Horace Havemeyer on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading

The ''Epodes'' belong to

The ''Epodes'' belong to

The reception of Horace's work has varied from one epoch to another and varied markedly even in his own lifetime. ''Odes'' 1–3 were not well received when first 'published' in Rome, yet Augustus later commissioned a ceremonial ode for the Centennial Games in 17 BC and also encouraged the publication of ''Odes'' 4, after which Horace's reputation as Rome's premier lyricist was assured. His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ode-writing became highly fashionable in England and a large number of aspiring poets imitated Horace both in English and in Latin.

In a verse epistle to Augustus (Epistle 2.1), in 12 BC, Horace argued for classic status to be awarded to contemporary poets, including Virgil and apparently himself. In the final poem of his third book of Odes he claimed to have created for himself a monument more durable than bronze ("Exegi monumentum aere perennius", ''

The reception of Horace's work has varied from one epoch to another and varied markedly even in his own lifetime. ''Odes'' 1–3 were not well received when first 'published' in Rome, yet Augustus later commissioned a ceremonial ode for the Centennial Games in 17 BC and also encouraged the publication of ''Odes'' 4, after which Horace's reputation as Rome's premier lyricist was assured. His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ode-writing became highly fashionable in England and a large number of aspiring poets imitated Horace both in English and in Latin.

In a verse epistle to Augustus (Epistle 2.1), in 12 BC, Horace argued for classic status to be awarded to contemporary poets, including Virgil and apparently himself. In the final poem of his third book of Odes he claimed to have created for himself a monument more durable than bronze ("Exegi monumentum aere perennius", ''

Classical texts almost ceased being copied in the period between the mid sixth century and the Carolingian revival. Horace's work probably survived in just two or three books imported into northern Europe from Italy. These became the ancestors of six extant manuscripts dated to the ninth century. Two of those six manuscripts are French in origin, one was produced in

Classical texts almost ceased being copied in the period between the mid sixth century and the Carolingian revival. Horace's work probably survived in just two or three books imported into northern Europe from Italy. These became the ancestors of six extant manuscripts dated to the ninth century. Two of those six manuscripts are French in origin, one was produced in

Both

Both

''Sylvæ; or, The second Part of Poetical Miscellanies''

(London: Jacob Tonson, 1685) Included adaptations of three of the ''Odes'', and one Epode. * Philip Francis, ''The Odes, Epodes, and Carmen Seculare'' ''of Horace'' (Dublin, 1742; London, 1743) *——— ''The Satires, Epistles, and Art of Poetry'' ''of Horace'' (1746)

''Verses and Translations''

(1860; rev. 1862) Included versions of ten of the ''Odes.'' *

''The Odes of Horace, Translated Into English Verse, with a Life and Notes''

(Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866) *

opera

', recensuerunt O. Keller et A. Holder, 2 voll., Lipsiae in aedibus B. G. Teubneri, 1864–9.

Q. Horati Flacci opera

(critical edition of all Horace's poems), edited by O. Keller & A. Holder, published by B. G. Teubner, 1878.

Common sayings from Horace

at

Carmina Horatiana

All ''Carmina'' of Horace in Latin recited by Thomas Bervoets.

Selected Poems of Horace

Works by Horace at Perseus Digital Library

Biography and chronology

Horace's works

text, concordances and frequency list

Translations of several odes in the original meters (with accompaniment).

A discussion and comparison of three different contemporary translations of Horace's ''Odes''

* academia.edu: Tossing Augustus out of Horace's Ars Poetica

Horati opera, Acronis et Porphyrionis commentarii, varia lectio etc. (latine)

{{Authority control 65 BC births 8 BC deaths 1st-century BC Romans 1st-century BC writers Ancient Roman soldiers Golden Age Latin writers People from Venosa Roman-era poets Roman-era satirists Iambic poets Ancient literary critics Roman-era Epicurean philosophers Flaccus, Quintus Roman philhellenes Simple living advocates

Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

lyric poet

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

during the time of Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

(also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian

Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (; 35 – 100 AD) was a Roman educator and rhetorician from Hispania, widely referred to in medieval schools of rhetoric and in Renaissance writing. In English translation, he is usually referred to as Quintilia ...

regarded his ''Odes

Odes may refer to:

*The plural of ode, a type of poem

*Odes (Horace), ''Odes'' (Horace), a collection of poems by the Roman author Horace, circa 23 BCE

*Odes of Solomon, a pseudepigraphic book of the Bible

*Book of Odes (Bible), a Deuterocanonic ...

'' as just about the only Latin lyrics worth reading: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words."Quintilian 10.1.96. The only other lyrical poet Quintilian thought comparable with Horace was the now obscure poet/metrical theorist, Caesius Bassus

Gaius Caesius Bassus (d. AD 79) was a Roman lyric poet who lived in the reign of Nero.

He was the intimate friend of Persius, who dedicated his sixth satire to him, and whose works he edited (''Schol. on Persius'', vi. I). He had a great reputa ...

(R. Tarrant, ''Ancient Receptions of Horace'', 280)

Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (''Satires

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

'' and ''Epistles

An epistle (; el, ἐπιστολή, ''epistolē,'' "letter") is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part ...

'') and caustic iambic poetry

Iambus or iambic poetry was a genre of ancient Greek poetry that included but was not restricted to the iambic meter and whose origins modern scholars have traced to the cults of Demeter and Dionysus. The genre featured insulting and obscene lan ...

('' Epodes''). The hexameters are amusing yet serious works, friendly in tone, leading the ancient satirist Persius

Aulus Persius Flaccus (; 4 December 3424 November 62 AD) was a Ancient Rome, Roman poet and satirist of Etruscan civilization, Etruscan origin. In his works, poems and satires, he shows a Stoicism, Stoic wisdom and a strong criticism for what he ...

to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings".Translated from Persius' own 'Satires' 1.116–17: "omne vafer vitium ridenti Flaccus amico / tangit et admissus circum praecordia ludit."

His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from a republic to an empire. An officer in the republican army defeated at the Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Wars of the Second Triumvirate between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC, at P ...

in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas

Gaius Cilnius Maecenas ( – 8 BC) was a friend and political advisor to Octavian (who later reigned as emperor Augustus). He was also an important patron for the new generation of Augustan poets, including both Horace and Virgil. During the rei ...

, and became a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep")J. Michie, ''The Odes of Horace'', 14 but for others he was, in John Dryden

''

John Dryden (; – ) was an English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who in 1668 was appointed England's first Poet Laureate.

He is seen as dominating the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the per ...

's phrase, "a well-mannered court slave".Quoted by N. Rudd from John Dryden's ''Discourse Concerning the Original and Progress of Satire'', excerpted from W.P.Ker's edition of Dryden's essays, Oxford 1926, vol. 2, pp. 86–87

Life

Horace can be regarded as the world's first autobiographer. In his writings, he tells us far more about himself, his character, his development, and his way of life, than any other great poet of antiquity. Some of the biographical material contained in his work can be supplemented from the short but valuable "Life of Horace" bySuetonius

Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (), commonly referred to as Suetonius ( ; c. AD 69 – after AD 122), was a Roman historian who wrote during the early Imperial era of the Roman Empire.

His most important surviving work is a set of biographies ...

(in his ''Lives of the Poets'').

Childhood

He was born on 8 December 65 BCThe year is given in ''Odes'' 3.21.1 ( "Consule Manlio"), the month in ''Epistles'' 1.20.27, the day in Suetonius' biography ''Vita'' (R. Nisbet, ''Horace: life and chronology'', 7) in the Samnite south ofItaly

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. His home town, Venusia

Venosa ( Lucano: ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Potenza, in the southern Italian region of Basilicata, in the Vulture area. It is bounded by the comuni of Barile, Ginestra, Lavello, Maschito, Montemilone, Palazzo San Gervasio, Ra ...

, lay on a trade route in the border region between Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

and Lucania

Lucania was a historical region of Southern Italy. It was the land of the Lucani, an Oscan people. It extended from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Gulf of Taranto.

It bordered with Samnium and Campania in the north, Apulia in the east, and Brutti ...

(Basilicata

it, Lucano (man) it, Lucana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

...

). Various Italic dialects were spoken in the area and this perhaps enriched his feeling for language. He could have been familiar with Greek words even as a young boy and later he poked fun at the jargon of mixed Greek and Oscan spoken in neighbouring Canusium

Canosa di Puglia, generally known simply as Canosa ( nap, label= Canosino, Canaus), is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Barletta-Andria-Trani, Apulia, southern Italy. It is located between Bari and Foggia, on the northwestern edge of the ...

. One of the works he probably studied in school was the ''Odyssia'' of Livius Andronicus

Lucius Livius Andronicus (; el, Λούκιος Λίβιος Ανδρόνικος; c. 284 – c. 204 BC) was a Greco-Roman dramatist and epic poet of the Old Latin period during the Roman Republic. He began as an educator in the service of a n ...

, taught by teachers like the 'Orbilius

Lucius Orbilius Pupillus (114 BC – c. 14 BC) was a Latin Philologist, grammarian of the 1st century BC, who taught at school, first at Benevento and then at Rome, where the poet Horace was one of his pupils. Horace (''Epistles'', ii) criticizes ...

' mentioned in one of his poems. Army veterans could have been settled there at the expense of local families uprooted by Rome as punishment for their part in the Social War (91–88 BC) Social War may refer to:

* Social War (357–355 BC), or the War of the Allies, fought between the Second Athenian Empire and the allies of Chios, Rhodes, and Cos as well as Byzantium

* Social War (220–217 BC), fought among the southern Greek sta ...

. Such state-sponsored migration must have added still more linguistic variety to the area. According to a local tradition reported by Horace, a colony of Romans or Latins had been installed in Venusia after the Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they for ...

had been driven out early in the third century. In that case, young Horace could have felt himself to be a Roman though there are also indications that he regarded himself as a Samnite or Sabellus

Sabellians is a collective ethnonym for a group of Italic peoples or tribes inhabiting central and southern Italy at the time of the rise of Rome. The name was first applied by Niebuhr and encompassed the Sabines, Marsi, Marrucini and Vestini ...

by birth. Italians in modern and ancient times have always been devoted to their home towns, even after success in the wider world, and Horace was no different. Images of his childhood setting and references to it are found throughout his poems.

Horace's father was probably a Venutian taken captive by Romans in the Social War, or possibly he was descended from a Sabine

The Sabines (; lat, Sabini; it, Sabini, all exonyms) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines divide ...

captured in the Samnite Wars

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars (343–341 BC, 326–304 BC, and 298–290 BC) were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe.

...

. Either way, he was a slave for at least part of his life. He was evidently a man of strong abilities however and managed to gain his freedom and improve his social position. Thus Horace claimed to be the free-born son of a prosperous 'coactor'.V. Kiernan, ''Horace: Poetics and Politics'', 24 The term 'coactor' could denote various roles, such as tax collector, but its use by Horace was explained by scholia

Scholia (singular scholium or scholion, from grc, σχόλιον, "comment, interpretation") are grammatical, critical, or explanatory comments – original or copied from prior commentaries – which are inserted in the margin of th ...

as a reference to 'coactor argentareus' i.e. an auctioneer with some of the functions of a banker, paying the seller out of his own funds and later recovering the sum with interest from the buyer.

The father spent a small fortune on his son's education, eventually accompanying him to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to oversee his schooling and moral development. The poet later paid tribute to him in a poem''Satires'' 1.6 that one modern scholar considers the best memorial by any son to his father."No son ever set a finer monument to his father than Horace did in the sixth satire of Book I...Horace's description of his father is warm-hearted but free from sentimentality or exaggeration. We see before us one of the common people, a hard-working, open-minded, and thoroughly honest man of simple habits and strict convictions, representing some of the best qualities that at the end of the Republic could still be found in the unsophisticated society of the Italian ''municipia''" E. Fraenkel, ''Horace'', 5–6 The poem includes this passage:

If my character is flawed by a few minor faults, but is otherwise decent and moral, if you can point out only a few scattered blemishes on an otherwise immaculate surface, if no one can accuse me of greed, or of prurience, or of profligacy, if I live a virtuous life, free of defilement (pardon, for a moment, my self-praise), and if I am to my friends a good friend, my father deserves all the credit... As it is now, he deserves from me unstinting gratitude and praise. I could never be ashamed of such a father, nor do I feel any need, as many people do, to apologize for being a freedman's son. ''Satires 1.6.65–92''He never mentioned his mother in his verses and he might not have known much about her. Perhaps she also had been a slave.

Adulthood

Horace left Rome, possibly after his father's death, and continued his formal education in Athens, a great centre of learning in the ancient world, where he arrived at nineteen years of age, enrolling in The Academy. Founded byPlato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, The Academy was now dominated by Epicureans

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

and Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

, whose theories and practises made a deep impression on the young man from Venusia. Meanwhile, he mixed and lounged about with the elite of Roman youth, such as Marcus, the idle son of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, and the Pompeius to whom he later addressed a poem. It was in Athens too that he probably acquired deep familiarity with the ancient tradition of Greek lyric poetry, at that time largely the preserve of grammarians and academic specialists (access to such material was easier in Athens than in Rome, where the public libraries had yet to be built by Asinius Pollio

Gaius Asinius Pollio (75 BC – AD 4) was a Roman soldier, politician, orator, poet, playwright, literary critic, and historian, whose lost contemporary history provided much of the material used by the historians Appian and Plutarch. Poll ...

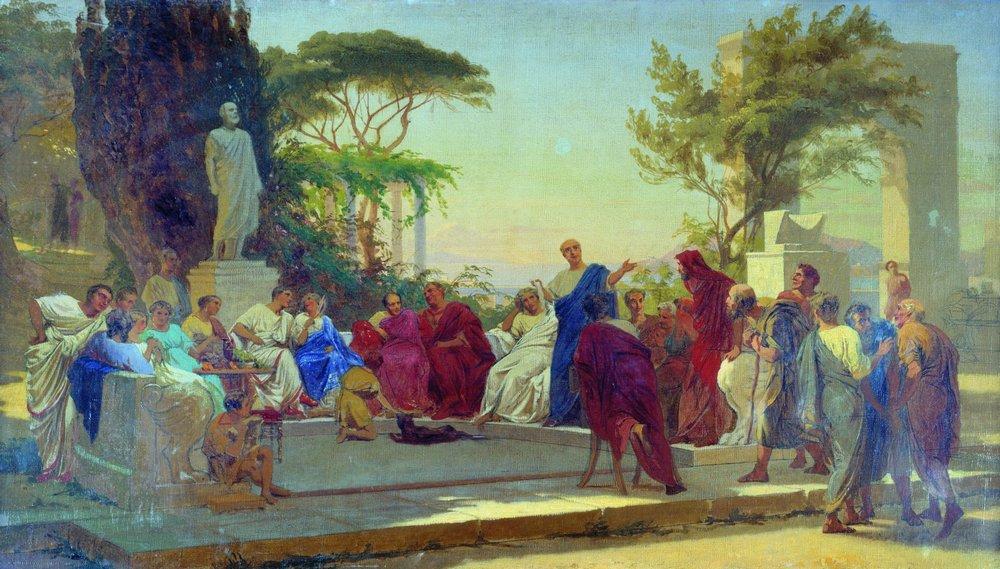

and Augustus).

Rome's troubles following the assassination of Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

were soon to catch up with him. Marcus Junius Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC), often referred to simply as Brutus, was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Serv ...

came to Athens seeking support for the republican cause. Brutus was fêted around town in grand receptions and he made a point of attending academic lectures, all the while recruiting supporters among the young men studying there, including Horace. An educated young Roman could begin military service high in the ranks and Horace was made tribunus militum

A military tribune (Latin ''tribunus militum'', "tribune of the soldiers") was an officer of the Roman army who ranked below the legate and above the centurion. Young men of Equestrian rank often served as military tribune as a stepping stone to ...

(one of six senior officers of a typical legion), a post usually reserved for men of senatorial or equestrian rank and which seems to have inspired jealousy among his well-born confederates.R. Nisbet, ''Horace: life and chronology'', 8 He learned the basics of military life while on the march, particularly in the wilds of northern Greece, whose rugged scenery became a backdrop to some of his later poems. It was there in 42 BC that Octavian

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

(later Augustus

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pri ...

) and his associate Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

crushed the republican forces at the Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Wars of the Second Triumvirate between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC, at P ...

. Horace later recorded it as a day of embarrassment for himself, when he fled without his shield, but allowance should be made for his self-deprecating humour. Moreover, the incident allowed him to identify himself with some famous poets who had long ago abandoned their shields in battle, notably his heroes Alcaeus and Archilochus

Archilochus (; grc-gre, Ἀρχίλοχος ''Arkhilokhos''; c. 680 – c. 645 BC) was a Greek lyric poet of the Archaic period from the island of Paros. He is celebrated for his versatile and innovative use of poetic meters, and is the ea ...

. The comparison with the latter poet is uncanny: Archilochus lost his shield in a part of Thrace near Philippi, and he was deeply involved in the Greek colonization of Thasos

Thasos or Thassos ( el, Θάσος, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate re ...

, where Horace's die-hard comrades finally surrendered.

Octavian offered an early amnesty to his opponents and Horace quickly accepted it. On returning to Italy, he was confronted with yet another loss: his father's estate in Venusia was one of many throughout Italy to be confiscated for the settlement of veterans (Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

lost his estate in the north about the same time). Horace later claimed that he was reduced to poverty and this led him to try his hand at poetry. In reality, there was no money to be had from versifying. At best, it offered future prospects through contacts with other poets and their patrons among the rich. Meanwhile, he obtained the sinecure of ''scriba quaestorius'', a civil service position at the ''aerarium'' or Treasury, profitable enough to be purchased even by members of the ''ordo equester'' and not very demanding in its work-load, since tasks could be delegated to ''scribae'' or permanent clerks. It was about this time that he began writing his ''Satires'' and ''Epodes''.

He describes in glowing terms the country villa which his patron, Maecenas, had given him in a letter to his friend Quintius:

The remains of Horace's Villa are situated on a wooded hillside above the river at Licenza

Licenza is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Metropolitan City of Rome in the Italian region Latium, located about northeast of Rome.

Licenza borders the following municipalities: Mandela, Monteflavio, Percile, Roccagiovine, San Polo dei Cav ...

, which joins the Aniene as it flows on to Tivoli.

Poet

The ''Epodes'' belong to

The ''Epodes'' belong to iambic poetry

Iambus or iambic poetry was a genre of ancient Greek poetry that included but was not restricted to the iambic meter and whose origins modern scholars have traced to the cults of Demeter and Dionysus. The genre featured insulting and obscene lan ...

. Iambic poetry features insulting and obscene language; sometimes, it is referred to as ''blame poetry''. ''Blame poetry'', or ''shame poetry'', is poetry written to blame and shame fellow citizens into a sense of their social obligations. Each poem normally has a archetype person Horace decides to shame, or teach a lesson to. Horace modelled these poems on the poetry of Archilochus

Archilochus (; grc-gre, Ἀρχίλοχος ''Arkhilokhos''; c. 680 – c. 645 BC) was a Greek lyric poet of the Archaic period from the island of Paros. He is celebrated for his versatile and innovative use of poetic meters, and is the ea ...

. Social bonds in Rome had been decaying since the destruction of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

a little more than a hundred years earlier, due to the vast wealth that could be gained by plunder and corruption. These social ills were magnified by rivalry between Julius Caesar, Mark Antony and confederates like Sextus Pompey

Sextus Pompeius Magnus Pius ( 67 – 35 BC), also known in English as Sextus Pompey, was a Roman military leader who, throughout his life, upheld the cause of his father, Pompey the Great, against Julius Caesar and his supporters during the last ...

, all jockeying for a bigger share of the spoils. One modern scholar has counted a dozen civil wars in the hundred years leading up to 31 BC, including the Spartacus

Spartacus ( el, Σπάρτακος '; la, Spartacus; c. 103–71 BC) was a Thracian gladiator who, along with Crixus, Gannicus, Castus, and Oenomaus, was one of the escaped slave leaders in the Third Servile War, a major slave uprising ...

rebellion, eight years before Horace's birth. As the heirs to Hellenistic culture, Horace and his fellow Romans were not well prepared to deal with these problems:

Horace's Hellenistic background is clear in his Satires, even though the genre was unique to Latin literature. He brought to it a style and outlook suited to the social and ethical issues confronting Rome but he changed its role from public, social engagement to private meditation. Meanwhile, he was beginning to interest Octavian's supporters, a gradual process described by him in one of his satires. The way was opened for him by his friend, the poet Virgil, who had gained admission into the privileged circle around Maecenas, Octavian's lieutenant, following the success of his ''Eclogues

The ''Eclogues'' (; ), also called the ''Bucolics'', is the first of the three major works of the Latin poet Virgil.

Background

Taking as his generic model the Greek bucolic poetry of Theocritus, Virgil created a Roman version partly by offer ...

''. An introduction soon followed and, after a discreet interval, Horace too was accepted. He depicted the process as an honourable one, based on merit and mutual respect, eventually leading to true friendship, and there is reason to believe that his relationship was genuinely friendly, not just with Maecenas but afterwards with Augustus as well. On the other hand, the poet has been unsympathetically described by one scholar as "a sharp and rising young man, with an eye to the main chance." There were advantages on both sides: Horace gained encouragement and material support, the politicians gained a hold on a potential dissident.R. Nisbet, ''Horace: life and chronology'', 10 His republican sympathies, and his role at Philippi, may have caused him some pangs of remorse over his new status. However most Romans considered the civil wars to be the result of ''contentio dignitatis'', or rivalry between the foremost families of the city, and he too seems to have accepted the principate as Rome's last hope for much needed peace.

In 37 BC, Horace accompanied Maecenas on a journey to Brundisium

Brindisi ( , ) ; la, Brundisium; grc, Βρεντέσιον, translit=Brentésion; cms, Brunda), group=pron is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea.

Histor ...

, described in one of his poems as a series of amusing incidents and charming encounters with other friends along the way, such as Virgil. In fact the journey was political in its motivation, with Maecenas en route to negotiatie the Treaty of Tarentum

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal perso ...

with Antony, a fact Horace artfully keeps from the reader (political issues are largely avoided in the first book of satires). Horace was probably also with Maecenas on one of Octavian's naval expeditions against the piratical Sextus Pompeius, which ended in a disastrous storm off Palinurus

Palinurus (''Palinūrus''), in Roman mythology and especially Virgil's ''Aeneid'', is the coxswain of Aeneas' ship. Later authors used him as a general type of navigator or guide. Palinurus is an example of human sacrifice; his life is the price ...

in 36 BC, briefly alluded to by Horace in terms of near-drowning.''Odes'' 3.4.28: "nec (me extinxit) Sicula Palinurus unda"; "nor did Palinurus extinguish me with Sicilian waters". Maecenas' involvement is recorded by Appian

Appian of Alexandria (; grc-gre, Ἀππιανὸς Ἀλεξανδρεύς ''Appianòs Alexandreús''; la, Appianus Alexandrinus; ) was a Greek historian with Roman citizenship who flourished during the reigns of Emperors of Rome Trajan, Hadr ...

''Bell. Civ.'' 5.99 but Horace's ode is the only historical reference to his own presence there, depending however on interpretation. (R. Nisbet, ''Horace: life and chronology'', 10) There are also some indications in his verses that he was with Maecenas at the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet of Octavian led by Marcus Agrippa and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, nea ...

in 31 BC, where Octavian defeated his great rival, Antony.The point is much disputed among scholars and hinges on how the text is interpreted. ''Epodes'' 9 for example may offer proof of Horace's presence if 'ad hunc frementis' ('gnashing at this' man i.e. the traitrous Roman ) is a misreading of 'at huc...verterent' (but hither...they fled) in lines describing the defection of the Galatian cavalry, "ad hunc frementis verterunt bis mille equos / Galli canentes Caesarem" (R. Nisbet, ''Horace: life and chronology'', 12). By then Horace had already received from Maecenas the famous gift of his Sabine farm, probably not long after the publication of the first book of ''Satires''. The gift, which included income from five tenants, may have ended his career at the Treasury, or at least allowed him to give it less time and energy. It signalled his identification with the Octavian regime yet, in the second book of ''Satires'' that soon followed, he continued the apolitical stance of the first book. By this time, he had attained the status of '' eques Romanus'' (Roman 'cavalryman', 'knight'), perhaps as a result of his work at the Treasury.

Knight

''Odes'' 1–3 were the next focus for his artistic creativity. He adapted their forms and themes from Greek lyric poetry of the seventh and sixth centuries BC. The fragmented nature of theGreek world

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in History of the Mediterranean region, Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as sig ...

had enabled his literary heroes to express themselves freely and his semi-retirement from the Treasury in Rome to his own estate in the Sabine hills perhaps empowered him to some extent also yet even when his lyrics touched on public affairs they reinforced the importance of private life. Nevertheless, his work in the period 30–27 BC began to show his closeness to the regime and his sensitivity to its developing ideology. In ''Odes'' 1.2, for example, he eulogized Octavian in hyperboles that echo Hellenistic court poetry. The name ''Augustus'', which Octavian assumed in 27 January BC, is first attested in ''Odes'' 3.3 and 3.5. In the period 27–24 BC, political allusions in the ''Odes'' concentrated on foreign wars in Britain (1.35), Arabia (1.29) Spain (3.8) and Parthia (2.2). He greeted Augustus on his return to Rome in 24 BC as a beloved ruler upon whose good health he depended for his own happiness (3.14).

The public reception of ''Odes'' 1–3 disappointed him, however. He attributed the lack of success to jealousy among imperial courtiers and to his isolation from literary cliques. Perhaps it was disappointment that led him to put aside the genre in favour of verse letters. He addressed his first book of ''Epistles'' to a variety of friends and acquaintances in an urbane style reflecting his new social status as a knight. In the opening poem, he professed a deeper interest in moral philosophy than poetry but, though the collection demonstrates a leaning towards stoic theory, it reveals no sustained thinking about ethics. Maecenas was still the dominant confidante but Horace had now begun to assert his own independence, suavely declining constant invitations to attend his patron. In the final poem of the first book of ''Epistles'', he revealed himself to be forty-four years old in the consulship of Lollius and Lepidus i.e. 21 BC, and "of small stature, fond of the sun, prematurely grey, quick-tempered but easily placated".

According to Suetonius, the second book of ''Epistles'' was prompted by Augustus, who desired a verse epistle to be addressed to himself. Augustus was in fact a prolific letter-writer and he once asked Horace to be his personal secretary. Horace refused the secretarial role but complied with the emperor's request for a verse letter. The letter to Augustus may have been slow in coming, being published possibly as late as 11 BC. It celebrated, among other things, the 15 BC military victories of his stepsons, Drusus and Tiberius, yet it and the following letter were largely devoted to literary theory and criticism. The literary theme was explored still further in ''Ars Poetica'', published separately but written in the form of an epistle and sometimes referred to as ''Epistles'' 2.3 (possibly the last poem he ever wrote). He was also commissioned to write odes commemorating the victories of Drusus and Tiberius and one to be sung in a temple of Apollo for the Secular Games

The Saecular Games ( la, Ludi saeculares, originally ) was a Roman religious celebration involving sacrifices and theatrical performances, held in ancient Rome for three days and nights to mark the end of a and the beginning of the next. A , sup ...

, a long-abandoned festival that Augustus revived in accordance with his policy of recreating ancient customs (''Carmen Saeculare'').

Suetonius recorded some gossip about Horace's sexual activities late in life, claiming that the walls of his bedchamber were covered with obscene pictures and mirrors, so that he saw erotica wherever he looked.Suetonius signals that the report is based on rumours by employing the terms "traditur...dicitur" / "it is reported...it is said" (E. Fraenkel, ''Horace'', 21) The poet died at 56 years of age, not long after his friend Maecenas, near whose tomb he was laid to rest. Both men bequeathed their property to Augustus, an honour that the emperor expected of his friends.

Works

The dating of Horace's works isn't known precisely and scholars often debate the exact order in which they were first 'published'. There are persuasive arguments for the following chronology: * ''Satires 1

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or ...

'' (c. 35–34 BC)

* '' Satires 2'' (c. 30 BC)

* '' Epodes'' (30 BC)

* '' Odes 1–3'' (c. 23 BC)According to a recent theory, the three books of ''Odes'' were issued separately, possibly in 26, 24 and 23 BC (see G. Hutchinson (2002), ''Classical Quarterly'' 52: 517–37)

* '' Epistles 1'' (c. 21 BC)

* ''Carmen Saeculare

The ''Carmen Saeculare'' (Latin for "Secular Hymn" or "Song of the Ages") is a hymn in Sapphic meter written by the Roman poet Horace. It was commissioned by the Roman emperor Augustus in 17 BC. The hymn was sung by a chorus of twenty-seven maid ...

'' (17 BC)

* '' Epistles 2'' (c. 11 BC)19 BC is the usual estimate but c. 11 BC has good support too (see R. Nisbet, ''Horace: life and chronology'', 18–20

* '' Odes 4'' (c. 11 BC)

* '' Ars Poetica'' (c. 10–8 BC)The date however is subject to much controversy with 22–18 BC another option (see for example R. Syme, ''The Augustan Aristocracy'', 379–81

Historical context

Horace composed in traditionalmetres

The metre (British spelling) or meter (American spelling; see spelling differences) (from the French unit , from the Greek noun , "measure"), symbol m, is the primary unit of length in the International System of Units (SI), though its prefi ...

borrowed from Archaic Greece

Archaic Greece was the period in Greek history lasting from circa 800 BC to the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and succeeded by the Classical period. In the archaic period, Greeks settled across the ...

, employing hexameter

Hexameter is a metrical line of verses consisting of six feet (a "foot" here is the pulse, or major accent, of words in an English line of poetry; in Greek and Latin a "foot" is not an accent, but describes various combinations of syllables). It w ...

s in his ''Satires'' and ''Epistles'', and iambs in his ''Epodes'', all of which were relatively easy to adapt into Latin forms. His ''Odes'' featured more complex measures, including alcaics The Alcaic stanza is a Greek lyrical meter, an Aeolic verse form traditionally believed to have been invented by Alcaeus, a lyric poet from Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, about 600 BC. The Alcaic stanza and the Sapphic stanza named for Alcaeus' ...

and sapphics

The Sapphic stanza, named after Sappho, is an Aeolic verse form of four lines. Originally composed in quantitative verse and unrhymed, since the Middle Ages imitations of the form typically feature rhyme and accentual prosody. It is "the longest ...

, which were sometimes a difficult fit for Latin structure and syntax

In linguistics, syntax () is the study of how words and morphemes combine to form larger units such as phrases and sentences. Central concerns of syntax include word order, grammatical relations, hierarchical sentence structure ( constituency) ...

. Despite these traditional metres, he presented himself as a partisan in the development of a new and sophisticated style. He was influenced in particular by Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

aesthetics of brevity, elegance and polish, as modelled in the work of Callimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variety ...

.

In modern literary theory, a distinction is often made between immediate personal experience (''Urerlebnis'') and experience mediated by cultural vectors such as literature, philosophy and the visual arts (''Bildungserlebnis''). The distinction has little relevance for Horace however since his personal and literary experiences are implicated in each other. ''Satires'' 1.5, for example, recounts in detail a real trip Horace made with Virgil and some of his other literary friends, and which parallels a Satire by Lucilius

The gens Lucilia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. The most famous member of this gens was the poet Gaius Lucilius, who flourished during the latter part of the second century BC.''Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology'', vo ...

, his predecessor. Unlike much Hellenistic-inspired literature, however, his poetry was not composed for a small coterie of admirers and fellow poets, nor does it rely on abstruse allusions for many of its effects. Though elitist in its literary standards, it was written for a wide audience, as a public form of art. Ambivalence also characterizes his literary persona, since his presentation of himself as part of a small community of philosophically aware people, seeking true peace of mind while shunning vices like greed, was well adapted to Augustus's plans to reform public morality, corrupted by greed—his personal plea for moderation was part of the emperor's grand message to the nation.

Horace generally followed the examples of poets established as classics in different genres, such as Archilochus

Archilochus (; grc-gre, Ἀρχίλοχος ''Arkhilokhos''; c. 680 – c. 645 BC) was a Greek lyric poet of the Archaic period from the island of Paros. He is celebrated for his versatile and innovative use of poetic meters, and is the ea ...

in the ''Epodes'', Lucilius in the ''Satires'' and Alcaeus in the ''Odes'', later broadening his scope for the sake of variation and because his models weren't actually suited to the realities confronting him. Archilochus and Alcaeus were aristocratic Greeks whose poetry had a social and religious function that was immediately intelligible to their audiences but which became a mere artifice or literary motif when transposed to Rome. However, the artifice of the ''Odes'' is also integral to their success, since they could now accommodate a wide range of emotional effects, and the blend of Greek and Roman elements adds a sense of detachment and universality. Horace proudly claimed to introduce into Latin the spirit and iambic poetry of Archilochus but (unlike Archilochus) without persecuting anyone (''Epistles'' 1.19.23–25). It was no idle boast. His ''Epodes'' were modelled on the verses of the Greek poet, as 'blame poetry', yet he avoided targeting real scapegoat

In the Bible, a scapegoat is one of a pair of kid goats that is released into the wilderness, taking with it all sins and impurities, while the other is sacrificed. The concept first appears in the Book of Leviticus, in which a goat is designate ...

s. Whereas Archilochus presented himself as a serious and vigorous opponent of wrong-doers, Horace aimed for comic effects and adopted the persona of a weak and ineffectual critic of his times (as symbolized for example in his surrender to the witch Canidia in the final epode). He also claimed to be the first to introduce into Latin the lyrical methods of Alcaeus (''Epistles'' 1.19.32–33) and he actually was the first Latin poet to make consistent use of Alcaic meters and themes: love, politics and the symposium

In ancient Greece, the symposium ( grc-gre, συμπόσιον ''symposion'' or ''symposio'', from συμπίνειν ''sympinein'', "to drink together") was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was acc ...

. He imitated other Greek lyric poets as well, employing a 'motto' technique, beginning each ode with some reference to a Greek original and then diverging from it.

The satirical poet Lucilius was a senator's son who could castigate his peers with impunity. Horace was a mere freedman's son who had to tread carefully.E. Fraenkel, ''Horace'', 32, 80 Lucilius was a rugged patriot and a significant voice in Roman self-awareness, endearing himself to his countrymen by his blunt frankness and explicit politics. His work expressed genuine freedom or libertas

Libertas (Latin for 'liberty' or 'freedom', ) is the Roman goddess and personification of liberty. She became a politicised figure in the Late Republic, featured on coins supporting the populares faction, and later those of the assassins of Jul ...

. His style included 'metrical vandalism' and looseness of structure. Horace instead adopted an oblique and ironic style of satire, ridiculing stock characters and anonymous targets. His libertas was the private freedom of a philosophical outlook, not a political or social privilege. His ''Satires'' are relatively easy-going in their use of meter (relative to the tight lyric meters of the ''Odes'') but formal and highly controlled relative to the poems of Lucilius, whom Horace mocked for his sloppy standards (''Satires'' 1.10.56–61)" ucilius..resembles a man whose only concern is to force / something into the framework of six feet, and who gaily produces / two hundred lines before dinner and another two hundred after."''Satire'' 1.10.59–61 (translated by Niall Rudd

William James Niall Rudd (23 June 1927 – 5 October 2015) was an Irish-born British classical scholar.

Life and work

Rudd was born in Dublin and studied Classics at Trinity College, Dublin. He then taught Latin at the Universities of Hull and ...

, ''The Satires of Horace and Persius'', Penguin Classics 1973, p. 69)

The ''Epistles'' may be considered among Horace's most innovative works. There was nothing like it in Greek or Roman literature. Occasionally poems had had some resemblance to letters, including an elegiac poem from Solon

Solon ( grc-gre, Σόλων; BC) was an Athenian statesman, constitutional lawmaker and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in Archaic Athens.Aristotle ''Politics'' ...

to Mimnermus

Mimnermus ( grc-gre, Μίμνερμος ''Mímnermos'') was a Greek elegiac poet from either Colophon or Smyrna in Ionia, who flourished about 632–629 BC (i.e. in the 37th Olympiad, according to Suda). He was strongly influenced by the examp ...

and some lyrical poems from Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar is ...

to Hieron of Syracuse

Hieron I ( el, Ἱέρων Α΄; usually Latinized Hiero) was the son of Deinomenes, the brother of Gelon and tyrant of Syracuse in Sicily from 478 to 467 BC. In succeeding Gelon, he conspired against a third brother, Polyzelos.

Life

During his ...

. Lucilius had composed a satire in the form of a letter, and some epistolary poems were composed by Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His s ...

and Propertius

Sextus Propertius was a Latin elegiac poet of the Augustan age. He was born around 50–45 BC in Assisium and died shortly after 15 BC.

Propertius' surviving work comprises four books of ''Elegies'' ('). He was a friend of the poets Gallus a ...

. But nobody before Horace had ever composed an entire collection of verse letters, let alone letters with a focus on philosophical problems. The sophisticated and flexible style that he had developed in his ''Satires'' was adapted to the more serious needs of this new genre. Such refinement of style was not unusual for Horace. His craftsmanship as a wordsmith is apparent even in his earliest attempts at this or that kind of poetry, but his handling of each genre tended to improve over time as he adapted it to his own needs. Thus for example it is generally agreed that his second book of ''Satires'', where human folly is revealed through dialogue between characters, is superior to the first, where he propounds his ethics in monologues. Nevertheless, the first book includes some of his most popular poems.

Themes

Horace developed a number of inter-related themes throughout his poetic career, including politics, love, philosophy and ethics, his own social role, as well as poetry itself. His ''Epodes'' and ''Satires'' are forms of 'blame poetry' and both have a natural affinity with the moralising and diatribes ofCynicism

Cynic or Cynicism may refer to:

Modes of thought

* Cynicism (philosophy), a school of ancient Greek philosophy

* Cynicism (contemporary), modern use of the word for distrust of others' motives

Books

* ''The Cynic'', James Gordon Stuart Grant 1 ...

. This often takes the form of allusions to the work and philosophy of Bion of Borysthenes

Bion of Borysthenes ( el, Βίων Βορυσθενίτης, ''gen''.: Βίωνος; BC) was a Greek philosopher. After being sold into slavery, and then released, he moved to Athens, where he studied in almost every school of philosophy. It ...

There is one reference to Bion by name in ''Epistles'' 2.2.60, and the clearest allusion to him is in ''Satire'' 1.6, which parallels Bion fragments 1, 2, 16 ''Kindstrand'' but it is as much a literary game as a philosophical alignment.

By the time he composed his ''Epistles'', he was a critic of Cynicism

Cynic or Cynicism may refer to:

Modes of thought

* Cynicism (philosophy), a school of ancient Greek philosophy

* Cynicism (contemporary), modern use of the word for distrust of others' motives

Books

* ''The Cynic'', James Gordon Stuart Grant 1 ...

along with all impractical and "high-falutin" philosophy in general.''Epistles'' 1.17 and 1.18.6–8 are critical of the extreme views of Diogenes

Diogenes ( ; grc, Διογένης, Diogénēs ), also known as Diogenes the Cynic (, ) or Diogenes of Sinope, was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of Cynicism (philosophy). He was born in Sinope, an Ionian colony on the Black Sea ...

and also of social adaptations of Cynic precepts, and yet ''Epistle'' 1.2 could be either Cynic or Stoic in its orientation (J. Moles, ''Philosophy and ethics'', p. 177

The ''Satires'' also include a strong element of Epicureanism

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

, with frequent allusions to the Epicurean poet Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus ( , ; – ) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem ''De rerum natura'', a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, and which usually is translated into E ...

.''Satires'' 1.1.25–26, 74–75, 1.2.111–12, 1.3.76–77, 97–114, 1.5.44, 101–03, 1.6.128–31, 2.2.14–20, 25, 2.6.93–97 So for example the Epicurean sentiment ''carpe diem

is a Latin aphorism, usually translated "seize the day", taken from book 1 of the Roman poet Horace's work ''Odes'' (23 BC).

Translation

is the second-person singular present active imperative of '' carpō'' "pick or pluck" used by Horace t ...

'' is the inspiration behind Horace's repeated punning on his own name (''Horatius ~ hora'') in ''Satires'' 2.6. The ''Satires'' also feature some Stoic

Stoic may refer to:

* An adherent of Stoicism; one whose moral quality is associated with that school of philosophy

*STOIC, a programming language

* ''Stoic'' (film), a 2009 film by Uwe Boll

* ''Stoic'' (mixtape), a 2012 mixtape by rapper T-Pain

*' ...

, Peripatetic

Peripatetic may refer to:

*Peripatetic school, a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece

*Peripatetic axiom

* Peripatetic minority, a mobile population moving among settled populations offering a craft or trade.

*Peripatetic Jats

There are several ...

and Platonic

Plato's influence on Western culture was so profound that several different concepts are linked by being called Platonic or Platonist, for accepting some assumptions of Platonism, but which do not imply acceptance of that philosophy as a whole. It ...

(''Dialogues'') elements. In short, the ''Satires'' present a medley of philosophical programmes, dished up in no particular order—a style of argument typical of the genre

Genre () is any form or type of communication in any mode (written, spoken, digital, artistic, etc.) with socially-agreed-upon conventions developed over time. In popular usage, it normally describes a category of literature, music, or other for ...

.

The ''Odes'' display a wide range of topics. Over time, he becomes more confident about his political voice. Although he is often thought of as an overly intellectual lover, he is ingenious in representing passion. The "Odes" weave various philosophical strands together, with allusions and statements of doctrine present in about a third of the ''Odes'' Books 1–3, ranging from the flippant (1.22, 3.28) to the solemn (2.10, 3.2, 3.3). Epicureanism

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

is the dominant influence, characterising about twice as many of these odes as Stoicism.

A group of odes combines these two influences in tense relationships, such as ''Odes'' 1.7, praising Stoic virility and devotion to public duty while also advocating private pleasures among friends. While generally favouring the Epicurean lifestyle, the lyric poet is as eclectic as the satiric poet, and in ''Odes'' 2.10 even proposes Aristotle's golden mean as a remedy for Rome's political troubles.

Many of Horace's poems also contain much reflection on genre, the lyric tradition, and the function of poetry. ''Odes'' 4, thought to be composed at the emperor's request, takes the themes of the first three books of "Odes" to a new level. This book shows greater poetic confidence after the public performance of his "Carmen saeculare" or "Century hymn" at a public festival orchestrated by Augustus. In it, Horace addresses the emperor Augustus directly with more confidence and proclaims his power to grant poetic immortality to those he praises. It is the least philosophical collection of his verses, excepting the twelfth ode, addressed to the dead Virgil as if he were living. In that ode, the epic poet and the lyric poet are aligned with Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

and Epicureanism

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

respectively, in a mood of bitter-sweet pathos.

The first poem of the ''Epistles'' sets the philosophical tone for the rest of the collection: "So now I put aside both verses and all those other games: What is true and what befits is my care, this my question, this my whole concern." His poetic renunciation of poetry in favour of philosophy is intended to be ambiguous. Ambiguity is the hallmark of the ''Epistles''. It is uncertain if those being addressed by the self-mocking poet-philosopher are being honoured or criticised. Though he emerges as an Epicurean

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BC based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism. Later its main opponent became Stoicism.

Few writings by Epi ...

, it is on the understanding that philosophical preferences, like political and social choices, are a matter of personal taste. Thus he depicts the ups and downs of the philosophical life more realistically than do most philosophers.

Reception

The reception of Horace's work has varied from one epoch to another and varied markedly even in his own lifetime. ''Odes'' 1–3 were not well received when first 'published' in Rome, yet Augustus later commissioned a ceremonial ode for the Centennial Games in 17 BC and also encouraged the publication of ''Odes'' 4, after which Horace's reputation as Rome's premier lyricist was assured. His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ode-writing became highly fashionable in England and a large number of aspiring poets imitated Horace both in English and in Latin.

In a verse epistle to Augustus (Epistle 2.1), in 12 BC, Horace argued for classic status to be awarded to contemporary poets, including Virgil and apparently himself. In the final poem of his third book of Odes he claimed to have created for himself a monument more durable than bronze ("Exegi monumentum aere perennius", ''

The reception of Horace's work has varied from one epoch to another and varied markedly even in his own lifetime. ''Odes'' 1–3 were not well received when first 'published' in Rome, yet Augustus later commissioned a ceremonial ode for the Centennial Games in 17 BC and also encouraged the publication of ''Odes'' 4, after which Horace's reputation as Rome's premier lyricist was assured. His Odes were to become the best received of all his poems in ancient times, acquiring a classic status that discouraged imitation: no other poet produced a comparable body of lyrics in the four centuries that followed (though that might also be attributed to social causes, particularly the parasitism that Italy was sinking into). In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, ode-writing became highly fashionable in England and a large number of aspiring poets imitated Horace both in English and in Latin.

In a verse epistle to Augustus (Epistle 2.1), in 12 BC, Horace argued for classic status to be awarded to contemporary poets, including Virgil and apparently himself. In the final poem of his third book of Odes he claimed to have created for himself a monument more durable than bronze ("Exegi monumentum aere perennius", ''Carmina

The ''Odes'' ( la, Carmina) are a collection in four books of Latin lyric poems by Horace. The Horatian ode format and style has been emulated since by other poets. Books 1 to 3 were published in 23 BC. A fourth book, consisting of 15 poems, was ...

'' 3.30.1). For one modern scholar, however, Horace's personal qualities are more notable than the monumental quality of his achievement:

Yet for men like Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of trenches and gas warfare was much influenced by ...

, scarred by experiences of World War I, his poetry stood for discredited values:

The same motto, ''Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori

' is a line from the ''Odes'' (III.2.13) by the Roman lyric poet Horace. The line translates: "It is sweet and proper to die for one's country." The Latin word ''patria'' (homeland), literally meaning the country of one's fathers (in Latin, ' ...

'', had been adapted to the ethos of martyrdom in the lyrics of early Christian poets like Prudentius

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens () was a Roman citizen, Roman Christianity, Christian poet, born in the Roman Empire, Roman province of Tarraconensis (now Northern Spain) in 348.H. J. Rose, ''A Handbook of Classical Literature'' (1967) p. 508 He prob ...

.

These preliminary comments touch on a small sample of developments in the reception of Horace's work. More developments are covered epoch by epoch in the following sections.

Antiquity

Horace's influence can be observed in the work of his near contemporaries,Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the th ...

and Propertius

Sextus Propertius was a Latin elegiac poet of the Augustan age. He was born around 50–45 BC in Assisium and died shortly after 15 BC.

Propertius' surviving work comprises four books of ''Elegies'' ('). He was a friend of the poets Gallus a ...

. Ovid followed his example in creating a completely natural style of expression in hexameter verse, and Propertius cheekily mimicked him in his third book of elegies.Propertius published his third book of elegies within a year or two of Horace's Odes 1–3 and mimicked him, for example, in the opening lines, characterizing himself in terms borrowed from Odes 3.1.13 and 3.30.13–14, as a priest of the Muses and as an adaptor of Greek forms of poetry (R. Tarrant, ''Ancient receptions of Horace'', 227) His ''Epistles'' provided them both with a model for their own verse letters and it also shaped Ovid's exile poetry.Ovid for example probably borrowed from Horace's ''Epistle'' 1.20 the image of a poetry book as a slave boy eager to leave home, adapting it to the opening poems of ''Tristia'' 1 and 3 (R. Tarrant, ''Ancient receptions of Horace''), and ''Tristia'' 2 May be understood as a counterpart to Horace's ''Epistles'' 2.1, both being letters addressed to Augustus on literary themes (A. Barchiesi, ''Speaking Volumes'', 79–103)

His influence had a perverse aspect. As mentioned before, the brilliance of his ''Odes'' may have discouraged imitation. Conversely, they may have created a vogue for the lyrics of the archaic Greek poet Pindar

Pindar (; grc-gre, Πίνδαρος , ; la, Pindarus; ) was an Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes. Of the canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar is ...

, due to the fact that Horace had neglected that style of lyric (see Influence and Legacy of Pindar). The iambic genre seems almost to have disappeared after publication of Horace's ''Epodes''. Ovid's ''Ibis'' was a rare attempt at the form but it was inspired mainly by Callimachus

Callimachus (; ) was an ancient Greek poet, scholar and librarian who was active in Alexandria during the 3rd century BC. A representative of Ancient Greek literature of the Hellenistic period, he wrote over 800 literary works in a wide variety ...

, and there are some iambic elements in Martial

Marcus Valerius Martialis (known in English as Martial ; March, between 38 and 41 AD – between 102 and 104 AD) was a Roman poet from Hispania (modern Spain) best known for his twelve books of ''Epigrams'', published in Rome between AD 86 and ...

but the main influence there was Catullus

Gaius Valerius Catullus (; 84 - 54 BCE), often referred to simply as Catullus (, ), was a Latin poet of the late Roman Republic who wrote chiefly in the neoteric style of poetry, focusing on personal life rather than classical heroes. His s ...

. A revival of popular interest in the satires of Lucilius may have been inspired by Horace's criticism of his unpolished style. Both Horace and Lucilius were considered good role-models by Persius

Aulus Persius Flaccus (; 4 December 3424 November 62 AD) was a Ancient Rome, Roman poet and satirist of Etruscan civilization, Etruscan origin. In his works, poems and satires, he shows a Stoicism, Stoic wisdom and a strong criticism for what he ...

, who critiqued his own satires as lacking both the acerbity of Lucillius and the gentler touch of Horace.The comment is in Persius 1.114–18, yet that same satire has been found to have nearly 80 reminiscences of Horace; see D. Hooley, ''The Knotted Thong'', 29 Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ), was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the ''Satires''. The details of Juvenal's life ...

's caustic satire was influenced mainly by Lucilius but Horace by then was a school classic and Juvenal could refer to him respectfully and in a round-about way as "''the Venusine lamp''".The allusion to ''Venusine'' comes via Horace's ''Sermones'' 2.1.35, while ''lamp'' signifies the lucubrations of a conscientious poet. According to Quintilian (93), however, many people in Flavian Rome preferred Lucilius not only to Horace but to all other Latin poets (R. Tarrant, ''Ancient receptions of Horace'', 279)

Statius

Publius Papinius Statius (Greek: Πόπλιος Παπίνιος Στάτιος; ; ) was a Greco-Roman poet of the 1st century CE. His surviving Latin poetry includes an epic in twelve books, the ''Thebaid''; a collection of occasional poetry, ...

paid homage to Horace by composing one poem in Sapphic and one in Alcaic meter (the verse forms most often associated with ''Odes''), which he included in his collection of occasional poems, ''Silvae''. Ancient scholars wrote commentaries on the lyric meters of the ''Odes'', including the scholarly poet Caesius Bassus

Gaius Caesius Bassus (d. AD 79) was a Roman lyric poet who lived in the reign of Nero.

He was the intimate friend of Persius, who dedicated his sixth satire to him, and whose works he edited (''Schol. on Persius'', vi. I). He had a great reputa ...

. By a process called ''derivatio'', he varied established meters through the addition or omission of syllables, a technique borrowed by Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was born in ...

when adapting Horatian meters to the stage.

Horace's poems continued to be school texts into late antiquity. Works attributed to Helenius Acro

Helenius Acron (or Acro) was a Roman commentator and grammarian, probably of the 3rd century AD, but whose precise date is not known.

Helenius Acron is known to have written on Terence ('' Adelphi'' and ''Eunuchus'' at least) and Horace. These ...

and Pomponius Porphyrio Pomponius Porphyrion (or Porphyrio) was a Latin grammarian and commentator on Horace.

Biography

He was possibly a native of Africa, and flourished during the 2nd century A.D. (according to some, much later).

Works

His ''scholia'' on Horace, which ...

are the remnants of a much larger body of Horatian scholarship. Porphyrio arranged the poems in non-chronological order, beginning with the ''Odes'', because of their general popularity and their appeal to scholars (the ''Odes'' were to retain this privileged position in the medieval manuscript tradition and thus in modern editions also). Horace was often evoked by poets of the fourth century, such as Ausonius

Decimius Magnus Ausonius (; – c. 395) was a Roman poet and teacher of rhetoric from Burdigala in Aquitaine, modern Bordeaux, France. For a time he was tutor to the future emperor Gratian, who afterwards bestowed the consulship on him. H ...

and Claudian

Claudius Claudianus, known in English as Claudian (; c. 370 – c. 404 AD), was a Latin poet associated with the court of the Roman emperor Honorius at Mediolanum (Milan), and particularly with the general Stilicho. His work, written almost ent ...

. Prudentius

Aurelius Prudentius Clemens () was a Roman citizen, Roman Christianity, Christian poet, born in the Roman Empire, Roman province of Tarraconensis (now Northern Spain) in 348.H. J. Rose, ''A Handbook of Classical Literature'' (1967) p. 508 He prob ...

presented himself as a Christian Horace, adapting Horatian meters to his own poetry and giving Horatian motifs a Christian tone.Prudentius sometimes alludesto the ''Odes'' in a negative context, as expressions of a secular life he is abandoning. Thus for example ''male pertinax'', employed in Prudentius's ''Praefatio'' to describe a willful desire for victory, is lifted from ''Odes'' 1.9.24, where it describes a girl's half-hearted resistance to seduction. Elsewhere he borrows ''dux bone'' from ''Odes'' 4.5.5 and 37, where it refers to Augustus, and applies it to Christ (R. Tarrant, ''Ancient receptions of Horace'', 282 On the other hand, St Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian priest, confessor, theologian, and historian; he is comm ...

, modelled an uncompromising response to the pagan Horace, observing: "''What harmony can there be between Christ and the Devil? What has Horace to do with the Psalter?''"St Jerome, ''Epistles'' 22.29, incorporating a quote from ''2 'Corinthians'' 6.14: ''qui consensus Christo et Belial? quid facit cum psalterio Horatius?''(cited by K. Friis-Jensen, ''Horace in the Middle Ages'', 292) By the early sixth century, Horace and Prudentius were both part of a classical heritage that was struggling to survive the disorder of the times. Boethius

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, commonly known as Boethius (; Latin: ''Boetius''; 480 – 524 AD), was a Roman senator, consul, ''magister officiorum'', historian, and philosopher of the Early Middle Ages. He was a central figure in the tr ...

, the last major author of classical Latin literature, could still take inspiration from Horace, sometimes mediated by Senecan tragedy.R. Tarrant, ''Ancient receptions of Horace'', 283 It can be argued that Horace's influence extended beyond poetry to dignify core themes and values of the early Christian era, such as self-sufficiency, inner contentment and courage.''Odes'' 3.3.1–8 was especially influential in promoting the value of heroic calm in the face of danger, describing a man who could bear even the collapse of the world without fear (''si fractus illabatur orbis,/impavidum ferient ruinae''). Echoes are found in Seneca's ''Agamemnon'' 593–603, Prudentius's ''Peristephanon'' 4.5–12 and Boethius's ''Consolatio'' 1 metrum 4.(R. Tarrant, ''Ancient receptions of Horace'', 283–85)

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Classical texts almost ceased being copied in the period between the mid sixth century and the Carolingian revival. Horace's work probably survived in just two or three books imported into northern Europe from Italy. These became the ancestors of six extant manuscripts dated to the ninth century. Two of those six manuscripts are French in origin, one was produced in

Classical texts almost ceased being copied in the period between the mid sixth century and the Carolingian revival. Horace's work probably survived in just two or three books imported into northern Europe from Italy. These became the ancestors of six extant manuscripts dated to the ninth century. Two of those six manuscripts are French in origin, one was produced in Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

, and the other three show Irish influence but were probably written in continental monasteries (Lombardy

Lombardy ( it, Lombardia, Lombard language, Lombard: ''Lombardia'' or ''Lumbardia' '') is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in the northern-central part of the country and has a population of about 10 ...

for example). By the last half of the ninth century, it was not uncommon for literate people to have direct experience of Horace's poetry. His influence on the Carolingian Renaissance

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. It occurred from the late 8th century to the 9th century, taking inspiration from the State church of the Roman Emp ...

can be found in the poems of Heiric of Auxerre

Heiric of Auxerre (841–876) was a French Benedictine theologian and writer.

He was an oblate of the monastery of St. Germanus of Auxerre from a young age. He studied with Servatus Lupus and Haymo of Auxerre. His own students included Remigius ...

Heiric, like Prudentius, gave Horatian motifs a Christian context. Thus the character Lydia in ''Odes'' 3.19.15, who would willingly die for her lover twice, becomes in Heiric's ''Life'' of St Germaine of Auxerre a saint ready to die twice for the Lord's commandments (R. Tarrant, ''Ancient receptions of Horace'', 287–88) and in some manuscripts marked with neumes

A neume (; sometimes spelled neum) is the basic element of Western and Eastern systems of musical notation prior to the invention of five-line staff notation.

The earliest neumes were inflective marks that indicated the general shape but not ne ...

, mysterious notations that may have been an aid to the memorization and discussion of his lyric meters. ''Ode'' 4.11 is neumed with the melody of a hymn to John the Baptist, ''Ut queant laxis

"" or "" is a Latin hymn in honor of John the Baptist, written in Horatian Sapphics with text traditionally attributed to Paulus Diaconus, the eighth-century Lombard historian. It is famous for its part in the history of musical notation, in par ...

'', composed in Sapphic stanza

The Sapphic stanza, named after Sappho, is an Aeolic verse form of four lines. Originally composed in quantitative verse and unrhymed, since the Middle Ages imitations of the form typically feature rhyme and accentual prosody. It is "the longest ...

s. This hymn later became the basis of the solfege system (''Do, re, mi...'')an association with western music quite appropriate for a lyric poet like Horace, though the language of the hymn is mainly Prudentian. Lyons argues that the melody in question was linked with Horace's Ode well before Guido d'Arezzo fitted Ut queant laxis

"" or "" is a Latin hymn in honor of John the Baptist, written in Horatian Sapphics with text traditionally attributed to Paulus Diaconus, the eighth-century Lombard historian. It is famous for its part in the history of musical notation, in par ...

to it. However, the melody is unlikely to be a survivor from classical times, although Ovid testifies to Horace's use of the lyre while performing his Odes.

The German scholar, Ludwig Traube Ludwig Traube may refer to:

*Ludwig Traube (physician) (1818–1876), German physician and co-founder of experimental pathology in Germany

*Ludwig Traube (palaeographer) (1861–1907), his son, German paleographer

{{hndis, Traube, Ludwig ...