The history of independent India began when the country became an independent nation within the

British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

on 15 August 1947. Direct administration by the British, which began in 1858, affected a political and economic unification of the subcontinent. When British rule came to an end in 1947, the subcontinent was partitioned along religious lines into two separate countries—India, with a majority of Hindus, and Pakistan, with a majority of Muslims. Concurrently the Muslim-majority northwest and east of

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

was separated into the

Dominion of Pakistan

Between 14 August 1947 and 23 March 1956, Pakistan was an independent federal dominion in the Commonwealth of Nations, created by the passing of the Indian Independence Act 1947 by the British parliament, which also created the Dominion of ...

, by the

Partition of India

The Partition of British India in 1947 was the change of political borders and the division of other assets that accompanied the dissolution of the British Raj in South Asia and the creation of two independent dominions: India and Pakistan. T ...

. The partition led to a

population transfer

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to economic development. Banishment or exile is ...

of more than 10 million people between India and Pakistan and the death of about one million people.

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

leader

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

became the first

Prime Minister of India

The prime minister of India (IAST: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and their chosen Council of Ministers, despite the president of India being the nominal head of the ...

, but the leader most associated with the

independence struggle,

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, accepted no office. The

constitution adopted in 1950 made India a democratic country, and this democracy has been sustained since then. India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newly independent states.

The nation has faced

religious violence

Religious violence covers phenomena in which religion is either the subject or the object of violent behavior. All the religions of the world contain narratives, symbols, and metaphors of violence and war. Religious violence is violence th ...

,

naxalism,

terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

and regional

separatist

Separatism is the advocacy of cultural, ethnic, tribal, religious, racial, governmental or gender separation from the larger group. As with secession, separatism conventionally refers to full political separation. Groups simply seeking greate ...

insurgencies. India has unresolved territorial disputes with China which in 1962 escalated into the

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tibet ...

, and with

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

which resulted in wars in

1947

It was the first year of the Cold War, which would last until 1991, ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

Events

January

* January–February – Winter of 1946–47 in the United Kingdom: The worst snowfall in the country i ...

,

1965

Events January–February

* January 14 – The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland and the Taoiseach of the Republic of Ireland meet for the first time in 43 years.

* January 20

** Lyndon B. Johnson is sworn in for a full term ...

,

1971 *

The year 1971 had three partial solar eclipses ( February 25, July 22 and August 20) and two total lunar eclipses ( February 10, and August 6).

The world population increased by 2.1% this year, the highest increase in history.

Events

J ...

and

1999

File:1999 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: The funeral procession of King Hussein of Jordan in Amman; the 1999 İzmit earthquake kills over 17,000 people in Turkey; the Columbine High School massacre, one of the first major school shoot ...

. India was neutral in the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because t ...

, and was a leader in the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

. However, it

made a loose alliance with the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

from 1971, when Pakistan was allied with the United States and the People's Republic of China.

India is

a nuclear-weapon state, having conducted its first

nuclear test in 1974, followed by

another five tests in 1998. From the 1950s to the 1980s, India followed

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

-inspired policies. The economy was influenced by

extensive regulation,

protectionism

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulation ...

and public ownership, leading to pervasive

corruption

Corruption is a form of dishonesty or a criminal offense which is undertaken by a person or an organization which is entrusted in a position of authority, in order to acquire illicit benefits or abuse power for one's personal gain. Corruption m ...

and slow economic growth. Beginning in 1991,

economic liberalisation in India has transformed India into the

third largest and one of the

fastest-growing economies in the world despite following

Dirigisme

Dirigisme or dirigism () is an economic doctrine in which the state plays a strong directive (policies) role contrary to a merely regulatory interventionist role over a market economy. As an economic doctrine, dirigisme is the opposite of ''lai ...

economic system. From being a relatively destitute country in its formative years,

the Republic of India has emerged as a fast growing

G20 major economy with high military spending,

and

is seeking a permanent seat in the

United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, ...

.

India has sometimes been referred to as a

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power i ...

and a

potential superpower given its large and growing economy, military and population.

Strategic Vision: America & the Crisis of Global Power

' by Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzeziński ( , ; March 28, 1928 – May 26, 2017), or Zbig, was a Polish-American diplomat and political scientist. He served as a counselor to President Lyndon B. Johnson from 1966 to 1968 and was President Jimmy Carter' ...

, pp. 43–45. Published 2012.

1947–1950: Dominion of India

Independent India's first years were marked with turbulent events—a massive exchange of population with Pakistan, the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 and the integration of over 500

princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

s to form a united nation. Credit for the

political integration of India

After the Indian independence in 1947, the dominion of India was divided into two sets of territories, one under direct British rule, and the other under the suzerainty of the British Crown, with control over their internal affairs remainin ...

is largely attributed to

Vallabhbhai Patel

Vallabhbhai Jhaverbhai Patel (; ; 31 October 1875 – 15 December 1950), commonly known as Sardar, was an Indian lawyer, influential political leader, barrister and statesman who served as the first Deputy Prime Minister and Home Minister of I ...

(deputy Prime Minister of India at the time), who (post-independence and before the death of

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

) teamed up with

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

and Gandhi to ensure that the constitution of independent India would be secular.

Partition of India

An estimated 3.5 million

[Pakistan](_blank)

Encarta

31 October 2009. Hindus

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

and

Sikhs

Sikhs ( or ; pa, ਸਿੱਖ, ' ) are people who adhere to Sikhism (Sikhi), a monotheistic religion that originated in the late 15th century in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent, based on the revelation of Guru Nanak. The ter ...

living in

West Punjab

West Punjab ( pnb, ; ur, ) was a province in the Dominion of Pakistan from 1947 to 1955. The province covered an area of 159,344 km2 (61523 sq mi), including much of the current Punjab province and the Islamabad Capital Territory, but exclu ...

,

North-West Frontier Province

The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP; ps, شمال لویدیځ سرحدي ولایت, ) was a Chief Commissioner's Province of British India, established on 9 November 1901 from the north-western districts of the Punjab Province. Followi ...

,

Baluchistan

Balochistan ( ; bal, بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western Asia, Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian S ...

,

East Bengal

ur,

, common_name = East Bengal

, status = Province of the Dominion of Pakistan

, p1 = Bengal Presidency

, flag_p1 = Flag of British Bengal.svg

, s1 = Ea ...

and

Sind

Sindh (; ; ur, , ; historically romanized as Sind) is one of the four provinces of Pakistan. Located in the southeastern region of the country, Sindh is the third-largest province of Pakistan by land area and the second-largest province ...

migrated to India in fear of domination and suppression in Muslim Pakistan. Communal violence killed an estimated one million Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, and gravely destabilised both dominions along their

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

and

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

boundaries, and the cities of

Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, commer ...

, Delhi and

Lahore

Lahore ( ; pnb, ; ur, ) is the second List of cities in Pakistan by population, most populous city in Pakistan after Karachi and 26th List of largest cities, most populous city in the world, with a population of over 13 million. It is th ...

. The violence was stopped by early September owing to the co-operative efforts of both Indian and Pakistani leaders, and especially due to the efforts of

Mohandas Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (; ; 2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948), popularly known as Mahatma Gandhi, was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalist Quote: "... marks Gandhi as a hybrid cosmopolitan figure who transformed ... anti- ...

, the leader of the Indian freedom struggle, who undertook a ''fast-unto-death'' in Calcutta and later in Delhi to calm people and emphasise peace despite the threat to his life. Both governments constructed large relief camps for incoming and leaving refugees, and the

Indian Army

The Indian Army is the Land warfare, land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Arm ...

was mobilised to provide humanitarian assistance on a massive scale.

The

assassination of Mohandas Gandhi on 30 January 1948 was carried out by

Nathuram Godse

Nathuram Vinayak Godse (19 May 1910 – 15 November 1949) was the assassin of Mahatma Gandhi. He was a Hindu nationalist from Maharashtra who shot Gandhi in the chest three times at point blank range at a multi-faith prayer meeting in B ...

, who held him responsible for partition and charged that Mohandas Gandhi was appeasing Muslims. More than one million people flooded the streets of Delhi to follow the procession to cremation grounds and pay their last respects.

In 1949, India recorded almost 1 million Hindu refugees into

West Bengal

West Bengal (, Bengali: ''Poshchim Bongo'', , abbr. WB) is a state in the eastern portion of India. It is situated along the Bay of Bengal, along with a population of over 91 million inhabitants within an area of . West Bengal is the fou ...

and other states from

East Pakistan

East Pakistan was a Pakistani province established in 1955 by the One Unit Policy, renaming the province as such from East Bengal, which, in modern times, is split between India and Bangladesh. Its land borders were with India and Myanmar, wit ...

, owing to communal violence, intimidation, and repression from Muslim authorities. The plight of the refugees outraged Hindus and Indian nationalists, and the refugee population drained the resources of Indian states, who were unable to absorb them. While not ruling out war, Prime Minister Nehru and Sardar Patel invited

Liaquat Ali Khan

Liaquat Ali Khan ( ur, ; 1 October 1895 – 16 October 1951), also referred to in Pakistan as ''Quaid-e-Millat'' () or ''Shaheed-e-Millat'' ( ur, lit=Martyr of the Nation, label=none, ), was a Pakistani statesman, lawyer, political theoris ...

for talks in Delhi. Although many Indians termed this

appeasement

Appeasement in an international context is a diplomatic policy of making political, material, or territorial concessions to an aggressive power in order to avoid conflict. The term is most often applied to the foreign policy of the UK governme ...

, Nehru signed a pact with Liaquat Ali Khan that pledged both nations to the protection of minorities and creation of minority commissions. Although opposed to the principle, Patel decided to back this pact for the sake of peace, and played a critical role in garnering support from West Bengal and across India, and enforcing the provisions of the pact. Khan and Nehru also signed a trade agreement, and committed to resolving bilateral disputes through peaceful means. Steadily, hundreds of thousands of Hindus returned to East Pakistan, but the thaw in relations did not last long, primarily owing to the Kashmir dispute.

Integration of princely states

British India

The provinces of India, earlier presidencies of British India and still earlier, presidency towns, were the administrative divisions of British governance on the Indian subcontinent. Collectively, they have been called British India. In one ...

consisted of 17 provinces, which existed alongside 565

princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

s. The provinces were given to India or Pakistan, in two particular cases—

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi Language, Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also Romanization, romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the I ...

and

Bengal

Bengal ( ; bn, বাংলা/বঙ্গ, translit=Bānglā/Bôngô, ) is a geopolitical, cultural and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal, predom ...

—after being partitioned. The princes of the princely states, however, were given the right to either remain independent or accede to either dominion. Thus India's leaders were faced with the prospect of inheriting a fragmented nation with independent states and kingdoms dispersed across the mainland. Under the leadership of

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, the new Government of India employed political negotiations backed with the option (and, on several occasions, the use) of military action to ensure the primacy of the central government and of the Constitution then being drafted. Sardar Patel and

V. P. Menon

Rao Bahadur Vappala Pangunni Menon, CSI, CIE (30 September 1893 – 31 December 1965) was an Indian civil servant who served as Secretary to the Government of India in the Ministry of the States, under Sardar Patel.

By appointment fr ...

convinced the rulers of princely states contiguous to India to accede to India. Many rights and privileges of the rulers of the princely states, especially their personal estates and privy purses, were guaranteed to convince them to accede. Some of them were made

Rajpramukh

Rajpramukh was an administrative title in India which existed from India's independence in 1947 until 1956. Rajpramukhs were the appointed governors of certain Indian provinces and states.

Background

The British Indian Empire, which inclu ...

(governor) and Uprajpramukh (deputy governor) of the merged states. Many small princely states were merged to form viable administrative states such as

Saurashra,

PEPSU,

Vindhya Pradesh

Vindhya Pradesh was a former state of India. It occupied an area of 23,603 sq. miles. It was created in 1948 as Union of Baghelkhand and Bundelkhand States, shortly after Indian independence, from the territories of the princely states in the ea ...

and

Madhya Bharat

Madhya Bharat, also known as Malwa Union, was an Indian state in west-central India, created on 28 May 1948 from twenty-five princely states which until 1947 had been part of the Central India Agency, with Jiwajirao Scindia as its Rajpramukh. ...

. Some princely states such as

Tripura

Tripura (, Bengali: ) is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a population of 36.71 lakh ( 3.67 million). It is bordered by Assam and Mizoram to the ea ...

and

Manipur

Manipur () ( mni, Kangleipak) is a state in Northeast India, with the city of Imphal as its capital. It is bounded by the Indian states of Nagaland to the north, Mizoram to the south and Assam to the west. It also borders two regions of ...

acceded later in 1949.

There were three states that proved more difficult to integrate than others:

#

Junagadh

Junagadh () is the headquarters of Junagadh district in the Indian state of Gujarat. Located at the foot of the Girnar hills, southwest of Ahmedabad and Gandhinagar (the state capital), it is the seventh largest city in the state.

Literally ...

(Hindu-majority state with a Muslim Nawab)—a December 1947

plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

resulted in a 99% vote

to merge with India, annulling the controversial accession to Pakistan, which was made by the

Nawab

Nawab ( Balochi: نواب; ar, نواب;

bn, নবাব/নওয়াব;

hi, नवाब;

Punjabi : ਨਵਾਬ;

Persian,

Punjabi ,

Sindhi,

Urdu: ), also spelled Nawaab, Navaab, Navab, Nowab, Nabob, Nawaabshah, Nawabshah or Nobab, ...

against the wishes of the people of the state who were overwhelmingly

Hindu

Hindus (; ) are people who religiously adhere to Hinduism. Jeffery D. Long (2007), A Vision for Hinduism, IB Tauris, , pages 35–37 Historically, the term has also been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for ...

and despite Junagadh not being contiguous with Pakistan.

#

Hyderabad

Hyderabad ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Indian state of Telangana and the ''de jure'' capital of Andhra Pradesh. It occupies on the Deccan Plateau along the banks of the Musi River, in the northern part of Southern Indi ...

(Hindu-majority state with a Muslim nizam)—Patel ordered the Indian army to depose the government of the

Nizam

The Nizams were the rulers of Hyderabad from the 18th through the 20th century. Nizam of Hyderabad (Niẓām ul-Mulk, also known as Asaf Jah) was the title of the monarch of the Hyderabad State ( divided between the state of Telangana, Mar ...

, code-named

Operation Polo

Operation Polo was the code name of the Hyderabad " police action" in September 1948, by the then newly independent Dominion of India against Hyderabad State. It was a military operation in which the Indian Armed Forces invaded the Nizam-ru ...

, after the failure of negotiations, which was done between 13 and 29 September 1948. It was incorporated as a state of India the next year.

# The state of

Jammu and Kashmir Jammu and Kashmir may refer to:

* Kashmir, the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent

* Jammu and Kashmir (union territory), a region administered by India as a union territory

* Jammu and Kashmir (state), a region administered ...

(a Muslim-majority state with a Hindu king) in the far north of the subcontinent quickly became a source of controversy that erupted into the

First Indo-Pakistani War which lasted from 1947 to 1949. Eventually, a United Nations-overseen ceasefire was agreed that left India in control of two-thirds of the contested region.

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

initially agreed to

Mountbatten's proposal that a plebiscite be held in the entire state as soon as hostilities ceased, and a UN-sponsored cease-fire was agreed to by both parties on 1 January 1949. No statewide plebiscite was held, however, for in 1954, after Pakistan began to receive arms from the United States, Nehru withdrew his support. The Indian Constitution came into force in Kashmir on 26 January 1950 with special clauses for the state.

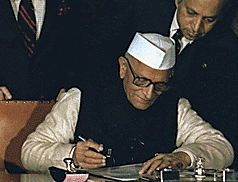

Constitution

The Constitution of India was adopted by the

Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

on 26 November 1949 and became effective on 26 January 1950.

The constitution replaced the

Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act, 1935 was an Act adapted from the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It originally received royal assent in August 1935. It was the longest Act of (British) Parliament ever enacted until the Greater London Authority ...

as the country's fundamental governing document, and the

Dominion of India

The Dominion of India, officially the Union of India,* Quote: “The first collective use (of the word "dominion") occurred at the Colonial Conference (April to May 1907) when the title was conferred upon Canada and Australia. New Zealand and N ...

became the

Republic of India. To ensure

constitutional autochthony

In political science, constitutional autochthony is the process of asserting constitutional nationalism from an external legal or political power. The source of autochthony is the Greek word αὐτόχθων translated as ''springing from the la ...

, its framers repealed prior acts of the

British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

in Article 395. India celebrates its constitution on 26 January as

Republic Day

Republic Day is the name of a holiday in several countries to commemorate the day when they became republics.

List

January 1 January in Slovak Republic

The day of creation of Slovak republic. A national holiday since 1993. Officially cal ...

.

The constitution declares India a

sovereign,

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

, secular, and democratic republic, assures its citizens

justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

,

equality

Equality may refer to:

Society

* Political equality, in which all members of a society are of equal standing

** Consociationalism, in which an ethnically, religiously, or linguistically divided state functions by cooperation of each group's elit ...

, and

liberty

Liberty is the ability to do as one pleases, or a right or immunity enjoyed by prescription or by grant (i.e. privilege). It is a synonym for the word freedom.

In modern politics, liberty is understood as the state of being free within society fr ...

, and endeavours to promote

fraternity.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948 was fought between

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 243 million people, and has the world's second-lar ...

over the

princely state

A princely state (also called native state or Indian state) was a nominally sovereign entity of the British Indian Empire that was not directly governed by the British, but rather by an Indian ruler under a form of indirect rule, subject to ...

of

Kashmir and Jammu from 1947 to 1948. It was the first of four

Indo-Pakistan Wars fought between the two

newly independent nations. Pakistan precipitated the war a few weeks after independence by launching tribal ''lashkar'' (militia) from

Waziristan

Waziristan (Pashto and ur, , "land of the Wazir") is a mountainous region covering the former FATA agencies of North Waziristan and South Waziristan which are now districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province of Pakistan. Waziristan covers some . ...

, in an effort to secure Kashmir, the future of which hung in the balance. The inconclusive result of the war still affects the geopolitics of both countries.

1950s and 1960s

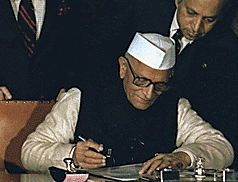

India held its first national elections under the Constitution in 1952, where a turnout of over 60% was recorded. The

National Congress Party won an overwhelming majority, and

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian Anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India du ...

began a second term as Prime Minister. President Prasad was also elected to a second term by the electoral college of the first

Parliament of India

The Parliament of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of the ...

.

Nehru administration (1952–1964)

Prime Minister Nehru led the Congress to major election victories in 1957 and 1962. The Parliament passed extensive reforms that increased the legal rights of women in Hindu society, and further legislated against caste discrimination and

untouchability

Untouchability is a form of social institution that legitimises and enforces practices that are discriminatory, humiliating, exclusionary and exploitative against people belonging to certain social groups. Although comparable forms of discrimin ...

. Nehru advocated a strong initiative to enroll India's children to complete primary education, and thousands of schools, colleges and institutions of advanced learning, such as the

Indian Institutes of Technology, were founded across the nation. Nehru advocated a socialist model for the

economy of India

The economy of India has transitioned from a mixed planned economy to a mixed middle-income developing social market economy with notable state participation in strategic sectors.

*

*

*

* It is the world's fifth-largest economy by nomin ...

—

Five-Year Plans were shaped by the

Soviet model based on centralised and integrated national economic programs—no taxation for Indian farmers, minimum wage and benefits for blue-collar workers, and the

nationalisation of heavy industries such as steel, aviation, shipping, electricity, and mining. Village

common lands were seized, and an extensive public works and industrialisation campaign resulted in the construction of major dams, irrigation canals, roads, thermal and hydroelectric power stations, and many more.

States reorganisation

Potti Sreeramulu

Potti Sreeramulu (IAST: ''Poṭṭi Śreerāmulu''; 16 March 1901 – 15 December 1952), was an Indian freedom fighter and revolutionary. Sreeramulu is revered as ''Amarajeevi'' ("Immortal Being") in the Andhra region for his self-sacrifice for ...

's ''fast-unto-death'', and consequent death for the demand of an

Andhra State

Andhra State (IAST: ; ) was a state in India created in 1953 from the Telugu-speaking northern districts of Madras State. The state was made up of this two distinct cultural regions – Rayalaseema and Coastal Andhra. Andhra State did not incl ...

in 1952 sparked a major re-shaping of the Indian Union. Nehru appointed the States Re-organisation Commission, upon whose recommendations the States Reorganisation Act was passed in 1956. Old states were dissolved and new states created on the lines of shared linguistic and ethnic demographics. The separation of

Kerala

Kerala ( ; ) is a state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile regions of Cochin, Malabar, South ...

and the

Telugu-speaking regions of

Madras State

Madras State was a state of India during the mid-20th century. At the time of its formation in 1950, it included the whole of present-day Tamil Nadu (except Kanyakumari district), Coastal Andhra, Rayalaseema, the Malabar region of North and ...

enabled the creation of an exclusively

Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

* Tamils, an ethnic group native to India and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka also called ilankai tamils

**Tamil Malaysians, Tamil people native to Malaysia

* Tamil language, nativ ...

-speaking state of

Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is a state in southern India. It is the tenth largest Indian state by area and the sixth largest by population. Its capital and largest city is Chennai. Tamil Nadu is the home of the Tamil people, whose Tamil language ...

. On 1 May 1960, the states of

Maharashtra and

Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth ...

were created out of the bilingual

Bombay State, and on 1 November 1966, the larger

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

state was divided into the smaller,

Punjabi-speaking

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

and

Haryanvi

Haryanvi ( ' or '), also known as Bangru, is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in the state of Haryana in India, and to a lesser extent in Delhi. Haryanvi is considered to be part of the dialect group of Western Hindi, which also includes Kharib ...

-speaking

Haryana

Haryana (; ) is an Indian state located in the northern part of the country. It was carved out of the former state of East Punjab on 1 Nov 1966 on a linguistic basis. It is ranked 21st in terms of area, with less than 1.4% () of India's land a ...

states.

C. Rajagopalachari and formation of Swatantra Party

On 4 June 1959, shortly after the Nagpur session of the Indian National Congress,

C. Rajagopalachari

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (10 December 1878 – 25 December 1972), popularly known as Rajaji or C.R., also known as Mootharignar Rajaji (Rajaji'', the Scholar Emeritus''), was an Indian statesman, writer, lawyer, and independence activis ...

,

along with Murari Vaidya of the newly established Forum of Free Enterprise (FFE)

[ Erdman, p. 66] and

Minoo Masani, a

classical liberal

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics; civil liberties under the rule of law with especial emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government, econom ...

and critic of socialist Nehru, announced the formation of the new

Swatantra Party

The Swatantra Party was an Indian classical liberal political party, that existed from 1959 to 1974. It was founded by C. Rajagopalachari in reaction to what he felt was the Jawaharlal Nehru-dominated Indian National Congress's increasingly soci ...

at a meeting in Madras.

[ Erdman, p. 65] Conceived by disgruntled heads of former princely states such as the Raja of Ramgarh, the Maharaja of Kalahandi and the Maharajadhiraja of Darbhanga, the party was conservative in character.

[ Erdman, p. 74][ Erdman, p. 72] Later,

N. G. Ranga,

K. M. Munshi

Kanhaiyalal Maneklal Munshi (; 30 December 1887 – 8 February 1971), popularly known by his pen name Ghanshyam Vyas, was an Indian independence movement activist, politician, writer and educationist from Gujarat state. A lawyer by profession, ...

,

Field Marshal K. M. Cariappa and the Maharaja of Patiala joined the effort.

Rajagopalachari, Masani and Ranga also tried but failed to involve

Jayaprakash Narayan

Jayaprakash Narayan (; 11 October 1902 – 8 October 1979), popularly referred to as JP or ''Lok Nayak'' ( Hindi for "People's leader"), was an Indian independence activist, theorist, socialist and political leader. He is remembered for l ...

in the initiative.

[ Erdman, p. 78]

In his short essay "Our Democracy", Rajagopalachari argued the necessity of a right-wing alternative to the Congress: "since ... the Congress Party has swung to the Left, what is wanted is not an ultra or outer-Left

iz. the CPI or the Praja Socialist Party, PSP but a strong and articulate Right."

Rajagopalachari also said the opposition must: "operate not privately and behind the closed doors of the party meeting, but openly and periodically through the electorate."

He outlined the goals of the Swatantra Party through twenty-one "fundamental principles" in the foundation document.

[ Erdman, p. 188] The party stood for equality and opposed government control over the private sector.

[ Erdman, p. 189][ Erdman, p. 190] Rajagopalachari sharply criticised the bureaucracy and coined the term "

licence-permit Raj" to describe Nehru's elaborate system of permissions and licences required for an individual to set up a private enterprise. Rajagopalachari's personality became a rallying point for the party.

Rajagopalachari's efforts to build an anti-Congress front led to a patch-up with his former adversary

C. N. Annadurai

Conjeevaram Natarajan Annadurai (15 September 1909 – 3 February 1969), popularly known as Anna also known as Arignar Anna or Perarignar Anna (''Anna, the scholar'' or ''Elder Brother''), was an Indian Tamil politician who served as the fo ...

of the

Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; DMK) is a political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu where it is currently the ruling party having a comfortable majority without coalition support and the union territory of Puducherry where it is curre ...

.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Annadurai grew close to Rajagopalachari and sought an alliance with the Swatantra Party for the

1962 Madras Legislative Assembly election

The third legislative assembly election to the Madras state (presently Tamil Nadu) was held on 21 February 1962. The Indian National Congress party, led by K. Kamaraj, won the election. Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam made significant in-roads in the ...

s. Although there were occasional electoral pacts between the Swatantra Party and the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), Rajagopalachari remained non-committal on a formal tie-up with the DMK due to its existing alliance with Communists whom he dreaded.

The Swatantra Party contested 94 seats in the Madras state assembly elections and won six

as well as won 18 parliamentary seats in the

1962 Lok Sabha elections.

Foreign policy and military conflicts

Nehru's foreign policy was the inspiration of the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

, of which India was a co-founder. Nehru maintained friendly relations with both the United States and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, and encouraged the People's Republic of China to join the global community of nations. In 1956, when the

Suez Canal Company

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same b ...

was seized by the Egyptian government, an international conference voted 18–4 to take action against Egypt. India was one of the four backers of Egypt, along with

Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

,

Sri Lanka, and the USSR. India had opposed the

partition of Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Re ...

and the 1956 invasion of the

Sinai by Israel, the United Kingdom and France, but did not oppose the Chinese direct control over

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ) is a region in East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the traditional homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are some other ethnic groups such as Monpa, Taman ...

,

and the suppression of a pro-democracy movement in

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

by the Soviet Union. Although Nehru disavowed nuclear ambitions for India, Canada and France aided India in the development of nuclear power stations for electricity. India also negotiated an agreement in 1960 with Pakistan on the just use of the waters of seven rivers shared by the countries. Nehru had visited Pakistan in 1953, but owing to political turmoil in Pakistan, no headway was made on the Kashmir dispute.

India has fought a total of four

wars/military conflicts with its rival nation Pakistan, two in this period. In the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, fought over the disputed territory of

Kashmir, Pakistan captured one-third of Kashmir (which India claims as its territory), and India captured three-fifths (which Pakistan claims as its territory). In the

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, India attacked Pakistan on all fronts by crossing the international border after attempts by Pakistani troops to infiltrate Indian-controlled Kashmir by crossing the de facto border between India and Pakistan in Kashmir.

In 1961, after continual petitions for a peaceful handover, India

invaded and annexed the Portuguese colony of

Goa

Goa () is a state on the southwestern coast of India within the Konkan region, geographically separated from the Deccan highlands by the Western Ghats. It is located between the Indian states of Maharashtra to the north and Karnataka to the ...

on the west coast of India.

In 1962 China and India engaged in the brief

Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tibet ...

over the border in the

Himalayas

The Himalayas, or Himalaya (; ; ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the planet's highest peaks, including the very highest, Mount Everest. Over 10 ...

. The war was a complete rout for the Indians and led to a refocusing on arms build-up and an improvement in relations with the United States. China withdrew from disputed territory in the contested Chinese

South Tibet

South Tibet is a claimed area by China with the literal translation of the Chinese term '' (), which may refer to different geographic areas:

* The southern part of Tibet, covering the middle reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River Valley between ...

and Indian

North-East Frontier Agency

The North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), originally known as the North-East Frontier Tracts (NEFT), was one of the political divisions in British India, and later the Republic of India until 20 January 1972, when it became the Union Territory of ...

that it crossed during the war. India disputes China's sovereignty over the smaller

Aksai Chin

Aksai Chin is a region administered by China as part of Hotan County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang and Rutog County, Ngari Prefecture, Tibet. It is claimed by India to be a part of its Leh District, Ladakh Union Territory. It is a part of t ...

territory that it controls on the western part of the Sino-Indian border.

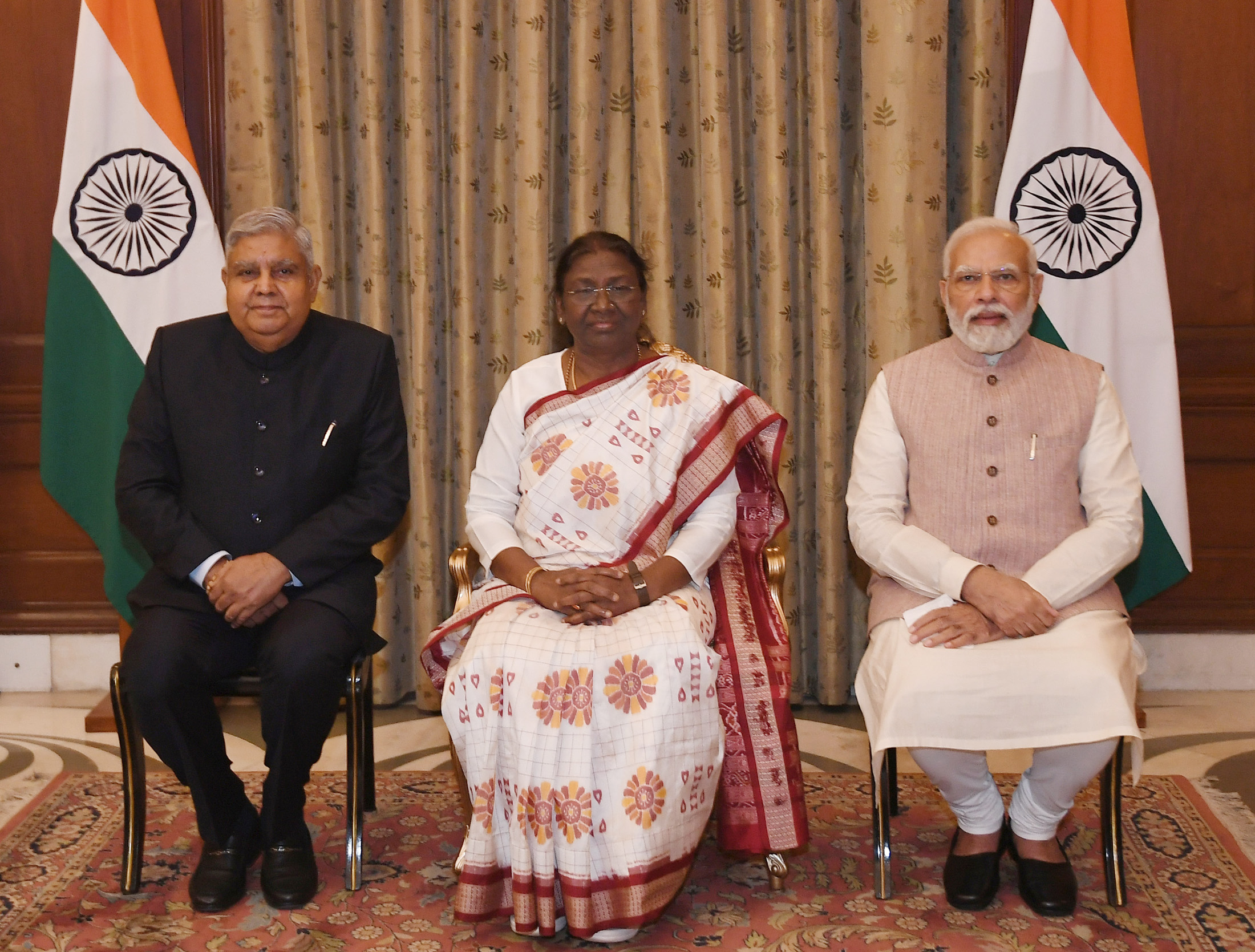

Post-Nehru India

Jawaharlal Nehru died on 27 May 1964, and

Lal Bahadur Shastri

Lal Bahadur Shastri (; 2 October 1904 – 11 January 1966) was an Indian politician and statesman who served as the 2nd Prime Minister of India from 1964 to 1966 and 6th Home Minister of India from 1961 to 1963. He promoted the White Re ...

succeeded him as Prime Minister. In 1965, India and Pakistan again

went to war over Kashmir, but without any definitive outcome or alteration of the Kashmir boundary. The

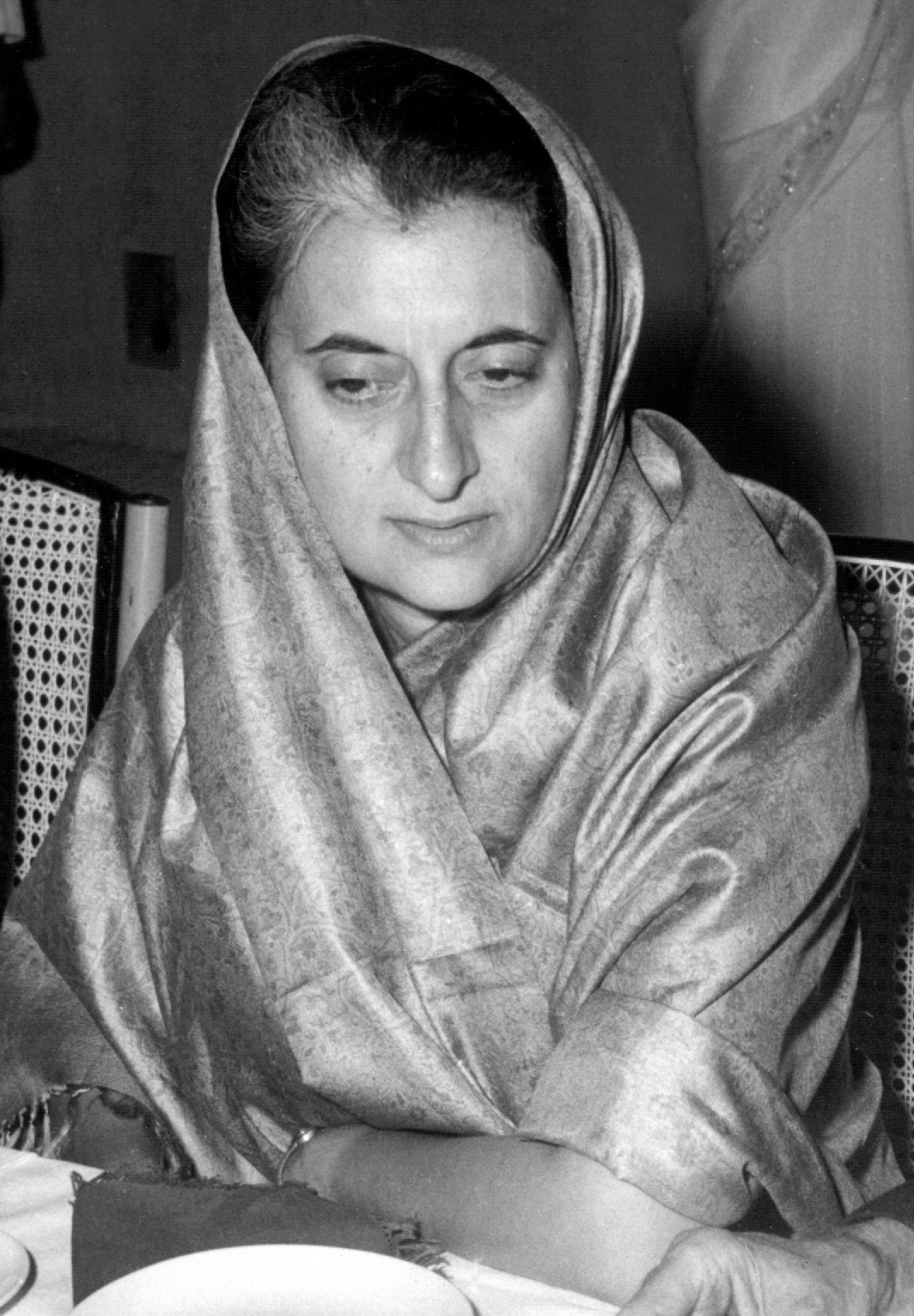

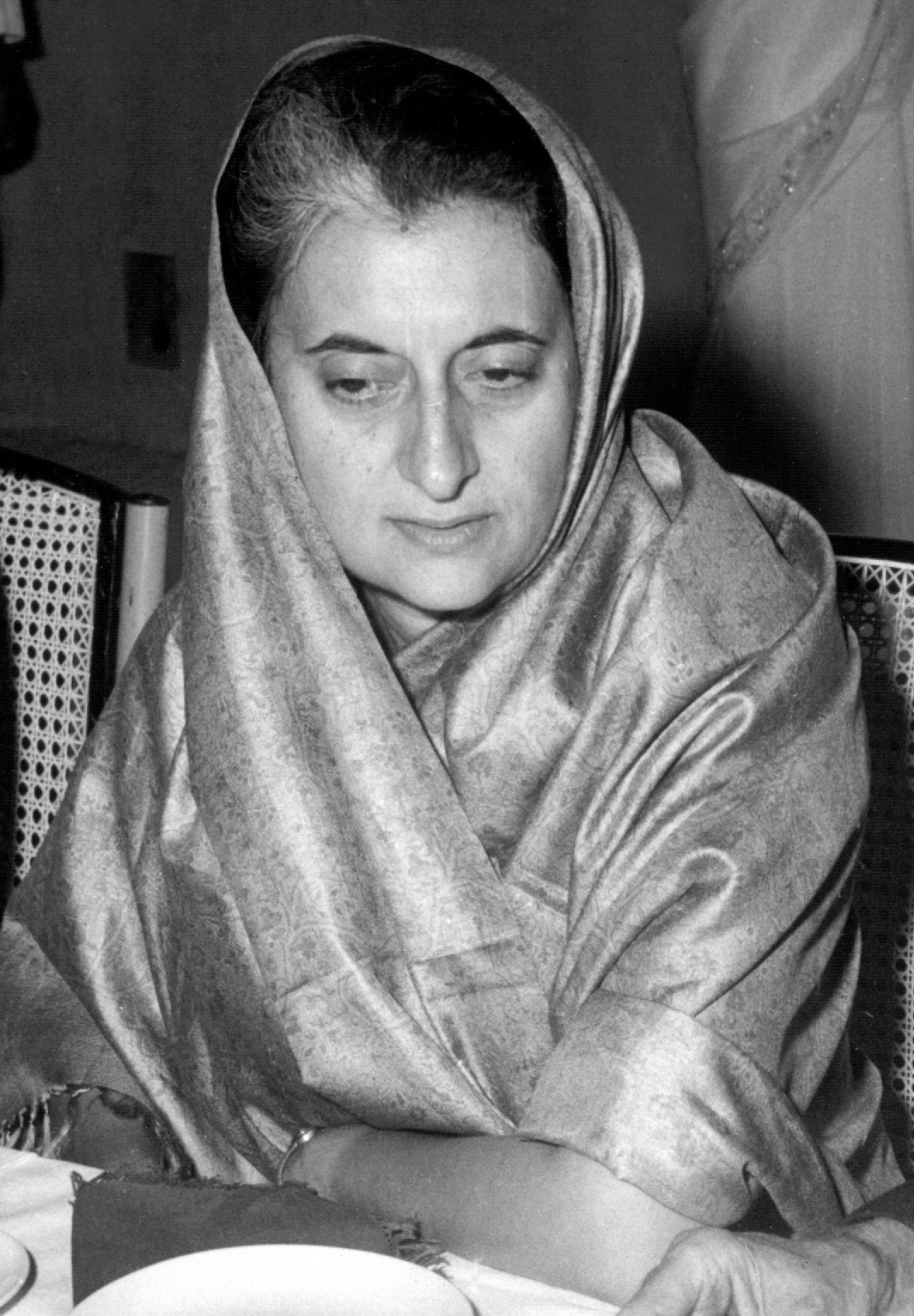

Tashkent Agreement was signed under the mediation of the Soviet government, but Shastri died on the night after the signing ceremony. A leadership election resulted in the elevation of

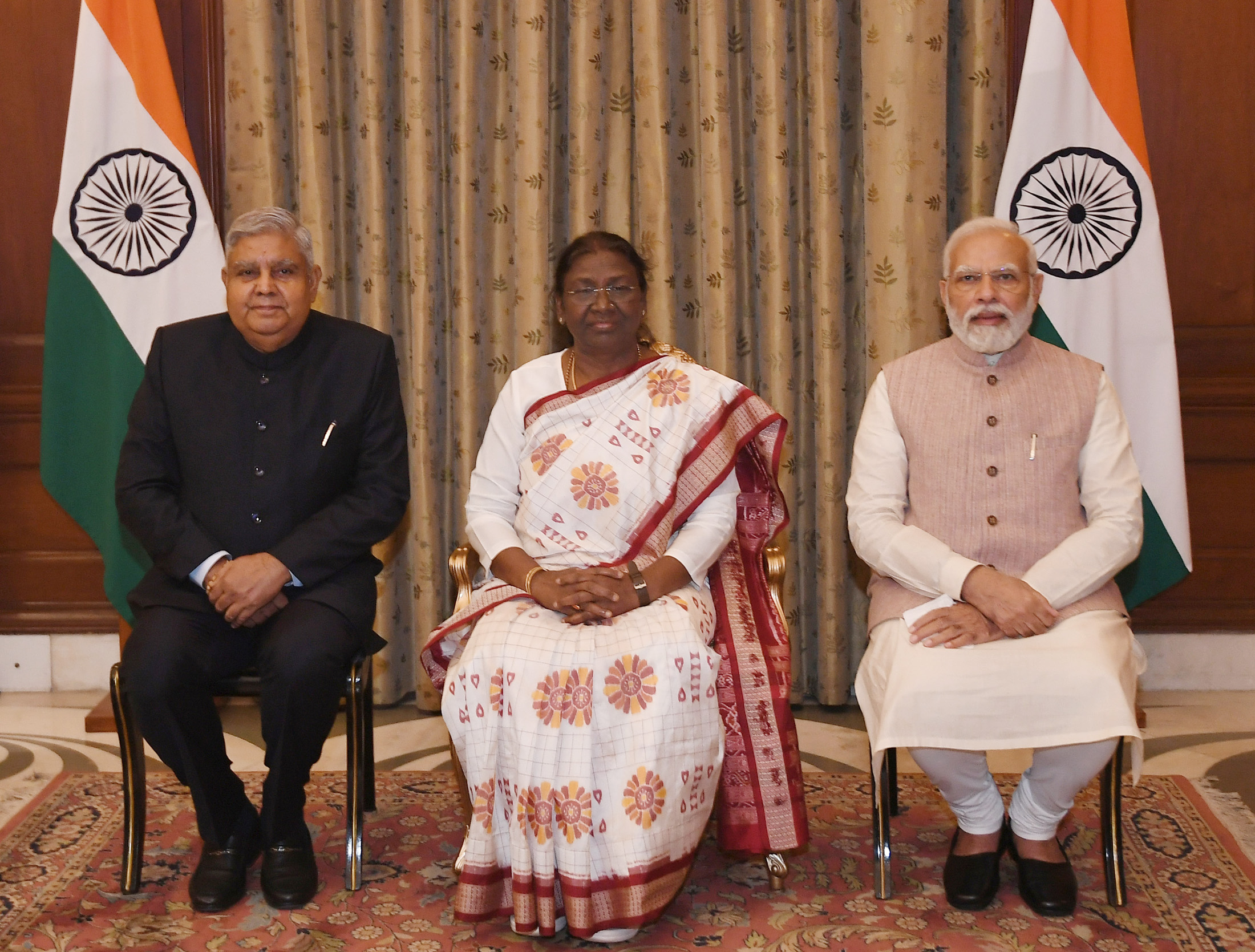

Indira Gandhi, Nehru's daughter who had been serving as Minister for Information and Broadcasting, as the third Prime Minister. She defeated right-wing leader

Morarji Desai

Morarji Ranchhodji Desai (29 February 1896 – 10 April 1995) was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the 4th Prime Minister of India between 1977 to 1979 leading the government formed by the Janata Party. During his ...

. The Congress Party won a reduced majority in the 1967 elections owing to widespread disenchantment over rising prices of commodities, unemployment, economic stagnation, and food crisis. Indira Gandhi had started on a rocky note after agreeing to a

devaluation

In macroeconomics and modern monetary policy, a devaluation is an official lowering of the value of a country's currency within a fixed exchange-rate system, in which a monetary authority formally sets a lower exchange rate of the national curre ...

of the

rupee, which created much hardship for Indian businesses and consumers, and the import of wheat from the United States fell through due to political disputes.

In 1967, India and China again engaged with each other in

Sino-Indian War of 1967

The Nathu La and Cho La clashes, sometimes referred to as the Sino-Indian War of 1967, consisted of a series of border clashes between India and China alongside the border of the Himalayan Kingdom of Sikkim, then an Indian protectorate.

T ...

after the PLA soldiers opened fire on the Indian soldiers who were making a fence on the border in Nathu La.

Morarji Desai entered Gandhi's government as Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister, and with senior Congress politicians attempted to constrain Gandhi's authority. But following the counsel of her political advisor

P. N. Haksar, Gandhi resuscitated her popular appeal by a major shift towards socialist policies. She successfully ended the

Privy Purse

The Privy Purse is the British Sovereign's private income, mostly from the Duchy of Lancaster. This amounted to £20.1 million in net income for the year to 31 March 2018.

Overview

The Duchy is a landed estate of approximately 46,000 acres (200 ...

guarantee for former Indian royalty, and waged a major offensive against party hierarchy over the nationalisation of India's banks. Although resisted by Desai and India's business community, the policy was popular with the masses. When Congress politicians attempted to oust Gandhi by suspending her Congress membership, Gandhi was empowered with a large exodus of members of parliament to her own Congress (R). The bastion of the Indian freedom struggle, the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

, had split in 1969. Gandhi continued to govern with a slim majority.

1970s

In 1971, Indira Gandhi and her Congress (R) were returned to power with a massively increased majority. The nationalisation of banks was carried out, and many other socialist economic and industrial policies enacted. India

intervened in the

Bangladesh War of Independence

The Bangladesh Liberation War ( bn, মুক্তিযুদ্ধ, , also known as the Bangladesh War of Independence, or simply the Liberation War in Bangladesh) was a revolution and armed conflict sparked by the rise of the Bengali n ...

, a civil war taking place in Pakistan's

Bengali

Bengali or Bengalee, or Bengalese may refer to:

*something of, from, or related to Bengal, a large region in South Asia

* Bengalis, an ethnic and linguistic group of the region

* Bengali language, the language they speak

** Bengali alphabet, the w ...

half, after millions of refugees had fled the persecution of the Pakistani army. The clash resulted in the independence of East Pakistan, which became known as

Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

, and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's elevation to immense popularity. Relations with the United States grew strained, and India signed a 20-year treaty of friendship with the Soviet Union—breaking explicitly for the first time from non-alignment. In 1974, India tested

its first nuclear weapon in the desert of

Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; lit. 'Land of Kings') is a state in northern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the largest Indian state by area and the seventh largest by population. It is on India's northwestern s ...

, near

Pokhran

Pokhran is a village and a municipality located, outside of Jaisalmer city in the Jaisalmer district of the Indian state of Rajasthan. It is a remote location in the Thar Desert region and served as the site for India's first underground nucle ...

.

Annexation of Sikkim

In 1973, anti-royalist riots took place in the

Kingdom of Sikkim

The Kingdom of Sikkim (Classical Tibetan and sip, འབྲས་ལྗོངས།, ''Drenjong''), officially Dremoshong (Classical Tibetan and sip, འབྲས་མོ་གཤོངས།) until the 1800s, was a hereditary monar ...

. In 1975, the Prime Minister of

Sikkim

Sikkim (; ) is a state in Northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Province No. 1 of Nepal in the west and West Bengal in the south. Sikkim is also close to the Silig ...

appealed to the

Indian Parliament

The Parliament of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of the ...

for Sikkim to become a state of India. In April of that year, the

Indian Army

The Indian Army is the Land warfare, land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Commander-in-Chief, Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Arm ...

took over the city of

Gangtok and disarmed the Chogyal's palace guards. Thereafter,

a referendum was held in which 97.5 percent of voters supported abolishing the monarchy, effectively approving union with India.

India is said to have stationed 20,000–40,000 troops in a country of only 200,000 during the referendum. On 16 May 1975, Sikkim became the 22nd state of the Indian Union, and the monarchy was abolished. To enable the incorporation of the new state, the

Indian Parliament

The Parliament of India ( IAST: ) is the supreme legislative body of the Republic of India. It is a bicameral legislature composed of the president of India and two houses: the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and the Lok Sabha (House of the ...

amended the

Indian Constitution

The Constitution of India (IAST: ) is the supreme law of India. The document lays down the framework that demarcates fundamental political code, structure, procedures, powers, and duties of government institutions and sets out fundamental ri ...

. First, the

35th Amendment laid down a set of conditions that made Sikkim an "Associate State", a special designation not used by any other state. A month later, the

36th Amendment repealed the 35th Amendment, and made Sikkim a full state, adding its name to the

First Schedule of the Constitution.

Formation of Northeastern states

Assam in 1950s.png, Assam till the 1950s: The new states of Nagaland

Nagaland () is a landlocked state in the northeastern region of India. It is bordered by the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh to the north, Assam to the west, Manipur to the south and the Sagaing Region of Myanmar to the east. Its capital cit ...

, Meghalaya and Mizoram

Mizoram () is a state in Northeast India, with Aizawl as its seat of government and capital city. The name of the state is derived from "Mizo", the self-described name of the native inhabitants, and "Ram", which in the Mizo language means "lan ...

formed in the 1960-70s. From Shillong

Shillong () is a hill station and the capital of Meghalaya, a state in northeastern India, which means "The Abode of Clouds". It is the headquarters of the East Khasi Hills district. Shillong is the 330th most populous city in India with a ...

, the capital of Assam was shifted to Dispur

Dispur (, ) is the capital of the Indian state of Assam and is a suburb at Guwahati.

It became the capital in 1973, when Shillong the erstwhile capital, became the capital of the state of Meghalaya that was carved out of Assam.

Dispur is the ...

, now a part of Guwahati

Guwahati (, ; formerly rendered Gauhati, ) is the biggest city of the Indian state of Assam and also the largest metropolis in northeastern India. Dispur, the capital of Assam, is in the circuit city region located within Guwahati and is the ...

. After the Sino-Indian War

The Sino-Indian War took place between China and India from October to November 1962, as a major flare-up of the Sino-Indian border dispute. There had been a series of violent border skirmishes between the two countries after the 1959 Tibet ...

in 1962, Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh (, ) is a state in Northeastern India. It was formed from the erstwhile North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) region, and became a state on 20 February 1987. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south. It shares ...

was also separated.

Hornbil Festival, Kohima 6.jpg, Hornbill Festival

The Hornbill Festival is an annual festival celebrated from 1 to 10 of December in the Northeastern Indian state of Nagaland. The festival represents all ethnic groups of Nagaland for which it is also called the ''Festival of Festivals''.

Back ...

, Kohima

Kohima (; Angami Naga: ''Kewhira'' ()), is the capital of the Northeastern Indian state of Nagaland. With a resident population of almost 100,000, it is the second largest city in the state. Originally known as ''Kewhira'', Kohima was founded ...

, Nagaland. Nagaland

Nagaland () is a landlocked state in the northeastern region of India. It is bordered by the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh to the north, Assam to the west, Manipur to the south and the Sagaing Region of Myanmar to the east. Its capital cit ...

became a state on 1 December 1963.

Paphal (Musée du Quai Branly) (4489839164).jpg, ''Pakhangba

Pakhangba ( mni, , omp, ) is a primordial deity, often represented in the form of a dragon, in Meitei mythology and religion. He is depicted in the heraldry of Manipur kingdom, which originated in ''paphal'' ( mni, ), the mythical illu ...

'', a heraldic

Heraldry is a discipline relating to the design, display and study of armorial bearings (known as armory), as well as related disciplines, such as vexillology, together with the study of ceremony, rank and pedigree. Armory, the best-known bran ...

dragon of the Meithei tradition and an important emblem among Manipur state symbols. Manipur

Manipur () ( mni, Kangleipak) is a state in Northeast India, with the city of Imphal as its capital. It is bounded by the Indian states of Nagaland to the north, Mizoram to the south and Assam to the west. It also borders two regions of ...

became a state on 21 January 1972.

Meghalaya Abode of the Clouds India Nature in Laitmawsiang Landscape.jpg, Meghalaya is mountainous, the most rain-soaked state of India. Meghalaya

Meghalaya (, or , meaning "abode of clouds"; from Sanskrit , "cloud" + , "abode") is a state in northeastern India. Meghalaya was formed on 21 January 1972 by carving out two districts from the state of Assam: (a) the United Khasi Hills and J ...

became a state on 21 January 1972.

Tripura State Museum Agartala Tripura India.jpg, Ujjayanta Palace

The Ujjayanta Palace(''Nuyungma'' in Tripuri language) is a museum and the former palace of the Kingdom of Tripura situated in Agartala, which is now the capital of the Indian state of Tripura.

The palace was constructed between 1899 and 190 ...

, which houses the Tripura State Museum. Tripura

Tripura (, Bengali: ) is a state in Northeast India. The third-smallest state in the country, it covers ; and the seventh-least populous state with a population of 36.71 lakh ( 3.67 million). It is bordered by Assam and Mizoram to the ea ...

became a state on 21 January 1972.

Golden Pagoda Namsai Arunachal Pradesh.jpg, Golden Pagoda, Namsai

The Golden Pagoda of Namsai, also known as Kongmu Kham, in the Tai-Khamti language, is a Burmese-style Buddhist temple that was opened in 2010. It is located on a complex in Namsai District of Arunachal Pradesh, India and at a distance of f ...

, Arunachal Pradesh, is one of the notable Buddhist temples in India. Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh (, ) is a state in Northeastern India. It was formed from the erstwhile North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) region, and became a state on 20 February 1987. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south. It shares ...

became a state on 20 February 1987.

SHSS building.jpg, A school campus in Mizoram, which has one of the highest literacy rates in India. Mizoram

Mizoram () is a state in Northeast India, with Aizawl as its seat of government and capital city. The name of the state is derived from "Mizo", the self-described name of the native inhabitants, and "Ram", which in the Mizo language means "lan ...

became a state on 20 February 1987.

In the

Northeast India

, native_name_lang = mni

, settlement_type =

, image_skyline =

, image_alt =

, image_caption =

, motto =

, image_map = Northeast india.png

, ...

, the state of

Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

was divided into several states beginning in 1970 within the borders of what was then Assam. In 1963, the Naga Hills district became the 16th state of India under the name of

Nagaland

Nagaland () is a landlocked state in the northeastern region of India. It is bordered by the Indian states of Arunachal Pradesh to the north, Assam to the west, Manipur to the south and the Sagaing Region of Myanmar to the east. Its capital cit ...

. Part of

Tuensang

Tuensang (Pron:/ˌtjuːənˈsæŋ/) is a town located in the north-eastern part of the Indian state of Nagaland. It is the headquarters of the Tuensang District and has a population of 36,774. The town was founded in 1947 for the purpose of admi ...

was added to Nagaland. In 1970, in response to the demands of the

Khasi,

Jaintia and

Garo people

The Garo is a Tibeto-Burman ethnic tribal group from the Indian subcontinent, living mostly in the Indian states of Meghalaya, Assam, Tripura, and Nagaland, and in neighbouring areas of Bangladesh, including Madhupur, Mymensingh, Haluaghat, ...

of the

Meghalaya Plateau, the districts embracing the

Khasi Hills

The Khasi Hills () is a low mountain formation on the Shillong Plateau in Meghalaya state of India. The Khasi Hills are part of the Garo-Khasi-Jaintia range and connects with the Purvanchal Range and larger Patkai Range further east. Khasi Hil ...

,

Jaintia Hills

The Khasi and Jaintia Hills are a mountainous region that was mainly part of Assam and Meghalaya. This area is now part of the present Indian constitutive state of Meghalaya (formerly part of Assam), which includes the present districts of Eas ...

, and

Garo Hills

The Garo Hills (Pron: ˈgɑ:rəʊ) are part of the Garo-Khasi range in Meghalaya, India. They are inhabited by the Garo people. It is one of the wettest places in the world. The range is part of the Meghalaya subtropical forests ecoregion.

De ...

were formed into an autonomous state within Assam; in 1972 this became a separate state under the name of

Meghalaya

Meghalaya (, or , meaning "abode of clouds"; from Sanskrit , "cloud" + , "abode") is a state in northeastern India. Meghalaya was formed on 21 January 1972 by carving out two districts from the state of Assam: (a) the United Khasi Hills and J ...

. In 1972,

Arunachal Pradesh

Arunachal Pradesh (, ) is a state in Northeastern India. It was formed from the erstwhile North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) region, and became a state on 20 February 1987. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south. It shares ...

(the

North-East Frontier Agency

The North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA), originally known as the North-East Frontier Tracts (NEFT), was one of the political divisions in British India, and later the Republic of India until 20 January 1972, when it became the Union Territory of ...

) and

Mizoram

Mizoram () is a state in Northeast India, with Aizawl as its seat of government and capital city. The name of the state is derived from "Mizo", the self-described name of the native inhabitants, and "Ram", which in the Mizo language means "lan ...

(from the

Mizo Hills

The Lushai (Pron: ˌlʊˈʃaɪ) Hills (or Mizo Hills) are a mountain range in Mizoram and Manipur, India. The range is part of the Patkai range system and its highest point is 2,157 m high Phawngpui, also known as 'Blue Mountain'.

Flora and fau ...

in the south) were separated from Assam as union territories; both became states in 1986.

Green revolution and Operation Flood

India's population passed the 500 million mark in the early 1970s, but its long-standing food crisis was resolved with greatly improved agricultural productivity due to the

Green Revolution

The Green Revolution, also known as the Third Agricultural Revolution, was a period of technology transfer initiatives that saw greatly increased crop yields and agricultural production. These changes in agriculture began in developed countrie ...

. The government sponsored modern agricultural implements, new varieties of generic seeds, and increased financial assistance to farmers that increased the yield of food crops such as wheat, rice and corn, as well as commercial crops like cotton, tea, tobacco and coffee. Increased agricultural productivity expanded across the states of the

Indo-Gangetic Plain and the

Punjab

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

.

Under

Operation Flood

Operation Flood, launched on 13 January 1970, was the world's largest dairy development program and a landmark project of India's National Dairy Development Board (NDDB). It transformed India from a milk-deficient nation into the world's larges ...

, the government encouraged the production of milk, which increased greatly, and improved rearing of livestock across India. This enabled India to become self-sufficient in feeding its own population, ending two decades of food imports.

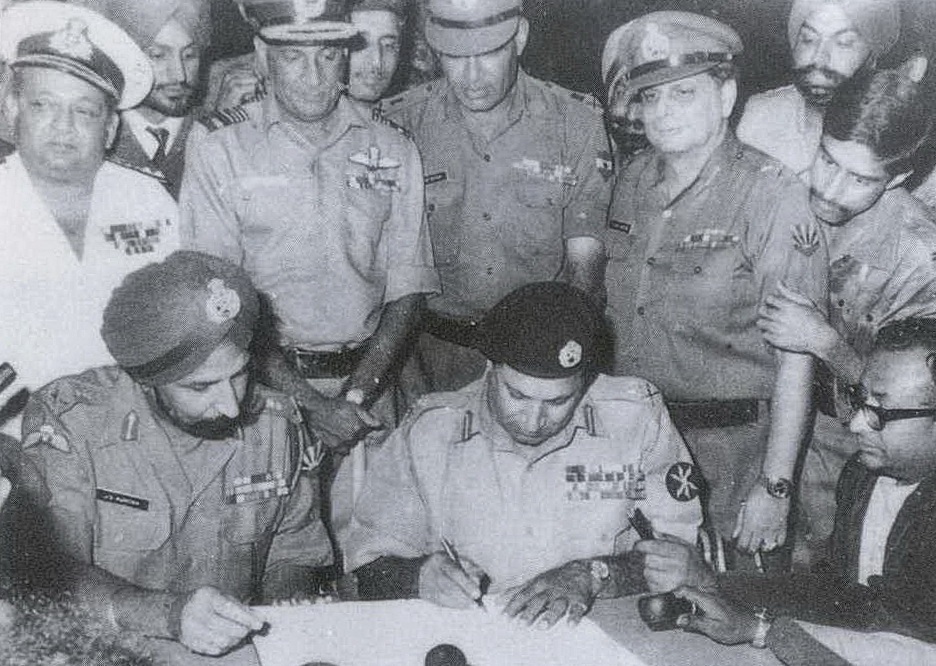

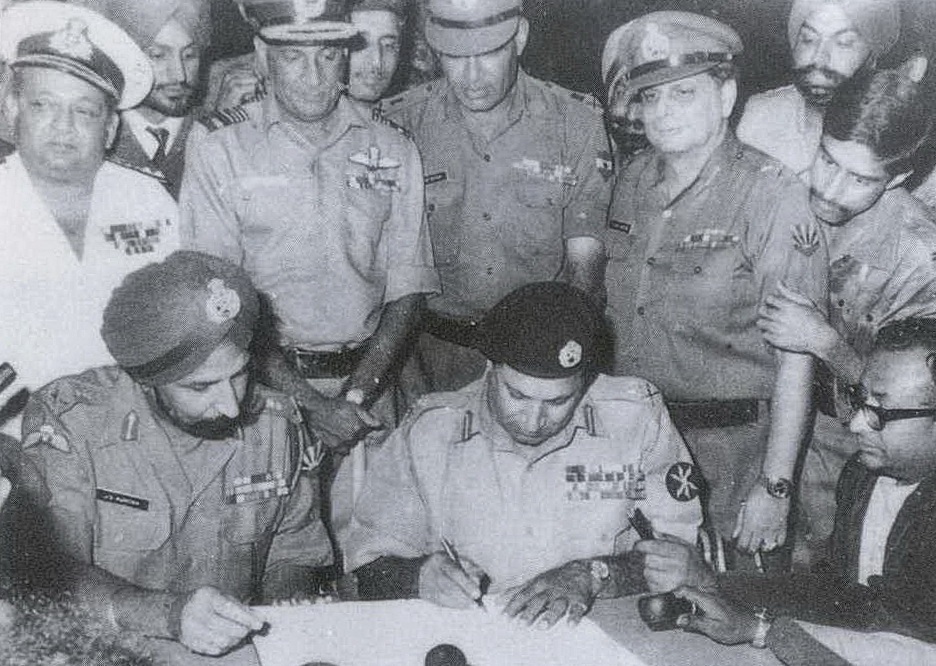

Indo-Pakistan War of 1971

The

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a military confrontation between India and Pakistan that occurred during the Bangladesh Liberation War in East Pakistan from 3 December 1971 until the

Pakistani capitulation in Dhaka on 16 Decem ...

was the third in four wars fought between the two nations. In this war, fought over the issue of

self-rule in East Pakistan, India decisively defeated

Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, resulting in the creation of

Bangladesh

Bangladesh (}, ), officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the eighth-most populous country in the world, with a population exceeding 165 million people in an area of . Bangladesh is among the mos ...

.

Indian Emergency

Economic and social problems, as well as allegations of corruption, caused increasing political unrest across India, culminating in the

Bihar Movement

The JP movement also known as Bihar Movement was a political movement initiated by students in the Indian state of Bihar in 1974 and led by the veteran Gandhian socialist Jayaprakash Narayan, popularly known as JP, against misrule and corruptio ...

. In 1974, the

Allahabad High Court found Indira Gandhi guilty of misusing government machinery for election purposes. Opposition parties conducted nationwide strikes and protests demanding her immediate resignation. Various political parties united under

Jaya Prakash Narayan

Jayaprakash Narayan (; 11 October 1902 – 8 October 1979), popularly referred to as JP or ''Lok Nayak'' (Hindi for "People's leader"), was an Indian independence activist, theorist, socialist and political leader. He is remembered for le ...

to resist what he termed Gandhi's dictatorship. Leading strikes across India that paralysed its economy and administration, Narayan even called for the Army to oust Gandhi. In 1975, Gandhi advised President

Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed

Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed (13 May 1905 – 11 February 1977) was an Indian lawyer and politician who served as the fifth president of India from 1974 to 1977.

Born in Delhi, Ahmed studied in Delhi and Cambridge and was called to the bar from the ...

to declare a

state of emergency under the constitution, which allowed the central government to assume sweeping powers to defend law and order in the nation. Explaining the breakdown of law and order and threat to national security as her primary reasons, Gandhi suspended many

civil liberties and postponed elections at national and state levels. Non-Congress governments in Indian states were dismissed, and nearly 1,000 opposition political leaders and activists were imprisoned and a programme of compulsory birth control introduced.

Strikes and public protests were outlawed in all forms.

India's economy benefited from an end to paralysing strikes and political disorder. India announced a 20-point programme which enhanced agricultural and industrial production, increasing national growth, productivity, and job growth. But many organs of government and many Congress politicians were accused of corruption and authoritarian conduct. Police officers were accused of arresting and torturing innocent people. Indira's son and political advisor,

Sanjay Gandhi

Sanjay Gandhi (14 December 1946 23 June 1980) was an Indian politician and the younger son of Indira Gandhi and Feroze Gandhi. He was a member of parliament, Lok Sabha and the Nehru–Gandhi family. During his lifetime, he was widely expected ...

, was accused of committing gross excesses—Sanjay was blamed for the Health Ministry carrying out forced

vasectomies of men and

sterilisation of women as a part of the initiative to control population growth, and for the demolition of slums in Delhi near the Turkmen Gate, which left thousands of people dead and many more displaced.

Janata interlude

Indira Gandhi's Congress Party called for general elections in 1977, only to suffer a humiliating electoral defeat at the hands of the

Janata Party

The Janata Party ( JP, lit. ''People's Party'') was a political party that was founded as an amalgam of Indian political parties opposed to the Emergency that was imposed between 1975 and 1977 by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi of the Indian Nati ...

, an

amalgamation

Amalgamation is the process of combining or uniting multiple entities into one form.

Amalgamation, amalgam, and other derivatives may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Amalgam (chemistry), the combination of mercury with another metal

**Pan am ...

of opposition parties.

Morarji Desai

Morarji Ranchhodji Desai (29 February 1896 – 10 April 1995) was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the 4th Prime Minister of India between 1977 to 1979 leading the government formed by the Janata Party. During his ...

became the first non-Congress Prime Minister of India. The Desai administration established tribunals to investigate Emergency-era abuses, and Indira and Sanjay Gandhi were arrested after a report from the

Shah Commission

Shah Commission was a commission of inquiry appointed by Government of India in 1977 to inquire into all the excesses committed in the Indian Emergency (1975 - 77). It was headed by Justice J.C. Shah, a former chief Justice of India.

Backgroun ...

.

In 1979, the coalition crumbled and

Charan Singh formed an interim government. The Janata Party had become intensely unpopular due to its internecine warfare, and a perceived lack of leadership on solving India's serious economic and social problems.

1980s

Indira Gandhi and her Congress Party splinter group, the

Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party but often simply the Congress, is a political party in India with widespread roots. Founded in 1885, it was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British E ...

or simply "Congress(I)", were swept back into power with a large majority in January 1980.

But the rise of an insurgency in Punjab would jeopardise India's security. In

Assam

Assam (; ) is a state in northeastern India, south of the eastern Himalayas along the Brahmaputra and Barak River valleys. Assam covers an area of . The state is bordered by Bhutan and Arunachal Pradesh to the north; Nagaland and Manipur ...

, there were many incidents of communal violence between native villagers and refugees from Bangladesh, as well as settlers from other parts of India. When Indian forces, undertaking

Operation Blue Star

Operation Blue Star was the codename of a military operation which was carried out by Indian security forces between 1 and 10 June 1984 in order to remove Damdami Taksal leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his followers from the building ...

, raided the hideout of self-rule pressing

Khalistan

The Khalistan movement is a Sikh separatist movement seeking to create a homeland for Sikhs by establishing a sovereign state, called Khālistān (' Land of the Khalsa'), in the Punjab region. The proposed state would consist of land that cur ...

militants in the

Golden Temple — Sikhs’ most holy shrine – in

Amritsar, the inadvertent deaths of civilians and damage to the temple building inflamed tensions in the Sikh community across India. The Government used intensive police operations to crush militant operations, but it resulted in many claims of abuse of civil liberties. Northeast India was paralysed owing to the

ULFA's clash with Government forces.

On 31 October 1984, the Prime Minister's own Sikh bodyguards assassinated her, and

1984 anti-Sikh riots

The 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots, also known as the 1984 Sikh Massacre, was a series of organised pogroms against Sikhs in India following the assassination of Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards. Government estimates project that about 2,800 Sikhs ...

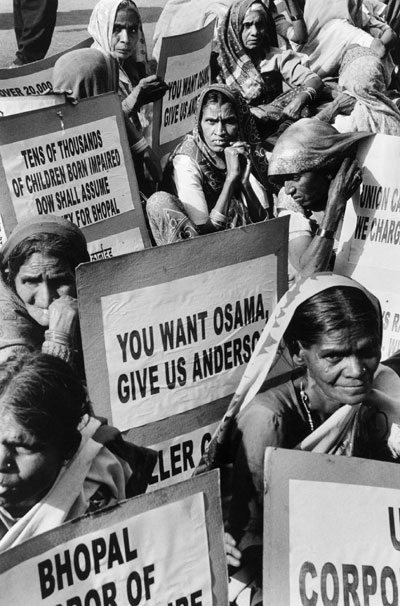

erupted in Delhi and parts of Punjab, causing the deaths of thousands of Sikhs along with terrible pillage, arson, and rape. Senior members of the Congress Party have been implicated in stirring the violence against Sikhs. Government investigation has failed to date to discover the causes and punish the perpetrators, but public opinion blamed Congress leaders for directing attacks on Sikhs in Delhi.

Rajiv Gandhi administration

The Congress party chose

Rajiv Gandhi, Indira's older son, as the next Prime Minister. Rajiv had been elected to Parliament only in 1982, and at 40, was the youngest national political leader and Prime Minister ever. But his youth and inexperience were an asset in the eyes of citizens tired of the inefficacy and corruption of career politicians, and looking for newer policies and a fresh start to resolve the country's long-standing problems. The Parliament was dissolved, and Rajiv led the Congress party to its largest majority in history (over 415 seats out of 545 possible), reaping a sympathy vote over his mother's assassination.

Rajiv Gandhi initiated a series of reforms: the

Licence Raj

The Licence Raj or Permit Raj (''rāj'', meaning "rule" in Hindi) was the system of licences, regulations, and accompanying red tape, that hindered the set up and running of businesses in India between 1947 and 1990. Up to 80 government agenci ...