HMS Gloucester (1654) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The frigate ''Gloucester'' (spelt ''Glocester'' by contemporary sources) is a

During the 1650s, the fleets of the European powers generally fought in a

During the 1650s, the fleets of the European powers generally fought in a

''Gloucester'' (the name of the ship was spelt ''Glocester'' by contemporary sources) was a 'Speaker''-class third rate, and the first British naval vessel ship to be named after the English city of

''Gloucester'' (the name of the ship was spelt ''Glocester'' by contemporary sources) was a 'Speaker''-class third rate, and the first British naval vessel ship to be named after the English city of

''Gloucester'' was commissioned in 1654, with Benjamin Blake as captain. Under Blake, ''Gloucester'' was with Penn's fleet, an expedition that left England for the Caribbean on Christmas Day 1654. Known as the

''Gloucester'' was commissioned in 1654, with Benjamin Blake as captain. Under Blake, ''Gloucester'' was with Penn's fleet, an expedition that left England for the Caribbean on Christmas Day 1654. Known as the

Under John Holmes, ''Gloucester'' participated in the attack on the Smyrna fleet in the

Under John Holmes, ''Gloucester'' participated in the attack on the Smyrna fleet in the

The English and French fleets convened off

The English and French fleets convened off

''Gloucester'' was a valuable asset for the Royal Navy. From 16781680 she was comprehensively and expensively

''Gloucester'' was a valuable asset for the Royal Navy. From 16781680 she was comprehensively and expensively

In 2007, after a four-year-long search, the wreck of HMS ''Gloucester'' was found off the Norfolk coast by a group of experienced

In 2007, after a four-year-long search, the wreck of HMS ''Gloucester'' was found off the Norfolk coast by a group of experienced

The Gloucester Project

(the project by the

third rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy, a third rate was a ship of the line which from the 1720s mounted between 64 and 80 guns, typically built with two gun decks (thus the related term two-decker). Years of experience proved that the third ...

, commissioned into the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

as HMS ''Gloucester'' after the restoration of the English monarchy in 1660. The ship was ordered in December 1652, built at Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through ...

in East London, and launched in 1654. The warship was conveying James Stuart, Duke of York

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was depo ...

(the future King James II of England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

) to Scotland, when on 6 May 1682 she struck a sandbank off the Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

coast, and quickly sank. The Duke was among those saved, but as many as 250 people drowned, including members of the royal party; it is thought that James's intransigence delayed the evacuation of the passengers and crew.

The ''Gloucester'' participated in the British invasion of Jamaica (1655), and in the Battle of Lowestoft

The Battle of Lowestoft took place on during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. A fleet of more than a hundred ships of the United Provinces commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Jacob van Wassenaer, Lord Obdam attacked an English fleet of equal size comm ...

(3 June 1665). During 1666 she formed part of the fleet that attacked a Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

convoy

A convoy is a group of vehicles, typically motor vehicles or ships, traveling together for mutual support and protection. Often, a convoy is organized with armed defensive support and can help maintain cohesion within a unit. It may also be used ...

off Texel

Texel (; Texels dialect: ) is a municipality and an island with a population of 13,643 in North Holland, Netherlands. It is the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea. The island is situated north of Den ...

. She fought in the Four Days' Battle

The Four Days' Battle, also known as the Four Days' Fight in some English sources and as Vierdaagse Zeeslag in Dutch, was a naval battle of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Fought from 1 June to 4 June 1666 in the Julian or Old Style calendar that w ...

(14 June 1666) and also took part in the St. James's Day Battle (5 July 1666), the attack on the Smyrna fleet (March 1672), the Battle of Solebay

The naval Battle of Solebay took place on 28 May Old Style, 7 June New Style 1672 and was the first naval battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

The battle began as an attempted raid on Solebay port where an English fleet was anchored and large ...

(28 May 1672), and the Battles of Schooneveld (7 June and 14 June 1673). At the end of 1673, having participated in the Battle of Texel

The naval Battle of Texel or Battle of Kijkduin took place off the southern coast of island of Texel on 21 August 1673 (11 August O.S.) between the Dutch and the combined English and French fleets. It was the last major battle of the Third A ...

(11 August 1673), she was sent to the Mediterranean. ''Gloucester'' underwent a comprehensive refit at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

in 1678, when she was largely rebuilt, at great expense.

In 2007, after a four-year-long search, the wreck of ''Gloucester'' was found by an underwater diving team, who have since retrieved a variety of artefacts, including navigational aids, clothing, footwear, and other personal possessions. The wreck has been claimed by Claire Jowitt of the University of East Anglia

The University of East Anglia (UEA) is a public research university in Norwich, England. Established in 1963 on a campus west of the city centre, the university has four faculties and 26 schools of study. The annual income of the institution f ...

to be “the single most significant historic maritime discovery since the raising of the ''Mary Rose'' in 1982”. An exhibition relating to the wreck will be held at the Castle Museum in Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

during 2023.

Background

Following the end of theEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

in 1649, the new Parliamentary regime was threatened by foreign powers and Royalist supporters exiled from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, who targeted maritime trade. To counteract these threats, the government began building up the strength of the navy. It pressed ahead with restoring naval discipline and morale, and reorganising administration to meet wartime needs. It was placing orders for new ships as early as March 1649—by the close of 1651 the English navy had almost doubled in size since the end of the war, with 20 new warships built, and 25 ships acquired by being purchased or captured.

The Commonwealth navy supported the regime in several ways. It assisted in defeating Royalists who threatened English maritime trade, reducing the threat from Royalist-sponsored privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

s to commerce, and deterring them by the increased power and size of the fleet. It played a central role in the recapture of the Isles of Scilly, the Channel Islands

The Channel Islands ( nrf, Îles d'la Manche; french: îles Anglo-Normandes or ''îles de la Manche'') are an archipelago in the English Channel, off the French coast of Normandy. They include two Crown Dependencies: the Bailiwick of Jersey, ...

, and the Isle of Man

)

, anthem = "O Land of Our Birth"

, image = Isle of Man by Sentinel-2.jpg

, image_map = Europe-Isle_of_Man.svg

, mapsize =

, map_alt = Location of the Isle of Man in Europe

, map_caption = Location of the Isle of Man (green)

in Europe ...

, where important royalist privateering bases existed. It played an increasingly important part in consolidating the authority of the new regime in territories previously subject to Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

. It provided protection for supplies transported by sea during the 1650 invasion of Scotland, and a squadron

Squadron may refer to:

* Squadron (army), a military unit of cavalry, tanks, or equivalent subdivided into troops or tank companies

* Squadron (aviation), a military unit that consists of three or four flights with a total of 12 to 24 aircraft, ...

bombarded Leith

Leith (; gd, Lìte) is a port area in the north of the city of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith. In 2021, it was ranked by ''Time Out'' as one of the top five neighbourhoods to live in the world.

The earliest ...

(near Edinburgh) to cover the army's advance during the invasion. English naval power did much to persuade European governments of the need to recognize the Commonwealth, and had by 1653 become a major force in shaping international relations.

Development of the line of battle

During the 1650s, the fleets of the European powers generally fought in a

During the 1650s, the fleets of the European powers generally fought in a melee

A melee ( or , French: mêlée ) or pell-mell is disorganized hand-to-hand combat in battles fought at abnormally close range with little central control once it starts. In military aviation, a melee has been defined as " air battle in which ...

style that involved fighting between individual ships, but it became clear to the English that the tactic of firing guns from the broadsides of many ships was more effective, and the government worked to convert the fleet to fight in this way. A large ship was vulnerable to ''raking fire

In naval warfare during the Age of Sail, raking fire was cannon fire directed parallel to the long axis of an enemy ship from ahead (in front of the ship) or astern (behind the ship). Although each shot was directed against a smaller profile ...

'', a volley of cannon balls directly in front or behind it, which could cause considerable damage, and the best protection—and the best form of attack—was having ships sailing together closely and in a straight line. This tactic, known as a ''line of battle

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

'', was used by warships such as the ''Gloucester'', which were large and powerful enough to take their place in the line. Such ships has multiple gun batteries on at least two decks. Around 100 ships could be formed into a line of battle.

The Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

had mobilised quickly at the beginning of the First Dutch War

The First Anglo-Dutch War, or simply the First Dutch War, ( nl, Eerste Engelse (zee-)oorlog, "First English (Sea) War"; 1652–1654) was a conflict fought entirely at sea between the navies of the Commonwealth of England and the United Provinces ...

of 1652 and had double the number of ships possessed by the English—but they were smaller and were unsuitable for attacking the English line of battle. Early in the war the English government, recognising the usefulness of large ships, had ordered 30 frigates, to be built at the end of 1652. An early example of a large frigate, the ''Speaker

Speaker may refer to:

Society and politics

* Speaker (politics), the presiding officer in a legislative assembly

* Public speaker, one who gives a speech or lecture

* A person producing speech: the producer of a given utterance, especially:

** I ...

'', launched in April 1650, provided the prototype for a class of ships. The , launched between 1650 and 1654, were about 750 tons and carried between 48 and 56 cannon. Their introduction caused the Dutch Navy, which was still reliant on the use of armed merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are ...

s, to become largely obsolete. ''Speaker''-class ships had much in common with the old Great Ships planned in 1618, being of a similar size, with two decks and a large number of guns. The class set the pattern for all the two-deck ships built up to the 19th century.

Construction and commissioning

''Gloucester'' (the name of the ship was spelt ''Glocester'' by contemporary sources) was a 'Speaker''-class third rate, and the first British naval vessel ship to be named after the English city of

''Gloucester'' (the name of the ship was spelt ''Glocester'' by contemporary sources) was a 'Speaker''-class third rate, and the first British naval vessel ship to be named after the English city of Gloucester

Gloucester ( ) is a cathedral city and the county town of Gloucestershire in the South West of England. Gloucester lies on the River Severn, between the Cotswolds to the east and the Forest of Dean to the west, east of Monmouth and east ...

. She was ordered by the Commonwealth in December 1652 as part of the unprecedented expansion of the English navy during this period, during which 207 battle ships, including 11 frigates, were built. The ship was probably launched in March 1654.

Series-built third rates were usually built in commercial shipyards, where costs and construction time were reduced where possible. This was in contrast to the construction of all first rate

In the rating system of the British Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a first rate was the designation for the largest ships of the line. Originating in the Jacobean era with the designation of Ships Royal capable of carrying at ...

s and second rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a second-rate was a ship of the line which by the start of the 18th century mounted 90 to 98 guns on three gun decks; earlier 17th-century second rates had fewer guns ...

s, which were built in the Royal Dockyards

Royal Navy Dockyards (more usually termed Royal Dockyards) were state-owned harbour facilities where ships of the Royal Navy were built, based, repaired and refitted. Until the mid-19th century the Royal Dockyards were the largest industrial ...

, where quality control was maintained. The ''Gloucester'' cost the navy £5,473, and was built at Limehouse

Limehouse is a district in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets in East London. It is east of Charing Cross, on the northern bank of the River Thames. Its proximity to the river has given it a strong maritime character, which it retains through ...

in East London under the direction of master shipwright Matthew Graves. She had a length at the gun deck

The term gun deck used to refer to a deck aboard a ship that was primarily used for the mounting of cannon to be fired in broadsides. The term is generally applied to decks enclosed under a roof; smaller and unrated vessels carried their guns ...

of , a beam of , and a depth of hold of . The ship's tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically r ...

was 755 tons burthen. Originally built for 50 guns, by 1667 she was carrying 57 guns (19 demi-cannon

The demi-cannon was a medium-sized cannon, similar to but slightly larger than a culverin and smaller than a regular cannon, developed in the early 17th century. A full cannon fired a 42-pound shot, but these were discontinued in the 18th centur ...

, 4 culverin

A culverin was initially an ancestor of the hand-held arquebus, but later was used to describe a type of medieval and Renaissance cannon. The term is derived from the French "''couleuvrine''" (from ''couleuvre'' "grass snake", following the ...

s, and 34 demi-culverin

The demi-culverin was a medium cannon similar to but slightly larger than a saker and smaller than a regular culverin developed in the late 16th century. Barrels of demi-culverins were typically about long, had a calibre of and could weigh up t ...

s). The ship had a crew of 210340 officers and ratings.

Service

West Indies (1654–1655)

''Gloucester'' was commissioned in 1654, with Benjamin Blake as captain. Under Blake, ''Gloucester'' was with Penn's fleet, an expedition that left England for the Caribbean on Christmas Day 1654. Known as the

''Gloucester'' was commissioned in 1654, with Benjamin Blake as captain. Under Blake, ''Gloucester'' was with Penn's fleet, an expedition that left England for the Caribbean on Christmas Day 1654. Known as the Western Design

The Western Design is the term commonly used for an English expedition against the Spanish West Indies during the 1654 to 1660 Anglo-Spanish War.

Part of an ambitious plan by Oliver Cromwell to end Spanish dominance in the Americas, the force ...

, the expedition—consisting of 17 men-of-war, 20 transports with 3000 troops and horses, and other small craft—was intended by Cromwell to end Spanish dominance in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greate ...

. The expedition was split into two divisions: the first was led to Robert Blake Robert Blake may refer to:

Sportspeople

* Bob Blake (American football) (1885–1962), American football player

* Robbie Blake (born 1976), English footballer

* Bob Blake (ice hockey) (1914–2008), American ice hockey player

* Rob Blake (born 196 ...

(Benjamin Blakes's older brother) in his flagship HMS ''St. George''; the second, was under Penn on HMS ''Swiftsure''. Another Robert Blake in the expedition was the nephew of Benjamin Blake, who sailed with his uncle on the ''Gloucester''.

Little was achieved. On 14 April 1655, English troops landed in Hispaniola and marched inland. After three days they retreated, exhausted by disease and a lack of supplies. A second attack failed, and eventually the troops had to be re-embarked. Penn then moved on to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of His ...

and invaded the island, which surrendered on 17 May.

Penn was succeeded by William Goodsonn. His authority was challenged by Blake, his vice-admiral, who wanted to search for prizes

A prize is an award to be given to a person or a group of people (such as sporting teams and organizations) to recognize and reward their actions and achievements.

, and attack the Caribbean Spanish settlements. Blake, who returned home to England after Goodsonn forced him to resign, was succeeded as captain of the ''Gloucester'' by Richard Newberry. In August 1655 the squadron returned to England, but the ''Gloucester'' and 14 other vessels remained out on Jamaica Station

Jamaica station is a major train station of the Long Island Rail Road located in Jamaica, Queens, New York City. With weekday ridership exceeding 200,000 passengers, it is the largest transit hub on Long Island, the fourth-busiest rail station ...

.

Operations in The Sound (1658)

In November 1658, after a Dutch fleet commanded byJacob van Wassenaer Obdam

Jacob, Banner Lord of Wassenaer, Lord Obdam, Hensbroek, Spanbroek, Opmeer, Zuidwijk and Kernhem (1610 – 13 June 1665) was a Dutch nobleman who became lieutenant admiral, and supreme commander of the navy of the Dutch Republic. The name ''Obd ...

defeated the Swedes in the Battle of the Sound

The Battle of the Sound was a naval engagement which took place on 8 November 1658 (29 October O.S.) during the Second Northern War, near the Sound or Øresund, just north of the Danish capital, Copenhagen. Sweden had invaded Denmark and an army ...

, and lifted the blockade of Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

, the Commonwealth Protector Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell (4 October 162612 July 1712) was an English statesman who was the second and last Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland and son of the first Lord Protector, Oliver Cromwell.

On his father's deat ...

ordered a fleet to be sent to the Sound to protect English interests. ''Gloucester'', captained by William Whitehorne, and with 260 men and 60 guns, was one of 20 ships sent to conduct operations in the Sound, under the command of Goodsonn. The English government sent an expedition as a political gesture to dissuade the Dutch from sending a second fleet to the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

* Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originati ...

.

The expedition left the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

on 18 November 1658. Goodsonn's flagship ''Swiftsure'' attempted to join the fleet, but was forced back to port by strong winds. On 3 December the fleet left England for the Skaw, which many were prevented from rounding when they encountered continuous winds. On 15 December, having accomplished little, Goodsonn decided to return home. That night, a gale damaged nearly every ship, including Goodsonn's flagship. None was lost, and from 22 December until the end of the year, they anchored on the English coast between Great Yarmouth and Harwich.

Anglo-Dutch Wars

Battle of Lowestoft (1660)

Renamed in 1660 as HMS ''Gloucester'', the ship participated in theBattle of Lowestoft

The Battle of Lowestoft took place on during the Second Anglo-Dutch War. A fleet of more than a hundred ships of the United Provinces commanded by Lieutenant-Admiral Jacob van Wassenaer, Lord Obdam attacked an English fleet of equal size comm ...

, forming part of the Red squadron (Van division). The Battle of Lowestoft took place on 3 June 1665, east of the Outer Gabbard and southeast of the English port of Lowestoft. The English under James Stuart, Duke of York

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was depo ...

, fought a Dutch fleet led by Obdam, in what was the first fleet action of the Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo-Dutch War or the Second Dutch War (4 March 1665 – 31 July 1667; nl, Tweede Engelse Oorlog "Second English War") was a conflict between England and the Dutch Republic partly for control over the seas and trade routes, whe ...

, The Dutch had 107 ships, of which 81 were warships and 11 substantial East Indiaman. The English fleet of 100 ships, which included 64 men-of-war

The man-of-war (also man-o'-war, or simply man) was a Royal Navy expression for a powerful warship or frigate from the 16th to the 19th century. Although the term never acquired a specific meaning, it was usually reserved for a ship armed w ...

and 24 merchant ships, was greatly superior in firepower.

At one point during the battle, the firing became heavy enough to be heard in the Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

. The principal event was the sudden explosion of the Dutch flagship '' Eendracht'', which killed Obdam. The Dutch fleet disintegrated and attempted to escape in different directions. By the end of the battle, the English had captured or sunk 17 Dutch ships; a number that would have been larger had not the ensuing pursuit been prematurely called off.

Engagements from May to July 1666

On 5 May 1666, ''Gloucester'', now captained by Robert Clark, saw action against the Dutch off the island ofTexel

Texel (; Texels dialect: ) is a municipality and an island with a population of 13,643 in North Holland, Netherlands. It is the largest and most populated island of the West Frisian Islands in the Wadden Sea. The island is situated north of Den ...

, having been stationed there in April with a small squadron to observe the Dutch fleet. A day after his arrival, Clark intercepted a Dutch flotilla

A flotilla (from Spanish, meaning a small ''flota'' ( fleet) of ships), or naval flotilla, is a formation of small warships that may be part of a larger fleet.

Composition

A flotilla is usually composed of a homogeneous group of the same clas ...

of twelve ships ''en route'' from the Baltic to Amsterdam, and captured seven of the ships. The approach of the enemy's fleet obliged him to leave his station a few days later.

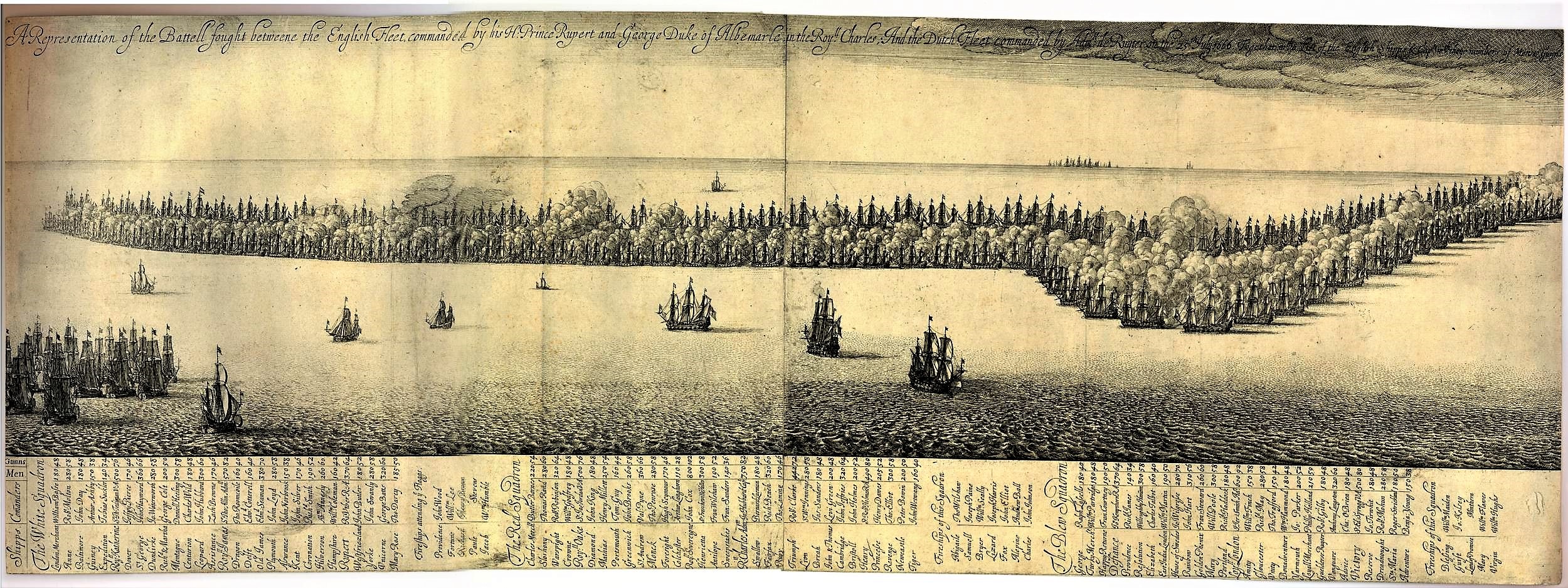

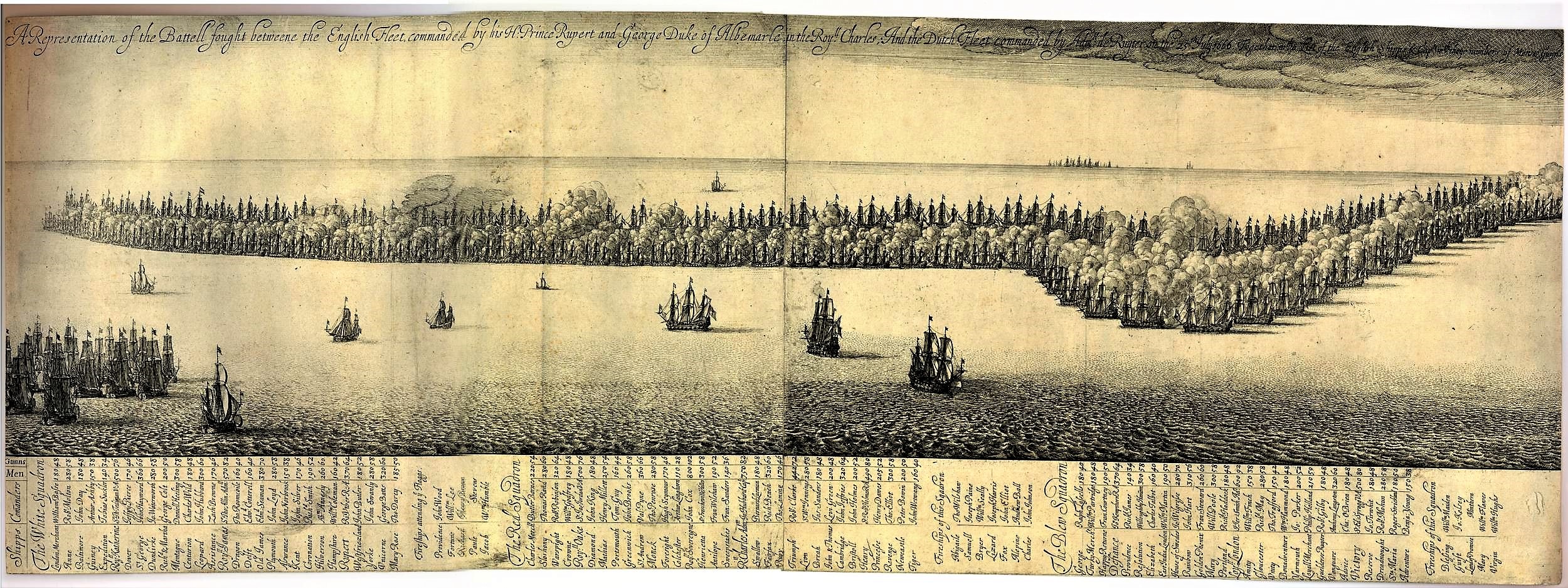

Having met with the Duke of Albemarle at the Gunfleet on 24 May, ''Gloucester'' participated in the Four Days' Battle

The Four Days' Battle, also known as the Four Days' Fight in some English sources and as Vierdaagse Zeeslag in Dutch, was a naval battle of the Second Anglo-Dutch War. Fought from 1 June to 4 June 1666 in the Julian or Old Style calendar that w ...

(14 June 1666). The battle was the longest in British naval history, and has been called the greatest battle of the Age of Sail. ''Gloucester'' formed part of the White squadron, Centre division. Clark “bore as distinguished a part in the action... as the size of the ship he commanded would allow”. The English lost an opportunity to defeat the Dutch after the king decided to divide the fleet, sending Prince Rupert away down the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

with 20 ships towards Ireland, a decision that was reversed once the size of the Dutch threat became clearer. Once the English fleet had manoeuvred east of the Kentish Knock on 1 June, so as to reach the Dutch fleet, battle commenced off North Foreland. On 2 June, the English attacked the Dutch, but the Duke of Albemarle

The Dukedom of Albemarle () has been created twice in the Peerage of England, each time ending in extinction. Additionally, the title was created a third time by James II in exile and a fourth time by his son the Old Pretender, in the Jacobite ...

was forced onto the defensive. The situation was saved the following day when Prince Rupert's ships reappeared. On the last day, squadrons on both sides broke through enemy lines amid heavy fighting, but eventually the battered English fleet was forced to admit defeat and retreat. The English lost 10 ships, most notably the '' Prince Royal''. ''Gloucester'' was totally disabled in the action, with 18 men from the ship killed and 27 men wounded. He was soon afterwards promoted to the command of the second rate

In the rating system of the Royal Navy used to categorise sailing warships, a second-rate was a ship of the line which by the start of the 18th century mounted 90 to 98 guns on three gun decks; earlier 17th-century second rates had fewer guns ...

HMS ''Triumph''.

''Gloucester'' and the other English ships were quickly repaired. In early July 1666, the Dutch appeared at the end of the Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the R ...

and settled there intending to start a blockade—on 22 July the English sailed out, and the two fleets met three days later. Under her captain Richard May, ''Gloucester'' formed part of Blue squadron (Centre division). The St James's Day Battle took place over 25 and 26 July. The weaker and disorganised Dutch fleet, whose line of ships was deliberately made into a snake-like pattern, was heavily defeated.

Attack on the Smyrna fleet (1672)

Under John Holmes, ''Gloucester'' participated in the attack on the Smyrna fleet in the

Under John Holmes, ''Gloucester'' participated in the attack on the Smyrna fleet in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

in March 1672. The ship was part a fleet of 20 ships lying off the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a Counties of England, county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the List of islands of England#Largest islands, largest and List of islands of England#Mo ...

, and commanded by his brother Sir Robert Holmes

Sir Robert Holmes ( – 18 November 1692) was an English Admiral of the Restoration Navy. He participated in the second and third Anglo-Dutch Wars, both of which he is, by some, credited with having started. He was made Governor of the Is ...

. On 12 March the English sighted the Dutch Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

convoy, which consisted of six men-of-war and 66 merchantmen, 24 of which were fully armed. During the fight, five merchantmen were captured, and ''Gloucester'' disabled and captured the ''Klein Hollandia'', which later foundered. The remaining Dutch ships, though damaged, escaped. Holmes, who was wounded during the action, was knighted for his services.

An English squadron under the command of William Coleman, captain of the ''Gloucester'' since 16 April,. narrowly escaped capture early in May 1672. The squadron was on its way to join the Duke of Albemarle, when it was spotted, and 30 Dutch ships, commanded by Willem Joseph van Ghent

Willem Joseph baron van Ghent tot Drakenburgh (14 May 1626 – 7 June 1672) was a 17th-century Dutch admiral. His surname is also sometimes rendered Gendt or Gent.

Early career

Van Ghent was baptised on 14 May 1626, in the church of Wi ...

, were suddenly sent in pursuit. Coleman's squadron succeeded in reaching the dockyard

A shipyard, also called a dockyard or boatyard, is a place where ships are built and repaired. These can be yachts, military vessels, cruise liners or other cargo or passenger ships. Dockyards are sometimes more associated with maintenance ...

at Sheerness relatively unscathed.

The Battle of Solebay (1672)

''Gloucester'' was in the Blue Squadron (Van division) during theBattle of Solebay

The naval Battle of Solebay took place on 28 May Old Style, 7 June New Style 1672 and was the first naval battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War.

The battle began as an attempted raid on Solebay port where an English fleet was anchored and large ...

on 28 May 1672. The battle has been described as one the fiercest engagements in British naval history.

The English and French fleets convened off

The English and French fleets convened off Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

on 5 May. By 18 May, a confrontation between the combined French and English fleets (with a total of 6,018 guns), and the Dutch fleet (4,484 guns), seemed imminent. During a delay of several days, the Dutch attempted unsuccessfully to lure the allies out to sea and towards the shallow waters of the Dutch coast. The allies' fleet instead made for the Suffolk coastal town of Southwold

Southwold is a seaside town and civil parish on the English North Sea coast in the East Suffolk district of Suffolk. It lies at the mouth of the River Blyth within the Suffolk Coast and Heaths Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The town is ...

to obtain provisions and impress

The Independent Monitor for the Press (IMPRESS) is an independent press regulator in the UK. It was the first to be recognised by the Press Recognition Panel. Unlike the Independent Press Standards Organisation (IPSO), IMPRESS is fully compliant ...

men from the town—nearby Sole Bay had the ability to provide ships with a safe haven, and the English were sure that the westerly winds would prevent any sudden attack. It was several days before the Dutch located the allied fleet, but by 27 May they were able to report their position.

When the Dutch fleet was spotted approaching the English coast—achieving the surprise that its commander Michiel de Ruyter

Michiel Adriaenszoon de Ruyter (; 24 March 1607 – 29 April 1676) was a Dutch admiral. Widely celebrated and regarded as one of the most skilled admirals in history, De Ruyter is arguably most famous for his achievements with the Dutch N ...

had wished for—the sailors ashore were forced to rush back onto their ships. The English and French fleets were roughly in formation, the Blue Squadron commanded by Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich

Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich, KG PC FRS JP (27 July 162528 May 1672) was an English military officer, politician and diplomat, who fought for the Parliamentarian army during the First English Civil War and was an MP at various time ...

to the north, the Duke of York with the Red Squadron in the centre, and the French fleet forming the White Squadron to the south. The French mistakenly sailed south and away from the English squadrons, so two separate battles took place for most of the day.

During the battle, the Duke of York's flagship ''Prince'' was targeted by the Dutch, and was damaged enough for him to be forced firstly onto ''St. Michael'', and then to ''London''. The fighting continued throughout the afternoon, with ships locked in combat with each other. The battle produced no clear victory for either side. There was heavy loss of life, with the English losses being the greatest. The Earl of Sandwich's Blue Squadron admirals Sir John Kempthorne and Sir Joseph Jordan lost contact with him after his ship the ''Royal James'' was surrounded, and he was killed when the Dutch destroyed the ship.

Battles of Schooneveld and Battle of Texel (1673)

''Gloucester'' was in Red squadron (Centre division) during the Battles of Schooneveld off the coast of theNetherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

in June 1673. On 4 June, de Ruijter's Dutch fleet were sighted at anchor in Schooneveld

The Schooneveld is a shallow basin at the mouth of the Scheldt river, near the island of Walcheren, off the coast of the Netherlands. It runs parallel to the continental coast, narrowing from the southwest to the northeast, bounded by the irregula ...

by a combined Anglo-French fleet led by Prince Rupert. The battle commenced on 7 June. No ships were captured on either side, but once more the loss of life was heavy. On 14 June the Dutch ships emerged from port, and the second battle of the Schooneveld was fought. The Dutch eventually withdrew, although they had come off best, with neither side losing any ships.

''Gloucester'' took part in the Battle of Texel

The naval Battle of Texel or Battle of Kijkduin took place off the southern coast of island of Texel on 21 August 1673 (11 August O.S.) between the Dutch and the combined English and French fleets. It was the last major battle of the Third A ...

on 11 August 1673, after which she was sent at the end of the year to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

. Texel was the last battle of the Third Anglo-Dutch War

The Third Anglo-Dutch War ( nl, Derde Engels-Nederlandse Oorlog), 27 March 1672 to 19 February 1674, was a naval conflict between the Dutch Republic and England, in alliance with France. It is considered a subsidiary of the wider 1672 to 1678 ...

. An Allied force, consisting of the English and French fleets, met the Dutch fleet. The Allies' intention was to destroy the Dutch at sea as a precursor to a seaborne invasion of Holland. The fleets, which met off the island of Texel, consisted of 86 ships under the command of Prince Rupert, and 60 Dutch ships, commanded by de Ruyter.

After de Ruyter succeeded in separating the French from the main fleet, the French withdrew, and played no further major part in the action. The two fleets were in parallel lines on the same tack, and de Ruyter concentrated on the English centre—and achieved almost equal odds. There was sharp action in the morning, broken off when each side steered to rejoin their rear squadrons. Tromp and Spragge faced one another in what amounted to a personal duel in the rear. No large ships were lost, but many were seriously damaged, and 3,000 men were killed.

Voyage to Scotland (1682)

''Gloucester'' was a valuable asset for the Royal Navy. From 16781680 she was comprehensively and expensively

''Gloucester'' was a valuable asset for the Royal Navy. From 16781680 she was comprehensively and expensively refit

Refitting or refit of boats and marine vessels includes repairing, fixing, restoring, renewing, mending, and renovating an old vessel. Refitting has become one of the most important activities inside a shipyard. It offers a variety of services f ...

ted at Portsmouth, a shortage of funds and materials having repeatedly delayed the work.

In April 1682, ''Gloucester'' was due to be deployed, along with five other ships, to Tangier

Tangier ( ; ; ar, طنجة, Ṭanja) is a city in northwestern Morocco. It is on the Moroccan coast at the western entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar, where the Mediterranean Sea meets the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Spartel. The town is the capi ...

via Ireland, when Sir John Berry

Rear admiral Sir John Berry (14 February 1689 or 1690) was an English officer of the Royal Navy.

Origins and early years

John Berry was born at Knowstone, in the English county of Devon. He was the second of seven sons of Daniel Berry, the vi ...

was appointed to command the ship, and was assigned to transport the Duke of York (the future King James II of England) and his party to Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian on the southern shore of t ...

.

James's intention was to sail from Sheerness to Leith. He intended to settle his affairs as Lord High Commissioner to the Parliament of Scotland, and collect his pregnant wife Mary of Modena (along with his daughter Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

from his previous marriage), before returning to London and taking up residence at his brother Charles’s court. His plan would enable Mary to give birth in England, and so produce an English future heir to the throne.

Amongst the courtier

A courtier () is a person who attends the royal court of a monarch or other royalty. The earliest historical examples of courtiers were part of the retinues of rulers. Historically the court was the centre of government as well as the official ...

s who boarded the ''Gloucester'' were John Churchill (the future Duke of Marlborough), the Master-General of the Ordnance

The Master-General of the Ordnance (MGO) was a very senior British military position from 1415 to 2013 (except 1855–1895 and 1939–1958) with some changes to the name, usually held by a serving general. The Master-General of the Ordnance was ...

George Legge, James Dick (the Lord Provost of Edinburgh), and the Lord President of Scotland, James Graham, Marquess of Montrose

A marquess (; french: marquis ), es, marqués, pt, marquês. is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman w ...

. No document listing those aboard the ''Gloucester'' itself has survived, adding to confusion about which of James's advisers were aboard.

''Gloucester'', together with ''Ruby'', '' Happy Return'', ''Lark

Larks are passerine birds of the family Alaudidae. Larks have a cosmopolitan distribution with the largest number of species occurring in Africa. Only a single species, the horned lark, occurs in North America, and only Horsfield's bush lark oc ...

'', '' Dartmouth'' and ''Pearl'', and the royal yachts ''Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

'', ''Katherine

Katherine, also spelled Catherine, and other variations are feminine names. They are popular in Christian countries because of their derivation from the name of one of the first Christian saints, Catherine of Alexandria.

In the early Christ ...

'', ''Charlotte

Charlotte ( ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of North Carolina. Located in the Piedmont region, it is the county seat of Mecklenburg County. The population was 874,579 at the 2020 census, making Charlotte the 16th-most populo ...

'' and ''Kitchen

A kitchen is a room or part of a room used for cooking and food preparation in a dwelling or in a commercial establishment. A modern middle-class residential kitchen is typically equipped with a stove, a sink with hot and cold running wate ...

'', convened at Margate Road on 3 May. The fleet left the Kent coast the following day, after having taken several hours to carry passengers and baggage and passengers across from the shore to the ships. A large crowd, along with the king and members of the royal court, were present to watch its departure of the fleet.

Bad weather forced the ''Gloucester'' to moor up during the first night. As a signal for the fleet to drop anchor, she fired a gun, but three ships, misinterpreting the signal, sailed out to sea and never re-joined the fleet.

Sinking

On the second evening, a dispute arose between the Duke and several officers—including ''Gloucester''’s pilot, James Ayres—about the correct course to take. Ayres was experienced navigator who was well aware of the dangers posed bysandbanks

Sandbanks is an affluent neighbourhood of Poole, Dorset, on the south coast of England, situated on a narrow spit of around 1 km2 or 0.39 sq mi extending into the mouth of Poole Harbour.

It is known for its high property prices and for it ...

in the waters surrounding the eastern coast of England. Wishing to avoid them, he advocated that the fleet sailed close to the coast. The master of the ''Gloucester'', Benjamin Holmes, advised avoiding the banks by using a deep-sea route. The Duke settled the matter when he decided upon a middle course.

On the night of 5/6 May 1682, ''Gloucester'' was affected by strong winds blowing from the east. At approximately 5.30am the ship struck the Leman and Ower sandbank, about off Great Yarmouth. Once it was realised she was aground, with the sandbank hidden in the dark, ''Gloucester'' fired a gun as a warning of the danger to the other ships. The ship bounced along the sandbank, which was in shallow water at low tide. The force of the ship against the sand broke off the rudder, and water rushed into the ship through a hole in the keel. Less than an hour after she had run aground, the ''Gloucester'' sank.

Rescue efforts

Partly through Berry's efforts and determination to stay with his ship until the end, the Duke was saved. The ship's boats were lowered down, enabling the Duke and some of his courtiers and advisors to reach the safety of the accompanying ships, which had already sent their boats to assist the stricken vessel. James hesitated to leave the ship—he was convinced she would not be lost—only finally abandoning the ''Gloucester'' once it was realised she could not be saved,Protocol

Protocol may refer to:

Sociology and politics

* Protocol (politics), a formal agreement between nation states

* Protocol (diplomacy), the etiquette of diplomacy and affairs of state

* Etiquette, a code of personal behavior

Science and technolog ...

dictated that no-one could abandon a ship while there was still a member of the royal family aboard, so James' reluctance to leave the ''Gloucester'', and his insistence that his strongbox containing his political documents should also be loaded onto his boat, delayed the start of the evacuation. A second boat lowered from the ''Gloucester'' was quickly filled with passengers and crew. Other boats managed to rescue more people, and many were saved, but between 130 to 250 sailors and passengers lost their lives. Amongst those drowned were Robert Ker, 3rd Earl of Roxburghe

Robert Ker, 3rd Earl of Roxburghe PC (6 May 1682) was a Scottish nobleman.

Early life

Ker was the eldest son of four sons born to William Ker, 2nd Earl of Roxburghe and the Honourable Jane Ker, who were first cousins. Among his younger broth ...

, Donough O'Brien, Lord Ibrackan, Lord Hopton, and the Duke of York's brother-in-law James Hyde, who was a second lieutenant on the ''Gloucester''. A letter published soon after the disaster revealed that nearly all the duke's retinue of servants had drowned as well.

Aftermath

The Duke of York completed his voyage to Scotland on board the yacht ''Mary'', accompanied by the ''Katherine'' and the ''Charlotte''. On 7 May he reached Edinburgh, and was reunited with his family. The sinking of ''Gloucester'' "became key to the political fortunes and perceptions of the Duke". He was later accused of having "taken particular care of his strong-box, his dogs, and his priests", while George Legge "with drawn sword kept off the other passengers". James denied any responsibility for the loss of life, instead blaming the ship's captain, James Ayres, and demanding that he be hanged immediately. Ayres was subsequently court-martialled and imprisoned, but released after being incarcerated for a year.Discovery of the wreck

underwater divers

This is a list of underwater divers whose exploits have made them notable.

Underwater divers are people who take part in underwater diving activities – Underwater diving is practiced as part of an occupation, or for recreation, where t ...

that included brothers Julian and Lincoln Barnwell. They retrieved a variety of artefacts, including a Royal Navy cannon and a Bartmann jug

A Bartmann jug (from German ', "bearded man"), also called a Bellarmine jug, is a type of decorated salt-glazed stoneware that was manufactured in Europe throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, especially in the Cologne region, in what is today w ...

. The finding of a 1674 pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85–99%), antimony (approximately 5–10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. Copper and antimony (and in antiquity lead) act as hardeners, but lead may be used in lower grades ...

teaspoon produced by the English manufacturer Daniel Barton ruled out the possibility of the wreck being HMS ''Kent'', the only other Royal Navy ship of the period to be shipwrecked in the area. Also found was a wine bottle with a seal

Seal may refer to any of the following:

Common uses

* Pinniped, a diverse group of semi-aquatic marine mammals, many of which are commonly called seals, particularly:

** Earless seal, or "true seal"

** Fur seal

* Seal (emblem), a device to imp ...

of George Legge's family heraldic crest

A crest is a component of a heraldic display, consisting of the device borne on top of the helm. Originating in the decorative sculptures worn by knights in tournaments and, to a lesser extent, battles, crests became solely pictorial after th ...

, and a bottle of fine claret

Bordeaux wine ( oc, vin de Bordèu, french: vin de Bordeaux) is produced in the Bordeaux region of southwest France, around the city of Bordeaux, on the Garonne River. To the north of the city the Dordogne River joins the Garonne forming the ...

with the emblem of the Sun Tavern (in Fish Street in the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London f ...

). The owner of the Sun Tavern was responsible for victualling the British navy, and so the bottle provided evidence that the wreck was that of a Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

ship. Other items found included navigational aids, clothing, footwear and other personal possessions. Some animal bones were discovered, but there were no signs of any human remains.

The discovery of the ship's bell

A ship's bell is a bell on a ship that is used for the indication of time as well as other traditional functions. The bell itself is usually made of brass or bronze, and normally has the ship's name engraved or cast on it.

Strikes Timing of s ...

in 2012 enabled the identity of the wreck to be confirmed by the Receiver of Wreck

The Receiver of Wreck is an official who administers law dealing with maritime wrecks and salvage in some countries having a British administrative heritage. In the United Kingdom, the Receiver of Wreck is also appointed to retain the possession o ...

and the UK Ministry of Defence

The Ministry of Defence (MOD or MoD) is the department responsible for implementing the defence policy set by His Majesty's Government, and is the headquarters of the British Armed Forces.

The MOD states that its principal objectives are to ...

. The bell was inscribed with "1681", the year it was cast

Cast may refer to:

Music

* Cast (band), an English alternative rock band

* Cast (Mexican band), a progressive Mexican rock band

* The Cast, a Scottish musical duo: Mairi Campbell and Dave Francis

* ''Cast'', a 2012 album by Trespassers William

...

.

The announcement of the finding of ''Gloucester'' was made in 2022, having had to wait until after the ship's identity was confirmed, but also to protect the site, which is located in international waters. At a press conference in June 2022, Claire Jowitt, a maritime historian

Maritime may refer to:

Geography

* Maritime Alps, a mountain range in the southwestern part of the Alps

* Maritime Region, a region in Togo

* Maritime Southeast Asia

* The Maritimes, the Canadian provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Princ ...

at the University of East Anglia

The University of East Anglia (UEA) is a public research university in Norwich, England. Established in 1963 on a campus west of the city centre, the university has four faculties and 26 schools of study. The annual income of the institution f ...

, said the circumstances of the sinking meant that it "can be claimed as the single most significant historic maritime discovery since the raising of the ''Mary Rose

The ''Mary Rose'' (launched 1511) is a carrack-type warship of the English Tudor navy of King Henry VIII. She served for 33 years in several wars against France, Scotland, and Brittany. After being substantially rebuilt in 1536, she saw her ...

'' in 1982", and that the discovery "would fundamentally change urunderstanding of 17th century social, maritime and political history”.

''The Last Voyage of the Gloucester: Norfolk’s Royal Shipwreck 1682'', an exhibition relating to the wreck, will be held at the Castle Museum in Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

during 2023. The exhibition will bring together artefacts from the wreck, new research into the context of the discovery, and artistic responses to it.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * 52 61 * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * * *External links

The Gloucester Project

(the project by the

University of East Anglia

The University of East Anglia (UEA) is a public research university in Norwich, England. Established in 1963 on a campus west of the city centre, the university has four faculties and 26 schools of study. The annual income of the institution f ...

to provide a history of the Gloucester warship)

Speaker-class ships of the line

Ships built in Limehouse

Shipwrecks of England

1650s ships

Shipwrecks in the North Sea

Maritime incidents in 1682

{{WarshipHist