homeostatic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

The plasma ionized calcium (Ca2+) concentration is very tightly controlled by a pair of homeostatic mechanisms. The sensor for the first one is situated in the parathyroid glands, where the chief cells sense the Ca2+ level by means of specialized calcium receptors in their membranes. The sensors for the second are the parafollicular cells in the

The plasma ionized calcium (Ca2+) concentration is very tightly controlled by a pair of homeostatic mechanisms. The sensor for the first one is situated in the parathyroid glands, where the chief cells sense the Ca2+ level by means of specialized calcium receptors in their membranes. The sensors for the second are the parafollicular cells in the

The plasma pH can be altered by respiratory changes in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide; or altered by metabolic changes in the

The plasma pH can be altered by respiratory changes in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide; or altered by metabolic changes in the

Homeostasis

* Walter Bradford Cannon

(1932) {{Authority control Physiology Biology terminology Cybernetics *

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life and living organisms. It is a broad natural science that encompasses a wide range of fields and unifying principles that explain the structure, function, growth, History of life, origin, evolution, and ...

, homeostasis (British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

also homoeostasis; ) is the state of steady internal physical and chemical

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combin ...

conditions maintained by living systems

Living systems are life forms (or, more colloquially known as living things) treated as a system. They are said to be open self-organizing and said to interact with their environment. These systems are maintained by flows of information, energy an ...

. This is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and includes many variables, such as body temperature

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

and fluid balance

Fluid balance is an aspect of the homeostasis of organisms in which the amount of water in the organism needs to be controlled, via osmoregulation and behavior, such that the concentrations of electrolytes (salts in solution) in the various body ...

, being kept within certain pre-set limits (homeostatic range). Other variables include the pH of extracellular fluid

In cell biology, extracellular fluid (ECF) denotes all body fluid outside the cells of any multicellular organism. Total body water in healthy adults is about 50–60% (range 45 to 75%) of total body weight; women and the obese typically ha ...

, the concentrations of sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

, potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

, and calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s, as well as the blood sugar level

The blood sugar level, blood sugar concentration, blood glucose level, or glycemia is the measure of glucose concentrated in the blood. The body tightly regulates blood glucose levels as a part of metabolic homeostasis.

For a 70 kg (1 ...

, and these need to be regulated despite changes in the environment, diet, or level of activity. Each of these variables is controlled by one or more regulators or homeostatic mechanisms, which together maintain life.

Homeostasis is brought about by a natural resistance to change when already in optimal conditions, and equilibrium is maintained by many regulatory mechanisms; it is thought to be the central motivation for all organic action. All homeostatic control mechanisms have at least three interdependent components for the variable being regulated: a receptor, a control center, and an effector. The receptor is the sensing component that monitors and responds to changes in the environment, either external or internal. Receptors include thermoreceptor

A thermoreceptor is a non-specialised sense Cutaneous receptor, receptor, or more accurately the receptive portion of a sensory neuron, that codes absolute and relative changes in temperature, primarily within the innocuous range. In the mammalian ...

s and mechanoreceptor

A mechanoreceptor, also called mechanoceptor, is a sensory receptor that responds to mechanical pressure or distortion. Mechanoreceptors are located on sensory neurons that convert mechanical pressure into action potential, electrical signals tha ...

s. Control centers include the respiratory center

The respiratory center is located in the medulla oblongata and pons, in the brainstem. The respiratory center is made up of three major respiratory groups of neurons, two in the medulla and one in the pons. In the medulla they are the dorsal ...

and the renin-angiotensin system. An effector is the target acted on, to bring about the change back to the normal state. At the cellular level, effectors include nuclear receptor

In the field of molecular biology, nuclear receptors are a class of proteins responsible for sensing steroids, thyroid hormones, vitamins, and certain other molecules. These intracellular receptors work with other proteins to regulate the ex ...

s that bring about changes in gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

through up-regulation or down-regulation and act in negative feedback

Negative feedback (or balancing feedback) occurs when some function (Mathematics), function of the output of a system, process, or mechanism is feedback, fed back in a manner that tends to reduce the fluctuations in the output, whether caused ...

mechanisms. An example of this is in the control of bile acid

Bile acids are steroid acids found predominantly in the bile of mammals and other vertebrates. Diverse bile acids are synthesized in the liver in peroxisomes. Bile acids are conjugated with taurine or glycine residues to give anions called bile ...

s in the liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

.

Some centers, such as the renin–angiotensin system

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS), or renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS), is a hormone system that regulates blood pressure, fluid, and electrolyte balance, and systemic vascular resistance.

When renal blood flow is reduced, ...

, control more than one variable. When the receptor senses a stimulus, it reacts by sending action potentials to a control center. The control center sets the maintenance range—the acceptable upper and lower limits—for the particular variable, such as temperature. The control center responds to the signal by determining an appropriate response and sending signals to an effector, which can be one or more muscles, an organ, or a gland

A gland is a Cell (biology), cell or an Organ (biology), organ in an animal's body that produces and secretes different substances that the organism needs, either into the bloodstream or into a body cavity or outer surface. A gland may also funct ...

. When the signal is received and acted on, negative feedback is provided to the receptor that stops the need for further signaling.

The cannabinoid receptor type 1

Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), is a G protein-coupled cannabinoid receptor that in humans is encoded by the ''CNR1'' gene. And discovered, by determination and characterization in 1988, and cloned in 1990 for the first time. The human CB1 rece ...

, located at the presynaptic

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

, is a receptor

Receptor may refer to:

* Sensory receptor, in physiology, any neurite structure that, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and respond ...

that can stop stressful neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

release to the postsynaptic neuron; it is activated by endocannabinoids

Cannabinoids () are several structural classes of compounds found primarily in the ''Cannabis'' plant or as synthetic compounds. The most notable cannabinoid is the phytocannabinoid tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (delta-9-THC), the primary psychoact ...

such as anandamide

Anandamide (ANA), also referred to as ''N''-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA) is a fatty acid neurotransmitter belonging to the fatty acid derivative group known as N-acylethanolamine (NAE). Anandamide takes its name from the Sanskrit word ''ananda ...

(''N''-arachidonoylethanolamide) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol via a retrograde signaling process in which these compounds are synthesized by and released from postsynaptic neurons, and travel back to the presynaptic terminal to bind to the CB1 receptor for modulation of neurotransmitter release to obtain homeostasis.

The polyunsaturated fatty acid

In biochemistry and nutrition, a polyunsaturated fat is a fat that contains a polyunsaturated fatty acid (abbreviated PUFA), which is a subclass of fatty acid characterized by a backbone with two or more carbon–carbon double bonds.

Some polyunsa ...

s are lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

derivatives of omega-3 (docosahexaenoic acid

Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is an omega−3 fatty acid that is an important component of the human brain, cerebral cortex, skin, and retina. It is given the fatty acid notation 22:6(''n''−3). It can be synthesized from alpha-linolenic acid or ...

, and eicosapentaenoic acid) or of omega-6

Omega−6 fatty acids (also referred to as ω−6 fatty acids or ''n''−6 fatty acids) are a family of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) that share a final carbon-carbon double bond in the ''n''−6 position, that is, the sixth bond, count ...

(arachidonic acid

Arachidonic acid (AA, sometimes ARA) is a polyunsaturated omega−6 fatty acid 20:4(ω−6), or 20:4(5,8,11,14). It is a precursor in the formation of leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and thromboxanes.

Together with omega−3 fatty acids an ...

). They are synthesized from membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s and used as precursors for endocannabinoids to mediate significant effects in the fine-tuning adjustment of body homeostasis.

Etymology

The word ''homeostasis'' ( ) uses combining forms of ''homeo-'' and ''-stasis'',Neo-Latin

Neo-LatinSidwell, Keith ''Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin'' in ; others, throughout. (also known as New Latin and Modern Latin) is the style of written Latin used in original literary, scholarly, and scientific works, first in Italy d ...

from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: ὅμοιος ''homoios'', "similar" and στάσις ''stasis'', "standing still", yielding the idea of "staying the same".

History

The concept of the regulation of the internal environment was described by French physiologistClaude Bernard

Claude Bernard (; 12 July 1813 – 10 February 1878) was a French physiologist. I. Bernard Cohen of Harvard University called Bernard "one of the greatest of all men of science". He originated the term ''milieu intérieur'' and the associated c ...

in 1849, and the word ''homeostasis'' was coined by Walter Bradford Cannon

Walter Bradford Cannon (October 19, 1871 – October 1, 1945) was an American physiologist, professor and chairman of the Department of Physiology at Harvard Medical School. He coined the term " fight or flight response", and developed the theory ...

in 1926. In 1932, Joseph Barcroft

Sir Joseph Barcroft (26 July 1872 – 21 March 1947) was a British physiologist best known for his studies of the oxygenation of blood.

Life

Born in Newry, County Down into a Quaker family, he was the son of Henry Barcroft DL and Anna Ric ...

, a British physiologist, was the first to say that higher brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

function required the most stable internal environment. Thus, to Barcroft homeostasis was not only organized by the brain—homeostasis served the brain. Homeostasis is an almost exclusively biological term, referring to the concepts described by Bernard and Cannon, concerning the constancy of the internal environment in which the cells of the body live and survive. The term cybernetics

Cybernetics is the transdisciplinary study of circular causal processes such as feedback and recursion, where the effects of a system's actions (its outputs) return as inputs to that system, influencing subsequent action. It is concerned with ...

is applied to technological control system

A control system manages, commands, directs, or regulates the behavior of other devices or systems using control loops. It can range from a single home heating controller using a thermostat controlling a domestic boiler to large industrial ...

s such as thermostat

A thermostat is a regulating device component which senses the temperature of a physical system and performs actions so that the system's temperature is maintained near a desired setpoint.

Thermostats are used in any device or system tha ...

s, which function as homeostatic mechanisms but are often defined much more broadly than the biological term of homeostasis.

Overview

The metabolic processes of all organisms can only take place in very specific physical and chemical environments. The conditions vary with each organism, and also with whether the chemical processes take place inside the cell or in theinterstitial fluid

In cell biology, extracellular fluid (ECF) denotes all body fluid outside the Cell (biology), cells of any multicellular organism. Body water, Total body water in healthy adults is about 50–60% (range 45 to 75%) of total body weight; women ...

bathing the cells. The best-known homeostatic mechanisms in humans and other mammals are regulators that keep the composition of the extracellular fluid

In cell biology, extracellular fluid (ECF) denotes all body fluid outside the cells of any multicellular organism. Total body water in healthy adults is about 50–60% (range 45 to 75%) of total body weight; women and the obese typically ha ...

(or the "internal environment") constant, especially with regard to the temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measurement, measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making ...

, pH, osmolality, and the concentrations of sodium

Sodium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Na (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal. Sodium is an alkali metal, being in group 1 element, group 1 of the peri ...

, potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

, glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

, carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

, and oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

. However, a great many other homeostatic mechanisms, encompassing many aspects of human physiology

The human body is the entire structure of a human being. It is composed of many different types of cells that together create tissues and subsequently organs and then organ systems.

The external human body consists of a head, hair, neck, ...

, control other entities in the body. Where the levels of variables are higher or lower than those needed, they are often prefixed with ''hyper-'' and ''hypo-'', respectively such as hyperthermia

Hyperthermia, also known as overheating, is a condition in which an individual's body temperature is elevated beyond normal due to failed thermoregulation. The person's body produces or absorbs more heat than it dissipates. When extreme te ...

and hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

or hypertension

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a Chronic condition, long-term Disease, medical condition in which the blood pressure in the artery, arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms i ...

and hypotension

Hypotension, also known as low blood pressure, is a cardiovascular condition characterized by abnormally reduced blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood and is ...

.

If an entity is homeostatically controlled it does not imply that its value is necessarily absolutely steady in health. Core body temperature

Normal human body temperature (normothermia, euthermia) is the typical temperature range found in humans. The normal human body temperature range is typically stated as .

Human body temperature varies. It depends on sex, age, time of day, exert ...

is, for instance, regulated by a homeostatic mechanism with temperature sensors in, amongst others, the hypothalamus

The hypothalamus (: hypothalami; ) is a small part of the vertebrate brain that contains a number of nucleus (neuroanatomy), nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrin ...

of the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

. However, the set point of the regulator is regularly reset. For instance, core body temperature in humans varies during the course of the day (i.e. has a circadian rhythm

A circadian rhythm (), or circadian cycle, is a natural oscillation that repeats roughly every 24 hours. Circadian rhythms can refer to any process that originates within an organism (i.e., Endogeny (biology), endogenous) and responds to the env ...

), with the lowest temperatures occurring at night, and the highest in the afternoons. Other normal temperature variations include those related to the menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle is a series of natural changes in hormone production and the structures of the uterus and ovaries of the female reproductive system that makes pregnancy possible. The ovarian cycle controls the production and release of eg ...

. The temperature regulator's set point is reset during infections to produce a fever. Organisms are capable of adjusting somewhat to varied conditions such as temperature changes or oxygen levels at altitude, by a process of acclimatisation

Acclimatization or acclimatisation ( also called acclimation or acclimatation) is the process in which an individual organism adjusts to a change in its environment (such as a change in altitude, temperature, humidity, photoperiod, or pH), ...

.

Homeostasis does not govern every activity in the body. For instance, the signal (be it via neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s or hormone

A hormone (from the Ancient Greek, Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of cell signaling, signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs or tissues by complex biological processes to regulate physio ...

s) from the sensor to the effector is, of necessity, highly variable in order to convey information

Information is an Abstraction, abstract concept that refers to something which has the power Communication, to inform. At the most fundamental level, it pertains to the Interpretation (philosophy), interpretation (perhaps Interpretation (log ...

about the direction and magnitude of the error detected by the sensor. Similarly, the effector's response needs to be highly adjustable to reverse the error – in fact it should be very nearly in proportion (but in the opposite direction) to the error that is threatening the internal environment. For instance, arterial blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressure" r ...

in mammals is homeostatically controlled and measured by stretch receptor

Stretch receptors are mechanoreceptors responsive to distention of various organs and muscles, and are neurologically linked to the Medulla oblongata, medulla in the brain stem via Afferent nerve fiber, afferent nerve fibers. Examples include stre ...

s in the walls of the aortic arch

The aortic arch, arch of the aorta, or transverse aortic arch () is the part of the aorta between the ascending and descending aorta. The arch travels backward, so that it ultimately runs to the left of the trachea.

Structure

The aorta begins ...

and carotid sinus

In human anatomy, the carotid sinus is a dilated area at the base of the internal carotid artery just superior to the bifurcation of the internal carotid and external carotid at the level of the superior border of thyroid cartilage. The carot ...

es at the beginnings of the internal carotid arteries. The sensors send messages via sensory nerve

A sensory nerve, or afferent nerve, is a nerve that contains exclusively afferent nerve fibers. Nerves containing also motor fibers are called mixed nerve, mixed. Afferent nerve fibers in a sensory nerve carry sensory system, sensory information ...

s to the medulla oblongata

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

of the brain indicating whether the blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of Circulatory system, circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term ...

has fallen or risen, and by how much. The medulla oblongata then distributes messages along motor or efferent nerves belonging to the autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), sometimes called the visceral nervous system and formerly the vegetative nervous system, is a division of the nervous system that operates viscera, internal organs, smooth muscle and glands. The autonomic nervo ...

to a wide variety of effector organs, whose activity is consequently changed to reverse the error in the blood pressure. One of the effector organs is the heart whose rate is stimulated to rise (tachycardia

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate. In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults. Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal ...

) when the arterial blood pressure falls, or to slow down (bradycardia

Bradycardia, also called bradyarrhythmia, is a resting heart rate under 60 beats per minute (BPM). While bradycardia can result from various pathological processes, it is commonly a physiological response to cardiovascular conditioning or due ...

) when the pressure rises above the set point. Thus the heart rate (for which there is no sensor in the body) is not homeostatically controlled but is one of the effector responses to errors in arterial blood pressure. Another example is the rate of sweating

Perspiration, also known as sweat, is the fluid secreted by sweat glands in the skin of mammals.

Two types of sweat glands can be found in humans: eccrine glands and apocrine glands. The eccrine sweat glands are distributed over much of the ...

. This is one of the effectors in the homeostatic control of body temperature, and therefore highly variable in rough proportion to the heat load that threatens to destabilize the body's core temperature, for which there is a sensor in the hypothalamus

The hypothalamus (: hypothalami; ) is a small part of the vertebrate brain that contains a number of nucleus (neuroanatomy), nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrin ...

of the brain.

Controls of variables

Core temperature

Mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s regulate their core temperature

Normal human body temperature (normothermia, euthermia) is the typical temperature range found in humans. The normal human body temperature range is typically stated as .

Human body temperature varies. It depends on sex, age, time of day, exert ...

using input from thermoreceptor

A thermoreceptor is a non-specialised sense Cutaneous receptor, receptor, or more accurately the receptive portion of a sensory neuron, that codes absolute and relative changes in temperature, primarily within the innocuous range. In the mammalian ...

s in the hypothalamus

The hypothalamus (: hypothalami; ) is a small part of the vertebrate brain that contains a number of nucleus (neuroanatomy), nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrin ...

, brain, spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

, internal organs

In a multicellular organism, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to a ...

, and great veins. Apart from the internal regulation of temperature, a process called allostasis can come into play that adjusts behaviour to adapt to the challenge of very hot or cold extremes (and to other challenges). These adjustments may include seeking shade and reducing activity, seeking warmer conditions and increasing activity, or huddling.

Behavioral thermoregulation takes precedence over physiological thermoregulation since necessary changes can be affected more quickly and physiological thermoregulation is limited in its capacity to respond to extreme temperatures.

When the core temperature falls, the blood supply to the skin is reduced by intense vasoconstriction

Vasoconstriction is the narrowing of the blood vessels resulting from contraction of the muscular wall of the vessels, in particular the large arteries and small arterioles. The process is the opposite of vasodilation, the widening of blood vesse ...

. The blood flow to the limbs (which have a large surface area) is similarly reduced and returned to the trunk via the deep veins which lie alongside the arteries (forming venae comitantes). This acts as a counter-current exchange system that short-circuits the warmth from the arterial blood directly into the venous blood returning into the trunk, causing minimal heat loss from the extremities in cold weather. The subcutaneous limb veins are tightly constricted, not only reducing heat loss from this source but also forcing the venous blood into the counter-current system in the depths of the limbs.

The metabolic rate is increased, initially by non-shivering thermogenesis

Thermogenesis is the process of heat production in organisms. It occurs in all warm-blooded animals, and also in a few species of thermogenic plants such as the Eastern skunk cabbage, the Voodoo lily ('' Sauromatum venosum''), and the giant w ...

, followed by shivering thermogenesis if the earlier reactions are insufficient to correct the hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

.

When core temperature rises are detected by thermoreceptor

A thermoreceptor is a non-specialised sense Cutaneous receptor, receptor, or more accurately the receptive portion of a sensory neuron, that codes absolute and relative changes in temperature, primarily within the innocuous range. In the mammalian ...

s, the sweat gland

Sweat glands, also known as sudoriferous or sudoriparous glands, , are small tubular structures of the skin that produce sweat. Sweat glands are a type of exocrine gland, which are glands that produce and secrete substances onto an epithelial s ...

s in the skin are stimulated via cholinergic

Cholinergic agents are compounds which mimic the action of acetylcholine and/or butyrylcholine. In general, the word " choline" describes the various quaternary ammonium salts containing the ''N'',''N'',''N''-trimethylethanolammonium cation ...

sympathetic nerves to secrete sweat

Perspiration, also known as sweat, is the fluid secreted by sweat glands in the skin of mammals.

Two types of sweat glands can be found in humans: eccrine glands and Apocrine sweat gland, apocrine glands. The eccrine sweat glands are distribu ...

onto the skin, which, when it evaporates, cools the skin and the blood flowing through it. Panting is an alternative effector in many vertebrates, which cools the body also by the evaporation of water, but this time from the mucous membranes

A mucous membrane or mucosa is a membrane that lines various cavities in the body of an organism and covers the surface of internal organs. It consists of one or more layers of epithelial cells overlying a layer of loose connective tissue. It is ...

of the throat and mouth.

Blood glucose

Blood sugar

The blood sugar level, blood sugar concentration, blood glucose level, or glycemia is the measure of glucose concentrated in the blood. The body tightly regulates blood glucose levels as a part of metabolic homeostasis.

For a 70 kg (1 ...

levels are regulated within fairly narrow limits. In mammals, the primary sensors for this are the beta cells of the pancreatic islets

The pancreatic islets or islets of Langerhans are the regions of the pancreas that contain its endocrine (hormone-producing) cells, discovered in 1869 by German pathological anatomist Paul Langerhans. The pancreatic islets constitute 1–2% o ...

. The beta cells respond to a rise in the blood sugar level by secreting insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

into the blood and simultaneously inhibiting their neighboring alpha cells

Alpha cells (α-cells) are endocrine cells that are found in the Islets of Langerhans in the pancreas. Alpha cells secrete the peptide hormone glucagon in order to increase glucose levels in the blood stream.

Discovery

Islets of Langerhans we ...

from secreting glucagon

Glucagon is a peptide hormone, produced by alpha cells of the pancreas. It raises the concentration of glucose and fatty acids in the bloodstream and is considered to be the main catabolic hormone of the body. It is also used as a Glucagon (medic ...

into the blood. This combination (high blood insulin levels and low glucagon levels) act on effector tissues, the chief of which is the liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

, fat cells

Adipocytes, also known as lipocytes and fat cells, are the cell (biology), cells that primarily compose adipose tissue, specialized in storing energy as fat. Adipocytes are derived from mesenchymal stem cells which give rise to adipocytes through ...

, and muscle cells

A muscle cell, also known as a myocyte, is a mature contractile cell in the muscle of an animal. In humans and other vertebrates there are three types: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac (cardiomyocytes). A skeletal muscle cell is long and threadli ...

. The liver is inhibited from producing glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

, taking it up instead, and converting it to glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

and triglycerides

A triglyceride (from ''wikt:tri-#Prefix, tri-'' and ''glyceride''; also TG, triacylglycerol, TAG, or triacylglyceride) is an ester derived from glycerol and three fatty acids.

Triglycerides are the main constituents of body fat in humans and oth ...

. The glycogen is stored in the liver, but the triglycerides are secreted into the blood as very low-density lipoprotein

Very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), density relative to extracellular water, is a type of lipoprotein made by the liver. VLDL is one of the five major groups of lipoproteins (chylomicrons, VLDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein, LDL, low-density ...

(VLDL) particles which are taken up by adipose tissue

Adipose tissue (also known as body fat or simply fat) is a loose connective tissue composed mostly of adipocytes. It also contains the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of cells including preadipocytes, fibroblasts, Blood vessel, vascular endothel ...

, there to be stored as fats. The fat cells take up glucose through special glucose transporters ( GLUT4), whose numbers in the cell wall are increased as a direct effect of insulin acting on these cells. The glucose that enters the fat cells in this manner is converted into triglycerides (via the same metabolic pathways as are used by the liver) and then stored in those fat cells together with the VLDL-derived triglycerides that were made in the liver. Muscle cells also take glucose up through insulin-sensitive GLUT4 glucose channels, and convert it into muscle glycogen.

A fall in blood glucose, causes insulin secretion to be stopped, and glucagon

Glucagon is a peptide hormone, produced by alpha cells of the pancreas. It raises the concentration of glucose and fatty acids in the bloodstream and is considered to be the main catabolic hormone of the body. It is also used as a Glucagon (medic ...

to be secreted from the alpha cells into the blood. This inhibits the uptake of glucose from the blood by the liver, fats cells, and muscle. Instead the liver is strongly stimulated to manufacture glucose from glycogen (through glycogenolysis

Glycogenolysis is the breakdown of glycogen (n) to glucose-1-phosphate and glycogen (n-1). Glycogen branches are catabolized by the sequential removal of glucose monomers via phosphorolysis, by the enzyme glycogen phosphorylase.

Mechanis ...

) and from non-carbohydrate sources (such as lactate and de-aminated amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the Proteinogenic amino acid, 22 α-amino acids incorporated into p ...

) using a process known as gluconeogenesis

Gluconeogenesis (GNG) is a metabolic pathway that results in the biosynthesis of glucose from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates. It is a ubiquitous process, present in plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. In verte ...

. The glucose thus produced is discharged into the blood correcting the detected error (hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia (American English), also spelled hypoglycaemia or hypoglycæmia (British English), sometimes called low blood sugar, is a fall in blood sugar to levels below normal, typically below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L). Whipple's tria ...

). The glycogen stored in muscles remains in the muscles, and is only broken down, during exercise, to glucose-6-phosphate

Glucose 6-phosphate (G6P, sometimes called the Robison ester) is a glucose sugar phosphorylated at the hydroxy group on carbon 6. This dianion is very common in cells as the majority of glucose entering a cell will become phosphorylated in this wa ...

and thence to pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic ...

to be fed into the citric acid cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of chemical reaction, biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-Co ...

or turned into lactate. It is only the lactate and the waste products of the citric acid cycle that are returned to the blood. The liver can take up only the lactate, and, by the process of energy-consuming gluconeogenesis

Gluconeogenesis (GNG) is a metabolic pathway that results in the biosynthesis of glucose from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates. It is a ubiquitous process, present in plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. In verte ...

, convert it back to glucose.

Iron levels

Iron homeostasis is a crucial physiological process that regulates iron levels in the body, ensuring that this essential nutrient is available for vital functions while preventing potential toxicity from excess iron. The primary site for iron absorption is theduodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In mammals, it may be the principal site for iron absorption.

The duodenum precedes the jejunum and ileum and is the shortest p ...

, where dietary iron exists in two forms: heme iron, sourced from animal products, and non-heme iron, found in plant foods. Heme iron is more efficiently absorbed than non-heme iron, which requires factors like vitamin C

Vitamin C (also known as ascorbic acid and ascorbate) is a water-soluble vitamin found in citrus and other fruits, berries and vegetables. It is also a generic prescription medication and in some countries is sold as a non-prescription di ...

for optimal uptake. Once absorbed, iron enters the bloodstream bound to transferrin

Transferrins are glycoproteins found in vertebrates which bind and consequently mediate the transport of iron (Fe) through blood plasma. They are produced in the liver and contain binding sites for two Iron(III), Fe3+ ions. Human transferrin is ...

, a transport protein that delivers it to various tissues and organs. Cells uptake iron through transferrin receptors, making it available for critical processes such as oxygen transport and DNA synthesis. Excess iron is stored in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow as ferritin

Ferritin is a universal intracellular and extracellular protein that stores iron and releases it in a controlled fashion. The protein is produced by almost all living organisms, including archaea, bacteria, algae, higher plants, and animals. ...

and hemosiderin. The regulation of iron levels is primarily controlled by the hormone hepcidin

Hepcidin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''HAMP'' gene. Hepcidin is a key regulator of the entry of iron into the circulation in mammals.

During conditions in which the hepcidin level is abnormally high, such as inflammation, se ...

, produced by the liver, which adjusts intestinal absorption and the release of stored iron based on the body’s needs. Disruptions in iron homeostasis can lead to conditions such as iron deficiency anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

or iron overload disorders like hemochromatosis

Iron overload is the abnormal and increased accumulation of total iron in the body, leading to organ damage. The primary mechanism of organ damage is oxidative stress, as elevated intracellular iron levels increase free radical formation via the ...

, highlighting the importance of maintaining the delicate balance of this vital nutrient for overall health.

Copper regulation

Copper is absorbed, transported, distributed, stored, and excreted in the body according to complex homeostatic processes which ensure a constant and sufficient supply of the micronutrient while simultaneously avoiding excess levels. If an insufficient amount of copper is ingested for a short period of time, copper stores in the liver will be depleted. Should this depletion continue, a copper health deficiency condition may develop. If too much copper is ingested, an excess condition can result. Both of these conditions, deficiency and excess, can lead to tissue injury and disease. However, due to homeostatic regulation, the human body is capable of balancing a wide range of copper intakes for the needs of healthy individuals. Many aspects of copper homeostasis are known at the molecular level. Copper's essentiality is due to its ability to act as an electron donor or acceptor as its oxidation state fluxes between Cu1+ (cuprous

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orange ...

) and Cu2+ ( cupric). As a component of about a dozen cuproenzymes, copper is involved in key redox

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is t ...

(i.e., oxidation-reduction) reactions in essential metabolic processes such as mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

l respiration, synthesis of melanin

Melanin (; ) is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are ...

, and cross-linking of collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

. Copper is an integral part of the antioxidant enzyme copper-zinc superoxide dismutase, and has a role in iron homeostasis as a cofactor in ceruloplasmin.

Levels of blood gases

Changes in the levels of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and plasma pH are sent to therespiratory center

The respiratory center is located in the medulla oblongata and pons, in the brainstem. The respiratory center is made up of three major respiratory groups of neurons, two in the medulla and one in the pons. In the medulla they are the dorsal ...

, in the brainstem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is conti ...

where they are regulated.

The partial pressure

In a mixture of gases, each constituent gas has a partial pressure which is the notional pressure of that constituent gas as if it alone occupied the entire volume of the original mixture at the same temperature. The total pressure of an ideal g ...

of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

in the arterial blood

Arterial blood is the oxygenated blood in the circulatory system found in the pulmonary vein, the left chambers of the heart, and in the artery, arteries. It is bright red in color, while venous blood is dark red in color (but looks purple through ...

is monitored by the peripheral chemoreceptors ( PNS) in the carotid artery Carotid artery may refer to:

* Common carotid artery, often "carotids" or "carotid", an artery on each side of the neck which divides into the external carotid artery and internal carotid artery

* External carotid artery, an artery on each side of ...

and aortic arch

The aortic arch, arch of the aorta, or transverse aortic arch () is the part of the aorta between the ascending and descending aorta. The arch travels backward, so that it ultimately runs to the left of the trachea.

Structure

The aorta begins ...

. A change in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide is detected as altered pH in the cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless Extracellular fluid#Transcellular fluid, transcellular body fluid found within the meninges, meningeal tissue that surrounds the vertebrate brain and spinal cord, and in the ventricular system, ven ...

by central chemoreceptors

A central chemoreceptor is a chemoreceptor sensitive to the pH of its environment. Central chemoreceptors are located on the ventrolateral medulla oblongata, medullary surface in vicinity of the exit of CN IX and CN X in the central nervous syste ...

( CNS) in the medulla oblongata

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

of the brainstem

The brainstem (or brain stem) is the posterior stalk-like part of the brain that connects the cerebrum with the spinal cord. In the human brain the brainstem is composed of the midbrain, the pons, and the medulla oblongata. The midbrain is conti ...

. Information from these sets of sensors is sent to the respiratory center which activates the effector organs – the diaphragm and other muscles of respiration

The muscles of respiration are the muscles that contribute to inhalation and exhalation, by aiding in the expansion and contraction of the thoracic cavity. The diaphragm and, to a lesser extent, the intercostal muscles drive respiration during ...

. An increased level of carbon dioxide in the blood, or a decreased level of oxygen, will result in a deeper breathing pattern and increased respiratory rate

The respiratory rate is the rate at which breathing occurs; it is set and controlled by the respiratory center of the brain. A person's respiratory rate is usually measured in breaths per minute.

Measurement

The respiratory rate in humans is mea ...

to bring the blood gases back to equilibrium.

Too little carbon dioxide, and, to a lesser extent, too much oxygen in the blood can temporarily halt breathing, a condition known as apnea

Apnea (also spelled apnoea in British English) is the temporary cessation of breathing. During apnea, there is no movement of the muscles of inhalation, and the volume of the lungs initially remains unchanged. Depending on how blocked the ...

, which freedivers use to prolong the time they can stay underwater.

The partial pressure of carbon dioxide is more of a deciding factor in the monitoring of pH. However, at high altitude (above 2500 m) the monitoring of the partial pressure of oxygen takes priority, and hyperventilation

Hyperventilation is irregular breathing that occurs when the rate or tidal volume of breathing eliminates more carbon dioxide than the body can produce. This leads to hypocapnia, a reduced concentration of carbon dioxide dissolved in the blo ...

keeps the oxygen level constant. With the lower level of carbon dioxide, to keep the pH at 7.4 the kidneys secrete hydrogen ions into the blood and excrete bicarbonate into the urine. This is important in acclimatization to high altitude.

Blood oxygen content

Thekidneys

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and right in the retro ...

measure the oxygen content rather than the partial pressure of oxygen in the arterial blood. When the oxygen content of the blood is chronically low, oxygen-sensitive cells secrete erythropoietin

Erythropoietin (; EPO), also known as erythropoetin, haematopoietin, or haemopoietin, is a glycoprotein cytokine secreted mainly by the kidneys in response to cellular hypoxia; it stimulates red blood cell production ( erythropoiesis) in th ...

(EPO) into the blood. The effector tissue is the red bone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid tissue found within the spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It is composed of hematopoietic c ...

which produces red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s (RBCs, also called ). The increase in RBCs leads to an increased hematocrit

The hematocrit () (Ht or HCT), also known by several other names, is the volume percentage (vol%) of red blood cells (RBCs) in blood, measured as part of a blood test. The measurement depends on the number and size of red blood cells. It is nor ...

in the blood, and a subsequent increase in hemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobin ...

that increases the oxygen carrying capacity. This is the mechanism whereby high altitude dwellers have higher hematocrits than sea-level residents, and also why persons with pulmonary insufficiency or right-to-left shunt

A right-to-left shunt is a cardiac shunt which allows blood to flow from the right heart to the left heart. This terminology is used both for the abnormal state in humans and for normal physiological shunts in reptiles.

Clinical Significance

...

s in the heart (through which venous blood by-passes the lungs and goes directly into the systemic circulation) have similarly high hematocrits.

Regardless of the partial pressure of oxygen in the blood, the amount of oxygen that can be carried, depends on the hemoglobin content. The partial pressure of oxygen may be sufficient for example in anemia

Anemia (also spelt anaemia in British English) is a blood disorder in which the blood has a reduced ability to carry oxygen. This can be due to a lower than normal number of red blood cells, a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin availabl ...

, but the hemoglobin content will be insufficient and subsequently as will be the oxygen content. Given enough supply of iron, vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin involved in metabolism. One of eight B vitamins, it serves as a vital cofactor (biochemistry), cofactor in DNA synthesis and both fatty acid metabolism, fatty acid and amino a ...

and folic acid

Folate, also known as vitamin B9 and folacin, is one of the B vitamins. Manufactured folic acid, which is converted into folate by the body, is used as a dietary supplement and in food fortification as it is more stable during processing and ...

, EPO can stimulate RBC production, and hemoglobin and oxygen content restored to normal.

Arterial blood pressure

The brain can regulate blood flow over a range of blood pressure values byvasoconstriction

Vasoconstriction is the narrowing of the blood vessels resulting from contraction of the muscular wall of the vessels, in particular the large arteries and small arterioles. The process is the opposite of vasodilation, the widening of blood vesse ...

and vasodilation

Vasodilation, also known as vasorelaxation, is the widening of blood vessels. It results from relaxation of smooth muscle cells within the vessel walls, in particular in the large veins, large arteries, and smaller arterioles. Blood vessel wa ...

of the arteries.

High pressure receptors called baroreceptor

Baroreceptors (or archaically, pressoreceptors) are stretch receptors that sense blood pressure. Thus, increases in the pressure of blood vessel triggers increased action potential generation rates and provides information to the central nervous s ...

s in the walls of the aortic arch

The aortic arch, arch of the aorta, or transverse aortic arch () is the part of the aorta between the ascending and descending aorta. The arch travels backward, so that it ultimately runs to the left of the trachea.

Structure

The aorta begins ...

and carotid sinus

In human anatomy, the carotid sinus is a dilated area at the base of the internal carotid artery just superior to the bifurcation of the internal carotid and external carotid at the level of the superior border of thyroid cartilage. The carot ...

(at the beginning of the internal carotid artery

The internal carotid artery is an artery in the neck which supplies the anterior cerebral artery, anterior and middle cerebral artery, middle cerebral circulation.

In human anatomy, the internal and external carotid artery, external carotid ari ...

) monitor the arterial blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of Circulatory system, circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term ...

. Rising pressure is detected when the walls of the arteries stretch due to an increase in blood volume

Blood volume (volemia) is the volume of blood ( blood cells and plasma) in the circulatory system of any individual.

Humans

A typical adult has a blood volume of approximately 5 liters, with females and males having approximately the same blood p ...

. This causes heart muscle cells to secrete the hormone atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) into the blood. This acts on the kidneys to inhibit the secretion of renin and aldosterone causing the release of sodium, and accompanying water into the urine, thereby reducing the blood volume.

This information is then conveyed, via afferent nerve fiber

Afferent nerve fibers are axons (nerve fibers) of sensory neurons that carry sensory information from sensory receptors to the central nervous system. Many afferent projections ''arrive'' at a particular brain region.

In the peripheral nerv ...

s, to the solitary nucleus in the medulla oblongata

The medulla oblongata or simply medulla is a long stem-like structure which makes up the lower part of the brainstem. It is anterior and partially inferior to the cerebellum. It is a cone-shaped neuronal mass responsible for autonomic (involun ...

. From here motor nerves belonging to the autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system (ANS), sometimes called the visceral nervous system and formerly the vegetative nervous system, is a division of the nervous system that operates viscera, internal organs, smooth muscle and glands. The autonomic nervo ...

are stimulated to influence the activity of chiefly the heart and the smallest diameter arteries, called arterioles

An arteriole is a small-diameter blood vessel in the microcirculation that extends and branches out from an artery and leads to capillaries.

Arterioles have muscular walls (usually only one to two layers of smooth muscle cells) and are the pr ...

. The arterioles are the main resistance vessels in the arterial tree, and small changes in diameter cause large changes in the resistance to flow through them. When the arterial blood pressure rises the arterioles are stimulated to dilate

Dilation (or dilatation) may refer to:

Physiology or medicine

* Cervical dilation, the widening of the cervix in childbirth, miscarriage etc.

* Coronary dilation, or coronary reflex

* Dilation and curettage, the opening of the cervix and surg ...

making it easier for blood to leave the arteries, thus deflating them, and bringing the blood pressure down, back to normal. At the same time, the heart is stimulated via cholinergic

Cholinergic agents are compounds which mimic the action of acetylcholine and/or butyrylcholine. In general, the word " choline" describes the various quaternary ammonium salts containing the ''N'',''N'',''N''-trimethylethanolammonium cation ...

parasympathetic nerves to beat more slowly (called bradycardia

Bradycardia, also called bradyarrhythmia, is a resting heart rate under 60 beats per minute (BPM). While bradycardia can result from various pathological processes, it is commonly a physiological response to cardiovascular conditioning or due ...

), ensuring that the inflow of blood into the arteries is reduced, thus adding to the reduction in pressure, and correcting the original error.

Low pressure in the arteries, causes the opposite reflex of constriction of the arterioles, and a speeding up of the heart rate (called tachycardia

Tachycardia, also called tachyarrhythmia, is a heart rate that exceeds the normal resting rate. In general, a resting heart rate over 100 beats per minute is accepted as tachycardia in adults. Heart rates above the resting rate may be normal ...

). If the drop in blood pressure is very rapid or excessive, the medulla oblongata stimulates the adrenal medulla

The adrenal medulla () is the inner part of the adrenal gland. It is located at the center of the gland, being surrounded by the adrenal cortex. It is the innermost part of the adrenal gland, consisting of chromaffin cells that secrete catecho ...

, via "preganglionic" sympathetic nerves, to secrete epinephrine

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands a ...

(adrenaline) into the blood. This hormone enhances the tachycardia and causes severe vasoconstriction

Vasoconstriction is the narrowing of the blood vessels resulting from contraction of the muscular wall of the vessels, in particular the large arteries and small arterioles. The process is the opposite of vasodilation, the widening of blood vesse ...

of the arterioles to all but the essential organs in the body (especially the heart, lungs, and brain). These reactions usually correct the low arterial blood pressure (hypotension

Hypotension, also known as low blood pressure, is a cardiovascular condition characterized by abnormally reduced blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood and is ...

) very effectively.

Calcium levels

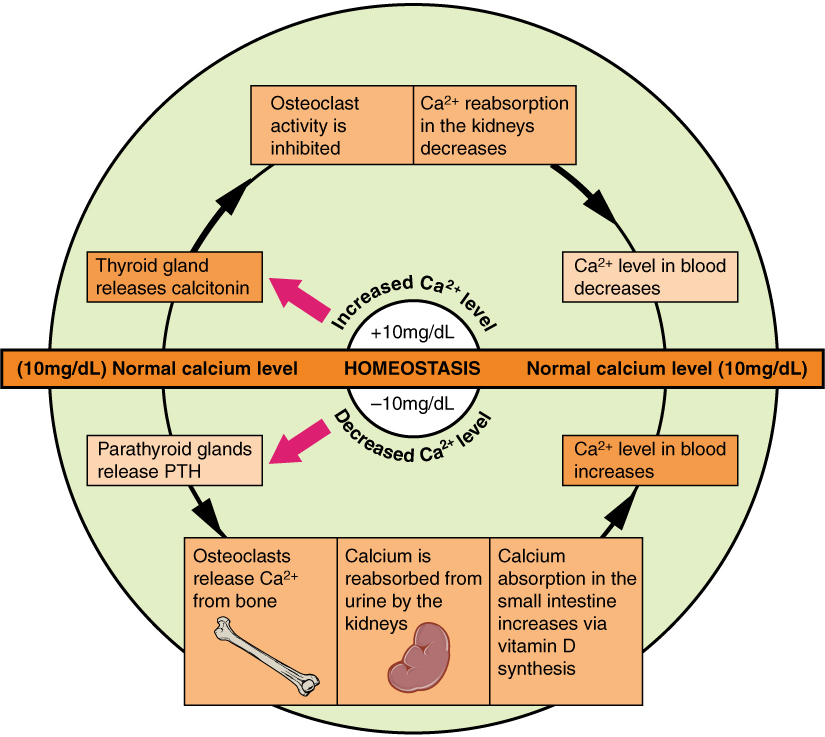

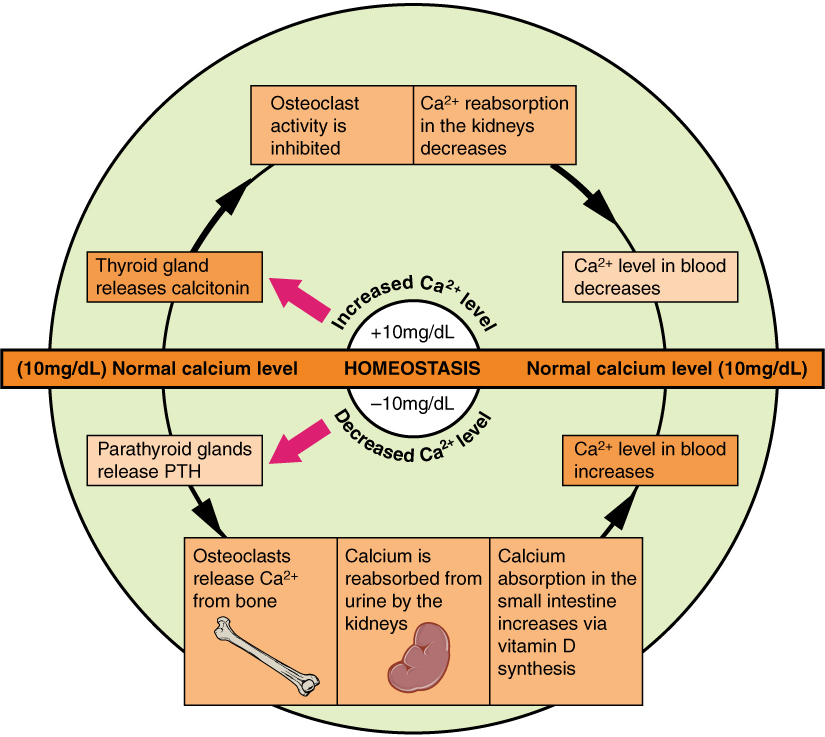

The plasma ionized calcium (Ca2+) concentration is very tightly controlled by a pair of homeostatic mechanisms. The sensor for the first one is situated in the parathyroid glands, where the chief cells sense the Ca2+ level by means of specialized calcium receptors in their membranes. The sensors for the second are the parafollicular cells in the

The plasma ionized calcium (Ca2+) concentration is very tightly controlled by a pair of homeostatic mechanisms. The sensor for the first one is situated in the parathyroid glands, where the chief cells sense the Ca2+ level by means of specialized calcium receptors in their membranes. The sensors for the second are the parafollicular cells in the thyroid gland

The thyroid, or thyroid gland, is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans, it is a butterfly-shaped gland located in the neck below the Adam's apple. It consists of two connected lobes. The lower two thirds of the lobes are connected by ...

. The parathyroid chief cells secrete parathyroid hormone (PTH) in response to a fall in the plasma ionized calcium level; the parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland secrete calcitonin

Calcitonin is a 32 amino acid peptide hormone secreted by parafollicular cells (also known as C cells) of the thyroid (or endostyle) in humans and other chordates in the ultimopharyngeal body. It acts to reduce blood calcium (Ca2+), opposing the ...

in response to a rise in the plasma ionized calcium level.

The effector organs of the first homeostatic mechanism are the bone

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, ...

s, the kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

, and, via a hormone released into the blood by the kidney in response to high PTH levels in the blood, the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In mammals, it may be the principal site for iron absorption.

The duodenum precedes the jejunum and ileum and is the shortest p ...

and jejunum

The jejunum is the second part of the small intestine in humans and most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. Its lining is specialized for the absorption by enterocytes of small nutrient molecules which have been pr ...

. Parathyroid hormone (in high concentrations in the blood) causes bone resorption

Bone resorption is resorption of bone tissue, that is, the process by which osteoclasts break down the tissue in bones and release the minerals, resulting in a transfer of calcium from bone tissue to the blood.

The osteoclasts are multi-nuclea ...

, releasing calcium into the plasma. This is a very rapid action which can correct a threatening hypocalcemia

Hypocalcemia is a medical condition characterized by low calcium levels in the blood serum. The normal range of blood calcium is typically between 2.1–2.6 mmol/L (8.8–10.7 mg/dL, 4.3–5.2 mEq/L), while levels less than 2.1 ...

within minutes. High PTH concentrations cause the excretion of phosphate ions via the urine. Since phosphates combine with calcium ions to form insoluble salts (see also bone mineral

A bone is a rigid organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red and white blood cells, store minerals, provide structure and support for the body, an ...

), a decrease in the level of phosphates in the blood, releases free calcium ions into the plasma ionized calcium pool. PTH has a second action on the kidneys. It stimulates the manufacture and release, by the kidneys, of calcitriol

Calcitriol is a hormone and the active form of vitamin D, normally made in the kidney. It is also known as 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol. It binds to and activates the vitamin D receptor in the nucleus of the cell, which then increases the exp ...

into the blood. This steroid

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused compound, fused rings (designated A, B, C, and D) arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes t ...

hormone acts on the epithelial cells of the upper small intestine, increasing their capacity to absorb calcium from the gut contents into the blood.

The second homeostatic mechanism, with its sensors in the thyroid gland, releases calcitonin into the blood when the blood ionized calcium rises. This hormone acts primarily on bone, causing the rapid removal of calcium from the blood and depositing it, in insoluble form, in the bones.

The two homeostatic mechanisms working through PTH on the one hand, and calcitonin on the other can very rapidly correct any impending error in the plasma ionized calcium level by either removing calcium from the blood and depositing it in the skeleton, or by removing calcium from it. The skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

acts as an extremely large calcium store (about 1 kg) compared with the plasma calcium store (about 180 mg). Longer term regulation occurs through calcium absorption or loss from the gut.

Another example are the most well-characterised endocannabinoids

Cannabinoids () are several structural classes of compounds found primarily in the ''Cannabis'' plant or as synthetic compounds. The most notable cannabinoid is the phytocannabinoid tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) (delta-9-THC), the primary psychoact ...

like anandamide

Anandamide (ANA), also referred to as ''N''-arachidonoylethanolamine (AEA) is a fatty acid neurotransmitter belonging to the fatty acid derivative group known as N-acylethanolamine (NAE). Anandamide takes its name from the Sanskrit word ''ananda ...

(''N''-arachidonoylethanolamide; AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), whose synthesis occurs through the action of a series of intracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s activated in response to a rise in intracellular calcium levels to introduce homeostasis and prevention of tumor

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

development through putative protective mechanisms that prevent cell growth

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a de ...

and migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

by activation of CB1 and/or CB2 and adjoining receptors.

Sodium concentration

The homeostatic mechanism which controls the plasma sodium concentration is rather more complex than most of the other homeostatic mechanisms described on this page. The sensor is situated in thejuxtaglomerular apparatus

The juxtaglomerular apparatus (also known as the juxtaglomerular complex) is a structure in the kidney that regulates the function of each nephron, the functional units of the kidney. The juxtaglomerular apparatus is named because it is next to ...

of kidneys, which senses the plasma sodium concentration in a surprisingly indirect manner. Instead of measuring it directly in the blood flowing past the juxtaglomerular cell

Juxtaglomerular cells (JG cells), also known as juxtaglomerular granular cells are cells in the kidney that synthesize, store, and secrete the enzyme renin. They are specialized smooth muscle cells mainly in the walls of the afferent arteri ...

s, these cells respond to the sodium concentration in the renal tubular fluid after it has already undergone a certain amount of modification in the proximal convoluted tubule

The proximal tubule is the segment of the nephron in kidneys which begins from the renal (tubular) pole of the Bowman's capsule to the beginning of loop of Henle. At this location, the glomerular parietal epithelial cells (PECs) lining bowman’s ...

and loop of Henle

In the kidney, the loop of Henle () (or Henle's loop, Henle loop, nephron loop or its Latin counterpart ''ansa nephroni'') is the portion of a nephron that leads from the proximal convoluted tubule to the distal convoluted tubule. Named after it ...

. These cells also respond to rate of blood flow through the juxtaglomerular apparatus, which, under normal circumstances, is directly proportional to the arterial blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) is the pressure of circulating blood against the walls of blood vessels. Most of this pressure results from the heart pumping blood through the circulatory system. When used without qualification, the term "blood pressure" r ...

, making this tissue an ancillary arterial blood pressure sensor.

In response to a lowering of the plasma sodium concentration, or to a fall in the arterial blood pressure, the juxtaglomerular cells release renin

Renin ( etymology and pronunciation), also known as an angiotensinogenase, is an aspartic protease protein and enzyme secreted by the kidneys that participates in the body's renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS)—also known as the reni ...

into the blood. Renin is an enzyme which cleaves a decapeptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Dalton (unit), Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer t ...

(a short protein chain, 10 amino acids long) from a plasma α-2-globulin called angiotensinogen

Angiotensin is a peptide hormone that causes vasoconstriction and an increase in blood pressure. It is part of the renin–angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure. Angiotensin also stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adr ...

. This decapeptide is known as angiotensin I

Angiotensin is a peptide hormone that causes vasoconstriction and an increase in blood pressure. It is part of the renin–angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure. Angiotensin also stimulates the release of aldosterone from the adren ...

. It has no known biological activity. However, when the blood circulates through the lungs a pulmonary capillary endothelial

The endothelium (: endothelia) is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels. The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the res ...

enzyme called angiotensin-converting enzyme

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (), or ACE, is a central component of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), which controls blood pressure by regulating the volume of fluids in the body. It converts the hormone angiotensin I to the active vasocon ...

(ACE) cleaves a further two amino acids from angiotensin I to form an octapeptide known as angiotensin II

Angiotensin is a peptide hormone that causes vasoconstriction and an increase in blood pressure. It is part of the renin–angiotensin system, which regulates blood pressure. Angiotensin also stimulates the release of aldosterone from the ...

. Angiotensin II is a hormone which acts on the adrenal cortex

The adrenal cortex is the outer region and also the largest part of the adrenal gland. It is divided into three separate zones: zona glomerulosa, zona fasciculata and zona reticularis. Each zone is responsible for producing specific hormones. I ...

, causing the release into the blood of the steroid hormone