The history of West Africa has been divided into its

prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The us ...

, the Iron Age in Africa, the major polities flourishing, the colonial period, and finally the post-independence era, in which the current nations were formed.

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

is west of an imagined north–south axis lying close to

10° east longitude, bordered by the

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

and

Sahara Desert

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

. Colonial boundaries are reflected in the modern boundaries between contemporary West African states, cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, often dividing single ethnic groups between two or more states.

West African populations were considerably mobile and interacted with one another throughout the

population history of West Africa.

Acheulean

Acheulean (; also Acheulian and Mode II), from the French ''acheuléen'' after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated ...

tool-using

archaic humans

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP (

Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

).

During the

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

,

Middle Stone Age

The Middle Stone Age (or MSA) was a period of African prehistory between the Early Stone Age and the Late Stone Age. It is generally considered to have begun around 280,000 years ago and ended around 50–25,000 years ago. The beginnings of ...

peoples (e.g.,

Iwo Eleru people,

possibly

Aterians

The Aterian is a Middle Stone Age (or Middle Palaeolithic) stone tool industry centered in North Africa, from Mauritania to Egypt, but also possibly found in Oman and the Thar Desert. The earliest Aterian dates to c. 150,000 years ago, at th ...

), who dwelled throughout West Africa between

MIS 4

Marine isotope stages (MIS), marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages (OIS), are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate, deduced from oxygen isotope data reflecting changes in temperature derived from data f ...

and

MIS 2

Marine isotope stages (MIS), marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages (OIS), are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate, deduced from oxygen isotope data reflecting changes in temperature derived from data f ...

,

were gradually replaced by incoming

Late Stone Age peoples, who migrated into West Africa

as an increase in humid conditions resulted in the subsequent expansion of the

West African forest.

West African hunter-gatherers

West African hunter-gatherers, West African foragers, or West African pygmies dwelled in western Central Africa earlier than 32,000 BP and dwelled in West Africa between 16,000 BP and 12,000 BP until as late as 1000 BP or some period of time after ...

occupied western

Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Co ...

(e.g.,

Shum Laka

The archaeological site of Shum Laka is the most prominent rockshelter site in the Grasslands region of the Laka Valley, northwest Cameroon. Occupations at this rockshelter date to the Later Stone Age. This region is important to investigations of ...

) earlier than 32,000 BP,

dwelled throughout

coastal West Africa by 12,000 BP,

migrated northward between 12,000 BP and 8000 BP as far as Mali, Burkina Faso,

and Mauritania,

and persisted as late as 1000 BP

or some period of time after 1500 CE.

During the

Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

, sedentary farming developed in West Africa among the ancestors of modern West Africans. The

Iron industry

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

, in both smelting and forging for tools and weapons, appeared in

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

by 1200 BCE, and by 400 BCE, contact had been made with the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

civilizations, and a regular trade included exporting gold, cotton, metal, and leather in exchange for copper, horses, salt, textiles, and beads. The

Tichitt culture

The Tichitt Culture, or Tichitt Tradition, was created by Mande peoples. In 4000 BCE, the start of sophisticated social structure (e.g., trade of cattle as valued assets) developed among herders amid the Pastoral Period of the Sahara. Saharan p ...

developed in 2200 BCE

and lasted until around 200 BCE.

The

Nok culture

The Nok culture (or Nok civilization) is a population whose material remains are named after the Ham village of Nok in Kaduna State of Nigeria, where their terracotta sculptures were first discovered in 1928. The Nok culture appeared in Nige ...

developed in 1500 BCE

[Breunig, Peter. 2014. Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context: p. 21.] and vanished under unknown circumstances around 500 CE.

[Breunig, P. (2014)]

Nok. African Sculpture in Archaeological Context. Frankfurt: Africa Magna.

/ref> Serer people

The Serer people are a West African ethnoreligious group. constructed the Senegambian stone circles

The Senegambian stone circles are groups of megalithic stone circles that lie in The Gambia north of Janjanbureh and in central Senegal. With an approximate area of 30,000 km²,Laport et al. 2012, p. 410 they are sometimes divided into th ...

between 3rd century BCE and 16th century CE. The Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of centralized kingdoms or empires that were centered on the Sahel, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara, from the 8th century to the 19th. The wealth of the states came from controlling the trade routes a ...

were a series of kingdoms or empires that were built on the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid cli ...

, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

. They controlled the trade routes across the desert, and were also quite decentralised, with member cities having a great deal of autonomy. The Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire, also known as Wagadou ( ar, غانا) or Awkar, was a West African empire based in the modern-day southeast of Mauritania and western Mali that existed from c. 300 until 1100. The Empire was founded by the Soninke people, a ...

may have been established as early as the 3rd century CE. It was succeeded by the Sosso

The Sosso Empire was a twelfth-century Kaniaga kingdom of West Africa.

The Kingdom of Sosso, also written as Soso or Susu, was an ancient kingdom on the coast of west Africa. During its empire, reigned their most famous leader, Sumaoro Kan ...

in 1230, the Mali Empire

The Mali Empire (Manding: ''Mandé''Ki-Zerbo, Joseph: ''UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century'', p. 57. University of California Press, 1997. or Manden; ar, مالي, Māl� ...

in the 13th century CE, and later by the Songhai and Sokoto Caliphate. There were also a number of forest empires and states in this time period.

Following the collapse of the Songhai Empire, a number of smaller states arose across West Africa, including the Bambara Empire

The Bamana Empire (also Bambara Empire or Ségou Empire, bm, italics=no, ߓߊ߲ߓߊߙߊ߲߫ ߝߊ߯ߡߟߊ, Banbaran Fāmala) was a large West African state based at Ségou, now in Mali. This state was established after the fall of the Mali E ...

of Ségou

Ségou (; bm, ߛߋߓߎ, italic=no, ) is a town and an urban commune in south-central Mali that lies northeast of Bamako on the right bank of the River Niger. The town is the capital of the Ségou Cercle and the Ségou Region. With 130,690 ...

, the lesser Bambara kingdom of Kaarta

Kaarta, or Ka'arta, was a short-lived Bambara kingdom in what is today the western half of Mali.

As Bitòn Coulibaly tightened his control over Ségou, capital of his newly founded Bambara Empire, a faction of Ségou Bambara dissatisfied with ...

, the Fula/ Malinké kingdom of Khasso Khasso or Xaaso was a West African kingdom of the 17th to 19th centuries, occupying territory in what is today Senegal and the Kayes Region of Mali. Over two thousand years ago, it was part of Serer territory. From the 17th to 19th centuries, its c ...

(in present-day Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

's Kayes Region

Kayes Region ( Bambara: ߞߊߦߌ ߘߌߣߋߖߊ tr. Kayi Dineja) is one of eight first level national subdivisions in Mali called Regions. It is the first administrative area of Mali and covers an area of . Its capital is the town of Kayes. The ...

), and the Kénédougou Empire of Sikasso

Sikasso ( Bambara: ߛߌߞߊߛߏ tr. Sikaso) is a city in the south of Mali and the capital of the Sikasso Cercle and the Sikasso Region. It is Mali's second largest city with 225,753 residents in the 2009 census.

History

Sikasso was founded ...

. European traders first became a force in the region in the 15th century. The Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade, transatlantic slave trade, or Euro-American slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route and ...

began, with the Portuguese taking hundreds of captives back to their country for use as slaves; however, it would not begin on a grand scale until Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

's voyage to the Americas and the subsequent demand for cheap colonial labour. As the demand for slaves increased, some African rulers sought to supply the demand by constant war against their neighbours, resulting in fresh captives. European, American and Haitian governments passed legislation prohibiting the Atlantic slave trade in the 19th century, though the last country to abolish the institution was Brazil in 1888.

In 1725, the cattle-herding Fulani

The Fula, Fulani, or Fulɓe people ( ff, Fulɓe, ; french: Peul, links=no; ha, Fulani or Hilani; pt, Fula, links=no; wo, Pël; bm, Fulaw) are one of the largest ethnic groups in the Sahel and West Africa, widely dispersed across the region. ...

s of Fouta Djallon

Fouta Djallon ( ff, 𞤊𞤵𞥅𞤼𞤢 𞤔𞤢𞤤𞤮𞥅, Fuuta Jaloo; ar, فوتا جالون) is a highland region in the center of Guinea, roughly corresponding with Middle Guinea, in West Africa.

Etymology

The Fulani people call the r ...

launched the first major reformist jihad

Jihad (; ar, جهاد, jihād ) is an Arabic word which literally means "striving" or "struggling", especially with a praiseworthy aim. In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with G ...

of the region, overthrowing the local animist

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning 'breath, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things— animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather systems ...

, Mande-speaking elites and attempting to somewhat democratize their society. At the same time, the Europeans started to travel into the interior of Africa to trade and explore. Mungo Park (1771–1806) made the first serious expedition into the region's interior, tracing the Niger River as far as Timbuktu

Timbuktu ( ; french: Tombouctou;

Koyra Chiini: ); tmh, label=Tuareg, script=Tfng, ⵜⵏⴱⴾⵜ, Tin Buqt a city in Mali, situated north of the Niger River. The town is the capital of the Tombouctou Region, one of the eight administrativ ...

. French armies followed not long after. In the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ...

in the 1880s the Europeans started to colonise the inland of West Africa, they had previously mostly controlled trading ports along the coasts and rivers. Following World War II, campaigns for independence sprung up across West Africa, most notably in Ghana under the Pan-Africanist

Pan-Africanism is a worldwide movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous and diaspora peoples of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atlantic slave trade, the movement exte ...

Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah (born 21 September 190927 April 1972) was a Ghanaian politician, political theorist, and revolutionary. He was the first Prime Minister and President of Ghana, having led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957. An ...

(1909–1972). After a decade of protests, riots and clashes, French West Africa voted for autonomy in a 1958 referendum, dividing into the states of today; most of the British colonies gained autonomy the following decade. Since independence, West Africa has suffered from the same problems as much of the African continent, particularly dictatorships, political corruption and military coup

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

s; it has also seen bloody civil wars. The development of oil and mineral wealth has seen the steady modernization of some countries since the early 2000s, though inequality persists.

Geographic background

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

is west of an imagined north–south axis lying close to 10° east longitude.Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

forms the western and southern borders of the West African region.Sahara Desert

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, with the Ranishanu Bend generally considered the northernmost part of the region. The eastern border is less precise, with some placing it at the Benue Trough, and others on a boundary line spanning from Mount Cameroon

Mount Cameroon is an active volcano in the South West region of Cameroon next to the city of Buea near the Gulf of Guinea. Mount Cameroon is also known as Cameroon Mountain or Fako (the name of the higher of its two peaks) or by its indigenous n ...

to Lake Chad

Lake Chad (french: Lac Tchad) is a historically large, shallow, endorheic lake in Central Africa, which has varied in size over the centuries. According to the ''Global Resource Information Database'' of the United Nations Environment Programme ...

.

In 15,000 BP, the West African Monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annual latitudinal oscill ...

transformed the landscape of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and began the Green Sahara

The African humid period (AHP) (also known by other names) is a climate period in Africa during the late Pleistocene and Holocene geologic epochs, when northern Africa was wetter than today. The covering of much of the Sahara desert by grasses, ...

period; greater rainfall during the summer season resulted in the growth of humid conditions (e.g., lakes

A lake is an area filled with water, localized in a basin, surrounded by land, and distinct from any river or other outlet that serves to feed or drain the lake. Lakes lie on land and are not part of the ocean, although, like the much large ...

, wetlands

A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently (for years or decades) or seasonally (for weeks or months). Flooding results in oxygen-free (anoxic) processes prevailing, especially in the soils. The p ...

) and the savanna (e.g., grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses ( Poaceae). However, sedge ( Cyperaceae) and rush ( Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur na ...

, shrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally or be the result of human activity. It ...

) in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

.desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

containing the Western Sahara

Western Sahara ( '; ; ) is a disputed territory on the northwest coast and in the Maghreb region of North and West Africa. About 20% of the territory is controlled by the self-proclaimed Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), while the ...

. Ancient West Africa included the Sahara, which became a desert by 3000 BCE. During the last glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

, the Sahara, extending south far beyond the boundaries that now exist.

The area located at the south of the desert is a steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate gras ...

, a semi-arid region, called the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid cli ...

. It is the ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition in Africa between the Sahara desert to the north and the Sudanian Savanna to the south. The Sudanian Savanna is a broad belt of tropical savanna that spans the African continent

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, from the Atlantic Ocean coast in the West Sudanian savanna to the Ethiopian Highlands

The Ethiopian Highlands is a rugged mass of mountains in Ethiopia in Northeast Africa. It forms the largest continuous area of its elevation in the continent, with little of its surface falling below , while the summits reach heights of up to . ...

in the East Sudanian savanna

The East Sudanian savanna is a hot, dry, tropical savanna ecoregion of Central and East Africa.

Geography

The East Sudanian savanna is the eastern half of the Sudanian savanna belt which runs east and west across Africa. The eastern lies eas ...

.

The Guinean region is a traditional name for the region that lies along the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea is the northeasternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean from Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Palmas in Liberia. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is i ...

. It stretches north through the forested tropical

The tropics are the regions of Earth surrounding the Equator. They are defined in latitude by the Tropic of Cancer in the Northern Hemisphere at N and the Tropic of Capricorn in

the Southern Hemisphere at S. The tropics are also referred to ...

regions and ends at the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid cli ...

. The Guinean Forests of West Africa

The Guinean forests of West Africa is a biodiversity hotspot designated by Conservation International, which includes the belt of tropical moist broadleaf forests along the coast of West Africa, running from Sierra Leone and Guinea in the west to t ...

is a belt of tropical moist broadleaf forests along the coast, spanning from Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

and Guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

through Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to Guinea–Liberia border, its north, Ivory Coast to Ivory Coast� ...

, Côte d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre ...

and Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

and Togo

Togo (), officially the Togolese Republic (french: République togolaise), is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its c ...

, to the Sanaga River

The Sanaga River (formerly german: Zannaga) is the largest river in Cameroon located in East Region, Centre Region and Littoral Region. Its length is about from the confluence of Djérem and Lom River. The total length of Sanaga-Djérem Rive ...

of Cameroon

Cameroon (; french: Cameroun, ff, Kamerun), officially the Republic of Cameroon (french: République du Cameroun, links=no), is a country in west-central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west and north; Chad to the northeast; the ...

in the east. The Upper Guinean forests

The Upper Guinean forests is a tropical seasonal forest region of West Africa. The Upper Guinean forests extend from Guinea and Sierra Leone in the west through Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana to Togo in the east, and a few hundred kilometers in ...

and Lower Guinean forests are divided by the Dahomey Gap

In West Africa, the Dahomey Gap refers to the portion of the Guinean forest-savanna mosaic that extends all the way to the coast in Benin, Togo, and Ghana, thus separating the forest zone that covers much of the south of the region into two separat ...

, a region of savanna and dry forest in Togo and Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the nort ...

. The forests are a few hundred kilometres inland from the Atlantic Ocean coast on the southern part of West Africa.

Cultural history

Colonial boundaries are reflected in the modern boundaries between contemporary West African states, cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, often dividing single ethnic groups between two or more states. In contrast to most of Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

, Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

and Southeast Africa, West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

is not populated by Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Nationa ...

-speaking peoples.

Prehistory

West African populations were considerably mobile and interacted with one another throughout the population history of West Africa.archaic humans

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP (Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

).Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

, Middle Stone Age

The Middle Stone Age (or MSA) was a period of African prehistory between the Early Stone Age and the Late Stone Age. It is generally considered to have begun around 280,000 years ago and ended around 50–25,000 years ago. The beginnings of ...

peoples (e.g., Iwo Eleru people,Aterians

The Aterian is a Middle Stone Age (or Middle Palaeolithic) stone tool industry centered in North Africa, from Mauritania to Egypt, but also possibly found in Oman and the Thar Desert. The earliest Aterian dates to c. 150,000 years ago, at th ...

), who dwelled throughout West Africa between MIS 4

Marine isotope stages (MIS), marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages (OIS), are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate, deduced from oxygen isotope data reflecting changes in temperature derived from data f ...

and MIS 2

Marine isotope stages (MIS), marine oxygen-isotope stages, or oxygen isotope stages (OIS), are alternating warm and cool periods in the Earth's paleoclimate, deduced from oxygen isotope data reflecting changes in temperature derived from data f ...

,West African hunter-gatherers

West African hunter-gatherers, West African foragers, or West African pygmies dwelled in western Central Africa earlier than 32,000 BP and dwelled in West Africa between 16,000 BP and 12,000 BP until as late as 1000 BP or some period of time after ...

occupied western Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Co ...

(e.g., Shum Laka

The archaeological site of Shum Laka is the most prominent rockshelter site in the Grasslands region of the Laka Valley, northwest Cameroon. Occupations at this rockshelter date to the Later Stone Age. This region is important to investigations of ...

) earlier than 32,000 BP,Holocene

The Holocene ( ) is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years Before Present (), after the Last Glacial Period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene togeth ...

, Niger-Congo speakers independently created pottery in Ounjougou

Ounjougou is the name of a lieu-dit found in the middle of an important complex of archaeological sites in the Upper Yamé Valley on the Bandiagara Plateau, in Dogon Country, Mali. The Ounjougou archaeological complex consists of over a hundred s ...

, Malibows and arrows

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles (arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was commo ...

,flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring ( indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

...

,antelope

The term antelope is used to refer to many species of even-toed ruminant that are indigenous to various regions in Africa and Eurasia.

Antelope comprise a wastebasket taxon defined as any of numerous Old World grazing and browsing hoofed mamm ...

,domesticated

Domestication is a sustained multi-generational relationship in which humans assume a significant degree of control over the reproduction and care of another group of organisms to secure a more predictable supply of resources from that group. A ...

and shepherded Barbary sheep

The Barbary sheep (''Ammotragus lervia''), also known as aoudad (pronounced �ɑʊdæd is a species of caprine native to rocky mountains in North Africa. While this is the only species in genus ''Ammotragus'', six subspecies have been descri ...

.Round Head Period

Round Head rock art is the earliest painted, monumental form of Central Saharan rock art, which was largely created from 9500 BP to 7500 BP and ceased being created by 3000 BP. The Round Head Period is preceded by the Kel Essuf Period and foll ...

of the Central Sahara, the Pastoral Period followed.aridification

Aridification is the process of a region becoming increasingly arid, or dry. It refers to long term change, rather than seasonal variation.

It is often measured as the reduction of average soil moisture content.

It can be caused by reduced precip ...

of the Green Sahara

The African humid period (AHP) (also known by other names) is a climate period in Africa during the late Pleistocene and Holocene geologic epochs, when northern Africa was wetter than today. The covering of much of the Sahara desert by grasses, ...

, Central Saharan hunter-gatherers

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fungi, ...

and cattle herders may have used seasonal waterways as the migratory route taken to the Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mal ...

and Chad Basin

The Chad Basin is the largest endorheic basin in Africa, centered on Lake Chad. It has no outlet to the sea and contains large areas of semi-arid desert and savanna. The drainage basin is roughly coterminous with the sedimentary basin of the sa ...

of West Africa.savannas

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to ...

and forests

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

of West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

.agriculturalists

An agriculturist, agriculturalist, agrologist, or agronomist (abbreviated as agr.), is a professional in the science, practice, and management of agriculture and agribusiness. It is a regulated profession in Canada, India, the Philippines, the U ...

, akin to the migratory Bantu

Bantu may refer to:

*Bantu languages, constitute the largest sub-branch of the Niger–Congo languages

*Bantu peoples, over 400 peoples of Africa speaking a Bantu language

* Bantu knots, a type of African hairstyle

* Black Association for Nationa ...

agriculturalists and their encounters with Central African hunter-gatherers

The African Pygmies (or Congo Pygmies, variously also Central African foragers, "African rainforest hunter-gatherers" (RHG) or "Forest People of Central Africa") are a group of ethnicities native to Central Africa, mostly the Congo Basin, trad ...

.

Iron Age

The iron industry

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

, in both smelting and forging for tools and weapons, appeared in West Africa by about 2000-1200 BC.[ Though there is some uncertainty, some archaeologists believe that iron metallurgy was developed independently in West Africa.]Nsukka

Nsukka is a town and a Local Government Area in Enugu State, Nigeria. Nsukka shares a common border as a town with Edem, Opi (archaeological site), Ede-Oballa, and Obimo.

The postal code of the area is 410001 and 410002 respectively re ...

region of southeast Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

in what is now Igboland

Igboland ( Standard ), also known as Southeastern Nigeria (but extends into South-Southern Nigeria), is the indigenous homeland of the Igbo people.

It is a cultural and common linguistic region in southern Nigeria. Geographically, it is divide ...

: dating to 2000 BC at the site of Lejja (Eze-Uzomaka 2009)[ and to 750 BC and at the site of Opi (Holl 2009).]Nok culture

The Nok culture (or Nok civilization) is a population whose material remains are named after the Ham village of Nok in Kaduna State of Nigeria, where their terracotta sculptures were first discovered in 1928. The Nok culture appeared in Nige ...

of central Nigeria by about 550 BC and possibly a few centuries earlier.[Minze Stuiver and N.J. Van Der Merwe, 'Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa' ''Current Anthropology'' 1968. Tylecote 1975 (see below)]ironworking

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

technology led to improved weaponry and enabled farmers to expand agricultural productivity and produce surplus crops, which together supported the growth of urban city-states into empires.

By 400 BC, contact had been made with the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

civilisations, including that of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, and a regular trade in gold being conducted with the Saharan Berbers

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, pop2 ...

, as noted by Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

. The trade was fairly small until the camel was introduced, with Mediterranean goods being found in pits as far south as Northern Nigeria

Nigeria ( ), , ig, Naìjíríyà, yo, Nàìjíríà, pcm, Naijá , ff, Naajeeriya, kcg, Naijeriya officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf o ...

. A profitable trade had developed by which West Africans exported gold, cotton cloth, metal ornaments, and leather goods north across the trans-Saharan trade routes, in exchange for copper, horses, salt, textiles, and beads. Later, ivory, slaves, and kola nut

The term kola nut usually refers to the seeds of certain species of plant of the genus ''Cola'', placed formerly in the cocoa family Sterculiaceae and now usually subsumed in the mallow family Malvaceae (as subfamily Sterculioideae). These col ...

s were also traded.

Tichitt culture

In 4000 BCE, the start of sophisticated social structure (e.g., trade of cattle as valued assets) developed among herders amid the Pastoral Period of the south and central Sahara.pastoral

A pastoral lifestyle is that of shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasture. It lends its name to a genre of literature, art, and music (pastorale) that depict ...

culture was intricate, as evidenced by fields of tumuli

A tumulus (plural tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds or ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. A cairn, which is a mound of stones built ...

, lustrous stone rings, axes, and other remnants.Dhar Tichitt

Dhar Tichitt is a Neolithic archaeological site located in the southwestern region of the Sahara Desert, in Mauritania. It is one of several settlement locations along the sandstone cliffs in the area. Dhar Tichitt, Dhar Walata, Dhar Néma, and ...

.Mauritania

Mauritania (; ar, موريتانيا, ', french: Mauritanie; Berber: ''Agawej'' or ''Cengit''; Pulaar: ''Moritani''; Wolof: ''Gànnaar''; Soninke:), officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania ( ar, الجمهورية الإسلامية ...

dates from 2200 BCEDhar Tagant

The Tichitt Culture, or Tichitt Tradition, was created by Mande peoples. In 4000 BCE, the start of sophisticated social structure (e.g., trade of cattle as valued assets) developed among herders amid the Pastoral Period of the Sahara. Saharan pa ...

, Dhar Tichitt, and Dhar Walata included a four-tiered hierarchal social structure, farming

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled peopl ...

of cereals

A cereal is any grass cultivated for the edible components of its grain (botanically, a type of fruit called a caryopsis), composed of the endosperm, germ, and bran. Cereal grain crops are grown in greater quantities and provide more food ...

, metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sc ...

, numerous funerary

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect ...

tombs, and a rock art

In archaeology, rock art is human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type also m ...

tradition.pearl millet

Pearl millet (''Cenchrus americanus'', commonly known as the synonym ''Pennisetum glaucum''; also known as 'Bajra' in Hindi, 'Sajje' in Kannada, 'Kambu' in Tamil, 'Bajeer' in Kumaoni and 'Maiwa' in Hausa, 'Mexoeira' in Mozambique) is the most ...

may have also been independently tamed amid the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several pa ...

.West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali ...

,civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

of the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

,state formation

State formation is the process of the development of a centralized government structure in a situation where one did not exist prior to its development. State formation has been a study of many disciplines of the social sciences for a number of ...

in West Africa.millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets a ...

) may have been a feature of the Tichitt cultural tradition as early as 3rd millennium BCE in Dhar Tichitt.tuyeres

A tuyere or tuyère (; ) is a tube, nozzle or pipe through which air is blown into a furnace or hearth.W. K. V. Gale, The iron and Steel industry: a dictionary of terms (David and Charles, Newton Abbot 1972), 216–217.

Air or oxygen is inj ...

of an oval-shaped low shaft iron furnace, one of 16 located on elevated ground.Iron metallurgy

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

may have developed before the second half of 1st millennium BCE, as indicated by pottery dated between 800 BCE and 200 BCE.copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pink ...

was also utilized.Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

(e.g., at Méma, Macina, Dia Shoma, and Jenne Jeno Jenne can refer to:

* Djenné, a city of Mali

* Jenne, Lazio, a city and comune in the Metropolitan City of Rome, Italy

People with the given name

* Jenne Langhout (1918–2010), Dutch field hockey player

* Jenne Lennon (), American singer

People ...

), where it developed into and persisted as Faïta Facies ceramics between 1300 and 400 BCE among rammed earth

Rammed earth is a technique for constructing foundations, floors, and walls using compacted natural raw materials such as earth, chalk, lime, or gravel. It is an ancient method that has been revived recently as a sustainable building method.

...

architecture and iron metallurgy (which developed after 900 BCE).Ghana Empire

The Ghana Empire, also known as Wagadou ( ar, غانا) or Awkar, was a West African empire based in the modern-day southeast of Mauritania and western Mali that existed from c. 300 until 1100. The Empire was founded by the Soninke people, a ...

developed in the 1st millennium CE.

Nok culture

The Nok peoples and the Gajiganna peoples may have migrated from the Central

The Nok peoples and the Gajiganna peoples may have migrated from the Central Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

, along with pearl millet and pottery, diverged prior to arriving in the northern region of Nigeria, and thus, settled in their respective locations in the region of Gajiganna and Nok.Nok culture

The Nok culture (or Nok civilization) is a population whose material remains are named after the Ham village of Nok in Kaduna State of Nigeria, where their terracotta sculptures were first discovered in 1928. The Nok culture appeared in Nige ...

may have emerged in 1500 cal BCE and continued to persist until 1 cal BCE.terracotta sculptures

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic where the fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, and architecture, terracotta ...

, through large-scale economic production,slingshots

A slingshot is a small hand-powered projectile weapon. The classic form consists of a Y-shaped frame, with two natural rubber strips or tubes attached to the upper two ends. The other ends of the strips lead back to a pocket that holds the proj ...

, as well as bows and arrows

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles (arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was commo ...

, which may be indicative of Nok people engaging in the hunting

Hunting is the human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest food (i.e. meat) and useful animal products (fur/hide (skin), hide, ...

, or trapping

Animal trapping, or simply trapping or gin, is the use of a device to remotely catch an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including food, the fur trade, hunting, pest control, and wildlife management.

History

Neolithi ...

, of undomesticated animals.goods

In economics, goods are items that satisfy human wants

and provide utility, for example, to a consumer making a purchase of a satisfying product. A common distinction is made between goods which are transferable, and services, which are not ...

, in a dugout canoe.watercraft

Any vehicle used in or on water as well as underwater, including boats, ships, hovercraft and submarines, is a watercraft, also known as a water vessel or waterborne vessel. A watercraft usually has a propulsive capability (whether by sai ...

are paddling

Paddling with regard to watercraft is the act of manually propelling a boat using a paddle. The paddle, which consists of one or two blades joined to a shaft, is also used to steer the vessel. The paddle is not connected to the boat (unlike in ...

.cargo

Cargo consists of bulk goods conveyed by water, air, or land. In economics, freight is cargo that is transported at a freight rate for commercial gain. ''Cargo'' was originally a shipload but now covers all types of freight, including tra ...

, along tributaries

A tributary, or affluent, is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream or main stem (or parent) river or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries and the main stem river drain the surrounding drain ...

(e.g., Gurara River) of the Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mal ...

, and exchanged them in a regional trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exc ...

network.trade routes

A trade route is a logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing goods to reach distant markets, a sing ...

may have extended to the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe ...

coast.maritime history

Maritime history is the study of human interaction with and activity at sea. It covers a broad thematic element of history that often uses a global approach, although national and regional histories remain predominant. As an academic subject, it ...

of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

, there is the earlier Dufuna canoe

The Dufuna canoe is a dugout canoe discovered in 1987 by a Fulani cattle herdsman a few kilometers from the village of Dufuna in the Fune Local Government Area, not far from the Komadugu Gana River, in Yobe State, Nigeria. Radiocarbon dating of ...

, which was constructed approximately 8000 years ago in the northern region of Nigeria; as the second earliest form of water vessel known in Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

, the Nok terracotta depiction of a dugout canoe

A dugout canoe or simply dugout is a boat made from a hollowed tree. Other names for this type of boat are logboat and monoxylon. ''Monoxylon'' (''μονόξυλον'') (pl: ''monoxyla'') is Greek – ''mono-'' (single) + '' ξύλον xylon'' (t ...

was created in the central region of Nigeria during the first millennium BCE.Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

(7th century CE – 15th century CE), Igbo-Ukwu

Igbo-Ukwu (English: ''Great Igbo'') is a town in the Nigerian state of Anambra in the south-central part of the country. The town comprises three quarters namely Obiuno, Ngo, and Ihite (an agglomeration of 4 quarters) with several villages within ...

of Nigeria (9th century CE – 10th century CE), Jenne-Jeno of Mali (11th century CE – 12th century CE), and Ile Ife of Nigeria (11th century CE – 15th century CE) – may have been shaped by the earlier West African clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay pa ...

terracotta

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic where the fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, and architecture, terra ...

tradition of the Nok culture.megalithic

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

stone fence

A fence is a structure that encloses an area, typically outdoors, and is usually constructed from posts that are connected by boards, wire, rails or netting. A fence differs from a wall in not having a solid foundation along its whole length.

...

was constructed around the enclosed settlement site of Kochio.Iron metallurgy

Ferrous metallurgy is the metallurgy of iron and its alloys. The earliest surviving prehistoric iron artifacts, from the 4th millennium BC in Egypt, were made from meteoritic iron-nickel. It is not known when or where the smelting of iron from ...

may have developed in the Nok culture between 750 BCE and 550 BCE, Yoruba

The Yoruba people (, , ) are a West African ethnic group that mainly inhabit parts of Nigeria, Benin, and Togo. The areas of these countries primarily inhabited by Yoruba are often collectively referred to as Yorubaland. The Yoruba constitute ...

kingdom of Ife and the Bini kingdom of Benin

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as the Edo Kingdom, or the Benin Empire ( Bini: ') was a kingdom within what is now southern Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th ce ...

may have been continuations of the traditions of the earlier Nok culture.

Djenné-Djenno

The civilization of Djenné-Djenno

Djenné-Djenno (also Jenne-Jeno; ) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the Niger River Valley in the country of Mali. Literally translated to "ancient Djenné", it is the original site of both Djenné and Mali and is considered to be am ...

was located in the Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mal ...

valley in Mali

Mali (; ), officially the Republic of Mali,, , ff, 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞥆𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 𞤃𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭, Renndaandi Maali, italics=no, ar, جمهورية مالي, Jumhūriyyāt Mālī is a landlocked country in West Africa. Ma ...

and is considered to be among the oldest urbanized centres and the best-known archaeological sites in Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the List of sov ...

. The site is located about away from the modern town of Djenné

Djenné ( Bambara: ߘߖߋߣߣߋ tr. Djenne; also known as Djénné, Jenné and Jenne) is a Songhai people town and an urban commune in the Inland Niger Delta region of central Mali. The town is the administrative centre of the Djenné Cercle, ...

and is believed to have been involved in long-distance trade and possibly the domestication of African rice. The site is believed to exceed , but this is yet to be confirmed from extensive survey work. With the help of archaeological excavations, mainly led by Susan and Roderick McIntosh, the site is known to have been occupied from 250 BCE to 900 CE. The city is believed to have been abandoned and moved to its current location due to the spread of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

and the building of the Great Mosque of Djenné

The Great Mosque of Djenné ( ar, الجامع الكبير في جينيه) is a large brick or adobe building in the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style. The mosque is located in the city of Djenné, Mali, on the flood plain of the Bani R ...

. Previously, it was assumed that advanced trade networks and complex societies did not exist in the region until the arrival of traders from Southwest Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

. However, sites such as Djenné-Djenno disprove this, showing that these traditions flourished in West Africa long before then. Towns similar to Djenné-Jeno also developed at the site of Dia, also in Mali along the Niger River, from around 900 BC.Sub-Saharan African

Sub-Saharan Africa is, geographically, the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lies south of the Sahara. These include West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the African co ...

cultures.Djenné-Djenno

Djenné-Djenno (also Jenne-Jeno; ) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located in the Niger River Valley in the country of Mali. Literally translated to "ancient Djenné", it is the original site of both Djenné and Mali and is considered to be am ...

, which have been dated to 250 BCE.egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

of Djenné-Djenno was likely established by the Mande progenitors of the Bozo people

The Bozo are a Mande ethnic group located predominantly along the Niger River in Mali. The name ''Bozo'' is thought to derive from Bambara ''bo-so'' "straw house"; the people accept it as referring to the whole of the ethnic group but use more ...

, which spanned from 3rd century BCE to 13th century CE.

Serer people

The prehistoric

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The us ...

and ancient history of the Serer people

The Serer people are a West African ethnoreligious group. of modern-day Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

has been extensively studied and documented over the years. Much of the present knowledge of it comes from archaeological discoveries and Serer traditions rooted in the Serer religion

The Serer religion, or ''a ƭat Roog'' ("the way of the Divine"), is the original religious beliefs, practices, and teachings of the Serer people of Senegal in West Africa. The Serer religion believes in a universal supreme deity called Roog ...

.["Vestiges historiques, trémoins matériels du passé clans les pays ]Sereer

The Serer people are a West African ethnoreligious group. ". Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

. 1993. CNRS – ORS TO M[Gravrand, Henry: "La Civilization Sereer – Pangool". Published by Les Nouvelles Editions Africaines du Senegal. 1990. pp, 9, 20 & 77. .]

Material relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains of a saint or the personal effects of the saint or venerated person preserved for purposes of veneration as a tangi ...

s have been found in different Serer countries, most of which refer to the past origins of Serer families, villages, and Serer kingdoms. Some of these Serer relics included gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

, silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag (from the Latin ', derived from the Proto-Indo-European ''h₂erǵ'': "shiny" or "white") and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it exhibits the highest electrical ...

, and metals.laterite

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by ...

megaliths

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

carved in circular structures with stones directed towards the East. The latter are found only in small parts of the ancient Serer kingdom of Saloum

The Kingdom of Saloum (Serer language: ''Saluum'' or ''Saalum'') was a Serer/ Wolof kingdom in present-day Senegal. Its kings may have been of Mandinka/Kaabu origin. The capital of Saloum was the city of Kahone. It was a sister kingdom of S ...

. They are described below.

=Senegambian stone circles

=

The Senegambian stone circles

The Senegambian stone circles are groups of megalithic stone circles that lie in The Gambia north of Janjanbureh and in central Senegal. With an approximate area of 30,000 km²,Laport et al. 2012, p. 410 they are sometimes divided into th ...

are megaliths

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

found in Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

north of Janjanbureh

Janjanbureh or Jangjangbureh is a town, founded in 1832, on Janjanbureh Island, also known as MacCarthy Island, in the Gambia River in eastern Gambia. Until 1995, it was known as Georgetown and was the second largest town in the country. It is th ...

and in central Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

. The megaliths found in Senegal and Gambia are sometimes divided into four large sites: Sine Ngayene and Wanar in Senegal, and Wassu and Kerbatch in the Central River Region in Gambia. Researchers are not certain when these monuments were built, but the generally accepted range is between the third century BCE and the sixteenth century CE. Archaeologists have also found pottery sherds, human burials, and some grave goods and metals.laterite

Laterite is both a soil and a rock type rich in iron and aluminium and is commonly considered to have formed in hot and wet tropical areas. Nearly all laterites are of rusty-red coloration, because of high iron oxide content. They develop by ...

with smooth surfaces.

The construction of the stone monuments shows evidence of a prosperous and organised society based on the amount of labour required to build such structures. The builders of these megaliths are unknown, but some believe that they were Serer people

The Serer people are a West African ethnoreligious group. . This hypothesis comes from the fact that the Serer still use funerary houses like those found at Wanar.

Bura culture

The Bura culture was located in the Middle Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mal ...

valley of Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languages[Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso (, ; , ff, 𞤄𞤵𞤪𞤳𞤭𞤲𞤢 𞤊𞤢𞤧𞤮, italic=no) is a landlocked country in West Africa with an area of , bordered by Mali to the northwest, Niger to the northeast, Benin to the southeast, Togo and Ghana t ...](_blank)

. More specifically, the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

civilization

A civilization (or civilisation) is any complex society characterized by the development of a state, social stratification, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyond natural spoken language (namely, a writing system).

...

exemplified by the Bura culture was centered in the southwestern region of modern Niger and in the southeast region of modern Burkina Faso (previously known as Upper Volta).radio carbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was dev ...

, the Sahelian Bura-Asinda culture may have begun in the 3rd century CE and lasted until the 13th century CE.clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay pa ...

, iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

, and stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

. Along with nearby terracotta jars used in ritual sacrifice, hooked arrowheads

An arrowhead or point is the usually sharpened and hardened tip of an arrow, which contributes a majority of the projectile mass and is responsible for impacting and penetrating a target, as well as to fulfill some special purposes such as si ...

made of iron

Iron () is a chemical element with symbol Fe (from la, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, right in ...

were also found.quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock which was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tec ...

, nose rings made from brass

Brass is an alloy of copper (Cu) and zinc (Zn), in proportions which can be varied to achieve different mechanical, electrical, and chemical properties. It is a substitutional alloy: atoms of the two constituents may replace each other wi ...

, and bracelets made from iron or brass were found on human remains located beneath the terracotta jars.equestrian

The word equestrian is a reference to equestrianism, or horseback riding, derived from Latin ' and ', "horse".

Horseback riding (or Riding in British English)

Examples of this are:

*Equestrian sports

*Equestrian order, one of the upper classes in ...

statuettes.ancient

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

African culture

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

s and with later Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or '' Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the ...

ic-influenced Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of centralized kingdoms or empires that were centered on the Sahel, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara, from the 8th century to the 19th. The wealth of the states came from controlling the trade routes a ...

such as Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Tog ...

, early Mali, later Mali, or Songhai.terracotta

Terracotta, terra cotta, or terra-cotta (; ; ), in its material sense as an earthenware substrate, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic where the fired body is porous.

In applied art, craft, construction, and architecture, terra ...

urns of the Bura culture, which were used for funerary

A funeral is a ceremony connected with the final disposition of a corpse, such as a burial or cremation, with the attendant observances. Funerary customs comprise the complex of beliefs and practices used by a culture to remember and respect ...

purposes, may be related to the Tondidarou

Tondidarou is a small town and megalithic archaeological site in Niafunké Cercle, Timbuktu Region, Mali, northwest of Niafunké, about 150 kilometres south-west of Timbuktu. The site, located on the eastern bank of Lac Tagadji, was discovered by ...

megaliths

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

.

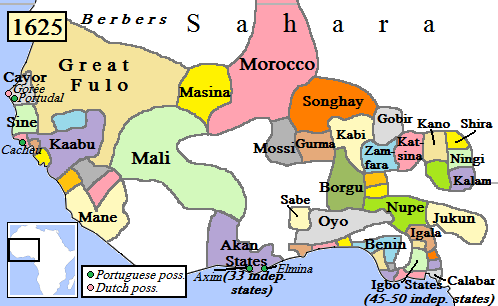

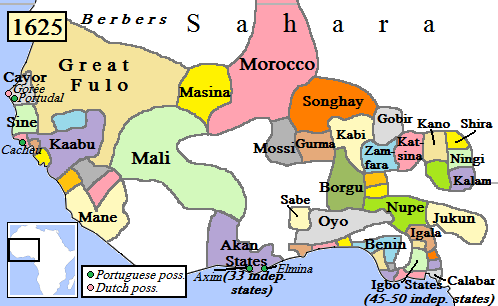

Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms

The Sahelian kingdoms were a series of centralized kingdoms or empires that were centered on the Sahel, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara, from the 8th century to the 19th. The wealth of the states came from controlling the trade routes a ...

were a series of kingdoms or empires that were centred on the Sahel

The Sahel (; ar, ساحل ' , "coast, shore") is a region in North Africa. It is defined as the ecoclimatic and biogeographic realm of transition between the Sahara to the north and the Sudanian savanna to the south. Having a hot semi-arid cli ...

, the area of grasslands south of the Sahara

, photo = Sahara real color.jpg

, photo_caption = The Sahara taken by Apollo 17 astronauts, 1972

, map =

, map_image =

, location =

, country =

, country1 =

, ...

. The wealth of the states came from controlling the trade routes across the desert. Their power came from having large pack animal

A pack animal, also known as a sumpter animal or beast of burden, is an individual or type of working animal used by humans as means of transporting materials by attaching them so their weight bears on the animal's back, in contrast to draft ani ...

s like camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. ...

s and horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

s that were fast enough to keep a large empire under central control and were also useful in battle. All of these empires were also quite decentralised, with member cities having a great deal of autonomy.

The Ghana Empire