House Of Lords Of The United Kingdom on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the

The status of the House of Lords returned to the forefront of debate after the election of a Liberal Government in 1906. In 1909 the

The status of the House of Lords returned to the forefront of debate after the election of a Liberal Government in 1906. In 1909 the

The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreed, after the 2010 general election, to outline clearly a provision for a wholly or mainly elected second chamber, elected by proportional representation. These proposals sparked a debate on 29 June 2010. As an interim measure, appointment of new peers would reflect the shares of the vote secured by the political parties in the last general election.

Detailed proposals for Lords reform, including a draft House of Lords Reform Bill, were published on 17 May 2011. These included a 300-member hybrid house, of whom 80% would be elected. A further 20% would be appointed, and reserve space would be included for some Church of England archbishops and bishops. Under the proposals, members would also serve single non-renewable terms of 15 years. Former MPs would be allowed to stand for election to the Upper House, but members of the Upper House would not be immediately allowed to become MPs.

The details of the proposal were:

* The upper chamber shall continue to be known as the House of Lords for legislative purposes.

* The reformed House of Lords should have 300 members of whom 240 are "Elected Members" and 60 appointed "Independent Members". Up to 12 Church of England archbishops and bishops may sit in the house as ''ex officio'' "Lords Spiritual".

* Elected Members will serve a single, non-renewable term of 15 years.

* Elections to the reformed Lords should take place at the same time as elections to the House of Commons.

* Elected Members should be elected using the

The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreed, after the 2010 general election, to outline clearly a provision for a wholly or mainly elected second chamber, elected by proportional representation. These proposals sparked a debate on 29 June 2010. As an interim measure, appointment of new peers would reflect the shares of the vote secured by the political parties in the last general election.

Detailed proposals for Lords reform, including a draft House of Lords Reform Bill, were published on 17 May 2011. These included a 300-member hybrid house, of whom 80% would be elected. A further 20% would be appointed, and reserve space would be included for some Church of England archbishops and bishops. Under the proposals, members would also serve single non-renewable terms of 15 years. Former MPs would be allowed to stand for election to the Upper House, but members of the Upper House would not be immediately allowed to become MPs.

The details of the proposal were:

* The upper chamber shall continue to be known as the House of Lords for legislative purposes.

* The reformed House of Lords should have 300 members of whom 240 are "Elected Members" and 60 appointed "Independent Members". Up to 12 Church of England archbishops and bishops may sit in the house as ''ex officio'' "Lords Spiritual".

* Elected Members will serve a single, non-renewable term of 15 years.

* Elections to the reformed Lords should take place at the same time as elections to the House of Commons.

* Elected Members should be elected using the

The chamber's membership again expanded in the following decades, increasing to above eight hundred active members in 2014 and prompting further reforms in the House of Lords Reform Act that year.

In April 2011, a cross-party group of former leading politicians, including many senior members of the House of Lords, called on the Prime Minister

The chamber's membership again expanded in the following decades, increasing to above eight hundred active members in 2014 and prompting further reforms in the House of Lords Reform Act that year.

In April 2011, a cross-party group of former leading politicians, including many senior members of the House of Lords, called on the Prime Minister

upper house

An upper house is one of two Debate chamber, chambers of a bicameralism, bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the lower house.''Bicameralism'' (1997) by George Tsebelis The house formally designated as the upper house is usually smalle ...

of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

. Membership is by appointment

Appointment may refer to:

Law

*The prerogative power of a government official or executive to select persons to fill an honorary position or employment in the government (political appointments, poets laureate)

* Power of appointment, the legal ...

, heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic inform ...

or official function. Like the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, it meets in the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

in London, England

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

.

The House of Lords scrutinises bills that have been approved by the House of Commons. It regularly reviews and amends bills from the Commons. While it is unable to prevent bills passing into law, except in certain limited circumstances, it can delay bills and force the Commons to reconsider their decisions. In this capacity, the House of Lords acts as a check on the more powerful House of Commons that is independent of the electoral process. While members of the Lords may also take on roles as government ministers, high-ranking officials such as cabinet ministers are usually drawn from the Commons. The House of Lords does not control the term of the prime minister or of the government. Only the lower house may force the prime minister to resign or call elections.

While the House of Commons has a defined number of members, the number of members in the House of Lords is not fixed. Currently, it has sitting members. The House of Lords is the only upper house of any bicameral parliament

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

in the world to be larger than its lower house, and is the second-largest legislative chamber in the world behind the Chinese National People's Congress.

The King's Speech is delivered in the House of Lords during the State Opening of Parliament

The State Opening of Parliament is a ceremonial event which formally marks the beginning of a session of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It includes a speech from the throne known as the King's (or Queen's) Speech. The event takes place ...

. In addition to its role as the upper house, until the establishment of the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

in 2009, the House of Lords, through the Law Lords

Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, commonly known as Law Lords, were judges appointed under the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876 to the British House of Lords, as a committee of the House, effectively to exercise the judicial functions of the House of ...

, acted as the final court of appeal in the United Kingdom judicial system. The House of Lords also has a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

role, in that Church Measures must be tabled within the House by the Lords Spiritual.

History

Today's Parliament of the United Kingdom largely descends, in practice, from theParliament of England

The Parliament of England was the legislature of the Kingdom of England from the 13th century until 1707 when it was replaced by the Parliament of Great Britain. Parliament evolved from the great council of bishops and peers that advised t ...

, through the Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new state of Great Britain, stating that the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Kingdom of Scotland were to be "United i ...

of 1706 and the Acts of Union that ratified the Treaty in 1707 and created a new Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a new unified Kingdo ...

to replace the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland ( sco, Pairlament o Scotland; gd, Pàrlamaid na h-Alba) was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland from the 13th century until 1707. The parliament evolved during the early 13th century from the king's council o ...

. This new parliament was, in effect, the continuation of the Parliament of England with the addition of 45 Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MPs) and 16 Peers to represent Scotland.

The House of Lords developed from the "Great Council" (''Magnum Concilium

In the Kingdom of England, the (Latin for "Great Council") was an assembly historically convened at certain times of the year when the English baronage and church leaders were summoned to discuss the affairs of the country with the king. In the ...

'') that advised the king during medieval times. Loveland (2009) p. 158 This royal council came to be composed of ecclesiastics, noblemen, and representatives of the counties of England

The counties of England are areas used for different purposes, which include administrative, geographical, cultural and political demarcation. The term "county" is defined in several ways and can apply to similar or the same areas used by each ...

and Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

(afterwards, representatives of the boroughs

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle Ag ...

as well). The first English Parliament is often considered to be the "Model Parliament

The Model Parliament is the term, attributed to Frederic William Maitland, used for the 1295 Parliament of England of King Edward I.

History

This assembly included members of the clergy and the aristocracy, as well as representatives from the v ...

" (held in 1295), which included archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls, barons, and representatives of the shires and boroughs.

The power of Parliament grew slowly, fluctuating as the strength of the monarchy grew or declined. For example, during much of the reign of Edward II

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir apparent to t ...

(1307–1327), the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy (class), aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below Royal family, royalty. Nobility has often been an Estates of the realm, estate of the realm with many e ...

was supreme, the Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

weak, and the shire and borough representatives entirely powerless.

During the reign of Edward II's successor, Edward III

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England and Lord of Ireland from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring r ...

, Parliament clearly separated into two distinct chambers

Chambers may refer to:

Places

Canada:

*Chambers Township, Ontario

United States:

*Chambers County, Alabama

* Chambers, Arizona, an unincorporated community in Apache County

* Chambers, Nebraska

* Chambers, West Virginia

* Chambers Township, Hol ...

: the House of Commons (consisting of the shire and borough representatives) and the House of Lords (consisting of the archbishops, bishops, abbots and nobility). The authority of Parliament continued to grow, and during the early 15th century both Houses exercised powers to an extent not seen before. The Lords were far more powerful than the Commons because of the great influence of the great landowners and the prelates of the realm.

The power of the nobility declined during the civil wars of the late 15th century, known as the Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses (1455–1487), known at the time and for more than a century after as the Civil Wars, were a series of civil wars fought over control of the English throne in the mid-to-late fifteenth century. These wars were fought bet ...

. Much of the nobility was killed on the battlefield or executed for participation in the war, and many aristocratic estates were lost to the Crown. Moreover, feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

was dying, and the feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a wa ...

armies controlled by the barons

Baron is a rank of nobility or title of honour, often hereditary, in various European countries, either current or historical. The female equivalent is baroness. Typically, the title denotes an aristocrat who ranks higher than a lord or knigh ...

became obsolete. Henry VII (1485–1509) clearly established the supremacy of the monarch, symbolised by the "Crown Imperial". The domination of the Sovereign continued to grow during the reigns of the Tudor monarchs in the 16th century. The Crown was at the height of its power during the reign of Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

(1509–1547).

The House of Lords remained more powerful than the House of Commons, but the Lower House continued to grow in influence, reaching a zenith in relation to the House of Lords during the middle 17th century. Conflicts between the King and the Parliament (for the most part, the House of Commons) ultimately led to the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

during the 1640s. In 1649, after the defeat and execution of King Charles I, the Commonwealth of England

The Commonwealth was the political structure during the period from 1649 to 1660 when England and Wales, later along with Ireland and Scotland, were governed as a republic after the end of the Second English Civil War and the trial and execut ...

was declared, but the nation was effectively under the overall control of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

, Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland.

The House of Lords was reduced to a largely powerless body, with Cromwell and his supporters in the Commons dominating the Government. On 19 March 1649, the House of Lords was abolished by an Act of Parliament, which declared that "The Commons of England ind

Ind or IND may refer to:

General

* Independent (politician), a politician not affiliated to any political party

* Independent station, used within television program listings and the television industry for a station that is not affiliated with ...

by too long experience that the House of Lords is useless and dangerous to the people of England." The House of Lords did not assemble again until the Convention Parliament met in 1660 and the monarchy was restored. It returned to its former position as the more powerful chamber of Parliament—a position it would occupy until the 19th century.

19th century

The 19th century was marked by several changes to the House of Lords. The House, once a body of only about 50 members, had been greatly enlarged by the liberality ofGeorge III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

and his successors in creating peerages. The individual influence of a Lord of Parliament was thus diminished.

Moreover, the power of the House as a whole decreased, whilst that of the House of Commons grew. Particularly notable in the development of the Lower House's superiority was the Reform Act of 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major changes to the electo ...

. The electoral system of the House of Commons was far from democratic: property qualifications greatly restricted the size of the electorate, and the boundaries of many constituencies had not been changed for centuries. Entire cities such as Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

had not even one representative in the House of Commons, while the 11 voters of Old Sarum

Old Sarum, in Wiltshire, South West England, is the now ruined and deserted site of the earliest settlement of Salisbury. Situated on a hill about north of modern Salisbury near the A345 road, the settlement appears in some of the earliest re ...

retained their ancient right to elect two MPs despite living elsewhere. A small borough was susceptible to bribery, and was often under the control of a patron, whose nominee was guaranteed to win an election. Some aristocrats were patrons of numerous " pocket boroughs", and therefore controlled a considerable part of the membership of the House of Commons.

When the House of Commons passed a Reform Bill to correct some of these anomalies in 1831, the House of Lords rejected the proposal. The popular cause of reform, however, was not abandoned by the ministry, despite a second rejection of the bill in 1832. Prime Minister Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey

Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey (13 March 1764 – 17 July 1845), known as Viscount Howick between 1806 and 1807, was a British Whig politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1830 to 1834. He was a member of the no ...

advised the King to overwhelm opposition to the bill in the House of Lords by creating about 80 new pro-Reform peers. William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

originally balked at the proposal, which effectively threatened the opposition of the House of Lords, but at length relented.

Before the new peers were created, however, the Lords who opposed the bill admitted defeat and abstained from the vote, allowing the passage of the bill. The crisis damaged the political influence of the House of Lords but did not altogether end it. A vital reform was effected by the Lords themselves in 1868, when they changed their standing orders to abolish proxy voting, preventing Lords from voting without taking the trouble to attend. Over the course of the century the powers of the upper house were further reduced stepwise, culminating in the 20th century with the Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

; the Commons gradually became the stronger House of Parliament.

20th century

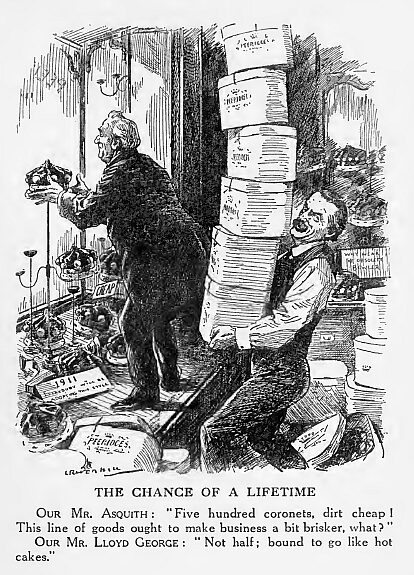

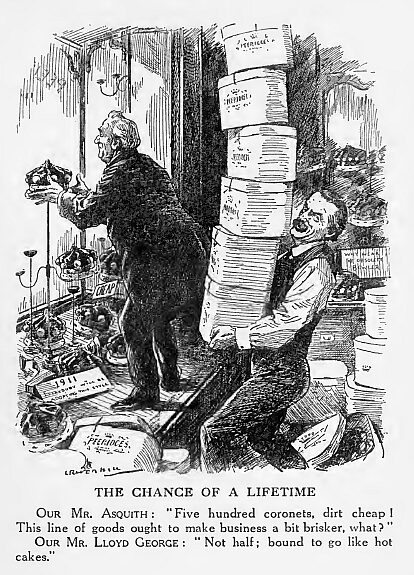

The status of the House of Lords returned to the forefront of debate after the election of a Liberal Government in 1906. In 1909 the

The status of the House of Lords returned to the forefront of debate after the election of a Liberal Government in 1906. In 1909 the Chancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the Exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and head of His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, the Chancellor is ...

, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, introduced into the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

the "People's Budget

The 1909/1910 People's Budget was a proposal of the Liberal government that introduced unprecedented taxes on the lands and incomes of Britain's wealthy to fund new social welfare programmes. It passed the House of Commons in 1909 but was blo ...

", which proposed a land tax targeting wealthy landowners. The popular measure, however, was defeated in the heavily Conservative House of Lords.

Having made the powers of the House of Lords a primary campaign issue, the Liberals were narrowly re-elected in January 1910. The Liberals had lost most of their support in the Lords, which was routinely rejecting Liberals' bills. Prime Minister H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

then proposed that the powers of the House of Lords be severely curtailed. After a further general election in December 1910, and with a reluctant promise by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

to create sufficient new Liberal peers to overcome the Lords' opposition to the measure if necessary, the Asquith Government secured the passage of a bill to curtail the powers of the House of Lords. The Parliament Act 1911

The Parliament Act 1911 (1 & 2 Geo. 5 c. 13) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is constitutionally important and partly governs the relationship between the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two Houses of Parlia ...

effectively abolished the power of the House of Lords to reject legislation, or to amend it in a way unacceptable to the House of Commons; and most bills could be delayed for no more than three parliamentary sessions or two calendar years. It was not meant to be a permanent solution; more comprehensive reforms were planned. Neither party, however, pursued reforms with much enthusiasm, and the House of Lords remained primarily hereditary. The Parliament Act 1949

The Parliament Act 1949 (12, 13 & 14 Geo. 6 c. 103) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It reduced the power of the House of Lords to delay certain types of legislation – specifically public bills other than money bills &n ...

reduced the delaying power of the House of Lords further to two sessions or one year. In 1958, the predominantly hereditary nature of the House of Lords was changed by the Life Peerages Act 1958

The Life Peerages Act 1958 established the modern standards for the creation of life peers by the Sovereign of the United Kingdom.

Background

This Act was made during the Conservative governments of 1957–1964, when Harold Macmillan was Prime M ...

, which authorised the creation of life baronies, with no numerical limits. The number of life peers then gradually increased, though not at a constant rate.

The Labour Party had, for most of the 20th century, a commitment, based on the party's historic opposition to class privilege, to abolish the House of Lords, or at least expel the hereditary element. In 1968 the Labour Government of Harold Wilson

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from October 1964 to June 1970, and again from March 1974 to April 1976. He ...

attempted to reform the House of Lords by introducing a system under which hereditary peers would be allowed to remain in the House and take part in debate, but would be unable to vote. This plan, however, was defeated in the House of Commons by a coalition of traditionalist Conservatives (such as Enoch Powell

John Enoch Powell, (16 June 1912 – 8 February 1998) was a British politician, classical scholar, author, linguist, soldier, philologist, and poet. He served as a Conservative Member of Parliament (1950–1974) and was Minister of Health (1 ...

), and Labour members who continued to advocate the outright abolition of the Upper House (such as Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

).

When Michael Foot became leader of the Labour Party in 1980, abolition of the House of Lords became a part of the party's agenda; under his successor, Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a British former politician. As a member of the Labour Party, he served as a Member of Parliament from 1970 until 1995, first for Bedwellty and then for Islwyn. He was the Leader of ...

, however, a reformed Upper House was proposed instead. In the meantime, the creation of new hereditary peerages (except for members of the Royal Family) has been arrested, with the exception of three that were created during the administration of Conservative PM Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. S ...

in the 1980s.

Whilst some hereditary peers were at best apathetic, the Labour Party's clear commitments were not lost on Merlin Hanbury-Tracy, 7th Baron Sudeley

Merlin Charles Sainthill Hanbury-Tracy, 7th Baron Sudeley, (17 June 1939 – 5 September 2022) was a British peer, author, and monarchist. In 1941, at the age of two, he succeeded his first cousin once removed, Richard Hanbury-Tracy, 6th Bar ...

, who for decades was considered an expert on the House of Lords. In December 1979 the Conservative Monday Club

The Conservative Monday Club (usually known as the Monday Club) is a British political pressure group, aligned with the Conservative Party, though no longer endorsed by it. It also has links to the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Ulster Unioni ...

published his extensive paper entitled ''Lords Reform – Why tamper with the House of Lords?'' and in July 1980 ''The Monarchist'' carried another article by Sudeley entitled "Why Reform or Abolish the House of Lords?". In 1990 he wrote a further booklet for the Monday Club entitled "The Preservation of the House of Lords".

21st century

In 2019, a seven-month enquiry by Naomi Ellenbogen QC found that one in five staff of the House had experienced bullying or harassment which they did not report for fear of reprisals. This was preceded by several cases, including Liberal Democrat Anthony Lester, Lord Lester of Herne Hill, of Lords using their position to sexually harass or abuse women.Proposed move

On 19 January 2020, it was announced that the House of Lords may be moved from London to a city inNorthern England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

, likely York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, or Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands in England. It is the second-largest city in the United Kingdom with a population of 1.145 million in the city proper, 2.92 million in the West ...

, in the Midlands

The Midlands (also referred to as Central England) are a part of England that broadly correspond to the Kingdom of Mercia of the Early Middle Ages, bordered by Wales, Northern England and Southern England. The Midlands were important in the Ind ...

, in an attempt to "reconnect" the area. It is unclear how the King's Speech would be conducted in the event of a move. The idea was received negatively by many peers.

Lords reform

First admission of women

There were no women sitting in the House of Lords until 1958, when a small number came into the chamber as a result of theLife Peerages Act 1958

The Life Peerages Act 1958 established the modern standards for the creation of life peers by the Sovereign of the United Kingdom.

Background

This Act was made during the Conservative governments of 1957–1964, when Harold Macmillan was Prime M ...

. One of these was Irene Curzon, 2nd Baroness Ravensdale

Mary Irene Curzon, 2nd Baroness Ravensdale, Baroness Ravensdale of Kedleston, (20 January 1896 – 9 February 1966), was an English noblewoman, socialite and philanthropist.

The eldest child of George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston ...

, who had inherited her father's peerage in 1925 and was made a life peer to enable her to sit. After a campaign stretching back in some cases to the 1920s, another twelve women who held hereditary peerages in their own right were admitted with the passage of the Peerage Act 1963

The Peerage Act 1963 (c. 48) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that permits women peeresses and all Scottish hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords and allows newly inherited hereditary peerages to be disclaimed.

Backgro ...

.

New Labour era

The Labour Party included in its 1997 general electionmanifesto

A manifesto is a published declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party or government. A manifesto usually accepts a previously published opinion or public consensus or promotes a ...

a commitment to remove the hereditary peerage from the House of Lords. Their subsequent election victory in 1997 under Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

led to the denouement of the traditional House of Lords. The Labour government introduced legislation to expel all hereditary peers from the Upper House as a first step in Lords reform. As a part of a compromise, however, it agreed to permit 92 hereditary peers to remain until the reforms were complete. Thus, all but 92 hereditary peers were expelled under the House of Lords Act 1999 (see below for its provisions), making the House of Lords predominantly an appointed house.

Since 1999, however, no further reform has taken place. The Wakeham Commission {{Use dmy dates, date=April 2022

''A House for the Future'', known as the Wakeham Report, published in 2000, was the report of a Royal Commission headed by Lord Wakeham, concerning reform of the House of Lords.

Recommendations of the report

In it ...

proposed introducing a 20% elected element to the Lords, but this plan was widely criticised. A parliamentary Joint Committee

A joint committee of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is a joint committee of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, formed to examine a particular issue, whose members are drawn from both the House of Commons and House of Lords. It is a type ...

was established in 2001 to resolve the issue, but it reached no conclusion and instead gave Parliament seven options to choose from (fully appointed, 20% elected, 40% elected, 50% elected, 60% elected, 80% elected, and fully elected). In a confusing series of votes in February 2003, all of these options were defeated, although the 80% elected option fell by just three votes in the Commons. Socialist MPs favouring outright abolition voted against all the options.

In 2005, a cross-party group of senior MPs (Kenneth Clarke

Kenneth Harry Clarke, Baron Clarke of Nottingham, (born 2 July 1940), often known as Ken Clarke, is a British politician who served as Home Secretary from 1992 to 1993 and Chancellor of the Exchequer from 1993 to 1997 as well as serving as de ...

, Paul Tyler

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

*Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

* Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

, Tony Wright, George Young, and Robin Cook

Robert Finlayson "Robin" Cook (28 February 19466 August 2005) was a British Labour politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1974 until his death in 2005 and served in the Cabinet as Foreign Secretary from 1997 until 2001 wh ...

) published a report proposing that 70% of members of the House of Lords should be elected – each member for a single long term – by the single transferable vote

Single transferable vote (STV) is a multi-winner electoral system in which voters cast a single vote in the form of a ranked-choice ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vote may be transferred according to alternate p ...

system. Most of the remainder were to be appointed by a Commission to ensure a mix of "skills, knowledge and experience". This proposal was also not implemented. A cross-party campaign initiative called "Elect the Lords

Certain governments in the United Kingdom have, for more than a century, attempted to find a way to reform the House of Lords, the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. This process was started by the Parliament Act 1911 introdu ...

" was set up to make the case for a predominantly elected Upper Chamber in the run up to the 2005 general election.

At the 2005 election, the Labour Party proposed further reform of the Lords, but without specific details. The Conservative Party, which had, prior to 1997, opposed any tampering with the House of Lords, favoured an 80% elected Lords, while the Liberal Democrats called for a fully elected Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. During 2006, a cross-party committee discussed Lords reform, with the aim of reaching a consensus: its findings were published in early 2007.

On 7 March 2007, members of the House of Commons voted ten times on a variety of alternative compositions for the Upper Chamber. Outright abolition, a wholly appointed, a 20% elected, a 40% elected, a 50% elected, and a 60% elected House of Lords were all defeated in turn. Finally, the vote for an 80% elected Lords was won by 305 votes to 267, and the vote for a wholly elected Lords was won by an even greater margin, 337 to 224. Significantly, this last vote represented an overall majority of MPs.

Furthermore, examination of the names of MPs voting at each division shows that, of the 305 who voted for the 80% elected option, 211 went on to vote for the 100% elected option. Given that this vote took place after the vote on 80% – whose result was already known when the vote on 100% took place – this showed a clear preference for a fully elected Upper House among those who voted for the only other option that passed. But this was nevertheless only an indicative vote, and many political and legislative hurdles remained to be overcome for supporters of an elected House of Lords. Lords, soon after, rejected this proposal and voted for an entirely appointed House of Lords.

In July 2008, Jack Straw

John Whitaker Straw (born 3 August 1946) is a British politician who served in the Cabinet from 1997 to 2010 under the Labour governments of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. He held two of the traditional Great Offices of State, as Home Secretary ...

, the Secretary of State for Justice

The secretary of state for justice, also referred to as the justice secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Ministry of Justice. The incumbent is a member of the Cabinet of the Un ...

and Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. The ...

, introduced a white paper

A white paper is a report or guide that informs readers concisely about a complex issue and presents the issuing body's philosophy on the matter. It is meant to help readers understand an issue, solve a problem, or make a decision. A white paper ...

to the House of Commons proposing to replace the House of Lords with an 80–100% elected chamber, with one third being elected at each general election, to serve a term of approximately 12–15 years. The white paper stated that, as the peerage would be totally separated from membership of the Upper House, the name "House of Lords" would no longer be appropriate. It went on to explain that there was cross-party consensus for the Chamber to be re-titled the "Senate of the United Kingdom"; however, to ensure the debate remained on the role of the Upper House rather than its title, the white paper was neutral on the title issue.

On 30 November 2009, a ''Code of Conduct for Members of the House of Lords'' was agreed by them. Certain amendments were agreed by them on 30 March 2010 and on 12 June 2014.

The scandal over expenses in the Commons was at its highest pitch only six months before, and the Labourite leadership under Janet Royall, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon

Janet Anne Royall, Baroness Royall of Blaisdon, (born 20 August 1955), is a British Labour Co-operative Party politician. She was Leader of the House of Lords and Lord President of the Council. She is the principal of Somerville College, Oxford. ...

determined that something sympathetic should be done.

Meg Russell stated in an article, "Is the House of Lords already reformed?", three essential features of a legitimate House of Lords:

The first was that it must have adequate powers over legislation to make the government think twice before making a decision. The House of Lords, she argued, had enough power to make it relevant. (In his first year, Tony Blair was defeated 38 times in the Lords—but that was before the major reform with the House of Lords Act 1999.)

Second, as to the composition of the Lords, Meg Russell suggested that the composition must be distinct from the Commons, otherwise it would render the Lords useless.

Third was the perceived legitimacy of the Lords. She stated, "In general legitimacy comes with election."

2010–present

The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreed, after the 2010 general election, to outline clearly a provision for a wholly or mainly elected second chamber, elected by proportional representation. These proposals sparked a debate on 29 June 2010. As an interim measure, appointment of new peers would reflect the shares of the vote secured by the political parties in the last general election.

Detailed proposals for Lords reform, including a draft House of Lords Reform Bill, were published on 17 May 2011. These included a 300-member hybrid house, of whom 80% would be elected. A further 20% would be appointed, and reserve space would be included for some Church of England archbishops and bishops. Under the proposals, members would also serve single non-renewable terms of 15 years. Former MPs would be allowed to stand for election to the Upper House, but members of the Upper House would not be immediately allowed to become MPs.

The details of the proposal were:

* The upper chamber shall continue to be known as the House of Lords for legislative purposes.

* The reformed House of Lords should have 300 members of whom 240 are "Elected Members" and 60 appointed "Independent Members". Up to 12 Church of England archbishops and bishops may sit in the house as ''ex officio'' "Lords Spiritual".

* Elected Members will serve a single, non-renewable term of 15 years.

* Elections to the reformed Lords should take place at the same time as elections to the House of Commons.

* Elected Members should be elected using the

The Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreed, after the 2010 general election, to outline clearly a provision for a wholly or mainly elected second chamber, elected by proportional representation. These proposals sparked a debate on 29 June 2010. As an interim measure, appointment of new peers would reflect the shares of the vote secured by the political parties in the last general election.

Detailed proposals for Lords reform, including a draft House of Lords Reform Bill, were published on 17 May 2011. These included a 300-member hybrid house, of whom 80% would be elected. A further 20% would be appointed, and reserve space would be included for some Church of England archbishops and bishops. Under the proposals, members would also serve single non-renewable terms of 15 years. Former MPs would be allowed to stand for election to the Upper House, but members of the Upper House would not be immediately allowed to become MPs.

The details of the proposal were:

* The upper chamber shall continue to be known as the House of Lords for legislative purposes.

* The reformed House of Lords should have 300 members of whom 240 are "Elected Members" and 60 appointed "Independent Members". Up to 12 Church of England archbishops and bishops may sit in the house as ''ex officio'' "Lords Spiritual".

* Elected Members will serve a single, non-renewable term of 15 years.

* Elections to the reformed Lords should take place at the same time as elections to the House of Commons.

* Elected Members should be elected using the Single Transferable Vote

Single transferable vote (STV) is a multi-winner electoral system in which voters cast a single vote in the form of a ranked-choice ballot. Voters have the option to rank candidates, and their vote may be transferred according to alternate p ...

system of proportional representation.

* Twenty Independent Members (a third) shall take their seats within the reformed house at the same time as elected members do so, and for the same 15-year term.

* Independent Members will be appointed by the King after being proposed by the Prime Minister acting on advice of an Appointments Commission.

* There will no longer be a link between the peerage system and membership of the upper house.

* The current powers of the House of Lords would not change and the House of Commons shall retain its status as the primary House of Parliament.

The proposals were considered by a Joint Committee on House of Lords Reform made up of both MPs and Peers, which issued its final report on 23 April 2012, making the following suggestions:

* The reformed House of Lords should have 450 members.

* Party groupings, including the Crossbenchers, should choose which of their members are retained in the transition period, with the percentage of members allotted to each group based on their share of the peers with high attendance during a given period.

* Up to 12 Lords Spiritual should be retained in a reformed House of Lords.

Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg

Sir Nicholas William Peter Clegg (born 7 January 1967) is a British media executive and former Deputy Prime Minister of the United Kingdom who has been president for global affairs at Meta Platforms since 2022, having previously been vicepr ...

introduced the House of Lords Reform Bill 2012

The House of Lords Reform Bill 2012 was a proposed Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom introduced to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons in June 2012 by Nick Clegg. Among other reforms, the bill would have made the ...

on 27 June 2012 which built on proposals published on 17 May 2011. However, this Bill was abandoned by the Government on 6 August 2012, following opposition from within the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

.

=House of Lords Reform Act 2014

= Aprivate member's bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in whi ...

to introduce some reforms was introduced by Dan Byles

Daniel Alan Byles (born 24 June 1974) is a former British politician, who was the Member of Parliament (MP) for North Warwickshire from 2010 to 2015.

Background

Byles was born in Hastings, East Sussex, but spent his early childhood as an exp ...

in 2013. The House of Lords Reform Act 2014

The House of Lords Reform Act 2014 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act was a private member's bill. It received Royal Assent on 14 May 2014. The Act allows members of the House of Lords to retire or resign – actions previousl ...

received Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

in 2014. Under the new law:

*All peers can retire or resign from the chamber (prior to this only hereditary peers could disclaim their peerages).

*Peers can be disqualified for non-attendance.

*Peers can be removed for receiving prison sentences of a year or more.

=House of Lords (Expulsion and Suspension) Act 2015

= TheHouse of Lords (Expulsion and Suspension) Act 2015

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in ...

authorised the House to expel or suspend members.

=Lords Spiritual (Women) Act 2015

= This Act made provision to preferentially admit female bishops of the Church of England to the Lords Spiritual over male ones in the 10 years following its commencement (2015 to 2025). This came as a consequence of the Church of England deciding in 2014 to begin to ordain women as bishops. In 2015,Rachel Treweek

Rachel Treweek (née Montgomery; born 4 February 1963 at Broxbourne, Hertfordshire) is an Anglican bishop who sits in the House of Lords as a Lord Spiritual.

Since June 2015, she has served as Bishop of Gloucester, the first female diocesan bi ...

, Bishop of Gloucester

The Bishop of Gloucester is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Gloucester in the Province of Canterbury.

The diocese covers the County of Gloucestershire and part of the County of Worcestershire. The see's centre of governan ...

, became the first woman to sit as a Lord Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual are the bishops of the Church of England who serve in the House of Lords of the United Kingdom. 26 out of the 42 diocesan bishops and archbishops of the Church of England serve as Lords Spiritual (not counting retired archbi ...

in the House of Lords due to the Act. As of 2022, five women bishops sit as Lords Spiritual, four of them having been accelerated due to this Act.

Size

The size of the House of Lords has varied greatly throughout its history. The English House of Lords—then comprising 168 members—was joined at Westminster by 16 Scottish peers to represent the peerage of Scotland—a total of 184 nobles—in 1707's firstParliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in May 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and the Parliament of Scotland. The Acts ratified the treaty of Union which created a new unified Kingdo ...

. A further 28 Irish members to represent the peerage of Ireland were added in 1801 to the first Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprema ...

. From about 220 peers in the eighteenth century, the house saw continued expansion. From about 850 peers in 1951/52, the numbers rose further with more life peers

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the peerage whose titles cannot be inherited, in contrast to hereditary peers. In modern times, life peerages, always created at the rank of baron, are created under the Life Peerages A ...

after the Life Peerages Act 1958 and the inclusion of all Scottish peers and the first female peers in the Peerage Act 1963

The Peerage Act 1963 (c. 48) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that permits women peeresses and all Scottish hereditary peers to sit in the House of Lords and allows newly inherited hereditary peerages to be disclaimed.

Backgro ...

. It reached a record size of 1,330 in October 1999, immediately before the major Lords reform (House of Lords Act 1999

The House of Lords Act 1999 (c. 34) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed the House of Lords, one of the chambers of Parliament. The Act was given Royal Assent on 11 November 1999. For centuries, the House of Lords ...

) reduced it to 669, mostly life peers, by March 2000.

The chamber's membership again expanded in the following decades, increasing to above eight hundred active members in 2014 and prompting further reforms in the House of Lords Reform Act that year.

In April 2011, a cross-party group of former leading politicians, including many senior members of the House of Lords, called on the Prime Minister

The chamber's membership again expanded in the following decades, increasing to above eight hundred active members in 2014 and prompting further reforms in the House of Lords Reform Act that year.

In April 2011, a cross-party group of former leading politicians, including many senior members of the House of Lords, called on the Prime Minister David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron (born 9 October 1966) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2005 to 2016. He previously served as Leader o ...

to stop creating new peers. He had created 117 new peers between entering office in May 2010 and leaving in July 2016, a faster rate of elevation than any PM in British history; at the same time his government had tried (in vain) to reduce the House of Commons by 50, from 650 to 600 MPs.

In August 2014, despite there being a seating capacity for only around 230 to 400 on the benches in the Lords chamber, the House had 774 active members (plus 54 who were not entitled to attend or vote, having been suspended or granted leave of absence). This made the House of Lords the largest parliamentary chamber in any democracy. In August 2014, former Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

Betty Boothroyd

Betty Boothroyd, Baroness Boothroyd (born 8 October 1929) is a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for West Bromwich and West Bromwich West from 1973 to 2000. From 1992 to 2000, she served as Speaker of the House of ...

requested that "older peers should retire gracefully" to ease the overcrowding in the House of Lords. She also criticised successive prime ministers for filling the second chamber with "lobby fodder" in an attempt to help their policies become law. She made her remarks days before a new batch of peers were due to be created and several months after the passage of the House of Lords Reform Act 2014

The House of Lords Reform Act 2014 is an Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act was a private member's bill. It received Royal Assent on 14 May 2014. The Act allows members of the House of Lords to retire or resign – actions previousl ...

, enabling life peers to retire or resign their seats in the House, which had previously only been possible for hereditary peers and bishops.

In August 2015, when 45 more peers were created in the Dissolution Honours

Crown Honours Lists are lists of honours conferred upon citizens of the Commonwealth realms. The awards are presented by or in the name of the reigning monarch, currently King Charles III, or his vice-regal representative.

New Year Honours

Ho ...

, the total number of eligible members of the Lords increased to 826. In a report entitled "Does size matter?" the BBC said: "Increasingly, yes. Critics argue the House of Lords is the second largest legislature after the Chinese National People's Congress and dwarfs upper houses in other bicameral democracies such as the United States (100 senators), France (348 senators), Australia (76 senators), Canada (105 appointed senators) and India (250 members). The Lords is also larger than the Supreme People's Assembly

The Supreme People's Assembly (SPA; ) is the unicameral legislature of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), commonly known as North Korea. It consists of one deputy from each of the DPRK's 687 constituencies, elected to five-year ...

of North Korea (687 members). ... Peers grumble that there is not enough room to accommodate all of their colleagues in the Chamber, where there are only about 400 seats, and say they are constantly jostling for space – particularly during high-profile sittings", but added, "On the other hand, defenders of the Lords say that it does a vital job scrutinising legislation, a lot of which has come its way from the Commons in recent years".

In late 2016, a Lord Speaker's committee was formed to examine the issue of overcrowding, with fears membership could swell to above 1,000, and in October 2017 the committee presented its findings. In December 2017, the Lords debated and broadly approved its report, which proposed a cap on membership at 600 peers, with a fifteen-year term limit for new peers and a "two-out, one-in" limit on new appointments. By October 2018, the Lord Speaker's committee commended the reduction in peers' numbers, noting that the rate of departures had been greater than expected, with the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee

The Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee, formerly the Public Administration Select Committee, is a select committee appointed by the British House of Commons to examine the reports of the Parliamentary and Health Se ...

approving the progress achieved without legislation.

By April 2019, with the retirement of nearly one hundred peers since the passage of the House of Lords Reform Act 2014, the number of active peers had been reduced to a total of 782, of whom 665 were life peers. This total, however, remains greater than the membership of 669 peers in March 2000, after implementation of the House of Lords Act 1999

The House of Lords Act 1999 (c. 34) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed the House of Lords, one of the chambers of Parliament. The Act was given Royal Assent on 11 November 1999. For centuries, the House of Lords ...

removed the bulk of the hereditary peers from their seats; it is well above the proposed 600-member cap, and is still larger than the House of Commons's 650 members.

Functions

Legislative functions

Legislation, with the exception ofmoney bills

In the Westminster system (and, colloquially, in the United States), a money bill or supply bill is a bill that solely concerns taxation or government spending (also known as appropriation of money), as opposed to changes in public law.

Co ...

, may be introduced in either House.

The House of Lords debates legislation, and has power to amend or reject bills. However, the power of the Lords to reject a bill passed by the House of Commons is severely restricted by the Parliament Acts. Under those Acts, certain types of bills may be presented for Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

without the consent of the House of Lords (i.e. the Commons can override the Lords' veto). The House of Lords cannot delay a money bill (a bill that, in the view of the Speaker of the House of Commons, solely concerns national taxation or public funds) for more than one month.

Other public bills cannot be delayed by the House of Lords for more than two parliamentary sessions, or one calendar year. These provisions, however, only apply to public bills that originate in the House of Commons, and cannot have the effect of extending a parliamentary term beyond five years. A further restriction is a constitutional convention known as the Salisbury Convention

The Salisbury Convention (officially called the Salisbury Doctrine, the Salisbury-Addison Convention or the Salisbury/Addison Convention) is a constitutional convention (political custom), constitutional convention in the United Kingdom under whic ...

, which means that the House of Lords does not oppose legislation promised in the Government's election manifesto.

By a custom that prevailed even before the Parliament Acts, the House of Lords is further restrained insofar as financial bills are concerned. The House of Lords may neither originate a bill concerning taxation or Supply (supply of treasury or exchequer funds), nor amend a bill so as to insert a taxation or Supply-related provision. (The House of Commons, however, often waives its privileges and allows the Upper House to make amendments with financial implications.) Moreover, the Upper House may not amend any Supply Bill. The House of Lords formerly maintained the absolute power to reject a bill relating to revenue or Supply, but this power was curtailed by the Parliament Acts.

Relationship with the government

The House of Lords does not control the term of the prime minister or of the government. Only the lower house may force the prime minister to resign or call elections by passing a motion of no-confidence or by withdrawing supply. Thus, the House of Lords' oversight of the government is limited. Most Cabinet ministers are from the House of Commons rather than the House of Lords. In particular, all prime ministers since 1902 have been members of the lower house. ( Alec Douglas-Home, who became prime minister in 1963 whilst still an earl, disclaimed his peerage and was elected to the Commons soon after his term began.) In recent history, it has been very rare for major cabinet positions (except Lord Chancellor andLeader of the House of Lords

The leader of the House of Lords is a member of the Cabinet of the United Kingdom who is responsible for arranging government business in the House of Lords. The post is also the leader of the majority party in the House of Lords who acts as ...

) to have been filled by peers.

Exceptions include Peter Carington, 6th Lord Carrington, who was the Secretary of State for Defence

The secretary of state for defence, also referred to as the defence secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the business of the Ministry of Defence. The incumbent is a membe ...

from 1970 to 1974, Secretary of State for Energy

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a wh ...

briefly for two months in early 1974 and Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

between 1979 and 1982, Arthur Cockfield, Lord Cockfield, who served as Secretary of State for Trade

The secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. The incumbent is a memb ...

and President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

, David Young, Lord Young of Graffham (Minister without Portfolio

A minister without portfolio is either a government minister with no specific responsibilities or a minister who does not head a particular ministry. The sinecure is particularly common in countries ruled by coalition governments and a cabinet w ...

, then Secretary of State for Employment

The Secretary of State for Employment was a position in the Cabinet of the United Kingdom. In 1995 it was merged with Secretary of State for Education to make the Secretary of State for Education and Employment. In 2001 the employment functions w ...

and then Secretary of State for Trade and Industry

The secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. The incumbent is a memb ...

and President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

from 1984 to 1989), Valerie Amos, Baroness Amos

Valerie Ann Amos, Baroness Amos, (born 13 March 1954) is a British Labour Party politician and diplomat who served as the eighth UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator. Before her appointment to ...

, who served as Secretary of State for International Development

The minister of state for development and Africa, formerly the minister of state for development and the secretary of state for international development, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom.

The off ...

, Andrew Adonis, Lord Adonis, who served as Secretary of State for Transport

The Secretary of State for Transport, also referred to as the transport secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the policies of the Department for Transport. The incumbent i ...

and Peter Mandelson

Peter Benjamin Mandelson, Baron Mandelson (born 21 October 1953) is a British Labour Party politician who served as First Secretary of State from 2009 to 2010. He was President of the Board of Trade in 1998 and from 2008 to 2010. He is the ...

, who served as First Secretary of State

The First Secretary of State is an office that is sometimes held by a minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom. The office indicates seniority, including over all other Secretaries of State. The office is not always in use, ...

, Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills

The secretary of state for business, energy and industrial strategy, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with responsibility for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. The incumbent is a memb ...

and President of the Board of Trade

The president of the Board of Trade is head of the Board of Trade. This is a committee of the His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, Privy Council of the United Kingdom, first established as a temporary committee of inquiry in the 17th centu ...

. George Robertson, Lord Robertson of Port Ellen was briefly a peer whilst serving as Secretary of State for Defence

The secretary of state for defence, also referred to as the defence secretary, is a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, with overall responsibility for the business of the Ministry of Defence. The incumbent is a membe ...

before resigning to take up the post of Secretary General of NATO

The secretary general of NATO is the chief civil servant of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The officeholder is an international diplomat responsible for coordinating the workings of the alliance, leading NATO's international staff ...

. From 1999 to 2010 the Attorney General for England and Wales

His Majesty's Attorney General for England and Wales is one of the law officers of the Crown and the principal legal adviser to sovereign and Government in affairs pertaining to England and Wales. The attorney general maintains the Attorney ...

was a member of the House of Lords; the most recent was Patricia Scotland

Patricia Janet Scotland, Baroness Scotland of Asthal, (born 19 August 1955), is a British diplomat, barrister and politician, serving as the sixth secretary-general of the Commonwealth of Nations. She was elected at the 2015 Commonwealth Head ...

.

The House of Lords remains a source for junior ministers and members of government. Like the House of Commons, the Lords also has a Government Chief Whip as well as several Junior Whips. Where a government department is not represented by a minister in the Lords or one is not available, government whips will act as spokesmen for them.

Former judicial role

Historically, the House of Lords held several judicial functions. Most notably, until 2009 the House of Lords served as thecourt of last resort

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

for most instances of UK law. Since 1 October 2009 this role is now held by the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom.

The Lords' judicial functions originated from the ancient role of the Curia Regis as a body that addressed the petitions of the King's subjects. The functions were exercised not by the whole House, but by a committee of "Law Lords". The bulk of the House's judicial business was conducted by the twelve Lords of Appeal in Ordinary

Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, commonly known as Law Lords, were judges appointed under the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876 to the British House of Lords, as a committee of the House, effectively to exercise the judicial functions of the House of ...

, who were specifically appointed for this purpose under the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876

The Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876 ( 39 & 40 Vict c 59) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that altered the judicial functions of the House of Lords by allowing senior judges to sit in the House of Lords as life peers, known as ...

.

The judicial functions could also be exercised by Lords of Appeal (other members of the House who happened to have held high judicial office). No Lord of Appeal in Ordinary or Lord of Appeal could sit judicially beyond the age of seventy-five. The judicial business of the Lords was supervised by the Senior Lord of Appeal in Ordinary and their deputy, the Second Senior Lord of Appeal in Ordinary.

The jurisdiction of the House of Lords extended, in civil and in criminal cases, to appeals from the courts of England and Wales, and of Northern Ireland. From Scotland, appeals were possible only in civil cases; Scotland's High Court of Justiciary

The High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court in Scotland. The High Court is both a trial court and a court of appeal. As a trial court, the High Court sits on circuit at Parliament House or in the adjacent former Sheriff Cou ...

is the highest court in criminal matters. The House of Lords was not the United Kingdom's only court of last resort; in some cases, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is the highest court of appeal for the Crown Dependencies, the British Overseas Territories, some Commonwealth countries and a few institutions in the United Kingdom. Established on 14 Augus ...

performs such a function. The jurisdiction of the Privy Council in the United Kingdom, however, is relatively restricted; it encompasses appeals from ecclesiastical

{{Short pages monitor