Homo Heidelbergensis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

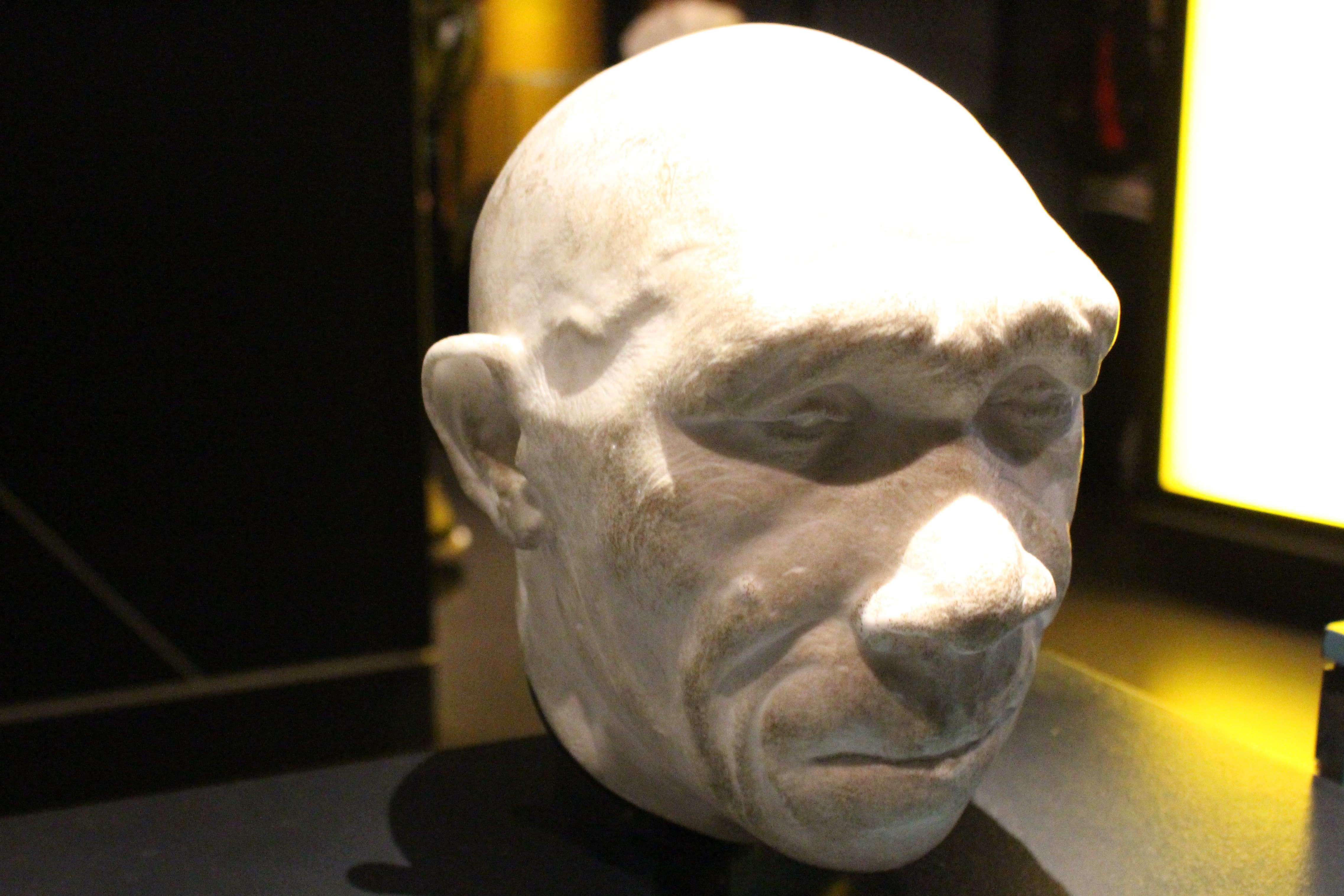

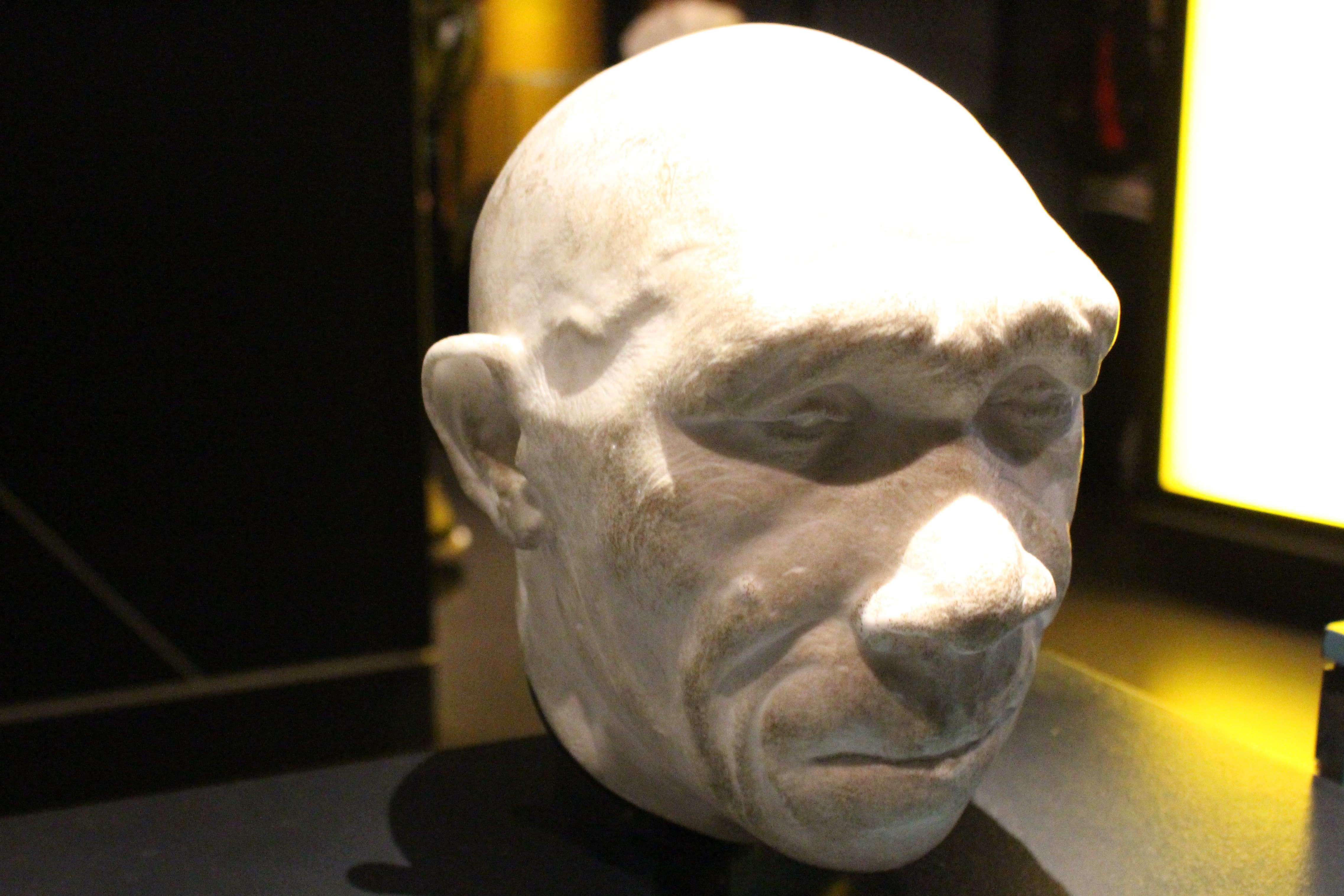

''Homo heidelbergensis'' (also ''H. sapiens heidelbergensis''), sometimes called Heidelbergs, is an extinct

Though ''H. erectus'' is still maintained as a highly variable, widespread and long-lasting species, it is still much debated whether or not sinking all Middle Pleistocene remains into it is justifiable. Mayr's lumping of ''H. heidelbergensis'' was first opposed by American anthropologist

Though ''H. erectus'' is still maintained as a highly variable, widespread and long-lasting species, it is still much debated whether or not sinking all Middle Pleistocene remains into it is justifiable. Mayr's lumping of ''H. heidelbergensis'' was first opposed by American anthropologist  In 1976 at Sima de los Huesos (SH) in the

In 1976 at Sima de los Huesos (SH) in the

Convenience link

In 2016, Antonio Profico and colleagues suggested that 875,000-year-old skull materials from the Gombore II site of the According to genetic analysis, the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthal split into a modern human line, and a Neanderthal/Denisovan line, and the latter later split into Neanderthal and Denisovans. According to

According to genetic analysis, the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthal split into a modern human line, and a Neanderthal/Denisovan line, and the latter later split into Neanderthal and Denisovans. According to

In comparison to Early Pleistocene ''H. erectus''/''ergaster'', Middle Pleistocene humans have a much more modern human-like face. The nasal opening is set completely vertically in the skull, and the anterior nasal sill can be crested or sometimes a prominent spine. The incisive canals (on the roof of the mouth) open near the teeth, and are orientated like those of more recent human species. The

In comparison to Early Pleistocene ''H. erectus''/''ergaster'', Middle Pleistocene humans have a much more modern human-like face. The nasal opening is set completely vertically in the skull, and the anterior nasal sill can be crested or sometimes a prominent spine. The incisive canals (on the roof of the mouth) open near the teeth, and are orientated like those of more recent human species. The  In 2009, palaeontologists Aurélien Mounier, François Marchal and Silvana Condemi published the first differential diagnosis of ''H. heidelbergensis'' using the Mauer mandible, as well as material from Tighennif, Algeria; SH, Spain; Arago, France; and

In 2009, palaeontologists Aurélien Mounier, François Marchal and Silvana Condemi published the first differential diagnosis of ''H. heidelbergensis'' using the Mauer mandible, as well as material from Tighennif, Algeria; SH, Spain; Arago, France; and

Middle Pleistocene communities in general seem to have eaten big game at a higher frequency than predecessors, with meat becoming an essential dietary component. Diet could overall be varied—for example the inhabitants of Terra Amata seem to have been mainly eating deer, but also elephants, boar, ibex, rhino and aurochs. African sites typically commonly yield bovine and horse bones. Though carcasses may have simply been scavenged, some Afro-European sites show specific targeting of a single species, which more likely indicates active hunting; for example:

Middle Pleistocene communities in general seem to have eaten big game at a higher frequency than predecessors, with meat becoming an essential dietary component. Diet could overall be varied—for example the inhabitants of Terra Amata seem to have been mainly eating deer, but also elephants, boar, ibex, rhino and aurochs. African sites typically commonly yield bovine and horse bones. Though carcasses may have simply been scavenged, some Afro-European sites show specific targeting of a single species, which more likely indicates active hunting; for example:

Upper Palaeolithic modern humans are well known for having etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value. As of 2018, only 27 Middle and Lower Palaeolithic objects have been postulated to have symbolic etching, out of which some have been refuted as having been caused by natural or otherwise non-symbolic phenomena (such as the fossilisation or excavation processes). The Lower Palaeolithic ones are: three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; a 250,000-year-old pebble from

Upper Palaeolithic modern humans are well known for having etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value. As of 2018, only 27 Middle and Lower Palaeolithic objects have been postulated to have symbolic etching, out of which some have been refuted as having been caused by natural or otherwise non-symbolic phenomena (such as the fossilisation or excavation processes). The Lower Palaeolithic ones are: three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; a 250,000-year-old pebble from  In 2006, Eudald Carbonell and Marina Mosquera suggested the SH hominins were buried by people rather than being the victims of some catastrophic event such as a cave-in, because young children and infants are absent which would be unexpected if this were a single and complete family unit. The SH humans are conspicuously associated with only a single stone tool, a carefully crafted hand axe made of high-quality

In 2006, Eudald Carbonell and Marina Mosquera suggested the SH hominins were buried by people rather than being the victims of some catastrophic event such as a cave-in, because young children and infants are absent which would be unexpected if this were a single and complete family unit. The SH humans are conspicuously associated with only a single stone tool, a carefully crafted hand axe made of high-quality

The transition is indicated by the production of smaller, thinner, and more symmetrical hand axes (though thicker, less refined ones were still produced). At the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove site in England—an exceptionally well-preserved site with abundance of tool remains—thinning may have been produced by striking the hand axe near-perpendicularly with a soft hammer, possible with the invention of prepared platforms for tool making. The Boxgrove knappers also left behind large lithic flakes leftover from making hand axes, possibly with the intention of recycling them into other tools later. Late Acheulian sites elsewhere pre-prepared

The transition is indicated by the production of smaller, thinner, and more symmetrical hand axes (though thicker, less refined ones were still produced). At the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove site in England—an exceptionally well-preserved site with abundance of tool remains—thinning may have been produced by striking the hand axe near-perpendicularly with a soft hammer, possible with the invention of prepared platforms for tool making. The Boxgrove knappers also left behind large lithic flakes leftover from making hand axes, possibly with the intention of recycling them into other tools later. Late Acheulian sites elsewhere pre-prepared

The appearance of repeated fire usage—earliest in Europe from Beeches Pit, England, and Schöningen, Germany—roughly coincides with

The appearance of repeated fire usage—earliest in Europe from Beeches Pit, England, and Schöningen, Germany—roughly coincides with

Homo heidelbergensis

' – The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program

Homepage of Mauer 1 Club

UNESCO World Heritage Centre - Archaeological Site of Atapuerca

Human Timeline (Interactive)

– Smithsonian,

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

or subspecies of archaic human

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

which existed during the Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

. It was subsumed as a subspecies of ''H. erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor' ...

'' in 1950 as ''H. e. heidelbergensis'', but towards the end of the century, it was more widely classified as its own species. It is debated whether or not to constrain ''H. heidelbergensis'' to only Europe or to also include African and Asian specimens, and this is further confounded by the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

(Mauer 1

The Mauer 1 mandible is the oldest-known specimen of the genus ''Homo'' in Germany. It was found in 1907 in a sand quarry in the community Mauer, around south-east of Heidelberg. The Mauer 1 mandible is the type specimen of the species ''Homo h ...

) being a jawbone, because jawbones feature few diagnostic traits and are generally missing among Middle Pleistocene specimens. Thus, it is debated if some of these specimens could be split off into their own species or a subspecies of ''H. erectus''. Because the classification is so disputed, the Middle Pleistocene is often called the "muddle in the middle."

''H. heidelbergensis'' is regarded as a chronospecies

A chronospecies is a species derived from a sequential development pattern that involves continual and uniform changes from an extinct ancestral form on an evolutionary scale. The sequence of alterations eventually produces a population that is p ...

, evolving from an African form of ''H. erectus'' (sometimes called '' H. ergaster''). By convention, ''H. heidelbergensis'' is placed as the most recent common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

between modern humans (''H. sapiens'' or ''H. s. sapiens'') and Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

s (''H. neanderthalensis'' or ''H. s. neanderthalensis''). Many specimens assigned to ''H. heidelbergensis'' likely existed well after the modern human/Neanderthal split. In the Middle Pleistocene, brain size averaged about 1,200 cubic centimetre

A cubic centimetre (or cubic centimeter in US English) (SI unit symbol: cm3; non-SI abbreviations: cc and ccm) is a commonly used unit of volume that corresponds to the volume of a cube that measures 1 cm × 1 cm × 1 cm. One cub ...

s (cc), comparable to modern humans. Height in the Middle Pleistocene can only be estimated off remains from 3 localities: Sima de los Huesos, Spain, for males and for females; for a female from Jinniushan

Jinniushan () is a Middle Pleistocene paleoanthropological site, dating to around 260,000 BP, most famous for its archaic hominin fossils. The site is located near Yingkou, Liaoning, China. Several new species of extinct birds were also discovere ...

, China; and for a specimen from Kabwe

Kabwe is the capital of the Zambian Central Province and the Kabwe District, with a population estimated at 202,914 at the 2010 census. Named Broken Hill until 1966, it was founded when lead and zinc deposits were discovered in 1902. Kabwe also ...

, Zambia. Like Neanderthals, they had wide chests and were robust

Robustness is the property of being strong and healthy in constitution. When it is transposed into a system, it refers to the ability of tolerating perturbations that might affect the system’s functional body. In the same line ''robustness'' ca ...

overall.

The Middle Pleistocene of Africa and Europe features the advent of Late Acheulian technology, diverging from that of earlier and contemporary ''H. erectus'', and probably issuing from increasing intelligence. Fire likely became an integral part of daily life after 400,000 years ago, and this roughly coincides with more permanent and widespread occupation of Europe (above 45°N), and the appearance of hafting

Hafting is a process by which an artifact, often bone, stone, or metal is attached to a ''haft'' (handle or strap). This makes the artifact more useful by allowing it to be shot (arrow), thrown by hand (spear), or used with more effective levera ...

technology to create spears. ''H. heidelbergensis'' may have been able to carry out coordinated hunting strategies, and consequently they seem to have had a higher dependence on meat.

Taxonomy

Research history

The first fossil,Mauer 1

The Mauer 1 mandible is the oldest-known specimen of the genus ''Homo'' in Germany. It was found in 1907 in a sand quarry in the community Mauer, around south-east of Heidelberg. The Mauer 1 mandible is the type specimen of the species ''Homo h ...

(a jawbone), was discovered by a worker in Mauer

Mauer is the German word for ''wall''. It may also refer to:

Places

*Mauer, Vienna, a former village of Lower Austria that has been part of Vienna since 1938

* Mauer bei Amstetten, a village in the municipality of Amstetten, in Lower Austria

* M ...

, southeast of Heidelberg

Heidelberg (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: ''Heidlberg'') is a city in the States of Germany, German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Neckar in south-west Germany. As of the 2016 census, its population was 159,914 ...

, Germany, in 1907. It was formally described the next year by German anthropologist Otto Schoetensack, who made it the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

of a new species, ''Homo heidelbergensis''. He split this off as a new species primarily because of the mandible's archaicness—in particular its enormous size—and it was the then-oldest human jaw in the European fossil record at 640,000 years old. The mandible is well preserved, missing only the left premolars, part of the 1st left molar, the tip of the left coronoid process (at the jaw hinge), and fragments of the mid-section as the jaw was found in 2 pieces and had to be glued together. It may have belonged to a young adult based on slight wearing on the 3rd molar. In 1921, the skull Kabwe 1

Kabwe 1 (also called the Broken Hill skull, Rhodesian Man) is a Middle Paleolithic fossil assigned by Arthur Smith Woodward in 1921 as the type specimen for '' Homo rhodesiensis'', now mostly considered a synonym of ''Homo heidelbergensis''.Hubl ...

was discovered by Swiss miner Tom Zwiglaar in Kabwe

Kabwe is the capital of the Zambian Central Province and the Kabwe District, with a population estimated at 202,914 at the 2010 census. Named Broken Hill until 1966, it was founded when lead and zinc deposits were discovered in 1902. Kabwe also ...

, Zambia (at the time Broken Hill, Northern Rhodesia), and was assigned to a new species, "''H. rhodesiensis

''Homo rhodesiensis'' is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1 (the "Kabwe skull" or "Broken Hill skull", also "Rhodesian Man"), a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from a cave at Broken Hill, or Kabwe, ...

''", by English palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward

Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, FRS (23 May 1864 – 2 September 1944) was an English palaeontologist, known as a world expert in fossil fish. He also described the Piltdown Man fossils, which were later determined to be fraudulent. He is not relate ...

. These were two of the many putative species of Middle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

''Homo'' which were described throughout the first half of the 20th century. In the 1950s, Ernst Mayr had entered the field of anthropology, and, surveying a "bewildering diversity of names," decided to define only three species of ''Homo'': "''H. transvaalensis''" (the australopithecine

Australopithecina or Hominina is a subtribe in the tribe Hominini. The members of the subtribe are generally ''Australopithecus'' (cladistically including the genera ''Homo'', '' Paranthropus'', and ''Kenyanthropus''), and it typically includ ...

s), ''H. erectus

''Homo erectus'' (; meaning "upright man") is an extinct species of archaic human from the Pleistocene, with its earliest occurrence about 2 million years ago. Several human species, such as '' H. heidelbergensis'' and '' H. antecessor' ...

'' (including the Mauer mandible, and various putative African and Asian taxa) and ''Homo sapiens'' (including anything younger than ''H. erectus'', such as modern humans and Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While the ...

s). Mayr defined them as a sequential lineage, with each species evolving into the next (chronospecies

A chronospecies is a species derived from a sequential development pattern that involves continual and uniform changes from an extinct ancestral form on an evolutionary scale. The sequence of alterations eventually produces a population that is p ...

). Though later Mayr changed his opinion on the australopithecines (recognising ''Australopithecus

''Australopithecus'' (, ; ) is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Late Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genus ''Homo'' (which includes modern humans) emerged within ''Australopithecus'', as sister to e.g. ''Austral ...

''), his more conservative view of archaic human

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

diversity became widely adopted in the subsequent decades.

Though ''H. erectus'' is still maintained as a highly variable, widespread and long-lasting species, it is still much debated whether or not sinking all Middle Pleistocene remains into it is justifiable. Mayr's lumping of ''H. heidelbergensis'' was first opposed by American anthropologist

Though ''H. erectus'' is still maintained as a highly variable, widespread and long-lasting species, it is still much debated whether or not sinking all Middle Pleistocene remains into it is justifiable. Mayr's lumping of ''H. heidelbergensis'' was first opposed by American anthropologist Francis Clark Howell

Francis Clark Howell (November 27, 1925 – March 10, 2007), generally known as F. Clark Howell, was an American anthropologist.

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, F. Clark Howell grew up in Kansas, where he became interested in natural history. H ...

in 1960. In 1974, British physical anthropologist Chris Stringer pointed out similarities between the Kabwe 1 and the Greek Petralona skulls to the skulls of modern humans (''H. sapiens'' or ''H. s. sapiens'') and Neanderthals (''H. neanderthalensis'' or ''H. s. neanderthalensis''). So, Stringer assigned them to ''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

sensu lato

''Sensu'' is a Latin word meaning "in the sense of". It is used in a number of fields including biology, geology, linguistics, semiotics, and law. Commonly it refers to how strictly or loosely an expression is used in describing any particular c ...

'' ("in the broad sense"), as ancestral to modern humans and Neanderthals. In 1979, Stringer and Finnish anthropologist Björn Kurtén Björn Olof Lennartson Kurtén (19 November 1924 – 28 December 1988) was a Finnish vertebrate paleontologist, belonging to the Swedish-speaking minority of his country.

Early life and education

Kurtén was born in Vaasa.

Career

He was a profe ...

found that the Kabwe and Petralona skulls are associated with the Cromerian The Cromerian Stage or Cromerian Complex, also called the Cromerian (german: Cromerium), is a stage in the Pleistocene glacial history of north-western Europe, mostly occurring more than half a million years ago. It is named after the East Anglian t ...

industry

Industry may refer to:

Economics

* Industry (economics), a generally categorized branch of economic activity

* Industry (manufacturing), a specific branch of economic activity, typically in factories with machinery

* The wider industrial sector ...

like the Mauer mandible, and thus postulated these three populations might be allied with each other. Though these fossils are poorly preserved and do not provide many comparable possible diagnostic traits (and likewise it was difficult at the time to properly define a unique species), they argued that at least these Middle Pleistocene specimens should be allocated to ''H. (s.?) heidelbergensis'' or "''H. (s.?) rhodesiensis''" (depending on, respectively, the inclusion or exclusion of the Mauer mandible) to formally recognise their similarity.

Further work most influentially by Stringer, palaeoanthropologist Ian Tattersall

Ian Tattersall (born 1945) is a British-born American paleoanthropologist and a curator emeritus with the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, New York. In addition to human evolution, Tattersall has worked extensively with lemur ...

, and human evolutionary biologist Phillip Rightmire reported further differences between Middle Pleistocene Afro-European specimens and ''H. erectus'' '' sensu stricto'' ("in the strict sense", in this case specimens from East Asia). Consequently, Afro-European remains from 600 to 300 thousand years ago—most notably from Kabwe, Petralona, Bodo Bodo may refer to:

Ethnicity

* Boro people, an ethno-linguistic group mainly from Northwest Assam, India

* Bodo-Kachari people, an umbrella group from Nepal, India and Bangladesh that includes the Bodo people

Culture and language

* Boro cu ...

and Arago—are often classified as ''H. heidelbergensis''. In 2010, American physical anthropologist Jeffrey H. Schwartz and Tattersall suggested classifying all Middle Pleistocene European as well as Asian specimens—namely from Dali and Jinniushan

Jinniushan () is a Middle Pleistocene paleoanthropological site, dating to around 260,000 BP, most famous for its archaic hominin fossils. The site is located near Yingkou, Liaoning, China. Several new species of extinct birds were also discovere ...

in China—as ''H. heidelbergensis''. This model is not as universally accepted. After the 2010 identification of the genetic code of some unique archaic human species in Siberia, termed "Denisovan

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins ) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic. Denisovans are known from few physical remains and consequently, most of what is known ...

s" pending diagnostic fossil finds, it is postulated that the Asian remains could represent that same species. Thus, Middle Pleistocene Asian specimens, such as Dali Man or the Indian Narmada Man, remain enigmatic. The palaeontology institute at Heidelberg University

}

Heidelberg University, officially the Ruprecht Karl University of Heidelberg, (german: Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg; la, Universitas Ruperto Carola Heidelbergensis) is a public university, public research university in Heidelberg, B ...

, where the Mauer mandible has been kept since 1908, changed the label from ''H. e. heidelbergensis'' to ''H. heidelbergensis'' in 2015.

In 1976 at Sima de los Huesos (SH) in the

In 1976 at Sima de los Huesos (SH) in the Sierra de Atapuerca

The Atapuerca Mountains ( es, Sierra de Atapuerca) is a karstic hill formation near the village of Atapuerca in the province of Burgos (autonomous community of Castile and Leon), northern Spain.

In a still ongoing excavation campaign, rich fos ...

, Spain, Spanish palaeontologists Emiliano Aguirre

Emiliano Aguirre Enríquez (5 October 1925 – 11 October 2021) was a Spanish paleontologist, known for his works at archaeological site of Atapuerca, whose excavations he directed from 1978 until his retirement in 1990. He received the Princ ...

, José María Basabe and Trinidad Torres began to excavate archaic human remains. Their investigation of the site was prompted by the finding of several bear remains (''Ursus deningeri

''Ursus deningeri'' (Deninger's bear) is an extinct species of bear, endemic to Eurasia during the Pleistocene for approximately 1.7 million years, from .

The range of this bear has been found to encompass both Europe and Asia, demonstrating the ...

'') since the early 20th century by amateur cavers (which consequently destroyed some of the human remains in that section). By 1990, about 600 human remains were reported, and by 2004 the number had increased to roughly 4,000. These represent at least 28 individuals, of which possibly only one is a child, and the rest teenagers and young adults. The fossil assemblage is exceptionally complete, with whole corpses buried rapidly, with all bodily elements represented. In 1997, Spanish palaeoanthropologist Juan Luis Arsuaga

Juan Luis Arsuaga Ferreras (born 1954 in Madrid) is a Spanish paleoanthropologist and author known for his work in the Atapuerca Archaeological Site.

He obtained a master's degree and a doctorate in Biological Sciences at the Universidad Comp ...

assigned these to ''H. heidelbergensis'', but in 2014, he retracted this, stating that Neanderthal-like features present in the Mauer mandible are missing in the SH humans.

Classification

In palaeoanthropology, theMiddle Pleistocene

The Chibanian, widely known by its previous designation of Middle Pleistocene, is an age in the international geologic timescale or a stage in chronostratigraphy, being a division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. Th ...

is often termed the "muddle in the middle" because the species-level classification of archaic human

A number of varieties of '' Homo'' are grouped into the broad category of archaic humans in the period that precedes and is contemporary to the emergence of the earliest early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') around 300 ka. Omo-Kibish I (Omo I) f ...

remains from this time period has been heavily debated. The ancestors of modern humans (''Homo sapiens'' or ''H. s. sapiens'') and Neanderthals (''H. neanderthalensis'' or ''H. s. neanderthalensis'') diverged during this time period, and, by convention, ''H. heidelbergensis'' is typically considered the last common ancestor

In biology and genetic genealogy, the most recent common ancestor (MRCA), also known as the last common ancestor (LCA) or concestor, of a set of organisms is the most recent individual from which all the organisms of the set are descended. The ...

(LCA). This would make ''H. heidelbergensis'' a member of a chronospecies

A chronospecies is a species derived from a sequential development pattern that involves continual and uniform changes from an extinct ancestral form on an evolutionary scale. The sequence of alterations eventually produces a population that is p ...

. It is much debated if the name ''H. heidelbergensis'' can be extended to Middle Pleistocene humans across the Old World, or if it is better to restrict it to just Europe. In the latter case, Middle Pleistocene African remains can be split off into "''H. rhodesiensis''". In the latter view, "''H. rhodesiensis''" can either be seen as the direct ancestor of modern humans, or of "'' H. helmei''" which evolved into modern humans.

Regarding the Middle Pleistocene European remains, some are more firmly placed on the Neanderthal line (namely SH, Pontnewyyd, Steinheim, and Swanscombe), whereas others seem to have few uniquely Neanderthal features (Arago, Ceprano Ceprano (Central-Northern Latian dialect: ) is a town and ''comune'' in the province of Frosinone, in the Latin Valley, part of the Lazio region of central Italy.

It is south of Rome and about north of Naples.

History

Ceprano was part of the Pa ...

, Vértesszőlős

Vértesszőlős is a village in Komárom-Esztergom county, Hungary. It is most known for the archaeological site where a Middle Pleistocene human fossil, known as "Samu (fossil), Samu", was found.

History Prehistory

Vértesszőlős sits at the ...

, Bilzingsleben, Mala Balanica and Aroeira

''Schinus terebinthifolia'' is a species of flowering plant in the cashew family, Anacardiaceae, that is native to subtropical and tropical South America. Common names include Brazilian peppertree, aroeira, rose pepper, broadleaved pepper tree, ...

). Because of this, it is suggested there were multiple lineages (or species) in this region and time period, but French palaeoanthropologist Jean-Jacques Hublin

Jean-Jacques Hublin (born 30 November 1953) is a French paleoanthropologist. He is a professor at the Max Planck Society, Leiden University and the University of Leipzig and the founder and director of the Department of Human Evolution at the ...

considers this an unjustified extrapolation as they may have simply been different but still interconnected populations of a single, highly variable species. In 2015, Marie Antoinette de Lumley suggested the less derived material can also be split off into their own species or a subspecies of ''H. erectus s. l.'' (for example, the Arago material as "''H. e. tautavelensis''"). In 2018, Mirjana Roksandic and colleagues revised the hypodigm of ''H. heidelbergensis'' to include only the specimens with no Neanderthal-derived traits (namely Mauer, Mala Balanica, Ceprano, HaZore'a and Nadaouiyeh Aïn Askar). There is no defined distinction between latest potential ''H. heidelbergensis'' material – specifically Steinheim and SH – and the earliest Neanderthal specimens— Biache, France; Ehringsdorf, Germany; or Saccopastore, Italy.

The use of the Mauer mandible, an isolated jawbone, as the type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally attached. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes th ...

for the species has been problematic as it does not present many diagnostic features, and in addition it is missing from several Middle Pleistocene specimens. Anthropologist William Straus said on this topic that, "While the skull is the creation of God, the jaw is the work of the devil." If the Mauer mandible is actually a member of a different species than the Kabwe skull and most other Afro-European Middle Pleistocene archaic humans, then "''H. rhodesiensis''" would take priority as the name of the LCA.

In 2021, Canadian anthropologist Mirjana Roksandic and colleagues recommended the complete dissolution of ''H. heidelbergensis'' and "''H. rhodesiensis''", as the name ''rhodesiensis'' honours English diamond magnate Cecil Rhodes who disenfranchised the black population in southern Africa. They classified all European ''H. heidelbergensis'' as ''H. neanderthalensis'', and synonymised ''H. rhodesiensis'' with a new species they named "'' H. bodoensis''" which includes all African specimens, and potentially some from the Levant and the Balkans which have no Neanderthal-derived traits (namely Ceprano, Mala Balanica, HaZore'a and Nadaouiyeh Aïn Askar). ''H. bodoensis'' is supposed to represent the immediate ancestor of modern humans, but does not include the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthals. They suggested the confusing morphology of the Middle Pleistocene was caused by periodic ''H. bodoensis'' migration events into Europe following population collapses after glacial cycles, interbreeding with surviving indigenous populations. Their taxonomic recommendations were rejected by Stringer and others as they failed to explain how exactly their proposals would resolve anything, in addition to violating nomenclatural rules.

Evolution

''H. heidelbergensis'' is thought to have descended from African ''H. erectus'' — sometimes classified as ''Homo ergaster

''Homo ergaster'' is an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Africa in the Early Pleistocene. Whether ''H. ergaster'' constitutes a species of its own or should be subsumed into '' H. erectus'' is an ongoing and unresol ...

'' — during the first early expansions of hominins out of Africa

Several expansions of populations of archaic humans (genus ''Homo'') out of Africa and throughout Eurasia took place in the course of the Lower Paleolithic, and into the beginning Middle Paleolithic, between about 2.1 million and 0.2 million ...

beginning roughly 2 million years ago. Those that dispersed across Europe and stayed in Africa evolved into ''H. heidelbergensis'' or speciated into ''H. heidelbergensis'' in Europe and "''H. rhodesiensis''" in Africa, and those that dispersed across East Asia evolved into ''H. erectus s. s.'' The exact derivation from an ancestor species is obfuscated by a long gap in the human fossil record near the end of the Early Pleistocene.Convenience link

In 2016, Antonio Profico and colleagues suggested that 875,000-year-old skull materials from the Gombore II site of the

Melka Kunture

Melka Kunture (መልካ ቁንጥሬ) is a Paleolithic site in the upper Awash Valley, Ethiopia. It is located 50 kilometers south of Addis Ababa by road, across the Awash River from the village of Melka Awash. Three waterfalls lie downstream of ...

Formation, Ethiopia, represent a transitional morph between ''H. ergaster'' and ''H. heidelbergensis'', and thus postulated that ''H. heidelbergensis'' originated in Africa instead of Europe.

According to genetic analysis, the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthal split into a modern human line, and a Neanderthal/Denisovan line, and the latter later split into Neanderthal and Denisovans. According to

According to genetic analysis, the LCA of modern humans and Neanderthal split into a modern human line, and a Neanderthal/Denisovan line, and the latter later split into Neanderthal and Denisovans. According to nuclear DNA

Nuclear DNA (nDNA), or nuclear deoxyribonucleic acid, is the DNA contained within each cell nucleus of a eukaryotic organism. It encodes for the majority of the genome in eukaryotes, with mitochondrial DNA and plastid DNA coding for the rest. I ...

analysis, the 430,000-year-old SH humans are more closely related to Neanderthals than Denisovans (and that the Neanderthal/Denisovan, and thus the modern human/Neanderthal split, had already occurred), suggesting the modern human/Neanderthal LCA had existed long before many European specimens typically assigned to ''H. heidelbergensis'' did, such as the Arago and Petralona materials.

In 1997, Spanish archaeologist , Arsuaga, and colleagues described the roughly million-year-old ''H. antecessor

''Homo antecessor'' (Latin "pioneer man") is an extinct species of archaic human recorded in the Spanish Sierra de Atapuerca, a productive archaeological site, from 1.2 to 0.8 million years ago during the Early Pleistocene. Populations of thi ...

'' from Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, and suggested supplanting this species in the place of ''H. heidelbergensis'' for the LCA between modern humans and Neanderthals, with ''H. heidelbergensis'' descending from it and being a strictly European species ancestral to only Neanderthals. They later recanted. In 2020, Dutch molecular palaeoanthropologist Frido Welker and colleagues analysed ancient proteins collected from an ''H. antecessor'' tooth found that it was a member of a sister lineage to the LCA rather than being the LCA itself (that is, ''H. heidelbergensis'' did not derive from ''H. antecessor'').

Human dispersal beyond 45°N seems to have been quite limited during the Lower Palaeolithic

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears ...

, with evidence of short-lived dispersals northward beginning after a million years ago. Beginning 700,000 years ago, more permanent populations seem to have persisted across the line coinciding with the spread of hand axe

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history, yet there is no academic consensus on what they were used for. It is made from stone, usually flint or ch ...

technology across Europe, possibly associated with the dispersal of ''H. heidelbergensis'' and behavioural shifts to cope with the cold climate. Such occupation becomes much more frequent after 500,000 years ago.

Anatomy

Skull

In comparison to Early Pleistocene ''H. erectus''/''ergaster'', Middle Pleistocene humans have a much more modern human-like face. The nasal opening is set completely vertically in the skull, and the anterior nasal sill can be crested or sometimes a prominent spine. The incisive canals (on the roof of the mouth) open near the teeth, and are orientated like those of more recent human species. The

In comparison to Early Pleistocene ''H. erectus''/''ergaster'', Middle Pleistocene humans have a much more modern human-like face. The nasal opening is set completely vertically in the skull, and the anterior nasal sill can be crested or sometimes a prominent spine. The incisive canals (on the roof of the mouth) open near the teeth, and are orientated like those of more recent human species. The frontal bone

The frontal bone is a bone in the human skull. The bone consists of two portions.'' Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bony part of the forehead, pa ...

is broad, the parietal bone

The parietal bones () are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint, form the sides and roof of the cranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, and four angles. It is nam ...

can be expanded, and the squamous part of temporal bone

The squamous part of temporal bone, or temporal squama, forms the front and upper part of the temporal bone, and is scale-like, thin, and translucent.

Surfaces

Its outer surface is smooth and convex; it affords attachment to the temporal muscle ...

is high and arched, which could all be related to increasing brain size. The sphenoid bone features a spine extending downwards, and the articular tubercle

The articular tubercle (eminentia articularis) is a bony eminence on the temporal bone in the skull. It is a rounded eminence of the anterior root of the posterior end of the outer surface of the squama temporalis. This tubercle forms the front bou ...

on the underside of the skull can jut out prominently as the surface behind the jaw hinge is otherwise quite flat.

In 2004, Rightmire estimated the brain volumes of ten Middle Pleistocene humans variously attributable to ''H. heidelbergensis''—from Kabwe, Bodo, Ndutu, Dali, Jinniushan, Petralona, Steinheim, Arago, and two from SH. This set gives an average volume of about 1,206 cc, ranging from 1,100 to 1,390 cc. He also averaged the brain volumes of 30 ''H. erectus''/''ergaster'' specimens, spanning nearly 1.5 million years from across East Asia and Africa, as 973 cc, and thus concluded a significant jump in brain size, though conceded brain size was extremely variable ranging from 727 to 1,231 cc depending on the time period, geographic region, and even between individuals within the same population (the last one probably due to notable sexual dimorphism with males much bigger than females). In comparison, for modern humans, brain size averages 1,270 cc for males and 1,130 cc for females; and for Neanderthals 1,600 cc for males and 1,300 cc for females.

In 2009, palaeontologists Aurélien Mounier, François Marchal and Silvana Condemi published the first differential diagnosis of ''H. heidelbergensis'' using the Mauer mandible, as well as material from Tighennif, Algeria; SH, Spain; Arago, France; and

In 2009, palaeontologists Aurélien Mounier, François Marchal and Silvana Condemi published the first differential diagnosis of ''H. heidelbergensis'' using the Mauer mandible, as well as material from Tighennif, Algeria; SH, Spain; Arago, France; and Montmaurin

Montmaurin () is a commune in the Haute-Garonne department of southwestern France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territori ...

, France. They listed the diagnostic traits as: a reduced chin, a notch in the submental space (near the throat), parallel upper and lower boundaries of the mandible in side-view, several mental foramina

The mental foramen is one of two foramina (openings) located on the anterior surface of the mandible. It is part of the mandibular canal. It transmits the terminal branches of the inferior alveolar nerve and the mental vessels.

Structure

The ...

(small holes for blood vessels) near the cheek teeth, a horizontal retromolar space (a gap behind the molars), a gutter between the molars and the ramus (which juts up to connect with the skull), an overall long jaw, a deep fossa (a depression) for the masseter muscle

In human anatomy, the masseter is one of the muscles of mastication. Found only in mammals, it is particularly powerful in herbivores to facilitate chewing of plant matter. The most obvious muscle of mastication is the masseter muscle, since it ...

(which closes the jaw), a small gonial angle (the angle between the body of the mandible and the ramus), an extensive planum alveolare (the distance from the frontmost tooth socket to the back of the jaw), a developed planum triangulare (near the jaw hinge), and a mylohyoid line

The mylohyoid line is a bony ridge on the internal surface of the mandible. It runs posterosuperiorly. It is the site of origin of the mylohyoid muscle, the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, and the pterygomandibular raphe.

Structure

The ...

originating at the level of the third molar.

Size

Trends in body size through the Middle Pleistocene are obscured due to a general lack of limb bones and non-skull (post-cranial) remains. Based on the lengths of various long bones, the SH humans averaged roughly for males and for females, with maximums of respectively and . The height of a female partial skeleton from Jinniushan is estimated to have been quite tall at roughly in life, much taller than the SH females. A tibia from Kabwe is typically estimated to have been , among the tallest Middle Pleistocene specimens, but it is possible this individual was either unusually large or had a much longer tibia tofemur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

ratio than expected.

If these specimens are representative of their respective continents, they would suggest that above-medium to tall people were prevalent throughout the Middle Pleistocene Old World. If this is the case, then most all populations of any archaic human species would have generally averaged to in height. Early modern humans were notably taller, with the Skhul and Qafzeh remains averaging for males and for females, an average of , possibly to increase the energy-efficiency of long-distance travel with longer legs.

A conspicuously massive proximal (upper half) femur was recovered from Berg Aukas Mine, Namibia, about east of Grootfontein

, nickname =

, settlement_type = City

, motto = Fons Vitæ

, image_skyline = Grootfontein grass.jpg

, imagesize = 300px

, image_caption =

, image_flag =

, flag_si ...

. It was originally estimated to have been from a male as much as in life, but its exorbitant size is now proposed to be the consequence of an extraordinarily vigorous early-life activity level while an otherwise ordinary person was maturing. If so, the individual from the Berg Aukas Mine would probably have had proportions similar to Kabwe 1.

Build

The humanbody plan

A body plan, ( ), or ground plan is a set of morphological features common to many members of a phylum of animals. The vertebrates share one body plan, while invertebrates have many.

This term, usually applied to animals, envisages a "blueprin ...

had evolved in ''H. ergaster'', and characterises all later ''Homo'' species, but among the more derived members there are 2 distinct morphs: A narrow-chested and gracile build like modern humans, and a broader-chested and robust build like Neanderthals. It was once assumed that the Neanderthal build was unique to Neanderthals based on the gracile ''H. ergaster'' partial skeleton "KNM WT-15000" ("Turkana Boy

Turkana Boy, also called Nariokotome Boy, is the name given to fossil KNM-WT 15000, a nearly complete skeleton of a ''Homo ergaster'' youth who lived 1.5 to 1.6 million years ago. This specimen is the most complete early hominin skeleton ever ...

"), but the discovery of some Middle Pleistocene skeletal elements (though generally fragmentary and few and far between) seems to suggest Middle Pleistocene humans overall featured a more Neanderthal morph. Thus, the modern human morph may be unique to modern humans, evolving quite recently. This is most clearly demonstrated in the exceptionally well-preserved SH assemblage. Based on skull robustness, it was assumed Middle Pleistocene humans featured a high degree of sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

, but the SH humans demonstrate a modern humanlike level.

The SH humans and other Middle Pleistocene ''Homo'' have a more basal pelvis and femur (more similar to earlier ''Homo'' than Neanderthals). The overall broad and elliptical pelvis is broader, taller and thicker (expanded anteroposteriorly) than those of Neanderthals or modern humans, and retains an anteriorly located acetabulocristal buttress (which supports the iliac crest

The crest of the ilium (or iliac crest) is the superior border of the wing of ilium and the superiolateral margin of the greater pelvis.

Structure

The iliac crest stretches posteriorly from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the poster ...

s during hip abduction), a well defined supraacetabular groove (between the hip socket and the ilium), and a thin and rectangular superior pubic ramus

In vertebrates, the pubic region ( la, pubis) is the most forward-facing (ventral and anterior) of the three main regions making up the coxal bone. The left and right pubic regions are each made up of three sections, a superior ramus, inferior r ...

(as opposed to the thick, stout one in modern humans). The foot of all archaic humans has a taller trochlea of the ankle bone, making the ankle more flexible (specifically dorsiflexion and plantarflexion).

Pathology

On the left side of its face, an SH skull ( Skull 5) presents the oldest-known case oforbital cellulitis

Orbital cellulitis is inflammation of eye tissues behind the orbital septum. It is most commonly caused by an acute spread of infection into the eye socket from either the adjacent sinuses or through the blood. It may also occur after trauma. W ...

(eye infection which developed from an abscess in the mouth). This probably caused sepsis

Sepsis, formerly known as septicemia (septicaemia in British English) or blood poisoning, is a life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs. This initial stage is follo ...

, killing the individual.

A male SH pelvis (Pelvis 1), based on joint degeneration, may have lived for more than 45 years, making him one of the oldest examples of this demographic in the human fossil record. The frequency of 45-plus individuals gradually increases with time, but has overall remained quite low throughout the Palaeolithic. He similarly had the age-related maladies lumbar kyphosis

Kyphosis is an abnormally excessive convex curvature of the spine as it occurs in the thoracic and sacral regions. Abnormal inward concave ''lordotic'' curving of the cervical and lumbar regions of the spine is called lordosis. It can result ...

(excessive curving of the lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are, in human anatomy, the five vertebrae between the rib cage and the pelvis. They are the largest segments of the vertebral column and are characterized by the absence of the foramen transversarium within the transverse p ...

of the lower back), L5–S1 spondylolisthesis

Spondylolisthesis is the displacement of one spinal vertebra compared to another. While some medical dictionaries define spondylolisthesis specifically as the forward or anterior displacement of a vertebra over the vertebra inferior to it (or t ...

(misalignment of the last lumbar vertebra with the first sacral vertebra

The sacrum (plural: ''sacra'' or ''sacrums''), in human anatomy, is a large, triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part ...

), and Baastrup disease on L4 and 5 (enlargement of the spinous processes). These would have produced lower back pain, significantly limiting movement, and may be evidence of group care.

An adolescent SH skull (Cranium 14) was diagnosed with lambdoid single suture craniosynostosis (immature closing of the left lambdoid suture

The lambdoid suture (or lambdoidal suture) is a dense, fibrous connective tissue joint on the posterior aspect of the skull that connects the parietal bones with the occipital bone. It is continuous with the occipitomastoid suture.

Structure

T ...

, leading to skull deformities as development continued). This is a rare condition, occurring in less than 6 out of every 200,000 individuals in modern humans. The individual died around the age of 10, suggesting it was not abandoned due its deformity as has been done in historical times, and received the same quality of care as any other child.

Enamel hypoplasia

Enamel hypoplasia is a defect of the teeth in which the enamel is deficient in quantity, caused by defective enamel matrix formation during enamel development, as a result of inherited and acquired systemic condition(s). It can be identified as m ...

on the teeth is used to determine bouts of nutritional stress. At a rate of 40% for the SH humans, this is significantly higher than exhibited in the earlier South African hominin

The Hominini form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae ("hominines"). Hominini includes the extant genera ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos) and in standard usage excludes the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas).

The ...

'' Paranthropus robustus'' at Swartkrans

Swartkrans is a fossil-bearing cave designated as a South African National Heritage Site, located about from Johannesburg. It is located in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site and is notable for being extremely rich in archaeological ma ...

(30.6%) or Sterkfontein (12.1%). Nonetheless, Neanderthals suffered even higher rates and more intense bouts of hypoplasia, but it is unclear if this is because Neanderthals were less capable of exploiting natural resources, or because they lived in harsher environments. A peak at 3½ years of age may be correlated with weaning age. In Neanderthals this peak was at 4 years, and many modern hunter gatherers also wean at about 4 years of age.

Culture

Food

Middle Pleistocene communities in general seem to have eaten big game at a higher frequency than predecessors, with meat becoming an essential dietary component. Diet could overall be varied—for example the inhabitants of Terra Amata seem to have been mainly eating deer, but also elephants, boar, ibex, rhino and aurochs. African sites typically commonly yield bovine and horse bones. Though carcasses may have simply been scavenged, some Afro-European sites show specific targeting of a single species, which more likely indicates active hunting; for example:

Middle Pleistocene communities in general seem to have eaten big game at a higher frequency than predecessors, with meat becoming an essential dietary component. Diet could overall be varied—for example the inhabitants of Terra Amata seem to have been mainly eating deer, but also elephants, boar, ibex, rhino and aurochs. African sites typically commonly yield bovine and horse bones. Though carcasses may have simply been scavenged, some Afro-European sites show specific targeting of a single species, which more likely indicates active hunting; for example: Olorgesailie

Olorgesailie is a geological formation in East Africa, on the floor of the Eastern Rift Valley in southern Kenya, southwest of Nairobi along the road to Lake Magadi. It contains a group of Lower Paleolithic archaeological sites. Olorgesaili ...

, Kenya, which has yielded over 50 to 60 individual baboons (''Theropithecus oswaldi

''Theropithecus oswaldi'' is an extinct species of '' Theropithecus'' from the early to middle Pleistocene of Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, South Africa, Spain, Morocco and Algeria. It appears to have been a specialised grazer. The species went exti ...

''); and Torralba and Ambrona in Spain which have an abundance of elephant bones (though also rhino and large hoofed mammals). The increase in meat subsistence could indicate the development of group hunting strategies in the Middle Pleistocene. For instance, at Torralba and Ambrona, the animals may have been run into swamplands before being killed, entailing encircling and driving by a large group of hunters in a coordinated and organised attack. Exploitation of aquatic environments is generally quite lacking, despite some sites being in close proximity to the ocean, lakes or rivers.

Plants were probably also frequently consumed, including seasonally available ones, but the extent of their exploitation is unclear as they do not fossilise as well as animal bones. Assuming a diet heavy in lean meat, an individual would have needed a high carbohydrate

In organic chemistry, a carbohydrate () is a biomolecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, usually with a hydrogen–oxygen atom ratio of 2:1 (as in water) and thus with the empirical formula (where ''m'' may or m ...

intake to prevent protein poisoning, such as by eating typically abundant underground storage organs, tree bark, berries, or nuts. The Schöningen

Schöningen is a town of about 11,000 inhabitants in the district of Helmstedt, in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Geography

The town is located on the southeastern rim of the Elm hill range, near the border with the state of Saxony-Anhalt. In its curren ...

site, Germany, has over 200 plants in the vicinity which are either edible raw or when cooked.

Art

Upper Palaeolithic modern humans are well known for having etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value. As of 2018, only 27 Middle and Lower Palaeolithic objects have been postulated to have symbolic etching, out of which some have been refuted as having been caused by natural or otherwise non-symbolic phenomena (such as the fossilisation or excavation processes). The Lower Palaeolithic ones are: three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; a 250,000-year-old pebble from

Upper Palaeolithic modern humans are well known for having etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value. As of 2018, only 27 Middle and Lower Palaeolithic objects have been postulated to have symbolic etching, out of which some have been refuted as having been caused by natural or otherwise non-symbolic phenomena (such as the fossilisation or excavation processes). The Lower Palaeolithic ones are: three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; a 250,000-year-old pebble from Markkleeberg

Markkleeberg is an affluent suburb of Leipzig (district), Leipzig, located in the Leipzig (district), Leipzig district of the Saxony, Free State of Saxony, Germany. The river Pleiße runs through the city, which borders Leipzig to the north and t ...

, Germany; 18 roughly 200,000-year-old pebbles from Lazaret

A lazaretto or lazaret (from it, lazzaretto a diminutive form of the Italian word for beggar cf. lazzaro) is a quarantine station for maritime travellers. Lazarets can be ships permanently at anchor, isolated islands, or mainland buildings. ...

(near Terra Amata); a roughly 200,000-year-old lithic from Grotte de l'Observatoire, Monaco; a 370,000-year-old bone from Bilzingsleben, Germany; and a 200- to 130-thousand-year-old pebble from Baume Bonne, France.

In the mid-19th century, French archaeologist Jacques Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes

Jacques Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes (; 10 September 1788 – 5 August 1868), sometimes referred to as Boucher de Perthes ( ), was a French archaeologist and antiquary notable for his discovery, in about 1830, of flint tools in the gravels of ...

began excavation at St. Acheul, Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

, France, (the area where the Acheulian was defined), and, in addition to hand axes, reported perforated sponge fossils (''Porosphaera globularis'') which he considered to have been decorative beads. This claim was completely ignored. In 1894, English archaeologist Worthington George Smith

Worthington George Smith (25 March 1835 – 27 October 1917) was an English cartoonist and illustrator, archaeologist, plant pathologist, and mycologist.

Background and career

Worthington G. Smith was born in Shoreditch, London, the son of a ...

discovered 200 similar perforated fossils in Bedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council ...

, England, and also speculated that their function was beads, though he made no reference to Boucher de Perthes' find, possibly because he was unaware of it. In 2005, Robert Bednarik reexamined the material, and concluded that—because all the Bedfordshire ''P. globularis'' fossils are sub-spherical and range in diameter, despite this species having a highly variable shape—they were deliberately chosen. They appear to have been bored through completely or almost completely by some parasitic creature (i. e., through natural processes), and were then percussed on what would have been the more closed-off end to fully open the hole. He also found wear facets which he speculated were begotten from clacking against other beads when they were strung together and worn as a necklace. In 2009, Solange Rigaud, Francisco d'Errico and colleagues noticed that the modified areas are lighter in colour than the unmodifed, suggesting they were inflicted much more recently such as during excavation. They were also unconvinced that the fossils could be confidently associated with the Acheulian artefacts from the sites, and suggested that—as an alternative to archaic human activity—apparent size-selection could have been caused by either natural geological processes or 19th-century collectors favouring this specific form.

Early modern humans and late Neanderthals (the latter especially after 60,000 years ago) made wide use of red ochre for presumably symbolic purposes as it produces a blood-like colour, though ochre can also have a functional medicinal application. Beyond these two species, ochre usage is recorded at Olduvai Gorge

The Olduvai Gorge or Oldupai Gorge in Tanzania is one of the most important paleoanthropological localities in the world; the many sites exposed by the gorge have proven invaluable in furthering understanding of early human evolution. A steep-si ...

, Tanzania, where two red ochre lumps have been found; Ambrona where an ochre slab was trimmed down into a specific shape; and Terra Amata where 75 ochre pieces were heated to achieve a wide colour range from yellow to red-brown to red. These may exemplify early and isolated instances of colour preference and colour categorisation, and such practices may not have been normalised yet.

In 2006, Eudald Carbonell and Marina Mosquera suggested the SH hominins were buried by people rather than being the victims of some catastrophic event such as a cave-in, because young children and infants are absent which would be unexpected if this were a single and complete family unit. The SH humans are conspicuously associated with only a single stone tool, a carefully crafted hand axe made of high-quality

In 2006, Eudald Carbonell and Marina Mosquera suggested the SH hominins were buried by people rather than being the victims of some catastrophic event such as a cave-in, because young children and infants are absent which would be unexpected if this were a single and complete family unit. The SH humans are conspicuously associated with only a single stone tool, a carefully crafted hand axe made of high-quality quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock which was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tec ...

(rarely used in the region), and so Carbonell and Mosquera postulated this was purposefully and symbolically placed with the bodies as some kind of grave good. Supposed evidence of symbolic graves would not surface for another 300,000 years.

Technology

Stone tools

The Lower Palaeolithic (Early Stone Age) comprises theOldowan

The Oldowan (or Mode I) was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower ...

which was replaced by the Acheulian, which is characterised by the production of mostly symmetrical hand axe

A hand axe (or handaxe or Acheulean hand axe) is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history, yet there is no academic consensus on what they were used for. It is made from stone, usually flint or ch ...

s. The Acheulian has a timespan of about a million years, and such technological stagnation has typically been ascribed to comparatively limited cognitive abilities which significantly reduced innovative capacity, such as a deficit in cognitive fluidity, working memory

Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, ...

, or a social system compatible with apprenticeship. Nonetheless, the Acheulian does seem to subtly change over time, and is typically split up into Early Acheulian and Late Acheulian, the latter becoming especially popular after 600 to 500 thousand years ago. Late Acheulian technology never crossed over east of the Movius Line into East Asia, which is generally believed to be due to either some major deficit in cultural transmission (namely smaller population size in the East) or simply preservation bias as far fewer stone tool assemblages are found east of the line.

The transition is indicated by the production of smaller, thinner, and more symmetrical hand axes (though thicker, less refined ones were still produced). At the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove site in England—an exceptionally well-preserved site with abundance of tool remains—thinning may have been produced by striking the hand axe near-perpendicularly with a soft hammer, possible with the invention of prepared platforms for tool making. The Boxgrove knappers also left behind large lithic flakes leftover from making hand axes, possibly with the intention of recycling them into other tools later. Late Acheulian sites elsewhere pre-prepared

The transition is indicated by the production of smaller, thinner, and more symmetrical hand axes (though thicker, less refined ones were still produced). At the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove site in England—an exceptionally well-preserved site with abundance of tool remains—thinning may have been produced by striking the hand axe near-perpendicularly with a soft hammer, possible with the invention of prepared platforms for tool making. The Boxgrove knappers also left behind large lithic flakes leftover from making hand axes, possibly with the intention of recycling them into other tools later. Late Acheulian sites elsewhere pre-prepared lithic core

In archaeology, a lithic core is a distinctive artifact that results from the practice of lithic reduction. In this sense, a core is the scarred nucleus resulting from the detachment of one or more flakes from a lump of source material or too ...

s ("Large Flake Blanks," LFB) in a variety of ways before shaping them into tools, making prepared platforms unnecessary. LFB Acheulian spreads out of Africa into West and South Asia before a million years ago and is present in Southern Europe after 600,000 years ago, but northern Europe (and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is ...

after 700,000 years ago) made use of soft hammers as they mainly made use of small, thick flint

Flint, occasionally flintstone, is a sedimentary cryptocrystalline form of the mineral quartz, categorized as the variety of chert that occurs in chalk or marly limestone. Flint was widely used historically to make stone tools and sta ...

nodules. The first prepared platforms in Africa come from the 450,000-year-old Fauresmith industry

In archaeology, Fauresmith industry is a stone tool industry that is transitional between the Acheulian and the Middle Stone Age. It is at the end of the Acheulian or beginning of the Middle Stone Age. It is named after the town of Fauresmith in S ...

, transitional between the Early Stone Age

The Lower Paleolithic (or Lower Palaeolithic) is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears in t ...

( Acheulian) and the Middle Stone Age.

With either method, knappers (tool makers) would have had to have produced some item indirectly related to creating the desired product (hierarchical organisation), which could represent a major cognitive development. Experiments with modern humans have shown that platform preparation cannot be learned through purely observational learning, unlike earlier techniques, and could be indicative of well developed teaching methods as well as self-regulated learning Self-regulated learning (SRL) is one of the domains of self-regulation, and is aligned most closely with educational aims. Broadly speaking, it refers to learning that is guided by '' metacognition'' (thinking about one's thinking), ''strategic act ...

. At Boxgrove, the knappers used not only stone but also bone and antler to make hammers, and the use of such a wide range of raw materials could speak to advanced planning capabilities as stoneworking requires a much different skillset to work and gather materials for than boneworking.

The Kapthurin Formation, Kenya, has yielded the oldest evidence of blade and bladelet technology, dating to 545 to 509 thousand years ago. This technology is rare even in the Middle Palaeolithic, and is typically associated with Upper Palaeolithic

The Upper Paleolithic (or Upper Palaeolithic) is the third and last subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. Very broadly, it dates to between 50,000 and 12,000 years ago (the beginning of the Holocene), according to some theories coin ...

modern humans. It is unclear if this is part of a long blade-making tradition, or if blade technology was lost and reinvented several times by multiple different human species.

Fire and construction

Despite apparent pushes into colder climates, evidence of fire is scarce in the archaeological record until 400 to 300 thousand years ago. Though it is possible fire remnants simply degraded, long and overall undisturbed occupation sequences such as at Arago or Gran Dolina conspicuously lack convincing evidence of fire usage. This pattern could possibly indicate the invention of ignition technology or improved fire maintenance techniques at this time, and that fire was not an integral part of people's lives before then in Europe. In Africa, on the other hand, humans may have been able to frequently scavenge fire as early as 1.6 million years ago from natural wildfires, which occur much more often on Africa, thus possibly (more or less) regularly using fire. The oldest established continuous fire site beyond Africa is the 780,000-year-old Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel. In Europe, evidence of constructed dwelling structures—classified as firm surface huts with solid foundations built in areas mostly sheltered from the weather—has been recorded since theCromerian Interglacial The Cromerian Stage or Cromerian Complex, also called the Cromerian (german: Cromerium), is a stage in the Pleistocene glacial history of north-western Europe, mostly occurring more than half a million years ago. It is named after the East Anglian ...

, the earliest example a 700,000-year-old stone foundation from Přezletice, Czech Republic. This dwelling probably featured a vaulted roof made of thick branches or thin poles, supported by a foundation of big rocks and earth. Other such dwellings have been postulated to have existed during or following the Holstein Interglacial (which began 424,000 years ago) in Bilzingsleben, Germany; Terra Amata, France; and Fermanville

Fermanville () is a commune in the Manche department in north-western France.

Located on the Channel coast between Cherbourg-en-Cotentin and Barfleur, Fermanville is divided into small hamlets on either side of the Cap lévi, the headland formi ...

and Saint-Germain-des-Vaux

Saint-Germain-des-Vaux () is a former commune in the Manche department in Normandy in north-western France. On 1 January 2017, it was merged into the new commune La Hague.Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

. These were probably occupied during the winter, and, averaging only in area, they were probably only used for sleeping in, while other activities (including firekeeping) seem to have been done outside. Less-permanent tent technology may have been present in Europe in the Lower Paleolithic.

Spears

The appearance of repeated fire usage—earliest in Europe from Beeches Pit, England, and Schöningen, Germany—roughly coincides with

The appearance of repeated fire usage—earliest in Europe from Beeches Pit, England, and Schöningen, Germany—roughly coincides with hafting

Hafting is a process by which an artifact, often bone, stone, or metal is attached to a ''haft'' (handle or strap). This makes the artifact more useful by allowing it to be shot (arrow), thrown by hand (spear), or used with more effective levera ...

technology (attaching stone points to spears) best exemplified by the Schöningen spears

The Schöningen spears are a set of ten wooden weapons from the Palaeolithic Age that were excavated between 1994 and 1999 from the 'Spear Horizon' in the open-cast lignite mine in Schöningen, Helmstedt district, Germany. They were found toget ...

. These nine wooden spears and spear fragments—in addition to a lance, and a double-pointed stick—date to 300,000 years ago and were preserved along a lakeside. The spears vary from in diameter, and may have been long, overall similar to present day competitive javelins. The spears were made of soft spruce wood, except for spear 4 which was (also soft) pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae. The World Flora Online created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden accepts ...

wood. This contrasts with the Clacton spearhead from Clacton-on-Sea

Clacton-on-Sea is a seaside town in the Tendring District in the county of Essex, England. It is located on the Tendring Peninsula and is the largest settlement in the Tendring District with a population of 56,874 (2016). The town is situated ...

, England, perhaps roughly 100,000 years older, which was made of hard yew wood. The Schöningen spears may have had a range of up to , though would have been more effective short range within about , making them effective distance weapons either against prey or predators. Besides these two localities, the only other site which provides solid evidence of European spear technology is the 120,000-year-old Lehringen site, Germany, where a yew spear was apparently lodged in an elephant. In Africa, 500,000-year-old points from Kathu Pan 1, South Africa, may have been hafted onto spears. Judging by indirect evidence, a horse scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

from the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove shows a puncture wound consistent with a spear wound. Evidence of hafting (in both Europe and Africa) becomes much more common after 300,000 years.

Language

The SH humans had a modern humanlike hyoid bone (which supports the tongue), andmiddle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles, which transfer the vibrations of the eardrum into waves in the ...

bones capable of finely distinguishing frequencies within the range of normal human speech. Judging by dental striations, they seem to have been predominantly right-handed, and handedness is related to the lateralisation of brain function, typically associated with language processing in modern humans. So, it is postulated that this population was speaking with some early form of language. Nonetheless, these traits do not absolutely prove the existence of language and humanlike speech, and its presence so early in time despite such anatomical arguments has been primarily opposed by cognitive scientist Philip Lieberman

Philip Lieberman (October 25, 1934 – July 12, 2022) was a cognitive scientist at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, United States. Originally trained in phonetics, he wrote a dissertation on intonation. His career focused on topic ...

.

See also

*Altamura Man

The Altamura Man is a fossil of the genus ''Homo'' discovered in 1993 in a karst sinkhole in the Lamalunga Cave near the city of Altamura, Italy.

Remarkably well preserved but covered in a thick layer of calcite taking the shape of cave popcor ...

* Ceprano Man

* Dmanisi hominins

* Early European modern humans

Early European modern humans (EEMH), or Cro-Magnons, were the first early modern humans (''Homo sapiens'') to settle in Europe, migrating from Western Asia, continuously occupying the continent possibly from as early as 56,800 years ago. They ...

* ''Homo rhodesiensis

''Homo rhodesiensis'' is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1 (the "Kabwe skull" or "Broken Hill skull", also "Rhodesian Man"), a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from a cave at Broken Hill, or Kabwe, No ...

''

* ''Homo antecessor

''Homo antecessor'' (Latin "pioneer man") is an extinct species of archaic human recorded in the Spanish Sierra de Atapuerca, a productive archaeological site, from 1.2 to 0.8 million years ago during the Early Pleistocene. Populations of this ...

''

* Swanscombe Heritage Park

Swanscombe Skull Site or Swanscombe Heritage Park is a geological Site of Special Scientific Interest in Swanscombe in north-west Kent, England. It contains two Geological Conservation Review sites and a National Nature Reserve. The park lies ...

* Tautavel Man