Harry C. Byrd on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Harry Clifton "Curley" Byrd (February 12, 1889 – October 2, 1970) was an American university administrator, educator, athlete, coach, and politician. Byrd began a long association with the

''Somerset County, Maryland: A Brief History''

pp. 111–a112, The History Press, 2007, . He attended

In 1905, Byrd graduated from Crisfield High School and enrolled at the

In 1905, Byrd graduated from Crisfield High School and enrolled at the

''Football in Baltimore: History and Memorabilia''

p. 41, JHU Press, 2000, . According to ''The Georgetown Hoyas: A Story of A Rambunctious Football Team'', Dorais's "end-over-end 'discus' throw was an exact copy" of Byrd's passing technique, and the Irish "got the headlines because they had a press agent and Georgetown didn't." Byrd also played for Maryland-based semi-professional baseball teams while pursuing his graduate studies. In 1910, the

In 1911, injuries claimed enough Maryland Agricultural football players that the team could no longer field a practice squad to scrimmage against. The college turned to Byrd, who was serving as coach at

In 1911, injuries claimed enough Maryland Agricultural football players that the team could no longer field a practice squad to scrimmage against. The college turned to Byrd, who was serving as coach at

Tales from the Maryland Terrapins

', pp. 18–20, Sports Publishing LLC, 2003, . In 1913, the Maryland Agricultural College hired Byrd as an instructor in English and history, and he was named the head coach of the track and

, College Football Data Warehouse, retrieved July 4, 2010.

Byrd was appointed to the post of assistant university president in 1918. He became a proponent of unification of the Maryland Agricultural College and the

Byrd was appointed to the post of assistant university president in 1918. He became a proponent of unification of the Maryland Agricultural College and the

''Richard Hofstadter: an Intellectual Biography''

p. 37, University of Chicago Press, 2006, . From 1945 to 1948, the university budget increased from $4.8 million to $9.8 million. Between 1935 and 1954, student enrollment grew from 3,400 to 16,000. Over that same time period, the value of the campus rose from $5 million to $65 million. Byrd, however stood fast on faculty salaries. He reportedly said, "

''Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634–1980''

p. 565, JHU Press, 1996, . For years, Byrd refused to release the university's financial records to state legislators, and how exactly he secured funding for many of his projects was largely a mystery. According to booster Jack Heise, Byrd financed a new basketball arena through the out-of-state tuition, paid by the federal government, for Maryland high school graduates who attended the university on the G.I. Bill. The

''Maryland Politics and Political Communication, 1950–2005''

pp. 150–151, Lexington Books, 2006, . In 1945, Byrd hired 32-year-old

''I Remember Paul "Bear" Bryant: Personal Memoires of College Football's Most Legendary Coach, as Told by the People Who Knew Him Best''

pp. 100-101, Cumberland House Publishing, . Bryant resigned as head coach an hour later, which caused an uproar among students until he interceded to restore order. Two years later, Byrd hired Jim Tatum as football coach. The year prior at

The Forgotten Man of Oklahoma Football: Jim Tatum; "Jim Tatum was a con-man, a dictator, a tyrant and one hell of a football coach." – Buddy Burris, All-American 1946, 1947 and 1948

, ''Sooner Magazine'', University of Oklahoma Foundation, Inc., Spring 2008. which resulted in university president

''An Autumn Remembered: Bud Wilkinson's legendary '56 Sooners''

p. 38–40, University of Oklahoma Press, 2006, . Tatum told Cross to refute Tatum's role in the matter, and threatened to reveal the Oklahoma team had been paid $6,000 after the 1947

''Time'', January 23, 1950. Schools found to be in violation could be expelled from the NCAA. In 1950, seven schools, called the "Sinful Seven"—

''College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy''

p. 214, JHU Press, 2002, . University of Virginia president Colgate Darden called the code hypocritical, and The Citadel's leadership refused to "lie to stay in the association" and requested termination of its NCAA membership. At the convention to decide Virginia's fate, Byrd said, "Does

''Maryland Basketball: Tales from Cole Field House''

pp. 10–12, JHU Press, 2002, . Among the campus expansions, Byrd was responsible for the construction of Byrd Stadium in 1950 and

''Time'', August 3, 1959. Byrd also built the University of Maryland Golf Course in 1959. Byrd resigned from the post in 1953 and his tenure ended effectively on December 31.

''Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940–1980''

UNC Press, 2003, . Elsewhere in the state, however, middle-class white voters did not support Byrd. Byrd lost by 54.46% to 45.54%. He went on to make unsuccessful bids for the Democratic nominations to the

174–175

University of Georgia Press, 2009, . Following the example of other oyster-producing states, Byrd authorized fossil shell mining to produce culch, crushed shells used to form

Obituary

''The Daily Times'' and his

, University of Maryland, retrieved June 12, 2009.

Sterling Byrd collection

at the

University of Maryland

The University of Maryland, College Park (University of Maryland, UMD, or simply Maryland) is a public land-grant research university in College Park, Maryland. Founded in 1856, UMD is the flagship institution of the University System of M ...

as an undergraduate in 1905, and eventually rose to the position of university president

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth and former Commonwealth n ...

from 1936 to 1954.

In the interim, he had also served as the university's athletic director

An athletic director (commonly "athletics director" or "AD") is an administrator at many American clubs or institutions, such as colleges and universities, as well as in larger high schools and middle schools, who oversees the work of coaches and ...

and head coach for the football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

and baseball teams. Byrd amassed a 119–82–15 record in football from 1911 to 1934 and 88–73–4 record in baseball from 1913 to 1923. In graduate school at Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

, he became one of football's early users of the newly legalized forward pass

In several forms of football, a forward pass is the throwing of the ball in the direction in which the offensive team is trying to move, towards the defensive team's goal line. The forward pass is one of the main distinguishers between gridiron ...

, and he had a brief baseball career including one season as pitcher

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throws ("pitches") the baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of retiring a batter, who attempts to either make contact with the pitched ball or draw ...

for the San Francisco Seals.

Byrd resigned as university president in order to enter politics in 1954. He ran an unsuccessful campaign as the Democratic candidate for Maryland governor against Theodore McKeldin. Byrd later received appointments to state offices with responsibilities in the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

and Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

. In the 1960s, he made unsuccessful bids for seats in each chamber of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

. Byrd was a proponent of a " separate but equal" status of racial segregation in his roles as both university administrator and political candidate.

In 2015, the Student Government Association agreed to a resolution in support of changing the name of Byrd Stadium because Byrd was, in their words, "a racist and a segregationist" who "barred blacks from participating in sports and enrolling into the University until 1951". On September 28, 2015, University of Maryland President Wallace Loh appointed a task force to develop viewpoints and options. The University President then made a recommendation to the University System of Maryland Board of Regents — the governing body of Maryland state universities — to change the name to "Maryland Stadium". The ultimate decision on any name change rests with the Board of Regents. On December 11, 2015, the Board of Regents voted 12–5 to remove the "Byrd" from the stadium's name, renaming it Maryland Stadium for the time being.

Early life

Harry Clifton Byrd was born on February 12, 1889, in Crisfield, Maryland. He was one of six children of oysterman and county commissioner William Franklin Byrd and his wife Sallie May Byrd. In his youth, Byrd worked in theChesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the ...

fishing industry, where he saved most of his money to finance his college education.Jason Rhodes''Somerset County, Maryland: A Brief History''

pp. 111–a112, The History Press, 2007, . He attended

Crisfield High School

Crisfield Academy and High School (commonly abbreviated to CAHS), also once known as simply Crisfield High School (CHS), is a public high school in the city of Crisfield in Somerset County, Maryland, United States. It is located in the Somers ...

, where he excelled on the baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

diamond, and was also known as his hometown's first recreational jogger

Jogging is a form of trotting or running at a slow or leisurely pace. The main intention is to increase physical fitness with less stress on the body than from faster running but more than walking, or to maintain a steady speed for longer periods ...

.

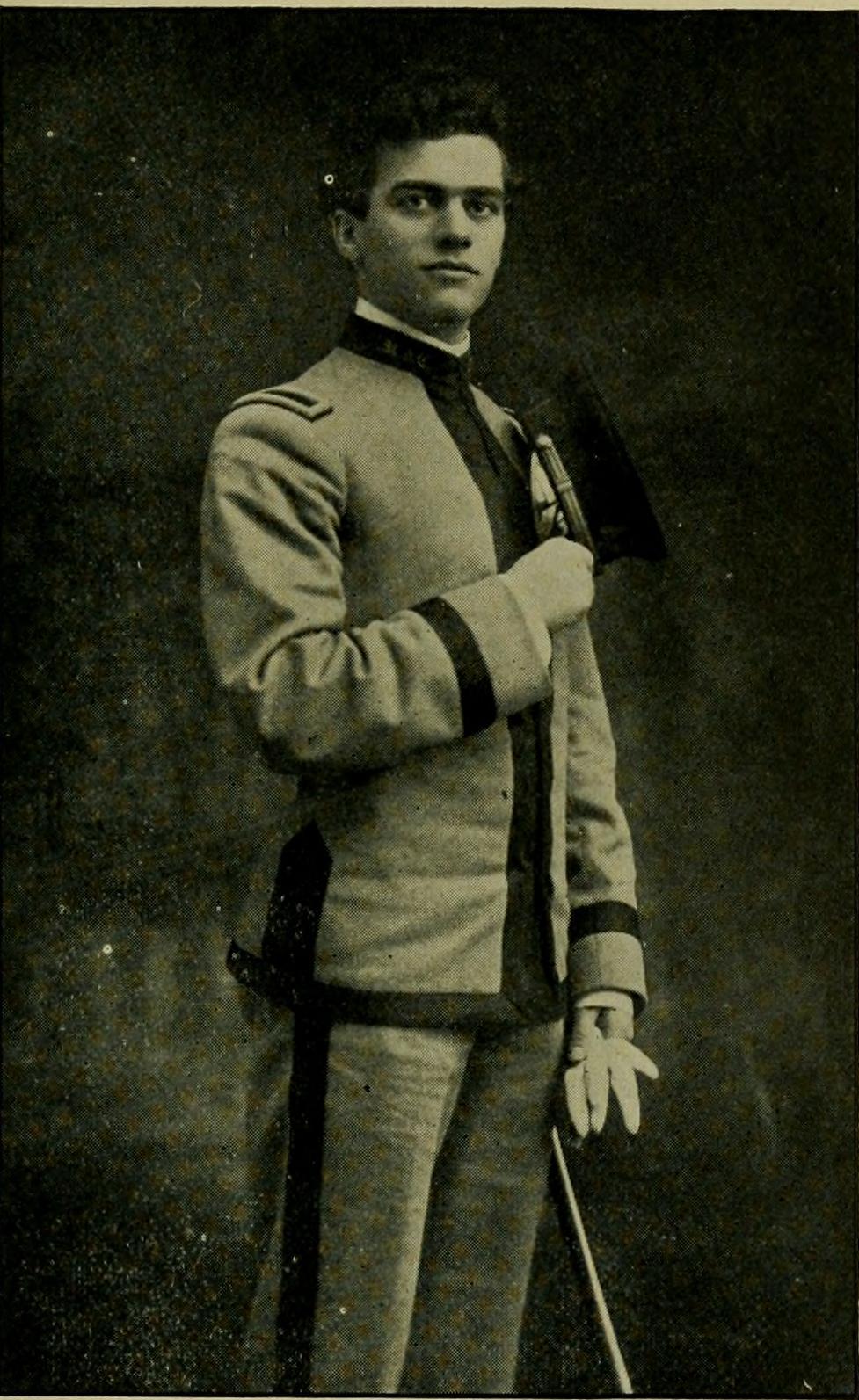

A later source described how he appeared in 1905

He was tall, and as the saying goes, built like a whip. He had a startlingly handsome face, with big, flashing eyes, a splotch of florid red on each cheek, and a mane of black curly hair ... He looked like Rupert of Hentzau, and had all of that worthy's cold, sinister resolution about everything that he did.

College career

In 1905, Byrd graduated from Crisfield High School and enrolled at the

In 1905, Byrd graduated from Crisfield High School and enrolled at the Maryland Agricultural College

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to it ...

, which is now known as the University of Maryland. Byrd was a star college athlete and participated in varsity football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

, baseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

, and track. He served as the football team captain in 1907, as the pitcher

In baseball, the pitcher is the player who throws ("pitches") the baseball from the pitcher's mound toward the catcher to begin each play, with the goal of retiring a batter, who attempts to either make contact with the pitched ball or draw ...

on the baseball team, and set a school record 10.0-second 100-yard dash

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1 ...

in track. Before leaving Crisfield, Byrd's father warned him not to "try to play that thing called football."Morris Allison Bealle, ''Kings of American Football: The University of Maryland, 1890–1952'', p. 50, Columbia Publishing Co., 1952. He ignored the advice and reported for football practice where head coach Fred K. Nielsen told the undersized Byrd to "play with the kids" and that "football's a man's game." He was allowed, however, to fill in as an end on the scout team due to a shortage of players. After sitting out the first three games, Nielsen sent Byrd in as a substitute against Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

, and his play was impressive enough to earn a position on the first team. After the elder Byrd read of his son's newfound stardom in the newspaper, he wrote, "Since you're going to play football, I'm glad to see you're doing it well." During the summers and on weekends, Byrd supplemented his income by continuing work as a fisherman. He graduated second in his class with a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University of ...

degree in civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewage ...

in 1908.Harry Clifton Byrd papersUniversity of Maryland Libraries

The University of Maryland Libraries is the largest university library in the Washington, D.C. - Baltimore area. The university's library system includes eight libraries: six are located on the College Park campus, while the Severn Library, an of ...

, retrieved July 4, 2010.

After graduation from Maryland, Byrd spent the next three years doing graduate work in law and journalism at George Washington University

, mottoeng = "God is Our Trust"

, established =

, type = Private federally chartered research university

, academic_affiliations =

, endowment = $2.8 billion (2022)

, preside ...

, Georgetown University

Georgetown University is a private university, private research university in the Georgetown (Washington, D.C.), Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C. Founded by Bishop John Carroll (archbishop of Baltimore), John Carroll in 1789 as Georg ...

, and Western Maryland College (now known as McDaniel College). In a time before eligibility limitations, he played football at George Washington and Georgetown and ran track at Western Maryland. At Georgetown in 1909, he was called the first quarterback

The quarterback (commonly abbreviated "QB"), colloquially known as the "signal caller", is a position in gridiron football. Quarterbacks are members of the offensive platoon and mostly line up directly behind the offensive line. In modern Ame ...

in the East to master the forward pass

In several forms of football, a forward pass is the throwing of the ball in the direction in which the offensive team is trying to move, towards the defensive team's goal line. The forward pass is one of the main distinguishers between gridiron ...

, several years before Gus Dorais of Notre Dame did so in 1913.Ted Patterson and Edwin H. Remsberg''Football in Baltimore: History and Memorabilia''

p. 41, JHU Press, 2000, . According to ''The Georgetown Hoyas: A Story of A Rambunctious Football Team'', Dorais's "end-over-end 'discus' throw was an exact copy" of Byrd's passing technique, and the Irish "got the headlines because they had a press agent and Georgetown didn't." Byrd also played for Maryland-based semi-professional baseball teams while pursuing his graduate studies. In 1910, the

Chicago White Sox

The Chicago White Sox are an American professional baseball team based in Chicago. The White Sox compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) Central division. The team is owned by Jerry Reinsdorf, and p ...

signed Byrd, but he was soon traded to the San Francisco Seals, a semi-professional Pacific Coast League

The Pacific Coast League (PCL) is a Minor League Baseball league that operates in the Western United States. Along with the International League, it is one of two leagues playing at the Triple-A (baseball), Triple-A level, which is one grade bel ...

baseball team for whom he pitched in 1912. He returned to Maryland later that year, and in 1913, married Katherine Dunlop Turnbull. Before they divorced twenty years later, the couple had three sons and a daughter: Harry, Sterling, William, and Evelyn.

Coaching career

In 1911, injuries claimed enough Maryland Agricultural football players that the team could no longer field a practice squad to scrimmage against. The college turned to Byrd, who was serving as coach at

In 1911, injuries claimed enough Maryland Agricultural football players that the team could no longer field a practice squad to scrimmage against. The college turned to Byrd, who was serving as coach at Western High School Western High School may refer:

Schools in the United States

*Western High School (Anaheim, California) – Anaheim, California

* Western High School (Illinois) – Barry, Illinois

* Western High School (Florida) – Davie, Florida

* Western High S ...

in Georgetown, and he was willing to help his alma mater with scrimmages. Byrd later replaced head coach Charley Donnelly, who resigned mid-season after accumulating a 2–4–2 record. Byrd led the Aggies to wins in both of their final games of the season, against Western Maryland, 6–0, and Gallaudet

Gallaudet University ( ) is a private university, private University charter#Federal, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C. for the education of the Hearing loss, deaf and hard of hearing. It was founded in 1864 as a gramma ...

, 6–2.David Ungrady, Tales from the Maryland Terrapins

', pp. 18–20, Sports Publishing LLC, 2003, . In 1913, the Maryland Agricultural College hired Byrd as an instructor in English and history, and he was named the head coach of the track and

baseball team

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding te ...

s, the latter of which he coached through 1923. According to author David Ungrady in ''Tales from the Maryland Terrapins'', the university initially offered Byrd $300 to coach football, but he demanded $1,200. The two parties came to agree upon that salary for all of his coaching and teaching duties which spanned nine months of the year. Byrd also worked as a sportswriter for '' The Washington Star'', a job he held until 1932.

As football coach, he developed a unique offensive scheme called the "Byrd system", which combined elements of the single-wing and double-wing formation

In American and Canadian football, a single-wing formation was a precursor to the modern spread or shotgun formation. The term usually connotes formations in which the snap is tossed rather than handed—formations with one wingback and a hand ...

s. One of Byrd's track and football players, Geary Eppley

Geary Francis "Swede" Eppley ( December 30, 1895 – June 10, 1978) was an American university administrator, professor, agronomist, military officer, athlete, and track and field coach. He served as the University of Maryland athletic director f ...

, said, "He never yelled in practice or at a game ... He pointed out mistakes and explained what you did wrong. He took a calm approach. The strongest thing he'd say was 'for cripes sake.'"

In 1915, his duties were expanded to include those of athletic director

An athletic director (commonly "athletics director" or "AD") is an administrator at many American clubs or institutions, such as colleges and universities, as well as in larger high schools and middle schools, who oversees the work of coaches and ...

. That same year, he requested funds for the construction of the campus's first dedicated football stadium, which was named in his honor. During his tenure as head football coach from 1911 to 1934, he compiled a 119–82–15 record.All-Time Coach Records by Year: Curley Byrd, College Football Data Warehouse, retrieved July 4, 2010.

Administrative career

Byrd was appointed to the post of assistant university president in 1918. He became a proponent of unification of the Maryland Agricultural College and the

Byrd was appointed to the post of assistant university president in 1918. He became a proponent of unification of the Maryland Agricultural College and the Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

professional schools into a single public University of Maryland, and he was instrumental in what became the Consolidation Act of 1920. Byrd named the student newspaper '' The Diamondback'' in 1921, and in 1933, he was the lead advocate for the adoption of the diamondback terrapin as the university's official nickname and mascot

A mascot is any human, animal, or object thought to bring luck, or anything used to represent a group with a common public identity, such as a school, professional sports team, society, military unit, or brand name. Mascots are also used as fi ...

.

In 1932, Byrd was promoted to vice president of the university. In July 1935, he was named the acting president of the university, and was officially appointed to the presidency in February 1936. During his tenure, the budget, facilities, faculty, and enrollment increased significantly. The school budget was increased and the campus expanded largely due to Byrd's deft political maneuvering in Annapolis

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

. The school also saw a large growth in enrollment, due in part to returning veterans making use of the G.I. Bill

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in 1956, bu ...

after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.David Scott Brown''Richard Hofstadter: an Intellectual Biography''

p. 37, University of Chicago Press, 2006, . From 1945 to 1948, the university budget increased from $4.8 million to $9.8 million. Between 1935 and 1954, student enrollment grew from 3,400 to 16,000. Over that same time period, the value of the campus rose from $5 million to $65 million. Byrd, however stood fast on faculty salaries. He reportedly said, "

Ph.D.

A Doctor of Philosophy (PhD, Ph.D., or DPhil; Latin: or ') is the most common degree at the highest academic level awarded following a course of study. PhDs are awarded for programs across the whole breadth of academic fields. Because it is a ...

s are a dime a dozen."Roger J. Brugger''Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634–1980''

p. 565, JHU Press, 1996, . For years, Byrd refused to release the university's financial records to state legislators, and how exactly he secured funding for many of his projects was largely a mystery. According to booster Jack Heise, Byrd financed a new basketball arena through the out-of-state tuition, paid by the federal government, for Maryland high school graduates who attended the university on the G.I. Bill. The

General Accounting Office

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) is a legislative branch government agency that provides auditing, evaluative, and investigative services for the United States Congress. It is the supreme audit institution of the federal govern ...

calculated that the extra fees totaled more than $2 million, but determined that they were within the bounds of legality.McMullen, p. 12.

Byrd was a staunch supporter of a " separate but equal" state university system. The Princess Anne campus provided agricultural education and Morgan State College provided liberal arts education for the state's black students, while the University of Maryland remained open only to white students. In 1951, Governor Theodore McKeldin criticized the University of Maryland as an example of wasteful state spending, and was especially critical of expansions to the Princess Anne campus, which was geographically disconnected from the state's black population and not attracting many students to study agriculture. Contractors had begun projects at the college before approval from the public works board, which was described as a usual practice under Byrd. Byrd acceded to McKeldin and secured approval from the board for both the Princess Anne expansions as well as a sizable increase to the university budget.Theodore F. Scheckels''Maryland Politics and Political Communication, 1950–2005''

pp. 150–151, Lexington Books, 2006, . In 1945, Byrd hired 32-year-old

Paul "Bear" Bryant

Paul William "Bear" Bryant (September 11, 1913 – January 26, 1983) was an American college football player and coach. He is considered by many to be one of the greatest college football coaches of all time, and best known as the head coach of t ...

to his first head coaching post. Bryant led the Terrapins to a 6–2–1 record, but the two personalities clashed. The tensions came to a head when Byrd reinstated a player Bryant had suspended for violating team rules.Al Browning''I Remember Paul "Bear" Bryant: Personal Memoires of College Football's Most Legendary Coach, as Told by the People Who Knew Him Best''

pp. 100-101, Cumberland House Publishing, . Bryant resigned as head coach an hour later, which caused an uproar among students until he interceded to restore order. Two years later, Byrd hired Jim Tatum as football coach. The year prior at

Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

, Tatum fielded a winning team, but the athletic department ran up a huge deficit and some players were paid in violation of conference

A conference is a meeting of two or more experts to discuss and exchange opinions or new information about a particular topic.

Conferences can be used as a form of group decision-making, although discussion, not always decisions, are the main p ...

rules,Gary KingThe Forgotten Man of Oklahoma Football: Jim Tatum; "Jim Tatum was a con-man, a dictator, a tyrant and one hell of a football coach." – Buddy Burris, All-American 1946, 1947 and 1948

, ''Sooner Magazine'', University of Oklahoma Foundation, Inc., Spring 2008. which resulted in university president

George Cross

The George Cross (GC) is the highest award bestowed by the British government for non-operational gallantry or gallantry not in the presence of an enemy. In the British honours system, the George Cross, since its introduction in 1940, has been ...

firing athletic director Jap Haskell. The media blamed Tatum for his termination.Gary King''An Autumn Remembered: Bud Wilkinson's legendary '56 Sooners''

p. 38–40, University of Oklahoma Press, 2006, . Tatum told Cross to refute Tatum's role in the matter, and threatened to reveal the Oklahoma team had been paid $6,000 after the 1947

Gator Bowl

The Gator Bowl is an annual college football bowl game held in Jacksonville, Florida, operated by Gator Bowl Sports. It has been held continuously since 1946, making it the sixth oldest college bowl, as well as the first one ever televised natio ...

. Cross asked Byrd to persuade Tatum not to go public, and according to author Gary King in ''An Autumn Remembered'', Byrd replied, "Persuade, hell! I'll tell him to keep his damn mouth shut!" Tatum remained as coach at Maryland from 1947 to 1955, and amassed a 73–15–4 record.

In 1948, the National Collegiate Athletic Association

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) is a nonprofit organization that regulates student athletics among about 1,100 schools in the United States, Canada, and Puerto Rico. It also organizes the athletic programs of colleges an ...

passed a set of regulations called the Purity Code, later renamed the Sanity Code, which permitted student-athletes free tuition and meals, but required that part-time jobs be legitimate and their pay commensurate with the work.Sport: What Price Football?''Time'', January 23, 1950. Schools found to be in violation could be expelled from the NCAA. In 1950, seven schools, called the "Sinful Seven"—

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, Maryland, VMI, Virginia Tech

Virginia Tech (formally the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University and informally VT, or VPI) is a Public university, public Land-grant college, land-grant research university with its main campus in Blacksburg, Virginia. It also ...

, The Citadel, Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Founded in 1863, the university has more than 9,300 full-time undergraduates and nearly 5,000 graduate students. Although Boston College is classifie ...

, and Villanova—admitted they were in violation of the code. ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine asserted violators were far more widespread than those seven that had confessed. Maryland was the only Sinful Seven school that was also a major football power with eighty scholarship players, and Byrd led them in their stand against the Sanity Code.John Sayle Watterson''College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy''

p. 214, JHU Press, 2002, . University of Virginia president Colgate Darden called the code hypocritical, and The Citadel's leadership refused to "lie to stay in the association" and requested termination of its NCAA membership. At the convention to decide Virginia's fate, Byrd said, "Does

Ohio State

The Ohio State University, commonly called Ohio State or OSU, is a public land-grant research university in Columbus, Ohio. A member of the University System of Ohio, it has been ranked by major institutional rankings among the best public ...

want to vote for expulsion of Virginia, when Ohio State has facilities to take care of four or five as many athletes as Virginia?" The ensuing vote fell 25 short of the needed two-thirds majority to expel the Sinful Seven.

In 1951, the football team's 10–0 season culminated in a 28–13 victory over first-ranked Tennessee in the 1952 Sugar Bowl

The 1952 Sugar Bowl was a postseason American college football bowl game between the Tennessee Volunteers and the Maryland Terrapins at the Tulane Stadium in New Orleans, Louisiana, on January 1, 1952. It was the eighteenth edition of the annual S ...

. Maryland's participation, however, was in violation of a Southern Conference resolution passed mid-season that banned participation in postseason bowl game

In North America, a bowl game is one of a number of post-season college football games that are primarily played by teams belonging to the NCAA's Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS). For most of its history, the Division I Bowl Subdivis ...

s. Byrd had Maryland accept the bowl invitation, despite Tatum's objections. The coach thought the threatened sanctions, which prevented Maryland from playing any Southern Conference games the following season, would severely disadvantage his team. In 1952, Maryland and Clemson, which had also violated the bowl game ban, were sanctioned, and the incident hastened the break-up of the Southern Conference and formation of the Atlantic Coast Conference

The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) is a collegiate athletic conference located in the eastern United States. Headquartered in Greensboro, North Carolina, the ACC's fifteen member universities compete in the National Collegiate Athletic Associa ...

, of which both schools were founding members.

Opponents in ''The Baltimore Sun

''The Baltimore Sun'' is the largest general-circulation daily newspaper based in the U.S. state of Maryland and provides coverage of local and regional news, events, issues, people, and industries.

Founded in 1837, it is currently owned by Tr ...

'' alleged that Byrd emphasized athletics over academics and belittled him as the only college football coach to rise to the position of university president.Paul McMullen''Maryland Basketball: Tales from Cole Field House''

pp. 10–12, JHU Press, 2002, . Among the campus expansions, Byrd was responsible for the construction of Byrd Stadium in 1950 and

Cole Field House

The Jones-Hill House is an indoor collegiate sports training complex located on of land on the campus of the University of Maryland in College Park, a suburb north of Washington, D.C. Jones-Hill House is situated in the center of the campus, ...

in 1955, which at the time was the largest basketball arena in the Southern Conference. Critics alleged that both facilities were constructed at the expense of campus libraries.The Coach''Time'', August 3, 1959. Byrd also built the University of Maryland Golf Course in 1959. Byrd resigned from the post in 1953 and his tenure ended effectively on December 31.

Political career

Byrd resigned from the presidency in January 1954 to embark upon an unsuccessful campaign forGovernor of Maryland

The Governor of the State of Maryland is the head of government of Maryland, and is the commander-in-chief of the state's National Guard units. The Governor is the highest-ranking official in the state and has a broad range of appointive powers ...

. He narrowly beat perennial candidate George P. Mahoney

George Perry Mahoney (December 16, 1901 – March 18, 1989) was an Irish American Catholic building contractor and Democratic Party politician from the State of Maryland. A perennial candidate, Mahoney is perhaps most famous as the Democratic no ...

in the Democratic primary by 50.64% to 49.37% and faced Republican incumbent McKeldin in the general election. Byrd campaigned on his stance of separate but equal. McKeldin won comfortable majorities in Baltimore's black, Jewish, and upper-middle class white districts, while Byrd took all of the blue-collar white South and East Baltimore neighborhoods, including McKeldin's boyhood home along Eutaw Street

Eutaw Street is a major street in Baltimore, Maryland, mostly within the downtown area. Outside of downtown, it is mostly known as Eutaw Place.

The south end of Eutaw Street is at Oriole Park at Camden Yards. After this point, the street continue ...

.Kenneth D. Durr''Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940–1980''

UNC Press, 2003, . Elsewhere in the state, however, middle-class white voters did not support Byrd. Byrd lost by 54.46% to 45.54%. He went on to make unsuccessful bids for the Democratic nominations to the

U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

in 1964 and the U.S. Congress in 1966.

Despite his lack of success in campaigning, Byrd did receive several gubernatorial appointments: Chairman of the Maryland Tidewater Fisheries Commission, Maryland Commissioner to the Potomac River Fisheries Commission, and Chairman of the Commission on Chesapeake Bay Affairs. In 1959, Governor J. Millard Tawes

John Millard Tawes (April 8, 1894June 25, 1979), was an American politician and a member of the Democratic Party who was the 54th Governor of Maryland from 1959 to 1967. He remains the only Marylander to be elected to the three positions of Stat ...

appointed Byrd as commissioner of tidewater fisheries. When a fisheries officer killed a Virginian waterman illegally dredging, Byrd disarmed the force. The action was credited with helping to end the long-standing Potomac River Oyster Wars

The Oyster Wars were a series of sometimes violent disputes between oyster pirates and authorities and legal watermen from Maryland and Virginia in the waters of the Chesapeake Bay and the Potomac River from 1865 until about 1959.

Background

In ...

.Christine Keiner, '' The Oyster Question: Scientists, Watermen, and the Maryland Chesapeake Bay since 1880'', pp174–175

University of Georgia Press, 2009, . Following the example of other oyster-producing states, Byrd authorized fossil shell mining to produce culch, crushed shells used to form

oyster bed

Oyster is the common name for a number of different families of salt-water bivalve molluscs that live in marine or brackish habitats. In some species, the valves are highly calcified, and many are somewhat irregular in shape. Many, but not al ...

s. Byrd ignored Tawes' warning to "stay away from private planting" by promoting the formation of leasing cooperatives, but his plan failed due to opposition in the Maryland General Assembly.

Business career

Byrd was also active in business and civic organizations. In 1951, he was involved in the merger that formed the Suburban Trust Company, which in 1960 was the largest bank in Maryland outside of Baltimore City. He later served as the company's vice president. Byrd also did business in real estate and construction. Byrd was active with service organizations. In 1962, he became a member of the Loyal Order of the Moose. Byrd organized the College ParkRotary Club

Rotary International is one of the largest service organizations in the world. Its stated mission is to "provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through hefellowship of business, profe ...

and served as its first president. Byrd was a member of the Defense Orientation Conference Association (DOCA), an organization which educates civilians on the Defense Department's programs and policies.

Death

Byrd died of a heart condition on October 2, 1970, at theUniversity of Maryland Hospital

The University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC) is a teaching hospital with 806 beds based in Baltimore, Maryland, that provides the full range of health care to people throughout Maryland and the Mid-Atlantic region. It gets more than 26,000 inpa ...

in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

. He is interred at Asbury United Methodist Church Cemetery in Crisfield, Maryland,''The Daily Times''

epitaph

An epitaph (; ) is a short text honoring a deceased person. Strictly speaking, it refers to text that is inscribed on a tombstone or plaque, but it may also be used in a figurative sense. Some epitaphs are specified by the person themselves be ...

reads: "Harry Clifton 'Curley' Byrd, Educator–Statesman–Conservationist, President Emeritus, Father and Builder of the Greater Consolidated University of Maryland, Founded 1920." Byrd was inducted into the University of Maryland Athletic Hall of Fame in 1982.University of Maryland Athletic Hall of Fame: All-Time Inductees, University of Maryland, retrieved June 12, 2009.

Head coaching record

Football

Baseball

References

External links

* *Sterling Byrd collection

at the

University of Maryland libraries

The University of Maryland Libraries is the largest university library in the Washington, D.C. - Baltimore area. The university's library system includes eight libraries: six are located on the College Park campus, while the Severn Library, an of ...

. Sterling Byrd was Curley Byrd's youngest child. Sterling Byrd's collection primarily contains documents of Curley Byrd's life and career.

{{DEFAULTSORT:Byrd, Curley

1889 births

1970 deaths

American civil engineers

American football quarterbacks

American male sprinters

Baseball pitchers

Georgetown Hoyas football players

George Washington Colonials football players

Maryland Terrapins athletic directors

Maryland Terrapins baseball coaches

Maryland Terrapins baseball players

Maryland Terrapins football coaches

Maryland Terrapins football players

Maryland Terrapins men's track and field athletes

Maryland Terrapins track and field coaches

San Francisco Seals (baseball) players

Presidents of the University of Maryland, College Park

University of Maryland, College Park faculty

High school football coaches in Washington, D.C.

Semi-professional baseball players

The Washington Star people

Maryland Democrats

McDaniel Green Terror men's track and field athletes

People from College Park, Maryland

People from Crisfield, Maryland

Players of American football from Maryland

Baseball players from Maryland

American white supremacists

Sportswriters from Maryland

State cabinet secretaries of Maryland