Islamic schools and branches have different understandings of

Islam. There are many different sects or denominations,

schools of Islamic jurisprudence, and

schools of Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding '' ʿaqīdah'' (creed). The main schools of Islamic Theology include the Qadariyah, Falasifa, Jahmiyya, Murji'ah, Muʿtazila, Bat ...

, or ''

ʿaqīdah

''Aqidah'' ( (), plural ''ʿaqāʾid'', also rendered ''ʿaqīda'', ''aqeeda'', etc.) is an Islamic term of Arabic origin that literally means "creed". It is also called Islamic creed and Islamic theology.

''Aqidah'' go beyond concise statem ...

'' (creed). Within Islamic groups themselves there may be differences, such as different orders (''

tariqa

A tariqa (or ''tariqah''; ar, طريقة ') is a school or order of Sufism, or specifically a concept for the mystical teaching and spiritual practices of such an order with the aim of seeking ''haqiqa'', which translates as "ultimate truth".

...

'') within

Sufism, and within

Sunnī Islam different schools of theology (

Atharī

Atharī theology or Atharism ( ar, الأثرية: / , " archeological"), otherwise referred to as Traditionalist theology or Scripturalist theology, is one of the main Sunni schools of Islamic theology. It emerged as an Islamic scholarly mov ...

,

Ashʿarī,

Māturīdī) and jurisprudence (

Ḥanafī,

Mālikī,

Shāfiʿī,

Ḥanbalī).

Groups in Islam may be numerous (the largest branches are

Shīʿas and

Sunnīs), or relatively small in size (

Ibadis

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

,

Zaydīs,

Ismāʿīlīs). Differences between the groups may not be well known to Muslims outside of scholarly circles, or may have induced enough passion to have resulted in

political

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

and

religious violence

Religious violence covers phenomena in which religion is either the subject or the object of violent behavior. All the religions of the world contain narratives, symbols, and metaphors of violence and war. Religious violence is violence th ...

(

Barelvi

The Barelvi movement ( ur, بَریلوِی, , ), also known as Ahl al-Sunnah wa'l-Jamaah (People of the Prophet's Way and the Community) is a Sunni revivalist movement following the Hanafi and Shafi'i school of jurisprudence, with strong Suf ...

,

Deobandi,

Salafism

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

,

Wahhabism

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, and ...

).

There are informal movements driven by ideas (such as

Islamic modernism

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge" attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with modern values such as democracy, civil rights, rationality, ...

and

Islamism) as well as organized groups with a governing body (

Ahmadiyya

Ahmadiyya (, ), officially the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community or the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at (AMJ, ar, الجماعة الإسلامية الأحمدية, al-Jamāʿah al-Islāmīyah al-Aḥmadīyah; ur, , translit=Jamā'at Aḥmadiyyah Musl ...

,

Ismāʿīlism,

Nation of Islam). Some of the Islamic sects and groups regard certain others as deviant or

accuse them of being not truly Muslim (for example,

Sunnīs frequently discriminate

Ahmadiyya

Ahmadiyya (, ), officially the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community or the Ahmadiyya Muslim Jama'at (AMJ, ar, الجماعة الإسلامية الأحمدية, al-Jamāʿah al-Islāmīyah al-Aḥmadīyah; ur, , translit=Jamā'at Aḥmadiyyah Musl ...

,

Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isl ...

,

Quranists

Quranism ( ar, القرآنية, translit=al-Qurʾāniyya'';'' also known as Quran-only Islam) Brown, ''Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought'', 1996: p.38-42 is a movement within Islam. It holds the belief that traditional religious c ...

, and

Shīʿas).

Some Islamic sects and groups date back to the

early history of Islam

The history of Islam concerns the political, social, economic, military, and cultural developments of the Islamic civilization. Most historians believe that Islam originated in Mecca and Medina at the start of the 7th century CE. Muslims re ...

between the 7th and 9th centuries CE (

Kharijites,

Sunnīs,

Shīʿas), whereas others have arisen much more recently (

Islamic neo-traditionalism

Islamic neo-traditionalism is a contemporary strand of Sunni Islam that emphasizes adherence to the four principal Sunni schools of law (''madhahib''), belief in one of the three schools of theology (Ash'ari, Maturidi, and to a lesser extent the ...

,

liberalism and progressivism,

Islamic modernism

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge" attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with modern values such as democracy, civil rights, rationality, ...

,

Salafism and Wahhabism) or even in the 20th century (

Nation of Islam). Still others were influential in their time but are not longer in existence (non-Ibadi

Kharijites,

Muʿtazila,

Murji'ah

Murji'ah ( ar, المرجئة, English: "Those Who Postpone"), also known as Murji'as or Murji'ites, were an early Islamic sect. Murji'ah held the opinion that God alone has the right to judge whether or not a Muslim has become an apostate. Conseq ...

).

Overview

The original schism between

Kharijites,

Sunnīs, and

Shīʿas among

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

was disputed over the

political and religious succession to the guidance of the

Muslim community

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

(''Ummah'') after the death of the

Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

.

From their essentially political position, the Kharijites developed extreme doctrines that set them apart from both mainstream Sunnī and Shīʿa Muslims.

Shīʿas believe

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib is the true successor to Muhammad, while Sunnīs consider

Abu Bakr

Abu Bakr Abdallah ibn Uthman Abi Quhafa (; – 23 August 634) was the senior companion and was, through his daughter Aisha, a father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, as well as the first caliph of Islam. He is known with the honor ...

to hold that position. The Kharijites broke away from both the Shīʿas and the Sunnīs during the

First Fitna (the first Islamic Civil War);

they were particularly noted for adopting a radical approach to ''

takfīr'' (excommunication), whereby they declared both Sunnī and Shīʿa Muslims to be either

infidels

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or the irreligious.

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which the Church ...

(''kuffār'') or

false Muslims (''munāfiḳūn''), and therefore deemed them

worthy of death for their perceived

apostasy

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

(''ridda'').

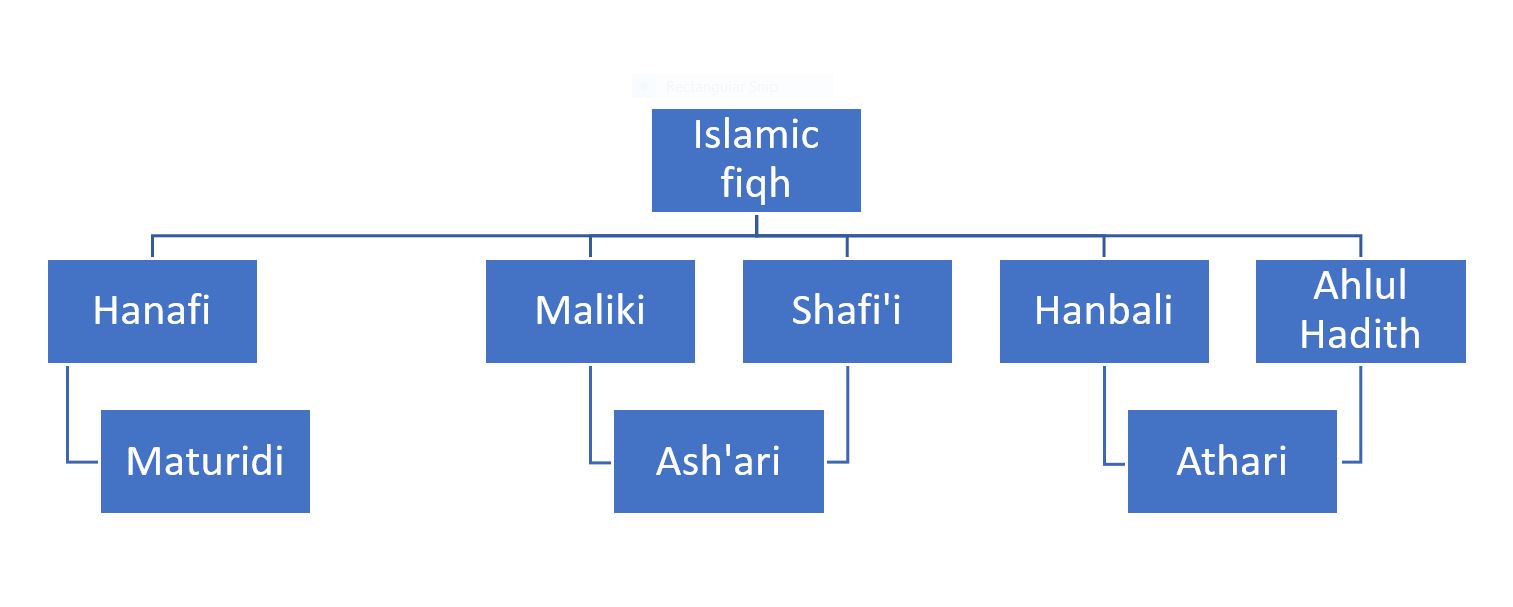

In addition, there are several differences within Sunnī and Shīʿa Islam: Sunnī Islam is separated into four main schools of jurisprudence, namely

Mālikī,

Ḥanafī,

Shāfiʿī, and

Ḥanbalī; these schools are named after their founders

Mālik ibn Anas,

Abū Ḥanīfa al-Nuʿmān,

Muḥammad ibn Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī

, and

Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal, respectively.

Shīʿa Islam, on the other hand, is separated into three major sects:

Twelvers

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

,

Ismāʿīlīs, and

Zaydīs. The vast majority of Shīʿa Muslims are Twelvers (a 2012 estimate puts the figure as 85%), to the extent that the term "Shīʿa" frequently refers to Twelvers by default. All mainstream Twelver and Ismāʿīlī Shīʿa Muslims follow the same school of thought, the

Jaʽfari jurisprudence

Jaʿfarī jurisprudence ( ar, الفقه الجعفري; also called Jafarite in English), Jaʿfarī school or Jaʿfarī fiqh, is the school of jurisprudence (''fiqh'') in Twelver and Ismaili (including Nizari) Shia Islam, named after the sixth ...

, named after

Jaʿfar al-Ṣādiq, the

sixth Shīʿīte Imam.

Zaydīs, also known as Fivers, follow the Zaydī school of thought (named after

Zayd ibn ʿAlī).

Ismāʿīlīsm is another offshoot of Shīʿa Islam that later split into

Nizārī

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

and

Musta‘lī, and the Musta‘lī further divided into

Ḥāfiẓi and

Ṭayyibi.

[Öz, Mustafa, ''Mezhepler Tarihi ve Terimleri Sözlüğü (The History of ]madh'hab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within ''fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE a ...

s and its terminology dictionary),'' Ensar Publications, İstanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_in ...

, 2011. Ṭayyibi Ismāʿīlīs, also known as "Bohras", are split between

Dawudi Bohras,

Sulaymani Bohras

The Sulaymani branch of Tayyibi Isma'ilism is an Islamic community, of which around 70,000 members reside in Yemen, while a few thousand Sulaymani Bohras can be found in India. The Sulaymanis are sometimes headed by a ''Da'i al-Mutlaq'' from th ...

, and

Alavi Bohras

The Alavi Bohras are a Tayyibi Musta'lavi Isma'ili Shi'i Muslim community from Gujarat, India. In India, during the time of the 18th Fatimid Imam Al-Mustansir Billah around 1093 AD in Egypt, the designated learned people (''wulaat'') wh ...

.

Similarly,

Kharijites were initially divided into five major branches:

Sufri

The Sufris ( ar, الصفرية ''aṣ-Ṣufriyya'') were Khariji Muslims in the seventh and eighth centuries. They established the Midrarid state at Sijilmassa, now in Morocco.

In Tlemcen, Algeria, the Banu Ifran were Sufri Berbers who oppose ...

s,

Azariqa

The Azariqa ( ar, الأزارقة, ''al-azāriqa'') were an extremist branch of Khawarij, who followed the leadership of Nafi ibn al-Azraq al-Hanafi. Adherents of Azraqism participated in an armed struggle against the rulers of the Umayyad Cali ...

,

Najdat

The Najdat were the sub-sect of the Kharijite movement that followed Najda ibn 'Amir al-Hanafi, and in 682 launched a revolt against the Umayyad Caliphate in the historical provinces of Yamama and Bahrain, in central and eastern Arabia.

Among ...

,

Adjarites, and

Ibadis

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

. Of these, Ibadi Muslims are the only surviving branch of Kharijites. In addition to the aforementioned groups, new schools of thought and movements like

Ahmadi Muslims,

Quranist Muslims

Quranism ( ar, القرآنية, translit=al-Qurʾāniyya'';'' also known as Quran-only Islam) Brown, ''Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought'', 1996: p.38-42 is a movement within Islam. It holds the belief that traditional religious cl ...

, and

African-American Muslims later emerged independently.

Main branches or denominations

Sunnī Islam

Sunnī Islam, also known as ''Ahl as-Sunnah waʾl Jamāʾah'' or simply ''Ahl as-Sunnah'', is by far the largest

denomination of Islam, comprising around 85% of the Muslim population in the world. The term ''Sunnī'' comes from the word ''

sunnah'', which means the teachings, actions, and examples of the

Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

and

his companions (''ṣaḥāba'').

Sunnīs believe that Muhammad did not specifically appoint a successor to lead the

Muslim community

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

''(Ummah)'' before his death in 632 CE, however they approve of the private election of the first companion,

Abū Bakr. Sunnī Muslims regard the first four caliphs—

Abū Bakr (632–634),

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb (Umar І, 634–644),

ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish language, Turkish and Persian language, Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and nota ...

(644–656), and

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (656–661)—as ''

al-Khulafā'ur-Rāshidūn'' ("the Rightly-Guided Caliphs"). Sunnīs also believe that the position of caliph may be attained

democratically

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

, on gaining a majority of the votes, but after the Rashidun, the position turned into a hereditary

dynastic

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A d ...

rule because of the divisions started by the

Umayyads Umayyads may refer to:

*Umayyad dynasty, a Muslim ruling family of the Caliphate (661–750) and in Spain (756–1031)

*Umayyad Caliphate (661–750)

:*Emirate of Córdoba (756–929)

:*Caliphate of Córdoba

The Caliphate of Córdoba ( ar, خ ...

and others. After the fall of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in 1923, there has never been another caliph as widely recognized in the

Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

.

Followers of the classical Sunnī

schools of jurisprudence and ''

kalām

''ʿIlm al-Kalām'' ( ar, عِلْم الكَلام, literally "science of discourse"), usually foreshortened to ''Kalām'' and sometimes called "Islamic scholastic theology" or "speculative theology", is the philosophical study of Islamic doc ...

'' (rationalistic theology) on one hand, and

Islamists

Islamism (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern states and regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, economic and judicial terms, in accordance with what is c ...

and

Salafists

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three generat ...

such as

Wahhabis

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, and ...

and

Ahle Hadith, who follow a literalist reading of early Islamic sources, on the other, have laid competing claims to represent the "orthodox" Sunnī Islam. Anglophone Islamic currents of the former type are sometimes referred to as "traditional Islam".

Islamic modernism

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge" attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with modern values such as democracy, civil rights, rationality, ...

is an offshoot of the

Salafi movement that tried to integrate modernism into Islam by being partially influenced by modern-day attempts to revive the ideas of the

Muʿtazila school by Islamic scholars such as

Muhammad Abduh.

Shīʿa Islam

Shīʿa Islam is the second-largest denomination of Islam, comprising around 10–15%

[See:

*

*

* ] of the total Muslim population.

Although a minority in the Muslim world, Shīʿa Muslims constitute the majority of the Muslim populations in

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

,

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

,

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

,

Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

, and

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of t ...

, as well as significant minorities in

Syria,

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

,

South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth descr ...

,

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, and

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the fifth-largest country in Asia, the second-largest in the A ...

, as well as in other parts of the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

.

In addition to believing in the supreme authority of the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

and teachings of Muhammad, Shīʿa Muslims believe that Muhammad's family, the ''

Ahl al-Bayt'' ("People of the Household"), including his descendants known as

Imams

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, serve ...

, have distinguished spiritual and political authority over the community, and believe that

ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib, Muhammad's cousin and son-in-law, was the first of these Imams and the

rightful successor to Muhammad, and thus reject the legitimacy of the first three ''Rāshidūn'' caliphs.

Major sub-denominations

* The

Twelvers

Twelver Shīʿīsm ( ar, ٱثْنَا عَشَرِيَّة; '), also known as Imāmīyyah ( ar, إِمَامِيَّة), is the largest branch of Shīʿa Islam, comprising about 85 percent of all Shīʿa Muslims. The term ''Twelver'' refers t ...

believe in the

twelve Shīʿīte Imams and are the only school to comply with the

Hadith of the Twelve Successors

The Hadith of the Twelve Successors ( ar-at, حَدِيْث ٱلْإِثْنَي عَشَر خَلِيْفَة, ḥadīth al-ithnā ʿashar khalīfah) is a widely-reported prophecy, attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad, predicting that the ...

, where Muhammad stated that he would have twelve successors. This sometimes includes the

Alevi

Alevism or Anatolian Alevism (; tr, Alevilik, ''Anadolu Aleviliği'' or ''Kızılbaşlık''; ; az, Ələvilik) is a local Islamic tradition, whose adherents follow the mystical Alevi Islamic ( ''bāṭenī'') teachings of Haji Bektash Veli, w ...

and

Bektashi

The Bektashi Order; sq, Tarikati Bektashi; tr, Bektaşi or Bektashism is an Islamic Sufi mystic movement originating in the 13th-century. It is named after the Anatolian saint Haji Bektash Wali (d. 1271). The community is currently led by ...

schools.

*

Ismāʿīlīsm, including the

Nizārī

The Nizaris ( ar, النزاريون, al-Nizāriyyūn, fa, نزاریان, Nezāriyān) are the largest segment of the Ismaili Muslims, who are the second-largest branch of Shia Islam after the Twelvers. Nizari teachings emphasize independent ...

,

Sevener

al-Ismāʿīliyya al-khāliṣa / al-Ismāʿīliyya al-wāqifa or Seveners ( ar, سبعية) was a branch of Ismā'īlī Shīʻa. They broke off from the more numerous Twelvers after the death of Jafar al-Sadiq in 765 AD. They became known as " ...

,

Musta‘lī,

Dawudi Bohra,

Hebtiahs Bohra

The Hebtiahs Bohra are a branch of Mustaali Ismaili Shi'a Islam that broke off from the mainstream Dawoodi Bohra after the death of the 39th Da'i al-Mutlaq in 1754. They are mostly concentrated in Ujjain in India with a few families who are Heb ...

,

Sulaymani Bohra, and

Alavi Bohra

The Alavi Bohras are a Tayyibi Musta'lavi Isma'ili Shi'i Muslim community from Gujarat, India. In India, during the time of the 18th Fatimid Imam Al-Mustansir Billah around 1093 AD in Egypt, the designated learned people (''wulaat'') who w ...

sub-denominations.

* The

Zaydīs historically derive from the followers of

Zayd ibn ʿAlī. In the

modern era, they "survive only in northern

Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

".

Although they are a Shīʿa sect, "in modern times" they have "shown a strong tendency to move towards the Sunni mainstream".

[

* The ]Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isl ...

are a distinct monotheistic Abrahamic religion and ethno-religious group

An ethnoreligious group (or an ethno-religious group) is a grouping of people who are unified by a common religious and ethnic background.

Furthermore, the term ethno-religious group, along with ethno-regional and ethno-linguistic groups, is a s ...

that developed between the 9th and 10th centuries CE. Historically, Twelver Shīʿīte scholars such as Shaykh Tusi

Shaykh Tusi ( fa, شیخ طوسی), full name ''Abu Jafar Muhammad Ibn Hassan Tusi'' ( ar, ابو جعفر محمد بن حسن طوسی), known as Shaykh al-Taʾifah ( ar, links=no, شيخ الطائفة) was a prominent Persian scholar of the ...

didn't consider Alawites as Shīʿa Muslims while condemning their beliefs, perceived as heretical

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

. The medieval Sunnī Muslim scholar Ibn Taymiyyah also pointed out that the Alawites were not Shīʿītes.

* The Druze are a distinct monotheistic Abrahamic religion and ethno-religious group

An ethnoreligious group (or an ethno-religious group) is a grouping of people who are unified by a common religious and ethnic background.

Furthermore, the term ethno-religious group, along with ethno-regional and ethno-linguistic groups, is a s ...

that developed in the 11th century CE, originally as an offshoot of Ismāʿīlīsm.People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

), nor '' mushrikin'' (polytheists); rather, he labeled them as '' kuffār'' (infidels).

* The Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Established by Baháʼu'lláh in the 19th century, it initially developed in Iran and parts of the ...

is a distinct monotheistic universal

Universal is the adjective for universe.

Universal may also refer to:

Companies

* NBCUniversal, a media and entertainment company

** Universal Animation Studios, an American Animation studio, and a subsidiary of NBCUniversal

** Universal TV, a ...

Abrahamic religion that developed in 19th-century Persia, originally derived as a splinter group from Bábism

Bábism (a.k.a. the Bábí Faith; fa, بابیه, translit=Babiyye) is a religion founded in 1844 by the Báb (b. ʻAli Muhammad), an Iranian merchant turned prophet who taught that there is one incomprehensible God who manifests his will in ...

, another distinct monotheistic Abrahamic religion, itself derived from Twelver Shīʿīsm.Zoroaster

Zoroaster,; fa, زرتشت, Zartosht, label= Modern Persian; ku, زەردەشت, Zerdeşt also known as Zarathustra,, . Also known as Zarathushtra Spitama, or Ashu Zarathushtra is regarded as the spiritual founder of Zoroastrianism. He is ...

, Krishna

Krishna (; sa, कृष्ण ) is a major deity in Hinduism. He is worshipped as the eighth avatar of Vishnu and also as the Supreme god in his own right. He is the god of protection, compassion, tenderness, and love; and is one ...

, Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

, Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label= Hebrew/ Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

, Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

, the Báb

The Báb (b. ʿAlí Muḥammad; 20 October 1819 – 9 July 1850), was the messianic founder of Bábism, and one of the central figures of the Baháʼí Faith. He was a merchant from Shiraz in Qajar Iran who, in 1844 at the age of 25, claimed ...

, and ultimately Baháʼu'lláh).world religions

World religions is a category used in the study of religion to demarcate the five—and in some cases more—largest and most internationally widespread religious movements. Hinduism, Buddhism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are always includ ...

from the beginning of humankind up to the present day, and will continue to do so in the future.last prophet

The last prophet, or final prophet, is a term used in religious contexts to refer to the last person through whom God speaks, after which there is to be no other. The appellation also refers to the prophet who will induce mankind to turn back to G ...

, they have suffered religious discrimination

Religious discrimination is treating a person or group differently because of the particular beliefs which they hold about a religion. This includes instances when adherents of different religions, denominations or non-religions are treated u ...

and persecution both in Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and elsewhere in the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

due to their beliefs.Persecution of Baháʼís

Persecution of Baháʼís occurs in various countries, especially in Iran, where the Baháʼí Faith originated and where one of the largest Baháʼí populations in the world is located. The origins of the persecution stem from a variety of Ba ...

).

Ghulat movements

Shīʿīte groups and movements who either ascribe divine characteristics to some important figures in the history of Islam

The history of Islam concerns the political, social, economic, military, and cultural developments of the Islamic civilization. Most historians believe that Islam originated in Mecca and Medina at the start of the 7th century CE. Muslims re ...

(usually members of Muhammad's family, the '' Ahl al-Bayt'') or hold beliefs deemed deviant by mainstream Shīʿa Muslims were designated as ''Ghulat''.

Kharijite Islam

Kharijite (literally, "those who seceded") are an extinct sect who originated during the First Fitna, the struggle for political leadership over the Muslim community, following the assassination in 656 of the third caliph Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan ( ar, عثمان بن عفان, ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān; – 17 June 656), also spelled by Colloquial Arabic, Turkish and Persian rendering Osman, was a second cousin, son-in-law and notable companion of the Islamic prop ...

.Sufri

The Sufris ( ar, الصفرية ''aṣ-Ṣufriyya'') were Khariji Muslims in the seventh and eighth centuries. They established the Midrarid state at Sijilmassa, now in Morocco.

In Tlemcen, Algeria, the Banu Ifran were Sufri Berbers who oppose ...

s were a major sub-sect of Kharijite in the 7th and 8th centuries, and a part of the Kharijites. Nukkari

The Nukkari or simple Nukkar (also Nakkari or Nakkariyah; in Latin sources named Canarii) were one of the main branches of the North African Ibadi, founded in 784 by Abu Qudama Yazid ibn Fandin al- Ifrani. Led by Abu Yazid al-Nukkari, they rev ...

was a sub-sect of Sufris. Harūrīs were an early Muslim sect from the period of the Four Rightly-Guided Caliphs (632–661 CE), named for their first leader, Habīb ibn-Yazīd al-Harūrī. Azariqa

The Azariqa ( ar, الأزارقة, ''al-azāriqa'') were an extremist branch of Khawarij, who followed the leadership of Nafi ibn al-Azraq al-Hanafi. Adherents of Azraqism participated in an armed struggle against the rulers of the Umayyad Cali ...

, Najdat

The Najdat were the sub-sect of the Kharijite movement that followed Najda ibn 'Amir al-Hanafi, and in 682 launched a revolt against the Umayyad Caliphate in the historical provinces of Yamama and Bahrain, in central and eastern Arabia.

Among ...

, and Adjarites were minor sub-sects.

Ibadi Islam

The only Kharijite sub-sect extant today is Ibadism

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

, which developed out of the 7th century CE. There are currently two geographically separated Ibadi groups—in Oman

Oman ( ; ar, عُمَان ' ), officially the Sultanate of Oman ( ar, سلْطنةُ عُمان ), is an Arabian country located in southwestern Asia. It is situated on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, and spans the mouth of ...

, where they constitute the majority of the Muslim population in the country, and in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

where they constitute significant minorities in Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

, Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

, and Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Suda ...

. Similarly to another Muslim minority, the Zaydīs, "in modern times" they have "shown a strong tendency" to move towards the Sunnī branch of Islam.[

]

Schools of Islamic jurisprudence

Islamic schools of jurisprudence, known as ''

Islamic schools of jurisprudence, known as ''madhhab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within ''fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE a ...

'', differ in the methodology

In its most common sense, methodology is the study of research methods. However, the term can also refer to the methods themselves or to the philosophical discussion of associated background assumptions. A method is a structured procedure for br ...

they use to derive their rulings from the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

, ''ḥadīth'' literature, the '' sunnah'' (accounts of the sayings and living habits attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

during his lifetime), and the ''tafsīr'' literature (exegetical commentaries on the Quran).

Sunnī

Sunnī Islam contains numerous schools of Islamic jurisprudence (''fiqh'') and

Sunnī Islam contains numerous schools of Islamic jurisprudence (''fiqh'') and schools of Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding '' ʿaqīdah'' (creed). The main schools of Islamic Theology include the Qadariyah, Falasifa, Jahmiyya, Murji'ah, Muʿtazila, Bat ...

(''ʿaqīdah'').fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ...

''), Sunnism contains several schools of thought (''madhhab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within ''fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE a ...

''):Ẓāhirī

The Ẓāhirī ( ar, ظاهري, otherwise transliterated as ''Dhāhirī'') ''madhhab'' or al-Ẓāhirīyyah ( ar, الظاهرية) is a Sunnī school of Islamic jurisprudence founded by Dāwūd al-Ẓāhirī in the 9th century CE. It is char ...

school, founded by Dāwūd al-Ẓāhirī (9th century CE).ʿaqīdah

''Aqidah'' ( (), plural ''ʿaqāʾid'', also rendered ''ʿaqīda'', ''aqeeda'', etc.) is an Islamic term of Arabic origin that literally means "creed". It is also called Islamic creed and Islamic theology.

''Aqidah'' go beyond concise statem ...

''), Sunnism contains several schools of theology:Atharī

Atharī theology or Atharism ( ar, الأثرية: / , " archeological"), otherwise referred to as Traditionalist theology or Scripturalist theology, is one of the main Sunni schools of Islamic theology. It emerged as an Islamic scholarly mov ...

school, a scholarly movement that emerged in the late 8th century CE;

* the Ashʿarī school, founded by Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī (10th century CE);

* the Māturīdī school, founded by Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī (10th century CE).

The Salafi movement is a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

reform branch and/or revivalist movement within Sunnī Islam whose followers don't believe in strictly following one particular ''madhhab

A ( ar, مذهب ', , "way to act". pl. مَذَاهِب , ) is a school of thought within ''fiqh'' (Islamic jurisprudence).

The major Sunni Mathhab are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE a ...

''. They include the Wahhabi movement

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, a ...

, an Islamic doctrine and religious movement founded by Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab, and the modern Ahle Hadith movement, whose followers call themselves '' Ahl al-Ḥadīth''.

Shīʿa

In Shīʿa Islam, the major Shīʿīte school of jurisprudence is the Jaʿfari or Imāmī school,Usuli

Usulis ( ar, اصولیون, fa, اصولیان) are the majority Twelver Shi'a Muslim group. They differ from their now much smaller rival Akhbari group in favoring the use of ''ijtihad'' (i.e., reasoning) in the creation of new rules of ''fiq ...

school, which favors the exercise of '' ijtihad'', and the Akhbari school, which holds the traditions (''aḵbār'') of the Shīʿīte Imams to be the main source of religious knowledge. Minor Shīʿa schools of jurisprudence include the Ismāʿīlī

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-S ...

school ( Mustaʿlī- Fāṭimid Ṭayyibi Ismāʿīlīs) and the Zaydī school, both of which have closer affinity to Sunnī jurisprudence.[ Shīʿīte clergymen and ]jurists

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyses and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal qualification in law and often a legal practitioner. In the U ...

usually carry the title of '' mujtahid'' (i.e., someone authorized to issue legal opinions in Shīʿa Islam).

Ibadi

The ''fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ...

'' or jurisprudence of Ibadi

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

s is relatively simple. Absolute authority is given to the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

and ''ḥadīth'' literature; new innovations accepted on the basis of '' qiyas'' (analogical reasoning) were rejected as ''bid'ah

In Islam, bid'ah ( ar, بدعة; en, innovation) refers to innovation in religious matters. Linguistically, the term means "innovation, novelty, heretical doctrine, heresy".

In classical Arabic literature ('' adab''), it has been used as a for ...

'' (heresy) by the Ibadis. That differs from the majority of Sunnīs, but agrees with most Shīʿa schools and with the Ẓāhirī

The Ẓāhirī ( ar, ظاهري, otherwise transliterated as ''Dhāhirī'') ''madhhab'' or al-Ẓāhirīyyah ( ar, الظاهرية) is a Sunnī school of Islamic jurisprudence founded by Dāwūd al-Ẓāhirī in the 9th century CE. It is char ...

and early Ḥanbalī schools of Sunnism.

Schools of Islamic theology

''Aqidah

''Aqidah'' ( (), plural ''ʿaqāʾid'', also rendered ''ʿaqīda'', ''aqeeda'', etc.) is an Islamic term of Arabic origin that literally means " creed". It is also called Islamic creed and Islamic theology.

''Aqidah'' go beyond concise stat ...

'' is an Islamic term meaning " creed", doctrine, or article of faith. There have existed many schools of Islamic theology, not all of which survive to the present day. Major themes of theological controversies in Islam have included predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

and free will, the nature of the Quran, the nature of the divine attributes, apparent and esoteric

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas ...

meaning of scripture, and the role of dialectical reasoning

Dialectic ( grc-gre, διαλεκτική, ''dialektikḗ''; related to dialogue; german: Dialektik), also known as the dialectical method, is a discourse between two or more people holding different Opinion, points of view about a subject but wi ...

in the Islamic doctrine.

Sunni

Classical

''Kalām

''ʿIlm al-Kalām'' ( ar, عِلْم الكَلام, literally "science of discourse"), usually foreshortened to ''Kalām'' and sometimes called "Islamic scholastic theology" or "speculative theology", is the philosophical study of Islamic doc ...

'' is the Islamic philosophy

Islamic philosophy is philosophy that emerges from the Islamic tradition. Two terms traditionally used in the Islamic world are sometimes translated as philosophy—falsafa (literally: "philosophy"), which refers to philosophy as well as logic, ...

of seeking theological principles through dialectic. In Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, the word literally means "speech/words". A scholar of ''kalām'' is referred to as a ''mutakallim'' (Muslim theologian; plural ''mutakallimūn''). There are many schools of Kalam, the main ones being the Ashʿarī and Māturīdī schools in Sunni Islam.

=Ashʿarī

=

Ashʿarīsm is a school of theology founded by Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the 10th century. The Ashʿarīte view was that comprehension of the unique nature and characteristics of God were beyond human capability. Ashʿarī theology is considered one of the orthodox creeds of Sunni Islam alongside the Māturīdī theology.

=Māturīdī

=

Maturidi, Māturīdism is a school of theology founded by Abū Manṣūr al-Māturīdī in the 10th century, which is a close variant of the Ashʿarī school. Māturīdī theology is considered one of the orthodox creeds of Sunni Islam alongside the Ashʿarī theology,

Traditionalist theology

Traditionalist theology (Islam), Traditionalist theology, sometimes referred to as the Atharī school, derives its name from the word "tradition" as a translation of the Arabic word ''hadith'' or from the Arabic word ''athar'', meaning "narrations". The traditionalist creed is to avoid delving into extensive theological speculation. They rely on the Qur'an, the Sunnah, and sayings of the Sahaba, seeing this as the middle path where the attributes of Allah are accepted without questioning their nature (''Bi-la kaifa, bi-la kayf''). Ahmad ibn Hanbal is regarded as the leader of the traditionalist school of creed. The modern Salafi movement associates itself with the Atharī creed.

Muʿtazila

Muʿtazila, Muʿtazilite theology originated in the 8th century in Basra when Wasil ibn Ata left the teaching lessons of Hasan al-Basri after a theological dispute. He and his followers expanded on the logic and rationalism of Greek philosophy, seeking to combine them with Islamic doctrines and show that the two were inherently compatible. The Muʿtazilites debated philosophical questions such as whether Quranic createdness, the Qur'an was created or co-eternal with God, whether evil was created by God, the issue of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby G ...

versus Free will in theology#In Islamic thought, free will, whether God's attributes in the Qur'an were to be interpreted allegorically or literally, and whether sinning believers would have eternal punishment in Jahannam, hell.

Murji'ah

Murji'ah was a name for an early politico-religious movement which came to refer to all those who identified faith (''iman'') with belief to the exclusion of acts. Originating during the caliphates of Uthman and Ali, Murijites opposed the Kharijites, holding that only God has the authority to judge who is a true Muslim and who is not, and that Muslims should consider all other Muslims as part of the community.[Isutzu, Concept of Belief, p. 55-56.] Two major Murijite sub-sects were the were Karamiya and Sawbaniyya.

Qadariyyah

Qadariyyah is an originally derogatory term designating early Islamic theologians who asserted that humans possess free will, whose exercise makes them responsible for their actions, justifying divine punishment and absolving God of responsibility for evil in the world.[

]

Jabriyah

In direct contrast to the Qadariyyah, Jabriyah was an early islamic philosophical school based on the belief that humans are controlled by predestination, without having choice or free will. The Jabriya school originated during the Umayyad dynasty in Basra. The first representative of this school was Al-Ja'd ibn Dirham who was executed in 724.[Ибрагим, Т. К. и Сагадеев А. В. ал-Джабрийа // Ислам: энциклопедический словарь / отв. ред. С. М. Прозоров. — М. : Наука, ГРВЛ, 1991. — С. 57-58.] The term is derived from the Arabic root j-b-r, in the sense which gives the meaning of someone who is forced or coerced by destiny.

Jahmiyyah

Jahmis were the alleged followers of the early Islamic theologian Jahm bin Safwan who associated himself with Al-Harith ibn Surayj. He was an exponent of extreme determinism according to which a man acts only metaphorically in the same way in which the sun acts or does something when it sets.

Batiniyyah

The ''Batiniyyah, Bāṭiniyyah'' is a name given to an allegoristic type of scriptural interpretation developed among some Shia groups, stressing the ''Batin (Islam), bāṭin'' (inward, esoteric) meaning of texts. It has been retained by all branches of Isma'ilism and its Druze offshoot. Alevism, Bektashism and folk religion, Hurufis and Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isl ...

practice a similar system of interpretation.

Sufism

Sufism is Islam's Mysticism, mystical-Asceticism, ascetic dimension and is represented by schools or orders known as ''Tasawwufī-Ṭarīqah.'' It is seen as that aspect of Islamic teaching that deals with the purification of inner self. By focusing on the more spiritual aspects of religion, Sufis strive to obtain direct experience of God by making use of "intuitive and emotional faculties" that one must be trained to use.

The following list contains some notable Sufi orders:

* The Azeemiyya order was founded in 1960 by Qalandar Baba Auliya, also known as Syed Muhammad Azeem Barkhia.

* The Bektashi order was founded in the 13th century by the Islamic saint Haji Bektash Veli, and greatly influenced during its formulative period by the Hurufism, Hurufi Ali al-'Ala in the 15th century and reorganized by Balım Sultan in the 16th century. Because of its adherence to the Twelve Imams it is classified under Twelver Shia Islam.

* The Chishti order ( fa, چشتیہ) was founded by (Khawaja) Abu Ishaq Shami ("the Syrian"; died 941) who brought Sufism to the town of Chisht, some 95 miles east of Herat in present-day Afghanistan. Before returning to the Levant, Shami initiated, trained and deputized the son of the local Emir ''(Khwaja)'' Abu Ahmad Abdal (died 966). Under the leadership of Abu Ahmad's descendants, the ''Chishtiyya'' as they are also known, flourished as a regional mystical order. The founder of the Chishti Order in South Asia was Moinuddin Chishti.

* The Kubrawiya order was founded in the 13th century by Najmuddin Kubra in Bukhara in modern-day Uzbekistan.

* The Mevlevi order is better known in the West as the "whirling dervishes".

* Mouride is most prominent in Senegal and The Gambia, with headquarters in the holy city of Touba, Senegal.

* The Naqshbandi order was founded in 1380 by Baha-ud-Din Naqshband Bukhari. It is considered by some to be a "sober" order known for its silent dhikr (remembrance of God) rather than the vocalized forms of dhikr common in other orders. The Süleymancılar, Süleymani and Khalidiyya orders are offshoots of the Naqshbandi order.

* The Ni'matullahi order is the most widespread Sufi order of Persia today. It was founded by Shah Ni'matullah Wali (d. 1367), established and transformed from his inheritance of the Marufi, Ma'rufiyyah circle. There are several suborders in existence today, the most known and influential in the West following the lineage of Javad Nurbakhsh, who brought the order to the West following the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

* The Noorbakshia Islam, Noorbakshia order, also called Nurbakshia, claims to trace its direct spiritual lineage and chain (silsilah) to the Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad, through Ali, by way of Ali Al-Ridha. This order became known as Nurbakshi after Shah Syed Muhammad Nurbakhsh Qahistani, who was aligned to the Kubrawiya order.

* The Oveysi (or Uwaiysi) order claims to have been founded 1,400 years ago by Uwais al-Qarni from Yemen.

* The Qadiri order is one of the oldest Sufi Orders. It derives its name from Abdul-Qadir Gilani (1077–1166), a native of the Iranian province of Gīlān Province, Gīlān. The order is one of the most widespread of the Sufi orders in the Islamic world, and can be found in Central Asia, Turkey, Balkans and much of East and West Africa. The Qadiriyyah have not developed any distinctive doctrines or teachings outside of mainstream Islam. They believe in the fundamental principles of Islam, but interpreted through mystical experience. The Ba 'Alawiyya, Ba'Alawi order is an offshoot of Qadiriyyah.

* Senussi is a religious-political Sufi order established by Muhammad ibn Ali as-Senussi. As-Senussi founded this movement due to his criticism of the Egyptian ulema.

Later movements

African-American movements

Many Atlantic slave trade, slaves brought from Africa to the Western Hemisphere were Muslim slaves in the United States, Muslims,[Milton C. Sernett (1999). ''African American religious history: a documentary witness''. Duke University Press. pp. 499–501.] with a declared aim of "resurrecting" the spiritual, mental, social, and economic condition of the African American, black man and woman of America and the world.[ The Nation of Islam doesn't consider the Arabian Muhammad as the final prophet and instead regards Elijah Muhammad, successor of Wallace Fard Muhammad, as the true Messenger of Allah.][''Evolution of a Community'', WDM Publications, 1995.]

**Five-Percent Nation

Ahmadiyya Movement In Islam

The Ahmadiyya, Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam was founded in British India in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian, who claimed to be the promised Messiah ("Second Coming of Jesus in Islam, Christ"), the Mahdi awaited by the Muslims as well as a Prophethood (Ahmadiyya), "subordinate" prophet to the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Barelvi / Deobandi split

Sunni Muslims of the Indian subcontinent comprising present day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh who are overwhelmingly Hanafi by fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ar, فقه ) is Islamic jurisprudence. Muhammad-> Companions-> Followers-> Fiqh.

The commands and prohibitions chosen by God were revealed through the agency of the Prophet in both the Quran and the Sunnah (words, deeds, and ...

have split into two schools or movements, the Barelvi

The Barelvi movement ( ur, بَریلوِی, , ), also known as Ahl al-Sunnah wa'l-Jamaah (People of the Prophet's Way and the Community) is a Sunni revivalist movement following the Hanafi and Shafi'i school of jurisprudence, with strong Suf ...

and the Deobandi. While the Deobandi is revivalist in nature, the Barelvi are more traditional and inclined towards Sufism.

Gülen / Hizmet movement

The Gülen movement, usually referred to as the Hizmet movement, established in the 1970s as an offshoot of the Nur Movement and led by the Turkish Islamic scholar and preacher Fethullah Gülen in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

, Central Asia, and in other parts of the world, is active in education, with private schools and universities in over 180 countries as well as with many American charter schools operated by followers. It has initiated forums for interfaith dialogue.

Islamic modernism

Islamic modernism

Islamic modernism is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response to the Western cultural challenge" attempting to reconcile the Islamic faith with modern values such as democracy, civil rights, rationality, ...

, also sometimes referred to as "modernist Salafism", is a movement that has been described as "the first Muslim ideological response"[''Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World'', Thompson Gale (2004)]

Islamism

Islamism is a set of political Ideology, ideologies, derived from various Islamic fundamentalism, fundamentalist views, which hold that Islam is not only a religion but a political system that should govern the legal, economic and social imperatives of the state. Many Islamists do not refer to themselves as such and it is not a single particular movement. Religious views and ideologies of its adherents vary, and they may be Sunni Islamists or Shia Islamists depending upon their beliefs. Islamist groups include groups such as Al-Qaeda, the organizer of the September 11, 2001 attacks and perhaps the most prominent; and the Muslim Brotherhood, the largest and perhaps the oldest. Although violence is often employed by some organizations, most Islamist movements are nonviolent.

Muslim Brotherhood

The ''Al-Ikhwan Al-Muslimun'' (with Ikhwan brethren) or Muslim Brotherhood, is an organisation that was founded by Egyptian scholar Hassan al-Banna, a graduate of Dar al-Ulum. With its various branches, it is the largest Sunni movement in the Arab world, and an affiliate is often the largest opposition party in many Arab nations. The Muslim Brotherhood is not concerned with theological differences, accepting both, Muslims of any of the four Sunni schools of thought, and Shi'a Muslims. It is the world's oldest and largest Islamist group. Its aims are to re-establish the Caliphate and in the meantime, push for more Islamisation of society. The Brotherhood's stated goal is to instill the Qur'an and ''sunnah'' as the "sole reference point for... ordering the life of the Muslim family, individual, community... and state".

Jamaat-e-Islami

The ''Jamaat-e-Islami'' (or JI) is an Islamist political party in the Indian subcontinent. It was founded in Lahore, British India, by Abul A'la Maududi, Sayyid Abul Ala Maududi (with alternative spellings of last name Maudoodi) in 1941 and is Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan, the oldest religious party in Pakistan. Today, sister organizations with similar objectives and ideological approaches exist in India (Jamaat-e-Islami Hind), Bangladesh (Jamaat-e-Islami Bangladesh), Kashmir (Jamaat-e-Islami Kashmir), and Sri Lanka, and there are "close brotherly relations" with the Islamist movements and missions "working in different continents and countries", particularly those affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood (Akhwan-al-Muslimeen). The JI envisions an Islamic government in Pakistan and Bangladesh governing by Islamic law. It opposes Westernization—including secularization, capitalism, socialism, or such practices as interest based banking, and favours an Islamic economic order and Caliphate.

Hizb ut-Tahrir

''Hizb ut-Tahrir'' ( ar, حزب التحرير) (Translation: Party of Liberation) is an international, Pan-Islamism, pan-Islamist political organization which describes its ideology as Islam, and its aim the re-establishment of the Islamic Khilafah (Caliphate) to resume Islamic ways of life in the Muslim world. The caliphate would unite the Muslim community (''Ummah'')

Quranism

Quranist Islam, Quranism[Quranism#DWBRTMIT1996, Brown, ''Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought'', 1996: p.38-42] or Quraniyya ( ar, القرآنية; ''al-Qur'āniyya'') is a protestant branch of Islam. It holds the belief that Islam, Islamic guidance and law should only be based on the Qur'an, Quran, thus Criticism of Hadith, opposing the religious authority and authenticity of the hadith literature.[''al-Manar'' 12(1911): 693-99; cited in Juynboll, ''Authenticity'', 30; cited in Quranist Islam#DWBRTMIT1996, D.W. Brown, ''Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought'', 1996: p.120]

Liberal and progressive Islam

Liberalism and progressivism within Islam, Liberal Islam originally emerged out of the Islamic revival, Islamic revivalist movement of the 18th-19th centuries.

Mahdavia

Mahdavia, or Mahdavism, is a Mahdiist sect founded in late 15th century India by Syed Muhammad Jaunpuri, who declared himself to be the Muhammad al-Mahdi, Hidden Twelfth Imam of the Twelver Shia tradition. They follow many aspects of the Sunni doctrine. Zikri Mahdavis, or Zikris, are an offshoot of the Mahdavi movement.["Zikris (pronounced 'Zigris' in Baluchi) are estimated to number over 750,000 people. They live mostly in Makran and Las Bela in southern Pakistan, and are followers of a 15th-century mahdi, an Islamic messiah, called Nur Pak ('Pure Light'). Zikri practices and rituals differ from those of orthodox Islam... " Gall, Timothy L. (ed). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Culture & Daily Life: Vol. 3 – Asia & Oceania. Cleveland, OH: Eastword Publications Development (1998); p. 85 cited afte]

adherents.com

Non-denominational Islam

Non-denominational Muslims is an umbrella term that has been used for and by Muslims who do not belong to or do not self-identify with a specific Islamic denomination.

Tolu-e-Islam

Tolu-e-Islam (organization), Tolu-e-Islam ("Resurgence of Islam") is a non-denominational Muslim organization based in Pakistan, with members throughout the world.

Salafism and Wahhabism

''Ahle Hadith''

Ahl-i Hadith ( fa, اهل حدیث, ur, اہل حدیث: ) is a movement which emerged in the Indian subcontinent in the mid-19th century. Its followers call themselves ''Ahl al-Hadith'' and are considered to be a branch of the ''Salafi movement, Salafiyya'' school. Ahl-i Hadith is antithetical to various beliefs and mystical practices associated with folk Sufism. Ahl-i Hadith shares many doctrinal similarities with the Wahhabi movement

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, a ...

and hence often classified as being synonymous with the "Wahhabism#Definitions and etymology, Wahhabis" by its adversaries. However, its followers reject this designation, preferring to identify themselves as "Salafis".

''Salafiyya'' movement

The Salafi movement, ''Salafiyya'' movement is a conservative, ''Islah, Islahi'' (reform) movement within Sunni Islam that emerged in the second half of the 19th century and advocate a return to the traditions of the "devout ancestors" (''Salaf, Salaf al-Salih''). It has been described as the "fastest-growing Islamic movement"; with each scholar expressing diverse views across social, theological, and political spectrum. Salafis follow a doctrine that can be summed up as taking "a Islamic fundamentalism, fundamentalist approach to Islam, emulating the Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

and his earliest followers—''al-salaf al-salih'', the 'pious forefathers'....They reject religious innovation, or ''bidʻah'', and support the implementation of ''Sharia'' (Islamic law)."[ The Salafi movement is often divided into three categories: the largest group are the purists (or Political quietism in Islam, quietists), who avoid politics; the second largest group are the Islamism, militant activists, who get involved in politics; the third and last group are the Salafi jihadism, jihadists, who constitute a minority.]

Wahhabism

The Wahhabi movement

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, a ...

was founded and spearheaded by the Ḥanbalī scholar and theologian Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab,Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

and Hadith, ''Hadith'' literature, such as his main and foremost theological treatise, ''Kitāb at-Tawḥīd'' ( ar, كتاب التوحيد; "The Book of Oneness").Wahhabism

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, and ...

" and "Salafism" are sometimes evoked interchangeably, although the designation "Wahhabism#Definitions and etymology, Wahhabi" is specifically applied to the followers of Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab and his Islah, reformist doctrines.Muslim community

' (; ar, أمة ) is an Arabic word meaning "community". It is distinguished from ' ( ), which means a nation with common ancestry or geography. Thus, it can be said to be a supra-national community with a common history.

It is a synonym for ' ...

(''Ummah'') and criticized for its followers' Destruction of early Islamic heritage sites in Saudi Arabia, destruction of many Islamic, cultural, and historical sites associated with the early history of Islam

The history of Islam concerns the political, social, economic, military, and cultural developments of the Islamic civilization. Most historians believe that Islam originated in Mecca and Medina at the start of the 7th century CE. Muslims re ...

and the first generation of Muslims (Ahl al-Bayt, Muhammad's family and his Companions of the Prophet, companions) in Saudi Arabia.

Population of the branches

See also

* Amman Message

* Aqidah

''Aqidah'' ( (), plural ''ʿaqāʾid'', also rendered ''ʿaqīda'', ''aqeeda'', etc.) is an Islamic term of Arabic origin that literally means " creed". It is also called Islamic creed and Islamic theology.

''Aqidah'' go beyond concise stat ...

* Glossary of Islam

* Index of Islam-related articles

* International Islamic Unity Conference (Iran)

* Islamic eschatology

* Islamic studies

* Madhhab

* Outline of Islam

* Schools of Islamic theology

* Shia crescent

* Shia–Sunni relations

* Succession to Muhammad

References

External links

The Four Sunni Schools of Thought

{{Authority control

Islamic branches,

Religious denominations

The original schism between Kharijites, Sunnīs, and Shīʿas among

The original schism between Kharijites, Sunnīs, and Shīʿas among

Islamic schools of jurisprudence, known as ''

Islamic schools of jurisprudence, known as '' Sunnī Islam contains numerous schools of Islamic jurisprudence (''fiqh'') and

Sunnī Islam contains numerous schools of Islamic jurisprudence (''fiqh'') and