International Squadron (Cretan Intervention, 1897–1898) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The International Squadron was a naval

As early as May 1896, the British

As early as May 1896, the British

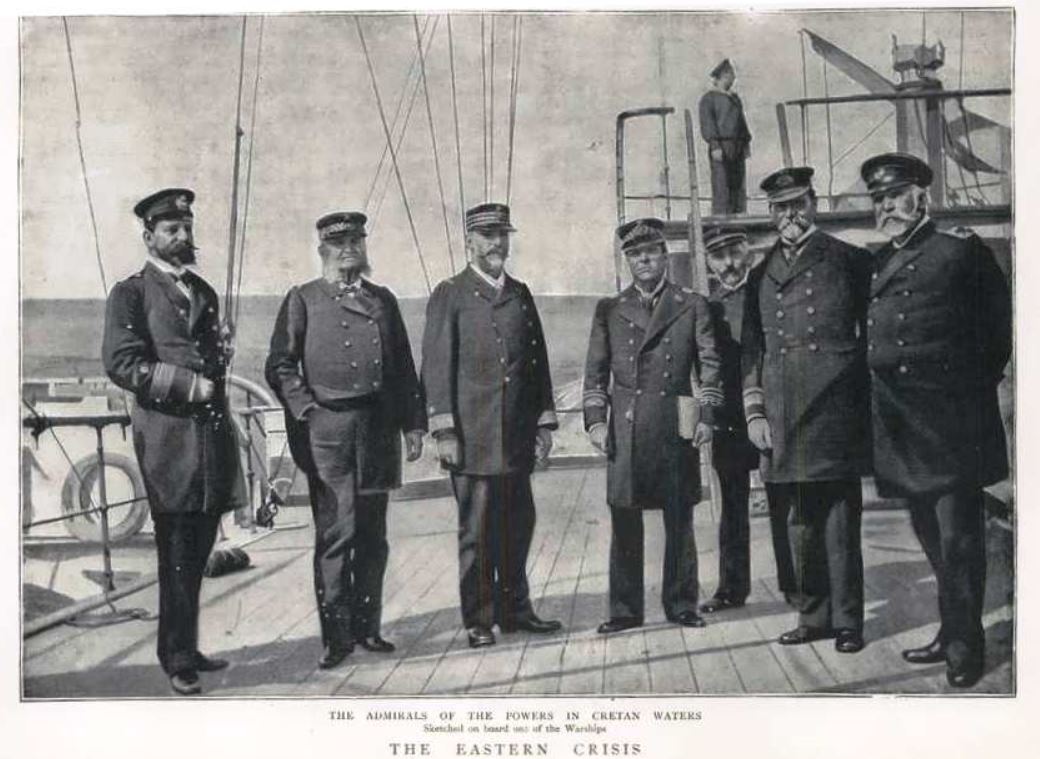

Vassos's declaration was a direct challenge to both the Ottoman Empire and the Great Powers, and Berovich's departure left Crete with no functioning civil authority. To address both matters, the International Squadron took its first direct action on 15 February 1897 by landing 450 sailors and marines – 100 each from France, Italy, Russia, and the United Kingdom and 50 from Austria-Hungary – from the warships anchored in the harbor at Canea and raising the flags of all six of the Great Powers over Canea. This began both the international occupation of Crete and the role of the International Squadron's admirals in managing the island's affairs via the Admirals Council. When the first Imperial German Navy warship, the protected cruiser , arrived off Crete on 21 February, she reinforced the International Squadron's occupying force ashore by landing an additional 50 men.McTiernan, p. 17. Meanwhile, the International Squadron determined that the senior admiral present among the contingents of all six countries should serve as the squadron's overall commander, and accordingly Italian Vice Admiral

Vassos's declaration was a direct challenge to both the Ottoman Empire and the Great Powers, and Berovich's departure left Crete with no functioning civil authority. To address both matters, the International Squadron took its first direct action on 15 February 1897 by landing 450 sailors and marines – 100 each from France, Italy, Russia, and the United Kingdom and 50 from Austria-Hungary – from the warships anchored in the harbor at Canea and raising the flags of all six of the Great Powers over Canea. This began both the international occupation of Crete and the role of the International Squadron's admirals in managing the island's affairs via the Admirals Council. When the first Imperial German Navy warship, the protected cruiser , arrived off Crete on 21 February, she reinforced the International Squadron's occupying force ashore by landing an additional 50 men.McTiernan, p. 17. Meanwhile, the International Squadron determined that the senior admiral present among the contingents of all six countries should serve as the squadron's overall commander, and accordingly Italian Vice Admiral

With the greatest threat to Canea appearing to come from the east, the International Squadron by 26 February had concentrated most of its ships in Suda Bay, east of Canea, where they could fire on insurgent forces holding the

With the greatest threat to Canea appearing to come from the east, the International Squadron by 26 February had concentrated most of its ships in Suda Bay, east of Canea, where they could fire on insurgent forces holding the

/ref> After the actions of late March 1897, the International Squadron and the various European military contingents ashore feared a major insurgent attack against the towns held by European forces, but none came; in fact, after the International Squadron's bombardments in late March, organized insurgent operations against Ottoman and European forces ended, with hostilities thereafter limited to occasional

With the military situation on the island quiet, the Admirals Council attempted to establish a working agreement between the insurgents and Ottoman forces on the island that would bring the revolt to an end without Ottoman forces having to leave Crete. This proved impossible. The Admirals Council then decided to resolve the situation by establishing a new, autonomous Cretan State that would run its own internal affairs but remain under the

With the military situation on the island quiet, the Admirals Council attempted to establish a working agreement between the insurgents and Ottoman forces on the island that would bring the revolt to an end without Ottoman forces having to leave Crete. This proved impossible. The Admirals Council then decided to resolve the situation by establishing a new, autonomous Cretan State that would run its own internal affairs but remain under the

After a tense night, reinforcements arrived in the form of the British battleship on 7 September, and she put a landing party of Royal Marines ashore. French, Italian, and Russian warships also arrived, and Austria-Hungary – although no longer a part of the International Squadron – sent the torpedo cruiser to the scene. The International Squadron put 300 French marines and Italian Mountain warfare, mountain troops from Canea ashore at Candia. British Army forces also began to flood into the town, and by 23 September 2,868 British troops were on hand.McTiernan, p. 35.

The International Squadron's senior British commander, Rear-Admiral Gerard Noel (Royal Navy officer), Gerard Noel, arrived at Candia aboard his

After a tense night, reinforcements arrived in the form of the British battleship on 7 September, and she put a landing party of Royal Marines ashore. French, Italian, and Russian warships also arrived, and Austria-Hungary – although no longer a part of the International Squadron – sent the torpedo cruiser to the scene. The International Squadron put 300 French marines and Italian Mountain warfare, mountain troops from Canea ashore at Candia. British Army forces also began to flood into the town, and by 23 September 2,868 British troops were on hand.McTiernan, p. 35.

The International Squadron's senior British commander, Rear-Admiral Gerard Noel (Royal Navy officer), Gerard Noel, arrived at Candia aboard his

McTiernan, Mick, ''A Very Bad Place Indeed For a Soldier. The British involvement in the early stages of the European Intervention in Crete. 1897 - 1898,'' King's College, London, September 2014.

{{DEFAULTSORT:International Squadron (Cretan intervention, 1897-1898) Greco-Turkish War (1897) Ottoman Crete Cretan State Multinational units and formations Military units and formations established in 1897 Military units and formations disestablished in 1898 Austro-Hungarian Navy History of the French Navy Naval history of Germany Imperial German Navy Military units and formations of the Imperial German Navy Naval history of Italy Regia Marina Imperial Russian Navy Naval units and formations of Russia 19th-century history of the Royal Navy History of the Royal Marines

squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, de ...

formed by a number of Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

in early 1897, just before the outbreak of the Greco-Turkish War of 1897

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

, to intervene in a native Greek rebellion on Crete against rule by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Warships from Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

made up the squadron, which operated in Cretan waters from February 1897 to December 1898.

The senior admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

from each country present off Crete became a member of an "Admirals Council" – also called the "Council of Admirals" and "International Council" – charged with managing the affairs of Crete, a role the admirals played until December 1898. The most senior admiral among those in Cretan waters served both as overall commander of the International Squadron and as the council's president. Initially, Italian Vice Admiral Felice Napoleone Canevaro

Felice Napoleone Canevaro (7 July 1838 – 30 December 1926) was an Italian admiral and politician and a Senate of the Kingdom of Italy, senator of the Kingdom of Italy. He served as both Minister of the Navy and Italian Minister of Foreign Affair ...

(1838–1926) served in these roles. When Canevaro left the International Squadron in mid-1898, French Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, equivalent to a major general and air vice marshal and above that of a commodore and captain, but below that of a vice admiral. It is regarded as a two star "admiral" rank. It is often regarde ...

Édouard Pottier (1839–1903) succeeded him as overall commander of the squadron and president of the council.

During the squadron's operations, it bombarded Crete, landed sailors and marines

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refle ...

on the island, blockaded both Crete and some ports in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, and supported international occupation forces on the island. After Austria-Hungary and Germany withdrew from the squadron, the other four powers continued its operations. After the squadron brought fighting on Crete to an end, its admirals attempted to negotiate a peace settlement, ultimately deciding that a new Cretan State should be established on the island under the suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

of the Ottoman Empire. The squadron completed its work in November and December 1898 by removing all Ottoman forces from the island and transporting Prince George of Greece and Denmark (1869–1957) to Crete to serve as High Commissioner of the new Cretan State, bringing direct Ottoman rule of the island to an end.

Background

In 1896, theGreat Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power in ...

induced the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

to agree to institute reforms in the administration of the island of Crete

Crete ( el, Κρήτη, translit=, Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and ...

Clowes, p. 444. – which the Ottomans had controlled since 1669Clowes, p. 448. – to protect the interests of the island's Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

population, with whom many people in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

sympathized. When the Ottomans failed to follow through on the reforms and massacred Christian inhabitants of Canea ( Chania), Crete, on 23–24 January 1897, a revolt broke out on 25 January 1897 among the Cretan Christians with a goal of forcing the union of Crete with Greece. With the support of Greek Army

The Hellenic Army ( el, Ελληνικός Στρατός, Ellinikós Stratós, sometimes abbreviated as ΕΣ), formed in 1828, is the land force of Greece. The term ''Hellenic'' is the endogenous synonym for ''Greek''. The Hellenic Army is the ...

troops deployed to the island and Greek Navy warships operating along its coast, the insurgents overran much of the countryside. Ottoman troops generally retained control of Crete's large towns and of isolated outposts scattered around the island.

Anxious to force the Ottomans to adhere to the agreement to institute the reforms promised in 1896 and to avoid a general war breaking out between Greece and the Ottoman Empire, which they feared would lead to an inevitable Greek defeat and might spread to become a general war in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, six Great Powers – Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

, and the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

– decided to intervene in the revolt so as to ensure that the reforms would take place. They placed pressure on the Ottomans not to reinforce their garrisons on Crete; in exchange, they took the responsibility for the general safety of the Ottoman garrisons already on the island.

Formation of the squadron

battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

and a French gunboat had arrived in Cretan waters to protect their countries′ interests and citizens in the face of unrest on Crete, and when major rioting broke out in Candia (now Heraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, Ηράκλειο, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Greece with a population of 211,370 (Urban A ...

) on 6 February 1897, men from the British warship on station, the battleship , intervened to bring the situation under control and to protect British subjects by bringing them aboard ''Barfleur''.McTiernan, p. 14. With the rapid deterioration of the situation on the island in early 1897, ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy

The Austro-Hungarian Navy or Imperial and Royal War Navy (german: kaiserliche und königliche Kriegsmarine, in short ''k.u.k. Kriegsmarine'', hu, Császári és Királyi Haditengerészet) was the naval force of Austria-Hungary. Ships of the A ...

, French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

, Italian Royal Navy (''Regia Marina

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the Italian constitutional referendum, 1946, birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' ch ...

''), Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

, and British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

all arrived in Crete's waters in early February 1897 as a show of naval might intended to demonstrate the commitment of the Great Powers to an end of fighting on Crete and an arrangement that would protect Christians on the island without separating it from the Ottoman Empire. The first British warships to join ''Barfleur'' – led by the battleships , the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of Rear-Admiral Robert Harris, and – arrived on 9 February 1897; by 13 February, Austro-Hungarian, French, Italian, and Russian warships had anchored off Crete and Germany had committed to establishing a naval presence there. Anchoring in the harbor at Canea (now Chania), the squadrons soon combined to form the International Squadron, and the admirals commanding the various national contingents began working together to address matters on the island.

Operations

Early actions

Greek intervention

While the six powers negotiated over what additional steps their naval forces off Crete should take, Greece took action to support the Cretan Christian insurgents. The Greek Navyironclad

An ironclad is a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by Wrought iron, iron or steel iron armor, armor plates, constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships ...

''Hydra

Hydra generally refers to:

* Lernaean Hydra, a many-headed serpent in Greek mythology

* ''Hydra'' (genus), a genus of simple freshwater animals belonging to the phylum Cnidaria

Hydra or The Hydra may also refer to:

Astronomy

* Hydra (constel ...

'' arrived off Crete in early February 1897, nominally to protect Greek interests and citizens on Crete, and on 12 February a Greek Navy squadron consisting of the steam sloop-of-war

In the 18th century and most of the 19th, a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy was a warship with a single gun deck that carried up to eighteen guns. The rating system covered all vessels with 20 guns and above; thus, the term ''sloop-of-war'' enc ...

''Sphacteria

Sphacteria ( el, Σφακτηρία - ''Sfaktiria'') also known as Sphagia (Σφαγία) is a small island at the entrance to the bay of Pylos in the Peloponnese, Greece. It was the site of three battles:

*the 425 BC Battle of Sphacteria in the ...

'' and four torpedo boats under the command of Prince George of Greece and Denmark (1869–1957) arrived at Canea with orders to support the Cretan insurrection and harass Ottoman shipping. The admirals of the International Squadron informed Prince George that they would use force if necessary to prevent any aggressive Greek actions in and around Crete, and Prince George's squadron departed Cretan waters on 13 February and steamed back to Greece. On the day that Prince George's squadron departed, the admirals received a report that Greek warships had chased and fired on an Ottoman steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

off Crete, and they informed the commander of the Greek Navy that they would not allow Greek ships to fire at Ottoman vessels in the island's waters. However, the situation continued to escalate on 14 February, when a Greek Army expeditionary force commanded by Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

Timoleon Vassos

Timoleon Vassos or Vasos ( el, Τιμολέων Βάσσος or Βάσος; 1836–1929) was a Hellenic Army officer and general.

He was born in Athens in 1836, the younger son of the hero of the Greek Revolution Vasos Mavrovouniotis. He studied a ...

(1836–1929) consisting of two battalions of Greek Army infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

– about 1,500 men – and two batteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

landed at Platanias

Platanias (Greek: ŒÝŒªŒ±œÑŒ±ŒΩŒπŒ¨œÇ) is a village and municipality on the Greek island of Crete. It is located about west from the city of Chania and east of Kissamos, on Chania Bay. The seat of the municipality is the village Gerani. Platania ...

, west of Canea; Vassos declared that his troops had come to occupy Crete on behalf of the King of Greece

The Kingdom of Greece was ruled by the House of Wittelsbach between 1832 and 1862 and by the House of Glücksburg from 1863 to 1924, temporarily abolished during the Second Hellenic Republic, and from 1935 to 1973, when it was once more abolishe ...

and unilaterally proclaimed Greece's annexation

Annexation (Latin ''ad'', to, and ''nexus'', joining), in international law, is the forcible acquisition of one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. It is generally held to be an illegal act ...

of Crete. This prompted the island's Ottoman '' vali'' (governor), George Berovich

George Berovich ( sr, Đorđe Berović, el, Γεώργιος Βέροβιτς, ''Georgios Verovits'', 1845–1897), known as Berovich Pasha ( tr, Beroviç Paşa) was a Christian Ottoman statesman who served as Governor-General (''wāli'') of Cret ...

(also known as Berovich Pasha) (1845–1897), to flee to Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

on 14 February aboard the Russian battleship '' Imperator Nikolai I''.McTiernan, p. 15.

Felice Napoleone Canevaro

Felice Napoleone Canevaro (7 July 1838 – 30 December 1926) was an Italian admiral and politician and a Senate of the Kingdom of Italy, senator of the Kingdom of Italy. He served as both Minister of the Navy and Italian Minister of Foreign Affair ...

– on the scene in command of a ''Regia Marina'' squadron consisting of the battleships ''Sicilia

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

'' (his flagship) and '' Re Umberto'', the protected cruiser ''Vesuvio

Mount Vesuvius ( ; it, Vesuvio ; nap, 'O Vesuvio , also or ; la, Vesuvius , also , or ) is a somma-stratovolcano located on the Gulf of Naples in Campania, Italy, about east of Naples and a short distance from the shore. It is one of s ...

'', and the torpedo cruiser ''Euridice

Eurydice (; Ancient Greek: Εὐρυδίκη 'wide justice') was a character in Greek mythology and the Auloniad wife of Orpheus, who tried to bring her back from the dead with his enchanting music.

Etymology

Several meanings for the name ...

'' – became the commander of the International Squadron on 16 or 17 February (sources vary); he also became president of the Admirals Council. The International Squadron ordered Vassos to come no closer than 6 kilometers (3 miles) to Canea, but he began operations intended to capture the town, leading to a clash on 19 February 1897 in which his expedition defeated a 4,000-man Ottoman force in the Battle of Livadeia. The International Squadron demanded that Vassos cease his operations against Canea and captured several storeship

Combat stores ships, or storeships, were originally a designation given to ships in the Age of Sail and immediately afterward that navies used to stow supplies and other goods for naval purposes. Today, the United States Navy and the Royal Nav ...

s sent to supply him.Clowes, p. 445.

February bombardments

While Vassos's troops advanced on Canea from the west, Cretan insurgents armed with artillery provided by the Greek Army advanced on Canea from the direction of Akrotiri to the east and took control of the high ground east of Canea. The insurgent force – which includedEleftherios Venizelos

Eleftherios Kyriakou Venizelos ( el, Ελευθέριος Κυριάκου Βενιζέλος, translit=Elefthérios Kyriákou Venizélos, ; – 18 March 1936) was a Greek statesman and a prominent leader of the Greek national liberation movem ...

(1864–1936), a future prime minister of Greece

The prime minister of the Hellenic Republic ( el, ŒÝœÅœâŒ∏œÖœÄŒøœÖœÅŒ≥œåœÇ œÑŒ∑œÇ ŒïŒªŒªŒ∑ŒΩŒπŒ∫ŒÆœÇ ŒîŒ∑ŒºŒøŒ∫œÅŒ±œÑŒØŒ±œÇ, Prothypourg√≥s tis Ellinik√≠s Dimokrat√≠as), colloquially referred to as the prime minister of Greece ( el, ŒÝœÅœâŒ∏œÖœ ...

– threatened to shell Canea and carried out unsuccessful attacks on the town on 13 and 14 February that Ottoman troops and Muslim '' Bashi-bazouk'' irregulars repelled. On 21 February 1897, the insurgents hoisted a Greek flag

The national flag of Greece, popularly referred to as the "blue and white one" ( el, Γαλανόλευκη, ) or the "sky blue and white" (, ), is officially recognised by Greece as one of its national symbols and has nine equal horizontal strip ...

over their position. When they ignored the International Squadron's order that day to take the flag down, disband, and disperse, Vice Admiral Canevaro ordered the squadron to bombard their positions, the squadron's first direct use of force. Although the French and Italian ships present were unable to participate because of other ships masking their fire, the British battleship HMS ''Revenge'' and torpedo gunboat

In late 19th-century naval terminology, torpedo gunboats were a form of gunboat armed with torpedoes and designed for hunting and destroying smaller torpedo boats. By the end of the 1890s torpedo gunboats were superseded by their more successful c ...

s and , the Russian battleship '' Imperator Aleksandr II'', the Austro-Hungarian armored cruiser , and the newly arrived German protected cruiser ''Kaiserin Augusta'' bombarded the insurgent positions, ''Revenge'' receiving credit for firing three 6-inch (152-mm) shells into the farmstead serving as the insurgent base of operations. The shelling – which, according to the insurgents consisted of as many as 100 rounds – prompted the insurgents to take the Greek flag down, and the warships ceased fire after five to ten minutes. The insurgents withdrew without shelling Canea, suffering three killed and a number wounded.McTiernan, p. 18. The insurgent Spiros Kayales became a Cretan hero when he grabbed the Greek flag after the International Squadron's gunfire had knocked it down twice and held it aloft himself. Cretan legend holds that Kayales's bravery so impressed the sailors of the International Squadron and aboard Greek ships offshore that cheers broke out aboard the French, Greek, and Italian warships anchored in the harbor; that Canevaro, seeing Kayales holding the flag up despite the shells bursting around him, ordered the ships to cease fire; and that the Admirals Council decided that Crete should have an autonomous government based on Kayales's actions. In fact, the closest ships were 4,700 yards (4,298 meters) away from the insurgent positions, too far for the insurgents to hear the cheers they reported from the warships, and the Admirals Council's eventual decision that Crete should have autonomy was based on international politics, their governments′ interests, and the state of negotiations with Cretan insurgent and Ottoman forces on the island rather than on any individual Cretan's bravery. Nonetheless, Cretans have celebrated Kayales's heroism every year on 9 February (the date of the incident on the Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

then in use on Crete, which during the 19th century was twelve days behind the modern Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

). Despite its success from a military standpoint, the "Bombardment of Akrotiri" and legend of Spyros Kayales had the deleterious effects on the Great Powers′ goals in Crete of further inflaming the nationalist passions of Cretan insurgents and misleading the island's Muslims into thinking that the International Squadron was operating in support of them rather than to prevent combat actions by either side.

Akrotiri Peninsula

The Akrotiri Peninsula is a short peninsula which includes the southernmost point of the island of Cyprus. It is bounded by Episkopi Bay to the west and Akrotiri Bay to the east and has two capes to the south-west and south-east, known as Cape Zev ...

. The squadron's men ashore also began patrols to keep the paved road between Canea and Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

open. On 28 February 1897, insurgent forces mounted their first attack on the Ottoman-held blockhouse

A blockhouse is a small fortification, usually consisting of one or more rooms with loopholes, allowing its defenders to fire in various directions. It is usually an isolated fort in the form of a single building, serving as a defensive stro ...

at Aptera on Malaxa Mountain Malaxa Mountain is a mountain at Malaxa on the island of Crete in the country of Greece. This mountain feature is situated in northwestern coastal Crete in the vicinity of the city of Chania. Trypali limestone is a dominant rock of Malaxa Mounta ...

overlooking Suda Bay; the blockhouse supported the Izzeddin Fortress, which in turn commanded the road. After receiving permission from the admirals of the International Squadron to shell the insurgents, the Ottoman Navy ironclad '' Mukaddeme-i Hayir'' fired three rounds, the first of which was particularly accurate, and her gunfire cleared the hillsides around the blockhouse of insurgents.

Kandanos expedition

Amid reports of massacres ofMuslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s by Christian insurgents on Crete, concern grew over the safety of the Ottoman garrison and Muslim inhabitants of Kandanos. Ships of the International Squadron, including the British battleship (with the British consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

at Canea, Alfred Biliotti

Sir Alfred Biliotti (14 July 1833 – 1915) was a levantine Italian who joined the British Foreign Service and eventually rose to become one of its most distinguished consular officers in the late 19th century. He was one of the first reporters ...

(1833–1915), aboard) arrived off Selino Kastelli (now Palaiochora

Palaiochora ( el, ŒÝŒ±ŒªŒ±ŒπœåœáœâœÅŒ± or ŒÝŒ±ŒªŒπœåœáœâœÅŒ±) is a small town in Chania regional unit, Greece. It is located 70 km south of Chania, on the southwest coast of Crete and occupies a small peninsula 400 m wide and 700 m long. Th ...

) in southwestern Crete on 5 March 1897. On 6 March an international landing force consisting of 200 British Royal Marines and sailors, 100 men each from Austro-Hungarian and French warships, 75 Russians, and 50 Italian sailors under the overall command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

John Harvey Rainier

Admiral John Harvey Rainier (29 April 1847 – 21 November 1915) was a Royal Navy officer. He had the unusual distinction of commanding troops from six different nations in action.

Background

Descended from the Huguenot family of Régnier, Jo ...

of ''Rodney'' came ashore and began an expedition to Kandanos, stopping at Spaniakos overnight and arriving at Kandanos on 7 March. The expedition departed Kandanos for the return journey on 8 March, bringing with it 1,570 civilians and 340 Ottoman soldiers from Kandanos and pausing during the day to pick up 112 more Ottoman troops from a fort at Spaniakos. Stopping for the night at Selino Kasteli, the expedition came under fire by Christian insurgents besieging two small Ottoman redoubts outside the village, but a Russian field gun

A field gun is a field artillery piece. Originally the term referred to smaller guns that could accompany a field army on the march, that when in combat could be moved about the battlefield in response to changing circumstances ( field artille ...

drove them off. The expedition relieved one of the redoubts overnight. On the morning of 9 March, Christian insurgents again opened fire, but the expedition's artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

ashore and gunfire by International Squadron warships in the bay silenced them. The expedition then mounted a bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

charge that relieved the second Ottoman redoubt, and the expeditionary force and the Ottoman soldiers and Muslim civilians it had rescued evacuated by sea. The expedition suffered no casualties among its European personnel or the Ottoman soldiers it rescued, and only one Muslim civilian was wounded during the four-day operation. The Christian insurgents lost four killed and 16 wounded.McTiernan, p. 19.

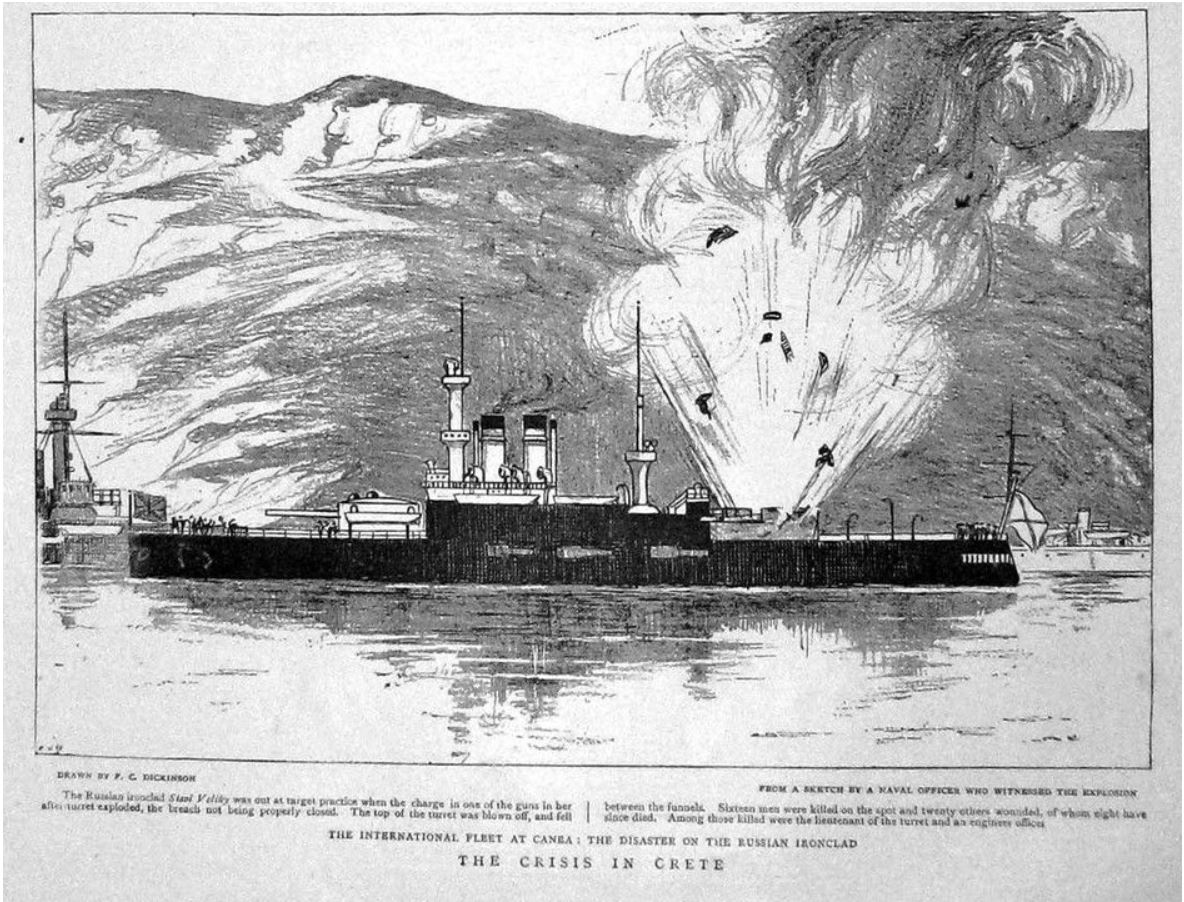

''Sissoi Veliky'' explosion

Tragedy struck the International Squadron on 15 March 1897 when the Russian battleship '' Sissoi Veliky'' suffered an explosion in her after 12-inch (305-mm) gun turret one hour into a routine target practice session off Crete that blew the roof of the turret over the mainmast; it struck the base of the foremast and crushed a steam cutter and a 37-millimeter gun. The explosion – which occurred after the turret crew disabled a malfunctioning safety mechanism, allowing one of the guns to fire before itsbreech

Breech may refer to:

* Breech (firearms), the opening at the rear of a gun barrel where the cartridge is inserted in a breech-loading weapon

* breech, the lower part of a pulley block

* breech, the penetration of a boiler where exhaust gases leav ...

was properly closed – killed 16 men instantly and injured 15, six of whom later died of their injuries. ''Sissoi Veliky'' steamed to Toulon

Toulon (, , ; oc, label= Provençal, Tolon , , ) is a city on the French Riviera and a large port on the Mediterranean coast, with a major naval base. Located in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region, and the Provence province, Toulon is th ...

, France, for repairs.

Blockade and occupation

On 17 March 1897, the Austro-Hungarian torpedo cruiser , patrolling to prevent Greek reinforcements and supplies from reaching Crete, intercepted a Greekschooner

A schooner () is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than the mainmast. A common variant, the topsail schoon ...

loaded with a cargo of munitions and manned by Cretan insurgents off Cape Dia, Crete. An exchange of gunfire followed in which ''Sebenico'' sank the schooner. The schooner's crew suffered no casualties and swam to shore on Crete.

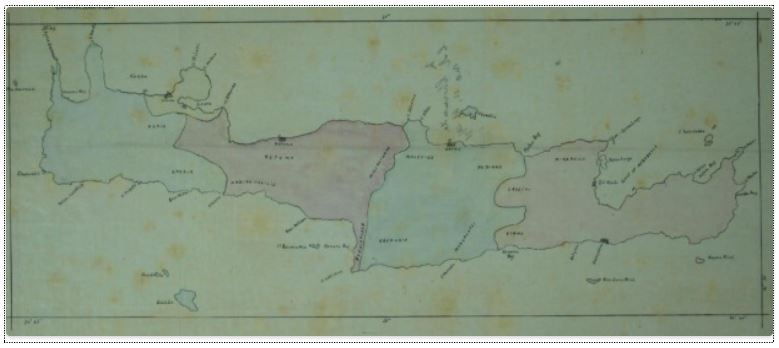

In the meantime, the Powers had directed the Admirals Council to develop a coercive plan to force Greece to withdraw its forces from Crete. The admirals' plan, announced on 18 March 1897, had two parts. One was the institution of a blockade of Crete and of the main ports in Greece, allowing no Greek ships to call at ports in Crete and permitting ships of other nationalities to unload their cargoes only at Cretan ports occupied by forces of the International Squadron; this blockade went into effect on 21 March 1897. Austria-Hungary took the responsibility for blockading Crete's western and extreme northwestern coast, Russia for much of the western portion of the north central coast, the United Kingdom for the eastern portion of the north central coast, France for the northeastern coast, and Italy for the southeastern coast, while the blockade of a portion of the northwestern coast and most of the southern coast was a shared, international responsibility. The other part of the plan called for the division of Crete into five sectors of occupation, with each of the six powers sending a battalion of troops from its army to the island to relieve the International Squadron's sailors and marines of occupation duties ashore. Germany, which was growing increasingly sympathetic toward the Ottoman Empire and opposed the limits on coercion of Greece the International Squadron recommended, refused to send troops, limiting its contribution to one ship (first ''Kaiserin Augusta'', later relieved by the ironclad coast defense ship

Coastal defence ships (sometimes called coastal battleships or coast defence ships) were warships built for the purpose of coastal defence, mostly during the period from 1860 to 1920. They were small, often cruiser-sized warships that sacrifi ...

) and the marines that the ship put ashore. However, troops of the Austro-Hungarian Army, British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, French Army

The French Army, officially known as the Land Army (french: Armée de Terre, ), is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces. It is responsible to the Government of France, along with the other components of the Armed For ...

, Italian Army

"The safeguard of the republic shall be the supreme law"

, colors =

, colors_labels =

, march = ''Parata d'Eroi'' ("Heroes's parade") by Francesco Pellegrino, ''4 Maggio'' (May 4) ...

, and Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: –Ý—ÉÃÅ—Å—Å–∫–∞—è –∏–º–ø–µ—Ä–∞ÃÅ—Ç–æ—Ä—Å–∫–∞—è –∞ÃÅ—Ä–º–∏—è, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

began landing in Crete to take up occupation duties in late March and early April 1897. By early April, about 2,500 troops of the five armies were ashore. The troops ashore came under the overall command of the Admirals Council, which instructed British Army Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Herbert Chermside

Lieutenant-general (United Kingdom), Lieutenant-General Sir Herbert Charles Chermside, (31 July 1850 – 24 September 1929) was a British Army officer who served as Governor of Queensland from 1902 to 1904.

Early life and education

Chermside wa ...

(1850–1929), the overall commander of the occupation forces ashore, that he should not base any of his troops beyond the range of the International Squadron's guns.

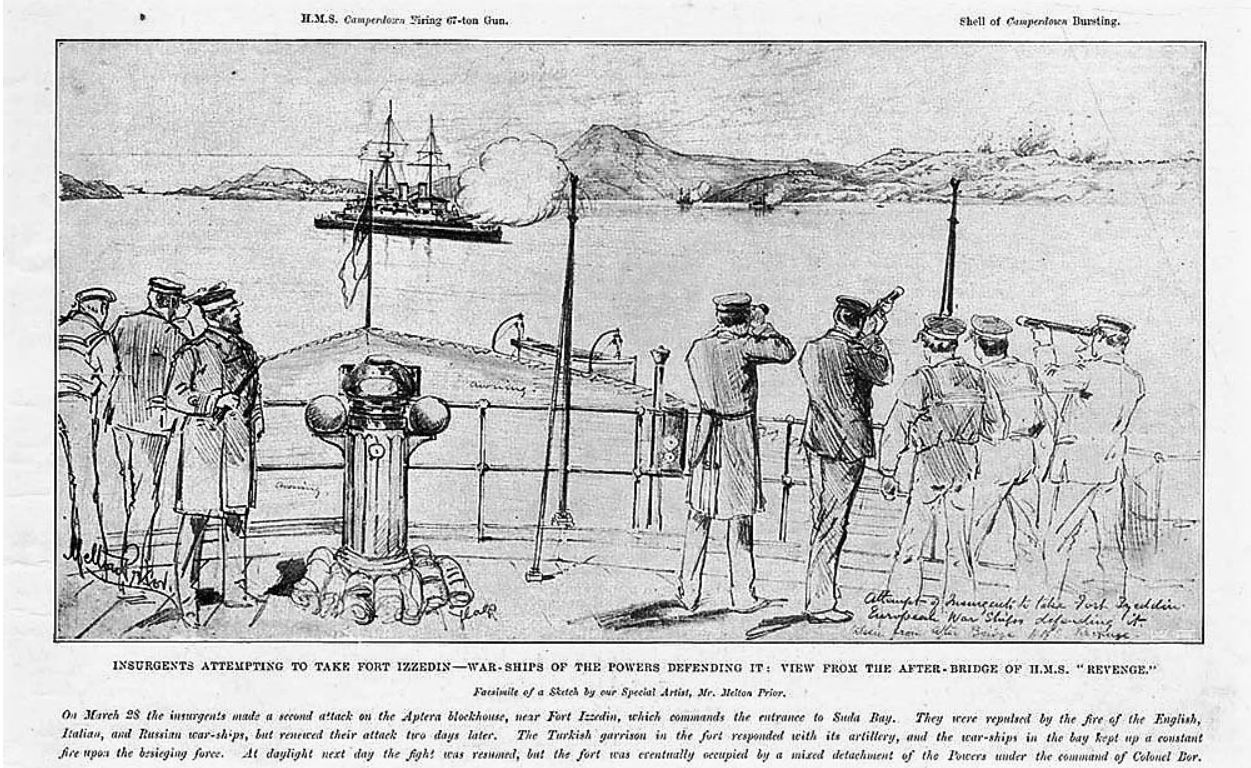

March bombardments

Just as the European soldiers were beginning to arrive on Crete, the insurgents renewed their attack on the Aptera blockhouse and captured it on 25 March 1897 despite shelling by Ottoman warships in Suda Bay. Immediately after the insurgents took the blockhouse, the smaller warships of the International Squadron fired about a hundred shells that landed on and around it, with one heavy shell from the Italian protected cruiser '' Giovanni Bausan'' penetrating the blockhouse's walls and exploding inside it, driving the insurgents back out. Some of the shells damaged the villages of Malaxa and Kontopoulo.Clowes, p. 446.McTiernan, p. 22. On 26 and 27 March, the British battleship , using her guns in anger for the first time in her history, opened fire at a range of 5,000 yards (4,572 meters) – including four 1,250-pound (567-kg) rounds from her 13.5-inch (343-mm) guns – on insurgents besieging the Izzeddin Fortress itself near the entrance to Suda Bay, forcing the insurgents to abandon theirsiege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

.McTiernan, p. 23. A contingent of Royal Marines

The Corps of Royal Marines (RM), also known as the Royal Marines Commandos, are the UK's special operations capable commando force, amphibious light infantry and also one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy. The Corps of Royal Marine ...

from the British battleship ''Revenge'' then landed and took control of the fort.

Other actions

While soldiers of the international force came ashore to take over occupation responsibilities from the sailors and marines of the International Squadron, the squadron continued to address threats by the insurgents ashore while adding support of those troops to its responsibilities on and around the island. During March, French marines landed on Crete and took the responsibility for assisting Ottoman troops in defending Fort Soubashi, 3 miles (5 km) southwest of Canea, against Greek Army and Christian insurgent forces; on 30 March, the French marines took part in an international expedition to protect a source of fresh water at the fort. In late March, the British battleship shelled insurgents attempting to mine the walls of the Ottoman fort atKastelli-Kissamos

Kissamos ( el, Κίσσαμος) is a town and a municipality in the west of the island of Crete, Greece. It is part of the Chania regional unit and of the former Kissamos Province which covers the northwest corner of the island. The town of Kissam ...

, driving them off, and the International Squadron landed 200 Royal Marines and 130 Austro-Hungarian sailors and marines to reprovision the fort and demolish nearby buildings that had provided cover for the mining effort. Elsewhere, the Italian battleship '' Ruggiero di Lauria'' broke up a threat by Cretan insurgents at Heraptera (now Ierapetra

Ierapetra ( el, Ιεράπετρα, lit=sacred stone; ancient name: ) is a Greece, Greek town and municipality located on the southeast coast of Crete.

History

The town of Ierapetra (in the local dialect: Γεράπετρο ''Gerapetro'') is loc ...

) by threatening to bombard them.treccani.it Gabriele, Mariano, "CANEVARO, Felice Napoleone," ''Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 18'', 1975./ref> After the actions of late March 1897, the International Squadron and the various European military contingents ashore feared a major insurgent attack against the towns held by European forces, but none came; in fact, after the International Squadron's bombardments in late March, organized insurgent operations against Ottoman and European forces ended, with hostilities thereafter limited to occasional

sniping

A sniper is a military/paramilitary marksman who engages targets from positions of concealment or at distances exceeding the target's detection capabilities. Snipers generally have specialized training and are equipped with high-precision r ...

. The International Squadron's admirals held a review of the troops of the international occupation force in Canea on 15 April 1897, presumably to impress the local inhabitants with the military power the Great Powers could bring to bear to enforce peace on the island. However, as late as 21 April 1897, the British battleship anchored off Canea – where Ottoman troops, Muslim civilians, and a force of British and Italian soldiers were besieged by an estimated 60,000 insurgents – to deter insurgents who had begun a demonstration with two artillery pieces that threatened the town.

Greco-Turkish War of 1897

Meanwhile, theGreco-Turkish War of 1897

The Greco-Turkish War of 1897 or the Ottoman-Greek War of 1897 ( or ), also called the Thirty Days' War and known in Greece as the Black '97 (, ''Mauro '97'') or the Unfortunate War ( el, Ατυχής πόλεμος, Atychis polemos), was a w ...

, also known as the Thirty Days War, had broken out on the mainland of Europe, with Greek forces crossing the border into Ottoman Macedonia

Macedonia most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a traditional geographic reg ...

on 24 March 1897, followed by an official declaration of war on 20 April. As the Great Powers had expected, the war ended quickly in a disastrous Greek defeat, and a ceasefire went into effect on 20 May 1897. Stymied by the International Squadron's actions and unable to advance beyond Fort Soubashi to threaten Canea or to receive reinforcements or supplies in the face of the blockade, Vassos, who had achieved little since February, accomplished nothing further during the war and left Crete on 9 May 1897. With the ceasefire agreement that ended hostilities on the European mainland requiring all Greek forces to leave Crete, his expeditionary force boarded the British protected cruiser at Platanias on 23 May 1897 and withdrew from the island. On 20 September 1897, Greece and the Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Constantinople, formally ending their war.

Seeking peace

Despite the events on the European mainland, the Christian insurrection on Crete continued. However, the military threat to the European Powers dropped so much after March 1897 that the International Squadron and the occupying forces ashore could turn their attention to ceremonial activities in the spring, such as a parade in honor of the Italian participation in the intervention on 4 May 1897 and a celebration of Queen Victoria′s Diamond Jubilee on 22 June 1897.suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

of the Ottoman Empire. Germany, increasingly sympathetic with the Ottoman Empire, disagreed strongly with this decision and withdrew from Crete and the International Squadron in November 1897.McTiernan, p. 28. Austria-Hungary also left in March 1898. Although the departures of German and Austro-Hungarian ships and troops weakened the International Squadron and the occupying forces, the four remaining Great Powers continued the blockade and occupation, dividing Crete into zones of responsibility among themselves. Italy took the responsibility for the western portion of the island, Russia the west-central portion, the United Kingdom the east-central part, and France the island's eastern area, while Canea and Suda Bay remained under joint, multinational control.

Having decided to establish the Cretan State, the Admirals Council turned its attention in the spring of 1898 to finding someone to serve as High Commissioner of the new state. They offered the position to Vice Admiral Canevaro, but he turned down the offer.McTiernan p. 29. and left the International Squadron to take office on 1 June 1898 as Italy's Minister of the Navy (Italy), Minister of the Navy. French Rear Admiral Édouard Pottier succeeded him in command of the squadron and as president of the Admirals Council, and the search for a high commissioner continued.

Meanwhile, by the spring of 1898, the Powers began to relax the blockade, reduce their presence in the International Squadron, and draw down their occupying forces ashore on Crete; for example, the British presence fell to one British Army battalion ashore and typically one battleship (usually anchored at Suda Bay), one cruiser, and one gunboat on station.McTiernan, p. 30. With the situation on Crete quiet, the British commander of forces on and around Crete, Rear Admiral (Royal Navy), Rear-Admiral Gerard Noel (Royal Navy officer), Gerard Noel (1845–1918) – who relieved Rear-Admiral Robert Harris (1843–1926) of this duty on 12 January 1898 – withdrew his flag from Crete and delegated his seat on the Admirals Council to whichever officer happened to be the British Senior Naval Officer at Crete at the time of each of the council's meetings, leading to frequent changes in British representation. For its part, the council began to loosen its formerly tight control over affairs on Crete, allowing greater autonomy in the decision-making of lower-ranking officers of the occupation force as they dealt with affairs on Crete. On 25 July 1898, the Admirals Council took the major step of turning over civil administration of Crete, except for the towns under international occupation, to the Christian Assembly, which was intended to become the legislative body of the Cretan State.

Candia riot

Cretan insurgents paid no taxes during the revolt and, with only the Muslim inhabitants of Cretan towns subject to taxation, financing of the administration of the island became increasingly difficult. Finally, the Admirals Council decided to place the customs houses on Crete under British control so that the British could exact an export Duty (economics), duty that would fund the general welfare of the island. They ordered the Ottomans to surrender the custom houses and made plans to replace Muslim officials and employees at the houses with Cretan Christians. Takeover of customs houses in Canea and Rethymno on 3 September 1898 took place without incident. When the British attempted to take control of the custom house at Candia (nowHeraklion

Heraklion or Iraklion ( ; el, Ηράκλειο, , ) is the largest city and the administrative capital of the island of Crete and capital of Heraklion regional unit. It is the fourth largest city in Greece with a population of 211,370 (Urban A ...

) on 6 September, however, violent resistance broke out among Muslim inhabitants, who believed that they were being forced to pay for a Christian takeover of their privileges. With only a 130-man detachment of the British Army's Highland Light Infantry ashore and the Royal Navy torpedo gunboat

In late 19th-century naval terminology, torpedo gunboats were a form of gunboat armed with torpedoes and designed for hunting and destroying smaller torpedo boats. By the end of the 1890s torpedo gunboats were superseded by their more successful c ...

the only warship present in the harbor, Muslim mobs confronted British officials, soldiers, and sailors at the harbor and the customs house, began a slaughter of Christian inhabitants, and opened a heavy fire on British military personnel at the harbor and not long afterward at the British encampment and hospital at the western end of the town. ''Hazard'' landed reinforcements and began to bombard the town in support of the beleaguered British forces ashore. Pressure on the British forces at the harbor gate became so severe that they withdrew to the water distillation ship SS ''Turquoise'' in the harbor.McTiernan, p. 32. The Muslims around the customs house and harbor did not cease fire until Ottoman troops led by the local Ottoman governor, Edhem Pasha (1851–1909), finally appeared late in the afternoon to restore order. When British forces at the camp and hospital fell back on the Ottoman fort west of town, Ottoman troops finally intervened there as well to quell the disturbance, which ended in the early evening. Ottoman forces otherwise made no effort to assist the British, protect Christian civilians, or keep order during the riot. Estimates of deaths during the day vary; the British suffered between 14 and 17 military personnel and at least three civilians killed and between 27 and 39 servicemen wounded, and Muslims slaughtered somewhere between 153 and nearly a thousand Christians, according to different sources.McTiernan, p. 34.Clowes, pp. 447-448.

flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

HMS ''Revenge'' – joined soon afterward by two more British warships, the battleship and the protected cruiser – on 12 September 1898. He disembarked immediately to inspect the scene of the riot personally, and ordered the Ottoman governor, Edhem Pasha, to meet him aboard ''Revenge'' on the morning of 13 September. At the meeting, Noel ordered Edhem Pasha to demolish all buildings from which rioters had fired on the British camp and hospital, disarm the entire Muslim population of the city, pay all customs duties due since 3 May 1898 and continue to pay them daily, and hand over the persons chiefly responsible for instigating the riot so that they could face trial; when Edhem Pasha refused, ''Camperdown'' and ''Revenge'' conducted a demonstration that overcame his reluctance. Ottoman officials met all of Noel's demands.McTiernan, p. 42.

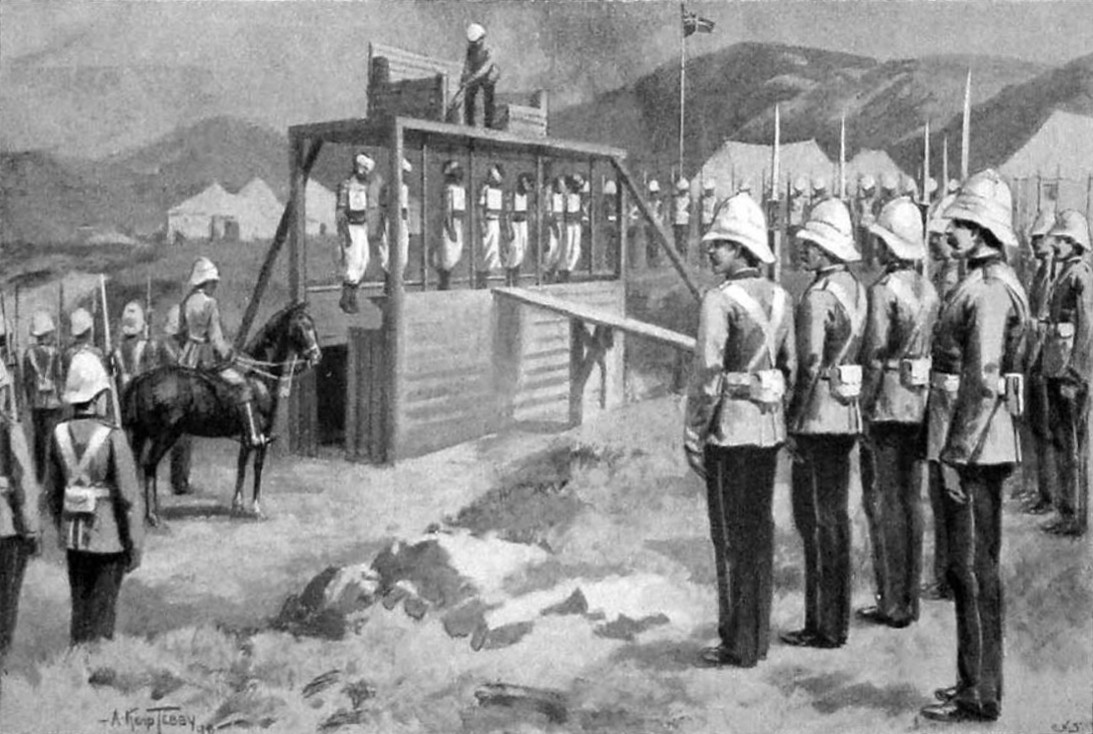

The British took custody of the first men accused of murder on 14 September and moved swiftly, trying those accused of killing British military personnel in Court martial, courts martial and those accused of killing British civilians before a British military tribunal. Twelve men were convicted of murdering British soldiers and five of murdering British civilians, and all 17 of the men were sentenced to death by hanging. Held aboard the British protected cruiser while awaiting their trials and executions, the men were hanged publicly in prominent locations. The first seven men convicted of murdering British military personnel were hanged on 18 October, and the final five on 29 October, and the five men convicted of murdering British civilians were hanged on 5 November.McTiernan, p. 43. Two men convicted under Italian jurisdiction of murdering Cretan civilians were executed by a firing squad composed of three men from each of the four powers. on 23 November, after which use of the death penalty for killers of Christian civilians was dropped.McTiernan, p. 54.

Evacuation of Ottoman forces

The Candia riot changed the International Squadron's attitude toward the situation on Crete: Previously it had viewed Christian insurgents as hostile and saw its primary role as supporting and protecting Ottoman forces, but the unhelpful behavior of Ottoman forces during the riot changed this, and thereafter the squadron saw the Ottomans as the hostile force. In the aftermath of the riot, the Admirals Council decided that all Christian and Muslim inhabitants had to be disarmed and all Ottoman forces had to leave Crete. The Ottomans stalled. The Great Powers' patience finally wore out on 4 October 1898, when they demanded that all Ottoman forces leave Crete by 19 October. Agreeing in principle to the evacuation of their forces, but objecting to the withdrawal timeline demanded by the Admirals Council and desirous of a small force of Ottoman troops remaining on Crete to guard the Flag of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman flag, the Ottomans continued to stall, but finally began to withdraw their forces from the island on 23 October. However, they halted the withdrawal on 28 October with about 8,000 Ottoman troops still on the island so as to avoid embarrassment of the Ottoman Empire during a visit of Germany's Wilhelm II of Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859–1941) to Constantinople. At the insistence of the British, in punishment for the delay in evacuation, the Admirals Council demanded that the Ottoman flag be hauled down in Canea – which it was, on 3 November – and that all Ottoman troops leave the island by 5 November; in the event of them failing to do so the Powers threatened to take steps to sink all Ottoman ships in Suda Bay and bombard and destroy the Izzeddrin Fortress, then expand bombardments to include Canea, Hieraptra, Spinalonga, Kissamos, and Rethymo, requiring the Ottoman government to pay Indemnity, indemnities for any damages resulting from these actions. The International Squadron and the occupying forces ashore developed plans for carrying out these threats; at Candia, for example, plans called for British forces ashore to withdraw to the coast with the support of Cretan Christian insurgent forces and embark aboard the ships of the International Squadron, after which the threatened bombardment would begin. The Ottomans responded by resuming the evacuation of their troops, but after the 5 November deadline passed, about 500 Ottoman troops remained in Candia. The British took administrative control of Candia on 5 November, so British troops evicted the remaining Ottoman troops from their barracks on 6 November 1898 and ensured that – supervised by officers and men of the British battleships and – the last Ottoman forces in Crete embarked on the British torpedo gunboat for transportation to Salonica. Their embarkation on ''Hussar'' brought 229 years of Ottoman occupation of Crete to an end.McTiernan, p. 36. However, a few Ottoman troops remained behind into December 1898 to supervise the withdrawal of Ottoman munitions and ordnance, and as late as December arguments broke out between the Ottomans and the occupying powers over such matters as how many Ottoman troops could remain behind and what military ranks they could hold. On 6 November 1898, with the last troops of the Ottoman garrison gone, the Admirals Council directed that the Ottoman flag be raised again. It took this step to indicate to Muslim Cretans that their rights would still be respected even without direct Ottoman rule of Crete.Transportation of Prince George

On 26 November 1898, the Admirals Council formally offered the position of High Commissioner of the Cretan State to Prince George of Greece and Denmark. Prince George accepted. With the last Ottoman forces gone from Crete, the International Squadron's final task was to arrange for Prince George's arrival on the island to take up his duties, marking the establishment of the new state. Complications arose over his transportation to Crete. He originally proposed that he would arrive aboard the Greek royal yacht, but the Admirals Council rejected this idea.McTiernan, p. 38. Greece proposed that a Greek Navy warship transport him to the island, but this idea did not meet with the approval of the International Squadron's admirals either. Greece then proposed that a Greek merchant ship flying theGreek flag

The national flag of Greece, popularly referred to as the "blue and white one" ( el, Γαλανόλευκη, ) or the "sky blue and white" (, ), is officially recognised by Greece as one of its national symbols and has nine equal horizontal strip ...

carry him to the island, but the four powers unanimously rejected this idea as well. Finally, the Admirals Council informed Prince George that the International Squadron would bring him to Crete, with a European warship flying her own national flag carrying him, escorted by warships of the other three powers flying their own national flags.

Prince George's arrival suffered a last-minute delay when an argument broke out among the four powers over the design of the flag of the new Cretan State. After the new flag's design met with the approval of all four powers, the four flagships of the countries making up the International Squadron – the French protected cruiser ''French cruiser Bugeaud, Bugeaud'' with the International Squadron's senior commander, Vice Admiral Édouard Pottier, aboard; the Italian battleship ''Italian ironclad Francesco Morosini, Francesco Morosini'', carrying the admiral commanding the squadron's Italian ships; the Russian armored cruiser ''Russian cruiser Gerzog Edinburgski, Gerzog Edinburgski'' with the senior Russian commander, Rear Admiral Nikolai Skrydlov, aboard; and the British battleship with the British commander, Rear Admiral Gerard Noel (Royal Navy officer), Gerard Noel, aboard – finally steamed on 19 December 1898 to Milos, where Prince George awaited them on his yacht. He boarded ''Bugeaud'' on 20 December. Escorted by the other three flagships, ''Bugeaud'' took him to Suda

The ''Suda'' or ''Souda'' (; grc-x-medieval, Σοῦδα, Soûda; la, Suidae Lexicon) is a large 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia of the ancient Mediterranean world, formerly attributed to an author called Soudas (Σούδας) or Souidas ...

, where he disembarked on 21 December 1898 to take up duties as High Commissioner of the new Cretan State. His arrival on the island brought 229 years of direct Ottoman rule of Crete – as well as ''de facto'' control of the island by the Admirals Council – to an end.McTiernan, p. 39.

On 26 December 1898, the Admirals Council formally was dissolved. Its duties completed, the International Squadron dispersed.

Legacy

The Cretan State, created by the decisions of the International Squadron's admirals as they negotiated the status of Crete on behalf of their governments, existed until 1913. Foreign troops continued to garrison the island until 1909, and Royal Navy ships remained on station there until 1913. In 1913, after the Greek victory in the Second Balkan War, Greece formally annexed Crete in the Treaty of Athens.See also

* Cretan State * Cretan Turks * History of Crete * Ottoman CreteReferences

External links

*Bibliography

* Clowes, Sir William Laird. ''The Royal Navy: A History From the Earliest Times to the Death of Queen Victoria, Volume Seven''. London: Chatham Publishing, 1997. .McTiernan, Mick, ''A Very Bad Place Indeed For a Soldier. The British involvement in the early stages of the European Intervention in Crete. 1897 - 1898,'' King's College, London, September 2014.

{{DEFAULTSORT:International Squadron (Cretan intervention, 1897-1898) Greco-Turkish War (1897) Ottoman Crete Cretan State Multinational units and formations Military units and formations established in 1897 Military units and formations disestablished in 1898 Austro-Hungarian Navy History of the French Navy Naval history of Germany Imperial German Navy Military units and formations of the Imperial German Navy Naval history of Italy Regia Marina Imperial Russian Navy Naval units and formations of Russia 19th-century history of the Royal Navy History of the Royal Marines