Chandra Kak, and appointed retired Major Janak Singh

Major General Janak Singh (surname Katoch) CIE, OBI, (7 August 1872 – 15 March 1972) was an officer of the Jammu and Kashmir State Forces in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. After retirement, he briefly served as the prime minister ...

in his place. On 25 August, he sent an invitation to Justice Mehr Chand Mahajan

Justice Mehr Chand Mahajan (1889–1967) was the third Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India. Prior to that he was the Prime Minister of the state of Jammu and Kashmir during the reign of Maharaja Hari Singh and played a key role in the ...

of the Punjab High Court to come as the Prime Minister. On the same day, the Muslim Conference wrote to the Pakistani Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan ( ur, ; 1 October 1895 – 16 October 1951), also referred to in Pakistan as ''Quaid-e-Millat'' () or ''Shaheed-e-Millat'' ( ur, lit=Martyr of the Nation, label=none, ), was a Pakistani statesman, lawyer, political theoris ...

warning him that "if, God forbid, the Pakistan Government or the Muslim League do not act, Kashmir might be lost to them". This set the ball rolling in Pakistan.

Liaquat Ali Khan sent a Punjab politician Mian Iftikharuddin

Mian Iftikharuddin (Punjabi, ur, میاں افتخارالدیں; 8 April 1907 – 6 June 1962) was a Pakistani politician, activist of the Indian National Congress, who later joined the All-India Muslim League and worked for the cause of Pakis ...

to explore the possibility of organising a revolt in Kashmir. Meanwhile, Pakistan cut off essential supplies to the state, such as petrol, sugar and salt. It also stopped trade in timber and other products, and suspended train services to Jammu. Iftikharuddin returned in mid-September to report that the National Conference held strong in the Kashmir Valley and ruled out the possibility of a revolt.

Meanwhile, Sardar Ibrahim had escaped to West Punjab, along with dozens of rebels, and established a base in

Meanwhile, Sardar Ibrahim had escaped to West Punjab, along with dozens of rebels, and established a base in Murree

Murree ( Punjabi, Urdu: مری) is a mountain resort city, located in the Galyat region of the Pir Panjal Range, within the Muree District of Punjab, Pakistan. It forms the outskirts of the Islamabad-Rawalpindi metropolitan area, and is about ...

. From there, the rebels attempted to acquire arms and ammunition for the rebellion and smuggle them into Kashmir. Colonel Akbar Khan, one of a handful of high-ranking officers in the Pakistani Army, with a keen interest in Kashmir, arrived in Murree, and got enmeshed in these efforts. He arranged 4,000 rifles for the rebellion by diverting them from the Army stores. He also wrote out a draft plan titled ''Armed Revolt inside Kashmir'' and gave it to Mian Iftikharuddin to be passed on to the Pakistan's Prime Minister.

On 12 September, the Prime Minister held a meeting with Mian Iftikharuddin, Colonel Akbar Khan and another Punjab politician Sardar Shaukat Hayat Khan

Major Shaukat Hayat Khan ( Punjabi, ; 24 September 1915 – 25 September 1998) was an influential politician, military officer, and Pakistan Movement activist who played a major role in the organising of the Muslim League in the British-controlle ...

. Hayat Khan had a separate plan, involving the Muslim League National Guard

The Muslim League National Guard, also called Muslim National Guard, was a quasi-military organization, associated All-India Muslim League that took part in the Pakistan Movement. It actively took part in the violence that ensued during the Parti ...

and the militant Pashtun tribes from the Frontier regions

The Frontier Regions (often abbreviated as FR) of Pakistan were a group of small administrative units in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), lying immediately to the east of the seven main tribal agencies and west of the settled distr ...

. The Prime Minister approved both the plans, and despatched Khurshid Anwar, the head of the Muslim League National Guard, to mobilise the Frontier tribes.

The Maharaja was increasingly driven to the wall with the rebellion in the western districts and the Pakistani blockade. He managed to persuade Justice Mahajan to accept the post of Prime Minister (but not to arrive for another month, for procedural reasons). He sent word to the Indian leaders through Mahajan that he was willing to accede to India but needed more time to implement political reforms. However, it was India's position that it would not accept accession from the Maharaja unless it had the people's support. The Indian Prime Minister

The Maharaja was increasingly driven to the wall with the rebellion in the western districts and the Pakistani blockade. He managed to persuade Justice Mahajan to accept the post of Prime Minister (but not to arrive for another month, for procedural reasons). He sent word to the Indian leaders through Mahajan that he was willing to accede to India but needed more time to implement political reforms. However, it was India's position that it would not accept accession from the Maharaja unless it had the people's support. The Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

demanded that Sheikh Abdullah should be released from prison and involved in the state's government. Accession could only be contemplated afterwards. Following further negotiations, Sheikh Abdullah was released on 29 September.

Nehru, foreseeing a number of disputes over princely states, formulated a policy that states

The policy was communicated to Liaquat Ali Khan on 1 October at a meeting of the Joint Defence Council. Khan's eyes are said to have "sparkled" at the proposal. However, he made no response.

Operations in Poonch and Mirpur

Armed rebellion started in the Poonch district at the beginning of October 1947. The fighting elements consisted of "bands of deserters from the State Army, serving soldiers of the Pakistan Army on leave, ex-servicemen, and other volunteers who had risen spontaneously." The first clash is said to have occurred at Thorar (nearRawalakot

Rawalakot ( ur, ) is the capital of Poonch district in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. It is located in the Pir Panjal Range.

History

Along with Pallandri, Rawalakot was the focal point of the 1955 Poonch uprising. It was led by the local Sudhans ...

) on 3–4 October 1947.Regimental History Cell, ''History of the Azad Kashmir Regiment, Volume 1 (1947–1949)'', Azad Kashmir Regimental Centre, NLC Printers, Rawalpindi,1997

The rebels quickly gained control of almost the entire Poonch district. The State Forces garrison at the Poonch city came under heavy siege.

In the Kotli tehsil

Kotli ( ur}) is a city in Kotli District of Azad Kashmir in Pakistan. It lies on the Poonch River, and the river contains several notable waterfalls including the Lala Waterfall near the town of Kotli and the Gulpur Waterfalls at the village of ...

of the Mirpur district, border posts at Saligram and Owen Pattan

Holar (or Hollar) is a city in the Sehnsa tehsil of Kotli District, of Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. It has a crossing on the Jhelum river, which used to be called Owen Pattan in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, but now called Holar bridge. T ...

on the Jhelum river were captured by rebels around 8 October. Sehnsa

Sehnsa Tehsil is a large Tehsil in Pakistan Administered Azad Kashmir which lies on the west of Gulpur on the Kotli

Kotli ( ur}) is a city in Kotli District of Azad Kashmir in Pakistan. It lies on the Poonch River, and the river contains sev ...

and Throchi were lost after some fighting. State Force records reveal that Muslim officers sent with reinforcements sided with the rebels and murdered the fellow state troops.

Radio communications between the fighting units were operated by the Pakistan Army. Even though the Indian Navy intercepted the communications, lacking intelligence in Jammu and Kashmir, it was unable to determine immediately where the fighting was taking place.

Accession of Kashmir

Following the rebellions in the Poonch and Mirpur areaLamb, Alastair (1997), ''Incomplete partition: the genesis of the Kashmir dispute 1947–1948'', Roxford, and the Pakistan-backedPashtun

Pashtuns (, , ; ps, پښتانه, ), also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, are an Iranian ethnic group who are native to the geographic region of Pashtunistan in the present-day countries of Afghanistan and Pakistan. They were historically re ...

tribal intervention from the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Maharaja asked for Indian military assistance. India set the condition that Kashmir must accede to India for it to receive assistance. The Maharaja complied, and the Government of India

The Government of India (ISO: ; often abbreviated as GoI), known as the Union Government or Central Government but often simply as the Centre, is the national government of the Republic of India, a federal democracy located in South Asia, c ...

recognised the accession of the princely state to India. Indian troops were sent to the state to defend it. The Jammu & Kashmir National Conference

The Jammu & Kashmir National Conference (JKNC) is a regional political party in the Indian union territories of Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh. Founded as the ''All Jammu and Kashmir Muslim Conference'' by Sheikh Abdullah and Chaudhry Ghulam A ...

volunteers aided the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

in its campaign to drive out the Pathan invaders.

Pakistan refused to recognise the accession of Kashmir to India, claiming that it was obtained by "fraud and violence." Governor General Mohammad Ali Jinnah

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mono ...

ordered his Army Chief General Douglas Gracey

General Sir Douglas David Gracey & Bar (3 September 1894 – 5 June 1964) was a British Indian Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars. He also fought in French Indochina and was the second Commander-in-Chief of the P ...

to move Pakistani troops to Kashmir at once. However, the Indian and Pakistani forces were still under a joint command, and Field Marshal Auchinleck

Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Army commander during the Second World War. He was a career soldier who spent much of his military career in India, w ...

prevailed upon him to withdraw the order. With its accession to India, Kashmir became legally Indian territory, and the British officers could not a play any role in an inter-Dominion war. The Pakistan army made available arms, ammunition and supplies to the rebel forces who were dubbed the 'Azad Army'. Pakistani army officers 'conveniently' on leave and the former officers of the Indian National Army

The Indian National Army (INA; ''Azad Hind Fauj'' ; 'Free Indian Army') was a collaborationist armed force formed by Indian collaborators and Imperial Japan on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II. Its aim was to secure In ...

were recruited to command the forces.

In May 1948, the Pakistani army officially entered the conflict, in theory to defend the Pakistan borders, but it made

plans to push towards Jammu and cut the lines of communications of the Indian forces in the Mehndar Valley.

In

In May 1948, the Pakistani army officially entered the conflict, in theory to defend the Pakistan borders, but it made

plans to push towards Jammu and cut the lines of communications of the Indian forces in the Mehndar Valley.

In Gilgit

Gilgit (; Shina: ; ur, ) is the capital city of Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan. The city is located in a broad valley near the confluence of the Gilgit River and the Hunza River. It is a major tourist destination in Pakistan, serving as a h ...

, the force of Gilgit Scouts

The Gilgit Scouts constituted a paramilitary force of the Gilgit Agency in northern Jammu and Kashmir. They were raised by the government of British India in 1913, on behalf of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, to police the northern front ...

under the command of a British officer Major William Brown mutinied and overthrew the governor Ghansara Singh. Brown prevailed on the forces to declare accession to Pakistan. They are also believed to have received assistance from the Chitral Scouts

The Chitral Scouts (''CS'') ( ur, چترال سکاوٹس), also known as Chitral Levies, originally raised in 1903 as the militia of the princely state of Chitral, is now part of the Frontier Corps Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (North) of Pakistan. They are ...

and the Bodyguard

A bodyguard (or close protection officer/operative) is a type of security guard, government law enforcement officer, or servicemember who protects a person or a group of people — usually witnesses, high-ranking public officials or officers, w ...

of the state of Chitral, one of the princely states of Pakistan

The princely states of Pakistan ( ur, ; sd, پاڪستان جون نوابي رياستون) were princely states of the British Indian Empire which acceded to the new Dominion of Pakistan between 1947 and 1948, following the partition of Br ...

, which had acceded to Pakistan on 6 October 1947.

Stages of the war

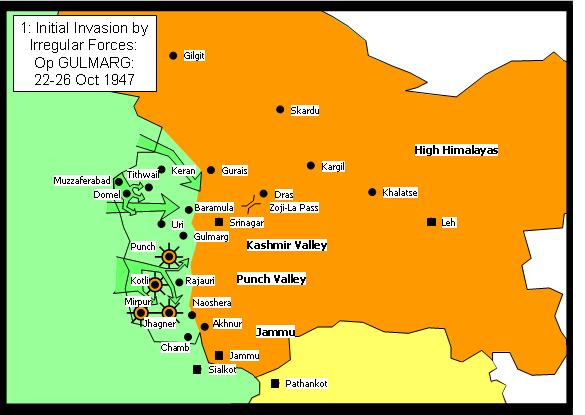

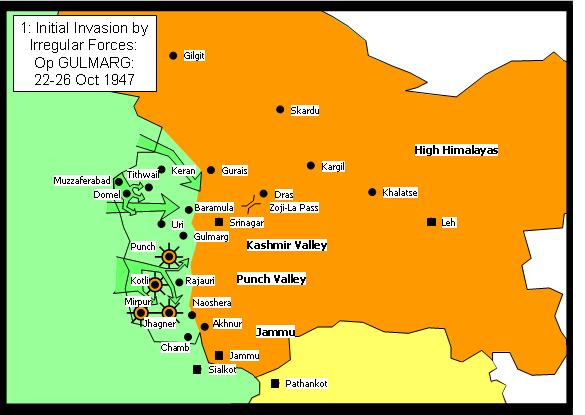

Initial invasion

On 22 October the Pashtun tribal attack was launched in the Muzaffarabad sector. The state forces stationed in the border regions around

On 22 October the Pashtun tribal attack was launched in the Muzaffarabad sector. The state forces stationed in the border regions around Muzaffarabad

Muzaffarabad (; ur, ) is the capital and largest city of Azad Kashmir, and the 60th largest in Pakistan.

The city is located in Muzaffarabad District, near the confluence of the Jhelum and Neelum rivers. The district is bounded by the Pak ...

and Domel were quickly defeated by tribal forces (Muslim state forces mutinied and joined them) and the way to the capital was open. Among the raiders, there were many active Pakistani Army soldiers disguised as tribals. They were also provided logistical help by the Pakistan Army. Rather than advancing toward Srinagar before state forces could regroup or be reinforced, the invading forces remained in the captured cities in the border region engaging in looting and other crimes against their inhabitants. In the Poonch valley, the state forces retreated into towns where they were besieged.

Records indicate that the Pakistani tribals beheaded many Hindu and Sikh civilians in Jammu and Kashmir.

Indian operation in the Kashmir Valley

After the accession, India airlifted troops and equipment to Srinagar under the command of Lt. Col.

After the accession, India airlifted troops and equipment to Srinagar under the command of Lt. Col. Dewan Ranjit Rai

Lieutenant Colonel Dewan Ranjit Rai, MVC (1913 - 1947) was an Indian Army officer who played a key role during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947. As the Commanding Officer of the 1st battalion, The Sikh Regiment (1 Sikh), he was the first recip ...

, where they reinforced the princely state forces, established a defence perimeter and defeated the tribal forces on the outskirts of the city. Initial defense operations included the notable defense of Badgam

Budgam (), known as Badgom (; ) in Kashmiri, is a town in Budgam district in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir, India. In the 2001 census, it was recorded as having a notified area committee,This gives the population of Budgam adgamN.A ...

holding both the capital and airfield overnight against extreme odds. The successful defence included an outflanking manoeuvre by Indian armoured cars

Armored (or armoured) car or vehicle may refer to:

Wheeled armored vehicles

* Armoured fighting vehicle, any armed combat vehicle protected by armor

** Armored car (military), a military wheeled armored vehicle

* Armored car (valuables), an arm ...

during the Battle of Shalateng. The defeated tribal forces were pursued as far as Baramulla

Baramulla (), also known as Varmul () in Kashmiri, is a town and a municipality in the Baramulla district in the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. It is also the administrative headquarters of the Baramulla district. It is on the ...

and Uri Uri may refer to:

Places

* Canton of Uri, a canton in Switzerland

* Úri, a village and commune in Hungary

* Uri, Iran, a village in East Azerbaijan Province

* Uri, Jammu and Kashmir, a town in India

* Uri (island), an island off Malakula Islan ...

and these towns, too, were recaptured.

In the Poonch valley, tribal forces continued to besiege state forces.

In Gilgit

Gilgit (; Shina: ; ur, ) is the capital city of Gilgit–Baltistan, Pakistan. The city is located in a broad valley near the confluence of the Gilgit River and the Hunza River. It is a major tourist destination in Pakistan, serving as a h ...

, the state paramilitary forces, called the Gilgit Scouts

The Gilgit Scouts constituted a paramilitary force of the Gilgit Agency in northern Jammu and Kashmir. They were raised by the government of British India in 1913, on behalf of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, to police the northern front ...

, joined the invading tribal forces, who thereby obtained control of this northern region of the state. The tribal forces were also joined by troops from Chitral, whose ruler, Muzaffar ul-Mulk

His Highness Muzaffar ul-Mulk (6 October 1901 – 12 January 1949) was the Mehtar of Chitral who reigned from 1943 to 1949. He took the important decision of Chitrals accession to Pakistan in 1947. He dispatched his army into Gilgit in August ...

the Mehtar of Chitral, had acceded to Pakistan.

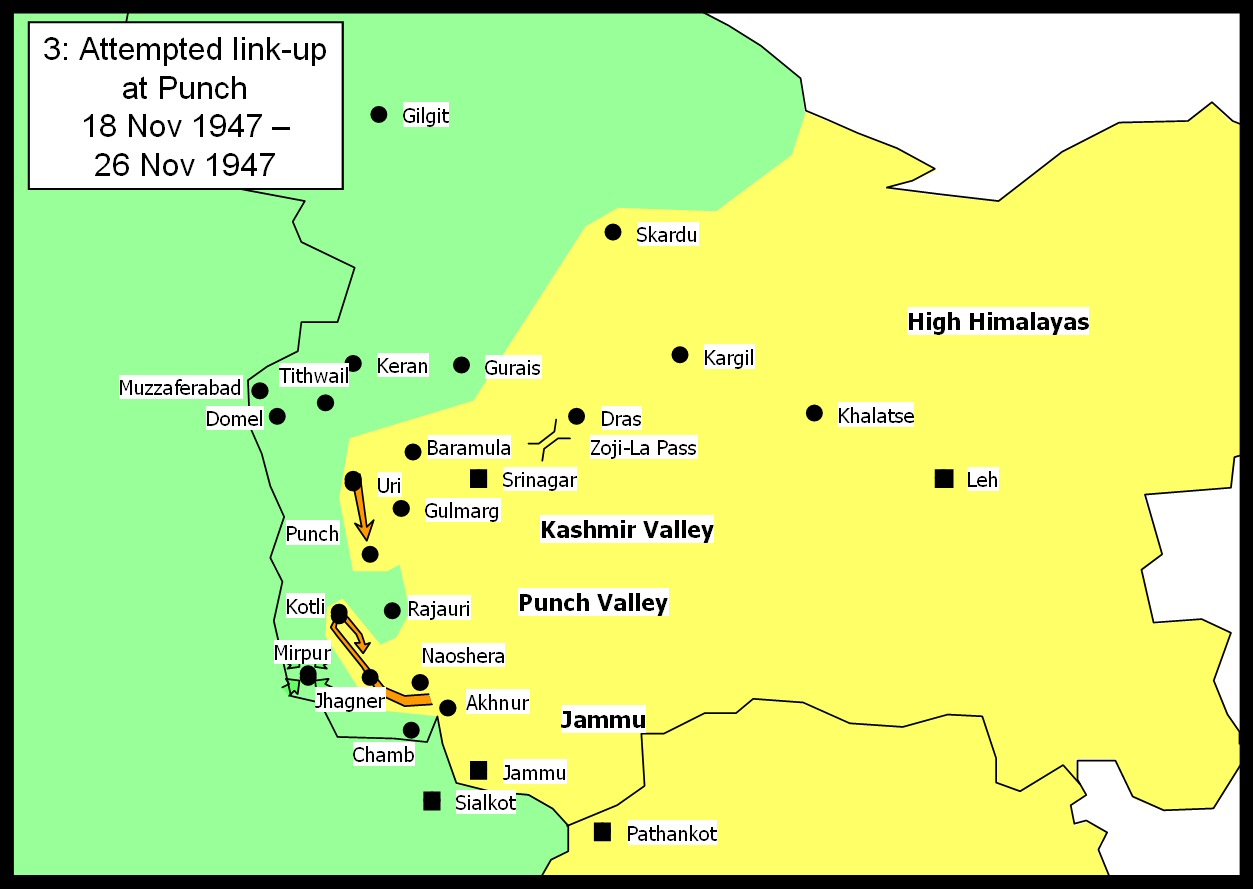

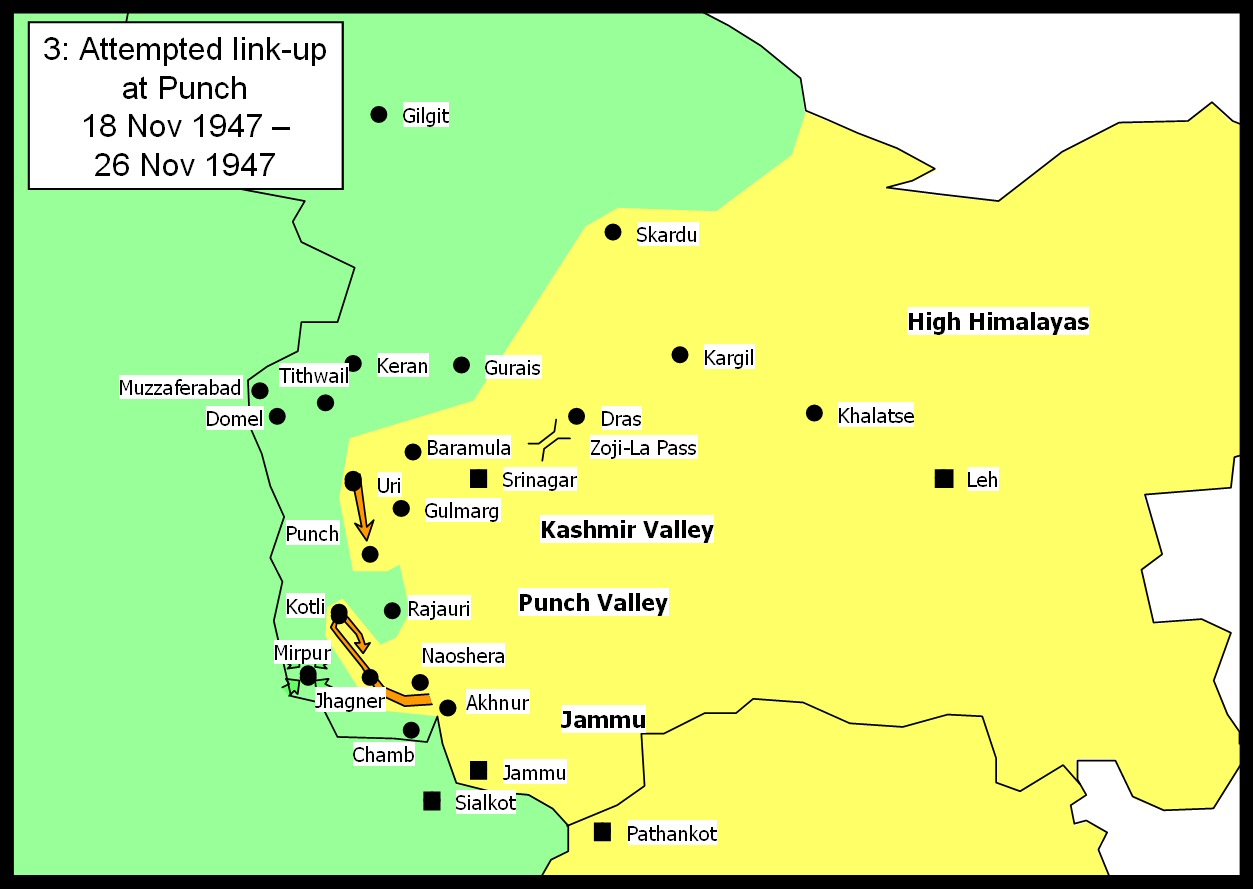

Attempted link-up at Poonch and fall of Mirpur

Indian forces ceased pursuit of tribal forces after recapturing Uri and Baramula, and sent a

Indian forces ceased pursuit of tribal forces after recapturing Uri and Baramula, and sent a relief column

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterize ...

southwards, in an attempt to relieve Poonch. Although the relief column eventually reached Poonch, the siege could not be lifted. A second relief column reached Kotli, and evacuated the garrisons of that town and others but were forced to abandon it being too weak to defend it. Meanwhile, Mirpur was captured by the tribal forces on 25 November 1947 with the help of Pakistan's PAVO Cavalry

The 11th Cavalry (Frontier Force), is an armoured regiment of the Pakistan Army. It was previously known as the 11th Prince Albert Victor's Own Cavalry and was a regular cavalry regiment of the old British Indian Army. It was formed in 1921 by th ...

. This led to the 1947 Mirpur massacre where Hindu women were reportedly abducted by tribal forces and taken into Pakistan. They were sold in the brothels of Rawalpindi. Around 400 women jumped into wells in Mirpur committing suicide to escape from being abducted.

Fall of Jhanger and attacks on Naoshera and Uri

The tribal forces attacked and captured Jhanger. They then attacked Naoshera unsuccessfully, and made a series of unsuccessful attacks on

The tribal forces attacked and captured Jhanger. They then attacked Naoshera unsuccessfully, and made a series of unsuccessful attacks on Uri Uri may refer to:

Places

* Canton of Uri, a canton in Switzerland

* Úri, a village and commune in Hungary

* Uri, Iran, a village in East Azerbaijan Province

* Uri, Jammu and Kashmir, a town in India

* Uri (island), an island off Malakula Islan ...

. In the south a minor Indian attack secured Chamb

The Chamb (german: Chamb; cs, Kouba) is a river in the Czech Republic and in Germany. It is a right tributary of the Regen (river), Regen.

The Chamb begins south of the Czech village of Kdyně, and flows some westward, crossing into Germany a ...

. By this stage of the war the front line began to stabilise as more Indian troops became available.

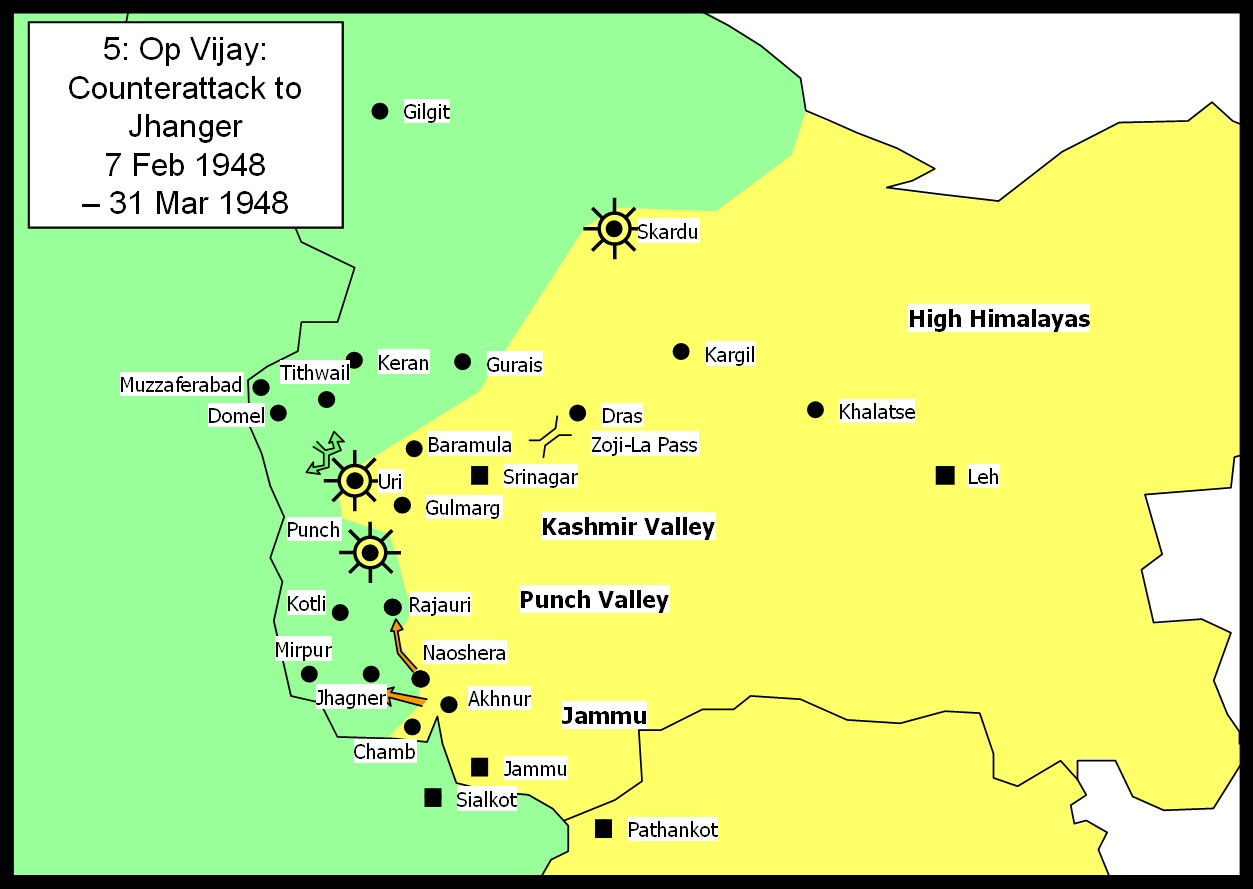

Operation Vijay: counterattack to Jhanger

The Indian forces launched a counterattack in the south recapturing Jhanger and Rajauri. In the Kashmir Valley the tribal forces continued attacking the Urigarrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

. In the north, Skardu

, nickname =

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Gilgit Baltistan#Pakistan

, pushpin_label_position ...

was brought under siege by the Gilgit Scouts.

Indian spring offensive

The Indians held onto Jhanger against numerous counterattacks, who were increasingly supported by regular Pakistani Forces. In the Kashmir Valley the Indians attacked, recapturing Tithwail. The Gilgit scouts made good progress in the High Himalayas sector, infiltrating troops to bringLeh

Leh () ( lbj, ) is the joint capital and largest city of Ladakh, a union territory of India. Leh, located in the Leh district, was also the historical capital of the Kingdom of Ladakh, the seat of which was in the Leh Palace, the former res ...

under siege, capturing Kargil

Kargil ( lbj, ) is a city and a joint capital of the union territory of Ladakh, India. It is also the headquarters of the Kargil district. It is the second-largest city in Ladakh after Leh. Kargil is located to the east of Srinagar in Jam ...

and defeating a relief column heading for Skardu.

Operations Gulab and Eraze

The Indians continued to attack in the Kashmir Valley sector driving north to capture Keran and Gurais (Operation Eraze

Operation Eraze is the codename of the assault and capture of Gurais in northern Kashmir by the Indian Army during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947.

History

Gurais is an important communication centre where the route from Srinagar comes north to ...

). They also repelled a counterattack aimed at Tithwal. In the Jammu region, the forces besieged in Poonch broke out and temporarily linked up with the outside world again. The Kashmir State army was able to defend Skardu from the Gilgit Scouts impeding their advance down the Indus valley towards Leh. In August the Chitral Scouts

The Chitral Scouts (''CS'') ( ur, چترال سکاوٹس), also known as Chitral Levies, originally raised in 1903 as the militia of the princely state of Chitral, is now part of the Frontier Corps Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (North) of Pakistan. They are ...

and Chitral Bodyguard

Chitral Bodyguard or informally the Mehtar's Bodyguard, was a military force under the direct command of the Mehtar of the princely state of Chitral.

History

Upon British occupation of Chitral following the Chitral Expedition of 1895, the Briti ...

under Mata ul-Mulk besieged Skardu and with the help of artillery were able to take Skardu. This freed the Gilgit Scouts to push further into Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

.

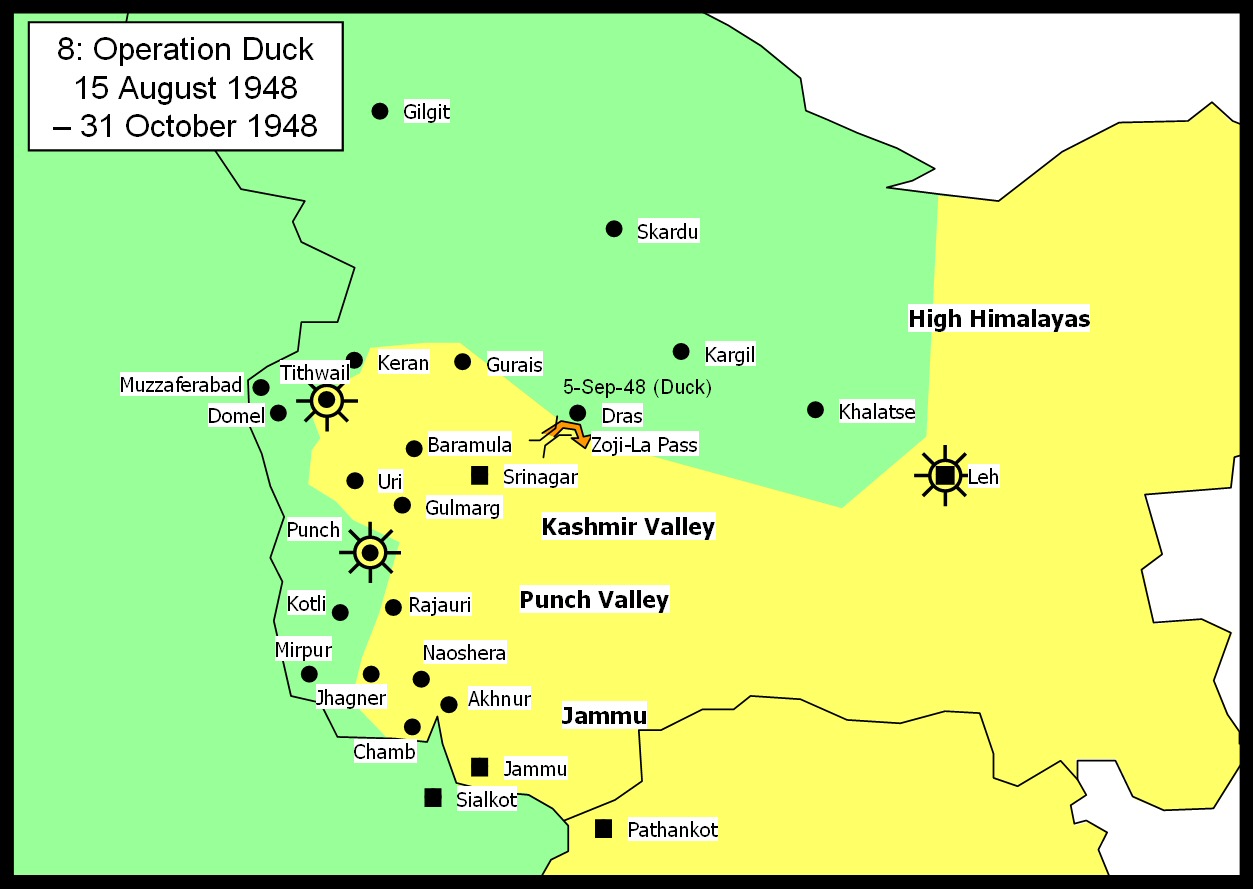

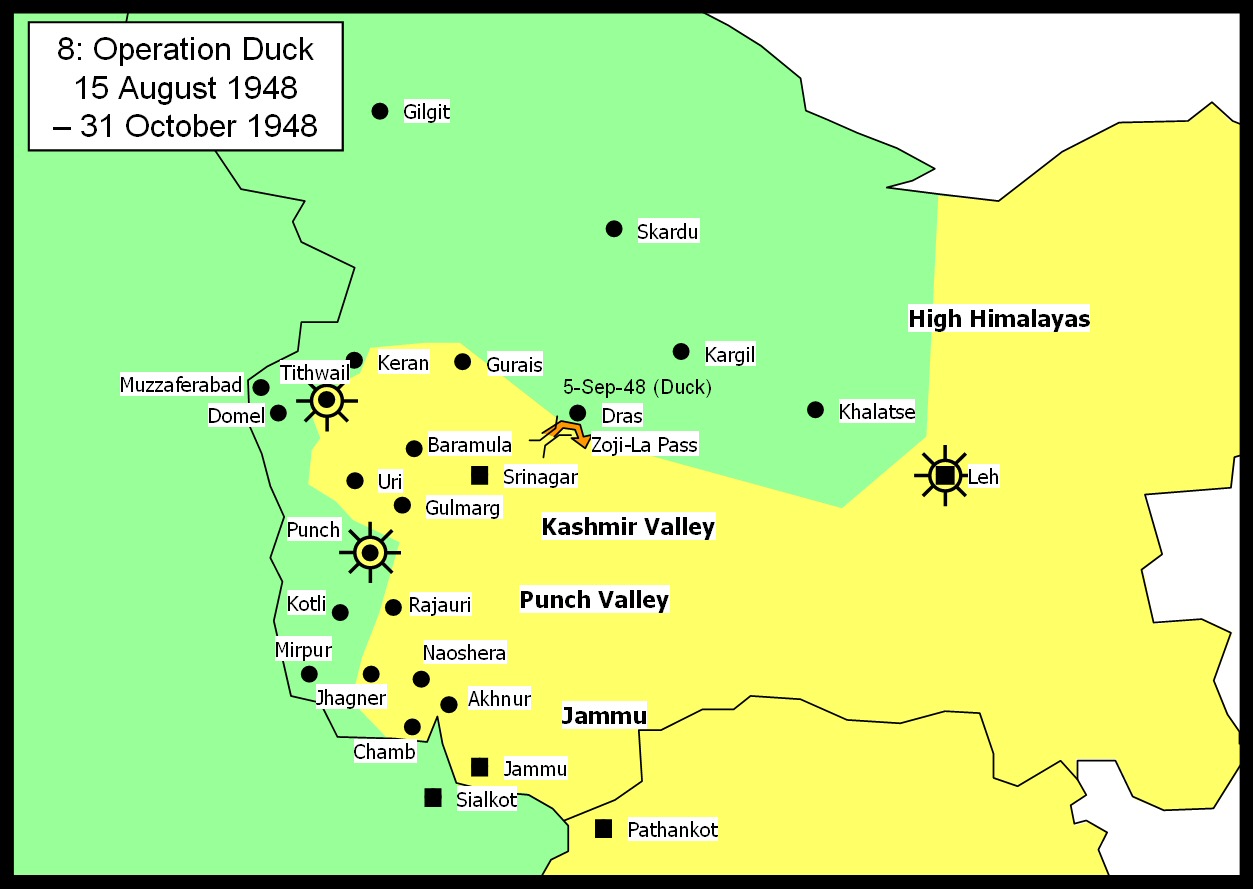

Operation Bison

During this time the front began to settle down. The siege of Poonch continued. An unsuccessful attack was launched by 77 Parachute Brigade (Brig Atal) to captureZoji La

Zoji La (sometimes Zojila Pass) is a high mountain pass in the Himalayas. It is in the Indian Union territory of Ladakh, Kargil district, Kashmir. Located in the Drass, the pass connects the Kashmir Valley to its west, with the Drass ...

pass. Operation Duck, the earlier epithet for this assault, was renamed as Operation Bison by Cariappa. M5 Stuart light tanks of 7 Cavalry were moved in dismantled conditions through Srinagar and winched across bridges while two field companies of the Madras Sappers

Chennai (, ), formerly known as Madras ( the official name until 1996), is the capital city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost Indian state. The largest city of the state in area and population, Chennai is located on the Coromandel Coast of th ...

converted the mule track across Zoji La into a jeep track. The surprise attack on 1 November by the brigade with armour supported by two regiments of 25-pounders and a regiment of 3.7-inch guns, forced the pass and pushed the tribal and Pakistani forces back to Matayan

For Hinduism in India, the Matayan is the sole authority to administer the Muthappan temple, found in the Kannur district of Kerala state, south India.

See also

* Sree Muthappan

*Muthappan temple

Parassinikadavu Muthappan temple is a temple, ...

and later Dras. The brigade linked up on 24 November at Kargil

Kargil ( lbj, ) is a city and a joint capital of the union territory of Ladakh, India. It is also the headquarters of the Kargil district. It is the second-largest city in Ladakh after Leh. Kargil is located to the east of Srinagar in Jam ...

with Indian troops advancing from Leh

Leh () ( lbj, ) is the joint capital and largest city of Ladakh, a union territory of India. Leh, located in the Leh district, was also the historical capital of the Kingdom of Ladakh, the seat of which was in the Leh Palace, the former res ...

while their opponents eventually withdrew northwards toward Skardu

, nickname =

, motto =

, image_skyline =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Gilgit Baltistan#Pakistan

, pushpin_label_position ...

. The Pakistani attacked the Skardu on 10 February 1948 which was repulsed by the Indian soldiers. Thereafter, the Skardu Garrison was subjected to continuous attacks by the Pakistan Army

The Pakistan Army (, ) is the Army, land service branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The roots of its modern existence trace back to the British Indian Army that ceased to exist following the partition of India, Partition of British India, wh ...

for the next three months and each time, their attack was repulsed by the Colonel Sher Jung Thapa

Brigadier Sher Jung Thapa MVC (15 April 1907 – 25 February 1999) was a military officer of the Jammu and Kashmir State Forces and later the Indian Army. Revered as ''the Hero of Skardu'', he was a recipient of the Indian Army's second highes ...

and his men. Thapa held the Skardu with hardly 250 men for whole six long months without any reinforcement and replenishment. On 14 August Thapa had to surrender Skardu to the Pakistani Army and raiders after a year long siege.

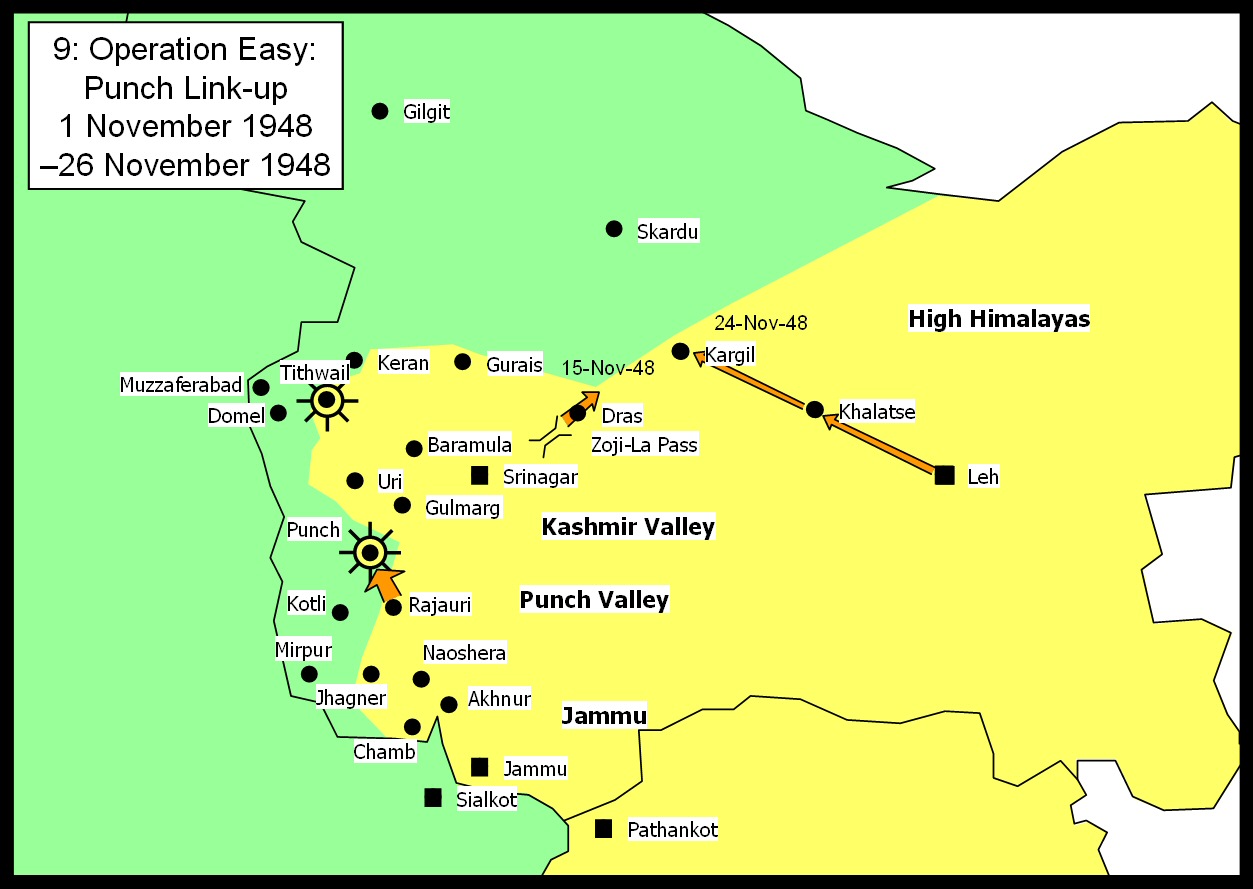

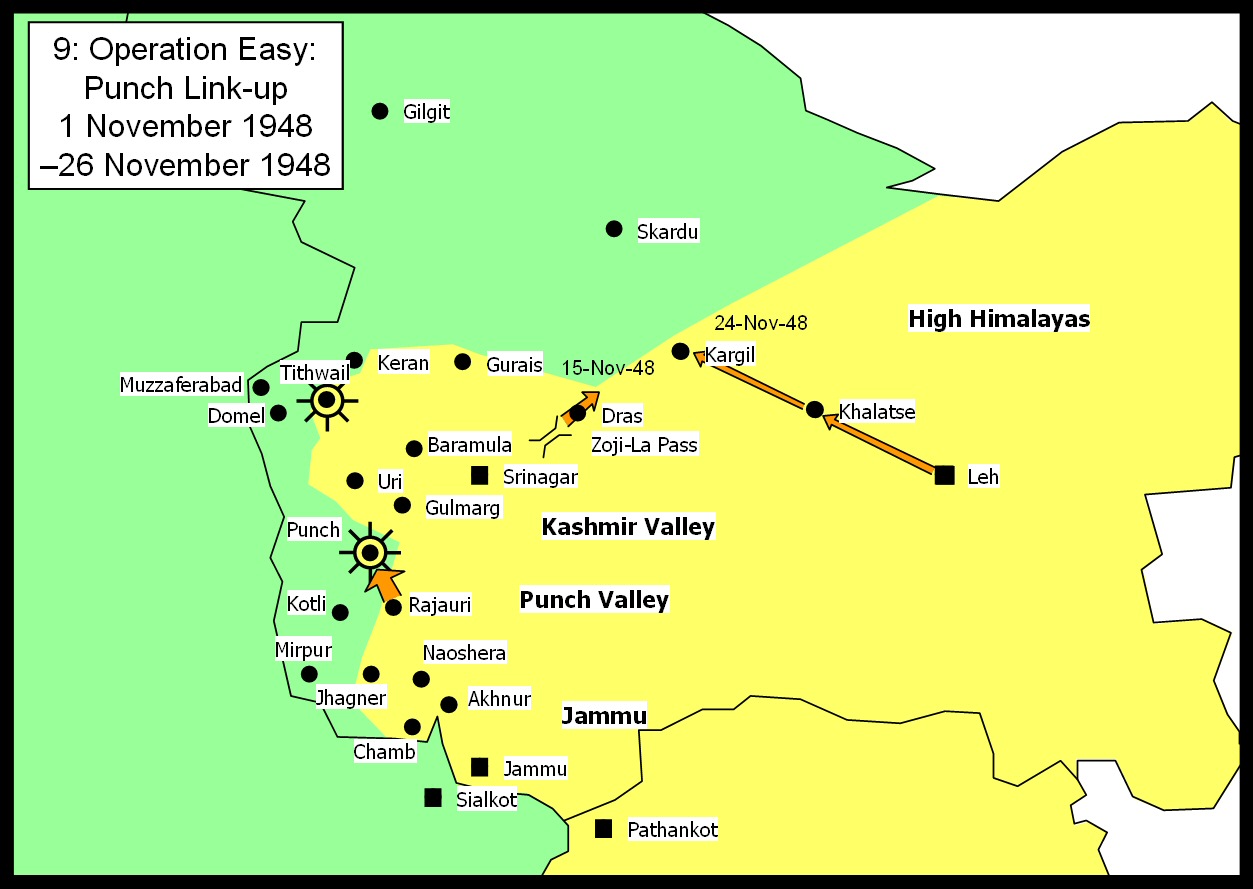

Operation Easy; Poonch link-up

The Indians now started to get the upper hand in all sectors.Poonch Poonch, sometimes also spelt Punchh, may refer to:

* Historical Poonch District, a district in the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in British India, split in 1947 between:

** Poonch district, India

** Poonch Division, in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan, ...

was finally relieved after a siege of over a year. The Gilgit forces in the High Himalayas, who had previously made good progress, were finally defeated. The Indians pursued as far as Kargil before being forced to halt due to supply problems. The Zoji La

Zoji La (sometimes Zojila Pass) is a high mountain pass in the Himalayas. It is in the Indian Union territory of Ladakh, Kargil district, Kashmir. Located in the Drass, the pass connects the Kashmir Valley to its west, with the Drass ...

pass was forced by using tanks (which had not been thought possible at that altitude) and Dras was recaptured.

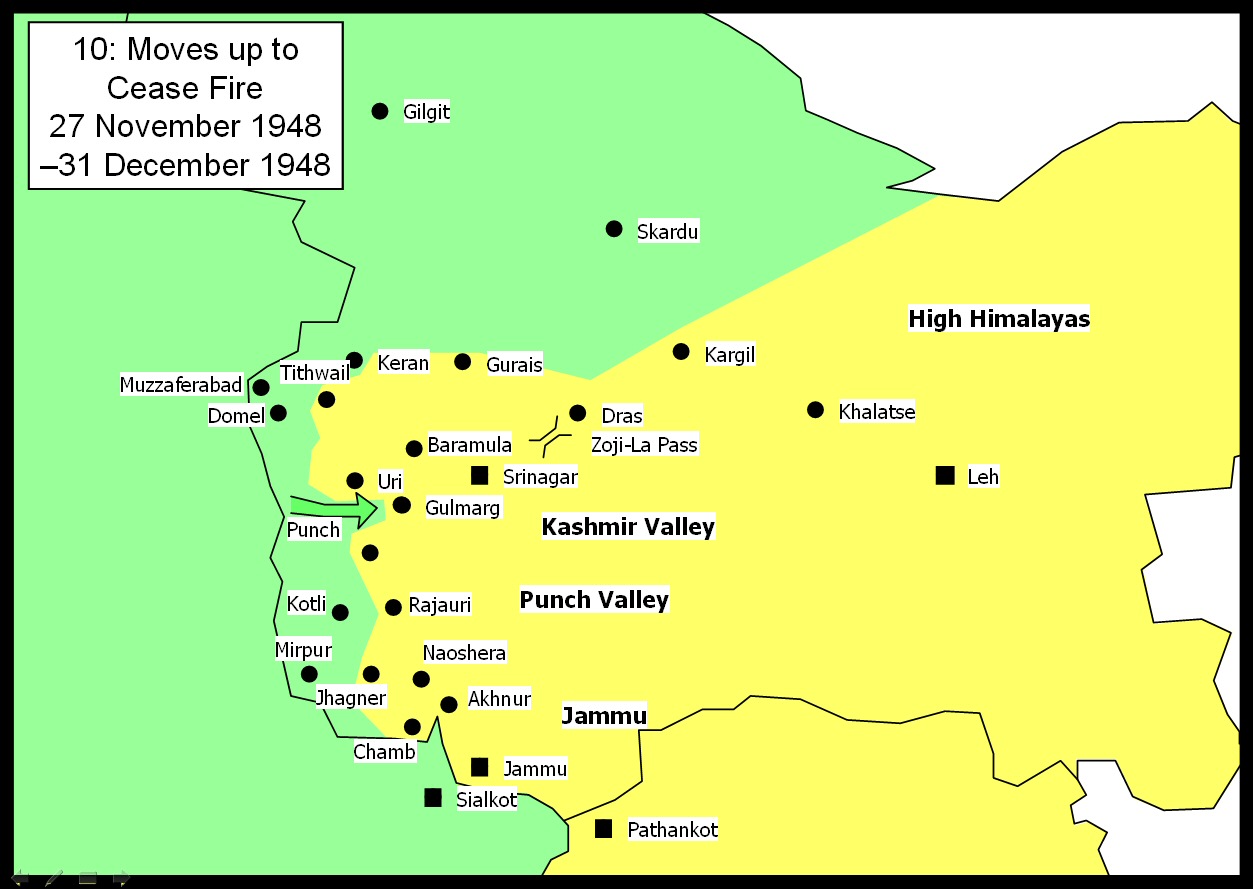

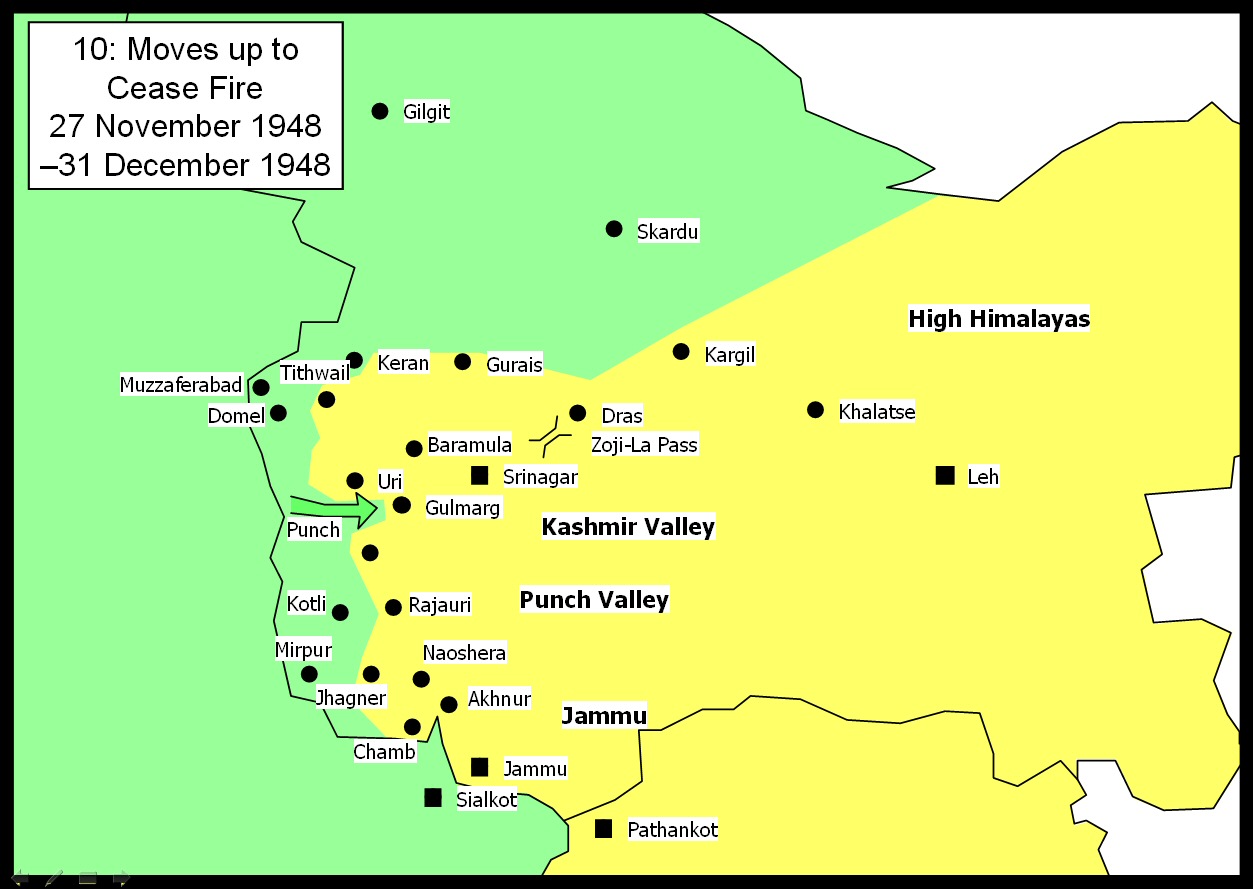

Moves up to cease-fire

After protracted negotiations, both countries agreed to a cease-fire. The terms of the cease-fire, laid out in a UN Commission resolution on 13 August 1948, were adopted by the commission on 5 January 1949. This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimal forces within the state to preserve law and order. Upon compliance with these conditions, a

After protracted negotiations, both countries agreed to a cease-fire. The terms of the cease-fire, laid out in a UN Commission resolution on 13 August 1948, were adopted by the commission on 5 January 1949. This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimal forces within the state to preserve law and order. Upon compliance with these conditions, a plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

was to be held to determine the future of the territory.

Result

Indian losses in the war totalled 1,104 killed and 3,154 wounded; Pakistani, about 6,000 killed and 14,000 wounded. India gained control of about two-thirds of Kashmir; Pakistan, the remainder. Neutral assessments stateIndia

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

emerged victorious as it successfully defended most of the contested territory, including the Kashmir valley

The Kashmir Valley, also known as the ''Vale of Kashmir'', is an intermontane valley concentrated in the Kashmir Division of the Indian- union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The valley is bounded on the southwest by the Pir Panjal Range and ...

, Jammu

Jammu is the winter capital of the Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), Jammu and Kashmir. It is the headquarters and the largest city in Jammu district of the union territory. Lying on the banks of the river Tawi Ri ...

, and Ladakh

Ladakh () is a region administered by India as a union territory which constitutes a part of the larger Kashmir region and has been the subject of dispute between India, Pakistan, and China since 1947. (subscription required) Quote: "Jammu and ...

.

Military awards

Battle honours

After the war, a total of number of 11battle honour

A battle honour is an award of a right by a government or sovereign to a military unit to emblazon the name of a battle or operation on its flags ("colours"), uniforms or other accessories where ornamentation is possible.

In European military t ...

s and one theatre honour

A battle honour is an award of a right by a government or sovereign to a military unit to emblazon the name of a battle or operation on its flags ("colours"), uniforms or other accessories where ornamentation is possible.

In European military t ...

were awarded to units of the Indian Army, the notable amongst which are:

* Jammu and Kashmir 1947–48 (theatre honour)

* Gurais

* Kargil

* Naoshera

* Punch

* Rajouri

* Srinagar

* Tithwal

* Zoji La

Gallantry awards

For bravery, a number of soldiers and officers were awarded the highest gallantry award of their respective countries. Following is a list of the recipients of the Indian awardParam Vir Chakra

The Param Vir Chakra (PVC) is India's highest military decoration, awarded for displaying distinguished acts of valour during wartime. Param Vir Chakra translates as the "Wheel of the Ultimate Brave", and the award is granted for "most conspicu ...

, and the Pakistani award Nishan-E-Haider

Nishan-e-Haider (NH; ), is the highest military gallantry award of Pakistan. The Nishan-e-Haider is awarded posthumously and only to members of the Pakistan Armed Forces. It recognises the highest acts of extraordinary bravery in the face of ...

:

;India

* Major Som Nath Sharma

Major Somnath Sharma, PVC (31 January 1923 – 3 November 1947), was an officer of the Indian Army, and the first recipient of the Param Vir Chakra (PVC), India's highest military decoration, which he was awarded posthumously.

Sharma was comm ...

(Posthumous)

* Lance Naik Karam Singh

Subedar and Honorary Captain Karam Singh PVC, MM (15 September 1915 – 20 January 1993), an Indian soldier, was a recipient of the Param Vir Chakra (PVC), India's highest award for gallantry. Singh joined the army in 1941, and took pa ...

* Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

Rama Raghoba Rane

Major Rama Raghoba Rane, Param Vir Chakra, PVC (26 June 1918 – 11 July 1994) was an officer in the Indian Army. He was the first living recipient of the Param Vir Chakra along with Karam Singh, India's highest military decoration.

Born ...

* Naik Jadu Nath Singh

Jadunath Singh (1916 –1948) was an Indian Army soldier who was Wiktionary:posthumously, posthumously awarded the Param Vir Chakra, India's highest military decoration for his actions in an engagement during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 ...

(Posthumous)

* Company Havildar Major

Havildar or havaldar ( Hindustani: or (Devanagari), (Perso-Arabic)) is a rank in the Indian, Pakistani and Nepalese armies, equivalent to sergeant. It is not used in cavalry units, where the equivalent is daffadar.

Like a British sergeant, ...

Piru Singh Shekhawat

Havildar, Company Havildar Major Piru Singh Shekhawat (20 May 1918 – 18 July 1948) was an Indian Army non-commissioned officer, awarded the Param Vir Chakra (PVC), India's highest military decoration 3245.

Singh enrolled in the British Ind ...

(Posthumous)

;Pakistan

* Captain Muhammad Sarwar

See also

*Siege of Skardu

The siege of Skardu was a prolonged military blockade carried out by the Gilgit Scouts, Chitral Scouts and Chitral State Bodyguards, acting in coordination against Jammu and Kashmir State Forces and the Indian Army in the town of Skardu, during ...

* Rann of Kuch War

* Battle of Badgam

* Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 or the Second Kashmir War was a culmination of skirmishes that took place between April 1965 and September 1965 between Pakistan and India. The conflict began following Pakistan's Operation Gibraltar, which was d ...

* Indo-Pakistani wars and conflicts

Since the Partition of India, Partition of British India in 1947 and subsequent creation of the dominions of Dominion of India, India and Dominion of Pakistan, Pakistan, the two countries have been involved in a number of wars, conflicts, and m ...

* Kargil War

The Kargil War, also known as the Kargil conflict, was fought between India and Pakistan from May to July 1999 in the Kargil district of Jammu and Kashmir and elsewhere along the Line of Control (LoC). In India, the conflict is also referr ...

* Brigadier Mohammad Usman – Mahavir Chakra

* Siachen war

* Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tib ...

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * ** * * * * * ** * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

;Major sources: * . ''Operations in Jammu and Kashmir 1947–1948''. (1987). Thomson Press (India) Limited, New Delhi. This is the Indian Official History. * . ''Kashmir: A Disputed Legacy, 1846–1990''. (1991). Roxford Books. . * ''The Indian Army After Independence''. (1993). Lancer International, * ''Slender Was The Thread: The Kashmir confrontation 1947–1948.'' (1969). Orient Longmans Ltd, New Delhi. * ''Without Baggage: A personal account of the Jammu and Kashmir Operations 1947–1949''. (1987). Natraj Publishers Dehradun. . ;Other sources: * . ''Thunder over Kashmir''. (1955). Orient Longman Ltd. Hyderabad * . ''Battle of Zoji La''. (1962). Military Digest, New Delhi. * . ''The Indian Armour: History Of The Indian Armoured Corps 1941–1971''. (1987). Vision Books Private Limited, New Delhi, . * . ''History of Jammu and Kashmir Rifles (1820–1956)''. (1990). Lancer International New Delhi, . * Ayub, Muhammad (2005). An army, Its Role and Rule: A History of the Pakistan Army from Independence to Kargil, 1947–1999. RoseDog Books. .External links

*Partition and Indo Pak War of 1947–48

Indian Army, archived 5 April 2011. {{DEFAULTSORT:Indo-Pakistani War Of 1947 1947 in India 1948 in India 1949 in India Conflicts in 1947 Conflicts in 1948 Conflicts in 1949 Government of Liaquat Ali Khan History of Azad Kashmir History of Pakistan Indo-Pakistani wars

1947

It was the first year of the Cold War, which would last until 1991, ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Events

January

* January–February – Winter of 1946–47 in the United Kingdom: The worst snowfall in the country in ...

Military history of Pakistan

Nehru administration

Wars involving India