The

Democratic Party Democratic Party most often refers to:

*Democratic Party (United States)

Democratic Party and similar terms may also refer to:

Active parties Africa

*Botswana Democratic Party

*Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea

*Gabonese Democratic Party

*Demo ...

is one of the two major political parties of the

United States political system and the oldest existing

political party in that country founded in the 1830s and 1840s.

It is also the oldest voter-based

political party

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular country's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific political ideology ...

in the world. The party has changed significantly during its nearly two centuries of existence.

Known as the party of the "common man," the early Democratic Party stood for individual rights and state sovereignty, and opposed banks and high tariffs.

In the first decades of its existence, from 1832 to the mid-1850s (known as the

Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

), under Presidents

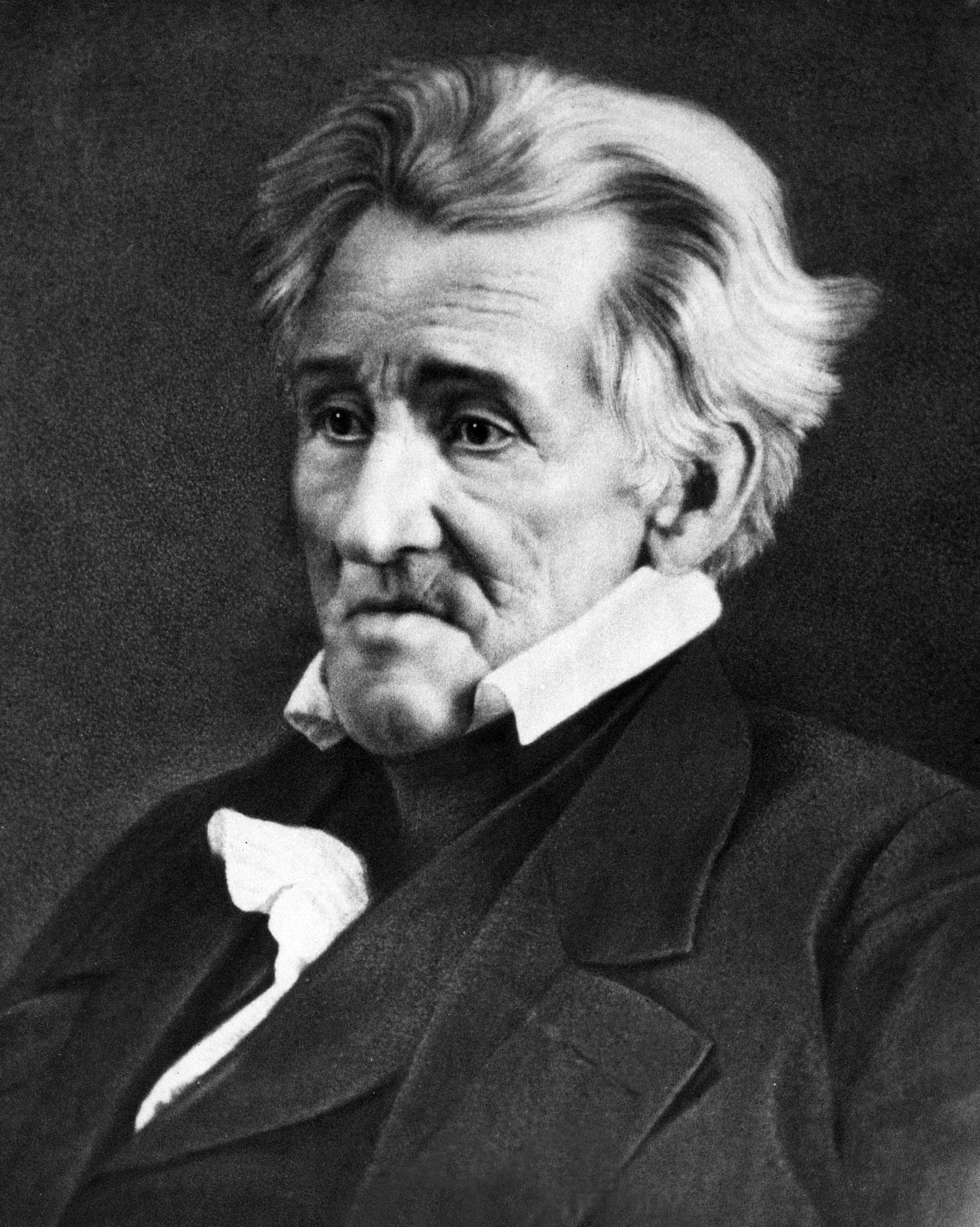

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

,

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

and

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

, the Democrats usually bested the opposition

Whig Party by narrow margins.

Before the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

the party supported or tolerated slavery; and after the war until the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

the party opposed civil rights reforms in order to retain the support of Southern voters. During this second period (1865-1932), the opposing

Republican Party, (organized in the mid-1850s from the ruins of the Whig Party and some other smaller splinter groups), was dominant in

presidential politics. The Democrats elected

only two Presidents during this period:

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

(in 1884 and 1892) and

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

(in 1912 and 1916). Over the same period, the Democrats proved more competitive with the Republicans in

Congressional politics, enjoying

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

majorities (as in the

65th Congress

The 65th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, composed of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, DC from March 4, 1917, to ...

) in 15 of the 36

Congresses elected, although only in five of these did they form the majority in the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. Furthermore, the Democratic Party was split between the

Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

s, representing Eastern business interests; and the agrarian elements comprising poor farmers in the South and West. The agrarian element, marching behind the slogan of

free silver (i.e. in favor of inflation), captured the party in 1896 and nominated

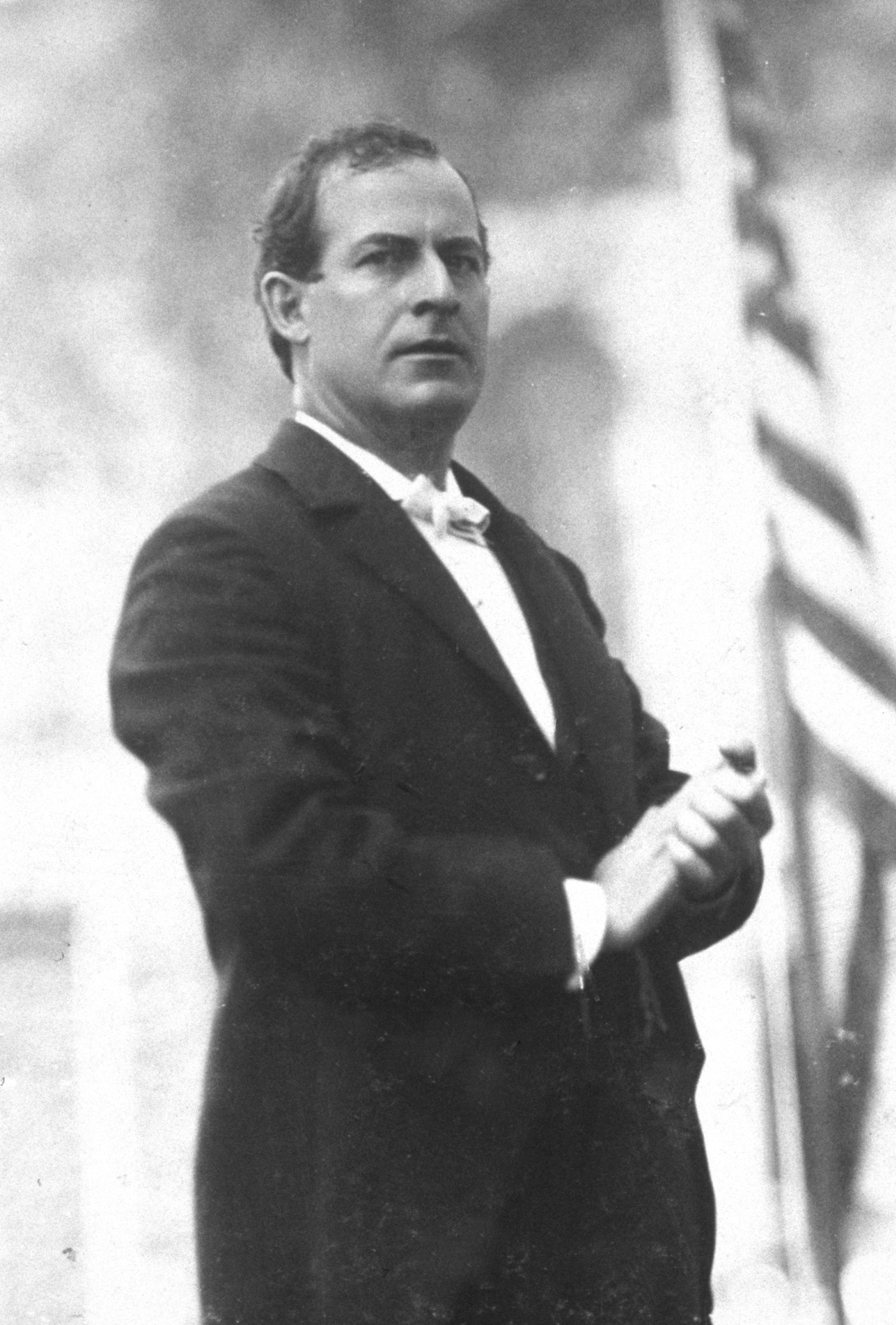

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

in the 1896, 1900 and 1908 presidential elections, although he lost every time. Both Bryan and Wilson were leaders of the

progressive movement in the United States (1890s–1920s) and opposed imperialistic expansion abroad while sponsoring liberal reforms at home.

Starting with 32nd President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

, the party dominated during the

Fifth Party System

The Fifth Party System is the era of American national politics that began with the New Deal in 1932 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt. This era of Democratic Party-dominance emerged from the realignment of the voting blocs and interest gro ...

, which lasted from 1932 until about the 1970s. In response to the

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929, also known as the Great Crash, was a major American stock market crash that occurred in the autumn of 1929. It started in September and ended late in October, when share prices on the New York Stock Exchange colla ...

and the ensuing

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, the party employed

liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

policies and programs with the

New Deal coalition to combat financial crises and emergency bank closings, with policies continuing into

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The Party kept the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

after Roosevelt's death in April 1945, reelecting former Vice President

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

in 1948. During this period, the

Republican Party only elected one president (Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956) and was the minority in Congress all but twice (the exceptions being 1946 and 1952). Powerful committee chairmanships were awarded automatically on the basis of seniority, which gave power especially to long-serving Southerners. Important Democratic leaders during this time included Presidents Harry S. Truman (1945–1953),

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

(1961–1963) and

Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

(1963–1969). Republican

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

won the White House in 1968 and 1972, leading to the end of the New Deal era.

Democrats have won six out of the last twelve presidential elections, winning in the presidential elections of

1976

Events January

* January 3 – The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights enters into force.

* January 5 – The Pol Pot regime proclaims a new constitution for Democratic Kampuchea.

* January 11 – The 1976 Phila ...

(with 39th President

Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he previously served as th ...

, 1977–1981),

1992

File:1992 Events Collage V1.png, From left, clockwise: 1992 Los Angeles riots, Riots break out across Los Angeles, California after the Police brutality, police beating of Rodney King; El Al Flight 1862 crashes into a residential apartment buildi ...

and

1996 (with 42nd President

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

, 1993–2001),

2008 and

2012

File:2012 Events Collage V3.png, From left, clockwise: The passenger cruise ship Costa Concordia lies capsized after the Costa Concordia disaster; Damage to Casino Pier in Seaside Heights, New Jersey as a result of Hurricane Sandy; People gather ...

(with 44th President

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

, 2009–2017), and

2020

2020 was heavily defined by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to global Social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, social and Economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic disruption, mass cancellations and postponements of events, COVID- ...

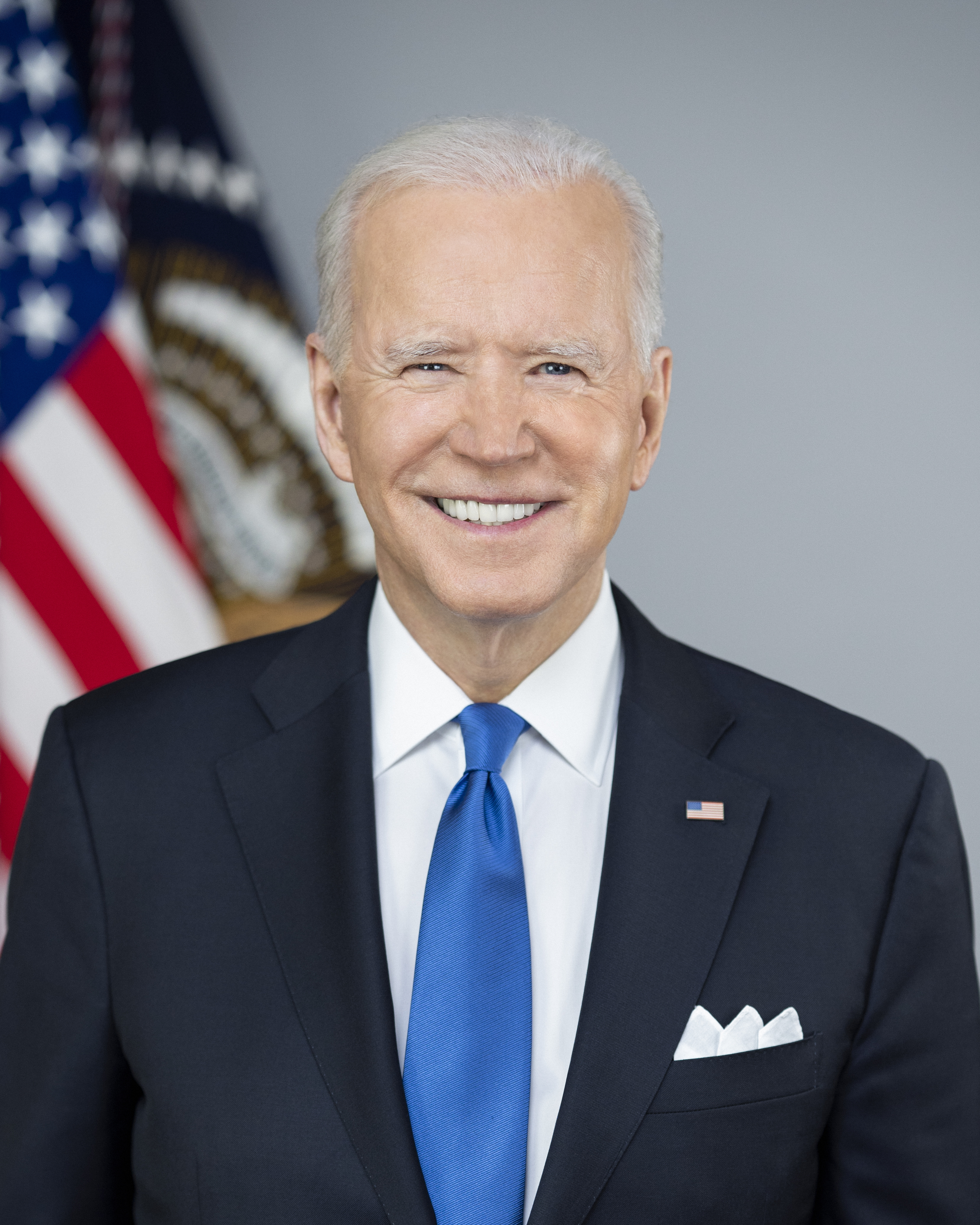

(with 46th President

Joe Biden, 2021–present). Democrats have also won the

popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the total ...

in

2000

File:2000 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Protests against Bush v. Gore after the 2000 United States presidential election; Heads of state meet for the Millennium Summit; The International Space Station in its infant form as seen from ...

and

2016, but lost the

Electoral College in both elections (with candidates

Al Gore

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (born March 31, 1948) is an American politician, businessman, and environmentalist who served as the 45th vice president of the United States from 1993 to 2001 under President Bill Clinton. Gore was the Democratic Part ...

and

Hillary Clinton

Hillary Diane Rodham Clinton ( Rodham; born October 26, 1947) is an American politician, diplomat, and former lawyer who served as the 67th United States Secretary of State for President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2013, as a United States sen ...

, respectively). These were two of the four

presidential elections in which Democrats won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College, the others being the presidential elections in

1876 and

1888.

Foundation: 1820-1828

The modern Democratic Party emerged in the late 1820s from former factions of the

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, which had largely collapsed by 1824. It was built by

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

, who assembled a cadre of politicians in every state behind war hero

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

of Tennessee. The pattern and speed of formation differed from state to state. By the mid-1830s almost all the state Democratic parties were uniform.

Jacksonian ascendancy: 1829–1840

Presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837)

The spirit of

Jacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, And ...

animated the party from the early 1830s to the 1850s, shaping the

Second Party System

Historians and political scientists use Second Party System to periodize the political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to 1852, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising levels ...

, with the

Whig Party as the main opposition. After the disappearance of the

Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

after 1815 and the

Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fed ...

(1816–1824), there was a hiatus of weakly organized personal factions until about 1828–1832, when the modern Democratic Party emerged along with its rival, the Whigs. The new Democratic Party became a coalition of farmers, city-dwelling laborers and Irish Catholics. Both parties worked hard to build

grassroots

A grassroots movement is one that uses the people in a given district, region or community as the basis for a political or economic movement. Grassroots movements and organizations use collective action from the local level to effect change at t ...

organizations and maximize the turnout of voters, which often reached 80 percent or 90 percent of eligible voters. Both parties used

patronage

Patronage is the support, encouragement, privilege, or financial aid that an organization or individual bestows on another. In the history of art, arts patronage refers to the support that kings, popes, and the wealthy have provided to artists su ...

extensively to finance their operations, which included emerging big city

political machine

In the politics of Representative democracy, representative democracies, a political machine is a party organization that recruits its members by the use of tangible incentives (such as money or political jobs) and that is characterized by a hig ...

s as well as national networks of newspapers.

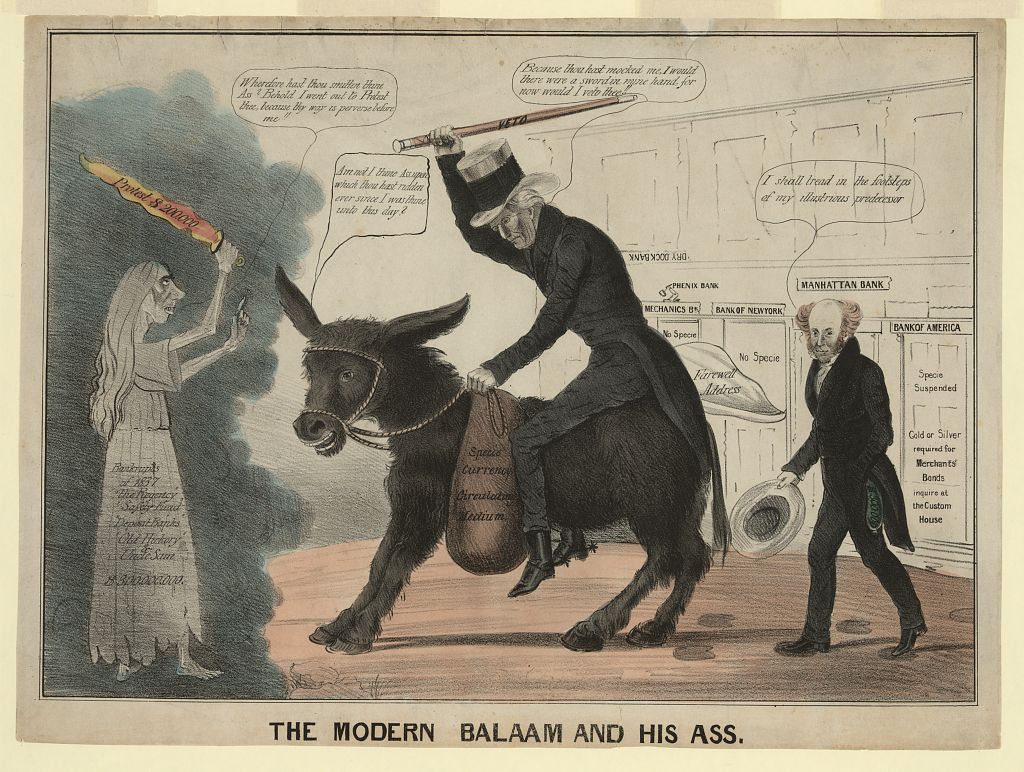

Behind the party platforms, acceptance speeches of candidates, editorials, pamphlets and

stump speeches, there was a widespread consensus of political values among Democrats. As Mary Beth Norton explains:

The Democrats represented a wide range of views but shared a fundamental commitment to the Jeffersonian concept of an agrarian society

An agrarian society, or agricultural society, is any community whose economy is based on producing and maintaining crops and farmland. Another way to define an agrarian society is by seeing how much of a nation's total production is in agriculture ...

. They viewed the central government as the enemy of individual liberty. The 1824 " corrupt bargain" had strengthened their suspicion of Washington politics. ..Jacksonians feared the concentration of economic and political power. They believed that government intervention in the economy benefited special-interest groups and created corporate monopolies that favored the rich. They sought to restore the independence of the individual – the artisan and the ordinary farmer – by ending federal support of banks and corporations and restricting the use of paper currency

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

, which they distrusted. Their definition of the proper role of government tended to be negative, and Jackson's political power was largely expressed in negative acts. He exercised the veto more than all previous presidents combined. Jackson and his supporters also opposed reform as a movement. Reformers eager to turn their programs into legislation called for a more active government. But Democrats tended to oppose programs like educational reform

Education reform is the name given to the goal of changing public education. The meaning and education methods have changed through debates over what content or experiences result in an educated individual or an educated society. Historically, th ...

and the establishment of a public education system....Nor did Jackson share reformers' humanitarian concerns. He had no sympathy for American Indians, initiating the removal of the Cherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

s along the Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

.

The party was weakest in

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, but strong everywhere else and won most national elections thanks to strength in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia (by far the most populous states at the time) and the

American frontier

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of United States territorial acquisitions, American expansion in mainland North Amer ...

. Democrats opposed elites and aristocrats, the

Bank of the United States and the whiggish modernizing programs that would build up industry at the expense of the

yeoman

Yeoman is a noun originally referring either to one who owns and cultivates land or to the middle ranks of servants in an English royal or noble household. The term was first documented in mid-14th-century England. The 14th century also witn ...

or independent small farmer.

The party was known for its populism. Historian Frank Towers has specified an important ideological divide:

Democrats stood for the 'sovereignty of the people' as expressed in popular demonstrations, constitutional conventions, and majority rule as a general principle of governing, whereas Whigs advocated the rule of law, written and unchanging constitutions, and protections for minority interests against majority tyranny.

At its inception, the Democratic Party was the party of the "common man". It opposed the abolition of slavery.

From 1828 to 1848, banking and tariffs were the central domestic policy issues. Democrats strongly favored—and Whigs opposed—expansion to new farm lands, as typified by their expulsion of eastern

American Indians and acquisition of vast amounts of new land in the West after 1846. The party favored the

war with Mexico and opposed anti-immigrant

nativism. In the 1830s, the

Locofocos

The Locofocos (also Loco Focos or Loco-focos) were a faction of the Democratic Party in American politics that existed from 1835 until the mid-1840s.

History

The faction, originally named the Equal Rights Party, was created in New York City as a ...

in New York City were radically democratic, anti-monopoly and were proponents of

hard money and

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

. Their chief spokesman was

William Leggett. At this time,

labor unions were few and some were loosely affiliated with the party.

Presidency of Martin Van Buren (1837–1841)

The Presidency of Martin Van Buren was hobbled by a long economic depression called the

Panic of 1837. The presidency promoted hard money based on gold and silver, an independent federal treasury, a reduced role for the government in the economy, and a liberal policy for the sale of public lands to encourage settlement; they opposed high tariffs to encourage industry. The Jackson policies were kept, such as Indian removal and the

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was an ethnic cleansing and forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850 by the United States government. As part of the Indian removal, members of the Cherokee, ...

. Van Buren personally disliked slavery but he kept the slaveholder's rights intact. Nevertheless, he was distrusted across the South.

The

1840 Democratic convention was the first at which the party adopted a platform. Delegates reaffirmed their belief that the Constitution was the primary guide for each state's political affairs. To them, this meant that all roles of the federal government not specifically defined fell to each respective state government, including such responsibilities as debt created by local projects. Decentralized power and states' rights pervaded each and every resolution adopted at the convention, including those on slavery, taxes, and the possibility of a central bank. Regarding slavery, the Convention adopted the following resolution:

Resolved, That congress has no power under the Constitution, to interfere with or control the domestic institutions of the several states, and that such states are the sole and proper judges of every thing appertaining to their own affairs, not prohibited by the Constitution: that all efforts of the abolitionists or others, made to induce congress to interfere with questions of slavery, or to take incipient steps in relation thereto, are calculated to lead to the most alarming and dangerous consequences, and that all such efforts have an inevitable tendency to diminish the happiness of the people, and endanger the stability and permanency of the Union, and ought not to be countenanced by any friend to our political institutions.

Harrison and Tyler (1841–1845)

The Panic of 1837 led to Van Buren and the Democrats' drop in popularity. The Whigs nominated

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

as their candidate for the 1840 presidential race. Harrison won as the first president of the Whigs. However, he died in office a month later and was succeeded by his Vice President

John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president dire ...

. Tyler had recently left the Democrats for the Whigs and thus his beliefs did not align much with the Whig Party. During his presidency, he vetoed most of the key Whig bills. The Whigs disowned him. This allowed for the Democrats to retake power in 1845.

Presidency of James K. Polk (1845–1849)

Foreign policy was a major issue in the 1840s as war threatened with Mexico over Texas and with Britain over Oregon. Democrats strongly supported

Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

and most Whigs strongly opposed it. The

1844 election was a showdown, with the Democrat

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

narrowly defeating Whig

Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

on the Texas issue.

John Mack Faragher's analysis of the political polarization between the parties is:

Most Democrats were wholehearted supporters of expansion, whereas many Whigs (especially in the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

) were opposed. Whigs welcomed most of the changes wrought by industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

but advocated strong government policies that would guide growth and development within the country's existing boundaries; they feared (correctly) that expansion raised a contentious issue the extension of slavery to the territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

. On the other hand, many Democrats feared industrialization the Whigs welcomed. ..For many Democrats, the answer to the nation's social ills was to continue to follow Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

's vision of establishing agriculture in the new territories in order to counterbalance industrialization.

Free Soil split

In

1848 a major innovation was the creation of the

Democratic National Committee (DNC) to coordinate state activities in the presidential contest. Senator

Lewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was an American military officer, politician, and statesman. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He w ...

, who held many offices over the years, lost to General

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

of the Whigs. A major cause of the defeat was that the new

Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery int ...

, which opposed slavery expansion, split the Democratic vote, particularly in New York, where the electoral votes went to Taylor. The Free Soil Party attracted Democrats and some Whigs which had considerable support in the Northeast. The primary doctrine was a warning that rich slave owners would move into new territories such as Nebraska and buy up the best lands and work them with slaves. To protect the white farmer it was essential therefore to keep the soil "free"—that is without slavery. In 1852, the free soil movement was much smaller, and consisted primarily of former members of the Liberty Party and some abolitionists, it hedged on the question of full equality. The majority wanted some form of racial separation to allow space for black activism, without alienating the overwhelming northern opposition to equal rights for black men.

Taylor and Fillmore (1849–1853)

Following the death of President Taylor, Democrats in Congress led by Stephen Douglas passed the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Am ...

designed to avoid civil war by putting the slavery issue to rest while resolving issues involving territories gained following the War with Mexico. However, in state after state the Democrats gained small but permanent advantages over the Whig Party, which finally collapsed in 1852, fatally weakened by division on slavery and

nativism. The fragmented opposition could not stop the election of Democrats

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

in

1852 and

James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

in

1856.

The presidencies of Franklin Pierce (1853–1857) and James Buchanan (1857–1861)

The eight years during which Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan held the presidency were disasters; historians agree that they rank as among the worst presidents. The Party increasingly split along regional lines on the issue of slavery in the territories. When the new Republican Party formed in 1854, many anti-slavery ("Free Soil") Democrats in the North switched over and joined it. In 1860 two Democrats ran for president and the United States was moving rapidly toward civil war.

Young America

The 1840s and 1850s were the heyday of a new faction of young Democrats called "

Young America". Led by

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

, James K. Polk, Franklin Pierce and New York financier

August Belmont

August Belmont Sr. (born August Schönberg; December 8, 1813November 24, 1890) was a German-American financier, diplomat, politician and party chairman of the Democratic National Committee, and also a horse-breeder and racehorse owner. He wa ...

, this faction explains, broke with the agrarian and

strict constructionist

In the United States, strict constructionism is a particular legal philosophy of judicial interpretation that limits or restricts such interpretation only to the exact wording of the law (namely the Constitution).

Strict sense of the term

...

orthodoxies of the past and embraced commerce, technology, regulation, reform and internationalism. The movement attracted a circle of outstanding writers, including

William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 – June 12, 1878) was an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the ''New York Evening Post''. Born in Massachusetts, he started his career as a lawyer but showed an interest in poetry ...

,

George Bancroft

George Bancroft (October 3, 1800 – January 17, 1891) was an American historian, statesman and Democratic politician who was prominent in promoting secondary education both in his home state of Massachusetts and at the national and internati ...

,

Herman Melville

Herman Melville (Name change, born Melvill; August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American people, American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance (literature), American Renaissance period. Among his bes ...

and

Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

. They sought independence from European standards of

high culture

High culture is a subculture that emphasizes and encompasses the cultural objects of aesthetic value, which a society collectively esteem as exemplary art, and the intellectual works of philosophy, history, art, and literature that a society con ...

and wanted to demonstrate the excellence and

exceptionalism of

America's own literary tradition.

In economic policy, Young America saw the necessity of a modern infrastructure with railroads, canals, telegraphs, turnpikes and harbors. They endorsed the "

market revolution

The Market Revolution in 19th century United States is a historical model which argues that there was a drastic change of the economy that disoriented and coordinated all aspects of the market economy in line with both nations and the world. Char ...

" and promoted

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

. They called for Congressional land grants to the states, which allowed Democrats to claim that

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

were locally rather than federally sponsored. Young America claimed that modernization would perpetuate the agrarian vision of

Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, whic ...

by allowing yeomen farmers to sell their products and therefore to prosper. They tied internal improvements to

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

, while accepted moderate tariffs as a necessary source of government revenue. They supported the

Independent Treasury

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6 ...

(the Jacksonian alternative to the Second Bank of the United States) not as a scheme to quash the special privilege of the Whiggish monied elite, but as a device to spread prosperity to all

Americans

Americans are the Citizenship of the United States, citizens and United States nationality law, nationals of the United States, United States of America.; ; Although direct citizens and nationals make up the majority of Americans, many Multi ...

.

Breakdown of the Second Party System (1854–1859)

Sectional confrontations escalated during the 1850s, the Democratic Party split between

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

grew deeper. The conflict was papered over at the

1852 and

1856 conventions by selecting men who had little involvement in sectionalism, but they made matters worse. Historian

Roy F. Nichols explains why

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

was not up to the challenges a Democratic president had to face:

:As a national political leader Pierce was an accident. He was honest and tenacious of his views but, as he made up his mind with difficulty and often reversed himself before making a final decision, he gave a general impression of instability. Kind, courteous, generous, he attracted many individuals, but his attempts to satisfy all factions failed and made him many enemies. In carrying out his principles of strict construction he was most in accord with Southerners, who generally had the

letter of the law

The letter of the law and the spirit of the law are two possible ways to regard rules, or laws. To obey the letter of the law is to follow the literal reading of the words of the law, whereas following the spirit of the law means enacting the ...

on their side. He failed utterly to realize the depth and the sincerity of Northern feeling against the South and was bewildered at the general flouting of the law and the Constitution, as he described it, by the people of his own New England. At no time did he catch the popular imagination. His inability to cope with the difficult problems that arose early in his administration caused him to lose the respect of great numbers, especially in the North, and his few successes failed to restore public confidence. He was an inexperienced man, suddenly called to assume a tremendous responsibility, who honestly tried to do his best without adequate training or temperamental fitness.

In 1854, Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois—a key Democratic leader in the Senate—pushed the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

through Congress. President

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

signed the bill into law in 1854.

The Act opened

Kansas Territory

The Territory of Kansas was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until January 29, 1861, when the eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the Slave and ...

and

Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebrask ...

to a decision by the residents on whether slavery would be legal or not. Previously it had been illegal there. Thus the new law implicitly repealed the prohibition on slavery in territory north of

36° 30′ latitude that had been part of the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

of 1820.

Supporters and enemies of slavery poured into Kansas to vote slavery up or down. The armed conflict was

Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

and it shook the nation. A major re-alignment took place among voters and politicians. The Whig Party fell apart and the new Republican Party was founded in opposition to the expansion of slavery and to the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

. The new party had little support in the South, but it soon became a majority in the North by pulling together former Whigs and former Free Soil Democrats.

[William E. Gienapp, ''The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856'' (1987) explores statistically the flow of voters between parties in the 1850s.]

North and South pull apart

The crisis for the Democratic Party came in the late 1850s as Democrats increasingly rejected national policies demanded by the Southern Democrats. The demands were to support slavery outside the South. Southerners insisted that full equality for their region required the government to acknowledge the legitimacy of slavery outside the South. The Southern demands included a fugitive slave law to recapture runaway slaves; opening Kansas to slavery; forcing a pro-slavery constitution on Kansas; acquire Cuba (where slavery already existed); accepting the Dred Scott decision of the Supreme Court; and adopting a federal slave code to protect slavery in the territories. President Buchanan went along with these demands, but Douglas refused and proved a much better politician than Buchanan, though the bitter battle lasted for years and permanently alienated the Northern and Southern wings.

When the new

Republican Party formed in 1854 on the basis of refusing to tolerate the expansion of slavery into the territories, many northern Democrats (especially

Free Soilers

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

from 1848) joined it. The formation of the new short-lived

Know-Nothing Party

The Know Nothing party was a nativist political party and movement in the United States in the mid-1850s. The party was officially known as the "Native American Party" prior to 1855 and thereafter, it was simply known as the "American Party". ...

allowed the Democrats to win the presidential election of 1856.

Buchanan, a Northern "

Doughface

The term doughface originally referred to an actual mask made of dough, but came to be used in a disparaging context for someone, especially a politician, who is perceived to be pliable and moldable. In the 1847 ''Webster's Dictionary'' ''doughfac ...

" (his base of support was in the pro-slavery South), split the party on the issue of slavery in Kansas when he attempted to pass a federal slave code as demanded by the South. Most Democrats in the North rallied to Senator Douglas, who preached "

Popular Sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the authority of a state and its government are created and sustained by the consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. Popular sovereignty, being a principle, does not imply any ...

" and believed that a Federal slave code would be undemocratic.

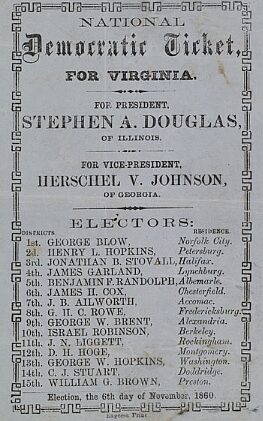

In

1860, the Democrats split over the choice of a successor to President Buchanan along Northern and Southern lines. Some

Southern Democratic delegates followed the lead of the

Fire-Eaters

In American history, the Fire-Eaters were a group of pro-slavery Democrats in the Antebellum South who urged the separation of Southern states into a new nation, which became the Confederate States of America. The dean of the group was Robert R ...

by walking out of the

Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

at

Charleston's Institute Hall in April 1860. They were later joined by those who, once again led by the Fire-Eaters, left the

Baltimore Convention the following June when the convention rejected a resolution supporting extending slavery into territories whose voters did not want it. The Southern Democrats, also referred to as Seceders, nominated

John C. Breckinridge

John Cabell Breckinridge (January 16, 1821 – May 17, 1875) was an American lawyer, politician, and soldier. He represented Kentucky in both houses of Congress and became the 14th and youngest-ever vice president of the United States. Serving ...

of Kentucky, the pro-slavery incumbent vice president, for president and General

Joseph Lane

Joseph "Joe" Lane (December 14, 1801 – April 19, 1881) was an American politician and soldier. He was a state legislator representing Evansville, Indiana, and then served in the Mexican–American War, becoming a general. President James K. ...

, former governor of Oregon, for vice president.

[David M. Potter. ''The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861'' (1976). ch. 16.] The

Northern Democrats

The Northern Democratic Party was a leg of the Democratic Party during the 1860 presidential election, when the party split in two factions because of disagreements over slavery. They held two conventions before the election, in Charleston and ...

proceeded to nominate Douglas of Illinois for president and former governor of Georgia

Herschel Vespasian Johnson

Herschel Vespasian Johnson (September 18, 1812August 16, 1880) was an American politician. He was the 41st Governor of Georgia from 1853 to 1857 and the vice presidential nominee of the Douglas wing of the Democratic Party in the 1860 U.S. pr ...

for vice president, while some southern Democrats joined the

Constitutional Union Party, backing former Senator

John Bell of Tennessee for president and politician

Edward Everett

Edward Everett (April 11, 1794 – January 15, 1865) was an American politician, Unitarian pastor, educator, diplomat, and orator from Massachusetts. Everett, as a Whig, served as U.S. representative, U.S. senator, the 15th governor of Mass ...

of Massachusetts for vice president. This fracturing of the Democratic Party left it powerless.

Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States. Douglas campaigned across the country calling for unity and came in second in the popular vote, but carried only Missouri and New Jersey. Breckinridge carried 11

slave states

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, coming in second in the Electoral vote, but third in the popular vote.

Presidency of Abraham Lincoln (1861–1865)

Civil War

During the

Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, Northern Democrats divided into two factions: the

War Democrats

War Democrats in American politics of the 1860s were members of the Democratic Party who supported the Union and rejected the policies of the Copperheads (or Peace Democrats). The War Democrats demanded a more aggressive policy toward the C ...

, who supported the military policies of President Lincoln; and the

Copperheads, who strongly opposed them. In the South party politics ended in the

Confederacy. The political leadership, mindful of the fierce divisions in antebellum American politics and with a pressing need for unity, rejected organized political parties as inimical to good governance and as being especially unwise in wartime. Consequently, the Democratic Party halted all operations during the life of the Confederacy (1861–1865).

[Jennifer L. Weber, ''Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln's Opponents in the North'' (2006)]

Partisanship flourished in the North and strengthened the Lincoln Administration as Republicans automatically rallied behind it. After the

attack on Fort Sumter, Douglas rallied

Northern Democrats

The Northern Democratic Party was a leg of the Democratic Party during the 1860 presidential election, when the party split in two factions because of disagreements over slavery. They held two conventions before the election, in Charleston and ...

behind the Union, but when Douglas died the party lacked an outstanding figure in the North and by 1862 an anti-war peace element was gaining strength. The most intense anti-war elements were the

Copperheads.

The Democratic Party did well in the

1862 congressional elections, but in

1864

Events

January–March

* January 13 – American songwriter Stephen Foster ("Oh! Susanna", "Old Folks at Home") dies aged 37 in New York City, leaving a scrap of paper reading "Dear friends and gentle hearts". His parlor song " ...

it nominated General

George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American soldier, Civil War Union general, civil engineer, railroad executive, and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey. A graduate of West Point, McCl ...

(a War Democrat) on a peace platform and lost badly because many War Democrats bolted to

National Union candidate Abraham Lincoln. Many former Douglas Democrats became Republicans, especially soldiers such as generals

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

and

John A. Logan

John Alexander Logan (February 9, 1826 – December 26, 1886) was an American soldier and politician. He served in the Mexican–American War and was a general in the Union Army in the American Civil War. He served the state of Illinois as a st ...

.

Presidency of Andrew Johnson (1865–1869)

In the

1866 elections, the

Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

won two-thirds majorities in Congress and took control of national affairs. The large Republican majorities made Congressional Democrats helpless, though they unanimously opposed the Radicals'

Reconstruction policies. The Senate passed the 14th Amendment by a vote of 33 to 11 with every Democratic senator opposed. Realizing that the old issues were holding it back, the Democrats tried a "

New Departure" that downplayed the War and stressed such issues as stopping corruption and

white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White su ...

, which it wholeheartedly supported.

President Johnson, elected on the fusion Union Party ticket, did not rejoin the Democratic party, but Democrats in Congress supported him and voted against his impeachment in 1868. After his term ended in 1869 he rejoined the Democrats.

Republican interlude 1869–1885

War hero

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

led the Republicans to

landslides

Landslides, also known as landslips, are several forms of mass wasting that may include a wide range of ground movements, such as rockfalls, deep-seated slope failures, mudflows, and debris flows. Landslides occur in a variety of environments, ...

in

1868

Events

January–March

* January 2 – British Expedition to Abyssinia: Robert Napier leads an expedition to free captive British officials and missionaries.

* January 3 – The 15-year-old Mutsuhito, Emperor Meiji of Jap ...

and

1872

Events

January–March

* January 12 – Yohannes IV is crowned Emperor of Ethiopia in Axum, the first ruler crowned in that city in over 500 years.

* February 2 – The government of the United Kingdom buys a number of forts on ...

.

When a major economic depression hit the United States with the

Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

, the Democratic party made major gains across the country, took full control of the South, and took control of Congress.

The Democrats lost consecutive presidential elections from 1860 through 1880, nevertheless Democrats have won the popular vote in

1876. Although the races after 1872 were very close they did not win the presidency until

1884. The party was weakened by its record of opposition to the war, but nevertheless benefited from

White Southerners

White Southerners, from the Southern United States, are considered an ethnic group by some historians, sociologists and journalists, although this categorization has proven controversial, and other academics have argued that Southern identity do ...

' resentment of

Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

and consequent hostility to the Republican Party. The

nationwide depression of 1873 allowed the Democrats to retake control of the House in the

1874 Democratic landslide.

The

Redeemers

The Redeemers were a political coalition in the Southern United States during the Reconstruction Era that followed the Civil War. Redeemers were the Southern wing of the Democratic Party. They sought to regain their political power and enforce ...

gave the Democrats control of every Southern state (by the

Compromise of 1877), but the

disenfranchisement of blacks took place (1880–1900). From 1880 to 1960, the "

Solid South

The Solid South or Southern bloc was the electoral voting bloc of the states of the Southern United States for issues that were regarded as particularly important to the interests of Democrats in those states. The Southern bloc existed especial ...

" voted Democratic in presidential elections (except 1928). After 1900, a victory in a Democratic primary was "

tantamount to election

A safe seat is an electoral district (constituency) in a legislative body (e.g. Congress, Parliament, City Council) which is regarded as fully secure, for either a certain political party, or the incumbent representative personally or a combinati ...

" because the Republican Party was so weak in the South.

The politicized cowboy image

Heather Cox Richardson

Heather Cox Richardson is an American historian and professor of history at Boston College, where she teaches courses on the American Civil War, the Reconstruction Era, the American West, and the Plains Indians. She previously taught history ...

argues for a political dimension to the cowboy image in the 1870s and 1880s,:

The timing of the cattle industry’s growth meant that cowboy imagery grew to have extraordinary power. Entangled in the vicious politics of the postwar years, Democrats, especially those in the old Confederacy, imagined the West as a land untouched by Republican politicians they hated. They developed an image of the cowboys as men who worked hard, played hard, lived by a code of honor, protected themselves, and asked nothing of the government. In the hands of Democratic newspaper editors, the realities of cowboy life -- the poverty, the danger, the debilitating hours -- became romantic. Cowboys embodied virtues Democrats believed Republicans were destroying by creating a behemoth government catering to lazy ex-slaves. By the 1860s, cattle drives were a feature of the plains landscape, and Democrats had made cowboys a symbol of rugged individual independence, something they insisted Republicans were destroying.

Cleveland, Harrison, Cleveland (1885–1897)

After being out of office since 1861, the Democrats won the popular vote in three consecutive elections, and the electoral vote (and thus the White House) in 1884 and 1892.

The first presidency of Grover Cleveland (1885–1889)

Although Republicans continued to control the White House until 1884, the Democrats remained competitive (especially in the

mid-Atlantic and lower

Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

) and controlled the House of Representatives for most of that period. In the election of

1884,

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

, the reforming Democratic Governor of New York, won the Presidency, a feat he repeated in

1892

Events

January–March

* January 1 – Ellis Island begins accommodating immigrants to the United States.

* February 1 - The historic Enterprise Bar and Grill was established in Rico, Colorado.

* February 27 – Rudolf Diesel applies for ...

, having lost in the election of

1888.

Cleveland was the leader of the

Bourbon Democrats

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who supp ...

. They represented business interests, supported banking and railroad goals, promoted ''

laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( ; from french: laissez faire , ) is an economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies) deriving from special interest groups. ...

'' capitalism, opposed

imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

and U.S. overseas expansion, opposed the annexation of

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, fought for the

gold standard

A gold standard is a monetary system in which the standard economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the early 1920s, and from the la ...

and opposed

Bimetallism

Bimetallism, also known as the bimetallic standard, is a monetary standard in which the value of the monetary unit is defined as equivalent to certain quantities of two metals, typically gold and silver, creating a fixed rate of exchange betwee ...

. They strongly supported reform movements such as

Civil Service Reform and opposed corruption of city bosses, leading the fight against the

Tweed Ring

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), often erroneously referred to as William "Marcy" Tweed (see below), and widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany H ...

.

The leading Bourbons included

Samuel J. Tilden,

David Bennett Hill

David Bennett Hill (August 29, 1843October 20, 1910) was an American politician from New York who was the 29th Governor of New York from 1885 to 1891 and represented New York in the United States Senate from 1892 to 1897.

In 1892, he made an u ...

and

William C. Whitney of New York,

Arthur Pue Gorman

Arthur Pue Gorman (March 11, 1839June 4, 1906) was an American politician. He was leader of the Gorman-Rasin organization with Isaac Freeman Rasin that controlled the Maryland Democratic Party from the late 1870s until his death in 1906. Gorman ...

of Maryland,

Thomas F. Bayard

Thomas Francis Bayard (October 29, 1828 – September 28, 1898) was an American lawyer, politician and diplomat from Wilmington, Delaware. A Democrat, he served three terms as United States Senator from Delaware and made three unsuccessful bids ...

of Delaware,

Henry M. Mathews and

William L. Wilson of West Virginia,

John Griffin Carlisle

John Griffin Carlisle (September 5, 1834July 31, 1910) was an American politician from the commonwealth of Kentucky and was a member of the Democratic Party. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives seven times, first in 18 ...

of Kentucky,

William F. Vilas

William Freeman Vilas (July 9, 1840August 27, 1908) was an American lawyer, politician, and United States Senator. In the U.S. Senate, he represented the state of Wisconsin for one term, from 1891 to 1897. As a prominent Bourbon Democrat, he wa ...

of Wisconsin,

J. Sterling Morton

Julius Sterling Morton (April 22, 1832 – April 27, 1902) was a Nebraska newspaper editor and politician who served as President Grover Cleveland's United States Secretary of Agriculture, Secretary of Agriculture. He was a prominent Bourbon Dem ...

of Nebraska,

John M. Palmer of Illinois,

Horace Boies

Horace Boies (December 7, 1827 – April 4, 1923) served as the 14th Governor of Iowa from 1890 to 1894 as a member of the United States Democratic Party. Boies was the only Democrat to serve in that position from 1855 to 1933, a period of 78 y ...

of Iowa,

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar

Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar II (September 17, 1825January 23, 1893) was an American politician, diplomat, and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, he represented Mississippi in both houses of Congress, served as the United States Se ...

of Mississippi and railroad builder

James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railroad director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwes ...

of Minnesota. A prominent intellectual was

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

.

[Addkison-Simmons, D. (2010). Henry Mason Mathews. ''e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia''. Retrieved December 11, 2012, fro]

"Henry Mason Mathews"

Republican Benjamin Harrison won a narrow victory in 1888. The party pushed through a large agenda, and raised the

McKinley Tariff

The Tariff Act of 1890, commonly called the McKinley Tariff, was an act of the United States Congress, framed by then Representative William McKinley, that became law on October 1, 1890. The tariff raised the average duty on imports to almost fift ...

and federal spending so high it was used against them as Democrats scored a landslide in

the 1890 elections. Harrison was easily defeated for reelection in 1892 by Cleveland.

The second presidency of Grover Cleveland (1893–1897)

The Bourbons were in power when the

Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

hit and they took the blame. The party polarized between the pro-gold pro-business Cleveland faction and the anti-business silverites in the West and South. A fierce struggle inside the party ensued, with catastrophic losses for both the Bourbon and agrarian factions in 1894, leading to the showdown in 1896. Just before the 1894 election, President Cleveland was warned by an advisor:

:We are on the eve of very dark night, unless a return of commercial prosperity relieves popular discontent with what they believe Democratic incompetence to make laws, and consequently with Democratic Administrations anywhere and everywhere.

Aided by the deep nationwide economic depression that lasted from 1893 to 1897, the Republicans won their biggest landslide ever, taking full control of the House. The Democrats lost nearly all their seats in the Northeast. The third party Populists also were ruined. However, Cleveland's silverite enemies gained control of the Democratic Party in state after state, including full control in Illinois and Michigan and made major gains in Ohio, Indiana, Iowa and other states. Wisconsin and Massachusetts were two of the few states that remained under the control of Cleveland's allies.

The rise and fall of William Jennings Bryan

The opposition Democrats were close to controlling two-thirds of the vote at the

1896 national convention, which they needed to nominate their own candidate. However, they were not united and had no national leader, as Illinois governor

John Peter Altgeld

John Peter Altgeld (December 30, 1847 – March 12, 1902) was an American politician and the 20th Governor of Illinois, serving from 1893 until 1897. He was the first Democrat to govern that state since the 1850s. A leading figure of the Progr ...

had been born in Germany and was ineligible to be nominated for president.

However, a young (35 years old) upstart, Congressman

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

made the magnificent "cross of gold" speech, which brought the crowd at the convention to its feet and got him the nomination. He would lose the election, but remained the Democratic hero and was renominated and lost again in 1900 and a third time in 1908.

Free silver movement

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

led the party faction of conservative, pro-business

Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, especially those who su ...

s, but as the

depression of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an Depression (economics), economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignmen ...

deepened his enemies multiplied. At the

1896 convention, the silverite-agrarian faction repudiated the President and nominated the crusading orator

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (March 19, 1860 – July 26, 1925) was an American lawyer, orator and politician. Beginning in 1896, he emerged as a dominant force in the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, running ...

on a platform of

free coinage of silver. The idea was that minting silver coins would flood the economy with cash and end the depression. Cleveland supporters formed the

National Democratic Party (Gold Democrats), which attracted politicians and intellectuals (including

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

and

Frederick Jackson Turner

Frederick Jackson Turner (November 14, 1861 – March 14, 1932) was an American historian during the early 20th century, based at the University of Wisconsin until 1910, and then Harvard University. He was known primarily for his frontier thes ...

) who refused to vote Republican.

Bryan, an overnight sensation because of his "

Cross of Gold

The Cross of Gold speech was delivered by William Jennings Bryan, a former United States Representative from Nebraska, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on July 9, 1896. In his address, Bryan supported " free silver" (i.e. bime ...

" speech, waged a new-style crusade against the supporters of the gold standard. Criss-crossing the

Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

and

East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

by special train – he was the first candidate since 1860 to go on the road – he gave over 500 speeches to audiences in the millions. In St. Louis he gave 36 speeches to workingmen's audiences across the city, all in one day. Most Democratic newspapers were hostile toward Bryan, but he seized control of the media by making the news every day as he hurled thunderbolts against Eastern monied interests.

[Richard J. Jensen, ''The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict 1888–1896'' (1971]

free online edition

/ref>

The rural folk in the South and Midwest were ecstatic, showing an enthusiasm never before seen, but ethnic Democrats (especially Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

and Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

) were alarmed and frightened by Bryan. The middle classes, businessmen, newspaper editors, factory workers, railroad workers and prosperous farmers generally rejected Bryan's crusade. Republican William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Republican Party largely dominant in ...

promised a return to prosperity based on the gold standard, support for industry, railroads and banks and pluralism that would enable every group to move ahead.election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

in a landslide, he did win the hearts and minds of a majority of Democrats, as shown by his renomination in 1900 and 1908. As late as 1924, the Democrats put his brother Charles W. Bryan on their national ticket. The victory of the Republican Party in the election of 1896 marked the start of the "Progressive Era

The Progressive Era (late 1890s – late 1910s) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste and inefficiency. The main themes ended during Am ...

", which lasted from 1896 to 1932, in which the Republican Party usually was dominant.

The GOP Presidencies of McKinley (1897–1901), Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) and Taft (1909–1913)

The 1896 election marked a political realignment in which the Republican Party controlled the presidency for 28 of 36 years. The Republicans dominated most of the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each se ...

and Midwest and half the West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

. Bryan, with a base in the South and Plains states