Hutton's Unconformity on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hutton's Unconformity is a name given to various notable

Later that year Hutton read an abstract of ''Concerning the System of the Earth, its Duration and Stability'' to a Society meeting, and had it printed and circulated privately. In it, he outlined his theory that the "solid parts of the present land appear in general, to have been composed of the productions of the sea, and of other materials similar to those now found upon the shores."

From this he deduced that the land was a composition which had been formed by the operation of second causes in an earlier world composed of sea and land, with tides, currents, and "such operations at the bottom of the sea as now take place" so that "while the present land was forming at the bottom of the ocean, the former land maintained plants and animals; at least the sea was then inhabited by animals, in a similar manner as it is at present", and that most, if not all, of the land had been produced by natural operations involving the consolidation of masses of loose materials collected at the bottom of the sea, followed by the elevation of the consolidated masses to their present position.''Concerning the System of the Earth''

Later that year Hutton read an abstract of ''Concerning the System of the Earth, its Duration and Stability'' to a Society meeting, and had it printed and circulated privately. In it, he outlined his theory that the "solid parts of the present land appear in general, to have been composed of the productions of the sea, and of other materials similar to those now found upon the shores."

From this he deduced that the land was a composition which had been formed by the operation of second causes in an earlier world composed of sea and land, with tides, currents, and "such operations at the bottom of the sea as now take place" so that "while the present land was forming at the bottom of the ocean, the former land maintained plants and animals; at least the sea was then inhabited by animals, in a similar manner as it is at present", and that most, if not all, of the land had been produced by natural operations involving the consolidation of masses of loose materials collected at the bottom of the sea, followed by the elevation of the consolidated masses to their present position.''Concerning the System of the Earth''

abstract

In 1785 on Hutton's first field excursion, he was invited by the

In 1785 on Hutton's first field excursion, he was invited by the  On a trip to the Isle of Arran in 1787 he found his first example of an unconformity to the north of Newton Point near Lochranza, but the limited view did not give the information he needed. It occurs where vertically orientated Precambrian

On a trip to the Isle of Arran in 1787 he found his first example of an unconformity to the north of Newton Point near Lochranza, but the limited view did not give the information he needed. It occurs where vertically orientated Precambrian

Around the start of June 1788, Hutton went with

Around the start of June 1788, Hutton went with

geological

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other E ...

sites in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

identified by the 18th-century Scottish geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the solid, liquid, and gaseous matter that constitutes Earth and other terrestrial planets, as well as the processes that shape them. Geologists usually study geology, earth science, or geophysics, althoug ...

James Hutton as places where the junction between two types of rock formations can be seen. This geological phenomenon marks the location where rock formations created at different times and by different forces adjoin. For Hutton, such an unconformity

An unconformity is a buried erosional or non-depositional surface separating two rock masses or strata of different ages, indicating that sediment deposition was not continuous. In general, the older layer was exposed to erosion for an interval ...

provided evidence for his Plutonist theories of uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

and the age of Earth.

An unconformity is any break in the normal progression of sedimentary deposits, which are laid the newer on top of the older.

In his search, Hutton and colleagues examined rock outcrops and cliffs, both riverside and sea, and found several locations where two adjoining rock types had been laid bare, the most noted being at Siccar Point

Siccar Point is a rocky promontory in the county of Berwickshire on the east coast of Scotland.

It is famous in the history of geology for Hutton's Unconformity found in 1788, which James Hutton regarded as conclusive proof of his uniformitar ...

on the coast of Berwickshire

Berwickshire ( gd, Siorrachd Bhearaig) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in south-eastern Scotland, on the English border. Berwickshire County Council existed from 1890 until 1975, when the area became part of t ...

.

Theory of rock formations

Hutton hit on a variety of ideas to explain therock formations

A rock formation is an isolated, scenic, or spectacular surface rock outcrop. Rock formations are usually the result of weathering and erosion sculpting the existing rock. The term ''rock formation'' can also refer to specific sedimen ...

he saw, and, after a quarter century of work, he read his paper, ''Theory of the Earth

''Theory of the Earth'' was a publication by James Hutton which laid the foundations for geology. In it he showed that the Earth is the product of natural forces. What could be seen happening today, over long periods of time, could produce what ...

; or an Investigation of the Laws Observable in the Composition, Dissolution and Restoration of Land upon the Globe,'' to the Royal Society of Edinburgh on 7 March and 4 April 1785.

Later that year Hutton read an abstract of ''Concerning the System of the Earth, its Duration and Stability'' to a Society meeting, and had it printed and circulated privately. In it, he outlined his theory that the "solid parts of the present land appear in general, to have been composed of the productions of the sea, and of other materials similar to those now found upon the shores."

From this he deduced that the land was a composition which had been formed by the operation of second causes in an earlier world composed of sea and land, with tides, currents, and "such operations at the bottom of the sea as now take place" so that "while the present land was forming at the bottom of the ocean, the former land maintained plants and animals; at least the sea was then inhabited by animals, in a similar manner as it is at present", and that most, if not all, of the land had been produced by natural operations involving the consolidation of masses of loose materials collected at the bottom of the sea, followed by the elevation of the consolidated masses to their present position.''Concerning the System of the Earth''

Later that year Hutton read an abstract of ''Concerning the System of the Earth, its Duration and Stability'' to a Society meeting, and had it printed and circulated privately. In it, he outlined his theory that the "solid parts of the present land appear in general, to have been composed of the productions of the sea, and of other materials similar to those now found upon the shores."

From this he deduced that the land was a composition which had been formed by the operation of second causes in an earlier world composed of sea and land, with tides, currents, and "such operations at the bottom of the sea as now take place" so that "while the present land was forming at the bottom of the ocean, the former land maintained plants and animals; at least the sea was then inhabited by animals, in a similar manner as it is at present", and that most, if not all, of the land had been produced by natural operations involving the consolidation of masses of loose materials collected at the bottom of the sea, followed by the elevation of the consolidated masses to their present position.''Concerning the System of the Earth''abstract

Hutton's search for unconformities

Early geologists had interpreted angular unconformities in terms ofNeptunism

Neptunism is a superseded scientific theory of geology proposed by Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749–1817) in the late 18th century, proposing that rocks formed from the crystallisation of minerals in the early Earth's oceans.

The theory took its n ...

(holding that rocks had formed from the crystallisation of minerals from ocean waters after the Great Flood) but Hutton wanted to examine such formations himself in support for his theory of Plutonism, in which rocks are formed from volcanic action.

In 1785 on Hutton's first field excursion, he was invited by the

In 1785 on Hutton's first field excursion, he was invited by the Duke of Atholl

Duke of Atholl, named for Atholl in Scotland, is a title in the Peerage of Scotland held by the head of Clan Murray. It was created by Queen Anne in 1703 for John Murray, 2nd Marquess of Atholl, with a special remainder to the heir male of ...

to search for exposures in a remarkably straight, deeply incised valley in the Scottish Highlands known as the Glen Tilt

Glen Tilt (Scottish Gaelic: Gleann Teilt) is a glen in the extreme north of Perthshire, Scotland. Beginning at the confines of Aberdeenshire, it follows a South-westerly direction excepting for the last 4 miles, when it runs due south to Blai ...

, near the town of Blair Atholl

Blair Atholl (from the Scottish Gaelic: ''Blàr Athall'', originally ''Blàr Ath Fhodla'') is a village in Perthshire, Scotland, built about the confluence of the Rivers Tilt and Garry in one of the few areas of flat land in the midst of the Gr ...

. Upstream of one of the Duke's hunting lodges, known as Forest Lodge, Hutton and his friend, John Clerk of Eldin

John Clerk of Eldin FRSE FSAScot (10 December 1728 – 10 May 1812) was a Scottish merchant, naval author, artist, geologist and landowner. The 7th son of Sir John Clerk of Penicuik, Bt, Clerk of Eldin was a figure in the Scottish Enlightenm ...

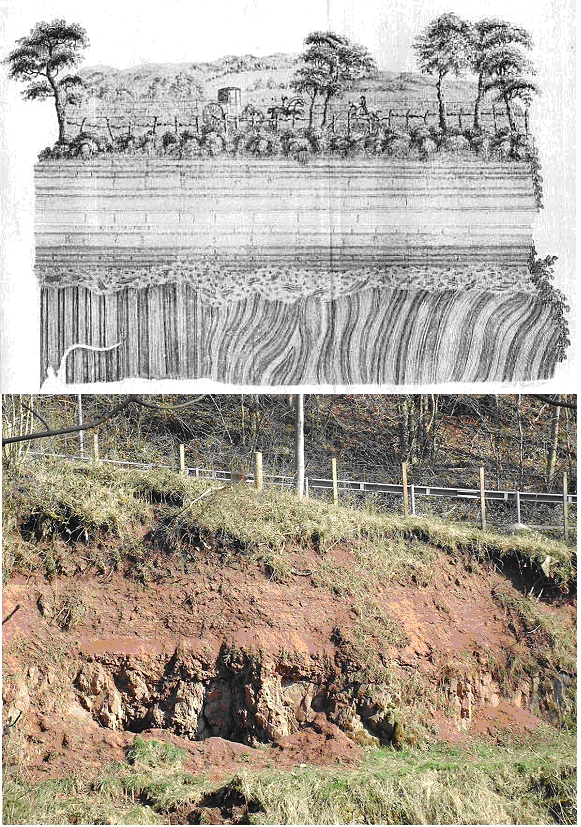

, found exposures at the Dail-an-eas Bridge that demonstrated red igneous granite veins were injected into older grey schists formations. This discovery proved that Werner's Neptunism theory was in error. Werner argued that sedimentary rocks, including what are now known as metamorphic rocks such as schists, were formed after granites. John Clerk drew these exposures with great accuracy and these drawing provide important visual evidence of Hutton's discoveries.

On a trip to the Isle of Arran in 1787 he found his first example of an unconformity to the north of Newton Point near Lochranza, but the limited view did not give the information he needed. It occurs where vertically orientated Precambrian

On a trip to the Isle of Arran in 1787 he found his first example of an unconformity to the north of Newton Point near Lochranza, but the limited view did not give the information he needed. It occurs where vertically orientated Precambrian Dalradian

The Dalradian Supergroup (informally and traditionally the Dalradian) is a stratigraphic unit (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of the Grampian Highlands of Scotland and in the north and west of Ireland. The diverse assembla ...

schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

s are overlain by more recent cornstones in the Kinnesswood Formation of the Inverclyde Group (Lower Carboniferous

Lower may refer to:

*Lower (surname)

*Lower Township, New Jersey

*Lower Receiver (firearms)

*Lower Wick Gloucestershire, England

See also

*Nizhny

Nizhny (russian: Ни́жний; masculine), Nizhnyaya (; feminine), or Nizhneye (russian: Ни́� ...

), with an obvious difference in dip between the two rock

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wales ...

layers

Layer or layered may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Layers'' (Kungs album)

* ''Layers'' (Les McCann album)

* ''Layers'' (Royce da 5'9" album)

*"Layers", the title track of Royce da 5'9"'s sixth studio album

*Layer, a female Maveric ...

, but he incorrectly thought that the strata were conformable at a depth below the exposed outcrop. In 2017, the Arran Geopark Project erected a marker stone to indicate the significance of Hutton's discovery and its location (map reference: NR936521)

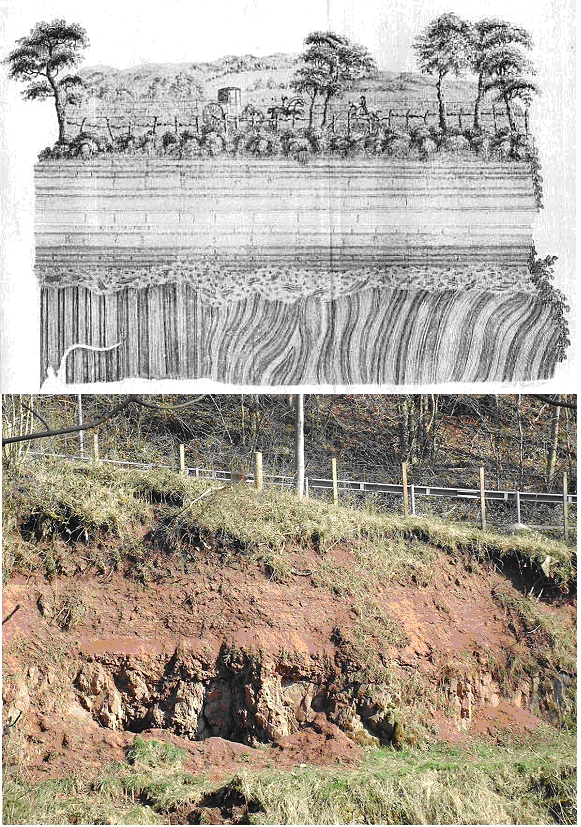

Later in 1787 Hutton noted what is now known as the Hutton Unconformity at Inchbonny, Jedburgh

Jedburgh (; gd, Deadard; sco, Jeddart or ) is a town and former royal burgh in the Scottish Borders and the traditional county town of the historic county of Roxburghshire, the name of which was randomly chosen for Operation Jedburgh in s ...

, in layers of sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock that are formed by the accumulation or deposition of mineral or organic particles at Earth's surface, followed by cementation. Sedimentation is the collective name for processes that cause these particles ...

visible on the banks of the Jed Water

The Jed Water is a river and a tributary of the River Teviot in the Borders region of Scotland.

In total the Jed Water is over long and it falls . It flows into the Teviot near Jedfoot Bridge () two miles north of Jedburgh. Jed Water rises fro ...

. He later wrote of how he "rejoiced at my good fortune in stumbling upon an object so interesting in the natural history of the earth, and which I had been long looking for in vain". That year he found the same sequence in Teviotdale

Roxburghshire or the County of Roxburgh ( gd, Siorrachd Rosbroig) is a historic county and registration county in the Southern Uplands of Scotland. It borders Dumfriesshire to the west, Selkirkshire and Midlothian to the north-west, and ...

.

Siccar Point

Around the start of June 1788, Hutton went with

Around the start of June 1788, Hutton went with John Playfair

John Playfair FRSE, FRS (10 March 1748 – 20 July 1819) was a Church of Scotland minister, remembered as a scientist and mathematician, and a professor of natural philosophy at the University of Edinburgh. He is best known for his book ''Illu ...

to the Berwickshire

Berwickshire ( gd, Siorrachd Bhearaig) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area in south-eastern Scotland, on the English border. Berwickshire County Council existed from 1890 until 1975, when the area became part of t ...

coast and found more examples of this sequence in the valleys of the Tour and Pease Burns near Cockburnspath

Cockburnspath ( ; sco, Co’path) is a village in the Scottish Borders area of Scotland. It lies near the North Sea coast between Berwick-upon-Tweed and Edinburgh. It is at the eastern extremity of the Southern Upland Way a long-distance footpa ...

. They then took a boat trip from Dunglass Burn east along the coast with the geologist Sir James Hall of Dunglass

Dunglass is a hamlet in East Lothian, Scotland, lying east of the Lammermuir Hills on the North Sea coast, within the parish of Oldhamstocks. It has a 15th-century collegiate church, now in the care of Historic Scotland. Dunglass is the birthpla ...

. They found the sequence in the cliff below St. Helens, then just to the east at Siccar Point

Siccar Point is a rocky promontory in the county of Berwickshire on the east coast of Scotland.

It is famous in the history of geology for Hutton's Unconformity found in 1788, which James Hutton regarded as conclusive proof of his uniformitar ...

found what Hutton called "a beautiful picture of this junction washed bare by the sea".

Continuing along the coast, they made more discoveries including sections of the vertical beds showing strong ripple marks which gave Hutton "great satisfaction" as a confirmation of his supposition that these beds had been laid horizontally in water.

Playfair wrote:Gillen, Con (2003) ''Geology and landscapes of Scotland''. Harpenden. Terra Publishing. Page 95.

At Siccar Point, during the lower Silurian Llandovery epoch around 435 million years ago, thin beds of fine-grained mudstone were laid down gradually deep in the Iapetus Ocean, alternating with thicker layers of hard greywacke

Greywacke or graywacke (German ''grauwacke'', signifying a grey, earthy rock) is a variety of sandstone generally characterized by its hardness, dark color, and poorly sorted angular grains of quartz, feldspar, and small rock fragments or lit ...

formed when torrents swept unsorted sandstone down the continental slope

A continental margin is the outer edge of continental crust abutting oceanic crust under coastal waters. It is one of the three major zones of the ocean floor, the other two being deep-ocean basins and mid-ocean ridges. The continental margin ...

. During the following 65 million years, the ocean closed and the layers of rock were buckled almost vertically, getting forced to the surface as the ocean floor was subducted

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

under the northern continent. Erosion of the exposed edges of layers formed a characteristic shape of ribs of hard greywacke with narrow gaps where mudstone was worn away, and fragments of greywacke lay on the surface as a talus deposit

Scree is a collection of broken rock fragments at the base of a cliff or other steep rocky mass that has accumulated through periodic rockfall. Landforms associated with these materials are often called talus deposits. Talus deposits typically h ...

. In the Famennian

The Famennian is the latter of two faunal stages in the Late Devonian Epoch. The most recent estimate for its duration estimates that it lasted from around 371.1 million years ago to 359.3 million years ago. An earlier 2012 estimate, still used b ...

Late Devonian period around 370 million years ago this was a low-lying tropical area just south of the equator, where rainy season rivers deposited sands and silts rich in iron oxide, then during the dry seasons these were blown about by winds to form easily eroded layers and dunes. Over time these consolidated to form rocks; initially mixed with the greywacke fragments to form a basal conglomerate which has been defined as the Redheugh Mudstone Formation and dated by fossils of '' Bothriolepis hicklingi''. Above this, layers of Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the northeastern seaboard of North America. It also exte ...

formed the Greenheugh Sandstone Formation which is estimated to be around thick. This in turn was uplifted above the sea, tilting to a shallow slope, then eroded in places such as Siccar Point to expose the underlying layers.

See also

*Geology of Scotland

The geology of Scotland is unusually varied for a country of its size, with a large number of differing geological features.Keay & Keay (1994) page 415. There are three main geographical sub-divisions: the Highlands and Islands is a diverse area w ...

References

External links

{{Commons category, Hutton's Unconformities Isle of Arran Historical geology Stratigraphy of the United Kingdom Geology of Scotland Unconformities