Islamic science on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the

The Islamic era began in 622. Islamic armies eventually conquered

The Islamic era began in 622. Islamic armies eventually conquered  Islamic science survived the initial Christian reconquest of Spain, including the fall of

Islamic science survived the initial Christian reconquest of Spain, including the fall of

Astronomy became a major discipline within Islamic science. Astronomers devoted effort both towards understanding the nature of the cosmos and to practical purposes. One application involved determining the ''Qibla'', the direction to face during prayer. Another was

Astronomy became a major discipline within Islamic science. Astronomers devoted effort both towards understanding the nature of the cosmos and to practical purposes. One application involved determining the ''Qibla'', the direction to face during prayer. Another was

The study of the natural world extended to a detailed examination of plants. The work done proved directly useful in the unprecedented growth of

The study of the natural world extended to a detailed examination of plants. The work done proved directly useful in the unprecedented growth of

The spread of Islam across Western Asia and North Africa encouraged an unprecedented growth in trade and travel by land and sea as far away as Southeast Asia, China, much of Africa, Scandinavia and even Iceland. Geographers worked to compile increasingly accurate maps of the known world, starting from many existing but fragmentary sources.

The spread of Islam across Western Asia and North Africa encouraged an unprecedented growth in trade and travel by land and sea as far away as Southeast Asia, China, much of Africa, Scandinavia and even Iceland. Geographers worked to compile increasingly accurate maps of the known world, starting from many existing but fragmentary sources.

File:TabulaRogeriana upside-down.jpg, Modern copy of al-Idrisi's 1154 '' Tabula Rogeriana'', upside-down, north at top

Islamic mathematicians gathered, organised and clarified the mathematics they inherited from ancient Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia and Persia, and went on to make innovations of their own. Islamic mathematics covered

Islamic mathematicians gathered, organised and clarified the mathematics they inherited from ancient Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia and Persia, and went on to make innovations of their own. Islamic mathematics covered

Islamic society paid careful attention to medicine, following a ''

Islamic society paid careful attention to medicine, following a ''

Optics developed rapidly in this period. By the ninth century, there were works on physiological, geometrical and physical optics. Topics covered included mirror reflection.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) wrote the book ''Ten Treatises on the Eye''; this remained influential in the West until the 17th century.

Optics developed rapidly in this period. By the ninth century, there were works on physiological, geometrical and physical optics. Topics covered included mirror reflection.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) wrote the book ''Ten Treatises on the Eye''; this remained influential in the West until the 17th century.

Advances in

Advances in

The fields of physics studied in this period, apart from optics and astronomy which are described separately, are aspects of

The fields of physics studied in this period, apart from optics and astronomy which are described separately, are aspects of

Many classical works, including those of Aristotle, were transmitted from Greek to Syriac, then to Arabic, then to Latin in the Middle Ages. Aristotle's zoology remained dominant in its field for two thousand years. The ''

Many classical works, including those of Aristotle, were transmitted from Greek to Syriac, then to Arabic, then to Latin in the Middle Ages. Aristotle's zoology remained dominant in its field for two thousand years. The ''

"How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs"

by De Lacy O'Leary * *Habibi, Golareh

is there such a thing as Islamic science? the influence of Islam on the world of science

''Science Creative Quarterly''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Science In Medieval Islam .Science Medieval history of the Middle East

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the

Science in the medieval Islamic world was the science developed and practised during the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

under the Umayyads of Córdoba, the Abbadids of Seville, the Samanids, the Ziyarids, the Buyids in Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

and beyond, spanning the period roughly between 786 and 1258. Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, mathematics, and medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

. Other subjects of scientific inquiry included alchemy and chemistry, botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

and agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and s ...

, geography and cartography, ophthalmology

Ophthalmology ( ) is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of eye disorders.

An ophthalmologist is a physician who undergoes subspecialty training in medical and surgical eye care. Following a med ...

, pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemi ...

, physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

, and zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, and ...

.

Medieval Islamic science had practical purposes as well as the goal of understanding. For example, astronomy was useful for determining the ''Qibla

The qibla ( ar, قِبْلَة, links=no, lit=direction, translit=qiblah) is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the s ...

'', the direction in which to pray, botany had practical application in agriculture, as in the works of Ibn Bassal and Ibn al-'Awwam

Ibn al-'Awwam ( ar, ابن العوام), also called Abu Zakariya Ibn al-Awwam ( ar, أبو زكريا بن العوام), was a Muslim Arab agriculturist who flourished at Seville (modern-day southern Spain) in the later 12th century. He wrote ...

, and geography enabled Abu Zayd al-Balkhi

Abu Zayd Ahmed ibn Sahl Balkhi ( fa, ابو زید احمد بن سهل بلخی) was a Persian Muslim polymath: a geographer, mathematician, physician, psychologist and scientist. Born in 850 CE in Shamistiyan, in the province of Balkh, Greate ...

to make accurate maps. Islamic mathematicians such as Al-Khwarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astrono ...

, Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

and Jamshīd al-Kāshī

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Jamshīd Masʿūd al-Kāshī (or al-Kāshānī) ( fa, غیاث الدین جمشید کاشانی ''Ghiyās-ud-dīn Jamshīd Kāshānī'') (c. 1380 Kashan, Iran – 22 June 1429 Samarkand, Transoxania) was a Persian astronom ...

made advances in algebra

Algebra () is one of the areas of mathematics, broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathem ...

, trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

, geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

and Arabic numerals

Arabic numerals are the ten numerical digits: , , , , , , , , and . They are the most commonly used symbols to write decimal numbers. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers such as ...

. Islamic doctors described diseases like smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) ce ...

and measles, and challenged classical Greek medical theory. Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of ...

, Avicenna and others described the preparation of hundreds of drugs

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhalat ...

made from medicinal plants

Medicinal plants, also called medicinal herbs, have been discovered and used in traditional medicine practices since prehistoric times. Plants synthesize hundreds of chemical compounds for various functions, including defense and protection ...

and chemical compounds. Islamic physicists such as Ibn Al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

, Al-Bīrūnī and others studied optics and mechanics as well as astronomy, and criticised Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

's view of motion.

During the Middle Ages, Islamic science flourished across a wide area around the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

and further afield, for several centuries, in a wide range of institutions.

Context and history

Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, and successfully displaced the Persian and Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantin ...

s from the region within a few decades. Within a century, Islam had reached the area of present-day Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

in the west and Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the former ...

in the east. The Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

(roughly between 786 and 1258) spanned the period of the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

(750–1258), with stable political structures and flourishing trade. Major religious and cultural works of the Islamic empire were translated into Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

and occasionally Persian. Islamic culture inherited Greek, Indic, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

n and Persian influences. A new common civilisation formed, based on Islam. An era of high culture and innovation ensued, with rapid growth in population and cities. The Arab Agricultural Revolution in the countryside brought more crops and improved agricultural technology, especially irrigation

Irrigation (also referred to as watering) is the practice of applying controlled amounts of water to land to help grow crops, landscape plants, and lawns. Irrigation has been a key aspect of agriculture for over 5,000 years and has been dev ...

. This supported the larger population and enabled culture to flourish.McClellan and Dorn 2006, pp.103–115 From the 9th century onwards, scholars such as Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

translated India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

n, Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

n, Sasanian (Persian) and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

knowledge, including the works of Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, into Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

. These translations supported advances by scientists across the Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

.

Islamic science survived the initial Christian reconquest of Spain, including the fall of

Islamic science survived the initial Christian reconquest of Spain, including the fall of Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

in 1248, as work continued in the eastern centres (such as in Persia). After the completion of the Spanish reconquest in 1492, the Islamic world went into an economic and cultural decline. The Abbasid caliphate was followed by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

( 1299–1922), centred in Turkey, and the Safavid Empire

Safavid Iran or Safavid Persia (), also referred to as the Safavid Empire, '. was one of the greatest Iranian empires after the 7th-century Muslim conquest of Persia, which was ruled from 1501 to 1736 by the Safavid dynasty. It is often consi ...

(1501–1736), centred in Persia, where work in the arts and sciences continued.

Fields of inquiry

Medieval Islamic scientific achievements encompassed a wide range of subject areas, especially mathematics,astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

, and medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, and Health promotion ...

. Other subjects of scientific inquiry included physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

, alchemy and chemistry, ophthalmology

Ophthalmology ( ) is a surgical subspecialty within medicine that deals with the diagnosis and treatment of eye disorders.

An ophthalmologist is a physician who undergoes subspecialty training in medical and surgical eye care. Following a med ...

, and geography and cartography.

Alchemy and chemistry

The early Islamic period saw the establishment of theoretical frameworks inalchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world ...

and chemistry. The sulfur-mercury theory of metals

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

, first found in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's '' Sirr al-khalīqa'' ("The Secret of Creation", c. 750–850) and in the writings attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

(written c. 850–950), remained the basis of theories of metallic composition until the 18th century. The '' Emerald Tablet'', a cryptic text that all later alchemists up to and including Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the g ...

saw as the foundation of their art, first occurs in the ''Sirr al-khalīqa'' and in one of the works attributed to Jabir. In practical chemistry, the works of Jabir, and those of the Persian alchemist and physician Abu Bakr al-Razi (c. 865–925), contain the earliest systematic classifications of chemical substances. Alchemists were also interested in artificially creating such substances. Jabir describes the synthesis of ammonium chloride ( sal ammoniac) from organic substances, and Abu Bakr al-Razi experimented with the heating of ammonium chloride, vitriol, and other salts

In chemistry, a salt is a chemical compound consisting of an ionic assembly of positively charged cations and negatively charged anions, which results in a compound with no net electric charge. A common example is table salt, with positively ...

, which would eventually lead to the discovery of the mineral acids by 13th-century Latin alchemists such as pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber (or "Latin pseudo-Geber") is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attributed to Jabir ...

.

Astronomy and cosmology

Astronomy became a major discipline within Islamic science. Astronomers devoted effort both towards understanding the nature of the cosmos and to practical purposes. One application involved determining the ''Qibla'', the direction to face during prayer. Another was

Astronomy became a major discipline within Islamic science. Astronomers devoted effort both towards understanding the nature of the cosmos and to practical purposes. One application involved determining the ''Qibla'', the direction to face during prayer. Another was astrology

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that claim to discern information about human affairs and terrestrial events by studying the apparent positions of celestial objects. Di ...

, predicting events affecting human life and selecting suitable times for actions such as going to war or founding a city. Al-Battani

Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Jābir ibn Sinān al-Raqqī al-Ḥarrānī aṣ-Ṣābiʾ al-Battānī ( ar, محمد بن جابر بن سنان البتاني) ( Latinized as Albategnius, Albategni or Albatenius) (c. 858 – 929) was an astron ...

(850–922) accurately determined the length of the solar year. He contributed to the Tables of Toledo

The ''Toledan Tables'', or ''Tables of Toledo'', were astronomical tables which were used to predict the movements of the Sun, Moon and planets relative to the fixed stars. They were a collection of mathematic tables that describe different aspec ...

, used by astronomers to predict the movements of the sun, moon and planets across the sky. Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formula ...

(1473-1543) later used some of Al-Battani's astronomic tables.

Al-Zarqali (1028–1087) developed a more accurate astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate incli ...

, used for centuries afterwards. He constructed a water clock

A water clock or clepsydra (; ; ) is a timepiece by which time is measured by the regulated flow of liquid into (inflow type) or out from (outflow type) a vessel, and where the amount is then measured.

Water clocks are one of the oldest time- ...

in Toledo

Toledo most commonly refers to:

* Toledo, Spain, a city in Spain

* Province of Toledo, Spain

* Toledo, Ohio, a city in the United States

Toledo may also refer to:

Places Belize

* Toledo District

* Toledo Settlement

Bolivia

* Toledo, Orur ...

, discovered that the Sun's apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. For example, the apsides of the Earth are called the aphelion and perihelion.

General description

There are two apsides in any el ...

moves slowly relative to the fixed stars, and obtained a good estimate of its motion for its rate of change. Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

(1201–1274) wrote an important revision to Ptolemy's 2nd-century celestial model. When Tusi became Helagu's astrologer, he was given an observatory and gained access to Chinese techniques and observations. He developed trigonometry

Trigonometry () is a branch of mathematics that studies relationships between side lengths and angles of triangles. The field emerged in the Hellenistic world during the 3rd century BC from applications of geometry to astronomical studies. ...

as a separate field, and compiled the most accurate astronomical tables available up to that time.

Botany and agronomy

The study of the natural world extended to a detailed examination of plants. The work done proved directly useful in the unprecedented growth of

The study of the natural world extended to a detailed examination of plants. The work done proved directly useful in the unprecedented growth of pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemi ...

across the Islamic world. Al-Dinawari

Abū Ḥanīfa Aḥmad ibn Dāwūd Dīnawarī ( fa, ابوحنيفه دينوری; died 895) was a Persian Islamic Golden Age polymath, astronomer, agriculturist, botanist, metallurgist, geographer, mathematician, and historian.

Life

Din ...

(815–896) popularised botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

in the Islamic world with his six-volume ''Kitab al-Nabat'' (''Book of Plants''). Only volumes 3 and 5 have survived, with part of volume 6 reconstructed from quoted passages. The surviving text describes 637 plants in alphabetical order from the letters ''sin'' to ''ya'', so the whole book must have covered several thousand kinds of plants. Al-Dinawari described the phases of plant growth and the production of flowers and fruit. The thirteenth century encyclopedia compiled by Zakariya al-Qazwini (1203–1283) – ''ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt'' (The Wonders of Creation) – contained, among many other topics, both realistic botany and fantastic accounts. For example, he described trees which grew birds on their twigs in place of leaves, but which could only be found in the far-distant British Isles., in Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp.813–852Turner 1997, pp.138–139 The use and cultivation of plants was documented in the 11th century by Muhammad bin Ibrāhīm Ibn Bassāl of Toledo

Toledo most commonly refers to:

* Toledo, Spain, a city in Spain

* Province of Toledo, Spain

* Toledo, Ohio, a city in the United States

Toledo may also refer to:

Places Belize

* Toledo District

* Toledo Settlement

Bolivia

* Toledo, Orur ...

in his book ''Dīwān al-filāha'' (The Court of Agriculture), and by Ibn al-'Awwam al-Ishbīlī (also called Abū l-Khayr al-Ishbīlī) of Seville

Seville (; es, Sevilla, ) is the capital and largest city of the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the River Guadalquivir, in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsul ...

in his 12th century book ''Kitāb al-Filāha'' (Treatise on Agriculture). Ibn Bassāl had travelled widely across the Islamic world, returning with a detailed knowledge of agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and s ...

that fed into the Arab Agricultural Revolution. His practical and systematic book describes over 180 plants and how to propagate and care for them. It covered leaf- and root-vegetables, herbs, spices and trees.

Geography and cartography

The spread of Islam across Western Asia and North Africa encouraged an unprecedented growth in trade and travel by land and sea as far away as Southeast Asia, China, much of Africa, Scandinavia and even Iceland. Geographers worked to compile increasingly accurate maps of the known world, starting from many existing but fragmentary sources.

The spread of Islam across Western Asia and North Africa encouraged an unprecedented growth in trade and travel by land and sea as far away as Southeast Asia, China, much of Africa, Scandinavia and even Iceland. Geographers worked to compile increasingly accurate maps of the known world, starting from many existing but fragmentary sources. Abu Zayd al-Balkhi

Abu Zayd Ahmed ibn Sahl Balkhi ( fa, ابو زید احمد بن سهل بلخی) was a Persian Muslim polymath: a geographer, mathematician, physician, psychologist and scientist. Born in 850 CE in Shamistiyan, in the province of Balkh, Greate ...

(850–934), founder of the Balkhī school of cartography in Baghdad, wrote an atlas called ''Figures of the Regions'' (Suwar al-aqalim).

Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of ...

(973–1048) measured the radius of the earth using a new method. It involved observing the height of a mountain at Nandana (now in Pakistan). Al-Idrisi (1100–1166) drew a map of the world for Roger

Roger is a given name, usually masculine, and a surname. The given name is derived from the Old French personal names ' and '. These names are of Germanic origin, derived from the elements ', ''χrōþi'' ("fame", "renown", "honour") and ', ' ...

, the Norman King of Sicily (ruled 1105-1154). He also wrote the '' Tabula Rogeriana'' (Book of Roger), a geographic study of the peoples, climates, resources and industries of the whole of the world known at that time. The Ottoman admiral Piri Reis

Ahmet Muhiddin Piri ( 1465 – 1553), better known as Piri Reis ( tr, Pîrî Reis or '' Hacı Ahmet Muhittin Pîrî Bey''), was a navigator, geographer and cartographer. He is primarily known today for his maps and charts collected in his ''K ...

( 1470–1553) made a map of the New World and West Africa in 1513. He made use of maps from Greece, Portugal, Muslim sources, and perhaps one made by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

. He represented a part of a major tradition of Ottoman cartography.

Mathematics

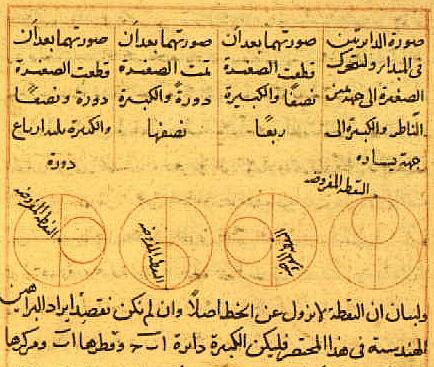

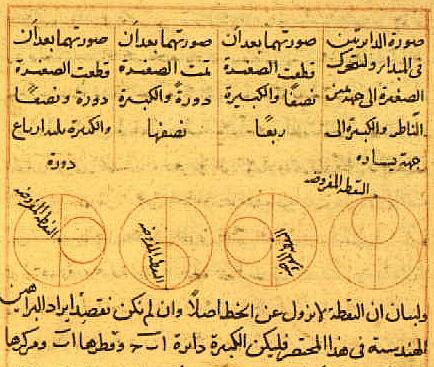

Islamic mathematicians gathered, organised and clarified the mathematics they inherited from ancient Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia and Persia, and went on to make innovations of their own. Islamic mathematics covered

Islamic mathematicians gathered, organised and clarified the mathematics they inherited from ancient Egypt, Greece, India, Mesopotamia and Persia, and went on to make innovations of their own. Islamic mathematics covered algebra

Algebra () is one of the areas of mathematics, broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathem ...

, geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

and arithmetic

Arithmetic () is an elementary part of mathematics that consists of the study of the properties of the traditional operations on numbers—addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, exponentiation, and extraction of roots. In the 19th c ...

. Algebra was mainly used for recreation: it had few practical applications at that time. Geometry was studied at different levels. Some texts contain practical geometrical rules for surveying and for measuring figures. Theoretical geometry was a necessary prerequisite for understanding astronomy and optics, and it required years of concentrated work. Early in the Abbasid caliphate (founded 750), soon after the foundation of Baghdad in 762, some mathematical knowledge was assimilated by al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (; ar, أبو جعفر عبد الله بن محمد المنصور; 95 AH – 158 AH/714 CE – 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab Al-Manṣūr (المنصور) ...

's group of scientists from the pre-Islamic Persian tradition in astronomy. Astronomers from India were invited to the court of the caliph in the late eighth century; they explained the rudimentary trigonometrical techniques used in Indian astronomy. Ancient Greek works such as Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it cano ...

'' and Euclid's ''Elements'' were translated into Arabic. By the second half of the ninth century, Islamic mathematicians were already making contributions to the most sophisticated parts of Greek geometry. Islamic mathematics reached its apogee in the Eastern part of the Islamic world between the tenth and twelfth centuries. Most medieval Islamic mathematicians wrote in Arabic, others in Persian.

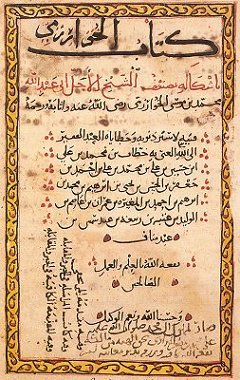

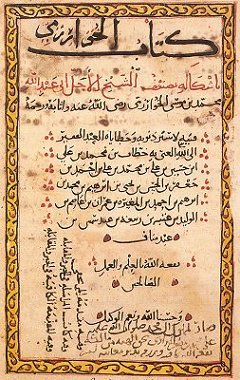

Al-Khwarizmi

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī ( ar, محمد بن موسى الخوارزمي, Muḥammad ibn Musā al-Khwārazmi; ), or al-Khwarizmi, was a Persian polymath from Khwarazm, who produced vastly influential works in mathematics, astrono ...

(8th–9th centuries) was instrumental in the adoption of the Hindu–Arabic numeral system

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system or Indo-Arabic numeral system Audun HolmeGeometry: Our Cultural Heritage 2000 (also called the Hindu numeral system or Arabic numeral system) is a positional decimal numeral system, and is the most common syste ...

and the development of algebra

Algebra () is one of the areas of mathematics, broad areas of mathematics. Roughly speaking, algebra is the study of mathematical symbols and the rules for manipulating these symbols in formulas; it is a unifying thread of almost all of mathem ...

, introduced methods of simplifying equations, and used Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to ancient Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry: the ''Elements''. Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small set of intuitively appealing axioms ...

in his proofs. He was the first to treat algebra as an independent discipline in its own right,, page 263–277: "In a sense, al-Khwarizmi is more entitled to be called "the father of algebra" than Diophantus because al-Khwarizmi is the first to teach algebra in an elementary form and for its own sake, Diophantus is primarily concerned with the theory of numbers". and presented the first systematic solution of linear

Linearity is the property of a mathematical relationship ('' function'') that can be graphically represented as a straight line. Linearity is closely related to '' proportionality''. Examples in physics include rectilinear motion, the linear ...

and quadratic equations.Maher, P. (1998). From Al-Jabr to Algebra. Mathematics in School, 27(4), 14–15.

Ibn Ishaq al-Kindi (801–873) worked on cryptography for the Abbasid Caliphate

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Mutta ...

, and gave the first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis and the first description of the method of frequency analysis

In cryptanalysis, frequency analysis (also known as counting letters) is the study of the frequency of letters or groups of letters in a ciphertext. The method is used as an aid to breaking classical ciphers.

Frequency analysis is based on ...

.

Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

( 980–1037) contributed to mathematical techniques such as casting out nines.Masood 2009, pp.104–105 Thābit ibn Qurra

Thābit ibn Qurra (full name: , ar, أبو الحسن ثابت بن قرة بن زهرون الحراني الصابئ, la, Thebit/Thebith/Tebit); 826 or 836 – February 19, 901, was a mathematician, physician, astronomer, and translator ...

(835–901) calculated the solution to a chessboard problem involving an exponential series.

Al-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Is ...

( 870–950) attempted to describe, geometrically, the repeating patterns popular in Islamic decorative motifs in his book ''Spiritual Crafts and Natural Secrets in the Details of Geometrical Figures''. Omar Khayyam (1048–1131), known in the West as a poet, calculated the length of the year to within 5 decimal places, and found geometric solutions to all 13 forms of cubic equations, developing some quadratic equations still in use. Jamshīd al-Kāshī

Ghiyāth al-Dīn Jamshīd Masʿūd al-Kāshī (or al-Kāshānī) ( fa, غیاث الدین جمشید کاشانی ''Ghiyās-ud-dīn Jamshīd Kāshānī'') (c. 1380 Kashan, Iran – 22 June 1429 Samarkand, Transoxania) was a Persian astronom ...

( 1380–1429) is credited with several theorems of trigonometry, including the law of cosines

In trigonometry, the law of cosines (also known as the cosine formula, cosine rule, or al-Kashi's theorem) relates the lengths of the sides of a triangle to the cosine of one of its angles. Using notation as in Fig. 1, the law of cosines stat ...

, also known as Al-Kashi's Theorem. He has been credited with the invention of decimal fractions, and with a method like Horner's to calculate roots. He calculated π correctly to 17 significant figures.

Sometime around the seventh century, Islamic scholars adopted the Hindu–Arabic numeral system

The Hindu–Arabic numeral system or Indo-Arabic numeral system Audun HolmeGeometry: Our Cultural Heritage 2000 (also called the Hindu numeral system or Arabic numeral system) is a positional decimal numeral system, and is the most common syste ...

, describing their use in a standard type of text ''fī l-ḥisāb al hindī'', (On the numbers of the Indians). A distinctive Western Arabic variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals began to emerge around the 10th century in the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

and Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mus ...

(sometimes called ''ghubar'' numerals, though the term is not always accepted), which are the direct ancestor of the modern Arabic numerals

Arabic numerals are the ten numerical digits: , , , , , , , , and . They are the most commonly used symbols to write decimal numbers. They are also used for writing numbers in other systems such as octal, and for writing identifiers such as ...

used throughout the world.

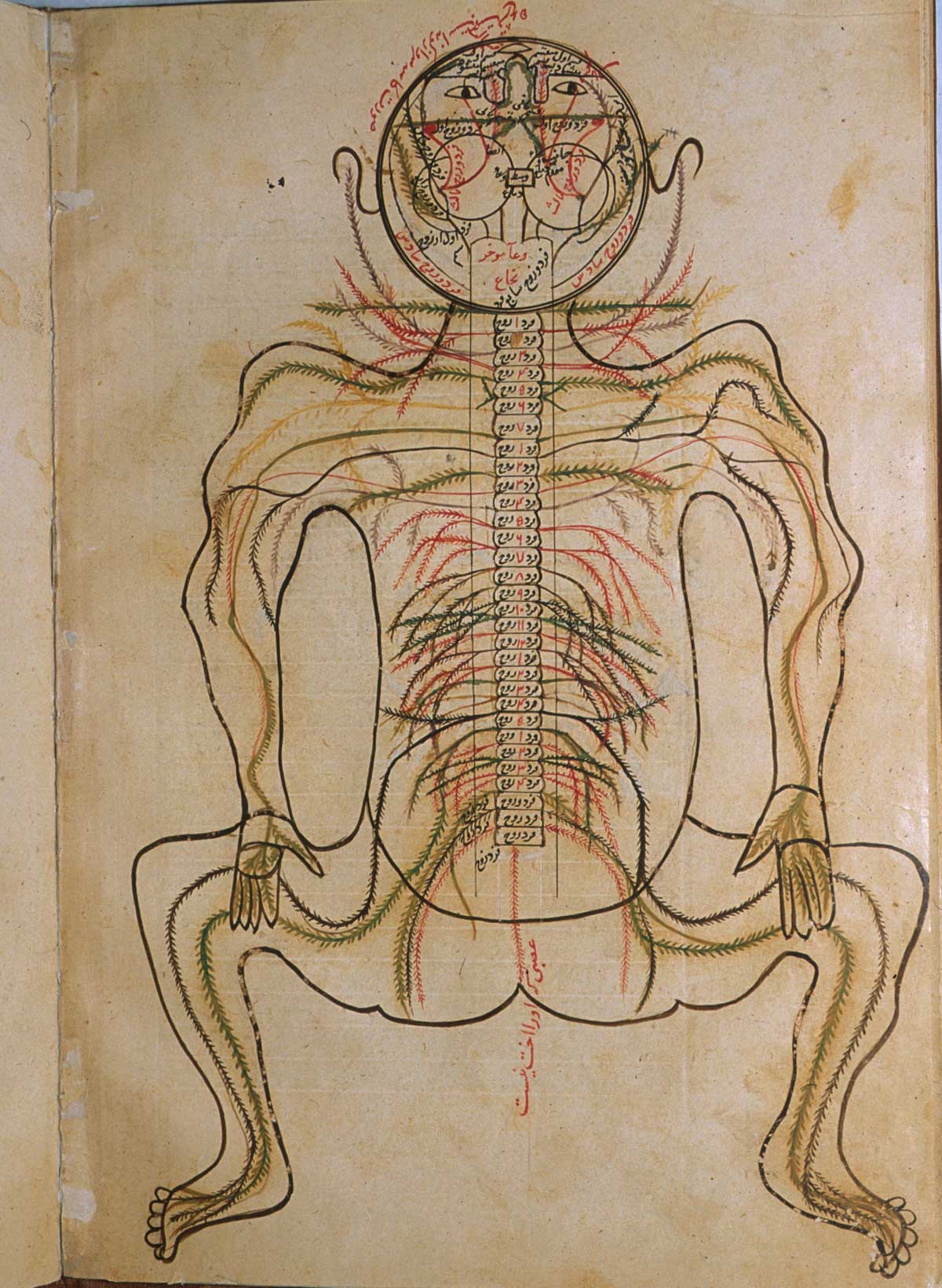

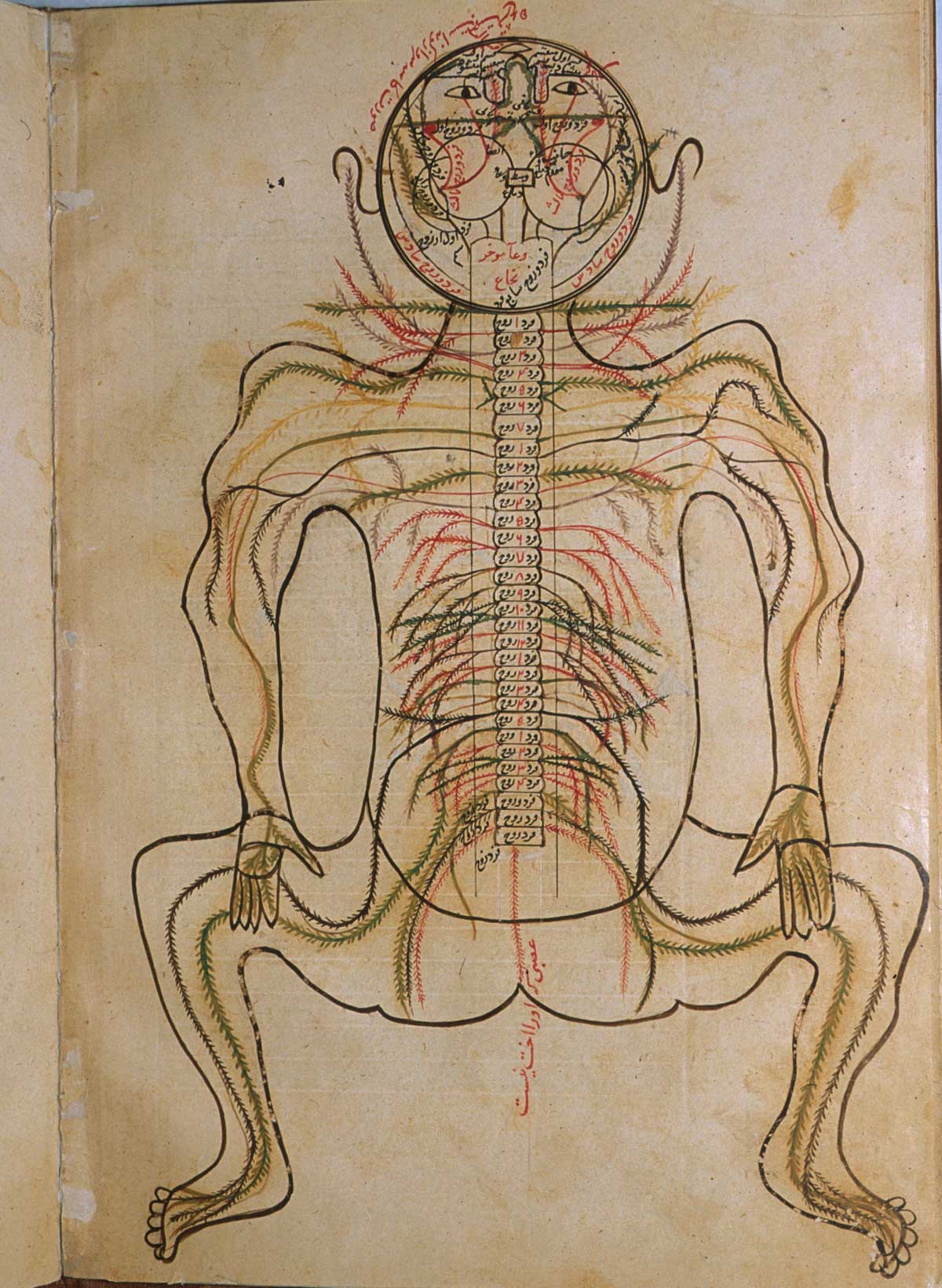

Medicine

Islamic society paid careful attention to medicine, following a ''

Islamic society paid careful attention to medicine, following a ''hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

'' enjoining the preservation of good health. Its physicians inherited knowledge and traditional medical beliefs from the civilisations of classical Greece, Rome, Syria, Persia and India. These included the writings of Hippocrates

Hippocrates of Kos (; grc-gre, Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; ), also known as Hippocrates II, was a Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history o ...

such as on the theory of the four humours, and the theories of Galen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus ( el, Κλαύδιος Γαληνός; September 129 – c. AD 216), often Anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Greek physician, surgeon and philosopher in the Roman Empire. Considered to be on ...

. al-Razi ( 865–925) identified smallpox and measles, and recognized fever as a part of the body's defenses. He wrote a 23-volume compendium of Chinese, Indian, Persian, Syriac and Greek medicine. al-Razi questioned the classical Greek medical theory of how the four humours regulate life processes

''Life Processes'' is the second album by ¡Forward, Russia!, and was released in the UK on 14 April 2008. It was produced by former Minus the Bear keyboardist Matt Bayles at Red Room Recordings in Seattle, Washington. The first single from th ...

. He challenged Galen's work on several fronts, including the treatment of bloodletting

Bloodletting (or blood-letting) is the withdrawal of blood from a patient to prevent or cure illness and disease. Bloodletting, whether by a physician or by leeches, was based on an ancient system of medicine in which blood and other bodily flu ...

, arguing that it was effective.

al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinisation of names, Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''A ...

(936–1013) was a surgeon whose most important surviving work is referred to as ''al-Tasrif

The ''Kitāb al-Taṣrīf'' ( ar, كتاب التصريف لمن عجز عن التأليف, lit=The Arrangement of Medical Knowledge for One Who is Not Able to Compile a Book for Himself), known in English as The Method of Medicine, is a 30-volume ...

'' (Medical Knowledge). It is a 30-volume set mainly discussing medical symptoms, treatments, and pharmacology. The last volume, on surgery, describes surgical instruments, supplies, and pioneering procedures. Avicenna ( 980–1037) wrote the major medical textbook, ''The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' ( ar, القانون في الطب, italic=yes ''al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb''; fa, قانون در طب, italic=yes, ''Qanun-e dâr Tâb'') is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Persian physician-phi ...

''. Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) wrote an influential book on medicine; it largely replaced Avicenna's ''Canon'' in the Islamic world. He wrote commentaries on Galen and on Avicenna's works. One of these commentaries, discovered in 1924, described the circulation of blood through the lungs.

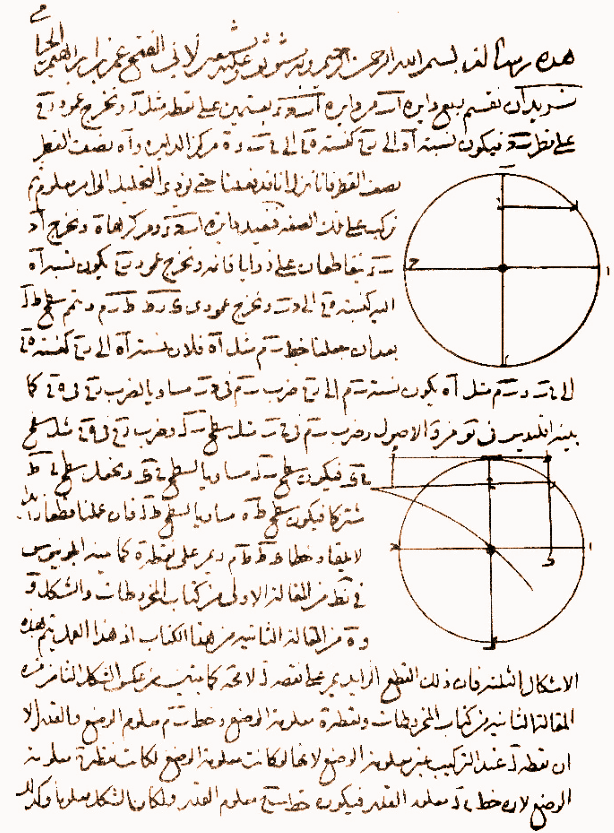

Optics and ophthalmology

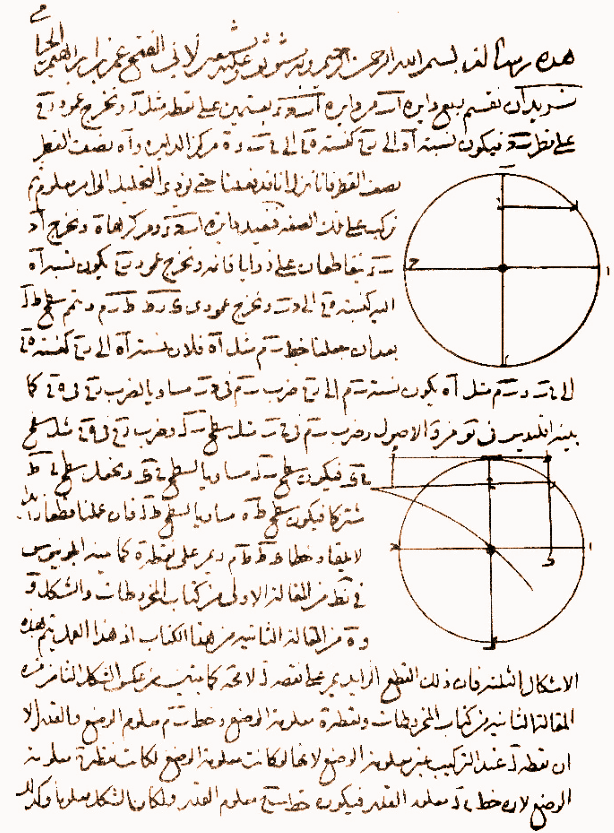

Optics developed rapidly in this period. By the ninth century, there were works on physiological, geometrical and physical optics. Topics covered included mirror reflection.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) wrote the book ''Ten Treatises on the Eye''; this remained influential in the West until the 17th century.

Optics developed rapidly in this period. By the ninth century, there were works on physiological, geometrical and physical optics. Topics covered included mirror reflection.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) wrote the book ''Ten Treatises on the Eye''; this remained influential in the West until the 17th century.

Abbas ibn Firnas

Abu al-Qasim Abbas ibn Firnas ibn Wirdas al-Takurini ( ar, أبو القاسم عباس بن فرناس بن ورداس التاكرني; c. 809/810 – 887 A.D.), also known as Abbas ibn Firnas ( ar, عباس ابن فرناس), Latinized Arme ...

(810–887) developed lenses for magnification and the improvement of vision.

Ibn Sahl ( 940–1000) discovered the law of refraction known as Snell's law

Snell's law (also known as Snell–Descartes law and ibn-Sahl law and the law of refraction) is a formula used to describe the relationship between the angles of incidence and refraction, when referring to light or other waves passing through ...

. He used the law to produce the first Aspheric lenses that focused light without geometric aberrations.

In the eleventh century Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

(Alhazen, 965–1040) rejected the Greek ideas about vision, whether the Aristotelian tradition that held that the form of the perceived object entered the eye (but not its matter), or that of Euclid and Ptolemy which held that the eye emitted a ray. Al-Haytham proposed in his ''Book of Optics'' that vision occurs by way of light rays forming a cone with its vertex at the center of the eye. He suggested that light was reflected from different surfaces in different directions, thus causing objects to look different. He argued further that the mathematics of reflection and refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomen ...

needed to be consistent with the anatomy of the eye.Masood 2009, pp.173–175 He was also an early proponent of the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

, the concept that a hypothesis must be proved by experiments based on confirmable procedures or mathematical evidence, five centuries before Renaissance scientists

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a Periodization, period in History of Europe, European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an e ...

.

Pharmacology

Advances in

Advances in botany

Botany, also called plant science (or plant sciences), plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "bot ...

and chemistry in the Islamic world encouraged developments in pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemi ...

. Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes) (865–915) promoted the medical uses of chemical compounds. Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi

Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn al-'Abbās al-Zahrāwī al-Ansari ( ar, أبو القاسم خلف بن العباس الزهراوي; 936–1013), popularly known as al-Zahrawi (), Latinised as Albucasis (from Arabic ''Abū al-Qāsim''), was ...

(Abulcasis) (936–1013) pioneered the preparation of medicines by sublimation

Sublimation or sublimate may refer to:

* ''Sublimation'' (album), by Canvas Solaris, 2004

* Sublimation (phase transition), directly from the solid to the gas phase

* Sublimation (psychology), a mature type of defense mechanism

* Sublimate of mer ...

and distillation

Distillation, or classical distillation, is the process of separating the components or substances from a liquid mixture by using selective boiling and condensation, usually inside an apparatus known as a still. Dry distillation is the he ...

. His ''Liber servitoris'' provides instructions for preparing "simples" from which were compounded the complex drugs then used. Sabur Ibn Sahl (died 869) was the first physician to describe a large variety of drugs and remedies for ailments. Al-Muwaffaq, in the 10th century, wrote ''The foundations of the true properties of Remedies'', describing chemicals such as arsenious oxide and silicic acid. He distinguished between sodium carbonate and potassium carbonate

Potassium carbonate is the inorganic compound with the formula K2 CO3. It is a white salt, which is soluble in water. It is deliquescent, often appearing as a damp or wet solid. Potassium carbonate is mainly used in the production of soap and gl ...

, and drew attention to the poisonous nature of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish ...

compounds, especially copper vitriol, and also of lead

Lead is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metals, heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale of mineral hardness#Intermediate ...

compounds. Al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of ...

(973–1050) wrote the ''Kitab al-Saydalah'' (''The Book of Drugs''), describing in detail the properties of drugs, the role of pharmacy and the duties of the pharmacist. Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

(Avicenna) described 700 preparations, their properties, their mode of action and their indications. He devoted a whole volume to simples in ''The Canon of Medicine

''The Canon of Medicine'' ( ar, القانون في الطب, italic=yes ''al-Qānūn fī al-Ṭibb''; fa, قانون در طب, italic=yes, ''Qanun-e dâr Tâb'') is an encyclopedia of medicine in five books compiled by Persian physician-phi ...

''. Works by Masawaih al-Mardini ( 925–1015) and by Ibn al-Wafid (1008–1074) were printed in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

more than fifty times, appearing as ''De Medicinis universalibus et particularibus'' by Mesue the Younger (died 1015) and as the ''Medicamentis simplicibus'' by Abenguefit ( 997 – 1074) respectively. Peter of Abano (1250–1316) translated and added a supplement to the work of al-Mardini under the title ''De Veneris''. Ibn al-Baytar

Diyāʾ al-Dīn Abū Muḥammad ʿAbd Allāh ibn Aḥmad al-Mālaqī, commonly known as Ibn al-Bayṭār () (1197–1248 AD) was an Andalusian Arab physician, botanist, pharmacist and scientist. His main contribution was to systematically record ...

(1197–1248), in his ''Al-Jami fi al-Tibb'', described a thousand simples and drugs based directly on Mediterranean plants collected along the entire coast between Syria and Spain, for the first time exceeding the coverage provided by Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides ( grc-gre, Πεδάνιος Διοσκουρίδης, ; 40–90 AD), “the father of pharmacognosy”, was a Greek physician, pharmacologist, botanist, and author of '' De materia medica'' (, On Medical Material) —a 5-vo ...

in classical times. Islamic physicians such as Ibn Sina described clinical trials

Clinical trials are prospective biomedical or behavioral research studies on human participants designed to answer specific questions about biomedical or behavioral interventions, including new treatments (such as novel vaccines, drugs, dietar ...

for determining the efficacy of medical drug

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via inhal ...

s and substances.

Physics

The fields of physics studied in this period, apart from optics and astronomy which are described separately, are aspects of

The fields of physics studied in this period, apart from optics and astronomy which are described separately, are aspects of mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects ...

: statics

Statics is the branch of classical mechanics that is concerned with the analysis of force and torque (also called moment) acting on physical systems that do not experience an acceleration (''a''=0), but rather, are in static equilibrium with t ...

, dynamics, kinematics and motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

. In the sixth century John Philoponus ( 490 – 570) rejected the Aristotelian view of motion. He argued instead that an object acquires an inclination to move when it has a motive power impressed on it. In the eleventh century Ibn Sina adopted roughly the same idea, namely that a moving object has force which is dissipated by external agents like air resistance. Ibn Sina distinguished between "force" and "inclination" (''mayl''); he claimed that an object gained ''mayl'' when the object is in opposition to its natural motion. He concluded that continuation of motion depends on the inclination that is transferred to the object, and that the object remains in motion until the ''mayl'' is spent. He also claimed that a projectile in a vacuum would not stop unless it is acted upon. That view accords with Newton's first law of motion, on inertia. As a non-Aristotelian suggestion, it was essentially abandoned until it was described as "impetus" by Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career who focused in particular on logic and the w ...

( 1295–1363), who was influenced by Ibn Sina's ''Book of Healing''.

In the ''Shadows'', Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī (973–1048) describes non-uniform motion as the result of acceleration. Ibn-Sina's theory of ''mayl'' tried to relate the velocity and weight of a moving object, a precursor of the concept of momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass ...

. Aristotle's theory of motion stated that a constant force produces a uniform motion; Abu'l-Barakāt al-Baghdādī ( 1080 – 1164/5) disagreed, arguing that velocity and acceleration are two different things, and that force is proportional to acceleration, not to velocity.

Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

(Avempace, 1085–1138) proposed that for every force there is a reaction force. While he did not specify that these forces be equal, this was still an early version of Newton's third law of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

.

The Banu Musa brothers, Jafar-Muhammad, Ahmad and al-Hasan ( early 9th century) invented automated devices described in their Book of Ingenious Devices

The ''Book of Ingenious Devices'' (Arabic: كتاب الحيل ''Kitab al-Hiyal'', Persian: كتاب ترفندها ''Ketab tarfandha'', literally: "The Book of Tricks") is a large illustrated work on mechanical devices, including automata, pub ...

. Advances on the subject were also made by al-Jazari and Ibn Ma'ruf.

Zoology

Many classical works, including those of Aristotle, were transmitted from Greek to Syriac, then to Arabic, then to Latin in the Middle Ages. Aristotle's zoology remained dominant in its field for two thousand years. The ''

Many classical works, including those of Aristotle, were transmitted from Greek to Syriac, then to Arabic, then to Latin in the Middle Ages. Aristotle's zoology remained dominant in its field for two thousand years. The ''Kitāb al-Hayawān

The ''Kitāb al-Ḥayawān'' ( ar, كتاب الحيوان, , ''LINA saadouni'') is an Arabic translation for hayawan (Arabic: , maqālāt).

'' Historia Animalium'': treatises 1–10;

'' De Partibus Animalium'': treatises 11–14;

'' De Generati ...

'' (كتاب الحيوان, English: ''Book of Animals'') is a 9th-century Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walte ...

translation of ''History of Animals'': 1–10, ''On the Parts of Animals'': 11–14, and ''Generation of Animals'': 15–19.

The book was mentioned by Al-Kindī (died 850), and commented on by Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

(Ibn Sīnā) in his ''The Book of Healing

''The Book of Healing'' (; ; also known as ) is a scientific and philosophical encyclopedia written by Abu Ali ibn Sīna (aka Avicenna) from medieval Persia, near Bukhara in Maverounnahr. He most likely began to compose the book in 1014, comp ...

''. Avempace

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an Ar ...

(Ibn Bājja) and Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psych ...

(Ibn Rushd) commented on and criticised ''On the Parts of Animals'' and ''Generation of Animals''.

Significance

Muslim scientists helped in laying the foundations for anexperiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs wh ...

al science with their contributions to the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article hist ...

and their empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

, experimental and quantitative

Quantitative may refer to:

* Quantitative research, scientific investigation of quantitative properties

* Quantitative analysis (disambiguation)

* Quantitative verse, a metrical system in poetry

* Statistics, also known as quantitative analysis ...

approach to scientific inquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ...

. Durant, Will (1980). ''The Age of Faith ( The Story of Civilization, Volume 4)'', p. 162–186. Simon & Schuster. . Garrison, Fielding H., ''An Introduction to the History of Medicine: with Medical Chronology, Suggestions for Study and Bibliographic Data'', p. 86. In a more general sense, the positive achievement of Islamic science was simply to flourish, for centuries, in a wide range of institutions from observatories to libraries, madrasas to hospitals and courts, both at the height of the Islamic golden age and for some centuries afterwards. It did not lead to a scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transformed ...

like that in Early modern Europe, but such external comparisons are probably to be rejected as imposing "chronologically and culturally alien standards" on a successful medieval culture.

See also

* Continuity thesis * Indian influence on Islamic science * History of scientific method * History of Islamic economics *Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic ...

* Islamic attitudes towards science

Muslim scholars have developed a spectrum of viewpoints on science within the context of Islam.Seyyed Hossein Nasr. "Islam and Modern Science" The Quran and Islam allows for much interpretation when it comes to science. Scientists of medieval Mu ...

* Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translat ...

* Timeline of science and engineering in the Muslim world

References

Sources

* * * * *Further reading

* * * * * *External links

"How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs"

by De Lacy O'Leary * *Habibi, Golareh

is there such a thing as Islamic science? the influence of Islam on the world of science

''Science Creative Quarterly''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Science In Medieval Islam .Science Medieval history of the Middle East

Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...