Heterodontosaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Heterodontosaurus'' is a

The

The  In 1966, a second specimen of ''Heterodontosaurus'' (SAM-PK-K1332) was discovered at the Voyizane locality, in the

In 1966, a second specimen of ''Heterodontosaurus'' (SAM-PK-K1332) was discovered at the Voyizane locality, in the

''Heterodontosaurus'' was a small dinosaur. The most complete skeleton, SAM-PK-K1332, belonged to an animal measuring about in length. Its weight was variously estimated at , , and in separate studies. The closure of

''Heterodontosaurus'' was a small dinosaur. The most complete skeleton, SAM-PK-K1332, belonged to an animal measuring about in length. Its weight was variously estimated at , , and in separate studies. The closure of

The skull of ''Heterodontosaurus'' was small but robustly built. The two most complete skulls measured (

The skull of ''Heterodontosaurus'' was small but robustly built. The two most complete skulls measured ( An unusual feature of the skull was the different-shaped teeth (

An unusual feature of the skull was the different-shaped teeth (

The neck consisted of nine

The neck consisted of nine  The forelimbs were robustly builtSereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 114–132. and proportionally long, measuring 70% of the length of the hind limbs. The

The forelimbs were robustly builtSereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 114–132. and proportionally long, measuring 70% of the length of the hind limbs. The

When it was described in 1962, ''Heterodontosaurus'' was classified as a primitive member of Ornithischia, one of the two main orders of Dinosauria (the other being Saurischia). The authors found it most similar to the poorly known genera ''

When it was described in 1962, ''Heterodontosaurus'' was classified as a primitive member of Ornithischia, one of the two main orders of Dinosauria (the other being Saurischia). The authors found it most similar to the poorly known genera '' By the 1980s, most researchers considered the heterodontosaurids as a distinct family of primitive ornithischian dinosaurs, but with an uncertain position with respect to other groups within the order. By the early 21st century, the prevailing theories were that the family was the

By the 1980s, most researchers considered the heterodontosaurids as a distinct family of primitive ornithischian dinosaurs, but with an uncertain position with respect to other groups within the order. By the early 21st century, the prevailing theories were that the family was the

In 2012, Sereno pointed out several skull and dentition features that suggest a purely or at least preponderantly herbivorous diet. These include the horny beak and the specialised cheek teeth (suitable for cutting off vegetation), as well as fleshy cheeks which would have helped keeping food within the mouth during

In 2012, Sereno pointed out several skull and dentition features that suggest a purely or at least preponderantly herbivorous diet. These include the horny beak and the specialised cheek teeth (suitable for cutting off vegetation), as well as fleshy cheeks which would have helped keeping food within the mouth during

The

The

''Heterodontosaurus'' is known from fossils found in formations of the

''Heterodontosaurus'' is known from fossils found in formations of the

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

of heterodontosaurid dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

that lived during the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-J ...

, 200–190 million years ago. Its only known member species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

, ''Heterodontosaurus tucki'', was named in 1962 based on a skull discovered in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

. The genus name means "different toothed lizard", in reference to its unusual, heterodont dentition; the specific name honours G. C. Tuck, who supported the discoverers. Further specimens have since been found, including an almost complete skeleton in 1966.

Though it was a small dinosaur, ''Heterodontosaurus'' was one of the largest members of its family

Family (from la, familia) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its ...

, reaching between and possibly in length, and weighing between . The skull was elongated, narrow, and triangular when viewed from the side. The front of the jaws were covered in a horny beak. It had three types of teeth; in the upper jaw, small, incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, whe ...

-like teeth were followed by long, canine-like tusks. A gap divided the tusks from the chisel-like cheek-teeth. The body was short with a long tail. The five-fingered forelimbs were long and relatively robust, whereas the hind-limbs were long, slender, and had four toes.

''Heterodontosaurus'' is the eponymous and best-known member of the family Heterodontosauridae. This family is considered a basal (or "primitive") group within the order of ornithischian

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek st ...

dinosaurs, while their closest affinities within the group are debated. In spite of the large tusks, ''Heterodontosaurus'' is thought to have been herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

, or at least omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nutri ...

. Though it was formerly thought to have been capable of quadrupedal locomotion, it is now thought to have been bipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

. Tooth replacement was sporadic and not continuous, unlike its relatives. At least four other heterodontosaurid genera are known from the same geological formation

A geological formation, or simply formation, is a body of rock having a consistent set of physical characteristics ( lithology) that distinguishes it from adjacent bodies of rock, and which occupies a particular position in the layers of rock exp ...

s as ''Heterodontosaurus''.

History of discovery

The

The holotype specimen

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

of ''Heterodontosaurus tucki'' (SAM-PK-K337) was discovered during the British–South African expedition to South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

and Basutoland

Basutoland was a British Crown colony that existed from 1884 to 1966 in present-day Lesotho. Though the Basotho (then known as Basuto) and their territory had been under British control starting in 1868 (and ruled by Cape Colony from 1871), th ...

(former name of Lesotho

Lesotho ( ), officially the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a country landlocked country, landlocked as an Enclave and exclave, enclave in South Africa. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the Thabana Ntlenyana, highest mountains in Sou ...

) in 1961–1962. Today, it is housed in the Iziko South African Museum

The Iziko South African Museum is a South African national museum located in Cape Town. The museum was founded in 1825, the first in the country. It has been on its present site in the Company's Garden since 1897. The museum houses important ...

. It was excavated on a mountain at an altitude of about , at a locality called Tyinindini, in the district of Transkei

Transkei (, meaning ''the area beyond he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei ( xh, iRiphabliki yeTranskei), was an unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa from 1976 to 1994. It was, along with Ciskei, a Ban ...

(sometimes referred to as Herschel) in the Cape Province

The Province of the Cape of Good Hope ( af, Provinsie Kaap die Goeie Hoop), commonly referred to as the Cape Province ( af, Kaapprovinsie) and colloquially as The Cape ( af, Die Kaap), was a province in the Union of South Africa and subsequen ...

of South Africa. The specimen consists of a crushed but nearly complete skull; associated postcranial remains mentioned in the original description could not be located in 2011. The animal was scientifically described

A species description is a formal description of a newly discovered species, usually in the form of a scientific paper. Its purpose is to give a clear description of a new species of organism and explain how it differs from species that have be ...

and named in 1962 by palaeontologists Alfred Walter Crompton

Alfred Walter "Fuzz" Crompton (born 21 February 1927 in Durban) is a South African paleontologist and zoologist.

Crompton studied at the University of Stellenbosch and obtained a bachelor's degree in 1947 and a masters in 1949, in zoology. He c ...

and Alan J. Charig

Alan Jack Charig (1 July 1927 – 15 July 1997) was an English palaeontologist and writer who popularised his subject on television and in books at the start of the wave of interest in dinosaurs in the 1970s.

Charig was, though, first and fo ...

. The genus name refers to the different-shaped teeth, and the specific name honors George C. Tuck, a director of Austin Motor Company

The Austin Motor Company Limited was an English manufacturer of motor vehicles, founded in 1905 by Herbert Austin in Longbridge. In 1952 it was merged with Morris Motors Limited in the new holding company British Motor Corporation (BMC) Limi ...

, who supported the expedition. The specimen was not fully prepared by the time of publication, so only the front parts of the skull and lower jaw were described, and the authors conceded that their description was preliminary, serving mainly to name the animal. It was considered an important discovery, as few early ornithischian

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek st ...

dinosaurs were known at the time. The preparation of the specimen, i.e. the freeing of the bones from the rock matrix, was very time consuming, since they were covered in a thin, very hard, ferruginous layer containing haematite. This could only be removed by a diamond saw

A diamond blade is a saw blade which has diamonds fixed on its edge for cutting hard or abrasive materials. There are many types of diamond blade, and they have many uses, including cutting stone, concrete, asphalt, bricks, coal balls, glass, a ...

, which damaged the specimen.Sereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 4–17.

In 1966, a second specimen of ''Heterodontosaurus'' (SAM-PK-K1332) was discovered at the Voyizane locality, in the

In 1966, a second specimen of ''Heterodontosaurus'' (SAM-PK-K1332) was discovered at the Voyizane locality, in the Elliot Formation

The Elliot Formation is a geological formation and forms part of the Stormberg Group, the uppermost geological group that comprises the greater Karoo Supergroup. Outcrops of the Elliot Formation have been found in the northern Eastern Cape, south ...

of the Stormberg Group of rock formations, above sea level, on Krommespruit Mountain. This specimen included both the skull and skeleton, preserved in articulation (i.e. the bones being preserved in their natural position in relation to each other), with little displacement and distortion of the bones. The postcranial skeleton was briefly described by palaeontologists Albert Santa Luca, Crompton and Charig in 1976. Its forelimb bones had previously been discussed and figured in an article by the palaeontologists Peter Galton

Peter Malcolm Galton (born 14 March 1942 in London) is a British vertebrate paleontologist who has to date written or co-written about 190 papers in scientific journals or chapters in paleontology textbooks, especially on ornithischian and prosa ...

and Robert T. Bakker in 1974, as the specimen was considered significant in establishing that Dinosauria was a monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic gro ...

natural group, whereas most scientists at the time, including the scientists who described ''Heterodontosaurus'', thought that the two main orders Saurischia

Saurischia ( , meaning "reptile-hipped" from the Greek ' () meaning 'lizard' and ' () meaning 'hip joint') is one of the two basic divisions of dinosaurs (the other being Ornithischia), classified by their hip structure. Saurischia and Ornithis ...

and Ornithischia were not directly related. The skeleton was fully described in 1980. SAM-PK-K1332 is the most complete heterodontosaurid skeleton described to date. Though a more detailed description of the skull of ''Heterodontosaurus'' was long promised, it remained unpublished upon the death of Charig in 1997. It was not until 2011 that the skull was fully described by the palaeontologist David B. Norman and colleagues.

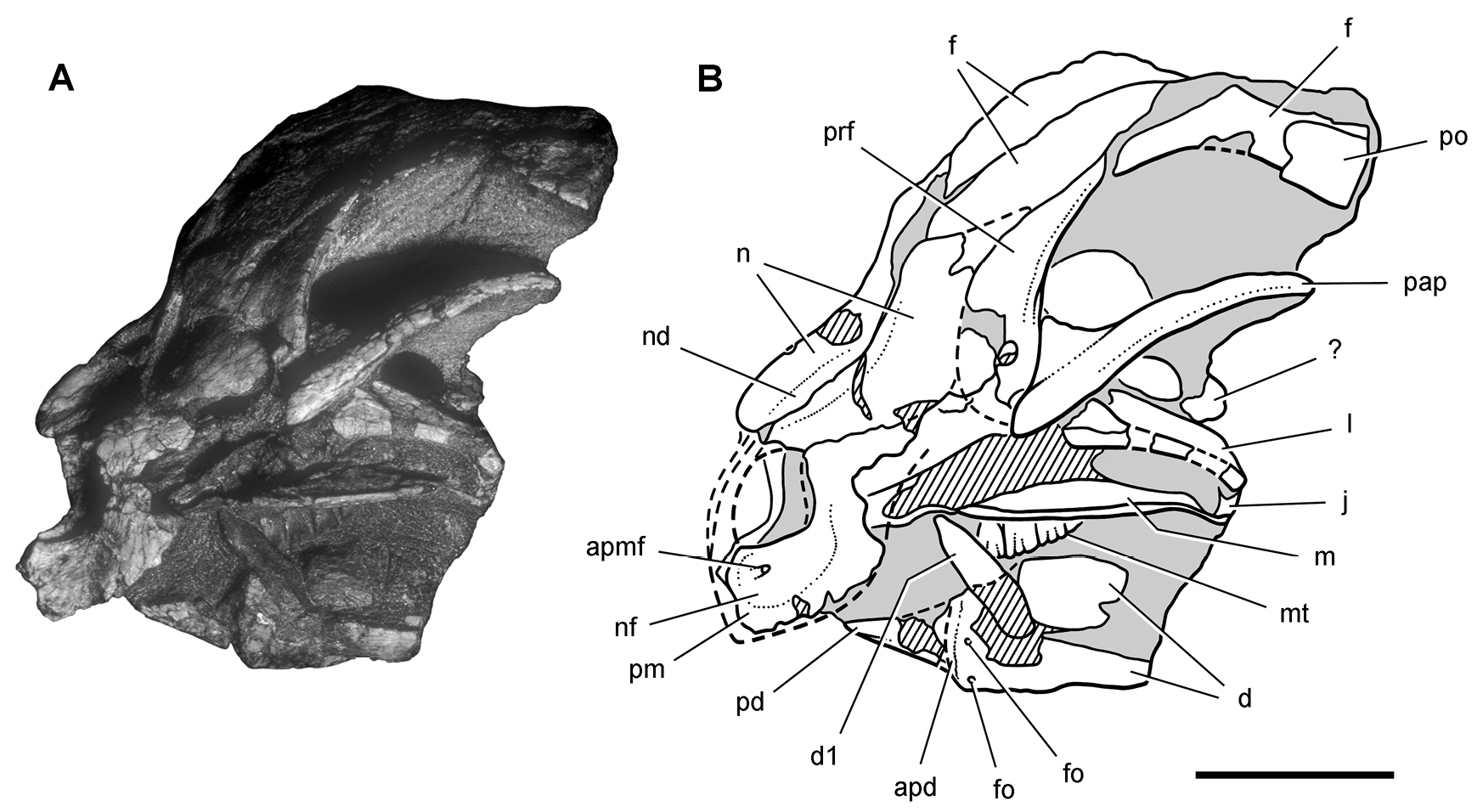

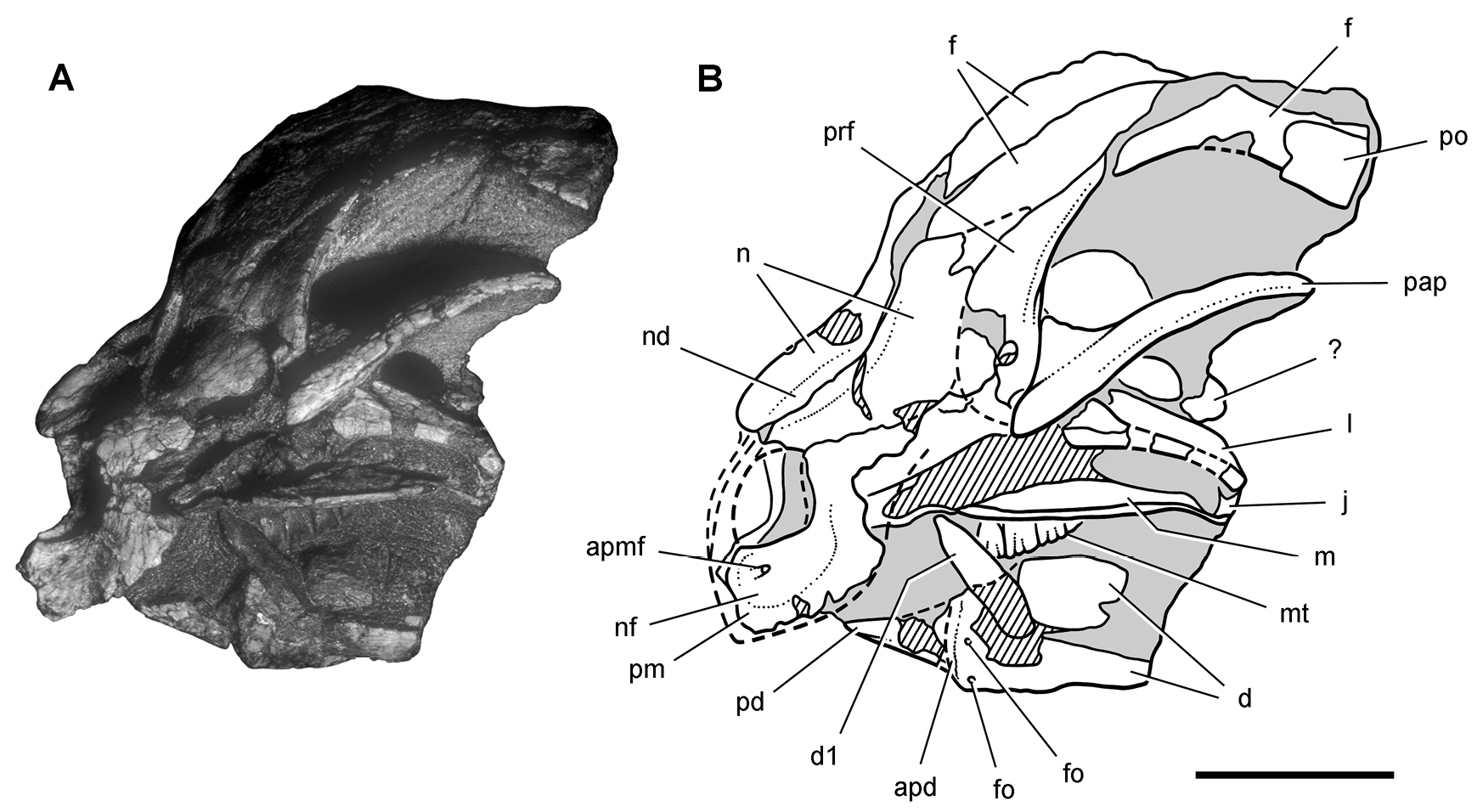

Other specimens referred to ''Heterodontosaurus'' include the front part of a juvenile skull (SAM-PK-K10487), a fragmentary maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The t ...

(SAM-PK-K1326), a left maxilla with teeth and adjacent bones (SAM-PK-K1334), all of which were collected at the Voyizane locality during expeditions in 1966–1967, although the first was only identified as belonging to this genus in 2008. A partial snout (NM QR 1788) found in 1975 on Tushielaw Farm south of Voyizane was thought to belong to ''Massospondylus

''Massospondylus'' ( ; from Greek, (massōn, "longer") and (spondylos, "vertebra")) is a genus of sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Early Jurassic. (Hettangian to Pliensbachian ages, ca. 200–183 million years ago). It was described by S ...

'' until 2011, when it was reclassified as ''Heterodontosaurus''. The palaeontologist Robert Broom

Robert Broom FRS FRSE (30 November 1866 6 April 1951) was a British- South African doctor and palaeontologist. He qualified as a medical practitioner in 1895 and received his DSc in 1905 from the University of Glasgow.

From 1903 to 1910, he ...

discovered a partial skull, possibly in the Clarens Formation

The Clarens Formation is a geological formation found in several localities in Lesotho and in the Free State, KwaZulu-Natal, and Eastern Cape provinces in South Africa. It is the uppermost of the three formations found in the Stormberg Group of ...

of South Africa, which was sold to the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (abbreviated as AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. In Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 26 inter ...

in 1913, as part of a collection that consisted almost entirely of synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

fossils. This specimen (AMNH 24000) was first identified as belonging to a sub-adult ''Heterodontosaurus'' by Sereno, who reported it in a 2012 monograph

A monograph is a specialist work of writing (in contrast to reference works) or exhibition on a single subject or an aspect of a subject, often by a single author or artist, and usually on a scholarly subject.

In library cataloging, ''monograph ...

about the Heterodontosauridae, the first comprehensive review article

A review article is an article that summarizes the current state of understanding on a topic within a certain discipline. A review article is generally considered a secondary source since it may analyze and discuss the method and conclusions i ...

about the family. This review also classified a partial postcranial skeleton (SAM-PK-K1328) from Voyizane as ''Heterodontosaurus''. However, in 2014, Galton suggested it might belong to the related genus '' Pegomastax'' instead, which was named by Sereno based on a partial skull from the same locality. In 2005, a new ''Heterodontosaurus'' specimen (AM 4766) was found in a streambed

A stream bed or streambed is the bottom of a stream or river (bathymetry) or the physical confine of the normal water flow (channel). The lateral confines or channel margins are known as the stream banks or river banks, during all but flood st ...

near Grahamstown

Makhanda, also known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 140,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Port Elizabeth and southwest of East London, Eastern Cape, East London. Makhanda is the lar ...

in the Eastern Cape Province

The Eastern Cape is one of the provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, but its two largest cities are East London and Gqeberha.

The second largest province in the country (at 168,966 km2) after Northern Cape, it was formed in 199 ...

; it was very complete, but the rocks around it were too hard to fully remove. The specimen was therefore scanned at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility

The European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) is a joint research facility situated in Grenoble, France, supported by 22 countries (13 member countries: France, Germany, Italy, the UK, Spain, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, ...

in 2016, to help reveal the skeleton, and aid in research of its anatomy and lifestyle, some of which was published in 2021.

In 1970, palaeontologist Richard A. Thulborn suggested that ''Heterodontosaurus'' was a junior synonym

The Botanical and Zoological Codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

* In botanical nomenclature, a synonym is a scientific name that applies to a taxon that (now) goes by a different scientific name. For example, Linna ...

of the genus ''Lycorhinus

''Lycorhinus'' is a genus of heterodontosaurid ornithischian dinosaur from the Early Jurassic (Hettangian to Sinemurian ages) strata of the Elliot Formation located in the Cape Province, South Africa.

Description

''Lycorhinus'', including the r ...

'', which was named in 1924 with the species ''L. angustidens'', also from a specimen discovered in South Africa. He reclassified the type species as a member of the older genus, as the new combination

''Combinatio nova'', abbreviated ''comb. nov.'' (sometimes ''n. comb.''), is Latin for "new combination". It is used in taxonomic biology literature when a new name is introduced based on a pre-existing name. The term should not to be confused wi ...

''Lycorhinus tucki'', which he considered distinct due to slight differences in its teeth and its stratigraphy. He reiterated this claim in 1974, in the description of a third ''Lycorhinus'' species, ''Lycorhinus consors'', after criticism of the synonymy by Galton in 1973. In 1974, Charig and Crompton agreed that ''Heterodontosaurus'' and ''Lycorhinus'' belonged in the same family, Heterodontosauridae, but disagreed that they were similar enough to be considered congeneric. They also pointed out that the fragmentary nature and poor preservation of the ''Lycorhinus angustidens'' holotype specimen made it impossible to fully compare it properly to ''H. tucki''. In spite of the controversy, neither party had examined the ''L. angustidens'' holotype first hand, but after doing so, palaeontologist James A. Hopson also defended generic separation of ''Heterodontosaurus'' in 1975, and moved ''L. consors'' to its own genus, ''Abrictosaurus

''Abrictosaurus'' (; "wakeful lizard") is a genus of heterodontosaurid dinosaur that lived during the Early Jurassic in what is now in parts of southern Africa such as Lesotho and South Africa. It was a bipedal herbivore or omnivore and was ...

''.

Description

''Heterodontosaurus'' was a small dinosaur. The most complete skeleton, SAM-PK-K1332, belonged to an animal measuring about in length. Its weight was variously estimated at , , and in separate studies. The closure of

''Heterodontosaurus'' was a small dinosaur. The most complete skeleton, SAM-PK-K1332, belonged to an animal measuring about in length. Its weight was variously estimated at , , and in separate studies. The closure of vertebral

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordates ...

sutures on the skeleton indicates that the specimen was an adult, and probably fully grown. A second specimen, consisting of an incomplete skull, indicates that ''Heterodontosaurus'' could have grown substantially larger – up to a length of and with a body mass of nearly . The reason for the size difference between the two specimens is unclear, and might reflect variability within a single species, sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, or the presence of two separate species. The size of this dinosaur has been compared to that of a turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

. ''Heterodontosaurus'' was amongst the largest known members of the family Heterodontosauridae

Heterodontosauridae is a family of ornithischian dinosaurs that were likely among the most basal (primitive) members of the group. Their phylogenetic placement is uncertain but they are most commonly found to be primitive, outside of the group ...

.Sereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 161–162. The family contains some of the smallest known ornithischian dinosaurs – the North American ''Fruitadens

''Fruitadens'' is a genus of heterodontosaurid dinosaur. The name means "Fruita teeth", in reference to Fruita, Colorado (USA), where its fossils were first found. It is known from partial skulls and skeletons from at least four individuals of d ...

'', for example, reached a length of only .

Following the description of the related ''Tianyulong

''Tianyulong'' (Chinese: 天宇龍; Pinyin: ''tiānyǔlóng''; named for the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature where the holotype fossil is housed) is an extinct genus of heterodontosaurid ornithischian dinosaur. The only species is ''T. confuc ...

'' in 2009, which was preserved with hundreds of long, filamentous integuments (sometimes compared to bristles

A bristle is a stiff hair or feather (natural or artificial), either on an animal, such as a pig, a plant, or on a tool such as a brush or broom.

Synthetic types

Synthetic materials such as nylon are also used to make bristles in items such as br ...

) from neck to tail, ''Heterodontosaurus'' has also been depicted with such structures, for example in publications by the palaeontologists Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology, and more recently has examined sociology and theology. He is best known for his work and research on theropod dino ...

and Paul Sereno

Paul Callistus Sereno (born October 11, 1957) is a professor of paleontology at the University of Chicago and a National Geographic "explorer-in-residence" who has discovered several new dinosaur species on several continents, including at sites ...

. Sereno has stated that a heterodontosaur may have looked like a "nimble two-legged porcupine

Porcupines are large rodents with coats of sharp spines, or quills, that protect them against predation. The term covers two families of animals: the Old World porcupines of family Hystricidae, and the New World porcupines of family, Erethizont ...

" in life. The restoration published by Sereno also featured a hypothetical display structure located on the snout, above the nasal fossa (depression).Sereno, P.C. (2012). p. 219.

Skull and dentition

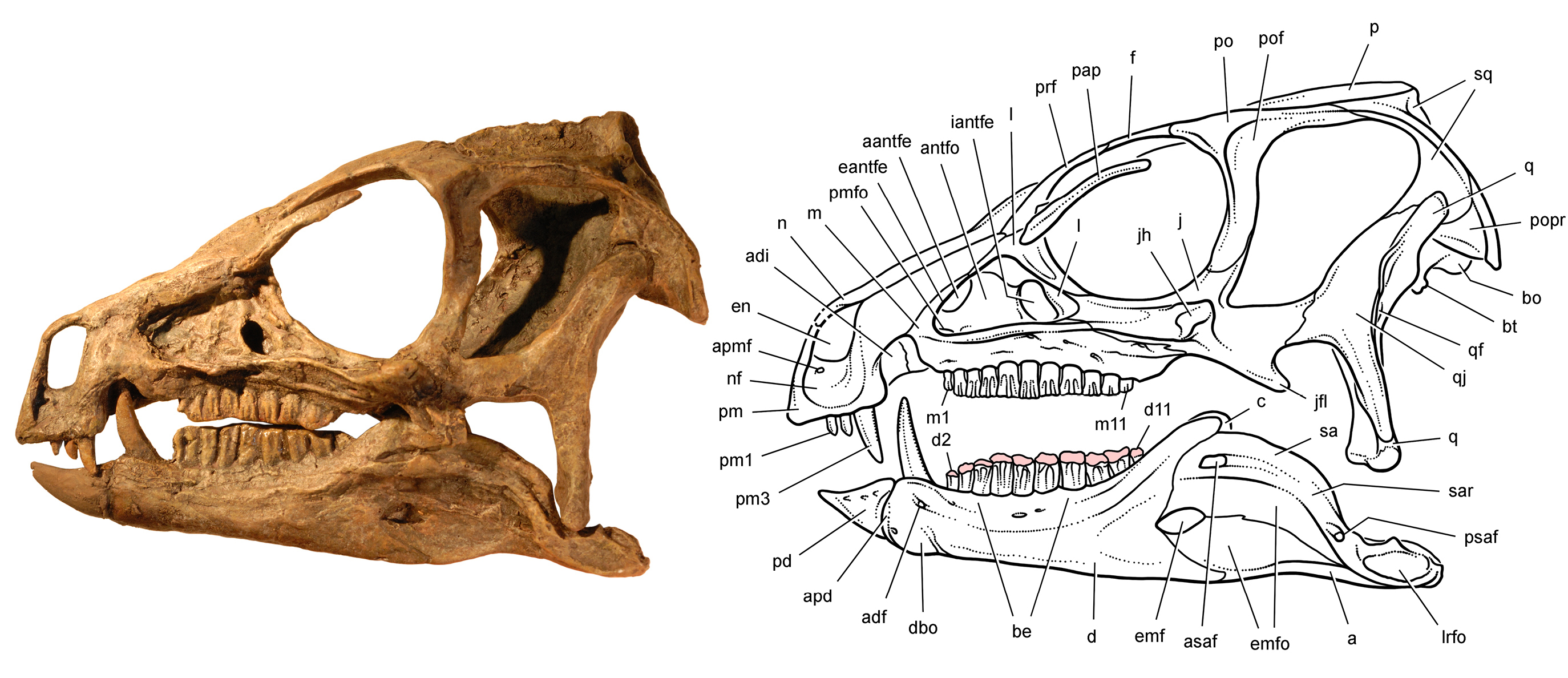

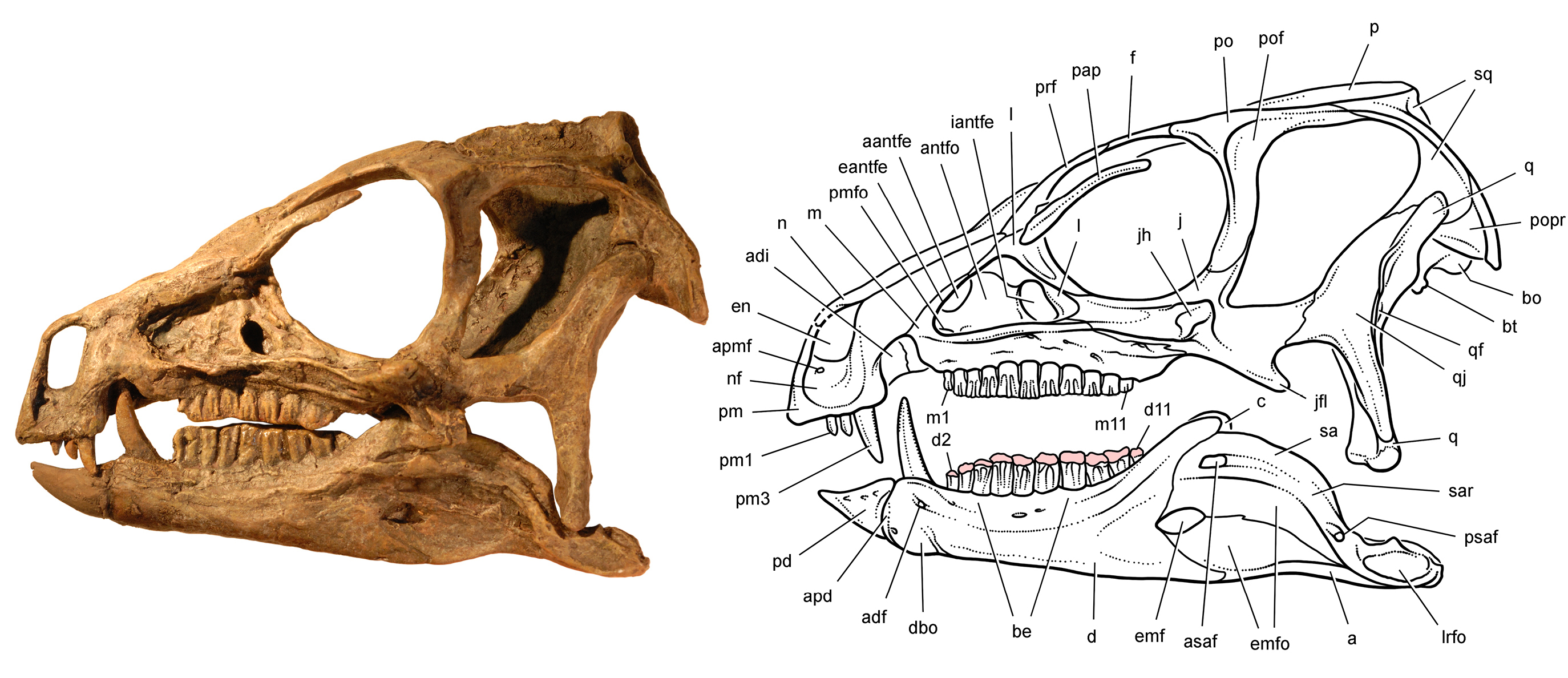

The skull of ''Heterodontosaurus'' was small but robustly built. The two most complete skulls measured (

The skull of ''Heterodontosaurus'' was small but robustly built. The two most complete skulls measured (holotype

A holotype is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism, known to have been used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of several ...

specimen SAM-PK-K337) and (specimen SAM-PK-K1332) in length. The skull was elongated, narrow, and triangular when viewed from the side, with the highest point being the sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are exceptiona ...

, from where the skull sloped down towards the snout tip. The back of the skull ended in a hook-like shape, which was offset to the quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids (reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms upper ...

. The orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a p ...

(eye opening) was large and circular, and a large spur-like bone, the palpebral

An eyelid is a thin fold of skin that covers and protects an eye. The levator palpebrae superioris muscle retracts the eyelid, exposing the cornea to the outside, giving vision. This can be either voluntarily or involuntarily. The human eye ...

, protruded backwards into the upper part of the opening. Below the eye socket, the jugal bone

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anato ...

gave rise to a sideways projecting boss, or horn-like structure. The jugal bone also formed a "blade" that created a slot together with a flange on the pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates, behind the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones () are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the th ...

, for guiding the motion of the lower jaw. Ventrally, the antorbital fossa was bounded by a prominent bony ridge, to which the animal's fleshy cheek would have been attached. It has also been suggested that heterodontosaurs and other basal (or "primitive") orhithischians had lip-like structures like lizards do (based on similarities in their jaws), rather than bridging skin between the upper and lower jaws (such as cheeks). The proportionally large lower temporal fenestra was egg-shaped and tilted back, and located behind the eye opening. The elliptical upper temporal fenestra was visible only looking at the top of the skull. The left and right upper temporal fenestrae were separated by the sagittal crest, which would have provided lateral attachment surfaces for the jaw musculature in the living animal.

The lower jaw tapered towards the front, and the dentary bone

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

(the main part of the lower jaw) was robust. The front of the jaws were covered by a toothless keratinous

Keratin () is one of a family of structural fibrous proteins also known as ''scleroproteins''. Alpha-keratin (α-keratin) is a type of keratin found in vertebrates. It is the key structural material making up scales, hair, nails, feathers, ho ...

beak (or rhamphotheca). The upper beak covered the front of the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammal has b ...

bone and the lower beak covered the predentary

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek st ...

, which are, respectively, the foremost bones of the upper and lower jaw in ornithischians. This is evidenced by the rough surfaces on these structures. The palate was narrow, and tapered towards the front. The external nostril

A nostril (or naris , plural ''nares'' ) is either of the two orifices of the nose. They enable the entry and exit of air and other gasses through the nasal cavities. In birds and mammals, they contain branched bones or cartilages called turbi ...

openings were small, and the upper border of this opening does not seem to have been completely bridged by bone. If not due to breakage, the gap may have been formed by connective tissue

Connective tissue is one of the four primary types of animal tissue, along with epithelial tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue. It develops from the mesenchyme derived from the mesoderm the middle embryonic germ layer. Connective tiss ...

instead of bone. The antorbital fossa, a large depression between the eye and nostril openings, contained two smaller openings. A depression above the snout has been termed the "nasal fossa" or "sulcus". A similar fossa is also seen in ''Tianyulong'', ''Agilisaurus

''Agilisaurus'' (; 'agile lizard') is a genus of ornithischian dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic Period of what is now eastern Asia. It was about 3.5–4 ft (1.2-1.7 m) long, 2 ft (0.6 m) in height and 40 kg in weight.

It has ...

'', and ''Eoraptor

''Eoraptor'' () is a genus of small, lightly built, basal sauropodomorph. One of the earliest-known dinosaurs, it lived approximately 231 to 228 million years ago, during the Late Triassic in Western Gondwana, in the region that is now northwest ...

'', but its function is unknown.

An unusual feature of the skull was the different-shaped teeth (

An unusual feature of the skull was the different-shaped teeth (heterodonty

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals where teeth are differentiated into different forms. For example ...

) for which the genus is named, which is otherwise mainly known from mammals. Most dinosaurs (and indeed most reptiles

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the Class (biology), class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsid, sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, Squamata, squamates (lizar ...

) have a single type of tooth in their jaws, but ''Heterodontosaurus'' had three. The beaked tip of the snout was toothless, whereas the hind part of the premaxilla in the upper jaw had three teeth on each side. The first two upper teeth were small and cone-shaped (comparable to incisors

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wh ...

), while the third on each side was much enlarged, forming prominent, canine-like tusks

Tusks are elongated, continuously growing front teeth that protrude well beyond the mouth of certain mammal species. They are most commonly canine teeth, as with pigs and walruses, or, in the case of elephants, elongated incisors. Tusks share ...

. These first teeth were probably partially encased by the upper beak. The first two teeth in the lower jaw also formed canines, but were much bigger than the upper equivalents.

The canines had fine serrations along the back edge, but only the lower ones were serrated at the front. Eleven tall and chisel-like cheek-teeth lined each side of the posterior parts of the upper jaw, which were separated from the canines by a large diastema

A diastema (plural diastemata, from Greek διάστημα, space) is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition ...

(gap). The cheek-teeth increased gradually in size, with the middle teeth being largest, and decreased in size after this point. These teeth had a heavy coat of enamel on the inwards side, and were adapted for wear (hypsodonty

Hypsodont is a pattern of dentition with high-crowned teeth and enamel extending past the gum line, providing extra material for wear and tear. Some examples of animals with hypsodont dentition are cows and horses; all animals that feed on gritt ...

), and they had long roots, firmly embedded in their sockets. The tusks in the lower jaw fit into an indentation within the diastema of the upper jaw. The cheek-teeth in the lower jaw generally matched those in the upper jaw, though the enamel surface of these were on the outwards side. The upper and lower teeth rows were inset, which created a "cheek-recess" also seen in other ornithischians.

Postcranial skeleton

The neck consisted of nine

The neck consisted of nine cervical vertebra

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In sau ...

e, which would have formed an S-shaped curve, as indicated by the shape of the vertebral bodies in the side view of the skeleton. The vertebral bodies of the anterior cervical vertebrae are shaped like a parallelogram

In Euclidean geometry, a parallelogram is a simple (non- self-intersecting) quadrilateral with two pairs of parallel sides. The opposite or facing sides of a parallelogram are of equal length and the opposite angles of a parallelogram are of equa ...

, those of the middle are rectangular and those of the posterior show a trapezoid

A quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides is called a trapezoid () in American and Canadian English. In British and other forms of English, it is called a trapezium ().

A trapezoid is necessarily a Convex polygon, convex quadri ...

shape. The trunk was short, consisting of 12 dorsal and 6 fused sacral vertebrae. The tail was long compared to the body; although incompletely known, it probably consisted of 34 to 37 caudal vertebrae. The dorsal spine was stiffened by ossified tendons

A tendon or sinew is a tough, high-tensile-strength band of dense fibrous connective tissue that connects muscle to bone. It is able to transmit the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system without sacrificing its ability ...

, beginning with the fourth dorsal vertebra. This feature is present in many other ornithischian dinosaurs and probably countered stress caused by bending forces acting on the spine during bipedal locomotion. In contrast to many other ornithischians, the tail of ''Heterodontosaurus'' lacked ossified tendons, and was therefore probably flexible.

The shoulder blade was capped by an additional element, the suprascapula, which is, among dinosaurs, otherwise only known from ''Parksosaurus

''Parksosaurus'' (meaning " William Parks's lizard") is a genus of neornithischian dinosaur from the early Maastrichtian-age Upper Cretaceous Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada. It is based on most of a partially articulated skeleton a ...

''. In the chest region, ''Heterodontosaurus'' possessed a well-developed pair of sternal plates that resembled those of theropods, but was different from the much simpler sternal plates of other ornithischians. The sternal plates were connected to the rib cage by elements known as sternal ribs. In contrast to other ornithischians, this connection was moveable, allowing the body to expand during breathing. ''Heterodontosaurus'' is the only known ornithischian that possessed gastralia

Gastralia (singular gastralium) are dermal bones found in the ventral body wall of modern crocodilians and tuatara, and many prehistoric tetrapods. They are found between the sternum and pelvis, and do not articulate with the vertebrae. In these ...

(bony elements within the skin between the sternal plates and the pubis of the pelvis). The gastralia were arranged in two lengthwise rows, each containing around nine elements. The pelvis

The pelvis (plural pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of the trunk, between the abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also called bony pelvis, or pelvic skeleton).

The ...

was long and narrow, with a pubis that resembled those possessed by more advanced ornithischians.

The forelimbs were robustly builtSereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 114–132. and proportionally long, measuring 70% of the length of the hind limbs. The

The forelimbs were robustly builtSereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 114–132. and proportionally long, measuring 70% of the length of the hind limbs. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

of the forearm measured 70% of the length of the humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

(forearm bone). The hand was large, approaching the humerus in length, and possessed five fingers equipped for grasping. The second finger was the longest, followed by the third and the first finger (the thumb

The thumb is the first digit of the hand, next to the index finger. When a person is standing in the medical anatomical position (where the palm is facing to the front), the thumb is the outermost digit. The Medical Latin English noun for thumb ...

). The first three fingers ended in large and strong claws. The fourth and fifth fingers were strongly reduced, and possibly vestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

. The phalangeal formula

The phalanges (singular: ''phalanx'' ) are digital bones in the hands and feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are classed as long bones.

...

, which states the number of finger bones in each finger starting from the first, was 2-3-4-3-2.

The hindlimbs were long, slender, and ended in four toes, the first of which (the hallux

Toes are the digits (fingers) of the foot of a tetrapod. Animal species such as cats that walk on their toes are described as being '' digitigrade''. Humans, and other animals that walk on the soles of their feet, are described as being '' pl ...

) did not contact the ground. Uniquely for ornithischians, several bones of the leg and foot were fused: the tibia

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

and fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. Its upper extremity is ...

were fused with upper tarsal bones

In the human body, the tarsus is a cluster of seven articulating bones in each foot situated between the lower end of the tibia and the fibula of the lower leg and the metatarsus. It is made up of the midfoot ( cuboid, medial, intermediate, and ...

(astragalus

''Astragalus'' is a large genus of over 3,000 species of herbs and small shrubs, belonging to the legume family Fabaceae and the subfamily Faboideae. It is the largest genus of plants in terms of described species. The genus is native to tempe ...

and calcaneus

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is the point of the hock.

S ...

), forming a tibiotarsus

The tibiotarsus is the large bone between the femur and the tarsometatarsus in the leg of a bird. It is the fusion of the proximal part of the tarsus with the tibia.

A similar structure also occurred in the Mesozoic Heterodontosauridae. These sm ...

, while the lower tarsal bones were fused with the metatarsal bones

The metatarsal bones, or metatarsus, are a group of five long bones in the foot, located between the tarsal bones of the hind- and mid-foot and the phalanges of the toes. Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are numbered from the medi ...

, forming a tarsometatarsus

The tarsometatarsus is a bone that is only found in the lower leg of birds and some non-avian dinosaurs. It is formed from the fusion of several bones found in other types of animals, and homologous to the mammalian tarsus (ankle bones) and meta ...

. This constellation can also be found in modern birds, where it has evolved independently. The tibiotarsus was about 30% longer than the femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates with ...

. The ungual bones of the toes were claw-like, and not hoof-like as in more advanced ornithischians.

Classification

When it was described in 1962, ''Heterodontosaurus'' was classified as a primitive member of Ornithischia, one of the two main orders of Dinosauria (the other being Saurischia). The authors found it most similar to the poorly known genera ''

When it was described in 1962, ''Heterodontosaurus'' was classified as a primitive member of Ornithischia, one of the two main orders of Dinosauria (the other being Saurischia). The authors found it most similar to the poorly known genera ''Geranosaurus

''Geranosaurus'' (meaning "crane reptile") is a genus of ornithischian dinosaur from the Early Jurassic. It is known only from crushed fragments of the skull, a single jaw bone with nine tooth stubs and limb elements discovered in the Clarens Fo ...

'' and ''Lycorhinus'', the second of which had been considered a therapsid

Therapsida is a major group of eupelycosaurian synapsids that includes mammals, their ancestors and relatives. Many of the traits today seen as unique to mammals had their origin within early therapsids, including limbs that were oriented more ...

stem-mammal until then due to its dentition. They noted some similarities with ornithopods

Ornithopoda () is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs, called ornithopods (), that started out as small, bipedal running grazers and grew in size and numbers until they became one of the most successful groups of herbivores in the Cretaceous world ...

, and provisionally placed the new genus in that group. The palaeontologists Alfred Romer

Alfred Sherwood Romer (December 28, 1894 – November 5, 1973) was an American paleontologist and biologist and a specialist in vertebrate evolution.

Biography

Alfred Romer was born in White Plains, New York, the son of Harry Houston Romer an ...

and Oskar Kuhn

Oskar Kuhn (7 March 1908, Munich – 1990) was a German palaeontologist.

Life and career

Kuhn was educated in Dinkelsbühl and Bamberg and then studied natural science, specialising in geology and paleontology, at the University of Munich, fr ...

independently named the family Heterodontosauridae in 1966 as a family of ornithischian dinosaurs including ''Heterodontosaurus'' and ''Lycorhinus''.Sereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 29–30. Thulborn instead considered these animals as hypsilophodontids, and not a distinct family. Bakker and Galton recognised ''Heterodontosaurus'' as important to the evolution of ornithischian dinosaurs, as its hand pattern was shared with primitive saurischians, and therefore was primitive or basal to both groups. This was disputed by some scientists who believed the two groups had instead evolved independently from " thecodontian" archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avian d ...

ancestors, and that their similarities were due to convergent evolution. Some authors also suggested a relationship, such as descendant/ancestor, between heterodontosaurids and fabrosaurids, both being primitive ornithischians, as well as to primitive ceratopsians

Ceratopsia or Ceratopia ( or ; Greek: "horned faces") is a group of herbivorous, beaked dinosaurs that thrived in what are now North America, Europe, and Asia, during the Cretaceous Period, although ancestral forms lived earlier, in the Jurassic. ...

, such as ''Psittacosaurus

''Psittacosaurus'' ( ; "parrot lizard") is a genus of extinct ceratopsian dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous of what is now Asia, existing between 126 and 101 million years ago. It is notable for being the most species-rich non-avian dinosaur gen ...

'', though the nature of these relations was debated.

By the 1980s, most researchers considered the heterodontosaurids as a distinct family of primitive ornithischian dinosaurs, but with an uncertain position with respect to other groups within the order. By the early 21st century, the prevailing theories were that the family was the

By the 1980s, most researchers considered the heterodontosaurids as a distinct family of primitive ornithischian dinosaurs, but with an uncertain position with respect to other groups within the order. By the early 21st century, the prevailing theories were that the family was the sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

of either the Marginocephalia

Marginocephalia (/mär′jə-nō-sə-făl′ē-ən/ Latin: margin-head) is a clade of ornithischian dinosaurs that is characterized by a bony shelf or margin at the back of the skull. These fringes were likely used for display. There are two clad ...

(which includes pachycephalosaurids and ceratopsians), or the Cerapoda

Cerapoda ("ceratopsians" and "ornithopods") is a clade of the dinosaur order Ornithischia, that includes pachycephalosaurs, ceratopsians and ornithopods

Classification

Cerapoda is divided into two groups: Ornithopoda ("bird-foot") and Marginoc ...

(the former group plus ornithopods), or as one of the most basal radiations of ornithischians, before the split of the Genasauria

Genasauria is a clade of extinct beaked, primarily herbivorous dinosaurs. Paleontologist Paul Sereno first named Genasauria in 1986. The name Genasauria is derived from the Latin word ''gena'' meaning ‘cheek’ and the Greek word ''saúra'' (� ...

(which includes the derived ornithischians). Heterodontosauridae was defined as a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic – that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants – on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

by Sereno in 1998 and 2005, and the group shares skull features such as three or fewer teeth in each premaxilla, caniniform teeth followed by a diastema, and a jugal horn below the eye. In 2006, palaeontologist Xu Xing and colleagues named the clade Heterodontosauriformes, which included Heterodontosauridae and Marginocephalia, since some features earlier only known from heterodontosaurs were also seen in the basal ceratopsian genus ''Yinlong

''Yinlong'' (, meaning "hidden dragon") is a genus of basal ceratopsian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic Period of central Asia. It was a small, primarily bipedal herbivore.

Discovery and species

A coalition of American and Chinese paleontologis ...

''.

Many genera have been referred to Heterodontosauridae since the family was erected, yet ''Heterodontosaurus'' remains the most completely known genus, and has functioned as the primary reference point for the group in the palaeontological literature. The cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to d ...

below shows the interrelationships within Heterodontosauridae, and follows the analysis by Sereno, 2012:Sereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 193–206.

Heterodontosaurids persisted from the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch ...

until the Early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous ( geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pro ...

period, and existed for at least a 100 million years. They are known from Africa, Eurasia, and the Americas, but the majority have been found in southern Africa. Heterodontosaurids appear to have split into two main lineages by the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic-J ...

; one with low- crowned teeth, and one with high-crowned teeth (including ''Heterodontosaurus''). The members of these groups are divided biogeographically

Biogeography is the study of the species distribution, distribution of species and ecosystems in geography, geographic space and through evolutionary history of life, geological time. Organisms and biological community (ecology), communities of ...

, with the low-crowned group having been discovered in areas that were once part of Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pan ...

(northern landmass), and the high-crowned group from areas that were part of Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final stages ...

(southern landmass). In 2012, Sereno labelled members of the latter grouping a distinct subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus. Standard nomenclature rules end subfamily botanical names with "-oideae", and zoologi ...

, Heterodontosaurinae. ''Heterodontosaurus'' appears to be the most derived heterodontosaurine, due to details in its teeth, such as very thin enamel, arranged in an asymmetrical pattern. The unique tooth and jaw features of heterodontosaurines appear to be specialisations for effectively processing plant material, and their level of sophistication is comparable to that of later ornithischians.

In 2017, similarities between the skeletons of ''Heterodontosaurus'' and the early theropod

Theropoda (; ), whose members are known as theropods, is a dinosaur clade that is characterized by hollow bones and three toes and claws on each limb. Theropods are generally classed as a group of saurischian dinosaurs. They were ancestrally c ...

''Eoraptor'' were used by palaeontologist Matthew G. Baron and colleagues to suggest that ornithischians should be grouped with theropods in a group called Ornithoscelida

Ornithoscelida () is a proposed clade that includes various major groupings of dinosaurs. An order Ornithoscelida was originally proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley but later abandoned in favor of Harry Govier Seeley's division of Dinosauria into Sau ...

. Traditionally, theropods have been grouped with sauropodomorphs

Sauropodomorpha ( ; from Greek, meaning "lizard-footed forms") is an extinct clade of long-necked, herbivorous, saurischian dinosaurs that includes the sauropods and their ancestral relatives. Sauropods generally grew to very large sizes, had lon ...

in the group Saurischia. In 2020, palaeontologist Paul-Emile Dieudonné and colleagues suggested that members of Heterodontosauridae were basal marginocephalians not forming their own natural group, instead progressively leading to Pachycephalosauria, and were therefore basal members of that group. This hypothesis would reduce the ghost lineage

A ghost lineage is a hypothesized ancestor in a species lineage that has left no fossil evidence yet can be inferred to exist because of gaps in the fossil record or genomic evidence. The process of determining a ghost lineage relies on fossilized ...

of pachycephalosaurs and pull back the origins of ornithopods back to the Early Jurassic. The subfamily Heterodontosaurinae was considered a valid clade within Pachycephalosauria, containing ''Heterodontosaurus'', ''Abrictosaurus'', and ''Lycorhinus''.

Palaeobiology

Diet and tusk function

''Heterodontosaurus'' is commonly regarded as aherbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

dinosaur.Sereno, P.C. (2012). pp. 162–193. In 1974, Thulborn proposed that the tusks of the dinosaur played no important role in feeding; rather, that they would have been used in combat with conspecifics, for display, as a visual threat, or for active defence. Similar functions are seen in the enlarged tusks of modern muntjac

Muntjacs ( ), also known as the barking deer or rib-faced deer, (URL is Google Books) are small deer of the genus ''Muntiacus'' native to South Asia and Southeast Asia. Muntjacs are thought to have begun appearing 15–35 million years ago, ...

s and chevrotain

Chevrotains, or mouse-deer, are small even-toed ungulates that make up the family Tragulidae, the only extant members of the infraorder Tragulina. The 10 extant species are placed in three genera, but several species also are known only ...

s, but the curved tusks of warthogs

''Phacochoerus'' is a genus in the family Suidae, commonly known as warthogs (pronounced ''wart-hog''). They are pigs who live in open and semi-open habitats, even in quite arid regions, in sub-Saharan Africa. The two species were formerly co ...

(used for digging) are dissimilar.

Several more recent studies have raised the possibility that the dinosaur was omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that has the ability to eat and survive on both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize the nutri ...

and used its tusks for prey killing during an occasional hunt. In 2000, Paul Barrett suggested that the shape of the premaxillary teeth and the fine serration

Serration is a saw-like appearance or a row of sharp or tooth-like projections. A serrated cutting edge has many small points of contact with the material being cut. By having less contact area than a smooth blade or other edge, the applied p ...

of the tusks are reminiscent of carnivorous

A carnivore , or meat-eater (Latin, ''caro'', genitive ''carnis'', meaning meat or "flesh" and ''vorare'' meaning "to devour"), is an animal or plant whose food and energy requirements derive from animal tissues (mainly muscle, fat and other sof ...

animals, hinting at facultative carnivory. In contrast, the muntjac lacks serration on its tusks. In 2008, Butler and colleagues argued that the enlarged tusks formed early in the development of the individual, and therefore could not constitute sexual dimorphism. Combat with conspecifics thus is an unlikely function, as enlarged tusks would be expected only in males if they were a tool for combat. Instead, feeding or defence functions are more likely. It has also been suggested that ''Heterodontosaurus'' could have used its jugal bosses to deliver blows during combat, and that the palpebral bone could have protected the eyes against such attacks. In 2011, Norman and colleagues drew attention to the arms and hands, which are relatively long and equipped with large, recurved claws. These features, in combination with the long hindlimbs that allowed for fast running, would have made the animal capable of seizing small prey. As an omnivore, ''Heterodontosaurus'' would have had a significant selection advantage during the dry season when vegetation was scarce.

In 2012, Sereno pointed out several skull and dentition features that suggest a purely or at least preponderantly herbivorous diet. These include the horny beak and the specialised cheek teeth (suitable for cutting off vegetation), as well as fleshy cheeks which would have helped keeping food within the mouth during

In 2012, Sereno pointed out several skull and dentition features that suggest a purely or at least preponderantly herbivorous diet. These include the horny beak and the specialised cheek teeth (suitable for cutting off vegetation), as well as fleshy cheeks which would have helped keeping food within the mouth during mastication

Chewing or mastication is the process by which food is crushed and ground by teeth. It is the first step of digestion, and it increases the surface area of foods to allow a more efficient break down by enzymes. During the mastication process, th ...

. The jaw muscles were enlarged, and the jaw joint was set below the level of the teeth. This deep position of the jaw joint would have allowed an evenly spread bite along the tooth row, in contrast to the scissor-like bite seen in carnivorous dinosaurs. Finally, size and position of the tusks are very different in separate members of the Heterodontosauridae; a specific function in feeding thus appears unlikely. Sereno surmised that heterodontosaurids were comparable to today's peccaries

A peccary (also javelina or skunk pig) is a medium-sized, pig-like hoofed mammal of the family Tayassuidae (New World pigs). They are found throughout Central and South America, Trinidad in the Caribbean, and in the southwestern area of North A ...

, which possess similar tusks and feed on a variety of plant material such as roots, tubers, fruits, seeds and grass. Butler and colleagues suggested that the feeding apparatus of ''Heterodontosaurus'' was specialised to process tough plant material, and that late-surviving members of the family (''Fruitadens'', ''Tianyulong'' and ''Echinodon'') probably showed a more generalised diet including both plants and invertebrates

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

. ''Heterodontosaurus'' was characterised by a strong bite at small gape angles, but the later members were adapted to a more rapid bite and wider gapes. A 2016 study of ornithischian jaw mechanics found that the relative bite forces of ''Heterodontosaurus'' was comparable to that of the more derived ''Scelidosaurus

''Scelidosaurus'' (; with the intended meaning of "limb lizard", from Greek / meaning 'rib of beef' and ''sauros''/ meaning 'lizard')Liddell & Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. is a gen ...

''. The study suggested that the tusks could have played a role in feeding by grazing against the lower beak while cropping vegetation.

Tooth replacement and aestivation

Much controversy has surrounded the question of whether or not, and to what degree, ''Heterodontosaurus'' showed the continuous tooth replacement that is typical for other dinosaurs and reptiles. In 1974 and 1978, Thulborn found that the skulls known at that time lacked any indications of continuous tooth replacement: The cheek teeth of the known skulls are worn uniformly, indicating that they formed simultaneously. Newly erupted teeth are absent. Further evidence was derived from the wear facets of the teeth, which were formed by tooth-to-tooth contact of the lower with the upper dentition. The wear facets were merged into one another, forming a continuous surface along the complete tooth row. This surface indicates that food procession was achieved by back and forth movements of the jaws, not by simple vertical movements which was the case in related dinosaurs such as ''Fabrosaurus

''Fabrosaurus'' ( ) is an extinct genus of ornithischian dinosaur that lived during the Early Jurassic during the Hettangian to Sinemurian stages 199 - 189 mya.Ginsburg, L., (1964), "Decouverte d’un Scelidosaurien (Dinosaure ornithischien) ...

''. Back and forth movements are only possible if the teeth are worn uniformly, again strengthening the case for the lack of a continuous tooth replacement. Simultaneously, Thulborn stressed that a regular tooth replacement was essential for these animals, as the supposed diet consisting of tough plant material would have led to quick abrasion of the teeth. These observations led Thulborn to conclude that ''Heterodontosaurus'' must have replaced its entire set of teeth at once on a regular basis. Such a complete replacement could only have been possible within phases of aestivation

Aestivation ( la, aestas (summer); also spelled estivation in American English) is a state of animal dormancy, similar to hibernation, although taking place in the summer rather than the winter. Aestivation is characterized by inactivity and ...

, when the animal did not feed. Aestivation also complies with the supposed habitat of the animals, which would have been desert-like, including hot dry seasons when food was scarce.

A comprehensive analysis conducted in 1980 by Hopson questioned Thulborn's ideas. Hopson showed that the wear facet patterns on the teeth in fact indicate vertical and lateral rather than back and forth jaw movements. Furthermore, Hopson demonstrated variability in the degree of tooth wear, indicating continuous tooth replacement. He did acknowledge that X-ray images of the most complete specimen showed that this individual indeed lacked unerupted replacement teeth. According to Hopson, this indicated that only juveniles continuously replaced their teeth, and that this process ceased when reaching adulthood. Thulborn's aestivation hypothesis was rejected by Hopson due to lack of evidence.

In 2006, Butler and colleagues conducted computer tomography scans of the juvenile skull SAM-PK-K10487. To the surprise of these researchers, replacement teeth yet to erupt were present even in this early ontogenetic stage. Despite these findings, the authors argued that tooth replacement must have occurred since the juvenile displayed the same tooth morphology as adult individuals – this morphology would have changed if the tooth simply grew continuously. In conclusion, Butler and colleagues suggested that tooth replacement in ''Heterodontosaurus'' must have been more sporadic than in related dinosaurs. Unerupted replacement teeth in ''Heterodontosaurus'' were not discovered until 2011, when Norman and colleagues described the upper jaw of specimen SAM-PK-K1334. Another juvenile skull (AMNH 24000) described by Sereno in 2012 also yielded unerupted replacement teeth. As shown by these discoveries, tooth replacement in ''Heterodontosaurus'' was episodical and not continuous as in other heterodontosaurids. The unerupted teeth are triangular in lateral view, which is the typical tooth morphology in basal ornithischians. The characteristic chisel-like shape of the fully erupted teeth therefore resulted from tooth-to-tooth contact between the dentition of the upper and lower jaws.

Locomotion, metabolism and breathing

Although most researchers now consider ''Heterodontosaurus'' abipedal

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning 'two feet' (from Latin ''bis'' 'double' ...

runner, some earlier studies proposed a partial or fully quadrupedal

Quadrupedalism is a form of locomotion where four limbs are used to bear weight and move around. An animal or machine that usually maintains a four-legged posture and moves using all four limbs is said to be a quadruped (from Latin ''quattuor' ...

locomotion. In 1980, Santa Luca described several features of the forelimb that are also present in recent quadrupedal animals and imply a strong arm musculature: These include a large olecranon

The olecranon (, ), is a large, thick, curved bony eminence of the ulna, a long bone in the forearm that projects behind the elbow. It forms the most pointed portion of the elbow and is opposite to the cubital fossa or elbow pit. The olecranon ...

(a bony eminence forming the uppermost part of the ulna), enlarging the lever arm

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of ...

of the forearm. The medial epicondyle of the humerus

The medial epicondyle of the humerus is an epicondyle of the humerus bone of the upper arm in humans. It is larger and more prominent than the lateral epicondyle and is directed slightly more posteriorly in the anatomical position. In birds, whe ...

was enlarged, providing attachment sites for strong flexor

A flexor is a muscle that flexes a joint. In anatomy, flexion (from the Latin verb ''flectere'', to bend) is a joint movement that decreases the angle between the bones that converge at the joint. For example, one’s elbow joint flexes when one ...

muscles of the forearm. Furthermore, projections on the claws might have increased the forward thrust of the hand during walking. According to Santa Luca, ''Heterodontosaurus'' was quadrupedal when moving slowly but was able to switch to a much faster, bipedal run. The palaeontologists Teresa Maryańska

Teresa Maryańska (1937 – 3 October 2019) was a Polish paleontologist who specialized in Mongolian dinosaurs, particularly pachycephalosaurians and ankylosaurians. Peter Dodson (1998 p. 9) states that in 1974 Maryanska together with Hals ...

and Halszka Osmólska

Halszka Osmólska (September 15, 1930 – March 31, 2008) was a Polish paleontologist who had specialized in Mongolian dinosaurs.

Biography

She was born in 1930 in Poznań. In 1949, she began to study biology at Faculty of Biology and Earth Scie ...

supported Santa Luca's hypothesis in 1985; furthermore, they noted that the dorsal spine was strongly flexed downwards in the most completely known specimen. In 1987, Gregory S. Paul suggested that ''Heterodontosaurus'' might have been obligatorily quadrupedal, and that these animals would have gallop

The canter and gallop are variations on the fastest gait that can be performed by a horse or other equine. The canter is a controlled three-beat gait, while the gallop is a faster, four-beat variation of the same gait. It is a natural gait pos ...

ed for fast locomotion. David Weishampel

Professor David Bruce Weishampel (born November 16, 1952) is an American palaeontologist in the Center for Functional Anatomy and Evolution at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Weishampel received his Ph.D. in Geology from the Univers ...

and Lawrence Witmer

Lawrence M. Witmer (born October 10, 1959, at Rochester, New York) is an American paleontologist and paleobiologist. He is a Professor of Anatomy and a Chang Ying-Chien Professor of Paleontology at the Department of Biomedical Sciences at the Her ...

in 1990 as well as Norman and colleagues in 2004 argued in favour of exclusively bipedal locomotion, based on the morphology of the claws and shoulder girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists of ...

. The anatomical evidence suggested by Santa Luca was identified as adaptations for foraging; the robust and strong arms might have been used for digging up roots and breaking open insect nests.

Most studies consider dinosaurs as endothermic

In thermochemistry, an endothermic process () is any thermodynamic process with an increase in the enthalpy (or internal energy ) of the system.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).''Principle of Modern Chemistry'', Brooks Cole. p. ...

(warm-blooded) animals, with an elevated metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

comparable to that of today's mammals and birds. In a 2009 study, Herman Pontzer and colleagues calculated the aerobic endurance

Aerobic exercise (also known as endurance activities, cardio or cardio-respiratory exercise) is physical exercise of low to high exercise intensity, intensity that depends primarily on the aerobic Adenosine triphosphate, energy-generating process ...

of various dinosaurs. Even at moderate running speeds, ''Heterodontosaurus'' would have exceeded the maximum aerobic capabilities possible for an ectotherm

An ectotherm (from the Greek () "outside" and () "heat") is an organism in which internal physiological sources of heat are of relatively small or of quite negligible importance in controlling body temperature.Davenport, John. Animal Life a ...

(cold-blooded) animal, indicating endothermy in this genus.

Dinosaurs likely possessed an air sac

Air sacs are spaces within an organism where there is the constant presence of air. Among modern animals, birds possess the most air sacs (9–11), with their extinct dinosaurian relatives showing a great increase in the pneumatization (presence ...

system as found in modern birds, which ventilated an immobile lung. Air flow was generated by contraction of the chest, which was allowed by mobile sternal ribs and the presence of gastralia. Extensions of the air sacs also invaded bones, forming excavations and chambers, a condition known as postcranial skeletal pneumaticity. Ornithischians, with the exception of ''Heterodontosaurus'', lacked mobile sternal ribs and gastralia, and all ornithischians (including ''Heterodontosaurus'') lacked postcranial skeletal pneumaticity. Instead, ornithischians had a prominent anterior extension of the pubis, the anterior pubic process (APP), which was absent in other dinosaurs. Based on synchrotron data of a well-preserved ''Heterodontosaurus'' specimen (AM 4766), Viktor Radermacher and colleagues, in 2021, argued that the breathing system of ornithischians drastically differed from that of other dinosaurs, and that ''Heterodontosaurus'' represents an intermediate stage. According to these authors, ornithischians lost the ability to contract the chest for breathing, and instead relied on a muscle that ventilated the lung directly, which they termed the ''puberoperitoneal muscle''. The APP of the pelvis would have provided the attachment site for this muscle. ''Heterodontosaurus'' had an incipient APP, and its gastralia were reduced compared to non-ornithischian dinosaurs, suggesting that the pelvis was already involved in breathing while chest contraction became less important.

Growth and proposed sexual dimorphism

The

The ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...

, or the development of the individual from juvenile to adult, is poorly known for ''Heterodontosaurus'', as juvenile specimens are scarce. As shown by the juvenile skull SAM-PK-K10487, the eye sockets became proportionally smaller as the animal grew, and the snout became longer and contained additional teeth. Similar changes have been reported for several other dinosaurs. The morphology of the teeth, however, did not change with age, indicating that the diet of juveniles was the same as that of adults. The length of the juvenile skull was suggested to be . Assuming similar body proportions as adult individuals, the body length of this juvenile would have been . Indeed, the individual probably would have been smaller, since juvenile animals in general show proportionally larger heads.

In 1974, Thulborn suggested that the large tusks of heterodontosaurids represented a secondary sex characteristic

Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during puberty in humans, and at sexual maturity in other animals. These characteristics are particularly evident in the sexually dimorphic phenotypic traits that distinguish the sexes of a sp ...